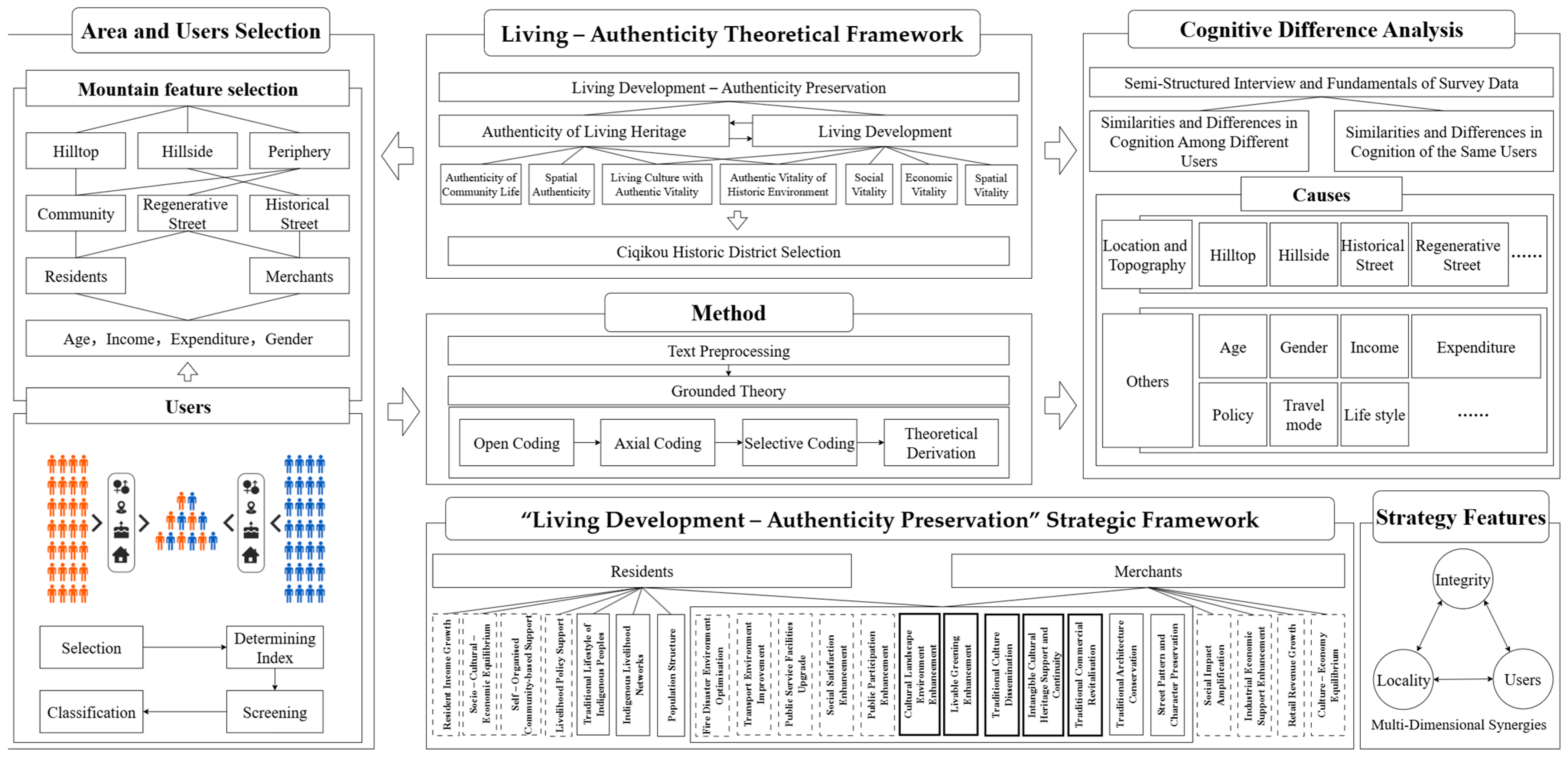

Cognitive Differences Between Residents and Merchants in Ciqikou Mountainous Historic Districts Oriented by the Living Development–Authenticity Preservation Framework

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Owing to their topographic characteristics, mountainous historic districts encounter more pronounced dual challenges of authenticity preservation and living development compared to their flatland counterparts.

- Challenges to the authenticity of living heritage occur in mountainous historic districts, where original residents have gradually moved out because of unmet living demands. Field investigations revealed that the actual resident population was significantly lower than expected, with the remaining low-income residents increasingly marginalised. As a result, the core authenticity of a living heritage site is at serious risk.

- The diverse and complex perceptions and needs of different user groups cannot be effectively balanced, particularly the conflicting demands of merchants and residents, hindering the sustainable development of the district.

- Cognitive differences among user groups across different locations within mountainous historic districts pose new challenges for living development in these areas.

- RQ1: What are the cognitive similarities and differences between merchants and residents of historic mountainous districts?

- RQ2: How are the cognitive differences between merchants and residents formed in mountainous historic districts?

- RQ3: How do topography and location influence the cognition of merchants and residents of mountainous historic districts?

