Enhancing Pedestrian Satisfaction: A Quantitative Study of Visual Perception Elements

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

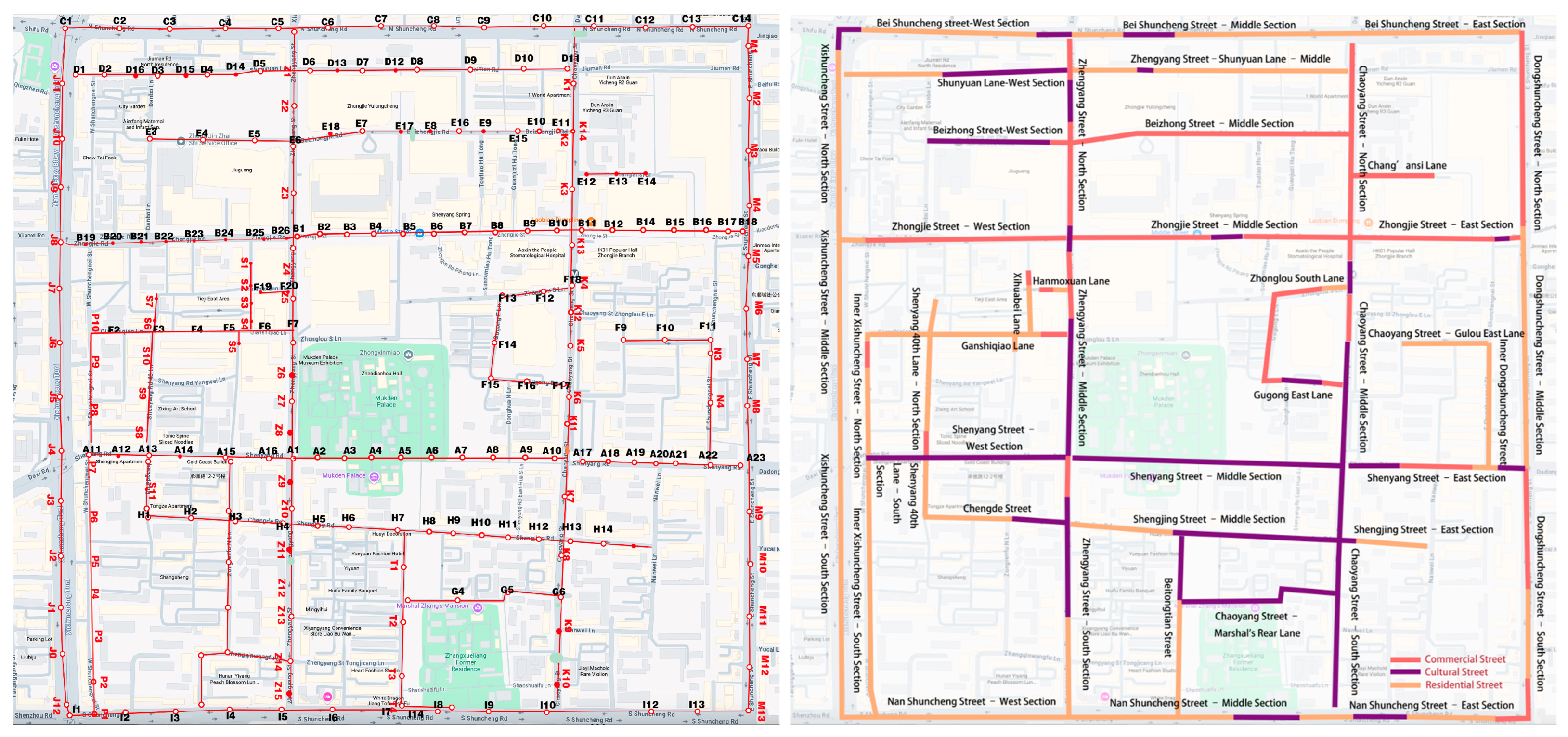

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Street Visual Perception Data Collection and Processing

2.3. Pedestrian Satisfaction Data Collection and Processing

3. Results

3.1. Pedestrian Satisfaction and Visual-Perception Factors

3.1.1. Pedestrian Satisfaction Evaluation Results

3.1.2. Visual-Perception Factors

3.2. Correlation and Regression Analyses of Visual Perception Elements and Pedestrian Satisfaction

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- Ensure the continuity of the street interface. For example, elements such as street greenery and shop facades should visually emphasize spatial coherence and unity, which helps enhance the city’s recognizability and image.

