Krisarion as a Conceptual Tool for the Tectonic Inquiry of Crisis in Architectural Epistemology

Abstract

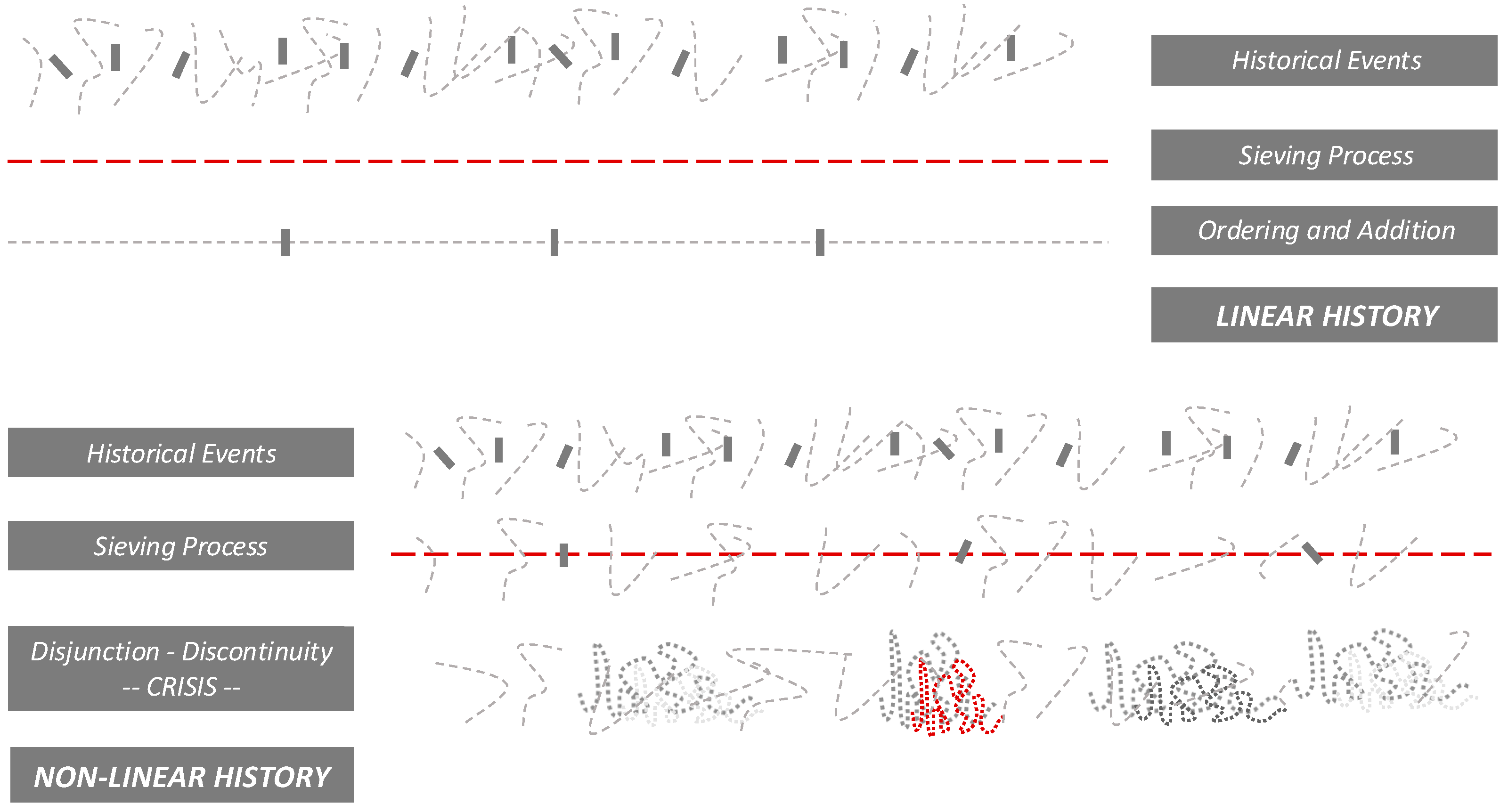

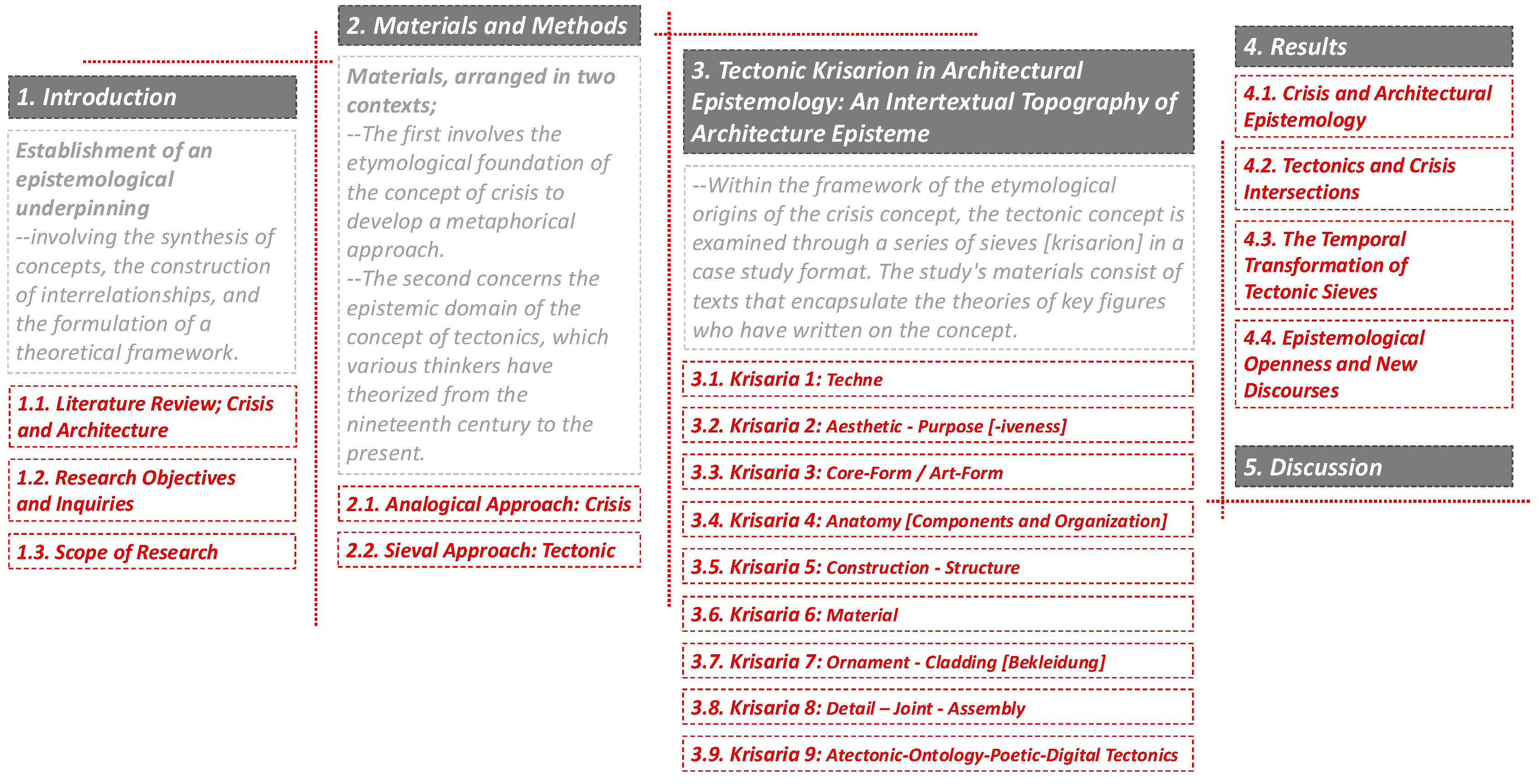

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review on Crisis

1.2. Research Objectives and Inquiries

- What does the notion of crisis signify in architecture, and why is it relevant?

- How does the absence of crisis situations affect the architectural discourse?

- Could a discussion at the crisis–tectonic intersection, embracing a critical and creative standpoint in architecture, serve as a tool to interpret the content and evolution of architectural knowledge?

