Gig Regulation: A Future Guide for the Construction Industry

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Overview of Various Megatrends That Cause Future Workforce Disruption

2.1.1. Globalization

2.1.2. Technological Shift

2.1.3. Rise of a New Social Contract

2.1.4. Urbanization

2.2. The New Workforce Model

- (a)

- Full-Time Workforce Model

- (b)

- Gig Workforce Model

2.3. Kinds of Work Performed by Gig Workers in the Construction Industry

2.3.1. Specialized Jobs

- (i)

- Design Phase

- (ii)

- Construction Phase

- (iii)

- Operations and Facility Management Phase

2.3.2. Commodity Service Jobs

2.3.3. Project-Based Jobs

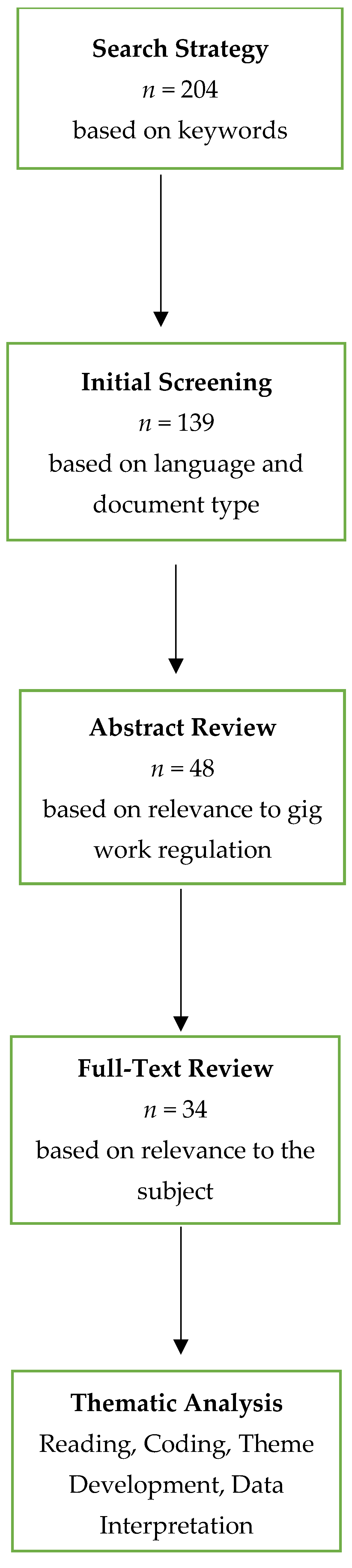

3. Method

4. Result

4.1. Overview of Article Publication Year

4.2. Gig Workers Issues

4.3. Regulatory Measures

- (a)

- Tailor-made regulation (in the areas of instruction, freedom of schedules and working hours, freedom to work on more than one platform, employees’ liability for damages, minimum wage, reimbursement of expenses, and subsidiary labour law) for the gig economy because the individuals that work on an online platform are subject to risks that are specific [65].

- (b)

- Ref. [66] proposed the protection of workers by creating new categories of worker benefits and protection, new policies’ development, and the advocacy and engagement of workers.

- (c)

- Ref. [67] proposed that a functional concept of the entrepreneur be adopted as a regulatory solution to external work, with platforms.

- (d)

- Ref. [68] proposed some regulatory measures for addressing gig workers issues, including the following: allowing gig workers to access the Fair Work Commission to resolve disputes; establishing a specific tribunal to handle disputes involving gig workers; mandating that platforms provide worker compensation coverage; requiring platforms to provide adequate training to workers; requiring platforms to disclose average earnings data to relevant government agencies; ensuring that gig workers are paid at least the minimum wage; conducting in-depth studies to understand the long-term impacts of gig work on labour markets and worker well-being; and comparing the experiences of gig workers across different countries to identify best practices and potential policy solutions.

- (e)

- Ref. [69] highlighted the regulatory focus to include neutralizing unemployment benefits for all employment forms and ensuring that labour standards on a par with collective agreements are adhered to.