- (2)

- Control street scale. On one hand, the spatial proportions of historic streets should be preserved, maintaining an appropriate height-to-width ratio; on the other hand, designated leisure areas can be incorporated within wider sidewalks to increase street attractiveness.

- (3)

- Preserve and restore historic buildings. By maintaining a street space characterized by low building density and high greenery levels, the overall environmental quality of the heritage area can be improved.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carmona, M. Public Places Urban Spaces: The Dimensions of Urban Design; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M.; Ram, Y. Measuring the relationship between tourism and walkability? Walk Score and English tourist attractions. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 223–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, M.; Ujang, N. Tourist’expectation and satisfaction towards pedestrian networks in the historical district of Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Asian Geogr. 2016, 33, 35–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skotis, A.; Livas, C. A data-driven analysis of experience in urban historic districts. Ann. Tour. Res. Empir. Insights 2022, 3, 100052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Chen, J.; Li, J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Yu, F. Unraveling the renewal priority of urban heritage communities via macro-micro dimensional assessment-A case study of Nanjing City, China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 124, 106317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, K. Good City Form; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Wiklund, J. Vägen Till Offentliga Rum. en Fallstudie om Barcelonas Superkvarter ur ett Vistelseperspektiv; GUPEA: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gehl, J. Cities for People; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Nabipour, M.; Rosenberg, M.W.; Nasseri, S.H. The built environment, networks design, and safety features: An analysis of pedestrian commuting behavior in intermediate-sized cities. Transp. Policy 2022, 129, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stensel, D.J.; Hardman, A.E.; Gill, J.M. Physical Activity and Health: The Evidence Explained; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gálvez-Pérez, D.; Guirao, B.; Ortuño, A.; Picado-Santos, L. The influence of built environment factors on elderly pedestrian road safety in cities: The experience of Madrid. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerike, R.; Koszowski, C.; Schröter, B.; Buehler, R.; Schepers, P.; Weber, J.; Wittwer, R.; Jones, P. Built environment determinants of pedestrian activities and their consideration in urban street design. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F. Urban morphology and citizens’ life. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Koohsari, M.J.; Oka, K.; Owen, N.; Sugiyama, T. Natural movement: A space syntax theory linking urban form and function with walking for transport. Health Place 2019, 58, 102072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biljecki, F.; Ito, K. Street view imagery in urban analytics and GIS: A review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 215, 104217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollander, J.B.; Sussman, A.; Lowitt, P.; Angus, N.; Situ, M. Analyzing walkability through biometrics: Insights into sustainable transportation through the use of eye-tracking emulation software. J. Phys. Act. Health 2020, 17, 1153–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sussman, A.; Hollander, J. Cognitive Architecture: Designing for How We Respond to the Built Environment; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Ujang, N. An analysis of pedestrian preferences for wayfinding signage in urban settings: Evidence from Nanning, China. Buildings 2024, 14, 2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Feng, Z.; Pearce, J. Neighbourhood greenspace quantity, quality and socioeconomic inequalities in mental health. Cities 2022, 129, 103815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Hang, T.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Cao, L. Integrating restorative perception into urban street planning: A framework using street view images, deep learning, and space syntax. Cities 2024, 147, 104791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; He, S.; Cai, Y.; Wang, M.; Su, S. Social inequalities in neighborhood visual walkability: Using street view imagery and deep learning technologies to facilitate healthy city planning. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 50, 101605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Cruz, N.F.; Rode, P.; McQuarrie, M. New urban governance: A review of current themes and future priorities. J. Urban Aff. 2019, 41, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, R.H.; Clemente, O.; Neckerman, K.M.; Purciel-Hill, M.; Quinn, J.W.; Rundle, A. Measuring Urban Design: Metrics for Livable Places; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; Volume 200. [Google Scholar]

