Reconstruction of the Batayizi Church in Shanxi: Based on the Construction of Italian Gothic Churches in the Context of Chinese Form and Order

Abstract

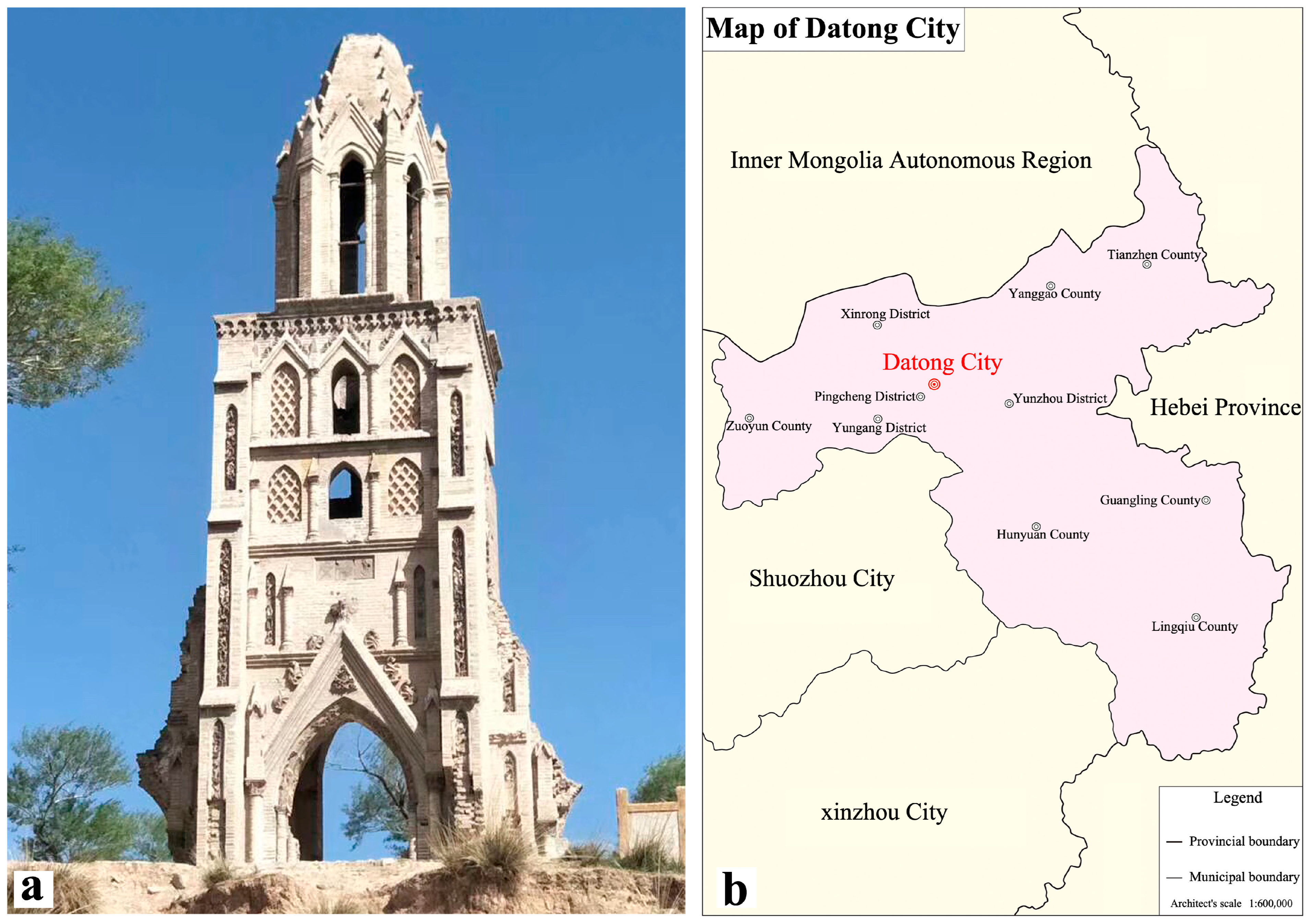

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Local gazetteers and religious histories, which document the spread of Catholicism and church construction in Shanxi, especially image archives from the church itself, provide crucial evidence for restoring the main façade [5];

- (2)

- The historical development of Catholic churches, which explores their evolution and regional characteristics, offers a broader perspective for this study [6];

- (3)

- The study of ruin aesthetics, which focuses on the artistic value of the church, serves as a key reference for analyzing its brick carvings [7].

