1. Introduction

Match production in Turkey began during the late Ottoman Empire. The first (unsuccessful) attempt to build a factory was in 1875, followed by a similar failed venture in 1889 [

1]. Eight years later, French interests, which already had other businesses operating in the Ottoman Empire, received permission for another private venture, opening the first match factory in Küçükçekmece, Istanbul, in March 1897 [

2,

3]. However, the factory’s inability to compete with imported match prices and serious administrative issues between the company and the government led to the closure of the factory soon after [

1]. From the early twentieth century until the establishment of the Republic of Turkey on 29 October 1923, almost all of the country’s match needs were met by imports. In the summer of 1922, a private enterprise attempt was made at the local production level to establish the Keskin Match Factory in the Keskin district of Kırşehir Province [

2,

4]. Match production in this factory began in early 1923. The factory, which used domestically produced machinery and materials under primitive conditions, immediately faced financial issues that were initially addressed through state support. However, by late 1924, the factory’s operations were halted because its quality and profitability could not compete with imported products due to a state policy that encouraged match imports [

4].

In order to remedy this situation, in December 1924, the Turkish government signed an agreement with the Belgian company, the

Société Anonyme Usines Allumtière de Flandres (the Match Corporation and Factory of Flanders), granting it a 25-year partnership with the Republic of Turkey for match production [

2,

4,

5]. As part of this agreement, the Belgian company was also required to build a match factory within three years using a new financial partnership business model of Build–Operate–Transfer. Due to administrative issues, the construction of the factory in Sinop, a coastal city on the Black Sea, began in early 1927, with match production scheduled to start immediately after completion. However, a very important development occurred during this period: the majority of the Belgian shares were acquired by the International Match Corporation, owned by the Swedish “Match King” Ivar Kreuger, as part of his global monopolization efforts [

2,

4]. In 1928, all of the Belgian shares were formally transferred to the American–Turkish Investment Corporation (ATIC), a subsidiary of International Match. In June 1928, the Turkish government terminated its partnership with the

Société Anonyme Usines Allumtière de Flandres due to their failure to build a factory in Sinop in a timely manner and the inability to start match production. This termination allowed Kreuger’s official entry into the Turkish market.

The construction of the factory in Sinop, which began in 1927 and was expected to be completed within a year, was still unfinished by 1929. The biggest obstacle was a technical one: problems with ground slippage and settlement. In other words, the wrong choice of location, with the resulting structural damage preventing the factory from being placed into operation [

5]. Consequently, the Turkish government decided that match production had to continue at a new location with a new partnership model. Thus, Kreuger signed a new 25-year contract with the Republic of Turkey to turn the failure in Sinop into a success in Büyükdere, Istanbul. According to this contract, he was given rights to build, operate, and set prices for the factory in exchange for a

$10 million USD loan (approximately

$3 billion USD in 2025) paid to the Republic of Turkey. Kreuger’s monopolization activities were thereby implemented in Turkey through the Büyükdere Match Factory, established in 1932.

This article will focus on the Büyükdere Match Factory, extending the findings of previous studies [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5], which have predominantly been in Turkish and have centered on the financial framework and historical development of the factory, by investigating its engineering solutions, production line, work conditions, and technology transfer. The location of the structure will be evaluated from a logistical perspective; the positive and negative contributions of an American-based investment firm to the Turkish economy will be examined; and the current state of the structure and its change over time will be assessed. Moreover, this study will analyze the engineering aspects of the Büyükdere Match Factory from the late 1920s to the late 1930s, and will consider the economic impact of the

$10 million USD loan, as it was a pivotal financial parameter in creating a local and global monopoly in the region. This article will also focus on the technological innovation and expertise that was deployed to build a one-of-a-kind modern, semi-automated factory. In short, the Büyükdere Match Factory serves as a case study that examines what Turkey gained and lost from the establishment and production processes of a modern industrial factory, supported by US–Turkish collaboration, and equipped with the most advanced manufacturing and engineering technologies of the time.

2. Match Making and Ivar Kreuger

Ivar Kreuger (1880–1932) was born in Sweden into a family that owned two small match factories. His family’s match business led him to become deeply involved in this industry and in finance, ultimately becoming a global tycoon in the 1920s. However, his professional life began as a mechanical and civil engineer in Sweden. After working on various construction projects in the United States, he returned to his native country and established Kreuger & Toll with business associate Paul Toll. They specialized in construction using the Kahn method (a technology that required the use of steel bars with concrete), with which Kreuger had become familiar in the US. Within a few years, Kreuger & Toll had become one of the leading construction companies in Sweden. During this time, he was also involved in the preparation and financing of domestic and international building projects, establishing contacts with Sweden’s leading financial institutions and beyond. It was through these connections that he entered the match industry in earnest, using his family’s factories as a springboard towards world domination [

2].

The match-making business was historically a profitable industry in Sweden. In fact, by 1870, the country was already exporting nearly 6000 tons of matches each year. This export volume increased to 16,000 tons by the early 1900s. In 1913, exports reached 35,000 tons, and by 1930, they were at 50,000 tons per year [

6]. In 1917, Kreuger purchased 60,000 shares in the Swedish Match Company, a conglomerate of Swedish match factories that included the country’s largest firms (Jönköpings-Vulcan Match Manufacturing Company and the United Swedish Match Factories Corporation) as well as the Kreuger family’s small match factories in Kalmar, Mönsterås, and Fredriksdal. Then, he became its first CEO, with the intention of increasing profits.

