1. Introduction

Historical records and built heritage are crucial resources for understanding the inner workings of past societies [

1]. As an integral component of human civilization, built heritage not only preserves spatial configuration and construction techniques in material form, but also embodies the institutional and cultural logics documented in texts [

2]. Historical records provide cultural contexts and social meanings, while architectural remains serve as tangible evidence of these institutions and practices [

3]. The integration of the two allows us to reconstruct historical patterns of dwelling and social organization, and more importantly, to uncover the cultural logic embedded in the interaction between institutions and space [

4]. In this sense, built heritage is not merely a physical remnant, but a “solidified social formation” that functions as a critical lens for examining the operational logic of historical societies [

5].

In fact, historical records and built heritage should not be regarded as two separate systems; rather, they are complementary forms of evidence. The entries, descriptions, and allocation rules in historical records often require validation through spatial configuration, while the interpretation of architectural remains can only reveal their deeper social significance when contextualized by textual evidence [

6]. However, systematic integration of the two remains limited in existing scholarship, leaving the sociological significance of built heritage insufficiently explored. In other words, while prior research has provided substantial insights into the morphological characteristics and cultural values of traditional architecture, there remains a distinct gap in addressing how these physical forms embodied and reproduced underlying social logics.

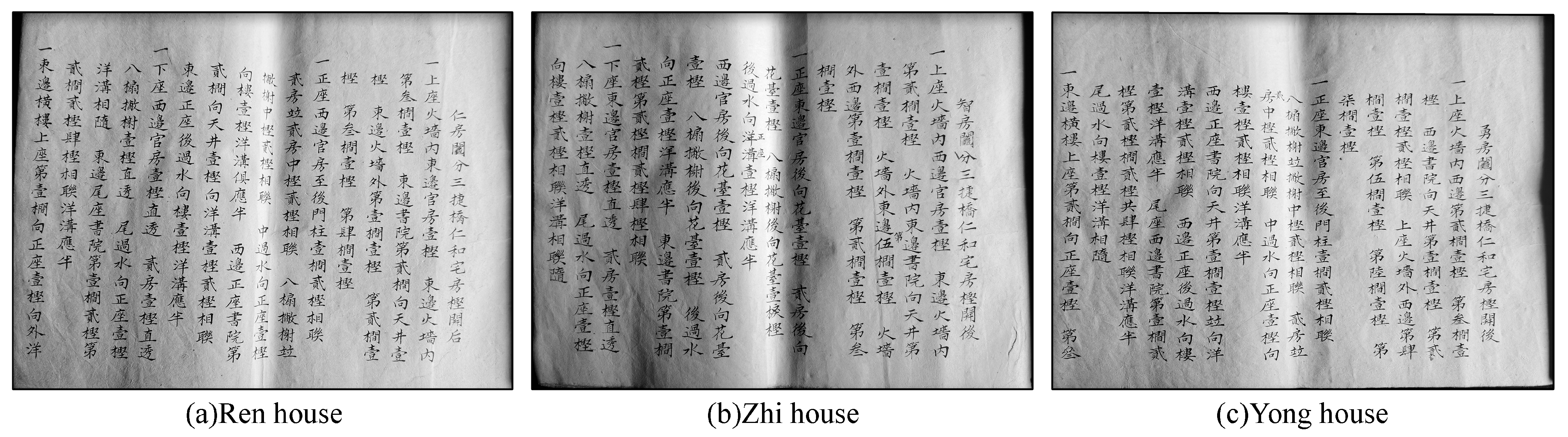

Against this background, this paper takes Renhezhuang, a lineage fortress located in Yongtai, Fujian Province, as a case study to explore an analytical framework that integrates “historical records–heritage.” Constructed during the mid-to-late Qing dynasty, Renhezhuang is one of the best-preserved fortified residences in the region. Its value lies not only in the preservation of detailed partition documents that record the distribution of property, but also in its relatively intact spatial configuration. This dual completeness makes Renhezhuang an ideal case for examining the interplay between historical records and architectural remains. By analyzing Renhezhuang through this combined lens, the study seeks to reveal the sociological significance encoded in its built form, highlighting the deeper value of built heritage as a “social text.”

The significance of this research is threefold. First, through the case of Renhezhuang, it demonstrates how the integration of historical records and heritage can transcend the limitations of single-dimensional approaches and reveal the interaction between spatial allocation and lineage order. Second, it contributes to the sociology of built heritage by proposing a methodological pathway that is adaptable to other cases.

