Investigating the Spatial Generative Mechanism of the Prepaid Building Houses on Rented Land Model in Shanghai Concessions (1938–1941)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

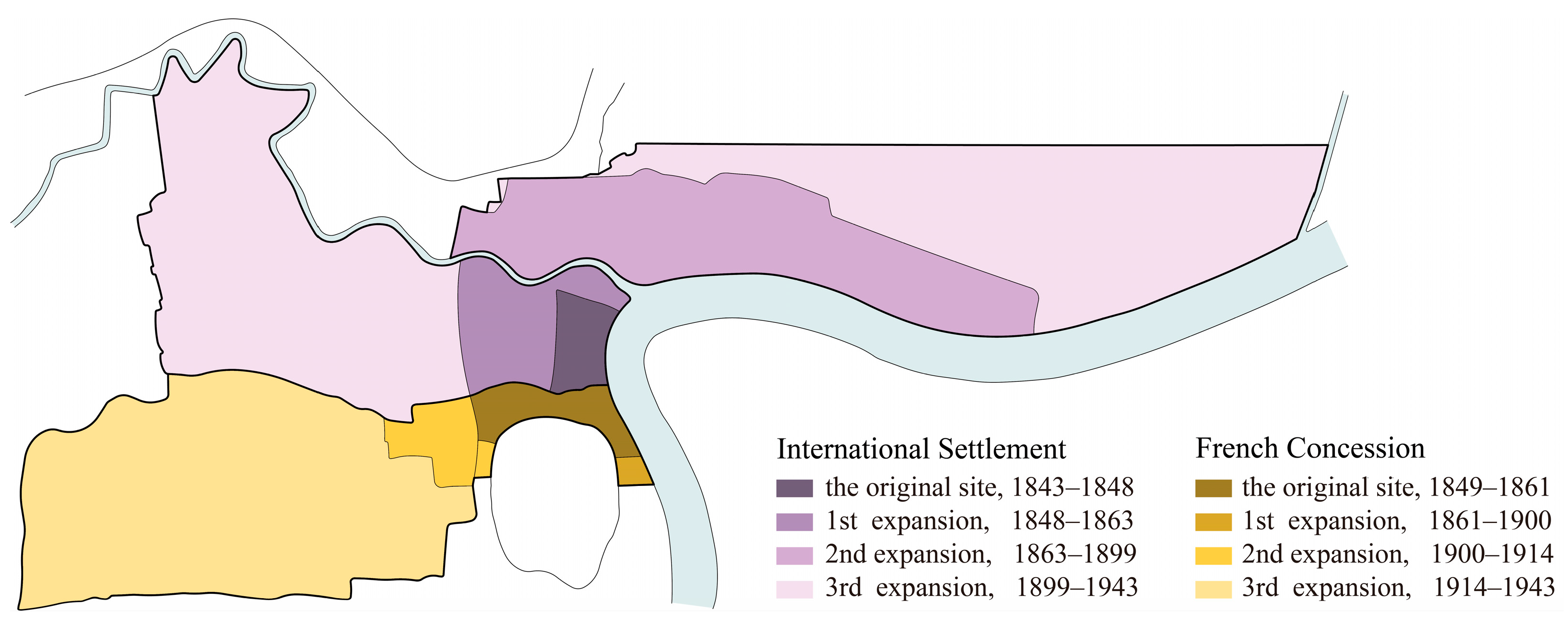

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Research Object

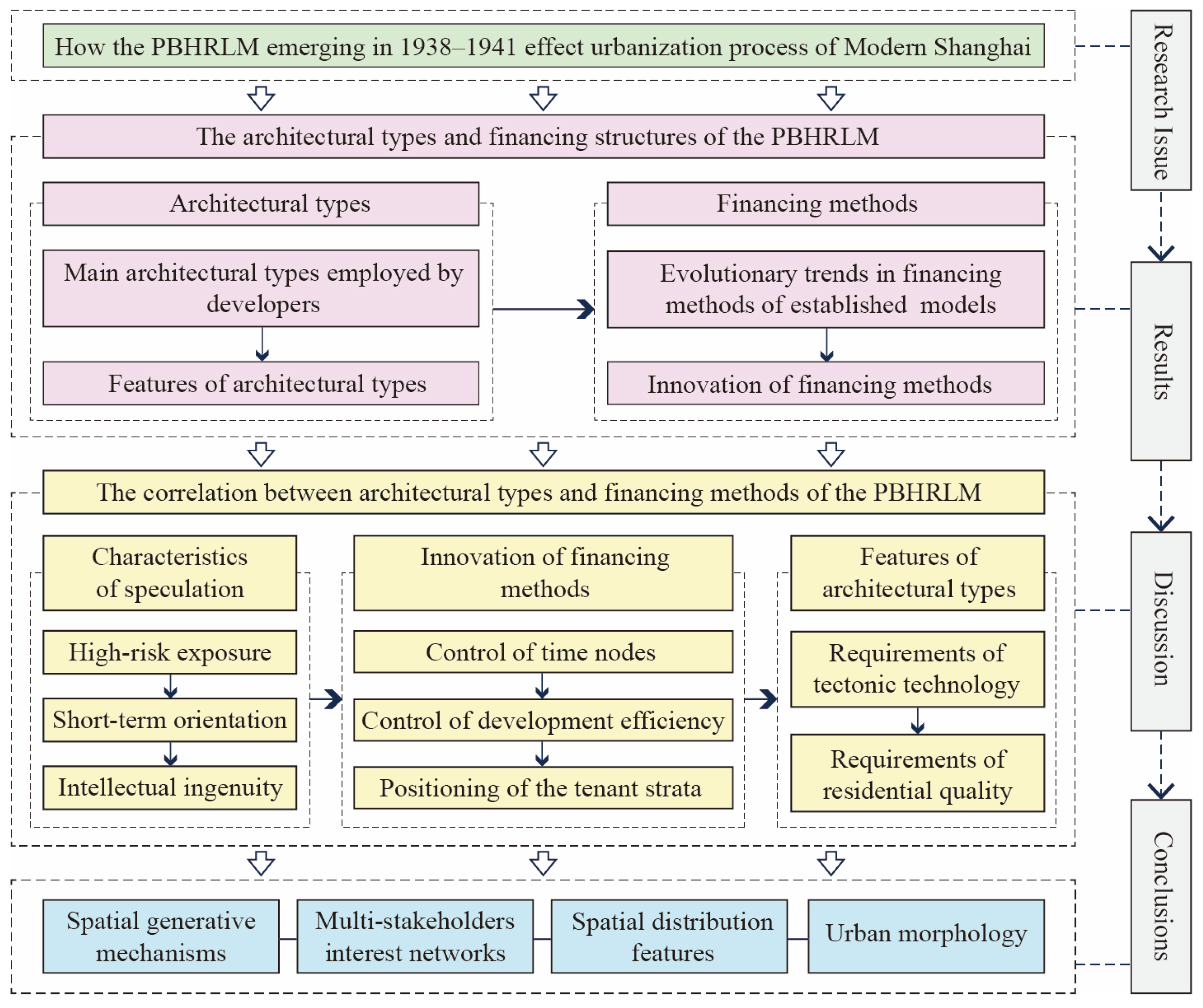

2.3. Research Framework

- (1)

- The research will proceed through two key aspects corresponding to the PBHRLM starting from the issue: its architectural types and financing methods. These two dimensions represent the model’s unique features that differentiate it from existing practices, forming the critical parts of the spatio-economic study.

