Abstract

As China’s housing market shifts from quantity expansion to quality improvement, consumer expectations for both functionality and aesthetics in residential products are rising. Drawing on the Stimulus–Organism–Response (S-O-R) framework, this study develops a perceptual mechanism model to examine how display design identity and facility service satisfaction influence millennials’ willingness to purchase improved housing, mediated by an elevated sense of style and moderated by upward social comparison. Based on structural equation modeling with 491 valid responses, the findings reveal that facility service satisfaction has a significant direct effect on purchase intention, while display design identity affects behavior indirectly through an elevated sense of style. Moreover, the elevated sense of style serves as a critical mediator in multiple pathways, and its effect is significantly moderated by upward social comparison. This study contributes to the housing consumption literature by clarifying how functional and symbolic factors jointly shape purchase intentions, especially under the influence of social comparison dynamics. It also highlights the role of artistic display design as a symbolic stimulus that enhances style perception and self-identity among younger consumers, offering practical insights for improved housing design and marketing strategies.

1. Introduction

In the process of high-quality urban development worldwide, housing has become a central concern in national governance systems. It is closely tied not only to the safety and dignity of residents’ daily lives but also to broader issues of social equity, spatial justice, and urban resilience. In China, the housing market has undergone a rapid transformation from state-led supply to market-oriented development, fueling urban expansion and economic growth. However, this shift has also revealed systemic challenges such as structural imbalances and functional mismatches [1]. On one hand, the growing supply of housing has not fundamentally alleviated the challenges of affordability in major cities. High property prices, down payments, and living costs continue to burden a significant portion of the young population [2]. On the other hand, the phenomenon of high vacancy rates in some cities—indicative of structural prosperity—suggests a deep misalignment between housing quality, residential experience, and consumer demand. In the post-COVID-19 era, the public’s expectations for health, safety, environmental sustainability, and cultural atmosphere have risen substantially [3,4], prompting a shift from function-oriented housing development toward quality-oriented housing supply strategies.

Amid this new consumption era, millennials—those born between 1981 and 1996—are emerging as the dominant demographic in the improved housing market [5]. This generation, typically characterized by higher educational attainment and digital literacy, has grown up in the information age and exhibits high autonomy and selectivity in lifestyle and consumption decisions. Compared with previous generations, millennials regard the concept of “home” not only as a space for security and utility but also as a medium for personalized expression, emotional value, and social connectivity [6,7]. This evolution in aesthetic preference is shaped by multiple sociocultural transformations, including new modes of information dissemination, the lifestyle aesthetics shaped by social media, and the desire for emotionally healing spaces amid fast-paced living conditions. As a result, aesthetics, service quality, and design sophistication are becoming key dimensions for evaluating residential value. Millennials tend to favor residential products that not only meet functional needs but also reflect symbolic taste, cultural expression, and emotional resonance—a trend often described as symbolic consumption [8], which is reshaping the product logic and marketing strategies of the real estate sector. Improved housing has thus become an important housing type for middle-class households seeking to upgrade residential quality. Unlike basic necessity housing, improved housing refers to dwellings that are significantly optimized compared with existing living conditions in terms of functional configuration, spatial aesthetics, community amenities, and service standards, enabling a better match to lifestyle preferences and emotional values [9]. More specifically, improved housing not only satisfies basic safety and functional needs but also integrates considerations of interior design, architectural aesthetics, property management, intelligent facilities, and cultural taste. As such, it is often described in the market as affordable luxury housing—a relatively accessible housing type oriented toward mid- to high-end aesthetics and service experiences [10]. Purchasers of this type of housing typically already possess basic homeownership and are motivated by family structure adjustments, status mobility, or lifestyle transitions. Their purchase behaviors are thus characterized by higher subjective involvement and multidimensional value orientations.

In academic discourse, research on housing issues has diverged into multiple streams. One tradition, grounded in institutional economics, focuses on housing supply mechanisms [11], policy intervention and spatial resource allocation [12], emphasizing the effectiveness of regulatory frameworks [13]. Another body of work, situated within consumer behavior and cultural sociology, examines the symbolic meaning of housing, identity construction, and aesthetic value, exploring how residential space becomes embedded in self-concept and social networks [14]. More recently, the rise of user experience and spatial perception theories has prompted scholars to examine the role of display design, service quality, and perceptual factors in shaping willingness to purchase and consumer satisfaction, emphasizing the transformation of housing from a physical commodity to a perceived space [15,16,17]. Despite these advances, important research gaps remain. First, most studies emphasize the linear effects of physical aesthetics or management services on user satisfaction, but relatively few investigate the psychological mechanisms through which design perceptions shape consumers’ purchase intentions [18]. Second, prior work often conceptualizes consumer responses to housing as a direct mapping between function and perception, overlooking how housing displays trigger identity formation and symbolic consumption motives [19]. Third, in the high-aesthetic, high-expectation context of improved housing, existing models lack explanatory power regarding mediating and moderating mechanisms [20].

At this interdisciplinary nexus, the present study employs the Stimulus–Organism–Response (SOR) theoretical framework, integrates symbolic consumption theory and spatial perception pathways, and introduces two core independent variables—art display identification sense and facility service satisfaction—along with an elevated sense of style as a mediating mechanism and Upward Social Comparison as a moderating variable. This study aims to construct a psychological perception pathway model that explains how residential display design influences consumers’ willingness to purchase for improved housing. In doing so, it seeks to bridge the physical and symbolic dimensions of housing, address the theoretical inquiry into the triadic drivers of “Function–Aesthetics–Identification” in improved housing consumption, and offer practical and empirical insights for enhancing urban housing quality and governance strategies.

2. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Display Design Identity and Willingness to Purchase for Improved Housing

2.1.1. Display Design Identity

The concept of identification has been widely studied in sociology and psychology. It generally refers to the emotional resonance, sense of belonging, or psychological alignment that individuals form with a particular group, object, or idea. This psychological state facilitates a strong emotional connection and a favorable attitude toward the object. Erik Erikson [21] first defined identity as the process of harmonizing self-awareness with societal expectations. In the context of consumer behavior, identification manifests as an emotional attachment to brands, products, or services and serves as a major driver of purchasing behavior. Display design identity is an extension of the identification concept in the fields of commercial design and visual merchandising. It refers to the psychological identification that consumers form with specific display styles, presentation techniques, or spatial aesthetics, which enhances their willingness to purchase. The concept of display design originally focused on how visual presentation affects consumer perception and behavior. W. Singleton [22] proposed three methods of display design—checklists, formal procedures, and behavioral theory—and discussed the merits and limitations of realistic versus artificial displays, thereby laying an early theoretical foundation for display design Identity. In the context of fashion window displays, E. Choi [23] examined how design originality influences consumer attitudes and purchase intentions. She found that features such as uniqueness, humor, and visual appeal significantly boost consumer identification, especially for high-involvement consumers who are more strongly influenced by distinct design elements. From a cognitive science perspective, M. Hegarty [24] argued that visual spatial displays enhance cognitive processing and, consequently, affect consumer decisions—an effect closely linked to the formation of identification. Zhao [25] further advanced a “human-centered” design philosophy, emphasizing the psychological and physiological needs of consumers in display design. Rational spatial layouts and visual elements can enhance visual experience and trigger purchase motivations, thus directly fostering display design Identity. As residential consumption shifts from function-oriented to experience-driven, display design Identity becomes an essential psychological variable affecting willingness to purchase. Display design is not merely an aesthetic extension of space but a communicative language that interacts with consumer aesthetic expectations. To refine the construct, this study divides display design Identity into two dimensions: art display Identification sense and design philosophy identification sense.

