1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background and Aim

The phenomenon of urban-to-rural migration has attracted growing attention in both political and academic circles, with similar trends to be observed across various global contexts. It reflects a broader post-urbanization tendency in which many societies seek to address challenges such as depopulation, village decline, and rural revitalization through inward migration. From the perspective of urban residents, such migration is often driven by the pursuit of alternative lifestyles, ecological values, or economic opportunities. However, these movements frequently give rise to complex cultural and spatial tensions. This migration has reconfigured population geographies and initiated profound spatial transformations, reshaping land use patterns, housing forms, community structures, and architectural practices. While it presents new opportunities for rural revitalization, it also gives rise to a range of spatial and social challenges—such as the commodification of the rural landscape, sociocultural displacement of local communities, and growing tensions between in-migrants and local residents.

For instance, Italy’s 1-Euro House initiative aimed to repopulate shrinking villages by offering abandoned properties to in-migrants. While this policy stimulated economic revitalization and architectural restoration, it also led to population displacement, as many properties were transformed into short-term rentals, disrupting local social structures and weakening cultural continuity [

1]. Similarly, the North American “Back-to-the-Land” movement during the 1960s–1970s saw urban residents relocate to rural areas in search of simplicity, independent living, and ecological harmony. Although it fostered alternative communities and environmental awareness, it also gave rise to tensions between in-migrants and rural locals, particularly over land use and cultural identity [

2]. In Japan, the phenomenon of Den-en Kaiki—the migration of urban populations to depopulated rural areas—has been increasingly active in recent years. On the one hand, it has contributed to regional development [

3], but on the other hand, recent studies have also revealed governance conflicts and cultural frictions between migrants from urban areas and local residents, highlighting the complexity of such migration-led revitalization [

4]. These cases demonstrate that urban-to-rural migration has become a globally recognized intervention to address rural decline; yet, its outcomes are often ambivalent and contested.

In China, the urban-to-rural migration phenomenon has gained significant traction under the national rural revitalization strategy. The development and revitalization of rural areas have long been a significant objective of both China’s central and local government policies. To this end, a series of initiatives have been continuously implemented across multiple dimensions, including industry, environment, infrastructure, and population. Particularly since the beginning of the 21st century, initiatives promoting the modernization of rural settlements, the improvement of village livability and attractiveness, and the advancement of urban–rural integration have played an important role in improving rural infrastructure, rehabilitating residential and ecological environments, and strengthening rural economic and industrial aspects. In 2018, “Rural Revitalization” was formally established as a national development strategy. In economically developed regions such as Zhejiang, an increasing number of middle-class urban residents are relocating to rural villages, bringing with them financial capital, diverse lifestyles, and new spatial expectations. However, this influx has revealed deep-seated tensions between modern demands and the spatial logic of traditional rural settlements. Migrants often seek upgraded living environments featuring urban or hybrid aesthetics, multifunctional layouts, and enhanced amenities—preferences that frequently clash with the scale, structure, and socio-spatial norms of existing village architecture. These mismatches are apparent not only in functional or regulatory terms, but also in symbolic and experiential dimensions, manifesting as aesthetic discord, divergent rhythms of daily life, and ongoing negotiations over spatial adaptation.

Since the implementation of China’s 14th Five-Year Plan in 2021, the country has entered a phase characterized by multidirectional and overlapping patterns of population mobility [

5]. In parallel with this demographic transition, both central and local governments—particularly in Zhejiang province—have actively promoted urban-to-rural migration among younger urban populations as a strategy for stimulating rural development [

6,

7,

8,

9]. A new wave of urban-to-rural migrants is reshaping rural spatial configurations through architectural renovations and self-initiated spatial practices, leading to notable transformations in rural production, habitation, and ecological systems [

10]. The expansion of digital infrastructure in rural China has further integrated villages into broader economic and cultural networks, facilitating the growth of tourism and the emergence of new consumption patterns [

11]. On the one hand, this urban-to-rural migration trend has contributed to economic development, increased land values, and supported the conservation of traditional village architecture. On the other hand, it has also generated a range of challenges, including rising local prices, intensified competition for limited resources, and spatial overcrowding. In some cases, excessive commercialization has begun to compromise traditional rural lifestyles [

12]. These dynamics are already observable in Zhejiang, where the urban-to-rural migration phenomenon emerged earlier and has developed more rapidly than in most other regions.

Adopting a building-scale perspective, this study draws on cases from Zhejiang, China, to examine how urban-to-rural migrants shape the preservation and transformation of traditional values through their spatial and lifestyle interventions. Building on and moving beyond previous village-level analyses, it focuses on how migrants reshape vernacular spatial patterns and everyday life by adapting traditional dwellings to reflect their personal preferences. By examining both the protective and disruptive effects of these interventions, the research reveals their dual impact on traditional architectural forms and cultural practices. Although grounded in the Chinese context, the mechanisms identified are analytically transferable and offer broader insights into the transformation of traditional spatial values amid contemporary urban-to-rural migration. As part of the global post-urbanization trend, this study contributes new theoretical and empirical perspectives to discussions on rural revitalization, urban–rural integration, and rural heritage conservation.

To examine these dynamics, this research is guided by the following core question: How do urban-to-rural migrants’ spatial and lifestyle practices affect the preservation and transformation of traditional rural values, and can such migration serve as an effective strategy to address the development challenges faced by vernacular villages? Based on this question, the study proposes the following hypothesis: Urban-to-rural migrants embed urban aesthetics and resources into rural settings through their spatial and lifestyle practices, helping to address demographic decline and spur local development; however, differences in their understanding and respect for traditional values may inadvertently undermine vernacular cultural norms. As such, they constitute a key factor in the ongoing transformation of rural built environments and social relations.

1.2. Literature Review

At present, global research on urban-to-rural migration has primarily focused on policy, economic, and social development perspectives, but studies examining this phenomenon from the lens of micro-scale spatial practices and the preservation of traditional values remain largely absent. Previous research by Jin, Z. et al. conducted case studies in Zhejiang Province to examine the spatial impacts of urban-to-rural migration at the village scale, focusing on transformations in the overall spatial structure of rural settlements and offering insights into the morphological consequences of urban-to-rural migration in rural China [

13]. Building on that foundation, the present study shifts the analytical focus to the architectural scale, investigating how rural space is reconfigured at the level of individual buildings used or adapted by urban-to-rural migrants. In doing so, it seeks to deepen the understanding of spatial transformation processes associated with urban-to-rural migration from a finer-grained, everyday-life perspective. Additionally, existing studies have explored how urban-to-rural migrants engage with physical space, including interpersonal interactions within their dwellings, the adaptive reuse of vacant houses, and the appropriation and reinterpretation of residential spaces through creative activities [

14,

15,

16]. Moreover, scholars have pointed to the commodification of rural space as a broader spatial process accompanying migration [

17].

Across the globe, and particularly in Japan, spatial research on urban-to-rural migration has demonstrated diverse and evolving approaches. For instance, a research institution has investigated how the revitalization of vernacular crafts can serve as a means of reconstructing daily life environments in the so-called post-urban or return-to-pastoral era [

18]. In parallel, Katayama, K. and colleagues proposed the concept of Migration Promotion Housing, which targets de-urbanized populations and supports their resettlement in rural areas through tailored spatial interventions [

19]. Other scholars, such as Matsumoto, A., have analyzed the spatial determinants influencing lifestyle migrants’ decisions to settle in remote, non-urban regions [

20]. These inquiries suggest that spatial preferences and perceptions of distance play a critical role in shaping rural migration trajectories.

Beyond housing and location choices, the co-production of space between in-migrants and local residents has become a vital subject of study. From the perspective of the theory of social production of space, Zheng, N. et al. have investigated the challenges of integration faced by in-migrants in rural China and proposed spatial restructuring strategies to enhance social cohesion with the original residents [

21]. Similarly, Golding, S.A. et al. adopted the rural–urban gradient classification to examine how migrants to metropolitan fringe areas reshaped new forms of rural space together with local communities [

22]. These studies highlight how urban-to-rural migration entails more than individual relocation—it reshapes spatial practices and redefines communal spaces. Furthermore, Afrakhteh H. has shown how migrants contribute to transforming local spatial structures and catalyzing community development [

23], and Lopez, M.G. has analyzed the spatialization processes of migration, emphasizing the emergence of new spatial morphologies influenced by in-migration [

24].

