1. Introduction

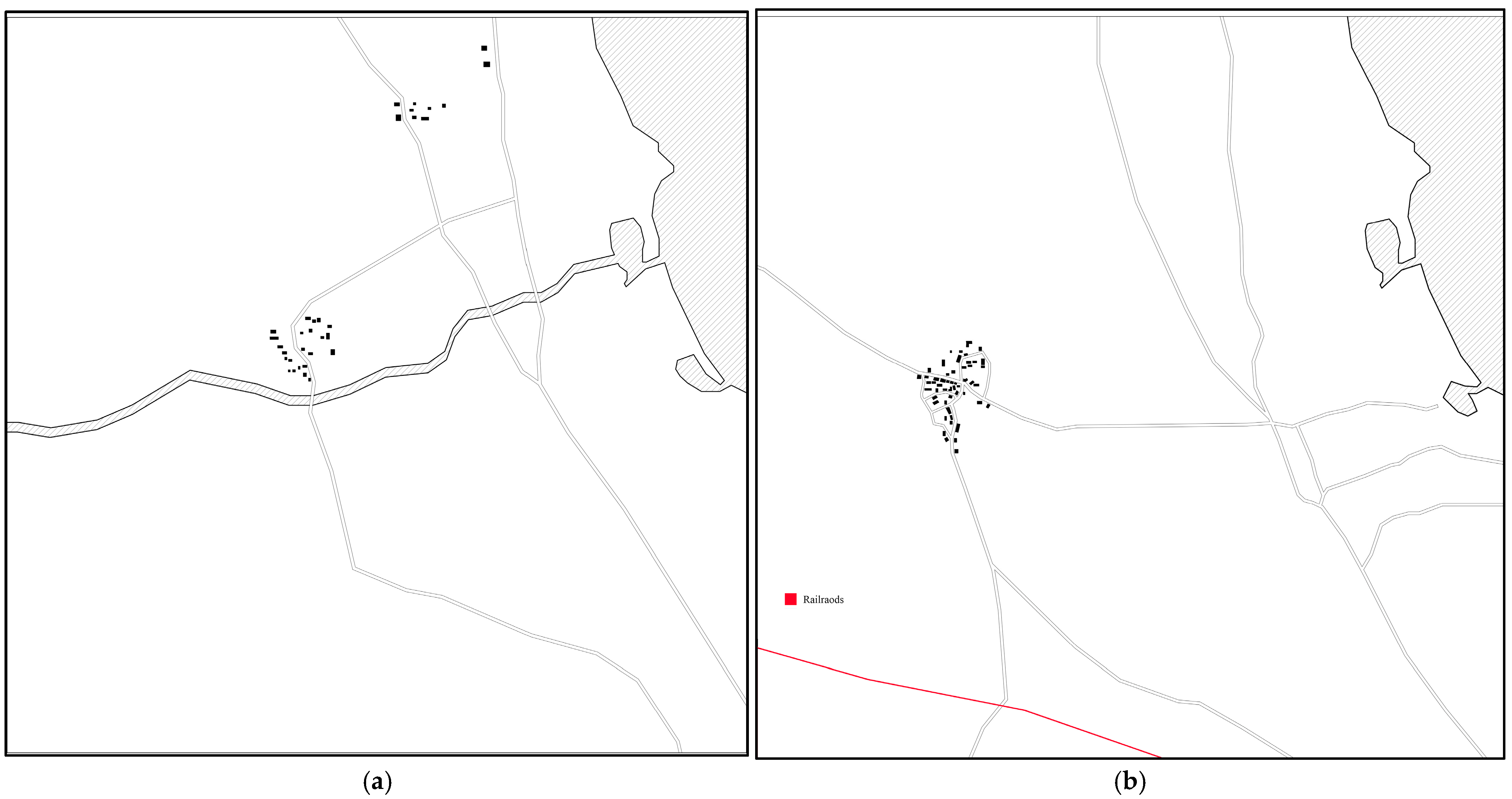

Due to its geopolitical significance and strategic location, Cyprus has historically attracted the attention of many prevailing powers, including Phoenicians, Greeks, Romans, Byzantines, Franks, Venetians, Ottomans, and the British. With its natural resources and strategic geographic value, the island is an important steppingstone and a safe harbor in the Mediterranean Sea, among Asia, Africa, and Europe (see

Figure 1a). The island has been shaped both culturally and physically by the successive rule of various civilizations over time, significantly contributing to its tangible and intangible heritage.

