Spatial and Temporal Distribution Characteristics of Heritage Buildings in Yangzhou and Influencing Factors and Tourism Development Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- To reveal the temporal and spatial distribution characteristics of 528 heritage buildings in Yangzhou;

- (2)

- To analyze the factors influencing the distribution characteristics of heritage buildings in Yangzhou across different historical periods;

- (3)

- To propose a tourism route plan for heritage buildings in Yangzhou based on preliminary analysis.

2. Data Source and Methodology

2.1. Study Area and Data Source

2.2. Methodology

3. Temporal and Spatial Distribution Characteristics of Heritage Buildings in Yangzhou

3.1. Temporal Distribution Characteristics

3.1.1. Overall Temporal Pattern

3.1.2. The Temporal Pattern of Types

3.1.3. Temporal Evolution

3.2. Spatial Distribution Characteristics

3.2.1. Overall Spatial Distribution (Nearest Neighbor)

3.2.2. Spatial Distribution Characteristics by Type

3.2.3. Kernel Density Characteristics of Spatial Distribution

4. Influencing Factors

4.1. Natural Factors

4.1.1. Water Resources

4.1.2. Terrain

4.2. Human History

4.2.1. Salt Merchant Culture and Handicraft Culture

4.2.2. Canal Transportation Culture and Hydraulic Engineering Culture

4.2.3. Literary Culture and Folk Culture

4.2.4. Religious Culture

4.2.5. Revolutionary Culture

4.2.6. War Destruction

5. Analysis on the Tourism Strategies of Heritage Buildings in Yangzhou

5.1. Regional Integration and Route Planning

5.2. Sustainable Tourism Development and Preservation

5.3. Cultural Integration and Innovative Promotion

6. Conclusions and Discussion

- (1)