Art display identification sense refers to consumers’ subjective recognition of the visual aesthetics, stylistic taste, and artistic expression conveyed through residential spaces. It emphasizes the visual expression and aesthetic resonance embedded in the living environment. At its core, this construct concerns the “visualized aesthetics” of space, manifested through consumers’ affective recognition of artistic decorations, color schemes, and compositional design elements. As an initial perception-level trigger variable, it directly shapes emotional responses and attentional allocation. Unlike the deeper symbolic recognition reflected in an elevated sense of style, art displays an identification sense that highlights sensory perception and first impressions, characterized by immediacy and intuitiveness. The theoretical foundation of this construct can be traced back to Goffman’s notion of “front-stage presentation” in social performance theory [26], wherein spatial decorations and artistic settings form an integral part of identity enactment. It also aligns with Lefebvre’s spatial production theory, which posits that “spatial perception is primarily visual” [27]. Accordingly, positioning art display identification sense as an independent variable enables the capture of consumers’ first-layer perceptual triggers when confronted with residential display designs. In practice, spatial layout, color coordination, decorative details, and even light-shadow interplay can be regarded as visual language. The resulting artistic atmosphere often borrows from and reconstructs the compositional logic and emotional tone of classical paintings. For instance, residential displays inspired by Impressionist techniques such as Monet’s soft lighting and natural ambiance, or Renaissance-style balance and chromatic rationality as seen in Raphael’s works, may evoke an immersive experience, thereby enhancing the emotional appeal of space. Kim and Heo [28] point out that the inclusion of installation art, reproduction paintings, stylistic wall hangings, or textured oil-painted walls in residential interiors can evoke emotional-level aesthetic identification and strengthen consumers’ memory of the brand’s cultural image. Meier [29] further emphasizes that thematically styled scenes inspired by Van Gogh’s nocturnes, Modigliani’s silhouettes, or Morandi’s palettes offer narrative scenarios that enable consumers to project their ideal lifestyle aesthetics, thereby enhancing their willingness to purchase for improved housing.

Design philosophy identification sense, on the other hand, reflects consumers’ cognitive recognition of the design values, conceptual intentions, and functional logic embedded in residential spaces. This form of identification is often rooted in the resonance between the consumer and the cultural claims, ecological values, or lifestyle philosophy expressed through design. Its mechanism aligns with Bourdieu’s theory of “taste as a marker of social distinction” [30]—the recognition of design philosophy reflects an individual’s projection of social identity and cultural capital. This construct is distinguished from art display identification sense based on the dual processing model in aesthetic psychology: the former captures a value-level, deliberative cognition, while the latter represents a sensory-level, immediate response. For instance, a consumer may experience aesthetic resonance with a particular residential display without necessarily identifying with the lifestyle philosophy it conveys, underscoring their conceptual independence. By introducing design philosophy identification sense, this study seeks to capture the deeper psychological mechanism through which consumers connect spatial design with their lifestyle preferences and personal values. Such recognition not only shapes evaluative judgments of residential spaces but also informs the symbolic and cultural meaning ascribed to improved housing. Liu and Zhao [31], in their study of cultural metaphor in design, found that residential design conveying cultural narratives and values significantly enhances identity resonance and product loyalty. Dimitriadis [32] further noted that when consumers perceive alignment between the design philosophy of a residential project and their personal values, their emotional attachment and brand trust are substantially strengthened.

Thus, the dual-dimensional structure of display design identity reveals a psychological pathway in improved housing consumption that progresses from sensory stimulation to value recognition. Consumers are initially drawn by artistic display that stimulates visual pleasure, followed by a deeper resonance with the underlying design philosophy. Together, these dimensions jointly facilitate the formation of willingness to purchase for improved housing.

2.1.2. Willingness to Purchase for Improved Housing

Willingness to purchase is a core concept in consumer behavior research. It refers to an individual’s inclination to purchase a product or service when facing a specific offering. This willingness is influenced by a variety of factors, including product quality, price, brand reputation, personal needs, and external environment. It represents a critical prerequisite for actual purchasing behavior and reflects consumers’ attitudes and decision tendencies. Importantly, willingness to purchase involves not only rational evaluation but is also shaped by emotional, cognitive, and cultural factors. Improved housing refers to housing products that consumers purchase to enhance their quality of life or upgrade their living environment. These homes typically feature superior functionality, larger spaces, better locations, or more modern designs.

Unlike first-time homebuyers, those purchasing improved housing often have prior buying experience and are more discerning in evaluating housing quality, design style, and supporting facilities. Their decisions are influenced not only by traditional variables like price and location but also by more complex psychological and lifestyle factors. These buyers pay greater attention to aspects such as space layout, natural lighting, ventilation, and environmentally friendly features—factors that enhance both living comfort and long-term property value. Juan et al. [33] proposed a hybrid decision-making model showing that personalized design strategies significantly increase the sales performance of improved housing. Purchasing such homes is not solely a rational act but also involves deep emotional motivations. Buyers often expect improved housing to enhance their quality of life and deliver greater happiness for themselves or their families. Huda Othman [34] found that visual display design can foster emotional resonance and enhance consumer identification with a residential space, thus increasing their willingness to purchase. The purchase decisions of improved housing buyers are frequently influenced by display design.

In the context of display design Identity, consumers develop emotional identification with particular design styles, content, or spatial experiences. This identification stems not only from visual responses but also from deeper psychological resonance that subsequently influences purchase behavior. According to symbolic consumption theory, consumers use specific goods or environments to express identity and taste. Residential display design serves as a key medium for such symbolic expression. Through interior style and aesthetics, consumers subconsciously associate the projected lifestyle with their self-identity, thereby reinforcing emotional attachment and identification.

Due to their higher expectations for living quality, improved housing buyers pay greater attention to the overall effect of display design. A carefully curated residential display allows consumers to perceive not only functionality and comfort but also an idealized vision of life. Based on symbolic consumption theory, display designs that project lifestyle symbols enhance emotional identification and, in turn, affect willingness to purchase. Othman argues that the way a residence is presented not only reflects spatial arrangements but also influences motivation through emotional resonance. Buyers in the improved housing segment demand more than basic utility; they seek alignment between the spatial aesthetics and their own lifestyle. Compared to first-time buyers, these consumers emphasize upgrades in environmental quality and living comfort. Therefore, the quality of display design plays a crucial role in decision-making. Well-executed displays that vividly communicate home layout, advantages, and lifestyle can significantly increase willingness to purchase. Sensory perception, spatial layout, and presentation style all directly influence consumer identification and motivation.