Up to the late nineteenth century, Cyprus was ruled by the Ottoman Empire for more than three centuries. Apart from expanding its commercial horizons, Britain regarded Cyprus as an opportunity for advancing its military and economic objectives in the Middle East and as an excellent naval base for safeguarding the Suez Canal [

1]. It was also necessary to maintain control over the security of India and the commercial route that led there for the safety of its navy’s refueling, route maintenance, and port access. Moreover, Cyprus was an important strategic storage facility for British products in the context of the Euphrates Valley Railway Project [

2]. An agreement with Britain was made in 1878 as a result of mounting pressure on the Ottoman Empire and its deteriorating economy, the Ottoman Empire gave the administration of the island to the British, but the ownership of the island was not granted to them [

3]. In 1878, the British began to rule Cyprus, until 1914, when it was formally annexed, and in 1925, it was classified as a British Crown Colony, until 1960, when Cyprus gained independence [

1]. In the first months of British rule in 1878, the primary focus was on conducting studies to gain a deeper understanding of the island, enabling more effective governance and prompt interventions. The island’s limited forests, the mountain ranges that run from west to east, the Mesaoria plain between them, the restricted access to water resources, its outdated transportation system, warm climate, range of trade goods, and its potential as a key Mediterranean port were among the first things observers noted about Cyprus [

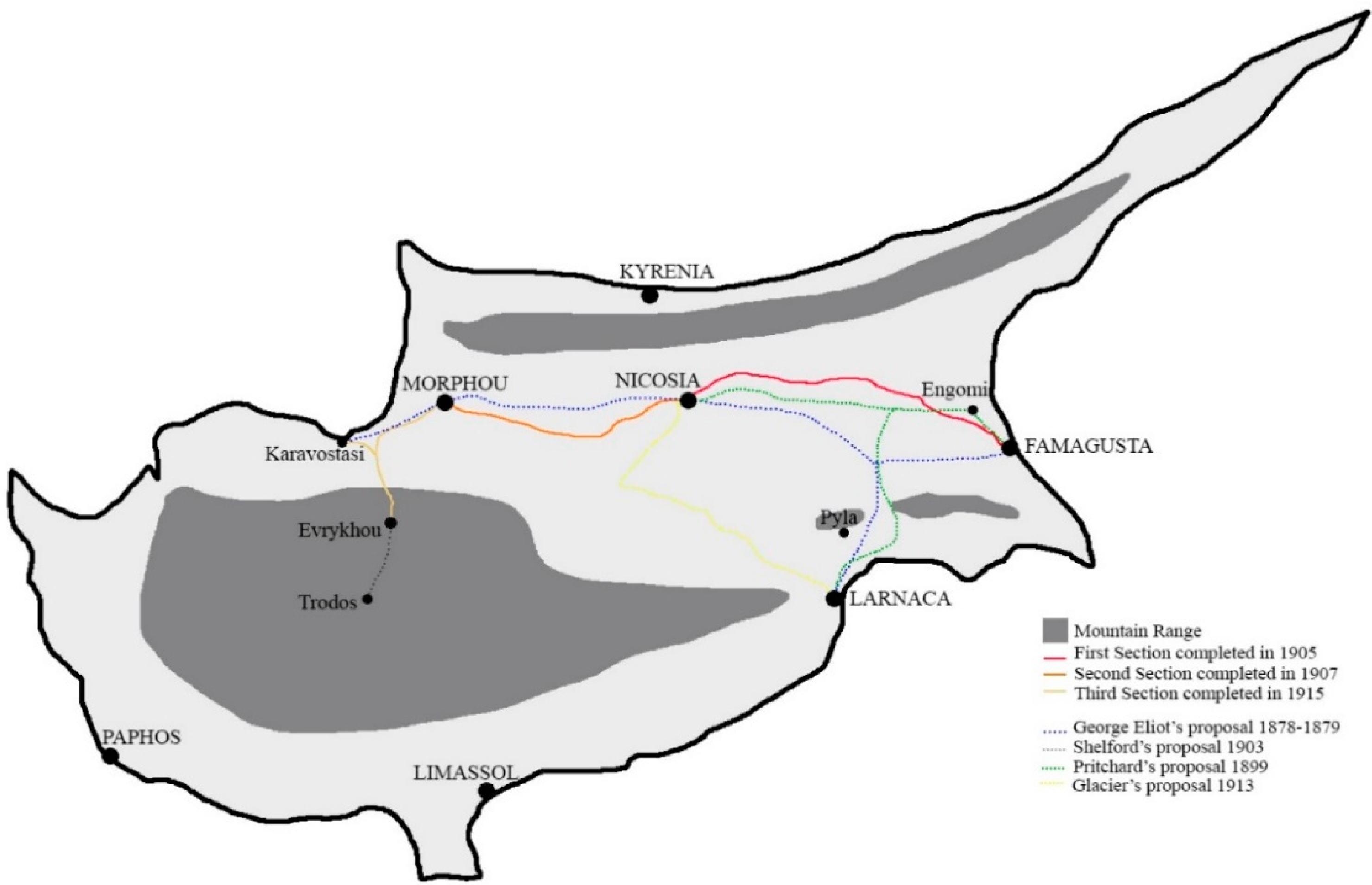

4]. Lieutenant-General Sir Garnet Wolseley, appointed as the first British High Commissioner of Cyprus, conducted initial surveys that included proposals for the development of connecting roads between the administrative center Nicosia (see