Kreuger’s deep knowledge of engineering and finance through match-making business made him a very important global actor in this field. Leveraging considerable credit from Swedish banks, he initially gained control of numerous foreign match factories under very favorable agreements during the post-World War I era. He recognized the limitations of the Swedish money market and strategically sought access to the vast capital pools in the United Kingdom and the United States between 1922 and 1924. His successful flotation of stocks, debentures, and bonds provided the necessary funds for the continued consolidation of his ventures. Kreuger employed a similar strategy to tap into the capital markets of the Netherlands, Switzerland, France, and Germany. This allowed a significant enterprise, which started with purely Swedish funds, to expand worldwide by strategically employing foreign capital at each stage of its advancement. Thus, he secured virtually unlimited international credit, largely due to the strong reputation of the Swedish safety match, which served as an exceptional form of endorsement.

Matches were a favored source of public revenue and often a state-controlled industry in many European countries. Kreuger’s Swedish Match Company used this to offer substantial loans to nations needing immediate capital, targeting their match industries in the process by seeking concessions for the monopoly of match production, or sales, or both. This strategy benefited both parties: countries received immediate funds and, in most cases, saw increased revenue from match taxes, while the Swedish Match expanded its control. Over the course of the 1920s, the company had secured agreements with most countries in Europe and South America. The construction of factories in Sweden and beyond was managed by the Kreuger & Toll Company, further empowering Kreuger’s investments [

6].

In the early 1930s, the Swedish Match Company provided a total of nearly

$253 million USD in loans to the following countries (in millions of USD): Germany, 125 (with 50 due on 30 August 1930, and the remaining 75 due on 29 May 1931); France, 75; Hungary, 36; Romania, 30; Yugoslavia, 22; Turkey, 10; Poland, 6; Latvia, 6; Lithuania, 6; Greece, 4.86; Ecuador, 2; Bolivia, 2; Estonia, 1.88; and the Free City of Danzig (now in Poland), 1. However, the company’s assets extended beyond monopoly-backed loans to include significant holdings of other government bonds, notably French ones, alongside real estate shares, mortgage bonds, and similar securities in both Sweden and Germany. Furthermore, it maintained considerable interests in a range of banks situated in Sweden, Germany, France, Poland, Switzerland, and the Netherlands. Among its most important known assets were its stock ownership in the Graengesberg Company, Sweden’s largest ore producer, and in the prominent Swedish Woodpulp Company [

2,

6].

While the Swedish Match Company encountered significant competition from large American companies and smaller rivals elsewhere, a key competitor was the Soviet-Russian State Match Monopoly. Despite efforts to create strong international competition, the Russian endeavor appeared to have limited impact. To exert more pressure, the Soviets imposed an embargo on poplar wood exports, the sole suitable wood for match production. Nevertheless, Swedish Match remained unaffected, having already gained control of all poplar wood resources in Estonia and Latvia through their monopoly agreements in those nations [

7]. Countries such as India, Australia, and Egypt took steps to minimize the Swedish Match Company’s influence, for instance, by enforcing extremely high protective tariffs (up to 200 percent) on their products. To overcome these trade barriers, the company established its own factories in these countries. This allowed them to profit from the high tariffs, as their greater experience gave them a competitive edge over local manufacturers. In 1929, just before the New York Stock Market Crash, Kreuger’s total estimated wealth was around

$630 million USD (approximately

$190 billion USD in 2025) [

2,

6].

3. The Establishment of the Büyükdere Match Factory in Istanbul

After World War I, Turkey, like many other European countries, was trying to meet a large part of its match needs through imports. By 1925, the country’s match demands were primarily supplied through imports from European countries and the USSR. A major decision was made in May 1926 to make the city of Sinop, located on the north shore of Turkey facing the Black Sea, as the new headquarters for match production. For this purpose, foreign experts, particularly Belgians, were consulted regarding the establishment of a new factory, which had the goal of mass production within two to three years of its construction. However, match production never came to fruition due to structural failures and building damage resulting from significant foundation settlements caused by the self-weight and dynamic loading of the machines operating in the factory during the trial operations [

8]. The failure occurred because rigorous soil testing did not take place: testing parameters still had not been defined and there were narrow time constraints on the project.

Nevertheless, the failed factory did not discourage Turkey from making another attempt. In May 1929, the Turkish Grand National Assembly (TGNA or TBMM in Turkish) decided that it would be in the country’s interest to produce matches in a factory in Turkey rather than trying to import them again. The original factory planned for Sinop would be moved to a new location and its machines would be supplemented with the latest equipment purchased mostly from Europe. In order to make this new factory a reality, a series of government steps had to be taken. As part of these efforts, in the June 1930 TGNA session, it was announced that the match production business would be granted to the US-based American–Turkish Investment Corporation in exchange for a

$10 million USD loan. The concession would be for 25 years, starting on 1 July 1930 [

9,

10] (pp. 147–148). The agreement stipulated that at the end of the 25-year period, all rights would be transferred back to the Turkish Government (a typical Build–Operate–Transfer business model) [

11]. Based on the agreement between Kreuger’s firm and the Turkish Government’s delegates, the factory would start producing matches in mid-1932 [

2].

