1. Introduction

Spatial order [

1,

2], sustainable development [

3] (p.24), and landscape values [

4] constitute an open set of typical, highly appreciated values. They set directions for design, planning, and spatial management. Scientifically justified, defined by law [

5], and legally regulated, these aspects are in fact verified or protected only in regard to specific projects and realizations. Hence, there is a need to clarify the concept of sustainable architecture. Scientists have pointed out that there are many different interpretations of the concept of sustainable architecture [

6] (p.19), [

7] (p.28). There are formulas that correspond to the original perception of sustainable development, based on respect for the natural environment. This idea corresponds to the applicable regulations in Poland, such as those focused on the detailed scope and form of a construction project [

8], which assumes that the spatial, functional, and technical solutions adopted in an architectural and construction project should reduce or eliminate the impact of the building on the environment, nature, human health, and other construction facilities, in accordance with separate regulations. At the same time, the regulations list the scope of mandatory information to be provided with respect to the architectural project, in order to confirm the limitations regarding the impact of the building on the environment (§ 20,

Section 1, point 9) [

8]. In terms of the construction work, these parameters include the impacts of the construction work on the existing vegetation as well as elements of the ground surface, including the soil, surface water, and groundwater.

Over the years, the concept of sustainable development has been expanded to include other important factors of development, such as social progress and economic growth. The report from the World Commission on Environment and Development, ‘Our Common Future’, states ‘The environment does not exist as a sphere separate from human actions, ambitions, and needs’ [

3] (p.13). Sustainable development is currently being adopted in various projects, including architectural ones involving the expansion of sports and tourist infrastructure, in order to improve the physical health of individuals and the overall health condition of society [

9].

These projects combine environmental, social, and economic dimensions. Therefore, sustainable architecture—or environmentally friendly architecture—is often understood as architecture with minimal impact on the environment while meeting the needs of users. Sustainable architecture plays a special role in regions of high natural, landscape, and cultural value. In such areas, architecture is also subjected to the highest evaluation criteria. Peculiar conditions often initiate the development of villages, even becoming an incentive to create new, modern settlements. Construction investments are the first signal of economic recovery and may also contribute to the expected social progress and social well-being advancements. Paradoxically, however, it sometimes happens that the advantages of the environment lead to its destruction [

10,

11]. Changing the landscape through the introduction of buildings leaves a mark. Initially, in such circumstances, it becomes an exemplary complement to the natural world, until it exceeds certain, difficult-to-specify boundaries. Mountain areas are among the regions distinguished by the beauty of nature, the landscape, and cultural values, including the Karkonosze Mountains, as a unique geomorphic structure in Central Europe. The highest mountain, massif, in the Sudeten Mountains, is visited by tourists all year round, and such tourist traffic has instigated construction activity. The area is exposed to uneven, immoderate, and unsustainable urbanization. The extreme development of the tourism industry impacted the Karkonosze Mountains in the 1920s and 1930s, then in the second half of the 20th century, and again in the first half of the 21st century. In the first period of mass tourism—and even during the second one—architectural layouts were created that were characterized by moderate interference with the natural environment while increasing the quality of local capital. These structures were sports investments, built during the post-war crisis (i.e., after World War I and World War II). The microclimate of the Karkonosze Mountains was perfect for winter sports enthusiasts (which, at that time, was in the blooming phase). Sports facilities in the Karkonosze Mountains are an example that can serve as an inspiration to solve real problems through sustainable architecture principles.

The desire to set design standards is part of the eternal search for architectural and planning solutions that are optimal for areas which are particularly sensitive, such as mountains. Research and discussions on the problem have been conducted by architects, urban planners, and representatives of other sciences in various thematic areas resulting from the scope of their interest. The subject of the architecture and spatial development of the Sudetes (including the Karkonosze Mountains) has been considered from various perspectives, particularly in terms of analyses of the set of features shaping regional buildings [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. A large number of publications have been devoted to the tourist potential of the Sudeten region [

22]. Among others, the geographer Jacek Potocki [

23] explored the issues of tourism and tourism management in the Sudetes, as well as sports dependent on mountain conditions, in the context of their development and regimes for the protection of nature. The general message of the abovementioned studies is dominated by concern for preserving the character and beauty of the Sudetes landscape.

We can learn more about the impact of tourism and winter sports on the mountain landscape from the literature originating from Alpine countries, which have long been attempting to overcome the problem of large-scale urbanization of mountain areas. The Alpine countries have produced studies on their architectural and urban heritage, created on the basis of general enchantment with sports and mountains. The issue of developing the Alps has therefore become the subject of several cross-sectional studies. The publication ‘Switzerland—an Urban Portrait’ [

24] provides an analysis and scenarios for the development of the main cities of Switzerland and the Alpine region on the basis of several years of research conducted by ETH Studio Basel. The authors describe Swiss resorts, noticing their seasonality, the collision of the global and local worlds, urban features, and the transformation of old towns into modern resorts following the change in the nature of tourism, among other aspects. A critical analysis of ski resorts in the French Alps can be found in the publication ‘Stations de Sports d`hiver: urbanisme & architecture, Rhône—Alpes’ [

25] prepared by the Règion Rhône-Alpes, service de l’Inventaire général du patrimoine culturel. Ski resorts are presented against the background of the historical context, as well as urban, architectural, cultural, economic, and social issues. This type of study consisted in particular of observations regarding the architectural and urban planning principles that influenced the creation of innovative projects.

Interesting reflections on the swimming pool facilities in the modernist period in Switzerland have been presented by Johannes Stoffler [

26]. He highlighted the aspect of landscape contemplation which, in addition to hygiene, sports, and relaxation, was offered by modernist swimming pool facilities of that time.

Among the literature in the field of spatial planning and landscape shaping, the multi-volume work by Władysław Czarnecki—in which one can find an evaluation of almost all contemporary urban and architectural problems [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]—as well as the publication ‘O czynniku kompozycji w planowaniu przestrzennym’ by Aleksander Böm [

33], deserve special mention. The author of the latter book draws attention to the powerlessness of planning and construction rules, or technology (meticulously recording, e.g., the features of the environment), which attempt to create the aesthetic values of urban composition. He claims that beauty is born between the work of the creator and the eye of the observer—in an atmosphere of emotion, not mathematics—and this process is still unrecognized.

The landscape of mountains subjected to the pressure of tourism and the absurdities of modern times have been clearly depicted by the photographer Lois Hechenblaikner in ‘Winter Wonderland’ [

34].

Indirectly, studies devoted to sports and tourist construction touch on the aspect of spatial order. The subject of designing outdoor sports and recreation equipment has been presented in the form of a script by Barbara Rzegocińska-Tyżuk [

35]. The development of rules for the development and recreational use of areas of outstanding natural and landscape value was undertaken by Halina Łapińska [

36]. Other publications have explored the subject of sports construction through the presentation of projects, including those in the Alpine regions [

37,

38].

The issues of designing sports and tourist facilities in the inter- and post-war period in the highest Polish mountain range—the Carpathian Mountains—became the center of attention for Borys Lange, Stanisław Marzyński, and others [

39,

40]. In contrast to numerous catalogs, which are as important for an architect as the written word, some current books present a full picture of the development of sports architecture against the background of the development of many civilizations, such as those by Anna Pawlikowska—Piechotka and Maciej Piechotka [

41,

42]. The motto of the first study is the recommendations of the architect Edgar Norwerth regarding sports facilities: accessibility, appropriate numbers, functionality, and beauty.

To date, the literature has lacked a broader study that addresses the issues of sports, architecture, landscape, and Polish mountain areas. While the topic has been more extensively developed recently [

43], this gap is also filled by the research presented in this article. The advantage of this research is not only the bringing to light of historical data but also their arrangement and illustration using sketches, photographs, and maps, as well as the observation of regularities in the sphere of architecture and landscape, which affect the perception of mountain spaces. The research conducted by historians has typically descriptively indicated places associated with practicing sports, rarely supplementing them with specific iconographic representations. Przemysław Wiater wrote about the beginnings of winter sports—especially skiing—in the Karkonosze and Jizera Mountains; however, as mentioned above, modest data on selected places of sports were presented [

44]. Therefore, in this research, the following is true:

- -

Sports centers in the region of the Karkonosze Mountains were compiled and described (i.e., locations with sport, recreational, and tourist offerings), in accordance with the adopted logical structure;

- -

A register of sports and recreational facilities which are historically important and contribute to the significance of the region was prepared;

- -

The factors that contribute to the quality of the Karkonosze Mountains sports facilities were selected;

- -

The development of sports infrastructure in the Karkonosze Mountains was shown in a broad context: against the background of world trends, as well as historical and economic events;

- -

Archival materials were found, collected, and made available, facilitating quick access to sources for scientists interested in the subject;

- -

Sketches, diagrams, drawings, and photographs were made, which serve to record the location, development, and appearance of buildings, the lack of which to date has made it difficult to orient oneself with respect to the subject of the research.