In contrast, spatial research on urban-to-rural migration in China is still in its nascent stages. To date, research on rural architecture in China has primarily focused on the regional-specific characteristics of traditional dwellings and the construction of new village housing [

25,

26,

27,

28]. Meanwhile, studies on urban-to-rural migration have largely concentrated on themes such as rural revitalization, youth entrepreneurship, and village planning. However, there is limited research on the spatial characteristics of buildings in which urban-to-rural migrants reside or work [

29,

30,

31,

32]. One notable contribution is the work by Qi, W. et al., who examined the spatial patterns and driving forces of urban-to-rural migration in the Chinese context [

33]. Although limited in scope, their research highlights the importance of integrating spatial factors into broader rural development discourses. Moreover, while not explicitly framed within the urban-to-rural migration paradigm, several studies on Chinese rural housing typologies offer valuable insight. These include investigations into the spatial characteristics and vacancy problems of traditional village dwellings in Anhui Province [

34], and the spatial transformation and contemporary status of courtyard houses in rural Henan [

35]. Such works lay essential groundwork for analyzing how populations migrating into rural areas may interact with and reshape traditional spatial systems.

In addition to spatial aspects, behavioral dynamics among migrants have attracted growing scholarly interest. For example, Hu, Y. has explored how migrants influence intra-household dynamics and the fabric of everyday rural life [

36], while Nienaber, B. and colleagues have examined the processes of social integration and community acceptance experienced by in-migrants [

37]. Research by Azusa, I. has investigated migrants’ behavioral patterns and value systems, revealing how these migrants may alter established socio-cultural norms through their spatial and lifestyle practices [

38]. Meanwhile, Huyen, L.T. has investigated how the migration experiences of migrants influence their prosocial behavior toward their home communities [

39].

Urban-to-rural migration is also intricately tied to evolving lifestyle practices that manifest spatially. Sahin, T. has conducted a study on how people, in an effort to escape the pressures of urban life, tend to pursue a simpler and slower lifestyle in rural areas [

40]. Helbich, H. has conducted a spatial analysis of urban-to-rural migration in the Vienna metropolitan area, revealing that such migration is not only driven by lifestyle preferences but also influenced by spatial and economic factors [

41]. Zollet, S. et al. has conducted a study on urban-to-rural lifestyle migrants on the islands of Japan’s Seto Inland Sea, focusing on how they construct a high quality of life in the context of small island communities [

42]. Ji, N.Y., through ethnographic research, has illustrated how young migrants reinterpret and reconfigure rural life through everyday practices [

43]. In parallel, Bao, A. has investigated the entrepreneurial dynamics driven by migrants and their role in catalyzing rural economic restructuring [

44], while Yamamoto, S. has studied migrant-led development of rural accommodations and the associated exchange-oriented spatial practices [

45]. Wu, M. has further explored interactions between migrants and locals, revealing how these engagements contribute to spatial restructuring and the renegotiation of community boundaries [

46].

Existing studies [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29] often conceptualize migrants either as passive occupants of rural space or as contributors to rural revitalization, but have paid comparatively limited attention to the ways in which physical space functions as a medium through which values, identities, and social relations are manifested, negotiated, or restructured. This study does not treat space as the primary object of inquiry, but rather as an analytical lens for examining broader social–cultural processes. Specifically, it investigates how migrants—individuals originating from urban areas who relocate to rural areas—interact with the built environment in ways that reflect their everyday practices and spatial preferences. These interactions may, in turn, influence existing spatial norms, local cultural dynamics, and patterns of rural–urban interconnection.

The distinctive and innovative contribution of this study lies in its examination of how urban-to-rural migrants influence the traditional values of vernacular villages—encompassing both architectural characteristics and everyday life practices—through their spatial and lifestyle interventions. By analyzing this spatial process, the research seeks to deepen the understanding of transformation mechanisms in traditional villages under the contemporary wave of urban-to-rural migration. While grounded in the Chinese context, the findings offer broader analytical relevance for global discussions on rural change. Moreover, as rural areas increasingly absorb urban populations, both in-migrants and original residents are confronted with complex spatial and social challenges. In this context, examining the built environments created by migrants from urban areas becomes essential for envisioning more rational, inclusive, and adaptive models for future rural spatial development.

2. Methodology and Materials

Zhejiang Province is one of China’s most economically developed and highly urbanized regions. It is situated at the intersection of urbanization and post-urbanization processes. Simultaneously, it has been among the earliest provinces to implement rural revitalization policies and to initiate various forms of rural spatial and institutional restructuring. Programs such as the “Beautiful Countryside” initiative, the development of rural creative industries, and land use policy reforms have contributed to conditions conducive to urban-to-rural relocation.

Urban-to-rural migration, typically associated with later stages of urbanization, has emerged earlier and with greater complexity in Zhejiang compared to other regions. This has resulted in the development of hybrid rural spaces within traditional villages, incorporating residential, commercial, and cultural functions. These dynamics make Zhejiang an empirically relevant site for examining urban-to-rural migration buildings (hereafter referred to as UTRMBs). The interactions between diverse actors—including migrants from urban areas and local residents—reveal processes of spatial negotiation, identity reconstruction, and future-oriented rural development.

In the process of selecting research sites, we first conducted a preliminary screening of several representative villages based on criteria such as geographical location, transportation accessibility, demographic scale, industrial structure, and the condition of traditional village conservation and utilization. This was followed by consultations with local governments and village committees to evaluate the significance of urban-to-rural migration in each village and its compatibility with the research objectives. Practical considerations, including time and resource constraints for fieldwork, were also taken into account. Ultimately, three villages—Shishe, Chenjiapu, and Kenggen—were selected as case studies. This selection not only ensured diversity and representativeness of the samples but also guaranteed the overall feasibility of the research.

Against this background, a combination of methods was employed to reveal the spatial characteristics and usage logics of UTRMBs. Initially, interviews were conducted with the residents of 51 UTRMBs to investigate their life experiences, spatial preferences, and perceptions of traditional rural values; the interview responses were subsequently encoded and standardized for quantitative analysis. Subsequently, architectural surveys and on-site measurements were carried out to document floor plans, structural features, and construction materials, thereby establishing a fundamental dataset of building spaces. Furthermore, spatial–behavioral analysis was employed through field observation and daily activity recording, linking migrants’ everyday practices with the architectural settings to uncover their strategies for negotiating between tradition and modernity. Ultimately, space syntax analysis was applied by constructing justified plan graphs and calculating indicators such as mean depth, total depth, and integration, in order to examine the relationship between migrant-built spatial forms and the continuity of traditional architectural values and lifestyles. The data were processed using Python (Version 3.9.0), and the figures were prepared using Adobe Illustrator (Version 2024).

This study comprises five components.

Figure 1 illustrates both the structural composition of the paper and the geographical location of the research sites. Specifically, in the results and analysis section, our field investigation and analytical work are organized into five subsections, each outlining the research scope, survey period, and methodological approach.

Section 3.1 investigates the spatial and lifestyle characteristics of traditional vernacular dwellings in the selected villages, establishing the foundation for subsequent comparative observations and the analysis of migrants’ impacts on village environments.

Section 3.2 examines the spatial tendencies of urban-to-rural migrants, while

Section 3.3 explores their strategies of renewing and reutilizing existing rural building spaces.

Section 3.4 analyzes the everyday practices and behavioral patterns of urban-to-rural migrants within the village context. Finally,

Section 3.5 synthesizes these dimensions to assess how traditional village spaces have been transformed under the influence of urban-to-rural migration.

Based on long-term observation and understanding of rural development and demographic data in Zhejiang Province, this study selected three villages—Shishe, Chenjiapu, and Kenggen—that exhibit a relatively high proportion of urban-to-rural migration as research sites. The three selected villages are all traditional settlements situated in mountainous areas. Despite their varying proximity to urban centers, these villages have preserved significant elements of traditional architecture and landscape. Their natural settings and vernacular spatial forms have attracted migrants from both within and beyond the region. As urban-to-rural migration and tourism have increased, these villages have undergone moderate commercialization while maintaining and integrating traditional cultural practices, leading to complex transformations in spatial and social structures. Although the empirical focus is on cases in Zhejiang, China, the research theme and methodology are not limited by region-specific or culturally embedded assumptions. Through field surveys, spatial coding, and statistical clustering, the study identifies multiple typologies of spatial–behavioral interactions. This framework supports cross-regional comparison and offers a structured pathway for understanding how urban-to-rural migrants participate in the reconstruction of rural space on a global scale.

