Environmental Design Innovation in Hospitality: A Sustainable Framework for Evaluating Biophilic Interiors in Rooftop Restaurants

Abstract

1. Introduction

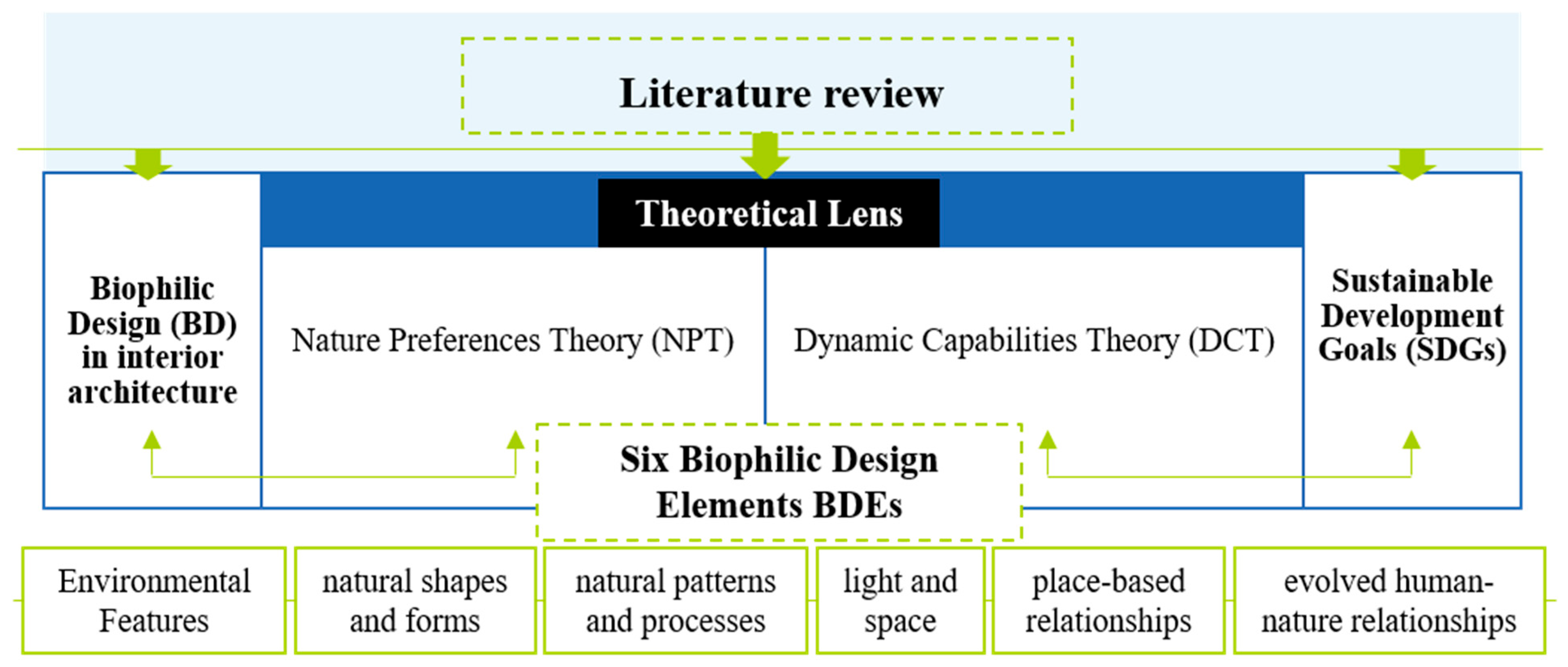

2. Literature Review

2.1. Biophilic Design (BD) in Interior Architecture

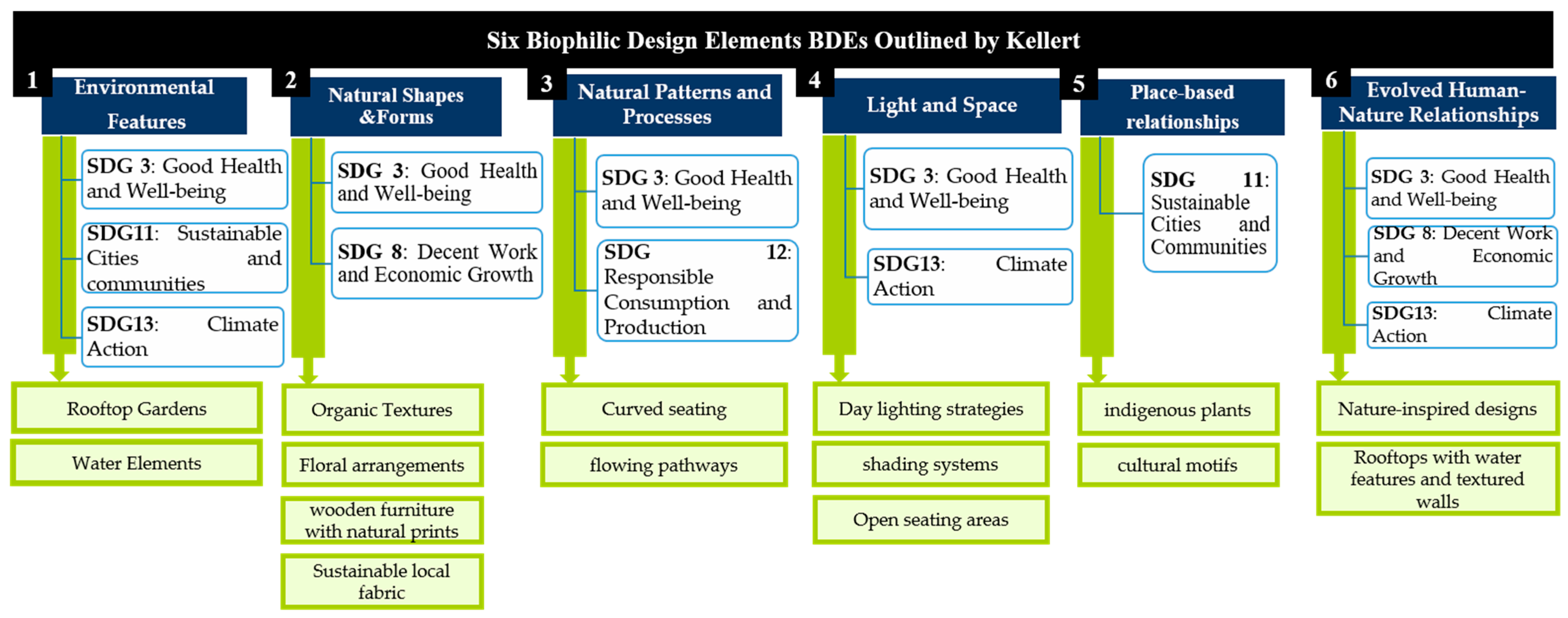

2.1.1. Biophilic Design Elements (BDEs)

2.1.2. Biophilic Design Framework by Kellert

2.1.3. Browning’s 14 Patterns of Biophilic Design

2.1.4. Geometrical Theory of Salingaros

2.2. Theoretical Lens

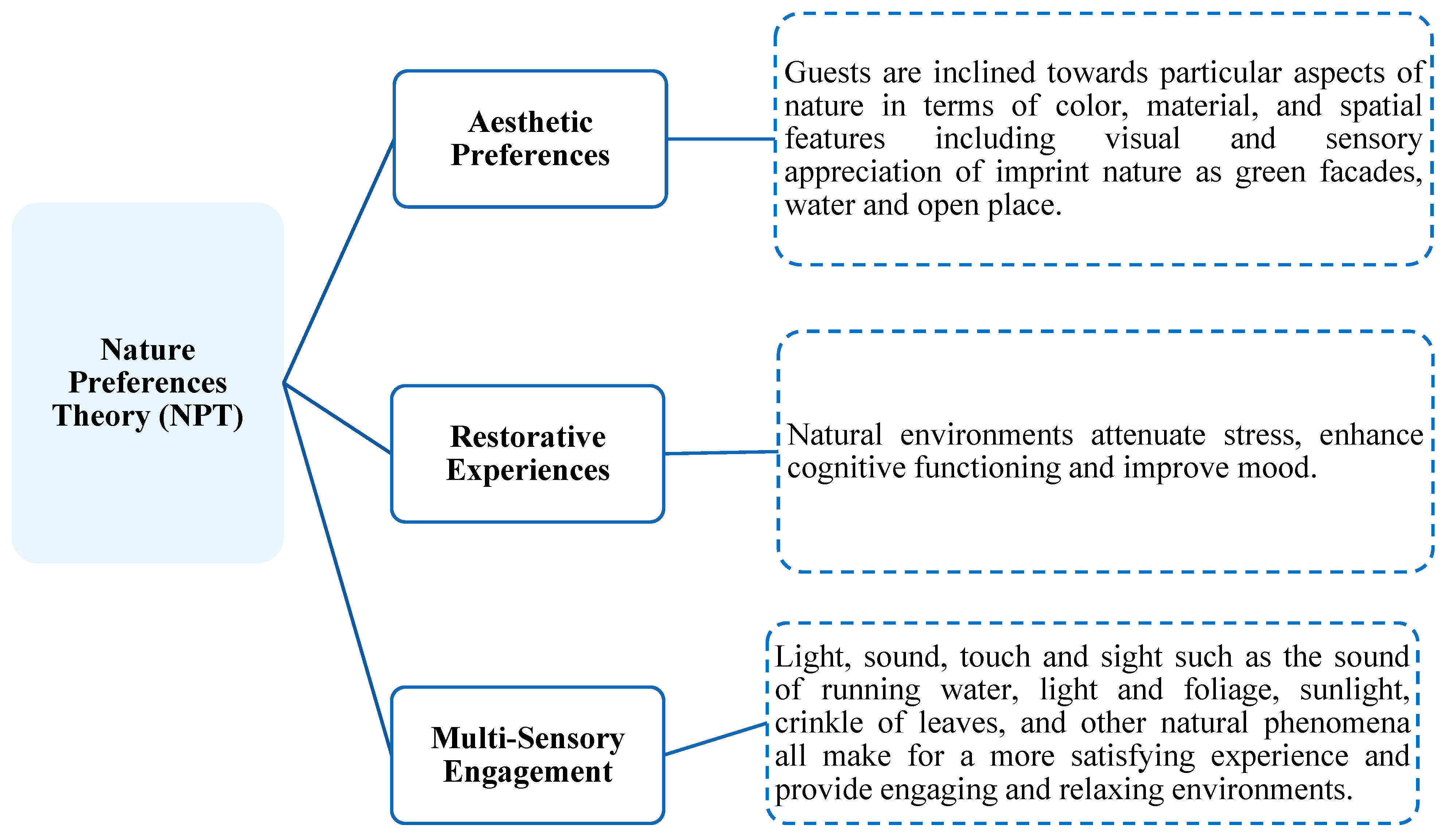

2.2.1. Nature Preferences Theory (NPT)

2.2.2. Dynamic Capabilities Theory (DCT)

2.3. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

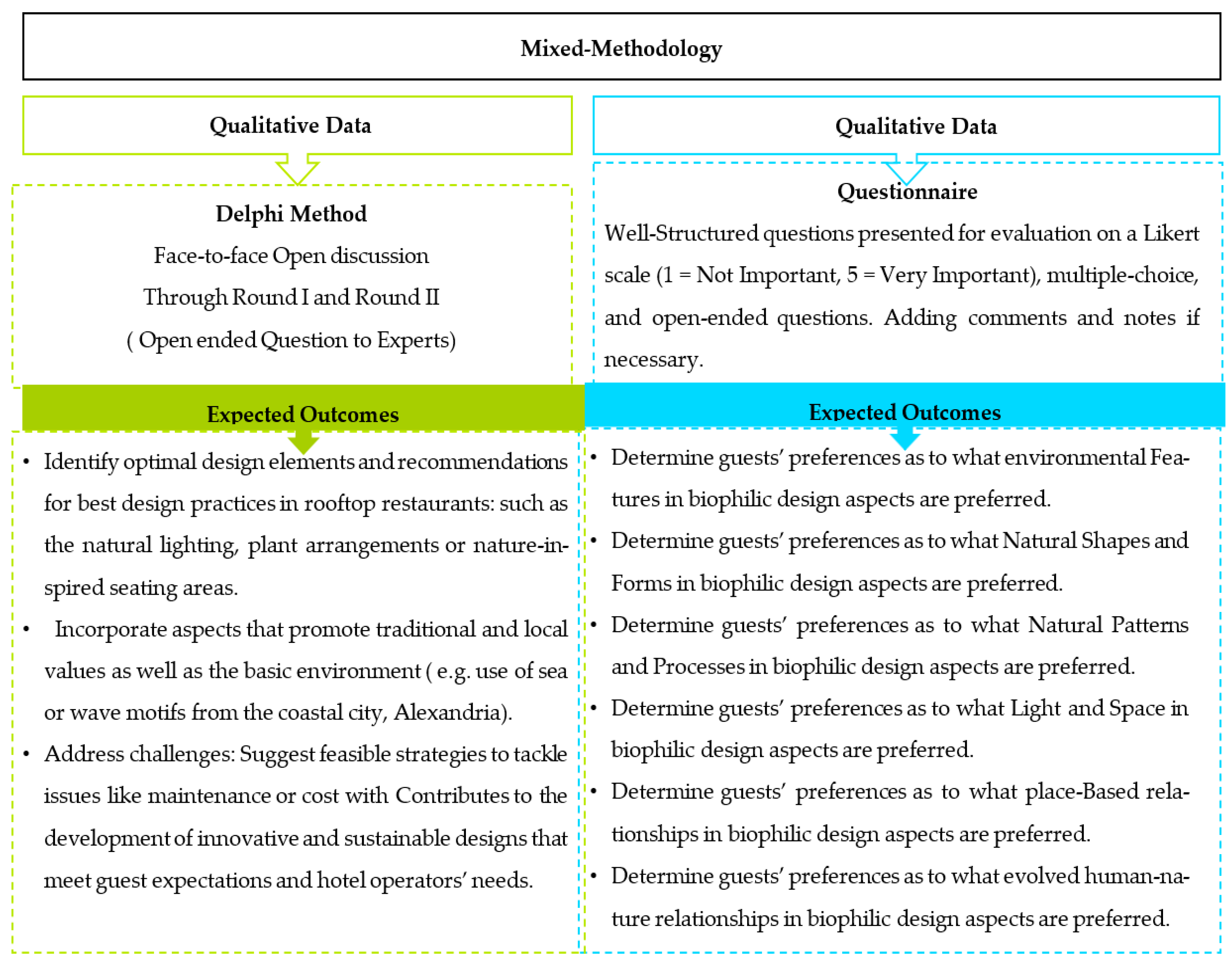

3. Methodology

3.1. Delphi Method

3.2. Guest Questionnaire

3.3. Summary of the Mixed Methodology

4. Practical Implication

4.1. Study Area

4.2. On-Site Observation

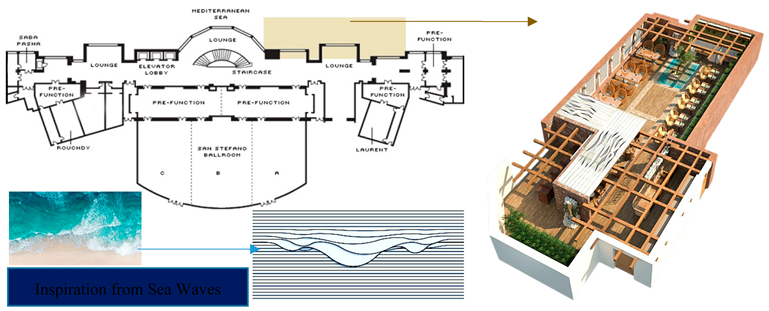

4.3. Experimental Design

5. Discussion and Conclusions

6. Limitations for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sharma, R. Hospitality Sustainable Practices, a Global Perspective. