Abstract

In Puntarenas City, a historic and tourist port of Costa Rica, several vernacular buildings constructed in wood can be observed. Despite the prevalence of this architectural type in the area, there is an absence of comprehensive studies aimed at documenting this significant heritage. This article seeks to identify the vernacular architecture in this city through the architectural characterization, quantification, and geolocation of existing buildings, as well as the preliminary recognition of the state of conservation of the group of buildings. The methodological process proposed a four-stage approach. The initial stage involved an examination of documentary sources to verify existing information and obtain a preliminary profile of architectural characteristics. A participatory workshop with the community enabled the validation of this profile. The second stage comprised fieldwork, which yielded a starting list of properties. In the third stage, a detailed examination of the listed properties enabled the verification of the profile of characteristics, the delimitation of the architectural typologies, and the selection of buildings that did not fulfill the preliminary profile or possessed significant modifications that affected their architectural legibility. The fourth stage comprised the development of an inventory of vernacular architecture buildings and the systematic data transference to a Geographic Information System. This study mainly obtained the following results: an initial list of 172 wooden buildings in Puntarenas City and a geolocated inventory of 75 vernacular wooden architecture buildings that exhibit considerable architectural legibility. Moreover, identifying the uses and architectural features of the inventoried buildings permitted their categorization into ten distinct typologies.

1. Introduction

Vernacular architecture is a significant element within the territory [1]. It serves as a reference point for cultural identity [2] and the spirit of the place [3]. This implies not only a relationship with the image of the place but also a series of intangible aspects linked to traditional knowledge and trades, adaptation to the environment, traditions, the use and appropriation of space by people, and the interaction generated between the community and this heritage. Despite ongoing debate regarding its conceptualization [4] and conservation [2], it is imperative to prioritize efforts to study and showcase this architectural style, which frequently suffers from undervaluation due to its perceived simplicity.

At the international level, the various charters and documents related to vernacular architecture [3,5,6,7] highlight the necessity for its conservation. However, this cannot be achieved without a process of recognition. In light of the fact that in numerous locations there has been a tendency to exclude vernacular architecture from territorial planning and heritage safeguarding, it is of the utmost importance to develop processes that ensure both the community and the political and technical bodies of local governments are aware of and value this heritage. The destruction of vernacular architecture, as well as the loss of the architectural languages representative of a place, has the potential to negatively impact the territory [8].

Moreover, some authors argue that vernacular architecture is a relevant construction and sustainable development approach [9,10,11,12]. This is based on the use of natural materials, adaptation to the environment, and the low carbon footprint generated by such construction methods. In this sense, research into vernacular architecture represents an opportunity to learn from past practices and to enhance current and future construction methods. This underscores the pedagogical value of the subject [13] and the necessity to gain a deeper understanding of its characteristics and current status.

The country of Costa Rica is not unacquainted with this architectural style; however, there is a paucity of recognition and research on the subject. This contribution will address the vernacular wooden architecture of the city of Puntarenas as part of the initial steps towards its recognition.

The city of Puntarenas, built on a coastal arrow situated in the Gulf of Nicoya on the Pacific coast of Costa Rica, dates back to the late colonial period [14]. This locality legally began its port activities in 1814, leading to its growth, development, and identification as an epicenter for individuals engaged in trade, migration, and export activities [15]. However, with the creation of Puntarenas province in 1848 and the designation of the canton with the same name in 1858, the role of this urban center underwent a significant transformation. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the city undertook a series of modifications to its principal dock, extending its length and making it more advanced.

The expansion of the seaport increased commercial activity, boosted by the import and export of products and the provision of services to the national and international population. This situation contributed to the cosmopolitan character of the town. Following the construction of the large dock in 1930, the commercialization of wood, one of the most significant products, increased significantly. That same year, the electrification of the railroad became a reality. In 1950, the government built the Inter-American Highway. Furthermore, other developments occurred, such as building public spaces and urban facilities. All these projects stimulated intense economic and migratory activity between Puntarenas City, the rest of America, and Europe.

Concerning the economic activity between 1814 and 1821, tobacco (principal export product), mining, and coffee cultivation reactivated the maritime and commercial activities in the harbor [14]. Coffee, a product significantly associated with the historical development of Costa Rica, influenced the growth of Puntarenas when it entered the international market alongside other commodities such as pearl shells and leather.

The Port, as it is colloquially known, currently constitutes one of the most representative cities of Costa Rica, in which tourist activity has significantly influenced its development. Additionally, Puntarenas’ landscape, closely intertwined with the sea, showcases a variety of historical layers within its urban fabric, bestowing upon it a distinctive identity. One representative aspect of the local landscape is the vernacular architecture constructed from wood, primarily during the first half of the 20th century. These structures employ locally sourced materials and adapt to their surrounding environment through passive strategies and traditional knowledge.

One of the most notable characteristics of the Puntarenas landscape is the prevalence of vernacular wooden buildings. These structures, usually tall and ventilated, have become an integral part of the city’s identity. Additionally, the custom of utilizing the sidewalk in front of these houses as a meeting space, in the shade of the almond trees that predominate in the area [16], has become a defining aspect of the city’s culture.

The development of vernacular architecture in Puntarenas is related to the abundance of wood both on the site and in nearby areas. This abundance was linked through cabotage between the late nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth century. Additionally, the presence of a considerable number of sawmills in this small town [17] promoted the use of wood mainly for housing construction.

The vernacular buildings of Puntarenas, similarly to other examples in other areas of the country [18,19], originated from the influence of the arrival of Victorian architecture and its industrialized construction techniques. The use of sawn wood became popular as a result of this influence, and the people who worked as laborers learned how to build in accordance with the new techniques. Subsequently, the introduction of machinery and the necessity for new construction prompted the emergence of a distinct local architectural style. This style was largely independent of professional input and incorporated elements such as decorative embellishments and passive design strategies [20].

These buildings have been designed in accordance with passive strategies, which have been implemented through the application of traditional knowledge. This allows for adaptation to the specific characteristics of the site. It is important to note that Puntarenas is characterized by a tropical climate with a short and moderate dry season, as well as a long and very severe rainy season. The average maximum temperature is 31.0 °C, while the minimum is 22.7 °C [21]. Therefore, environmental adaptation was essential to improve aspects such as ventilation in order to generate comfort.