- (2)

- By analyzing spatial data, this research deciphers the architecture information associated with the PBHRLM. Through statistical analysis of the acquired case data, to reveal the spectrum of the architectural types corresponding to this model, and then to distill their spatial features.

- (3)

- Drawing on financial capital theory, this research traces how financing methods evolved in Shanghai’s land development models from 1854 to 1937, using combined development and urban data. Building on this historical analysis, it then examines how the PBHRLM’s financing methods innovated compared to pre-1937 models.

- (4)

- Drawing on fundamental concepts of speculative theory, this section analyzes how the architectural types and financing methods of the PBHRLM aligned with developers’ speculative intent.

- (5)

- Summarizing five key conclusions. Firstly, it outlines the spatial generative mechanism of the PBHRLM. Building on this foundation, it refines the mutually interested mechanisms among diverse stakeholders and the spatial distribution features of the properties associated with this model. Ultimately, it identifies the defining characteristics of urban morphology in the Shanghai concessions during their later developmental phase.

2.4. Data Sources

- (1)

- Spatial data serves to investigate spatial features of architectural types, including structures, spatial configurations, and decorative craftsmanship. This information is sourced from the Shanghai Municipal Archives, the Shanghai Urban Construction Archives, online databases, and physical architecture. Primarily, the Shanghai Municipal Archives and Shanghai Urban Construction Archives house original architectural drawings from 1900 to 1943, constituting authoritative spatial data sources. Secondarily, websites such as Virtual Shanghai, MAD Space, and Pastvu provide substantial collections of historical photographs of early modern Shanghai architecture, serving to supplement drawing documentation. Furthermore, a substantial stock of historical architecture persists in Shanghai’s central districts—primarily Huangpu, Xuhui, Jingan, and Hongkou—where field surveying, photogrammetric documentation, and structured interviews supplement archival material. Caution is warranted in distinguishing original fabric from later additions or alterations.

- (2)

- Development data serves to delineate the financing methods across various land development models. These datasets are sourced from early modern Shanghai newspapers, cadastral materials issued by concession authorities, and developers’ business archives. Specifically, newspapers provide developer-published advertisements and third-party reports on land development projects—key Chinese publications include Shun Pao, Sinwen Pao, and The China Times, while prominent English-language newspapers comprise North-China Daily News, The China Herald, and The China Press. Cadastral materials document property-specific land information, with cadastral maps and cadasters periodically issued by the International Settlement and the French Concessions constituting essential sources. The developers’ operational records, primarily restored in the Shanghai Municipal Archives, furnish property management documentation.

- (3)

- Urban data primarily serves two purposes: analyzing the macroenvironmental conditions of Shanghai’s real estate market during 1938–1941 and enabling the periodization of financing method evolution from 1854 to 1937. This category comprises significantly broader resources. Beyond the previously cited Chinese and English newspapers, it includes municipal archives, such as annual reports from the International Settlement and French Concession Councils, Shanghai local chronicles, and modern-era periodicals focused on economics and municipal affairs.

2.5. Research Methodology

2.5.1. Theory Study

- (1)

- Financial capital theory

- (2)

