Study on Shear Capacity of Horizontal Joints in Prefabricated Shear Walls

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Test Plan Design

2.1. Test Materials

2.2. Specimen Design

2.3. Strain Gauge Placement

2.4. Loading Scheme

- (i)

- a vertical loading assembly (20-ton lug-type hydraulic jack, distribution beam, and loading beam);

- (ii)

- a horizontal loading system (100-ton MTS actuator, loading fixture, and tie bars);

- (iii)

- an anchorage/support structure connecting the foundation beam to the reaction frame with out-of-plane bracing.

3. Test Results and Analysis

3.1. Test Phenomena

3.2. Load–Displacement Curves

3.3. Backbone Curve

3.4. Load-Carrying Capacity Analysis

4. Finite-Element Analysis

4.1. Finite-Element Model Setup

4.2. Comparison of Failure Patterns in Finite-Element Models

4.3. Comparison of Load–Displacement Curves

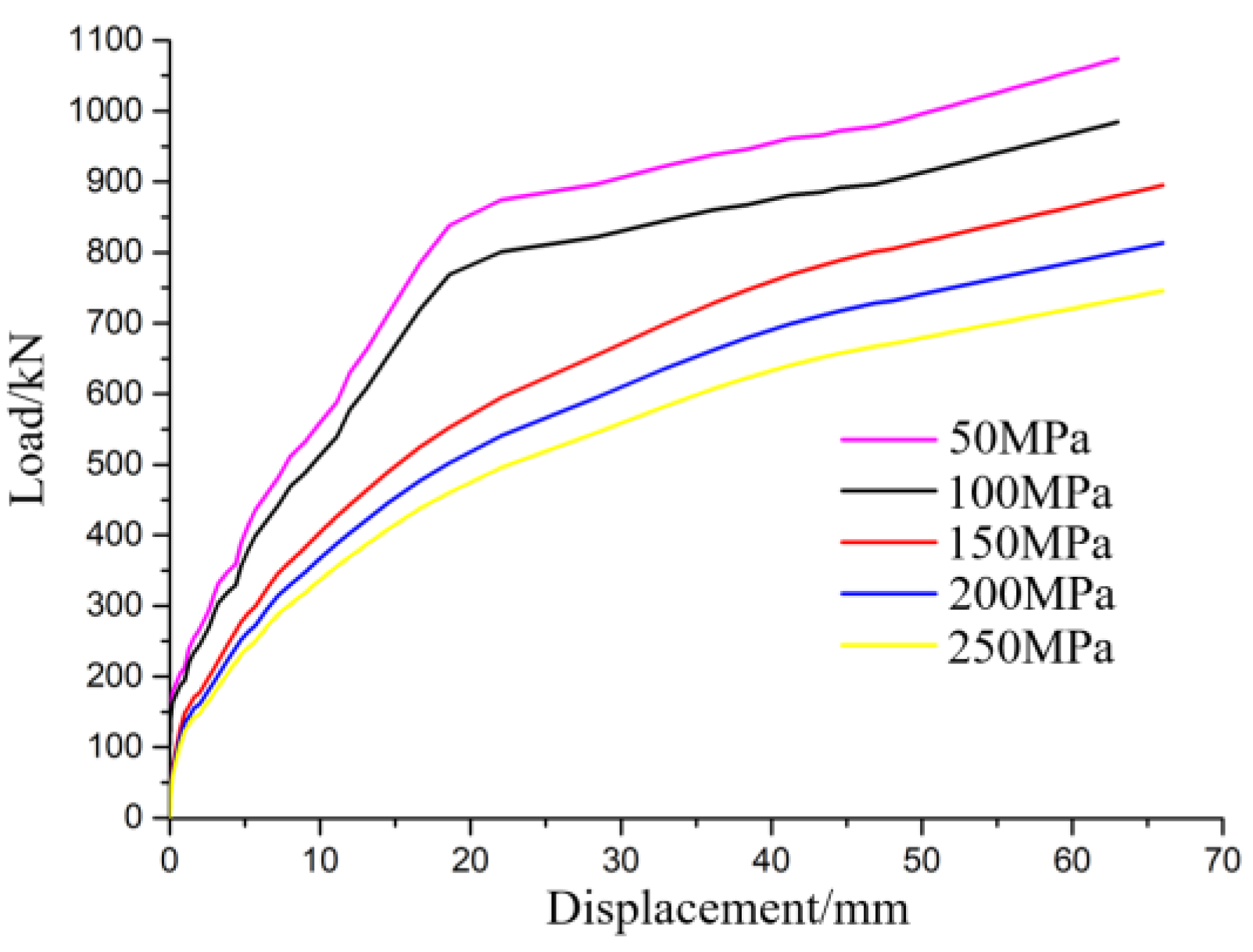

4.4. Parameter Analysis

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- All specimens exhibited brittle shear–compression failure characterized by grout layer crushing, through-joint cracking, and triangular block separation in the lower wall region. Increasing the bundled shear reinforcement ratio effectively enhanced the yield and peak loads, whereas a higher initial stress level in the reinforcement weakened the shear–friction mechanism, reducing the overall shear capacity.

- (2)

- Compared with monotonic loading, low-cycle reversed cyclic loading accelerated crack propagation and damage accumulation, resulting in faster stiffness degradation and reduced load-carrying capacity and ductility. Increasing axial tension further decreased both the yield and peak loads, with the reduction in peak load being more pronounced due to the progressive opening of the joint interface.

- (3)

