1. Introduction

A significant proportion of Australian university students (83.9%) report elevated distress levels, indicating a high risk of developing mental health disorders [

1]. This is attributed to a combination of academic pressures, financial stress, and the challenge of balancing studies with work and personal responsibilities [

2]. Many Australian universities encourage students to gain industry experience while studying to enhance their employability by providing practical skills and real-world insights that complement academic learning [

3]. Moreover, the work-integrated learning (WIL) model, implemented across various degree programs in Australia, aims to enhance employability by connecting students with real-world work experiences and bridging the gap between theoretical knowledge and practical application [

4,

5]. This approach also fosters stronger industry-academia partnerships, which can lead to more relevant and dynamic curricula that better prepare students for the workforce [

6].

However, despite the recognised benefits of Australia’s current tertiary education model, recent research indicates a growing prevalence of mental health issues among university students. This trend is largely attributed to the increasing difficulty of balancing academic responsibilities with work commitments [

7]. Research by Zajac et al. [

8] reveals that approximately 15% of students drop out of university within their first academic year, underscoring a significant concern for educational institutions regarding student retention. The study further indicates that mental health conditions are a notable risk factor for retention success during this critical period. These findings are relevant to a wide range of degree programs in Australian universities, including Nursing, Health, Architecture and Building, Engineering, Education, Agriculture, Environment, and related fields. They align with Li and Carroll’s [

9] research on factors influencing dropout rates and academic performance in Australian higher education, highlighting the need for further investigation in these areas.

Several studies have recently explored the work–study conflict experienced by undergraduate BE students. These investigations highlight three primary areas: burnout, depression, and stress management. Burnout has been a central theme in many studies addressing work–study conflicts. For example, Lingard [

10] examined the relationship between paid work commitments, burnout levels, and university satisfaction among property and construction students at an Australian university. Lingard et al. [

11] extended this analysis by comparing burnout levels between construction students in Australia and Hong Kong. Moore and Loosemore [

12] further investigated burnout among construction management students at another Australian institution, while Jia et al. [

13] studied its impact on dropout rates among architecture students in Hong Kong. Bakare et al. [

14] expanded the scope by examining burnout syndrome in electrical and building technology undergraduates in Nigeria. Depression among BE students has also been a growing area of interest. Loosemore et al. [

15] explored the prevalence of depressive symptoms and the availability of support mechanisms for construction management, civil engineering, and architecture undergraduates at an Australian university. Additionally, stress management strategies have been examined to understand how BE students cope with their academic and professional pressures. Groen et al. [

16] investigated stress experiences and resilience-building strategies among undergraduate construction students. Similarly, Turner et al. [

17] conducted a cross-country study involving students from Australia, the UK, and the US, focusing on their perceptions of resilience, well-being, and influencing factors.

Although previous studies have examined the prevalence of burnout and depression among BE students who balance work and studies, there remains a knowledge gap for a more comprehensive investigation. This includes exploring causal factors, coping mechanisms, dynamic interactions among these variables, and impacts on students’ academic performance and attrition rates. Furthermore, most existing research has focused on single-degree programs, highlighting the necessity for broader studies encompassing diverse BE disciplines. Therefore, this research aims to (1) explore different types of academic and work stressors encountered by BE students and (2) examine the effects of the stressors on the health, well-being, and academic performance of BE students.

2. Literature Review

Universities increasingly encourage students to gain industry experience during their studies, aiming to enhance employability by integrating practical skills and real-world insights with academic learning [

3]. This strategy also strengthens industry–academia partnerships, promoting the development of dynamic and relevant curricula that better prepare students for workforce demands [

6]. However, the benefits of this model are counterbalanced by rising mental health challenges among university students, often attributed to the difficulty of balancing academic responsibilities with work commitments [

7]. Alarmingly, about 15% of students leave university within their first year, a figure that rises to 25% among Australian undergraduates [

8]. This trend affects a wide range of disciplines, including nursing, health, built environment, engineering, education, agriculture, and environmental sciences [

9]. This section examines the academic and work-related stressors affecting the well-being, health, and academic performance of built environment students as reported in existing literature.

2.1. Academic Stressors

Built environment programs are particularly demanding, with academic stressors profoundly affecting students’ mental health, often leading to anxiety, depression, and nervousness. Key contributors include compulsory school programs, examinations, and heavy academic workloads [

18]. The structured, rigid nature of compulsory programs limits flexibility, making it challenging for students to balance academic responsibilities with personal needs or extracurricular interests [

19]. Strict schedules and tight deadlines create a persistent sense of urgency, fostering chronic stress. Examinations, as high-stakes assessments, amplify this pressure by closely linking academic success and career prospects to performance [

20]. Fear of failure drives students to dedicate long hours to study, often at the cost of their mental and physical health.

Simultaneously managing assignments, projects, and presentations further contributes to burnout and exhaustion. Programs employing flipped classroom models, which shift instructional content outside of class to focus on active learning during sessions, can intensify stress if insufficient scaffolded support is provided [

21,

22]. The self-learning demands of such models can overwhelm students. Additionally, the competitive environment of built environment programs exacerbates stress, as students strive to excel academically while managing internships, part-time jobs, and extracurricular activities.