- RQ4: How can an implementation strategy be constructed to coordinate living development with the authentic preservation of living heritage in mountainous historic districts?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Environmental Cognition of Different Users in Mountainous Historic Districts

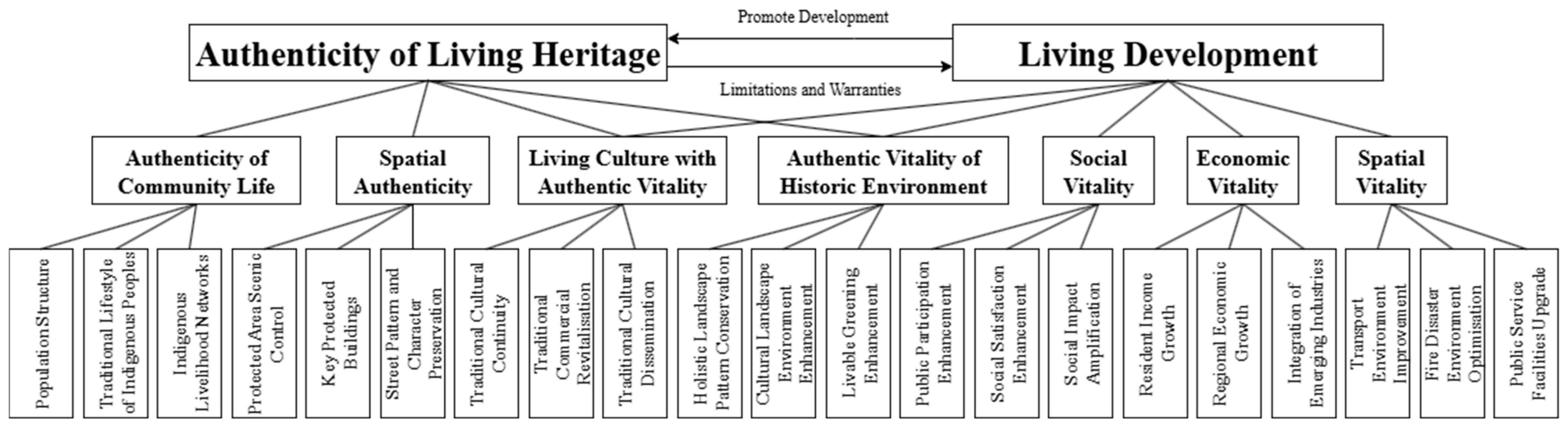

2.2. Living–Authenticity Theoretical Framework of Historic District

2.3. Grounded Theory Based Research on Mountainous Historic Districts

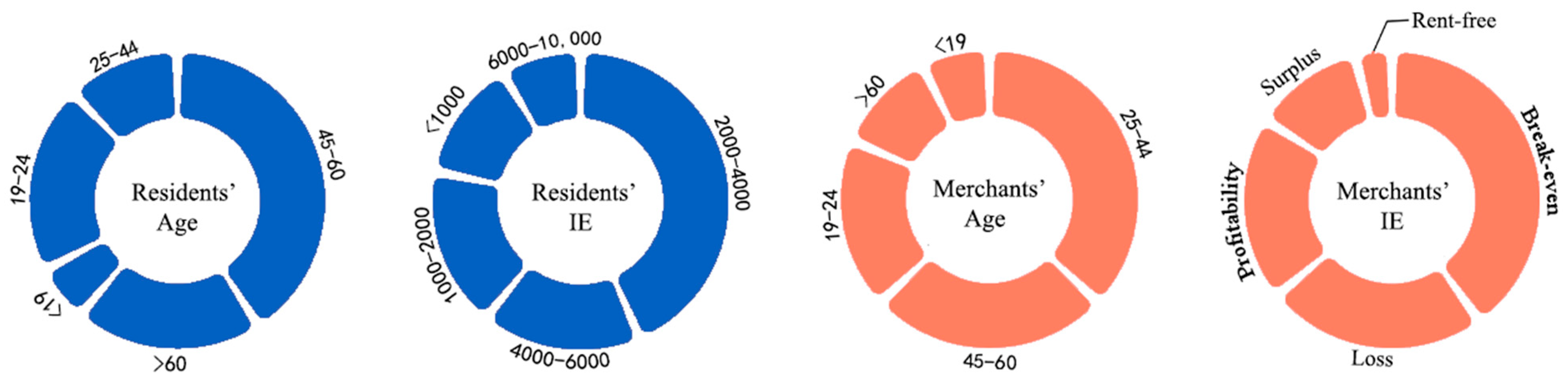

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Data Measures

3.3. Text Preprocessing

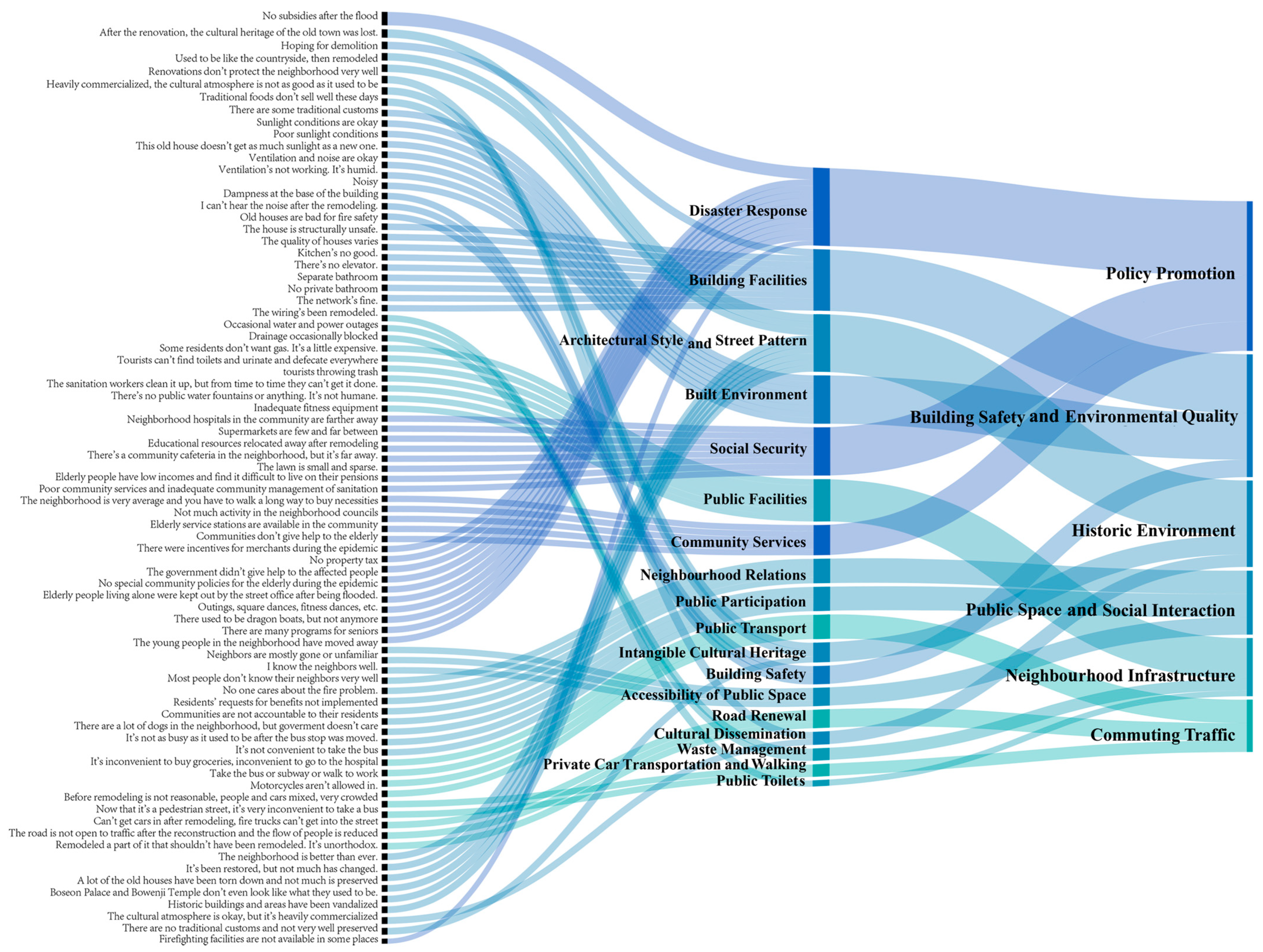

- Translation: The speech recordings of the interviews were transcribed into verbatim transcripts using iFLYRECv25.8.2250 software.

- Clarity: Noisy data were clarified, and invalid content such as meaningless filler words (e.g., ‘there is one’) were removed. Ambiguous or synonymous terms were standardised; for example, terms like ‘senior citizen’ and ‘old person’ were uniformly replaced with ‘older adults’.

- Text mining: Initially, newly combined terms not included in the built-in dictionary of the Weiciyun text-mining platform were manually identified from the verbatim transcript, such as the new compound ‘community canteen’ derived from ‘community’ and ‘canteen’. Next, the Weiciyun platform automatically extracted and merged potential new terms. The research team then manually reviewed and added relevant terms to the keyword library to support the subsequent coding. Keywords play a critical role in the data organisation process, as they accurately reflect the cognitive characteristics of the sentences and help identify core semantic content. In text mining, WeiCiyun’s fast and automated keyword extraction feature was used to easily and objectively identify high-frequency words; during keyword extraction, only nouns were retained. Typical high-frequency keywords from the residents group included ‘disaster’, ‘transportation’, ‘property management’, ‘culture’, ‘government’, and ‘hospital’. Similarly, high-frequency keywords extracted from the merchants group included ‘disaster’, ‘business’, ‘environment’, ‘public toilet’, ‘rent’, and ‘commercialisation’, reflecting the primary concerns of this group.

