A Study on the Diversity and Cultural Characteristics of Decorative Patterns of Traditional Academies in Eastern China Based on Diversity Index and Social Network Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of the Study Area

2.2. Research Object

2.3. Overview of Research Sample Classification

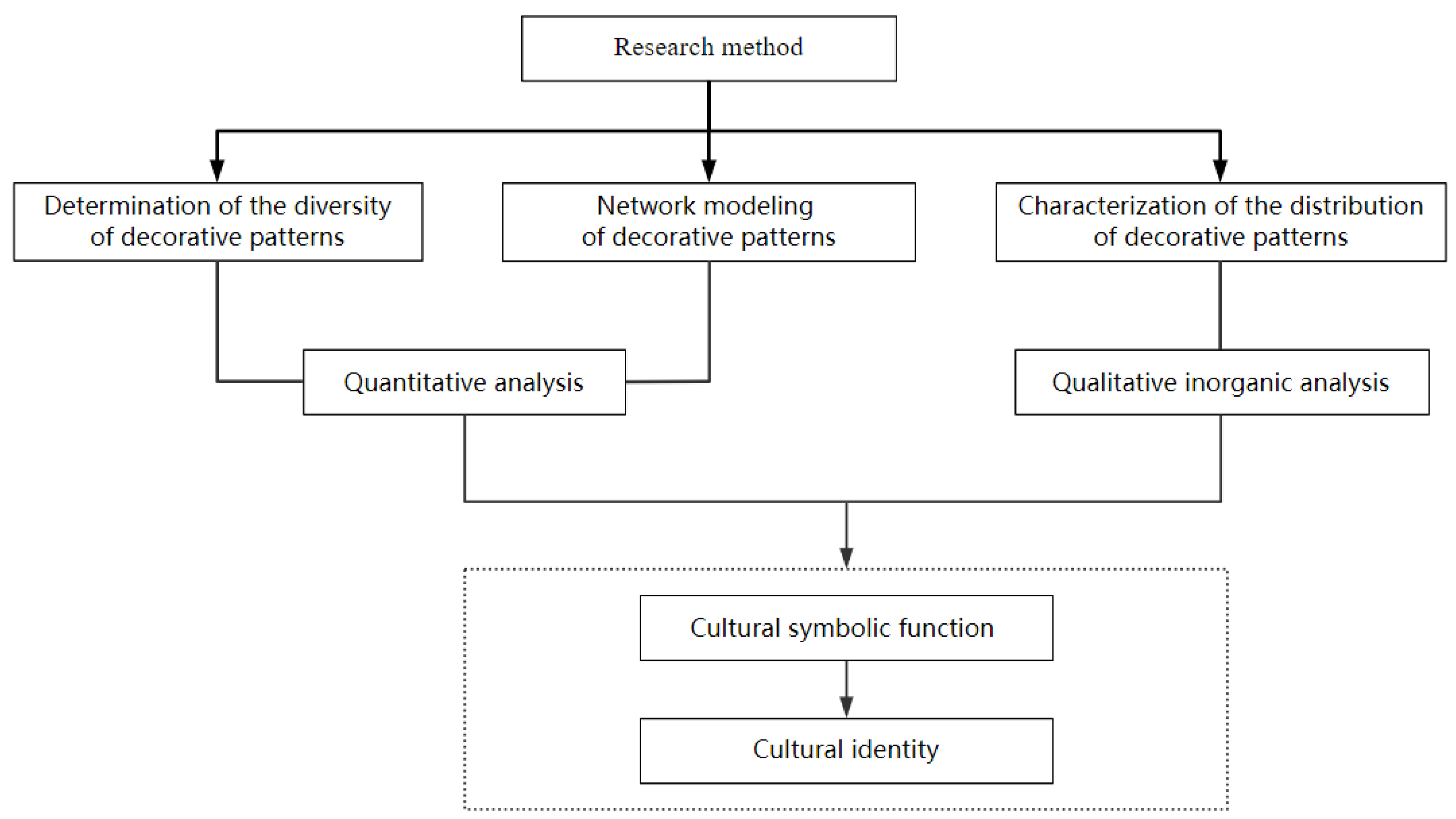

2.4. Research Methods

2.4.1. Workflow

2.4.2. Determination of the Diversity of Decorative Patterns

2.4.3. Characterization of the Distribution of Decorative Patterns

2.4.4. Network Modeling of Decorative Patterns

3. Results

3.1. Diversity of Decorative Patterns of Traditional Academy Architecture in Eastern China

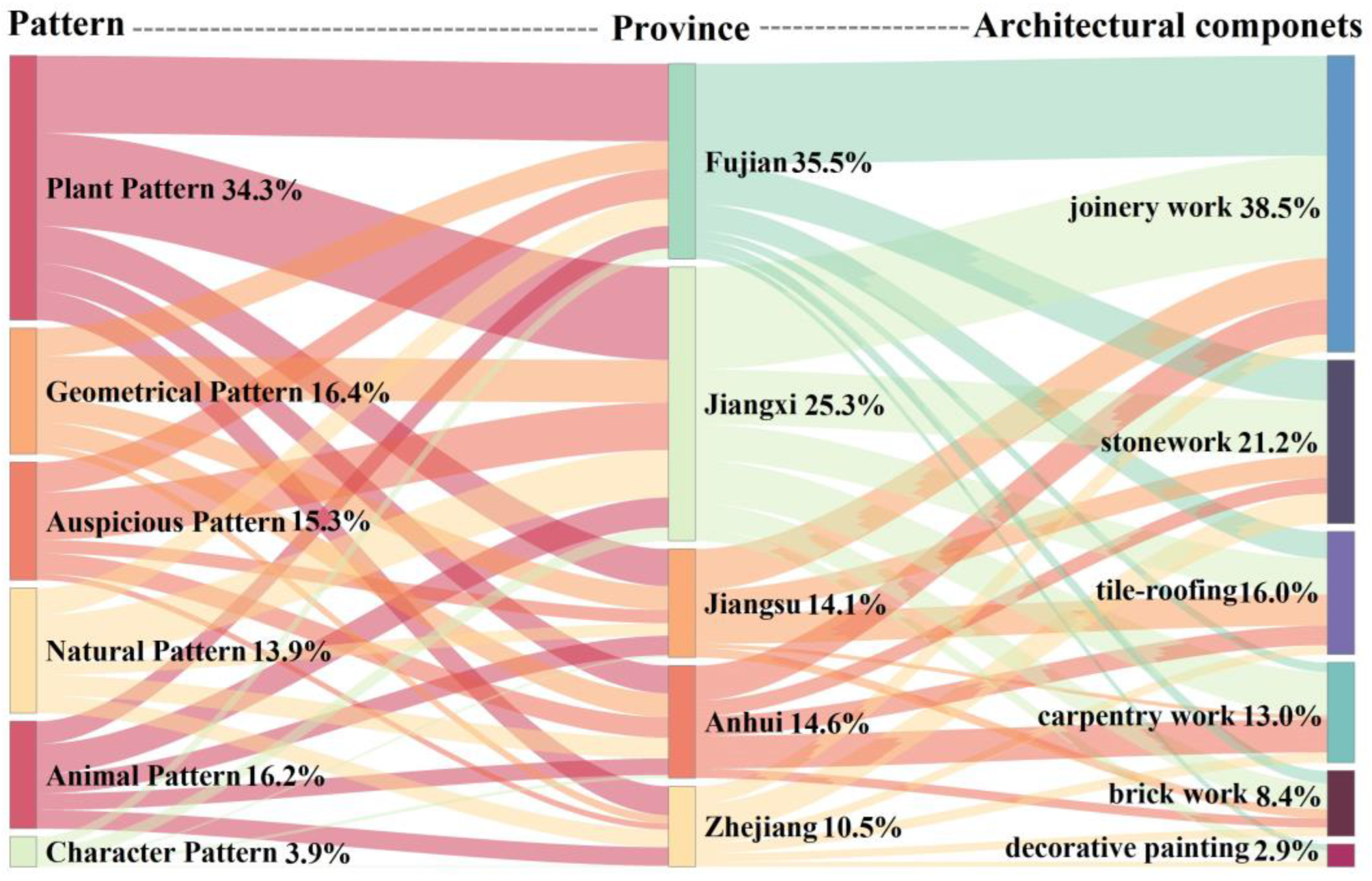

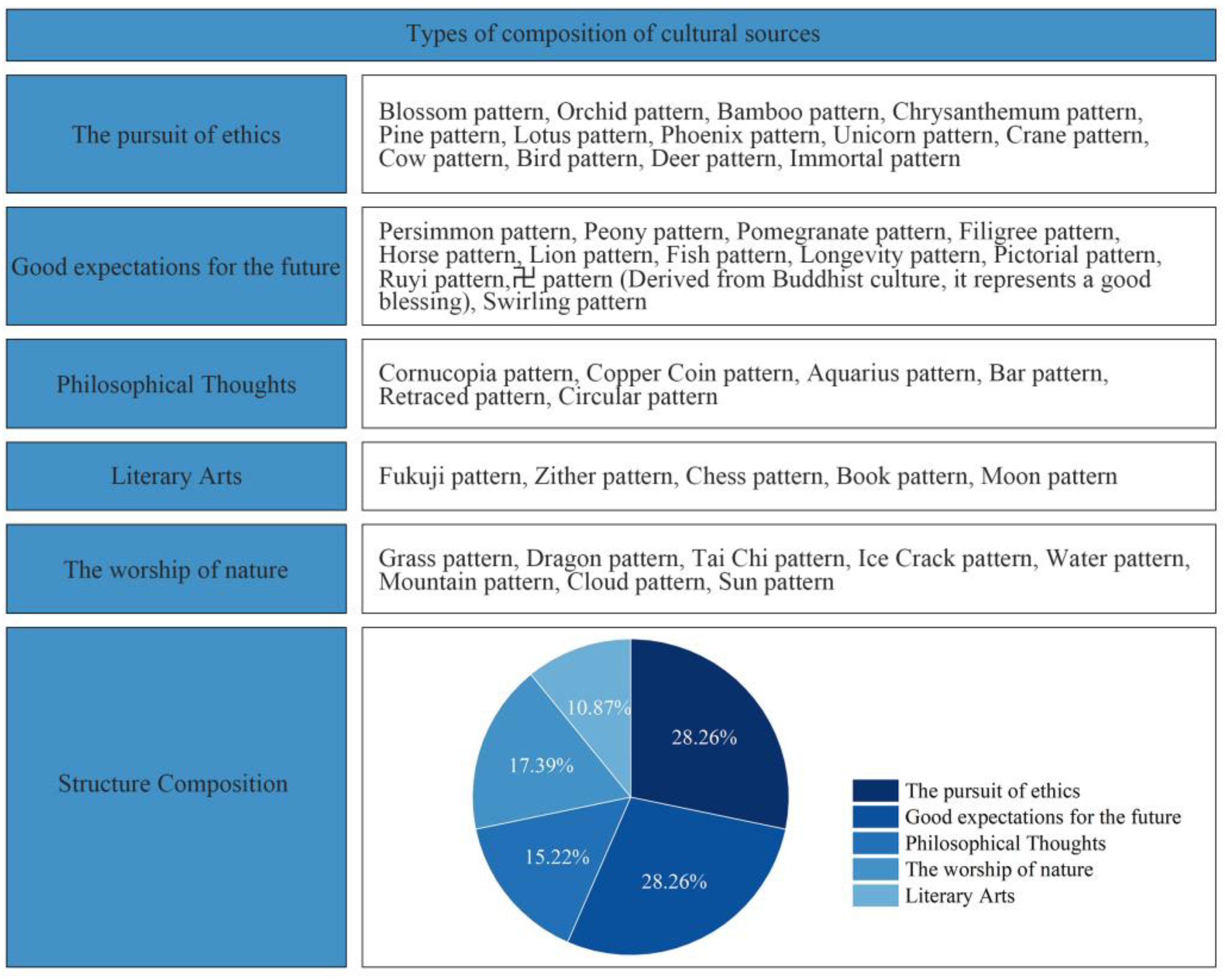

3.1.1. Composition of the Diversity of Decorative Patterns of Traditional Academy Architecture in Eastern China

3.1.2. The Diversity Index of Decorative Patterns of Traditional Academy Architecture in Eastern China