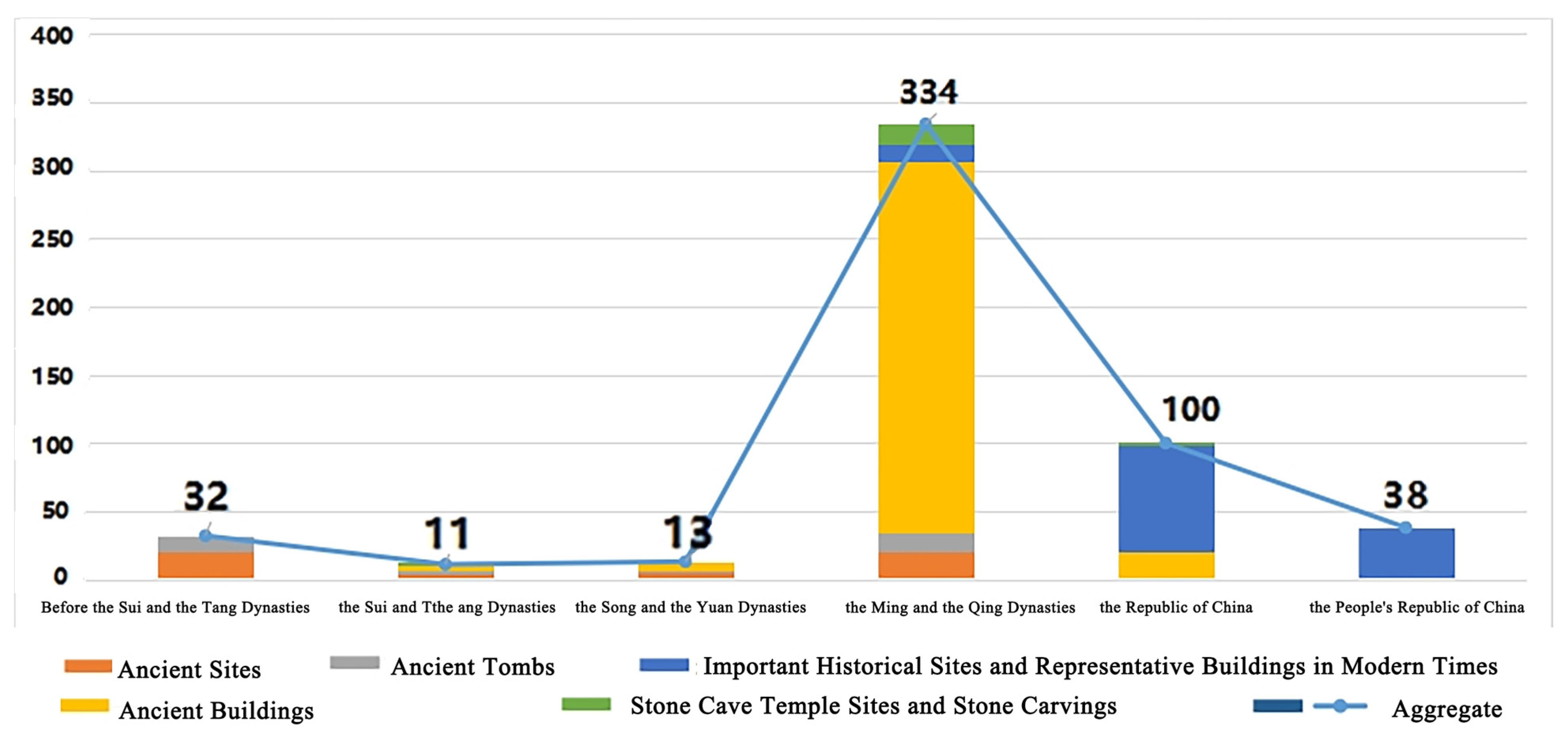

- In terms of temporal distribution, the distribution of heritage buildings in Yangzhou follows an “Λ” shape, covering six periods: the period before the Sui and Tang Dynasties, the Sui and Tang Dynasty period, the Song and Yuan Dynasty period, the Ming and Qing Dynasty period, the Republic of China period, and the modern period. The number of heritage buildings varies greatly across different periods and is closely connected to historical development. Few heritage buildings from early periods remain due to natural and human factors. The number of heritage buildings from the Ming and Qing Dynasties and Republic of China periods is huge. The number of heritage buildings in the modern period is limited because of the selection system.

- (2)