Self-inflicted stress, including self-imposed expectations and perceptions of self-efficacy, also plays a significant role in increasing academic stress among students [

23]. This highlights a strong link between academic stress and mental health challenges. The cumulative impact of these stressors creates a cycle that is difficult to break, negatively affecting students’ well-being and academic performance.

2.2. Work Stressors

In addition to academic pressures, students working in the Architecture, Engineering, and Construction (AEC) industry face significant work-related stressors. The AEC sector is inherently demanding, characterised by long hours, tight deadlines, and chaotic work environments [

24]. Balancing multiple roles, students often struggle to meet strict project deadlines while managing academic obligations, leaving little time for rest or recovery. The unpredictable nature of AEC work, including frequent changes in schedules and locations further disrupts their ability to maintain consistent study routines, complicating academic progress [

25].

The high-pressure environment of the AEC industry exacerbates stress and anxiety, particularly among students still developing professional skills and confidence. Expectations to perform at a high level in a fast-paced, competitive setting can lead to self-doubt and fear of failure [

15]. For newcomers, the steep learning curve and the need to adapt quickly to workplace culture pose additional challenges [

26]. These factors, combined with academic pressures, significantly strain students’ mental health.

The dual burden of managing studies and the demanding physical and mental challenges of AEC work often leads to chronic fatigue, burnout, and reduced academic performance [

26]. The cumulative impact of these stressors not only jeopardises students’ academic success but also poses a serious risk to their overall well-being.

2.3. Poor Health and Well-Being

The combined impact of academic and work stressors often results in significant physical and mental health challenges for students, affecting their daily functioning and overall well-being. Stress disrupts normal physiological processes, potentially causing sleep disturbances, musculoskeletal pain, gastrointestinal issues, and weakened immune function [

27,

28].

In addition to physical health problems, prolonged stress increases the risk of anxiety, depression, and other severe mental health conditions [

15,

29]. Common symptoms include burnout, panic attacks, anxiety disorders, somatic complaints, suicidal ideation, self-harm, and substance use or addiction [

30,

31,

32]. These mental health challenges not only impair academic performance and daily functioning but, if left unaddressed, can also lead to lasting psychological effects.

2.4. Negative Academic Outcomes

Kamardeen and Sunindijo [

29] examine the intricate relationship between stressors, mental health challenges, and academic performance among graduate built environment students, emphasising the relevance of the stress–performance inverted U-curve. This model illustrates how moderate stress can enhance performance, while insufficient or excessive stress results in diminished outcomes. Low stress levels often lead to boredom and disengagement, reflecting the curve’s left side, whereas high stress levels, linked to mental health issues like anxiety and depression, align with the curve’s right side, where performance and well-being significantly decline.

While moderate stress can motivate students, chronic or excessive stress from academic, work, and personal pressures frequently results in anxiety, depression, and burnout, severely impairing academic success [

26,

29]. The cumulative effect of these stressors often leads to high attrition rates, as many students drop out due to their inability to cope. Deferral rates also increase, with students pausing their studies to manage overwhelming challenges. Additionally, those who continue their studies may experience poor performance, evidenced by low grades, high failure rates, and delayed course completion [

33]. Mental health issues such as anxiety, depression, attention deficits, and behavioral problems further exacerbate these outcomes, creating a cycle of declining academic achievement and well-being [

34].

2.5. Stress Coping

Stress management strategies for students in built environment (BE) disciplines must address the unique pressures they face, including tight project deadlines, intensive fieldwork, and the technical demands of design and construction management. Effective coping methods, both individual and social, can play a pivotal role in maintaining students’ mental and physical health.

Individual strategies focus on practices students can integrate into their daily routines. These include time management and prioritisation through tools like Gantt charts or software such as Trello (version 2023.12.1) and Asana (version 2023.11.5), enabling students to break down complex tasks into manageable steps [

35]. Incorporating physical activities (walking, cycling, and climbing stairs) when attending university can alleviate physical strain [

36]. Relaxation techniques like mindfulness, meditation, and yoga have also been shown to improve focus and reduce anxiety, particularly during high-pressure assessments [

37].

Social coping strategies emphasise the importance of seeking support from peers, mentors, and professional networks. Peer collaboration during group projects allows students to share workloads, gain fresh perspectives, and foster a sense of community, helping to mitigate stress [

38]. Open communication with faculty and industry mentors can provide valuable guidance on managing academic and workplace challenges [

39]. Additionally, accessing university counselling services can help students navigate stress-related mental health issues, though the cultural stigma around seeking help in the BE field must be addressed to encourage the greater utilisation of these resources [

40].