2. Literature Review

Existing scholarship on built heritage generally falls into two contrasting approaches. The first tends toward cultural interpretation while downplaying material aspects. In such studies, built heritage is often regarded as a stage for social relations and cultural practices, with emphasis placed on symbolic and ritual meanings rather than spatial analysis [

7]. For instance, some researchers have examined the representational aspects of architectural drawings and diagrams [

8]. Other scholars have explored the profound meaning of symbols in architecture and their connection to human existence, emphasizing the importance of symbolism in architectural heritage [

9]. While these works enrich our understanding of cultural meaning, they often lack sufficient engagement with the materiality of architecture itself.

The second approach takes the opposite direction, privileging material dimensions while neglecting cultural interpretation. In this line of research, the value of built heritage is often reduced to style, form, chronology, or technical attributes. Methodologically, these works rely heavily on precision surveying, structural analysis, material testing, and archival dating [

10]. For example, some scholars have employed high-resolution scanning to document each architectural component in great detail, producing comprehensive sets of geometric data [

11]. Yet such records do not explain why the architecture assumed a particular spatial configuration, nor do they uncover the underlying social or cultural logic. These contributions are valuable in terms of documentation and preservation [

12], but their limitation lies in treating architecture as static objects, overlooking their embeddedness in social life.

In more recent work, scholars have attempted to bridge these two approaches by aligning historical records with spatial analysis, thereby illuminating the interaction between institutions and space. For instance, one study employed space syntax and visibility graph analysis to demonstrate how the design of Jin ancestral temples—through strategies of separation and connection—reflected a historical transition from single-function ritual sites to complex architectural compounds [

13]. Other scholars have explored the intangible cultural heritage elements embedded in architectural cultural heritage, identifying challenges and proposing solutions for their preservation in the process of safeguarding intangible cultural heritage [

14]. Such attempts point toward promising interdisciplinary directions, proving the feasibility and interpretive potential of the “historical records–heritage” approach. Nonetheless, these studies remain limited, as most still lack systematic frameworks or transferable methodologies.

In sum, existing research is divided between two dominant pathways: one relies on historical records with a textual emphasis, while the other relies on architectural remains with a focus on form. Both contribute valuable insights but seldom integrate with one another. As a result, the sociological significance of built heritage remains underexplored. This study therefore takes Renhezhuang as a representative case to propose a technology-supported approach that combines historical records and heritage. By juxtaposing the institutional logic embedded in partition documents with the spatial configuration of the fortified residence, and supplementing this with simulations of daylighting, ventilation, and space syntax, the study aims to reveal the deeper social logic of built heritage and to propose a methodological framework with potential applicability to broader contexts.

4. Results of Indicator Analysis

The analysis indicates that the spatial allocation of Renhezhuang was not solely reflected in the difference in the number of rooms but, more importantly, in how the lineage manifested its power hierarchy and practical wisdom through both physical and cultural dimensions. Whether in terms of number of rooms, daylighting, and ventilation, or in terms of privacy, centrality, and accessibility, the different family branches demonstrated a complementary distribution.

At the most basic spatial unit—the room—the study quantified daylighting and ventilation conditions, using the overall mean value as the benchmark to assess the relative advantages of each branch. This approach aligns with the construction logic of traditional fortified residences and avoids the limitation of applying modern residential standards directly to Qing-period architecture.

For daylighting, Renhezhuang relied primarily on patios to introduce natural light. Due to high surrounding walls, small or absent exterior windows, the overall interior was relatively dim. Calculations showed that the average daylight factor was 0.145, far below modern housing standards, but still constituting a reasonable reference framework within the fortress. Rooms with values above the mean were defined as having favorable daylighting. Statistical results showed that the Ren rooms possessed the largest number of well-lit rooms, followed by the Zhi rooms and the Yong rooms, while the public rooms had only a minimal number. This advantage is associated with the Ren rooms being located closer to the patios and central zones of the residence.

For ventilation, seasonal average wind speed was used to model comfort under different climatic conditions. In summer, rooms with wind speeds above a set threshold were deemed comfortable; in spring and autumn, comfort was defined by values within a specified range; in winter, lower wind speeds were considered favorable to ensure warmth. The overall results demonstrated that the Yong rooms had the best performance in ventilation, with the highest number of comfortable rooms, followed by the Zhi rooms and the Ren rooms, while the public rooms ranked lowest. The advantage of the Yong rooms derives from some of its rooms being located near the outer edges of the fortress, where air circulation was stronger.

In summary, the Zhi rooms held an advantage in number of rooms, the Ren rooms excelled in daylighting, and the Yong rooms performed best in ventilation (

Table 1).

Beyond the physical dimension, the humanistic indicators also revealed significant differences. Privacy, centrality, and accessibility were quantitatively measured.