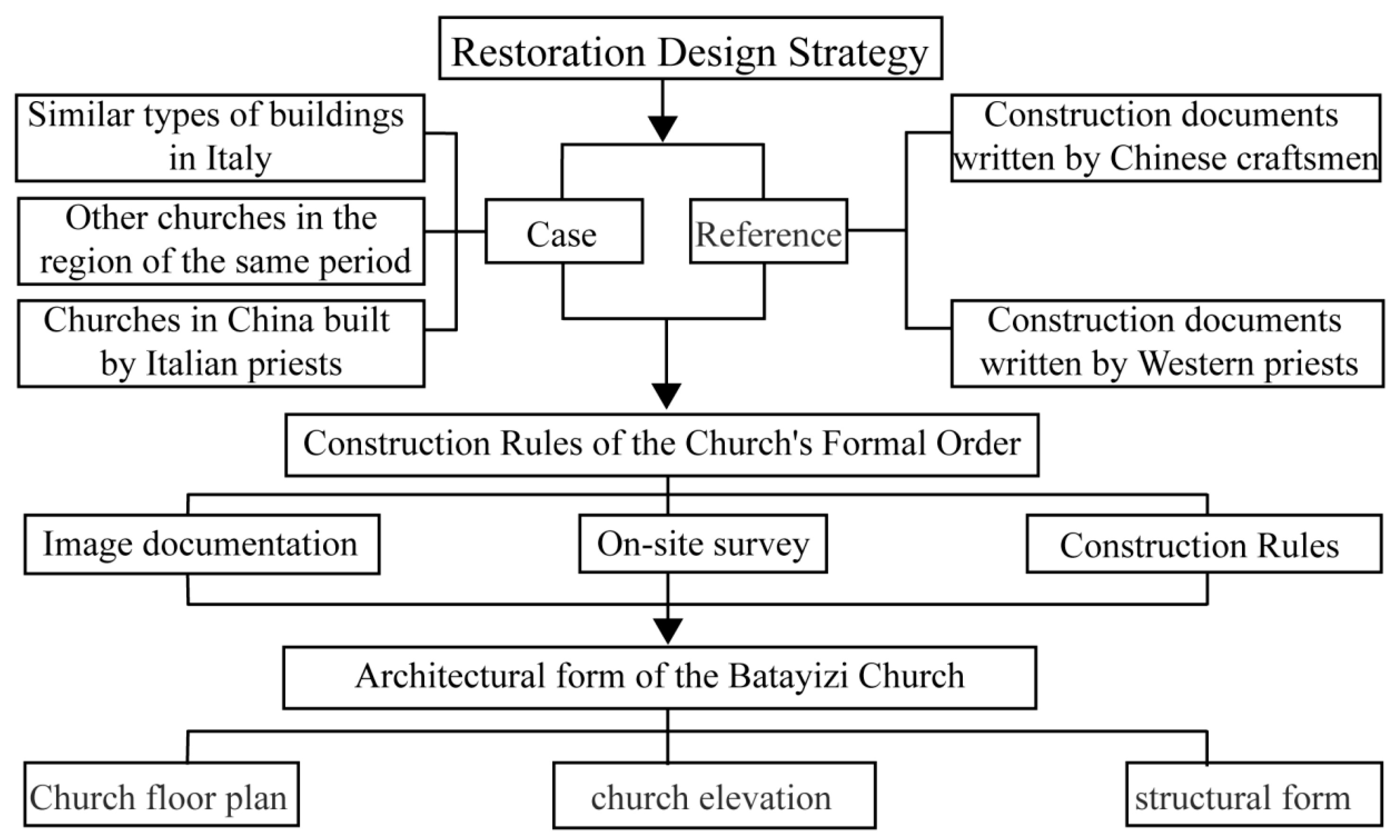

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Technical Approach

2.2. Design Rules of Form and Order

| Category | Name | Floor Plan | Main Facade | Structure and Materials |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gothic Churches in Italy [12] | Orvieto Cathedral (1290–1591) | Latin Cross Plan, East–West Orientation | Decorative Gothic style, three-part composition | Brick-wood hybrid structure, wooden truss roof, wall arches as support; main body brick masonry, stone carvings as decoration |

| Siena Cathedral (1136–1382) | Latin Cross Plan, East–West Orientation | Decorative Gothic style, three-part composition, separation of decoration and structure | Stone masonry structure, partially brick-built, covered with marble; main body stone masonry, stone carvings as decoration | |

| Milan Cathedral [13] (1386–1500) | Latin Cross Plan, East–West Orientation | Fusion of Gothic and local styles, dense spires, intricate sculptures, strong verticality | Crossed vaults and barrel vaults combined, dry-stone bearing walls, covered with marble; main body stone masonry, stone carvings as decoration | |

| Santa Croce Church (1248–1294) | Latin Cross Plan, East–West Orientation | Gothic decoration emphasizing pointed arches, arcades, and window adornments | Brick masonry structure, without flying buttresses, unique spatial organization; main body brick masonry, stone carvings as decoration | |

| Gothic Churches Built by Foreign Missionaries in China [14] | Xizhimen Catholic Church (1723–1912) | Basilica style, north–south orientation | Three-part composition, bell tower integrated with the facade, details incorporating Chinese elements | Brick-wood hybrid structure, brick walls with wooden columns, wooden truss roof, interior wooden vaulted ceiling in a Gothic style; main body brick masonry, decorative floral tiles |

| Xishiku Catholic Church (1703–1887) | Latin cross style, north–south orientation | Three-part composition, symmetrical arrangement centered on the bell tower, blending Chinese and Western decorations | Brick-wood hybrid structure, brick walls with brick columns, wooden truss roof, interior wooden vaulted ceiling in a Gothic style; main body brick masonry, decorative floral tiles | |

| Dongjiaominxiang Catholic Church (1901–1904) | Basilica style, north–south orientation | Three-part composition, symmetrical arrangement centered on the bell tower, blending Chinese and Western decorations | Brick arch-column system, central hall and side aisles with brick-built eight-ribbed pointed arch vaults; main body brick masonry, decorative floral tiles | |

| Hebei Daming Catholic Church (1917–1920) | Latin cross style, north–south orientation | Three-part composition, symmetrical arrangement centered on the bell tower, blending Chinese and Western decorations | Brick-wood hybrid structure, brick walls with brick columns, wooden truss roof, interior wooden vaulted ceiling in a Gothic style; main body brick masonry, decorative floral tiles | |

