The Philosophy of “Body and Use”: The Appropriate Use of Bodies in the Tea Space of Ming and Qing Dynasty Literati Paintings

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What are the types of tea spaces in Ming and Qing cultural paintings?

- What are the characteristics of the indoor and outdoor spaces matching the tea activities in the Ming and Qing cultural paintings?

- What is the relationship between the body of tea activities and furniture objects in the Ming and Qing cultural paintings?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Interpretation of the Connotations of Tea Space

2.2. Classification of Tea Space Types in Ming and Qing Dynasty Literati Paintings

3. Results

3.1. “Yin Jie (因借: Adaptation and Borrowing)” in Ming and Qing Dynasty Literati Paintings

3.1.1. “Using Indoor Spatial Elements for Outdoor Space Design” in Matching Tea Event Activities

3.1.2. “Using Outdoor Spatial Elements for Interior Space Design” in Matching Tea Activities

3.2. “Body Suitability” in Ming and Qing Literati Paintings

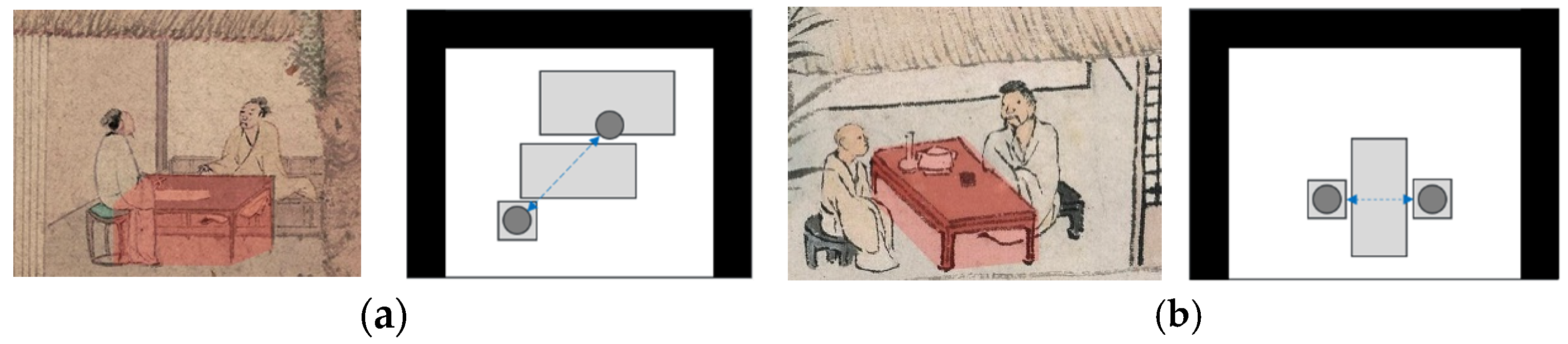

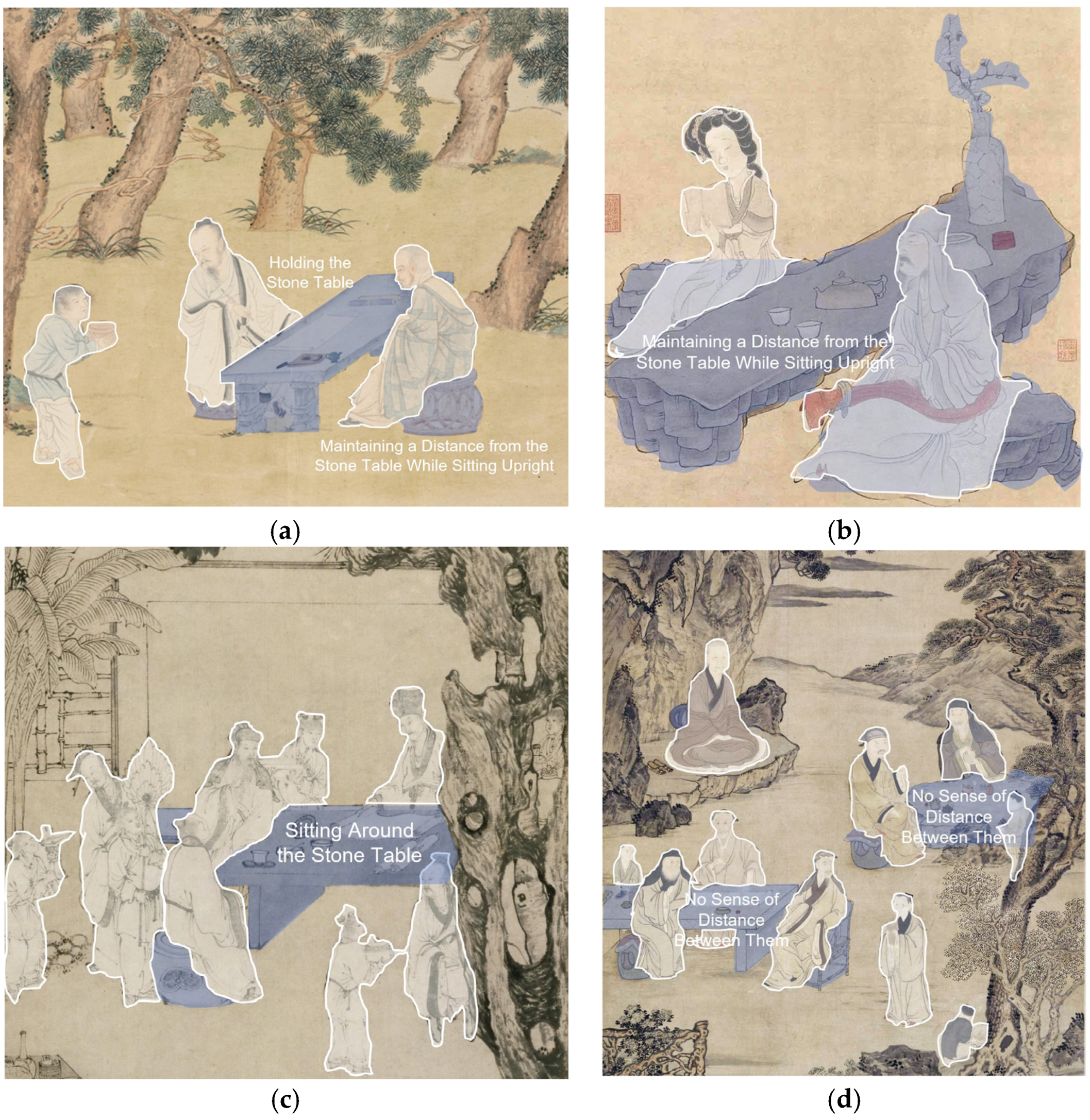

3.2.1. The Relationship Between the Physical Activity of Characters and the Use of Tabletop Furniture

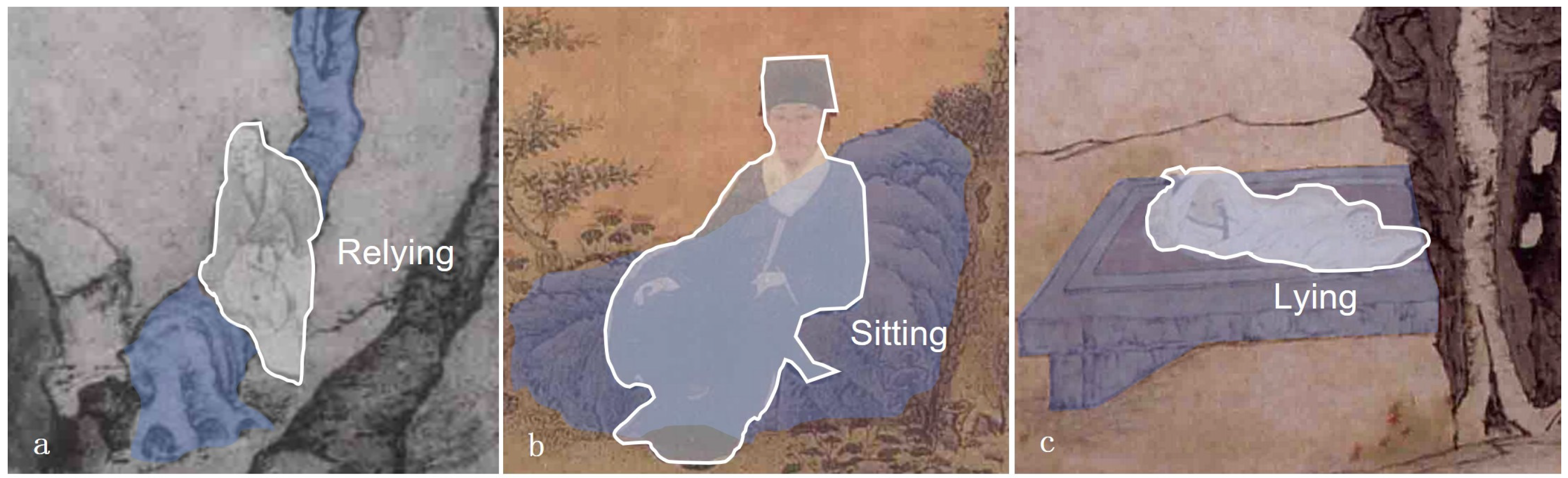

3.2.2. The Relationship Between the Physical Activity of Characters and the Use of Seating Furniture

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Book and Painting Names | Chinese | Author | Picture Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yinlinfashan | 艺林伐山 | Yang Shen (杨慎) | Page 1 |

