Cross-Cultural Perceptual Differences in the Symbolic Meanings of Chinese Architectural Heritage

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Construct a cultural symbolic system of traditional Chinese architecture;

- (2)

- Identify the perceptual preferences, emotional responses, and interpretive mechanisms among the three visitor groups;

- (3)

- Propose optimized strategies for the presentation and communication of architectural heritage tailored to multicultural audiences.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Selection

- (1)

- The sites are widely recognized as UNESCO World Heritage Sites that are familiar to both domestic and international visitors.

- (2)

- They represent the major architectural typologies and hold strong national cultural significance.

- (3)

- Each site has a sufficient volume of online data, with at least 5000 reviews available in both Chinese and non-Chinese platforms.

- (4)

- They reflect a balanced geographical distribution across northern, western, southern, and eastern China.

2.2. Tourist Group Classification

2.3. Data Collection and Processing

2.3.1. Interview Team

2.3.2. Interview Text Data

2.3.3. Online Textual Data

2.3.4. Data Preprocessing

2.4. Research Methods

2.4.1. Methodological Framework

2.4.2. Definition of Key Concepts

2.4.3. Literature Analysis

2.4.4. Perceptual Semantic Network Analysis

2.4.5. Textual Analysis

- (1)

- High-frequency word extraction.

- (2)

- Hierarchical coding of interview texts.

- Pre-analysis of high-frequency words: preliminary thematic lists were generated as a reference for sentence-level coding.

- Sentence-by-sentence hierarchical coding: interview sentences were independently subjected to open coding, axial coding, and selective coding, and the relationships among nodes were established [26].

- Validation of coding results: the coding framework was compared against the high-frequency word lists to ensure comprehensive coverage of architectural symbols.

- Cross-group theme validation: NVivo matrix coding was used to identify shared cross-cultural themes [27].

- Theoretical saturation test: checks were performed to identify whether any potential themes were left uncaptured across groups [28].

- (3)

- Online review analysis as a comparative dataset.

- (4)

- Cross-validation of themes.

2.4.6. Affective Quantitative Analysis

2.4.7. Ethics Statement

3. Results

3.1. The Construction of a Symbolic System of Chinese Architecture

3.1.1. Typological Classification of Chinese Architectural Symbols

3.1.2. Interpretive Framework of the Chinese Architectural Symbolic System

- (1)

- Primary Symbols: Lexicon

- (2)

- Primary Symbols: Syntax

- (3)

- Primary Symbols: Grammar

- (4)

- Primary Symbols: Discourse

3.2. Differences in Perceptual Semantic Networks

3.2.1. Construction of Perceptual Semantic Networks

3.2.2. Analysis of Perceptual Semantic Network Differences Among Three Groups

3.3. Differences in Perceptual Themes

3.3.1. Classification of Perceptual Themes

- (1)

- Open Coding: A line-by-line analysis of 1450 thematic sentences yielded 82 initial concepts related to architectural components (e.g., dougong [bracket sets], overhanging eaves), visual impressions (e.g., solemnity, vivid colors), institutional symbols (e.g., imperial power, ritual order), and spatial symbolism (e.g., central axis, symmetry). To ensure semantic coverage and conceptual saturation, separate researchers independently coded the transcripts for each tourist group, followed by cross-validation.

- (2)

- Axial Coding: The initial concepts were aggregated and compared, resulting in 19 intermediate categories such as cultural aesthetics, religious symbolism, social hierarchy, ethnic characteristics, and local memory. NVivo’s node–subnode functions were used to normalize semantics and clarify the relationships among categories.

- (3)

- Selective Coding: With the core category of “how tourists perceive and interpret architectural culture,” the 19 categories were integrated into six overarching first-level themes: aesthetic perception, scientific/productive perception, institutional/ritual perception, political/hierarchical perception, ethnic/local perception, and religious/ethical perception.

- (4)

- Saturation and Reliability Testing: Theoretical saturation was confirmed when the sixth group of interview transcripts (Nos. 51–60) produced no new categories over two consecutive rounds. Coding reliability was assessed by randomly selecting 30 transcripts, yielding a Kappa coefficient of 0.78, which indicates a high level of inter-coder consistency.

- (5)

- Integration with Online Reviews: To enhance cross-source consistency, Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) topic modeling was conducted on 1500 online review texts. LDA was selected because it enables unsupervised identification of latent topics from large-scale corpora, thereby reducing human bias and supplementing the interview-based findings. The online themes were relatively broad and superficial, such as ancient architecture and history, regional architectural characteristics, cultural heritage and rituals, imperial gardens, vernacular buildings, etc., among a total of nine themes. Rather than serving as an equal dataset, online reviews played a corroborative and supplementary role: (a) where themes overlapped, they reinforced the robustness of the interview-based categories; (b) where additional signals emerged, they were assessed for integration as potential supplements; and (c) importantly, no contradictory patterns were detected.

- (6)

- Final Theme Consolidation: Based on the interview framework and incorporating online validation, the six initial themes were refined into five stable and representative perceptual themes (Table 3).