3.2. Distributional Characteristics of Decorative Patterns of Traditional Academy Architecture in Eastern China

3.3. Spatial Network Characteristics of Decorative Patterns in Traditional Academy Architecture in Eastern China

3.3.1. Network Density

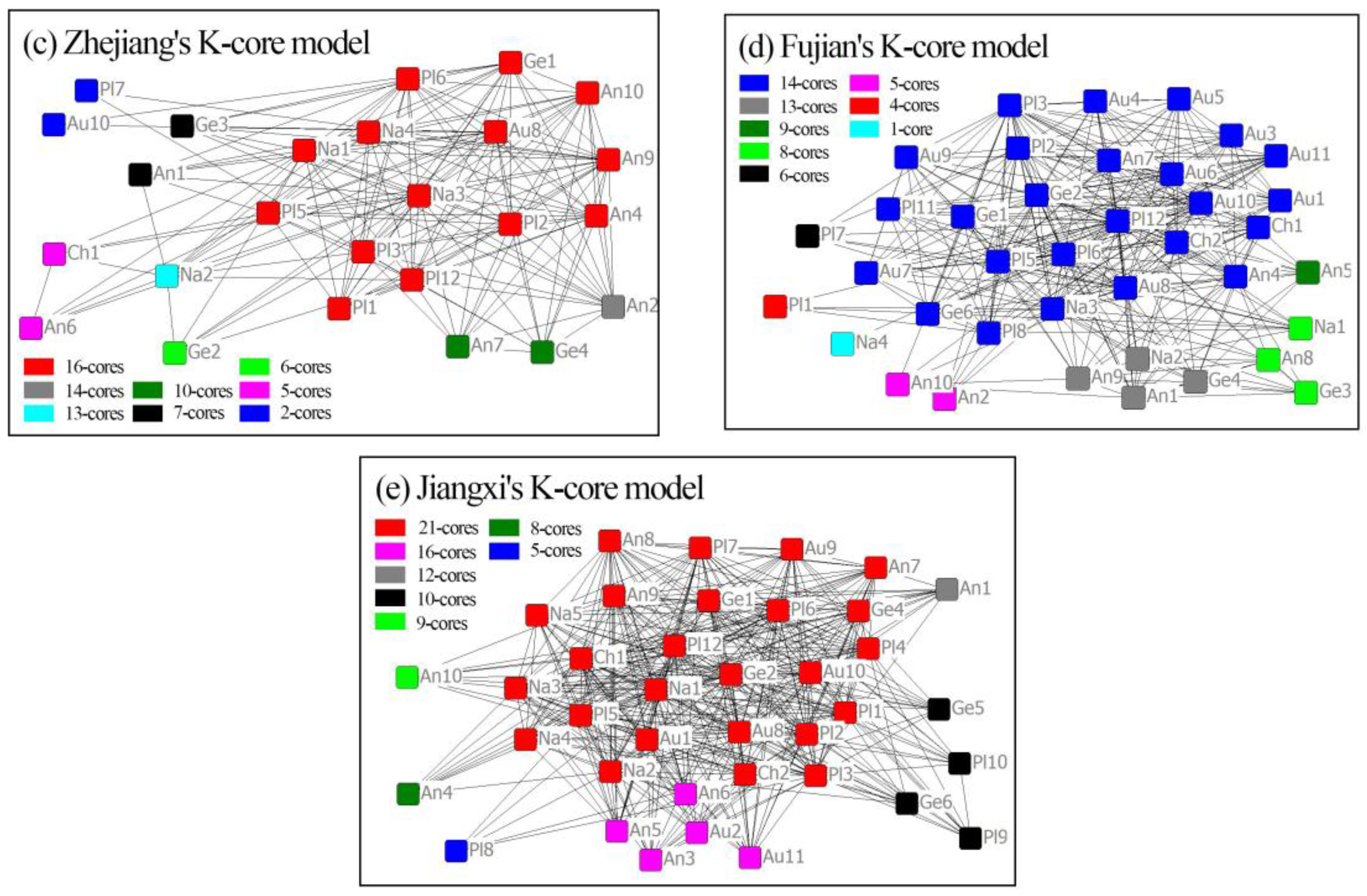

3.3.2. K-Core

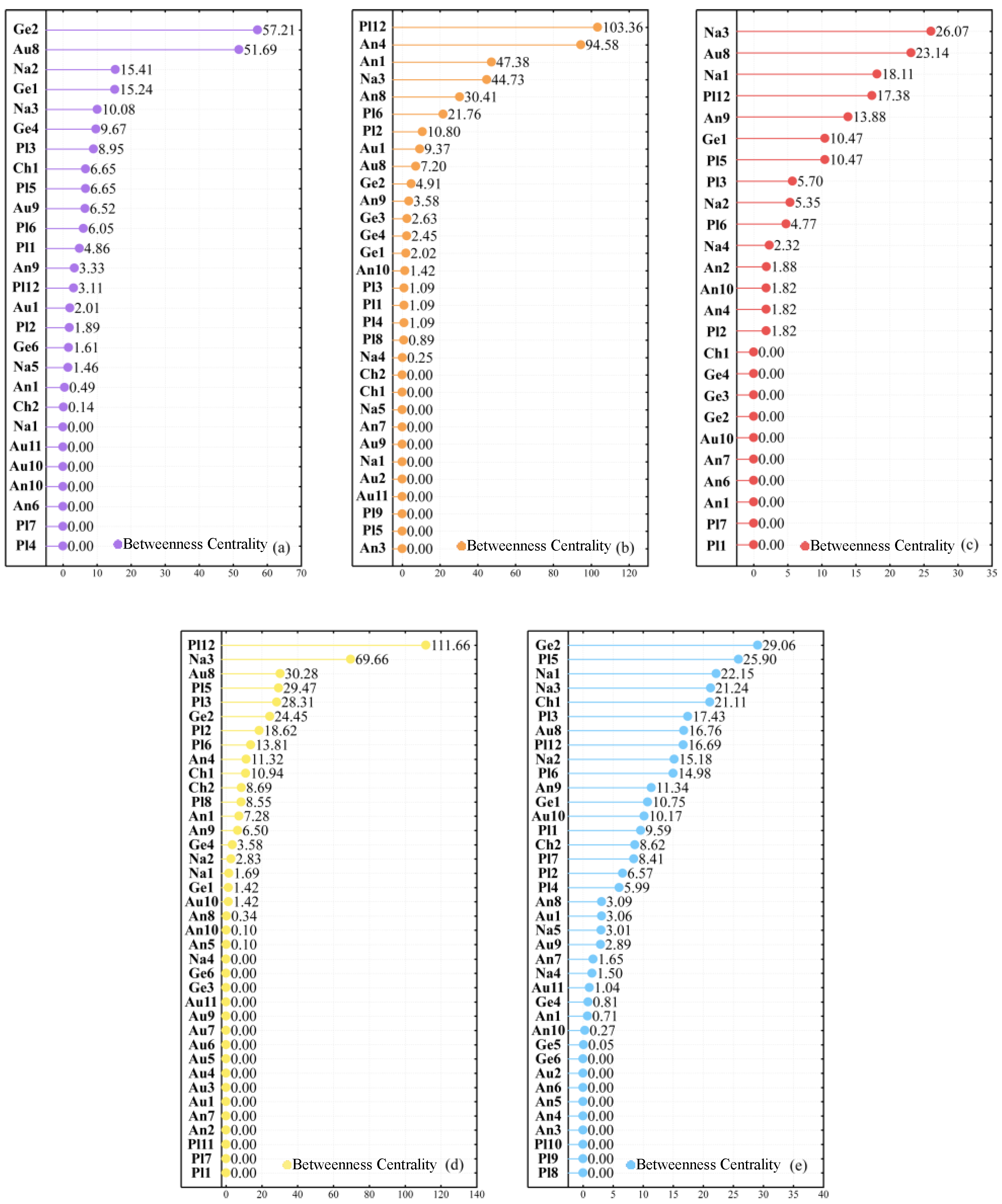

3.3.3. Intermediate Centrality

4. Discussion

4.1. Cultural Symbolic Function of Decorative Patterns

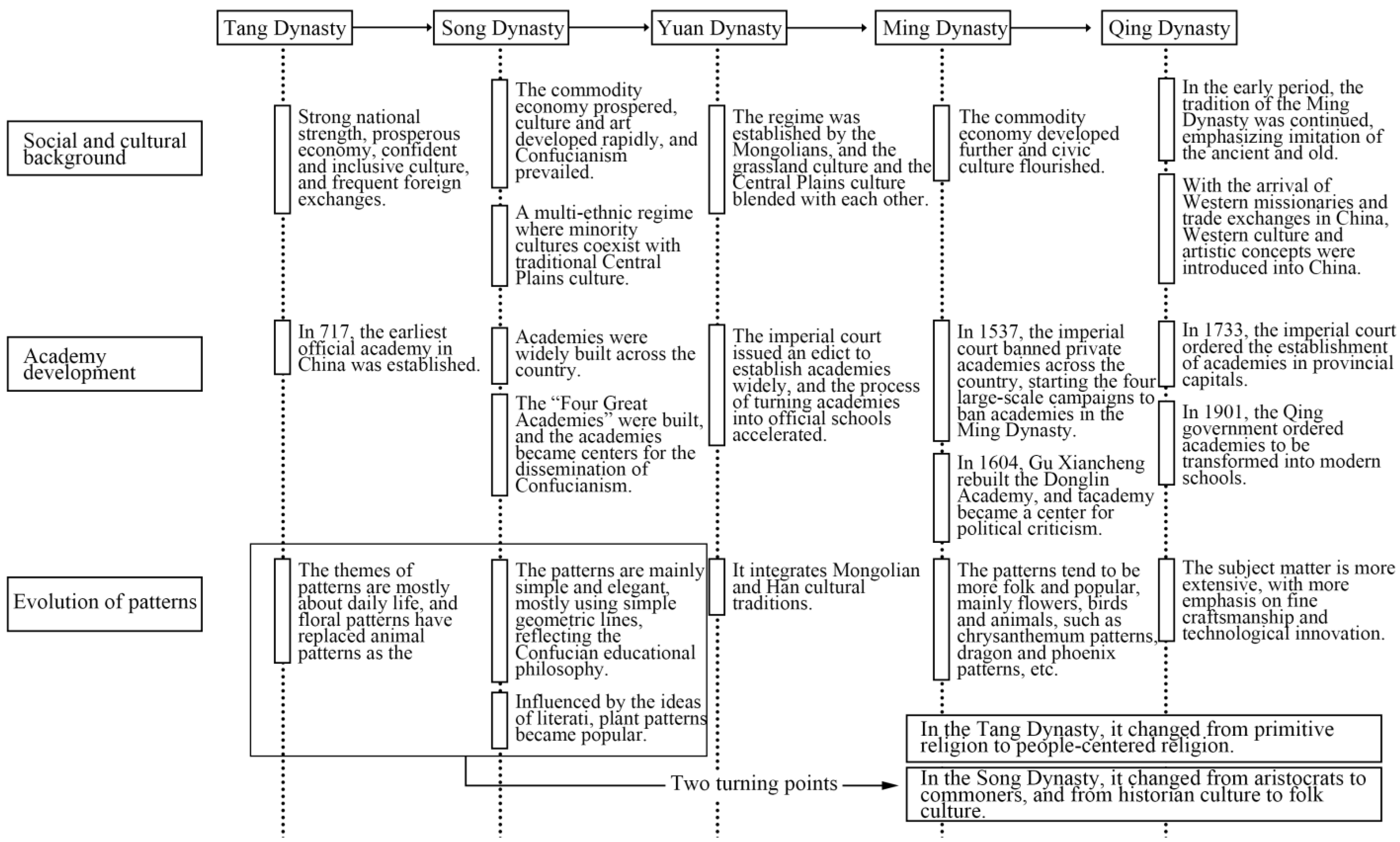

4.2. Historical Dynamics and Cultural Continuity of Patterns

4.3. Multicultural Integration of Decorative Patterns in Traditional Academy Architecture in Eastern China

4.3.1. The Dominant Role of Confucian Culture in Multicultural Integration

4.3.2. Selective Integration of Buddhist Culture in Multiculturalism

4.3.3. Identity of Regional Culture in Multiculturalism

4.4. Research Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kammeier, H.D. Managing cultural and natural heritage resources: Part I–from concepts to practice. City Time 2008, 4, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Grimwade, G.; Carter, R.W. Managing small heritage sites with interpretation and community involvement. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2000, 6, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Wang, Y. Modern Value of Chinese Academies’ Revival. J. China Univ. Geosci. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2016, 16, 136–141+156. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, J.; Huang, Y. The Academy System of Modern Universities Promoting the Cultivation of Top-notch Innovative Talents: Logic, Dilemma and Paths. High. Educ. Dev. Eval. 2025, 41, 53–63+131. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Tian, G.; Wei, K.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, S.; Huang, Y.; Yao, X. The influence of environment on the distribution characteristics of historical buildings in the Songshan Region. Land 2022, 11, 2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, L. Optimization of Heritage Management Mechanisms through the Prism of Historic Urban Landscape: A Case Study of the Xidi and Hongcun World Heritage Sites. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Li, H.; Li, J.; Lu, Y.; Gao, C.; Yang, D. Human–Land Coupling Relationship in Lushan National Park and Its Surrounding Areas: From an Integrated Ecological and Social Perspective. Land 2024, 13, 1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Zakaria, S.A. The Spatial Form of the Traditional Residences of Shanxi Merchants: A Case Study of Pingyao Ancient City, China. Buildings 2024, 14, 3266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billore, S. Cultural Consumption and Citizen Engagement—Strategies for Built Heritage Conservation and Sustainable Development. A Case Study of Indore City, India. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, L. Confucian Academies and the Materialisation of Cultural Heritage. In The Heritage Turn in China; Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 69–88. [Google Scholar]