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2023, 15, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, S.; Feng, C.; Jiang, S.; Wei, J.; Xu, Y. Data-Driven Robust DEA Models for Measuring Operational Efficiency of Endowment Insurance System of Different Provinces in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanu, L.; Ali, F.; Berezina, K.; Cobanoglu, C. The Effect of Hotel Lobby Design on Booking Intentions: An Intergenerational Examination. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 89, 102530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I.A.; Azazz, A.M.S.; Kooli, C.; Alqasa, K.M.A.; Afaneh, J.; Fathy, E.A.; Fouad, A.M.; Fayyad, S. Resilience for Sustainability: The Synergistic Role of Green Human Resources Management, Circular Economy, and Green Organizational Culture in the Hotel Industry. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, H.; Adibhesami, M.A.; Bazazzadeh, H.; Movafagh, S. Green Buildings: Human-Centered and Energy Efficiency Optimization Strategies. Energies 2023, 16, 3681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I.A.; Alyahya, M.; Azazz, A.M.S.; Mansour, M.A.; Mohammad, A.A.A.; Fayyad, S. Understanding the Nexus between Social Commerce, Green Customer Citizenship, Eco-Friendly Behavior and Staying in Green Hotels. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S.R. Nature by Design: The Practice of Biophilic Design; Yale University Press: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 0300214537. [Google Scholar]