The research “Characterization of the Vernacular Wooden Architecture of the City of Puntarenas from an Interdisciplinary Perspective” aims to characterize this architecture type based on architectural, pathological, and xylological studies that promote its conservation and enhancement. The project, developed between 2022 and 2024, represents a collaborative effort between the Schools of Architecture and Urban Planning, Forestry Engineering, and Biology of the Technological Institute of Costa Rica (TEC). This project represents a continuation of similar investigations conducted by experts from TEC about wood architecture along the Costa Rican Caribbean coast, specifically in Limon City and in the urban centers of Cahuita, Puerto Viejo, and Manzanillo.

This contribution, as part of the initial specific objective of the project, pursues the goal of identifying vernacular architecture in Puntarenas through the architectural characterization, quantification, and geolocation of existing properties. In addition, it seeks to evaluate the preliminary state of preservation of the group of buildings, thus ensuring the visibility of this architectural type. This article expands on the contribution presented in Gijón, Spain, in May 2024 at the 10th Euro-American Congress Construction Pathology, Rehabilitation Technology and Heritage Management (REHABEND) 2024, entitled “Identification of the Vernacular Architecture of the City of Puntarenas” (Code 152) [22].

2. Materials and Methods

Documentation and information records about vernacular architecture buildings ensure the preservation of this knowledge for future generations and the protection of these properties [23]. Several case studies [24,25,26,27,28,29] illustrate the methodological relevance of the inventories. In the case of the city of Puntarenas, the methodology applied is based on the researchers’ previous experience, as demonstrated by their work on the inventory of Costa Rican Caribbean architecture [30]. To enhance the identification processes, the research team employed a range of techniques, including participatory workshops and focus groups to validate the characteristics and inventory, urban tours with community leaders, the definition of typologies based on architectural characteristics and use, and the utilization of supplementary resources such as old photographs shared on social networks by community members and drone flights.

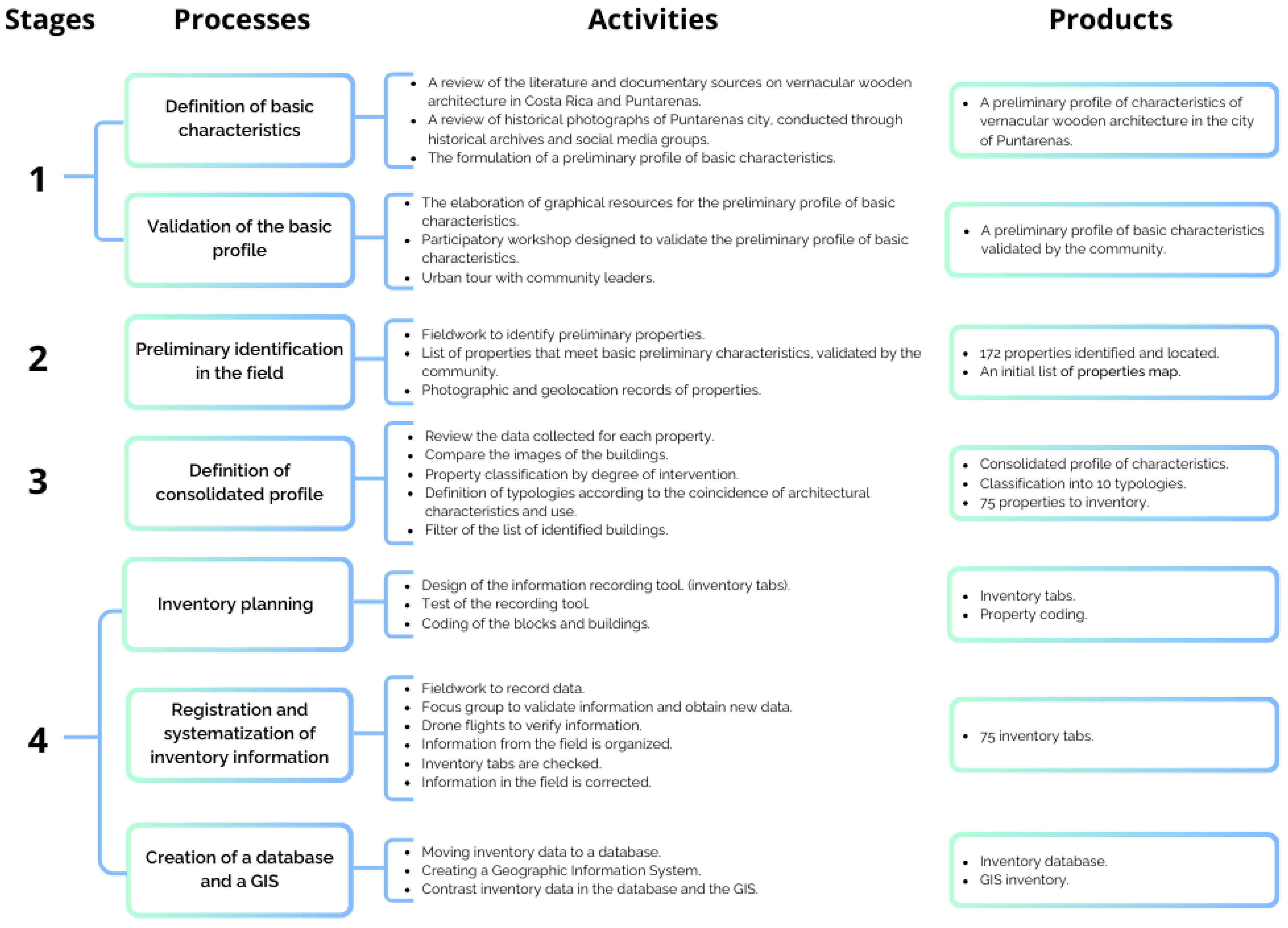

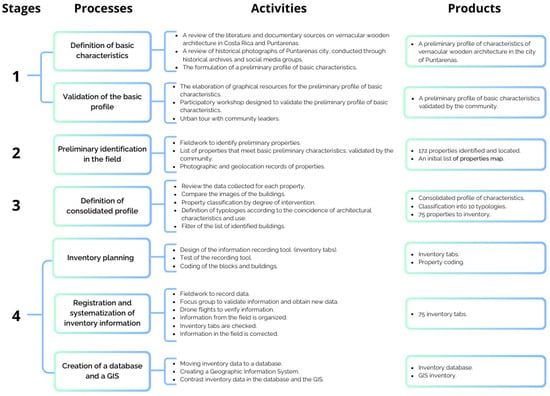

The study area encompasses the Central, Carmen, and Playitas neighborhoods of the Puntarenas district of the canton of the same name, encompassing a total of 93 blocks. To guide the methodological process, four stages were established, delineating their respective processes, activities, and products (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Methodological process for the identification of vernacular wooden architecture in the city of Puntarenas.