Figure 1b), inland transportation routes, and the ports of Famagusta, Kyrenia, and Larnaca [

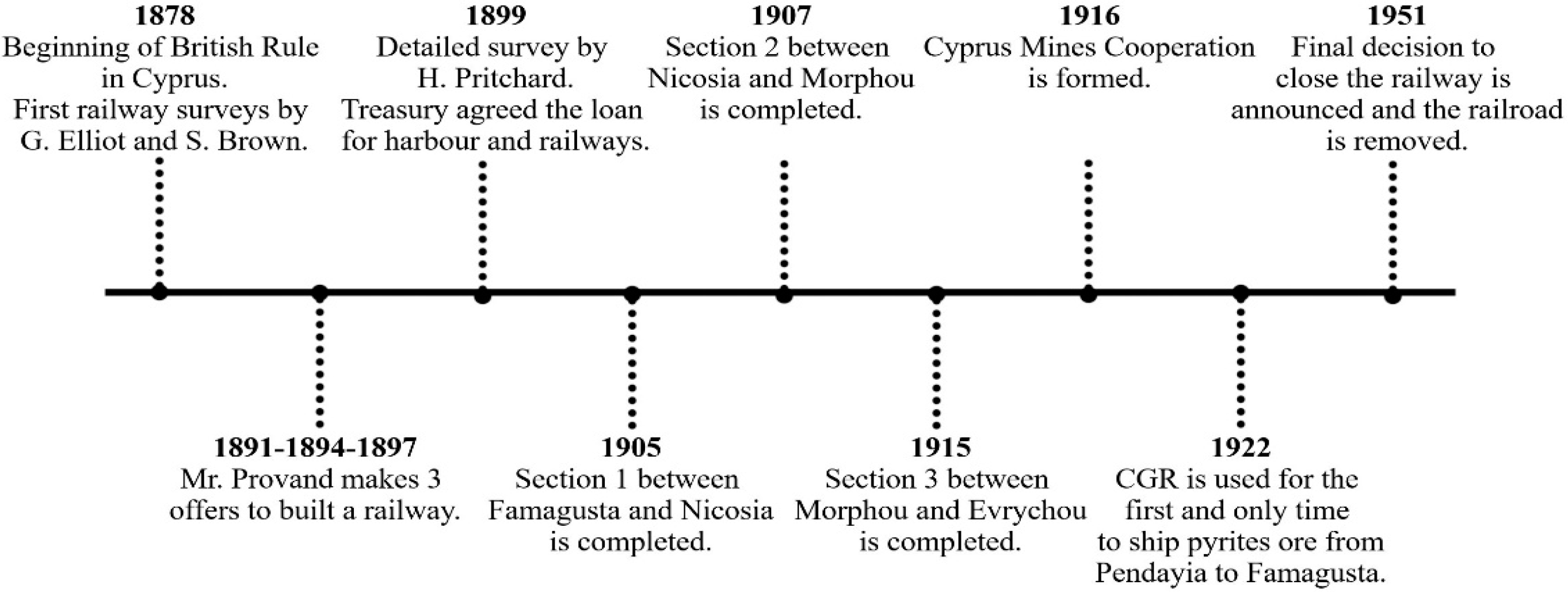

5]. Detailed surveys helped the British commissioners to collaborate with Public Works Department (PWD) and to decide the urgent areas to be developed. Transportation and irrigation systems were decided as the areas with great importance that need development for efficient agriculture and movement of people and materials. The planned transportation initiatives encompassed the development of existing vehicular roads, the enhancement of current harbors, and the establishment of a railway. This paper specifically examines the railway that operated in Cyprus from 1905 to 1951 and discusses various theories regarding its potential impacts on the island’s architectural and urban development. Examining how colonial legacies influence cities, urban spaces, informal settlements, and surrounding areas, the focus is on postcolonial growth in urbanization. This perspective is critical for comprehending the island’s shared history because it shows how socioeconomic mechanisms, planning, and governance from the colonial past influenced urban growth and geographic disparity. This study employed a multi-layered research approach that includes a literature analysis and the collection of textual and visual data. A qualitative and cartographic analysis was conducted to identify patterns and linkages between the two in order to give a comprehensive knowledge of the influence of railway infrastructure on urban transformation.