| Teashuo | 茶说 | Tu Long (屠隆) | Page 2 |

| Yuanye | 园冶 | Ji Cheng (计成) | Page 2 |

| Dongzhuang Tu | 东庄图 | Shen Zhou (沈周) | Page 4 |

| Mo Qiuying Xiyuan Yaji Tu | 摹仇英西园雅集图 | Ding Guanpeng (丁观鹏) | Page 4 |

| Pincha Tu | 品茶图 | Wen Zhengming (文徵明) | Page 5 |

| Zhen Shang Zhai Tu | 真赏斋图 | Wen Zhengming | Page 5 |

| Yu Di Tu | 渔笛图 | Qiu Ying (仇英) | Page 5 |

| Lan Ting Tu | 兰亭图 | Qiu Ying | Page 6 |

| Guilin Qiuyue Tu | 桂林秋月图 | Yuan Jiang (袁江) | Page 6 |

| Huishan Chahui Tu | 惠山茶会图 | Wen Zhengming | Page 6 |

| Songting Shiquan Tu | 松亭试泉图 | Qiu Ying | Page 6 |

| Qingming Shanghe Tu | 清明上河图 | Qiu Ying | Page 6 |

| Tao Gu Zengci Tu | 陶穀赠词图 | Tang Yin (唐寅) | Page 6 |

| Qiushan Gaoshi Tu | 秋山高士图 | Tang Yin | Page 6 |

| Dongyuan Tu | 东园图 | Wen Zhengming | Page 6 |

| Chunquan Xiyao Tu | 春泉洗药图 | Yu Zhiding (禹之鼎) | Page 6 |

| Zhuyuan Pingu Tu | 竹院品古图 | Qiu Ying | Page 7 |

| Yuchuanzi Zhucha Tu | 玉川子煮茶图 | Ding Yunpeng (丁云鹏) | Page 8 |

| Qing Ke Xuan Chen She Qing Ce | 清可轩陈设清册 | 不详 | Page 9 |

| Zhangwu Zhi | 长物志 | Wen Zhenheng (文震亨) | Page 10 |

| Xian Qing Ou Ji | 闲情偶寄 | Li Yu (李渔) | Page 10 |

| Zhulu Shanfang Tu | 竹炉山房图 | Shen Zhe (沈贞) | Page 11 |

| Huxi Caotang Tu | 浒溪草堂图 | Wen Zhengming | Page 11 |

| Xingyuan Yaji Tu | 杏园雅集图 | Xie Huan (谢环) | Page 11 |

| Yudong Xianyuan Tu | 玉洞仙源图 | Qiu Ying | Page 12 |

| Donglin Tu | 东林图 | Qiu Ying | Page 12 |

| Jiaoyin Jiexia Tu | 蕉阴结夏图 | Qiu Ying | Page 12 |

| Qinshi Tu | 琴士图 | Tang Yin | Page 12 |

| Xiejing Huancha Tu | 写经换茶图 | Qiu Ying | Page 12 |

| Xianhua Gongshi Tu | 闲话宫事图 | Chen Hongshou (陈洪绶) | Page 12 |

| Pingu Tu | 品古图 | You Qiu (尤求) | Page 12 |

| Shuihuiyuan Yaji Tu | 水绘园雅集图 | Dai Cang (戴苍) | Page 12 |

| Jiuri Xing’an Wenyan Tu | 九日行庵文宴图 | Fang Shishu (方士庶) | Page 13 |

| Qiaolin Zhuming Tu | 乔林煮茗图 | Wen Zhengming | Page 13 |

| Hengshan Xiansheng Tingsong Tu | 衡山先生听松图 | Xu Zhizhen (许至震) | Page 13 |

| Yuanzhong Minghua | 园中茗话 | You Qiu | Page 13 |

| Chaju Shiyong Tu | 茶具十咏图 | Wen Zhengming | Page 13 |

| Tongyin Gaoshi Tu | 桐荫高士图 | Lu Zhi (陆治) | Page 14 |

Appendix B

| Book and Painting Names | Chinese | Interpretation | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yinjie Tiyi | 因借体宜 | the suitability of borrowing | Emphasizing the basis of respecting nature, cleverly using natural and artificial elements to create a garden space with unique artistic conception and beauty. |