- Aziz, H.A.; Nagle, N.N.; Morton, A.M.; Hilliard, M.R.; White, D.A.; Stewart, R.N. Exploring the impact of walk–bike infrastructure, safety perception, and built-environment on active transportation mode choice: A random parameter model using New York City commuter data. Transportation 2018, 45, 1207–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, J.; Lättman, K.; Van der Vlugt, A.-L.; Welsch, J.; Otsuka, N. Determinants and effects of perceived walkability: A literature review, conceptual model and research agenda. Transp. Rev. 2023, 43, 303–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, R.; Cervero, R. Travel and the built environment: A meta-analysis. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2010, 76, 265–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papas, M.A.; Alberg, A.J.; Ewing, R.; Helzlsouer, K.J.; Gary, T.L.; Klassen, A.C. The built environment and obesity. Epidemiol. Rev. 2007, 29, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovasi, G.S.; Schwartz-Soicher, O.; Quinn, J.W.; Berger, D.K.; Neckerman, K.M.; Jaslow, R.; Lee, K.K.; Rundle, A. Neighborhood safety and green space as predictors of obesity among preschool children from low-income families in New York City. Prev. Med. 2013, 57, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saelens, B.E.; Handy, S.L. Built environment correlates of walking: A review. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2008, 40, S550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, K.; Abe, H.; Otsuka, N.; Yasufuku, K.; Takahashi, A. A comprehensive evaluation of walkability in historical cities: The case of Xi’an and Kyoto. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handy, S.L.; Boarnet, M.G.; Ewing, R.; Killingsworth, R.E. How the built environment affects physical activity: Views from urban planning. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2002, 23, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saelens, B.E.; Sallis, J.F.; Frank, L.D. Environmental correlates of walking and cycling: Findings from the transportation, urban design, and planning literatures. Ann. Behav. Med. 2003, 25, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Zhong, L.; Wu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z. Impacts of micro-scale built environment features on tourists’ walking behaviors in historic streets: Insights from Wudaoying Hutong, China. Buildings 2022, 12, 2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutts, B.B.; Darby, K.J.; Boone, C.G.; Brewis, A. City structure, obesity, and environmental justice: An integrated analysis of physical and social barriers to walkable streets and park access. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 69, 1314–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, T.; Liang, X.; Biljecki, F.; Tu, W.; Cao, J.; Li, X.; Yi, S. Quantifying seasonal bias in street view imagery for urban form assessment: A global analysis of 40 cities. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2025, 120, 102302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, R.; Handy, S. Measuring the unmeasurable: Urban design qualities related to walkability. J. Urban Des. 2009, 14, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavizzo-Mourey, R.; McGinnis, J.M. Making the case for active living communities. Am. J. Public Health 2003, 93, 1386–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, C. Health and Community Design: The Impact of the Built Environment on Physical Activity. Can. J. Urban Res. 2004, 13, 390. [Google Scholar]