Railways in British Colonies

Especially with the Industrial Revolution, the construction of railways became faster and more essential. Faster, because with the developed machinery, the production of rails and other equipment essential for the railways became easier. The abundance of required metals and raw materials also sped up the process. The need for raw materials around the world increased, so as a contemporary mode of transportation, railways became essential in developed areas. With its precise schedules and a new understanding of time and distance, the train prompted a “mobility revolution” [

6].

It is acknowledged that the British Empire was one of the world’s greatest colonizers [

7] and their success in transportation and their knowledge of it are important aspects that supported their development. The rush and competition of colonizing powers in the early 20th century accelerated the growth of the transport sector. An efficient transportation infrastructure was required to move extracted goods, people, military equipment, food items, etc. to maintain and expand the empires. It was crucial to move supplies within the colonies, between the colonies, and between the colonies and the mainland. Due to its significance, railway planning has always been a special priority for British administrations. Railroads were usually the colonizer’s biggest investment expense in British colonial finances. For instance, in Ghana from 1898 to 1931, railway spending accounted for around 31.4% of all state spending, indicating a substantial portion of government investments [

8].

Many cases indicate that inner lands with no access to harbors were connected to harbor cities to transfer the products and people to and from harbors for further transportation, such us the Indian railway routes, which were designed to connect the central provinces to the port cities, optimizing the flow of traffic. Lahore, a major railway station in the country, was linked to the port cities of Bengal and Karachi, as well as to Mumbai (formerly known as Bombay), and from there, the railway network extended further south to Nagapattinam, which served as a key southern port [

9]. Similar to this, British colonial rule in Nigeria chose to construct a railway network in order to investigate and broaden trade to the interior of the nation, where waterways were unable to travel [

10]. As an island, Newfoundland was another British colony to become familiar with railroads. The colony’s primary source of income was fishing, which is why the shores were highly populated. The optimistic predictions of large agricultural areas and mineral and timber riches in the inner part of the island gave rise to the idea that building a railway across the island would allow access to these resources. Mining and logging would create jobs for those who could no longer sustain themselves through the fisheries, as well as new investment options for merchants and other businesses wishing to lessen their reliance on a sector with little opportunity for expansion [

11].

3. Results and Discussion: Impact of Railway Infrastructure on the Development of Settlements and Spatial Organization

Investments in transport improve accessibility, impacting urban land use and drastically altering the shape of cities [

25]. Railways and the buildings serving the railways can affect the development of the cities on different scales in different ways. Several studies have proven that areas with strong rail connectivity have faster rates of economic expansion, consequently, funding transport infrastructure is an effective strategy to promote economic growth [

26]. The European Landscape Convention states that landscapes are generally characterized as regions that are influenced by both natural and man-made influences [

27]. Among these human factors, railway infrastructure is an important one that includes the building of tracks, stations, tunnels, and bridges. These factors not only have a direct effect on the surroundings but also help to reshape the territories along the route of the tracks. A road or train passing through a cultivable area will inevitably promote economic growth [

28]. The promotion of growth and development is frequently attributed to transportation infrastructure as the argument is based on the direct reasoning that having access to markets and ideas leads to faster growth and the fact that railways and other infrastructure were historically built during times of strong economic expansion in Western Europe and the US lends credibility to this theory [

29]. The direct effects of railroads included reduced shipment expenses, allowing resources for other uses to expand the size of the market, enabling producers and agriculture to pursue greater work, spreading manufacturing abilities, promoting the growth of the ironwork, and energizing other economic subsectors through resource demands for building systems [

30]. According to the findings, rural areas in Sweden with local railway connections between 1860 and 1917 saw 100–300% higher industrial production and employment in the majority of industrial sectors than those without [

31].