1.3. Scope of Research

2. Materials and Methods

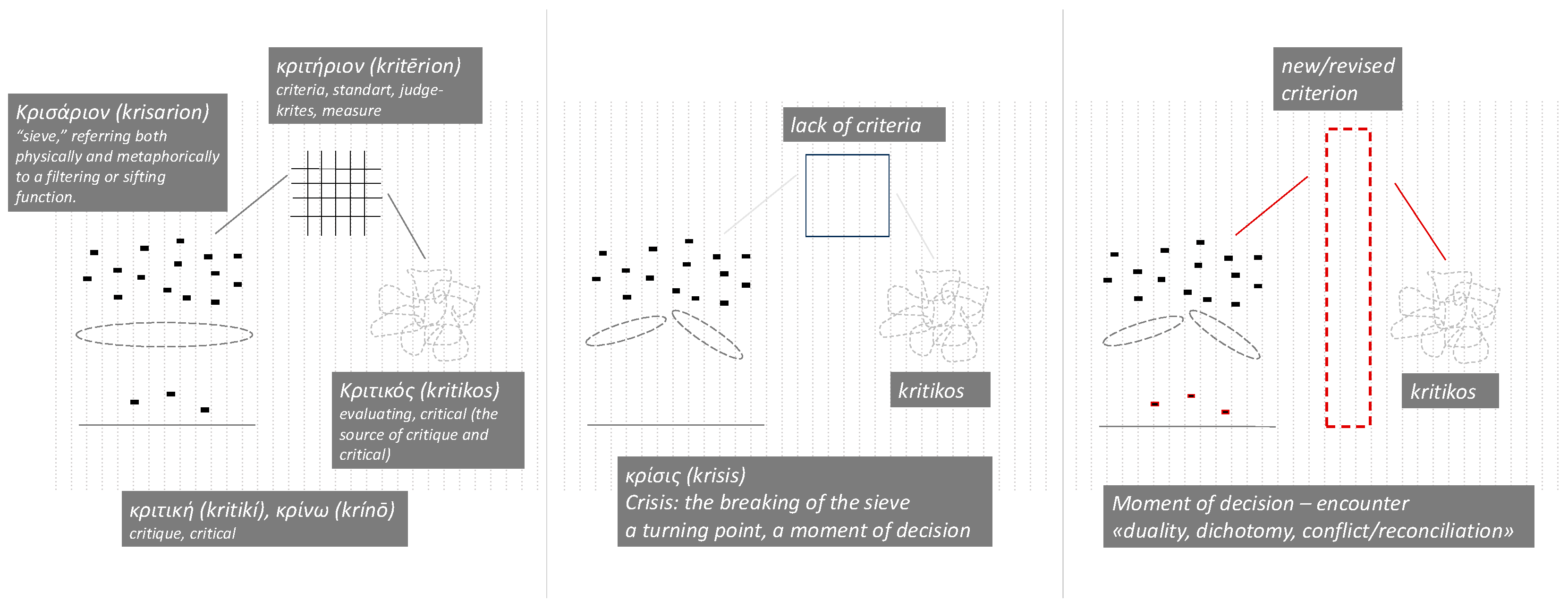

2.1. Analogical Approach: Crisis

2.2. Sieval Approach: Tectonic

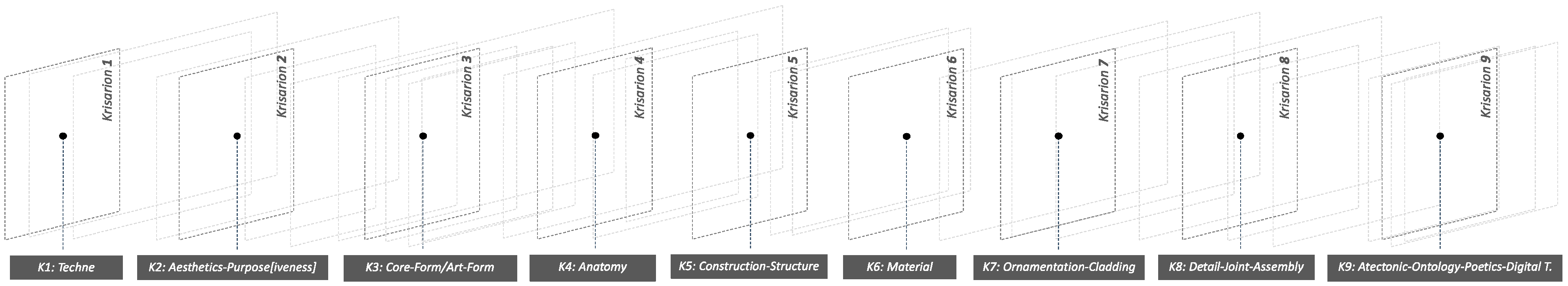

3. Tectonic Krisarion in Architectural Epistemology: An Intertextual Topography of Architecture Episteme

3.1. Krisaria 1: Techne

3.2. Krisaria 2: Aesthetic–Purpose [-iveness]

3.3. Krisaria 3: Core-Form–Art-Form

3.4. Krisaria 4: Anatomy [Components and Organization]

- Hearth—ceramics: The hearth represents the interior center of the building and its living space. For Semper, the hearth is the social and cultural core of architecture, the point where communal and familial interaction begins.