Conversely, the reliance on negative coping strategies such as denial, venting, behavioural disengagement, or substance use can significantly worsen students’ health and well-being. These maladaptive behaviours not only fail to address underlying stressors but may also exacerbate mental health challenges [

29]. Understanding the causes of these maladaptive strategies and developing prevention approaches is crucial for improving mental health outcomes. According to research conducted by Peter et al. [

41] and Ashipala and Albanus [

42], university students often face significant stress due to academic demands, leading to maladaptive coping strategies such as avoidance and substance abuse. Promoting adaptive strategies tailored to the specific demands of BE programs can help students manage stress more effectively, improve resilience, and enhance their overall well-being.

In summary, existing research highlights a complex interplay between academic and work-related stressors faced by students managing both study and employment. These stressors adversely affect their health and well-being, which subsequently influence academic performance and increase the risk of attrition. While positive coping strategies can mitigate these negative effects, the reliance on negative coping mechanisms can exacerbate them.

3. Research Method

3.1. Research Design

The study adopted a positivistic approach, utilising an online questionnaire survey to collect primary data from students enrolled in built environment programs, such as architecture, construction management, civil engineering, property management, and planning. The questionnaire comprised seven sections, as outlined in

Table 1. The first section collected respondents’ socio-demographic and course information. The second examined academic stressors; the third explored work-related stressors; the fourth focused on physical health; the fifth assessed and evaluated mental well-being; the sixth stress-coping strategies; and the final section measured academic outcomes. Except for demographic details, responses were recorded on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5. The survey questions were drawn from similar previous studies by Kamardeen and Sunindijo [

29] and Sunindijo and Kamardeen [

43], which were conducted in the context of graduate construction students. Hence, the reliability and validity of the questionnaire have already been tested and validated.

3.2. Data Collection

An online questionnaire survey was administered over a study semester from July to October 2024, targeting undergraduate students enrolled in built environment programs at Australian universities. A random sampling approach was adopted in which the schools offering BE programs were formally approached to distribute the survey invitation to all their students. A total of 379 students completed the survey out of their own interest in the subject matter. Of 379 responses received, 253 were complete and deemed suitable for analysis. As per Louangrath [

44], the recommended sample size for social science research using Likert scale responses is between 30 and 200, and the usable responses in this study exceeded this threshold.

Table 2 provides an overview of the socio-demographic and course details of the survey participants. About 75% of participants are under 24 years old, likely working in cadet, intern, or junior roles, while older students often juggle full-time jobs and family responsibilities. Female participation was higher, indicating a positive trend toward increased female enrolment in built environment programs, potentially boosting future industry representation. Most respondents are domestic students, with international students reflecting typical enrolment proportions. Around half are in their second or third year, while first-year and final-year students each make up about 25% of the sample, ensuring balanced representation across academic years. Half of the students take four subjects per semester, one-third take three, and the rest fewer. Similarly, most submit three to four assignments per subject, indicating a full academic load. Most follow face-to-face or hybrid learning modes. Students’ work hours vary, with similar proportions working up to 20, 20–30, or 30–40 h weekly. A few work over 40 h, likely studying part-time and taking fewer subjects. Two-thirds rely on study loans for tuition fees, while a similar number earn to cover living expenses. A smaller group (15%) pays both tuition and living expenses, likely balancing full-time work with studies.

3.3. Analysis Techniques

The 253 usable responses were first checked for missing values, which revealed random gaps in some variables. To prevent bias, the expectation maximisation (EM) method was used for data imputation. According to Kang [

45], EM and multiple imputation are among the best techniques for handling missing data. EM was selected for this study due to its direct availability in SPSS and ease of implementation. A combination of statistical techniques was applied to analyse the data to achieve the study aims.

The central tendencies of the data related to well-being, health, and academic performance were assessed using descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation). Then, one-sample t-tests were used to compare the central tendency of the sample with a hypothesised mean value of the population.

The survey used 60 measurement items/variables to assess academic stressors, work stressors, coping methods, health, well-being, and academic outcomes. Factor analysis was performed to identify a few components/constructs representing these measured items/variables. It also helped test the internal validity and reliability of the measurement items and scales used for measuring these constructs.

A path analysis was conducted to examine the causal relationships. Initially, correlation analyses were performed to identify constructs strongly associated with well-being, health, and academic outcomes. To enhance the fit of the resulting causality model, only constructs with statistically significant and strong correlations within the subset were included. As the validity of these constructs was confirmed through factor analysis, their cumulative mean scores were utilised in the subsequent path analysis.

4. Findings

This section presents the results of the data analysis, organised under relevant subheadings for clarity and focus.

4.1. Well-Being of BE Students

The well-being of BE students was evaluated using the DASS-8 scale [

46], which comprises eight indicators: two for stress, three for anxiety, and three for depression. The scale also provides guidelines for categorising the severity of the symptoms based on an arithmetic summation of the scores. To align with the five-point scale used in this study, rather than the original four-point scale (0–3), the severity intervals were recalibrated. The revised severity categories are as follows:

- 1.

Stress: Normal (1–3), Moderate (4–6), and Severe (7–10);

- 2.