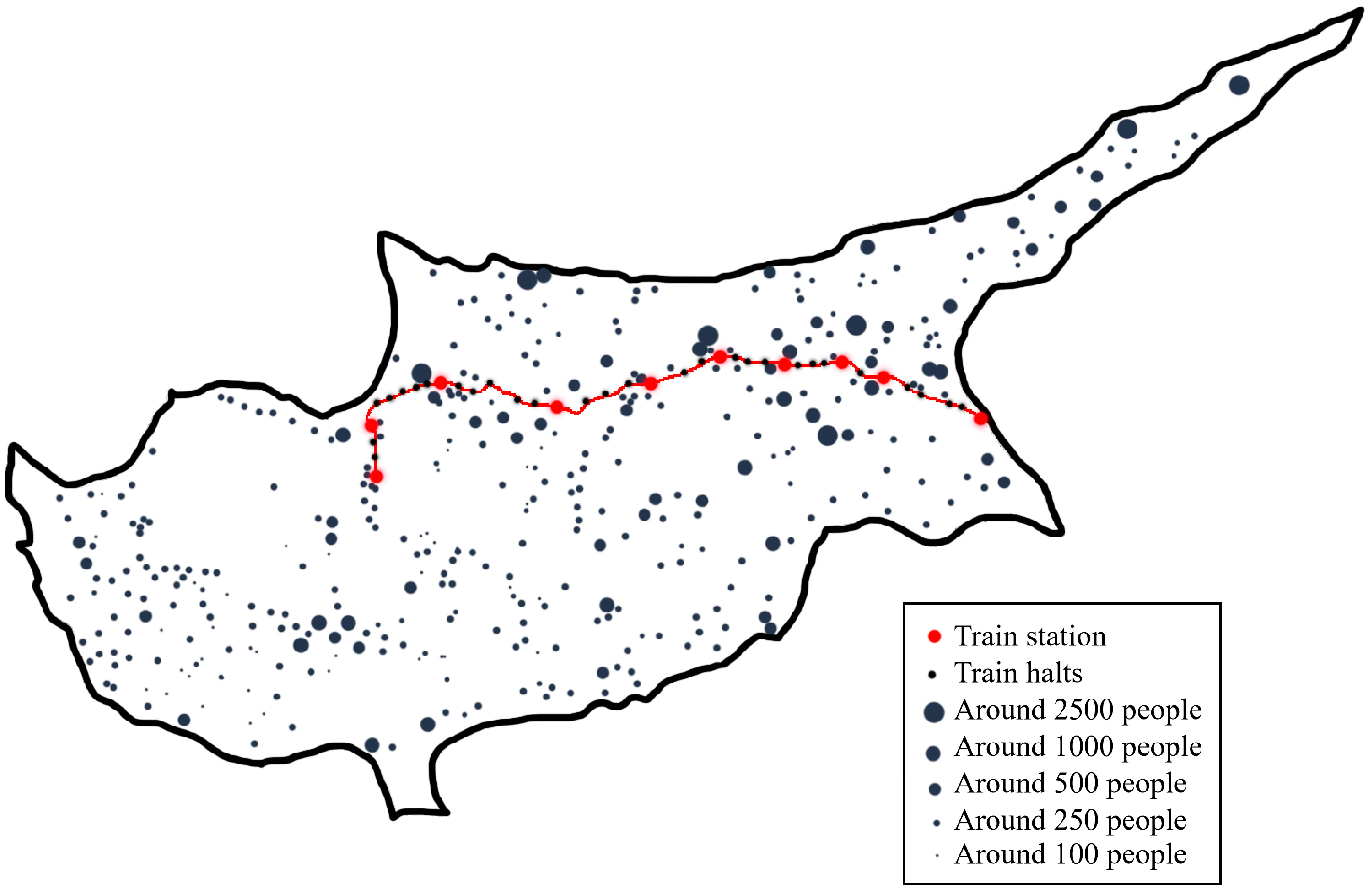

Also, in the case of Cyprus, the rail route brought an important addition to the island’s tree population and agriculture, where a considerable number of imported eucalyptus (for the control of wetlands), local acacia, and cypress trees have been planted on the route and the agricultural activities were increased. The economic stability and population numbers of the villagers were closely related to agricultural productivity, as the livelihood of the inhabitants relied significantly on it. The island’s Mesaoria region (central lowlands of the island) had the greatest rate of population growth both before and after the railroads were built. A significant pattern emerges from an overlay of maps displaying changes in rural population from 1901 to 1931 with the railway route: the population growth rates grew more concentrated in the areas close to the railway line [

21]. This suggests a relationship between the development of the railway network and the growth of neighboring population centers.

The new railway stations developed into hubs for the monetized economy, while simultaneously becoming focal points for urban development, centers of commerce and administration, and locations for the establishment of colonial law enforcement agencies and the implementation of colonial policies [

32].

In fact, railway stations had a big impact on how administrative hubs within cities formed and developed during the British colonial era. Around railway stations, the formation of new urban nodes or the growth of preexisting ones was frequently facilitated by the development of railway infrastructure. As hubs of trade and commerce, railway stations aided in the flow of people and goods and prompted the expansion and development of cities. Administrative functions including government offices, municipal buildings, and commercial enterprises tended towards these transport hubs as cities grew around railway stations. Administrative centers are concentrated around railway stations because these areas are easily accessible by rail, which makes them desirable locations for administrative activities. In addition, the existence of railway stations frequently sparked the growth of related facilities and infrastructure, such as hotels, marketplaces, banks, and communication networks, all of which increased the areas appeal for administrative purposes. In brief, railway stations shaped the urban landscape and made it easier for administrative activities to be concentrated around transportation hubs, which in turn had a significant impact on the formation and spatial organization of administrative centers within cities during the British colonial period.