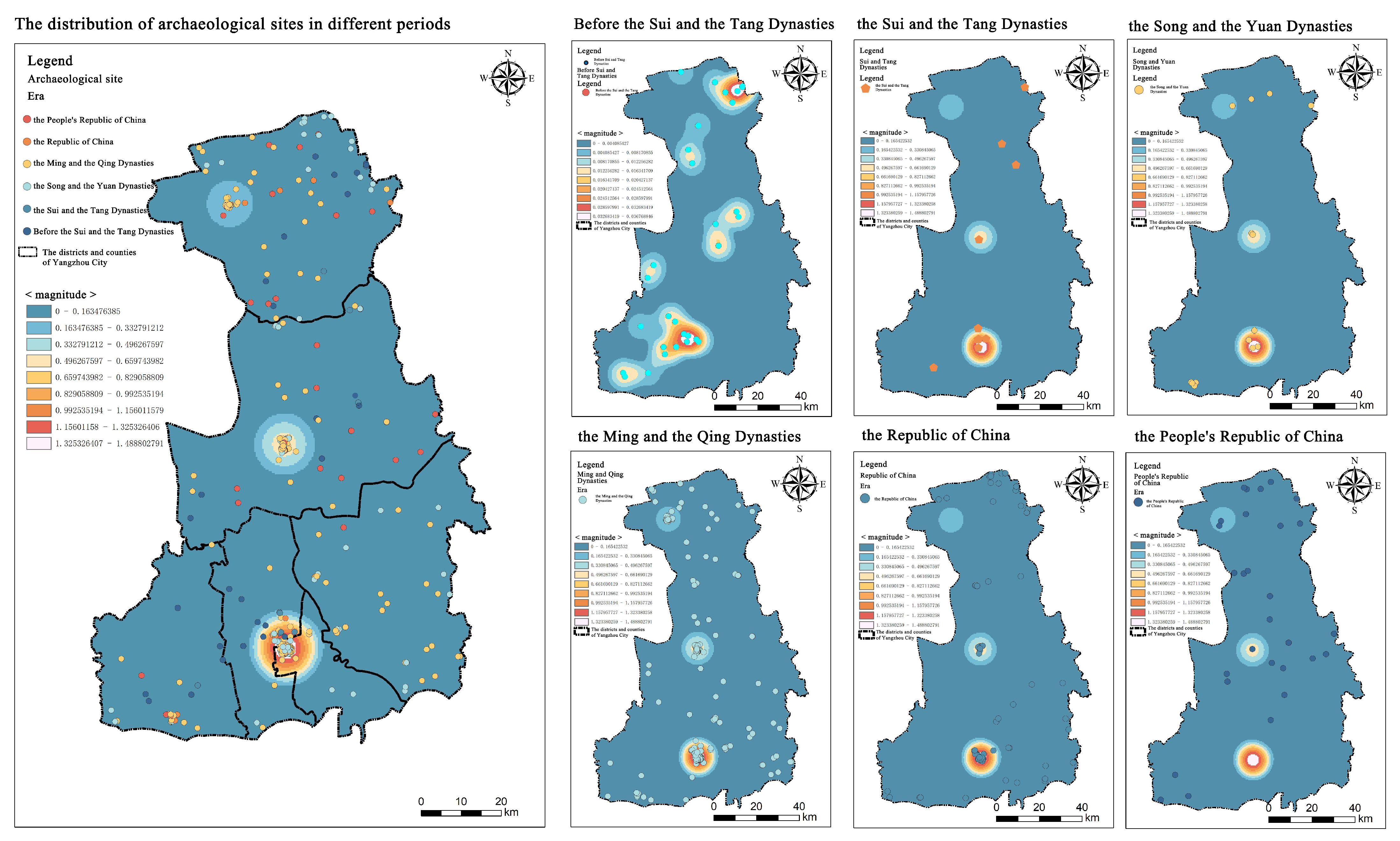

- In terms of spatial and temporal evolution, the centroid of distribution has shifted from southwest to northwest to northeast, showing an overall trend of northeastward movement. The heritage buildings in Yangzhou can be categorized into five types, including ancient sites, ancient tombs, ancient buildings, etc. Ancient sites and tombs are the dominant heritage buildings from the period before the Sui and Tang Dynasties. The types of heritage buildings from the Sui and Tang Dynasties are diversified. The number of ancient buildings from the Ming and Qing Dynasties is huge. Modern historical sites and representative buildings constitute the majority of heritage buildings from the Republic of China period, while modern buildings are the focal type in the modern period.

- (3)

- In terms of spatial distribution, the heritage buildings in Yangzhou are generally evenly distributed, with a random spatial distribution pattern. Ancient buildings are widely spread out, while ancient sites and tombs are concentrated. Kernel density analysis shows significant aggregation in Hanjiang District, Gaoyou District, and Baoying County, reflecting the historical importance of these areas as transportation hubs, administrative centers, or cultural and religious gathering places.

- (4)

- In terms of influencing factors, the formation and distribution of heritage buildings in Yangzhou are affected by both natural and human factors, with human factors having a greater overall impact. The primary factors for the construction and development of different types of heritage buildings vary. Similarly, different factors have varying impacts on the formation and development of heritage buildings. Cultural elements, such as the literary culture and salt merchant culture, have played a role in promoting the formation of heritage buildings, while war has had a negative effect on the preservation of heritage buildings. The multidimensional interaction of these factors has a more significant impact on the temporal and spatial distribution characteristics of heritage buildings in Yangzhou.

- (5)

- Based on the analysis of heritage buildings in Yangzhou, strategies such as regional integration and route planning, prioritizing sustainable tourism development and preservation, and culture fusion and innovative promotion are proposed in this study to promote the all-for-one tourism development and cultural dissemination of Yangzhou.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Harun, S.N. Heritage building conservation in Malaysia: Experience and challenges. Procedia Eng. 2011, 20, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zou, Y. Research hotspots and trends in heritage building information modeling: A review based on CiteSpace analysis. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2022, 9, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, M.; Chen, Y.F.; Zhai, Z.; Du, J. Investigating the critical issues in the conservation of heritage building: The case of China. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 51, 104319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, L. On the ‘Authenticity’ in the Protection of Cultural Heritage Buildings—Reading the Venice Charter, the Nara Document on Authenticity and the Beijing Document. J. Archit. 2011, S1, 85–87. [Google Scholar]