- (f)

- Ref. [70] stated that, in 2020, the State of California enacted a law (Assembly Bill 5) that, for purposes of the State’s labour code, deems people providing labour or services for remuneration, such as self-directed gig workers, to be employees rather than independent contractors (the law does not apply if the hiring gig entity can demonstrate that the person performing the work is free from the entity’s control and direction in the performance of the work). Also, the regulations direct the State’s unemployment agency to help gig workers file for unemployment benefits on the same footing as would traditional employees.

- (g)

- Ref. [71] highlighted the need for new regulations which should contain features such as the recognition of platform workers as collective bargaining actors explicitly, a presumption of employment relationships’ reinforcement, agreements on fundamental relationship governing principles, and the freedom to set up working hours and schedules.

- (h)

- Ref. [72] stated that the first European law on platform work (Riders’ Law 12 of 2021) was developed in Spain. The law included a reform in the presumption of employment for platform workers and the right of workers’ representatives to be consulted and report on algorithm use in the workplace.

- (i)

- Ref. [73] highlighted the regulatory measures taken by the Indian government as defining gig workers under the Code of Social Security, while also proposing non-regulatory measures like ensuring a mental health module during skilling courses provided by aggregators, access to mental health facilities, updating and localising the minimum wage, increasing outreach, and simplifying the process of availing of social benefits, etc.

- (j)

- Ref. [74] identified the role of state and non-state actors in regulating the gig economy as pre-regulatory considerations (stage 1), enactment of standards (stage 2), and enforcement (stage 3). This describes how the state may open up employment regulatory spaces to other non-state private actors, which then have a ‘ceding’ effect that privileges employers rather than workers or unions. The exercise of power in negotiations, lobbying, and the discourse of persuasion constitute another lever by which non-state actors seek to seize regulatory spaces and, in so doing, privilege corporate accumulation over universal employment rights.

- (k)

- Ref. [75] proposed the need for a transnational regulatory arrangement for platform governance.

4.4. Proposed “Regulatory Interactions” Based on Laudau’s Labour Dispute Regulation Framework

Regulatory Interactions

4.5. Nature of Issues Addressed by the Proposed Regulatory Measures and Their Regulatory Interactions

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maskuriy, R.; Selamat, A.; Ali, K.N.; Maresova, P.; Krejcar, O. Industry 4.0 for the construction industry—How ready is the industry? Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameh, O.J.; Daniel, E.I. Human resource management in the nigerian construction firms: Practices and challenges. J. Constr. Bus. Manag. 2017, 1, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, J.; Bersin, J.; Bourke, J.; Danna, R.; Jarrett, M.; Knowles-Cutler, A.; Lewis, H.; Pelster, B. The Future of the Workforce: Critical Drivers and Challenges; Deloitte: Hong Kong, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yalcin, B. What Is Globalisation. In Comparative Social Policy Programme; 2018, pp. 1–4. Available online: https://www.piie.com/microsites/globalization/what-is-globalization (accessed on 31 December 2023).

- Skare, M.; Soriano, D.R. How globalization is changing digital technology adoption: An international perspective. J. Innov. Knowl. 2021, 6, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banik, N.; Padalkar, M. The spread of gig economy: Trends and effects. Foresight-Russia 2021, 15, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlich, M. Misclassification in construction: The original gig economy. ILR Rev. 2021, 74, 1202–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crayne, M.P.; Brawley Newlin, A.M. Driven to succeed, or to leave? the variable impact of self-leadership in rideshare gig work. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2024, 35, 98–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, J.; Grantham, C. The future of work: Changing patterns of workforce management and their impact on the workplace. J. Facil. Manag. 2003, 2, 142–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PwC. Workforce of the Future. 2018. Available online: https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/services/people-organisation/workforce-of-the-future/workforce-of-the-future-the-competing-forces-shaping-2030-pwc.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2023).