During the first stage, this project entailed a comprehensive documentary analysis to establish the state of the art regarding vernacular wood architecture in Costa Rica, focusing on Puntarenas urban center. Furthermore, examining historical archives and old photographs, including those presented in the exhibition “Puntarenas de Ayer” at the Casa de la Cultura de Puntarenas “Elsie Canessa de Odio” in 2022, contributed to this phase. Another source utilized was social media, particularly Facebook, to locate images of the properties under study through the publications of groups dedicated to sharing old photographs of Costa Rica and neighbors of Puntarenas.

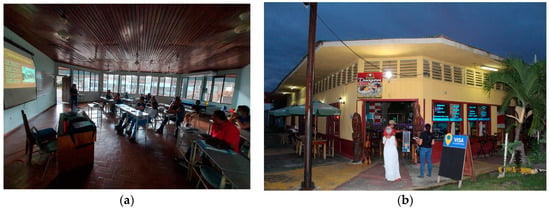

The data from the selected sources supported the elaboration of a basic profile containing a preliminary list of characteristics. Digital illustrations developed using the Creative Cloud package (Adobe, San José, CA, USA) complemented the profile and nurtured the validation process and identification in the field. In 2022, a participatory workshop developed on September 22 gathered chief stakeholders such as the Municipality of Puntarenas members, community leaders, members of the academic community, and some owners of the vernacular architecture properties. During the workshop, the research team presented the project objectives and graphical materials to the attendees; the participants engaged in a comprehensive discussion and validation process for each preliminary characteristic. After the workshop, an urban tour commenced, with community leaders allowed to visit several properties and meet their respective owners After the workshop, an urban tour with community leaders allowed to the reasearchers to visit several properties and meet their respective owners (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

(a) Participatory workshop with local stakeholders; (b) urban tour with community leaders.

In the second stage, the observations made during the workshop supported expanding the initial basic profile. This profile served as a guide for a first field survey to identify and quantify buildings that exhibited at least one main feature of this type of architecture: the use of wood in enclosures and primary and secondary structures. A photographic record complemented for documenting the buildings, and the Google My Maps application simplified geolocalizing them. Each recorded point included both images and notes.

In the third stage, the information obtained in the field eased the creation of a map delineating the locations of the buildings and a database utilizing Microsoft Excel. These tools then functioned to analyze the data, which involved reviewing the gathered information from each property and comparing the images taken in the field. This process resulted in the generation of a comprehensive profile of the characteristics.

A new review of each property was conducted based on the revised profile, considering the presence of as many characteristics as possible. This activity facilitated the identification of those buildings that did not fulfill the revised profile. A classification process was also initiated, categorizing the properties according to the degree of intervention (untransformed, minimally transformed, significantly transformed). This classification is crucial, as it influences the architectural legibility of the buildings.

The previous activities contributed to improving the list of properties by including in the study only those that matched the profile of features and presented minimally or not at all modifications. Also, the definition of typologies represented a basis for classifying the buildings regarding their use and the coincidence of the architectural characteristics identified.

Finally, in the fourth stage, a new process of recording information in the field started and required the design and on-site evaluation of inventory tabs. The observations obtained after the pilot study permitted the respective adaptation of the inventory tabs. In addition, where possible, owners and tenants shared relevant information about the properties through unstructured interviews.

Employing a unique code for each block and the clockwise numbering of the identified buildings facilitated the fieldwork for the inventory. Researchers and student assistants formed working groups of two or three individuals and recorded data on the study area, previously divided into four sectors. Also, the teams generated a more detailed photographic record and were able to verify the geolocation of buildings in My Maps.

Holding a focus group with community social actors empowered the validation of the gathered information and the collection of new data. In this activity, the researchers presented the preliminary inventory map, images of each property, and new illustrations of the characteristics.

Using a DJI Mavic Pro drone during fieldwork complemented the obtained information through detailed aerial photographs of the blocks. Furthermore, reviewing the mosaic of orthophotos at a scale of 1:1000 (2015–2018), produced by the Department of Geography and Geomatics of the National Geographic Institute through the National Territorial Information System (SNIT), made it possible to verify aspects related to the physical layout of the buildings in the lots and the configuration of the roofs.

After gathering the data, the research team updated the inventory records and digitized the dataset using Microsoft Excel. Furthermore, the following step consisted of transferring the geolocated points to the QGIS program to create a Geographic Information System (GIS) fed with data from the inventory records. Then, the researchers prepared thematic maps to analyze the information.

Other stages of the project involved an interdisciplinary approach. This approach included conducting architectural surveys, drawing architectural plans, characterizing lesions, and carrying out xylographic studies in some representative buildings of this architectural style identified in the inventory.