Although research on how architectural display influences housing purchase behavior has gained increasing attention, it largely remains at a descriptive level and lacks theoretical refinement regarding its underlying symbolic mechanisms and aesthetic-spatial effects. Existing studies predominantly focus on the impact of aesthetic style, spatial layout, and visual attractiveness of display design on consumers’ attention and emotional responses. However, there is still no consensus on the psychological pathways through which these sensory elements are transformed into willingness to purchase, particularly in relation to the construction of identification. Much of the literature fails to situate display design within the theoretical contexts of symbolic consumption and spatial aesthetics, thereby limiting theoretical advancement and interdisciplinary integration. From a symbolic consumption perspective, Baudrillard [35] and Bourdieu both argue that spaces and objects serve not only utilitarian functions but also act as media of social symbolism. Housing display constitutes a “visual representation of lifestyle”, where consumers evaluating a show unit are not merely assessing functional structures but making symbolic judgments of identity fit along aesthetic and cultural dimensions (Singh [36]). As Goffman [37] posits, the artistic style, cultural metaphors, lifestyle scenarios, and value expressions embedded in display design collectively construct a consumable identity theater, generating a sense of identification that mediates consumers’ purchase decisions. For example, Meier highlights in research on themed housing that narrative staging can evoke consumers’ psychological projection of an ideal lifestyle, leading to affective preferences. Fielding [38] further emphasizes that the cultural branding and design philosophy embedded in interior spaces provide the basis for the congruence between consumers’ cognitive style preferences and lifestyle orientations, thereby shaping both the formation and intensity of their purchase intention.

Recent studies have revealed three emerging trends. First, Whang et al. [39], in their study of smart housing in Korea, demonstrated a significant positive relationship between interior spatial imagery and individual identification, showing that the visual atmosphere of space can effectively enhance willingness to purchase. Second, Spyrou et al. [40] found that immersive spatial display, enabled by XR technologies, strengthens lifestyle imagination and self-identification, underscoring the symbolic effect of display design as a psychological trigger. Similarly, Shakirova [41], through Kansei engineering, confirmed that the explicit expression of “prestige” in residential spaces acts as a crucial mediating variable between consumer taste and purchase intention, revealing the identity-metaphor attribute inherent in design style. Theoretical contributions from spatial aesthetics provide a more powerful explanatory framework. Lefebvre [42] argued that the production of space is first visual and perceptual, and only subsequently functional and institutional. In this sense, the initial trigger of residential spaces stems from the sensory pleasure and immersion they evoke, which constitutes the psychological basis of art display identification sense. By contrast, design philosophy identification sense reflects consumers’ deeper-level cognitive responses to cultural orientations, ecological concepts, and lifestyle propositions conveyed through design. Petty and Cacioppo’s [43] Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM) further supports the independence and complementarity of sensory and cognitive pathways in persuasion, highlighting the dual-path role of display design identification in shaping purchase behavior.

Although some studies have preliminarily confirmed the positive influence of display design on housing purchase intention (Ho et al. [44]), most have not systematically analyzed it from the psychological perspective of identification construction. In particular, research on the differences and complementarities between artistic-level identification and philosophical-level identification remains insufficient. Moreover, existing empirical studies are largely concentrated in retail, hospitality, and cultural-creative product domains, while targeted theoretical models and empirical evidence are still lacking for the high-involvement, high-value, and long-cycle consumption context of improved housing. Therefore, this study introduces two sub-dimensions—art display identification sense and design philosophy identification sense—to construct a dual-identification pathway model, aiming to fill the gap in the existing literature concerning the psychological mechanisms of identification construction. Accordingly, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1.

Display design identity positively influences willingness to purchase for improved housing.

H1a.

Art display identification sense positively influences willingness to purchase for improved housing.

H1b.

Design philosophy identification sense positively influences willingness to purchase for improved housing.

2.2. Facility Service Satisfaction and Willingness to Purchase for Improved Housing

The concept of facility service satisfaction originates from the customer satisfaction theories developed in the 1980s, primarily in the domains of marketing and service management, where it was used to assess consumers’ overall satisfaction with products or services. Oliver [45] noted that early models focused on the direct impact of core product attributes, including quality, value, and user experience. With increasing market competition and diversified consumer needs, researchers gradually recognized that the surrounding environment, particularly facilities and services, also plays a significant role in shaping satisfaction, especially in long-term, high-involvement consumption scenarios such as residential housing. As a key antecedent variable influencing willingness to purchase for improved housing, facility service satisfaction has garnered increasing academic and practical attention. It encompasses both the completeness and modernization of physical infrastructure and the responsiveness and professionalism of residential service provisions. It reflects consumers’ holistic perception of convenience, comfort, and quality of life [46]. Typically, facility service satisfaction is conceptualized as comprising two interrelated but distinct dimensions: facility provision satisfaction and service provision satisfaction.

Facility provision satisfaction refers to consumers’ evaluations of the physical infrastructure provided by residential communities. This includes factors such as transportation accessibility, parking availability, fitness centers, green spaces, and children’s activity zones. The modernization and smartness of facilities are also increasingly emphasized as evaluative criteria. As research on improved housing consumption deepens, scholars have begun to incorporate service quality into models of brand loyalty and consumer trust. In an empirical study of homebuyers in Malaysia, Li [47] found that the adequacy of community infrastructure significantly shapes first impressions and overall satisfaction, particularly in mid- to high-end improved housing markets, where facility completeness directly correlates with perceived quality of life. Wu [48] emphasized that younger consumers place particular importance on the spatial accessibility and functional integration of surrounding environments. They are especially attracted to residential projects featuring green landscapes, cultural amenities, and recreational spaces. This “facilities-as-lifestyle” valuation reflects a generational shift in consumer preferences. Collectively, these studies suggest that facilities provide not only functional utility but also contribute to emotional trust and satisfaction, thereby facilitating purchase conversion in the improved housing market.

In contrast to the tangibility of facilities, service provision satisfaction focuses on the quality and responsiveness of intangible services within the community. This includes property management efficiency, safety assurance, smart access systems, sanitation maintenance, and complaint resolution. Kumar et al. [49] emphasized that high-quality community management services not only increase resident satisfaction and loyalty but also enhance trust in residential brands—thereby acting as a strategic fulcrum for improved housing consumption. Kaluthanthri and Jayawardhana [50] found that perceived service quality, especially regarding maintenance timeliness, staff professionalism, and digital management platforms, significantly influences consumers’ overall evaluation of residential value. Grum [51] added that high standards in facility upkeep and service delivery strengthen residents’ sense of spatial belonging, increasing long-term residency intentions and recommendation likelihood. Through a field experiment in France, Larceneux and Guiot [52] investigated buyers’ responses to customized and interactive services in residential developments. Their results show that developers who enhance customer experience through personalization and interactivity significantly improve brand trust and satisfaction. When homebuyers perceive professional engagement and individualized service from developers, they are more likely to purchase the residential project. This phenomenon is particularly relevant to high-end improved housing, where consumers expect elevated service standards. Accordingly, Facility Service Satisfaction not only promotes willingness to purchase by improving immediate residential experience but also reinforces customer loyalty and trust through brand and service management. In light of the above, this study puts forward the following hypotheses:

H2.

Facility service satisfaction positively influences willingness to purchase for improved housing.

H2a.

Facility provision satisfaction positively influences willingness to purchase for improved housing.

H2b.

Service provision satisfaction positively influences willingness to purchase for improved housing.