The construction of the match factory began in Büyükdere, Sarıyer, Istanbul, in May 1931, and was completed as planned in January 1932. However, many other locations were considered before its location in Büyükdere was finalized. Some of these locations included Fenerbahçe, Kadıköy, and Kartal, all towns in Istanbul [

12]. Other cities such as Sinop, Bursa, and Izmit were also considered [

13,

14]. However, the location in Büyükdere had many advantages: (a) there was already a brewery on the premises, so the infrastructure was readily available; (b) Ezba Forest, located nearby, offered an abundant source of drinking water, making the site an excellent choice for future factory workers; (c) the location offered easy access to a nearby Bosphorus-facing dock, enabling the crucial use of sea transportation; (d) the neighborhood already had other factories, dating back to the late 1800s and early 1900s; and (e) the neighborhood’s inhabitants were considered a promising source for potential workers [

15].

The fact that the structural damage caused by past earthquakes in the region had minimal to no impact was another determining key factor in the selection of the factory’s location. No official earthquake regulations existed in Turkey during the early 1930s when the factory was constructed. The country’s first official earthquake regulation was adopted in 1940 after the 1939 Erzincan earthquake, with a 7.8 magnitude, claiming close to 33,000 lives, and leaving 100,000 injured and 250,000 homeless. Nevertheless, it is possible that the design of the factory structures relied on foreign-sourced books and their Turkish translations. Moreover, it most likely included earthquake safety measures such as the use of structural steel (due to its ability to withstand deformation resulting from cyclic lateral forces), diagonal braces (to stabilize the entire structure), and RC grade beams to tie the continuous footings, thereby ensuring an effective lateral load transfer mechanism [

16,

17].

Match production in Büyükdere began in April 1932. It was projected that if the factory operated in three shifts, the annual production capacity would be sufficient to meet Turkey’s needs for four years. The factory planned to employ approximately 300 Turkish workers. According to the contract between the US and Turkish delegates, a limited number of foreign experts, not exceeding 10, could be employed to undertake technical tasks and managerial positions at the factory. With its cutting-edge equipment, the factory was among the top match factories in Europe at the time.

4. The Layout and Setting of the Büyükdere Match Factory

The image below shows the current location of the Büyükdere Match Factory (

Figure 1). The factory is located in the Sarıyer district, on the European side of Istanbul province. In the detailed aerial view of the factory (colored in red), the proximity of the area to the Bosphorus and the existing Büyükdere pier is noteworthy.

Figure 2 illustrates the site plan of the match factory during the late 1940s. In this site plan, the facilities and buildings are marked with different colors according to their intended use. The core area indicated in red represents the match production regions, while the structures shown in green indicate storage areas. Other colors and their usage areas are specified in the legend for the image below. Two buildings were used for lodging; one was constructed using brick masonry (lodging for the general manager), the other was timber (lodging for office clerks). Some of the buildings and structures within the factory premises were made of wood, some were made of stone and brick masonry, and others were constructed using reinforced concrete (RC) and steel.

In Turkey at the time, a match factory was a highly lucrative business. Therefore, the business had to be carried out by educated, well-trained experts, preferably with international experience. Ultimately, the factory’s profitability was the key indicator of a sound investment. In order to achieve this goal, extensive research was conducted regarding Turkey’s current and projected match needs. Based on this research, the profitability of the investment was studied to determine the factory’s optimum capacity. In 1931, Turkey consumed 21,864 crates of matches, totaling approximately 5.5 billion individual matches, which equates to roughly 400 matches per person per year, or slightly more than 1 match per person per day. This consumption rate was significantly lower than the European average of around eight matches per person per day. In 1931, roughly 3.1 billion cigarettes were consumed in Turkey, equaling about 2200 cigarettes per person per year, or 6 cigarettes per person per day. The factory management anticipated that match consumption would increase once the factory reached full operational capacity because in many parts of Turkey, particularly in villages, matches were split into quarters using razor blades due to their high cost [

19]. Therefore, once supply increased, cost would decline, increasing demand. Even if matches were solely produced to meet cigarette consumption, production would have to be doubled, indicating that profitability was a reality [

20].

The Büyükdere Match Factory used machines from the old factory in Sinop and supplemented them with new, automated equipment from Europe [

21]. The construction of the factory was completed in mid-January 1931, followed by machine installation under European engineers’ supervision. Installation was completed in late November, with trial operations beginning in late December. Match production at the Büyükdere Match Factory involved four distinct stages: In the first stage, match heads were applied to the matchsticks using “continuous-operation machines.” During the second stage, the matches were placed into crates. In the third stage, the matches were filled into boxes by machines, and during the fourth and final stage, the matchboxes were sent to packaging [

10] (pp. 322–323). Annual match production was initially projected as 25,000 crates, or the equivalent of 125 million match boxes (or roughly 13.4 billion individual match sticks). With this production capacity, the factory was expected to meet Turkey’s match needs for at least 1.5 years.

The chemicals needed for match production were imported from Europe because they were unavailable in Turkey. Similarly, timber was also imported, as local timber was mostly unsuitable for match production and had limited availability. The match factory commenced production in March 1932, supplying 75 to 80% of Turkey’s domestic demand. The factory anticipated a production surplus within its first month of operation, with the extra product intended for export to Balkan countries [

22,

23]. The factory initially employed 300 workers: 210 men and 90 women, and produced half a million match boxes per day, exceeding the projected production value of 0.35 million match boxes [

24].

5. Soil Investigation of the Büyükdere Match Factory Site

It is important to emphasize the accurate determination of soil characteristics in the Büyükdere region since soil settlement due to the weight and operating frequencies of the factory machines contributed to the structural failure of the first structure built in Sinop. The presence of an existing complex (the Nectar Beer Factory) in the Büyükdere area, with no indication of soil settlement, was a positive sign. However, even greater attention had to be paid to the soil investigation of the new match factory structures. To this end, the Department of Civil Engineering at Yüksek Mühendis Mektebi (today Istanbul Technical University) conducted a soil study at the site, utilizing the only advanced soil laboratory in Turkey at the time [

25,

26].