3. Results

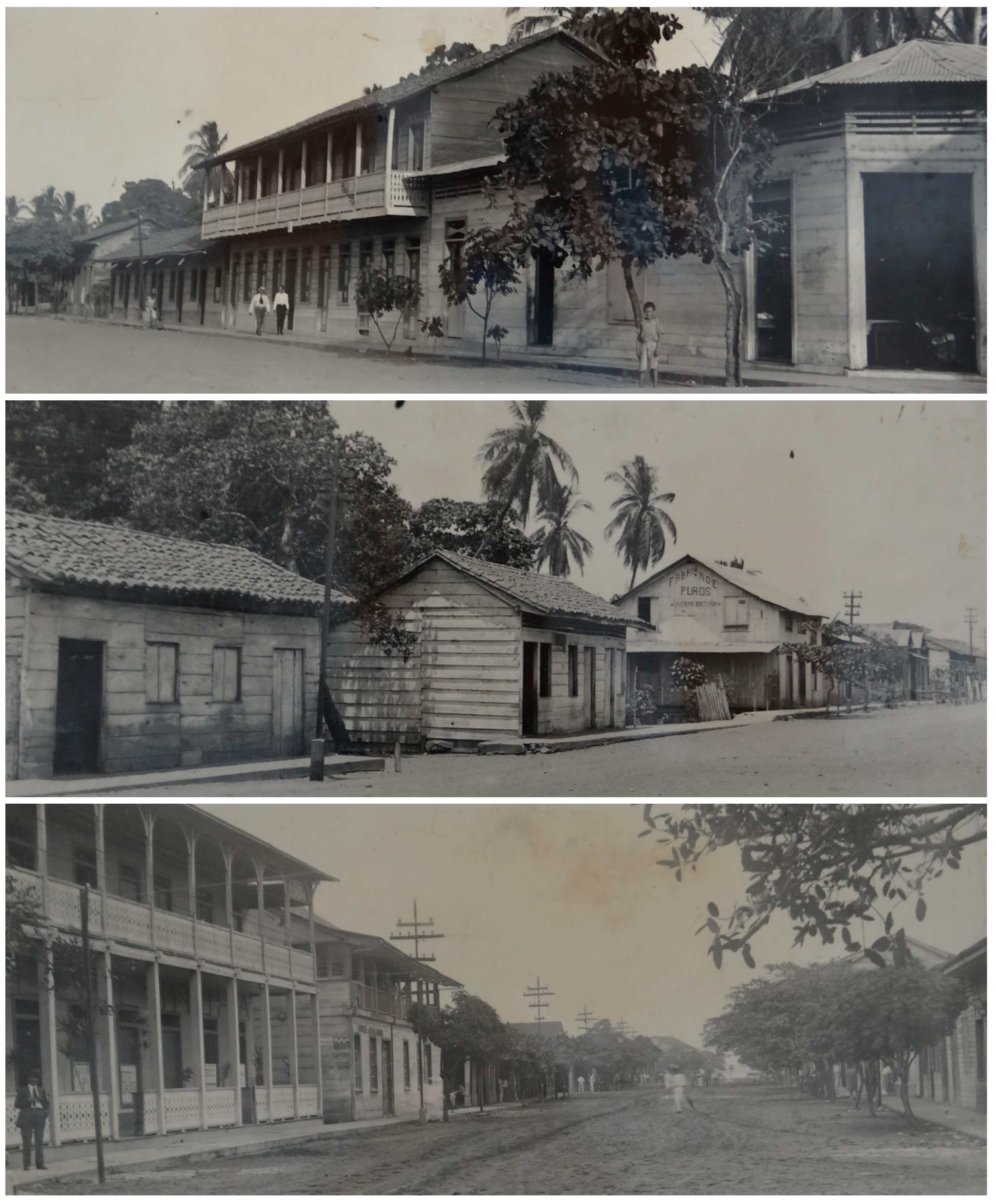

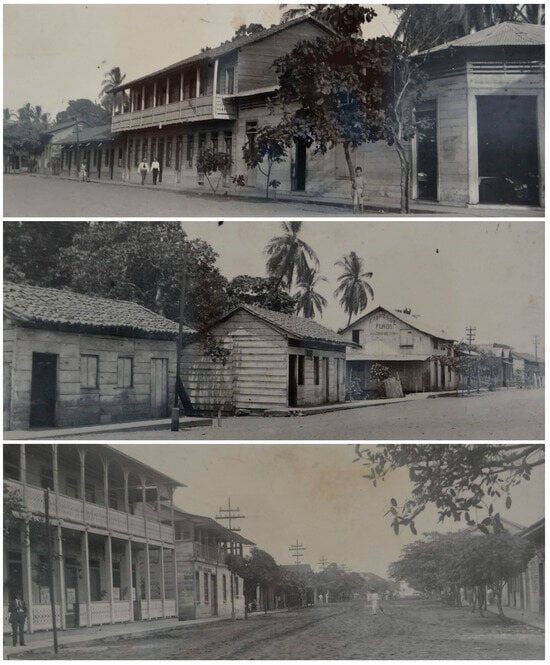

The documentary analysis results revealed a deficiency in researching vernacular wood architecture in the country, with a lack of identifiable publications. Concerning Puntarenas’ urban center, the identified information on wood architecture is relatively scarce; most references were found in texts about the city’s history [14,15] and the history of Costa Rican architecture [16,17,18,19,20]. The historical archives contained limited visual documentation of the subject under investigation, although it was possible to locate photographs of the city and notable urban spaces such as the pier (Figure 3). A search on social media revealed that seven Facebook groups had posted old photographs of Costa Rica and Puntarenas; 74 pictures belonged to the study area.

Figure 3.

Old photographs of Puntarenas. Source: “Puntarenas de Ayer” exhibition, Casa de la Cultura de Puntarenas, 2022.

