Evaluation Study of Public Interaction Spaces for the Elderly in a Community—Taking the Railway Station Community in Jiaozuo City as an Example

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Area and Method

2.1. Area of Study

2.1.1. Jiaozuo City Center City Community

- (1)

- Research area selection

- (2)

- Typical community selection

2.1.2. Selection of Specific Communities for Research

- (1)

- Scale and scope

- (2)

- Spatial distribution characteristics

2.2. Research Method

- (1)

- Evaluation system construction stage

- (2)

- Index quantification stage

- (3)

- Observation stage of elderly group behavior

2.3. Establishing Evaluation Index

2.3.1. Selection of Subjective Indicators

- (1)

- Establish evaluation index database

- (2)

- Index screening and correction

2.3.2. Selection of Objective Indicators

- (1)

- Establishment of evaluation index database

- (2)

- Index screening and correction

2.4. Data Sources and Index Quantification

2.4.1. Data Sources

2.4.2. Index Quantification

3. Results

3.1. The Characteristics of the Interaction Behavior of Older Adults in the Railway Station Community

3.1.1. The Time Characteristics of the Interaction Behavior of the Elderly Group

3.1.2. The Spatial Distribution Characteristics of Interaction Behavior of the Elderly Group

3.2. Analysis of Evaluation Results of Public Interaction Spaces in Railway Station

3.2.1. Analysis of Evaluation Results of Subjective Indicators