Within these villages, we identified all urban-to-rural migrants and the 51 buildings they inhabit or utilize for residential or work purposes (

Figure 2) [

13]. We first conducted interviews with these migrants to gather information on their spatial preferences for rural living, the renovations or modifications they made to the buildings prior to moving in, and their current daily life practices. Following the interviews, on-site investigations were carried out on the corresponding buildings. Spatial information was documented through detailed measurements and architectural drawings, providing the empirical foundation for analyzing the spatial characteristics of urban-to-rural migrants’ buildings (UTRMBs) in the context of urban-to-rural migration. Drawing upon the collected data, we employed a combination of qualitative typological analysis and quantitative spatial assessment to examine migrants’ spatial preferences, architectural transformations, and the compositional features of UTRMBs.

Figure 3 presents a case study of one building in Shishe Village, illustrating the specific implementation of the research process described above. According to the research design, the lower-left corner of the diagram presents both the data collected from field investigations and the analytical results for the selected case building.

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. The Architectural and Lifestyle Features of Traditional Vernacular Dwellings in Selected Villages

This study begins with a literature review that identifies the core spatial characteristics of traditional vernacular dwellings in southeastern China. Knapp emphasizes the symbolic order and hierarchical spatial logic of traditional Chinese rural dwellings, particularly courtyard-centered layouts and clan-based organization [

47]. Steinhardt outlines key structural features such as timber framing, modular proportions, and continuity in form across dynastic periods [

48]. Nancy, S. highlights the interplay between architecture and agrarian life, showing how domestic space responded to seasonal labor rhythms and gendered roles [

49]. Zhou focuses on southeastern vernacular forms, identifying black-tiled gable roofs, whitewashed walls, layered courtyards, and climate-responsive zoning [

50]. Lu adds insights into settlement adaptation, such as the integration of work and living spaces, use of local materials, and flexible internal layouts [

51]. These findings collectively provide a comparative basis for assessing how UTRMBs maintaining, reinterpreting, or transforming traditional spatial forms in the context of urban-to-rural migration.

As illustrated in

Figure 4, the presence or absence of key architectural features, as identified in the literature on traditional vernacular dwellings, was systematically assessed. The red markings denote the presence of each feature, allowing for a visualized comparison across cases and an evaluation of the degree of traditional continuity. Based on the observation of traditional vernacular dwellings in the study cases and the identification of traditional features within the UTRMBs, this research provides a typological summary of the vernacular architectural characteristics found in the selected villages. First, regional construction methods constitute the primary axis defining the typological traits of vernacular dwellings. In terms of materials and structures, the dwellings observed in the cases include timber-frame buildings, brick-and-stone buildings, rammed-earth buildings, and hybrid structures. Accordingly, the traditional dwellings identified in this study can be categorized into four main types: (1) single-structure detached buildings, (2) hybrid-structure detached buildings, (3) courtyard (lightwell) single-structure buildings, and (4) courtyard (lightwell) hybrid-structure buildings. From

Figure 4, it can be observed that the selected cases in this study exhibit the main characteristics of vernacular dwellings, which strongly reflect regionally distinctive construction traditions. These features can be summarized as follows: a simple linear floor plan layout; construction methods utilizing locally available materials such as stone masonry and rammed earth; and gable roofs covered with black tiles, supported by timber structures. These categories represent the principal spatial environments inhabited by both local residents and urban-to-rural migrants.

Building upon empirical data and drawing on the spatial characteristics identified in the prior literature,

Figure 5 presents a set of spatial archetypes rooted in local vernacular traditions. These archetypes serve as key reference points for assessing the extent to which migrant buildings follow patterns of spatial continuity, transformation, or deviation. The alignment between field observations and theoretical frameworks provides a robust foundation for subsequent analyses of spatial change and lifestyle variations.

In parallel, qualitative interviews with long-term residents provided insights into traditional lifestyle patterns that historically shaped rural spatial use. Local livelihoods once followed an agricultural rhythm centered on rice and tea production, often accompanied by household poultry or livestock. Daily and seasonal activities—including spring planting, tea harvesting, autumn drying, and winter food preservation—formed the temporal structure of village life. Courtyards and household thresholds served as key spaces for social interaction, hosting morning routines, shared meals, and informal gatherings. Community rituals and festivals—such as Winter Solstice ceremonies—were commonly held in village squares or other communal open spaces.

While many of these practices have declined due to socioeconomic transformation, they continue to represent important cultural values. Assessing whether and how these traditional features are retained or reinterpreted in migrant-renovated dwellings provides a critical lens for understanding the continuity of rural heritage and the evolving identity of vernacular spaces under the influence of urban-to-rural migration.

3.2. Urban-to-Rural Migrants’ Rural Spatial Inclinations

To explore how urban-to-rural migrants’ spatial preferences reflect their engagement with traditional rural values, this section analyzes interviews and field surveys conducted in three villages. The investigation focuses on how migrants select building locations, interpret the surrounding village context, and define their functional and spatial requirements. By linking individual choices to broader patterns of heritage recognition or transformation, this section sheds light on the ways migrants negotiate between personal aspirations and vernacular traditions.

3.2.1. Spatial Needs and Preferences of Migrants

This section examines how the spatial preferences of urban-to-rural migrants reflect their attitudes toward traditional architectural values and rural spatial logic. To capture migrants’ spatial choices, we focused on two dimensions—functional layout and spatial articulation—and identified related elements through field surveys. These were then interpreted not only as indicators of personal needs, but also as value-oriented choices reflecting either continuity or disruption of vernacular traditions. Building upon these profiles, a typological classification of UTRMBs was developed. The following analysis presents this classification in detail.

As shown in the left half of

Figure 6, the fundamental elements of functional composition are organized into four dimensions: (1) the number of distinct functions accommodated within the building; (2) the presence of nature-integrated spaces; (3) multi-household occupancy; and (4) the inclusion of entrance–front spaces that serve as key nodes of neighborhood interaction in the rural setting. These dimensions are further refined into four categories comprising seven specific elements. In this context, nature-integrated spaces refer to open-to-sky architectural features commonly found in traditional Chinese rural dwellings, such as courtyards and skywells. The meanings represented by each subfigure are as follows:

Figure 6A: Single-functional building.

Figure 6B: Multi-functional buildings, combining residential use with other functions.

Figure 6C: Public space in front of building.

Figure 6D: Buildings with skylights or roof openings.

Figure 6E: Buildings featuring terraces as extended outdoor spaces.

Figure 6F: Buildings with separate entrances for different units or functions.

Figure 6G: Buildings with common/shared entrances. The right half of

Figure 6 analyzes the spatial articulation of UTRMBs through four aspects: (1) the degree of decorative treatment at the threshold between interior and exterior spaces; (2) the structural system employed; (3) the level of spatial openness or enclosure; and (4) the building’s entry mode. These aspects are grouped into four categories encompassing 10 distinct spatial conditions. The observed structural systems include both traditional techniques—such as rammed earth and timber framing, typical of local vernacular construction—and modern materials such as brick masonry and reinforced concrete, which are commonly used in more recent buildings. The meanings represented by each subfigure are as follows:

Figure 6a: Dwellings with exposed finishes.

Figure 6b: Dwellings with refined finishes.

Figure 6c: Dwellings constructed with rammed earth.

Figure 6d: Dwellings constructed with timber.

Figure 6e: Dwellings constructed with stone or concrete.

Figure 6f: Dwellings with moderate spatial enclosure.

Figure 6g: Dwellings with more open spatial form.

Figure 6h: Dwellings with more enclosed spatial form.

Figure 6i: Dwellings with entry provided via a courtyard.

Figure 6j: Dwellings with direct entry from outside.

Drawing on the fundamental elements established in

Figure 7, we identified the spatial preference characteristics of each UTRMB based on field survey data. These characteristics were extracted and synthesized for all 51 buildings, as illustrated in

Figure 7a. The results indicate that only a small number of UTRMBs share identical spatial preference combinations. In most cases, variations in migrants’ identities, lifestyles, and cultural backgrounds give rise to a wide diversity of spatial preferences. Based on the data presented in

Figure 7a, spatial articulation preferences were categorized into three types: rural heritage-oriented, urban heritage-oriented, and hybrid. These reflect migrants’ respective inclinations toward rural spatial aesthetics, urban spatial aesthetics, and a fusion of the two. Similarly, functional composition preferences were classified into three categories: residential use, commercial use, and multi-user/multifunctional use. By integrating these two dimensions,

Figure 7b presents a typology of the 51 UTRMBs, resulting in eight distinct combined types. Notably, the most dominant type (CU: Commercial + Urban-oriented), which accounts for 20 out of the 51 cases (39%), indicates that a considerable number of migrants project their urban living experiences and aesthetic preferences into the rural environment, thereby reshaping local spatial practices and potentially challenging the continuity of vernacular traditions.