- Aesthetic Perception

- Scientific/Productive Perception

- Institutional/Political Perception

- Ethnic/Local Perception

- Religious/Ethical Perception

- (7)

- Validity Testing: The Jaccard similarity coefficient between interview- and review-based themes was calculated at 0.68, indicating a moderate-to-high level of consistency. In social science research, this threshold is generally considered sufficient to support construct validity, confirming that the interview-derived thematic categories are both reliable and representative.

| Perception Type (Main Category) | Sub-Category | Conceptual Examples | Sample Quotes | Group Coding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aesthetic Perception | Exquisite ornamentation, Rigorous form, Spatial modulation | Aesthetic paradigm, Harmonious elegance | (Temple of Heaven) The Hall of Prayer for Good Harvests is truly beautiful. Whenever we introduce Chinese heritage tourism, it represents the aesthetic paradigm of traditional Chinese architecture (C1–12). (Summer Palace) It incorporates almost all the classic elements of Chinese gardens (C1–25). | C (170) A (130) UA (123) Key Sites: (3) (9) (10) (11) |

| Majestic scale, spatial rhythm, Graceful refinement | (The Forbidden City) It’s larger than the Grand Palace, but less intricate and lavish (A-17). (The Summer Palace) It’s huge, but truly beautiful. It’s different from the Katsura Imperial Villa in Kyoto (A-21). | |||

| Varied scenery, Delightful experiences | (Humble Administrator’s Garden) Sometimes it feels like standing on a cliff, other times like walking through blooming bushes—living here must have been incredibly romantic (UA-39). | |||

| Scientific/Productive Perception | Exquisite craftsmanship, Efficient tools, National strength | Architectural ingenuity | (The Forbidden City) How could such massive stones be crafted so smoothly? They almost don’t feel like stone anymore (C1-17). Such a towering and lengthy Great Wall—how many people and how much time did it take to build it? Truly remarkable (C2-27). | C (136) A (105) UA (98) Key Sites: (1) (3) (6) (8) |

| Massive scale, Monumental proportions | The scale of Xi’an Ancient City and the Forbidden City is overwhelming—unlike any urban form found in Southeast Asia (A-33). He unified China and built such a massive mausoleum with an immense underground palace for himself (A-49). | |||

| Majestic grandeur, Labor-intensive construction | (Xi’an) This is the largest ancient city I’ve ever seen—with towering walls, watchtowers, and such vast remains of royal palaces (UA-48). The Great Wall is a magnificent project. It still stands after all this time—truly incredible (UA-26). | |||

| Institutional/Political Perception | Supremacy of Imperial, Power Hierarchical, Authority Ritual Norms | Ritual sequence, Power appropriation | (Confucius Temple) From the main entrance, there are several gates and archways, with a long distance to the main hall. The hall is very tall—it shows how highly Confucius is regarded (C1–40). The Forbidden City is basically the emperor’s mansion. Ancient Chinese emperors made common people build these luxury residences for them (C2–13). | C (76) A (57) UA (49) Key Sites: (1) (3) (4) (6) (8) |

| Imperial rites, Status symbols | (Confucius Temple) Why does the Confucius Temple in Qufu look so much like the Forbidden City in Beijing? Wasn’t the dragon motif reserved only for emperors? (A-42) | |||

| Imperial symbolism | (Forbidden City) The emperor sits really high up. The dragon on the throne looks fierce—it makes the emperor seem really powerful (UA-29). | |||

| Ethnic/Local Perception | Clan-based Living, Cultural Ambience, Oriental Imagery | Clan settlement, Cultural ambience, Local livelihood | (Hongcun) Most villagers are related by blood. Close kinship families live together, and in a single house, family members occupy different rooms according to seniority (C1–52). (Humble Administrator’s Garden) We studied poems about Chinese gardens in literature class. She can truly feel the beauty in this space (C2–76). (Wuzhen) The small bridges, flowing water, and riverside markets shape the gentle temperament of Jiangnan people (C2–84). | C (112) A (84) UA (77) Key Sites: (2) (7) (10) (11) |

| Geographic adaptation, Waterborne commerce, Commercial prosperity | (Hongcun) The village looks like my hometown, but the houses are kind of different (A-57). (Wuzhen) Small boats carry goods in and out—that’s how this place became so prosperous. It reminds me of Damnoen Saduak in Bangkok (A-31). | |||

| Tranquility and harmony, Oriental scroll imagery, Ethnic diversity | (Hongcun) The alleys in the village are like a maze, and you can hear the stream beside them—it’s really pleasant (UA-48). (Wuzhen) People here live by the water and do business along the river. It feels like a medieval movie scene (UA-46). In Xi’an, there’s also a Muslim street like this. The food is delicious, and the Muslim vibe is very strong (UA-38). | |||

| Religious/ Ethical Perception | Moral Education, Fengshui principles, Nature Worship | Seeking immortality, Ancestral worship, Secluded upbringing | (Wudang Mountain) People come here to seek wisdom from the Wudang masters—and to enjoy the scenery. The Golden Hall is really high up; climbing there feels like a test (C1–87). (Hongcun) During the New Year, we return home and go to the ancestral hall together to honor our ancestors and pray for blessings (C1–76). (Hongcun) All the buildings are multi-story, and unmarried girls have to stay upstairs. They aren’t allowed to go out—I wonder how that affects their psychological development (C2–62)? | C (86) A (60) UA (43) Key Sites: (9) (4) (5) (7) |