3.2.2. Analysis of Objective Index Evaluation Results

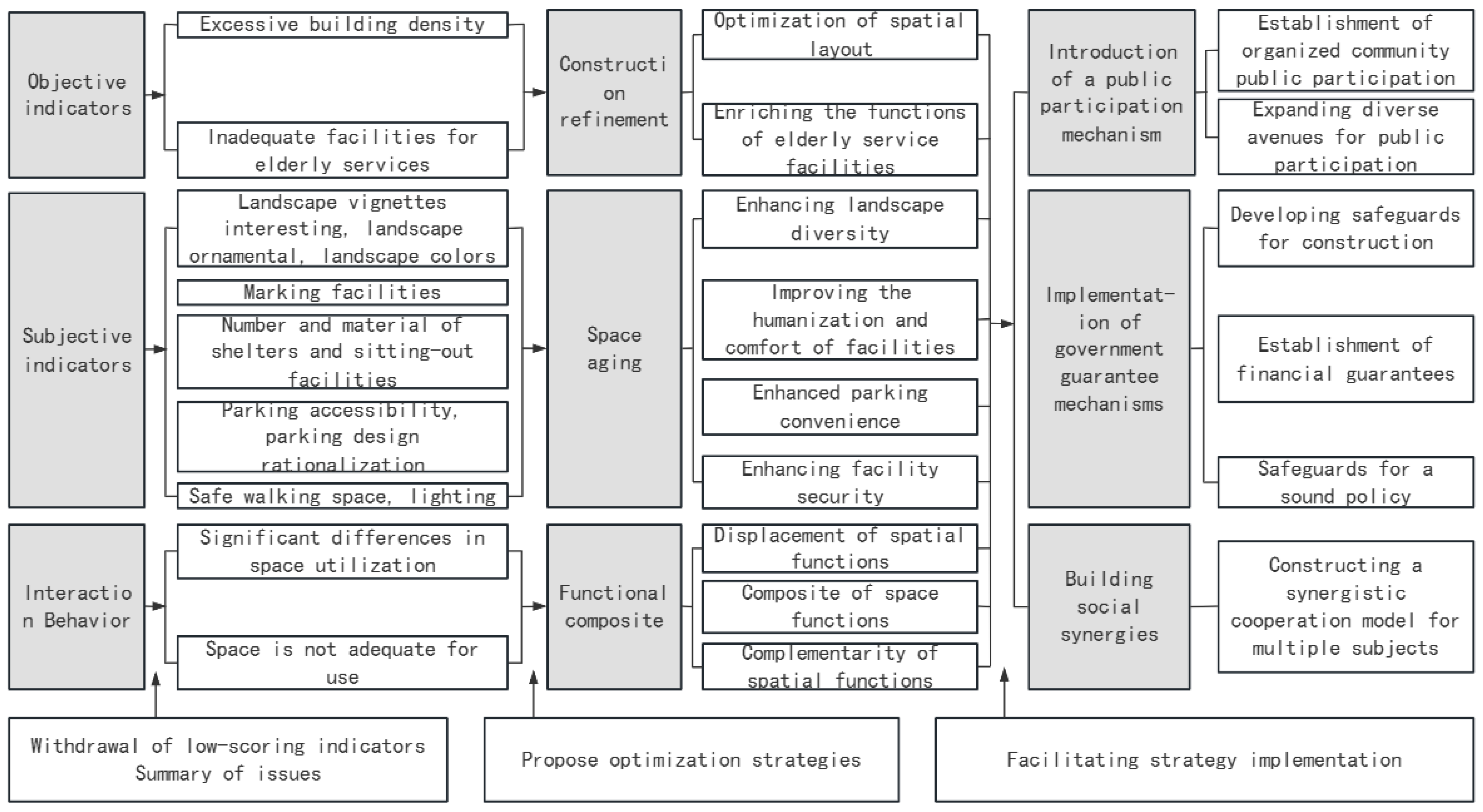

4. Railway Station Community Space Optimization Design

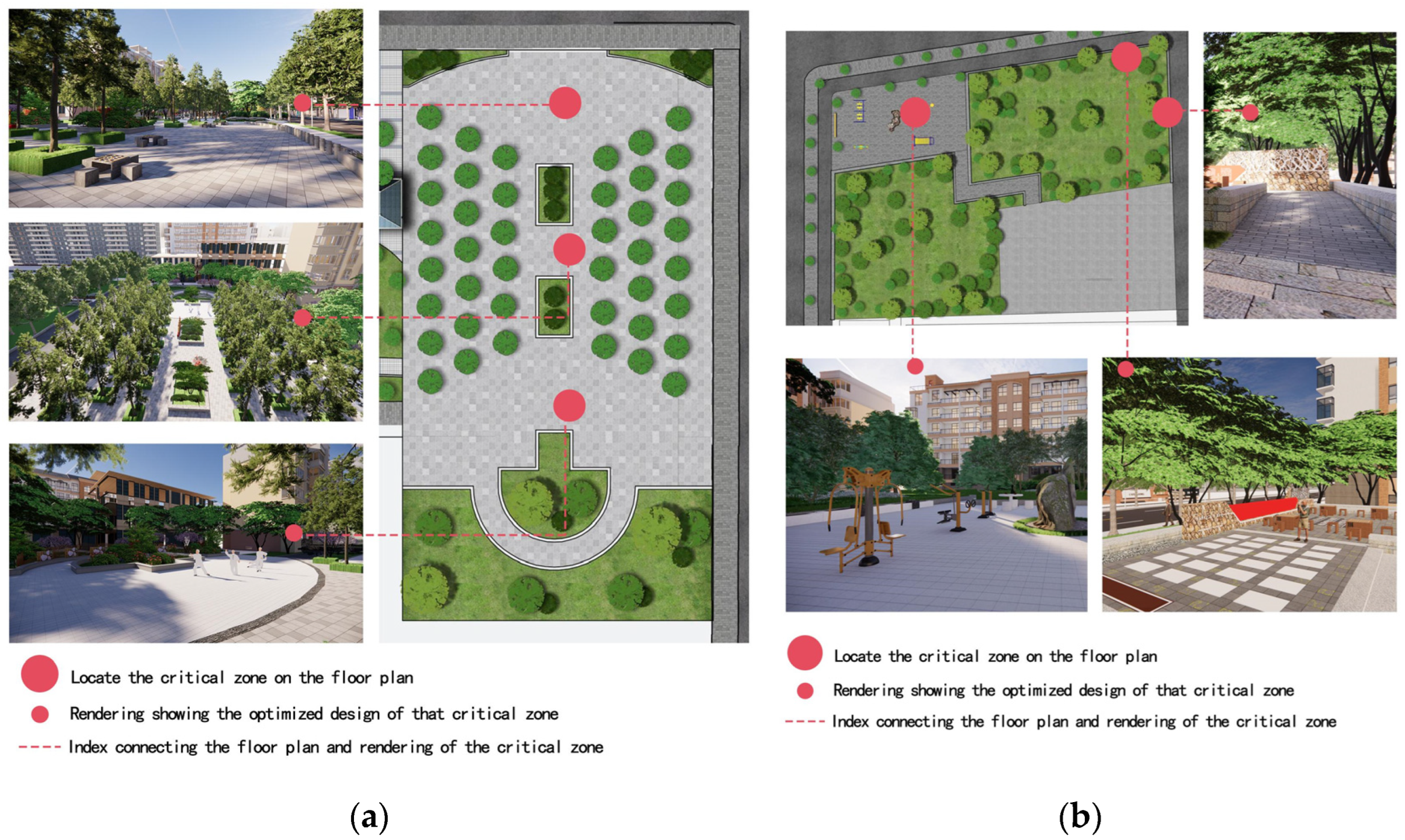

4.1. Rest Conversation Type of Interaction Space

4.2. Health Fitness Type of Interaction Space

4.3. Leisure and Entertainment Type of Interaction Space

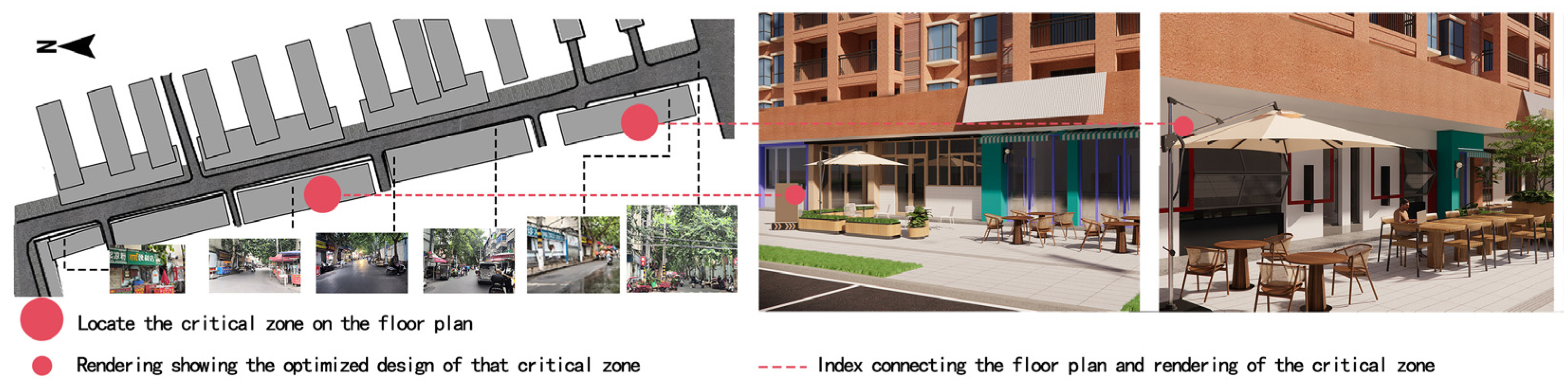

4.4. Interaction Spaces for Commercial Transactions

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Discuss

- (1)

- When exploring the temporal and spatial characteristics of the interaction behaviors of older adults, the results of this study echo Kurtenbach’s research on the importance of public space to social activities. Revealing the activity patterns of older adults in a specific period during the day helps to expand the understanding of the people groups that are often neglected in urban design [6]. In addition, this study also studied the influence of gender and physical condition differences on activity preference, which is consistent with the discussion of Lantz and Rossi on the use of gender in public space, emphasizing the importance of gender sensitivity in community space design [50].

- (2)

- In the construction of the evaluation index system, this research integrates subjective and objective factors, which is consistent with the social impact assessment method of Omuta and deepens the understanding of older adults’ satisfaction with community spaces [15]. The study of Dujardin further emphasized the impact of the built environment on residents’ self-rated health and provided important support for the methodology of this study [16]. The evaluation index system can be applied to other medium-sized communities in China to provide theoretical support for the evaluation of urban community interaction spaces.

5.2. Conclusions

- (1)

- Interaction behavior characteristics

- (2)

- Comprehensive evaluation index

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- China’s National Bureau of Statistics. Seventh National Census Bulletin (No. 5). Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/xxgk/sjfb/zxfb2020/202105/t20210511_1817200.html (accessed on 11 May 2021).

- Wei, S.; Kuang, F.; Guo, Z.; Ren, B. Research on public space optimization of intelligent community based on user requirements. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1756, 012007. [Google Scholar]

- Elsheshtawy, Y. Observing the public realm: William Whyte’s the social life of small urban spaces. Built Environ. 2015, 41, 399–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fariña, J.; Higueras, E.; Román, E. Ciudad Urbanismo y Salud. Documento Técnico de Criterios Generales Sobre Parámetros de Diseño Urbano para Alcanzar los Objetivos de una Ciudad Saludable con Especial Énfasis en el Envejecimiento Activo. 2019. Available online: https://oa.upm.es/65377/ (accessed on 28 January 2025).

