Safeguarding the Memory of Cultural Heritage: Protection and Restoration Strategies for Dong Village Settlement Architecture

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Overview

1.2. Research Method

1.2.1. Literature Research Method

1.2.2. Case Analysis Method

1.2.3. Field Survey Method

2. Overview of Dong Village Settlement Characteristics and Analysis of Cultural Value

2.1. Historical Development of Dong Settlements

2.2. Spatial Layout Characteristics of Dong Villages

2.2.1. Geographical Distribution: “Nestled Against Mountains and Beside Waters”

2.2.2. Village Layout

2.2.3. The Extreme Emphasis on Public Activity Spaces Under the Spatial Evolution Oriented by Public Activities

2.2.4. Road Distribution

2.3. Architectural Form Characteristics and Material Craftsmanship

2.3.1. Wind-and-Rain Bridges

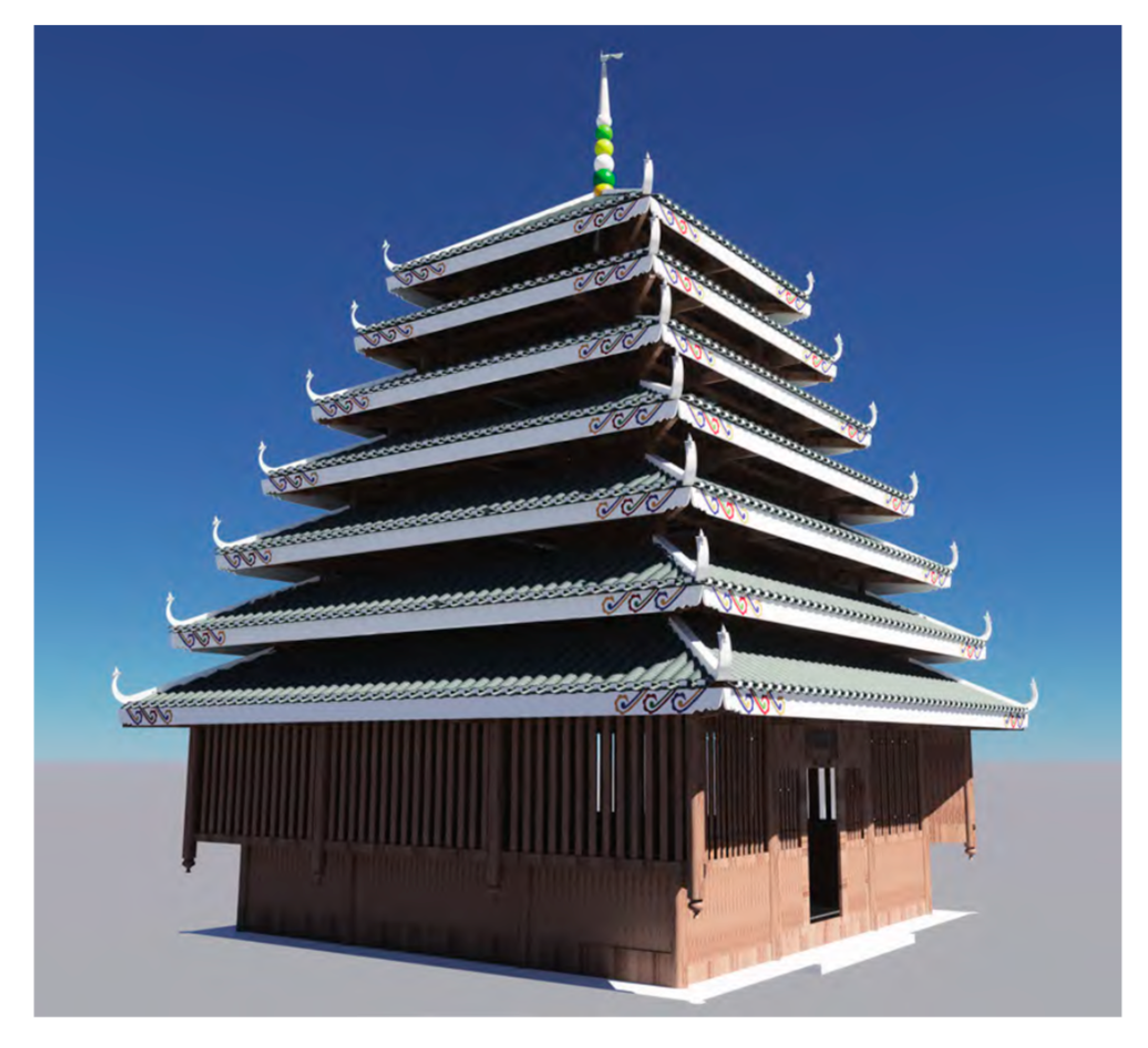

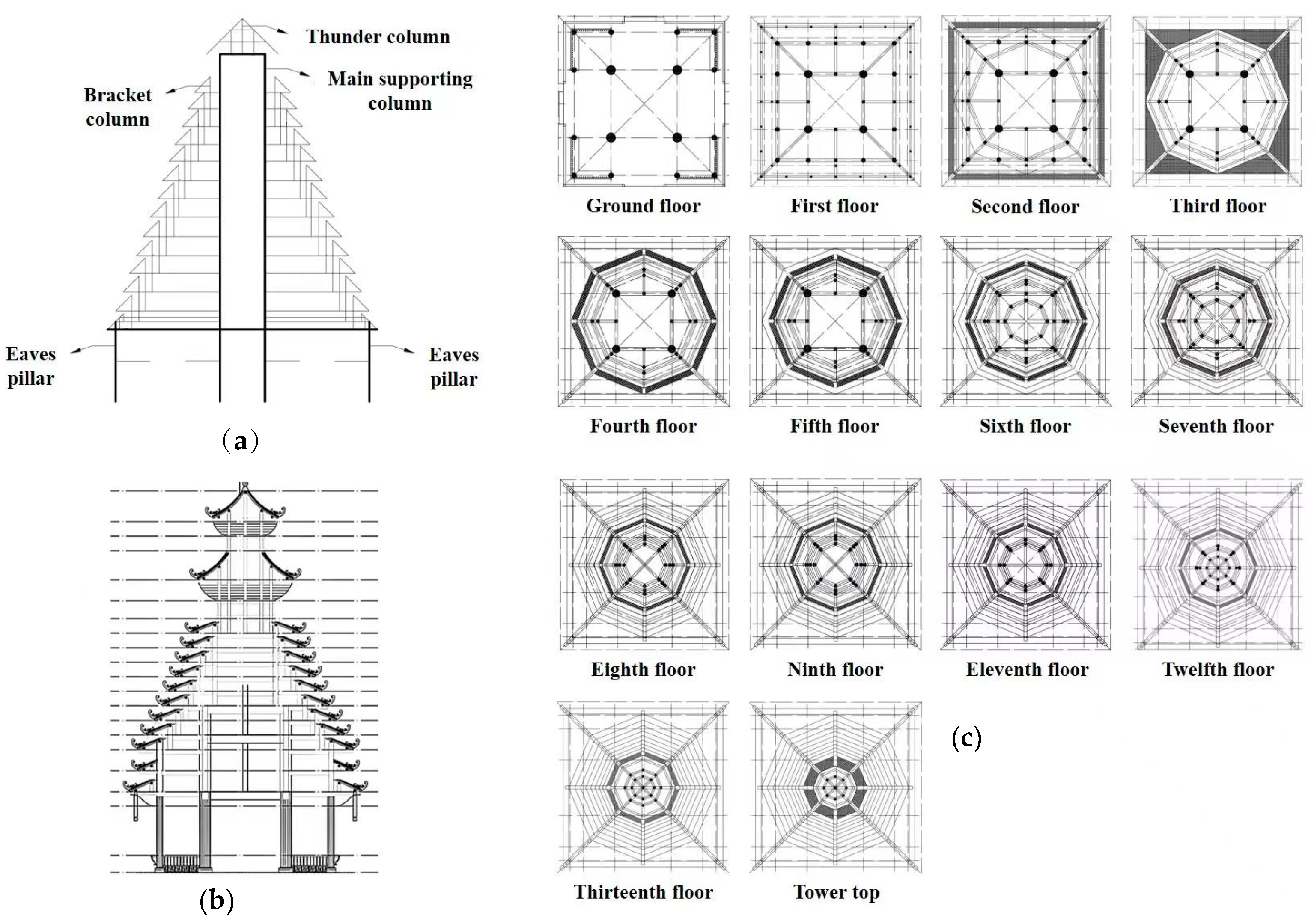

2.3.2. Drum Towers

2.3.3. Dong Dwellings

2.4. Analysis of Dong Village Cultural Value

3. The Dilemmas and Challenges of Protecting the Architectural Heritage of Dong Village Settlements

3.1. The Impact of the Transformation of Local Residents’ Lifestyles Brought About by Urbanization and Historical Context

3.1.1. Population Reduction in Villages Due to Urbanization

3.1.2. The Transformation of Lifestyle Due to Modernization and Villagers’ Pursuit of Improving Their Quality of Life

3.2. The Contradiction Between Tourism Development and Authenticity Preservation

