Cognition–Paradigm Misalignment in Heritage Conservation: Applying a Correspondence Framework to Traditional Chinese Villages

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Foundations for Constructing the Correspondence Framework

2.1. Theoretical Basis

2.2. Methods and Data Sources

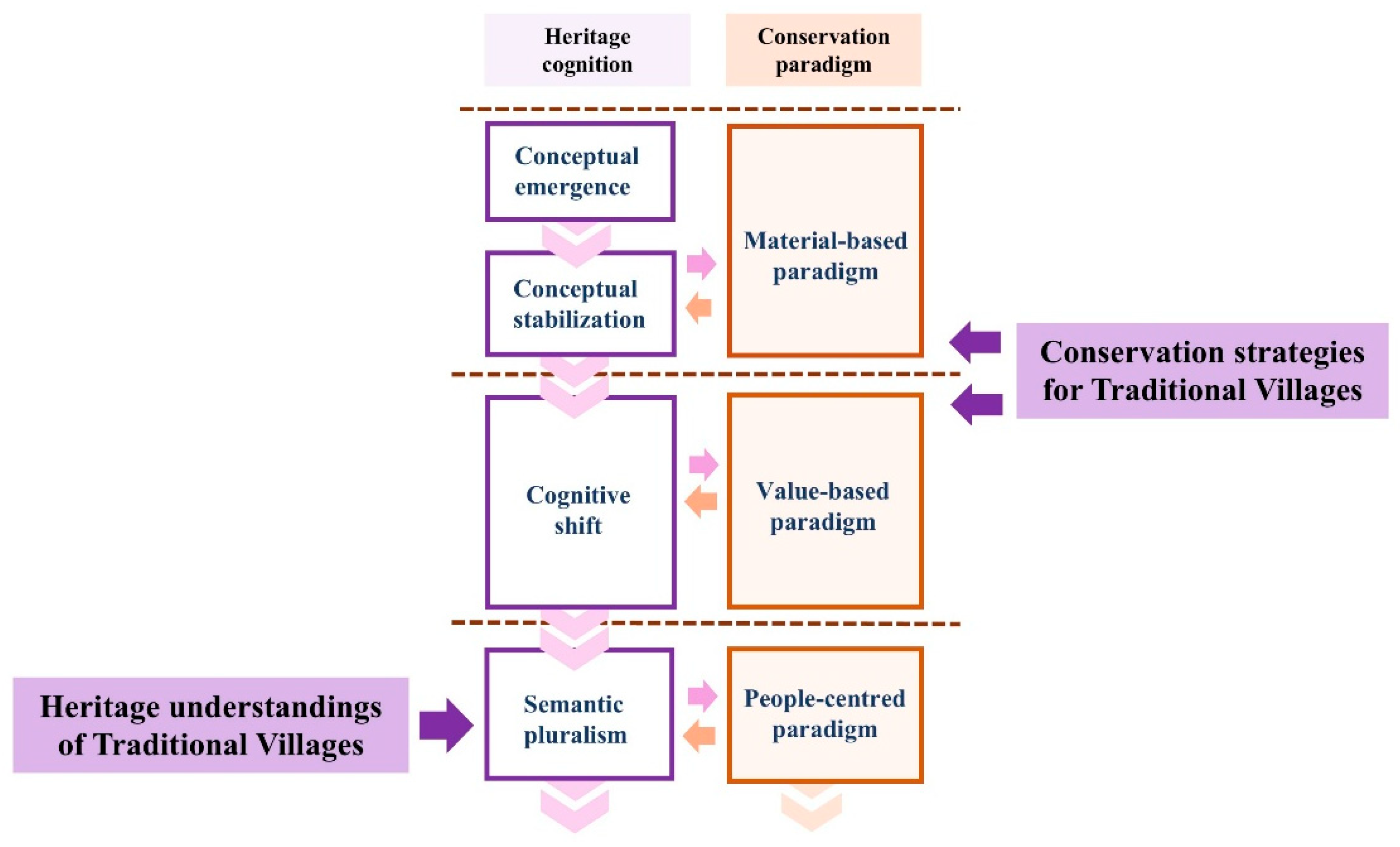

3. Periodizing Heritage Cognition and Conservation Paradigms

3.1. Semantic Evolution and Periodization of Cultural Heritage

3.1.1. Conceptual Emergence and Stabilization: Terminological Formation and Material Orientation

- Materialization: cultural heritage was framed predominantly in terms of built forms and physical artefacts.