- Northridge, M.E.; Sclar, E.D.; Biswas, P. Sorting out the connections between the built environment and health: A conceptual framework for navigating pathways and planning healthy cities. J. Urban Health 2003, 80, 556–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoehner, C.M.; Brennan, L.K.; Brownson, R.C.; Handy, S.L.; Killingsworth, R. Opportunities for integrating public health and urban planning approaches to promote active community environments. Am. J. Health Promot. 2003, 18, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buras, N.H. The Art of Classic Planning: Building Beautiful and Enduring Communities; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, H.Y.; Zegras, C.; Palencia Arreola, D.H. “Digitalizing walkability”: Comparing smartphone-based and web-based approaches to measuring neighborhood walkability in Singapore. J. Urban Technol. 2019, 26, 3–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, Y. Study of street space perception in Shanghai based on semantic differential method. J. Tongji Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2011, 39, 1000–1006. [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, J.Y.; Jo, H.I. Effects of audio-visual interactions on soundscape and landscape perception and their influence on satisfaction with the urban environment. Build. Environ. 2020, 169, 106544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouratidis, K. Urban planning and quality of life: A review of pathways linking the built environment to subjective well-being. Cities 2021, 115, 103229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Ji, X.; Gao, W.; Zhou, F.; Yu, Y.; Meng, Y.; Yang, M.; Lin, J.; Lyu, M. The relation between green visual index and visual comfort in Qingdao coastal streets. Buildings 2023, 13, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Feng, Y.; Sheng, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, K. Evaluation of pedestrian-perceived comfort on urban streets using multi-source data: A case study in Nanjing, China. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2025, 14, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Ji, X.; Lyu, M.; Fu, Y.; Gao, W. Evaluation and diagnosis for the pedestrian quality of service in urban riverfront streets. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 452, 142090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinnamon, J.; Jahiu, L. 360-degree video for virtual place-based research: A review and research agenda. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2023, 106, 102044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Huang, X.; Wang, S.; He, Y.; Li, X.; Hohl, A.; Li, X.; Aly, M.; Lin, B. Toward a comprehensive understanding of eye-level urban greenness: A systematic review. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2023, 16, 4769–4789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Fei, T.; Kang, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, Z.; Wu, G. Estimating urban noise along road network from street view imagery. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2024, 38, 128–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Abraham, J.; Ceccato, V.; Duarte, F.; Gao, S.; Ljungqvist, L.; Zhang, F.; Näsman, P.; Ratti, C. Assessing differences in safety perceptions using GeoAI and survey across neighbourhoods in Stockholm, Sweden. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 236, 104768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehaffy, M.W.; Salingaros, N.A.; Lavdas, A.A. The “modern” campus: Case study in (Un) Sustainable urbanism. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Li, Q.; Ji, X.; Sun, D.; Meng, Y.; Yu, Y.; Lyu, M. Impact of streetscape built environment characteristics on human perceptions using street view imagery and deep learning: A case study of Changbai Island, Shenyang. Buildings 2025, 15, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, W.; Zhao, L. Research on correlation between spatial quality of urban streets and pedestrian walking characteristics in china based on street view big data. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2022, 148, 05022035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trop, T.; Shoshany Tavory, S.; Portnov, B.A. Factors affecting pedestrians’ perceptions of safety, comfort, and pleasantness induced by public space lighting: A systematic literature review. Environ. Behav. 2023, 55, 3–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Li, Z.; Xia, Q.; Peng, Y.; Cao, T.; Du, T.; Xing, Z. Walking in China’s Historical and Cultural Streets: The Factors Affecting Pedestrian Walking Behavior and Walking Experience. Land 2022, 11, 1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, M.A.; Kalam, A.; Al-Mamun, M. Unplanned urbanization and health risks of Dhaka City in Bangladesh: Uncovering the associations between urban environment and public health. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1269362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapoport, A.; Hawkes, R. The perception of urban complexity. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1970, 36, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, Y.-F. Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Zhang, C.; Li, W.; Ricard, R.; Meng, Q.; Zhang, W. Assessing street-level urban greenery using Google Street View and a modified green view index. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; He, D.; Gou, Z.; Wang, R.; Liu, Y.; Lu, Y. Association between street greenery and walking behavior in older adults in Hong Kong. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 51, 101747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Guo, J.; Ma, Z.; Zhao, K. Data-driven approach to assess street safety: Large-scale analysis of the microscopic design. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, C. Architectural allostatic overloading: Exploring a connection between architectural form and allostatic overloading. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, B.; Penn, A.; Hanson, J.; Grajewski, T.; Xu, J. Natural movement: Or, configuration and attraction in urban pedestrian movement. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 1993, 20, 29–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, B.; Geng, J.; Ke, S.; Pan, H. Analysis of spatial variation of street landscape greening and influencing factors: An example from Fuzhou city, China. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakamoto, S.; Kogure, M.; Hanibuchi, T.; Nakaya, N.; Hozawa, A.; Nakaya, T. Effects of greenery at different heights in neighbourhood streetscapes on leisure walking: A cross-sectional study using machine learning of streetscape images in Sendai City, Japan. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2023, 22, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Moudon, A.V. Objective versus subjective measures of the built environment, which are most effective in capturing associations with walking? Health Place 2010, 16, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, P.; Liu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, H.; Lu, Y.; Xue, C.Q. Eye-level street greenery and walking behaviors of older adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Lee, S. Verification of immersive virtual reality as a streetscape evaluation method in urban residential areas. Land 2023, 12, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-C.; Zhu, Y.; Papandreou, G.; Schroff, F.; Adam, H. Encoder-decoder with atrous separable convolution for semantic image segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 801–818. [Google Scholar]