In addition, this research presents important data and issues, not only for the region, whose assets include unspoiled nature, outstanding architecture, and conditions for practicing sports, but also for the country as a whole. The author of this research took on a challenge on the scale of collective foreign studies, despite the fragmentary preservation of archival materials concerning the studied area.

The sports facilities (sports layouts) that are the subject of research were created, as mentioned above, in the 20th century. They arose as a result of the popularization of physical education, the hygiene movement, and the bath culture that swept Europe in modern times at the end of the 18th century. In the part of Europe where the Karkonosze Mountains and the associated sports facilities are located, green areas were initially the background for sports activities. The natural predispositions of the area were used for sports purposes (e.g., river and seaside bathing areas and ice rinks on water bodies). At the beginning of the 20th century, the concept of the park (promoted as a “People’s park”) came even closer to the needs of athletes (e.g., simplification of the path system, zoning for sports equipment, and the creation of multi-functional clearings). Since the 1920s, sports parks have been created for active leisure and professional sports practice. Simultaneously with the creation of parks, the first independent sports facilities were built. In subsequent years, the sports layouts—in more or less formalized form—were always accompanied by greenery. In the second half of the 20th century, sports grounds were perceived as an antidote to unhygienic working conditions and poor housing conditions. Attention was drawn to the obvious role of the landscape, greenery, and composition in the design and planning of sports areas [

29]. It was specified that the following sports, recreation, and park facilities should be included: recreation and walking parks, forest parks, people’s parks, boulevards and promenades, children’s gardens, sports equipment complexes, and sports centers, among others. Providing a brief explanation of the history and theory of sports systems is important due to the different contemporary tendencies in the design of sports areas: at present, organizing sports equipment on minimal surfaces and cramming them into closed volumes for multiple purposes is gaining popularity.

2. Materials and Methods

Empirical studies were conducted; in particular, they were observational (descriptive and analytical) studies of sports facilities in the Karkonosze Mountains region. The following methods were adopted: observation of spatial structure (registration and determination of relationships, field studies, and analyses), individual case studies (examination of specific examples), diagnostic surveys (including interviews and scientific and artistic events) regarding the history of the construction of sports facilities (ideally with witnesses participating in the erection of sports facilities), the examination of documents (including archival studies and construction documentation), and analysis and criticism of the literature.

The research method consisted of the following:

- -

Analysis of the origins of the sports movement and sports facilities in the Karkonosze Mountains against the background of cultural, social, and political changes;

- -

Problem analysis of key issues related to sports functions in the Karkonosze Mountains (e.g., the possibility of developing winter sports, trends in the architecture of sports facilities, and romantic fascination with the natural landscape in sports layouts);

- -

Observation, description, analysis, and systematization of sports centers and sports layouts;

- -

Selection of sports layouts, with available archival material allowing for detailed analysis and presentation of data;

- -

Summary of research results showing the lasting benefits derived from developing the sports functions introduced to the space of the Karkonosze region;

- -

Subjecting the research results to the criticism of contemporary views regarding, among others, the advisability of sports investments and environmental threats.

Confronting the research results with a different point of view allowed for the selection of principles that make the sports principles in the Karkonosze Mountains recognizable, particularly relating to positive impacts on the surroundings. Due to the preservation of the character and beauty of the landscape and nature, these sports facilities can be classified as sustainable—in other words, introducing order.

The most popular mountain sports centers in the Karkonosze Mountains and the associated foothill zone (within Karkonosze County, Lower Silesian Voivodeship) were observed. The review concerned Jelenia Góra, the capital of the region, located in the foothill zone of the Karkonosze Mountains; health resorts open to patients, tourists, and sports practitioners (Cieplice in the foothill zone of the Karkonosze Mountains, now part of Jelenia Góra); bases for trips to the mountains (Sobieszów, Piechowice, Podgórzyn, and Kowary); mountain sports stations (Przesieka, Michałowice, Zachełmie, Miłków, Górzyniec, Borowice Jakuszyce, and Jagniątków); resorts; climatic stations; tourist centers with comprehensive and specialized sports and tourist infrastructure and tourist attractions (Karpacz, Szklarska Poręba, and Przesieka); and high mountain bases and shelters including a complex of tourist and sports buildings (e.g., in the area of the Kamieńczyk Waterfall, the shelter on Hala Szrenicka, the Szrenica shelter, the shelter under the Łabski Peak, and so on).

The historical division into settlement units, functioning until the end of the 1970s, was taken into account. At present, these centers have been absorbed into the new settlement structure.

A review of all sports facilities built in the Karkonosze Mountains region in the 1920s was carried out, particularly swimming pools, ski jumps, ice rinks, sports fields, and ski and luge trails. Most of the data on sports facilities came from photographs, archival maps, and historical accounts. Inquiries and field inspections were conducted. Based on the collected materials, the location and approximate appearance of sports facilities are presented in graphic form. During data recording, initial observations were made regarding the features of sports facilities. However, a detailed analysis was carried out on selected examples. Objects were considered, the archival material of which allowed for the determination of the least unambiguous dimensions as, in most cases, these objects no longer exist and often only artifacts remained.