- Objectification of value: cultural heritage value was considered inherent to the object, assessed through historical, scientific and artistic merit.

- Expert authority: legitimacy in heritage recognition was reserved for professionals.

3.1.2. Cognitive Shift: Value Pluralization and Decentralized Subjecthood

- Diversification of heritage objects: beyond physical sites, cultural heritage came to include landscapes, practices, skills, and community-based expressions.

- Expansion of value types: symbolic, ritualistic, and social values were brought into the discourse alongside traditional historical and esthetic ones.

- Pluralization of cognitive agents: recognizing the roles of communities, NGOs, networks, and individuals beyond experts.

3.1.3. Semantic Pluralism: Openness and Negotiability on Heritage Meaning

- Dynamic and non-material forms of heritage: process-oriented and symbolic phenomena are increasingly recognized

- Relativization of value standards: moving away from universal benchmarks to contextual interpretations.

- Functional relevance: being valued for its contributions to social resilience, cultural identity, and sustainable futures

- Decentralization of authority: local communities, grassroots actors, and non-state stakeholders began to assert legitimacy in heritage-making.

- Open-ended definition: heritage is no longer ‘discovered’ but co-constructed and continuously renegotiated.

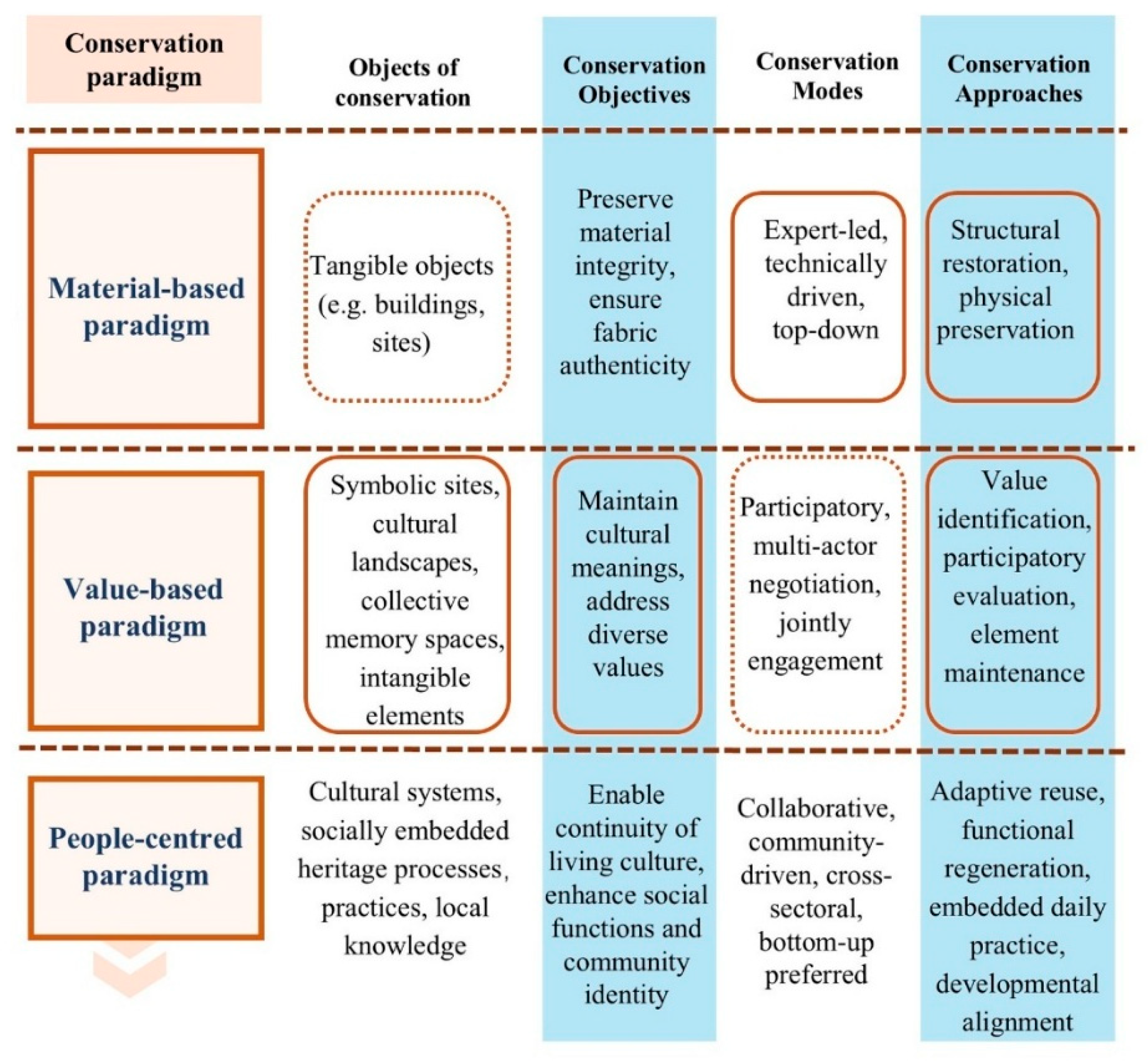

3.2. Conservation Paradigm Shifts and Their Characteristics

3.2.1. Material-Based Paradigm: Authenticity and Restoration Logic

- Primacy of authenticity: focused on preserving and replicating original fabric and form.

- Object-based conception: heritage understood as static material evidence.

- Expert dominance: professionalized, top–down decision making.

- Technical restoration focus: methods rooted in architectural repair and accuracy.

3.2.2. Value-Based Paradigm: Pluralism and Subjective Valuation Logic

- Pluralistic value orientation recognizes diverse cultural values beyond historical or esthetic significance, contextualized within specific socio-cultural settings.

- Expanded conservation scope includes intangible elements and integrated expressions such as landscapes, community practices, and local knowledge.

- Participatory governance encourages inclusive decision making through collaboration among communities, professionals, and institutions.

- Value-responsive strategies tailor conservation methods to the specific values and types of heritage, balancing physical preservation with cultural transmission.

3.2.3. People-Centred Paradigm: Livingness and Social Function Logic

- Contemporary relevance and continuity: heritage is valued as a living process, integrated into everyday life and capable of renewal.

- Holistic cultural ecosystems: conservation focuses on interconnected practices, memories, knowledge, and place-based identity, beyond material objects.

- Community-led governance: emphasizes inclusive, bottom-up decision making involving communities, professionals, and institutions.

- Adaptive, function-driven strategies: prioritizes revitalization, adaptive reuse, and local development.

4. Constructing the Correspondence Framework

4.1. The Correspondence Framework and Coupling Relationships

- Full alignment: occurs when a phase of heritage cognition closely aligns with a corresponding conservation paradigm, reflecting strong coherence between conceptual understanding and practical methodology.

- Delayed coupling: arises when cognitive advances outpace methodological practice, revealing a transitional tension between emerging conceptual clarity and the inertia of established conservation approaches.

- Cognitive–paradigmatic misalignment: emerges when heritage cognition reaches more advanced stages (e.g., those informed by cultural ecology or processual thinking), while conservation practice remains anchored in material-based paradigms. This misalignment leads to significant conceptual and practical inconsistencies.