3.3. Limitations in Inheriting Traditional Architectural Techniques

4. Discussion on Material-Level Protection and Restoration Strategies for Dong Village Settlement Architecture

4.1. Elaboration of Relevant Protection and Restoration Theories and Principles

4.2. Settlement-Wide Protection Planning Strategies Based on Traditional Dong Public Activity Needs

4.2.1. Prioritizing Improvement in Residents’ Quality of Life and Production

4.2.2. Integral Protection Strategy

4.2.3. Make Full Use of the Original Customs and Lifestyles of the Settlement and Create Conditions to Promote Their Continuation

4.3. Adaptive Renewal and Reuse of Buildings and Modernization of the Translation of Design Schemes

4.4. Technical Restoration Strategies

4.4.1. Fire and Corrosion Prevention Treatment of Buildings

4.4.2. Structural Reinforcement

4.5. Digital Technology Intervention

5. Safeguard Mechanisms for Dong Village Settlement Protection and Restoration

5.1. Hierarchical Protection System

5.2. Establishing an Academic Database of Dong Architectural Techniques

5.3. Promoting Resident Participation and Empowering Decision-Making

5.4. Establishing a “Cross-Regional Collaborative Protection Mechanism”

6. Conclusions and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaur, M.; Selvakumar, P.; Dinesh, N.; Mohit; Chandel, P.S.; Manjunath, T.C. Reconstruction and Preservation Strategies for Cultural Heritage. In Preserving Cultural Heritage in Post-Disaster Urban Renewal; Oflazoglu, S., Dora, M., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 385–412. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. The World Heritage List: Filling the Gaps—An Action Plan for the Future; International Council on Monuments and Sites/UNESCO World Heritage Centre: Paris, France, 2005; Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/document/102409 (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. World Heritage in Danger. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/danger/ (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- International Council on Monuments and Sites. The Venice Charter: International Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites. 1964. Available online: https://admin.icomos.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Venice_Charter_EN.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Kodeboyina, G.B. Sustainable Strategies for Monument Protection—A Panoramic View of the Possibilities and Pitfalls. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1149, 012003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökmen Erdoğan, B. An Evaluation of Contemporary Additions to Refunctioned Architectural Heritage. In Theories, Techniques, Strategies for Spatial Planners and Designers: Planning, Design, Applications; Özyavuz, M., Ed.; Peter Lang Publishing Group: Bern, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 601–616. [Google Scholar]