- Speculation theory

2.5.2. Case Study

3. Results

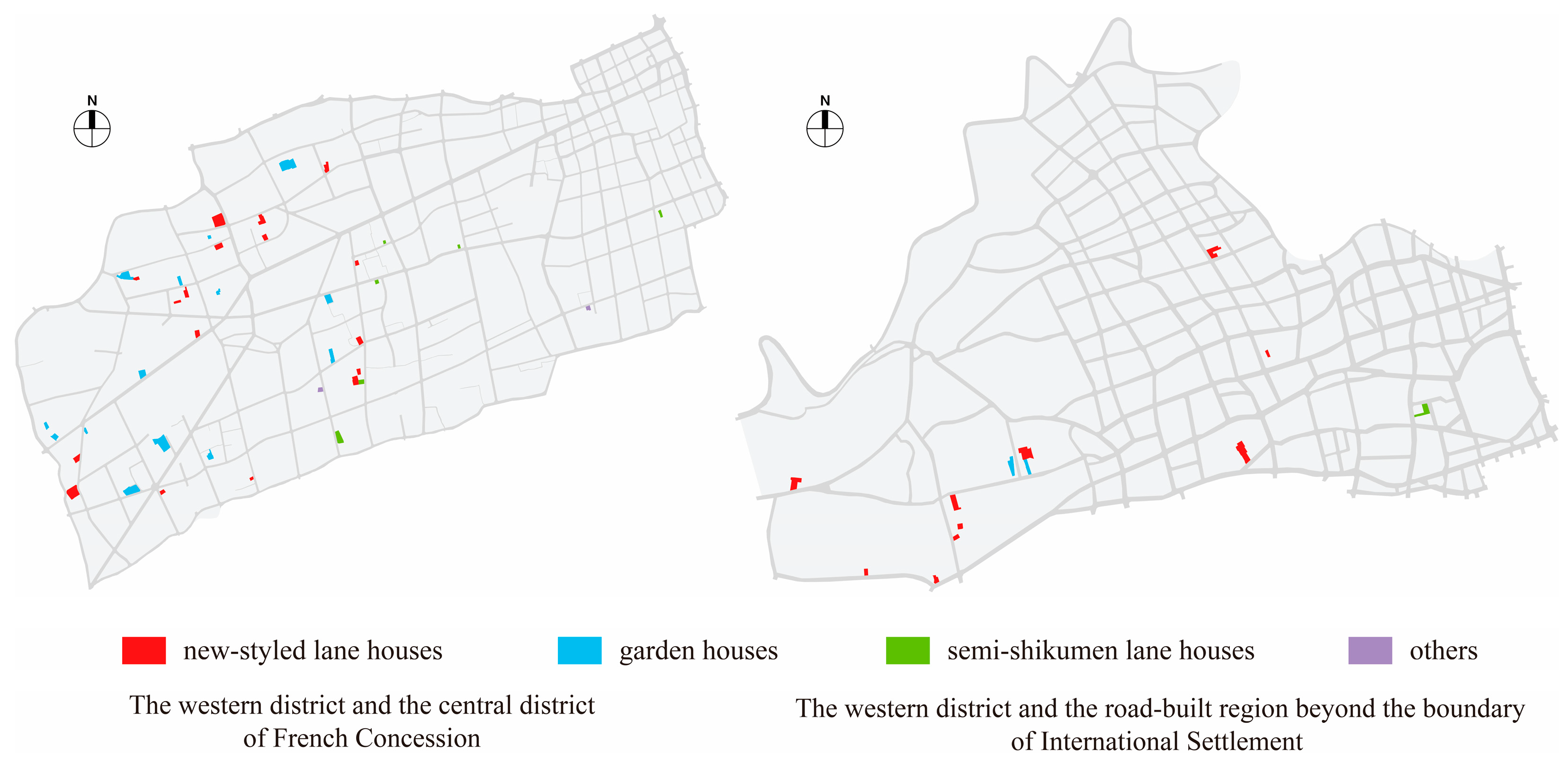

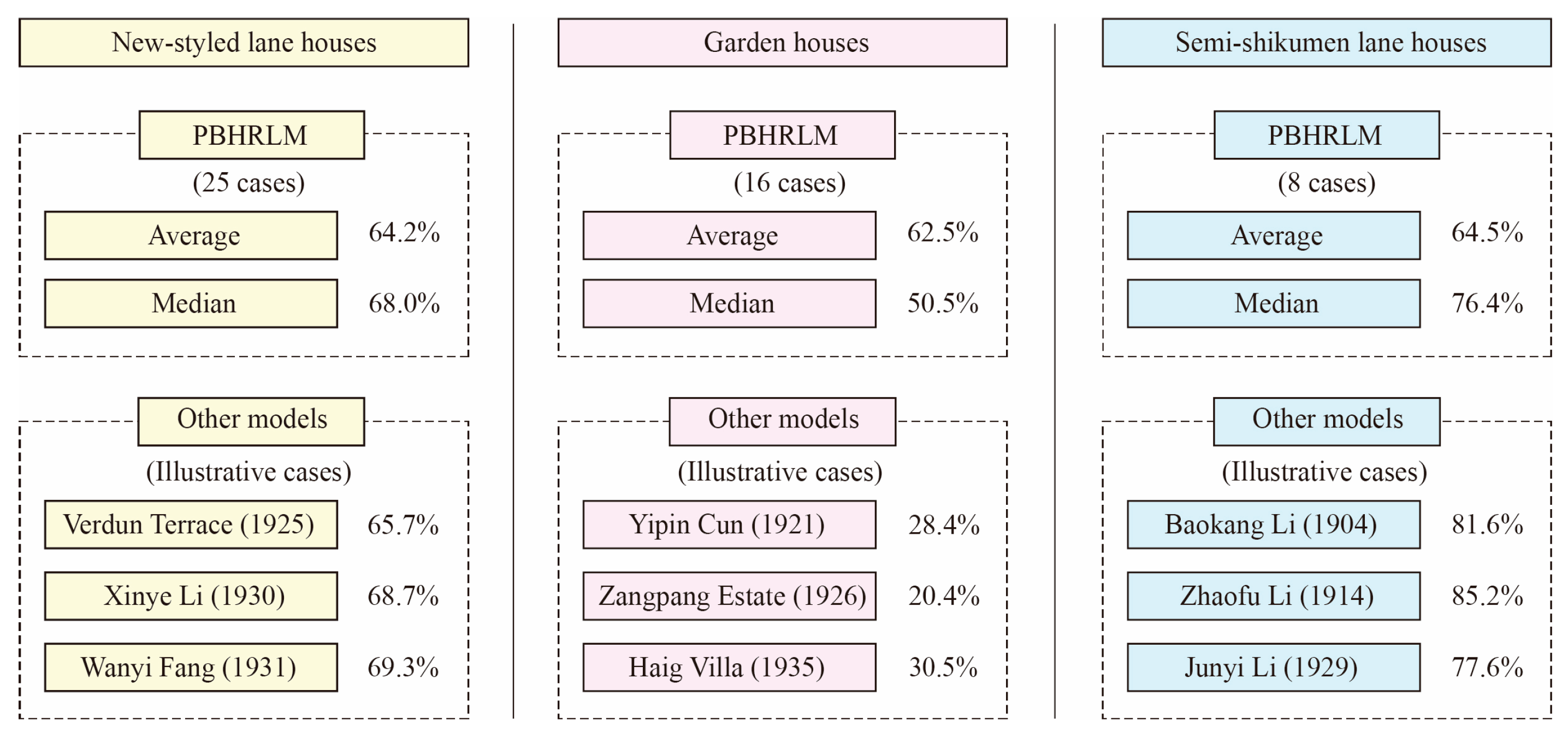

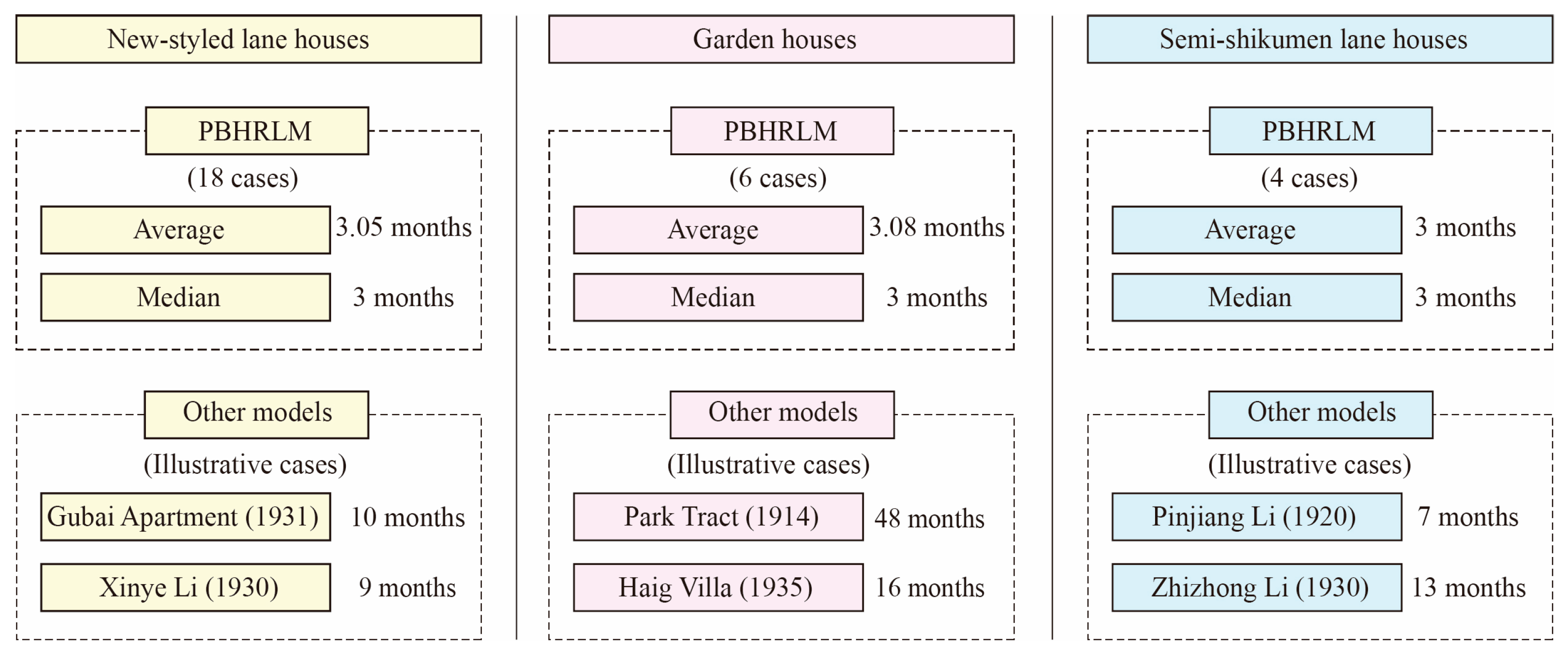

3.1. The Features of Achitectural Types in the PBHRLM