- Keyword matching: Subsequently, the extracted keywords were compiled into high-frequency word analysis results for residents and merchants, which were integrated separately to generate two distinct databases. These databases encompass all key entities of concern for both merchants and residents. Finally, the selected entities were retained and re-imported into NVivo software to retrieve the core textual content for subsequent coding.

3.4. Data Coding and Cognitive Result Output Based on Grounded Theory

- The analysis of cognitive similarities and differences and their influencing factors was conducted using grounded theory, cognitive map theory, and human–environment relationship theory and methods. The extraction of cognitive differences and similarities refers to the identification of variations in individuals’ cognitive attributes regarding the environment, behavioural intentions, and spatiotemporal cognition. In the text, they are expressed through terms such as ‘focus’, ‘attention level’, and ‘environmental cognition level’. The analysis included the differences in cognition between different users in the same environment, within the same user group in the same location, between different users in the same location, and between different users in different locations.

- The study of cognitive features and classifications was conducted by combining grounded theory with the living–authenticity theory. The core dimensions and classification patterns of cognition were systematically extracted using coding and cluster analyses.

- The analysis of the cognitive evaluation was based on grounded theory and cultural heritage value assessment. In this study, ‘satisfaction’ and ‘expectation’ were used to describe cognitive evaluation. This approach analyses how cognitive cognition translates into overall assessments of a district, including both rational judgment and emotional feedback, thereby informing renewal strategies for mountainous historic districts.