For privacy, spatial connectivity was employed as the metric: higher values indicate stronger connectivity with other spaces, hence weaker privacy. Results showed that the Zhi rooms had the best privacy, while the Ren rooms, located near major passageways, performed worse.

For centrality, distances to the main hall and other ritual core spaces were calculated. Lower values signify greater proximity to the ritual core. The Ren rooms ranked best in this indicator, suggesting its spatial closeness to ceremonial and everyday lineage activities, while the Yong rooms was more peripheral.

For accessibility, the average distance to major entrances and staircases was used. Lower values indicate better circulation. The Yong rooms performed best, while the Zhi rooms was relatively disadvantaged.

Overall, each branch exhibited distinctive strengths: the Zhi rooms emphasized privacy, the Ren rooms was closer to the ritual core, and the Yong rooms was more convenient for daily circulation (

Table 2).

In conclusion, whether viewed from the physical or cultural dimension, Renhezhuang demonstrates a dynamic balance characterized by trade-offs. Different branches showed respective strengths in room numbers, daylighting, ventilation, privacy, centrality, and accessibility. This differentiated distribution formed a complementary equilibrium, reflecting both the allocation mechanism and the social logic of the lineage.

5. Discussion

5.1. The Sociological Significance of Renhezhuang

Through a comprehensive analysis of the number of rooms, daylighting and ventilation conditions, as well as privacy, centrality, and accessibility, it becomes evident that the spatial system of Renhezhuang was not merely a division of living units, but rather a spatialized practice of lineage society in the Qing dynasty.

From the perspective of physical indicators, the allocation in Renhezhuang was not absolutely equal but achieved balance through differentiated distribution. The Zhi rooms and Ren rooms occupied advantageous positions in the main and middle halls, while the Yong rooms was mainly distributed along the periphery, functioning as a form of compensation. The Ren rooms enjoyed better daylighting, the Yong rooms excelled in ventilation, and the Zhi rooms compensated for deficiencies by virtue of its larger number of rooms. This compensatory mechanism reflected the lineage’s regulatory logic under limited resources: on the one hand, adhering to the ritual hierarchy of age and seniority, and on the other, sustaining internal harmony by ensuring each branch possessed certain advantages. Light and air were not distributed equally; rather, each branch held superiority in one dimension, creating a sense of balance both psychologically and materially.

From the perspective of humanistic indicators, the three branches again demonstrated differentiated patterns. The Ren rooms, being closest to the ritual core spaces, symbolized authority and ritual centrality; the Zhi rooms had the strongest privacy, accommodating the need for individualized living; and the Yong rooms demonstrated superior accessibility, granting greater initiative in everyday social interactions. This allocation structure embodies the lineage’s value hierarchy and compromise logic—power and ritual were concentrated in central spaces, individual needs were accommodated through privacy, and everyday social interactions were facilitated by accessibility. These three elements were not contradictory but mutually reinforcing, jointly sustaining the stability of the lineage community.

From a sociological perspective, the distribution of rooms in Renhezhuang did not aim at formal equality but represented a historically situated form of practical wisdom. The core zones reflected ritual hierarchy, while the peripheral zones-maintained coexistence through compensatory allocation. This logic reveals how traditional lineage societies inscribed both power structures and ethical norms into spatial organization, ensuring long-term stability in intergenerational cohabitation. In other words, the essence lay not in absolute equality, but in balancing power, compromise, and coexistence through differentiated allocation.

The formation of this equilibrium was closely tied to the regional and historical context of Yongtai. On one hand, the long-standing principle of equal division among sons encouraged the lineage to pursue relative fairness in inheritance and partition. On the other hand, the fortified residence functioned both as a shared dwelling and a defensive system; the different branches had to cohabit within a confined space, and without reasonable allocation and compromise, internal conflict would have been inevitable. Thus, the spatial allocation in Renhezhuang was not the product of individual will, but the joint outcome of institutional norms, environmental conditions, and historical context.

5.2. Toward a Sociological Approach to Build Heritage

The study of Renhezhuang highlights that relying solely on historical records or solely on architectural remains is insufficient for uncovering the sociological significance of built heritage. Partition documents record the institutional logic and rules of allocation, while the architectural remains preserve the spatial configuration and form. However, without integrating the two, the analysis remains partial. The case of Renhezhuang demonstrates that only by situating “historical records—architectural remains” within a unified research framework, and by employing technical tools for analysis, can we fully grasp the social logic embedded in architecture. This approach not only strengthens case-based research but also points toward a more generalizable methodological path.