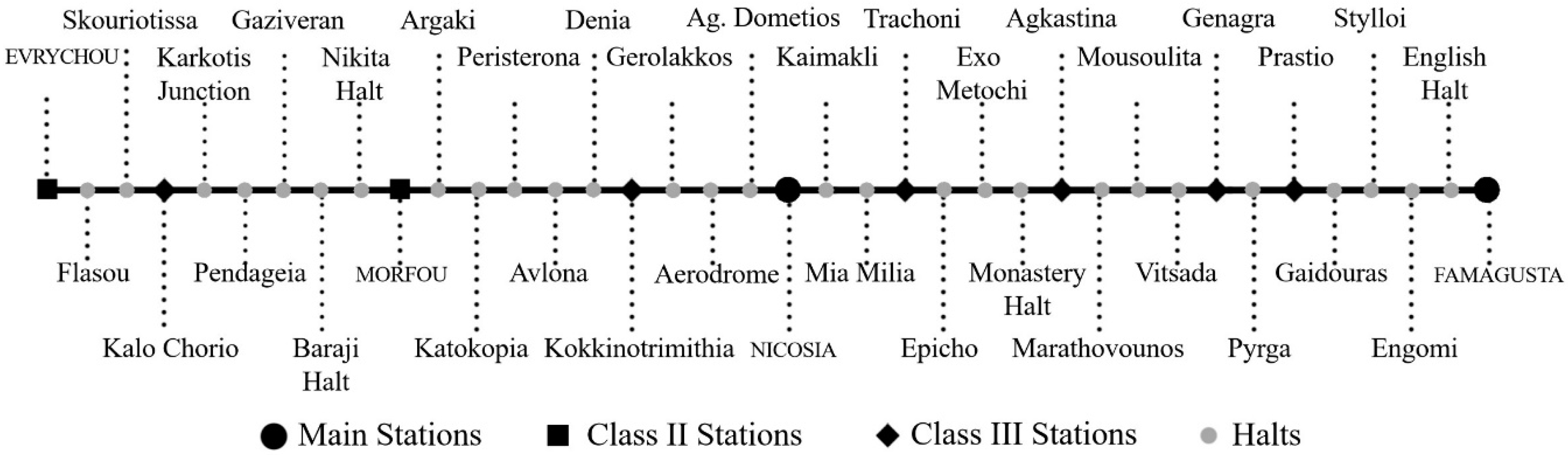

In the scope of this paper, Lord Kitchener’s Survey of Cyprus (1882) was used to illustrate the urban environment before the Cyprus Government Railway (CGR) was established and maps of 1946 used for comparison to illustrate the urban environment towards the end of CGR. Famagusta and Nicosia, as the two major cities with main station buildings, were analyzed to investigate the effect of CGR on the formation of new administrative centers.

Famagusta served as the main hub of the CGR network, and the organization’s headquarters were located there. Its geographically advantageous location resulted in the highest urban development impacted by the railway system. Constructing and running the railway network promoted urbanization and economic expansion in addition to improving Famagusta’s connectivity with neighboring areas and capital. The CGR headquarters’ location in Famagusta made it more straightforward for several commercial and administrative corporations to begin setting up and creating an administrative hub.

A comprehensive analysis of the figure-ground maps shown in

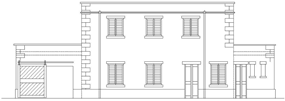

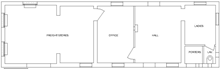

Figure 6 demonstrates significant changes in the Famagusta region’s urban landscape. King George V Avenue, which had only begun to emerge as a boulevard between the ancient Walled City (mainly inhabited by the Turkish Cypriots) and its port and the newly emerging tourism town of Varosha (mainly inhabited by Greek Cypriots), was quickly emerging as the primary hub for British administration in Famagusta, implementing colonial architecture (away from historic walled city, to not competing with the Lusignan and Venetian monuments), particularly in light of the recently introduced transport possibility. Along this avenue, a forest area designed to serve as a public park was built in addition to the numerous structures. The goal of this project was to raise the standard of the urban environment overall and to improve the city’s green areas through this link. This area is depicted on the 1882 map as having a low building density, which is consistent with its relatively peripheral position within the Famagusta urban fabric at that time. On the other hand, a notable change is seen in the 1946 map, where a noticeable rise in construction density is noted. This change is timed to correspond with the arrival of the railway infrastructure, which acted as a catalyst for local urban development. It becomes clear that this area developed into a significant city administration hub throughout time. New administrative and other public buildings have been constructed in this area including the railway station building, supportive buildings of CGR, office of PWD, hospital building, Ottoman bank building, police station, English church, offices of department of agriculture and other governmental offices forming a centralized administrative hub facilitated by the accessibility and connectivity afforded by the railway network. In addition to railway structures, Famagusta District Administration Offices and Law Courts building were constructed in 1908, shortly after the establishment of the railways. The building was constructed using exposed stone material in a linear configuration parallel to the boulevard. Its front façade is characterized by arcades and is divided into three distinct sections.