Anxiety: Normal (1–5), Moderate (6–10), and Severe (11–15);

- 3.

Depression: Normal (1–5), Moderate (6–10), and Severe (11–15).

Table 3 illustrates the one-sample

t-test results that examine the intensity of well-being symptoms experienced by BE students in Australia. The one-sample

t-test enables a comparison of the sample mean value with a hypothesised population mean value. If the

p-value is greater than 0.05, there is no statistically significant difference between the test value and the population mean. The findings reveal that these students face severe stress, along with moderate levels of anxiety and depression, because of managing the dual demands of work and study.

4.2. Health of BE Students

Table 4 summarises the results of a one-sample

t-test conducted on the descriptive statistics of health symptoms reported by BE students. The test was based on a hypothesised population mean of 3, representing the midpoint of the Likert scale used in the survey. For most symptoms, the

p-values were below 0.05, indicating a statistically significant difference between the sample mean and the hypothesised population mean, except for two symptoms: headache and back pain. This suggests that the sample means can reliably infer the population mean for these health symptoms.

The findings reveal that BE students frequently experience four health issues due to the stress of balancing work and study:

- 1.

Feeling tired or having low energy;

- 2.

Trouble sleeping;

- 3.

Headache;

- 4.

Back pain.

The first two symptoms are associated with burnout, while the latter two are linked to chronic stress [

30,

32].

4.3. Academic Outcomes of BE Students

Table 5 outlines the results of a one-sample

t-test conducted on the descriptive statistics of academic outcomes reported by BE students. The test was based on a hypothesised population mean of 3, corresponding to the midpoint of the Likert scale used in the survey. For three of the four outcomes, the

p-values were less than 0.05, indicating a statistically significant difference between the sample mean and the hypothesised population mean. However, the fourth outcome, reduced attendance at scheduled learning activities, yielded a

p-value greater than 0.05, suggesting that the population mean exceeds the hypothesised value. These results indicate that the sample means can reliably infer the population mean for these academic outcomes. The findings highlight that BE students’ academic performance and university attendance are often negatively impacted by the dual pressures of work and study. Additionally, this challenge moderately influences their intention to defer or discontinue their studies.

4.4. Factor Analysis and Construct Formulation

The survey evaluated 60 items related to concepts such as academic stressors, work stressors, coping strategies, health, well-being, and academic outcomes. Factor analysis was conducted separately to identify key components or constructs representing these items. While detailed factor analysis results are omitted due to space constraints, the final outcomes are summarised in

Table 6. The KMO values of greater than 60 and the

p-values < 0.001 for Bartlett’s test for each section confirmed the internal validity and reliability of the scales and data for factor analysis:

- 1.

Thirteen out of fifteen academic stressors loaded onto four components, which are labelled as learning challenges, performance anxiety, group work challenges and academic demand;

- 2.

Fifteen work stressors loaded onto three components, namely, poor workplace support, work–study conflict, and career uncertainty;

- 3.

Eight out of ten coping methods loaded onto two components, which are labelled adaptive coping and maladaptive coping;

- 4.

Eight diseases that represented health loaded onto one component; similarly, eight items that represented well-being loaded onto a single component; and four variables represented academic outcomes loaded onto one component.

In the subsequent analysis, aggregated means of these scales were calculated and utilised for the constructs.

4.5. Path Analysis

First, correlation analyses were performed to identify constructs that have statistically significant strong correlations with students’ health, well-being, and academic outcomes.

Table 7 presents the results. Correlation coefficients can be interpreted to indicate the strength of relationships between variables. According to Mukaka [

47], coefficients ranging from 0.90 to 1.00 (or −0.90 to −1.00) reflect a very strong positive or negative correlation, while values between 0.70 and 0.90 (or −0.70 to −0.90) indicate a strong correlation. Moderate correlations are represented by coefficients from 0.50 to 0.70 (or −0.50 to −0.70), and weak correlations fall within the range of 0.30 to 0.50 (or −0.30 to −0.50). Finally, coefficients between 0.00 and 0.30 (or −0.00 to −0.30) signify negligible correlation. Accordingly, the following three constructs that have negligible correlations were removed from the path analysis:

- 1.

Groupwork challenges;

- 2.

Poor workplace support;

- 3.

Adaptive coping.