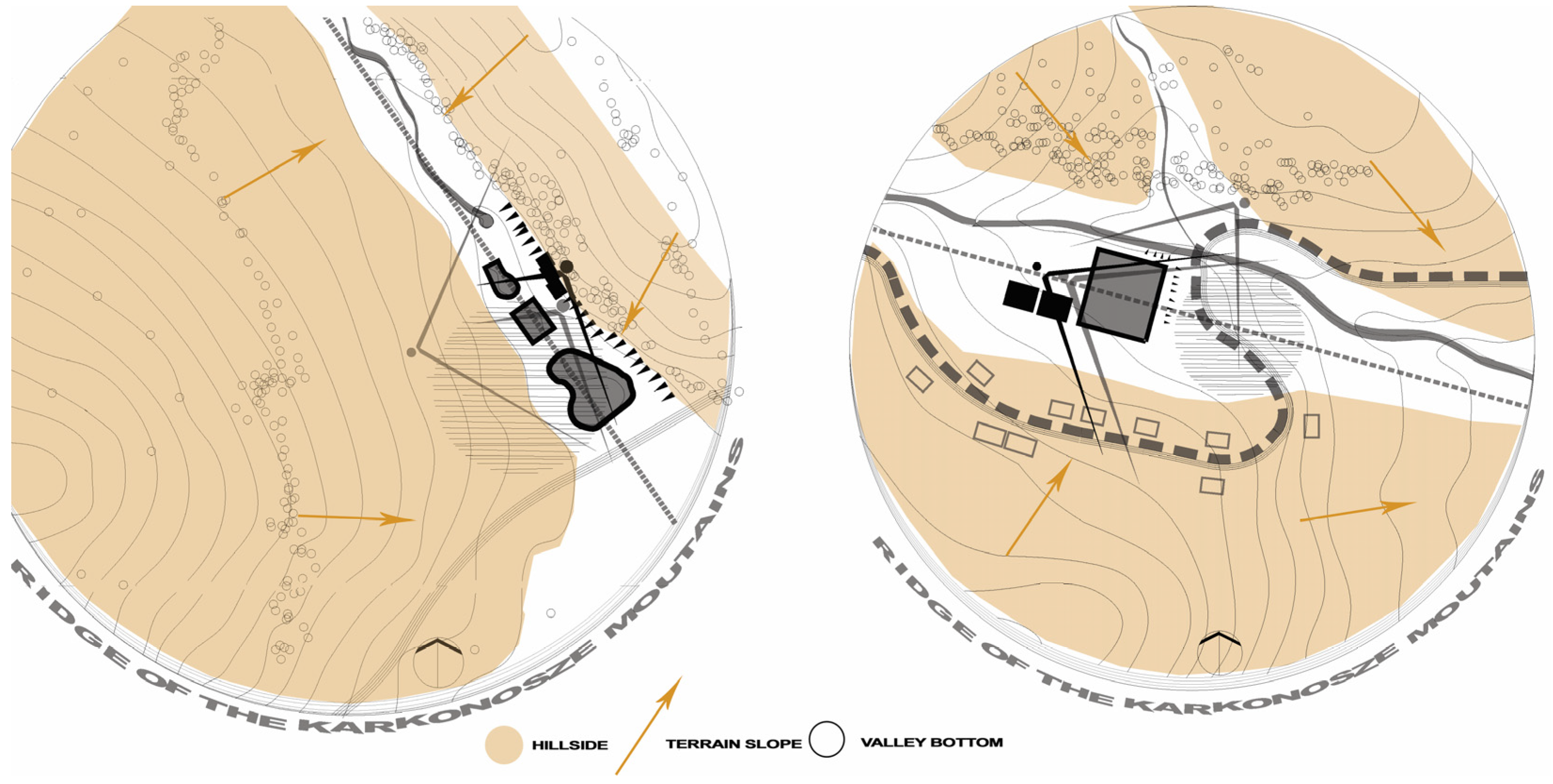

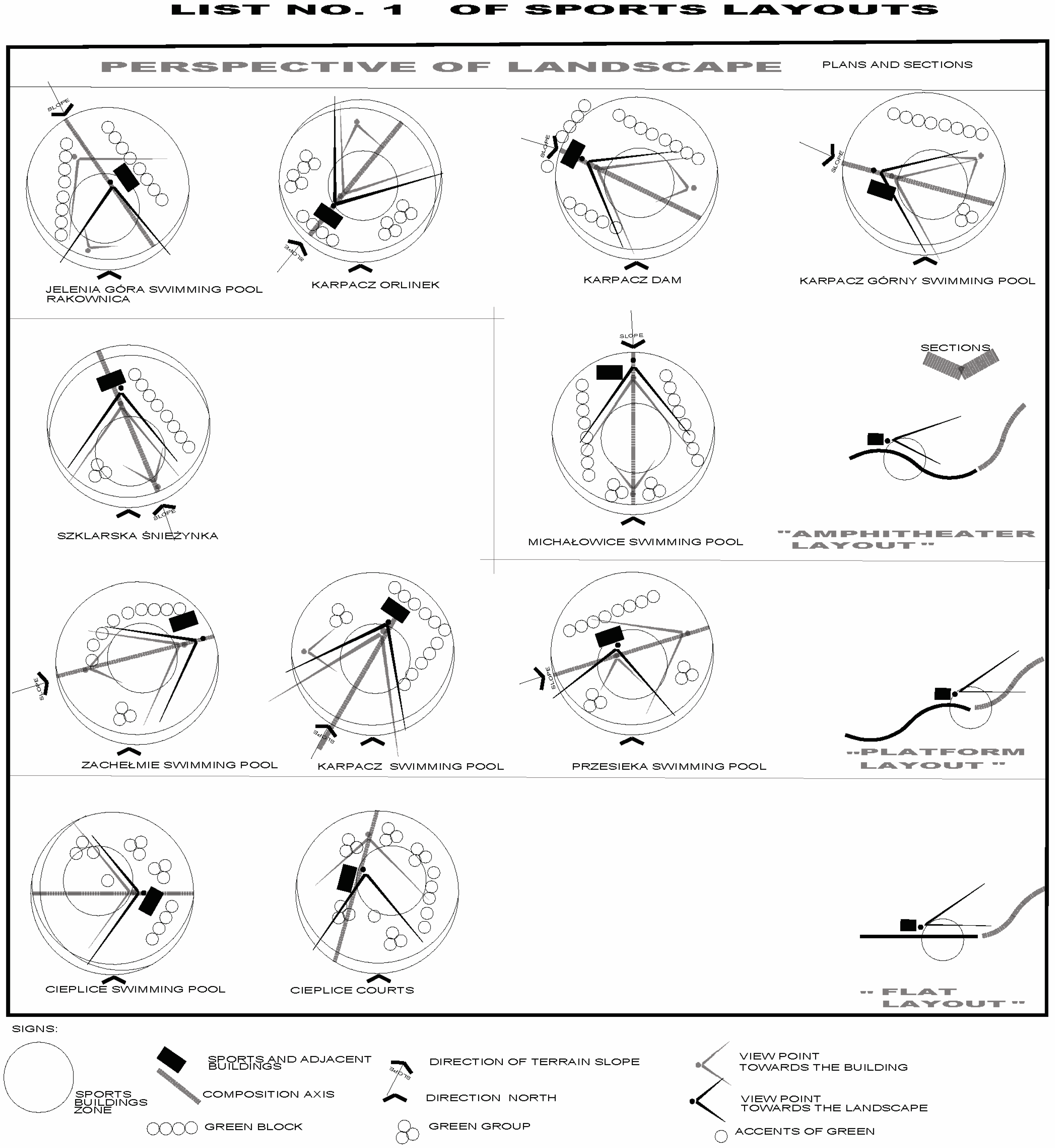

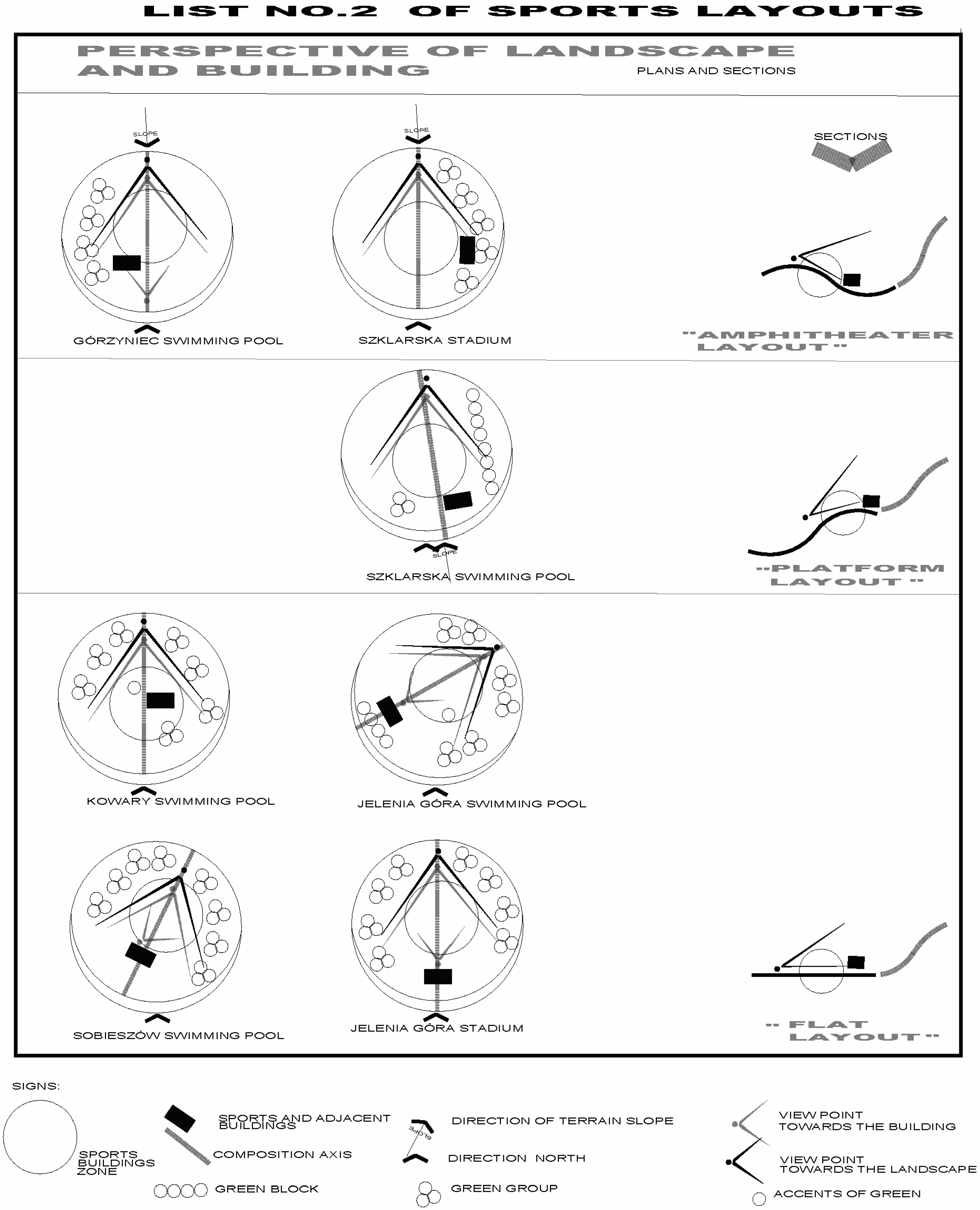

The techniques used to evaluate the research results include the interpretive–historical strategy and the logical reasoning method. The former was used for the assessment of sports facilities with historical roots. Its purpose was to interpret, among other aspects, the stylistic features of the facilities, as well as the social and economic consequences of sports investments. The method of logical argumentation, based on analysis and synthesis, was used to compare concrete examples of sports layouts. It allowed for the determination of similarities, common features between solutions, patterns of solutions, and finally, the selection of design rules. The analysis of qualitative data consisted of a review of the objects, their segregation according to the dominant function, locational features (platform, amphitheater, and flat layout), and a comparison according to their architectural and urban features. A synthetic presentation of the components of the study, as well as their dependencies and connections, is conducted in the form of tables. Images illustrating a typical approach to the sustainable design of sports areas are also presented (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).