Unfortunately, due to the building’s condition, it cannot be used, having a destroyed roof. Considering the building’s situation there is a serious risk that the structure may collapse if reinforcing is not done quickly. The Central Police Station of Famagusta was another structure built on the same street, across from the Courts and the Railway Station. The building’s importance was emphasized by its arcade veranda, which formed an entrance hallway and was raised on a platform that was reachable by stairs. The building is not used as a police station but instead converted into a series of little commercial facilities. The Famagusta Post Office and the Famagusta District Commissioner’s Residence are further noteworthy structures built near the railway site. The Commissioner’s Residence is next to the boulevard, but a wooded area divides it from it. The post office is one of the rare examples that the function of the building kept the same through time and is still in use.

There are significant rises and drops in the effectiveness of Famagusta and its harbor throughout history. Famagusta was still a relatively small town when it was first captured by the Lusignan family towards the end of the 12th century. The port area was naturally suitable for ships to deck, but the interest in use was limited in the beginning. With the Lusignan control, the harbor and the city gain more importance with the increasing trade. The use of Famagusta harbor due to its strategic location and natural deep water brought great wealth to the city. For example, the crowning of Peter I, as the nominal King of Jerusalem, took place in Saint Nicholas Cathedral in Famagusta [

33], showing the prestige of the city at the time. After 1373, the Genoese, who took an area of 3 km around Famagusta under their control, severed the relations between the city and the port with the rest of the island; the commercial activities in the port largely decreased, and the city’s economy declined [

34]. Famagusta once more rose to the status of one of the island’s most significant cities after the Venetians seized control of it in 1489 from the Lusignan Kingdom, and the harbor became busier and richer [

35]. Famagusta’s port activities decreased during the Ottoman era because of the administration’s preference for Larnaca as the primary port and limiting the access of Christians to the Famagusta Walled City [

36].

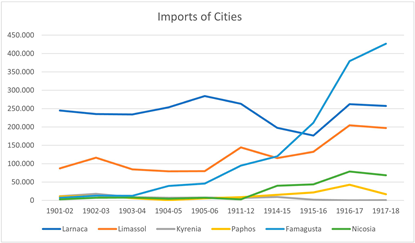

In the early times of British control, Larnaca and Limassol were the main port cities with the most import and export rates compared to others. The growth of Famagusta for military purposes led to the construction of the railway connection to the city. This fact linked the destiny of CGR and the port of Famagusta. Apart from military use, this collaboration between the port and railway affected the economy of the city.

Figure 7 represents the historical development of the harbor of Famagusta in the early 20th century.

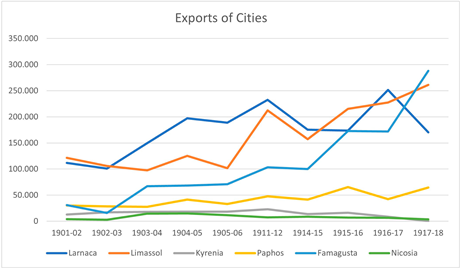

Table 4 shows that there was a significant increase in Famagusta’s import and export amount after the establishment of the railways. After 1906, there was a gradual rise for Famagusta, becoming the most active harbor on the island with the highest numbers in 1918. This shows a clear correlation with the railway route starting from Famagusta, and the trading facilities. The sharp increase in Famagusta’s trade is also affected by the investments and development projects to the harbor. Especially, the construction between 1902 and 1904 just before the establishment of the railways marked the beginning of a collaboration that will last for years. On the other hand, stability in the import and export rates can be observed for Larnaca and Limassol with some fluctuations.

As the capital city of Cyprus, the other main train station was built in Nicosia. As there are no major natural obstacles, such coastlines or mountain ranges, in Nicosia’s surrounding area, the city has experienced radial expansion in its urban development (see

Figure 8). Nicosia’s strategic location has allowed the city to expand and evolve in multiple directions from its central core, maintaining its old walled city as the main focal point. Similarly to Famagusta, in Nicosia’s built environment there is evidence of the establishment of a developing administrative center, especially in the northern side of the walled city where the railway station was located. Nicosia developed an urban center that served mainly transportation and customs-related purposes, unlike Famagusta. Nicosia premises included buildings with transportation and customs-related functions such as PWD warehouses, custom offices, good sheds, custom warehouses, and other buildings supporting the railway transportation. The proximity of this infrastructure highlights the coordinated efforts to facilitate and control trade, influencing the way the urban landscape is arranged spatially and how its functions are focused.