4.2. Analytical Dimensions and Identification Criteria

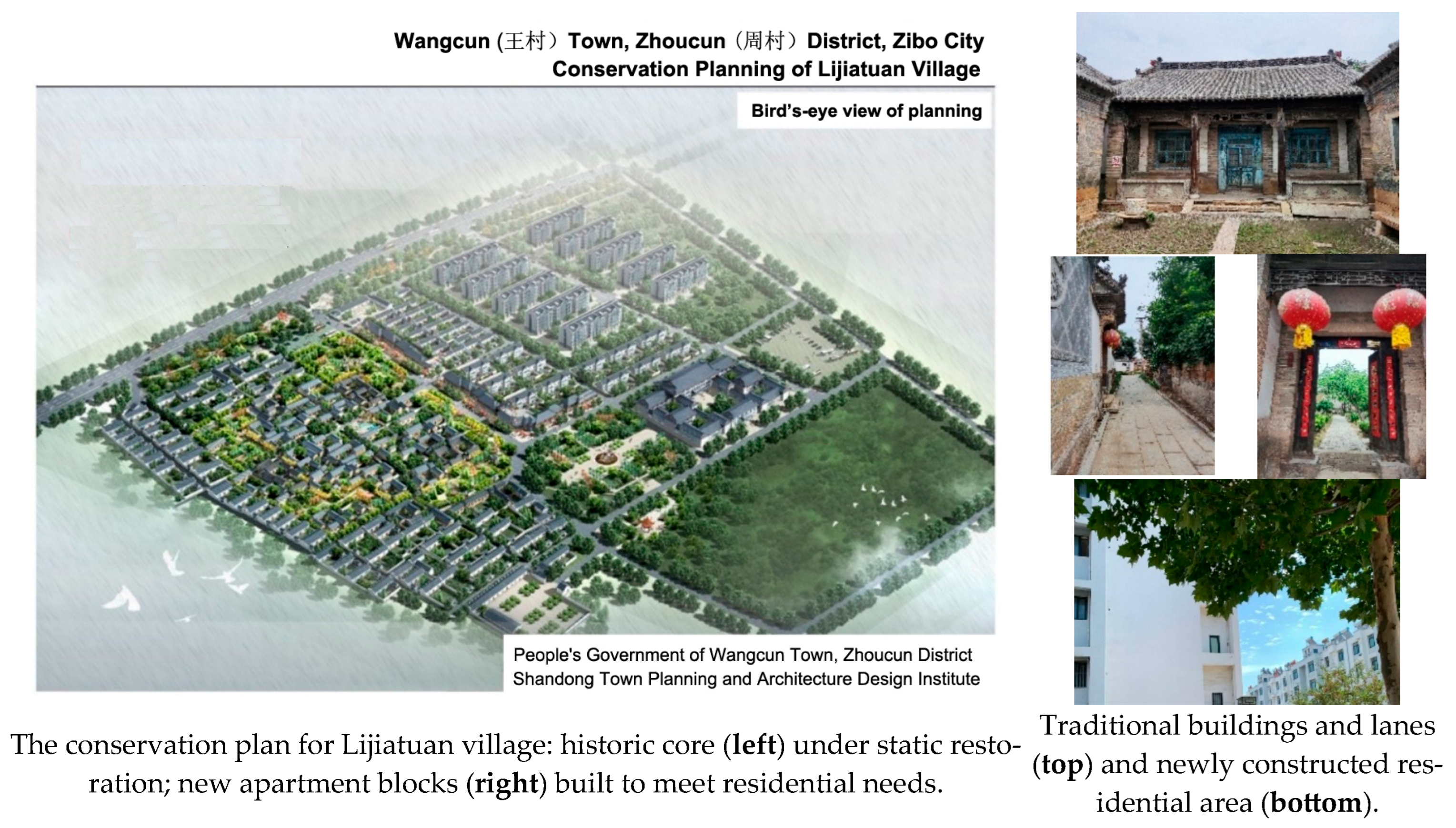

5. Applying the Correspondence Framework to Traditional Chinese Villages

5.1. Classifying the Heritage Cognition Phase in Traditional Chinese Villages

5.1.1. Heritage Value, Heritage Nature and Heritage Attributes

5.1.2. Heritage Object and Cognitive Perspective

5.1.3. Actor Structure and Synthesis

5.2. Identifying the Conservation Paradigm for Traditional Chinese Villages

5.2.1. Objects of Conservation: Fragmented Recognition Under a Dualistic Framework

5.2.2. Conservation Objectives: Selective Application and Functional Displacement

5.2.3. Conservation Approaches: Tangible Bias and Technocratic Implementation

5.2.4. A Top–Down Conservation Mode and Synthesis

5.3. Mapping the Cognitive–Paradigmatic Misalignment

5.4. Enhancing Conservation Strategies for Traditional Chinese Villages

- (1)

- Developing a recognition framework grounded in cultural vitality

- (2)

- Reframing conservation objectives from element-focused to process-oriented

- (3)

- Restructuring governance to empower local communities

- (4)

- Fostering interdisciplinary approaches and context-responsive innovation

6. Conclusion and Research Outlook

6.1. Summary of Findings

6.2. Theoretical Contributions and Practical Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MOHURD | The Ministry of Housing and Urban–Rural Development |

| ICH | Intangible Cultural Heritage |

| AHD | Authorized Heritage Discourse |

| ISAITV | the Index System for Assessment and Identification of Traditional Villages (Provisional) (Document No. 125) |

| BRCDPTV | the Basic Requirements for the Conservation and Development Planning of Traditional Villages (Provisional) |

Appendix A. Comparison Between Heritage Resources of Traditional Chinese Villages for the Fifth/Sixth Round Designation and Requested Conservation Measures in Official Provisions

| Heritage Elements for the Identification of Traditional Villages | Requirements and Measures for the Conservation Planning of Traditional Villages | ||

| Component | Details | Prescribed Degree | Concrete Methods |

| Village profile | Historical context, location, population size, basic situation of the village, lists of villages selected | —— | —— |

| History of village migration, legends and stories | —— | —— | |