2.3. Elevated Sense of Style

Elevated sense of style refers to consumers’ perceived sense of elegance, quality, and refinement conveyed through design. It extends beyond visual aesthetics to encompass cultural meaning, artistic expression, and alignment with identity. Within the context of real estate consumption, perceived sophistication reflects the consumer’s sense of “lifestyle elevation” and “taste upgrading”, which emerges after comprehensively evaluating the display style and design philosophy of residential spaces. The conceptual foundation of this construct can be traced to Bourdieu’s theory of symbolic capital, which posits that space is not merely a physical habitat but also a symbolic externalization of social taste. The perception of sophistication is often shaped through design elements such as visual order, material language, color systems, and spatial narrativity, which collectively reinforce consumers’ psychological affirmation that “I am worthy of such a lifestyle”. This sense of elevated style allows consumers to emotionally bond with a product or space through the evocation of a refined lifestyle or cultural taste. Wiedmann et al. [53] emphasize that consumers often treat style as a symbolic element for distinguishing social class and lifestyle, especially when faced with products of high perceived value. The recognition of brand image and lifestyle taste is frequently established through such symbolic associations. In design practice, an elevated sense of style is communicated through spatial composition, materiality, color harmony, and ambient lighting, all of which visually encode a narrative of refined living. Consumers may form emotional connections with these stylistic codes and incorporate the product or space into their envisioned ideal life. Makkar and Yap [54], in a comparative study of fashion and residential design, found that products with strong aesthetic and symbolic value generate greater psychological projection of identity extension. Consumers are more willing to pay a premium to gain emotional fulfillment and social recognition. In the context of upscale residential design, an elevated sense of style is especially prominent, functioning as a visualization of lifestyle philosophy. Chuon et al. [55] argue that in luxury housing, design language has moved beyond functionalism toward symbolic stylization. The embedded values—such as cultural status and personal taste—now form the core competitive advantage in both design and marketing. In this trend, an elevated sense of style is no longer a superficial reaction to beauty but a resonance between design narrative and consumers’ cultural capital.

Display design identity reflects whether consumers perceive design as an extension of their personal identity, lifestyle, or social status. In the housing context, it mainly manifests through consumer recognition of residential style and design philosophy. When design aesthetics align with consumers’ personal taste or values, it enhances their elevated sense of style, which in turn shapes purchasing behavior. Willingness to purchase is influenced not only by functional evaluations but also by emotional experiences, price perception, and brand identification. In the residential domain, it depends on both utilitarian features and emotional resonance, including perceived lifestyle enhancement. Pei-Yu Tseng and Su-Fang Lee [56] demonstrated that aesthetic design significantly increases willingness to purchase by eliciting positive emotions and enhancing the perceived value of the visual experience. Based on the SOR model, they found that aesthetic features trigger emotional resonance and promote consumer recognition of design style, thus increasing residential appeal. In the improved housing context, an elevated sense of style enhances the perceived visual elegance of residential design. It leads consumers to identify not only with a home’s functionality but also with the lifestyle it symbolizes. Yu and Lee [57] studied how aesthetic value perception influences consumer attitudes and purchase intentions. They found that emotional and aesthetic attributes of high-end design are critical drivers of decision-making. Elevated sense of style, by delivering elegance through design details and overall composition, enhances emotional attachment and aesthetic pleasure, ultimately stimulating willingness to purchase. Braun [58] explored how architectural aesthetics influence housing investment decisions and concluded that an elevated sense of style affects not only perceived market value but also social identification with the design. In the improved housing market, stylistic sophistication conveys refined lifestyles and social prestige, thereby reinforcing psychological identification and influencing purchase behavior. Liu, Rodriguez, and Huang [59] examined the mediating role of design aesthetics in shaping willingness to purchase and found that when consumers perceive sophistication, elegance, and cultural refinement in a product or space, it strengthens their emotional satisfaction and sense of identity extension. Design thus becomes not merely a visual embellishment but a symbol of taste and lifestyle. Through this style elevation mechanism, an emotional connection between consumers and products is established. In the improved housing market, stylistic refinement affects both aesthetic recognition and social identity, ultimately motivating purchase decisions. Elevated sense of style, therefore, serves a dual role: emotional catalyst and psychological identifier.

Accordingly, this study adopts the Stimulus–Organism–Response (S-O-R) model as its theoretical framework, in which display design is conceptualized as the external stimulus (S), perceived sophistication as the psychological mediating variable (O), and purchase intention as the final response (R). The S-O-R model has been widely applied in consumer behavior research, as it systematically explains how external design elements trigger emotional and attitudinal changes that ultimately translate into behavioral intentions. However, in the high-involvement and high-risk context of housing purchase decisions, the S-O-R framework demonstrates certain limitations in its adaptability. To address this, the present study extends and adapts the S-O-R model, emphasizing that psychological variables are not merely direct affective responses to stimuli, but rather outcomes of more complex cognitive evaluations and cultural coding. Within this context, perceived sophistication should be understood as a resultant construct, emerging from consumers’ multidimensional aesthetic evaluations of design styles, cultural taste, and lifestyle orientations, and thus carrying strong symbolic and social implications.

To enhance explanatory power, this study further incorporates lifestyle segmentation theory, perceived value theory, and social practice theory as complementary theoretical foundations. Lifestyle segmentation theory highlights how consumer preferences for design are shaped by values, social needs, and identity orientations, with perceived sophistication serving as a visualized manifestation of lifestyle. Perceived value theory emphasizes the integrated effect of functional, emotional, and symbolic values, thereby clarifying how perceived sophistication bridges aesthetic experience and purchase intention. In addition, social practice theory frames housing purchase as a process of identity construction, underlining the cultural expressiveness and social significance embedded in spatial consumption. This perspective further illustrates how perceived sophistication functions as a specific embodiment of “taste practices” in consumer society.

Therefore, perceived sophistication should not be simplistically understood as the direct outcome of external stimuli, but rather as an integrated consumer response to residential design across cultural, social, and emotional dimensions. It constitutes the key mediating mechanism that transforms aesthetic recognition into purchase intention. Based on this, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H3.

Elevated sense of style mediates the relationship between display design identity and willingness to purchase for improved housing.

As residential consumption in China gradually shifts from survival-oriented housing demand to the pursuit of a quality lifestyle, homebuyers’ evaluative criteria for residential products have moved beyond traditional concerns such as price and location. Instead, they now emphasize integrated perceptions of living experience, environmental quality, and cultural aesthetics. Within the improved housing market, facility service satisfaction has become an increasingly salient factor influencing consumers’ willingness to purchase. It not only offers functional convenience but also psychologically stimulates consumers’ imagination of an ideal lifestyle. However, while the practicality and completeness of facilities and services remain important, they are insufficient on their own to explain why consumers are willing to pay a premium for specific residential developments. In assessing residential facilities and services, consumers often do not simply ask whether the offerings are available or sufficient, but whether they convey a sense of stylistic tone and align with their personal taste and identity. On this basis, an elevated sense of style has gained increasing scholarly attention as a psychological mediating variable. It refers to consumers’ perception of elegance, cultural sophistication, and aesthetic refinement conveyed through residential facilities and services.

