1. Introduction

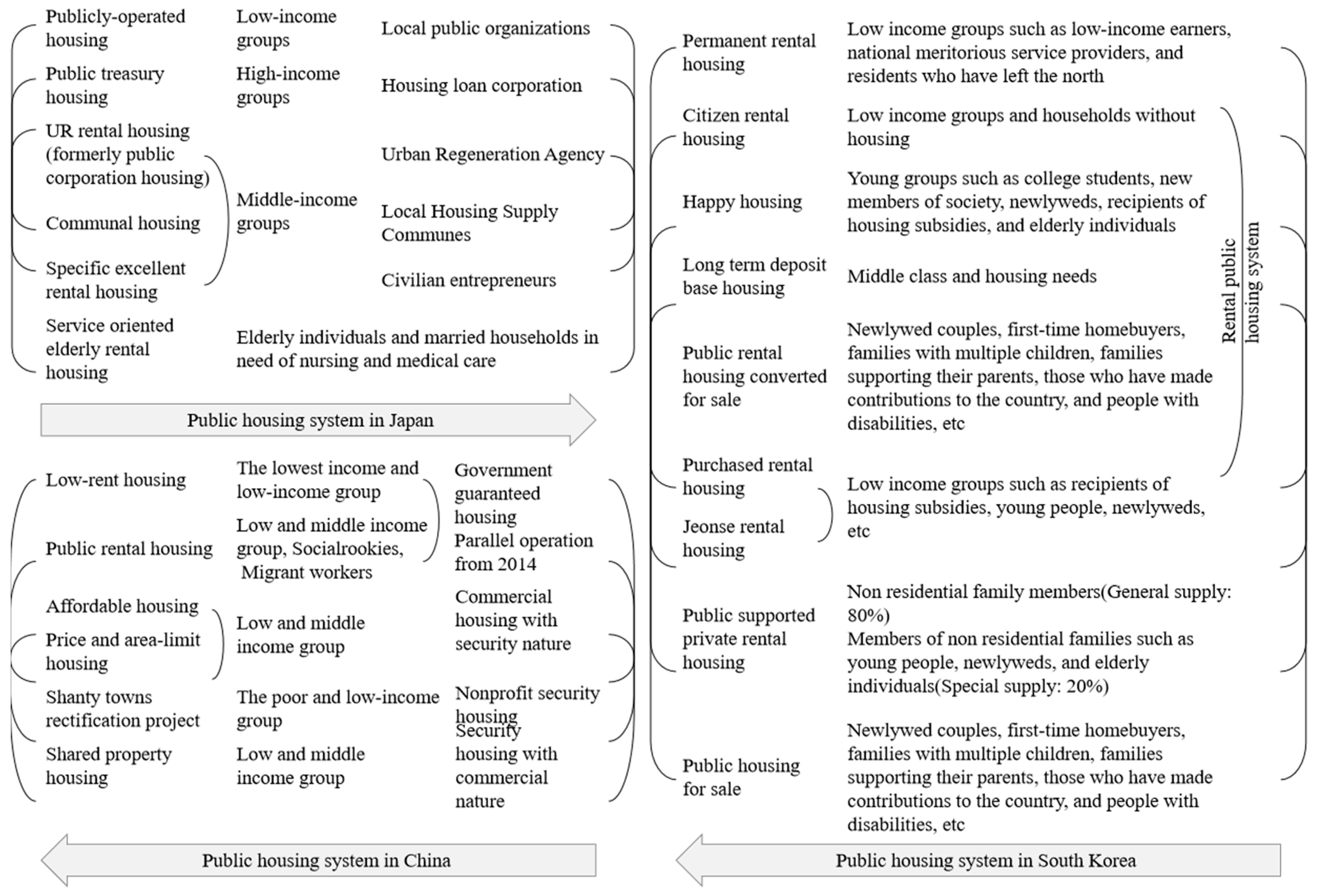

Since the introduction of the housing supply models such as affordable housing and low-rent housing with social security nature in 1994 and 1998, respectively, the development of China’s indemnificatory housing, which is the general term for all types of public housing in China, and equivalent to public housing in countries like Europe, America, Japan and South Korea, has been relatively slow [

1,

2,

3]. It was not until 2010 that a new model of public rental housing aimed at addressing the housing problem of the “sandwich class” in cities emerged, and the supply system of indemnificatory housing was further improved. However, in the context of the continuous increase in urban population, the construction and supply of indemnificatory housing still face many challenges. Since the implementation of the “12th Five-Year Plan”, the Chinese government has continuously emphasized the strengthening of the intensity of indemnificatory housing construction and has been committed to expanding the supply scope of indemnificatory rental housing. In the report of the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, it further clarified the goal of “accelerating the construction of a housing supply system led by the government, supplemented by the market, and emphasizing both renting and purchasing” [

4,

5]. Therefore, indemnificatory housing has become an important social policy issue in China at present.