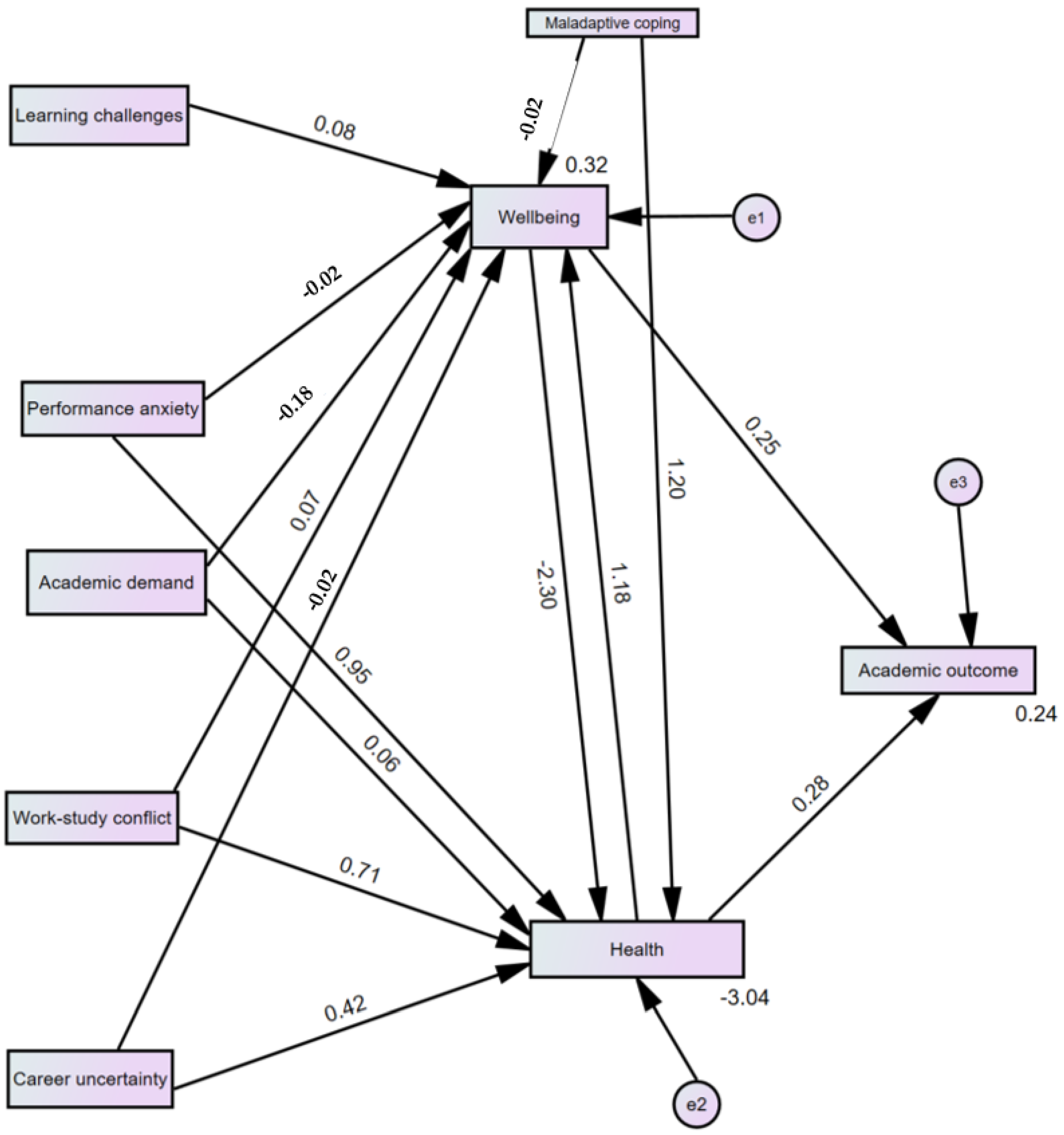

A structural path analysis was then performed to investigate regression relationships. Using IBM AMOS, a hypothesised structural model was created and iteratively refined with survey data to achieve optimal fit. Model fitness was improved progressively by incorporating modification indices provided by AMOS. The final model, presented in

Figure 1, displays regression weights for the paths and squared multiple correlations (R

2). The model achieved excellent fit indices: CFI = 0.914, TLI = 1.039, NFI = 0.911, and RMSEA = 0.220. As per Schumacker and Lomax [

48], CFI, TLI, and NFI values near 1.000, alongside an RMSEA value close to 0, indicate the best fit. Hence, the developed path model fits the data very well.

The model shows several statistically significant direct causal pathways. Academic performance anxiety and work–study conflict are the strongest predictors of poor health symptoms, followed by career uncertainty. There are strong bi-directional casualties between health symptoms and well-being. Maladaptive coping has a strong causal connection with health symptoms. Well-being and health conditions have a similar bearing in predicting negative academic outcomes.

5. Discussion

The findings of this study align with the previous research, which highlights the negative impact of work–study conflict on students’ well-being and academic performance. Studies by Lingard et al. [

11] and Loosemore et al. [

15] identified burnout, anxiety, and depression as prevalent issues among students balancing academic and work responsibilities. Similarly, the current study highlights that BE students experience severe stress and moderate levels of anxiety and depression, which align with the broader literature on student mental health challenges in high-pressure academic programs. These mental health issues often stem from the combined pressures of meeting academic deadlines, maintaining high-performance expectations, and managing demanding work schedules. Such stressors can lead to physical health symptoms like fatigue and sleep disturbances, which further exacerbate students’ mental health struggles. Together, these findings reinforce the critical need for holistic approaches to support student well-being, addressing both the structural factors contributing to work–study conflict and the psychological challenges it creates.