- Formolly, A.; Saraei, M.H. Socio-Cultural Transformations in Modernity and Household Patterns: A Study on Local Traditions Housing and the Impact and Evolution of Vernacular Architecture in Yazd, Iran. City Territ. Archit. 2024, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranajaya, I.K.; Dewi, N.M.E.N. Composite Material Engineering Analysis Based on Circular Economy for the Conservation of Interior Ornaments and Traditional Balinese Architecture. Int. J. Eng. Sci. Inf. Technol. 2025, 5, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunxuan, W.; Ruika, Y.; Ibrahim, N.L.B.N. From Traditional to Modern: Cultural Integration and Innovation in Sustainable Architectural Design Education. J. Ecohumanism 2025, 4, 2079–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abyaa, Z.; El Harrouni, K.; Degron, R.; Aljem, S. From Disintegration to Valorization: What Perspectives and Multi-Scale Approaches towards a Sustainable Territorial Design for the Architecture of Kasbahs and Ksour in Southern Morocco? Mater. Res. Proc. 2025, 47, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shri Harine, K.; Narendran, N.; Jothilakshmy, N. Chettinad Vernacular Architecture—A Sustainable Paradigm of Modern Design Challenges. In Proceedings of the 2024 9th International Conference on Applying New Technology in Green Buildings (ATiGB), Danang, Vietnam, 30–31 August 2024; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 518–524. [Google Scholar]

- El Moussaoui, M. Architectural Typology and Its Influence on Authentic Living. Buildings 2024, 14, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samalavičius, A. Traditional Architecture: Displacement and Return. Logos Lith. 2022, 111, 149–156. [Google Scholar]