With the continuous advancement of urbanization, the urban construction model is gradually shifting from extensive to refined. The residents’ demands for living environments have also risen from basic housing needs to the pursuit and yearning for living quality [

4]. The Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development emphasized the importance of building “Better Housing” (high-quality houses that are safe, comfortable, green, and intelligent) at the end of 2023, and further clarified the policy orientation of transforming indemnificatory housing into “Better Housing” at the beginning of 2024. Regarding the construction of “Better Housing”, the concept of building longevity in architecture was proposed, including strategies such as safety, durability, and flexible space design, as well as guidelines for enhancing elderly-friendly accessibility design and intelligent security systems. However, the current analysis of the unit plan spatial composition of indemnificatory housing in China reveals numerous challenges and opportunities [

6,

7,

8]. For instance, the average area of indemnificatory housing is usually limited to less than 60 square meters, and at most it can only constitute a two-bedroom layout, which makes it quite challenging to meet the housing needs of families with more than three members. Therefore, during the design stage of indemnificatory housing, it is urgent to comprehensively consider the actual needs of residents, their daily behavior patterns, and possible future changes in family structure, and precisely optimize the spatial layout and dimensions [

1,

8].

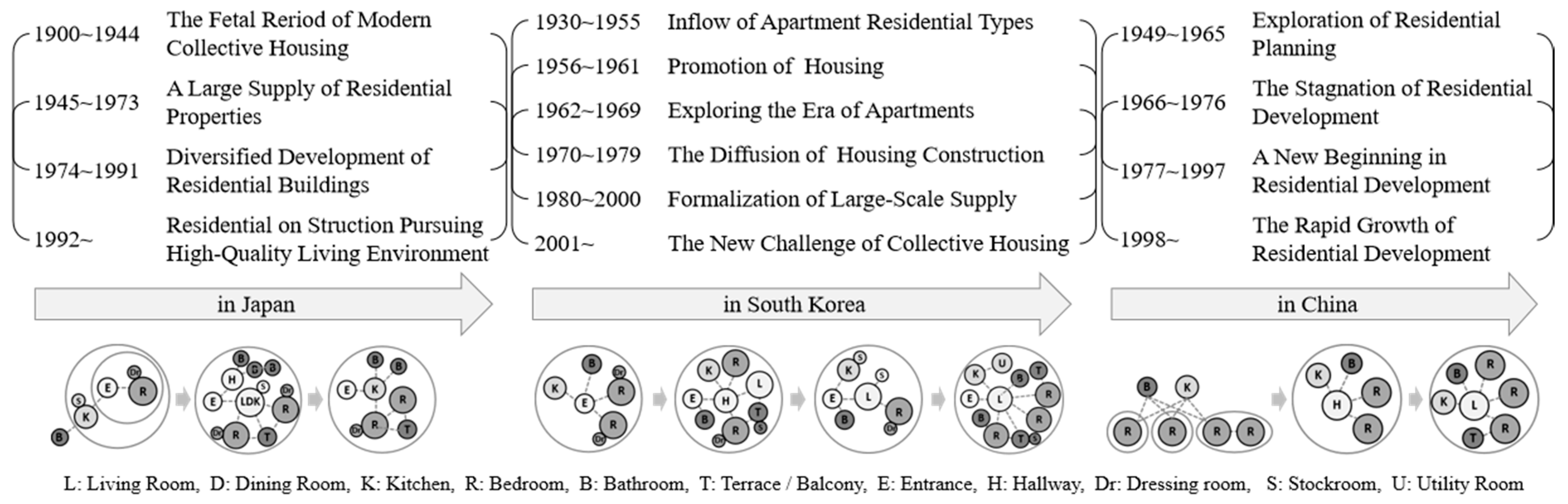

In contrast, Japan has gradually implemented the standardization process of public housing since the 1950s. Particularly notable is that since 1955, with the strong support of the government, the housing complexes constructed by the housing corporations have evolved over the years and have become the core component of Japan’s public rental housing system—UR rental housing, providing housing security for the middle-income group. Since the 1970s, Japan’s housing policies have undergone a transformation from focusing on quantity guarantee to improving the quality of housing. During this process, along with the continuous construction of high-quality housing and the unremitting pursuit of a superior living environment, UR rental housing gradually developed into a model of high-quality living environment in the public rental housing sector [

9,

10,

11]. Especially in the era of housing stock, the construction of UR rental housing mainly relied on the renovation of old residential areas, which further highlighted the new trend in Japan’s public housing construction [

4].

