Cheong Wa Dae: The Sustainability and Place-Making of a Cultural Landmark, Reflecting Its Role in History and Architecture

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background and Literature Review

2.1. History and Background of Cheong Wa Dae

2.1.1. History of Cheong Wa Dae

2.1.2. Changes in Cheong Wa Dae During Different Presidential Administrations

President Roh Tae-Woo (February 1988~February 1992)

President Kim Young-Sam (February 1993~February 1998)

President Kim Dae-Jung (February 1998~February 2003)

President Roh Moo-Hyun (February 2003~February 2008)

President Lee Myung-Bak and Park Geun-Hae (February 2008~February 2013, February 2013~March 2017)

President Yoon Suk-Yeol (May 2022~Present)

2.2. Architectural Characteristics of Cheong Wa Dae

2.2.1. Main Building

2.2.2. Young Bin Kwan

2.2.3. President’s Official Residence

2.2.4. Sang Choon Jae

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Analysis of Current Programs and Events

3.2. Review of the Statistical Data on Cheong Wa Dae Visitors

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Leveraging its physical environment to host global events, promote natural landscapes, and facilitate biodiversity initiatives.

- Developing programs that emphasize cultural and culinary experiences, as well as enhancing visitor engagement through heritage-based offerings [39].

- Incorporating principles of sustainability, and aligning programs with the UN SDGs, to ensure long-term ecological and social benefits.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Oh, D.; Kim, D. A Study on the Location of the Palace of Goryeo Dynasty Namgyung. J. Korean Mediev. Hist. Soc. 2022, 71, 234. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S. A study on the area of rear garden and its architectural dimension at Gyeongbok Palace constructed during King Gojong’s Reign. J. Archit. Inst. Korea Plan. Des. 2018, 24, 95–104. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://www.hani.co.kr/arti/culture/culture_general/1043929.html (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Available online: https://www.chosun.com/politics/politics_general/2022/05/24/DAIGOPLJVZDJHDG5Z74WET4O2Q/ (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Takva, Y.; Takva, C.; Illerisoy, Z. Sustainable Adaptive Reuse Strategy Evaluation for Cultural Heritage Buildings. IJBES 2023, 10, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grazuleviciute, I. Cultural Heritage in the Context of Sustainable Development. Environ. Res. Eng. Manag. 2006, 37, 74. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, H. A Study on the historical values of the changes of forest and the major old big trees in Gyeongbokgung Palace’s back garden. J. Korean Inst. Tradit. Landsc. Archit. 2022, 40, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, W. Cheong Wa Dae, History of Blue Tiled Roof House; Seoul Historiography Institute: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2023; pp. 186–187. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, B.S. Memoirs of Yoon Bo Sun, Days of Solitary Decisions, Fight of Democracy; Dong-Ah Ilbo Publications: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Roh, T. Roh Tae-Woo’s Memoirs; Chosonilbo Publications: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2011; Volume 2, pp. 114–121. [Google Scholar]

- Presidential Security Office. Construction History of the Blue House Seoul; Presidential Security Office: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Presidential Security Office. Opening of Precincts (Blue House); Record No. 1A2076165222054; Presidential Archives of Korea: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Choi, J.; Choi, J.H. A Study on the Changes in the Back Garden of Gyeongbokgung Palace during Cheong Wa Dae Period through an Interview with Landscape Manager. J. Korean Inst. Tradit. Landsc. Archit. 2023, 41, 26–34. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.S. Memoirs of the President; Chosonilbo Publications: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2001; Volume 1, pp. 51–65. [Google Scholar]

- Presidential Security Office. Opening of Precincts (Blue House); Record No. 1A1070616522205; Presidential Archives of Korea: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S. Cheong Wa Dae, The Story of the Blue Tile Roof House; Seoul Historiography Institute: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2023; pp. 175–183. [Google Scholar]

- Presidential Security Office. Main Building Construction Budget Report; Record No. 1A10725165618412; Presidential Archives of Korea: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Blue House. Review of Improvements to Blue House Tour Program (Draft); Record Number 1A10617112402777; Blue House: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2000; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Presidential Secretariat. Review of Cheong Wa Dae Main Building Renovation; Record Number 1A00622094720099; Presidential Secretariat: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2002; p. 80. [Google Scholar]

- Cheong Wa Dae. Press Release, Cheong Wa Dae Sarangchae, Newly Renovated to Align with Park Geun-hye Administrations’ Policy Direction; Record Number 1015025100000238; Cheong Wa Dae: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2013; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Cheong Wa Dae. Press Release—Opening of Cheong Wa Dae Sarangchae Happiness Nuri Hall; Record Number 1015025100000270; Cheong Wa Dae: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2013; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://dailian.co.kr/news/view/1318585 (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Summarized from Cheong Wa Dae official Website. Available online: https://www.opencheongwadae.kr/eng/festival/eventList (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Seo, Y.; Chun, M.; Kim, H. City Marketing Strategy using City Identities-Focusing on the Application of Modern Architecture. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2010, 10, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, B.S. The Thorny Path of National Salvation; Seoul History of Political Affairs: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Roh, T. President Roh Tae-Woo’s Speeches; Speech at the Completion Ceremony of the New Main Building of the Blue House on 4 September; Samhwa Printing Company: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 1991; Volume 4, pp. 454–456. [Google Scholar]

- Seoul Historiography Institute. The Blue House, the History of the Blue Tile House; Historiography Institute: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, C.K. Meeting with Cheong Wa Dae; Now Everyon’e Place, Wisdom House: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2022; pp. 43–45. [Google Scholar]

- The Dong-A Ilbo. National Newspaper, 28 December 1978.