A detailed analysis covered the sports complex layouts originating from health resorts, resorts, and sports stations in the Karkonosze Mountain district, including the Rakownica bathing area in Jelenia Góra (Jelenia Góra swimming pool Rakownica), the Orlinek complex in Karpacz (Karpacz Orlinek), the complex by the dam on the Łomnica River in Karpacz (Karpacz dam), the bathing area in Karpacz (Karpacz swimming pool), the bathing area in Karpacz Górny (Karpacz Górny swimming pool), the complex at the Śnieżynka holiday resort in Szklarska Poręba (Szklarska Śnieżynka), the swimming pool in Szklarska Poręba (Szklarska swimming pool), the stadium in Szklarska Poręba (Szklarska stadium), the swimming pool in Sobieszów (Sobieszów swimming pool), the bathing area in Kowary (Kowary swimming pool), the swimming pool in Jelenia Góra (Jelenia Góra swimming pool), the stadium in Jelenia Góra (Jelenia Góra stadium), the bathing area in Michałowice (Michałowice swimming pool), the bathing area in Zachełmie (Zachełmie swimming pool), the swimming pool in Cieplice (Cieplice swimming pool), the tennis courts in Cieplice (Cieplice courts), and the bathing area in Przesieka (Przesieka swimming pool).

The sports layouts were subjected to compositional, urban, and architectural analysis, taking land development and architectural form into account. The scope of the urban and architectural analysis was determined on the basis of Polish legislation (e.g., the Act of 27 March 2003 on spatial planning and development), among others [

1]. Urban and architectural analysis (i.e., analysis of the functions and features of buildings and land development) serves as the basis for administrative decisions. In particular, it concerned the layout of buildings, sports facilities, and accompanying buildings, as well as their communication. The urban and architectural analysis was supplemented with an analysis of compositional elements which occur in sports layouts and, at the same time, are characteristic of palace and park layouts at the foot of the Karkonosze Mountains. The compositional analysis concerned the open space, compositional axes, viewpoints, terrain configuration, and the organization of greenery. The analyses were preceded by the designation of the analyzed area (i.e., the area whose functions of buildings and development were analyzed in order to characterize the existing development). The boundaries of the analyzed area were marked on a topographic map on a scale of 1:10,000, in the 1965 coordinate system, considering a distance no less than the distance to neighboring buildings and in the zone of occurrence of the components of the sports complex. If the sports facility was separated from the neighboring buildings, making it impossible to determine the functional and spatial relations between them, the analysis was carried out in an area with a minimum radius of 125 m. This is an approximate minimum analytical distance in the case of sports layouts, in which the existing neighboring buildings can be considered as a significant compositional factor. The largest sports layouts covered an area with a radius of approximately 250 m or larger.

The focus of the research was issues from the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries; that is, from the period spanning the birth of the sports movement, its formation (sport in the modern era), and then its dissemination in the Karkonosze Mountains. This was due to the need to get to the root of the system comprising architecture, landscape, and sports. The 1920s feature the most analyzed examples of sports layouts that occurred in the history of the phenomenon and spatial arrangements, while later decades saw the evolution of sports. The time period was delimited by the end of the 20th century, as the undertakings in the field of spatial planning (as well as physical culture) are of a random, non-strategic nature.

This article merely presents the essence of extensive analyses, illustrating the most representative sports layouts. For the sake of readability, the conclusions are presented in an orderly and synthetic manner in relation to the model: the developed ideal of a sports facility. The most popular set of design standards, which are regularly updated, is Ernst Neufert’s handbook of architectural and construction design [

45]. However, in the first half of the twentieth century, when some of the first sports facilities were erected in the Karkonosze Mountains, attempts had already been made to formulate more detailed yet concise design principles. Carl Diem and Johannes Seiffert, in their book ‘Sportplatz und Kampfbahn’ [

46], as well as Konwiarz and Brandt in ‘Deutscher Sportbau, Deutschen Reichsausschuss für Leibesübunge’ [

47], presented principles for the creation of sports grounds.

For comparative purposes, however, a study entitled ‘Urządzenia sportowe projektowanie i budowa’ (Sports Equipment Design and Construction) [

48] was chosen, which provides a set of guidelines for the design of sports facilities. This compendium of knowledge comes from the period of construction of Polish sports investments in the Karkonosze Mountains. These guidelines are distinguished by the logic of argumentation, inspiring principles and directions in sports architecture, setting them apart from the formalistic compilation of norms.

3. Results

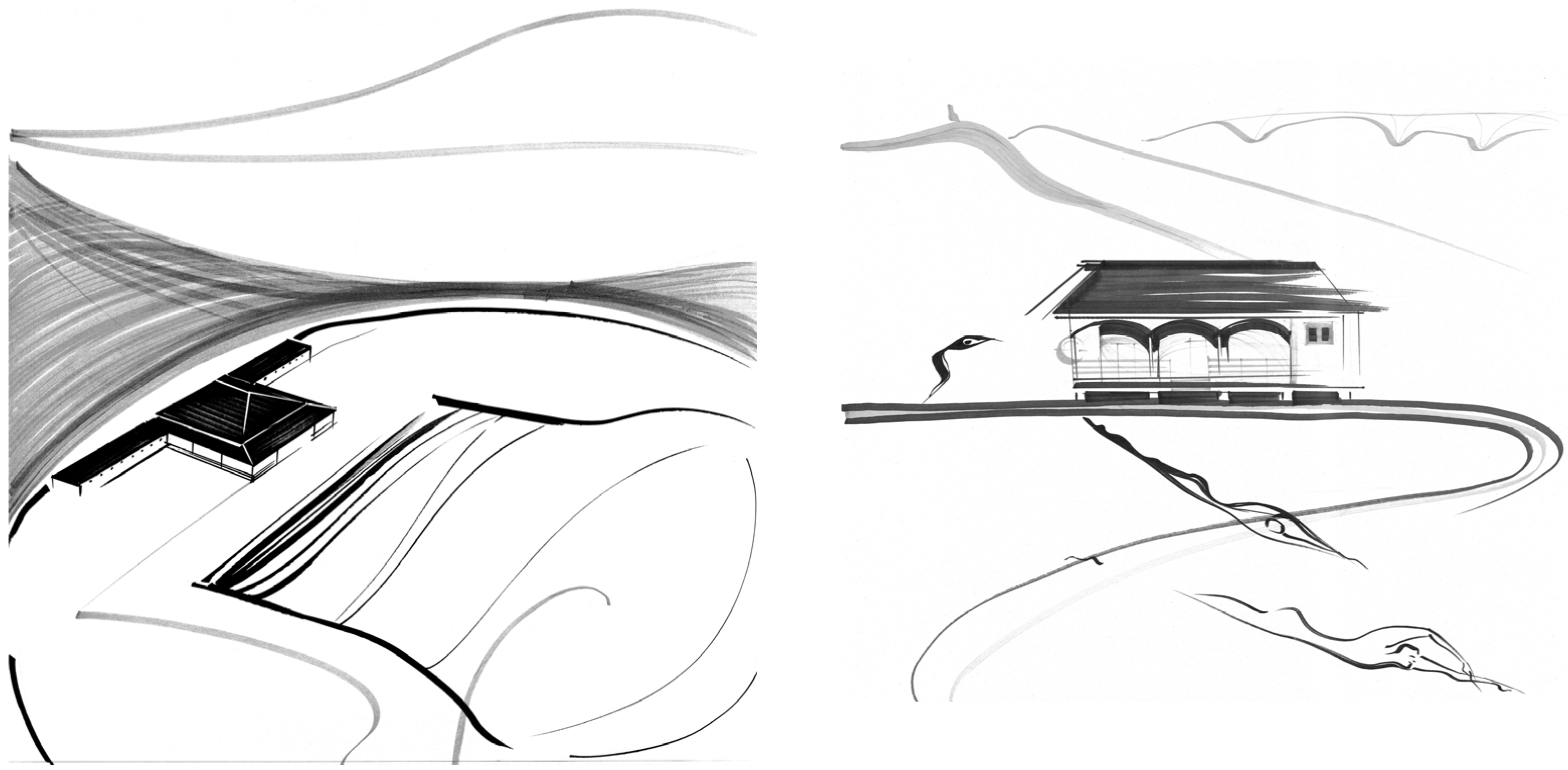

Sports layouts consist of the architecture of sports buildings, accompanying buildings, and nature, creating an urban–landscape composition. It is not the sports facilities individually but instead the whole arrangement that creates a timeless value. They are complemented by architecture bearing the rite of folk architecture and Alpine guesthouses, hostels, and sumptuous spas, co-creating an atmosphere of idyllic and perfection associated with the mountain landscape.

A list of diagrams showing sports layouts is provided below, taking into account the locations of buildings, sports and accompanying facilities, communication, open space, compositional axes, and viewpoints, as well as the organization of greenery, terrain configuration, and water elements. The proportions between built-up and empty space are clear, which can be useful in setting an imaginary boundary that guarantees the success of construction solutions (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).