- Elshaer, I.A.; Azazz, A.M.S.; Fayyad, S.; Mohamed, S.A.; Fouad, A.M.; Fathy, E.A. From Data to Delight: Leveraging Social Customer Relationship Management to Elevate Customer Satisfaction and Market Effectiveness. Information 2024, 16, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, I.E.; Fathy, E.A.; Fouad, A.M.; Elbaz, A.M.; Abdien, M.K. Navigating Green Innovation via Absorptive Capacity and the Path to Sustainable Performance in Hotels. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2025, 8, 2140–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S.R.; Heerwagen, J.; Mador, M. Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; ISBN 1118174240. [Google Scholar]

- Bakr, A.A.M.; Ali, E.R.; Aljurayyad, S.S.; Fathy, E.A.; Fouad, A.M. From Authenticity to Sustainability: The Role of Authentic Cultural and Consumer Knowledge in Shaping Green Consumerism and Behavioral Intention to Gastronomy in Heritage Restaurants in Hail, Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. THE 17 GOALS. Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- Sonnentag, S.; Fritz, C. The Recovery Experience Questionnaire: Development and Validation of a Measure for Assessing Recuperation and Unwinding from Work. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2007, 12, 204–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilden, R.; Devinney, T.M.; Dowling, G.R. The Architecture of Dynamic Capability Research Identifying the Building Blocks of a Configurational Approach. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2016, 10, 997–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhou, R.; Yu, Q.; Zhao, L. Revealing the Contribution of Mountain Ecosystem Services Research to Sustainable Development Goals: A Systematic and Grounded Theory Driven Review. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, D.; Halbrook, R.; Meder, D.; Stuchlik, M.; Thorpe, S. Employee and Customer Attachment: Synergies for Competitive. People Strategy 1991, 14, 89. [Google Scholar]

- Kellert, S.R. Dimensions, Elements, and Attributes of Biophilic Design. Biophilic Des. Theory Sci. Pract. Bringing Build. Life 2008, 2008, 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kellert, S.R. Building for Life: Designing and Understanding the Human-Nature Connection; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; ISBN 1597265918. [Google Scholar]