- Roof—carpentry: the roof signifies the upper covering of the building, protecting and unifying the structure.

- Mound—earthwork: the mound refers to the base or foundation, providing the building’s attachment to the ground.

- Enclosure—textile: the enclosure is the protective layer or walls, which Semper believed originated from textile-based partitions used in early ritual enclosures.

3.5. Krisaria 5: Construction–Structure

3.6. Krisaria 6: Material

3.7. Krisaria 7: Ornament–Cladding [Bekleidung]

3.8. Krisaria 8: Detail–Joint–Assembly

3.9. Krisaria 9: Atectonic–Ontology–Poetic–Digital Tectonics

4. Results

4.1. Crisis and Architectural Epistemology

4.2. Tectonics and Crisis Intersections

4.3. The Temporal Transformation of Tectonic Sieves

4.4. Epistemological Openness and New Discourses

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gilbert, A.S. The Crisis Paradigm: Description and Prescription in Social and Political Theory; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Brunkhorst, H. The return of crisis. In The Financial Crisis in Constitutional Perspective: The Dark Side of Functional Differentiation; Kjaer, P.F., Teubner, G., Febbrajo, A., Eds.; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2011; pp. 133–171. [Google Scholar]

- Roitman, J. Anti-Crisis; Duke University Press: Durham, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cordero, R. Crisis and Critique: On the Fragile Foundations of Social Life; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, E. Critique without crisis: Systems theory as a critical sociology. Thesis Elev. 2017, 143, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koselleck, R.; Richter, M.W. Crisis. J. Hist. Ideas 2006, 67, 357–400. [Google Scholar]

- Koselleck, R. Critique and Crisis: Enlightenment and the Pathogenesis of Modern Society; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Holton, R.J. The Idea of Crisis in Modern Society. Br. J. Sociol. 1987, 38, 502–520. [Google Scholar]

- Luhnmann, N. The Self-Description of Society: Crisis Fashion and Sociological Theory. Int. J. Comp. Sociol. 1984, 25, 59–72. [Google Scholar]

- Cordero, R. Crisis and Critique in Jürgen Habermas’s Social Theory. Eur. J. Soc. Theory 2014, 17, 497–515. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Z.; Bordoni, C. State of Crisis; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hay, C. Rethinking crisis: Narratives of the new right and constructions of crisis. Rethink. Marx. 1995, 8, 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, K.M. Architecture’s Desire: Reading the Late Avant-Garde; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Corbusier, L. Towards a New Architecture; Dover Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Corbusier, L. The Modulor I & II; Harward University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Giedion, S. Space, Time and Architecture: The Growth of a New Tradition, 3rd ed.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Pevsner, N. Pioneers of Modern Movement, 1st ed.; Faber & Faber: London, UK, 1936. [Google Scholar]

- Frampton, K. Modern Architecture: A Critical History, 3rd ed.; Thames and Hudson: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Vidler, A. Histories of the Immediate Present: Inventing Architectural Modernism; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Barthes, R.; Duisit, L. An introduction to the structural analysis of narrative. New Lit. Hist. 1975, 6, 237–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eco, U. The Open Work; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Venturi, R. Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, 2nd ed.; The Museum of Modern Art: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Vidler, A. The Third Typology. In Arvhitecture Theory Since 1968; Hays, K.M., Ed.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1977; pp. 284–293. [Google Scholar]

- Brott, S. Modernity’s opiate, or, the crisis of iconic architecture. Log 2012, 26, 49–59. [Google Scholar]

- Husserl, E. The Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology: An Introduction to Phenomenological Philosophy; Northwestern University Press: Evanston, IL, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, R.P. Heidegger’s account of the crisis. In Husserl, Heidegger and the Crisis of Philosophical Responsibility; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1992; pp. 157–193. [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger, M. On Time and Being; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Şan, E. Crisis as a phenomenological problem: Husserl and Heidegger. Felsefi Düsün-Acad. J. Philos. 2017, 8, 238–264. [Google Scholar]

- Megill, A. Prophets of Extremity: Nietzsche, Heidegger, Foucault, Derrida; University of California Press: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Frampton, K. Studies in Tectonic Culture: The Poetics of Construction in Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Architecture, 2nd ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Porphyrios, D. From techne to tectonics. In What is Architecture? Ballantyne, A., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2002; pp. 129–137. [Google Scholar]