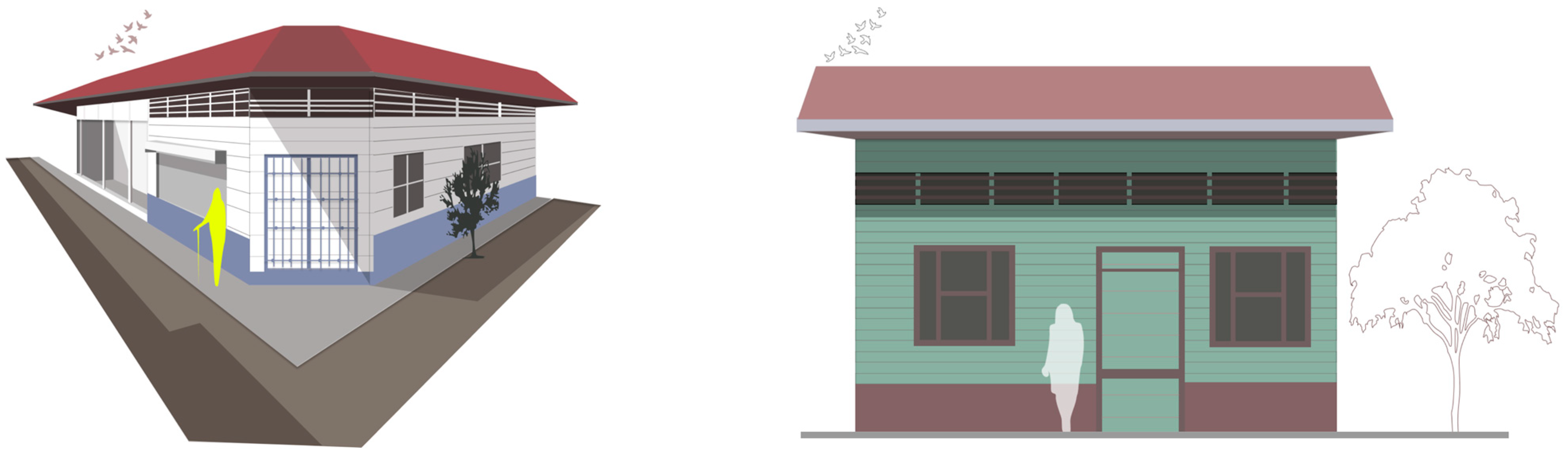

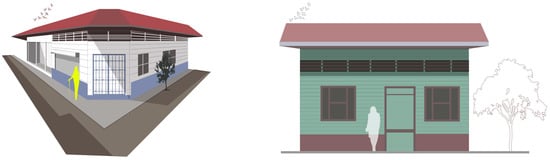

Analyzing the descriptions from publications and comparing the images enhanced the creation of a preliminary basic profile of architectural characteristics of vernacular architecture buildings. This profile includes the use of wood as the predominant material for the structure and enclosures; elements that allow ventilation, such as fretwork, wooden lattices or “petatillos”, and wooden grilles located on doors, windows, and wall finishes; chamfered corner buildings; buildings without front setbacks; high roofs; and steep-slope roofing. Consequently, various illustrations graphically exemplify these features, for instance, Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Example of the illustrated characteristics. Authorship: student assistant Pedro Garay Bustos.

The participatory workshop prompted the presentation of each characteristic and the integration of new contributions from the participants. They mentioned the use of wood in floors and their structural joists, tall windows with wide moldings, sash or shuttered windows, and attached living units, known as “chinchorros”. Furthermore, images from social networks were presented at the workshop to verify their authenticity as properties within the designated area and to utilize them as illustrative references to exemplify the presence of the traits mentioned previously.

Likewise, data regarding property owners was gathered, along with information related to historical aspects of the city and vernacular architecture. A site tour of the study area with community members comprised visiting several properties, establishing contact with owners, and, in some cases, taking photographs of the interiors of the buildings.

The preliminary survey enabled the geolocation of 172 wooden buildings via the My Maps tool. This activity included taking at least one photograph of the primary facade of each property and recording a basic description of the building.

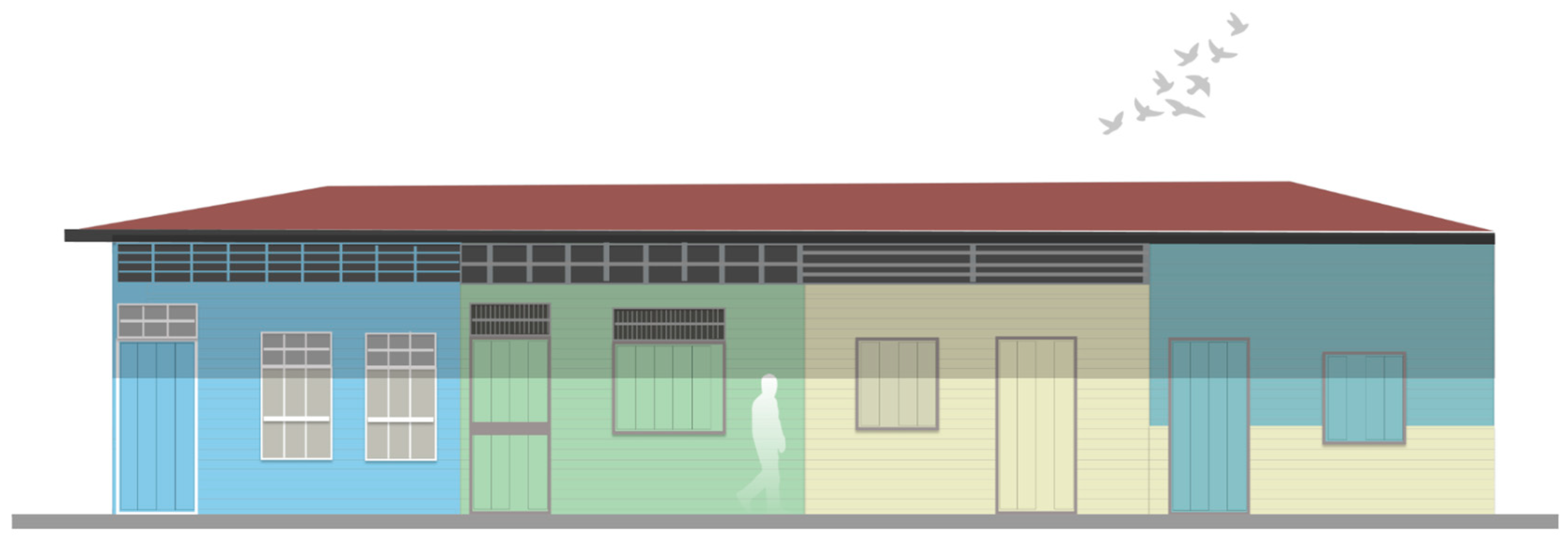

The primary result of this phase was a location map of the identified properties and a preliminary database. The analysis of this information endorsed the establishment of a consolidated profile containing the characteristics mentioned above and adding new ones such as the predominant uses, the location arrangement, the diverse roof types (predominantly gable roofs and multiple roofs in corner buildings), the chromatic variety standing out pastel colors, the types of lattice and fretwork on top of windows and facade walls, the use of corrugated galvanized steel sheeting (although, according to old photographs, it was common to use roof tiles in the past), the high ceilings, and some passive design strategies that allow the stack effect (ventilated ceilings and wooden lattices in facade wall tops). Similarly, the xylological studies conducted during the research period helped identify the use of wood from native species, including pochote (Pochota fendleri), cedar (Cedrela odorata) [31] and laurel (Cordia alliadora), and these woods are distinguished by their high density. They are notable for their strength and resistance to deformation, in addition to their resilience to biological agents.