- Buhalis, D.; Leung, X.Y.; Fan, D.; Darcy, S.; Chen, G.; Xu, F.; Wei-Han Tan, G.; Nunkoo, R.; Farmaki, A. Editorial: Tourism 2030 and the Contribution to the Sustainable Development Goals: The Tourism Review Viewpoint. Tour. Rev. 2023, 78, 293–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziervogel, G.; Ericksen, P.J. Adapting to Climate Change to Sustain Food Security. WIREs Clim. Change 2010, 1, 525–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legrand, W.; Chen, J.S.; Laeis, G.C.M. Sustainability in the Hospitality Industry: Principles of Sustainable Operations; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2022; ISBN 1003081126. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, D.; Merrilees, B.; Coghlan, A. Sustainable Urban Tourism: Understanding and Developing Visitor pro-Environmental Behaviours. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelbman, A. Tourist Experience and Innovative Hospitality Management in Different Cities. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, L.C.; Leonidou, C.N.; Fotiadis, T.A.; Aykol, B. Dynamic Capabilities Driving an Eco-Based Advantage and Performance in Global Hotel Chains: The Moderating Effect of International Strategy. Tour. Manag. 2015, 50, 268–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demydyuk, G.V.; Carlbäck, M. Balancing Short-Term Gains and Long-Term Success in Lodging: The Role of Customer Satisfaction and Price in Hotel Profitability Model. Tour. Econ. 2024, 30, 844–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I.A.; Azazz, A.M.S.; Fayyad, S. Residents’ Environmentally Responsible Behavior and Tourists’ Sustainable Use of Cultural Heritage: Mediation of Destination Identification and Self-Congruity as a Moderator. Heritage 2024, 7, 1174–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S.; Calabrese, E. The Practice of Biophilic Design. Lond. Terrapin Bright LLC 2015, 3, 2021–2029. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, C.O.; Browning, W.D.; Clancy, J.O.; Andrews, S.L.; Kallianpurkar, N.B. Biophilic Design Patterns: Emerging Nature-Based Parameters for Health and Well-Being in the Built Environment. ArchNet-IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 2014, 8, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratman, G.N.; Hamilton, J.P.; Daily, G.C. The Impacts of Nature Experience on Human Cognitive Function and Mental Health. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2012, 1249, 118–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, E.N.; Kline, S. From Satisfaction to Delight: A Model for the Hotel Industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2006, 18, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tifferet, S.; Vilnai-Yavetz, I. Phytophilia and Service Atmospherics: The Effect of Indoor Plants on Consumers. Environ. Behav. 2017, 49, 814–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H. Effects of Biophilic Design on Consumer Responses in the Lodging Industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 83, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratman, G.N.; Anderson, C.B.; Berman, M.G.; Cochran, B.; de Vries, S.; Flanders, J.; Folke, C.; Frumkin, H.; Gross, J.J.; Hartig, T.; et al. Nature and Mental Health: An Ecosystem Service Perspective. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaax0903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fainshmidt, S.; Wenger, L.; Pezeshkan, A.; Mallon, M.R. When Do Dynamic Capabilities Lead to Competitive Advantage? The Importance of Strategic Fit. J. Manag. Stud. 2019, 56, 758–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijesooriya, N.; Brambilla, A.; Markauskaite, L. Biophilic Design Frameworks: A Review of Structure, Development Techniques and Their Compatibility with LEED Sustainable Design Criteria. Clean. Prod. Lett. 2023, 4, 100033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S.R. Kinship to Mastery; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; ISBN 1597268909. [Google Scholar]

- Salingaros, N.A. Biophilia & Healing Environments: Healthy Principles for Designing the Built World; Terrapin Bright Green: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zare, G.; Faizi, M.; Baharvand, M.; Masnavi, M. A Review of Biophilic Design Conception Implementation in Architecture. J. Des. Built Environ. 2021, 21, 16–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joye, Y.; De Block, A. ‘Nature and I Are Two’: A Critical Examination of the Biophilia Hypothesis. Environ. Values 2011, 20, 189–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitburn, J.; Linklater, W.; Abrahamse, W. Meta-analysis of Human Connection to Nature and Proenvironmental Behavior. Conserv. Biol. 2020, 34, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I.A.; Azazz, A.M.S.; Fayyad, S.; Kooli, C.; Fouad, A.M.; Hamdy, A.; Fathy, E.A. Consumer Boycotts and Fast-Food Chains: Economic Consequences and Reputational Damage. Societies 2025, 15, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I.A.; Azazz, A.M.S.; Aljoghaiman, A.; Fayyad, S.; Abdulaziz, T.A.; Emam, A. The Lighter Side of Leadership: Exploring the Role of Humor in Balancing Work and Family Demands in Tourism and Hospitality. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbiero, G.; Berto, R. Biophilia as Evolutionary Adaptation: An Onto- and Phylogenetic Framework for Biophilic Design. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 700709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macpherson, F. Taxonomising the Senses. Philos. Stud. 2011, 153, 123–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, C.; Zhang, X.N. Tourist Experiences: Insights from Psychology; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2024; Volume 98, ISBN 184541926X. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, W.; Schroeder, T.; Bekkering, J. Designing with Nature: Advancing Three-Dimensional Green Spaces in Architecture through Frameworks for Biophilic Design and Sustainability. Front. Archit. Res. 2023, 12, 732–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouad, A.M.; Abdullah Khreis, S.H.; Fayyad, S.; Fathy, E.A. The Dynamics of Coworker Envy in the Green Innovation Landscape: Mediating and Moderating Effects on Employee Environmental Commitment and Non-Green Behavior in the Hospitality Industry. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, M.; Sabernejad, J. Investigation of Biophilic Architecture Patterns and Prioritizing Them in Design Performance in Order to Realize Sustainable Development Goals. Eur. Online J. Nat. Soc. Sci. Proc. 2016, 5, 325–337. [Google Scholar]