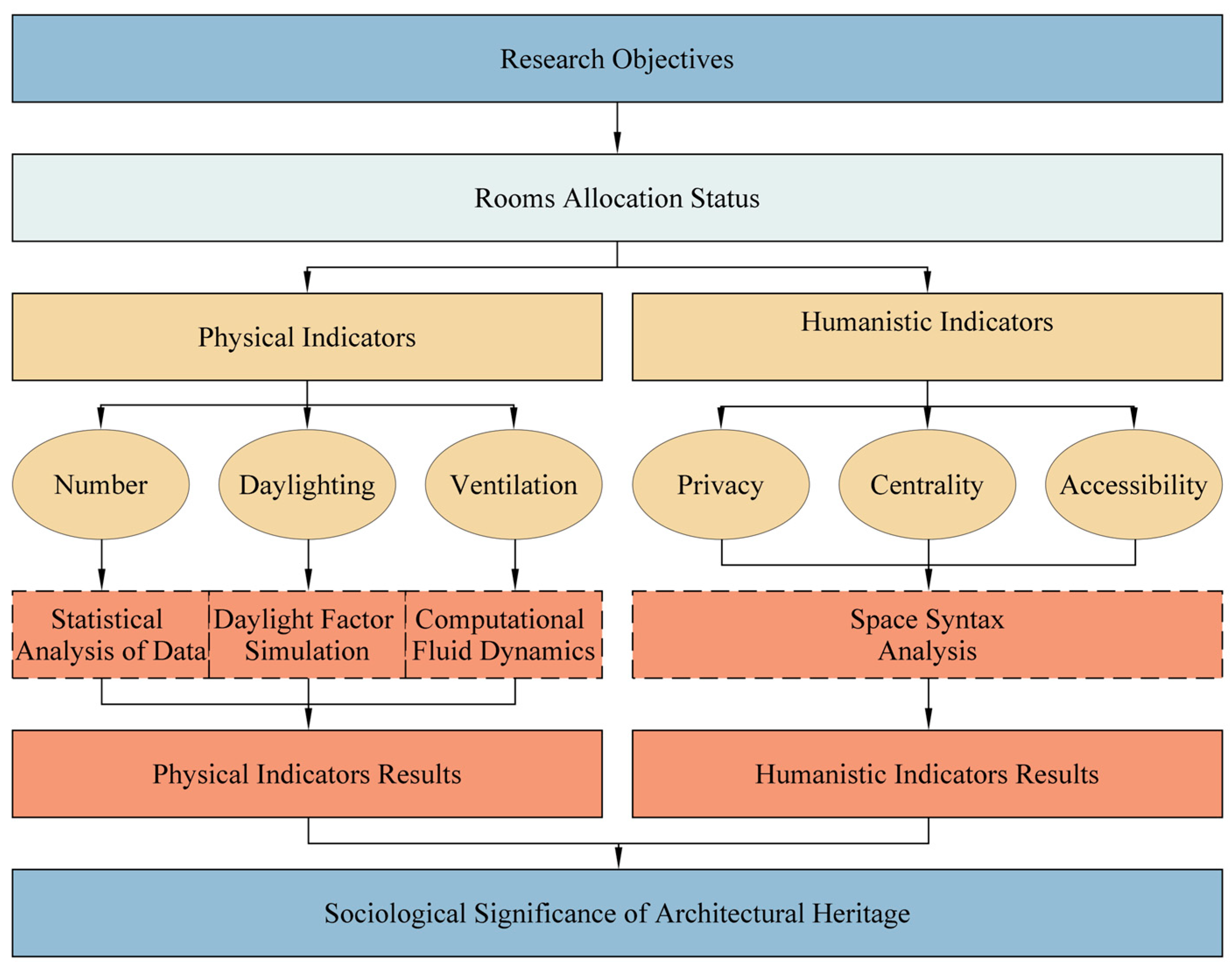

Reflecting on the research process, we have gradually formulated a methodological framework that combines historical records and architectural remains under technological support (

Figure 4).

First, the material dimension provides the foundation. Built heritage is first and foremost a physical entity; its spatial configuration, number of rooms, spatial relations, and functional divisions constitute the starting point of analysis. The overall layout of Renhezhuang embodied the ordering principles of Chinese lineage society, which cannot be apprehended without reference to the physical structure. Hence, site investigation, surveying, and spatial reconstruction formed the first step, moving the heritage from abstraction to concreteness and laying the basis for sociological interpretation.

Second, the textual dimension supplies the cultural context. Partition documents and related historical records infused architectural space with social meaning. In Renhezhuang, the partition documents strictly followed hierarchical order in their narrative, defining not only property division but also codifying a shared recognition of order and ritual. These texts transformed spatial allocation from a physical arrangement into an expression of culture and institutional logic. In this sense, textual records are the key to the socialization of space, allowing us to decode the sociological values underlying spatial distribution.