| Moral instruction, Religious gardens, Feng shui concepts | (Tangyue Village) Japan also has something similar to pailou like torii, but not with this variety and meaning (A-41). (The Summer Palace) In Singapore, people also believe in Daoism and Buddhism, but we don’t really have gardens that are directly related to religion. This is quite interesting (A-38). (Hongcun) Does feng shui help keep people safe? Is it like the bodhisattvas in Buddhist temples (A-61)? | |||

| Moral exemplars, Nature worship, Longevity and health | (Tangyue Village) At first, I thought the pailou was built to honor warriors or generals. Turns out the real meaning was very different from what I imagined (UA-58). (Temple of Heaven) The ‘heaven’ worshipped in China—is it like a god that can’t be seen, or a god you can actually see? (UA-28) (Wudang Mountain) Many Europeans know about Chinese Daoism—especially how Taoist priests practice kung fu and rituals. It’s so mysterious, and they say it can lead to a longer life (UA-63). |

3.3.2. Analysis of Perceptual Differences in Architectural Symbols Among Three Groups

- (1)

- Aesthetic Perception

- (2)

- Scientific and Productive Perception

- (3)

- Institutional and Political Perception

- (4)

- Ethnic and Local Perception

- (5)

- Religious and Ethical Perception

- (6)

- Summary

3.4. Differences in Emotional Characteristics

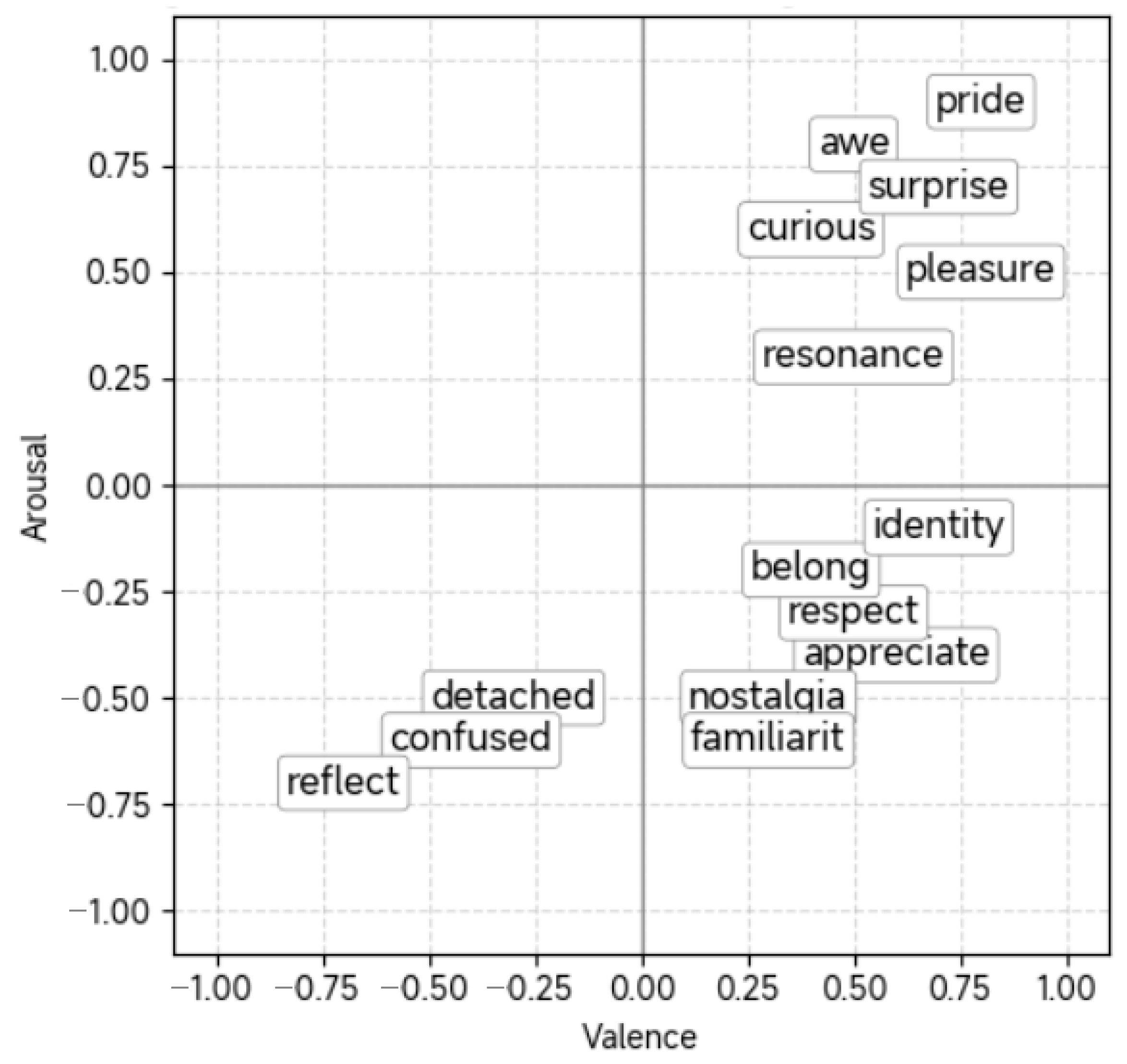

3.4.1. Extraction and Classification of Emotion Words

- (1)

- Affective Word Extraction

- (2)

- Affective Word Clustering and Visualization

- (3)

- Emotional Typology Matrix

3.4.2. Emotional Profile Differences

3.5. Differences in Perceptual Mechanisms

3.5.1. A Five-Stage Mechanism of Cross-Cultural Perception

3.5.2. Perceptual Mechanism Differences Among the Three Tourist Groups

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Contributions to Cross-Cultural Tourism Studies

- (1)

- Establishing a Cross-Cultural Perception Paradigm Based on the Semantic System of Architectural Symbols.