The aim of this study is to present the design rules that were followed in the construction of sports layouts, with the hope of implementing them and extending them to other functions of the centers that make up the structure of the Karkonosze Mountains region. The desired effect—which, in some way, accompanies the implementation of the vision—is the shaping of a space that creates harmony with its surroundings.

As mentioned above, the list of rules is presented in relation to the twentieth-century model of a sports facility described in the study entitled ‘Urządzenia sportowe projektowanie i budowa’ (Sports Equipment Design and Construction) [

48]. From the description of sports equipment, a pattern for the correct solution of architectural problems in the mountain environment emerges:

- 1.

The principle of taking into account physiographic conditions, such as topography, greenery, water, insolation, and ventilation. According to this principle, the following solutions are recommended:

- -

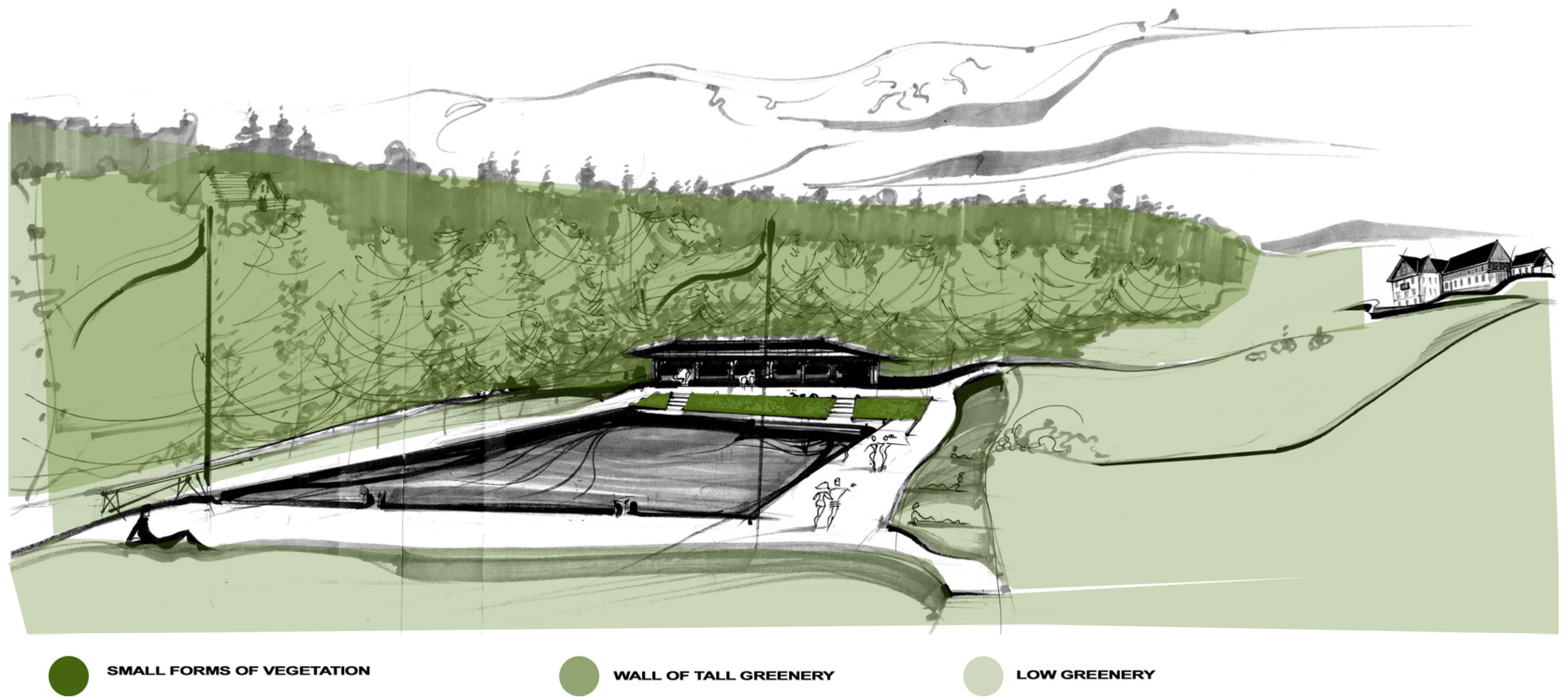

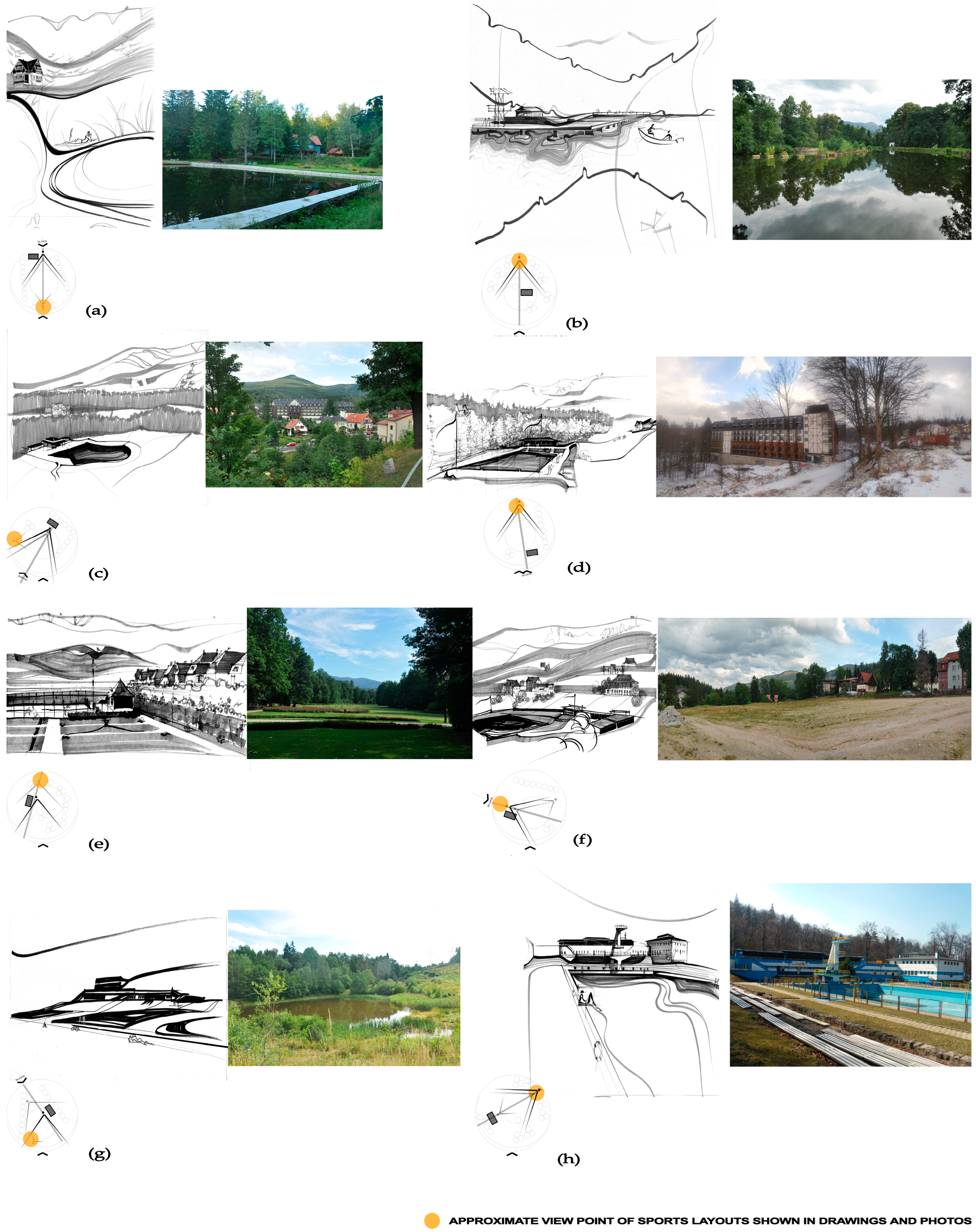

Ensuring an appropriate amount of greenery in the sports area. In the Polish norms of the 1960s in the 20th century, 30% of greenery in sports areas was defined as a minimum, and only in fulfilling the role of insulation between individual devices. Values as high as 50% are also prescribed. As a result of this requirement, the burden of issues related to the design of sports facilities has shifted from purely architectural issues to the field of green and landscape design (

Figure 3).