| Natural or cultural surroundings | Natural environment, scenic spots, cultural relics and monuments | Specific and detailed | Designation of villages and areas of visual and cultural significance as a whole, and proposed landscape and ecological restoration measures, as well as rectification methods |

| Related legends and stories | —— | —— | |

| Layout patterns | Village pattern, basis and background of village site selection, village landscape | Specific and detailed | Designation of villages to be preserved as a whole, conservation of traditional form of villages, public spaces, and landscape view corridors, and proposed remedial measures Establishment of corresponding conservation management provisions for different scopes of conservation requirements |

| Concept of village buildings (historical inheritance) | —— | —— | |

| Traditional buildings | Registration of traditional building details, ownership of important buildings, general situation and drawings of buildings | Specific and detailed | Preservation of traditional buildings (structures) and proposing classification of traditional buildings (structures) and corresponding conservation measures with reference to Requirements for the Chinese Famous Historic and Cultural Villages |

| Stories in buildings | |||

| Historical environment elements | Registration of information on built structures, general situation and drawings of buildings | ||

| (None for stories in buildings) | |||

| ICH items | Registration information on specific ICH items (including rank of directories, inheritors, intangible heritage categories, degree of dependency with the village, number of participants) | Simple | Requirements for protecting inheritors of ICH |

| Simple | Requirements for protecting places, cultural routes, physical objects and related raw materials | ||

| Related folklore | Festivals, rituals, weddings, funerals, other artistic or sporting events | —— | —— |

| Daily life patterns | Specialty products, commercial bazaars, clothing and apparel, local foods | —— | —— |

| village records and genealogy | Village records, genealogy, township rules and regulations | —— | —— |

| —— | —— | —— | Improvement of living conditions, proposal of guiding measures improvement of road traffic without changing the spatial scale and style of the streets, proposing planning; enhancement of human environment, proposal of measures to improve infrastructure and public services, and disaster prevention facilities |