3.2. The Innovation of Financing Methods in the PBHRLM

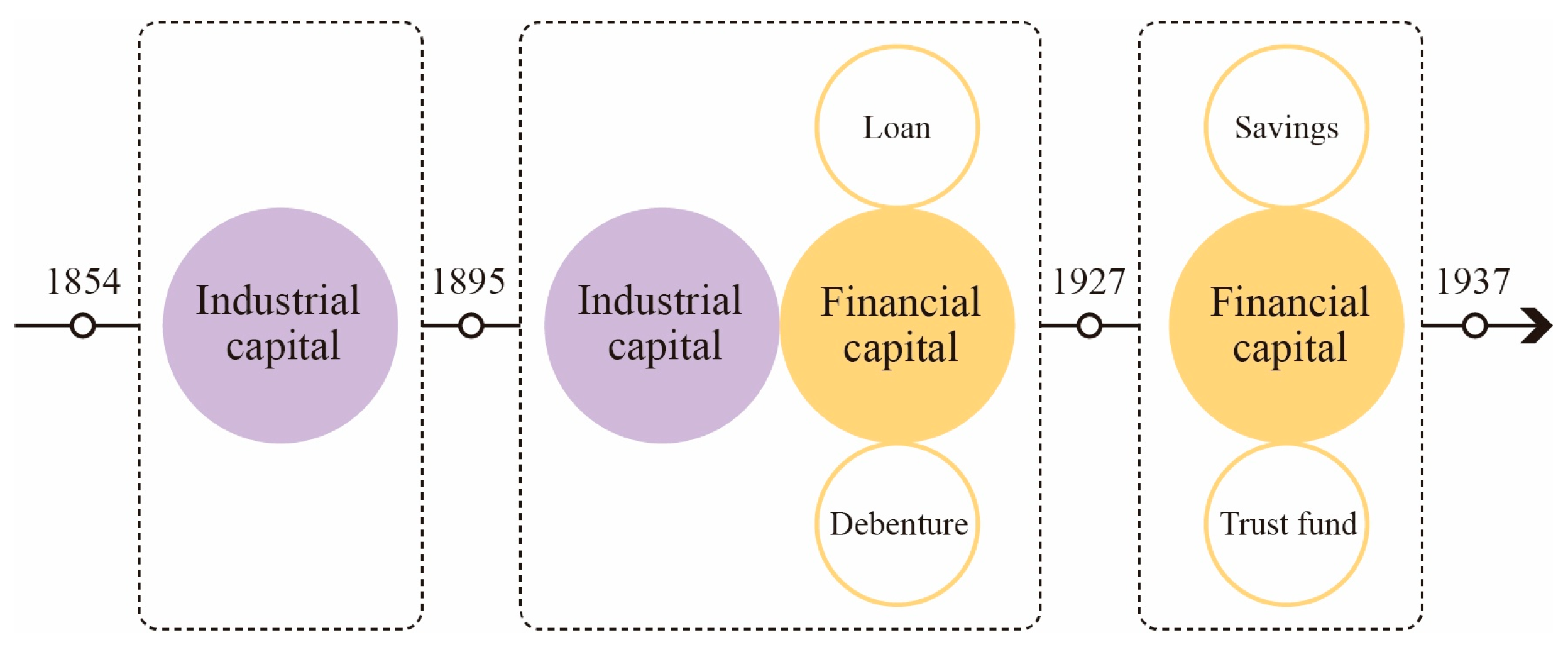

- (1)

- Industrial Capital Dominated Phase (1854–1894)

- (2)

- Financial Capital Assisted Phase (1895–1926)

- (3)

- Financial Capital Dominated Phase (1927–1937)