- de Noronha Vaz, E.; Cabral, P.; Caetano, M.; Nijkamp, P.; Painho, M. Urban heritage endangerment at the interface of future cities and past heritage: A spatial vulnerability assessment. Habitat Int. 2012, 36, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Tang, Y. Towards the Contemporary Conservation of Cultural Heritages: An Overview of Their Conservation History. Heritage 2024, 7, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Huang, W.; Xu, Q. Constructing a Semantic System of Facade Elements for Religious Architecture from a Regional Perspective: A Case Study of Jingzhou. Buildings 2024, 14, 3147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Aoki, N. The study on the social value of the architectural heritage preservation. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Remote Sensing, Environment and Transportation Engineering, Nanjing, China, 24–26 June 2011; pp. 2766–2769. [Google Scholar]

- Wiktor-Mach, D. What role for culture in the age of sustainable development? UNESCO’s advocacy in the 2030 Agenda negotiations. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2020, 26, 312–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xu, H. Research on the Inheritance and Development of Huizhou Culture in the Construction of New Countryside in Anhui Province: Taking “Culture Wall” as an Example. Sci. Soc. Res. 2021, 3, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Guo, Q.; Yuan, J.; Li, H.; Fu, B. Research on the Conservation Methods of Qu Street’s Living Heritage from the Perspective of Life Continuity. Buildings 2023, 13, 1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, Q.; Hu, S. Intangible cultural heritage in the Yellow River basin: Its spatial–temporal distribution characteristics and differentiation causes. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, H.; Chalana, M.; Zhou, J. Diverse approaches to the preservation of built vernacular heritage: Case study of post-disaster reconstruction of the Xijie Historic District in Dujiangyan City, China. J. Archit. Conserv. 2020, 26, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; Li, Q.; Zhang, J. Rethinking Industrial Heritage Tourism Resources in the EU: A Spatial Perspective. Land 2023, 12, 1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shishmanova, M.V. Cultural tourism in cultural corridors, itineraries, areas and cores networked. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 188, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Li, S.; Chan, C.-S. Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP)-based assessment of the value of non-World Heritage Tulou: A case study of Pinghe County, Fujian Province. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 26, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Qi, G.; Guo, Y.; Wang, D. Analysis of Decorative Paintings in the Dragon and Tiger Hall of Yuzhen Palace: Culture, Materials, and Technology. Coatings 2024, 14, 1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Mustafa, M.B. A Study of Ornamental Craftsmanship in Doors and Windows of Hui-Style Architecture: The Huizhou Three Carvings (Brick, Stone, and Wood Carvings). Buildings 2023, 13, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Li, L.; Gao, Y.; Liu, N.; Cheng, L. Expressing the Spatial Concepts of Interior Spaces in Residential Buildings of Huizhou, China: Narrative Methods of Wood-Carving Imagery. Buildings 2024, 14, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, G.; Liao, N.; Yuan, C.; Wei, L.; Feng, Y. A Study on the Color Prediction of Ancient Chinese Architecture Paintings Based on a Digital Color Camera and the Color Design System. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Fu, P.; Cao, M.; Dong, W. Conservation of Yuan Dynasty Caisson Paintings in the Puzhao Temple, Hancheng, Shaanxi Province, China. Coatings 2024, 14, 1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heng, X.; Qi, Q.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, A. Research on Digital Preservation and Inheritance Strategies for Traditional Architectural Decorations: A Case Study of the Chiwen. Furnit. Inter. Des. 2024, 31, 118–123. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Kong, C.; Weng, P. Research on Architectural Characteristics and Protection Strategies of Traditional Villages in Nanxi River Basin——Xikou Village in Yongjia County as an Example. Furnit. Inter. Des. 2024, 31, 134–139. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Dai, Z. A Study on the Diversity and Integration Characteristics of Ethnic Cultural Genealogy of Traditional Villages in Miaojiang Corridor. J. Hubei Minzu Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci.) 2023, 41, 136–146. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Liu, W.; Gong, L.; Huang, Z. Analysis on Spatial Gene Diversity of Traditional Villages of Dong in Southeast Guizhou Province. Guizhou Ethn. Stud. 2020, 41, 99–104. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgatti, S.P.; Mehra, A.; Brass, D.J.; Labianca, G. Network analysis in the social sciences. Science 2009, 323, 892–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. Relationships, Networks and Neighborhoods: Review on Urban Community Social Network Analysis and Its Prospects. City Plan. Rev. 2014, 2, 91–96. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Mu, L.; Yin, S. Research on New-type Urbanization Development Level of Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Based on Social Network Analysis. Mod. Urban Res. 2019, 6, 95–101. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.; Abuduwayiti, A.; Gou, Z. The role of subway network in urban spatial structure optimization–Wuhan city as an example. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2023, 131, 104842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Zhu, Y.; Chu, X.; Yang, X. Research on the Vitality of Public Spaces in Tourist Villages through Social Network Analysis: A Case Study of Mochou Village in Hubei, China. Land 2024, 13, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Chen, J.; Yang, X.; Zhu, Y. Research on Adaptive Reuse Strategy of Industrial Heritage Based on the Method of Social Network. Land 2024, 13, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Gong, Y. α Diversity of Desert Shrub Communities and Its Relationship with Climatic Factors in Xinjiang. Forests 2023, 14, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Xiao, Z.; Shen, S.; Zeng, J.; Deng, C. Characteristics and Species Diversity of Semi-Natural Plant Communities on Langqi Island. Biology 2024, 13, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y. The Illustration of Traditional Patterns in China; Dongfang Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2010; p. 118. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Guo, L.; Ding, T.; Zhuge, K. (Eds.) Pattern Dictionary of China; Tianjin Publishing House: Tianjing, China, 1998; pp. 116–153. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Pan, G.; He, J. An Interpretation of Building French Style; Southeast University Press: Nanjing, China, 2005; pp. 69–85. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yunhe, L. Chinese Artist: Analysis of Design Principles of China Classical Architecture; Tianjin University Press: Tianjin, China, 2005; pp. 95–102. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, C.E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morabito, A.; Musarella, C.M.; Spampinato, G. Diversity and Ecological Assessment of Grasslands Habitat Types: A Case Study in the Calabria Region (Southern Italy). Land 2024, 13, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Q.; He, J.; Liu, D. Identifying restructuring types of rural settlement using social network analysis: A case study of Ezhou City in Hubei Province of China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2021, 31, 1011–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Meter, K.M. The development of social network analysis in the French-speaking world. Soc. Netw. 2005, 27, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zakaria, S.A. Morphological Characteristics and Sustainable Adaptive Reuse Strategies of Regional Cultural Architecture: A Case Study of Fenghuang Ancient Town, Xiangxi, China. Buildings 2025, 15, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, T. Decorative Patterns of Folk Crafts in Ancient West Fujian. J. Longyan Univ. 2012, 30, 43–45. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Chen, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zheng, L.; Huang, Y. Investigating the Satisfaction of Residents in the Historic Center of Macau and the Characteristics of the Townscape: A Decision Tree Approach to Machine Learning. Buildings 2024, 14, 2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yang, C.; Su, Y.; Qiang, M.; Zhou, X.; Yuan, Z. A Study on the Atlas and Influencing Factors of Architectural Color Paintings in Tibetan Timber Dwellings in Yunnan. Buildings 2024, 14, 3971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Chen, J.; Ban, L.; Li, P.; Wang, H. Pre-Planning and Post-Evaluation Approaches to Sustainable Vernacular Architectural Practice: A Research-by-Design Study to Building Renovation in Shangri-La’s Shanpian House, China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Mustafa, M.; Mohd Isa, M.H. Regional Architecture Building Identity: The Mediating Role of Authentic Pride. Buildings 2024, 14, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Chen, J.; Lei, Y. A Study on the Visual Perception of Cultural Value Characteristics of Traditional Southern Fujian Architecture Based on Eye Tracking. Buildings 2024, 14, 3529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, J. The Cultural Values Model: An integrated approach to values in landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2008, 84, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, C.; Hu, C. Kiln–House Isomorphism and Cultural Isomerism in the Pavilions of the Yuci Area: The Xiang-Ming Pavilion as an Example. Buildings 2024, 14, 3188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, Q.; Cao, Y. Spatio-Temporal Distribution Characteristics of Buddhist Temples and Pagodas in the Liaoning Region, China. Buildings 2024, 14, 2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yi, H. Above Form: On the Value form of Planning Heritage—Based on the Dialectical Perspective of “Tangible-Intangible”. City Plan 2023, 47, 38–46+65. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Fan, J.; Fan, H. A Study on Cultural Value and Practical Significance of Ancient Academy in Shaanxi. J. Xi’an Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2025, 28, 82–87. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Altomonte, S.; Allen, J.; Bluyssen, P.M.; Brager, G.; Heschong, L.; Loder, A.; Schiavon, S.; Veitch, J.A.; Wang, L.; Wargocki, P. Ten questions concerning well-being in the built environment. Build. Environ. 2020, 180, 106949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altan, H.; Gürdallı, H. Conceptual Approaches in Contemporary Hotel Interiors in Northern Cyprus: Ornamentation and Representation. Buildings 2024, 14, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Yang, T. Landed and Rooted: A Comparative Study of Traditional Hakka Dwellings (Tulous and Weilong Houses) Based on the Methodology of Space Syntax. Buildings 2023, 13, 2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J. Ritual Worship and Cultural Transmission—The Social Space of Ancient Academy Rituals. Mod. Philos. 2006, 3, 80–86. [Google Scholar]

