1. Introduction

Space is not merely a physical layout; it is a dynamic structure embodying a network of historical, cultural, and social relationships. In this study, the term “traditional house” is used to refer to residential types that have developed under specific historical, climatic, and societal conditions, produced through largely anonymous craftsmanship, and sustained through local construction techniques [

1,

2,

3]. Beyond being a simple architectural form, a traditional house is a socio-spatial system where typology, morphologic logic, and material usage interact: plan organization (sofa arrangement, courtyard/overhang relations), construction materials (stone, timber, and brick), and decorative elements collectively embody cultural and historical continuity.

Traditional houses, as one of the most prominent examples of this multilayered structure, express the lifestyles, social norms, and cultural priorities of their respective eras through space. Indeed, the idea that traditional houses reflect socio-cultural structures has been widely accepted in the architectural and cultural geography literature, with pioneering studies by Rapoport and Lawrence, and has been the subject of numerous studies across different geographies [

3,

4].

In a temporal context, spatial configurations refer to the internal organization of a residential area, the directional relationships between spatial elements, and how these relationships shape user behavior [

5]. These configurations have continuously evolved throughout history in response to changing lifestyles, technological developments, and socioeconomic transformations. The configuration of space is a multilayered process shaped not only by aesthetic or functional preferences but also by social norms, cultural values, and daily life practices. In this context, the analysis of spatial configurations is critical for understanding how cultural and historical transformations are reflected in space. Here, environmental parameters such as topography and climate are acknowledged as potential shaping factors of spatial layouts; however, in this study, they are not treated as causal explanations on their own but rather as contextual elements that interact with socio-cultural dynamics.

The theory of space syntax used in this study, as developed by Hillier and Hanson [

6], provides a powerful analytical framework for analyzing the configuration of the built environment and revealing its connections to social relations. Space syntax is particularly effective in uncovering relational patterns underlying complex spatial organizations and explaining the interaction between space and society [

7,

8]. It allows understanding how housing typologies transform across contexts by revealing the social, cultural, and behavioral patterns behind spatial configurations [

9,

10]. This method yields successful results in analyzing both the evolution of traditional rural dwellings [

9,

10] and the relationship of contemporary housing designs to values such as social relations and privacy [

11,

12]. Space syntax analyses have been shown to be an effective tool in revealing how social and cultural values are represented in space [

13]. Therefore, comparative analysis of spatial configurations provides valuable insights not only in terms of formal but also socio-cultural and historical analyses. These analyses provide a holistic framework for understanding the spatial reflections of changing lifestyles over time and contribute to understanding the social function of space [

11,

13].

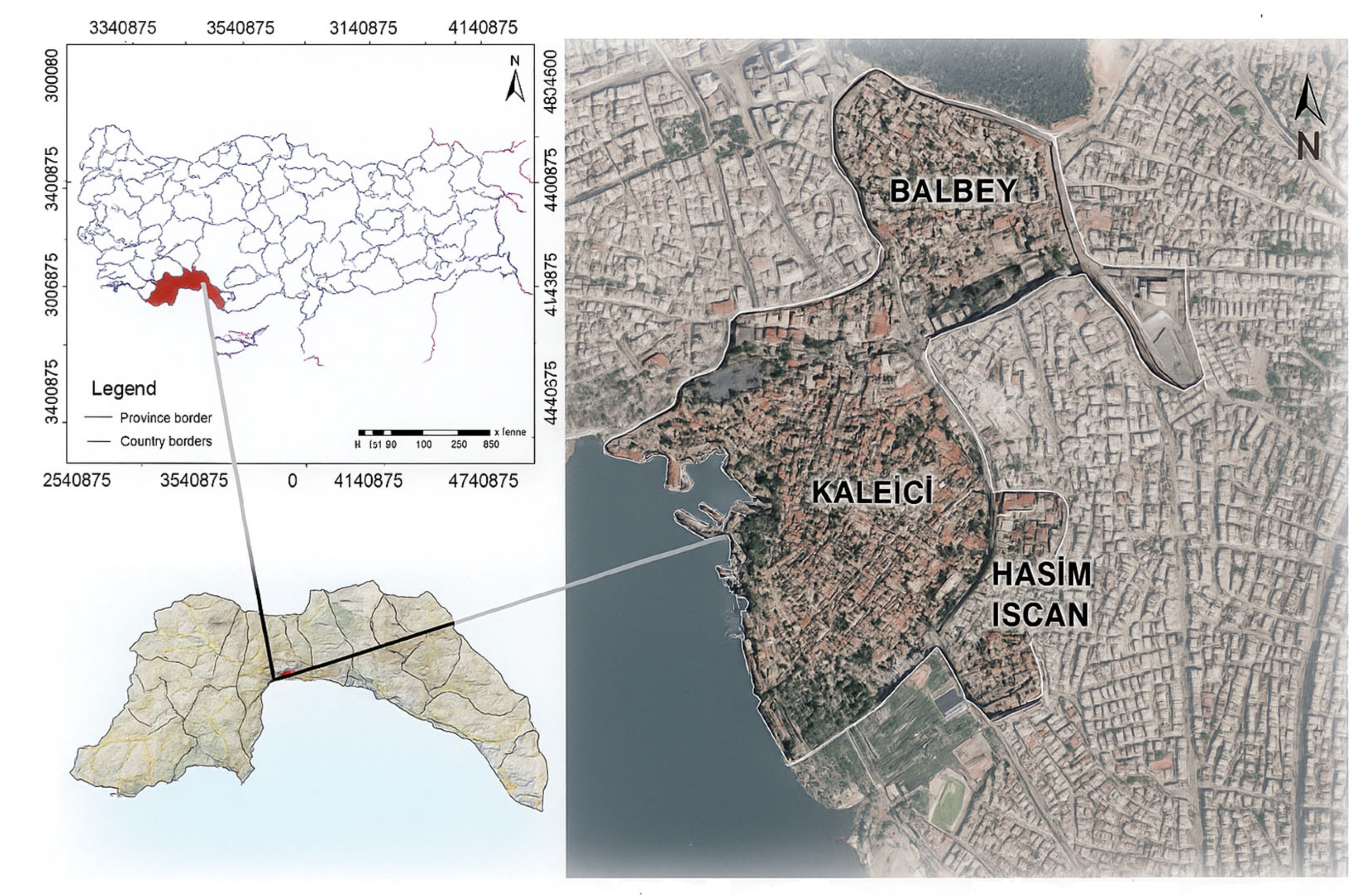

In this context, the study comparatively examines the morphological structure of traditional houses built in different time periods and cultural contexts in three neighborhoods of Antalya (Kaleiçi, Haşim İşcan, and Balbey). Antalya is a city located in southwestern Türkiye and distinguished by its rich historical heritage. The city’s traditional fabric is a significant element reflecting the historical, cultural, and geographical characteristics of the region. While Antalya’s Mediterranean climate and topographical conditions constitute a shared background for the case neighborhoods, the primary analytical focus of this study lies in how socio-cultural differentiation is reflected in spatial configurations. Environmental aspects are considered as secondary contextual variables rather than as direct explanatory factors, given the limits of available data. Antalya’s historical development has a multilayered history encompassing the Hellenistic, Roman, Byzantine, and Ottoman periods. The city developed within the city walls, and over time, the walls expanded, resulting in the emergence of new neighborhoods. Especially during the Ottoman period, new settlements such as the Balbey and Haşim İşcan neighborhoods emerged in front of the castle gates. While Kaleiçi represents the first formation of the organic texture of the city, the other two neighborhoods are settlements that developed later and were shaped by different socio-cultural groups.