| Other Churches in Shanxi Region from the Same Period [15] | Xiyulin Catholic Church in Datong (1903) | Basilica style, east–west orientation | Three-part composition, bell tower symmetrically arranged in the center, Gothic style | Brick-wood hybrid structure, brick walls with brick columns, wooden truss roof; main body brick masonry, decorative floral tiles |

| Xin’anzhuang Catholic Church in Shuozhou (1913) | Basilica style, north–south orientation | Three-part composition, bell tower symmetrically arranged in the center, Gothic style | Brick-wood hybrid structure, brick walls with brick columns, wooden truss roof, interior wooden vaulted ceiling in a Gothic style; main body brick masonry, decorative floral tiles | |

| Guyang Town Catholic Church (1924) | Basilica style, east–west orientation | Three-part composition, bell tower symmetrically arranged in the center, blending Gothic and Romanesque styles | Brick-wood hybrid structure, brick walls with stone columns, wooden truss roof; main body brick masonry, decorative floral tiles | |

| Qingtang Catholic Church in Lin County (1912–1916) | Latin cross style, north–south orientation | Three-part composition, bell tower symmetrically arranged in the center, blending Chinese and Western decorations | Brick-wood hybrid structure, brick walls with brick columns, wooden truss roof, interior wooden vaulted ceiling in a Gothic style; main body brick masonry, decorative floral tiles |