- Suess, C.; Legendre, T.S.; Hanks, L. Biophilic Urban Hotel Design and Restorative Experiencescapes. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2024, 48, 1572–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalkey, N.; Helmer, O. An Experimental Application of the DELPHI Method to the Use of Experts. Manag. Sci. 1963, 9, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillis, K.; Gatersleben, B. A Review of Psychological Literature on the Health and Wellbeing Benefits of Biophilic Design. Buildings 2015, 5, 948–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabassum, R.R.; Park, J. Development of a Building Evaluation Framework for Biophilic Design in Architecture. Buildings 2024, 14, 3254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, T.; Grønhaug, K. Can Design Improve the Performance of Marketing Management? J. Mark. Manag. 2007, 23, 815–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijesooriya, N.; Brambilla, A. Bridging Biophilic Design and Environmentally Sustainable Design: A Critical Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 283, 124591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M.; Kumar, S.; Donthu, N.; Sureka, R.; Joshi, Y. A Bibliometric Overview of the Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management: Research Contributions and Influence. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 47, 273–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Ryu, K. The Roles of the Physical Environment, Price Perception, and Customer Satisfaction in Determining Customer Loyalty in the Restaurant Industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2009, 33, 487–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios, M.; Guilera, G.; Nuño, L.; Gómez-Benito, J. Consensus in the Delphi Method: What Makes a Decision Change? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 163, 120484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I.A.; Azazz, A.M.S.; Fayyad, S.; Aljoghaiman, A.; Fathy, E.A.; Fouad, A.M. From Asymmetry to Satisfaction: The Dynamic Role of Perceived Value and Trust to Boost Customer Satisfaction in the Tourism Industry. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.; Schröder, T.; Bekkering, J. Implementing Biophilic Design in Architecture through Three-Dimensional Green Spaces: Guidelines for Building Technologies, Plant Selection, and Maintenance. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 92, 109648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doorley, S.; Witthoft, S. Make Space: How to Set the Stage for Creative Collaboration; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; ISBN 1118143728. [Google Scholar]

- Fiscus, D.A.; Fath, B.D. Foundations for Sustainability: A Coherent Framework of Life–Environment Relations; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; ISBN 0128116447. [Google Scholar]

- Nanu, L.; Rahman, I. The Biophilic Hotel Lobby: Consumer Emotions, Peace of Mind, Willingness to Pay, and Health-Consciousness. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 113, 103520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, L.M.; Shiu, E.; Parry, S. Addressing the Cross-country Applicability of the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB): A Structured Review of Multi-country TPB Studies. J. Consum. Behav. 2016, 15, 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouad, A.M.; Salem, I.E.; Fathy, E.A. Generative AI Insights in Tourism and Hospitality: A Comprehensive Review and Strategic Research Roadmap. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, B.; Park, N.; Portillo, M.; Bosch, S.; Swisher, M. Diy Biophilia: Development of the Biophilic Interior Design Matrix as a Design Tool. J. Inter. Des. 2019, 44, 201–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| BDEs (Outlined by Kellert) | DCT Perspective | Design Application in Rooftop Restaurant |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental Features | Hotels can sense guest demand for sustainable, nature-integrated designs and respond by implementing greenery and water features. Seizing opportunities: Green rooftop environments differentiate hotels, attracting eco-conscious and wellness-seeking guests. | Rooftop gardens and water features offer dual benefits of aesthetic appeal and psychological restoration, aligning with sustainable tourism trends. |

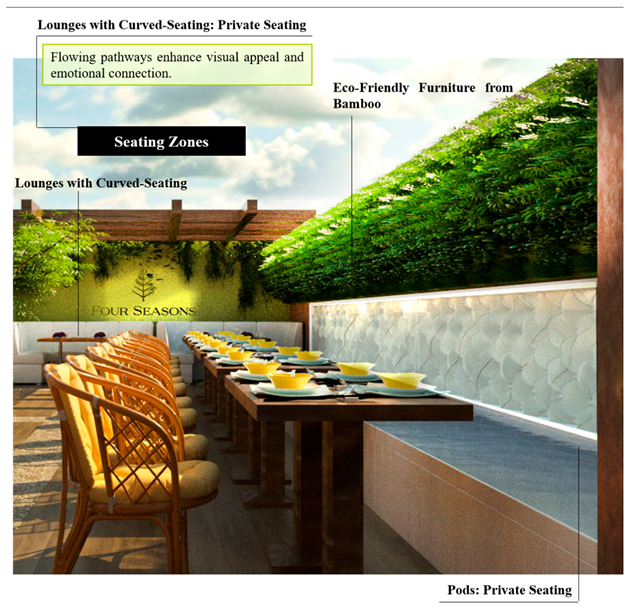

| Natural Shapes and Forms | Reconfiguring interiors to include organic forms demonstrates a hotel’s ability to adapt to modern design trends, enhance guest experiences, and contribute to a unique brand identity. | Curved furniture and flowing pathways enhance visual appeal and emotional connection. Dining furniture with decorative features resembling leaves or waves can foster a subconscious connection to nature. Incorporating curved seating tree-like structures not only enhances visual appeal but also improves guests’ emotional connections to the space. |

| Natural Patterns and Processes | Hotels sense and seize opportunities by integrating dynamic elements to create visually dynamic and engaging spaces. Reconfiguring design processes to accommodate changing patterns ensures that guest experiences remain fresh and relevant. | Incorporating natural textures and seasonal decorations creates a dynamic environment. Incorporating natural stone textures and seasonal floral arrangements provides an aesthetically rich and engaging dining experience. Reflective surfaces align with guest preferences and reinforce brand identity. |

| Light and Space | Hotels that reconfigure spaces to maximise natural light and openness respond to sensed trends for environmentally friendly and wellness-oriented design. These elements reduce operational costs and create memorable guest experiences. | A rooftop with large windows overlooking a city skyline or the sea, coupled with shaded areas for comfort, strikes a balance between openness and protection. Rooftops with open seating provide both functional and emotional benefits, enhancing guest satisfaction. |