Considering that being the first section of the railway’s construction and the availability of maps covering the necessary historical periods, this part of the paper examines the settlements between Styllos and Yenagra. Figure-ground maps (see

Figure 9) were produced and examined through careful analysis in order to identify spatial patterns and transformations within this region. This deliberate decision allows for a thorough investigation of the railway’s early developmental effects on the neighboring communities, providing insight into the changes in land use, infrastructure, and socioeconomic dynamics in this particular area. When comparing the two maps, it is clear that every village studied has experienced significant expansion and development. A closer examination reveals a regular pattern in which the village center serves as the focal point and growth is noticeably directed towards the railway route. The impact of the railway infrastructure on the direction and rate of urban growth in these areas is highlighted by this spatial analysis.

When comparing the maps of Engomi village from 1882 and 1946 (see

Figure 10), one can observe a remarkably similar growth pattern. This common pattern in the development of the villages is partly due to economic reasons. The direction of the urban growth leaned towards the south side which the railway line was passing. The existence of a railway line facilitated improved access to marketplaces, trade routes, and larger cities, thus promoting economic prospects in settlements situated alongside the railway path. This boosted economic activity, encouraged local development and drew in immigration.

The railway was an essential means of movement for both people and products, providing easier access to and from the villages that were located along its path. As the villages closer to the train lines had more accessibility, these settlements were able to flourish as a result of being encouraged to settle and making labor and products more easily moved. Another reason for the growth is that the policies of British colonial authorities frequently encouraged the development of rural areas. In order to encourage villages to develop homes and businesses close to railway stations and transit hubs, subsidies, incentives, and land grants were provided along railway lines.

4. Conclusions

Overall, this study underscored the significance of the CGR, providing insights into its design strategies and their impact on the development of settlements across Cyprus. The CGR was established as a crucial infrastructure to connect key economic and population regions across Cyprus. It efficiently facilitated the transport of agricultural and mining products to Famagusta for export while also providing essential public transit services. Strategically designed to align with existing road networks and densely populated areas, the railway ensured optimal connectivity with minimal construction costs. The route’s development was carefully planned, considering factors such as terrain gradient, agricultural productivity, and population density, to maximize both utility and accessibility. Beyond its primary roles in cargo and passenger transport, the railway also supported postal services and military operations, underscoring its multifaceted significance in the island’s development.

CGR not only revolutionized transportation in Cyprus but also introduced modern architectural and construction techniques. Blending neoclassical and colonial styles, its stations shaped settlement growth and reflected the island’s modernization. Major hubs like Famagusta and Nicosia, along with smaller rural stations, highlighted a practical yet impactful architectural legacy.

In the context of Cyprus, the CGR exemplifies the transformative role of railways in shaping urban landscapes, economic stability, and population patterns. Villages along the railway route, particularly in the Mesaoria region, experienced increased agricultural productivity and population growth, while urban nodes like Famagusta and Nicosia evolved into administrative and economic hubs due to enhanced connectivity and resource accessibility. In Famagusta, the CGR facilitated the emergence of a centralized administrative district, integrating colonial administrative buildings, commercial establishments, and urban infrastructure, thus driving urban expansion. Similarly, Nicosia’s radial urban growth incorporated transportation and customs-related facilities near its railway station, reflecting the railway’s role in structuring urban functions. Both cities demonstrated how railway infrastructure attracted investment, commerce, and population migration, thereby transforming their urban fabrics. The spatial analysis of villages such as Engomi reveals a clear pattern of growth oriented toward the railway line, driven by economic opportunities and accessibility. British colonial policies further encouraged this trend through subsidies and incentives, fostering settlements near railway hubs. The comparative analysis of historical maps underscores the profound impact of railway infrastructure on land use, urban planning, and socioeconomic dynamics across different scales.

Overall, the CGR not only reshaped the physical landscapes of Cyprus but also influenced its socioeconomic trajectories, establishing railways as a pivotal force in urban and regional development during the British colonial era. These findings underscore the broader implications of railway systems in fostering economic integration, urbanization, and administrative centralization in colonial and postcolonial contexts.

To deepen our understanding of the CGR, it is recommended to expand historical and archival research by utilizing a broader range of sources, including official records, company documents, periodicals, and oral histories. Archaeological surveys and excavations at old CGR sites could uncover physical evidence of its infrastructure, materials, and usage, offering new research opportunities. Heritage assessments should evaluate the condition and significance of CGR sites, with preservation plans addressing threats like urbanization and vandalism, while adapting structures for sustainable reuse. Engaging local communities to collect oral histories would provide valuable insights into the railway’s social and cultural impacts. Digital mapping and geospatial analysis could create detailed visualizations of routes and changes in land use, while interdisciplinary collaboration among historians, archaeologists, architects, and planners would enrich the study. Lastly, educational initiatives and awareness campaigns should promote the appreciation of the CGR’s cultural heritage among diverse audiences.