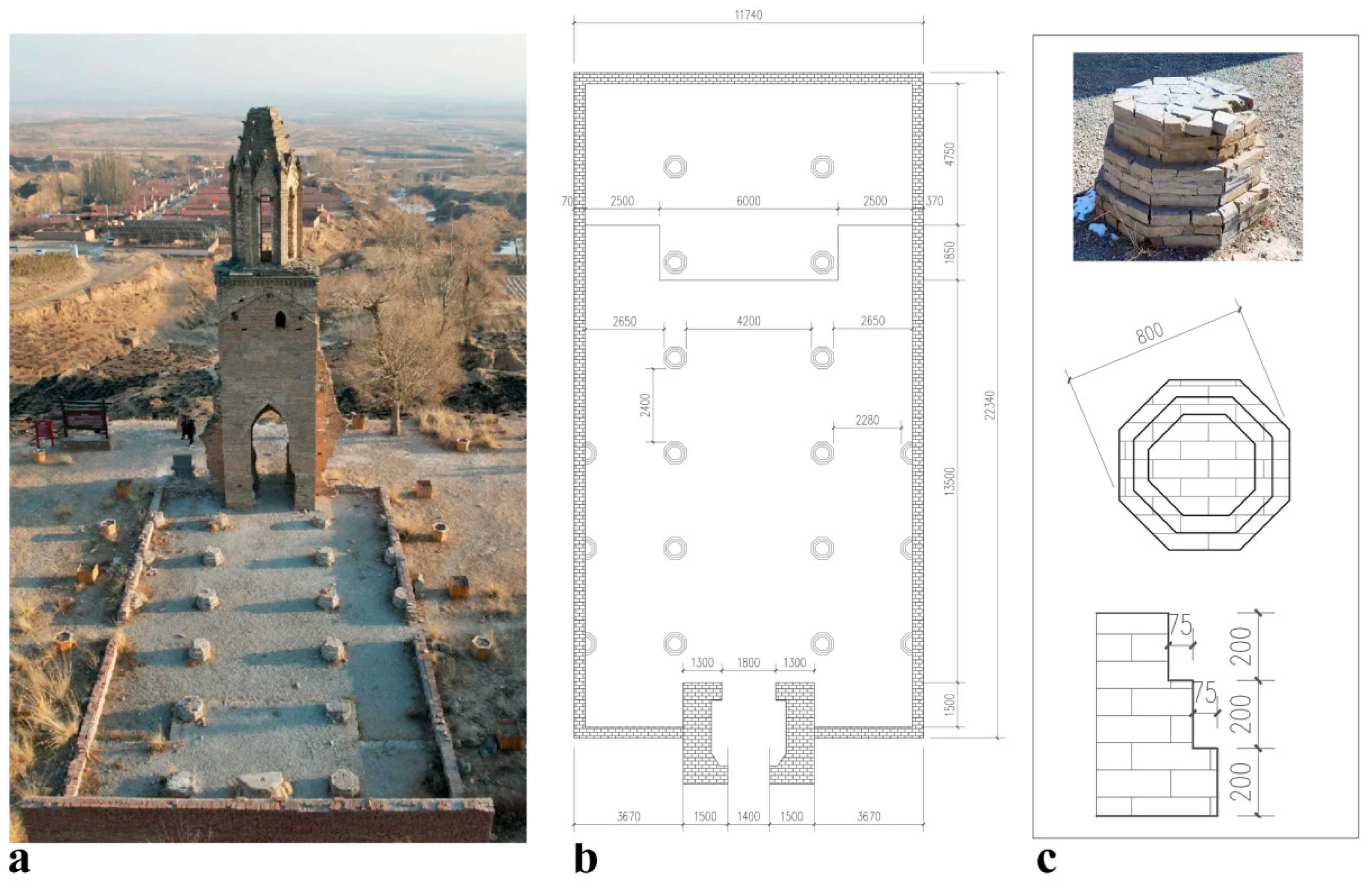

2.3. On-Site Survey

3. Results

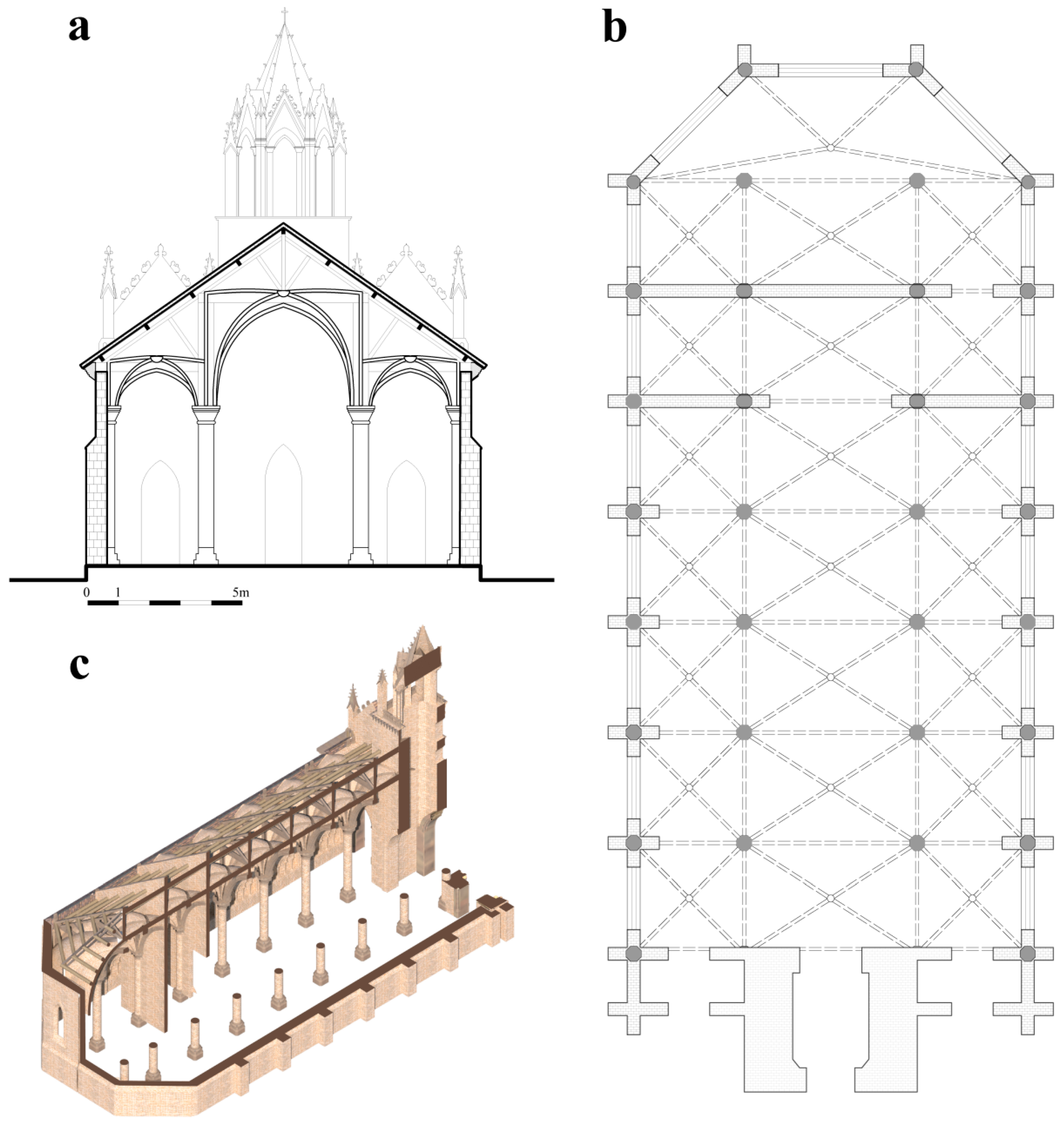

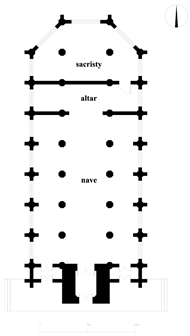

3.1. Reconstruction of the Church Floor Plan

3.2. Reconstruction of the Church Main Facade

- (1)

- The ground floor features three pointed arch portals formed by three layers of pointed arches progressively receding; the arches are overlaid with vegetal brick carvings that conceal the original structural details. During construction, the pointed arches of the portals were built with plank arches, primarily supporting part of the wall load transferred to the doors.

- (2)

- The second floor serves as the visual center of the facade. Due to local technical limitations, no rose window was installed at the center; instead, a “Holy Mother Church” plaque was placed. The gable walls are adorned with two pointed arch blind windows, mimicking the style of Gothic pointed arch windows. The second floor is capped with an eave, below which brick corbels form a cross-shaped cornice decoration.

- (3)

- The third floor consists of the gable spire and pointed arch windows of the bell tower. The triangular spire is outlined with layered string courses, visually enhancing the facade’s depth; below, beam-supported eave boards bear the spire’s load, decorated with blind arcades to emphasize the facade’s layering.

- (4)

- The fourth floor features the bell tower’s spire. The square base corners are chamfered to form a hexagonal plan; after base preparation, bricks matching the spire’s slope were used to construct the spire. Finally, acanthus leaf brick carvings were used to conceal the joints at the spire’s ridge.