- -

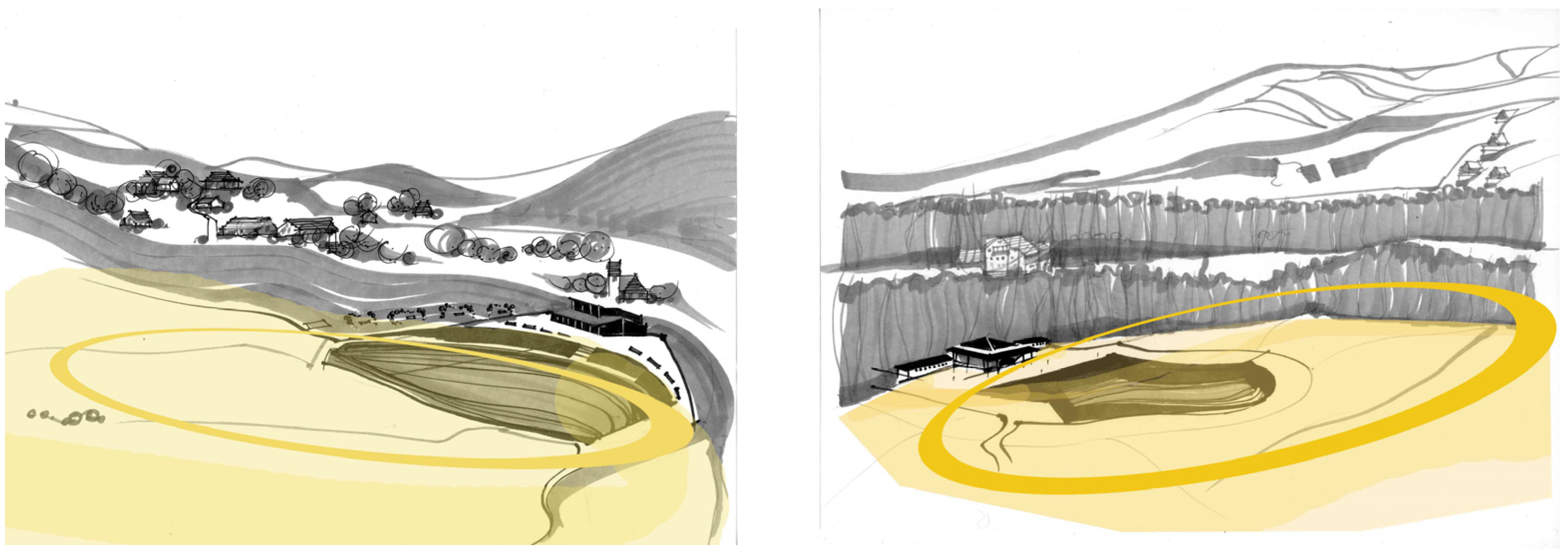

Comprehensive use of the invigorating and regulatory impact of greenery and water on the microclimate of sports grounds. The Karkonosze complexes, particularly the bathing areas, were often located in hollows in the terrain, such as in river valleys. On one hand, these areas provide good living conditions for vegetation, due to higher humidity; on the other hand, depending on the shape of the valley, cold air stagnation areas or cold air flow corridors can be considered detrimental. It is currently not possible to assess whether the selection of the ubiquitous greenery at that time stabilized the microclimate of the sports grounds. It is likely that the rows of trees acted as effective sun shades and wind protection (

Figure 4).

- -

Using a calm, uniform arrangement of greenery, which can affect the concentration and positive physical and mental well-being of the athlete. Manipulating the forms of massifs blocks and walls, edges, frames, divisions, and accents in order to achieve an artistic effect. The Karkonosze Mountain layouts were usually framed by forest complexes with an open panoramic view of the mountains, diversified with groups of freely scattered greenery, sometimes in rhythmic patterns (

Figure 5).

- -

The use of vegetation gradation in order to maintain the proportion between the building and the landscape. At that time, it was recommended that the immediate surroundings of the pavilions should be framed with small floral forms, which are more ornamental than the rest of the area—the pavilion should somehow grow out of the greenery, and the greenery should permeate the interior. Whether the maxim was indeed used in the Karkonosze sports layouts is difficult to verify due to the lack of accurate sources. For example, the sites in Przesieka and Szklarska Poręba prove that, in the vicinity of water reservoirs, low vegetation was sometimes arranged or natural vegetation associated with the aquatic environment was retained (

Figure 6).

- -

Adapting greenery to connect sports facilities with their surroundings on both a micro- and macro-scale (inviting greenery and framing views as part of larger forest and park areas) and, to the contrary, to isolate sports interiors while achieving the effect of transparency and spaciousness (peripheral greenery with view clearances). In particular, in the Karkonosze Mountains in Cieplice or Kowary, greenery played a role in effectively separating sectors characterized by various activities (

Figure 7).

- -

Proper orientation of sports facilities (especially competitive ones) in order to expose them to the health-promoting effects of sunlight and, at the same time, avoid glare for the spectator or exerciser, as well as exposure to strong winds. Usually, it is suggested that the sports field facilities and swimming pools should be located along the longer north–south axis, while the stands of the stadiums should be located on the west or south side of the playing field, in accordance with the natural slope of the area. Not all of the discussed objects in the Karkonosze Mountains were high-performance facilities. Perhaps, therefore, this condition was not always met strictly. On the other hand, the aim was usually to create a unique view of the landscape. In fact, analysts state that “every pitch, depending on its location, has periods of good and bad lighting during the day” [

48] (p.383). Meanwhile, facilities serving the dual purpose of competitive and spectacle activities—such as the stadium and swimming pool in Jelenia Góra and the stadium in Cieplice—are oriented according to the rules. On the other hand, the stands of the swimming pool in Cieplice were deliberately placed on the eastern side of the complex. In this way, an excellent view of the highest peaks of the Karkonosze Mountains was achieved (

Figure 8).

- -

Providing full sunlight to pool basins by moving shadow-casting buildings and trees away. It is likely that the bathing areas in Jelenia Góra and Karpacz Górny did not strictly comply with this condition. In addition, the surrounding hills, which protected against the wind, also hindered the late afternoon sun. In Cieplice, the proximity of the water surface and auxiliary facilities on the north side did not interfere with beneficial sunlight. Well-sunlit swimming pools were designed in Michałowice, Przesieka, Zachełmie, Jelenia Góra-Rakownica, and Karpacz (

Figure 9).

- -

Orienting winter sports equipment, such as bobsleigh tracks, toboggan runs, ski jumps, and ski slopes, along the north–south axis on slopes with northern, north-eastern, and north-western exposure, guaranteeing the most favorable snow conditions. The choice of the location right next to the forest, in the valley, was probably dictated by the optimal terrain profile, regarding which the shape of the artificial hill and the protection against the troublesome crosswind were adjusted (

Figure 10).

- -

Using the natural terrain for the optimal location of equipment, including auditoriums, in order to limit the translocation of earth masses. One of the most important features that distinguishes the Karkonosze sports complex layouts is the skillful use of the natural predispositions of the terrain. The bathing areas that benefited from their location in river valleys, including the advantages of greenery, sun, and topography, were Jelenia Góra swimming pool Rakownica, Karpacz water reservoir–dam, Karpacz Górny swimming pool, Karpacz swimming pool, Szklarska Śnieżynka water reservoir, Michałowice swimming pool, Zachełmie swimming pool, Przesieka swimming pool, Cieplice swimming pool, Górzyniec swimming pool, Szklarska swimming pool, Kowary swimming pool, Jelenia Góra swimming pool, and Sobieszów swimming pool (

Figure 11).

- 2.