References

- Smith, L. Uses of Heritage; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, R. Heritage: Critical Approaches; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Baleviciene, D. Culture diversity management practices in Lithuania. Transform. Bus. Econ. 2022, 21, 319–335. [Google Scholar]

- Mekonnen, H.; Bires, Z.; Berhanu, K. Practices and challenges of cultural heritage conservation in historical and religious heritage sites: Evidence from North Shoa Zone, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. Herit. Sci. 2022, 10, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, J.; Zhou, C. Research Review and Prospects of Traditonal Villages in China. City Plan. Rev. 2017, 41, 74–80. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, M.; Chu, S.; Du, X. Safeguarding Traditional Villages in China: The Role and Challenges of Rural Heritage Preservation. Built Herit. 2019, 3, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Chen, Z. Analysis and prospect of hotspot research on active protection of traditional villages in China: Based on literature visualization. Chin. Foreign Archit. 2024, 5, 68–74. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, T. The concept and cultural connotation of traditional villages. Home Ownersh. 2018, 159+161. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hu, B.; Li, X.; Wang, X. Investigation Report on the Protection of Chinese Traditional Villages; Social Sciences Academic Press: Beijing, China, 2017. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Kai, Y.; Huijun, Z. Listing Villages for Conservation: Practices and Impacts of the Village Conservation Project in China. Hist. Environ. Policy Pract. 2024, 15, 344–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. The effects of commercialisation on urban heritage in Tianjin: A study of citizens’ livelihood in the Five Avenues (Wudadao) historical district. Built Herit. 2024, 8, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demgenski, P. Onstage: Exhibiting Intangible Cultural Heritage in China. China Perspect. 2023, 132, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Sun, D.; Lin, Y. Preservation or Revitalization? Examining the Conservation Status and Destructive Mechanisms of Tulou Heritage in Raoping, Chaozhou, China. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2025, 19, 441–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, R.G. China’s vernacular architectural heritage and historic preservation. Built Herit. 2024, 8, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, J.; Li, X. Heritage Value Assessment and Landscape Preservation of Traditional Chinese Villages Based on the Daily Lives of Local Residents: A Study of Tangfang Village in China and the UNESCO HUL Approach. Land 2024, 13, 1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Sun, J.; Wang, Z.; Jin, S. Influencing Factors of Street Vitality in Historic Districts Based on Multisource Data: Evidence from China. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2024, 13, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowker, G.C.; Star, S.L. Sorting Things Out: Classification and Its Consequences; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, E. Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Snow, D.; Benford, R.D. Ideology, Frame Resonance and Participant Mobilization. Int. Soc. Mov. Res. 1988, 1, 197–218. [Google Scholar]