- McGovern, M. Thriving in the Gig Economy: How to Capitalize and Compete in the New World of Work; Red Wheel/Weiser: Newburyport, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, J. Nonstandard work arrangements and worker health and safety. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2017, 60, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirmaz, A.; Goldar, M.; Klein, S. Illuminating the Shadow Workforce: Insights into the Gig Workforce in Businesses; ADP Research Institute: Roseland, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Artecona, R.; Chau, T. Labour Issues in the Digital Economy; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Z.M.; Aggarwal, N.; Cowls, J.; Morley, J.; Taddeo, M.; Floridi, L. The ethical debate about the gig economy: A review and critical analysis. Technol. Soc. 2021, 65, 101594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, R.; White, K.E. What is globalization? In The Blackwell Companion to Globalization; Wiley Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 54–66. [Google Scholar]

- Mohajan, H. The first industrial revolution: Creation of a new global human era. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2019, 5, 377–387. [Google Scholar]

- Taalbi, J. Origins and pathways of innovation in the third industrial revolution. Ind. Corp. Change 2019, 28, 1125–1148. [Google Scholar]

- Schwab, K.; Davis, N. Shaping the Future of the Fourth Industrial Revolution Crown Currency; Crown Currency: Sydney, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sheik, I.; Singh, P.K. Industry 4.0: Managerial roles and challenges. Int. J. Innov. Eng. Res. Technol. 2020, 5, 378–381. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, C.; Robert, L.; Frady, K.; Arroyos, A. A hiring paradigm shift through the use of technology in the workplace. In Managing Technology and Middle-and Low-Skilled Employees: Advances for Economic Regeneration; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2019; pp. 49–59. [Google Scholar]

- Leso, V.; Fontana, L.; Iavicoli, I. The occupational health and safety dimension of industry 4.0. La Med. Del Lav. 2018, 109, 327. [Google Scholar]

- Leesakul, N.; Oostveen, A.; Eimontaite, I.; Wilson, M.L.; Hyde, R. Workplace 4.0: Exploring the implications of technology adoption in digital manufacturing on a sustainable workforce. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khachaturyan, A.A. Digitalization of the economy: Social threats. Resour. Environ. Econ. 2022, 4, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghimien, D.; Aigbavboa, C.; Meno, T.; Ikuabe, M. Unravelling the risks of construction digitalisation in developing countries. Constr. Innov. 2021, 21, 456–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahato, M.; Kumar, N.; Jena, L.K. Re-thinking gig economy in conventional workforce post-COVID-19: A blended approach for upholding fair balance. J. Work-Appl. Manag. 2021, 13, 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organisation (Geneva). Non-Standard Employment Around the World: Understanding Challenges, Shaping Prospects; International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, J.V. Urbanization and growth. In Handbook of Economic Growth; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 1543–1591. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, M.; Imitiyaz, I. Urbanization concepts, dimensions and factors. Int. J. Recent Sci. Res. 2018, 9, 23513–23523. [Google Scholar]