Büyükdere’s soil types and characteristics were well known, even in the late nineteenth century, due to the existing factories in the region. In a 1963 document, the following information was provided for the soil in the region. In Büyükdere, near the shore, a soil type called balçık (clayey soil), which was a mixture of clay, silt, and sand, was dominant. Due to the characteristics of the soil, it was found to be the most suitable material for brickmaking. Therefore, approximately 50 brick manufacturing factories were established in the region between the late 1800s and the mid-1900s. The existence of this clayey soil type near the coastal areas indicated that an alluvial soil type was dominant in the region. However, as one moves away from the coast and begins to ascend towards the hills, the Thrace Formation begins to emerge as a geological formation [

18].

The soil type of the factory site can also be easily determined through a geological formation study of the region where the match factory is located. However, since no detailed study of the region is available for the 1930s, the geological map from the 1950s will be used with the current map to examine the soil properties in detail. In the figure below, a close-up view of Istanbul’s 1950 geological map is given along with the location of the match factory (

Figure 3). As shown in the legend, the match factory was in an area where a mixture of clay, schist, and graywacke types of soil was predominant. In the 2025 map of the General Directorate of Mineral Research and Exploration (or MTA in Turkish), the area is characterized by the Flis Permo–Carboniferous and Paleogene Volcanic formation. Another soil study, dated to 2011 and provided by the Directorate of the Investigation of Earthquake and Soil of Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality, confirms the previous findings, stating that the geological formation in the area was the Thracian Formation [

27]. The soil type in the Thracian Formation is black dark gray, light brown when weathered, thin-medium layered, with abundant mica flakes, a turbiditic sandstone-shale alternation, locally with conglomerate lenses, rare limestone lenses, and interbeds in its upper sections. This soil has a safe (allowable) bearing capacity of 150 kN/m

2 to 200 kN/m

2. In the case of the match factory, a soil bearing capacity within this range of magnitude permits traditional footings with no pile requirements [

28].

Based on another soil study pertaining to the area which was conducted in 2013, the following observations were made. Beneath the 1.5 to 3.0 m of fill layer, there was a greenish-brown, gravelly sandy–silty clay layer with a thickness of 10.00 to 20.00 m. The average Standard Penetration Test (SPT) N30 value in the near-surface portions of this layer was in the order of 5. On the southeast side of the site, in boreholes drilled at relatively lower elevations, a fractured and jointed sandstone–claystone–siltstone alternation belonging to the Thrace Formation, with clay infill in the fractures and joints, was observed beneath the sandy–silty clay layer (see

Figure 2 for the site layout). Although there was no groundwater on the site, surface water was encountered. As a result of the field and laboratory studies conducted, it was concluded that the site had (a) a loose fill layer with low strength and poor compaction, ranging in thickness from 1.5 to 3.0 m, (b) beneath the fill layer, there was a soft clay layer with low strength parameters and an average thickness of 6.0–7.0 m, based on SPT N30 values, (c) below the clay layer, there was a very stiff to hard clay layer with a thickness ranging from 5.0 to 13.0 m, and finally, (d) at deeper elevations, the presence of sandstone–siltstone–claystone was observed. It is clear that the results of this detailed soil investigation confirm the findings of the previous studies from the 1950s.

The photos below were taken in 2015 and show the excavation and piles of the site during the construction of a state hospital that replaced the buildings and structures of the match factory (

Figure 4). The building on the left-hand side of the first photo is the old Nectar Beer Factory.

6. Construction Details and Working Conditions at the Büyükdere Match Factory

This section will include information read from visuals pertaining to the factory’s employees and its structural design. The reason these photos were used as primary sources instead of technical documents is as follows. During the data collection process, the ultimate goal was to find technical drawings, construction details, and engineering and architectural layouts and calculations. To this end, local archives were investigated thoroughly. Journals published at the time, as well as nearly all Turkish and English newspapers, were also examined in great detail. Open-source materials and archives in the United States were also included in this investigation. Those who held managerial positions at the factory were researched separately in an attempt to gain access to more technical information. However, very few of these efforts yielded technical details or information because the sources are no longer extant. Therefore, the authors decided to assess the structures and their construction details from an engineering perspective using the photographs below, many of which have never been previously published. These findings provide a more comprehensive analysis of the historical and technical details of the factory site, distinguishing this study from previous research.