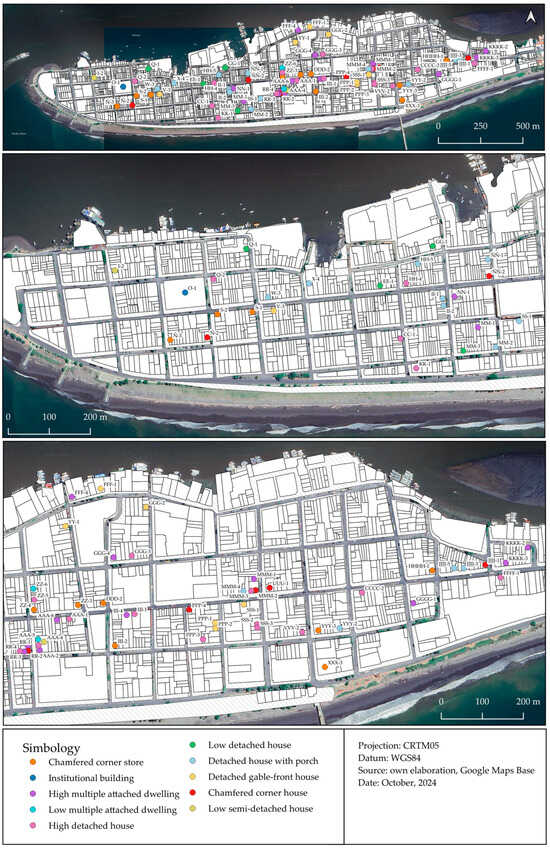

Considering the consolidated profile and the degree of intervention, each building was subjected to a review, resulting in the exclusion of those that mismatched the profile (41 buildings) or lost architectural legibility (53 buildings); in addition, in September 2023, the researchers detected the demolition of three formerly identified buildings and excluded them from the inventory. As a result of this reclassification, the study limited the number of buildings to 75 and categorized them into ten typologies (Figure 5, Table 1).

Figure 5.

Location of the 75 inventoried properties.

Table 1.

Distribution of properties by typology of vernacular wooden architecture in the city of Puntarenas.

The initial survey identified a two-story building designated as VVV-4 and originally proposed as an additional typology. During the process of documenting the properties, this registration was unsuccessful because the building had already been demolished (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Building VVV-4: (a) two-story building registered on 23 September 2022; (b) the lot where the two-story building was located, registered on 18 September 2023.

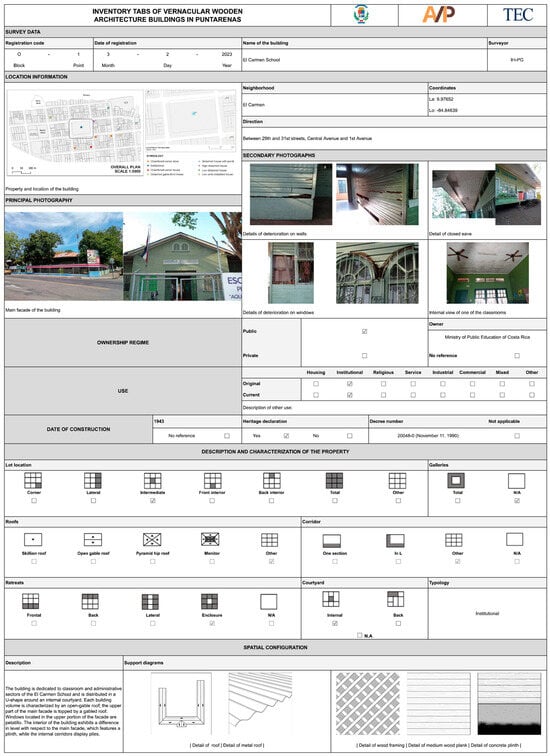

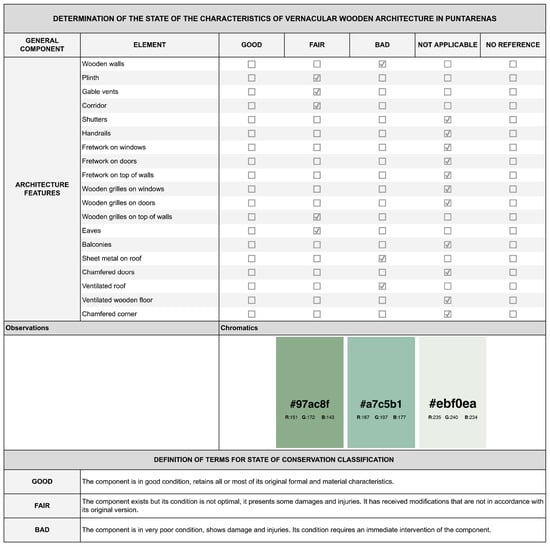

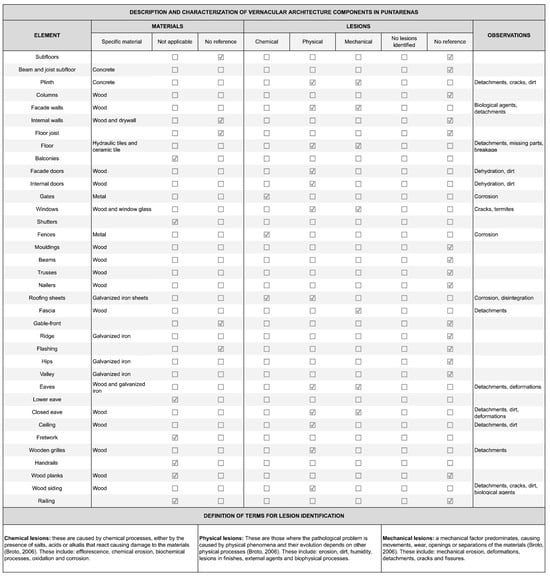

A total of 75 inventory tabs emerged from the fieldwork for the inventory (Figure 7). These include location information, photographs, details on the ownership regime, usage, construction date, typology, and a description and characterization of the property. Additionally, the inventory tabs contain information about the spatial configuration, the condition of the vernacular architecture, the architectural components, and an approximation of the identification of lesions. Employing a Geographic Information System (GIS) allowed the incorporation of the data obtained from the files and the geographical localization of the information.

Figure 7.

Example of an inventory tabs, property O-1 [32].