In the housing market, when facility and service design incorporate aesthetic elements, spatial storytelling, and cultural cues, it can effectively evoke emotional connection and identity projection among consumers, thereby enhancing their willingness to purchase. Huang [60] demonstrated that service quality significantly enhances willingness to purchase by improving customer satisfaction, and that an elevated sense of style further reinforces this effect as a mediating mechanism. When service quality is perceived to be high, consumers not only experience functional convenience but also a sense of luxury and refined experience. This perceived elevated sense of style strengthens identification with the residential product, thereby influencing purchase intention. Kuo et al. [61] explored the relationship between service quality and customer satisfaction, finding that higher levels of quality and convenience significantly improve satisfaction. However, the ultimate determinant of purchasing decisions lies in consumers’ perception of service elegance. High-end design, perceived convenience, and service quality jointly shape a sense of elevated style, which mediates the relationship between customer satisfaction and willingness to purchase. Consumers’ emotional reliance on services is thus reinforced by this sense of style, leading to stronger purchasing intentions. Liao et al. [62] further pointed out that service quality alone does not fully determine customer satisfaction or purchase intention. Rather, brand image and an elevated sense of style also play pivotal roles in shaping consumer decisions. When the design language of facility services communicates a premium lifestyle, consumers not only report higher satisfaction but also develop stronger brand loyalty as a result of this stylistic resonance. As a mediating variable, an elevated sense of style enhances the emotional identification between brand and consumer, thus amplifying the impact of facility service satisfaction on willingness to purchase. Similarly, Hidayati et al. [63] investigated the relationship between aesthetic perception in facility service design and purchasing behavior. They found that when consumers experience strong emotional resonance with the design and aesthetic value embedded in facility services, their willingness to purchase increases significantly. This suggests that an elevated sense of style, through its affective regulatory role, strengthens the influence of facility service satisfaction on consumer decision-making. For improved housing, the refined style embedded in facility and service design not only enhances the functional quality of living but also promotes aesthetic identification, thereby encouraging consumers to make purchasing decisions.

Facility service satisfaction thus influences consumers not only through tangible benefits but also by delivering a sense of elevated experience and stylistic refinement. As the core psychological mechanism in this pathway, an elevated sense of style transforms satisfaction into a strong willingness to purchase, enhancing emotional attachment and brand loyalty through affective alignment, identity construction, and aesthetic immersion. In light of the above, this study puts forward the following hypotheses:

H4.

Elevated sense of style mediates the relationship between facility service satisfaction and willingness to purchase for improved housing.

2.4. Upward Social Comparison

Upward Social Comparison refers to the cognitive process whereby individuals compare themselves with others who are perceived to perform better or to be more successful in certain domains. This comparative behavior can activate self-improvement motivation, prompting individuals to strive for higher goals or superior lifestyles. In consumer behavior, upward social comparison often motivates individuals to select products or services that can elevate their social standing. In the context of the high-end residential market, this tendency drives consumers to choose housing options that convey a sense of refinement and symbolic identity. Liu et al. [64] investigated how upward social comparison on social networking platforms influences impulsive buying behavior. Their findings suggest that when individuals compare themselves with others who demonstrate higher standards of living, such comparisons can trigger impulsive purchases aimed at reducing perceived lifestyle gaps. This dynamic similarly applies to the high-end housing market: when consumers perceive that a given residential property may enhance their lifestyle, they are likely to be motivated by comparison-induced aspirations, thereby increasing their willingness to purchase. Olivos et al. [65] further emphasized that Upward Social Comparison typically activates self-improvement motivation, particularly when individuals become aware of others’ higher quality of life or greater achievements. Through such comparisons, consumers may develop heightened expectations that purchasing a high-end residence will help them attain their ideal lifestyle, thereby increasing their willingness to purchase. This suggests that upward social comparison may positively moderate the relationship between an elevated sense of style and willingness to purchase, by enhancing consumers’ psychological identification with luxury housing products. Wang et al. [66] provided additional evidence showing that when individuals compare themselves to peers with higher living standards on social media, they often experience a sense of social distance, which in turn fosters a compensatory motivation to close that gap. This motivation leads consumers to prefer high-end residential options that project elevated social status and aesthetic value, thus enhancing their willingness to purchase. Their study highlights the positive moderating effect of upward social comparison on residential purchase decisions, particularly in premium markets.

Upward social comparison prompts consumers to regard model home displays or others’ housing standards as benchmarks for an ideal lifestyle, thereby generating a motivation for self-enhancement. This variable functions as a moderating mechanism in the pathway from perceived elevation of taste to purchase intention, theoretically rooted in Festinger’s social comparison theory [67] and Goffman’s dramaturgical perspective of everyday performance. In the context of high-end residential consumption, individuals engage in comparison to answer the psychological question: “Do I belong to this level?”, which in turn influences their decision to engage in symbolic consumption behaviors to maintain or elevate their social positioning. In today’s context, where housing serves as a means of reproducing symbolic capital, upward social comparison is not merely a confounding factor but rather a psychological driving force behind the consumer’s perception of taste and construction of the self. Therefore, incorporating it into the model as a moderating variable helps uncover the social-psychological foundation behind the purchase intentions for improved housing. Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H5.

Upward social comparison positively moderates the relationship between an elevated sense of style and willingness to purchase for improved housing.

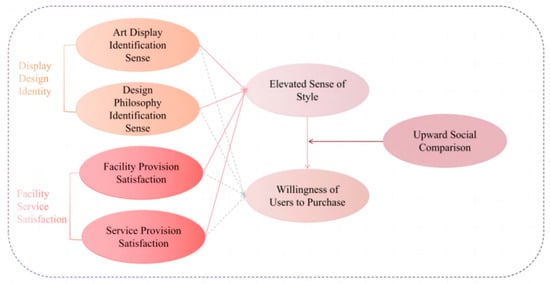

This study adopts the Stimulus–Organism–Response (S-O-R) model as its theoretical framework to construct a path model for analyzing consumers’ willingness to purchase improved housing (see Figure 1). The Stimulus layer includes display design identity and facility service satisfaction, reflecting environmental cues perceived during visits to residential spaces and community services. These external stimuli influence consumers’ attitudes and emotional evaluations. The organism layer introduces an elevated sense of style as the core psychological mediator, capturing internal processes such as aesthetic resonance, cultural alignment, and identity refinement. Unlike traditional cognitive or emotional mediators, it emphasizes symbolic recognition and identity construction. The Response layer includes both willingness to purchase and upward social comparison. The latter reflects consumers’ reflection on social identity and ideal lifestyle projection after exposure to style-related stimuli, offering theoretical value from a social practice perspective.

Figure 1.

Model drafting diagram.

By extending the traditional S-O-R framework, this study adapts it to the high-involvement and symbolic nature of improved housing decisions. It incorporates dual-process and perceived value theories and draws on cultural capital perspectives to reveal how housing aesthetics influence both emotional response and identity reproduction.

3. Research Design

3.1. Subjects and Questionnaire Distribution

This study targeted the millennial generation in China, a cohort widely recognized as the core consumer group driving the demand for improved housing due to their transitional life stage, rising income levels, and distinct aesthetic orientations. To obtain a sample that is both empirically relevant and analytically robust, a multi-source purposive sampling strategy was employed, integrating offline and online channels. (1) Offline survey: Questionnaires were administered at real estate sales centers located in tier-one and strong tier-two cities, which are critical markets for improved housing consumption. These sites represent high-involvement contexts where potential buyers actively engage in housing search and evaluation. Trained research assistants distributed and supervised the completion of questionnaires, ensuring voluntary participation and reducing response bias. This method enabled the collection of data from consumers with concrete purchase intentions and direct exposure to housing display environments. (2) Online survey: In parallel, questionnaires were disseminated via real estate–related digital platforms, including housing forums and social media groups frequented by prospective buyers. To strengthen sample qualification, screening questions (e.g., current housing ownership status, intention to purchase within the next 12 months) were incorporated, ensuring that respondents were genuine participants in the improved housing market rather than casual observers.