- Lemja, C.-A. Re-Affirmation of Traditional Values of Space for the Sake of Healthier Manner of Life—Analysis of Traditional and Modern Materials, Their Influence to the Human Health and Giving Directions for Future Actions in the Materialization of Contemporary Facilities. HealthMED 2010, 4, 175–186. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, T.E.; Bui, H.T.; Ando, K. Zoning for World Heritage Sites: Dual Dilemmas in Development and Demographics. Tour. Geogr. 2022, 24, 33–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.T.; Ha Son, B.; Nguyen, N.V.; Van Vo, T. Challenges in conservation of architectural heritage and tourism development in urban areas: A case study in ho chi minh city, vietnam. In Dynamics of Heritage Management and Tourism Development: Trends, Practices, and Approaches; Srivastava, S., Kulshrestha, R., Eds.; Apple Academic Press: Palm Bay, FL, USA, 2025; pp. 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardani, G. Reducing the Loss of Built Heritage in Areas of Tourist Interest. In Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; Volume 26, pp. 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China. Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Cultural Relics, Enacted by the National Congress of China (First Enacted in 1982, Revised in 2017). 1982. Available online: https://english.court.gov.cn/2015-07/17/c_761516_3.htm (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Feng, J. The Dilemmas and Prospects of Traditional Villages: With a Discussion on Traditional Villages as Another Category of Cultural Heritage. Folk Culture Forum 2013, 4, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, L. Traditional Villages and Architecture in Dong Ethnic Group Settlements; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Shi, L.; Liu, S.; Shi, J.; Ma, Q.; Zhang, J. Climate Adaptability Based on Indoor Physical Environment of Traditional Dwelling in North Dong Areas, China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J. A Study on the Characteristics of Traditional Culture of the Dong People in Southern China; Nationalities Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Chi, F.; Wei, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, S.; Xu, H. An Intelligent Modeling Method for Protecting and Inheriting the Construction Techniques of Wooden Stilt Buildings. Buildings 2025, 15, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Meng, A. Challenges and Breakthroughs: A Field Investigation into the Migrant Labour Economy in Ethnic Minority Villages. Heilongjiang Natl. J. 2010, 6, 63–67. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Zhao, X.; Gao, Z. Research on the Intangible Cultural Heritage Inheritance and Innovation Protection Path of Dong Wooden Building Construction Skills: A Case Study of Sanjiang Dong Autonomous County. Comp. Res. Cult. Innov. 2024, 8, 66–70. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, P. Restoration Risks of Traditional Vernacular Heritage Houses in China. Territorio 2023, 105, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretto, P.W.; Cai, L. Village Prototypes: A Survival Strategy for Chinese Minority Rural Villages. J. Archit. 2020, 25, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.Y.; Bai, Y.; Xie, K. Regional Adaptive and Eco Sustainable Revitalization of Hui Ethnic Village: Traditional Dewelling Design Practices in Western China. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2025, 1500, 012066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rautio, S. Material compromises in the planning of a “traditional village” in Southwest China. Soc. Anal. 2021, 65, 67–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compilation Group of A Brief History of the Dong People. A Brief History of the Dong People; Guizhou Ethnic Publishing House: Guiyang, China, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z. An Analysis of Settlement and Architectural Layout Characteristics of Dong Villages in Southeast Guizhou. Guizhou Ethn. Stud. 2009, 29, 85–89. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, G. Public Spaces and Villagers’ Public Life in Dong Villages. J. Cent. Univ. Natl. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2013, 40, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S. Regeneration and Preservation Practice on Dong Minority Gaobu Village of Hunan, China. In Proceedings of the 2018 World Multidisciplinary Civil Engineering-Architecture-Urban Planning Symposium, Prague, Czech Republic, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 604–613. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, S. The Origin of Dong Drum Towers and Wind and Rain Bridges. Guangxi Ethn. Stud. 1995, 03, 86–97. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, W. Cultural Changes and Social Functions of Dong Drum Tower Architectural Art. J. Staff. Work. Univ. 2018, 01, 42–46. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H. A Micro-Exploration of the Aesthetics of Dong Village Architectural Design in Sanjiang, Guangxi. Mod. Anc. Lit. Creat. 2024, 11, 88–90. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, K. A Brief Analysis of the Development and Evolution of the Architectural Form of Dong Ethnic Minority Residential Buildings in Sanjiang, Guangxi. Brick Tile 2022, 59–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J. A Brief Analysis of Ecological Design in Dong Ethnic Group’s Stilted Houses: A Case Study of Chengyang Ba Zhai in Sanjiang Dong Autonomous County, Liuzhou City, Guangxi. Guangxi Urban Constr. 2024, 54–60. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, N.; Rössler, M.; Tricaud, P.-M. (Eds.) World Heritage Cultural Landscapes: A Handbook for Conservation and Management; UNESCO World Heritage Centre: Paris, France, 2009; Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/documents/publi_wh_papers_26_en.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- ICOMOS. Evaluations of Nominations of Cultural and Mixed Properties, 24 June–4 July 2018); International Council on Monuments and Sites/UNESCO: Paris, France, 2018; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000264530 (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- National Bureau of Statistics. Seventh National Population Census Bulletin (No. 2) (R); National Bureau of Statistics: Beijing, China, 2021.

- Li, D.; Chen, S.; Wei, S.; Hu, F.; Huang, L.; Shi, Z. Reflections on Protection and Development of Wooden Architecture in Sanjiang Dong Autonomous County, Guangxi. Sichuan Archit. 2025, 45, 26–27+32. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Zhang, Y. Application of Digital Technology in the Conservation of Ancient Buildings: A Case Study of the Dong Drum Tower in Sanjiang, Guangxi. Resid. Technol. 2023, 43, 57–60. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W. Research on the Inheritance and Renewal of Traditional Wooden Architecture in Famous Tourist Villages (Zhai) in the Central and Northern Parts of Guangxi—Taking Chengyang Eight Villages in Sanjiang Dong Autonomous County as an Example. Dewllinghouse 2022, 16, 21–24+28. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, H. Study on Integral Protection of Architectural Heritage in Dong Settlements in Southwest Hunan. Ph.D. Thesis, Hunan University, Changsha, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y. On the Characteristics and Development Principles of Ethnic Village Tourism. J. Southeast Guizhou Natl. Teach. Coll. 2025, 6, 60–62. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C. Research on the Synergy Between Ethnic Village Tourism Development and Rural Revitalisation. J. Southwest Univ. Natl. (Humanit. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2022, 43, 199–204. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Q. The Inheritance and Protection of Traditional Crafts from the Perspective of Intangible Cultural Heritage: A Case Study of the Dong Ethnic Group’s Wooden Architecture Construction Techniques. J. Xuzhou Inst. Technol. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2014, 29, 89–94. [Google Scholar]