The inventory tabs reveal several significant lesions, including chemical lesions resulting from fungal activity and oxidation; physical lesions caused by humidity, dirt, detachment of material, and wood dehydration; and mechanical lesions such as deformations and cracks. However, these latter lesions are less prevalent.

4. Discussion

Of the total number of properties recorded in the initial survey, 57.2% have undergone minimal alterations, while 40.5% have experienced a significant loss of architectural legibility due to modifications involving remodeling, additions, changes in use, or abandonment. Furthermore, the destruction by demolition affected 2.3% of the properties during the project development.

Concerning the inventory, the geolocation of properties indicates that 43% of the blocks within the study area present at least one building. In contrast, the coastal zone, where commercial, tourist, and fishing activities are predominant, only possesses a few vernacular buildings.

Analyzing the buildings by typology, the study detected an uneven distribution, complicating the formation of groups of the same typology. However, the highest density of buildings was found in the Central neighborhood, specifically in two groups formed in blocks RR, ZZ, and AAA, with 14 buildings representing six typologies, and in blocks MMM, PPP, and SSS, with 11 buildings and five typologies.

Likewise, some typologies show a slight presence, with less than four properties per typology, specifically low detached house, low multiple attached dwelling, low semi-detached house, and institutional building. The complex presents a dispersed disposition of the buildings in question.

This study area constitutes one of the principal clusters of vernacular wood architecture in Costa Rica due to the number of buildings identified, representing 8.6% of the overall number of buildings within Puntarenas City. Nevertheless, this architectural heritage remains unprotected since merely a single building within the inventory (El Carmen School) received the declaratory of historical architectural heritage, the official protective measure in the country. This lack of official recognition and designation endangers the conservation of this heritage resource. This situation is similarly evident at the municipal level, where there is a lack of recognition, declaration, planning, or management instruments designed to promote the preservation of this heritage resource.

One noteworthy aspect of the urban landscape is the prevalence of inhabited dwellings among the identified properties. This evidence suggests that the owners are generally committed to maintaining their properties to an acceptable standard. Overall, the façades of the buildings studied show a good state of conservation or at least fair condition, influencing the perception of the complex positively.

Finally, the activities conducted with community members demonstrate that the social actors recognize the architectural uniqueness of Puntarenas City and can discern specific characteristics of the buildings. However, there remains a lack of widespread awareness of the architectural significance and the potential risks to the local identity associated with the loss of these structures.

The presented facts substantiate the value of vernacular architecture for a territory and highlight the significance of recognizing and valuing this heritage, as addressed in the referenced sources, to ensure its conservation. Furthermore, from a sustainable development perspective, this case study contributes to the knowledge of a group of buildings that require safeguarding and the generation of protection and planning tools.

5. Conclusions

The characteristics identified in the buildings studied reveal the use of local woods, the application of bioclimatic strategies, and the development of an architectural and esthetic language that allows the understanding of it as vernacular architecture. Adaptation to the context and the role as a valuable element of local identity are two outstanding attributes of this type of architecture.

The study results indicate that Puntarenas City still has a representative number of vernacular architecture buildings. As evidenced by the data obtained through consultation with the property owners during the inventory survey, all the properties were constructed between the late 19th century and the early 20th century. Consequently, they are examples of buildings of considerable age. The location and number of buildings inventoried demonstrate that this architectural style constitutes a significant urban and landscape element.

At the outset of this investigation, the vernacular architecture of the city of Puntarenas was largely unstudied. While this paper promotes its recognition, further research is essential to fill the gaps in knowledge.

The process of identification and characterization represents a preliminary step for recognizing this architectural heritage; however, pursuing further participatory phases that engage the community and public and private institutions constitutes a necessity for its valorization and management.

Although several buildings remain, the alterations and demolitions observed suggest a potential risk to the city’s heritage. These transformations could affect the urban landscape and the future use of these valuable resources in Puntarenas.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.G.-B. and D.P.-A.; methodology, K.G.-B. and D.P.-A.; software, K.G.-B. and D.P.-A.; validation, K.G.-B. and D.P.-A.; formal analysis, K.G.-B. and D.P.-A.; investigation, K.G.-B. and D.P.-A.; resources, D.P.-A.; data curation, D.P.-A.; writing—original draft preparation, K.G.-B. and D.P.-A.; writing—review and editing, K.G.-B. and D.P.-A.; visualization, D.P.-A.; supervision, D.P.-A.; project administration, K.G.-B.; funding acquisition, K.G.-B. and D.P.-A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Vice-Rectory of the Research and Extension (VIE) of the Technological Institute of Costa Rica (TEC) funded this research. Project number: 1412022.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the Vice-Rectory of Research and Extension of the Technological Institute of Costa Rica for providing financial support for the research project, “Characterization of the vernacular wooden architecture of the city of Puntarenas from an interdisciplinary perspective”. They also extend their appreciation to the remaining research team members, Dawa Méndez-Alvarez, Roger Moya-Roque, William Rivera-Méndez, Ileana Hernández-Salazar, Danilo Valerio-Alfaro, Mauricio Guevara-Murillo, and the student assistants who contributed to the project, as well as the members of the Puntarenas community who participated in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Barbarich, M. Las maderas nativas en la arquitectura vernácula de la Puna Jujeña, Argentina: ¿Continuidad o reemplazo? Boletín De La Soc. Argent. De Botánica 2022, 57, 403–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, J.P. La cuestión de la conservación de la materia en la arquitectura vernácula: Teoría, autenticidad y contradicciones. Conserv. Património 2020, 35, 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIVVIH, ICOMOS. Principios de La Valeta para la salvaguardia y gestión de las poblaciones y áreas urbanas históricas. PATRIMONIO”Econ. Cult. Y Educ. Para La Paz (MEC-EDUPAZ) 2018, 1. Available online: https://www.patrimoniocultural.gov.pt/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/2011-principios_de_la_valette_para_a_salvaguarda_e_gestao_de_cidades_e_conjuntos_urbanos_historicos-icomos.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Pérez, J. Un marco teórico y metodológico para la arquitectura vernácula. Ciudad. Rev. Del Inst. Univ. De Urbanística De La Univ. De Valladolid 2018, 21, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charter on the Built Vernacular Heritage. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/images/DOCUMENTS/Charters/vernacular_e.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- Principios Para la Conservación del Patrimonio Construido en Madera. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/images/DOCUMENTS/Charters/GA2017_6-3-4_WoodPrinciples_ESP_adoptados-15122017.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Carta de Cracovia 2000* Principios Para la Conservación y Restauración del Patrimonio Construido. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/2611196.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- Al-Mohannadi, A.; Furlan, R.; Major, M.D. A cultural heritage framework for preserving Qatari vernacular domestic architecture. Sustainability 2018, 12, 7295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talenti, S.; Teodosio, A. At the roots of sustainability: Mediterranean vernacular architecture. In Proceedings of the HERITAGE 2022—International Conference on Vernacular Heritage: Culture, People and Sustainability, Valencia, Spain, 15–17 September 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zong, J.; Wan Mohamed, W.S.; Zaky Jaafar, M.F.; Ujang, N. Sustainable development of vernacular architecture: A systematic literature review. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2024, 2014, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Convertino, F.; Di Turi, S.; Stefanizzi, P. The color in the vernacular bioclimatic architecture in Mediterranean region. Energy Procedia 2017, 126, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, W.; Bahauddin, A. A Bibliometric Review of the Development and Challenges of Vernacular Architecture within the Urbanisation Context. Buildings 2023, 13, 2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozorhon, G.; Ozorhon, I.F. Learning from Vernacular Architecture in Architectural Education. Megaron 2020, 15, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valverde-Espinoza, A. La Ciudad de Puntarenas. Una Aproximación a su Historia Económica y Social 1858–1930; SIEDIN-UCR: San José, Costa Rica, 2008; pp. 1–120. [Google Scholar]