- Long, J.; Shelhamer, E.; Darrell, T. Fully convolutional networks for semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 3431–3440. [Google Scholar]

- Cordts, M.; Omran, M.; Ramos, S.; Rehfeld, T.; Enzweiler, M.; Benenson, R.; Franke, U.; Roth, S.; Schiele, B. The cityscapes dataset for semantic urban scene understanding. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 3213–3223. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Shi, J.; Qi, X.; Wang, X.; Jia, J. Pyramid scene parsing network. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 2881–2890. [Google Scholar]

- Kido, D.; Fukuda, T.; Yabuki, N. Assessing future landscapes using enhanced mixed reality with semantic segmentation by deep learning. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2021, 48, 101281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromm, K.N.; Lang, I.-M.; Twardzik, E.E.; Antonakos, C.L.; Dubowitz, T.; Colabianchi, N. Virtual audits of the urban streetscape: Comparing the inter-rater reliability of GigaPan® to Google Street View. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2020, 19, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Wang, Z. Measuring visual enclosure for street walkability: Using machine learning algorithms and Google Street View imagery. Appl. Geogr. 2016, 76, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiferling, I.; Naik, N.; Ratti, C.; Proulx, R. Green streets–Quantifying and mapping urban trees with street-level imagery and computer vision. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 165, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Richards, D.; Lu, Y.; Song, X.; Zhuang, Y.; Zeng, W.; Zhong, T. Measuring daily accessed street greenery: A human-scale approach for informing better urban planning practices. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 191, 103434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Gong, J.; Sun, J.; Zhou, J.; Li, W.; Li, Y.; Liu, J.; Shen, S. Automatic sky view factor estimation from street view photographs—A big data approach. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Liu, L. How green are the streets? An analysis for central areas of Chinese cities using Tencent Street View. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, L.; Lu, J.; Li, W.; Li, Y. A fast approach for large-scale Sky View Factor estimation using street view images. Build. Environ. 2018, 135, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Long, Y. Measuring visual quality of street space and its temporal variation: Methodology and its application in the Hutong area in Beijing. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 191, 103436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ki, D.; Lee, S. Analyzing the effects of Green View Index of neighborhood streets on walking time using Google Street View and deep learning. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 205, 103920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, A.; Naik, N.; Parikh, D.; Raskar, R.; Hidalgo, C.A. Deep learning the city: Quantifying urban perception at a global scale. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; pp. 196–212. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y.; Liang, Z.; Yuan, Z.; Liu, P.; Bie, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, R.; Wang, J.; Guan, Q. A human-machine adversarial scoring framework for urban perception assessment using street-view images. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2019, 33, 2363–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lu, J.; Meng, Y.; Luo, Y.; Ren, J. Exploring Urban Spatial Quality Through Street View Imagery and Human Perception Analysis. Buildings 2025, 15, 3116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, M.; Meng, Y.; Gao, W.; Yu, Y.; Ji, X.; Li, Q.; Huang, G.; Sun, D. Measuring the perceptual features of coastal streets: A case study in Qingdao, China. Environ. Res. Commun. 