4. Discussion

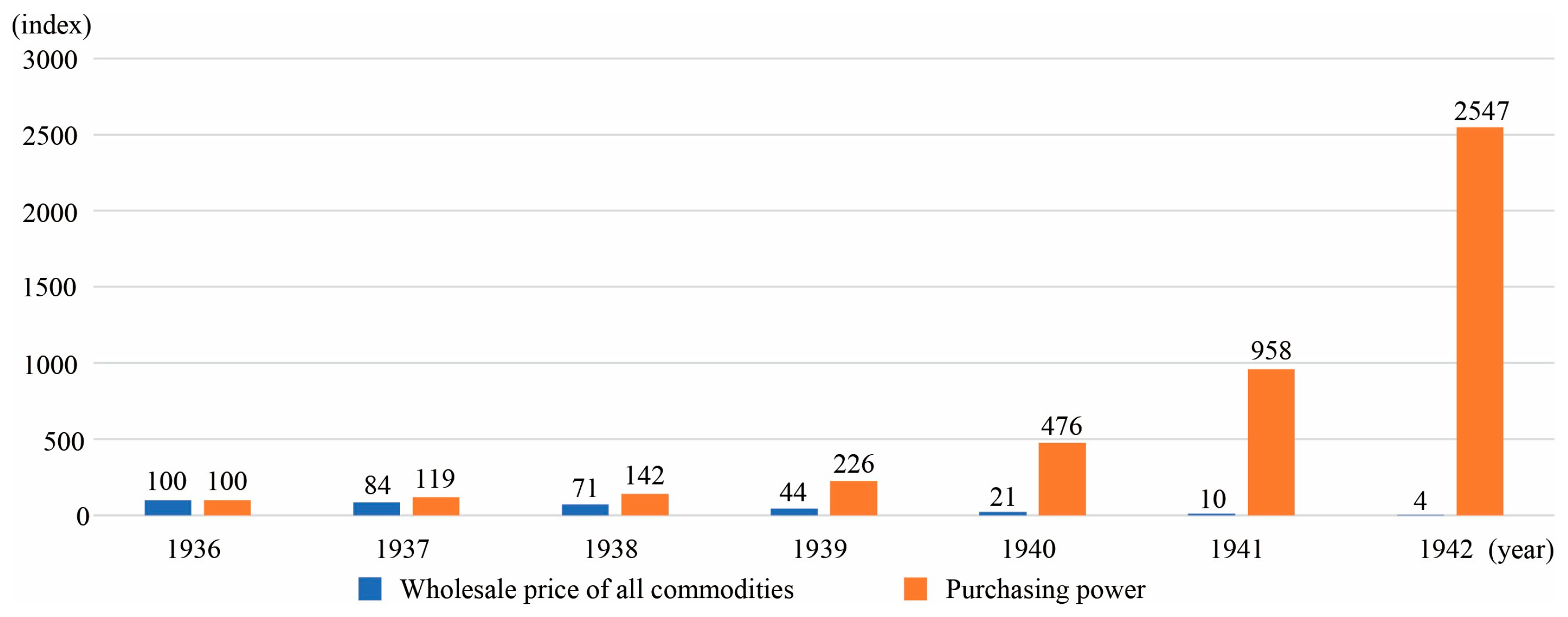

4.1. The Speculativeness of the Financing Methods in the PBHRLM

4.2. The Alignment Between Architectural Type and Financing Methods in the PBHRLM

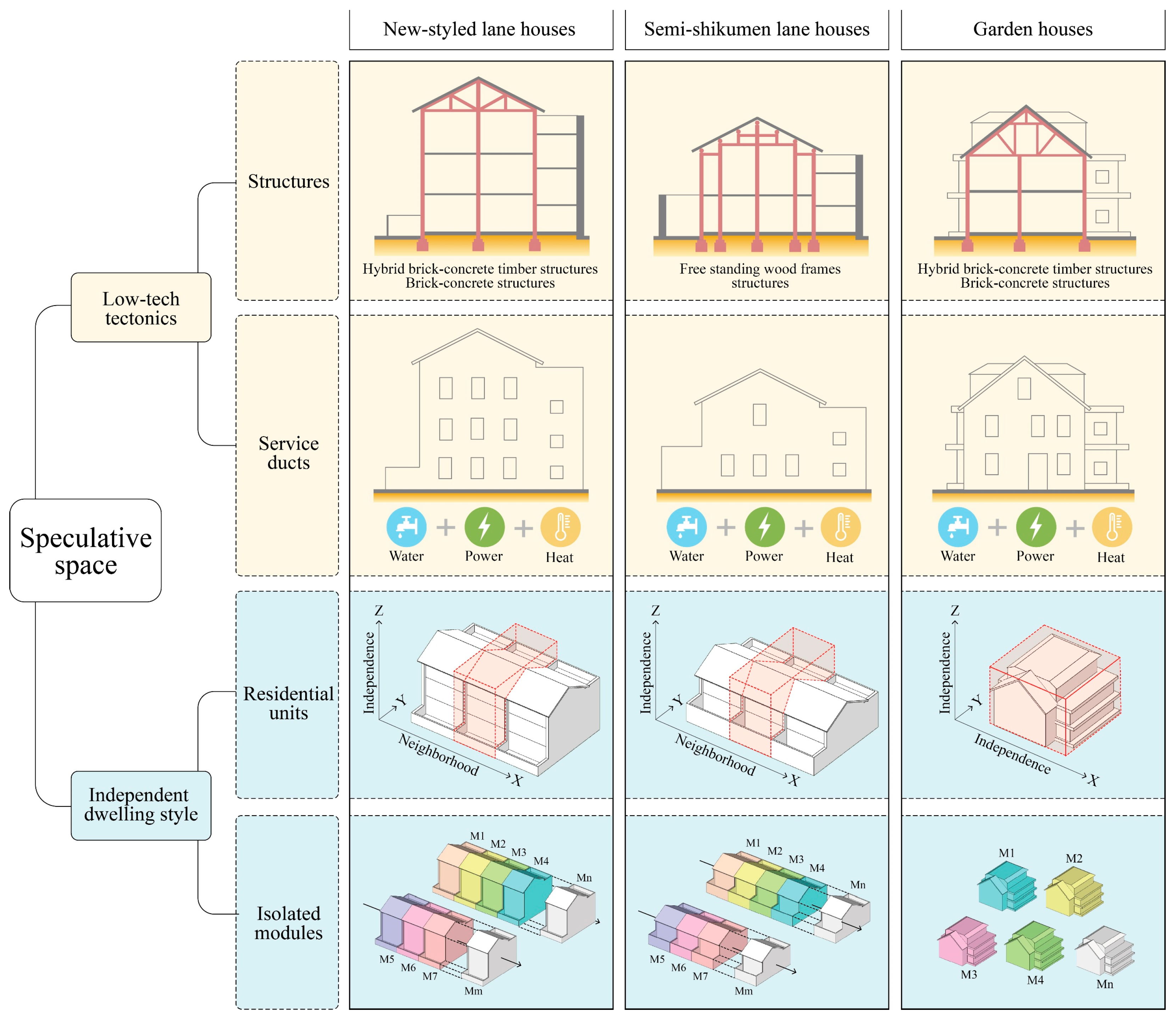

- (1)

- Low-tech tectonics

- (2)

- Independent dwelling style

4.3. Tenant’s Risk Exposure in the PBHRLM

- (1)

- Rebate gimmick

- (2)

- Financing fraud

- (3)

- Cutting corners

4.4. A Comparative Analysis of PBHRLM and Land Development Models in Other Early Modern Cities in China

- (1)

- The land development models of Qingdao

- (2)

- The land development models of Hong Kong

5. Conclusions

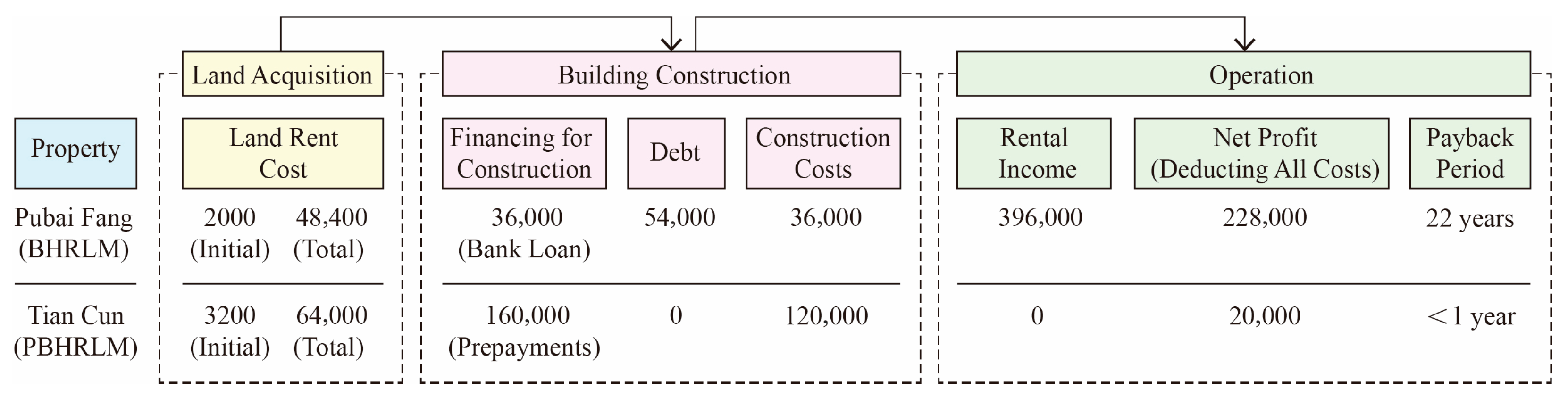

- (1)

- When employing the PBHRLM, developers enhanced development efficiency through low-tech tectonics and catered to the residential demands of the middle class by independent dwelling style. Then, the model shortened the construction duration while securing a reliable source of development capital and profits. Concurrently, constrained by profit ceilings and currency devaluation, developers were compelled to meticulously advance each development phase to mitigate the risk of being unable to make ends meet. Consequently, the spatial generative mechanism of the PBHRLM functioned as a form of spatial actuarial practice driven by speculative intent.

- (2)

- The PBHRLM facilitated a tripartite exchange of benefits. For developers, the strategic orchestration of development phases and construction of specific architectural types generated substantial progressive interest. For landowners, leasing their land provided stable rental income. For tenants, successful housing delivery by developers eliminated the burden of exorbitant key money. Consequently, this model achieved mutually beneficial outcomes for all stakeholders under the risk game.

- (3)

- The PBHRLM embodied a developmental trend wherein land development no longer needed financial capital. This innovative approach constituted a strategic adaptation by developers to secure substantial returns amidst socioeconomic turbulence. Besides that, PBHRLM’s financing methods aligned intrinsically with contemporaneous realities: currency devaluation had severely curtailed banks’ lending capacity, rendering traditional development models operationally untenable. Consequently, this innovation disrupted the established three-stage framework of financial capital theory. A novel capital formation—termed “prepaid industrial capital”—emerged, effectively supplanting financial capital’s traditional role in land development.

- (4)

- When employing the PBHRLM, developers operated within a fixed total lease term contracted with landowners. Excessive development batches would compel later-phase tenants to pay higher prepayments for disproportionately shorter lease durations, thereby reducing occupancy rates for subsequent residential units. This constraint necessitated limiting project sites to under 3 mu and development batches to two or fewer. Consequently, properties utilizing this model were characterized by small-scale, spatially dispersed configurations.