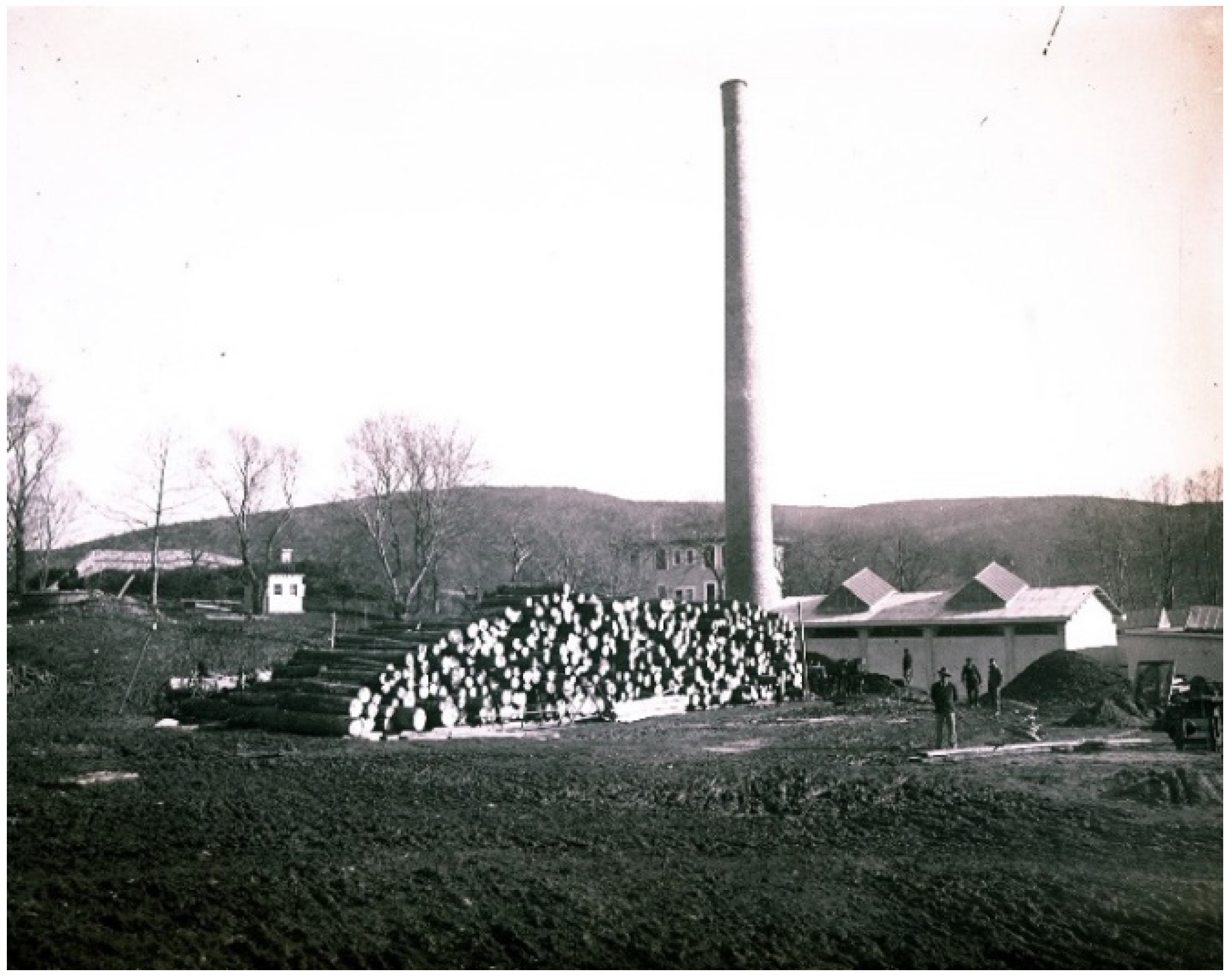

Figure 5 shows a general view of the factory taken from the southwest. The building visible in the foreground is the Nectar Beer Factory (see

Figure 2 for the layout of the factory). The Nectar Beer Factory, a structure within the Büyükdere Match Factory complex, was established in 1909 and was in operation for only 3 years. Between 1912 and 1940, the main building was used solely for malt production. Afterwards, it served as a warehouse [

31] (p. 18). The beer factory building consisted of load-bearing walls made of brick masonry, reinforced concrete (RC) columns, and one-way ribbed RC slabs, along with RC slabs supported by closely spaced I-shaped steel sections [

31] (p. 89). Based on photographs of the building, it is believed that the foundation was made from continuous footing supported laterally by slab-on-grade RC beams. The single-story structures with sloping roofs located in front of the Nectar Beer Factory were factory storage areas. The main structures and a functioning chimney belonging to the match production facility were situated behind the beer factory building. Hundreds of stacked logs next to the production facility are also noticeable. Although the photograph’s date is unknown, given the military uniform in the foreground and the factory’s active production state, the photograph’s estimated date is circa the mid to late 1930s.

The two images below display the general overview of the factory in the late 1990s (

Figure 6). The picture on the left presents the match production factory facilities and the factory chimney. On the right, the structures in the foreground (left) are the match production factory facilities, while the larger structure in the back is the old Nectar Beer building. It is important to note that older photos showing parts of the factory layout were not included in this article due to their extremely poor quality.

The drawings below provide the details of the match factory structure where production took place. The match factory structure was constructed using both RC and steel materials. The entire roof of the structure had metal decks supported by either single steel sections or trusses made of steel sections (

Figure 7).

The image below shows a portion of the survey drawing of the Büyükdere Match Factory from September 1990 (

Figure 8). This section of the image also includes structural design drawings of the manufacturing plant facility. In the upper-left section of the image, the exterior walls of the partitioned rooms, with a thickness of 40 cm and RC square-shaped columns with dimensions of 55 cm by 55 cm, placed approximately 5 m apart horizontally and about 6.5 m apart vertically, are visible. The bottom left corner of the drawing consists of the boiler room, electrical room, bathroom, and toilets. On the left interior parts of the drawing, built-up columns made of two UNP steel sections, spaced 4 to 6 m horizontally and 6 to 8 m vertically, are noticeable. These columns are supported by steel beams made of INP sections or steel trusses with top and bottom chords made of two INP sections. These structural sections are applied uniformly throughout the entire manufacturing facility. Thus, a wider and unobstructed work area was created in the manufacturing area by using steel columns and beams.