These physically close regions developed in relation to each other throughout history, but over time they became isolated, and isolated urban areas were not integrated with the city. This makes it expected that the architectures of societies with different social and cultural characteristics would also differ. Therefore, this study aims to understand how cultural differentiation is reflected in the space by analyzing traditional houses in these three neighborhoods located in Antalya’s historic city center using the space syntax theory.

In studies on traditional Turkish houses in cities with multi-layered historical pasts like Antalya, analyses have largely revolved around typological and morphological classifications [

14,

15,

16,

17]. Foundational works such as those by Kuban [

2], Eldem [

18]. have emphasized plan typologies, façade features, and stylistic transformations, framing the “Turkish house” primarily within architectural history [

1,

2]. While this approach has provided valuable typological categorizations, it has often overlooked the spatial logic that underpins everyday life practices and socio-cultural dynamics.

In parallel, the development of space syntax methodology [

6] and its later applications [

19,

20] has allowed researchers to move beyond typology and investigate houses as socio-spatial systems. This method, by quantifying configurational properties such as connectivity, integration, and privacy, provides an analytical lens to study how spatial arrangements structure social interaction. Yet, despite its increasing use in both international and Turkish scholarship, Antalya houses—unlike the more frequently studied examples from Safranbolu, Kayseri, Yalova, Ankara, the Black Sea, or Mardin [

10,

21,

22,

23]—have not been examined in sufficient depth with this method.

This study addresses that geographical and methodological gap. By focusing specifically on Antalya, Kaleiçi, and its surrounding neighborhoods (Haşim İşcan and Balbey), it situates Antalya within the broader corpus of regional house studies, while at the same time highlighting its distinctive characteristics. Unlike the timber-heavy houses of the Black Sea or the courtyard-centered typologies of Mardin, Antalya houses evolved under a Mediterranean climate and a multi-layered socio-cultural setting. This resulted in hybrid spatial solutions where openness, climate adaptation, and communal practices intersect.

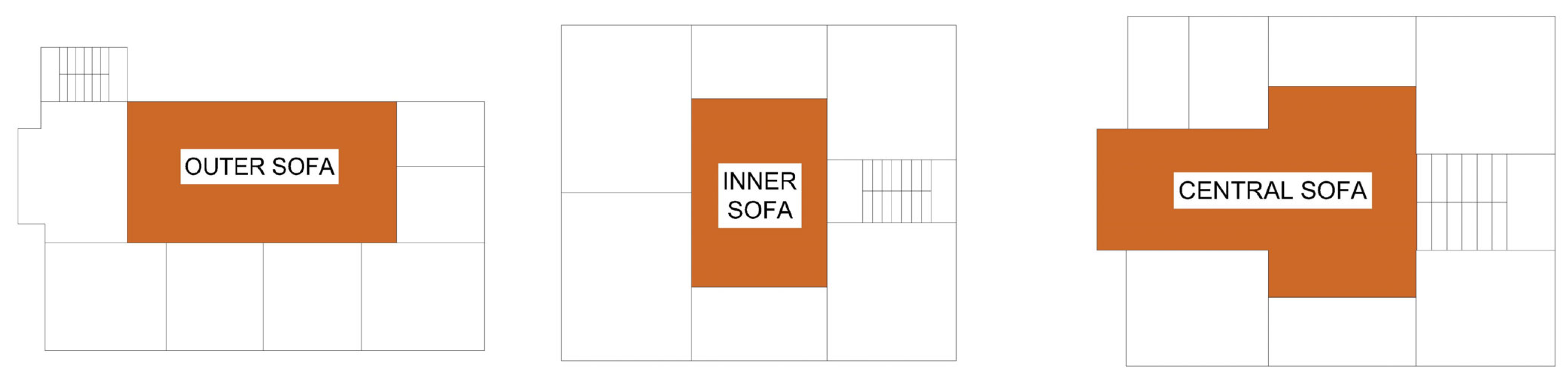

At the center of this investigation lies the sofa space, long recognized as a defining element of the Turkish house. Previous classifications distinguish between external, internal, and central sofas [

18], but beyond their typological status, Besli and Bideci (2024) and Karakuş and Çelik (2023) have underlined their socio-cultural significance as spaces mediating between family intimacy, guest reception, and neighborhood interaction [

23,

24]. Kuban (1995) even described the sofa as the “spatial backbone of the Turkish house,” emphasizing its role in organizing privacy and community life [

2]. The Westernization period of the 18th–19th centuries further complicated this picture, introducing representational qualities to the sofa and diversifying its functions.

This study builds on these debates by adopting a space syntax perspective, reinforced with access graphs, to explore how Antalya houses reflect both cultural continuity and transformation. Through comparative analysis of different neighborhoods—constructed under the same geographical and climatic conditions but by different socio-cultural communities—it demonstrates how spatial organization encodes evolving social dynamics. In particular, it shows that the sofa is not reducible to a single typological category but rather a dynamic socio-spatial element: at times a circulation space, at others a private family core, and in some cases, a representational setting for broader social life.

By situating Antalya houses within national and international scholarship while also foregrounding their regional distinctiveness, the study contributes to ongoing debates between continuity-focused and transformation-focused approaches. It thus offers both a theoretical contribution to the literature on traditional Turkish houses and a methodological demonstration of how configurational analysis can reveal the socio-cultural logic of domestic space.

1.1. Architectural Identity in Traditional Antalya Houses

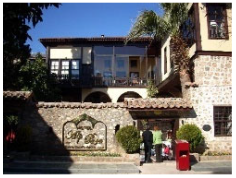

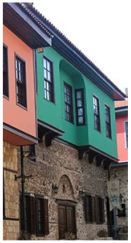

The traditional housing texture of Antalya, especially the structures concentrated in the historical city center known as Kaleiçi and developed in the Balbey and Haşim İşcan neighborhoods, reflect the characteristic features of Ottoman-era civil architecture. These structures provide important clues in terms of both architectural structure and aesthetic details. It is stated that the earliest examples of traditional houses in Antalya date back to the end of the 19th century and that the historical context of these houses can be read through their decorative elements [

25].