- Lee, S. History and Culture of Cheong Wa Dae and It’s Vicinities Series 10; ChoongAng Monthly: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Baik, S. Everything About the Blue House Through Photos and Historical Materials; Arachne: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, I. A study on the expressiveness of interior designs shown in Korea’s Presidential residence and Office. Korean Inst. Inter. Des. J. 2006, 15, 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Cultural Heritage Administration. Press Release—Two Months Since Cheong Wa Dae’s Opening, Visitor Satisfaction Rated Positively at 89.1%; Cultural Heritage Administration: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Janhonen-Abruquah, H.; Topp, J.; Posti-Ahokas, H. Educating Professionals for Sustainable Futures. Sustainability 2018, 10, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assmann, A. Cultural Memory and Western Civilization: Functions, Media, Archives; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011; (English Translation). [Google Scholar]

- Fadli, F.; AlSaeed, M. A Holistic Overview of Qatar’s (Built) Cultural Heritage; Towards an Integrated Sustainable Conservation Strategy. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

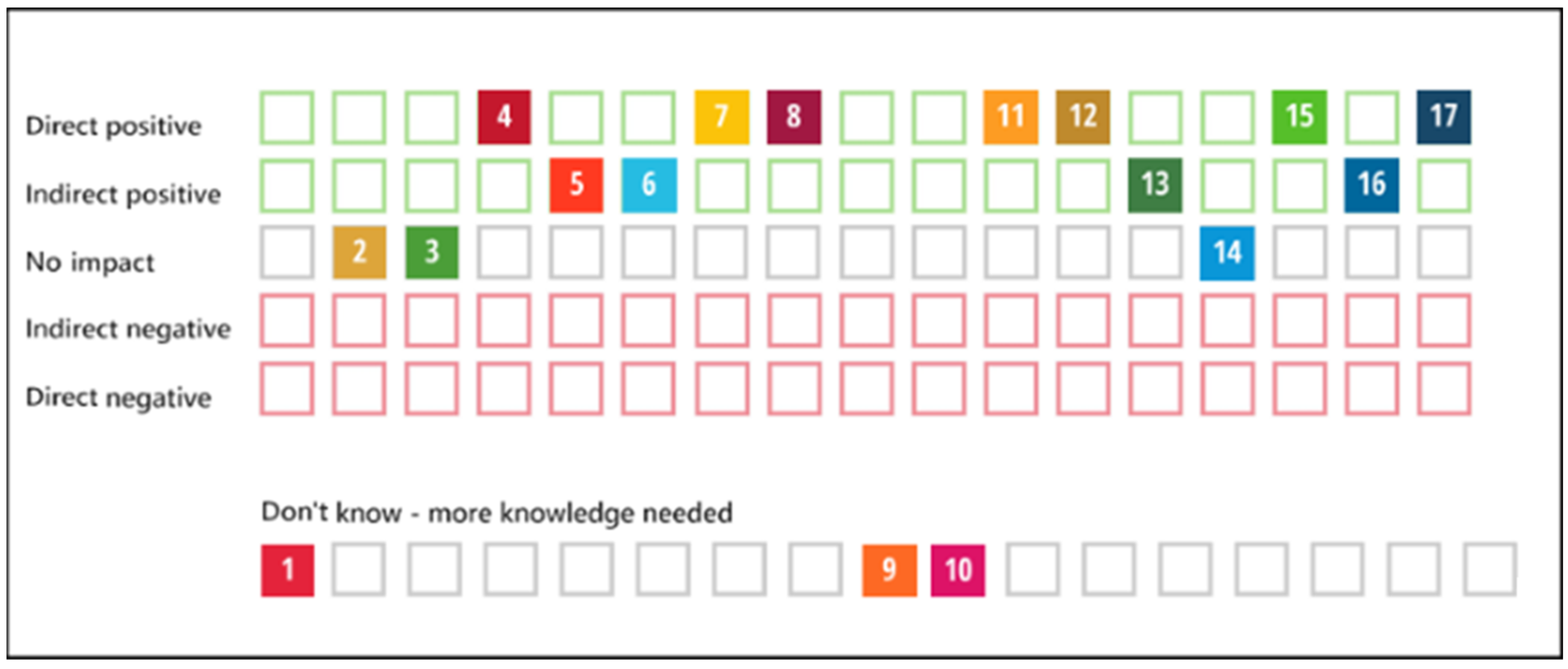

- Sustainable Impact Assessment Tool. Available online: https://sdgimpactassessmenttool.org/en-gb (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- Malpas, J. Place and Experience, A Philosophical Topography, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, P.H.; Lin, C.T. How should National Museums Create Competitive Advantage Following Changes in the Global Economic Environment? Environment? Sustainability 2018, 10, 3749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loach, K.; Rowley, J.; Griffiths, J. Cultural sustainability as a strategy for the survival of Museums and libraries. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2017, 23, 186–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Performances | Exhibitions | Educational Courses |