- De la Torre, M. Values and Heritage Conservation. Herit. Soc. 2013, 6, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecco, M. A definition of cultural heritage: From the tangible to the intangible. J. Cult. Herit. 2010, 11, 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labadi, S.; Logan, W. Urban Heritage, Development and Sustainability: International Frameworks, National and Local Governance; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zeayter, H.; Mansour, A.M.H. Heritage conservation ideologies analysis—Historic urban Landscape approach for a Mediterranean historic city case study. HBRC J. 2018, 14, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzocchi, F. Diving Deeper into the Concept of ‘Cultural Heritage’ and Its Relationship with Epistemic Diversity. Soc. Epistemol. 2022, 36, 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterton, E.; Smith, L.; Campbell, G. The utility of discourse analysis to heritage studies: The Burra Charter and social inclusion. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2006, 12, 339–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumann, C.; Gfeller, A.É. Cultural landscapes and the UNESCO World Heritage List: Perpetuating European dominance. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2022, 28, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K.; Lennon, J. Cultural landscapes: A bridge between culture and nature? Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2011, 17, 537–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero, J. Heritage Conservation Future: Where We Stand, Challenges Ahead, and a Paradigm Shift. Glob. Chall. 2022, 6, 2100084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fusco, G.L.; Gravagnuolo, A. (Eds.) Adaptive Reuse of Cultural Heritage; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; p. 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R. Beyond “Natural” and “Cultural” Heritage: Toward an Ontological Politics of Heritage in the Age of Anthropocene. Herit. Soc. 2015, 8, 24–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, R.; Avrami, E. Heritage values and challenges of conservation planning. Manag. Plan. Archaeol. Sites 2002, 13–26. Available online: https://www.getty.edu/conservation/publications_resources/pdf_publications/pdf/mgt_plan_arch_sites_vl_opt.pdf#page=24 (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Gao, Q.; Jones, S. Authenticity and heritage conservation: Seeking common complexities beyond the ‘Eastern’ and ‘Western’ dichotomy. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2021, 27, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Beza, B.B.; Liu, C.; Wu, B.; Qiu, N. Differences in Perspectives Between Experts and Residents on Living Heritage: A Study of Traditional Chinese Villages in the Luzhong Region. Buildings 2024, 14, 4022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulios, I. Discussing strategy in heritage conservation: Living heritage approach as an example of strategic innovation. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 4, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haselberger, M.; Krist, G. Applied Conservation Practice Within a Living Heritage Site. Stud. Conserv. 2022, 67, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhao, X.; Wang, H.; Yan, J.; Yang, D.; Xie, K. Portraying heritage corridor dynamics and cultivating conservation strategies based on environment spatial model: An integration of multi-source data and image semantic segmentation. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raevskikh, E.; Di Mauro, G.; Jaffré, M. From living heritage values to value-based policymaking: Exploring new indicators for Abu Dhabi’s sustainable development. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranskūnienė, R.; Zabulionienė, E. Towards Heritage Transformation Perspectives. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R. Forgetting to remember, remembering to forget: Late modern heritage practices, sustainability and the ‘crisis’ of accumulation of the past. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2013, 19, 579–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moneta, A.; Hodgson, N.; Fearon, E. Re-interpreting intangible cultural heritage through immersive live performances to enhance memory-based institutions and foster community engagement. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2025, 31, 640–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M. Branding process of cultural heritage in the context of rural revitalization in China: A case study of Qingtian County. Int. J. Anthropol. Ethnol. 2025, 9, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, T. Beyond Eurocentrism? Heritage conservation and the politics of difference. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2012, 20, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J. Embodiment unbound: Moving beyond divisions in the understanding and practice of heritage conservation. Stud. Conserv. 2015, 60, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, P.