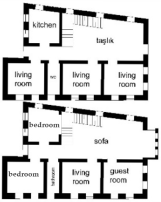

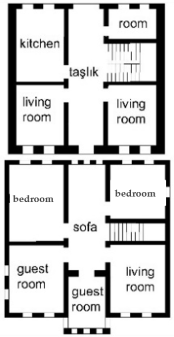

Spatial Organization and Typology

Traditional houses in Antalya generally have a two-story, courtyard and sofa (the section that connects rooms in a traditional Turkish house) layout. “While the lower floors of the houses are used as service areas, the upper floors are arranged as daily living and guest hosting areas. The main area is on the upper floor, as in traditional Turkish houses” [

25]. While the lower floors usually contain auxiliary functions such as the kitchen, ablution ward, and pantry, the upper floors contain the main room, bedrooms, and rooms opening to the sofa.

The Sofa as the Core of the Traditional House

The “sofa” in traditional Turkish houses is not only a circulation zone but also a central element of daily life and social interaction. Functionally, it connects the rooms and ensures ventilation and light—particularly in Antalya houses, where it is often arranged as open or semi-open to the exterior [

26] and serves as the spatial backbone of the dwelling. Beyond its functional role, however, the sofa is also the cultural and architectural core of the house. As Sözen [

27] emphasizes, it is the element that most distinctly characterizes the Turkish house, embodying the spatial logic of the dwelling together with the rooms. Typologically, sofas exhibit significant diversity. Bektaş [

28] and earlier scholars such as Eldem [

18] and Kuban [

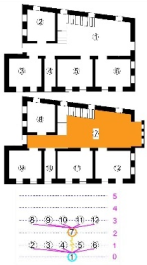

2] identify three primary types (

Figure 1): the outer sofa, attached to the façade and opening directly to the exterior; the inner sofa, more internally located with rooms organized around it; and the middle sofa, symmetrically positioned at the center of the plan, often serving as the spatial and social core. These variations are not merely architectural preferences but reflect family structures, privacy relations, and climatic adaptations, showing that the sofa is a dynamic and context-dependent spatial element rather than a uniform feature across traditional Turkish houses. When viewed in a cross-cultural perspective, the uniqueness of the sofa becomes more evident. Unlike the Western corridor, which emerged in the 17th century as a purely circulation-oriented space, the sofa simultaneously accommodates multiple activities such as sitting, dining, and hosting guests [

25]. Compared to the courtyard in traditional Arab or Iranian houses, which is open-air and external, the sofa is often semi-open or enclosed, situated on the upper floors, and functions as the interior social nucleus [

25]. Similarly, while the Japanese engawa resembles the sofa as a shared transitional band between the rooms and the garden, it is less inward-focused and does not serve as the central organizer of interior space. Thus, the sofa in the Turkish house is a culturally specific spatial type that transcends the role of corridor or circulation zone, integrates social and functional uses, and stands at the intersection of domestic life, cultural meaning, and architectural organization.

Gardens, Courtyards and “Taşlık” Space

One of the most distinctive features of Turkish-style houses is the entrance area called “Taşlık” (stone-paved entrance hall). This area usually opens to the garden and is surrounded by glass or guillotine windows. In addition, the latticed window located at the top of the entrance door allows privacy to be maintained by ensuring that people coming to the house can be seen. “Taşlık is the spatial equivalent of both daily life and social control” [

25].

Use of Materials and Adaptation to the Climate

Local stone and wood are the most preferred building materials in traditional Antalya houses. Houses rising with a wooden frame system on stone foundations are designed to be both earthquake resistant and suitable for the climate. “Due to the effect of the hot Mediterranean climate, elements such as shaded stone areas, high ceilings and inner courtyards that provide coolness were included” [

29]. These design elements also increase living comfort by creating air circulation in the interior.

Relation between Exterior and Street

The facades of Antalya houses facing the street are generally plain. The houses are lined up along narrow streets and closed to the street with courtyard walls. However, the bay windows on the upper floors establish a visual relationship with the street and at the same time provide the opportunity to observe the outside from the interior. “Bay windows are multifunctional elements that both protect privacy and provide shading against the climate” [

30].

1.2. Space Syntax: A Review at Studies on Traditional Houses

Space syntax is an analytical framework developed in the 1970s under the leadership of Bill Hillier and Julienne Hanson, with its theoretical foundations laid in

The Social Logic of Space [

6]. This method examines the mutual relationship between built space and social behavior, proposing that spatial configurations are not arbitrary but shaped by and shaping cultural, social, and functional patterns [

7,

31]. By employing graph theory, space syntax produces abstract models that represent the topological and configurational relationships between spatial elements, enabling a deeper understanding of how spatial arrangements influence social interaction, privacy, accessibility, and hierarchy [

32].

In recent years, the application of space syntax to traditional houses has gained prominence as a tool to explore cultural values, social norms, and daily life practices encoded in spatial organization [

33,

34]. Syntactic analysis based on convex maps and axial lines reveals key spatial characteristics such as permeability, integration, depth, and symmetry, which reflect socio-cultural priorities like hospitality, gender-based spatial segregation, or communal versus private use [

35,

36].

More recently, comparative studies of traditional houses in multi-ethnic or multi-period urban environments have emphasized the method’s potential in tracing spatial evolution and cultural continuity [

9,

10,

37]. These studies show how space syntax can uncover the embedded cultural logic of space, particularly in urban contexts with layered historical development such as Antalya. Furthermore, Manahasa et al. demonstrate that space syntax is not only useful for understanding historical housing patterns but also offers insight into contemporary residential design, especially in relation to social interaction and privacy gradients [

12].

Additionally, Hasa and Yunitsyna highlight that space syntax allows for quantitative and qualitative evaluation of how cultural transformations over time influence spatial morphology. Through integration analysis, visibility graphs, synergy and intelligibility analyses, it becomes possible to visualize how space mediates between social functions and architectural form. Importantly, the method has been successfully used to compare different regional house typologies within similar climatic and geographic contexts, revealing how distinct social structures manifest in spatial configuration [

13].

In this context, space syntax emerges as a powerful analytical tool, offering both rigorous computational models and interpretive frameworks for understanding traditional houses in their cultural and historical context. Its capacity to systematically analyze spatial structure makes it particularly suitable for studies aiming to reveal the multi-layered relationship between space, society, and culture, as in the case of Antalya’s traditional neighborhoods examined in this study.

1.3. Research Questions and Hypotheses

As part of the research, the relevant literature was reviewed, field observations and studies were conducted, and the spatial organization of nine traditional Antalya houses was analyzed. The article’s hypotheses (H) and research questions (QS) of the study are as follows:

H1: The spatial structure of traditional houses in Antalya reflects cultural and historical continuity.

H2: Spatial organization varies across neighborhoods and construction periods.

H3: The spatial patterns of traditional houses are spatial expressions of social lifestyles and cultural norms.

Notably, although topography and climate are mentioned as part of the research questions (see QS-1), their influence is treated cautiously and interpreted within the limits of configurational evidence.

QS-1: How is the spatial organization of traditional Turkish houses in Antalya’s historic neighborhoods shaped by topography, climate, and cultural factors?

QS-2: What is the level of spatial integration of the sofa area in traditional houses, and what variations does this area exhibit among neighborhoods?

QS-3: Are there common spatial patterns across neighborhoods developed in different historical periods, and what indicators of cultural continuity do these patterns offer?