- (2)

- Highlighting the Key Role of Cultural Memory and Context in Shaping Perceptual Content.

- (3)

- Expanding the Emotional Response Model in Cross-Cultural Tourism Through Ideal Affect Theory.

- (4)

- Proposing a Five-Stage Micro-Mechanism Model for Architectural Perception.

4.2. Practical Strategies for Enhancing Cross-Cultural Visitor Experience

- Experience Optimization Pathways

- 2.

- Implementation Recommendations

- (1)

- Culturally Adaptive Heritage Curation:

- (2)

- Affective and Immersive Interpretation:

- (3)

- Targeted Interpretation Systems:

- (4)

- Integrative Cross-Cultural Platforms:

5. Conclusions

5.1. Main Findings

- (1)

- Memory Structure and Cultural Context Shape Primary Perception of Architectural Heritage.

- (2)

- Cultural Dimensions and Affective Orientations Drive Differentiated Emotional Responses.

- (3)

- Symbolic Interpretation Paths Exhibit Systematic Cross-Cultural Divergence.

5.2. Research Limitations and Future Directions

5.2.1. Research Limitations

5.2.2. Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Primary Symbol (4) | Secondary Symbol (14) | Tertiary Symbol (65) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Lexicon | 1-1 Materials (6) | 1-1-1 Wood: 1. Used for primary structural frameworks, detailed construction, and decorative elements. 2. Wood was abundant and locally sourced, making it easy to carve and paint. |

| 1-1-2 Earth: Used as both load-bearing and enclosing components (e.g., earthen platforms and walls), as well as a binding agent for bricks and stones. It also serves as the base material for brick and tile production. | ||

| 1-1-3 Brick and Stone: Functioning as structural, enclosing, and decorative elements, bricks and stones are central to Chinese architecture. Brick carving and stone carving are among its most distinctive artistic features. | ||

| 1-1-4 Tile: Including round tiles, glazed tiles, and decorative eave-end tiles (wadang). Tiles function both as weatherproof cladding and as decorative surfaces. | ||

| 1-1-5 Paint: Originally applied for material protection and later increasingly for decorative purposes. Solid-color paints—bright, vivid, and saturated—conveyed nobility; for example, yellow-glazed tiles and vermilion walls and columns signified high architectural hierarchy. In contrast, folk houses typically featured composite colors or exposed material tones, indicating a lower status. | ||

| 1-1-6 Paper: Used for lining interior walls and ceilings, as well as for partitioning interior spaces. | ||

| 1-2 Components & Decoration (8) | 1-2-1 Beam and Column 1. Framing system constructed with posts, beams, and purlins joined by mortise and tenon joints. 2. The post-and-lintel (tailiang) system stacks beams on columns and is common in palaces and temples. 3. The through-beam (chuandou) system links columns with tie beams and is typical in folk houses. | |

| 1-2-2 Dougong (Bracket Set) 1. Transfers roof load to beams and columns, reducing shear stress at joints. 2. Enhances visual complexity and indicates architectural hierarchy. | ||

| 1-2-3 Doors and Windows In southern China, doors and windows serve both lighting and ventilation functions. | ||

| 1-2-4 Ceilings 1. Exposed structure with painted or carved finish. 2. Flat or vaulted ceiling with grid or curved panels. 3. Caisson ceiling: multilayered and ornate, rich in symbolic and decorative meaning. | ||

| 1-2-5 Carving and Sculpture 1. Wood carving: applied to doors, windows, beams, screens, and furniture. 2. Stone carving: found on door bases, column pedestals, and steps. 3. Brick carving: mimics stone work and decorates walls, eaves, and doorframes. | ||

| 1-2-6 Decorative Painting and Murals 1. He-xi style: ornate and colorful, used in highest-ranking buildings. 2. Xuanzi style: typical of imperial complexes. 3. Qinglü style: plain tones with popular folk motifs. 4. Murals: commonly found in temples and tombs, depicting religion, rituals, and social life. | ||

| 1-2-7 Tablets and Couplets Couplets are written in parallel prose or regulated verse, calligraphed in distinctive styles and appreciated for their literary and aesthetic value. | ||

| 1-2-8 Paving Indoor surfaces are paved with neatly cut tiles or timber; outdoor paving uses bricks, stones, and rubble in irregular layouts. | ||