Based on the interview data, which focused on six dimensions—material use, spatial openness, color preference, interior atmosphere, the presence or absence of courtyards, and the number of building stories—a cluster analysis was conducted. The results are presented in

Figure 7c. The clustering identified three groups of spatial preferences. Among them, Cluster 1 reflects alignment with traditional rural spatial logic, while Cluster 2 represents strong detachment from vernacular norms. Cluster 3 is characterized by hybrid or flexible spatial inclinations, often combining vernacular elements with modern spatial needs. PCA further reveals a clear axis from spatial continuity to transformation, underscoring the contested nature of urban-to-rural migration in shaping rural architectural values.

From the figure, it can be observed that only a small number of UTRMBs exhibit identical spatial preference combinations, highlighting the diversity of migrants’ choices. The typological classification of spatial articulation preferences reflects migrants’ orientations toward rural, urban, or hybrid spatial aesthetics. The predominance of the CU type indicates a strong tendency among many migrants to transplant their urban experiences into the rural environment, a process that may challenge the continuity of vernacular spatial systems. Rather than uniformly preserving or rejecting rural traditions, urban-to-rural migration demonstrates diverse spatial practices shaped by individual needs and experiences, revealing an ongoing negotiation and reconstruction between rural traditionality and urban modernity.

3.2.2. Accessibility of Rural Resources and UTRMBs

In this section, we adopt an alternative perspective to analyze the spatial tendencies of urban-to-rural Migrant Buildings (UTRMBs) within the rural context, focusing on the interplay between resource availability and spatial accessibility. As shown in

Figure 8, rural resources are categorized into two major types—natural resources and built environment resources—encompassing a total of seven distinct elements. The meanings represented by each subfigure are as follows:

Figure 8(I): Waterscape.

Figure 8(II): Topographic landscape.

Figure 8(III): Agricultural landscape.

Figure 8(IV): Public plaza.

Figure 8(V): Cultural center.

Figure 8(VI): Waterfront deck.

Figure 8(VII): Roadside areas. To evaluate spatial accessibility, three key indicators were established: (1) the distance from the village’s main entrance; (2) the hierarchical level of the adjacent road; and (3) the number of directional turns required to reach the building. The meanings represented by each are as follows:

Figure 8(i): Building entrance located within 100 m of the rural entrance.

Figure 8(ii): Building entrance located within 150 m of the rural entrance.

Figure 8(iii): Building entrance located within 200 m of the rural entrance.

Figure 8(iv): Building located along the main road.

Figure 8(v): Building located along a side road.

Figure 8(vi): Path to the building with no more than three turns.

Figure 8(vii): Path to the building with three to six turns.

Figure 8(viii): Path to the building with more than six turns. These indicators were further operationalized into eight distinct spatial conditions to capture variations in accessibility across UTRMBs.

Using the metrics defined in

Figure 8, we evaluated the spatial characteristics of 51 UTRMBs in terms of both resource availability and spatial accessibility. As shown in

Figure 9a, the combined assessment of these two dimensions yielded 31 unique spatial conditions. To uncover broader patterns within these cases, we grouped them into generalized categories. For resource availability, three orientations were identified: landscape-oriented, built environment-oriented, and hybrid-resource-oriented. For accessibility, three levels were defined: easy, moderate, and limited.

Figure 9b presents a typology comprising eight synthesized spatial types derived from the original 31 combinations. Among the nine theoretically possible types, eight were identified in the study sample. Notably, the MC type (Moderate Accessibility + Combined Resources) and the LL type (Landscape-Oriented Resources + Limited Accessibility) were the most common, each accounting for 12 UTRMBs. In contrast, the ES type (Easy Accessibility + Spatial-Oriented Resources) was absent from the dataset. These findings suggest that UTRMBs are often located in visually prominent yet spatially secluded areas, reflecting migrants’ selective appropriation of traditional environmental elements—such as landscape, farmland, and communal boundaries—as part of their personalized rural lifestyle strategies.

Building on the approach employed in

Section 3.2.1, we conducted in-depth interviews to explore migrants’ subjective valuations of key rural living elements. The responses were categorized into six dimensions: mountain scenery, water features, farmland settings, public plazas, cultural centers, and interactions with local residents. These qualitative insights were subsequently quantified for cluster analysis and principal component analysis (PCA). As shown in

Figure 9c, the clustering results revealed three distinct groups: Cluster 1 includes individuals with both high accessibility and strong engagement with rural resources; Cluster 2 represents respondents with generally limited access to such resources; and Cluster 3 consists of those with good access to natural resources but relatively weak connectivity to communal rural spaces. In the PCA, the first principal component reflects the degree to which migrants prioritize engagement with traditional rural environments, while the second represents a value orientation continuum between naturalistic immersion and built-environment convenience. Notably, the results show that UTRMB residents from the same village are distributed across different clusters, indicating that spatial preference is not solely determined by geographic location within the village. Instead, individual factors—such as personal background, values, and lifestyle choices—play a more decisive role in shaping residential behavior and spatial selection.

The above analysis indicates that the location choices and spatial utilization of migrants are not determined solely by objective conditions, but rather reflect explicit value orientations and lifestyle strategies. Although 31 spatial condition combinations were identified, only a few were frequently selected, most notably, those situated in visually prominent yet less accessible areas. This pattern suggests that migrants prioritize the symbolic and experiential value of the natural environment offered by villages over its practical functionality. While natural environmental resources are actively integrated into migrants’ everyday practices, their engagement with public spaces and communal interactions appears comparatively weak. This implies that the traditional spatial values of rural settlements are sustained in the environmental dimension but fractured in the social dimension. These findings further demonstrate that urban-to-rural migration does not represent a simple restoration of tradition; instead, it reconstructs spatial relations between tradition and modernity through individualized and selective practices.

3.3. Utilization Patterns of Rural Buildings’ Spaces by Migrants

In this section, we investigate how urban-to-rural migrants utilize and transform rural building spaces, focusing on the ways their spatial interventions reflect personal preferences while negotiating with traditional spatial norms. Based on field surveys of 51 buildings and interviews with migrants, we examine how existing vernacular structures were adapted—rather than entirely replaced—highlighting selective preservation, functional reinterpretation, and incremental modifications. This analysis provides insight into how migrant practices influence the spatial continuity or disruption of traditional rural values.

3.3.1. Spatial Transformation of UTRMBs: Negotiating Traditional Values Through Adaptive Practices

To meet the dual demands of living and working in rural settings, urban-to-rural migrants often undertake renovations or partial reconstructions of existing buildings. However, due to conservation policies aimed at preserving the integrity of traditional rural spatial fabric, complete demolition and redevelopment are strictly regulated. As a result, incremental and adaptive transformations have emerged as the predominant mode of spatial intervention. Drawing on detailed architectural surveys and in-depth interviews, this study traces the transformation trajectories of UTRMBs. Beyond physical alterations, such transformations serve as platforms through which migrants reinterpret and reconfigure traditional spatial logic. To better understand these processes, two analytical dimensions are proposed: morphological adaptation, which examines changes in building form and structure, and interface articulation, which focuses on the spatial and visual negotiation between public and private realms.