2. Method and Measures

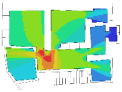

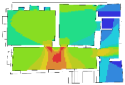

This study employed space syntax analysis to examine the spatial organization of 9 traditional houses located in the Kaleiçi, Haşim İşcan, and Balbey neighborhoods of Antalya. To analyze the selected houses using the space syntax method, dxf files were first prepared. The integration (Rn), synergy (R2), and intelligibility (R2) values of the houses, as well as the integration (Rn) and slope values of the hall, were calculated using DepthmapX 0.3 software. Integration analysis was used to determine the relative accessibility and social centrality of spaces within each house, while synergy and intelligibility values assessed the relationship between local and global spatial understanding. Additionally, J-Graph diagrams were created to visualize spatial hierarchy and depth from the main entrance, revealing patterns of privacy, circulation, and social use.

To complement these configuration analyses, Visibility Graph Analysis (VGA) was also used. VGA was calculated using a regular grid overlay, where floor plans were rasterized at a pixel resolution of 0.80 m, a commonly adopted value that balances computational efficiency and visual accuracy in historic domestic layouts. Boundary conditions were set to exclude inaccessible areas (such as walls and structural elements), ensuring that only navigable and visible spaces were incorporated into the visibility graph. Step depth calculations were tested; step depth was primarily used to capture visual fields in relation to spatial hierarchy. VGA outputs (visual connectivity and integration maps) were then compared, allowing for a cross-check of how visibility patterns align with cultural practices of privacy, hospitality, and gendered use of space in traditional Antalya houses.

These quantitative measures were interpreted in relation to cultural, climatic, and topographic contexts to understand how spatial configurations reflect socio-cultural values across different historical periods.

2.1. Syntactic Measures

The basic criteria used in space syntax analyses include integration, synergy, intelligibility, and J-Graph, which play a critical role in understanding how spatial structure supports social functions. Integration indicates how accessible a space is to other spaces in the system and is used to define areas where social interaction may be intense [

6]. High integration values indicate that spaces are more centralized and used more intensively. Synergy refers to how different functions come together spatially and the degree to which components in a layout system work together [

35]. Intelligibility measures how much the overall system structure can be understood from the local characteristics of a space; in other words, it shows how well users can estimate the overall layout by perceiving a small area [

38]. This is important in terms of wayfinding and user experience. J-Graph is a topological representation of connections between spaces and produces abstract relational maps of spatial structures [

32]. This graph allows analyzing the spatial organization of a building or settlement through nodes (spatial units) and edges (connections). When all these criteria are considered together, it is seen that the space syntax method provides a powerful framework for understanding how the spatial order is related to its social, cultural and functional components.

Integration

Integration analysis is one of the most basic and widely used criteria of the space syntax method and shows how accessible a spatial unit is compared to other units in the system [

6]. This criterion is used especially in determining areas with high social interaction potential and it is argued that more integrated spaces are used more frequently by people [

38]. Hillier emphasizes that areas with high integration values tend to be central points of social activities and pedestrian mobility. In this context, integration analyses conducted in traditional settlements show that areas such as streets and courtyards where public life is concentrated are also more spatially integrated structures [

39]. For example, Vrusho and Yunitsyna state that integration analyses conducted in traditional housing textures reveal that spaces that are culturally prioritized overlap with spatial centrality [

33]. In this respect, integration analysis is a powerful tool that reveals the spatial projection of social functioning at both the individual housing scale and the neighborhood level and is formulated with Equation (1).

M is the total number of areas (or nodes) in the analyzed system; D(n) is the average depth or topological distance of a given area n to all other areas; and Rn is the normalized integration value over all areas.

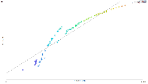

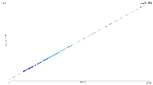

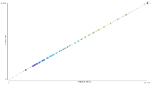

Synergy and Intelligibility

Another important analysis made in the study is the distribution graphs of intelligibility and synergy values. In the evaluations made on these two parameters, if the values are between 1 and 0.45, the settlement in question is considered to be highly understandable or effective at the local scale. If the values are between 0.45 and 0.2, the settlement is considered to be moderately understandable. If the values fall below 0.2, it is interpreted that the spatial system has low intelligibility and presents perceptual difficulties for users [

40,

41,

42,

43]. This analysis is used as an important indicator both in urban planning and in spatial evaluations of traditional settlements.

In order to evaluate intelligibility, the relationship between integration and connectivity was analyzed. This analysis aims to determine whether the local spatial order contributes to the perception of the entire spatial structure [

44]. In space syntax theory, intelligibility is defined as the capacity of a space to provide clues for the objective perception of urban spatial order [

45]. If the intelligibility of a spatial structure is high, this indicates that the general spatial pattern of the structure in question can be more easily noticed and deciphered by people.

Synergy is a correlation value that reveals the relationship between global integration and local integration [

6]. In this study, local integration was calculated using a radius of three steps (R3), a commonly used measure to capture neighborhood-scale spatial relations, and correlated with global integration (

Rn). This ratio shows the extent to which the direct connections of a line to its surroundings provide information about its importance in the system [

46]. The higher the correlation, the more local areas in the system are thought to be used as well-organized local components of the urban grid [

47]. Synergy is directly related to the spatial experience of users and reflects the structural harmony between local and global spatial arrangements. High synergy values indicate that the general structure of the area is perceived more easily at the local level and accessibility is strong [

48], while low synergy values indicate that the analyzed area is relatively isolated from the system, therefore has more privacy and circulation is limited.

In space syntax analysis, synergy and intelligibility are statistical measures aimed at understanding the integrity and intuitiveness levels of the spatial system. Both are based on correlation, and their formulas are given in Equations (2) and (3):

J-graph

J-Graph (Justified Graph) is a graph where all other spaces are drawn hierarchically according to their depth levels, starting from a specific root space (usually the entrance). Each node represents a space, and each edge represents a direct connection between spaces. It provides a simple yet effective way to illustrate how spaces are organized and how they are accessed from the entrance. In this study, the J-Graph analysis was conducted specifically to determine the depth level of the sofa space. Hierarchically revealing the depth at which the sofa space is positioned from the entrance is critical for understanding users’ wayfinding processes within the space and its accessibility structure. Thus, the J-Graph not only depicts the physical organization of the space but also reveals the place of focal points, such as the sofa, within the space hierarchy, providing information to guide wayfinding behaviors and design.

2.2. Case Study

Antalya is an important province in the south of Türkiye, in the west of the Mediterranean Region. It is located between 36°07′–37°29′ north latitude and 29°20′–32°35′ east longitude. Antalya, which has a coast to the Mediterranean in the south, is surrounded by Burdur and Isparta in the north, Konya in the east, and Muğla in the west (

Figure 2).

2.3. Case Selection

Previous studies on the spatial and environmental characteristics of the Antalya traditional house are usually based on only one or two cases. It is not uncommon to encounter up to 10 cases in studies of this nature [

29]. Although the number of cases required by different approaches and methods varies, previous studies emphasize that the number of traditional houses in Antalya is insufficient to develop a valid statistical sample. The main reasons for this limitation are the small number of structures that have survived to the present day without significant deterioration and the fact that most of the houses belong to private individuals and therefore have not been sufficiently made open to academic studies [

49].