| 2. Syntax | 2-1 Roof (3) | 2-1-1 Roof Forms: Architectural hierarchy is reflected in roof types, ranked as follows (descending): double-eaved hip roof > double-eaved gable-and-hip roof > double-eaved pyramidal roof > single-eaved hip roof > single-eaved gable-and-hip roof > single-eaved pyramidal roof > overhanging gable roof > flush gable roof. 2-1-2 Roof Colors: Roof color also signifies hierarchy: yellow > green > dark gray. 2-1-3 Roof Ridges: Ornaments such as ridge beasts symbolize architectural function and rank. |

| 2-2 Main Structure (4) | 2-2 Main Structure: Walls, Doors, Windows, Colonnades 1. Most structures use timber framing, with walls as enclosures. 2. Large buildings feature peripheral colonnades and combine brick and wood. 3. Courtyard-facing or south-facing façades are typically all-wood construction. | |

| 2-3 Room (3) | 2-3 Interior Elements: Partitions, Furniture, Furnishings 1. Rooms are arranged linearly, often in odd numbers. 2. Supported by columns and divided by wooden partitions, allowing flexible interior layouts. | |

| 2-4 Platform (2) | 2-4 Platform Base: Steps and Railings Originally designed for rain protection, ventilation, and damp-proofing, platforms later evolved to express architectural status—transitioning from earthen bases to stone or brick terraces. | |

| 3. Grammar | 3-1 Rhetoric (5) | 3-1-1 Appropriation and Response: Terms include spontaneity, topographic adaptation, borrowed scenery, aesthetic integration, and temporal harmony. This approach seeks spatial harmony between architecture and its natural or built surroundings. |

| 3-1-2 Spatial Resonance: Involving transparency, layering, juxtaposition, shading, and emergence. It reflects the dynamic interplay between solid and void, matter and perception—embodying the cosmological notion of harmony between Heaven (nature) and humanity. | ||

| 3-1-3 Spatial Syntax: Elements include sequence, gradation, parallelism, symmetry, and interweaving. It structures space through repetitive or mirrored modules—analogous to paired or parallel lines in classical Chinese prose. | ||

| 3-1-4 Metaphoric Allusion: Involving metaphor, symbolism, evocation, and mimicry. Emotional or philosophical intent is projected onto physical forms, creating a poetic unity between mind and matter. | ||

| 3-1-5 Literary Annotation: Involving synesthesia, scenic titling, classical allusion, euphemism, and metonymy. Through tablets, couplets, and poems, architectural spaces are enriched with literary meanings, evoking emotional resonance and poetic imagination beyond the built environment. | ||

| 3-2 Structure (3) | 3-2-1 Axis The axis organizes the spatial alignment between architecture and its environmental elements. It defines three aspects of spatial order: balance, orientation, and positioning. | |

| 3-2-2 Fractal Structure Architectural complexes exhibit hierarchical patterns from whole to part, large to small, coarse to refined—each level reflecting consistent design logic and aesthetic principles. | ||

| 3-2-3 Temporality Chinese architecture and gardens convey impermanence through change, flow, and growth, and suggest cyclical continuity via repetition and recurrence. | ||

| 3-3 Geomancy (1) | 3-3-1 Geomancy (Fengshui) Emphasizes harmony between human life and the natural environment, balancing forces of mutual generation and constraint. | |

| 4. Discourse | 4-1 Facilities (10) | 4-1-1 Monuments and Structures: Mausoleums, pailou (memorial gateways), steles, pagodas, altars, grottoes, theaters, towers, bridges, and city walls are mostly built of brick and stone but imitate timber in texture and form—delicate in detail and rich in aesthetic appeal. |

| 4-2 Garden (3) | 4-2-1 Layout: Typically residential in origin, garden layouts embody miniature landscapes and personified reconstructions of nature. | |

| 4-2-2 Pavilions, Waterside Halls, Corridors, and Bridges: Garden structures for rest and viewing, noted for their flexible forms and refined aesthetics. | ||

| 4-2-3 Rockeries, Water Systems, and Plantings: Ornamental landscape elements that emulate natural forms and features. | ||

| 4-3 Courtyard (3) | 4-3-1 Single Courtyards: Northern types include spacious siheyuan and sanheyuan; southern types often feature compact patio-style courtyards (tianjing). 4-3-2 Composite Courtyards: Typically axial, comprising multiple units aligned along one or more axes, with symmetrical layouts and clear spatial hierarchy in volume, elevation, and function. 4-3-3 Spatial Openness: Outwardly enclosed but internally cohesive—spaces blend closely, fostering intimacy and integration. | |

| 4-4 Village (4) | 4-4-1 Clustered Forms: Grid patterns prevailed on plains, while strip-like formations dominated hilly and mountainous areas. 4-4-2 Communal Activities: Villages typically included open spaces and ritual structures for communal use. 4-4-3 Defense: Some villages were enclosed by moats or high walls for security purposes. 4-4-4 Lineage-Based Settlements: Villages were often inhabited by a single clan, with names derived from the family surname. | |

| 4-5 Town (4) | 4-5-1 Transportation Nodes: Market towns were located at intersections of land and water routes, serving as hubs for goods and labor. 4-5-2 Trade Functions: Efficient transport attracted active commodity exchange and distribution. 4-5-3 Spatial Planning: Well-equipped and stylistically coherent, towns were often laid out in fishbone patterns along main streets and usually lacked city walls. 4-5-4 Religion and Social Life: Seasonal religious gatherings drew large crowds, stimulating cultural events and market activities. | |

| 4-6 City (5) | 4-6-1 Cosmological Order: The concept of “round heaven and square earth” expressed harmony between humans and the universe. 4-6-2 Grid Layout: Urban sites on level terrain often adopted a grid-based spatial organization. 4-6-3 Hierarchical Regulations: City scale, wall height, and road width were regulated according to administrative rank. 4-6-4 Functional Zoning: Cities were divided into zones by social function and class—e.g., imperial precincts and commoner quarters—exemplified by the “lifang” system. 4-6-5 Defensive Design: Cities featured tall walls and protective moats for security. |