- Christopher, A. The Timeless Way of Building; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y. Some Questions about Chinese Creation Myth and Primitive Worship. J. Renmin Univ. China 2019, 33, 153–161. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lu, K.; Cao, F. Collective Memory Construction of Rural Traditional Folk Cultures and Its Value inheritance—A Case Study of“Sacrifice in Spring”in the Miao Yuan Village. Zhejiang Acad. J. 2020, 2, 225–231. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Wu, S.; Tian, Q. History of Chinese Patterns; Higher Education Press (PRC): Beijing, China, 2003. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Warren, P. Later Chinese glass 1650–1900. J. Glass Stud. 1977, 19, 84–126. [Google Scholar]

- Khaznadar, B.M.A.; Baper, S.Y. Sustainable Continuity of Cultural Heritage: An Approach for Studying Architectural Identity Using Typo-Morphology Analysis and Perception Survey. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J. Confucian Culture and the Ancient Chinese Academies. Confucius Stud. 2009, 3, 121–124. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Rong, W.; Bahauddin, A. Heritage and Rehabilitation Strategies for Confucian Courtyard Architecture: A Case Study in Liaocheng, China. Buildings 2023, 13, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cen, K.; Rao, X.; Mao, Z.; Zheng, X.; Dong, D. A Comparative Study on the Spatial Layout of Hui-Style and Wu-Style Traditional Dwellings and Their Culture Based on Space Syntax. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, T.; Zhang, T. Bidirectional Transmission Mapping of Architectural Styles of Tibetan Buddhist Temples in China from the 7th to the 18th Century. Religions 2024, 15, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.J. Min Culture and its Influence on Fujian Vernacular Architecture. South Archit. 2011, 6, 24–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bornioli, A.; Subiza-Pérez, M. Restorative urban environments for healthy cities: A theoretical model for the study of restorative experiences in urban built settings. Landsc. Res. 2023, 48, 152–163. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name of Academy | Address | Construction Time | Founder |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kaishan Academy | Zhuzi Cultural Park, Youxi County, Sanming City, Fujian Province, China | Built in 1764, the twenty-ninth year of the Qianlong reign of the Qing Dynasty. | Shumu Cai |

| Nanxi Academy | Shui Nan Road, Chengguan Town, Youxi County, Sanming City, Fujian Province, China | Built in the first year of the Song Dynasty (1237). | Xiu Li |

| Liangjiang Academy | Lianjiang Village, Chengmen Town, Cangshan District, Fuzhou City, China | Date of construction is unknown. | uncharted |

| Shijing Academy | West Aotou, Anhai Town, Quanzhou City, Fujian Province, China | Built in 1211, the fourth year of the Jia Ding period of the Song Dynasty. | JiangYou |

| Wuyi Academy | Under Hidden Screen Peak, Wuyi Mountain, Nanping City, Fujian Province, China | Built in the 10th year of Chunxi in Song Dynasty (1183). | Xi Zhu |

| Songzhou Academy | Songzhou Village, Punan Township, Zhangzhou City, Fujian Province, China | Built in 708, the second year of Jinglong, the reign of Emperor Zhongzong of the Tang Dynasty. | Yuanguang Chen |

| Xiadong Academy | Yanhuixiang Street, Zhangzhou City, Fujian Province, China | Built in 1706, the forty-fifth year of the Kangxi reign of the Qing Dynasty. | Ying Yao |

| Zhengyi Academy | Dongjiekou, Gulou District, Fuzhou City, Fujian Province, China | Built in the sixth year of the Tongzhi reign of the Qing Dynasty (1867). | Gui Ying |

| Zhiyong Academy | Hutou Street, Gulou District, Fuzhou City, Fujian Province, China | Built in the twelfth year of the Tongzhi reign of the Qing Dynasty (1873). | Kaitai Wang |

| Dieshan Academy | Yiyang County, Shangrao City, Jiangxi Province, east of the city | Built in 1313, the second year of the Yuan Dynasty. | Shunchen Yu |

| Ehu Academy | Goose Lake Foothills, Goose Lake Town, Leadshan County, Shangrao City, Jiangxi Province, China | Built in the 10th year of Chunyou of the Southern Song Dynasty (1250). | Kang Cai |