- Chen-Mok, S. Elementos históricos del desarrollo del turismo en Puntarenas. Diálogos Rev. Electrónica De Hist. 2012, 13, 121–150. [Google Scholar]

- Sanou, O. (Coord.). Guía de Arquitectura y Paisaje de Costa Rica; Junta de Andalucía, Consejería de Obras Públicas y Vivienda/Colegio Federado de Ingenieros y Arquitectos de Costa Rica: San José, Costa Rica, 2010; p. 554. [Google Scholar]

- Baltodano, E. Mi Puntarenas: Radiografía Retrospectiva; Baltodano, E: San José, Costa Rica, 2007; pp. 1–92. Available online: https://isbncostarica.sinabi.cerlalc.org/catalogo.php?mode=detalle&nt=16393 (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- García-Baltodano, K.; Hernández-Salazar, I.; Porras-Alfaro, D.; Méndez-Álvarez, D.; Chang-Albizurez, D.; Salazar-Ceciliano, E.; Guevara-Murillo, M. Inventario de Edificaciones de Arquitectura Caribeña Costarricense en la Ciudad de Limón; Instituto Tecnológico de Costa Rica: San José, Costa Rica, 2021; Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/2238/13405 (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Malavassi-Aguilar, R.E. Los “barrios del sur” del Cantón Central de San José, Costa Rica. Los corredores históricos y la vivienda de madera, 1910–1955. In La Conservación del Patrimonio Cultural en Costa Rica; Aguilar-Bonilla, M., Niglio, O., Eds.; Aracne Editrice: Roma, Italy, 2015; pp. 447–469. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, A. El patrimonio histórico-arquitectónico en el panorama cultural de Costa Rica. Rev. Herencia 2010, 23. Available online: https://revistas.ucr.ac.cr/index.php/herencia/article/view/10337 (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Municipalidad de Puntarenas. Plan de Acción Para la Adaptación al Cambio Climático del Cantón de Puntarenas 2022–2031. Proyecto Plan A: Territorios Resilientes Ante el Cambio Climático; Municipalidad de Puntarenas y DCC-MINAE: San José, Costa Rica, 2021; pp. 1–73.

- García-Baltodano, K.; Porras-Alfaro, D. Identification of the Vernacular Architecture of the City of Puntarenas. In Proceedings of the Rehabend 2024 Euro-American Congress: Contrucction Pathology, Rehabilitation Technology and Heritage Management, Gijón, Spain, 7–10 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Agudo, J.; Sánchez, I.; Delgado, A. Inventarios de Arquitectura Tradicional. Paradigmas de inventarios etnológicos. Patrim. Cult. De España 2014, 8, 133–151. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/11441/72810 (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Castillo, C.; Pérez, C. Caracterización de la arquitectura vernácula en madera de complejos constructivos rurales, región de Aysén, Chile. Intervención 2019, 10, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, C.; Pérez, C. Arquitectura en adobe y quincha: Construcción de una identidad en torno a los recursos naturales de la ribera del Lago General Carrera en la región de Aysén, Chile. Ge-Conservación 2020, 18, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Guzmán, C. Identificación del patrimonio arquitectónico vernáculo y los lenguajes de patrones arquitectónicos. en las comunidades de Nautla, Veracruz. Legado De Arquit. Y Diseño 2023, 18, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jové, F.; Solano, J.; Hernán, L. La arquitectura vernácula en el medio rural y urbano de Manabí. Levantamientos, análisis y enseñanzas. Análisis tipológico y constructivo como respuesta al clima de la región de Manabí (Ecuador). In Hábitat Social, Digno, Sostenible y Seguro en Manta, Manabí, Ecuador; Sáinz, J., Camino, M., Eds.; AECID: Valladolid, Spain, 2014; pp. 135–143. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, C.; Ferreira, T.M.; Vicente, R.; da Silva, J.R.M. Building typologies identification to support risk mitigation at the urban scale–Case study of the old city centre of Seixal, Portugal. J. Cult. Herit. 2013, 14, 449–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kari, N.; Nabil, O.M. Identifying and documenting the Traras mountains (Northwest-Algeria) rural heritage architectural features: An architectural survey. PASOS Rev. De Tur. Y Patrim. Cult. 2021, 19, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Baltodano, K.; Méndez-Álvarez, D.; Varela-Fonseca, A.; Porras-Alfaro, A. Biodeterioration of heritage buildings representative of Costa Rican Caribbean architecture. Conserv. Sci. Cult. Herit. 2023, 23, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Baltodano, K.; Méndez-Álvarez, D. Investigación interdisciplinar sobre la arquitectura vernácula de Puntarenas. Investiga. TEC 2024, 17, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broto, C. Enciclopedia Broto de las Patologías de la Construcción; Links Books: Barcelona, Spain, 2006; pp. 1–1389. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).