In this study, the Antalya Metropolitan Municipality zoning archive was used in the case selection. The cases determined to be examined in this article had four important characteristics:

They have not changed with urban relations, modernization trends and natural events.

They are concrete examples of the time period in which they were built.

They carry the traditional traces of the region.

They have not undergone a serious transformation over time and have largely preserved their original features.

We focused only on the cases of houses with sofas in the Antalya Metropolitan Municipality archive. The primary reason for selecting traditional houses containing only sofa spaces is that the sofa space is a central element determining the spatial organization of the building in traditional Turkish house culture. The sofa functions as a nucleus that directs the arrangement of rooms, the flow of movement, and social interaction, providing comparative data suitable for space syntax analysis. Because the study’s aim is to reveal cultural continuity by analyzing the integration levels of sofa spaces across different periods and neighborhoods, the sample selection was made in line with this focus.

Furthermore, while different plan typologies exist in Antalya’s historic neighborhoods, houses with sofa spaces are both common in terms of typological representation and culturally defining architectural features. Therefore, limiting the sample to houses with sofa spaces was a deliberate choice to ensure an in-depth examination of the spatial patterns on which the study focuses.

This limitation undoubtedly limits the generalizability of the findings to a certain extent. However, the aim of the study is to demonstrate the cultural and morphological continuity of a specific spatial typology, rather than to make a universal generalization. Future studies could include comparative analyses of other housing types that do not include sofa spaces, allowing for a broader assessment of the cultural impact of different spatial organizations.

Therefore, the number of cases is 9. The cases date back to the end of the Ottoman period.

2.4. Case Examples

For the study, nine examples from the historical city center of Antalya, bearing the traces of traditional architecture, were selected (

Figure 2). Most of the nine housing examples selected from three different traditional neighborhoods (Kaleiçi, Balbey, and Haşim İşcan) (

Table 1) were rehabilitated, while the rest were partially or completely severely damaged. Some are still in use, and some are not. Due to the interventions made by the users over time, the original states of the buildings were determined before they were examined, and the analyses were carried out based on the original plans.

3. Findings

Table 2 shows the spatial configuration calculations of the houses based on the dxf plans provided in

Table 1.

Table 3 shows the integration (Rn), synergy (R

2), and intelligibility (R

2) values of the houses, as well as the integration (Rn) and elevation values of the hall.

Table 3 illustrates the relationship between the total depth of the house and the hall’s spatial degree.

The ground floors generally show higher average integration values. These values are particularly high in houses such as House 1 (12.634), House 5 (13.027) and House 6 (10.731). This indicates that the ground floor is more central, accessible and has a structure that facilitates wayfinding. The integration values on the first floors are generally lower. This situation can be associated with the fact that the first floor in traditional Turkish houses hosts more private areas. The highest maximum integration value (33.740) is on the first floor of House 6. This unusual situation may indicate the presence of a very integrated area (possibly a common or central hall) on the first floor.

The maximum integration values of the sofa areas provide information about how accessible and central they are within the house. The highest sofa integration value is in House 6 (33.740), followed by House 5 (26.122) and House 4 (25.093). Only House 2 and House 8 scored 3 in terms of sofa grade. This shows that the spatial integration of the sofa area is at a lower level in these two houses and is placed more peripherally. In general, sofa areas with high integration values function as the social core of the house. This confirms that the sofa is a central space in the traditional Turkish house.

Synergy values are very high in all houses (between 0.975 and 0.999). This shows that there is a strong correlation between integration and connectedness in the spatial system in general. This strong relationship suggests that the house plans are well organized as a whole and provide structures that support wayfinding.

The highest intelligibility values were observed in House 8 (0.920) on the ground floor and House 9 (0.940) on the first floor [

50,

51]. This shows that it is easier for users to perceive the space and find their way in these houses. Low intelligibility values are seen in examples such as House 4 (0.777 ground floor and 0.808 first floor). This may indicate that the spatial structure is difficult for the user to intuitively understand. In general, in houses where sofa integration is high, the relatively high intelligibility also shows that the sofa plays a role in increasing spatial intelligibility.