4. Results

4.1. Findings on Cognitive Similarities and Differences Between Merchants and Residents

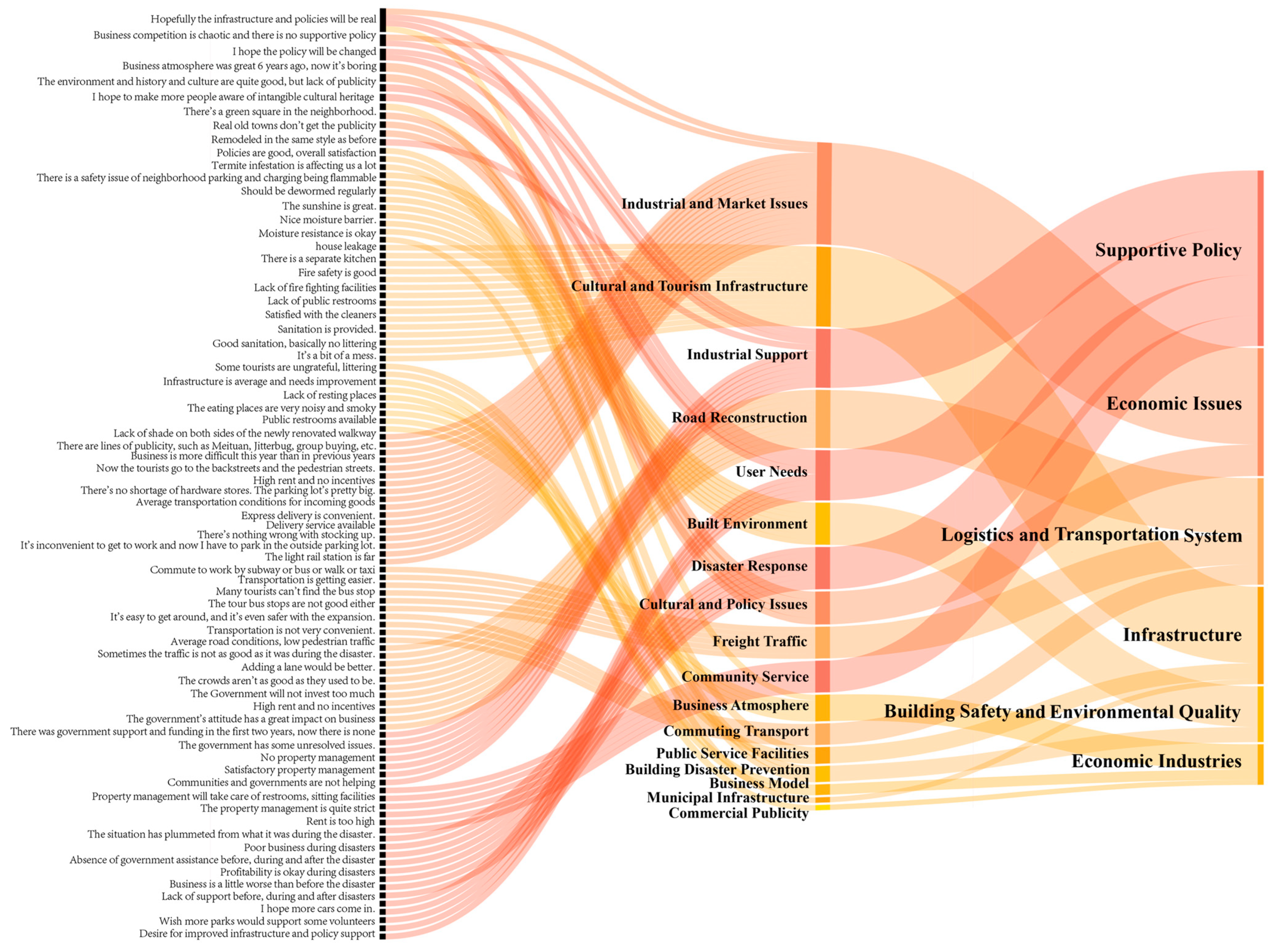

4.1.1. Open Coding Results

4.1.2. Axial Coding Results

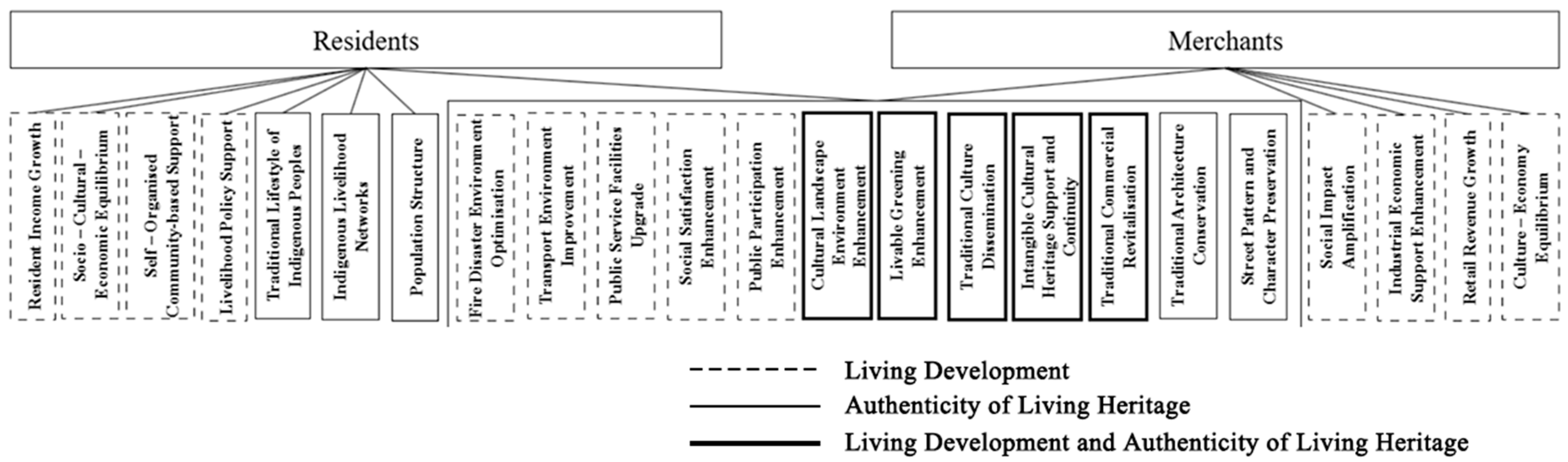

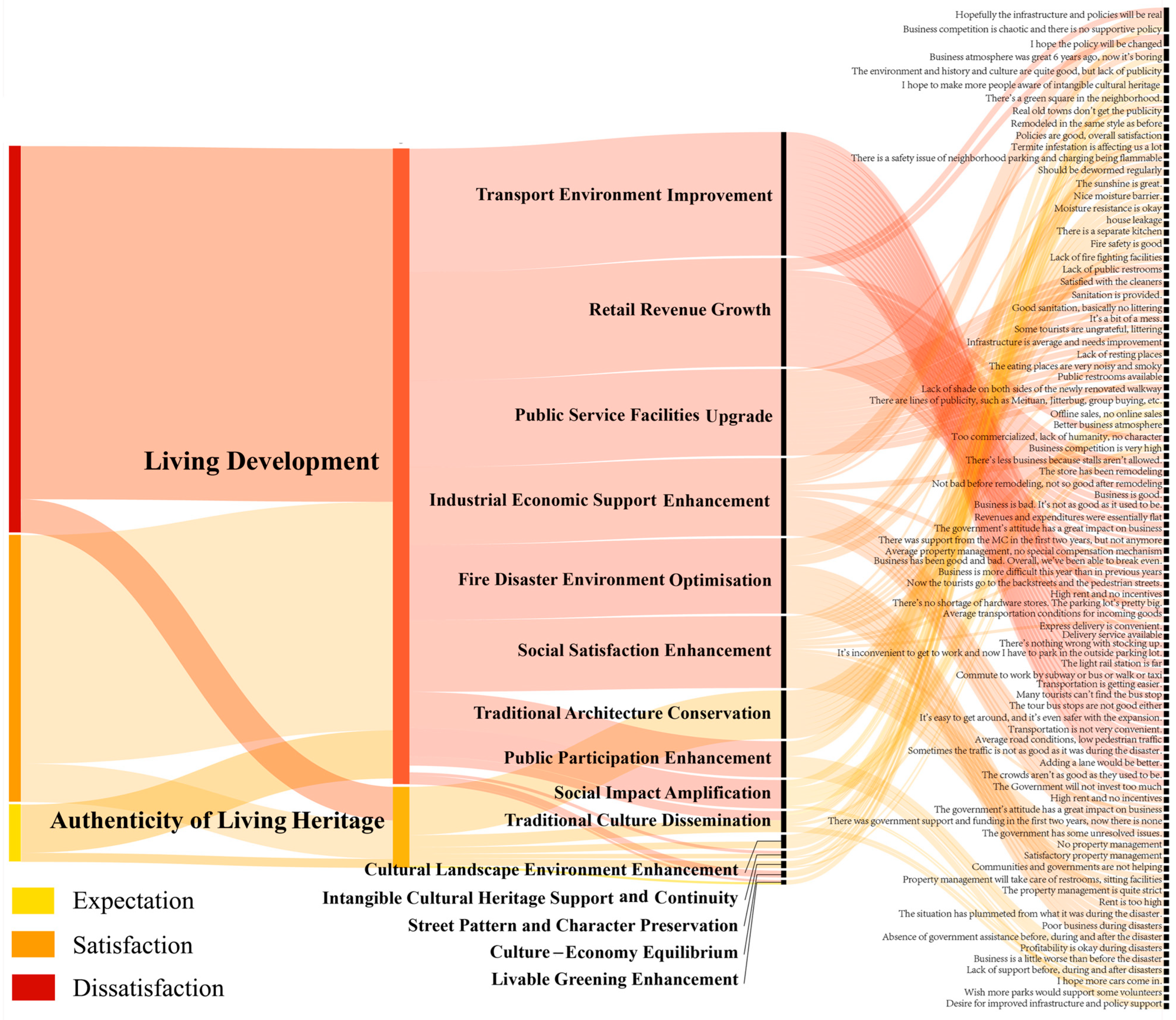

4.1.3. Selective Coding Results

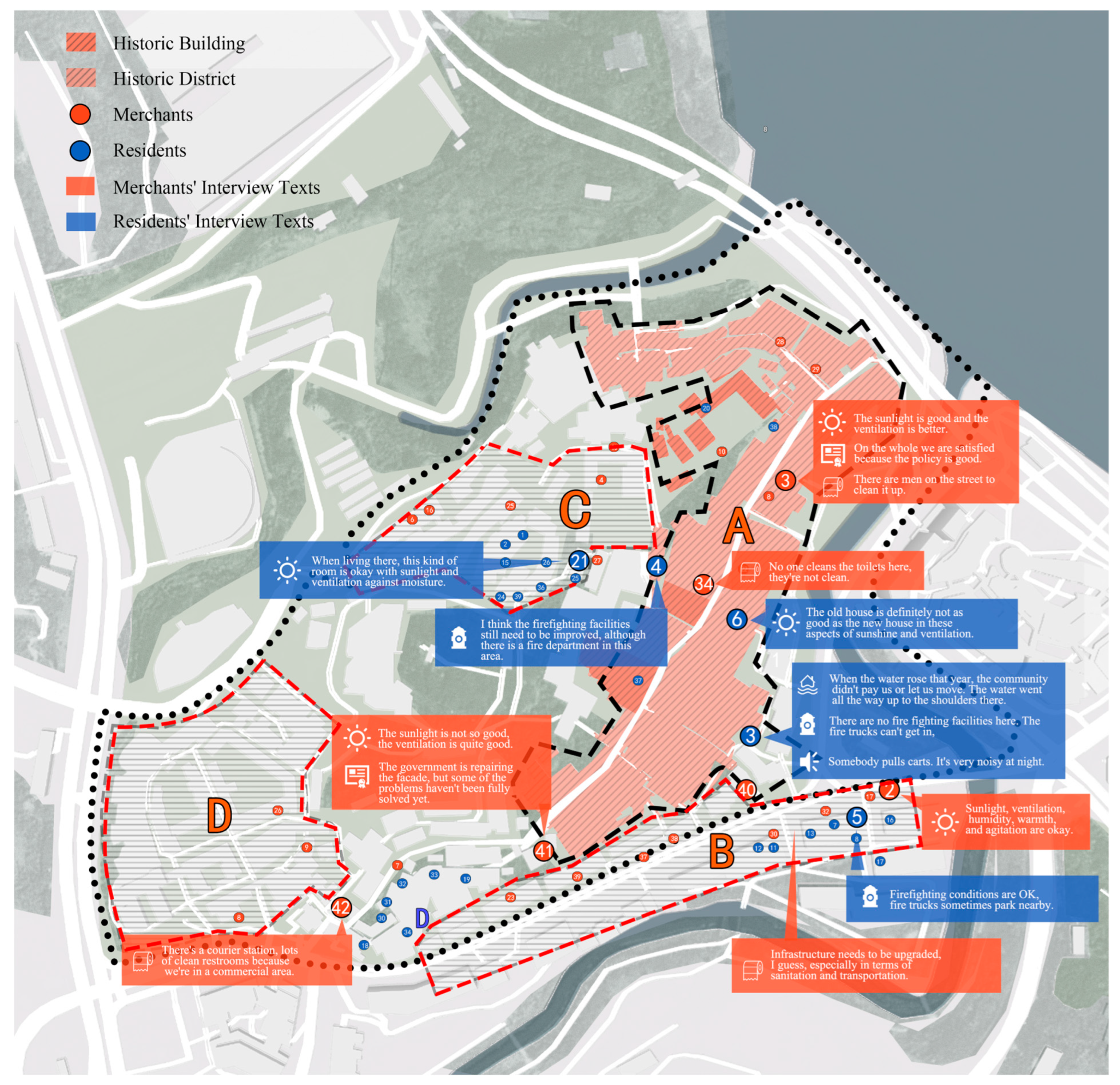

4.2. Findings on the Impact of Location on User Cognition in Mountainous Historic Districts

- There are no fire hydrants or extinguishers nearby. I don’t know about other locations, but at least in this alley there are none. If a fire breaks out, fire trucks won’t be able to get here. (Resident-03, Block A)

- Fire protection is fine. The fire safety officer comes to check daily—it’s part of his job. (Resident-09, Block B)

- Overall, we are quite satisfied because the policy support is very good. (Merchant-03, Block A)

- Commercial competition is chaotic, and there are no real supportive policies. The administrative committee rarely mediates conflicts between merchants. (Merchant-07, Block A)

4.3. Construction of the Living–Authenticity Cognitive Classification Framework

5. Discussion

5.1. Interpretation of Cognitive Similarities and Differences Between User Groups in Mountainous Historic Districts

5.2. Discussion on the Influence of Location on User Cognition

5.3. Construction of the Living Development–Authentic Preservation Strategic Framework

5.4. Implementation Dimensions of the Living Development–Authenticity Preservation Strategic Framework for Mountainous Historic Districts

5.5. Limitations and Future Study Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BERT | Bidirectional encoder representation from transformers |

| CRF | Conditional random field |

| ICCROM | International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property |