In addition, this study makes several new contributions to the field. First, it uses a causal framework to explore the direct and indirect relationships between academic and work stressors, coping mechanisms, and their impact on health, well-being, and academic outcomes. The path analysis reveals that performance anxiety and work–study conflict are not only significant stressors but also key predictors of adverse health symptoms, a finding not extensively explored in previous studies. Another novel contribution is the identification of maladaptive coping strategies as a critical factor exacerbating the negative impacts of work–study conflict. While earlier studies have recognised the importance of coping mechanisms [

35,

39,

40], this research underscores the specific detrimental effects of maladaptive coping, such as emotional venting and behavioural disengagement, on students’ health and academic performance. Further, the study highlights the cyclical nature of stress, health, and academic challenges. Poor health symptoms such as fatigue and sleep disturbances significantly affect students’ mental well-being, which, in turn, impacts their academic performance, creating a feedback loop that perpetuates these issues. This dynamic interaction between health, well-being, and academic outcomes adds a new dimension to understanding the challenges faced by BE students.

These findings emphasise the importance of targeted interventions that address both the immediate stressors and the coping mechanisms employed by students. This study contributes valuable insights to the existing body of literature and provides a robust foundation for developing comprehensive support systems for BE students managing dual academic and work responsibilities.

The findings of this study, while focused on students in built environment programs in Australian universities, offer insights broadly applicable to other academic disciplines and contexts. Many of the challenges identified, such as work–study conflict, performance anxiety, and the use of maladaptive coping strategies, are not unique to BE students but are commonly reported among students in high-demand fields like healthcare and medicine [

9]. Additionally, the study’s results align with international research, suggesting that students in other countries face similar stressors, despite potential cultural and systemic differences in higher education [

13,

14]. These observations support the external validity of the findings, indicating that the patterns and relationships identified in this study could be generalised to students across various disciplines and geographical settings, particularly in contexts with comparable academic and work environments.

6. Conclusions

This study investigated the impact of work–study conflict on the well-being, health, and academic outcomes of BE students in Australian universities. The findings reveal that BE students face severe stress, moderate anxiety, and depression as they manage academic and work demands. Physical health issues, including fatigue, trouble sleeping, and stress-related symptoms, were prevalent and strongly linked to burnout and chronic stress. Academic outcomes were similarly affected, with students reporting reduced performance, lower attendance, and considerations to defer or discontinue their studies. The path analysis highlighted several key predictors of these adverse outcomes. Performance anxiety and work–study conflict were identified as the strongest contributors to poor health, while maladaptive coping strategies exacerbated the negative effects on well-being and academic outcomes. Furthermore, the bi-directional relationship between health symptoms and well-being underscores the cyclical nature of stress, which perpetuates challenges in students’ academic and personal lives.

These findings have significant practical implications. Universities should prioritise interventions that address both academic and workplace stressors. Flexible learning structures, targeted mental health services, and industry partnerships can help students balance dual responsibilities. Additionally, promoting adaptive coping strategies, such as effective time management and mindfulness practices, may mitigate the adverse effects of work–study conflict. Workplaces employing BE students should also offer flexible schedules and align job roles with students’ capabilities to reduce career uncertainty and workload pressure.

Despite its contributions, this study has several limitations. The reliance on self-reported data may introduce biases, and the cross-sectional design restricts the ability to capture changes over time. Additionally, the focus on Australian universities may limit the generalisability of findings to other regions and cultural contexts. However, the challenges faced by BE students in this study align with findings from similar research conducted in other disciplines and countries, suggesting a broader applicability of the results. These insights provide a foundation for comparing the experiences of BE students in diverse educational systems and cultural settings, shedding light on universal patterns and context-specific differences.

Future research could adopt longitudinal designs to track stress patterns over time and expand the scope to other disciplines or countries. Investigating the efficacy of specific institutional and workplace interventions would also provide actionable insights for addressing these challenges. By highlighting the complex interplay of work–study conflict, health, and academic outcomes, this study lays the groundwork for developing comprehensive strategies to support the success and well-being of BE students, with the potential to inform similar efforts in other academic disciplines and regions. As the next-generation workforce, these students are pivotal to the future of the construction industry, and failure to address their challenges may have long-term repercussions on industry sustainability and productivity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S. and I.K.; methodology, M.S. and I.K.; software, M.S. and I.K.; validation, M.S. and I.K.; formal analysis, M.S. and I.K.; investigation, M.S. and I.K.; resources, M.S. and I.K.; data curation, M.S. and I.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S. and I.K.; writing—review and editing, M.S. and I.K.; visualization, M.S. and I.K.; supervision, I.K.; project administration, I.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research received no funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research has been granted approval by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Western Sydney University (Approval date: 21 May 2024; Approval No: H16007).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Stallman, H.M. Psychological Distress in University Students: A Comparison with General Population Data. Aust. Psychol. 2010, 45, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, K.J.; Menon, K.R.; Thattil, A. Academic Stress and Its Sources among University Students. Biomed. Pharmacol. J. 2018, 11, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zegwaard, K.E.; Ferns, S.J.; Rowe, A.D. Contemporary Insights into the Practice of Work-Integrated Learning in Australia. In Advances in Research, Theory and Practice in Work-Integrated Learning; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, D. Work-Integrated Learning: Opportunities and Challenges in Australia. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2024, 43, 767–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLennan, B.; Keating, S. Work-Integrated Learning (WIL) in Australian Universities: The Challenges of Mainstreaming WIL. In Proceedings of the ALTC NAGCAS National Synopsium, Melbourne, Australia, 30 June–2 July 2008; pp. 2–14. [Google Scholar]