- Grijalba, O.; Barrena-Herrán, M.; Modrego-Monforte, I. Riesgo para la salud asociado a la vivienda y su entorno. Propuesta metodológica para su evaluación. Cuad. De Investig. Urbanística 2022, 142, 78–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtenbach, S. Perceptions of social disorder in public spaces in a disadvantaged neighborhood: The example of Cologne-Chorweiler. J. Community Psychol. 2017, 45, 940–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, C.; Gómez, J. Recovery of Public Spaces: A Comparison of Three Case Studies to Recover Public Spaces in Vulnerable Communities in Santiago, Chile. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2020; Volume 503, p. 012099. [Google Scholar]

- Reich, R.B. (Ed.) The Power of Public Ideas; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, P.H.; Shlay, A.B. Residential mobility and public policy issues: “Why families move” revisited. J. Soc. Issues 1982, 38, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehl, J. Life Between Buildings; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Varo, I.; Delclos-Alio, X.; Miralles-Guasch, C. Jane Jacobs reloaded: A contemporary operationalization of urban vitality in a district in Barcelona. Cities 2022, 123, 103565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L. Research on the development trend of population ageing and old-age service policy during the 14th Five-Year Plan Period: A case study of Henan Province, a populous province. Price Theory Pract. 2021, 41, 30–34. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, S.; Kong, Y.; Song, G.; Luo, J. Model and experiment of urban service facility planning for 15-minute living circle. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2023, 78, 1484–1497. [Google Scholar]

- Omuta, G.E. The quality of urban life and the perception of livability: A case study of neighborhoods in Benin City, Nigeria. Soc. Indic. Res. 1988, 20, 417–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dujardin, C.; Lorant, V.; Thomas, I. Self-assessed health of elderly people in Brussels: Does the built environment matter? Health Place 2014, 27, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontokosta, C.E. The quantified community and neighborhood labs: A framework for computational urban science and civic technology innovation. J. Urban Technol. 2016, 23, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, S.; Wang, J. Research on the Optimal Design of Community Public Space from the Perspective of Social Capital. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, X.; Li, H.; Jia, X.; Gan, Y. Research on disaster prevention evaluation and strategy of community public space based on AHP method: A case study of Jiaozuo High-tech Zone. J. West. Hum. Settl. Environ. 2017, 32, 90–95. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Zou, Q.; Li, G. Research on public space of urban resettled communities based on vitality characteristics analysis: A case study of 6 resettled communities in Suzhou City. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2018, 38, 747–754. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, Y. Spatial evaluation of urban community living circle based on spatial behaviour analysis combined with space syntax: A case study of contemporary Yimei community living Circle in Beijing. Prog. Geogr. 2019, 43, 2157–2170. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, J.; Cao, X.J.; Huang, X.; Cao, X. Applying the IPA–Kano model to examine environmental correlates of residential satisfaction: A case study of Xi’an. Habitat Int. 2016, 53, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insch, A. Managing residents’ satisfaction with city life: Application of Importance–Satisfaction analysis. J. Town City Manag. 2010, 1, 164. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Jiang, J.; Chen, S.; Cao, H. Age-Friendly Street Construction: The Synergy of the Physical Environment in Old Urban Communities in Suzhou. Buildings 2024, 14, 3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Chen, B. Evaluation of Aging-Friendly Public Spaces in Old Urban Communities Based on IPA Method—A Case Study of Shouyi Community in Wuhan. Buildings 2024, 14, 2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Song, Y.; Sheng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, D. Restorative Potential Assessment of Public Open Space in Old Urban Communities in the Context of Aging—A Case Study of Dabeizhuang Community in Maanshan, China. Buildings 2024, 14, 2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Luo, S.; Jiang, J. Urban Residents’ Preferred Walking Street Setting and Environmental Factors: The Case of Chengdu City. Buildings 2023, 13, 1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Xia, Z.; Sun, X.; Wang, X.; Luo, S. Social Infrastructure and Street Networks as Critical Infrastructure for Aging Friendly Community Design: Mediating the Effect of Physical Activity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Q. Study on the Adaptability of Waterfront Open Space in Gongchen Bridge Section of Hangzhou Canal. Ph.D. Thesis, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Savageau, D. Places Rated Almanack: The Classic Guide for Finding Your Best Places to Live in America; Places Rated Books LLC: Montgomery, IL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y. A tale of two cities: Physical form and neighborhood satisfaction in metropolitan Portland and Charlotte. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2008, 74, 307–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminska, O.; Stezhko, Y.; Gliebova, L. Psycholinguistics of Virtual Communication in the Context of the Dependence on Social Networks. Psycholinguistics 2019, 25, 147–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibas, P.; Twardzik, M. Spatial analysis of commercial services in Poland. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2020; Volume 960, p. 032025. [Google Scholar]