References

- National Cultural Heritage Administration. China’s World Cultural Heritage; National Cultural Heritage Administration: Beijing, China, 1985. Available online: http://www.ncha.gov.cn/col/col2790/index.html (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Su, R.; Bramwell, B.; Whalley, P.A. Cultural political economy and urban heritage tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 68, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilkaitė-Vaitonė, N. How do individual cultural orientations shape tourists’ perceptions of sustainable accommodation value? Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumer, H. Symbolic Interactionism: Perspective and Method; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- De Saussure, F. Course in General Linguistics; Harris, R., Translator; Duckworth: London, UK, 1983. (Original work published 1916). [Google Scholar]

- Peirce, C.S. The Logic of Relatives. In Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce; Hartshorne, C., Weiss, P., Eds.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1931–1958; Volume 3, pp. 643–645. [Google Scholar]

- Eco, U. A Theory of Semiotics; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 1976; pp. 9–13. ISBN 0-253-20170-5. [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport, A. The Meaning of the Built Environment: A Nonverbal Communication Approach; University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 1982; pp. 46–89. ISBN 0-8165-0907-9. [Google Scholar]

- Jencks, C. The Iconic Building: The Power of Enigma; Frances Lincoln: London, UK, 2005; p. 27. ISBN 1-85669-433-0. [Google Scholar]

- Metro-Roland, M. Interpreting meaning: An application of Peircean semiotics to tourism. Tour. Geogr. 2009, 11, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, R.C.; Vester, S.P. Towards a semiotics-based typology of authenticities in heritage tourism. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2016, 16, 254–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Y. The Historical Destiny of Beijing Siheyuan: Protection and Development from the Perspective of Architectural Typology. Zhuangshi 2008, 4, 87–89. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Li, X. Public space in traditional settlements from a ritual-scene perspective: A case study of the ancestral temple cluster in Zhixi, Western Fujian. New Archit. 2021, 1, 104–109. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, R.; Buchanan, J. Traditional visual language: A geographical semiotic analysis of indigenous linguistic landscape of ancient waterfront towns in China. SAGE Open 2022, 12, 21582440211068503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Hu, X. Semiotic analysis of Chinese folk architecture in modern planning. Prostor 2024, 32, 266–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisinger, Y.; Turner, L.W. Cross-Cultural Behaviour in Tourism: Concepts and Analysis; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2003; ISBN 0-7506-5585-6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Cho, T.; Wang, H.; Ge, Q. The influence of cross-cultural awareness and tourist experience on authenticity, tourist satisfaction and acculturation in world cultural heritage sites of Korea. Sustainability 2018, 10, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chronis, A. Between place and story: Gettysburg as tourism imaginary. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 1797–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Chu, J. Tourist experience at religious sites: A case study of the Chinese visiting the Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque. J. China Tour. Res. 2019, 16, 447–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petr, C. Tourist apprehension of heritage: A semiotic approach to behaviour patterns. Int. J. Arts Manag. 2002, 4, 25–28. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41064753 (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Hall, E.T. Beyond Culture; Anchor Books: New York, NY, USA, 1976; ISBN 978-0-385-12474-4. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001; ISBN 978-0-8039-7323-7. [Google Scholar]

- Colladon, A.F.; Guardabascio, B.; Innarella, R. Using social network and semantic analysis to analyze online travel forums and forecast tourism demand. Decis. Support Syst. 2019, 123, 113075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-1-5063-9566-8. [Google Scholar]

- QSR International. NVivo (Version 12); QSR International Pty Ltd.: Melbourne, Australia, 2020; Available online: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998; ISBN 978-0-8039-5939-2. [Google Scholar]

- Bazeley, P.; Jackson, K. Qualitative Data Analysis with NVivo, 2nd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-1-4462-0898-0. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Aldine: Chicago, IL, USA, 1967; ISBN 978-0-202-30260-7. [Google Scholar]