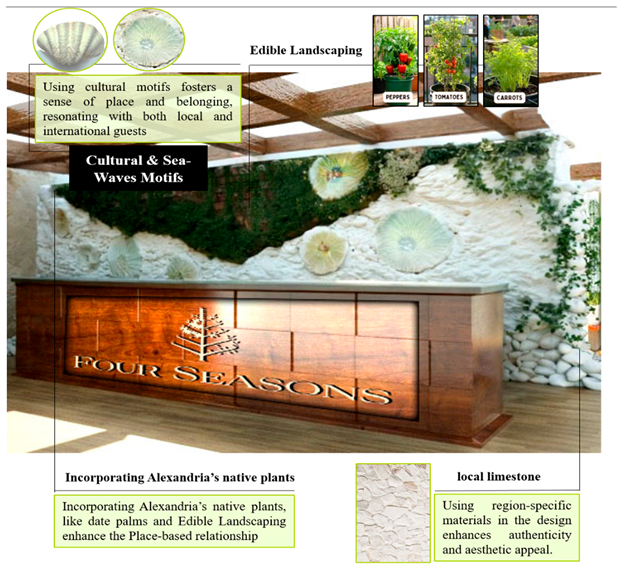

| Place-Based Relationships | This approach strengthens the hotel’s competitive position by appealing to travellers seeking authentic experiences through the integration of local culture and materials. | Incorporating Alexandria’s native plants, such as date palms, and utilising local limestone in the design enhance authenticity and aesthetic appeal. Using cultural motifs and region-specific materials fosters a sense of place and belonging, resonating with both local and international guests. |

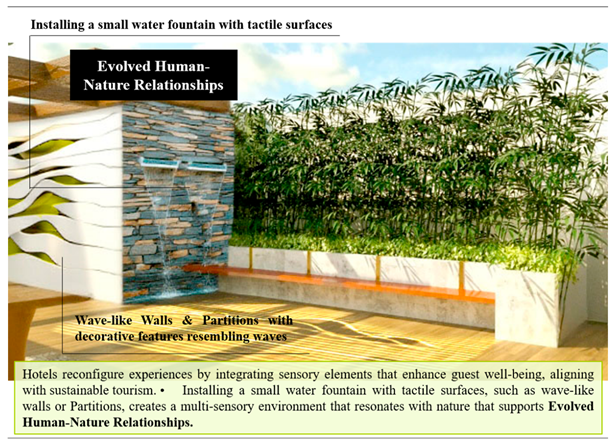

| Evolved Human–Nature Relationships | Hotels reconfigure experiences by integrating sensory elements that enhance guest well-being, aligning with the principles of sustainable tourism. | Installing a small water fountain and tactile surfaces, such as stone walls or wooden furniture, creates a multi-sensory environment that resonates with nature. |

| Dynamic Capabilities Theory (DCT) | Nature Preferences Theory (NPT) | |

|---|---|---|

| Feature | Tends to highlight the internal opportunities for BD and the need to evolve, adapting to changing market trends and use nature to gain competitive advantage. | Highlighting guest experience, discussing how BD meets essential human needs for exposure to nature. |

| Focus | Assessing and sustaining competition. Recognising and utilising assets in order to sustain a competitive edge in the hotel. | Individual decision and psycho-acceptance in environments incorporating natural elements. |

| Primary Outcome | Better operational activities in response to customer trends, higher organisational efficiency, and a competitive advantage. | Higher occupancy rates, less levels of stress, and a sense of feeling connected to the location. |

| Application In Interior Architectural Design Of Rooftop Restaurants | Adaptive designs and flexible layouts can be introduced in harmony with sustainable concepts to create a unique experience for guests. | Organic interiors and natural designs that accommodate guests’ urge to be surrounded by nature. |

| Expert’s Information | Classification | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 8.0 | 53.30 |

| Female | 7.0 | 46.70 | |

| Education | College/University | 3.0 | 20.0 |

| Master | 10.0 | 66.70 | |

| PhD | 2.0 | 13.30 | |

| position | Director/Dean/ | 7.0 | 46.70 |

| Managerial | 8.0 | 53.30 | |

| Working experience | 11–15 years | 2.0 | 13.30 |

| 16–20 years old | 6.0 | 40.0 | |

| 21–25 years old | 7.0 | 46.70 | |

| Total | 15.0 | 100.00 | |

| Open Discussion Questions for Expert Panel (Round 2) | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| Open Discussion Questions for Expert Panel (Round 2) | |

|---|---|

| Overall Knowledge and Existing Trends |

|

| (1) Environmental Features |

|

| (2) Natural Shapes and Forms |

|

| (3) Light and Space |

|

| (4) Natural Patterns and Processes |

|

| (5) Place-Based Relationships |

|

| (6) Evolved Human–Nature Relationships |

|

| |

| Gender | Men | 44 (62.9%) | Women | 26 (37.1%) |

| 1. What is your age group? | 21–30 | 31–40 | 41–50 | 51–59 |

| 30 (42.9%) | 19 (27.1%) | 21 (30.0%) | - | |

| Rarely | Occasionally | Frequently | |

| 1 (1.4%) | 19 (27.1%) | 50 (71.4%) | ||

| The questions | Mean | S.D. | ||

| Element1: Overall Knowledge and Existing Trends | ||||

| 1. How important is the dining environment in your decision to visit a rooftop restaurant? | 4.543 | 0.557 | ||