- Benach, J.; Gimeno, D.; Benavides, F.G.; Martinez, J.M.; del Mar Torné, M. Types of employment and health in the european union: Changes from 1995 to 2000. Eur. J. Public Health 2004, 14, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoukens, P.; Barrio, A. The changing concept of work: When does typical work become atypical? Eur. Labour Law J. 2017, 8, 306–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, G.; Shrivastava, A.K. Future of gig economy: Opportunities and challenges. IMI Konnect 2020, 9, 14–27. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J.R.; Mastracci, S.H. The blended workforce: Alternative federal models. Public Pers. Manag. 2008, 37, 363–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horns, K.W.; Jenkins, R.B. Is the profession of civil engineering becoming a commodity? you should know the answer. Leadersh. Manag. Eng. 2011, 11, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappell, D.; Dunn, M.H. The Architect in Practice; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Anyanwu, C.I. The role of building construction project team members in building projects delivery. J. Bus. Manag. 2013, 14, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezenwa, G.C. The role of a professional builder in facility management. Sci. Prepr. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subbiah, S.; Saranya, R.; Shakthi, R.; Swetha, R. Buildmart mobile application for construction commodity. In 2022 International Conference on Communication, Computing and Internet of Things (IC3IoT), Chennai, India, 10–11 March 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, Y. Council Post: How Organizations Can Become Project-Based in the Future of Work. Forbes, 2 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Vrijhoef, R.; Koskela, L. A critical review of construction as a project-based industry; identifying paths towards a project-independent approach to construction. In Proceedings of the CIB Symposium, Combining Forces, Advancing Facilities Management & Construction Through Innovation Series, Helsinki, Finland, 13–16 June 2005; pp. 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Aigbe, F.; Aigbavboa, C.; Aliu, J.; Amusan, L. Understanding the Future Competitive Advantages of the Construction Industry. Buildings 2024, 14, 1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, R.; McGregor, M.; Brown, B.; Lampinen, A. Fleeting Alliances and Frugal Collaboration in Piecework: A Video-Analysis of Food Delivery Work in India. Comput. Support. Coop. Work. (CSCW) 2024, 33, 1289–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baber, A. Labour market engineers: Reconceptualising labour market intermediaries with the rise of the gig economy in the United States. Work Employ. Soc. 2024, 38, 723–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljungholm, D.P. Employee–employer relationships in the gig economy: Harmonizing and consolidating labor regulations and safety nets. Contemp. Read. Law Soc. Justice 2018, 10, 144–150. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, M. The regulatory challenges of ‘Uberization’in China: Classifying ride-hailing drivers. Int. J. Comp. Labour Law Ind. Relat. 2017, 33, 269–294. [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann, F.; Hoose, F. From loopholes to deinstitutionalization: The platform economy and the undermining of labor and social security institutions. Partecip. E Confl. 2023, 15, 800–826. [Google Scholar]

- Brou, D.; Chatterjee, A.; Coakley, J.; Girardone, C.; Wood, G. Corporate governance and wealth and income inequality. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2021, 29, 612–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, J.; Nicholson, D.; Pekarek, A. Should we take the gig economy seriously? Labour Ind. A J. Soc. Econ. Relat. Work. 2017, 27, 232–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A.J.; Lehdonvirta, V. Platforms disrupting reputation: Precarity and recognition struggles in the remote gig economy. Sociology 2023, 57, 999–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyutov, N.; Voitkovska, I. Remote Work and Platform Work: The Prospects for Legal Regulation in Russia. Russ. Law J. 2021, 9, 81–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, L.L.; Moscon, D.C.; Dias, L.M.; Oliveira, S.M.; Alves, H.M. Digiwork: Reflections on the scenario of work mediated by digital platforms in Brazil. RAM Rev. Adm. Mackenzie 2023, 24, eRAMR230060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlicher, K.D.; Schulte, J.; Reimann, M.; Maier, G.W. Flexible, self-determined… and unhealthy? An empirical study on somatic health among crowdworkers. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 724966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macdonald, F.; Charlesworth, S. Regulating for gender-equitable decent work in social and community services: Bringing the state back in. J. Ind. Relat. 2021, 63, 477–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangold, S. Platform work and traditional employee protection: The need for alternative legal approaches. Eur. Labour Law J. 2024, 15, 726–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Au-Yeung, T.C.; Qiu, J. Institutions, occupations and connectivity: The embeddedness of gig work and platform-mediated labour market in Hong Kong. Crit. Sociol. 2022, 48, 1169–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolini, A. Regulating Platform Work in the UK and Italy: Politics, Law and Political Economy. Int. J. Comp. Labour Law Ind. Relat. 2024, 40, 131–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Liu, T.; Guo, L.; Xie, Z. The disembedded digital economy: Social protection for new economy employment in China. Soc. Policy Adm. 2020, 54, 1246–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsimpogiorgos, N.; Frenken, K.; Herrmann, A.M. Platform adaptation to regulation: The case of domestic cleaning in Europe. J. Ind. Relat. 2023, 65, 156–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A.J.; Martindale, N.; Lehdonvirta, V. Dynamics of contention in the gig economy: Rage against the platform, customer or state? New Technol. Work Employ. 2023, 38, 330–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaine, S.; Josserand, E. The organisation and experience of work in the gig economy. J. Ind. Relat. 2019, 61, 479–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novitz, T. Multi-level disputes relating to freedom of association and the right to strike: Transnational systems, actors and resources. Int. J. Comp. Labour Law Ind. Relat. 2020, 36, 471–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albornoz, M.B.; Chávez, H. The challenges of gig economy and Fairwork in Ecuador. Digit. Geogr. Soc. 2024, 6, 100073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobroń-Gąsiorowska, Ł. Gig Workers in Poland: The Quest for a Protection Model. E-J. Int. Comp. Labour Stud. 2023, 12, 42–55. [Google Scholar]