- Blei, D.M.; Ng, A.Y.; Jordan, M.I. Latent Dirichlet Allocation. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2003, 3, 993–1022. Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.5555/944919.944937#:~:text=Abstract,explicit%20representation%20of%20a%20document (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Manning, C.D.; Raghavan, P.; Schütze, H. Introduction to Information Retrieval; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008; ISBN 978-0-521-86571-5. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, J.L.; Knutson, B.; Fung, H.H. Cultural variation in affect valuation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 90, 288–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.A. A circumplex model of affect. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 39, 1161–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, J.L. Ideal affect: Cultural causes and behavioral consequences. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 2, 242–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D. History of Ancient Chinese Architecture; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 1984; pp. 101–135. ISBN 978-7-112-00166-6. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Fu, X.; Guo, D.; Pan, G.; Sun, D. History of Ancient Chinese Architecture; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2003; Volume 1–5, ISBN 978-7-112-04014-6. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q. Language of Classical Chinese Architecture; China Machine Press: Beijing, China, 2007; ISBN 7-111-20196-5. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lou, Q.X. Traditional Chinese Architectural Culture, 2nd ed.; China Travel & Tourism Press: Beijing, China, 2021; ISBN 978-7-503-25873-9. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D. Cultural symbols in Chinese architecture. Archit. Des. Rev. 2018, 1, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, B. A Study on the Spatial Rhetoric of Traditional Chinese Architecture. Ph.D. Thesis, Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology, Xi’an, China, 2008; pp. 35–101. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, X.; Cao, R. Chinese tourists’ perceptions and consumption of cultural heritage: A generational perspective. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 26, 719–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K. Cultural landscapes and Asia: Reconciling international and Southeast Asian regional values. Landsc. Res. 2009, 34, 7–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, E.W. Orientalism; 25th anniversary ed.; Vintage Books: New York, NY, USA, 1978; p. 94. ISBN 978-0-394-74067-5. [Google Scholar]

- Assmann, J. Collective memory and cultural identity. New Ger. Crit. 1995, 65, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.A.; Cohen, E. New directions in the sociology of tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 153–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Chen, M. Tracing the Evolution of Tourist Perception of Destination Image: A Multi-Method Analysis of a Cultural Heritage Tourist Site. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L. Uses of Heritage; Routledge: London, UK, 2006; ISBN 978-0-415-31253-3. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Xu, J.; Xiang, H.; Xie, M.; Tan, Y. Historical culture and tourist perception: A social network analysis of spatial structure and auspicious symbolism in Minnan village. npj Heritage Sci. 2025, 13, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Liu, L.; Xu, R. The effects of a virtual reality tourism experience on tourists’ cultural dissemination behavior. Tourism Hosp. 2022, 3, 314–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Rahman, I. Cultural tourism: An analysis of engagement, cultural contact, memorable tourism experience and destination loyalty. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 26, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowacki, M. Heritage Interpretation and Sustainable Development: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, G.; Zonah, S. Revolutionising Heritage Interpretation with Smart Technologies: A Blueprint for Sustainable Tourism. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nag, A.; Mishra, S. Exploring Dark Tourism in Mining Heritage: Competitiveness and Ethical Dilemmas. J. Mining Environ. 2024, 15, 863–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minucciani, V.; Benente, M.; Strada, F.; Bottino, A. Virtual Reality for Cultural Heritage: Emotional involvement and Design for all. Design for Inclusion 2024, 12, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champion, E. Critical Gaming: Interactive History and Virtual Heritage; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-138-93931-4. [Google Scholar]

- Steriopoulos, E.; Khoo, C.; Wong, H.Y.; Hall, J.; Steel, M. Heritage tourism brand experiences: The influence of emotions and emotional engagement. J. Vac. Mark. 2024, 30, 489–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, E.H.; Sun, Y. Power relationships and coalitions in urban renewal and heritage conservation: The Nga Tsin Wai Village in Hong Kong. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 104811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, R.V.; Stephenson, M.L. Deciphering tourism and citizenship in a globalized world. Tour. Manag. 2013, 39, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirillova, K.; Fu, X.; Lehto, X.; Cai, L. What makes a destination beautiful? Dimensions of tourist aesthetic judgment. Tour. Manag. 2014, 42, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poria, Y.; Reichel, A.; Biran, A. Heritage site management: Motivations and expectations. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 162–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, D.J.; Erdoğan, H.A.; Samuels, J. Archaeological heritage and tourism: The archaeotourism intersection. Conserv. Manag. Archaeol. Sites 2024, 26, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroughi, M.; de Andrade, B.; Roders, A.P.; Wang, T. Public participation and consensus-building in urban planning from the lens of heritage planning: A systematic literature review. Cities 2023, 135, 104235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hunter, C. Community involvement for sustainable heritage tourism: A conceptual model. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 5, 248–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbutt, M.; East, S.; Spehar, B.; Estrada-Gonzalez, V.; Carson-Ewart, B.; Touma, J. The embodied gaze: Exploring applications for mobile eye tracking in the art museum. Visitor Stud. 2020, 23, 82–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Rodríguez, M.R.; Díaz-Fernández, M.C.; Gómez, C.P. Facial-expression recognition: An emergent approach to the measurement of tourist satisfaction through emotions. Telemat. Inform. 2020, 51, 101404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Val-Calvo, M.; Álvarez-Sánchez, J.R.; Ferrández-Vicente, J.M.; Díaz-Morcillo, A.; Fernández-Jover, E. Real-time multi-modal estimation of dynamically evoked emotions using EEG, heart rate and galvanic skin response. Int. J. Neural Syst. 2020, 30, 2050013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tussyadiah, I.P.; Wang, D.; Jung, T.H.; Tom Dieck, M.C. Virtual reality, presence, and attitude change: Empirical evidence from tourism. Tour. Manag. 2018, 66, 140–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Architectural Heritage | Name and Code of Heritage Sites (11) |