- The finite-element simulations using the CDP model closely matched the experimental results, accurately reproducing the cracking and crushing behavior of concrete. The findings provide a theoretical foundation and practical reference for improving the shear design and seismic performance evaluation of horizontal joints in prefabricated shear walls.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Qiyun, Q.; Jia, P.; Wanlin, C.; Hongying, D. Seismic Performance of Innovative Prefabricated Reinforced Recycled Concrete Shear Walls. Structures 2023, 58, 105617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ximei, Z.; Jiayu, Y.; Can, C. Seismic Performance and Flexible Connection Optimization of Prefabricated Integrated Short-Leg Shear Wall Filled with Ceramsite Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 311, 125224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Cai, J.; Jin, B. Axial Compression Performance of Slurry-Wrapping Recycled Aggregate Concrete-Filled Steel Tube Short Columns under Freeze–Thaw Cycles. Struct. Concr. 2025, 26, 3416–3429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, A.; Liu, X. Seismic Performance of Discontinuous Cover-Plate Connection for Prefabricated Steel Plate Shear Wall. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2019, 160, 374–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, C.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, D.; Wu, C. Performance Evaluation and Shear Resistance of Modular Prefabricated Two-Side Connected Composite Shear Walls. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2021, 25, 2936–2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Finite Element Analysis Model Design on the Mechanical Properties of Prefabricated Shear Wall Structure. Sci. Program. 2022, 2022, 4633128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Shu, B.; Tang, H. Experimental Study on the Mechanical Properties of Horizontally Bolted Joints of Prefabricated Shear Walls. Int. J. Civ. Eng. 2024, 22, 1011–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Q.; Dong, G.; Ke, Y.; Tian, S.; Wen, S.; Tan, Y.; Gao, X. Seismic Behavior of Precast Double-Face Superposed Shear Walls with Horizontal Joints and Lap Spliced Vertical Reinforcement. Struct. Concr. 2020, 21, 1973–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Wang, Y.; Ji, S.; Liu, M.; Wang, D. Numerical Study on Mechanical Behaviors of New Type of Steel Shear-Connection Horizontal Joint in Prefabricated Shear Wall Structure. Buildings 2023, 13, 3000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, E.; Zhang, H.; Fu, C.; Hu, Q.; Fan, Y.; Taciroglu, E. Research on Design and Mechanical Behavior of a New Horizontal Connection Device of Prefabricated Shear Wall. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 370, 130713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Liu, Y.; Jin, R.; Chen, Y.; Pang, T.; Cai, J.; Liu, L. Prefabricated Shear Wall Vertical Steel Bar Concentrated Restraint Lap Connection. 2017. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=SHX-2ztJhdfoBUcXOZPFXCrL6yD9QoO24GtQzzsRqtSYHR0f0A-60hoS-s4vXI84NGL9pnEoMB_6pEjhAwc_6RrS8R8NISbhhtCoWEDdM0haBSQNY38ovY5WFL2OoB2USNShjA9FK5W-IC6bta6r1GtLID2sURGbIrmsF91kCpH17NZuaKJfUA==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Zhang, Q. Reinforcement Cluster Connection Mechanism Analysis of Precast Concrete Shear Wall Structures. Master’s Thesis, Southeast University, Nanjing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G. Experimental Study on Seismic Behavior of Bundle Connected Precast Concrete Shear Wall Structures. Master’s Thesis, Southeast University, Nanjing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhi, Q.; Yuan, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Jia, L.; Guo, Z. Experimental Research on Seismic Performance of Precast Concrete Shear Walls with a Novel Grouted Sleeve Used in the Connection. J. Earthq. Eng. 2024, 28, 1379–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, B.; Xiong, F.; Liu, B.