- Todoli-Signes, A. The ’gig economy’: Employee, self-employed or the need for a special employment regulation? Transf. Eur. Rev. Labour Res. 2017, 23, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldkind, L.; McNutt, J.G. Vampires in the technological mist: The sharing economy, employment and the quest for economic justice and fairness in a digital future. Ethics Soc. Welf. 2019, 13, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prassl, J.; Risak, M. Legal responsibility in the gig economy: The employer perspective. Rev. Minist. Empl. Segur. Soc. Rev. Minist. Trab. Migr. Segur. Soc. 2019, 144, 31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Goods, C.; Veen, A.; Barratt, T. “Is your gig any good?” Analysing job quality in the Australian platform-based food-delivery sector. J. Ind. Relat. 2019, 61, 502–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engblom, S.; Lundberg, M. Answers to the New trade union strategies for new forms of employment questionnaire. Eur. Labour Law J. 2019, 10, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harpur, P.; Blanck, P. Gig workers with disabilities: Opportunities, challenges, and regulatory response. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2020, 30, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartmann-Cortés, K. What (if anything) May Justify a New Policy Regulation for Gig-delivery Workers? The Case of Rappi in Argentina. E-J. Int. Comp. Labour Stud. 2021, 10, 5–29. [Google Scholar]

- Horváth, I.; del Prado, D.P.; Petrovics, Z.; Sitzia, A. The Role of Digitisation in Employment and Its New Challenges for Labour Law Regulation. ELTE Law J. 2021, 101–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, V.; Shireshi, S.S. Analysing the gig economy in India and exploring various effective regulatory methods to improve the plight of the workers. J. Asian Afr. Stud. 2022, 57, 1343–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inversi, C.; Dundon, T.; Buckley, L.-A. Work in the gig-economy: The role of the state and non-state actors ceding and seizing regulatory space. Work Employ. Soc. 2023, 37, 1279–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doorn, N.; Ferrari, F.; Graham, M. Migration and migrant labour in the gig economy: An intervention. Work Employ. Soc. 2023, 37, 1099–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landau, I.; Howe, J.; Thi, T.; Tran, K.; Mahy, P.; Sutherland, C. Regulatory pluralism and the resolution of collective labour disputes in southeast asia. J. Ind. Relat. 2023, 65, 472–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberlein, B.; Abbott, K.W.; Black, J.; Meidinger, E.; Wood, S. Transnational business governance interactions: Conceptualization and framework for analysis. Regul. Gov. 2014, 8, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesala Khethisa, B.; Tsibolane, P.; Van Belle, J.-P. Surviving the Gig Economy in the Global South: How Cape Town Domestic Workers Cope. In The Future of Digital Work: The Challenge of Inequality: IFIP WG 8.2, 9.1, 9.4 Joint Working Conference, IFIPJWC 2020, Hyderabad, India, 10–11 December 2020; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Adu-Pakoh, K. Labour practices in ghana-a case study of the ghana water company limited. Int. J. Sci. Basic Appl. Res. (IJSBAR) 2017, 31, 125–132. [Google Scholar]

- Laws.Africa Legislation Commons Namibia. Labour Act, Act 11 of 2007. 2007. Available online: https://namiblii.org/akn/na/act/2007/11/eng@2023-03-15/source.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2023).