- Gehl, J.; Gemzøe, L. Public Spaces-Public Life; Danish Architectural Press: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Du, D.; Pang, Q.; Wu, Y. Modern Comprehensive Evaluation Methods and Selected Cases; Tsinghua University Press: Beijing, China, 2008; pp. 111–134. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D. Introduction to Environmental Behavior; Tsinghua University Press: Beijing, China, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, V. Lively streets: Determining environmental characteristics to support social behavior. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2007, 27, 165–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Jiao, H. Quantitative Evaluation of Friendliness in Streets’ Pedestrian Networks Based on Complete Streets: A Case Study in Wuhan, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Cao, Z.; Xiong, F.; Zhang, L. Evaluation of public space suitability in existing urban communities: A case study of Yangjiachang Community in Nanchang City. Jiangxi Sci. 2019, 40, 1136–1141+1179. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y.; Xu, T.; Gan, W.; Bai, K. Evaluation and optimization strategy of outdoor sports space in old communities: A case study of seven communities in Wuhan. Cent. China Archit. Archit. 2022, 40, 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Y.S.; Sun, X. Research on elderly interaction space in urban community park based on AHP-Fuzzy comprehensive evaluation method: A case study of Nanhu Park in Nanjing. Theatre House 2019, 29, 195–197. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Z.; Zhu, J.; Xue, Y.; Chen, M. Research on the design index of suitable ageing renovation of existing residential buildings in urban areas. Constr. Sci. Technol. 2018, 17, 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Mei, W.B.; Hsu, C.Y.; Ou, S.J. Research on evaluation indexes and weights of the aging-friendly community public environment under the community home-based pension model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Liu, Y.; Qiu, T. Livability assessment of urban communities considering the preferences of different age groups. Complexity 2020, 2020, 8269274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menec, V.H.; Means, R.; Keating, N.; Parkhurst, G.; Eales, J. Conceptualizing age-friendly communities. Can. J. Aging/La Rev. Can. Du Vieil. 2011, 30, 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Housing and Urban Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China. Announcement of the Ministry of Housing and Urban Rural Development on the Publication of the National Standard Design Code for Residential Buildings for the Elderly. Available online: https://www.mohurd.gov.cn/gongkai/zc/wjk/art/2017/art_17339_231094.html (accessed on 1 July 2017).

- Ministry of Housing and Urban Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China. Announcement of the Ministry of Housing and Urban Rural Development on the Publication of the National Standard for Planning and Design Stan-dards for Urban Residential Areas. Available online: https://www.mohurd.gov.cn/gongkai/zc/wjk/art/2018/art_17339_238590.html (accessed on 10 July 2018).

- Leyva EW, A.; Beaman, A.; Davidson, P.M. Health impact of climate change in older people: An integrative review and implications for nursing. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2017, 49, 670–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferri Sanz, M.; Garcés Ferrer, J.; van Staalduinen, W.; Bond, R.; Hinkema, M. Evaluating Socio-Economic Impact of Age-Friendly Environments; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 117–138. [Google Scholar]