2022, 4, 115002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Long, Y.; Zhai, W.; Ma, Y. Measuring quality of street space, its temporal variation and impact factors: An analysis based on massive street view pictures. New Archit 2016, 5, 110–115. [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport, A. The Meaning of the Built Environment: A Nonverbal Communication Approach; University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ewing, R.; Handy, S.; Brownson, R.C.; Clemente, O.; Winston, E. Identifying and measuring urban design qualities related to walkability. J. Phys. Act. Health 2006, 3, S223–S240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, T.M.; Wang, Z.; Vaartjes, I.; Karssenberg, D.; Ettema, D.; Helbich, M.; Timmermans, E.J.; Frank, L.D.; den Braver, N.R.; Wagtendonk, A.J. Development of an objectively measured walkability index for the Netherlands. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2022, 19, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shulin, S.; Zhonghua, G.; Leslie, H. How does enclosure influence environmental preferences? A cognitive study on urban public open spaces in Hong Kong. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2014, 13, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, F.; Silva, E.; Pereira, F.; Silva, C.; Sousa, E.; Freitas, E. The influence of noise emitted by vehicles on pedestrian crossing decision-making: A study in a virtual environment. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Han, M.; Rhee, K.; Bae, B. Identification of factors affecting pedestrian satisfaction toward land use and street type. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arar, M.; Kazaz, K. Assessing urban design factors for walkable areas: Evidence from Dubai. Front. Built Environ. 2025, 11, 1631826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, A. A city is not a tree. In Architectural Forum; Urban America Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Carmona, M. Place value: Place quality and its impact on health, social, economic and environmental outcomes. J. Urban Des. 2019, 24, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, M.; De Magalhães, C.; Hammond, L. Public Space: The Management Dimension; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Zhang, B.; Luo, T.; Liu, Y.; Portnov, B.A.; Trop, T.; Jiao, W.; Liu, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, Q. Evaluating street lighting quality in residential areas by combining remote sensing tools and a survey on pedestrians’ perceptions of safety and visual comfort. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-García, A.; Hurtado, A.; Aguilar-Luzón, M.C. Impact of public lighting on pedestrians’ perception of safety and well-being. Saf. Sci. 2015, 78, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Fang, X.; Ma, Y.; Xue, S.; Yin, S. Assessing effects of urban greenery on the regulation mechanism of microclimate and outdoor thermal comfort during winter in China’s cold region. Land 2022, 11, 1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimimoshaver, M.; Winkemann, P. A framework for assessing tall buildings’ impact on the city skyline: Aesthetic, visibility, and meaning dimensions. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2018, 73, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Lin, D.; Chen, Y.; Wu, J. Integrating Street View Images, Deep Learning, and sDNA for Evaluating University Campus Outdoor Public Spaces: A Focus on Restorative Benefits and Accessibility. Land 2025, 14, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metro-Roland, M.M. Tourists, Signs and the City: The Semiotics of Culture in an Urban Landscape; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.; Yu, Y.; Lyu, M.; Sun, D.; Dewancker, B.; Gao, W. Impact of physical features on visual walkability perception in urban commercial streets by using street-view images and deep learning. Buildings 2024, 15, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarova, I.; Gabsalikhova, L.; Sadygova, G.; Magdin, K. Ways to improve safety and environmental friendliness of the city’s transport system. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2020; p. 012072. [Google Scholar]