| Xinjiang Academy | South Bank of Xinjiang River, Xinzhou District, Shangrao City, Jiangxi Province, China | First built in 1694, the thirty-third year of the Kangxi reign of the Qing Dynasty. | Guozhen Zhang |

| Zhushan Academy | Huangling Scenic Area, Wuyuan County, Shangrao City, Jiangxi Province, China | Date of construction is unknown. | Zhenyong Cao |

| Bailudong Academy | South foot of Wulaofeng, Lushan City, Jiujiang City, Jiangxi Province, China | Built in the ninth year of the Song Dynasty (976). | members of the Jiangzhou gentry |

| Bailuzhou Academy | Yanjiang Road, Jizhou District, Ji’an City, Jiangxi Province, China | First built in the first year of Song Chunyou (1241). | Wanli Jiang |

| Yanshan Academy | Wangjia Lane, Jinxi County, Fuzhou City, Jiangxi Province, China | First built in the second year of Qianlong in the Qing Dynasty (1737). | Tingji Yan |

| Wangsong Academy | Fenghuang Mountain, Xihu District, Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, China | Built in the 11th year of Hongzhi of Ming Dynasty (1498). | uncharted |

| Wufeng Academy | Chenglu Village, Fangyan Town, Jinhua City, Zhejiang Province, China | Date of construction is unknown. | uncharted |

| Chongzheng Academy | Halfway up the eastern foot of Qingliang Mountain, Gulou District, Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China | Built during the Jiajing period of the Ming Dynasty; the exact date is unknown. | Dingxiang Geng |

| Zunjing Academy | No. 152 Gongyuan Street, Qinhuai District, Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China | Date of construction is unknown. | uncharted |

| Donglin Academy | No. 867, Jiefang East Road, Liangxi District, Wuxi City, Jiangsu Province, China | Built in the first year of the Northern Song Dynasty (1111). | Shi Yang |

| Nanhu Academy | Hongcun, Yixian County, Huangshan City, Anhui Province, China | Built at the end of the Ming Dynasty; the exact date is unknown. | uncharted |

| Zhushan Academy | Xiongcun, Shexian County, Huangshan City, Anhui Province | Built in the twentieth to twenty-fourth years (1755–1759) of the Qianlong reign in the Qing Dynasty. | Jingting Cao, Jingchen Cao |

| Category Name | Description | Example Images |

|---|---|---|

| Carpentry work | Architectural elements such as beams, square beams, and rafter bars in traditional Chinese wood-frame construction. |  |

| Joinery work | Includes wood material components such as doors, windows, and partition screens. |  |

| Decorative painting | Refers to the application of paint and decorative patterns to wooden surfaces. |  |

| Tile roofing | Roof elements of buildings, such as roof ridges, anastomoses, etc. |  |

| Stonework | Roof elements of a building, such as ridges. |  |

| Brickwork | Refers to the use of bricks in walls and other building elements. |  |

| Pattern Type | Number of Species |

|---|---|

| Plant Pattern | 12 |

| Animal Pattern | 10 |

| Auspicious Pattern | 11 |

| Geometrical Pattern | 6 |

| Natural Pattern | 5 |

| Character Pattern | 2 |

| Pattern Type | Name | Number | Frequency % | Pattern Type | Name | Number | Frequency % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plant Pattern | Blossom pattern | Pl1 | 1.48 | Auspicious Pattern | Longevity pattern | Au1 | 1.93 |

| Orchid pattern | Pl2 | 2.52 | Fukuji pattern | Au2 | 0.30 | ||

| Bamboo pattern | Pl3 | 2.52 | Zither pattern | Au3 | 0.15 | ||

| Chrysanthemum pattern | Pl4 | 0.89 | Chess pattern | Au4 | 0.15 | ||

| Pine pattern | Pl5 | 3.86 | Book pattern | Au5 | 0.15 | ||

| Lotus pattern | Pl6 | 6.97 | Pictorial pattern | Au6 | 0.15 | ||

| Persimmon pattern | Pl7 | 1.19 | Cornucopia pattern | Au7 | 0.45 | ||

| Peony pattern | Pl8 | 0.89 | Ruyi pattern | Au8 | 7.86 | ||

| Pomegranate pattern | Pl9 | 0.30 | Coin pattern | Au9 | 1.48 | ||

| Filigree pattern | Pl10 | 0.15 | Vanguard pattern | Au10 | 2.08 | ||

| Vine pattern | Pl11 | 0.15 | Vase pattern | Au11 | 2.23 | ||

| Grass pattern | Pl12 | 17.06 | Animal Pattern | Dragon pattern | An1 | 2.37 | |

| Geometrical Pattern | Bar pattern | Ge1 | 8.01 | Phoenix pattern | An2 | 0.59 | |

| Retraced pattern | Ge2 | 6.38 | Unicorn pattern | An3 | 0.30 | ||

| Swirling pattern | Ge3 | 0.89 | Crane pattern | An4 | 1.34 | ||

| Circular pattern | Ge4 | 2.23 | Cow pattern | An5 | 0.30 | ||

| Tai Chi pattern | Ge5 | 0.15 | Horse pattern | An6 | 0.59 | ||

| Ice Crack pattern | Ge6 | 0.45 | Bird pattern | An7 | 0.89 | ||

| Natural Pattern | Water pattern | Na1 | 3.12 | Deer pattern | An8 | 0.89 | |

| Mountain pattern | Na2 | 2.67 | Lion pattern | An9 | 5.64 | ||

| Cloud pattern | Na3 | 9.94 | Fish pattern | An10 | 2.52 | ||

| Sun pattern | Na4 | 1.04 | Character Pattern | Fairy pattern | Ch1 | 2.52 | |

| Moon pattern | Na5 | 1.19 | Confucian pattern | Ch2 | 1.78 |

| Province | M | H | J |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anhui (AH) | 5.542 | 2.945 | 0.628 |

| Jiangsu (JS) | 6.016 | 2.956 | 0.635 |

| Zhejiang (JZ) | 5.509 | 2.977 | 0.683 |

| Jiangxi (JX) | 6.452 | 3.153 | 0.565 |

| Fujian (FJ) | 7.509 | 3.023 | 0.577 |

| Pattern Type | Name | Number | Cultural Connotation | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plant Pattern | Blossom pattern | Pl1 | Resilience and self-improvement. | Confucian culture |

| Orchid pattern | Pl2 | A symbol of purity and elegance. | Confucian culture | |

| Bamboo pattern | Pl3 | Symbolizes resilience and tenacity to survive. | Confucian culture | |

| Chrysanthemum pattern | Pl4 | Symbolizes purity, resilience, and tenacity of character. | Confucian culture | |