- (5)

- The prevalence of the PBHRLM demonstrated that while apartments—characterized by a collective dwelling style—emerged as a new architecture type aligned with urban development post-1930, architecture types featuring an independent dwelling style retained their vitality. Within this context, new-styled lane houses and semi-shikumen lane houses formed communities with row-upon-row layouts, while garden houses formed communities with scattered or clustered layouts. Both kinds of communities expanded extensively in the western district of the concessions due to surging housing demand, collectively shaping the urban morphology: heterogeneity in the west and homogeneity in the east. It corresponded directly to the east–west residential segregation of the middle/upper classes and the lower class.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PBHRLM | Prepaid Building Houses on Rented Land Model |

| BHRLM | Building Houses on Rented Land Model |

| BHPLM | Building Houses on Purchased Land Model |

Appendix A

| Property Name | Prepayment Date (Batch) | Prepayment Value (Yuan) | Duration Per Batch (Month) | Tenancy (Year) | Number of Storeys | Types | Plot Area (mu) | Building Footprint (mu) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jing Cun | 1st: Aug. 1938 2nd: Sep. 1938 | 1st: 4800–5300 2nd: 2400 | 1st: 4 2nd: / | 18 | 2–3 | garden houses | 1.168 | 0.677 |

| Yi Cun | 1st: Jan. 1939 2nd: Aug. 1939 | 1st: 8200–8800 2nd: 9000 | 4 | 20 | 3 | new-styled lane houses | 2.618 | 1.909 |

| Jufu Xin Cun | 1st: Jun. 1938 2nd: Aug. 1938 3rd: Oct. 1939 | 1st: 4200 2nd: 12,000 3rd: 27,000 | 1st: / 2nd: 3 3rd:/ | 20 | 3 | garden houses | 4.427 | 2.101 |

| Younin Cun | 1st: Jul. 1938 2nd: Aug. 1938 | 1st: 2550 2nd: 2790–5450 | 1st: 3 2nd: 3 | 20 | 2–3 | semi-shikumen lane houses | 4.539 | 3.425 |

| Youhua Cun | Mar. 1939 | 8230–10,020 | 4 | 19 | 3 | new-styled lane houses | 3.510 | 2.211 |

| Huiling Cun | May. 1939 | 6000–6700 | 4 | 6 | 2 | new-styled lane houses | 0.926 | 0.512 |

| Youli Cun | Nov. 1939 | 7560–10,000 | / | 19 | 2–3 | garden houses | 7.131 | 1.429 |

| Tongfu Xin Cun | 1st: Jun. 1939 2nd: Jul. 1940 | 1st: 7500–8400 2nd: / | / | 20 | 3 | new-styled lane houses | 1.559 | 0.909 |

| Yi Cun | 1st: / 2nd: Jun. 1938 | 1st: / 2nd: 7400 | 1st: 3 2nd: 4 | 22 | 3 | new-styled lane houses | 7.687 | 5.476 |

| Yunshang Cun | Jul. 1939 | 5900–6000 | 2 | 20 | 2 | garden houses | 1.452 | 0.925 |

| Yangzi Cun | Sep. 1938 | 1800 | 2 | 15 | 2 | new-styled lane houses | 2.276 | 1.523 |

| Rui Cun | Mar. 1939 | 5800 | 2 | 20 | 3 | garden houses | 1.452 | 0.823 |

| unknown | Nov. 1938 | 5500 | 3 | 20 | 2–3 | semi-shikumen lane houses | 0.698 | 0.470 |

| Kangjian Cun | Oct. 1938 | 2900–4500 | / | 20 | 2 | new-styled lane houses | 1.676 | 1.118 |

| Tian Cun | 1st: Jul. 1938 2nd: Aug. 1938 | 1st: 5550 2nd: 6350 | 1st: 3 2nd: / | 20 | 2–3 | new-styled lane houses | 5.362 | 3.263 |

| Jing Yuan | Jul. 1939 | 3300 | / | 20 | 2 | garden houses | 5.387 | 2.885 |

| Liulin Cun | Aug. 1939 | 11,000 | 4 | 20 | 3 | garden houses | 1.927 | 0.483 |

| Xinhe Villa | May. 1940 | 42,000 | 2 | 20 | 3 | new-styled lane houses | 2.671 | 1.873 |

| Shuntian Cun | May. 1939 | 5000–8500 | / | 10 | 2 | semi-shikumen lane houses | 13.156 | 10.054 |

| Zhenpan Xiao Zhu | Oct. 1938 | 12,500–14,000 | / | 20 | 2 | garden houses | 3.593 | 2.191 |

| Maolin Xin Cun | Aug. 1939 | 16,000–18,000 | 3 | 20 | 3 | new-styled lane houses | 2.484 | 1.995 |

| Anle Cun | Aug. 1939 | / | 2 | 3 | 3 | new-styled lane houses | 1.588 | 1.042 |

| An Cun | 1st: Sep. 1938 2nd: Oct. 1938 | 1st: 3200–4600 2nd: 3600–4800 | / | 20 | 2 | garden houses | 0.995 | 0.721 |

| Yian Cun | Aug. 1938 | 1600 | / | 10 | 3 | new-styled lane houses | 1.785 | 1.099 |

| Fushou Xin Cun | Aug. 1938 | 3000 | / | 20 | 3 | new-styled lane houses | 2.135 | 1.406 |

| Baiji Xin Cun | Aug. 1939 | 2600 | 2.6 | 10 | 2 | other | 1.272 | 0.890 |

| unknown | Nov. 1938 | 6950 | / | 20 | 3 | garden houses | 4.324 | 2.437 |

| Xinyu Cun | Jul. 1938 | 4200 | 3 | 20 | 2–3 | new-styled lane houses | 7.726 | 5.913 |

| Dalu Xin Cun | 1st: May. 1939 2nd: Aug. 1939 3rd: Oct. 1939 | 1st: 6300 2nd: 7100 3rd: 7500 | 1st: / 2nd: 3.5 3rd: 3 | 20 | 3 | other | 1.513 | 1.203 |

| Rongkang Villa | Dec. 1940 | 30,000 | 3 | 20 | 3 | new-styled lane houses | 8.695 | 6.524 |

| Yangzi Villa | Oct. 1938 | 1800 | 2 | 15 | 2 | new-styled lane houses | 5.434 | 4.274 |

| Anhe Xin Cun | Dec. 1938 | 500–900 | / | 10 | 2 | new-styled lane houses | 5.343 | 3.871 |

| Jufu Cun | Sep. 1939 | 7000–12,000 | 2.5 | 20 | 3 | new-styled lane houses | 0.802 | 0.542 |

| Dafang Xin Cun | Jun. 1939 | 4500 | 2.5 | 18 | 3 | new-styled lane houses | 3.749 | 2.635 |

| unknown | Apr. 1939 | 13,000 | / | 10 | 3 | garden houses | 3.535 | 1.421 |

| Hatong Villa | Oct. 1941 | / | / | 18 | 3 | new-styled lane houses | 8.213 | 5.317 |

| Jing Cun | Jan. 1940 | 7500 | / | 14 | 3 | semi-shikumen lane houses | 1.382 | 1.055 |

| Fu Cun | Mar. 1940 | 17000 | / | 18 | 3 | new-styled lane houses | 1.941 | 1.389 |

| Heyue Cun | Aug. 1939 | 6700 | 4 | 15 | 3 | new-styled lane houses | 1.236 | 0.889 |

| He Cun | 1st: Oct. 1939 2nd: May. 1940 | 1st: 6800 2nd: 8000 | 3 | 15 | 3 | new-styled lane houses | 2.480 | 1.469 |

| Dinhe Cun | Mar. 1939 | 2000–2200 | / | 10 | 2 | semi-shikumen lane houses | 1.245 | 0.775 |

| Ladu Xin Cun | Jan. 1939 | 3550 | 3 | 18 | 2 | semi-shikumen lane houses | 2.005 | 1.607 |