- (1)

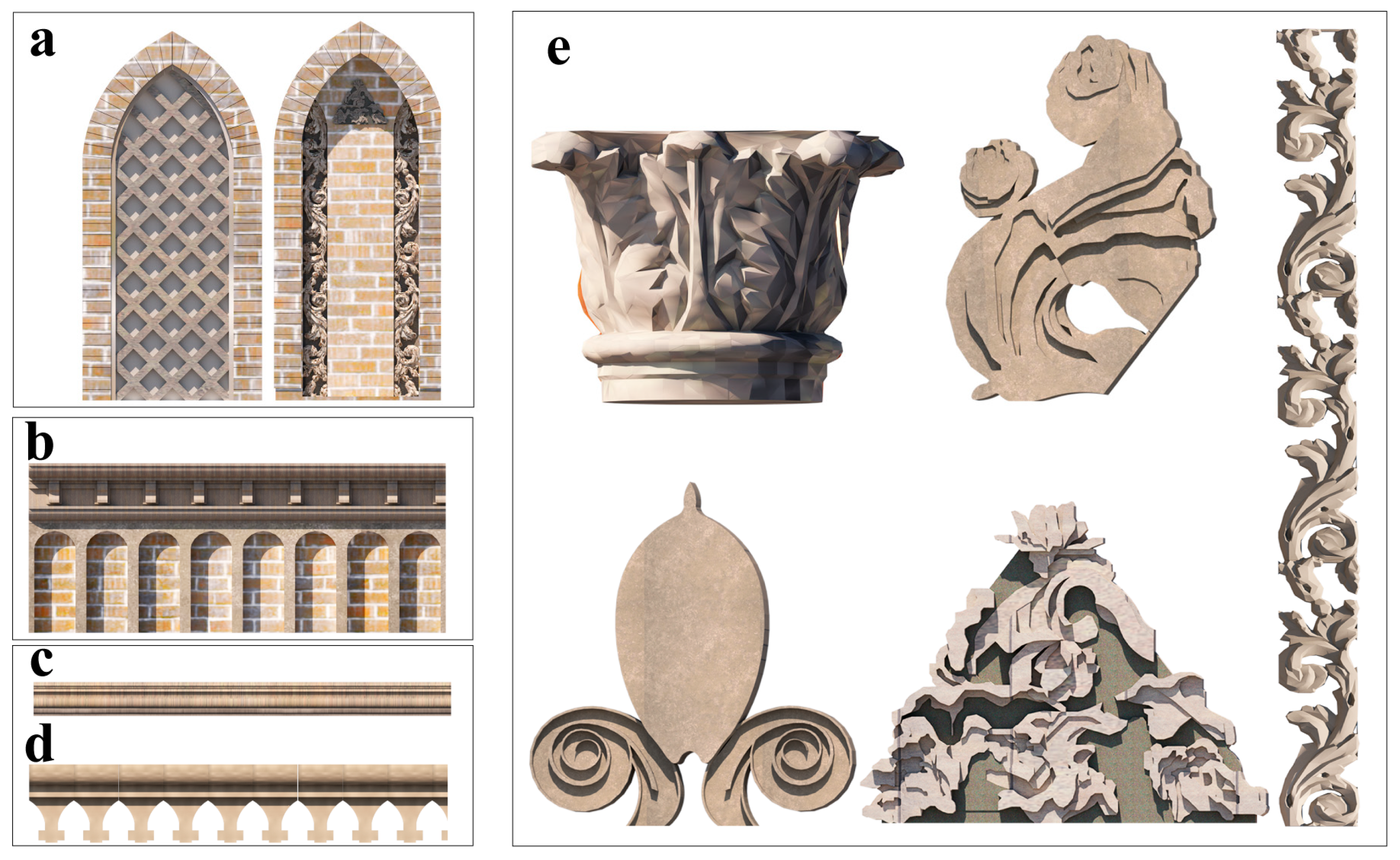

- Due to structural constraints, large windows could not be opened on the Batayizi Church facade; therefore, numerous blind windows were used to enhance the decorative effect (Figure 10a).

- (2)

- The beam-supported eave boards are the main components supporting the triangular spire of the gable wall, and their surfaces are decorated with blind arcades (Figure 10b). This decorative technique both weakens the vertical emphasis of the facade and reduces the heaviness of the wall.

- (3)

- There are two types of string courses on Batayizi Church. Wall string courses (Figure 10c) are located at junctions of different materials, geometric transitions, and decorative component connections, formed by specially shaped curved bricks creating a simple texture transition to the wall surface. The eave string course is cross-shaped (Figure 10d), composed of small bricks added above and below the horizontal bricks. Commonly found at roof-to-wall junctions, it serves as facade decoration and protects the wall from rainwater erosion.

- (4)

- The acanthus leaf motifs are vegetal decorative bricks. There are five types of acanthus leaf bricks on the facade (Figure 10e). Craftsmen depicted the plant characteristics with great precision, and this naturalistic approach makes the decorative bricks more realistic and lifelike.