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y. Shear Performance of Horizontal Joints in Short Precast Concrete Columns with Sleeve Grouted Connections Under Cyclic Loading. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0165988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Eller, B.; Rad Majid, M.; Fischer, S. Laboratory Tests and FE Modeling of the Concrete Canvas, for Infrastructure Applications. Acta Polytech. Hung. 2022, 19, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaleel Ibrahim, S.; Abbas Hadi, N.; Movahedi Rad, M. Experimental and Numerical Analysis of Steel-Polypropylene Hybrid Fibre Reinforced Concrete Deep Beams. Polymers 2023, 15, 2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grubits, P.; Cucuzza, R.; Habashneh, M.; Domaneschi, M.; Aela, P.; Movahedi Rad, M. Structural Topology Optimization for Plastic-Limit Behavior of I-Beams, Considering Various Beam-Column Connections. Mech. Based Des. Struct. Mach. 2025, 53, 2719–2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Yang, L.; Guo, X.; Li, A.; Qian, J.; Zhang, Y. Experimental and Numerical Study on Seismic Performance of Precast Concrete Hollow Shear Walls. Eng. Struct. 2023, 291, 116170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Hong Kong Institute of Steel Construction. An Experimental Study on Mechanical Properties of Concrete-Filled Steel Tube (CFST) Key-Connected Prefabricated Wall and Column; The Hong Kong Institute of Steel Construction: Hong Kong, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yooprasertchai, E.; Wiwatrojanagul, P.; Saingam, P.; Khan, K. Cyclic Behavior of Different Connections in Precast Concrete Shear Walls: Experimental and Analytical Investigations. Buildings 2023, 13, 1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, W.; Huang, Q.; Niu, P. Reversed Cyclic Tests on Precast Concrete Shear Walls with Grouted Corrugated Metallic Duct Connections. Eng. Struct. 2022, 256, 113948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Yu, Z.; Yu, Y.; Li, Z.; Cheng, S.; Zhang, G.; Cui, C. Experimental Investigation of Seismic Performance of Precast Concrete Shear Walls with Overlapping U-Bar Loop Connections. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, F. Simplified Modeling Method for Prefabricated Shear Walls Considering Sleeve Grouting Defects. Buildings 2024, 14, 1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.-C.; Wu, G.; Lu, Y. Finite Element Modelling Approach for Precast Reinforced Concrete Beam-to-Column Connections under Cyclic Loading. Eng. Struct. 2018, 174, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Yu, Z.; Yu, Y.; Liu, Q. Study on the Bond-Slip Numerical Simulation in the Analysis of Reinforced Concrete Wall-Beam-Slab Joint under Cyclic Loading. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 449, 138266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 50081-2019; Standard for Test Method of Mechanical Properties of Ordinary Concrete. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2019.

- GB/T 228.1-2010; Metallic Materials—Tensile Testing—Part 1: Method of Test at Room Temperature. China Standards Press: Beijing, China, 2010.