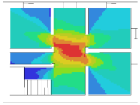

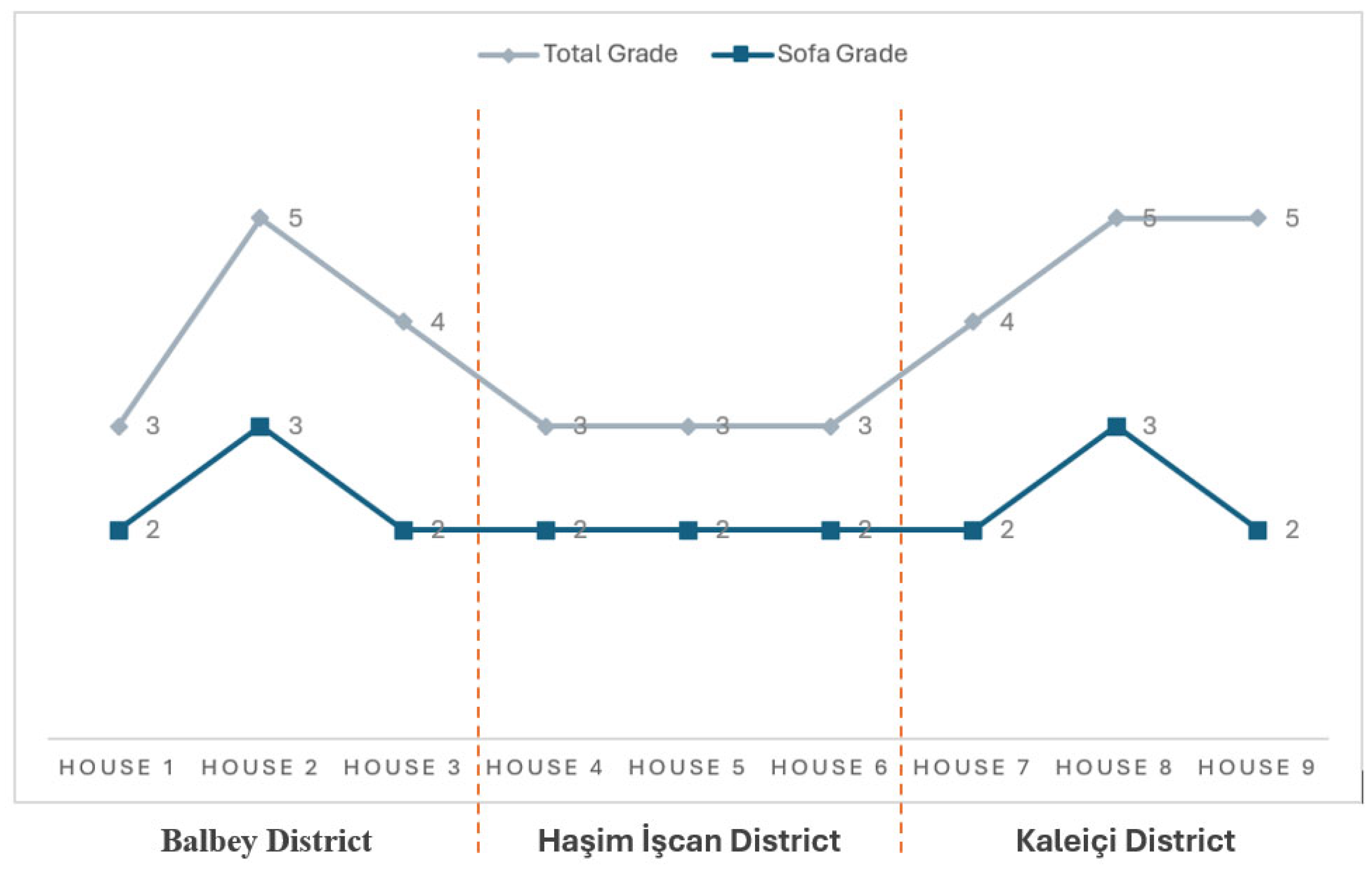

According to the findings in

Table 2,

Table 3, and

Figure 3, all spaces in the houses can be reached in a maximum of four or five steps. The first step is usually the entrance hall, or the stony area. The deepest spaces are usually storage, toilets and bathrooms. Access to these spaces is provided in at least three or four steps. The average ground floor integration (Rn) of all houses is 9.983, and the average on the first floor is 9.339 (

Table 3).

Integration (Rn) values are high on both the ground and first floors in House 5 and House 6, indicating that these houses offer more spatially integrated structures. The highest sofa integration was measured in House 6 (33.740) and the lowest in House 2 (5.001), which clearly reveals the level of the sofa as a social center. Synergy (R2) values are quite high in all houses (≥0.975), indicating strong structural integrity between the spaces. However, some differences are noticeable in terms of intelligibility; for example, while the low intelligibility value (0.777) in House 4 indicates that finding the way has become difficult, House 1 and House 9 indicate user-friendly organizations with high values (0.975 and 0.937). These findings reveal how the social functionality of the space, ease of finding the way and spatial integrity vary in house planning.

These findings should be interpreted not as definitive conclusions representing all neighborhoods, but rather as tendencies observed within the studied sample. They reveal how the social functionality of the space, ease of wayfinding and spatial integrity vary in house planning. The findings presented in

Figure 3 evaluate the spatial structure of traditional houses in three different historical neighborhoods of Antalya in terms of sofa integration and total integration degree. The fact that sofa grade values remain largely constant and are measured as 2 in most houses indicates that sofa space assumes a similar central role among houses. This situation suggests that the sofa is at the center of social life and wayfinding behavior in traditional houses.

On the other hand, total grade values vary significantly among houses. This difference reveals the structural diversity of houses in terms of spatial integrity and permeability. Especially among the houses (Houses 1–3) in Balbey Neighborhood, House 2 draws attention with both high total (5) and sofa (3) scores; this shows that the houses in the region have a more open, transitional, and accessible spatial order.

In contrast, houses in Haşim İşcan Neighborhood (Houses 4–6) are represented with lower integration values in total (total: 3, sofa: 2); This indicates more closed, fragmented, and limited spatial organizations. It is evaluated that these structures may limit visual control and make wayfinding behavior difficult.

In the houses in Kaleiçi Neighborhood (Houses 7–9), the total integration scores increase again (especially in House 8 and House 9, total: 5). This situation suggests that the spatial networks in these houses have a more permeable and integrated structure. However, the fact that the sofa scores remain at a moderate level (2–3) indicates that life in the interior is shaped by certain boundaries and functional arrangements.

As a result, the findings reveal that the integration role of the sofa space between houses generally remains constant, but the total integration values vary according to the neighborhood and the house. This situation shows that the spatial structure is shaped not only by physical but also by socio-cultural practices. In this framework, environmental factors such as climate and topography are considered as contextual elements interacting with socio-cultural practices rather than independent causal determinants. This positioning underlines their secondary role in the interpretation of spatial organization.

4. Discussion

The space syntax analysis of traditional houses in the Balbey, Haşim İşcan, and Kaleiçi neighborhoods of Antalya reveals not only shared spatial patterns but also significant variability, influenced by cultural, functional, and topographical factors. These findings, when critically compared to other recent studies using space syntax in traditional housing analysis, highlight both universal features of traditional house design and context-specific adaptations.

Ground Floor Integration and Social Function

The observation that ground floors generally have higher integration values (e.g., House 1: 12.634 and House 5: 13.027) aligns with findings from Ayyıldız and Durak [

10] in Yalova’s rural houses, where ground-level spaces also served as hubs for social interaction and daily activity. This suggests a common design logic in traditional Turkish housing, where public or semi-public functions are located on more accessible ground floors, while private functions are elevated to upper floors with lower integration values. The high maximum integration on the first floor of House 6 (33.740), however, deviates from this trend and suggests localized variations, possibly due to the presence of a multi-functional hall or structurally prominent sofa on the upper level. These differences are related not only to spatial arrangements but also to the reflection of family structure and daily life practices on the space. Rapoport [

3] and Lawrence [

4] emphasized the determinants of social roles and daily life cycles in housing planning. In the Antalya example, the intensity of social interaction on the ground floor can be interpreted as a reflection of family members and neighborly relationships on the space.

Sofa as Spatial and Social Core

Consistent with studies in Düzce village houses [

9], the sofa in Antalya houses generally functions as the spatial and social core, exhibiting high integration (e.g., House 6: 33.740). Sofa spaces act simultaneously as circulation nodes and centers of social life. Yet, variation exists: in Houses 2 and 8, sofas displayed lower integration and peripheral positioning (Grade 3), suggesting more limited social use. This parallels Yunitsyna’s [

11] findings in Tirana, where communal areas differ in centrality depending on density and cultural practice.

On a broader scale, Ergün, Kutlu, and Kılınç [

14] found that integration in Antakya houses developed around the courtyard, while in Antalya the courtyard is secondary and the sofa becomes the dominant spatial node. This highlights the “sofa-centered” genetic code of Antalya houses. Karakuş & Çelik [

52] similarly underline the persistence of cultural-genetic codes, showing how traditional Anatolian houses in Güdül preserve spatial hierarchies despite modernization. Kuban [

2] also defines the sofa as the “spatial backbone of the Turkish home,” organizing privacy gradation and social relations. Atak & Çağdaş [

53] further note that in Kayseri houses, sofas embodied socio-cultural meanings linked to religious diversity, reinforcing their symbolic as well as functional role. Thus, sofa diversity in Antalya is both a typological variation and a cultural reflection of family norms, neighborly interactions, and broader socio-religious values.