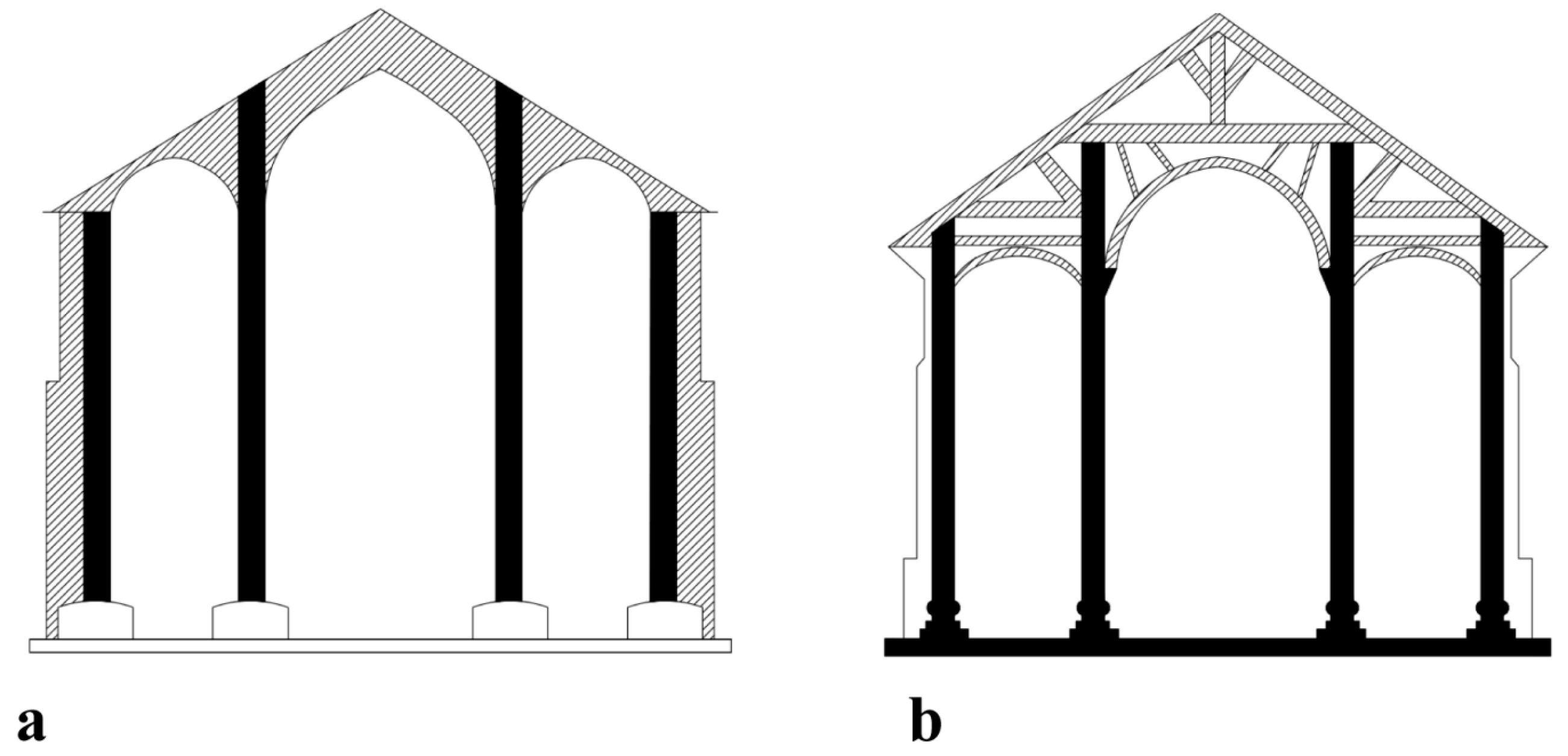

3.3. Reconstructionof Church Structure

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arrington, A. Recasting the Image: Celso Costantini and the Role of Sacred Art and Architecture in the Indigenization of the Chinese Catholic Church, 1922–1933. Missiology Int. Rev. 2013, 41, 438–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, G.; Xue, C.Q.L. China’s architectural aid: Exporting a transformational modernism. Habitat Int. 2015, 47, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L. Alternative Modernity, Rural Rediscovery and What Next: The Ongoing Debate on the Modern in China. Archit. Des. 2018, 88, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Gao, S. Translators and gospelers: The roles of western missionaries in China during the late Ming and early Qing Dynasties from the perspective of cultural capital. Asian J. Soc. Sci. 2025, 53, 100201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. A chronology of the field of modern Chinese architectural history, 1986–2012. Front. Archit. Res. 2013, 2, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Coomans, T. East Meets West on the Construction Site. Churches in China, 1840s–1930s. Int. J. Soc. Constr. Hist. 2018, 33, 63–84. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Cervesato, A.; Antiga, T.; Proca, E. Architectural Experimentations: New Meanings for Ancient Ruins. Architecture 2024, 4, 639–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coomans, T. A pragmatic approach to church construction in Northern China at the time of Christian inculturation: The handbook “Le missionnaire constructeur”, 1926. Front. Archit. Res. 2014, 3, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Huang, H.; Yan, Z.; Zhou, Q. Historical study and strategies for the revitalization of the former Ginling College buildings in Nanjing, China—Architectural Heritage of the Church School in the Early Twentieth Century. J. Archit. Conserv. 2024, 30, 169–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas Coomans, X.Y. Building Churches in Northern China: A 1926 Handbook in Context; Intellectual Property Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, D.X. Research of Technical and Construction on Pre-Modern Catholic Church in Shanxi Province. Master’s Thesis, Taiyuan University of Technology, Taiyuan, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lluís i Ginovart, J.; Samper, A.; Herrera, B.; Costa, A.; Coll, S. Geometry of the Icosikaidigon in Orvieto Cathedral. Nexus Netw. J. 2016, 18, 419–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, C.; Ruccolo, A.; Canali, F. Long-term monitoring for the condition-based structural maintenance of the Milan Cathedral. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 228, 117101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.L. The Tentative Research on the Four Catholic Churches in Beijing. Master’s Thesis, Beijing University of Civil Engineering and Architecture, Beijing, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J. Modern Catholic Churches in North Shanxi. Master’s Thesis, Taiyuan University of Technology, Taiyuan, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y. Architectural technology in modern China from a global view. Front. Archit. Res. 2014, 3, 79–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cuadros-Rojas, E.; Saloustros, S.; Tarque, N.; Pelà, L. Photogrammetry-aided numerical seismic assessment of historical structures composed of adobe, stone and brick masonry. Application to the San Juan Bautista Church built on the Inca temple of Huaytará, Peru. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 158, 107984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coomans, T.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, J. “Imposing and provocative”: The design, style, construction and significance of Saint Anthony’s Cathedral, Xinjiang (Shanxi, China), 1936–1940. In History of Construction Cultures; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021; pp. 85–92. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Z.; Huang, L.; Mao, Y.; Mustafa, M.; Mohd Isa, M.H. Navigating complexity in sustainable conservation: A multi-criteria decision making of architectural heritage in urbanizing China. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 102, 111906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Chen, M.; Yang, K.; Zhou, Q. Heritage Characterisation and Preservation Strategies for the Original Shantung Christian University Union Medical College (Jinan)—A Case of Modern Mission Hospital Heritage in China. Buildings 2025, 15, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachakis, G.; O’Hearne, N.; Mendes, N.; Lourenço, P.B. Seismic assessment of metallic neo-gothic church: Deterioration and safety of early structural design. Structures 2022, 36, 330–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demissie, T.E.; Italemahu, T.Z. Local heritage conservation practices and challenges in Ethiopia: Evidences from the ancient rock-hewn churches in Lay Gayint District, South Gondar, Amhara region. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2024, 10, 101139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, X.; Jiang, Q.; Zhou, Q. Historical Study and Conservation Strategies of “Tianzihao” Colony (Nanjing, China)—Architectural Heritage of the French Catholic Missions in the Late 19th Century. Buildings 2021, 11, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Campbell, J.W.P. Building the First Christian Church for the Shanghai Expatriate Community: Trinity Church, 1847–1862. Archit. Hist. 2023, 66, 185–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Campbell, J.W.P. A Model Church for a Model Settlement: The Construction of the Trinity Church in Shanghai 1863–1869. Constr. Hist. 2023, 38, 103–130. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Zhou, X.; Weng, F.; Ding, F.; Yi, Z. Acculturation and translation: Modern architectural heritage of Zhongshan Park in Xiamen from typological perspective. Front. Archit. Res. 2024, 13, 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Geng, X.; Zhang, Z.; Jia, C.; Fukuda, H. Correlation research on visual behavior and cognition of impression against localized church facades in China. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, S.; Fan, X. Copysites / duplitectures as tourist attractions: An exploratory study on experiences of Chinese tourists at replicas of foreign architectural landmarks in China. Tour. Manag. 2020, 81, 104179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, C.X.; Cantisani, E.; Fratini, F.; Rasmussen, K.L.; Rovero, L.; Stipo, G.; Vettori, S. China’s brick history and conservation: Laboratory results of Shanghai samples from 19th to 20th century. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 151, 789–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Xia, Q.; Shi, F. Nondestructive inspection of a brick–timber structure in a modern architectural heritage building: Lecture hall of the Anyuan Miners’ Club, China. Front. Archit. Res. 2019, 8, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Yang, D.; Cui, Y.; Tang, Z.; Bai, J. Research on the Construction of Sino-Western Fusion Catholic Churches in China: A Case Study of a Catholic Church in Anqing. Buildings 2025, 15, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberdi, E.; Galindo, M.; León-Rodríguez, A.L.; León, J. Acoustics in Baroque Catholic Church Spaces. Acoustics 2024, 6, 911–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Time | Resident Priest | Church Status | Affiliated Diocese/Religious Order |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1868 | Father Fugela (Italy) | None | Taiyuan Diocese/Italian Franciscan Order |

| 1876 | Father Saint Laurence (China) | Initial Construction | |

| 1900 | Father Saint Laurence (China) | Demolished | |

| 1914 | Father Bai (Italy) | Reconstruction | |

| 1926–1942 | Father Wu (Germany), Father De (Unknown), Father Wang Nai (Unknown), Father Cai (Unknown), Father Li (Unknown), Father Suside (Germany) | Abandoned | Shuoxian Diocese/German Franciscan Order |

| 1942–1993 | None | The church was demolished, leaving only the bell tower | None |

| 2000–2010 | Father Niu (China) | Excavated | Datong Diocese/Belgian Congregation of the Immaculate Heart of Mary |

| 2010–Present | Father Pan (China) |

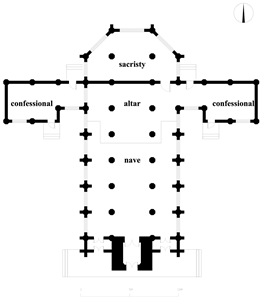

| Reconstruction Scheme | Floor Plan Diagram | Altar Partition Wall | Confessional |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scheme 1: Basilica-style Floor Plan |  | Yes | Integrated with the altar |