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization |

References

- Hussain, A.; Schmidt, S.; Nüsser, M. Dynamics of mountain urbanisation: Evidence from the Trans-Himalayan town of Kargil, Ladakh, India. Land 2023, 12, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, X.; Zhang, W.; Bing, W.; Yong, L. The Territorial Human-Environment Relationship System: Exploring the Spatial Development of the “Three Spaces” in Mountain Outdoor Tourism Destinations. J. Resour. Ecol. 2024, 15, 1219–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Song, T.; Tang, X. The Spatial Relationship between Cities and Mountains in Jiangnan Region in the Qing Dynasty Based on Historical Texts. ACM J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2024, 17, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenting, Y.; He, Z.; Shuying, Z. Sustainable development and tourists’ satisfaction in historical districts: Influencing factors and features. J. Resour. Ecol. 2021, 12, 669–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Gong, C. Creating an ecological historic district: Rethinking a Chinese challenge through the case of Oakland District, Pittsburgh. Procedia Eng. 2016, 145, 1572–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S. Holistic conservation of historic urban locations: A rethink under the international recommendation of “historic urban landscape”. Beijing Plan. Constr. 2012, 147, 27–30. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.S.; He, D.K.; Kovács-Andor, K. Design intervention of adaptive reuse for historic districts in Qingdao, China. Pollack Period. 2023, 18, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Zhu, C.; Fong, L.H.N. Exploring residents’ cognition and attitudes towards sustainable tourism development in traditional villages: The lens of stakeholder theory. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soewarno, N.; Wardhani, M.K. The transformation of Shophouse as an effort to continue the trading tradition in Pasar Baru location, Bandung. ARTEKS J. Tek. Arsit. 2023, 8, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z. Research on Inheritance and Development Strategy of Public Space of Traditional Settlements in Huxiang Region from the Perspective of Cultural and Tourism Integration. J. Sociol. Ethnol. 2024, 6, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Huang, Y.; Hu, D.; Wan, D. Evaluation of social network conservation in historical locations of mountainous towns in Chongqing, China. J. Mt. Sci. 2020, 17, 1763–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potdar, K.; Namrata, N.; Sami, A. Nature, culture and humans: Patterns and effects of urbanization in lesser Himalayan Mountainous historic urban landscape of Chamba, India. J. Herit. Manag. 2017, 2, 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zheng, L.; Ma, R.; Tian, H. Correlation between distribution of rural settlements and topography in Plateau-Mountain location: A study of Yunnan Province, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Fang, T.M.; Sun, Y.; Wang, B.; Shao, Z. Research on the correlation between component elements and psychological cognition of the spatial form of underground commercial street corners based on virtual reality technology. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 950593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoormans, L.; Czischke, D.; Pereira Roders, A.; de Jonge, W. “Do I See What You See?”—Differentiation of Stakeholders in Assessing Heritage Significance of Neighbourhood Attributes. Land 2023, 12, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, I.; Beunen, R. Regional planning in the Catalan Pyrenees: Strategies to deal with actors’ expectations, perceived uncertainties and conflicts. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2013, 21, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandermale, E.A.; Mason, C.W. Sustainable tourism development and Indigenous protected and conserved locations in sub-arctic Canada. Front. Sustain. Tour. 2024, 3, 1397589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.M.; Wall, G. Global-local relationships and governance issues at the Great Wall World Heritage Site, China. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 1067–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B.; Lane, B. Collaboration and partnerships for sustainable tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 1999, 7, 179–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; He, F.; Hu, L. Community empowerment under powerful government: A sustainable tourism development path for cultural heritage sites. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 752051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz, S.A. SDG 17 and global partnership for sustainable development: Unraveling the rhetoric of collaboration. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1155828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.; Jiang, M. Ecological and intensive design tactics for mountain cities in western China: Taking the main district of Chongqing as an example. In Green City Planning and Practices in Asian Cities Sustainable Development and Smart Growth in Urban Environments; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 133–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Chiou, S.-C. A Study on the Sustainable Development of Historic District Landscapes Based on Place Attachment among Tourists: A Case Study of Taiping Old Street, Taiwan. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Liu, J. Comparative Study of Cultural Landscape Perception in Historic Districts from the Perspectives of Tourists and Residents. Land 2024, 13, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quang, T.D. Is living heritage ignored? Revisiting heritage conservation at Cham living-heritage sites in Vietnam. Herit. Soc. 2022, 15, 46–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baillie, B. Living Heritage Approach Handbook; ICCROM: Rome, Italy, 2009; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Lowenthal, D. Changing criteria of authenticity. In Proceedings of the Nara Conference on Authenticity in Relation to the World Heritage Convention: Proceedings, Nara, Japan, 1–6 November 1995; p. 121. [Google Scholar]

- Stovel, H. Origins and influence of the Nara document on authenticity. APT Bull. 2008, 39, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Tomlan, M.A.; Jokilehto, J.I. A History of Architectural Conservation. APT Bull. 1999, 35, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unesco, R. Concerning the safeguarding and contemporary role of historic locations. Nairobi 1976, 11, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Poulios, I. A living heritage approach: The main principles. In The Past in the Present: A Living Heritage Approach; Ubiquity Press: London, UK, 2014; pp. 129–133. [Google Scholar]