| Element2: Environmental Features | ||||

| ||||

| 4.543 | 0.582 | ||

| 4.500 | 0.608 | ||

| 4.514 | 0.531 | ||

| 4.571 | 0.554 | ||

| Element3: Natural Shapes and Forms | ||||

| 4.586 | 0.525 | ||

| 4.571 | 0.527 | ||

| Element4: Natural Patterns and Processes | ||||

| 4.471 | 0.583 | ||

| 4.386 | 0.666 | ||

| Element5: Light and Space | ||||

| 4.586 | 0.551 | ||

| 4.614 | 0.519 | ||

| Element6: Place-Based Relationships | ||||

| 4.629 | 0.516 | ||

| 4.614 | 0.519 | ||

| Element7: Evolved Human-Nature Relationships | ||||

| 4.443 | 0.629 | ||

| 4.586 | 0.525 | ||

| Site | Case Study Photo | Rooftop Spatial Features |

|---|---|---|

| Four Seasons Hotel (5-Stars Hotel) |  |  |

| Spatial Features | BDEs | BD Features | |

|---|---|---|---|

Kala Restaurant | Situated on the third floor, Kala Restaurant provides diners with views of the Mediterranean Sea, allowing natural light to enhance the dining ambiance. | Environmental Features | The restaurant achieves its coastal theme through blue accents and palm plants which provide a relaxing environment. |

| Light and Space | Extensive views of the sea establish the main linkage to nature which brings natural lighting into dining spaces to improve the dining experience. The biophilic principle of bringing nature into architecture finds expression in the building design through Mediterranean Sea view windows. | ||

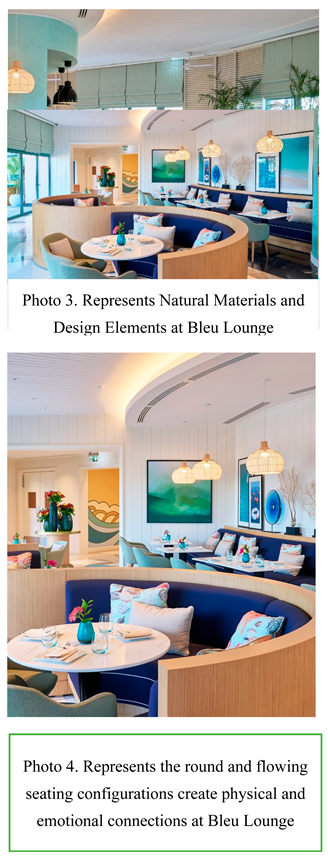

| Bleu Lounge has an outdoor space “terrace” where guests can enjoy views of the coastal nature. Bleu Lounge strategically integrates biophilic design elements (BDEs) to deliver an authentic Alexandria beachfront experience for its guests. | Environmental Features | The built-in contact with natural elements creates stronger sensory reactions which accede to the principles of biophilic design. |

| Light and Space | An open interior architectural design at the lounge provides maximum access to natural light, where sunlight streams easily into the space. Its open-air venue delivers functional lighting conditions that strengthen guests’ connection to outside elements and enhance the feeling of the sea breeze and hearing Mediterranean sounds beneath the natural daylight. | ||

| Natural Shapes and Forms | Bleu Lounge stands out through its naturally inspired, curved seating arrangements, which harmonise with the organic elements of nature. The round and flowing seating configurations create physical and emotional connections which enhance both quality and social interactions. | ||

| Place-Based Relationships | The interior design concept at Bleu Lounge draws from city flair natural materials and design elements. |

| The Conceptual Design Phase | |

|---|---|

| |

| BDEs | The Experimental Design Proposal |

|---|---|

| Environmental Features |  |

| Natural Shapes and Forms |  |

| Natural Patterns and Processes |  . . |

| Light and Space |  |

| Place-Based Relationships |  |

| Evolved Human–Nature Relationships |  |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elshaer, I.A.; Azazz, A.M.S.; Zayed, M.A.; Ameen, F.A.; Fayyad, S.; Fouad, A.M.; Fathy, E.A.; Hamdy, A. Environmental Design Innovation in Hospitality: A Sustainable Framework for Evaluating Biophilic Interiors in Rooftop Restaurants. Buildings 2025, 15, 3474. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15193474

Elshaer IA, Azazz AMS, Zayed MA, Ameen FA, Fayyad S, Fouad AM, Fathy EA, Hamdy A. Environmental Design Innovation in Hospitality: A Sustainable Framework for Evaluating Biophilic Interiors in Rooftop Restaurants. Buildings. 2025; 15(19):3474. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15193474

Chicago/Turabian StyleElshaer, Ibrahim A., Alaa M. S. Azazz, Mohamed A. Zayed, Faleh A. Ameen, Sameh Fayyad, Amr Mohamed Fouad, Eslam Ahmed Fathy, and Amira Hamdy. 2025. "Environmental Design Innovation in Hospitality: A Sustainable Framework for Evaluating Biophilic Interiors in Rooftop Restaurants" Buildings 15, no. 19: 3474. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15193474

APA StyleElshaer, I. A., Azazz, A. M. S., Zayed, M. A., Ameen, F. A., Fayyad, S., Fouad, A. M., Fathy, E. A., & Hamdy, A. (2025). Environmental Design Innovation in Hospitality: A Sustainable Framework for Evaluating Biophilic Interiors in Rooftop Restaurants. Buildings, 15(19), 3474. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15193474