| Scheme 2: Latin Cross Floor Plan |  | No | Independently arranged |

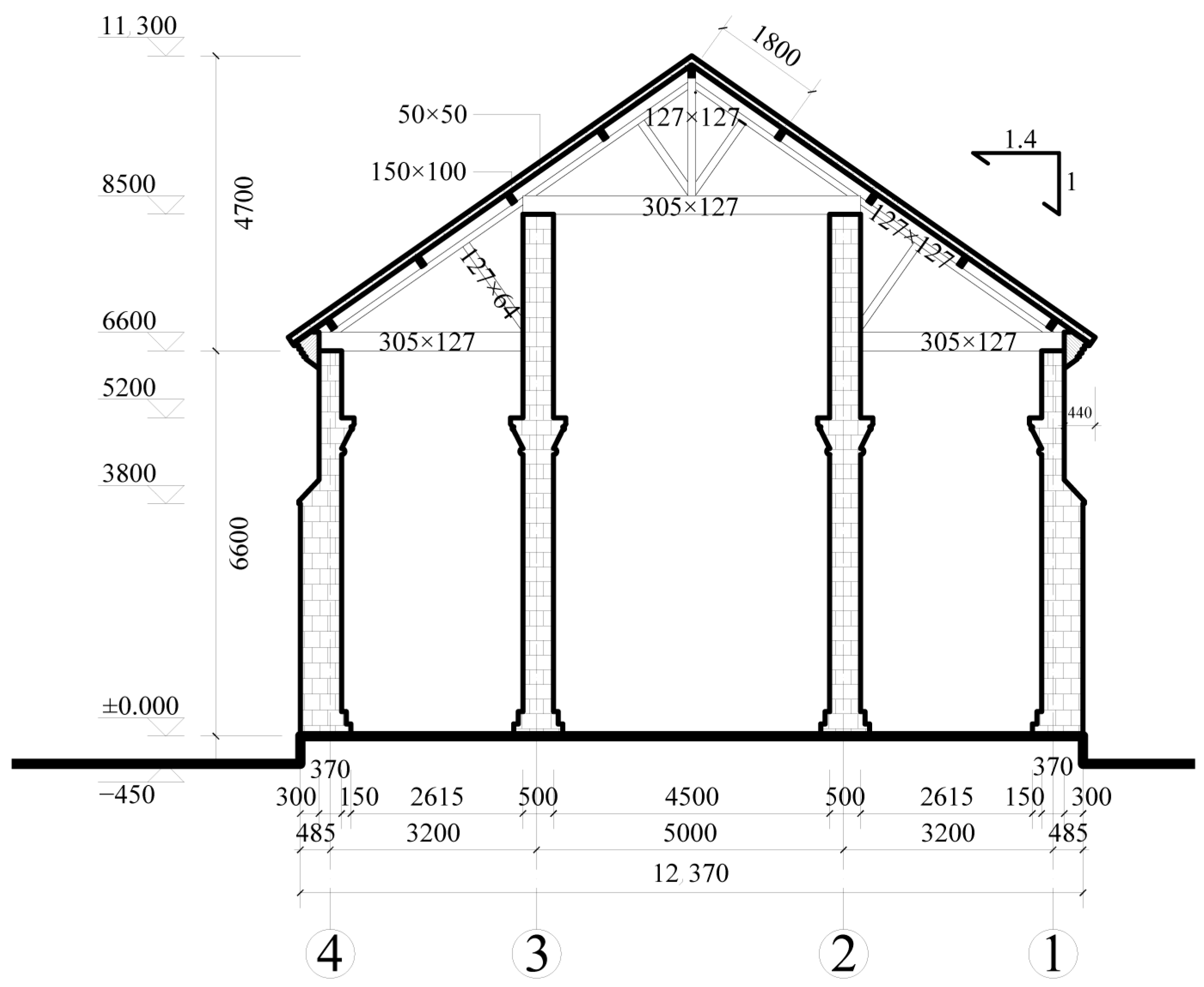

| Location | Building Structure | Manual | New Construction Methods | Cross-Sectional Dimensions (Thickness × Width) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper diagonal timber of truss | Upper chord | Principal rafter | Main brace | 127 mm × 127 mm |

| Lower diagonal timber of truss | Lower chord | Beam | Tie beam | 305 mm × 127 mm |

| Longest vertical post of the truss | Central vertical post | Central column | Main upright post | 127 mm × 127 mm |

| Diagonal brace in the truss | Diagonal support | Diagonal support | Secondary brace | 127 mm × 64 mm |

| Vertical post in the truss | Web member | Small strut | Upright post | 125 mm × 125 mm |

| Longitudinal and transverse connections between trusses | Purlin | Purlin | Purlin | 150 mm × 100 mm |

| Ridge purlin | Ridge beam | 150 mm × 100 mm | ||

| Lath on purlin | Rafter | Rafter | Rafter | 50 mm × 50 mm |

| Overhanging eaves | Flying rafter | 1/15 × wall height | ||

| To prevent purlins from slipping | Purlin support | Purlin support | ||

| To support the bottom of rafters | Earth purlin | Earth purlin | Sleepers | 150 mm × 100 mm |

| To support beams and the roof | Principal rafter | Principal rafter | Rafter | 50 mm × 50 mm |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tan, Y.; Ying, Z.; Lin, H.; Zhang, C.; Bao, W.; Chen, H. Reconstruction of the Batayizi Church in Shanxi: Based on the Construction of Italian Gothic Churches in the Context of Chinese Form and Order. Buildings 2025, 15, 3179. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15173179

Tan Y, Ying Z, Lin H, Zhang C, Bao W, Chen H. Reconstruction of the Batayizi Church in Shanxi: Based on the Construction of Italian Gothic Churches in the Context of Chinese Form and Order. Buildings. 2025; 15(17):3179. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15173179

Chicago/Turabian StyleTan, Yini, Ziyi Ying, Haizhuan Lin, Cuina Zhang, Wenhui Bao, and Hui Chen. 2025. "Reconstruction of the Batayizi Church in Shanxi: Based on the Construction of Italian Gothic Churches in the Context of Chinese Form and Order" Buildings 15, no. 17: 3179. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15173179

APA StyleTan, Y., Ying, Z., Lin, H., Zhang, C., Bao, W., & Chen, H. (2025). Reconstruction of the Batayizi Church in Shanxi: Based on the Construction of Italian Gothic Churches in the Context of Chinese Form and Order. Buildings, 15(17), 3179. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15173179