A review of archival documents from the factory’s construction period reveals that, unfortunately, no visuals of the foundation, excavation, and construction phases are available. However, some images were found in (mostly defunct) newspapers and magazines. The poor quality of these visuals prevented their use in this article. Only one relatively clear image was discovered showing the factory’s construction phase. The image below depicts the roof construction of the Büyükdere Match Factory’s main building. As displayed in the image, the sloped roof was constructed using a trapezoidal metal deck supported by either steel sections or trusses made of steel sections (

Figure 9).

Figure 10 dates from the mid-1930s and shows the manufacturing buildings and the factory chimney. In front of the chimney, logs stacked for match production are seen. Additionally, sand screening equipment and formwork materials for other ongoing construction work (such as retaining walls) within the site are also visible. As evident in the image, the roofs were constructed using a trapezoidal metal deck. Additionally, glass sections placed along the roof, which enabled the use of abundant natural light in the match making area, are noticeable. The use of corbelled reinforced concrete columns is visible along the exterior façades of the manufacturing buildings. These types of corbelled columns facilitated the installation and use of cranes and similar machinery in the manufacturing area.

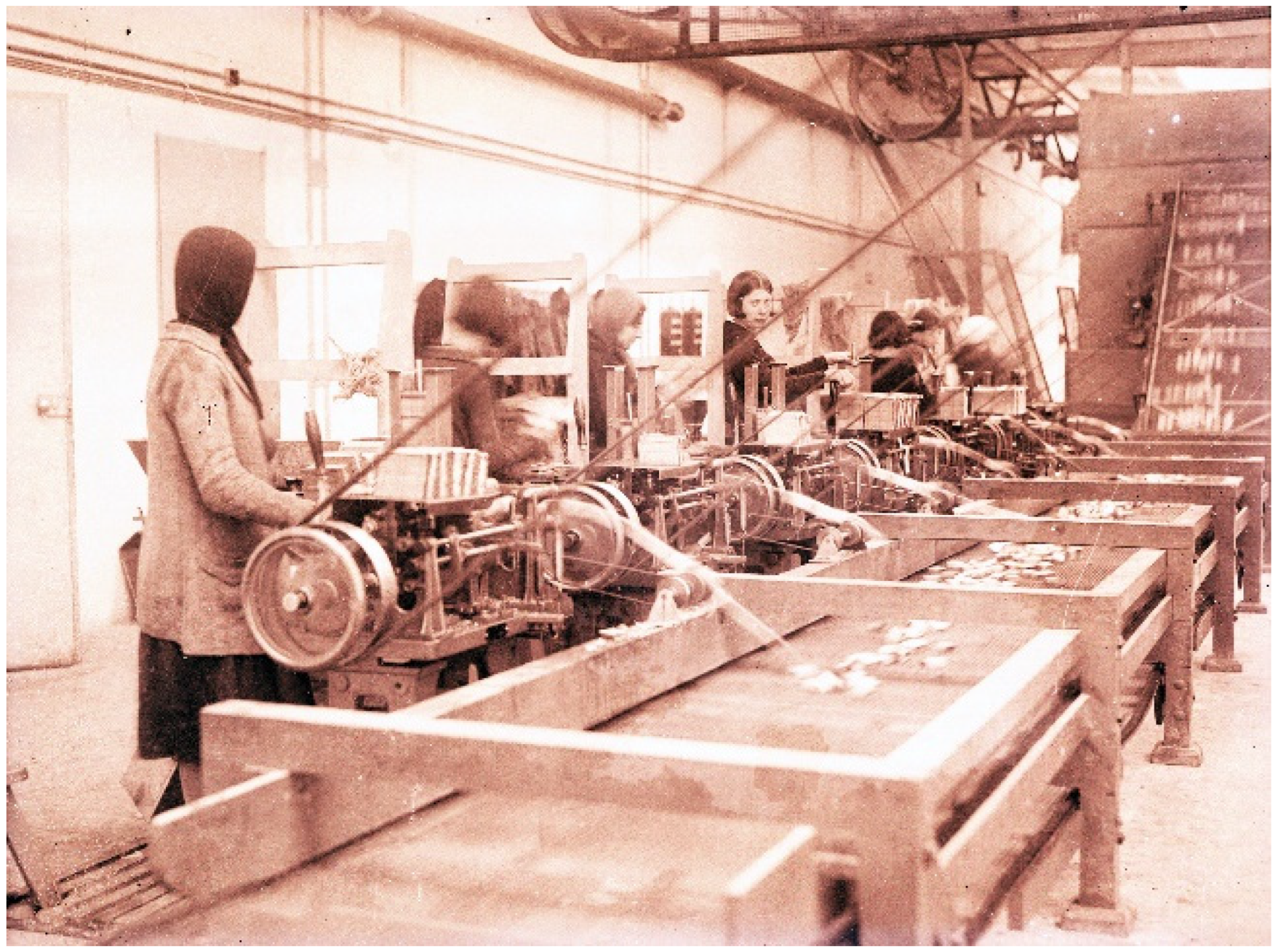

The image below depicts female workers involved in match production at the Büyükdere Match Factory (

Figure 11). The wide spans in the work area and the built-up columns made of steel angles in the middle of the spans are noteworthy. The exterior walls of the building, visible in the background of the image, were constructed with corbelled columns joined with infill walls.