Following Japan, South Korea began to formally implement the public housing policy in the early 1960s and continuously refined and adjusted its construction and supply system. Especially since the early 1980s, after the South Korean government implemented standardized management of the rental housing market, various supply institutions and models have promoted the emergence of multiple forms of public housing, forming the current extensive and diversified public housing supply system [

12]. Especially under the dual drive of housing policies and the market economy, the space design of unit plans in South Korean public housing have successfully achieved the requirements of a high-quality living environment. For example, it can not only meet the needs of multi-person households for three-bedroom units, but also demonstrate high flexibility in terms of area and space utilization.

In view of this, under the background of “people-oriented and comfortable living”, combined with the concept of “Better Housing”, an in-depth analysis and comparison of the development and unit plan spatial composition of public housing in China, Japan and South Korea is of extremely important practical guiding significance for the future development direction of China’s indemnificatory housing as well as the optimization of living environment and spatial structure.

Although numerous domestic and international scholars have investigated the development of China’s indemnificatory housing from various disciplinary perspectives and provided corresponding empirical insights, existing research still exhibits certain limitations in terms of disciplinary scope, research methodology, and the presentation of findings. For example, Liao and Yoo [

3,

10] have conducted in-depth analyses of public housing policies in individual countries, such as France and Japan, from a policy analysis perspective, aiming to provide references for the evolution of China’s indemnificatory housing policies. From the perspective of public housing supply systems, Cao, Lee and Chen [

11,

13,

14] have conducted comparative studies between China and Japan, as well as China and South Korea, offering guiding suggestions for the further development of China’s indemnificatory housing supply system. Additionally, scholars including Zhou, Tian, Chen, Li, and Jin [

4,

5,

6,

9,

15] have focused on policy research, shifting their analytical frameworks toward comparative studies of international models of public housing development across multiple countries, with the objective of offering global policy references for China’s indemnificatory housing development.

In contrast to the extensive policy-related research, scholarly discussions centered on the floor plan design and spatial configuration of public housing units remain relatively limited. Scholars such as Li and Guo [

16,

17] have conducted detailed analyses of typical indemnificatory housing unit plans in the Lingnan region through comprehensive plan reviews and on-site investigations. They have proposed design strategies aimed at improving residential comfort by addressing issues related to unit layout, development trends, and traditional living patterns. Li [

18] has explored the minimum area and functional space dimensions of indemnificatory housing units under the premise of ensuring living quality. While these studies offer valuable guidance for optimizing the spatial design of China’s indemnificatory housing units, they exhibit certain limitations in terms of methodological rigor and the clarity of result presentation.

Based on this, in the previous studies [

1,

8], the researcher comprehensively considered the public housing policy system and the cultural context of residential practices, and used the architectural typology analysis, a method slightly employed by Zhou [

19] in the Comparison Analysis of Unit Plan Characteristic in Collective Housing in three East Asian countries, to investigate the spatial composition characteristics of public rental housing in China and South Korea, aiming to reveal how policy evolution and residential culture influence housing unit design. Building upon previous studies, in the current context where China is actively promoting the construction of indemnificatory housing and striving to make it “Better Housing”, this study adopts a comparative framework encompassing China, Japan, and South Korea. It integrates theoretical perspectives such as housing policy and residential culture and applies architectural typology analysis to explore how different policy systems and cultural contexts shape the spatial characteristics of indemnificatory housing units. Furthermore, taking into account China’s unique socio-cultural conditions, this study aims to explore the implications for China’s indemnificatory housing from the dimensions of policy orientation, unit plan spatial composition, and cultural adaptability.

3. Overview of Typical Cases

In order to conduct a comparative analysis of public housing in China, Japan, and South Korea, this study selected the most representative and largest supply of public rental housing in each country as the research cases. Specifically, this study focuses on the public rental housing demonstration projects developed by Beijing Public Housing Center [

35]; the national rental housing and permanent rental housing projects developed by LH (Land and Housing Corporation) [

36] and SH (Seoul Housing Corporation) [

37] in South Korea, and the UR rental housing projects owned by Urban Renaissance Agency [

38,

39] in Japan. At the same time, considering the development history of public rental housing in China, the completion times of the selected cases mainly fall within the 2010s. In both China and South Korea, the housing shortage problem for low and middle-income groups still exists, and public housing is in a stage of rapid development. Therefore, the supply targets of Chinese public rental housing and South Korean permanent rental housing, and national rental housing are similar, both mainly targeting the middle and low-income groups. In Japan, as a country that has entered the era of housing stock, the core supply type of public housing in Japan—UR rental housing—is mainly targeted at middle-income groups. The analysis of the spatial composition of the unit plan can provide more powerful theoretical support and practical guidance for the spatial layout optimization of China’s indemnificatory housing. To facilitate the comparative analysis, this study selected nine cases as research objects for each country (see

Table 1).