- Foo, R.; Krishnapillai, G. Preserving the intangible living heritage in the George Town World Heritage Site, Malaysia. J. Herit. Tour. 2018, 14, 358–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Guo, Q.; Yuan, J.; Li, H.; Fu, B. Research on the conservation methods of Qu Street’s Living heritage from the perspective of life continuity. Buildings 2023, 13, 1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulios, I. Discussing strategy in heritage conservation: Living heritage approach as an example of strategic innovation. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 4, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakri, A.F.; Zaman, N.Q.; Kamarudin, H. Understanding local community and the cultural heritage values at a World Heritage City: A grounded theory approach. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, S.; Duan, W. A Post-Evaluation Study on the Renewal of Public Space in Qianmen Street of Beijing’s Central Axis Based on Grounded Theory. Buildings 2024, 14, 3969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, P.F.; Lee, M.Y.; Wong, J.W.C. Assessing community attitudes toward industrial heritage tourism development. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2020, 18, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, M.; Taheri, S.; Shabani, A. Regenerating historical districts through tactical urbanism: A case study of Sarpol neighborhood in Isfahan Province, Iran. Front. Archit. Res. 2023, 12, 1234–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Fan, P.; Yue, W.; Huang, J.; Li, D.; Tian, Z. Assessing polycentric urban development in mountainous cities: The case of Chongqing Metropolitan location, China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrlich, D.; Melchiorri, M.; Capitani, C. Population trends and urbanisation in mountain ranges of the world. Land 2021, 10, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertram, D.; Lambracht, M.; Chilla, T. Settlement Systems in Mountain Regions: A Research Gap? Mt. Res. Dev. 2024, 44, A1–A9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyussenbayev, A. Age Periods Of Human Life. Adv. Soc. Sci. Res. J. 2017, 4, 2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H. Bert meets chinese word segmentation. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.09292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. 1967. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/nursingresearchonline/citation/1968/07000/the_discovery_of_grounded_theory__strategies_for.14.aspx (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Scanlon, P. Using targeted embedded probes to quantify cognitive interviewing findings. In Advances in Questionnaire Design, Development, Evaluation and Testing; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 427–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komak, F.A.; Bakar, N.A.A.; Aziz, F.A.; Ujang, N. The impact of public infrastructure on neighbourhood liveability: A study of residents’ cognition and satisfaction. J. Urban Reg. Anal. 2023, 15, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stumpf, T.S.; Swanger, N. Tourism involvement-conformance theory: A grounded theory concerning the latent consequences of sustainable tourism policy shifts. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 23, 618–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vojnovic, I.; Ligmann-Zielinska, A.; LeDoux, T.F. The dynamics of food shopping behavior: Exploring travel patterns in low-income Detroit neighborhoods experiencing extreme disinvestment using agent-based modeling. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0243501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempf, I.; Dutta, P. Transformative social policies as an essential buffer during socio-economic crises. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Huq, S.; Puthuvayi, B. How to satisfy stakeholders? An attempt to model satisfaction of stakeholders of a historic urban conservation location: A case study. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2024; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumelzu, A.; Estrada, M.; Jara, C.; Peña, C.I. Effects of the Built Environment on Pedestrian Accessibility in Neighbourhoods in Southern Chile. The case of Temuco, Chile. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 503, 012093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Li, J.; Mei, D. An Empirical Analysis on How the Building Quality, Tourism Attraction and Tourism Public Service Influence the Satisfaction of Tourism Real Estate Consumption. Am. J. Ind. Bus. Manag. 2018, 8, 1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhang, X.; Dai, Z.; Hermaputi, R.L.; Hua, C.; Li, Y. Spatial layout and coupling of urban cultural relics: Analyzing historical sites and commercial facilities in district iii of Shaoxing. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Hu, L.; Wu, J.; Shan, Q.; Li, W.; Shen, K. Investigating the influencing factors of the cognition experience of historical commercial streets: A case study of Guangzhou’s Beijing road pedestrian street. Buildings 2024, 14, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, W.; Shu, P.; Ren, D.; Liu, R. The Multifaceted Impact of Public Spaces, Community Facilities, and Residents’ Needs on Community Participation Intentions: A Case Study of Tianjin, China. Buildings 2025, 15, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcaide Manthey, N. The role of community-led social infrastructure in disadvantaged areas. Cities 2024, 147, 104831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Xuan, Y.; Zhou, Z. Influence of Building Density on Outdoor Thermal Environment of Residential location in Cities with Different Climatic Zones in China—Taking Guangzhou, Wuhan, Beijing, and Harbin as Examples. Buildings 2022, 12, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero Puerta, L.; Lorente García, R. Illuminating the path: A methodological exploration of grounded theory in doctoral theses. Qual. Res. J. 2024, 24, 384–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Block | Elevation Difference | Accessibility | Infrastructure Completeness Level | D/H Value | Merchants (Number) | Residents (Number) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | ◒ | ◒ | ◒ | ○ | ● | ◒ |

| B | ○ | ● | ● | ● | ◒ | ◒ |

| C | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● |

| D | ● | ● | ● | ◒ | ● | ○ |

| Coordination Layer | Pathway Layer | Goal Layer |

|---|---|---|

| Living development | Spatial vitality | Fire disaster environment optimisation |

| Transportation environment improvement | ||

| Public service facilities upgrade | ||

| Economic vitality | Resident income growth | |

| Socio-cultural-economic equilibrium | ||

| Self-organised community-based support | ||

| Social vitality | Livelihood policy support | |

| Social satisfaction enhancement | ||

| Public participation | ||

| Living development and authenticity of living heritage | Living culture with authentic vitality | Traditional commercial revitalisation |

| Intangible cultural heritage support and continuity | ||

| Traditional cultural dissemination | ||

| Authentic vitality of historic environment | Cultural landscape environment enhancement | |

| Liveable greening enhancement | ||

| Authenticity of living heritage | Spatial authenticity | Traditional architecture conservation |

| Street pattern and character preservation | ||

| Authenticity of community life | Population structure | |

| Traditional lifestyle of indigenous peoples | ||

| Indigenous livelihood networks |

| Coordination Layer | Pathway Layer | Goal Layer |

|---|---|---|

| Living development | Spatial vitality | Fire disaster environment optimisation |

| Transportation environment improvement | ||

| Public service facilities upgrade | ||

| Economic vitality | Retail revenue growth | |

| Culture–economy equilibrium | ||

| Industrial economic support enhancement | ||

| Social vitality | Social impact amplification | |

| Social satisfaction enhancement | ||

| Public participation | ||

| Living development and authenticity of living heritage | Living culture with authentic vitality | Traditional commercial revitalisation |

| Intangible cultural heritage support and continuity | ||

| Traditional cultural dissemination | ||

| Authentic vitality of historic environment | Cultural landscape environment enhancement | |

| Liveable greening enhancement | ||

| Authenticity of living heritage | Spatial authenticity | Traditional architecture conservation |

| Street pattern and character preservation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gong, C.; Ran, R.; Hu, C. Cognitive Differences Between Residents and Merchants in Ciqikou Mountainous Historic Districts Oriented by the Living Development–Authenticity Preservation Framework. Buildings 2025, 15, 3274. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15183274

Gong C, Ran R, Hu C. Cognitive Differences Between Residents and Merchants in Ciqikou Mountainous Historic Districts Oriented by the Living Development–Authenticity Preservation Framework. Buildings. 2025; 15(18):3274. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15183274

Chicago/Turabian StyleGong, Cong, Ruihan Ran, and Changjuan Hu. 2025. "Cognitive Differences Between Residents and Merchants in Ciqikou Mountainous Historic Districts Oriented by the Living Development–Authenticity Preservation Framework" Buildings 15, no. 18: 3274. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15183274

APA StyleGong, C., Ran, R., & Hu, C. (2025). Cognitive Differences Between Residents and Merchants in Ciqikou Mountainous Historic Districts Oriented by the Living Development–Authenticity Preservation Framework. Buildings, 15(18), 3274. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15183274