- International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS). The Athens Charter for the Restoration of Historic Monuments. 1931. Available online: https://civvih.icomos.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/The-Athens-Charter_1931.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS). Charter for the Conservation of Historic Towns and Urban Areas (Washington Charter). 1987. Available online: https://admin.icomos.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/towns_e.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS). The Nara Document on Authenticity. 1994. Available online: https://www.iccrom.org/sites/default/files/publications/2020-05/convern8_06_thenaradocu_ing.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention; World Heritage Centre: Paris, France, 2023; Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/guidelines/ (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Zhu, Y. Authenticity and Heritage Conservation in China: Translation, Interpretation and Practices. In Authenticity in Architectural Heritage Conservation: Discourses, Opinions, Experiences in Europe, South and East Asia; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Housing and Urban—Rural Development. Basic Requirements for the Compilation of Traditional Village Protection and Development Planning (Trial). 2013. Available online: https://hnjs.henan.gov.cn/2019/10-21/1148029.html (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Zhou, J. Traditional Chinese Villages: Protection and Development; China Construction Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S. Traditional Villages as Human Settlement Forms and Their Integral Protection. Urban Plan. Forum 2017, 2, 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S. Introduction to the Protection of Historic Cities: A Holistic Approach to Cultural Heritage and Historic Environment Protection; Shanghai Science and Technology Press: Shanghai, China, 2001; pp. 110–120. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J. Research on New Public Building Design in Dong Villages Under Rural Revitalization. Ph.D. Thesis, Guangxi University for Nationalities, Nanning, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Turkušić, E. Neo-vernacular architecture—Contribution to the research on revival of vernacular heritage through modern architectural design. Importance of Place. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Hazards and Modern Heritage, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 13–16 June 2011; pp. 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G. The “Protection” of the Dong Village in Guizhou Province: A Case Study of Drum Towers and Wind-and-Rain Bridges. Archit. J. 2016, 12, 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, L. Research on Renovation Design Practice of Rural Homestays. Ph.D. Thesis, Northwest Minzu University, Lanzhou, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Q.; Wang, Y. Fire Safety Status and Fire Prevention Strategies of Ethnic Minority Architectures in Sanjiang Dong Village, Guangxi: A Case Study of Gaoxiu Village, Linxi Town, Sanjiang Dong Autonomous County, Guangxi. Today’s Fire Prot. 2023, 8, 7–9+48. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, F.; Chen, G. Protection and Research of Ancient Buildings; Intellectual Property Press: Beijing, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, X. Research on fire protection renovation technology for ancient wooden structures. Eng. Constr. Des. 2024, 10, 47–49. [Google Scholar]