3.1. Construction Status of Public Housing

Given that the housing supply in Japan has reached a certain level, the number of new public housing constructions, including UR rental housing, has significantly decreased since the 2010s. The cases selected for this study are all projects completed before 2012, and most of them were renovated from old buildings. In contrast, South Korea and China started their public housing supply later and still face the problem of housing shortage at present. Especially in China, the housing problem for the middle and low-income groups is particularly prominent. Even in the 2020s, new public housing projects are still ongoing. Based on the differences in supply and demand, land area, and other basic conditions among the three countries, the scale of public housing development also varies. For example, UR rental housing complexes in Japan are usually small, generally not exceeding 1000 households; public housing complexes in South Korea are mostly between 1000 and 2000 households; while large public housing complexes with over 3000 households are also very common in China.

3.2. Building Form and Floor Count

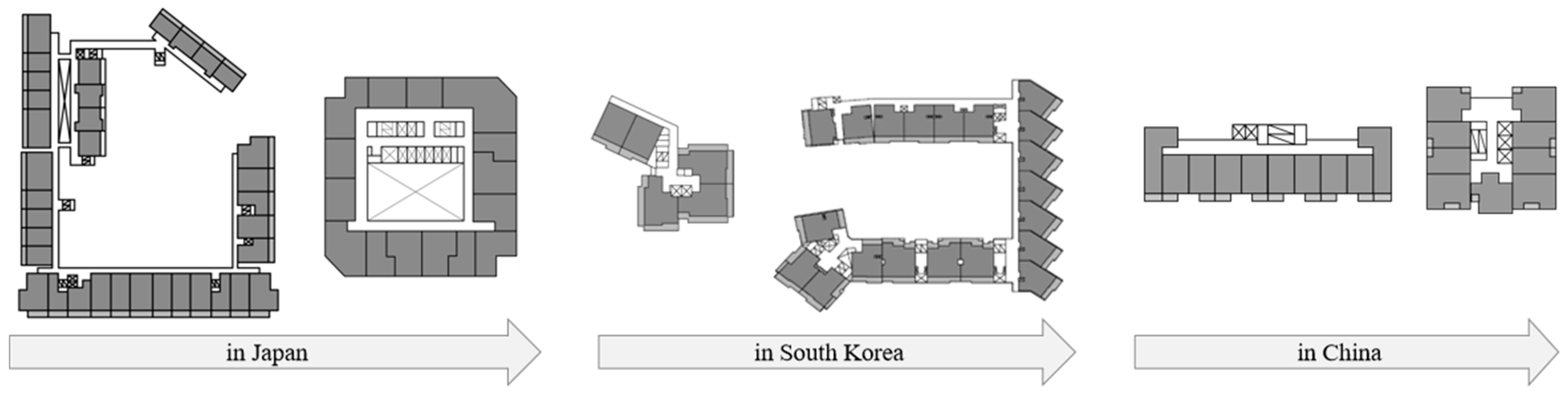

As shown in

Figure 3, there are significant differences in the architectural design of public housing among China, Japan, and South Korea. In Japan, apart from two super-tall towers, the buildings of UR rental housing complexes are mainly composed of 4 to 14-story mid-to-low-rise single-lane block buildings or mixed-type residential buildings. In South Korea, public housing complexes, except for the 25-story building of Seocgi Bogeumjari Housing Complexes Phase 3, most of the buildings have heights ranging from 10 to 21 floors. In contrast, the building heights of public housing complexes in China are generally higher. Apart from three complexes with the highest number of floors at 16, the buildings of the other six complexes are all over 25 floors. Moreover, the residential buildings in China are mainly composed of block buildings and mixed-type residential buildings, including L-shaped and other tower-type designs. The residential building designs in South Korea are more diverse. Besides block buildings and mixed-type residential buildings, various forms of tower-shaped and mixed-type buildings can also be seen. In addition, unlike the public housing complexes in China, which present various forms such as single-lane, middle-lane, and core tube types, the public housing residential buildings in South Korea mostly adopt single-lane designs.