As shown in

Figure 10, morphological adaptation is categorized into four distinct types: complete reconstruction, extension, internal spatial reconfiguration, and preservation of the original layout. Correspondingly, interface articulation is classified into three types: exterior surface renovation, interior surface renovation, and combined renovation of both interior and exterior surfaces. A cross-analysis of these two dimensions yields nine spatial transformation scenarios, which are further grouped into three overarching categories: newly constructed spaces, partially renovated spaces, and spaces that retain their original configuration. Among these, only two cases involve entirely new constructions—both located on the peripheries of Kengen Village and Chenjiapu Village, respectively—and are used for commercial purposes as guesthouses. Their peripheral placement, outside the core heritage preservation zones, reflects both regulatory constraints and strategic locational choices negotiated by the migrants. More importantly, these transformation types reflect varying levels of migrants’ engagement with traditional spatial values—ranging from preservation to reinterpretation and replacement. The most common scenario involves the preservation of the original building layout accompanied by selective interior surface renovation. This approach suggests an economically pragmatic strategy adopted by many urban migrants during resettlement, as it minimizes renovation costs while meeting basic spatial needs. Such strategies also reflect an intent to balance modern comfort with traditional spatial patterns, especially among migrants who value cultural continuity. Notably, several buildings—such as C1, C2, C3, C10–C18, and K10—were designed and constructed with the involvement of professional architects. In contrast, the remaining cases were adapted by local craftsmen under the guidance of the migrants themselves. While the former group tends to demonstrate conscious design interventions, the latter often reveals spontaneous yet meaningful acts of spatial preservation or adaptation. Nevertheless, many of these latter examples demonstrate a surprisingly high standard of spatial quality. This spatial quality is primarily reflected in the overall performance of these UTRMBs in terms of functionality, comfort, and ambiance. It encompasses the use of local materials and construction techniques, the treatment of spatial decoration, and the conscious response to the rural landscape. In doing so, these buildings not only fulfill everyday living needs but also reveal a sensitivity to local culture, as well as a certain degree of personal aesthetic expression. This observation suggests that urban-to-rural migrants, regardless of professional support, often possess sufficient cultural capital and value-driven motivation to engage with vernacular traditions in creative and context-sensitive ways.

Accordingly, it can be observed that the spatial transformations undertaken by migrants are not merely superficial updates, but rather reflect a dynamic negotiation between economic rationality, cultural continuity, and modern comfort. The peripheral distribution of newly constructed cases not only indicates passive responses to regulatory constraints but also reveals migrants’ conscious efforts to avoid culturally sensitive zones. The most prevalent strategy—preserving the original layout while selectively renovating interior surfaces—demonstrates that, under limited resources, migrants tend to meet residential needs with minimal investment while maintaining a symbolic connection to local traditions. In this process, the migrants’ own economic capital and cultural values emerge as decisive forces in shaping spatial transformation. Through selective appropriation and creative reinterpretation, vernacular dwellings are both partially preserved and endowed with new layers of meaning. This form of “modernization grounded in locality” constitutes a critical contribution of urban-to-rural migration to the ongoing reproduction of rural space.

3.3.2. Spatial Composition Characteristics of Migrants’ Houses

Traditional vernacular dwellings in the selected Zhejiang villages exhibit similar spatial characteristics rooted in regional construction logic, including materials, structure, and spatial hierarchy. This shared foundation provides a comparative basis for examining how urban-to-rural migrants reinterpret, appropriate, or diverge from vernacular spatial values in the process of inhabiting and modifying rural spaces. In this section, we present simplified first-floor plans of all surveyed buildings and analyze the spatial composition of UTRMBs from two perspectives: user affiliation and spatial layout, with attention to whether these compositions conform to or transform traditional rural living patterns.

Figure 11 shows that UTRMBs present diverse user affiliations, ranging from shared use by multiple migrants to cohabitation between migrants and local residents. These shared configurations reflect evolving spatial practices and community relations in rural settings, suggesting both pragmatic adaptation and partial reinterpretation of communal living traditions. Among buildings solely occupied by migrants, two dominant forms are observed: single-use (residential or commercial) and mixed-use structures, each reflecting different orientations toward vernacular use patterns.

In terms of spatial layout, three basic typologies are identified: detached buildings, courtyard or skywell-centered structures, and clustered compounds. Courtyard and cluster forms show greater continuity with traditional spatial logic, whereas detached layouts often reflect urban-influenced individualization. The relatively even distribution of these types suggests that migrants are selectively appropriating traditional forms based on personal preferences and functional needs. Functionally, UTRMBs tend to serve one or two purposes, with multifunctional configurations being rare. The most frequent type—SiD (single-use, detached)—reflects an individualized, purpose-specific spatial approach that contrasts with the multifunctional, collective-use logic of traditional rural compounds. Conversely, types such as SiC (single-use, clustered) that retain vernacular spatial grammar appear marginal. This distribution illustrates a broader trend: urban migrants reshape rural buildings in ways that partially decouple from the spatial multifunctionality of traditional dwellings.

Beyond demonstrating the diversity of UTRMBs in terms of user affiliation, spatial layout, and functional composition,

Figure 11 also reveals the differentiated trajectories of migrants in the process of “re-localization.” On the one hand, the presence of shared dwellings and courtyard-based configurations indicates attempts by some migrants to integrate into traditional spatial logics and rural social relations. On the other hand, the prevalence of detached and individualized spaces reflects tendencies toward urban-influenced individualization and functional segmentation. This juxtaposition suggests that migrants have not established a uniform paradigm of rural spatial practice but rather oscillate between collectivized and individualized, and multifunctional and single-purpose approaches. Moreover, the traditional forms of public interaction in rural society appear to be weakening, gradually replaced by a new spatial logic in which certain UTRMBs with partial communal functions emerge as focal points of social life. This shift potentially restructures the modes of social interaction within the village.

3.4. Analysis of Migrants’ Lifestyles Based on Residential Preferences and Spatial Realities

To further examine how urban-to-rural migrants engage with architectural space and to gain deeper insight into their everyday life within the village context, this section investigates how their lifestyle practices function as spatial interventions that reinterpret or reconfigure vernacular norms. Drawing on data collected through in-depth interviews, and by analyzing spatial routines and patterns of use, the study offers a more nuanced understanding of how these migrants’ everyday spatial behaviors contribute to both the continuation and transformation of traditional village architecture. Building on the findings from

Section 3.1,

Section 3.2 and

Section 3.3, this analysis synthesizes interview insights to identify the types of rural lifestyles adopted by urban-to-rural migrants, and to assess their implications for the evolving relationship between contemporary migrant practices and the spatial–cultural logic of vernacular environments.

3.4.1. Everyday Practices of Migrants in UTRMB Space

Based on interview data and on-site observations,

Figure 12a illustrates a total of 15 common types of activities—excluding basic functions such as eating and sleeping—across the three studied villages. These activities are grouped into four thematic categories: service-oriented activities, social interactions, creative and productive activities, and community-based activities. Among them, service-oriented and social interaction practices are the most frequently observed, indicating a shift toward spatial functions that extend beyond conventional domesticity.

Figure 12b presents a cluster analysis based on the presence or absence of these activities within each UTRMB, coded as 1 or 0, respectively. The results yield five distinct clusters across the 51 buildings: (1) Basic Reception Type, (2) Standard Guesthouse Type, (3) Social–Service Hybrid, (4) Creative–Public Space, and (5) Handcraft–Creative Type. The distribution of cases is relatively balanced, though Types (1) through (3) are more prevalent. Notably, no examples of Type (4) were found in Kengen Village, and Type (5) was absent in Shishe Village, suggesting spatial and cultural limitations in supporting more community- or creativity-oriented practices.

To further examine the underlying structure of spatial behaviors, a principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted on the 15 activity variables. The first principal component (PC1) explains the largest portion of variance and represents the degree of functional complexity within each UTRMB. It reflects the transition from single-purpose uses (e.g., basic reception) to multifaceted arrangements that incorporate service, creativity, and interaction. The second component (PC2) captures the orientation of behavioral emphasis—ranging from outward-facing social connectivity to inward-focused productive or artistic practices. Together, the two components construct a behavioral space that reveals a functional spectrum across UTRMBs. Unlike discrete clusters, this spectrum illustrates a continuum of spatial adaptation, where everyday practices evolve from reception-oriented functions to more diversified forms of living that reshape the architectural roles of rural dwellings.

This transformation highlights the growing tendency of migrants to reinterpret vernacular space not merely as a residence but as a platform for social engagement, economic productivity, and cultural expression. In doing so, they challenge and expand the traditional boundaries of rural domestic space, contributing to an evolving landscape of everyday rural life. A linear regression analysis was also conducted to examine the relationship between PC1 scores and behavioral complexity, defined as the total number of distinct activities per building. The regression equation (Behavioral Complexity along PC1) is:

This linear relationship confirms that greater spatial functionality correlates with richer and more diverse lifestyles. It further underscores that urban-to-rural migrants are not passive occupants but active agents who reconfigure the spatial logics of rural life, embedding new values within inherited forms.

3.4.2. Types of Rural Lifestyles of Urban-to-Rural Migrants

This section explores how urban-to-rural migrants engage with traditional village space by examining their spatial preferences and everyday practices. Using data from 51 buildings occupied by migrants (UTRMBs), we develop a spatial–behavioral typology that captures the ways in which migrants reinterpret, preserve, or transform traditional rural values. Drawing on prior spatial and behavioral analyses (

Section 3.2,

Section 3.3 and

Section 3.4), five core dimensions were selected for typological coding: spatial aesthetics and use intention, resource orientation and accessibility, degree of architectural transformation, user and layout configuration, and dominant functional behavior. These were integrated into a “space–lifestyle coupling model” to analyze how built form and everyday life co-evolve under urban-to-rural migration.