| Yin Jie | 因借 | adaptation and borrowing | The introduction of landscape, architecture, skyline and other landscapes outside the garden into the garden, so that the scenery outside the garden echoes and integrates that indoors and expands the vision and level of the landscape. |

| Ti Yi | 体宜 | body suitability | Suitability and rationality, including suitability with the natural environment, suitability with the user’s needs and more emphasis on “human feelings”. |

| Dou Cha | 斗茶 | tea competition | A kind of tea culture activity popular among the literati in ancient China, which was interesting and competitive. |

References

- Mao, H.S.; Yin, Z.P.; Li, S.Q.; Gu, G. Study on Tea Houses and Their Space Organization in the Gardens of the Middle and Late Ming Dynasty from the Perspective of Tea Art Changes. Landsc. Archit. Front. 2020, 3, 30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.P.; Liu, Y.Y. Sunrays Passing the Clouds and Dropping on the Teacup: Influences of Scholars’ Tea Fondness on Gardens in Late Ming Period. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2012, 28, 101–104. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Y. Yilin Fashan; Commercial Press: Shanghai, China, 1936. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Z.H.; Tu, L. Zhangwu Zhi: Remaining Matters of Examination; Zhejiang People’s Fine Arts Publishing House: Hangzhou, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L. Research on Tea Space in Ming and Qing Dynasty Paintings from the Perspective of Landscape Narrative. Cult. Relic Apprais. Apprec. 2021, 20, 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, C.; Liu, Y.C. Yuan Ye; Jiangsu Literature and Art Publishing House: Nanjing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, C.; Al Qassimi, N.; Awad, J. The Analysis of the Japanese “Borrowed Landscape” Concept in Tadao Ando’s Architecture. Int. J. Adv. Res. Eng. Innov. 2021, 3, 48–62. [Google Scholar]

- So, H.S. A Study on the Structure of Soshaewon Landscape Garden Featuring Borrowed Scenery-Focusing on the Soshaewon Sisun and the Thirty Poems of Soshaewon. J. Korean Inst. Tradit. Landsc. Archit. 2011, 29, 59–69. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.M.; Cheon, D.Y. The Nature-Introducing Techniques in Landscape and Traditional Architecture through Borrowed Landscape. Korean Inst. Inter. Des. J. 2007, 16, 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, H.S.; Yin, Z.P. Landscape Projection of Yaji Culture: Literature, Activities, and Space. J. Archit. 2023, 2, 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, J.P. Chinese Tea Painting; Zhejiang Photography Publishing House: Hangzhou, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H. The Art History of “Space”; Qian, W.Y., Translator; Shanghai People’s Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Q.Y.; Wang, Y.T. The Spatial Language of the Illustrations in the Novels of Ming Dynasty. J. Archit. 2016, 4, 112–117. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Liu, S.S. Image and Garden: An Interdisciplinary Research on Garden Paintings. Zhuangshi 2021, 2, 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfgang, F. Japanese Teahouse and Spatial Aesthetics; Guangxi Normal University Press: Guilin, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, J. Korean Gardens: Tradition, Symbolism and Resilience; Hollym: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C.; Du, X.X. Cultural Connotation of Literati Tea in the Tang and Song Dynasties and Its Forming Process. Front. Hist. China 2024, 19, 287–311. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, F.L.; Zhang, J.Q.; Yin, S.K. Behavior Rules Space: To Analysis the Complex Phenomena of the Space in Garden from the Tea-tasting Behavior in Literati Garden. Archit. Cult. 2014, 8, 143–144. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H. Heavy Screen: Media and Expression of Chinese Painting; Wen, D., Translator; Shanghai People’s Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. Moshan Fanshui; Donghua University Press: Shanghai, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- School of Architecture, Tsinghua University (Ed.) Beijing Summer Palace: The Remarkable Legacy of Chinese Royal Garden Architecture; Taipei Architectural Association Press: Taipei, Taiwan, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, X. The Enchanting Surface: Fun Things from the Ming and Qing Dynasties; Liu, Z.H.; Fang, H., Translators; Central Compilation and Translation Press: Beijing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Y.J.; Wang, X.K.; He, M.F. The Continuation and Development of the Traditional Aesthetic of “Beauty of Void and Tranquility” in Modern Tea Space Design. Furnit. Inter. Des. 2024, 31, 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Z.H. Zhangwu Zhi; Li, X., Wang, G., Eds.; Jiangsu Literature and Art Publishing House: Nanjing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. Complete Works of Li Yu, Volume 3, Occasional Idle Thoughts; Compilation by Shan, J.H.; Zhejiang Ancient Books Publishing House: Hangzhou, China, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X. Ten Chronicles of Qing Dynasty: The World of Meaning of Literary Objects; Peking University Press: Beijing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, G.; Chen, J.; Lin, Z. Cultural Sustainable Development Strategies of Chinese Traditional Furniture: Taking Ming-Style Furniture for Example. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.D. Tea Related Images: Tea Life and Tea Furniture in Ancient Paintings; China Forestry Press: Beijing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