- Mısırlısoy, D.; Günçe, K. Adaptive reuse strategies for heritage buildings: A holistic approach. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2016, 26, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osello, A.; Lucibello, G.; Morgagni, F. HBIM and virtual tools: A new chance to preserve architectural heritage. Buildings 2018, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Liu, Z.; Wang, G. Driving Sustainable Cultural Heritage Tourism in China through Heritage Building Information Modeling. Buildings 2024, 14, 3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, N.; Degen, W. Influence mechanism and innovation of tourism development pattern of historic streets based on the perspective of tourists: A case of Pingjiang Road of Suzhou. Geogr. Res. 2015, 34, 181–196. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, L.W.C.; Davies, S.N.G.; Lorne, F.T. Trialogue on built heritage and sustainable development. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milic, R.J.; McPherson, P.; McConchie, G.; Reutlinger, T.; Singh, S. Architectural History and Sustainable Architectural Heritage Education: Digitalisation of Heritage in New Zealand. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, L.; Huang, J.; Law, A. Research frameworks, methodologies, and assessment methods concerning the adaptive reuse of architectural heritage: A review. Built Herit. 2021, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miran, F.D.; Husein, H.A. Introducing a conceptual model for assessing the present state of preservation in heritage buildings: Utilizing building adaptation as an approach. Buildings 2023, 13, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuoto, A.; Funari, M.F.; Lourenço, P.B. Shaping digital twin concept for built cultural heritage conservation: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2023, 18, 1762–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summerby-Murray, R. Analysing heritage landscapes with historical GIS: Contributions from problem-based inquiry and constructivist pedagogy. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 2001, 25, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munarim, U.; Ghisi, E. Environmental feasibility of heritage buildings rehabilitation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 58, 235–249. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdan, A.; Chambre, D.; Copolovici, D.M.; Bungau, T.; Bungau, C.C.; Copolovici, L. Heritage Building Preservation in the Process of Sustainable Urban Development: The Case of Brasov Medieval City, Romania. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, F.; Moncaster, A.; Jones, D. Rethinking retrofit of residential heritage buildings. Build. Cities 2021, 2, 495–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, H.S.S.; Khan, A.Z.; Attia, S.; Serag, Y. Classification of heritage residential building stock and defining sustainable retrofitting scenarios in Khedivial Cairo. Sustainability 2021, 13, 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrando Ortiz, A.; Viñals Blasco, M.J. Community participation in the restoration of heritage buildings. EGE Rev. Expresión Gráfica Edif. 2023, 18, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currà, E.; D’Amico, A.; Angelosanti, M. HBIM between antiquity and industrial archaeology: Former segrè papermill and sanctuary of hercules in Tivoli. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blagojević, M.R.; Tufegdžić, A. The new technology era requirements and sustainable approach to industrial heritage renewal. Energy Build. 2016, 115, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. Current problems and countermeasures for the protection of cultural relics and buildings. People’s Forum 2024, 18, 96–100. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.; Zhang, F. The precursor of the national architectural heritage protection system—The influence of the concept and practice of conservation of heritage buildings by the China Construction Society. J. Archit. 2012, S1, 92–95. [Google Scholar]

- Mollo, L.; Agliata, R.; Palmero Iglesias, L.M.; Vigliotti, M. Typological GIS for knowledge and conservation of built heritage: A case of study in Southern Italy. Inf. Constr. 2020, 72, 357. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Grussenmeyer, P.; Koehl, M.; Macher, H.; Murtiyoso, A.; Landes, T. Review of built heritage modelling: Integration of HBIM and other information techniques. J. Cult. Herit. 2020, 46, 350–360. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, H. R–C–C fusion classifier for automatic damage detection of heritage building using 3D laser scanning. J. Civ. Struct. Health Monit. 2024, 15, 927–941. [Google Scholar]

- Croce, V.; Caroti, G.; De Luca, L.; Jacquot, K.; Piemonte, A.; Véron, P. From the semantic point cloud to heritage-building information modeling: A semiautomatic approach exploiting machine learning. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Qiu, B.; Tian, Z. Research on the application method of historical building protection under the integration of multiple technologies. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2022, 43, 923–928. [Google Scholar]