| Yufeng Cun | Sep. 1939 | 5000 | / | 19 | 2 | garden houses | 0.824 | 0.502 |

| Lan Cun | 1st: Oct. 1939 2nd: Jan. 1940 | 1st: 4000 2nd: 9000 | 3 | 15 | 2 | semi-shikumen lane houses | 0.608 | 0.467 |

| Panmai Xin Cun | Sep. 1938 | 5276–5973 | / | 15 | 3 | garden houses | 10.061 | 4.390 |

| Xinxiang Cun | Dec. 1939 | 6000 | 7 | 20 | 2 | semi-shikumen lane houses | 1.000 | 0.820 |

| Zhonghe Garden | Oct. 1941 | 126,000 | / | 23 | 3 | garden houses | 1.763 | 0.597 |

| Yihe Cun | Dec. 1941 | 25,000 | 3 | 15 | 3 | new-styled lane houses | 1.836 | 1.257 |

| Chunshen Fang | Oct. 1938 | 1150–1200 | 2 | 10 | 2 | new-styled lane houses | 2.348 | 1.766 |

| Meilong Cun | Oct. 1939 | / | / | 20 | 3 | new-styled lane houses | 2.338 | 1.294 |

| Zhuyin Villa | Nov. 1940 | / | / | 20 | 3 | garden houses | 3.679 | 0.882 |

| Anhua Fang | Sep. 1939 | / | 3 | 17 | 3 | garden houses | 2.731 | 0.637 |

References

- Anonymous. Recently Built Houses. Shun Pao, 15 July 1882; Sect. 3. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Bao, S. Business tactics of foreign property developers. In Real Estate Business in Early Modern Shanghai; Culture and History Committee, Shanghai Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference: Shanghai, China; Shanghai People’s Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 1990; p. 155. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. Shanghai Real Estate Encyclopedia, 1st ed.; Shanghai Real Estate Research Institute: Shanghai, China, 1933; pp. 77–78. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H. How I operate a property business by model of building houses on rented land. In Real Estate Business in Early Modern Shanghai; Culture and History Committee, Shanghai Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference: Shanghai, China; Shanghai People’s Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 1990; pp. 52–60. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xu, B. Chronicle of the Development Process at Tian Cun Property on Yuyuan Road by Employing the Model of Building Houses on Rented Land. In Real Estate Business in Early Modern Shanghai; Culture and History Committee, Shanghai Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference: Shanghai, China; Shanghai People’s Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 1990; pp. 61–66. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S. Great World, Shanghai’s Iconic Entertainment Complex. Shanghai Real Estate 1997, 1, 46–47. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J. History and Theory of Urban Real Estate in China, 1st ed.; Nankai University Press: Tianjin, China, 1994; p. 75. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lu, W.; Xu, B. Shanghai Real Estate Chronicle, 1st ed.; Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences Press: Shanghai, China, 1999; pp. 189–190. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y. On the Chinese real estate corporations in Shanghai during the anti-Japanese War. Hist. Res. Anhui 2011, 13, 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G. Land Adjustment and Self-Organized Developlement in Early Modern Shanghai Foreign Settlements. Time + Archit. 2018, 6, 126–130. [Google Scholar]

- Mou, Z. Thomas Hanbury Family’s Investment in Real Estate in Shanghai and Its Mode of Management: An Investigation Based on Official Title Deeds, 1861–1933. Hist. Rev. 2024, 4, 67–81. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T. Compilation of Sino-Foreign Historical Treaties and Agreements (1840–1949), 1st ed.; Joint Publishing: Beijing, China, 1957; Volume 1, pp. 30–36. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shi, M.; Ma, C. Shanghai Concessions Chronicle, 1st ed.; Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences Press: Shanghai, China, 2001; pp. 96–101. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Feetham, R. Report of the Hon. Richard Feetham to the Shanghai Municipal Council; SMC: Shanghai, China, 1931; Volume 1, p. 679. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J. Demographic and Economic Transformations in Shanghai Concession. J. Soc. Sci. 2001, 6, 68–72. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H. Pathological Development of the Real Estate Industry. Shun Pao, 15 December 1938; Sect. 12. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. The Anatomy of Hyperinflation in Wartime Shanghai. Xianshi Pao 1938, 21, 5. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zou, Y. Demographic Transformations in Modern Shanghai, 1st ed.; Shanghai People’s Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 1980; pp. 90–91. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C. On the Legal Regulation of Prepaid Consumption in China. Theory Pract. Financ. Econ. 2017, 38, 140. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Pathological Expansion of the Model of Building Houses on Rented Land. Shun Pao, 14 May 1939; Sect. 11. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Marx, K.H. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, 2nd ed.; People’s Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2004; Volume 2, p. 31. [Google Scholar]

- Hilferding, R. Finance Capital, 1st ed.; The Commercial Press: Beijing, China, 2017; p. 253. [Google Scholar]

- Ulyanov, V.I. Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism, 2nd ed.; People’s Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2014; p. 39. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. The Limit to Capital, 1st ed.; Verso: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1999; 317p. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C. Speculative Economics, 1st ed.; China Social Sciences Press: Beijing, China, 2003; pp. 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu Yung Tsu & Co. Commissioned Development of the Second Batch of Foreign Houses Named Yi Cun. Shun Pao, 12 December 1938; Sect. 7. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Daqing Co. 4200 Yuan for 20 Years in High-Class Foreign Houses. Sinwen Pao, 12 June 1938; Sect. 20. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Daqing Co. Three-Storey Foreign Houses in a Prime Location. Sinwen Pao, 19 July 1938; Sect. 18. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Daqing Co. Second Batch of Economy-Grade Three-Storey Houses. Sinwen Pao, 25 August 1939; Sect. 22. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Daqing Co. Five Three-Storey, Three-Compartments Garden Houses. Sinwen Pao, 4 October 1939; Sect. 18. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tai Kee Co. Attorney Shen Yide, Perennial Legal Counsel to Tai Kee Co., Declares Acquisition of Surface Rights to Younin Cun. Shun Pao, 22 April 1939; Sect. 5. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tai Kee Co. Addition of Two Premium Residential Typologies in Younin Cun in French Concession. Sinwen Pao, 26 September 1938; Sect. 26. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tai Kee Co. Notice of Completion for Yunin Cun on Route Rene Delastre. Shun Pao, 1 May 1939; Sect. 6. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Parker, W. Real Estate Problem Found More Complex. The China Press, 18 December 1936; Sect. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z. The Formation of Shanghai as a Modern Industrial Center. Hist. Rev. 1987, 4, 114–122. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, R. Modern Economic History of Shanghai 1843–1894, 1st ed.; Shanghai People’s Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 1994; Volume 1, p. 446. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X. Borrowers, Lenders, and Loan Agreements: International Practices in Lending Relationships, 1st ed.; China Financial Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2000; p. 1. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q. Construction Project Finance, 1st ed.; Huazhong University of Science & Technology Press: Wuhan, China, 2010; p. 73. [Google Scholar]

- Shanghai Land Investment Company. Limited. Report of Directors. The North-China Herald and Supreme Court & Consular Gazette, 21 May 1890; Sect. 18.

- Guo, Y. Study on the Essential Characteristics of Debenture of the Alien Enterprise in Modern China. Hist. Rev. 2019, 6, 138–149. [Google Scholar]

- The Anglo French Land Invest Co., Ltd. The North-China Daily News, 13 June 1908; Sect. 8.