|---|---|---|

| 15 Seasonal Concerts | 7 Venue Hires | 3 History and Architecture |

| 1 Taekwondo Demo | 4 Trees and Forest 1 Venue Hire | |

| 6 Traditional Concerts 3 Night Tours 2 Venue Hires |

| Year | Number of Visitors (Per Year) | No. of Navigation Destination Entries | Cultural Tour (%) | Historical Tour (%) | Most Popular Destinations | Tourist Attractions of Interest |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 141,843,568 | 2,373,156 | 684,075 | 299,402 | Kyungbok Palace | Kyungbok Palace |

| (28.8%) | (12.6%) | MMA | Kyungkyojang (D) | |||

| Kwanghwamun | Bukchon Village Changduk Palace Insadong (I) | |||||

| 2020 | 104,020,835 | 2,239,689 | 588,564 (26.3%) | 225,969 (10.1%) | MMA Kwanghwamun (D) Kyungbok Palace (I) | Kyungbok Palace Donui Museum (D) Bukchon Village Changduk Palace (I) |

| 2021 | 107,124,443 | 2,697,643 | 679,127 (25.2%) | 305,496 (11.3%) | NMMA (D) Kyungbok Palace (I) | Kyungbok Palace Iksundong |

| Kwagnhwamun | Ground Seesaw | |||||

| 2022 | 130,160,538 | 3,275,565 | 826,406 | 415,075 | NMMA (D) Kyungbok Place (I) Kwanghwamun | Kyungbok Palace Iksundong Changduk Palace Insadong (I) |

| (25.2%) | (12.7%) | |||||

| CheongWaDae (I) | ||||||

| 2023 | 138,906,958 | 3,252,811 | 814,416 | 393,663 | Kyungbok Palace NMMA Kwanghwamun | Insadong Iksundong (D) Kyungbok Palace (I) Ground Seesaw CheongWaDae (I) |

| (25%) | (12.1%) | |||||

| Questions | Answers |

|---|---|

| Reasons for Visiting Cheong Wa Dae (Multiple Responses) | Curiosity about the President’s working space (36.9%) Because it is a viewing area being opened to the public for the first time (29.0%) Interest in its historical significance in connection with Gyeongbokgung Palace (11.8%) Interest in the surrounding natural environment, such as hiking trails (6.0%) |

| Future Directions for the Use and Management of Cheong Wa Dae (Multiple Responses) | Preserve its original form as it currently stands, reflecting the life and history of the President (40.9%) A modern historical and cultural space preserving the history and national heritage from the past to the present (22.4%) A new cultural and artistic space, such as a museum or exhibition hall (15.2%) |

| Priorities for the Management and Operation of Cheong Wa Dae | Prevention of damage and preservation of Cheong Wa Dae’s buildings, natural green spaces, and trees (64.3%) Operation of programs that highlight the historical significance and symbolism of Cheong Wa Dae (23.8%) |

| Education (Historical Significance) | Cultural Landmark | Experience of Culinary Tradition | Promotion of Sustainability | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Sustainability (SDGs: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 11, 16) | Learning from permanent and special exhibitions of past presidents’ lives and work and of key events of Korea’s democratic history | Learning from utilizing 253,505 m2 of landscape of Cheong Wa Dae, preservation and maintenance | Themed cooking classes (culinary culture of Cheong Wa Dae) | Ecological education programs (e.g., biodiversity of the site) Green initiatives |

| Environmental Sustainability (SDGs: 6, 7, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15) | Learning from global political events and issues | Utilizing 253,505 m2 as learning opportunity, hiking trails and tours | Themed cafe and restaurant with a cultural and historical narrative | Platform for energy saving and reuse and energy production initiatives |

| Economic Sustainability (SDGs: 8, 9, 10, 12) | Learning from global political events and issues | Venue for hosting high-profile summits and conferences | Food festivals: Global and local partnerships, attract more visitors | Adaptive reuse of the existing structures |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, J.-y.E.; Shim, Y.-h. Cheong Wa Dae: The Sustainability and Place-Making of a Cultural Landmark, Reflecting Its Role in History and Architecture. Buildings 2025, 15, 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15020155

Kim J-yE, Shim Y-h. Cheong Wa Dae: The Sustainability and Place-Making of a Cultural Landmark, Reflecting Its Role in History and Architecture. Buildings. 2025; 15(2):155. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15020155

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Ja-young Eunice, and Yong-hwan Shim. 2025. "Cheong Wa Dae: The Sustainability and Place-Making of a Cultural Landmark, Reflecting Its Role in History and Architecture" Buildings 15, no. 2: 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15020155

APA StyleKim, J.-y. E., & Shim, Y.-h. (2025). Cheong Wa Dae: The Sustainability and Place-Making of a Cultural Landmark, Reflecting Its Role in History and Architecture. Buildings, 15(2), 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15020155