The picture below also displays female workers at the Match Factory (

Figure 12). Based on the photo, it is evident that the manufacturing process was suitable for semi-automation. Additionally, crane-type machinery equipment mounted on the beams connecting the corbelled columns within the work area can be seen. The image shows that the necessary electrical cable channels for the optimum usability of the work area were carried via electrical trays mounted on the ceiling. The exterior columns and the built-up steel columns in the middle of the spans formed the main load-bearing system of the structure.

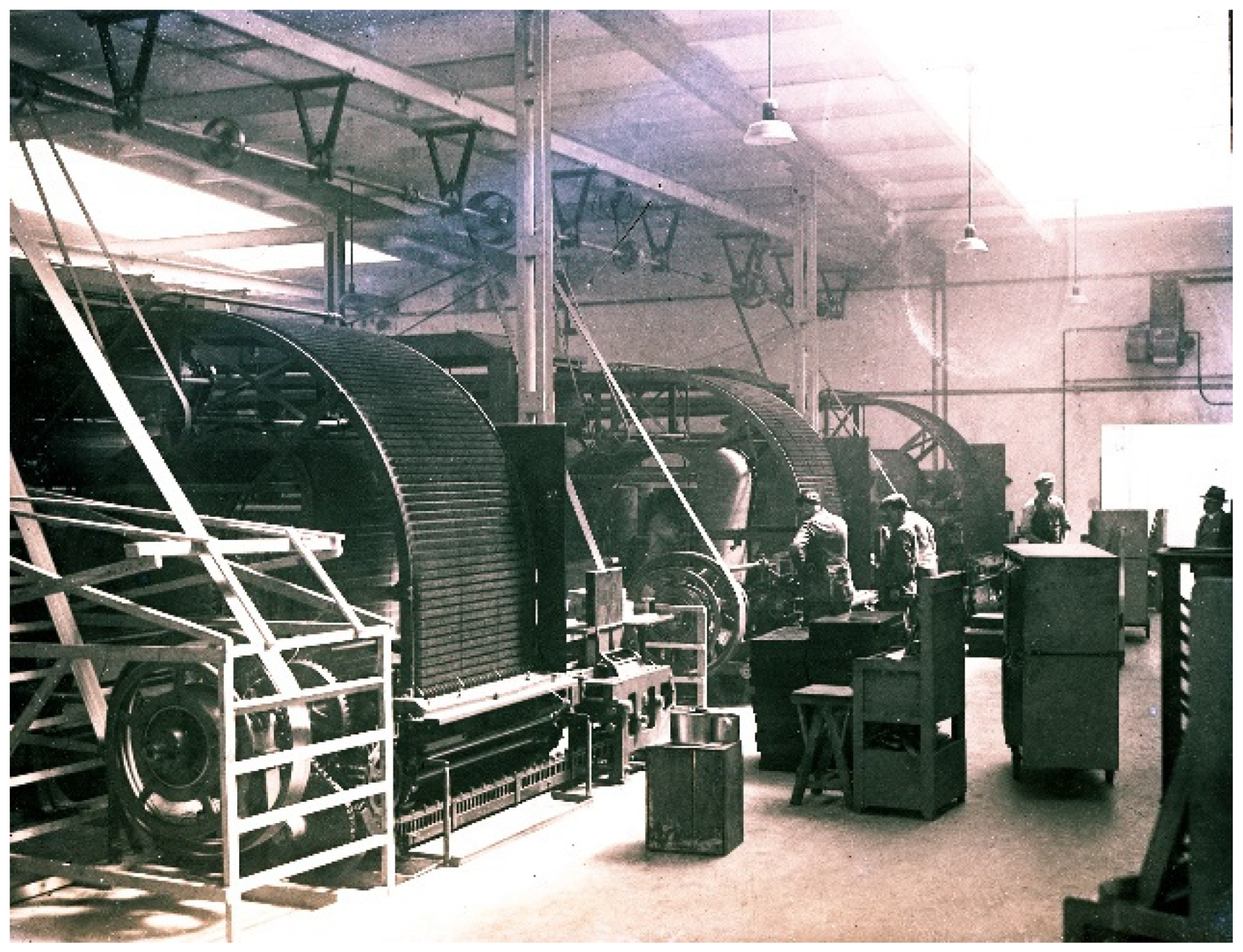

Figure 13, again from the inside of the factory, shows male workers. Based on the machines operating on this production line, it is clear that the manufacturing process for matches was semi-automated. The mechanical equipment for heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) was mounted on the ceiling for unobstructed, easy access to the work area. The building appears to be supported by RC columns and girders along the exterior façade, and by built-up steel columns in the middle of the spans. As stated before, the roof was made of trapezoidal metal deck and was supported by I-shaped steel sections. Glass sections placed along the roof enabled the use of abundant natural light in the match-making area.

The image below shows male workers at the Büyükdere Match Factory (

Figure 14). Considering the type of equipment present in this work area, it is evident that repairs of the machines operating in the factory were almost carried out entirely in this shop.

In the image below, wooden crates containing matchboxes are seen in the depot of the Büyükdere Match Factory (

Figure 15). The abbreviation B.K.F. on the crates stands for “Büyükdere Kibrit Fabrikası” (Büyükdere Match Factory). The roof of the storage area is made of trapezoidal sheet metal supported by trusses formed using steel angles. Additionally, a glass section for natural lighting is placed in the center of the roof truss. The match crates are located on the reinforced concrete floor (or a slab-on-grade type flooring system) that spanned the two continuous footings under the RC columns at the left and right ends of the roof trusses and the partition walls joining them.