- Roslan, R.; Said, S.Y. Elements in Assessing the Architectural Characteristics of Heritage Buildings. Environ.-Behav. Proc. J. 2020, 5, 313–318. [Google Scholar]

- Ornelas, C.; Sousa, F.; Guedes, J.M.; Breda-Vázquez, I. Monitoring and Assessment Heritage Tool: Quantify and classify urban heritage buildings. Cities 2023, 137, 104274. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, P.; Kweon, J.; He, J. Big data analysis and evaluation for vitality factors of public space of regenerated industrial heritage in Luoyang. Int. J. Low-Carbon Technol. 2024, 19, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q. A model approach for post evaluation of adaptive reuse of architectural heritage: A case study of Beijing central axis historical buildings. Herit. Sci. 2023, 11, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.F. A framework of sustainability refurbishment assessment for heritage buildings in Malaysia. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. IOP Publ. 2019, 268, 012011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donghui, C.; Guanfa, L.; Wensheng, Z.; Qiyuan, L.; Shuping, B.; Xiaokang, L. Virtual reality technology applied in digitalization of cultural heritage. Clust. Comput. 2019, 22, 10063–10074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, S.; Shah, L.; Adil, M.; Gohar, N.; Saman, G.E.; Jamil, S.; Qayum, F. Modeling and representation of built cultural heritage data using semantic web technologies and building information model. Comput. Math. Organ. Theory 2019, 25, 247–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.C.P.; Zhang, J.; Kwok, H.H.L.; Tong, J.C. Thermal performance improvement for residential heritage building preservation based on digital twins. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 82, 108283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, N.; Fan, H.; Zhang, Z. 3D LiDAR and multi-technology collaboration for preservation of built heritage in China: A review. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2023, 116, 103156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; van Weesep, J. Cultural values and urban planning in china: Evidence of constraints and agency in the development of the historic city of Yangzhou. J. Urban Hist. 2021, 47, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Chen, T.; Yang, N.; Qu, L.; Li, M.; Chen, D. Spatial and temporal distribution of rainfall and drought characteristics across the Pearl River basin. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 619, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yongqi, L.; Ruixia, Y.; Pu, W.; Anlin, Y.; Guolong, C. A quantitative description of the spatial–temporal distribution and evolution pattern of world cultural heritage. Herit. Sci. 2021, 9, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Sun, H.; Xu, S.; Aoki, N. Analysis of the spatial and temporal distribution and reuse of urban industrial heritage: The case of Tianjin, China. Land 2022, 11, 2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, B. Analysis of Yangzhou’s urban spatial evolution and development based on historical perspective. Chin. Foreign Archit. 2018, 5, 78–80. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, M. On the Sustainable Protection and Utilisation of Traditional Residences in Historic Cities—Analyzing the Integral Protection of Yangzhou’s Old Town. China Famous City 2014, 9, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, B. A Brief Discussion on the Historical View of Feng Shui in Yangzhou. J. Yangzhou Vocat. Univ. 2014, 18, 11–16+31. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, K.; Wu, W.; Li, T.; Dai, X. Exploring visitors’ visual perception along the spatial sequence in temple heritage spaces by quantitative GIS methods: A case study of the Daming Temple, Yangzhou City, China. Built Herit. 2023, 7, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, W.U.; Yuanhua, S. Research on the Public Perception of Yangzhou Historical and Cultural Districts Based on Network Review Text Analysis. J. Landsc. Res. 2023, 15, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P. The dream of Yangzhou in the Ming and Qing dynasties: An immigrant city built on the salt trade. China Salt Ind. 2022, 17, 57–59. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S. Impact of the Grand Canal on the Development of Yangzhou Industry and Commerce in the Ming and Qing Dynasties. J. Anqing Norm. Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2023, 42, 92–97. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J. Protection and Development of Dongguan Historical and Cultural Block in Yangzhou. J. Landsc. Res. 2020, 12, 95–97. [Google Scholar]

- Nishioka, H.; Lv, J. Urban water conservancy in Yangzhou during the Song Dynasty. Urban Dev. Res. 1996, 1, 48–50. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L.; Kang, K. Canals, Salt Merchants, Literati, Calligraphers and Painters and Yangzhou New Year Paintings—On the Elite Cultural Factors in Yangzhou New Year Paintings of the Qing Dynasty. Art Daguan 2020, 7, 114–119. [Google Scholar]