The hybrid data collection strategy enhances both external representativeness and internal validity by capturing perspectives from consumers across different engagement contexts—those physically interacting with sales environments and those digitally active in housing-related communities. Furthermore, to ensure instrumental validity, the questionnaire design underwent iterative expert review by four senior real estate practitioners (with over 15 years of market experience) and two academic specialists in housing studies, who evaluated the content for clarity, contextual relevance, and theoretical alignment. A total of 550 responses were initially obtained. After rigorous screening to remove incomplete submissions, logically inconsistent answers, and cases not meeting inclusion criteria, 491 valid questionnaires remained, yielding a response validity rate of 89.3%. This final dataset provides a methodologically sound and theoretically grounded empirical basis for analyzing the psychological mechanisms underlying purchase intentions for improved housing.

3.2. Measurement of Variables

The quantitative paired research method was used in this study. By reviewing the relevant literature, some previous well-established scales were used to measure the willingness to pay of the users of light luxury residential projects. By reviewing the relevant literature, some previous well-established scales were used to measure the willingness to pay of the users of light luxury residential projects. The first part investigates the demographic information of the respondents. The second part collects data on the respondents’ art display identification sense, design philosophy, identification sense, facility provision, and the number of users of light luxury residential projects. Identification sense, facility provision satisfaction, service provision satisfaction, elevated sense of style, social comparison, and willingness of users to purchase. Respondents were asked to rate these items. A 5-point Likert scale (1: strongly disagree; 2: disagree; 3: neither agree nor disagree; 4: agree; 5: strongly agree) was used for each item.

Specifically, the questionnaire questions were adapted from the previous well-established research literature. For example, the questionnaire design for the sense of style enhancement: In the recent literature, DPES has become a predictor of aesthetic emotions (e.g., aesthetic intensity). In this study, we refer to the aesthetic inclination and aesthetic experience Maturity Research Scale developed by Jacobi et al. [68] from DPES, combined with the Moral Enhancement Scale. At the same time, the survey questionnaire was reviewed by four experts with 15 years of real estate sales experience.

This study adopted a structured questionnaire to measure key constructs related to consumers’ purchase intention toward improved housing. The questionnaire consisted of seven sections: art display identification, design philosophy identification, facility provision satisfaction, service provision satisfaction, elevated sense of style, upward social comparison, and willingness of users to purchase. All variables were operationalized through multiple-item constructs and measured using a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree).

Art Display Identification was measured using four items adapted from the aesthetic consumption and luxury perception frameworks developed by Hong et al. [69] and Aquino & Reed [70], focusing on the perceived harmony, elegance, and symbolic quality of art displays within residential environments. Design philosophy identification was measured using four items referencing the work of Zong et al. [71], which assessed how users identify with design intent, aesthetic coherence, and functional expression in residential design. Facility Provision Satisfaction was measured using three items derived from Biscaia et al. [72], focusing on respondents’ satisfaction with the environmental, recreational, and community-level infrastructure provisions. Service Provision Satisfaction included three items adapted from Yoon and Uysal [73], evaluating the perceived responsiveness, quality, and reliability of property management services. Elevated sense of style was measured using five items based on Weigand et al. [74] and Hou et al. [75], particularly drawing on the disposition to process aesthetic stimuli (DPES) and the moral elevation scale, with adaptations made to fit the context of high-aesthetic housing consumption. Items reflect users’ pursuit of higher-level aesthetic lifestyles and symbolic capital through residential space. Upward social comparison was assessed using three items drawn from the social comparison orientation scale developed by Gibbons and Buunk [76], measuring respondents’ tendency to compare their residential consumption and lifestyle with those of more affluent or style-conscious others. Willingness of Users to Purchase was evaluated using four items referencing Kang et al. [77] and Ajzen & Driver’s [78] behavioral intention framework, measuring the willingness to pay a premium for housing with superior design and quality. All scale items were translated and back-translated to ensure linguistic and conceptual equivalence. Minor localization revisions were made based on expert panel feedback. Appendix A provides the full item list and source references.

All measurement items were initially adapted from validated scales in the prior literature and revised through localization and expert review to ensure relevance to the context of improved housing in Chinese urban settings. To further ensure content validity, the questionnaire was reviewed by four domain experts with over 15 years of real estate market experience.

4. Data Analysis

4.1. Reliability Test

Reliability represents the consistency of the measurement results of the scale, and the internal consistency of each conceptual dimension of the scale was examined by the Cronbach α coefficient, which is a commonly used reliability test standard. If the Cronbach α coefficient value of the scale is greater than 0.7, it means that the reliability of the scale meets the requirements of the study. The overall reliability of the scale reached 0.906, and the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of all dimensions were greater than 0.7. Combining the overall scale and the reliability of each variable, the reliability coefficient value of the research data was higher than 0.7, which indicates that the data’s overall reliability is of high quality and can be used for further analysis.

4.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) helps identify which observations vary together to model measurements, providing researchers with an initial understanding of the domain’s conceptual structure. It also aids in reducing the number of relevant observations by downscaling the data, simplifying subsequent structural equation modeling. Initially, the data underwent the KMO test and Bartlett’s test of sphericity to assess their suitability for factor analysis. SPSS 25 was used for the testing and factor analysis, and the results are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Exploratory factor analysis table.

The factor analysis was conducted to examine the construct validity of the measurement model. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was 0.886, well above the recommended threshold of 0.8, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (p < 0.001), indicating that the data were suitable for factor analysis. Using principal component analysis with varimax rotation, seven factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 were extracted, collectively explaining 69.07% of the total variance. The rotated factor solution showed clear and theoretically consistent loadings: all items loaded strongly (above 0.67) on their intended constructs, with no significant cross-loadings, supporting the discriminant and convergent validity of the seven factors. These factors were labeled as follows: art display identification sense, design philosophy identification sense, facility provision satisfaction, service provision satisfaction, willingness to purchase, and elevated sense of style.

4.3. Validation Factor Analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted using AMOS 24.0 to evaluate the measurement model. The model demonstrated good fit with the data: χ2/df = 1.91, GFI = 0.909, RMSEA = 0.043, NFI = 0.909, IFI = 0.955, RMR = 0.03, TLI = 0.949, and CFI = 0.954, all of which meet standard acceptability thresholds. These results support both the convergent and discriminant validity of the constructs. Convergent validity was affirmed as items loaded strongly on their intended factors, while discriminant validity was established through stronger correlations within constructs than between them, confirming that the measured constructs are distinct and well-represented by their indicators.

The factor loadings for the observed variables were all greater than 0.6, and the p-values for all topics were below 0.001, indicating statistical significance. Composite Reliability (CR) reflects the internal consistency of the items within each dimension, with a CR value typically greater than 0.7 considered acceptable. Average variance extracted (AVE) measures the average explanatory power of a dimension over its items, with a value greater than 0.50 typically required. As shown in Table 2, the scale meets the criteria for structural validity.

Table 2.

Table of structural validity test results.

As shown in Table 3, the diagonal bold values represent the square roots of the AVE, while the lower triangles display the Pearson correlations between dimensions. The square roots of the AVE are higher than the correlations with other constructs, indicating that discriminant validity is achieved.

Table 3.

Table of results of the discriminant validity test.

4.4. Common Method Deviation Test

To assess common method bias, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted. The results indicated that the first factor accounted for 27.379% of the total variance, which is below the critical threshold of 40%. This suggests that common method bias is not a major concern in this study.