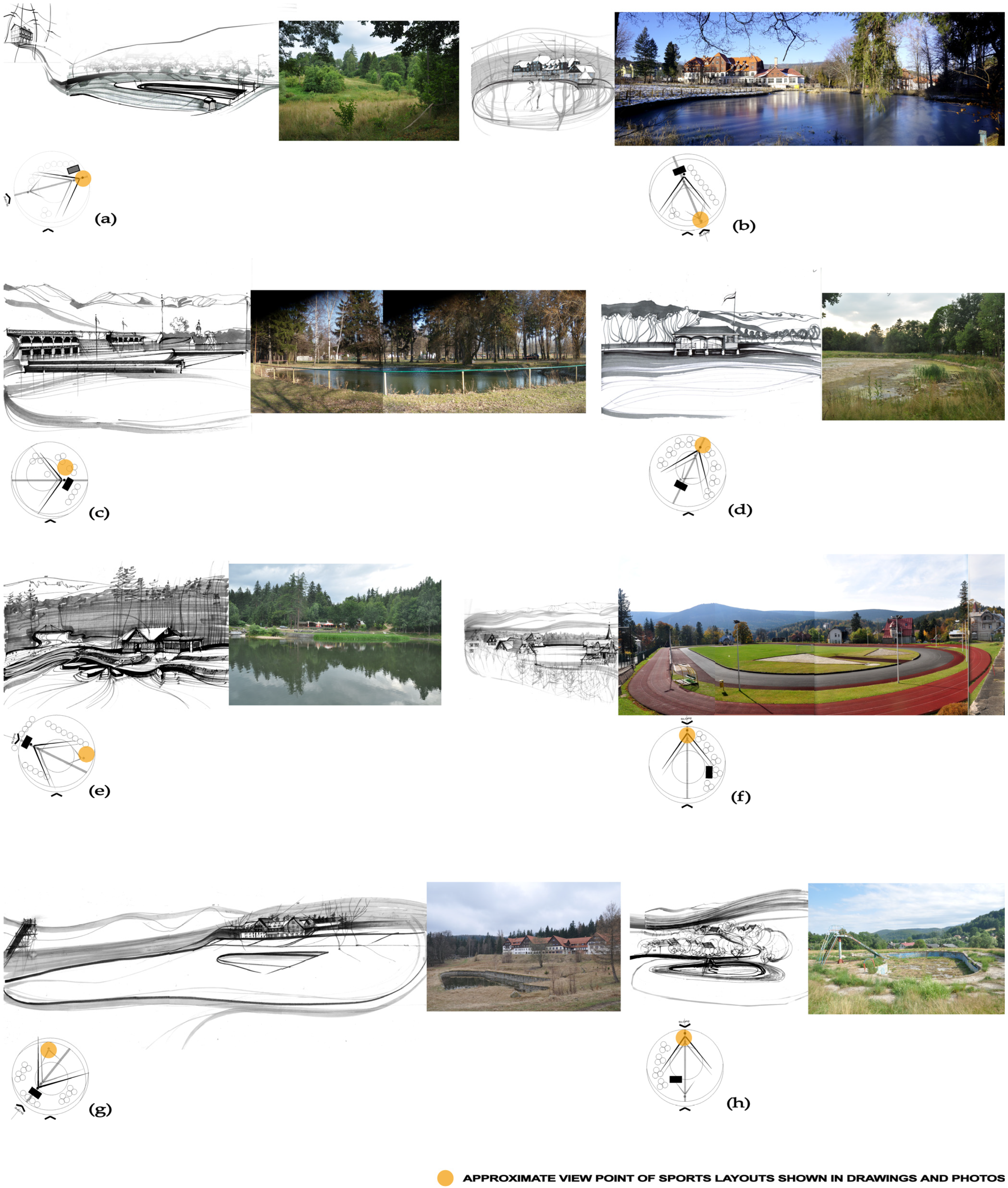

The principle of treating sports areas as a city-forming element. The intention was for sports areas to be one of the factors influencing the construction of the urban plan, referring to the layout of roads, avenues, and trails, among other aspects. The original arrangement of communication routes and historical buildings was achieved in a composition in accordance with the swimming pool in Górzyniec and the stadium in Szklarska Poręba (

Figure 12).

- 3.

The principle of ensuring the shortest connection between sports facilities and the nearest urban transport system. All of the Karkonosze Mountains complexes were efficiently served by road and railway routes, as well as a system of tourist trails.

- 4.

The principle of multi-functionality and connections with other social devices, allowing for the correlation of sports facilities with tourist facilities. When designing the investment, its costs (including operational costs) were anticipated. Taking into account economic considerations, it was recommended, for example, to use sports fields and playgrounds in a variety of ways as places for games and exercises and in winter for ice skating. This was a standard consideration in the organization of the i.a. Śnieżynka sports complex in Szklarska Poręba and at the dam on the Łomnica River in Karpacz. It was advisable to use auxiliary equipment that forms an integral part of every sports facility (e.g., changing rooms, warehouses, ski rentals, workshops, changing rooms, hygienic and sanitary rooms, medical aid points, and catering facilities), and it was preferable to locate sports centers next to tourist facilities. This is how most of the sports facilities in the Karkonosze Mountains were created. Often, the existing hostels, holiday resorts, guesthouses, and hotels gave the sports complex a regional flair, as is the case for the Orlinek complex in Karpacz (

Figure 13).

- 5.

The principle of adopting the neutral architecture of auxiliary buildings.

The architecture of buildings serving typical recreational sports facilities (in both summer and winter) was to present a balanced appearance, undoubtedly adapted to the requirements and characteristics of individual types of sports. The free-standing light pavilions surrounded by greenery, even of a seasonal nature, are indicative of this role. Among the objects in the Karkonosze Mountains, one can distinguish their restrained form, with some common summer and winter pavilions:

- -

By the port (Karpacz dam and Kowary swimming pool);

- -

By the bathing areas (Sobieszów swimming pool, Zachełmie swimming pool, and Karpacz Górny swimming pool);

- -

By the playing fields (Jelenia Góra stadium and Cieplice tennis courts);

- -

By the shooting ranges (Cieplice swimming pool);

- -

By the downhill and cross-country ski trails (cable car stations and ski lifts in Szklarska Poręba or Karpacz and tourist shelters in Jakuszyce);

- -

By the toboggan runs and slides (Karpacz toboggan run–Karpacz dam);

- -

By other infrastructure for winter sports (observation towers, buildings at the start and finish of the routes, workshop rooms, and storage rooms) (Karpacz Orlinek).

Some of these objects were multi-functional buildings, including stands, changing rooms, hygienic and sanitary rooms, a club area, an entrance area, eateries, and terraces (the swimming pool in Cieplice, Jelenia Góra). Other single-use buildings with the abovementioned functions were also included in the land development system (the stadium in Jelenia Góra from the first phase of construction) (

Figure 14).

- 6.

The principle of economy in the use of color, taking into account naturally occurring colors. It was worth imitating the juxtaposition of the dominant greenery of different shades and changing colors of the seasons through the monochromatic, light construction of buildings and sports structures, paths, beaches, playgrounds, and game areas, as well as the contrast of the development with the dark tones of the wood of the regional architecture. Most of the sports facilities in the Karkonosze Mountains were erected in the spirit of this principle. The juxtaposition of antagonistic colors (the dark outline of the building, white of the building detail, and powder of snow) gave the winter sports complexes (e.g., in most of the ski resorts in the Karkonosze Mountains) a special uniqueness.

- 7.

The principle of linking sports facilities with the natural landscape; or, in other words, adapting sports facilities to the environment. This determined the composition of entertainment and leisure equipment, training, and even spectacle equipment, with the obvious consideration of general sports requirements.

Here are some of the possible design decisions:

- -

Adopting the centrifugal direction of the composition, with views of the landscape distinguishing features visible in the distance;

- -

Establishing the framework of the composition reaching beyond the boundaries of the plot, including the immediate neighborhood and distant views of hills, forests, and silhouettes of houses;

- -

The use of a sequence of plans, consisting of groups of trees, with different intensities of color and light;

- -

Establishing a sports facility as functionally, ideologically, and artistically dominant, especially with respect to monumental spectacle assumptions and, vice versa, the free dispersion of recreational possibilities among the meanders of nature.

- 8.

The principle of separation of trainees and spectators, as well as the observance of other technological requirements resulting from the operation of the facilities. This dictate is difficult to assess considering the appearance of objects that no longer exist.

- 9.

The principle of individuality in the design of sports facilities depending on the sport discipline. A set of individual features representative of buildings related to separate sports disciplines is obvious. There were several main groups of sports facilities in the Karkonosze Mountains: (a) outdoor water facilities, (b) sports fields, and (c) winter sports facilities. These were complemented by sports halls, shooting ranges, indoor swimming pools, and a network of mountain roads, which were served by motorcycle and bicycle tracks, among others.

However, due to the diversity of towns in the Karkonosze Mountains, it is not possible to describe these groups with a similar function (and, often, even a similar location) in one scheme. Rather, they are types full of variants and varieties. In addition, a distinction can be made between sports facilities for mass and recreational use, each of which is governed by its own laws.

In summary, it remains to mention the analogies to classical models visible in the concepts of modern sports layouts. Plato’s principle was to ensure the greatest possible accessibility and integrity of devices serving the common culture. On the other hand, the competition equipment was located on the outskirts of housing estates. Physical culture facilities were located in sacred groves, and those for educational reasons in places distinguished by beautiful landscapes. The first solutions were limited to a modest arrangement of training areas in the shade of trees. Later extensions of the complex bore witness to a high level of architectural thought. The simplicity of the construction in the Hellenic period encouraged the economical use of the slope and terrain (e.g., placing stands between the elevations). Attention was paid to the plastic shape of the buildings, their illumination (with southern light penetrating the interiors), good visibility, and representativeness of the assumptions. It can be assumed that the abovementioned criteria were also the goals of the architects of the Karkonosze Mountains complexes.