- Bendix, S. Industrial Relations in South Africa; Juta and Company Ltd.: Cape Town, South Africa, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sychenko, E.; Laruccia, M.; Cusciano, D.; Chikireva, I.; Wang, J.; Smit, P. Non-Standard Employment in the BRICS Countries. BRICS Law J. 2020, 7, 4–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevchuk, A.; Strebkov, D. Digital platforms and the changing freelance workforce in the russian federation: A ten-year perspective. Int. Labour Rev. 2023, 162, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Cooke, F.L. Internet platform employment in china: Legal challenges and implications for gig workers through the lens of court decisions. Relat. Ind./Ind. Relat. 2021, 76, 541–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Thomas MacDonald, I. Modeling the job quality of ‘work relationships’ in china’s gig economy. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2022, 60, 855–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, S.A.; Bradley, D.H.; Shimabukuru, J.O. What Does the Gig Economy Mean for Workers? Congressional Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2016.

- Youghp-Content. How the Construction Industry Is Affected by the Gig Economy. Handle. 2020. Available online: https://www.handle.com/gig-economy-construction/ (accessed on 9 June 2024).

- Koutsimpogiorgos, N.; van Slageren, J.; Herrmann Andrea, M.; Frenken, K. Conceptualizing the Gig Economy and Its Regulatory Problems. Policy Internet 2020, 12, 525–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author(s) | Megatrends |

|---|---|

| [3] | Technology, globalization, demographic upheaval, and the rise of a new social contract |

| [10] | Technological shift, demographic shift, and rapid urbanization, etc. |

| Author(s) | Issue(s) |

|---|---|

| [43] | Lack of worker protections |

| [7,44,45,46] | Misclassification |

| [47] | Social protection |

| [48,49,50] | Precarious nature of job |

| [51] | Labour rights |

| [52] | Lack of integrative social and work model |

| [53] | Health and regulation |

| [54] | Low rates of unionisation |

| [55] | Lack of protective labour laws |

| [56] | Weak regulation and protection |

| [57] | Industrial relations and labour rights |

| [58,59,60] | Labour and social protection |

| [61] | New organization of work |

| [62] | Transnational business model |

| [63,64] | Labour rights and regulatory issues |

| Proposed Regulatory Measures | Challenges | Regulatory Measures | Regulatory Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regulatory Measures (Author) | Gig Economy-Induced/Occupational-Related | Regulatory Measures | Regulatory Interaction |

| [65] | Gig economy-induced challenge | A tailor-made regulation (in the areas of instruction, freedom of schedules and working hours, freedom to work on more than one platform, employees’ liability for damages, minimum wage, reimbursement of expenses, and subsidiary labour law) for the gig economy because the individuals that work on an online platform are subject to risks that are specific. | Competition, Coordination (coherence, carving out), Co-optation Chaos |

| [66] | Gig economy-induced challenge | Protection of workers by creating new categories of worker benefits and protection, new policies development and advocacy, engagement of workers. | Competition, Coordination (coherence, carving out), Co-optation Chaos. |

| [67] | Gig economy-induced challenge | A functional concept of the entrepreneur being adopted as a regulatory solution to external work with platforms. | Competition, Coordination (coherence, carving out), Co-optation Chaos |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aigbe, F.; Aigbavboa, C.; Aliu, J.; Amusan, L. Gig Regulation: A Future Guide for the Construction Industry. Buildings 2025, 15, 490. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15030490

Aigbe F, Aigbavboa C, Aliu J, Amusan L. Gig Regulation: A Future Guide for the Construction Industry. Buildings. 2025; 15(3):490. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15030490

Chicago/Turabian StyleAigbe, Fortune, Clinton Aigbavboa, John Aliu, and Lekan Amusan. 2025. "Gig Regulation: A Future Guide for the Construction Industry" Buildings 15, no. 3: 490. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15030490

APA StyleAigbe, F., Aigbavboa, C., Aliu, J., & Amusan, L. (2025). Gig Regulation: A Future Guide for the Construction Industry. Buildings, 15(3), 490. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15030490