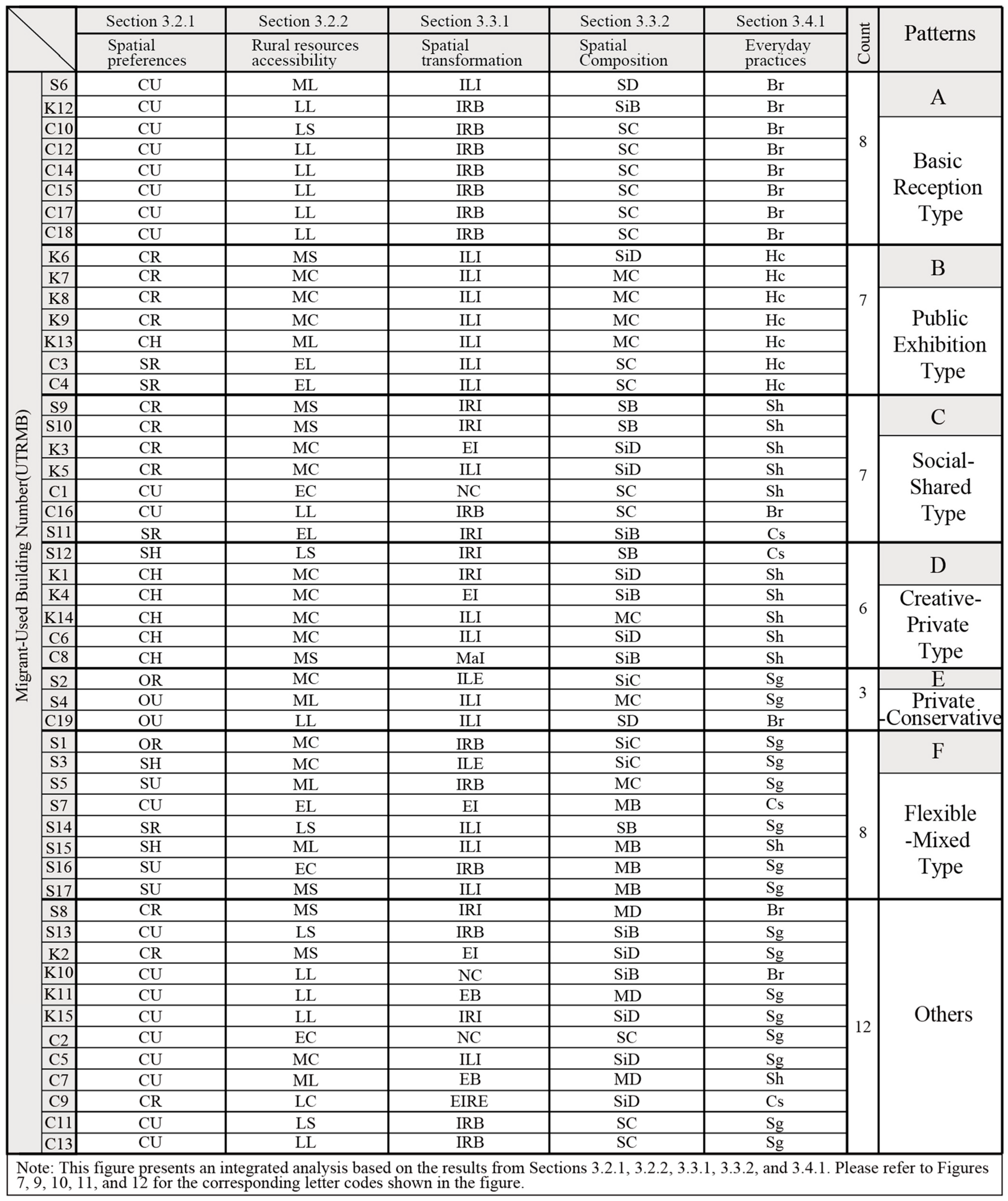

Rather than treating each variable separately, we treat each building as a composite profile reflecting the migrant’s spatial strategies and lifestyle logics. Through comparative analysis of frequency and semantic convergence, we identified recurring combinations that signify coherent ways of inhabiting and reconfiguring village space. Based on this approach, six representative lifestyle types were extracted in

Figure 13, each embodying distinct relationships with traditional spatial values.

Type A: Commercial Reinterpretation Type. Characterized by hybrid or urban aesthetics, moderate architectural transformation, and high service intensity, this type often converts traditional structures into guesthouses or cafés. While such interventions introduce new vitality and economic functions into the village, they also risk displacing traditional spatial and cultural norms.

Type B: Cultural Transmission Type. These spaces retain traditional forms while integrating exhibition and event functions. The users tend to emphasize symbolic expression and historical narratives, contributing to the reinterpretation and selective preservation of local heritage.

Type C: Social Co-living Type. This group favors communal layouts and shared uses, often blending private and public functions. Through daily interaction with neighbors or visitors, these migrants foster alternative forms of community, sometimes diverging from conventional kin-based social structures.

Type D: Creative Individualism Type. Characterized by deep transformation and highly personalized design, this type reflects an inward-oriented lifestyle. While contributing architectural novelty, such cases may undermine the continuity of spatial typologies and collective identity.

Type E: Conservative Integration Type. Migrants in this group favor minimal intervention and strong alignment with rural aesthetics. Their practices suggest a respect for traditional domestic norms, emphasizing stability, self-sufficiency, and quietness.

Type F: Experimental Hybrid Type. These are transitional or multifunctional spaces with mixed attributes and evolving uses. The ongoing negotiations between modern needs and traditional constraints in these cases exemplify the dynamic and contested nature of value reproduction in rural settings.

These six types demonstrate how migrants not only occupy rural buildings but also actively participate in the cultural, spatial, and symbolic reshaping of rural traditions. Some lifestyles support the adaptive preservation of traditional forms and values, while others introduce disruptive spatial logic or new cultural meanings. Together, they represent a spectrum of interventionist practices that reframe what it means to “live traditionally” in the context of contemporary rural transformation.

3.5. Analysis of the Continuity of Traditional Spatial Features in Representative UTRMBs

To understand how the spatial interventions of urban-to-rural migrants affect the transformation of traditional values in rural architecture, this section assesses the extent to which traditional spatial structures are preserved, adapted, or transformed in representative UTRMBs. This analysis builds upon the spatial typologies, compositional patterns, and lifestyle behaviors detailed in

Section 3.2,

Section 3.3 and

Section 3.4, while using the findings of

Section 3.1, on the architectural and lifestyle features of traditional vernacular dwellings, as the normative benchmark for assessing continuity.

Section 3.1 identified key spatial characteristics of vernacular buildings in the studied villages, such as central courtyards, axial symmetry, inward-facing layouts, and spatial gradation from public to private. These features are taken as the baseline criteria for evaluating the extent to which migrant-built or renovated dwellings align with, reinterpret, or depart from local traditions.

Methodologically, this section adopts Justified Plan Graph (JPG) analysis combined with space syntax indicators—specifically, Integration (Int) and Control Value (CV)—to evaluate the continuity of spatial logic in UTRMBs. Based on Hillier’s syntactic theory [

52], the analysis transforms building plans into hierarchical graphs, where nodes represent individual spaces and edges represent direct connections. Integration reflects the spatial depth of each space from the main entrance, indicating its relative centrality; Control Value reflects the degree to which a space governs access to its neighboring spaces. These indicators capture the centrality, depth, and dominance of each space and serve as critical metrics to assess whether the spatial logic aligns with vernacular traditions.