7. Weighing the Pros and Cons of the Matchmaking Business in Istanbul

The Büyükdere Match Factory, like any new manufacturing business, faced significant challenges in its early years, including various production, operation, and management issues. Some of these were typical problems that any factory might face, while others were unique to Büyükdere. For example, workplace accidents at the factory were specifically reported in newspapers due to the factory’s importance. The issue of setting the price of matches within the monopoly framework also highlighted a serious problem with the factory’s operation. In fact, this topic was even discussed at the Turkish Grand National Assembly. Another issue reported was that the factory’s machines sometimes miscounted the matchsticks during the packaging process. This issue was likewise mentioned in newspaper articles and was a subject of discussion at the TGNA. A production line problem required importing wood for the matchsticks. Turkey did not have enough of the right kind of wood for matches, and there always seemed to be a shortage. In addition to these issues, the factory also faced some management problems. Foreign managers were often biased and accusatory toward Turkish employees. This was reported in newspapers and in some cases, even led to legal action. However, this article will not provide a detailed discussion of these issues since they are beyond the scope of this study. The authors are preparing a more comprehensive article on these topics [

41].

Fortunately, the factory’s structural design and ground characteristics did not exhibit the same issues as its predecessor in Sinop. Both the private sector and Yüksek Mühendis Mektebi (Istanbul Technical University) carefully addressed the soil matter, and the necessary technical studies were completed using the technology available at the time. The overall structural performance of the Nectar Beer Factory, built on the same site decades before the match factory, indicated that its location was indeed a good choice.

The match factory had a number of positive impacts on the region, summarized as follows:

- (a)

It reduced the local unemployment rate and increased migration to and interest in the area.

- (b)

It created a new social group that grew up with factory culture, leading to cultural change among the local residents.

- (c)

In the 1950s, it helped pave the way for the establishment of other new match factories in the region funded by the private sector.

- (d)

It became an important industrial symbol in a developing, modern Turkey.

- (e)

It served as a significant example of the kinds of financial partnerships and business management systems that could exist in Turkey.

- (f)

By instilling the idea and necessity of domestic production, it pioneered the establishment of other public and private factories that would promote local resources and import substitution [

42].

- (g)

As a project that emphasized the use of technology and international collaboration, it illustrated what could and could not be accomplished through transnational partnerships [

25,

43,

44,

45].

8. Conclusions

This article discussed the establishment and engineering of the Büyükdere Match Factory, which began production in Istanbul’s Sarıyer district in April 1932. It covered the events that transpired during the process and provided insight from an engineering perspective. The article briefly touched upon the global match production monopoly created by the “Match King,” Ivar Kreuger, a Swedish civil and mechanical engineer, and the events that unfolded during the formation of his worldwide factory system.

The first match factory in modern Turkey, built by a Belgian company in the city of Sinop in the Black Sea region in 1929, ceased production before it even began due to permanent structural damage caused by sudden and time-dependent ground settlement. This failure necessitated the careful selection of a new factory location and meticulous engineering for the next project. Therefore, this article also provided information on the selection of the factory site, the determination of soil properties, building design processes, and working conditions.

The establishment of the Büyükdere factory was officially sealed with an agreement signed in June 1930 between ATIC and the Republic of Turkey. The factory, which began its production in April 1932, was the first in Turkey to use semi-automation with up-to-date equipment and carefully orchestrated production lines. It was not profitable in its early years, mainly due to the difficulties related to the adaptation of local needs and state policy. The factory’s first profitable year was 1935, approximately three years after it began production. However, continuing administrative problems, revolving mostly around the factory’s operation and Ivar Kreuger’s suicide in March 1932, caused the partnership to proceed with progressive difficulty. The fallout of the 1929 New York Stock Market crash, the ensuing global depression, and World War II certainly did not help matters, catalyzing the serious upheaval of the partnership. When the Turkish government’s expectations regarding match production, price determination, and profit margins were not fully met, inevitable disagreements arose between the parties. Consequently, the contract was terminated in May 1943, and the facility, along with all its equipment, was handed over to the Republic of Turkey.

After May 1943, the Büyükdere Match Factory was used as a factory and storage area for the Turkish State Monopolies Enterprise. In 1989, it was decided that the factory, along with its contents, would be moved to another location: İnegöl, Bursa [

26]. The majority of the factory’s buildings and structures were demolished in 2012 and replaced by a large state hospital, Sarıyer Devlet Hastanesi, which would house 450 patients. The groundbreaking of this hospital took place in January 2013 [

46]. As a result, only a few buildings were left intact on the site (none of which were the match factory structures).

Figure 16 features two photos of the site: the image on the left was taken in 2010; the image on the right was taken right after the excavation of the Sarıyer State Hospital in 2014.

At the time one of Europe’s most modern match production facilities, the Büyükdere Match Factory is still significant for what it can teach us about the costs and benefits of such transnational collaborations. This study examined the establishment of the match industry in Turkey through a case study of the Büyükdere Match Factory, specifically by focusing on its engineering aspects. The construction process of the factory, which served as a model for future manufacturing installations in Turkey, was explained and illustrated. However, there are still numerous areas for future research, including the specific role that Ivar Kreuger played in the Büyükdere factory, his emphasis on technological innovation as a civil engineer and a formidable force in global business and finance, and the politics and diplomacy involved in such large-scale construction projects. The authors plan on addressing these topics in a forthcoming publication [

41].