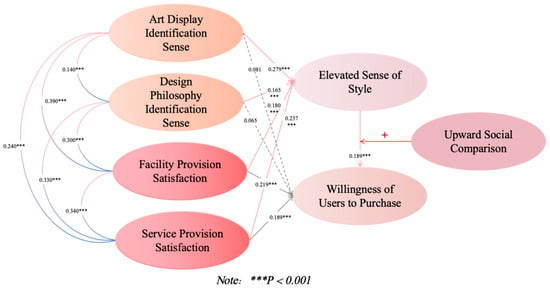

4.5. Path Analysis

Art display identification sense, design philosophy identification sense, facility provision satisfaction, service provision satisfaction, willingness of users to purchase, and elevated sense of style, the latent variable factor path model is shown in Figure 2, and its model fitting results and hypothesis validation results are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Modified structural equation modelling diagram.

As shown in Table 4, ADIS → ESS (p < 0.001), DPIS → ESS (p < 0.001), FPS → ESS (p < 0.001), SPS → ESS (p < 0.001), FPS → WUP (p < 0.001), SPS → WUP (p < 0.001), and ESS → WUP (p = 0.001 < 0.05), and standardized path coefficients of 0.279, 0.165, 0.18, 0.237, 0.219, 0.189, 0.189 were all greater than 0, and all of the above hypotheses were valid. Among them, ADIS→ WUP (p = 0.122 > 0.05) and DPIS → WUP (p = 0.183 > 0.05), the hypotheses were not valid.

Table 4.

Path analysis results table.

4.6. Tests for Mediating Effects

This study employed the Bootstrap method in AMOS 24.0 to examine the mediating effects. The direct effect represents the immediate influence of the independent variable on the dependent variable, indicated by the path coefficient. The mediating effect reflects the influence transmitted through the mediating variable—in this case, the enterprise’s technological innovation behavior. The magnitude of the mediating effect is calculated as the product of the relevant path coefficients.

The bootstrap estimation method was applied to assess the mediating effects, using both bias-corrected and percentile confidence intervals. A mediating effect is considered significant if the 95% confidence interval does not include zero. As shown in the table, the total, direct, and indirect effects do not contain zero within the 95% confidence intervals for both estimation methods. This indicates that all effects are statistically significant, supporting the validity of the hypothesis. The specific situation is shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Table of Bootstrap mediation effect test results.

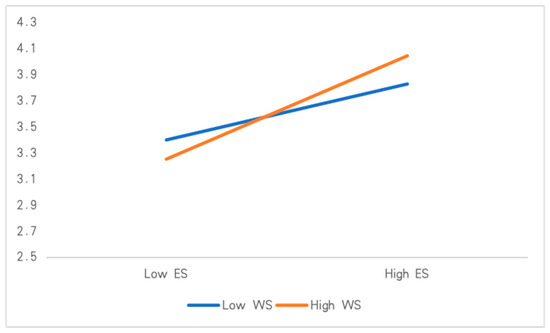

4.7. Moderating Effects

Following the mediation analysis procedure proposed by Zhao et al. [25], this study employs Model 1 from PROCESS 4.0 in SPSS to test for moderating effects. As shown in the table, the interaction term between elevated sense of style (ESS) and upward social comparison (US) has a significant positive impact on willingness of users to purchase (WUP). This indicates that upward social comparison positively moderates the relationship between an elevated sense of style and users’ willingness to purchase improved housing, thereby supporting the proposed hypothesis. The specific situation is shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Moderated effects test results table.

To further investigate the moderating role of upward social comparison, the variable was divided into high and low groups based on one standard deviation above and below the mean. A simple slope analysis was then conducted to explore how upward social comparison moderates the relationship between an elevated sense of style and users’ willingness to purchase improved housing. As illustrated in the figure, when upward social comparison is low, an elevated sense of style shows a weaker positive effect on purchase willingness (p < 0.001); conversely, at high levels of upward social comparison, this positive effect is stronger (p = 0.005 < 0.05). This indicates that a heightened sense of style more strongly promotes users’ willingness to purchase when upward social comparison is greater. The moderating effect is depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Moderating effect diagram.

5. Analysis and Discussion

5.1. Direct Effects Analysis

The results of this study show that in the millennial cohort, display design identification sense and facility service satisfaction have a positive contribution to the willingness of users to purchase for improved housing, where art display identification sense and design philosophy identification sense have a non-significant positive effect on willingness of users to purchase for improved housing, facility provision The positive effects of art display identification sense and design philosophy identification sense on willingness of users to purchase for improved housing are not significant, while facility provision satisfaction and service provision satisfaction have significant positive effects on willingness of users to purchase for improved housing. This finding is consistent with current consumer demand for higher standards of improved housing. Specifically, consumers’ recognition of improved housing does not stop at a single aesthetic level, but pays more attention to the overall living experience, and facility service satisfaction is more important in influencing willingness to purchase.

Although art display identification sense and design philosophy identification sense are theoretically expected to evoke consumers’ aesthetic resonance and emotional connection, the results of this study indicate that their direct effects on willingness to purchase improved housing are not statistically significant. This finding suggests that we must move beyond the intuitive assumption—commonly found in prior research—that “the more aesthetically pleasing the design, the stronger the purchase intention”. Instead, a more cautious reflection on the underlying psychological mechanisms and contextual realities is necessary. First, the influence of aesthetic factors may be more salient during the initial attraction phase rather than in the final decision-making process. As Vuković [79] notes, although millennials value aesthetic style in housing selection, their ultimate decisions—especially in high-cost, high-commitment contexts—are more heavily influenced by functionality, practicality, and everyday convenience. The positive emotions evoked by aesthetic design may not readily translate into behavioral intentions, particularly when such design lacks relevance to day-to-day needs. Second, the current housing market is marked by widespread “aesthetic homogenization”, where residential aesthetics have become overly standardized and commercialized. As a result, consumers may experience aesthetic fatigue and difficulty distinguishing among similar design features. Rather than conveying a sense of uniqueness, these design elements are increasingly perceived as marketing tools, weakening their emotional impact. In contrast, satisfaction with facility provision and service provision, which are closely tied to practical daily life, appears to exert a more direct and significant influence on actual purchase behavior.

Facility provision satisfaction and service provision satisfaction have a significant positive effect on the willingness of users to purchase for improved housing, reflecting the fact that homebuyers are more This reflects that homebuyers are more focused on overall quality of life and convenience when choosing a home, especially among the millennial generation. First, as Internet natives, Millennials have unique cultural backgrounds and needs in terms of information access and lifestyles. Heriyati et al. point out that although homebuyers’ decisions are traditionally influenced by factors such as personal financial status, home price levels, and the market environment, the guiding effects of social media and online culture should not be ignored [80]. As digital natives, millennials are more likely to pay attention to the social and cultural atmosphere of the neighborhoods where they live and whether they have good information interaction channels when purchasing a home, a preference that has not been emphasized enough in previous studies. Against this background, the significant positive effects of facility provision satisfaction and service provision satisfaction on the willingness of users to purchase improved housing are further emphasized. Millennials generally pursue a convenient and efficient lifestyle, and they are accustomed to obtaining information and services through the Internet. Therefore, improved amenities and services directly enhance their living convenience, and efficient property management and intelligent community facilities can meet their expectations of technology and make the living experience smoother. Secondly, Millennials’ expectations of the living environment often reflect their life philosophy. Many in this group tend to prefer homes that offer social interaction and lifestyle enhancement. Green and recreational amenities within a community can provide a space to relax and socialize, helping to ease their high-pressure work and life rhythms. The focus on quality of life in the community further enhances the positive impact of amenities and services on willingness to purchase. Finally, Millennial homebuyers value the actual functionality and convenience of amenities more than artistry in design. Practical features that enhance the quality of life and living experience are often more attractive in their home-buying decisions. Thus, the significant positive impacts of facility provision satisfaction and service provision satisfaction highlight the importance that millennials place on the quality of the comprehensive services of improved housing, suggesting that functionality and utility are always important in the home-buying process. This is also consistent with the findings of Mulyano et al. [81] In their survey of millennials’ housing preferences in Jakarta, the authors found that the completeness and practical functionality of amenities are key factors that urban homebuyers prioritize in their fast-paced lives, and that residential communities with good amenities are more likely to be preferred by young consumers, especially those that support healthy lifestyles and provide shared spaces and smart service systems. This echoes the millennials’ emphasis on residential convenience and reveals the complex interaction between generational characteristics and residential preferences.