- Bean, M.; Dawkins, P. University-Industry Collaboration in Teaching and Learning; Australian Government, Department of Education, Skills and Employment: Canberra, Australian, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cvetkovski, S.; Jorm, A.F.; Mackinnon, A.J. Student Psychological Distress and Degree Dropout or Completion: A Discrete-Time, Competing Risks Survival Analysis. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2018, 37, 484–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajac, T.; Perales, F.; Tomaszewski, W.; Xiang, N.; Zubrick, S.R. Student Mental Health and Dropout from Higher Education: An Analysis of Australian Administrative Data. High. Educ. 2024, 87, 325–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, I.W.; Carroll, D.R. Factors Influencing Dropout and Academic Performance: An Australian Higher Education Equity Perspective. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2020, 42, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingard, H. Conflict between Paid Work and Study: Does It Impact upon Students’ Burnout and Satisfaction with University Life? J. Educ. Built Environ. 2007, 2, 90–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingard, H.; Brown, K.; Bradley, L.; Bailey, C.; Townsend, K. Improving Employees’ Work-Life Balance in the Construction Industry: Project Alliance Case Study. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2007, 133, 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, P.; Loosemore, M. Burnout of Undergraduate Construction Management Students in Australia. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2014, 32, 1066–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y. Burnout and Its Relationship with Architecture Students’ Job Design in Hong Kong. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bakare, J.; Omeje, H.O.; Yisa, M.A.; Orji, C.T.; Onyechi, K.C.N.; Eseadi, C.; Nwajiuba, C.A.; Anyaegbunam, E.N. Investigation of Burnout Syndrome among Electrical and Building Technology Undergraduate Students in Nigeria. Medicine 2019, 98, e17581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loosemore, M.; Lim, B.; Ilivski, M. Depression in Australian Undergraduate Construction Management, Civil Engineering, and Architecture Students: Prevalence, Symptoms, and Support. J. Civ. Eng. Educ. 2020, 14, 04020003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groen, C.; Simmons, D.R.; Turner, M. Developing Resilience: Experiencing and Managing Stress in a U.S. Undergraduate Construction Program. J. Prof. Issues Eng. Educ. Pract. 2019, 145, 04019002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.; Scott-Young, C.; Holdsworth, S. Resilience and Well-Being: A Multi-Country Exploration of Construction Management Students. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2021, 21, 858–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maji, S.; Chaturmohta, A.; Deevela, D.; Sinha, S.; Tarsolia, S.; Barsaiya, A. Mental Health Consequences of Academic Stress, Amotivation, and Coaching Experience: A Study of India’s Top Engineering Undergraduates. Psychol. Sch. 2024, 61, 3540–3566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osoaku, F.; Afolabi, A.O.; Ochiba, D.; Oleah, C. Education Stress Factors among Construction Students in Tertiary Institutions. AIP Conf. Proc. 2022, 2437, 020139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorshid, S.; Song, S. Work in Progress: Assessing the Need for Mental Health Curricula for Civil, Architecture, and Construction Engineering. In Proceedings of the 2023 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition, Baltimore, MD, USA, 25–28 June 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojtahedi, M.; Kamardeen, I.; Rahmat, H.; Ryan, C. Flipped Classroom Model for Enhancing Student Learning in Construction Education. J. Civ. Eng. Educ. 2020, 146, 05019001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, W.; Jing, W. Evaluation of Flipped Classroom Teaching Quality for Civil Engineering Courses. Arch. Civ. Eng. 2024, 70, 579–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Córdova Olivera, P.; Gasser Gordillo, P.; Naranjo Mejía, H.; La Fuente Taborga, I.; Grajeda Chacón, A.; Sanjinés Unzueta, A. Academic Stress as a Predictor of Mental Health in University Students. Cogent Educ. 2023, 10, 2232686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurelius, K.; Söderberg, M.; Wahlström, V.; Waern, M.; LaMontagne, A.D.; Åberg, M. Perceptions of Mental Health, Suicide, and Working Conditions in the Construction Industry: A Qualitative Study. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0307433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padala, S.S.; Maheswari, J.U.; Hirani, H. Identification and Classification of Change Causes and Effects in Construction Projects. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2022, 22, 2788–2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, K.; Adebowale, O.J.; Dodo, M.; Zailani, B.M.; Lukman, O.; Kajimo-Shakantu, K. Challenges and Coping Strategies of Built Environment Students during Students Industrial Work Experience Scheme (SIWES): Perspective from Nigeria. Int. J. Constr. Educ. Res. 2024, 20, 157–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardani, M.; Bradford, D.R.R.; Russell, K.; Allan, S.; Beattie, L.; Ellis, J.G.; Akram, U. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Poor Sleep, Insomnia Symptoms, and Stress in Undergraduate Students. Sleep Med. Rev. 2021, 61, 101565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mofatteh, M. Risk Factors Associated with Stress, Anxiety, and Depression among University Undergraduate Students. AIMS Public Health 2021, 8, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamardeen, I.; Sunindijo, R.Y. Stressors Impacting the Performance of Graduate Construction Students: Comparison of Domestic and International Students. J. Prof. Issues Eng. Educ. Pract. 2018, 144, 04018011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, S.; Lascelles, K.; Hawton, K. Suicide, Self-Harm, and Suicide Ideation in Nurses and Midwives: A Systematic Review of Prevalence, Contributory Factors, and Interventions. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 331, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerekes, N.; Zouini, B.; Tingberg, S.; Erlandsson, S. Psychological Distress, Somatic Complaints, and Their Relation to Negative Psychosocial Factors in a Sample of Swedish High School Students. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 669958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zisook, S.; Doran, N.; Mortali, M.; Hoffman, L.; Downs, N.; Davidson, J.; Fergerson, B.; Rubanovich, C.K.; Shapiro, D.; Tai-Seale, M.; et al. Relationship between Burnout and Major Depressive Disorder in Health Professionals: A HEAR Report. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 312, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellas, A.; Ihantola, P.; Petersen, A.; Ajanovski, V.V.; Gutica, M.; Hynninen, T.; Knutas, A.; Leinonen, J.; Messom, C.; Liao, S.N. Predicting Academic Performance: A Systematic Literature Review. In Proceedings of the Companion of the 23rd Annual ACM Conference on Innovation and Technology in Computer Science Education, Larnaca, Cyprus, 2–4 July 2018; pp. 175–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, T.; Liu, X.; Takayanagi, S.; Matsushita, T.; Kishimoto, H. Association between Mental Health and Academic Performance among University Undergraduates: The Interacting Role of Lifestyle Behaviors. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2022, 32, e1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillence, E.; Dawson, J.A.; McKellar, K.; Neave, N. How Do Students Use Digital Technology to Manage Their University-Based Data: Strategies, Accumulation Difficulties, and Feelings of Overload? Behav. Inf. Technol. 2023, 42, 2442–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadegaripour, M.; Hadadnezhad, M.; Abbasi, A.; Eftekhari, F.; Samani, A. The Effect of Adjusting Screen Height and Keyboard Placement on Neck and Back Discomfort, Posture, and Muscle Activities during Laptop Work. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2021, 37, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vella, E.; McIver, S. Reducing Stress and Burnout in the Public-Sector Work Environment: A Mindfulness Meditation Pilot Study. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2019, 30, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oddone Paolucci, E.; Jacobsen, M.; Nowell, L.; Freeman, G.; Lorenzetti, L.; Clancy, T.; Lorenzetti, D.L. An Exploration of Graduate Student Peer Mentorship, Social Connectedness, and Well-Being across Four Disciplines of Study. Stud. Grad. Postdoc. Educ. 2021, 12, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardie, M.; Love, P. The Role of Industry-Based Learning in a Construction Management Program. Australas. J. Constr. Econ. Build. Conf. Ser. 2012, 1, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tom, A.A. Examining the Barriers to Seeking Counseling and Mental Health Services on College Campuses in the Asian American Student Population. Ph.D. Thesis, Azusa Pacific University, Azusa, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Peter, J.O.; Aloka, M.O.; Ooko, T.K.; Onyango, R.O. Maladaptive Coping Mechanisms to Stress among University Students from an Integrative Review. In Student Stress in Higher Education; Advances in Higher Education and Professional Development; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashipala, D.; Albanus, F. Maladaptive Coping Mechanisms. In Mental Health Crisis in Higher Education; Advances in Higher Education and Professional Development; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2023; pp. 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunindijo, R.Y.; Kamardeen, I. Psychological Challenges Confronting Graduate Construction Students in Australia. Int. J. Constr. Educ. Res. 2020, 16, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louangrath, P. Minimum Sample Size Method Based on Survey Scales. Int. J. Res. Methodol. Soc. Sci. 2017, 3, 44–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, H. The Prevention and Handling of Missing Data. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2013, 64, 402–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.M.; Hori, H.; Kim, Y.; Kunugi, H. The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale 8-Items Expresses Robust Psychometric Properties as an Ideal Shorter Version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale 21 among Healthy Respondents from Three Continents. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 799769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukaka, M. A Guide to Appropriate Use of Correlation Coefficient in Medical Research. Malawi Med. J. 2012, 24, 69–71. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacker, R.E.; Lomax, R.G. A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).