- Lantz, H.R.; Rossi, P.H. Why Families Move: A Study in the Social Psychology of Urban Residential Mobility. Marriage Fam. Living 1957, 19, 303–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehl, J. Life Between Buildings: Using Public Space, 4th ed.; He, R., Translator; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Jin, H., Translator; Yi Lin Press: Nanjing, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.; Lu, H.; Zheng, T.; Rong, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, W.; Yan, Y.; Tang, L. Vitality of urban parks and its influencing factors from the perspective of recreational service supply, demand, and spatial links. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y.; Zhuang, Y.; Yeh, A.G.; Xie, J.Y.; Ma, C.L.; Li, Q.Q. Measurements of POI-based mixed-use and their relationships with neighborhood vibrancy. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2017, 31, 658–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criterion Layer | Sub-Criterion Layer | Index Layer |

|---|---|---|

| B1 Diversity | C1 Spatial diversity | D1 Functional mix of space |

| D2 Number of activity areas | ||

| D3 Number of recreational facilities | ||

| C2 Landscape diversity | D4 Interesting landscape features | |

| D5 Ornamental landscape | ||

| D6 Landscape color | ||

| B2 Humanization | C3 Space humanization | D7 Intensity of community management |

| D8 Activity orientation | ||

| C4 Humanization of facilities | D9 Signage | |

| D10 Sanitation facilities | ||

| C5 Service humanization | D11 Service radius of refuse collection point | |

| D12 Ideology of respect for the elderly | ||

| D13 Service diversification | ||

| B3 Comfort | C6 Comfortable space | D14 Static and dynamic zoning |

| D15 Microclimate | ||

| D16 Neighborhood atmosphere | ||

| C7 Comfortable facilities | D17 Sheltering facilities | |

| D18 Number of sitting-out facilities | ||

| D19 Open space materials | ||

| B4 Convenience | C8 Convenient access | D20 Effective width of walking track |

| D21 Road accessibility | ||

| D22 Road levelling | ||

| D23 Accessibility of activity venues | ||

| C9 Convenient parking | D24 Parking convenience | |

| D25 Parking design rationality | ||

| B5 Safety | C10 Space safety | D26 Space layout safety |

| D27 Safe walking space | ||

| C11 Facility safety | D28 Facility maintenance | |

| D29 Lighting facilities |

| Criterion Layer | Index Layer |

|---|---|

| B6 Space environment | D30 Air quality |

| D31 Building density | |

| B7 Public service facilities | D32 Pension facility density |

| D33 Medical facility density | |

| D34 Sanitation facility density | |

| B8 Road traffic | D35 Bus station density |

| D36 Intersection density |

| Criterion Layer | Index Layer | Data Sources | Calculation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Space environment | Air quality | China Environmental Monitoring Station | Each community value was determined by spatial interpolation |

| Density of buildings | Community land use status quo, street neighborhood committee statistical data | Area of buildings within the community/total area of all classes | |

| Public service facilities | Density of elderly care facilities | Field survey statistics data and Baidu map POI data | The number of universities for the elderly, associations for the elderly, activity centers for the elderly, community daycare institutions, community nursing homes, and community elderly care service centers (stations) is divided by the community area |

| Density of medical facilities | Field survey statistics data and Baidu map POI data | Number of medical rehabilitation institutions/total area of the community | |

| Density of sanitary facilities | Field survey statistics data and Baidu map POI data | Number of public toilets, garbage disposal stations, and garbage cans/community area | |

| road traffic | Density of bus stops | Field survey statistics data and Baidu map POI data | Number of bus stops/total area of the community |

| Density of intersection s | Field survey statistics | Number of intersections/total area of the community |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, M.; Zhu, N.; Peng, X.; Huang, J.; Ji, L.; Meng, X.; Song, S.; Liu, S. Evaluation Study of Public Interaction Spaces for the Elderly in a Community—Taking the Railway Station Community in Jiaozuo City as an Example. Buildings 2025, 15, 517. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15040517

Zhou M, Zhu N, Peng X, Huang J, Ji L, Meng X, Song S, Liu S. Evaluation Study of Public Interaction Spaces for the Elderly in a Community—Taking the Railway Station Community in Jiaozuo City as an Example. Buildings. 2025; 15(4):517. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15040517

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Min, Nana Zhu, Xueyi Peng, Jing Huang, Lijuan Ji, Xiangyun Meng, Simin Song, and Simeng Liu. 2025. "Evaluation Study of Public Interaction Spaces for the Elderly in a Community—Taking the Railway Station Community in Jiaozuo City as an Example" Buildings 15, no. 4: 517. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15040517

APA StyleZhou, M., Zhu, N., Peng, X., Huang, J., Ji, L., Meng, X., Song, S., & Liu, S. (2025). Evaluation Study of Public Interaction Spaces for the Elderly in a Community—Taking the Railway Station Community in Jiaozuo City as an Example. Buildings, 15(4), 517. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15040517