- Meagher, R. Techne. Perspecta 1988, 24, 159–164. [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger, M. The Question Concerning Technology and Othe Essays; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, C. Introducing Architectural Tectonics: Exploring the Intersection of Design and Construction; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kant, I. Critique of the Power of Judgment; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Schelling, F.W.J. The Philosophy of Art; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Schopenhauer, A. The World as Will and Idea; Dover Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Hübsch, H. In What Style Should We Build?: The German Debate on Architectural Style; Getty Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Schinkel, K.F.; Mallgrave, H.F.; Contandriopoulos, C. Literary fragments (c.1805). In Architectural Theory, Volume I: An Anthology from 1871 to 2005; Mallgrave, H.F., Ed.; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bötticher, K. The principles of the Hellenic and Germanic ways of building. In In What Style Should We Build; Bloomfield, J., Forster, K.W., Reese, T.F., Eds.; Getty Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1992; pp. 147–168. [Google Scholar]

- Vallhonrat, C. Tectonics considered. Between the presence and the absence of artifice. Perspecta 1988, 24, 123–135. [Google Scholar]

- Semper, G. The Four Elements of Architecture and Other Writings (1803–1879); Mallgrave, H., Robinson, M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann, W. Gottfried Semper: In Search of Architecture; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer, M. Ontology and representation in karl bötticher’s theory of tectonics. J. Soc. Archit. Hist. 1993, 52, 267–280. [Google Scholar]

- Laugier, M.A. An Essay on Architecture; T. Osborne&Shipton: London, UK, 1755. [Google Scholar]

- Frampton, K. Bötticher, semper and the tectonic: Core form and art form. In What is Architecture? Ballantyne, A., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2002; pp. 138–152. [Google Scholar]

- Hvattum, M. Gottfried Semper and the Problem of Historicism; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sekler, E.F. Structure, construction & tectonics. In Structure in Art and Science; Kepes, G., Ed.; George Braziller: New York, NY, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Semper, G. Style in the Technical and Tectonic Arts, or, Practical Aesthetics; Getty Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Deplazes, A.; Söffker, G.H. Constructing Architecture: Materials, Processes, Structures; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Frascari, M. The tell -the- tale detail (1984). In Theorizing a New Agenda for Architecture: An Anthology of Architectural Theory 1965–1995; Nesbitt, K., Ed.; Princeton Architectural Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gregotti, V. The exercise of detailing (1983). In Theorizing a New Agenda for Architecture: An Anthology of Architectural Theory 1965–1995; Nesbitt, K., Ed.; Princeton Architectural Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Nancy, J.-L.; Lyons, P.J. Critique, Crisis. Cri. Qui Parle 2017, 26, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schinkel, W. The Image of Crisis: Walter Benjamin and the Interpretation of ‘Crisis’ in Modernity. Thesis Elev. 2015, 127, 36–51. [Google Scholar]

- De Man, P. Blindness and Insight: Essays in the Rhetoric of Contemporary Criticism; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Frampton, K.; Allen, S.; Foster, H. A conversation with Kenneth Frampton. Oct. Mag. 2003, 106, 35–58. [Google Scholar]

- Frampton, K. The Evolution of 20th Century Architecture: A Synoptic Account; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Frampton, K. Prospects for a critical regionalism. Perspecta 1983, 20, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, I.K.; Kirkegaard, P.H. A discussion of the term digital tectonics. WIT Trans. Built Environ. 2006, 90, 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Kolarevic, B. Architecture in the Digital Age: Design and Manufacturing; Kolarevic, B., Ed.; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lynn, G. Blobs, or Why Tectonics Is Square and Topology Is Groovy; Architecture New York: New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 58–61. [Google Scholar]

| Categories | Characteristics | Evaluation | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| First Approach [Crisis] | As a performative language. | It not only identifies and solves crises but also constructs narrative explanations of their causes and remedies. Political, ecological, economic… | [1] |

| Second Approach [Crisis] | As a formal or conceptual phenomenon. | Its emphasis is on uncovering the origins, meanings, and linguistic functions of crisis as a conceptual tool. In this approach, this discussion adopts a metaphorical perspective rather than a merely descriptive or analytical one. | [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. |