Here are the three key formulas used to calculate the syntactic values of each spatial unit in the JPG (Justified Plan Graph) diagram:

- (2)

Integration (Relative Asymmetry):

- (3)

Control Value

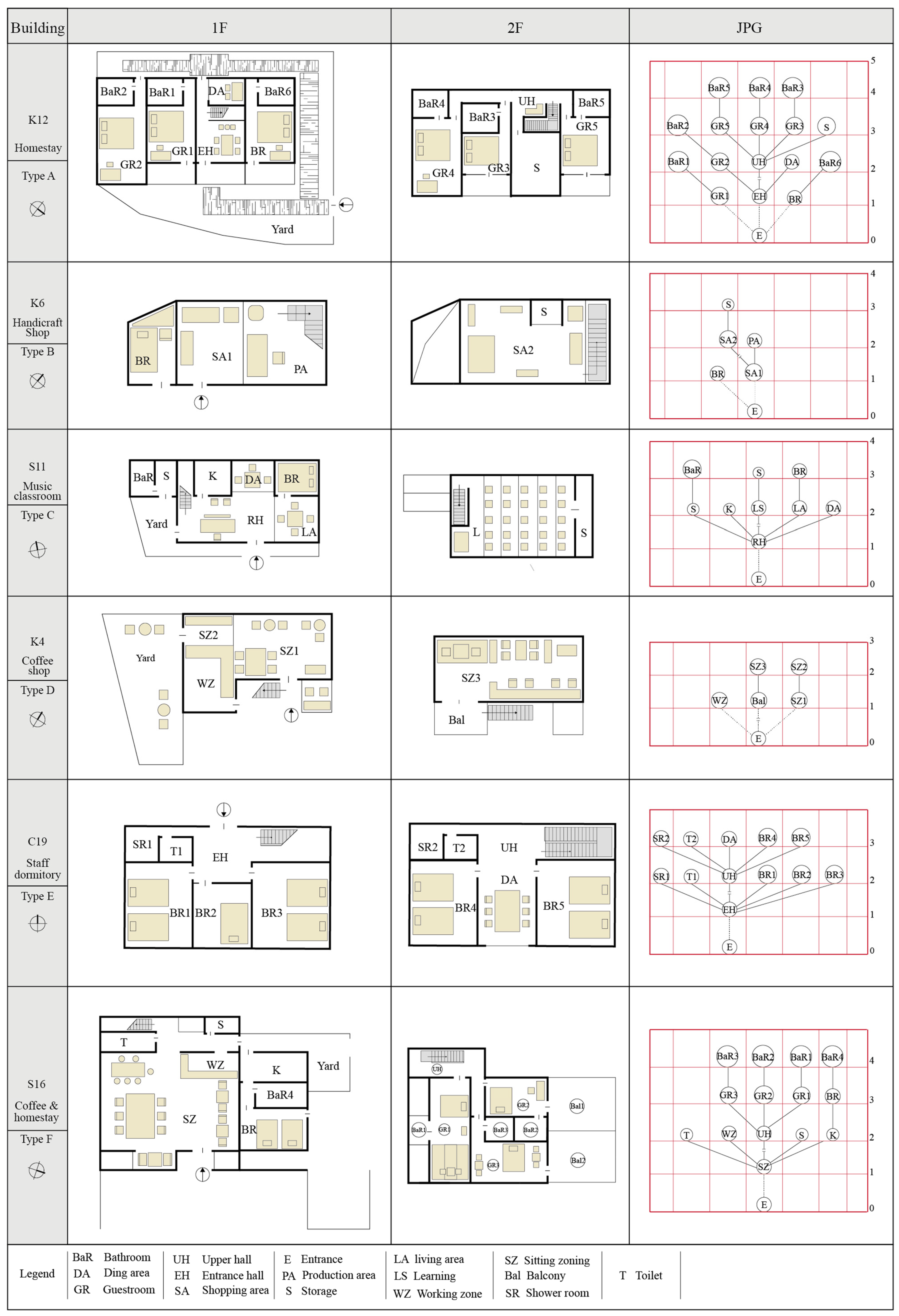

Figure 14 illustrates the spatial layouts and justified plan graphs (JPGs) of representative UTRMBs, showing differences in spatial configuration across various lifestyle types.

Figure 15 presents the syntactic measures of these representative UTRMBs, comparing depth, integration, and control values to reveal variations in spatial properties among different building types. As illustrated in

Figure 14, among the six representative UTRMBs, three buildings—K12 (Type A, Homestay), S11 (Type C, Music Classroom), and K4 (Type D, Coffee Shop)—exhibit strong continuity with traditional spatial logic. These buildings feature clear central nodes, hierarchical spatial depth, and axial or symmetrical layouts, with relatively high integration values (Mean i ≥ 0.9, according to

Figure 15), aligning closely with the centripetal, enclosed, and hierarchical organization typical of vernacular courtyard houses. For instance, the JPG graph of K12 reveals a central pathway from the entrance through the entrance hall (EH) and dining area (DA) to guest rooms (GR), forming a cohesive inward-facing structure.

S11 unfolds around a central hall, reinforcing its spatial core, while K4—despite its commercial use—retains a symmetrical configuration reminiscent of the traditional “main hall + side rooms” layout. In contrast, buildings such as C19 (Type E, Staff Dormitory), S16 (Type F, Mixed-use), and K6 (Type B, Handcraft Shop) diverge from traditional syntax. They display more decentralized, open-ended structures with parallel or mixed-use spatial configurations. Their JPG graphs reflect lower integration values (Mean i < 0.8, according to

Figure 15) and dispersed control values, lacking a discernible central–subcentral hierarchy. For example, C19’s dorm rooms are arranged in parallel, S16 presents a blend of functional zones without a spatial core, and K6, though slightly clustered, is primarily organized by commercial logic rather than vernacular domestic patterns. These contrasts highlight the spectrum of spatial continuity and transformation driven by migrants’ differing functional goals and aesthetic orientations.

Overall, the syntactic assessment confirms that migrants operate between reproduction and innovation. While some dwellings consciously preserve traditional spatial features to reinforce rural aesthetics or cultural identity, others depart from these logics to accommodate new functions or lifestyles. This suggests that urban-to-rural migration facilitates a continuum of transformation rather than a dichotomy between tradition and modernity. Migrants act as both inheritors and reinterpreters of rural spatial traditions, shaping new expressions of vernacular value through their building practices.

4. Discussion

This study, taking villages in Zhejiang Province as cases, reveals the evolving characteristics of residential spaces and traditional values in rural China against the backdrop of shifting urban–rural relations and the growing trend of urban-to-rural migration. By focusing on 51 UTRMBs across three villages, the research examines how these migrants reshape rural living environments through spatial strategies and everyday practices, and how their interventions simultaneously contribute to either the inheritance or the erosion of traditional rural features.

Based on the analysis of the architectural characteristics of selected vernacular dwellings (

Section 3.1), this study first establishes a foundation for understanding spatial traditions within rural forms. This benchmark provides a point of reference for the more detailed assessment of spatial and behavioral interventions undertaken by urban-to-rural migrants. Subsequently, through the analysis of spatial preferences, site selection, and locational strategies (

Section 3.2), the study links migrants’ urban backgrounds with their rural practices, uncovering the underlying motivations and pathways that shape these spatial decisions. Furthermore, by examining the concrete transformations in building morphology and functional layouts influenced by migrants (

Section 3.3), the research evaluates their attitudes toward traditional architectural features and the extent to which traditional values are maintained or reinterpreted. Individual interviews are then introduced to capture migrants’ everyday practices (

Section 3.4), serving as critical indicators for assessing their actual utilization of rural space and their interactions with local residents. This facilitates the development of a space–behavior coupling model, enabling a comprehensive evaluation of the changes that migration brings to rural living realities and traditional values. Finally, building upon the findings derived from typological analysis, the study conducts space syntax analysis of representative UTRMBs (

Section 3.5) to further reveal the degrees to which traditional spatial characteristics are preserved, modified, or eroded.

One key finding is that the spatial preferences of urban-to-rural migrants exhibit significant heterogeneity. While the prevailing narrative often assumes that the motivation for migration into rural areas is primarily driven by a pursuit of the “natural,” “simple,” and “authentic” qualities of rurality, most UTRMBs instead display characteristics of urban spatial forms or hybrid aesthetics that combine urban and rural elements. Such transformations are largely shaped by migrants’ prior urban living experiences, as well as their individual cultural and capital backgrounds. This hybridity is particularly prominent in the “Commercial + Urban-oriented” (CU type), where spatial outcomes reflect a negotiated balance between nostalgic attachments to tradition, practical living needs, and the pursuit of pastoral ideals. Cluster analysis of spatial preferences and locational choices further reveals that even within the same village, degrees of variation persist, suggesting that individual intentions and choices play a decisive role, rather than being solely determined by the environmental resources, spatial conditions, or natural attributes provided by the village context.