- He, J. The new tendency of the compilation of local history documents and the study of Chinese religious history. J. Renmin Univ. China 2014, 28, 140–146. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, S. Introduction to the Religious Cultural Remains of the Grand Canal. Chin. Relig. 2024, 4, 22–27. [Google Scholar]

| Phase | Ancient Sites | Ancient Tombs | Ancient Buildings | Stone Cave Temple Sites and Stone Carvings | Important Modern Historical Sites and Representative Buildings | Total (Percentage) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Sui and Tang dynasties | 20 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 32 (0.61) |

| The Sui and Tang dynasties | 4 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 11 (2.08) |

| The Song and Yuan dynasties | 5 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 13 (2.46) |

| The Ming and Qing dynasties | 21 | 13 | 273 | 15 | 12 | 334 (63.26) |

| Republican period | 0 | 2 | 19 | 1 | 78 | 100 (18.94) |

| Since modern times | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 38 | 38 (7.20) |

| Total (Percentage) | 50 (9.47) | 31 (5.87) | 302 (57.20) | 17 (3.22) | 128 (24.24) | 528 (100.00) |

| Form | Expected Average Distance/m | Average Observation Distance/m | Nearest Neighbour Ratio | p-Value | Z-Score | Spatial Distribution Categories |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ancient sites | 5798.93 | 4007.31 | 0.69 | 0.00 | −4.14 | agglomerative |

| Ancient tombs | 7175.81 | 6575.35 | 0.92 | 0.37 | −0.91 | agglomerative |

| Ancient buildings | 2339.71 | 4390.48 | 1.88 | 0.00 | 29.09 | stochastic |

| Stone Cave Temple Sites and Stone Carvings | 8654.35 | 5421.33 | 0.63 | 0.00 | −3.35 | agglomerative |

| Important Modern Historical Sites and Representative Buildings | 3675.07 | 2370.71 | 0.65 | 0.00 | −7.50 | agglomerative |

| Synthesis | 1769.92 | 2936.95 | 1.66 | 0.00 | 28.93 | stochastic |

| Form | Administrative Area | Total (Including Percentage) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baoying County | Gaoyou City | Guangling District | Hanjiang District | Jiangdu District | Yizheng City | ||

| Ancient sites | 29 | 8 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 9 | 50 (9.47%) |

| Ancient tombs | 11 | 1 | 1 | 15 | 1 | 3 | 32 (6.06%) |

| Ancient buildings | 26 | 87 | 138 | 15 | 24 | 11 | 301 (57.10%) |

| Stone Cave Temple Sites and Stone Carvings | 7 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 8 | — | 22 (4.10%) |

| Important Modern Historical Sites and Representative Buildings | 40 | 23 | 32 | 7 | 13 | 8 | 123 (23.30%) |

| Total | 113 | 122 | 172 | 44 | 46 | 31 | 528 (100%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wei, K.; Jiang, X.; Zhu, R.; Duan, X.; Yang, J. Spatial and Temporal Distribution Characteristics of Heritage Buildings in Yangzhou and Influencing Factors and Tourism Development Strategies. Buildings 2025, 15, 1081. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15071081

Wei K, Jiang X, Zhu R, Duan X, Yang J. Spatial and Temporal Distribution Characteristics of Heritage Buildings in Yangzhou and Influencing Factors and Tourism Development Strategies. Buildings. 2025; 15(7):1081. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15071081

Chicago/Turabian StyleWei, Kexin, Xuemei Jiang, Rong Zhu, Xinyu Duan, and Jiayi Yang. 2025. "Spatial and Temporal Distribution Characteristics of Heritage Buildings in Yangzhou and Influencing Factors and Tourism Development Strategies" Buildings 15, no. 7: 1081. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15071081

APA StyleWei, K., Jiang, X., Zhu, R., Duan, X., & Yang, J. (2025). Spatial and Temporal Distribution Characteristics of Heritage Buildings in Yangzhou and Influencing Factors and Tourism Development Strategies. Buildings, 15(7), 1081. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15071081