Å. Impact of cultural heritage on tourists. The heritagization process. Athens J. Tour. 2018, 5, 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalaf, R.W. Authenticity or Continuity in the Implementation of the UNESCO World Heritage Convention? Scrutinizing Statements of Outstanding Universal Value, 1978–2019. Heritage 2020, 3, 243–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, P.R. Community heritage work in Africa: Village-based preservation and development. Conserv. Sci. Cult. Herit. 2014, 14, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOMOS. Delhi Declaration on Heritage and Democracy; ICOMOS: Delhi, India, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Avrami, E.A.; Mason, R.; de la Torre, M. Values and Heritage Conservation: Research Report; Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sully, D. Conservation Theory and Practice: Materials, Values, and People in Heritage Conservation. In The International Handbooks of Museum Studies; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 293–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterton, E.; Smith, L. The recognition and misrecognition of community heritage. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2010, 16, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarandona, J.A.G. Heritage as a Cultural Measure in a Postcolonial Setting. In Making Culture Count: The Politics of Cultural Measurement; MacDowall, L., Badham, M., Blomkamp, E., Dunphy, K., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2015; pp. 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, N. From values to narrative: A new foundation for the conservation of historic buildings. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2014, 20, 634–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arizpe, L. Cultural heritage and globalization. In Values and Heritage Conservation Research Report; Avrami, E., Mason, R., de la Torre, M., Eds.; Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 32–37. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/gci_pubs/values_heritage_research_report (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Poulios, I. Moving Beyond a Values-Based Approach to Heritage Conservation. Conserv. Manag. Archaeol. Sites 2010, 12, 170–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijesuriya, G. Living Heritage: A Summary. 2015. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/39407212/Living_Heritage (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Ginzarly, M.; Houbart, C.; Teller, J. The Historic Urban Landscape approach to urban management: A systematic review. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2019, 25, 999–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Nakajima, N. Community co-creation in living heritage conservation—From object-centered to people-centered planning for the ancient city of Pingyao. In Proceedings of the 29th CIPA Symposium “Documenting, Understanding, Preserving Cultural Heritage: Humanities and Digital Technologies for Shaping the Future”, Florence, Italy, 25–30 June 2023; pp. 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barile, S.; Saviano, M. From the management of cultural heritage to the governance of the cultural heritage system. In Cultural Heritage and Value Creation: Towards New Pathways; Golinelli, G.M., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 71–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, M.J. Intrinsic vs. Extrinsic Value; Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Stanford, CA, USA, 2019; Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2019/entries/value-intrinsic-extrinsic/ (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- MOHURD; MOC; SACH; MOF. Guidance on Strengthening the Conservation and Development of Traditional Villages (Jiancun [2012]184). 2012. Available online: https://www.waizi.org.cn/law/15381.html (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Tu, L.; Zhao, P.; Zhang, C. Discussions on the Theory of Conservation of Traditional Villages. Urban Dev. Stud. 2016, 23, 118–124. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Che, Z. Preserving Damage Neglected in Conservation of Traditional Villages. Huazhong Archit. 2008, 26, 182–184. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jing, F.; Ramele Ramli, R.; Nasrudin, N.A. Protection of traditional villages in China: A review on the development process and policy evolution. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2024. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Zhang, X.; Beza, B. Heritage authenticity and community participation in the living conservation of traditional villages. Dev. Small Cities Towns 2022, 40, 86–90+118. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J. The dilemma and way out of traditional village—Also talking about traditional village is another kind of cultural heritage. Folk Cult. Forum 2013, 218, 7–12. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, M. The analysis of living cultural standards in the protection of Chinese village heritage—Starting from the comparison between the Asia-Pacific Cultural Heritage Award and the evaluation of Chinese traditional villages. Chin. Gard. 2015, 31, 46–49. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shan, Q. From the Cultural Landscape to the Cultural Landscape Heritage (Part One). Southeast Cult. 2010, 214, 7–18. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