| Pine pattern | Pl5 | A symbol of resilience and tenacious survival. | Confucian culture | |

| Lotus pattern | Pl6 | Symbolizing the purity and elegance of a gentleman. | Confucian culture | |

| Persimmon pattern | Pl7 | Symbolizes “everything is as it should be” or “everything is as it should be”. | Traditional Folk Culture | |

| Peony pattern | Pl8 | A symbol of prosperity and good fortune. | Traditional Folk Culture | |

| Pomegranate pattern | Pl9 | Symbolizes wealth and harvest. | Traditional Folk Culture | |

| Filigree pattern | Pl10 | Symbolizes continuity of life and abundance of life. | Traditional Folk Culture | |

| Vine pattern | Pl11 | Symbolizes resilience and strength of spirit. | Traditional Folk Culture | |

| Grass pattern | Pl12 | Symbolizes vitality and continuous growth. | Buddhism Culture | |

| Animal Pattern | Dragon pattern | An1 | Symbolizing authority and power, it symbolizes wisdom, flexibility, and change, controlling rain and rivers. | Traditional Folk Culture |

| Phoenix pattern | An2 | The king of all birds it is a symbol of good fortune, nobility, and beauty. | Traditional Folk Culture | |

| Unicorn pattern | An3 | Symbolizing the benevolence and noble qualities of a gentleman. | Confucian culture | |

| Crane pattern | An4 | It symbolizes the noble character of a gentleman. | Confucian culture | |

| Cow pattern | An5 | Symbolizing diligence and steadfastness, it is often used as a metaphor for human qualities and morals. | Traditional Folk Culture | |

| Horse pattern | An6 | Symbolizes speed and strength, success and victory, power and dignity. | Traditional Folk Culture | |

| Bird pattern | An7 | Symbolizes freedom and beauty, good fortune, and celebration. | Traditional Folk Culture | |

| Deer pattern | An8 | It signifies the gentleness, benevolence, and purity of a gentleman. | Confucian culture | |

| Lion pattern | An9 | Symbolizes strength and authority, good fortune, and guardianship. | Confucian culture | |

| Fish pattern | An10 | It is a metaphor for a poor student who is successful in the imperial examination in one day and soars to great heights. | Confucian culture | |

| Auspicious Pattern | Longevity pattern | Au1 | Represents longevity and blessings, good fortune, and health. | Traditional Folk Culture |

| Fukuji pattern | Au2 | Represents happiness and also symbolizes wealth and health. | Traditional Folk Culture | |

| Zither pattern | Au3 | Qin music symbolizes harmony and balance in Chinese culture. | Confucian culture | |

| Chess pattern | Au4 | The Chess character pattern represents the strategy and wisdom of the literati. | Confucian culture | |

| Book pattern | Au5 | Represents knowledge and learning. | Confucian culture | |

| Pictorial pattern | Au6 | Representing beauty and art, it represents the artistic talent of the literati. | Confucian culture | |

| Cornucopia pattern | Au7 | It is regarded as a symbol of fertility and prosperity of the family. | Taoist culture | |

| Ruyi pattern | Au8 | Symbolizing good fortune and completeness, power, and status. | Buddhism Culture | |

| Copper Coin pattern | Au9 | Copper coins are a symbol of wealth and prosperity in traditional Chinese culture. | Traditional Folk Culture | |

| 卍 pattern | Au10 | A symbol of good luck and good fortune in Chinese culture, expressing good luck and good fortune. | Buddhism Culture | |

| Aquarius pattern | Au11 | A symbol of wealth and good fortune. | Buddhism Culture | |

| Geometrical Pattern | Bar pattern | Ge1 | Representing order and rules, it symbolizes social order and moral norms. | Traditional Folk Culture |

| Retraced pattern | Ge2 | Represents cycle and eternity, symbolizing the cycle of time and the eternity of life. | Traditional Folk Culture | |

| Swirling pattern | Ge3 | Represents the rotation and movement of the universe, symbolizing the power of the universe and the vitality of life. | Traditional Folk Culture | |

| Circular pattern | Ge4 | Representing wholeness and completeness, it also symbolizes harmony and balance. | Traditional Folk Culture | |

| Tai Chi pattern | Ge5 | Represents the unity of opposites of yin and yang and symbolizes the balance and mutual transformation of yin and yang. | Taoist culture | |

| Ice Crack pattern | Ge6 | Representing change and impermanence, it also symbolizes the power of nature and the fragility of life. | Traditional Folk Culture | |

| Natural Pattern | Water pattern | Na1 | The water pattern represents flow and change, symbolizing the passage of time and the impermanence of things. | Confucian culture |

| Mountain pattern | Na2 | It represents steadiness and resilience, symbolizing firmness and perseverance. | Confucian culture | |

| Cloud pattern | Na3 | Cloud is a symbol of good fortune and luck in Chinese culture, expressing good fortune and good luck. | Traditional Folk Culture | |

| Sun pattern | Na4 | Representing light and vitality, it symbolizes the power of the sun and the source of life. | Traditional Folk Culture | |

| Moon pattern | Na5 | Representing softness and serenity, it is a symbol of longing and romance in Chinese culture. | Traditional Folk Culture | |

| Character Pattern | Immortal pattern | Ch1 | Symbolizes the pursuit of immortality and the ideal of attaining immortality. | Confucian culture |

| Confucian pattern | Ch2 | Represents learning and cultivation, often closely associated with Confucian culture, symbolizing knowledge and morality. | Confucian culture |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, S.; Qiao, Y.; Huang, W.; Wang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Xie, J. A Study on the Diversity and Cultural Characteristics of Decorative Patterns of Traditional Academies in Eastern China Based on Diversity Index and Social Network Analysis. Buildings 2025, 15, 692. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15050692

Ma S, Qiao Y, Huang W, Wang Z, Xu Y, Xie J. A Study on the Diversity and Cultural Characteristics of Decorative Patterns of Traditional Academies in Eastern China Based on Diversity Index and Social Network Analysis. Buildings. 2025; 15(5):692. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15050692

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Shuxiao, Yue Qiao, Wei Huang, Ziyu Wang, Yan Xu, and Jinyang Xie. 2025. "A Study on the Diversity and Cultural Characteristics of Decorative Patterns of Traditional Academies in Eastern China Based on Diversity Index and Social Network Analysis" Buildings 15, no. 5: 692. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15050692

APA StyleMa, S., Qiao, Y., Huang, W., Wang, Z., Xu, Y., & Xie, J. (2025). A Study on the Diversity and Cultural Characteristics of Decorative Patterns of Traditional Academies in Eastern China Based on Diversity Index and Social Network Analysis. Buildings, 15(5), 692. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15050692