Third, the technological dimension serves as a bridge. Technology is not merely a set of analytical tools, but the mediator connecting historical records and architectural remains. Through multi-dimensional analysis, it reveals the cultural logic embedded in built heritage. In this case, space syntax allowed us to connect the hierarchical principles implicit in partition documents with the geometric configuration of space, visualizing and quantifying how lineage members were positioned in relation to one another. Daylighting and ventilation simulations compared physical conditions with practical living needs, further illustrating the practical wisdom and value hierarchy of the community. By moving from qualitative interpretation to quantitative validation, technical tools enabled a more robust reconstruction of the sociological significance of heritage.

This integrated “records–remains” approach is not limited to Renhezhuang but carries broader potential for transferability. For example, Aijingzhuang, another well-preserved fortified residence nearby, also retains partition documents. Applying the same approach could reveal how its allocation system and spatial configuration interacted, potentially highlighting both similarities and differences under the same institutional framework. More broadly, this method can be applied across different types, regions, and periods of built heritage, and even extended to the study of other forms of cultural heritage from a sociological perspective [

25]. In contexts where both cultural records and material remains are available, this approach offers a particularly effective research strategy.

In sum, the value of this exploration lies in both its conceptual insight and its methodological contribution. By linking historical records and architectural remains through technological support, the sociological significance of built heritage can be more comprehensively and clearly revealed, offering a replicable research framework for the study of historical societies and their spatial practices.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Implications

The findings from Renhezhuang illustrate that built heritage functions not only as a physical structure but also as a spatially articulated embodiment of historical and social relations. By systematically integrating partition documents and historical texts with the architectural layout of the lineage fortress, and employing analytical techniques such as space syntax, daylighting simulation, and ventilation modeling, this study deciphers the sociological logic ingrained in spatial organization. The proposed “records–remains” framework thus moves beyond singular disciplinary confines, facilitating not only architectural morphology analysis but also interpretations of how space articulates lineage structures, ethical frameworks, and cultural values.

A key contribution of this approach is its reconceptualization of built heritage value beyond material preservation or technical conservation. It highlights the synergistic interplay between physical configurations and institutional records, together constructing a coherent narrative of social order. Thus, research on built heritage transforms from an act of conservation into a methodological vehicle for historical sociology. The Renhezhuang case exemplifies how architectural heritage can offer unique insights into traditional societal structures and provides a transferable methodology for analogous studies and preservation practices.

This research further demonstrates that spatial allocation within traditional dwellings involved nuanced trade-offs rather than absolute equality. The differentiation in room numbers, environmental performance, and socio-spatial indicators—such as privacy, centrality, and accessibility—reflects a compensatory logic aimed at maintaining harmony within the lineage system under constrained resources. Such findings deepen our understanding of how premodern communities negotiated social equity through spatial design.

These insights furnish practical implications for contemporary heritage conservation, suggesting that preserving social meaning is as critical as maintaining physical fabric. The methodology introduced here offers a reproducible strategy for interpreting and sustaining the sociocultural dimensions of built heritage in varied geographical and historical contexts.

6.2. Limitations and Prospects

Although this study adopts an integrated “records–remains” approach in analyzing Renhezhuang, several limitations should be acknowledged. The relatively narrow focus on a single case restricts broader regional and typological comparisons, thereby limiting the generalizability of the findings. In addition, gaps in historical documentation—particularly the incomplete preservation of partition documents and property records—hinder a comprehensive reconstruction of ownership and social structures. Constraints related to the current condition of the architectural remains also affect the accuracy of spatial surveys and simulations, complicating efforts to fully restore the historical layout. Furthermore, intangible aspects of social meaning—including oral histories, local memories, and affective bonds—pose persistent challenges for quantification using conventional methods [

26].

Future research should address these gaps through several avenues. Expanding the selection of cases to include lineage architectures and fortified settlements across diverse regions and types would allow more nuanced comparisons of spatial-social practices under shared institutional frameworks. The integration of additional source types—such as oral histories, genealogies, local gazetteers, and public memory—could help triangulate evidence and reduce reliance on any single form of documentation. Moreover, developing dynamic analytical approaches—for instance, behavioral simulation, ethnographic observation, and anthropological interviews—would help embed spatial analysis within lived social practices, aligning research more closely with historical realities.

In summary, despite its limitations, this study demonstrates the potential of a technology-assisted “records–remains” framework to reveal sociological meanings within built heritage. It underscores the value of interdisciplinary methodologies and suggests pathways for more systematic and context-sensitive research in the future.