- Du, F.; Okazaki, K. Fire-resistance improvement of vernacular timber architecture in a historical dong village in China: A case study in Dali. ICOMOS–Hefte Des Dtsch. Natl. 2018, 67, 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Frigione, M.; Lettieri, M.; Mecchi, A.M. Environmental effects on epoxy adhesives employed for restoration of historical buildings. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2006, 18, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. The Modern Continuation of the Structural Types and Construction Techniques of Dong Drum Towers in the Tongdao Pingtan River Basin. Ph.D. Thesis, Hunan University, Changsha, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, C.; Yi, S.; Liu, W. Research and Practice on Digital Inheritance and Protection of Sanjiang Dong Drum Towers. Guangxi Urban Constr. 2025, 04, 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, F.; Zou, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, Y. The Parametric Analysis of the Construction Rules of the Ethnic Dong’s Drum-Tower’s Wooden Frame Based on the Craftsmen’s Logic A Case Study of the Four-Eight Style Drum-Tower by Gaobu’s Ethnic Dong Craftsmen in Hunan Province, Hunan Province. Archit. J. 2024, 04, 72–77. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, W.; Gao, X.; Lu, J. Digital Construction Preservation Techniques of Endangered Heritage Architecture: A Detailed Reconstruction Process of the Dong Ethnicity Drum Tower (China). Drones 2024, 8, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ayala, D.; Wang, H. Conservation Practice of Chinese Timber Structures: ‘No Originality to Be Changed’ or ‘Conserve as Found’. J. Archit. Conserv. 2006, 12, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Hu, Y. The Production and Transmission of Intangible Cultural Landscape Genes in Traditional Villages: A Case Study of Huangdu Village, Tongdao Dong Autonomous County. Econ. Geogr. 2022, 42, 208–215. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L. Uses of Heritage, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, L.N.; Wu, M.Y.; Wall, G.; Zhou, Y. Community Support for Tourism in China’s Dong Ethnic Villages. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2019, 19, 362–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Li, H.; Furuya, K.; Chen, J.; Luo, S. Participatory intention and behavior in green cultural heritage conservation: An application of the extended theory of planned behavior. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Throsby, D. Economics and Culture; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X. Poverty alleviation, community participation, and the issue of scale in ethnic tourism in China. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2020, 46, 1923–1940. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, D.J.; Wiek, A.; Bergmann, M.; Stauffacher, M.; Martens, P.; Moll, P.; Swilling, M.; Thomas, C.J. Transdisciplinary research in sustainability science: Practice, principles, and challenges. Sustain. Sci. 2012, 7 (Suppl. 1), 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOMOS. International Charter for Cultural Heritage Tourism; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, K. Guangxi, Hunan, Guizhou Establish Joint Application Mechanism for Chinese Dong Villages. China Culture Daily, 24 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, L.; Pan, X.; Wang, X.; Zhou, H. Drum Towers Against Mountains and over Waters, Ancient Dong Villages in Southeastern Guizhou Province. In Traditional Chinese Villages; Springer: Singapore, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Augelli, F. Hunan’s Dong Minority Drum Tower: From Knowledge to Preservation. In Cultural Heritage Preservation for Vulnerable Territories; Augelli, F., Rigamonti, M., Eds.; Creativity, Heritage and the City; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Dong Villages. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/5813/ (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Yu, Y. The Existing Problems and Suggestions for the Ethnic Village Tourism: A Case Study of Dong Village in Zhaoxing. Commun. Humanit. Res. 2023, 4, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Qian, X.; Wen, Q. Stewardship of built vernacular heritage for local development: A field research in southwestern villages of China. Habitat Int. 2022, 129, 102665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Sulaiman, M.K.A.M.; Harun, N.Z. Safeguarding the Memory of Cultural Heritage: Protection and Restoration Strategies for Dong Village Settlement Architecture. Buildings 2025, 15, 3591. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15193591

Wang Y, Sulaiman MKAM, Harun NZ. Safeguarding the Memory of Cultural Heritage: Protection and Restoration Strategies for Dong Village Settlement Architecture. Buildings. 2025; 15(19):3591. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15193591

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yihan, Mohd Khairul Azhar Mat Sulaiman, and Nor Zalina Harun. 2025. "Safeguarding the Memory of Cultural Heritage: Protection and Restoration Strategies for Dong Village Settlement Architecture" Buildings 15, no. 19: 3591. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15193591

APA StyleWang, Y., Sulaiman, M. K. A. M., & Harun, N. Z. (2025). Safeguarding the Memory of Cultural Heritage: Protection and Restoration Strategies for Dong Village Settlement Architecture. Buildings, 15(19), 3591. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15193591