The application of the above principles during the design, construction, and use of sports facilities has contributed to the creation of places that are characterized by naturalness and individuality, despite the use of similar compositional elements. This was probably influenced by the geometry of the layouts, in which a significant share of natural elements is noticeable: topography, greenery, water, and the sun, sky, or wind. These are both a component of the architectural idea and the environment. There is a noticeable organizational rule imposing the location of a sports facility in each mountain village. Facilities dedicated to general winter and summer sports were erected closer to the city center, while more peripheral locations were chosen for specialized facilities. The sports layouts maintained (for economic reasons) the trend of minimalism, taking advantage of the picturesque location and natural surroundings to create functional and artistic architecture. The solutions resulting from the organization of engineering knowledge were intensified by emotional bonds with the environment. Modern technologies for constructing sports facilities were used, juxtaposing them with the form of architecture derived from the tradition of local construction. The architecture complemented its surroundings in a non-overwhelming way, confirming the thesis that it is possible to regulate the relationship between landscape, nature, technology, and humanity.

4. Discussion

So, did the principles presented here significantly influence the overall perception of the transformed mountain space, and can this course in the development of mountain areas be considered sustainable?

We cannot ignore the role of sports in the development of regional and sports buildings that attracted connoisseurs of tourism and sports. This resulted in the creation of transport connections, allowing for the migration of people to mountain towns, including representatives of the worlds of literature, science, and sports, as well as the creation of modern facilities and equipment serving both tourists and the local population. Sports investments in times of both prosperity and crisis turned out to be a choice that resulted in improved quality of life for residents, the appearance of housing estates, and increased prestige. Sports—especially winter sports—fueled the development of the region, used the resources of existing villages and increased their attractiveness, made it easier to survive the crisis, increased the area of tourist penetration, and extended the holiday season from summer to year round. In the Karkonosze Mountains, sports infrastructure and architecture were built following the patterns of the most famous centers, such as Davos, St. Moritz, and others. At the beginning of the 20th century, some villages boasted sports infrastructure at the highest world level. The Karkonosze Mountains region is famous for the architecture of its elegant resorts and smaller, intimate winter sports stations. Szklarska Poręba then became one of the world’s largest winter sports and tourism centers. The social and economic benefits of the constructed sports facilities are intertwined with compositional and aesthetic benefits. It is worth emphasizing that a characteristic feature of the first tourist and sports facilities in the Karkonosze Mountains was their location amongst the greenery. Shelters associated with sports infrastructure were usually located in the most attractive corners of nature. When designing tourist facilities, the natural and scenic values of the newly appropriated nature were taken into account. The buildings were erected on large plots, often naturally undulating. Landscape gardens were designed around the buildings. The ideal was that of English park layouts, in which naturalness, consistency with the landscape, and atmosphere and sentiment played the most important roles in the arrangement. Sports facilities occupied a special place. Surrounded by tourist buildings, sports and recreational areas such as ski and toboggan tracks, bobsleigh tracks, ski jumps, ski lifts, tennis courts, swimming pools, and ice rinks were developed. Most of these facilities were located outdoors, which contributed to a favorable balance of green areas in the village. They usually took advantage of the natural predispositions of the area in terms of topography, water, and vegetation cover, allowing for only minimal interference with the environment. In this famous mountain region, sports functions were boldly introduced into the interiors of buildings, districts, and housing estates, utilizing existing roads, squares, meadows, streams, and ponds.

A common feature of the architectural and planning solutions introducing sports functions into the tourist space of the Karkonosze region was the use of the advantages of the natural surroundings and their integration into the existing surroundings of neighboring residential and tourist buildings.

In light of the research conducted and public perception, this is not a subjective view. The high aesthetic level of the Karkonosze villages has been appreciated by numerous tourists. Szklarska Poręba even gained the nickname “the pearl of the Karkonosze Mountains.” However, no criticism of sports facilities in the Karkonosze Mountains has been published in the literature to date [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Perhaps this was due to the intricacy and simultaneous conciseness of the sports layouts, which were skillfully blended into the surroundings. The tendency to build in a discreet manner, as is visible in the sports layouts, thus not exposing the buildings but rather seeking balance with the mountain nature and subordinating architecture to the landscape, was in line with the urban planning principles of that time [

39,

40,

46,

47].

The sports layouts were a compromise between the protection of nature, architectural heritage, and the development of the tourist economy. This approach softened the contact between modern structures and traditional landscapes. At present, this philosophy could help to reduce conflicts [

23] resulting from the pressure of ski traffic (which Alpine countries also face) [

24,

25,

34]. The design principles presented here do not translate literally into formalized design systems. Due to the individual properties of each location, these are specific compositional and spatial combinations of green, water, buildings, and viewing axes. This tendency confirms the thesis regarding the probable impossibility of establishing strict criteria for aesthetic urban composition [

33]. The nature of sports layouts, in which greenery dominated, proves the universality of this component, which influences the favorable balance of undeveloped spaces and increases the aesthetic values of the environment and the need for contact with greenery, as commonly emphasized in the literature on the subject [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32].

Due to the implementation of the concept of re-activating design standards, the Karkonosze Mountains could continue the achievements of architectural thought practiced in the 19th and 20th centuries, and applying solutions that were abandoned several decades ago can be expected to create opportunities for the region’s existence and development.

5. Conclusions

The sports layouts that emerged in the 20th century in the Karkonosze Mountains created a harmonious whole, taking into account orderly relationships, conditions, and requirements, as follows:

- -

Functional (dictated by the development of modern sports);

- -

Socio-economic (communities in the years of crisis and prosperity);

- -

Environmental (landscape);

- -

Cultural (the protection of nature and local building traditions);

- -

Compositional and aesthetic (the arrangement of architectural and urban elements).

The sports layouts did not negatively affect the cultural, natural, and landscape values of the tourist region, which is particularly susceptible to degradation. Rather, they strengthened the attractiveness and competitiveness of the region.

The above characteristics of sports layouts correspond to the features of spatial order defined by law [

1]; in particular, ‘spatial order involves the shaping of a space that creates a harmonious whole and takes into account the orderly relationships, conditions, and requirements in the functional, socio-economic, environmental, cultural, compositional, and aesthetic dimensions’.

In the course of the research, functional, socio-economic, environmental, cultural, and compositional aspects were analyzed. The spatial arrangements were recorded in accordance with their essential components and features of building and land development. Urban architectural and compositional analyses of important components of sports layouts—including the type of development (parameters and form), communication of systems, natural elements (greenery, water, and topography), and composition elements (compositional axes, viewpoints, and undeveloped space zones)—as well as an analysis of local conditions and functional requirements indicated the existence of regularities between them (i.e., relationships). Regularities between components, conditions, and requirements were presented in the form of rules, which can be considered as principles creating spatial order, as the sports facilities created according to these principles present a positive spatial effect in the environmental, social, and economic dimensions. Spatial order is the overarching principle of sustainable architecture. The universality of the presented principles allows them to be applied to a variety of locations. In particular, for mountain conditions, three types of locations were specified (i.e., platform, amphitheater, flat layout, etc.).

Regarding the possibility of establishing more stringent rules, we should agree with the specialists in the field of planning regulations who state that the assessment of the analyzed area is always subjective [

49]. It is therefore necessary to leave creative freedom to an educated designer with professional knowledge. This thesis is confirmed by the individual nature of sports layouts.

We should also agree with studies that emphasize the role of greenery and composition in architectural and urban concepts. These aspects constitute the basis for the interpretation of a significant part of the rules. Summarizing the history of construction development up to the 1960s and formulating recommendations, Romuald Wirszyłło concluded that, despite the spread of physical education and, consequently, the need to build for mass—leading to typification, simplification, and cost reduction—it cannot be conducted “to the detriment of functional and artistic values.” He pointed out that the issues of the composition of sports facilities are no less important than purely technical matters [

48] (p.480). This conclusion seems to be valid due to the growing popularity (as mentioned earlier) of organizing sports facilities on a minimal surface or cramming them into closed volumes for multiple purposes. These comments should generally also be applied to the development of architecture in mountain environments. According to the above principles, the course of development of mountain areas should aim to arrive at a state that can be characterized as a state of balance (aurea mediocritas).

It should be added that sports facilities in the Karkonosze Mountains deserve further research; however, a necessary condition is access to other archival materials, if they still exist.

The above conclusions should be used as design guidelines for architects when considering new tourism and sports investments. Investments should create the opportunity to provide the best possible conditions for recreation and life for local communities, while maximally preserving the state of the environment. Here are some practical recommendations that can be expected to bring benefits in this regard:

- -

A comprehensive approach to development not only of the village but also of the region;

- -

The creation of homogeneity within the region;

- -

The limitation of polymorphic, heterogeneous structures in small mountain locality, and densities that characterize the city;

- -

The zoning of buildings of both larger dimensions, smaller scale, and those located in the center of the village;

- -

Achieving the compactness of settlement units while maintaining the bond between centers with centralized services and the province (consider, e.g., Jelenia Góra);

- -

Preserving the emotional factor, evoking a positive attitude toward a specific type of construction;

- -

Preventing the loss of the factors that lead one to come to the mountains (e.g., sun, snow, climate, air, landscape, etc.).