Through the typological analysis of renovation strategies applied to traditional spaces, it is evident that most interventions take the form of restorative and incremental modifications. Rather than large-scale reconstruction, migrants tend to adopt selective interventions, such as surface refurbishments and internal spatial reconfigurations, while striving to preserve the original floor layouts. On the one hand, this reflects pragmatic economic considerations; on the other, it demonstrates a balance between meeting modern functional needs and respecting the “material memory” of traditional villages. The involvement of professional architects and local craftsmen further underscores the hybrid and collaborative nature of rural spatial reproduction.

However, urban-to-rural migrants’ choices regarding the functional use and spatial layout of traditional dwellings are not merely a simple continuation of tradition, but rather show differentiated trajectories. On the one hand, the continuation and expansion of shared building and courtyard layouts reflect attempts by some migrants to maintain or reconstruct traditional community relations and spatial ties through collective use and spatial sharing. On the other hand, more migrants tend to choose detached houses with single functions, reflecting an individualized orientation and a logic of functional segmentation shaped by urban experiences. These two conditions indicate that a unified paradigm of spatial practice has not yet been formed in the current urban-to-rural migration phenomenon, and the traditional spatial logics of neighborhood sharing, collective utilization, and kinship-based organization are, to some extent, being replaced by new individualized spatial logics. This process is also accompanied by the hollowing out and aging of villages, which have led to the destruction and partial disappearance of traditional village values. At the same time, new possibilities are beginning to emerge: a small number of UTRMBs with public attributes are taking on new functions of social interaction, becoming places where migrants connect with each other, as well as with local villagers. While reshaping the spatial forms of vernacular dwellings, urban-to-rural migrants are also promoting the reorganization of village social relations. This finding has reference value for the planning and design of traditional villages, suggesting that planners may attempt to use UTRMBs as structural clues to organize village space.

By focusing on the daily practices of urban-to-rural migrants, it becomes evident that diverse modes of living unfold within the tension between “tradition” and “modernity.” The widespread presence of basic reception-oriented and standardized homestay types demonstrates that most migrants, driven primarily by commercial purposes, adopt low-cost strategies of service-oriented utilization. While such strategies endow spaces with specific functional and commercial value, they simultaneously diminish the diversity of vernacular rural life. In contrast, the social–service hybrid type and the cultural heritage-oriented type embed activities and exhibitions into spatial settings, thereby assuming the role of courtyards or village squares as arenas of public interaction, and revealing migrants’ engagement in narrating and reconstructing local cultural memory. The PCA analysis of behavioral complexity further reveals a linear relationship, suggesting that migrants’ spatial practices are not confined to distinct categories but instead follow a gradual process that evolves “from single-purpose reception to multifunctional integration.” This indicates that migration to the countryside is not merely a change in location, but rather an ongoing spatial experiment in which practices are continuously adjusted. Within this process, all migrants face the same fundamental challenge: how to negotiate new lifestyle demands within the constraints of the vernacular rural framework.

Through the analysis of 51 UTRMBs, this study identified six typical “migrant space–lifestyle” patterns. These patterns reveal how urban-to-rural migrants generate differentiated spatial practices and value orientations through the interaction between individual experiences and local conditions, thereby providing a transferable analytical model for future cross-regional and cross-case comparative studies. In the Justified Plan Graph analysis, the study further evaluated the embedded spatial logic of UTRMBs. The results indicate that while buildings associated with different lifestyle types maintain relatively stable spatial control values, they diverge in integration and depth values due to variations in spatial openness and functional complexity. These findings further confirm that spatial transformations are not random, but structurally correlated with the lifestyle orientations of migrants.

In addition, the divergences between urban-to-rural migrants and local rural residents in their spatial value orientations reveal a form of “cultural reversal.” While local villagers increasingly adopt modern concrete constructions, many migrants consciously preserve or revive traditional elements such as timber structures, courtyard layouts, and gable roofs. Although these design choices are often driven by aesthetic or experiential motivations, they contribute, to some extent, to the preservation of traditional spatial values. However, not all modifications produce positive outcomes. Certain transformations led by migrants, due to limited understanding or excessive commercialization, may disrupt the rural landscape or weaken the symbolic continuity of place. In many traditional villages, as exemplified by the cases examined in this study, the proliferation of cafés, studios, and guesthouses under the influence of urban-to-rural migration suggests that rural architecture is evolving toward multifunctionality, a process that has introduced significant spatial tensions. The shift from residential to commercial uses may alter the traditional rhythms of village life and challenge community expectations regarding privacy and the maintenance of social order. Moreover, the stylization of rural landscapes to cater to urban consumption risks transforming “living heritage” into a performative landscape.

Compared with the lifestyle migration widely examined in European and American scholarship and the “return to rural living” movement in Japan, the Chinese case demonstrates a dual logic in which state-driven policies intersect with individual strategies. As a result, urban-to-rural migration in China is not merely a lifestyle choice but also an exploration of rural spatial renewal shaped by specific socio-institutional contexts, reflecting the institutional complexity of China’s urban–rural society. The typological analysis conducted in this study not only reveals the diverse pathways through which urban-to-rural migrant buildings contribute to the preservation and transformation of traditional values, but also provides concrete insights for rural planning and design practice. These spatial–lifestyle typologies can serve as an identification tool within rural planning, enabling planners to better understand the distinct spatial demands of different migrants and to formulate more targeted strategies for public facility allocation and overall village layout. At the level of migration governance and policy, the variations in spatial practices highlight differences in cultural identity, economic objectives, and lifestyle orientations, thereby fostering greater diversity in the value orientations of rural planning and design. Furthermore, this study emphasizes that urban-to-rural migrants represent an indispensable social group in the shaping of rural communities. Planning and design should therefore consider the needs of both original villagers and migrants, while mediating conflicts of interest and spatial rights in order to promote integration and coexistence. Given their urban backgrounds, migrants often possess higher cultural capital, broader social networks, and stronger resource mobilization capacities, which can be harnessed as valuable forces for rural development. Approaches such as participatory planning can both leverage these capacities and facilitate migrants’ integration into the local environment. Finally, migrant dwellings and their surrounding spaces often extend beyond residential functions to incorporate commercial and public roles, thereby generating new nodes of spatial vitality within villages. Rural planning and design should recognize and integrate these emergent spatial structures, seeking more effective ways to activate village life and to support the ongoing evolution of rural living realities.

Ultimately, this study demonstrates that urban-to-rural migration should not be understood merely as a demographic movement but as a complex socio-spatial process. Through everyday practices, spatial behaviors, and architectural expressions, it reconstructs traditional values and notions of “rurality,” making it a critical issue in rural spatial governance. Accordingly, the academic contribution of this research lies in addressing the phenomenon of urban-to-rural migration from a building-scale perspective, revealing the coupling between the spatial configuration of UTRMBs and migrants’ lifestyle practices, and further examining the role of migrants in sustaining traditional rural values. On the practical level, the findings provide new perspectives, as well as actionable insights and pathways for rural planning, architectural renewal, and cultural heritage preservation.

5. Conclusions

This study examined the spatial practices and transformative impacts of urban-to-rural migration in China, focusing on 51 urban-to-rural migrant buildings (UTRMBs) across three villages in Zhejiang Province. By integrating architectural surveys, interviews, and spatial and behavioral analysis, the study investigates how migrants reshape rural built environments while negotiating the preservation and reinterpretation of traditional architectural and lifestyle values. In doing so, it highlights the spatial agency of migrants not only as users and modifiers of space, but also as actors in the continuity—or disruption—of vernacular heritage.

Building on the architectural and lifestyle features of traditional dwellings (

Section 3.1), the study first establishes a foundational understanding of spatial traditions embedded in vernacular forms. This baseline enables a more nuanced assessment of the spatial interventions undertaken by migrants. The comparative analysis of morphological transformations (

Section 3.2), resource accessibility and spatial positioning (

Section 3.3), spatial–behavioral clustering (

Section 3.4), and spatial syntax of representative UTRMBs (

Section 3.5) demonstrates diverse transformation patterns, typological profiles, and spatial–lifestyle couplings.

Methodologically, the study contributes a structured and replicable analytical framework—the “space–migrant coupling model”—which incorporates five key dimensions: spatial preference, resource accessibility, building transformation, spatial composition, and lifestyle practice. By applying principal component analysis and K-means clustering, this study identifies six representative lifestyle–spatial types. This analytical model offers a transferable tool for comparative studies of rural spatial change in both Chinese and international contexts. This framework extends beyond China’s institutional context to reveal a generalizable mechanism of rural spatial transformation in post-urban societies.