Intelligibility and Wayfinding

High intelligibility values (House 8: 0.920; House 9: 0.940) suggest that Antalya houses generally support intuitive wayfinding. This is consistent with Yunitsyna [

11], who stresses the importance of visibility and clarity in user-friendly environments. In contrast, House 4’s low intelligibility (0.777) indicates a more compartmentalized layout, limiting visual access and making orientation less straightforward. Manahasa et al. [

12] argue that such reductions in intelligibility are often linked to stronger privacy demands, especially in inward-oriented designs. Lawrence [

4] argues that “ease of orientation” is linked not only to visual clarity but also to culturally constructed perceptions of privacy. Low intelligibility values in Antalya homes also correspond to examples where family boundaries are stronger and daily life is lived inward.

Neighborhood-Based Variations in Integration and Permeability

A clear neighborhood-based differentiation is evident. Houses in Balbey exhibit higher permeability and total integration, similar to socially open rural environments described by Ayyıldız and Durak [

10]. In contrast, Haşim İşcan houses are more closed and hierarchical, mirroring the privacy-driven layouts found in Düzce and some Tirana housing complexes [

12]. Kaleiçi houses present intermediate structures, with functionally bounded but spatially permeable layouts, indicative of hybrid cultural and urban influences. These neighborhood differences can be explained not only by morphology but also by the patterns of neighborly relations and families’ social interaction habits. As Rapoport [

3] points out, the spatial configuration of housing reflects the social norms and lifestyles of communities. While the high permeability in Balbey suggests more outgoing neighborhood practices, the closed layouts in Haşim İşcan emphasize expectations of privacy.

Cultural Norms and Spatial Logic

The consistent centrality of the sofa across all neighborhoods, despite variations in integration, reflects its cultural importance in Ottoman-Turkish domestic tradition. Differences in integration and intelligibility, however, illustrate how social norms, privacy expectations, and functional needs shape spatial logic. Hasa & Yunitsyna [

13] stress that traditional housing structures embody cultural values through their spatial organization, while Kuban [

2] highlights that housing is a spatial reflection of daily practices and social norms. At the international scale, Molaei, Safari & Asadi Malekjahan [

27] show that in Lahijan’s courtyard houses, integration is organized around the yard rather than sofa-like nodes. Similarly, Choudhary & Adane [

28] demonstrate that in Central India, social interaction is structured around urban cores and semi-public courtyards, contrasting with Antalya’s inward sofa-centered organization. These comparisons highlight that Antalya houses encode socio-cultural values spatially in ways that are distinct from both regional and international examples.

Contemporary Housing Typologies and Social Implications

The findings of this study can be further contextualized by considering contemporary housing typologies in major Turkish cities. Although a detailed sociological analysis is beyond the scope of this research, previous studies examining the transition from traditional houses to apartment living provide critical insights into the spatial and social transformations involved. Tekeli [

52] argue that the shift to apartment housing has significantly altered patterns of neighborly interaction and weakened intergenerational cohabitation, thereby reducing informal social control and everyday solidarity within communities. Çetin and Beyhan [

31] further emphasize that apartment living reconfigures privacy gradients, introducing new definitions of personal and shared spaces and reshaping family dynamics. These observations reinforce the argument that the sofa-centered configuration of traditional Antalya houses represents not merely a spatial solution but also a socio-cultural code that structured domestic life. The erosion of such spatial codes in modern apartment typologies may have far-reaching implications for social cohesion, underscoring the need for further research on how contemporary housing design can sustain cultural continuity and familial interaction.

Synthesis and Implications

When compared to contemporary housing analyses [

11] and other traditional housing typologies [

9,

10], Antalya’s houses reveal both shared traits and unique adaptations. Rural Anatolian houses integrate production and living on the same floor [

9,

10], while Antalya houses separate them vertically. In Trabzon and Bitlis, sofa-like areas serve circulation needs [

15,

16]), but in Antalya the sofa emerges as the social and spatial core. Internationally, sofa-like spatial codes are absent: Albanian and Tirana houses are shaped by privacy–publicity tensions [

11,

13], Iranian courtyard houses prioritize the yard [

51], and Indian vernacular settlements centralize semi-public courtyards [

53]. It is emphasized that the transitional yet central role of the sofa in Ottoman residential architecture has no direct counterpart in global residential traditions [

52].

Overall, Antalya houses display strong synergy values (≥0.975), reflecting robust spatial integrity, while variations in intelligibility highlight localized cultural and functional imperatives. These findings confirm that space syntax is a powerful tool not only for analyzing efficiency and wayfinding but also for uncovering the cultural narratives embedded in spatial organization. Ultimately, Antalya’s sofa-centered configuration illustrates how family structures, daily life, and neighborhood relations are spatially encoded, positioning these houses as both culturally unique and analytically significant within the discourse on vernacular architecture.

Answering Hypotheses and Research Questions

The analyses revealed that the spatial structures of these houses are shaped by both natural environmental conditions (topography and climate) and social and cultural norms. The high integration values of ground floors indicate that social life occurs primarily on these floors, facilitating accessibility and wayfinding.

H1 Supported: The spatial structure of traditional houses in Antalya reflects cultural and historical continuity.

The sofa area, as the social and spatial center of houses, stands out with its high integration values. However, there are differences in the spatial location and integration level of this area among neighborhoods. While the sofa area is generally more central and highly integrated in houses in the Balbey and Haşim İşcan neighborhoods, the sofa integration in houses in Kaleiçi is moderate, and spatial permeability is shaped by specific functional boundaries. These differences reflect spatial use practices that emerged based on the neighborhoods’ historical development processes and social structures.

H2 Supported: Spatial organization varies across neighborhoods and construction periods.

While common spatial patterns exist across neighborhoods with different historical layers, local adaptations and differentiations have also been observed at the neighborhood level. The fact that the sofa area is the social and spatial center in all neighborhoods is a significant indicator of cultural continuity. Furthermore, the spatial arrangements developed by neighborhoods in line with social norms, privacy expectations, and functional needs reveal different interpretations and applications of these common patterns. The open and permeable structure of Balbey and the closed and hierarchical planning of Haşim İşcan are particularly illustrative examples of this diversity.

H3 Supported: The spatial patterns of traditional houses are spatial expressions of social lifestyles and cultural norms.

5. Conclusions

This study examined the spatial structure of traditional houses in three historical neighborhoods of Antalya (Kaleiçi, Haşim İşcan, and Balbey) using the space syntax method to reveal their morphological transformations. The analysis demonstrates that the sofa, and to a lesser extent, the courtyard, function as the social core of Antalya houses, exhibiting high integration values and fundamentally shaping the internal organization of the dwellings. A clear vertical separation between ground-floor service areas and upper-floor living spaces was identified, reflecting both climatic requirements such as shade and ventilation characteristic of the Mediterranean context—and social considerations, including privacy.

The findings highlight a distinctive “sofa-centered” spatial logic that sets Antalya houses apart from many other vernacular housing traditions. Unlike rural Anatolian houses, where production and living functions are typically integrated, Antalya houses maintain a strong vertical stratification of functions. Similarly, while in other regional traditions such as in Antakya or Trabzon courtyards and topographic/climatic conditions dominate spatial organization, in Antalya houses the sofa emerges as the principal node of social interaction and spatial integration.