Moreover, it is important to acknowledge that this study does not fully account for other critical factors that may influence housing purchase decisions—factors that extend beyond the aesthetic and service environment. In particular, socioeconomic constraints, policy-related influences, and risk perception can significantly shape consumer behavior, especially in high-stakes, high-cost decisions such as purchasing improved housing. For instance, income level, credit access, and employment stability may serve as structural barriers or enablers that mediate the relationship between individual preferences and actual purchase behavior. Even when consumers show high aesthetic or service satisfaction, constrained financial resources may override positive attitudes and reduce the likelihood of action. Similarly, government policies—such as mortgage interest subsidies, purchase restrictions, or housing taxation—can critically shape market expectations and shift buyer priorities, particularly in urban China’s highly regulated housing environment. In addition, risk perception, including concerns about real estate market volatility, housing bubble speculation, or long-term asset depreciation, may deter potential buyers regardless of the attractiveness of the housing product itself. These factors may be particularly salient for millennial consumers, who often navigate uncertain financial futures and rapidly shifting housing policies.

Future research should therefore consider incorporating these variables into an expanded, cross-culturally validated model to better capture the full complexity of improved housing purchase behavior across diverse markets. Doing so would allow for a more holistic and internationally relevant understanding of how external structural conditions—such as housing policies, economic volatility, or cultural norms specific to East Asian, European, or North American contexts—interact with internal psychological mechanisms, such as design identity and service satisfaction, to shape housing decisions. Examining these interactions in a comparative framework could reveal whether certain psychological mechanisms universally drive behavior or are mediated by regional factors, ultimately contributing to a more globalized theory of residential consumption.

5.2. Analysis of Mediating Effects

This study investigated the mediating role of an elevated sense of style and found that “elevated sense of style” played a significant role in mediating the relationship between display design identity and willingness of users to purchase for improved housing, as well as between facility service satisfaction and willingness of users to purchase for improved housing. The study found that an “elevated sense of style” played a significant mediating role between display design identity and willingness of users to purchase for improved housing, as well as between facility service satisfaction and willingness of users to purchase for improved housing. This finding reveals a neglected psychological pathway in residential consumer decision-making, i.e., consumers do not make judgments based on functional rationality alone but rather generate a symbolic sense of self-identity in the process of perceiving the residential environment.

From the perspective of psychological mechanisms, the mediation process is a “cognition-emotion-behavior” chain with symbolic consumer motivation as the core driving force. Elevated sense of style, as a symbolic dimension of perceived value, not only reflects consumers’ aesthetic perception of product design and service environment but also evokes their psychological projection of self-realization and ideal life picture. As a symbolic dimension of perceived value, an elevated sense of style not only reflects consumers’ aesthetic perception of product design and service environment but also evokes their psychological projection of self-realization and ideal life. In the consumption scenario of improved housing, consumers are often not satisfied with functional satisfaction but rather expect the aesthetic and identity symbols conveyed by the housing space to resonate with their “ideal me” [82]. This mediating pathway can be interpreted as a symbolic interaction mechanism, whereby consumers gain an intrinsic sense of style and taste through the residential design language and amenity experience, which reinforces their lifestyle self-efficacy and motivates purchasing behavior. This path extends the symbolic value dimension of perceived value theory [83], and echoes lifestyle fit theory [84] about the importance of matching a product with one’s ideal image.

Compared to existing studies, the theoretical contribution of this research lies in the further refinement of the mediating mechanism and offers an important cross-cultural perspective in the international academic dialogue. While studies such as Cetintahra et al. have confirmed the positive impact of residential aesthetics on consumers’ emotional connection, they did not conceptualize “sense of acquisitive feeling” as an independent variable, thus lacking an in-depth exploration of the mechanism through which aesthetic perception translates into identity construction [85]. On the other hand, research by Park et al. focused on the relationship between service quality and satisfaction but overlooked the symbolic psychological transformation triggered by situational aesthetics [86]. Building on this, our study proposes that “sense of acquisitive feeling” is not merely an emotional response but also part of the consumer’s cultural identity construction, reflecting the profound influence of cultural capital on consumption preferences as highlighted in Bourdieu’s theory of distinction.

It is noteworthy that this finding extends the current Western-centric understanding of markets by revealing how cultural context shapes housing consumption motivations. In East Asian markets emphasizing collectivism and social hierarchy (e.g., China, South Korea), a housing unit’s “acquisitive feeling” tends to be interpreted more as a symbol of family social status and achievement, closely associated with maintaining social identity. In contrast, in Western societies that prioritize individualism and self-expression (e.g., the United States and Western Europe), residential aesthetics may be more closely linked to the expression of personalized lifestyles and independent aesthetic taste, rather than directly correlating with upward social mobility. Therefore, the mediating variable “sense of acquisitive feeling” proposed in this study not only provides more precise theoretical support for branding and spatial design in the high-end residential market but also underscores the necessity for localized marketing strategies within a globalized context. Future research could build on this foundation to conduct systematic cross-cultural comparisons to further validate and refine this theoretical framework.

5.3. Analysis of Moderating Effects

This study further explored the moderating role of upward social comparison in the relationship between an elevated sense of style and the willingness of users to purchase for improved housing. It was found that upward social comparison had a significant positive moderating effect on the relationship, i.e., as individuals’ tendency to make upward comparisons increased, the driving effect of an elevated sense of style on willingness to purchase also increased. This result suggests that for Millennials, who are highly concerned with self-actualization and social identity, the living style conveyed by residential space is not only an aesthetic experience, but also an important means of achieving upward mobility and taste manifestation.

According to social comparison theory, when individuals are in a social reference system, especially when they are faced with symbolic consumer goods, they often evaluate their own position and potential identity value by comparing themselves to higher status groups. Millennials have a stronger sense of upward comparison due to their long-term exposure to social media environments, and tend to self-express and construct their identities through their consumption behaviors. In this study, when these consumers perceive a symbolic meaning of style enhancement through the display design and amenities of a home, the tendency of upward comparisons prompts them to interpret this perception as an opportunity and a channel to get closer to their ideal selves, which significantly enhances their willingness to purchase. In addition, the significance of the moderating effect confirms that the consumption of Millennials is typically characterized by lifestyle symbolization. Lifestyle symbolization. They regard their homes not only as a place to live, but also as a platform for social display and a materialized presentation of their aesthetics and values. Therefore, when “elevated sense of style” stimulates their lifestyle imagination, consumers with an upward comparison tendency are more likely to view improved housing as a symbolic medium for moving into a higher social status, and thus generate stronger purchase motivation.