|---|---|

| Ancient Cities and Historic Districts | (1) Xi’an Ancient City * |

| Historic Towns | (2) Wuzhen, Zhejiang |

| Official Architecture | (3) The Palace Museum, Beijing * (4) Temple of Confucius, Qufu |

| Religious Architecture | (5) Ancient Architectural Complex of Mount Wudang |

| Mausoleum Architecture | (6) Mausoleum of the First Qin Emperor and the Terracotta Army, Xi’an * |

| Traditional Villages and Vernacular Dwellings | (7) Ancient Villages in Southern Anhui (Hongcun and Tangyue), Anhui |

| Cultural and Military Structures | (8) The Great Wall, Beijing * (9) Temple of Heaven, Beijing * |

| Gardens | (10) The Summer Palace, Beijing * (11) The Humble Administrator’s Garden, Suzhou * |

| Primary Symbol (4) | Secondary Symbol (15) | Tertiary Symbol (65) |

|---|---|---|

| Lexicon | Materials | Wood, Earth, Brick/Stone, Tile, Paint, Paper |

| Components & Decoration | Beams & Columns, Dougong (Bracket Sets), Doors & Windows, Ceilings, Carvings/Sculptures, Decorative Paintings/Murals, Inscribed Plaques/Couplets, Paving | |

| Syntax | Roof | Form, Color, Ridges |

| Main Structure | Walls, Doors, Windows, Colonnades | |

| Room | Partitions, Furniture, Furnishings | |

| Platform | Steps, Railings | |

| Grammar | Rhetoric | Borrowing, Correspondence, Organization, Metaphor/Allusion, Annotation |

| Structure | Axis, Fractality, Temporality | |

| Geomancy | Geomancy (Fengshui) | |

| Discourse | Facilities | Mausoleum, Memorial Archway (Pailou), Steles, Pagoda, Altar, Grotto, Opera Stage, Storied Building, Bridge, City Wall |

| Garden | Layout, Pavilions/corridors/Bridges, Rockeries/Water Systems/Vegetation | |

| Courtyard | Single Courtyard, Compound Form, Spatial Openness | |

| Village | Clustered Layout, Public Activities, Defensive System, Clan-based Residence | |

| Town | Transportation, Trade, Planning, Religion & Social Interaction | |

| City | Round Heaven-square Earth Cosmology, Grid Pattern, Hierarchy, Zoning, Defense |

| Quadrant | Type | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HP | Awe | ● | ●●● | ● | ||||||||||||

| Pride | ● | ●● | ● | ● | ||||||||||||

| Surprise | ● | ●● | ||||||||||||||

| Curious | ● | ● | ● | ● | ●● | |||||||||||

| Pleasure | ● | ●● | ●● | ● | ||||||||||||

| Resonance | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||||||||

| LP | Belong | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||||||

| Identity | ● | ● | ●● | ● | ●● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||||

| Appreciate | ● | ●● | ●● | ● | ●● | ● | ● | ● | ||||||||

| Respect | ● | ●● | ●● | ●● | ● | ● | ||||||||||

| Nostalgia | ● | |||||||||||||||

| Familiarity | ●● | ● | ● | ● | ||||||||||||

| LN | Reflect | ●● | ● | |||||||||||||

| Detached | ● | |||||||||||||||

| Confused | ● | ● | ||||||||||||||

| ● C ● A ● UA | Material | Element | Roof | Elevation | Room | Platform | Rhetoric | Structure | Geomancy | Facility | Garden | Courtyard | Village | Town | City |

| Cultural Group | Symbol Discovery | Primary Perception | Meaning Interpretation | Interactive Feedback | Cultural Internalization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group C | Recognition of traditional architectural forms | Elicitation of culturally affiliative emotions | Ritual-based interpretation/Activation of historical memory | Static observation/Introspective expression | Formation of cultural identity and sense of belonging |

| Group A | Focus on familiar components | Comparative interpretation/Sensory resonance | Cultural analogy/identification of differences | Rational inquiry/Dialogic feedback | Cultural comparison/Memory construction |

| Group UA | Stimuli from visual novelty | Aesthetic novelty/Sensory impact, | Tag-based interpretation/Construction of exoticism | Selfie-sharing/Cross-cultural storytelling | Fragmented experience/Visually driven memory |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shao, G.; Zhang, J.; Bu, L.; Wang, J. Cross-Cultural Perceptual Differences in the Symbolic Meanings of Chinese Architectural Heritage. Buildings 2025, 15, 3506. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15193506

Shao G, Zhang J, Bu L, Wang J. Cross-Cultural Perceptual Differences in the Symbolic Meanings of Chinese Architectural Heritage. Buildings. 2025; 15(19):3506. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15193506

Chicago/Turabian StyleShao, Guoliang, Jinhe Zhang, Lingfeng Bu, and Jingwei Wang. 2025. "Cross-Cultural Perceptual Differences in the Symbolic Meanings of Chinese Architectural Heritage" Buildings 15, no. 19: 3506. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15193506

APA StyleShao, G., Zhang, J., Bu, L., & Wang, J. (2025). Cross-Cultural Perceptual Differences in the Symbolic Meanings of Chinese Architectural Heritage. Buildings, 15(19), 3506. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15193506