- Hong, J. Shanghai Financial Chronicle, 1st ed.; Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences Press: Shanghai, China, 2003; p. 118. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Wen, Y. Modern Savings Theory and Practice, 1st ed.; Tianjin Science and Technology Press: Tianjin, China, 1994; p. 4. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cao, J. Investment Trust Studies, 2nd ed.; Shanghai University of Finance & Economics Press: Shanghai, China, 2012; p. 4. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Financial Research Division, Shanghai Branch of the People’s Bank of China. Historical Records of Kincheng Bank, 1st ed.; Shanghai People’s Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 1983; pp. 101–102. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Development of the Real Estate Department at the National Commercial Bank. Shun Pao, 4 January 1930; Sect. 20. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Continental Bank. Incoming Correspondence to the Head Office of the Continental Bank Regarding the Loan Agreement Between the Ministry of Communications and the Bank of Shanghai, Establishment of a Harbin Sub-Branch, Construction of Commercial-Residential Properties by the Hankou Branch, Warehouse Construction Contracts in Shanghai, Establishment of a Trust Sub-Department in Shanghai, Agenda Items for the Directors and Supervisors’ Joint Meeting, Personnel Changes, Real Estate Mortgage Loans, As Well As Construction Payments and Progress Reports [Special Volume]; Shanghai Archives: Shanghai, China, 1930; p. Q266-1-63. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Joint Savings Society. General Correspondence from the Joint Savings Society of the Joint Savings Society Regarding the Organizational Establishment of Its Trust Department, Employee Savings Fund Dividends, and Formal Invitations to Appraisal Commissioners for Inspection Duties, As Well As Official Documents Exchanged Between the Head Office, Trust Headquarters, and Tianjin Branch Concerning the Payment of Deposit Income Tax [Special Volume]; Shanghai Archives: Shanghai, China, 1936; p. Q267-1-102. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Joint Savings Society. Correspondence from the Head Office of the Joint Savings Society of the Joint Savings Society to Its Shanghai Branch, Encompassing Matters Related to Collateral Substitution, Loan Recall, Coal Mining Company Bond Transactions, Establishment of Preparatory Committees for the International Hotel, Revisions to Shanghai Branch’s Final Accounting Procedures, Personnel Affairs, Along with Telegraph Communications Between the Chief and Deputy Directors [Special Volume]; Shanghai Archives: Shanghai, China, 1932; p. Q267-1-71. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Defaulting on Land Rent by the Lessee of Yi Cun. Shun Pao, 6 May 1940; Sect. 11. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, P. Inflation in Pre-1949 China, 1st ed.; Joint Publishing: Beijing, China, 1963; pp. 18–19. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Timber Prices Have Increased Twentyfold Compared to Earlier Levels. The Shanghai Press, 24 November 1941; Sect. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Pan, J. Shanghai Price Chronicle, 1st ed.; Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences Press: Shanghai, China, 1998; p. 469. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Customs Tariff Commission. Index number of wholesale prices in Shanghai. Prices Price Indexes Shanghai 1944, 4, 1. [Google Scholar]

- The Continental Bank. The Correspondence Between the Continental Bank, Head Office, and Related Parties Regarding the Purchase of Land on Avenue Haig and Route Camille Lorioz for the Construction of Haig Villa and Its Sale [Special Volume]; Shanghai Archives: Shanghai, China, 1931; p. Q266-1-639. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Joint Savings Society. Letter from the Shanghai Branch of the Joint Savings Society to the Head Office Regarding the Granting of Loans to the Ministry of Finance and Others, the Collection of Overdue Debts, Borrowing from Foreign Banks, the Purchase of Land, the Construction of Buildings, Final Account Distribution, Donation of Funds, the Application for Savings Certificates, Personnel Matters, Salaries, and Welfare Benefits [Special Volume]; Shanghai Archives: Shanghai, China, 1931; p. Q267-1-62. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Pinjiang Guild. The Diary of Pinjiang Guild [Special Volume]; Shanghai Archives: Shanghai, China, 1922; p. Q118-4-27. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Pan, G. Shanghai Municipal Government Directive No. 916. Shanghai Munic. Gov. Gaz. 1931, 82, 57–60. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- National Commercial Bank. Annual Operational Reports by Branches and Departments of National Commercial Bank (Part III) [Special Volume]; Shanghai Archives: Shanghai, China, 1931; p. Q268-1-47. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. News Brevities. The Shanghai Press, 15 August 1919; Sect. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Jianhua Co. Second Batch of Commissioned Foreign Houses. Sinwen Pao, 29 August 1938; Sect.18. [Google Scholar]

- An Hua Realty Co. Second Batch of Newly Built Western Houses for Low-Cost Rental. Sinwen Pao, 3 September 1938; Sect.25. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Office (China Branch). Table of Average Monthly Real Income for Workers Across Various Sectors in Shanghai, 1936–1940. Int. Labour News 1941, 8, 25–26. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, W. The Rise of Urban Society: The Middle Class and Professional Associations in Modern Shanghai, 1st ed.; Shanghai Lexicographical Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 2017; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Shanghai Municipal Council. Report by the Shanghai Municipal Council on the Cost of Living for Foreign Staff in Shanghai [Special Volume]; Shanghai Archives: Shanghai, China, 1942; p. U1-10-152. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Brief Abstracts. Film Daily, 19 August 1941; Sect. 3. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Y. Charged with Bigamy. Shun Pao, 12 July 1940; Sect. 10. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Dalu Real Estate Co. Dalu Xin Cun. Shun Pao, 27 May 1939; Sect. 20. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Dalu Real Estate Co. Dalu Xin Cun. Shun Pao, 4 August 1939; Sect. 13. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Dalu Real Estate Co. Three-Storey, Double-Bay Dalu Xin Cun. Sinwen Pao, 20 October 1939; Sect. 18. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yao Xinji Tenancy Co. Building Houses on Rented Land of Xinyu Cun. Sinwen Pao, 19 July 1938; Sect. 1. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Dajian Co. Book Now for Fine Houses. Sinwen Pao, 19 November 1938; Sect. 30. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Prepayment Collected Long Ago, Yet the House Remains Uncompleted. Shun Pao, 23 December 1938; Sect. 11. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Permit Application Thrice Rejected. Shun Pao, 24 December 1938; Sect. 11. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Warner, T. Die Planung und Entwicklung der Deutschen Stadtgründung Qingdao (Tsingtau) in China, 1st ed.; Southeast University Press: Nanjing, China, 2011; pp. 71–195. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, B. A Century of Hong Kong Real Estate Development, 1st ed.; Orient Publishing Center: Shanghai, China, 2007; pp. 15–67. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

He, W.; Li, C.; Zhu, L. Investigating the Spatial Generative Mechanism of the Prepaid Building Houses on Rented Land Model in Shanghai Concessions (1938–1941). Buildings 2025, 15, 3447. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15193447

He W, Li C, Zhu L. Investigating the Spatial Generative Mechanism of the Prepaid Building Houses on Rented Land Model in Shanghai Concessions (1938–1941). Buildings. 2025; 15(19):3447. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15193447

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Wen, Chun Li, and Longbin Zhu. 2025. "Investigating the Spatial Generative Mechanism of the Prepaid Building Houses on Rented Land Model in Shanghai Concessions (1938–1941)" Buildings 15, no. 19: 3447. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15193447

APA StyleHe, W., Li, C., & Zhu, L. (2025). Investigating the Spatial Generative Mechanism of the Prepaid Building Houses on Rented Land Model in Shanghai Concessions (1938–1941). Buildings, 15(19), 3447. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15193447