Comparative analysis further emphasizes the originality of Antalya houses. In vernacular examples from Albania, Iran, and India, sofa-like spaces are absent or occupy a secondary role, with spatial integration instead organized around courtyards or transitional zones. By contrast, Antalya houses preserve the sofa as the defining element of spatial hierarchy, in line with broader Ottoman-Turkish domestic traditions.

In conclusion, the uniqueness of Antalya houses lies in their hybrid morphology, which combines climate-responsive design with culturally embedded spatial codes. The sofa functions not only as a circulation zone but also as the social backbone of the dwelling, representing a culturally specific yet analytically significant model of spatial organization. These findings enhance the understanding of Ottoman-Turkish housing traditions and contribute to the broader discourse on vernacular architecture by demonstrating how cultural identity and environmental adaptation are intertwined in spatial form.

In this context, the “genetic codes” of Antalya houses (

Table 4) can be summarized comparatively as follows:

The sofa’s centrality (not just circulation, but its role as a social core);

The vertical ground-floor separation (service/living stratification);

The secondary, supporting role of the courtyard;

The simultaneous determination of climatic adaptation and cultural continuity.

Table 4.

Genetic codes of traditional Antalya houses and the literature comparison.

Table 4.

Genetic codes of traditional Antalya houses and the literature comparison.

| Source | Spatial

Organization | Sofa/Courtyard Roles | Cultural–Climatic Determinants | Unique Genetic Code |

|---|

| Gökçen & Özbayraktar [9]; Ayyıldız & Durak [10] | Integrated production–life balance in

rural houses on a single floor | Courtyard and

service areas play a central role | Agricultural production, climatic adaptation, single-floor

living | Service–life integration, horizontal organization |

| Karakuş & Çelik [24] | Traditional Güdül houses | Courtyard and transitional areas | Local climatic adaptation, social practices | Spatial integration of service and living areas |

| Molaei, Safari & Asadi Malekjahan [50] | Yard-centered residential plans in Sharbafan, Lahijan | Courtyard primary, interior spaces secondary | Local climate, topography | Yard-centered integration |

| Ergün, Kutlu & Kılınç [14] | Spatial integration

developing around the courtyard in Antakya houses | Courtyard-

centered, sofa

secondary | Climate (shade, coolness), communal living focused on

courtyard. | Courtyard-centered integration |

| Hasa & Yunitsyna [13] Yunitsyna [11] | Modern apartment structures in Tirana and Albania shaped along the privacy–public axis. | No sofa-like spaces; influenced by modern apartment design | Modernization, transformation of cultural values | Privacy–public

balance |

| Choudhary & Adane [40] | Urban cores in central India | Courtyards as spatial hubs | Historical urban morphology | Centralized spatial configuration |

| Atak ve Çağdaş [53] | Traditional Kayseri houses | Sofa-like spaces for circulation | Climate- and topography-driven spatial arrangement | Topography-oriented layout |

| Şen & Baran [15]; Dursun & Sağlamer [16] | Spatial arrangement in Bitlis and Trabzon

shaped by topography and climate | Sofa-like spaces mostly used for circulation | Cold climate, sloped terrain conditions | Topography- and climate-oriented

layout |

Kuban [2] | Turkish Hayat houses | Courtyard-centered, sofa secondary | Ottoman-Turkish housing tradition, social codes | Courtyard-centric social-spatial code |

| This Study (Antalya Houses) | Ground floor (service)—upper floor (living) separation and vertical organization | Sofa space is most integrated and social; courtyard is secondary | Mediterranean climate (airflow, shade), Ottoman-Turkish house tradition (privacy) | Sofa-centeredness, vertical layering, cultural–climatic hybrid

morphology |

This study offers new, previously unseen, systematic findings regarding the spatial organization of Antalya houses. Spaces such as the sofa and courtyard are not only physically central but also function as social core areas where family interaction, hosting guests, and daily life are concentrated. This demonstrates that traditional plans are shaped by cultural norms and understandings of privacy. The differences in integration between ground and upper floor spaces reveal a distinct functional separation of service and living spaces, which directly influences social behavior within the family. Furthermore, the topography and climate conditions surrounding the houses necessitated the organization of spaces according to the needs for light, air circulation, and privacy; even some highly accessible spaces assumed different functions within the context of social and intimate use. While the spatial configuration varied according to the topography, the location of the sofa was more strongly influenced by the climate. These findings transform spatial analyses into social and cultural knowledge by revealing unique functional and social patterns shaped by climate, topography, privacy, and cultural norms behind the architectural layout of traditional Antalya houses.

Additionally, unlike other examples in both the national and international literature, Antalya houses transform the sofa into a socio-cultural genetic code, making this study both innovative and a valuable contribution to the literature on Mediterranean vernacular architecture.

6. Limitations

While this study presents significant findings regarding the spatial organization of traditional houses located in the historic Balbey, Haşim İşcan, and Kaleiçi neighborhoods of Antalya, it does have some limitations:

Small Sample Size

Traditional house plans are based on survey projects obtained from municipal archives. However, copyrights and usage permits on these projects limit the number of plans the researcher could access. Archive access is limited and controlled, particularly because the projects of historical buildings are generally under the supervision of conservation boards or the relevant municipalities. This prevented the creation of a larger sample and allowed for the analysis of only nine houses in total. In this context, the findings were limited to the structures examined, creating limitations in their general validity in representing all other traditional houses in Antalya. In the future, more comprehensive archive access or increasing the sample size through different data collection methods would contribute to stronger and more generalizable results in spatial analyses.

Dependence on Reconstructed Plans

The spatial data used in the study is based on digital models redrawn from survey plans of existing buildings. This carries the risk of not fully identifying changes and user interventions that have occurred over time in the original plans. In particular, the historical authenticity of some plans may be limited.

Possible Measurement and Interpretation Errors

The accuracy of the plans used in space syntax analyses directly impacts the accuracy of the calculated integration, permeability, and intelligibility values. Therefore, even small errors or incorrect limitations in measurement may slightly affect the interpretation of the results.

Limited Generalizability Beyond Antalya

The findings are meaningful within the context of the historical, cultural, and climatic conditions specific to Antalya. Therefore, the direct applicability of the results to traditional housing typologies in different geographies is limited. Spatial organization may differ, particularly in regions with different topography, social norms, and urbanization dynamics.

Historical Change Analysis

The study does not incorporate diachronic analyses of transformations that traditional houses in Antalya may have undergone over centuries. Considering temporal changes could provide deeper insights into spatial continuity, adaptation, and the resilience of housing typologies.

Socio-Anthropological and Psychosocial Dimensions

The research primarily focuses on spatial and configurational characteristics, while overlooking socio-anthropological aspects such as family structures, gendered use of space, and neighborhood interactions. Similarly, psychosocial dimensions—such as spatial perception, sense of belonging, and everyday practices—remain outside the scope of the study. Integrating these dimensions could enrich interpretations and produce a more holistic understanding of traditional housing.

J-Graph

J-Graph