- Mohan, D.; Bangdiwala, S.I.; Villaveces, A. Urban street structure and traffic safety. J. Saf. Res. 2017, 62, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, C.; Allam, Z.; Chabaud, D.; Gall, C.; Pratlong, F. Introducing the “15-Minute City”: Sustainability, resilience and place identity in future post-pandemic cities. Smart Cities 2021, 4, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundling, C.; Jakobsson, M. How do urban walking environments impact pedestrians’ experience and psychological health? A systematic review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R. Factors affecting walkability of neighborhoods. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 216, 643–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zheng, M.; Zhang, T. Impact characteristics and interaction effects of built environment on street space quality in megacities: A case study of Xi’an, China. City Environ. Interact. 2025, 28, 100257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Park, S.; Lee, J.S. Meso-or micro-scale? Environmental factors influencing pedestrian satisfaction. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2014, 30, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann-Lunecke, M.G.; Mora, R.; Vejares, P. Perception of the built environment and walking in pericentral neighbourhoods in Santiago, Chile. Travel Behav. Soc. 2021, 23, 192–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.Y.; Chui, C.H.; Lou, V.W.; Chiu, R.L.; Kwok, R.; Tse, M.; Leung, A.Y.; Chau, P.-H.; Lum, T.Y. The contribution of sense of community to the association between age-friendly built environment and health in a high-density city: A cross-sectional study of middle-aged and older adults in Hong Kong. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2021, 40, 1687–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, A.; Al-Hagla, K.; Hasan, A.E. The impact of attributes of waterfront accessibility on human well-being: Alexandria Governorate as a case study. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2021, 12, 1033–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Sun, X.; Liu, C.; Qiu, B. Effects of urban landmark landscapes on residents’ place identity: The moderating role of residence duration. Sustainability 2024, 16, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patria, A.H.; Hussain, M.R.M.; Tukiman, I. The Significance of Pedestrian Pathways as Place Identity in an Urban Environment. Semarak Int. J. Des. Built Environ. Sustain. 2024, 1, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable Name | Formula | Expression | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Building with identifiers | The number of buildings with identifiers | Used to evaluate buildings with visually identifiable characteristics along the street. | |

| Pedestrians | denotes the proportion of pedestrian pixels, and the sum indicates the total number of pedestrian pixels in each image. | Recognizable individual pedestrians in the image, reflecting street vitality and perceived safety. It serves as an important visual indicator of walkability and social interaction. | |

| Landscape with identifers | Used to evaluate the number of landscape elements with visually identifiable features along the street. | ||

| Openness | denotes the proportion of sky pixels, and the sum indicates the total number of sky pixels in each image. | Represented by the proportion of sky pixels, serving as an important parameter for measuring spatial openness and psychological comfort. | |

| Interface enclosure degree | is the percentage of building pixels; is the percentage of tree; is the percentage of wall pixels; is the percentage of pavement; is the percentage of fence; is the percentage of road. | Used to measure the degree of spatial enclosure of the street. It is defined as the proportion of vertical interface pixels (building facades, trees, fences, etc.) to total pixels in the image. This index is regarded in environmental psychology as a key parameter reflecting “visual safety” and “sense of order,” and its conceptual logic has been validated in multiple studies based on street-view imagery. | |

| Walkable area | A higher walkable area ratio indicates a more pedestrian-supportive street environment, suggesting that the space is visually and functionally accessible for walking. | Reflects the proportion of space available for pedestrian activity in the street scene, calculated as the ratio of the combined pixel areas of sidewalks and carriageways to total image pixels. | |

| Vehicle occurrence rate | denotes the proportion of car pixels,

denotes the proportion of truck pixels,

denotes the proportion of bus pixels. is the percentage of road | Measures the degree of traffic disturbance. | |

| greenness | denotes the proportion of trees pixels, denotes the proportion of grass pixels, and the sum indicates the total number of tree pixels in each image. | Indicates the proportion of vegetation pixels, reflecting the visibility of natural elements within the street environment. | |

| wall | Proportion of pixels classified as wall. | Includes courtyard walls, fences, low walls, and continuous railings—non-building but vertically separating elements that contribute to the “street wall effect.” Especially in historic districts, such walls, though not counted as building volumes, significantly enhance boundary clarity and visual enclosure. | |

| road | Proportion of pixels corresponding to roads. | Refers to hard-paved surfaces used for vehicles or shared transport. It represents the basic spatial element of the street traffic system, and its visual proportion reflects spatial occupation and ground hardening rather than direct pedestrian accessibility. | |