- JGJ/T101-2015; Technical Specification for Seismic Test of Buildings. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2015.

- Wang, B.; Gong, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, H. Prediction of the Yield Strength of RC Columns Using a PSO-LSSVM Model. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 10911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, W.; Yin, X.; Zhao, S.; Wang, D. Cyclic Loading Test Study on a New Cast-in-Situ Insulated Sandwich Concrete Wall. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0225055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Xuan, W.; Zhang, Y.; Cong, S.; Liu, F.; Gao, Q.; Chen, H. Experimental and Numerical Research on Seismic Performance of Earthquake-Damaged RC Frame Strengthened with CFRP Sheets. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2016, 2016, 6716329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Zhang, X.; Yang, H.; Li, S.; Cai, J.; Satyanaga, A.; Zhang, R.; Dai, G. Numerical Simulation of Cluster-Connected Shear Wall Structures under Seismic Loading. Buildings 2024, 14, 2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Fan, G.; Tao, L.; Yang, Y.; Wang, J. Seismic Behavior of Prefabricated Steel Reinforced Concrete Shear Walls with New Type Connection Mode. Structures 2022, 37, 483–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JGJ 1-2014; Technical Specification for Precast Concrete Structures. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2014.

| Specimen Number | Bundled Reinforcing Bars | Loading Method | Stress Level of Bundled Reinforcing Bars |

|---|---|---|---|

| YZA-1 | 8C14 | Reversed cyclic | 50 MPa |

| YZB-1 | 12C12 | Reversed cyclic | 50 MPa |

| YZB-2 | 12C12 | Monotonic | 100 MPa |

| YZB-3 | 12C12 | Reversed cyclic | 100 MPa |

| Specimen Number | Cracking Load Fcr/kN | Yield Load Fy/kN | Peak Load Fp/kN | Failure Load Fm/kN | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forward | Reverse | Average | Forward | Reverse | Average | Forward | Reverse | Average | Forward | Reverse | Average | |

| YZA-1 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 498 | 512 | 505 | 497 | 490 | 494 | 422 | 417 | 419 |

| YZB-1 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 552 | 476 | 514 | 566 | 542 | 554 | 481 | 461 | 471 |

| YZB-2 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 673 | 673 | 838 | 838 | 712 | 712 | |||

| YZB-3 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 422 | 337 | 380 | 451 | 386 | 418 | 383 | 328 | 356 |

| Density | Poisson’s Ratio | Eccentricity | Expansion Angle | fb0/fc0 | Kc | μ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2500 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 38 | 1.16 | 2/3 | 0.005 |

| Bundled Reinforcing Bar Stress/MPa | Axial Tensile Force/kN | Yield Load Fy/kN | Peak Load Fp/kN |

|---|---|---|---|

| 50 | 97.8 | 787.2 | 1074.0 |

| 100 | 165.6 | 721.6 | 984.5 |

| 150 | 233.4 | 656.0 | 895.0 |

| 200 | 301.2 | 596.4 | 813.6 |

| 250 | 369.0 | 546.7 | 745.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shen, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, P.; Feng, J.; Cai, J. Study on Shear Capacity of Horizontal Joints in Prefabricated Shear Walls. Buildings 2025, 15, 4160. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15224160

Shen X, Wang J, Liu P, Feng J, Cai J. Study on Shear Capacity of Horizontal Joints in Prefabricated Shear Walls. Buildings. 2025; 15(22):4160. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15224160

Chicago/Turabian StyleShen, Xuhong, Jinhao Wang, Peng Liu, Jian Feng, and Jianguo Cai. 2025. "Study on Shear Capacity of Horizontal Joints in Prefabricated Shear Walls" Buildings 15, no. 22: 4160. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15224160

APA StyleShen, X., Wang, J., Liu, P., Feng, J., & Cai, J. (2025). Study on Shear Capacity of Horizontal Joints in Prefabricated Shear Walls. Buildings, 15(22), 4160. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15224160