| Phase | Description | Main Actors |

|---|---|---|

| Evaluation and Application | Village surveys, submission of materials, mobilization for nomination | HURD at all levels, expert panels, village committees |

| Registration and Archiving | Inventory of heritage elements, value assessment, classification | County-level HURD, experts, local gov’t |

| Funding Allocation | Budget approval, project matching, fiscal disbursement | Finance departments, MOHURD |

| Conservation Planning | Preparation of conservation plans, zoning of repair priorities | Planning experts, design institutes, government |

| Inspection and Oversight | Monitoring implementation, spot checks, progress assessments | Higher-level authorities, supervising agencies |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shi, X.; Beza, B.B.; Liu, C.; Wu, B. Cognition–Paradigm Misalignment in Heritage Conservation: Applying a Correspondence Framework to Traditional Chinese Villages. Buildings 2025, 15, 3427. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15183427

Shi X, Beza BB, Liu C, Wu B. Cognition–Paradigm Misalignment in Heritage Conservation: Applying a Correspondence Framework to Traditional Chinese Villages. Buildings. 2025; 15(18):3427. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15183427

Chicago/Turabian StyleShi, Xiaofeng, Beau B. Beza, Chunlu Liu, and Binglu Wu. 2025. "Cognition–Paradigm Misalignment in Heritage Conservation: Applying a Correspondence Framework to Traditional Chinese Villages" Buildings 15, no. 18: 3427. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15183427

APA StyleShi, X., Beza, B. B., Liu, C., & Wu, B. (2025). Cognition–Paradigm Misalignment in Heritage Conservation: Applying a Correspondence Framework to Traditional Chinese Villages. Buildings, 15(18), 3427. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15183427