| Main Types of Tea Spaces | Author and Work Title | Content Summary | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Factors | Behavioral Activities | ||

| Hall Style (厅堂式) | Pincha Tu (品茶图) | lush trees, flowing water, tea table, hall | sipping tea and chatting (two elegant scholars), boiling water and preparing tea (tea assistant) |

| Zhen Shang Zhai Tu (真赏斋图) | hall, with books and paintings placed on the bookshelf | chatting (two elegant scholars), boiling water and preparing tea (tea assistant) | |

| Water Pavilion Style (水榭式) | Yu Di Tu (渔笛图) | pavilion, mountain, bed, several books on the table | sitting on a water pavilion (one elegant scholar), boiling water and preparing tea (tea assistant) |

| Lan Ting Tu (兰亭图) | mountain streams, curved water | sitting by the railing (one elegant scholar), boiling tea, delivering tea (tea assistant) | |

| High Pavilion Style (高阁式) | Guilin Qiuyue Tu (桂林秋月图) | woman, pavilion | drinking tea and admiring the full moon |

| Grass Pavilion and Terraces Style (亭台式) | Huishan Chahui Tu (惠山茶会图) | pine forests, thatched cottages, springs, wells | sitting around the well, taking a walk in the woods, enjoying the scenery while chatting (several elegant scholars), boiling water and preparing tea (tea assistant) |

| Songting Shiquan Tu (松亭试泉图) | grass pavilion, the Songxi River, tree in front of the pavilion, a set of tea stoves and pots, tea jars, tea cups, etc. | leaning against the railing and leaning near the stream (one elegant scholar), fetching water and preparing tea (tea assistant) | |

| Qingming Shanghe Tu (清明上河图) | a high platform, tea set | gathering on a high platform (several elegant scholars), preparing tea in a corner of the platform (tea assistant) | |

| Combination Style (组合式) | Tao Gu Zengci Tu (陶穀赠词图) | Tao Gu and the woman, screens, rockeries, plantain leaves | listening to the Guqin (Tao Gu), preparing tea (tea assistant) |

| Qiushan Gaoshi Tu (秋山高士图) | the autumn river, the mountain | watching the waterfall or playing chess (several elegant scholars), preparing tea and delivering it to a pavilion (tea assistant) | |

| Dongyuan Tu (东园图) | hall, water pavilion, bridge, flowing water | gathering in Dongyuan (several elegant scholars), preparing tea (tea assistant) | |

| Chunquan Xiyao Tu (春泉洗药图卷) | spring flowers, magnolias, peach blossoms, pear blossoms, and bamboo groves | resting in plant space (one elegant scholar), behind a small hill and heading to serve tea (tea assistant) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, L.; Shi, Y. The Philosophy of “Body and Use”: The Appropriate Use of Bodies in the Tea Space of Ming and Qing Dynasty Literati Paintings. Buildings 2025, 15, 968. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15060968

Zhang L, Shi Y. The Philosophy of “Body and Use”: The Appropriate Use of Bodies in the Tea Space of Ming and Qing Dynasty Literati Paintings. Buildings. 2025; 15(6):968. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15060968

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Lin, and Yang Shi. 2025. "The Philosophy of “Body and Use”: The Appropriate Use of Bodies in the Tea Space of Ming and Qing Dynasty Literati Paintings" Buildings 15, no. 6: 968. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15060968

APA StyleZhang, L., & Shi, Y. (2025). The Philosophy of “Body and Use”: The Appropriate Use of Bodies in the Tea Space of Ming and Qing Dynasty Literati Paintings. Buildings, 15(6), 968. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15060968