| building | Proportion of pixels belonging to general building structures (excluding identifiers). | Refers to stable and continuous vertical entities facing the street (building facades or continuous street-facing structures). It constitutes the main component of the street’s “boundary,” directly shaping pedestrians’ perception of enclosure, scale, and order. |

| Group | Count | Mean | Std Dev | Min | 25% | 50% | 75% | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pedestrian Ratings | 225 | 3.53837 | 1.65852 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 7 |

| Professional Team | 225 | 3.56681 | 1.60419 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 7 |

| Lab Experts | 225 | 3.58015 | 1.64175 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 7 |

| Composite Score | 225 | 3.55944 | 1.48576 | 1.16000 | 3.89333 | 4.87333 | 4.87333 | 6.84667 |

| Street Type | Number of High-Quality Samples | Number of Low-Quality Samples | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural Street | 28 | 17 | 0.197 |

| Commercial Street | 31 | 16 | 0.244 |

| Residential Street | 15 | 41 | −0.318 |

| Street Type | Commercial Street | Cultural Street | Residential Street |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wall | 0.001696175 | 0.009416478 | 0.007568429 |

| Building | 0.354460329 | 0.24648419 | 0.340496224 |

| Openness | 0.388829292 | 0.468960098 | 0.400734966 |

| Road | 0.11064656 | 0.13236533 | 0.152070617 |

| Pedestrians | 0.00707082 | 0.007140928 | 0.00119 |

| Vehicle occurrence rate | 0.020039976 | 0.019627329 | 0.02727968 |

| Walkable area | 0.08970003 | 0.069454875 | 0.034182277 |

| Greenness | 0.0097503 | 0.033141775 | 0.01975854 |

| Interface enclosure degree | 1.854239753 | 1.494670294 | 2.278213772 |

| Building with identifiers | 1.140625 | 0.797101449 | 0.326086957 |

| Landscape with identifiers | 0.40625 | 0.362318841 | 0.195652174 |

| Unstandardized Coefficient (B) | Standardized Coefficient (Beta) | t | p | Collinearity Diagnostics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | VIF | Tolera | |||

| Constant | 0.448 | 0.137 | - | 3.271 | 0.001 ** | - | - |

| Building | −2.879 | 0.358 | −0.357 | −8.038 | 0.000 ** | 1.123 | 0.890 |

| Vehicle occurrence | −4.782 | 1.450 | −0.151 | −3.299 | 0.001 ** | 1.197 | 0.836 |

| Walkable area | 3.434 | 0.689 | 0.243 | 4.986 | 0.000 ** | 1.357 | 0.737 |

| Number of Landmark Buildings | 0.374 | 0.050 | 0.347 | 7.553 | 0.000 ** | 1.205 | 0.830 |

| Number of Landmark Landscapes | 0.322 | 0.067 | 0.212 | 4.812 | 0.000 ** | 1.106 | 0.904 |

| R2 | 0.616 | ||||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.607 | ||||||

| F | F (5219) = 70.314, p = 0.000 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tian, Y.; Sun, D.; Lyu, M.; Wang, S. Enhancing Pedestrian Satisfaction: A Quantitative Study of Visual Perception Elements. Buildings 2025, 15, 4389. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234389

Tian Y, Sun D, Lyu M, Wang S. Enhancing Pedestrian Satisfaction: A Quantitative Study of Visual Perception Elements. Buildings. 2025; 15(23):4389. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234389

Chicago/Turabian StyleTian, Yi, Dong Sun, Mei Lyu, and Shujiao Wang. 2025. "Enhancing Pedestrian Satisfaction: A Quantitative Study of Visual Perception Elements" Buildings 15, no. 23: 4389. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234389

APA StyleTian, Y., Sun, D., Lyu, M., & Wang, S. (2025). Enhancing Pedestrian Satisfaction: A Quantitative Study of Visual Perception Elements. Buildings, 15(23), 4389. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234389