| Relation A [Crisis and Philosophy] | This group examines crisis in philosophy, highlighting its treatment by Heidegger, Husserl, Nietzsche, Derrida, Barthes, and Eco. | Although each thinker examines crisis from distinct perspectives—scientific rationality, value systems, language, meaning, Being…—the phenomenon is seen as an opportunity to initiate new beginnings, establish alternative frameworks, or reexamine foundational questions. | [25,26,27,28,29] |

| Relation B [Crisis and Architecture] | The grounds of the crisis’ relation to modernity, and to modern and postmodern processes. | This section explores modern architecture born of epistemic shifts and rethinks modernism amid crisis. Since the 1950s, reinterpretations of modernity’s crises have produced modernisms and postmodern approaches that critique or offer alternatives, while recent views highlight how architectural crisis intertwines with capitalist production, technological change, and ideological paradoxes. | [7,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24] |

| Categories | Characteristics | Evaluation | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Krisaria 1: Techne | Techne in ancient Greek represents the unity of art and craft. Heidegger defines it as a form of the logos of making. It covers practical skills and knowledge in various fields such as carpentry, sculpture, and architecture. | The ancient meaning of Techne is open to diverse interpretations in modern architecture. | [30,31,32,33] |

| Krisaria 2: Aesthetics–Purpose [-iveness] | This group shapes architectural expressions. Kant’s ’purposiveness without purpose’ serves as a philosophical foundation for architectural design. | Kant’s aesthetic theory provides a foundational framework for modern and postmodern architectural critiques. | [34,35,36,37,38,39] |

| Krisaria 3: Core-Form–Art-Form | Bötticher’s concepts of core-form and art-form define the structural and decorative components of architecture. | The dichotomy between core-form and art-form helps evaluate the balance between structure and aesthetics in architecture. | [34,40,41] |

| Krisaria 4: Anatomy (Components and Organization) | Semper’s four elements—hearth, roof, mound, and enclosure—serve as the basis for understanding architectural components and organization. | Organizational structures based on the building’s components can be assessed for spatial coherence and integrity. | [34,42,43,44,45,46,47] |

| Krisaria 5: Construction–Structure | Semper and Sekler distinguish between structure, construction, and tectonics, exploring their functional and aesthetic relationships in architectural design. | Construction and structural concepts integrate functionality and aesthetics in architectural design. | [42,43,44,46] |

| Krisaria 6: Material | Material selection plays a crucial role in structural systems and aesthetic expression. New technologies expand the potential for innovative designs. | The role of materials in structural systems and their contribution to aesthetic expression is crucial in evaluating architectural designs. | [41,43,44,48] |

| Krisaria 7: Ornamentation–Cladding | Semper’s Bekleidung theory emphasizes the symbolic role of cladding and its cultural references, tracing its origins to textile traditions. | The relationship between ornamentation and structure offers cultural and aesthetic interpretations in architecture. | [49,50,51,52] |

| Krisaria 8: Detail–Joint–Assembly | Tectonic concepts are linked with detail, joint, and assembly processes, highlighting structural integrity and visual expression. | Details and assembly processes have a direct impact on the durability and aesthetic value of buildings. | [30,31,32,33] |

| Krisaria 9: Atectonic–Ontology– Poetics–Digital Tectonics | Atectonic negates the tectonic, while ontological approaches investigate the existential, spatial, and temporal dimensions of architecture. Poetics highlight artistic and aesthetic values, and digital tectonics focus on parametric design and digital fabrication. | Atectonic design enables lightweight structures beyond norms, ontological approaches deepen spatial philosophy, poetics foster artistic connections, and digital tectonics offer flexible, innovative solutions. | [34,35,36,37,38,39] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kalay Yüzen, R.; Ökem, S. Krisarion as a Conceptual Tool for the Tectonic Inquiry of Crisis in Architectural Epistemology. Buildings 2025, 15, 1070. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15071070

Kalay Yüzen R, Ökem S. Krisarion as a Conceptual Tool for the Tectonic Inquiry of Crisis in Architectural Epistemology. Buildings. 2025; 15(7):1070. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15071070

Chicago/Turabian StyleKalay Yüzen, Reyya, and Selim Ökem. 2025. "Krisarion as a Conceptual Tool for the Tectonic Inquiry of Crisis in Architectural Epistemology" Buildings 15, no. 7: 1070. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15071070

APA StyleKalay Yüzen, R., & Ökem, S. (2025). Krisarion as a Conceptual Tool for the Tectonic Inquiry of Crisis in Architectural Epistemology. Buildings, 15(7), 1070. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15071070