3.3. Form and Composition of Residential Communities

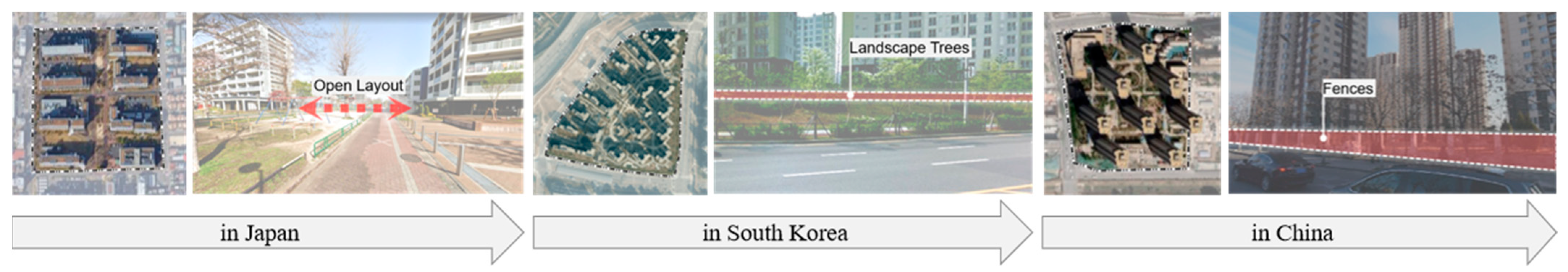

There are significant differences in the planning and design of residential areas among China, Japan, and South Korea (see

Figure 4). Among the 9 residential communities in China, only the Yanbao Guogongzhuang Jiayuan and the Yanbao Beijiao Jiayuan, which were completed in 2017 and began occupancy in 2020, respectively, adopted the block system planning (i.e., an open living mode without fences or isolation areas), while the remaining communities were all designed as closed ones [

40]. The planning of residential communities in South Korea usually surrounds the park area with fences, barriers, or landscape trees, presenting a semi-open structure that is easy to enter and exit. In contrast, the planning of residential areas in Japan is influenced by Western residential community planning concepts, mainly adopting an open layout. Especially, most residential communities are crossed and divided into several small blocks by urban road networks or urban parks, and even the completion times of each block vary, resulting in the construction period of the entire community possibly lasting several years. Moreover, unlike the designs in China and South Korea that tend to solve parking problems by utilizing underground space, Japanese residential areas, considering the hazards caused by frequent earthquakes, prefer to build above-ground parking buildings within the communities.

3.4. Types of Unit Plans

Given the differences in scale and development stage among public housing communities in China, Japan, and South Korea, the number of applicable types of unit plans also varies significantly, which in turn affects the distribution of shared frequencies. In China, the 9 selected case communities provide a total of 22,380 public rental housing units, involving as many as 71 types of housing layouts, with an average of 315 units sharing one type of unit plans. In South Korea’s 9 residential communities, the total number of households is 11,440, among which there are 6046 permanent rental housing units and national rental housing units, totaling 46 types of unit plans, with an average of 131 units sharing one type of unit plans. Although the shared frequency of unit plans in South Korea is lower than that in China, considering the smaller scale of residential areas in South Korea, the number of applicable unit plans is also relatively smaller. In contrast, Japanese residential communities are generally smaller in scale. According to the data provided by the UR Agency’s official website, the 9 residential communities offer a total of 6596 UR rental housing units, but there are more than 237 types of unit plans, with each type of unit plans being shared by a maximum of 28 households. Although the total number of UR rental housing units in Japan is similar to that of permanent rental housing and national rental housing in China and South Korea, the number of applicable unit plans is more than five times that of South Korea. This indicates that, unlike the planning concepts of public housing communities in China and South Korea, which tend to plan more units with the fewest unit plan types, Japanese public housing communities tend to provide diverse and personalized unit plans, which is attributed to the fact that UR rental housing projects are mostly the result of renovating and upgrading old buildings. For the classification of residential unit plans in the three countries, please refer to

Figure 5.

4. Spatial Composition Characteristics of Unit Plans

Based on the above generalization of architectural features, this study focuses on exploring and analyzing the spatial composition characteristics of unit plans in the three countries from multiple dimensions, including the morphological features of unit plans, the layout mode of L.D.K. (living room–dining room–kitchen), the configuration strategy of bedrooms, the role of transitional spaces in spatial integration, the connection methods of balconies, and the spatial composition of bathrooms.

4.1. Morphological Features of Unit Plans

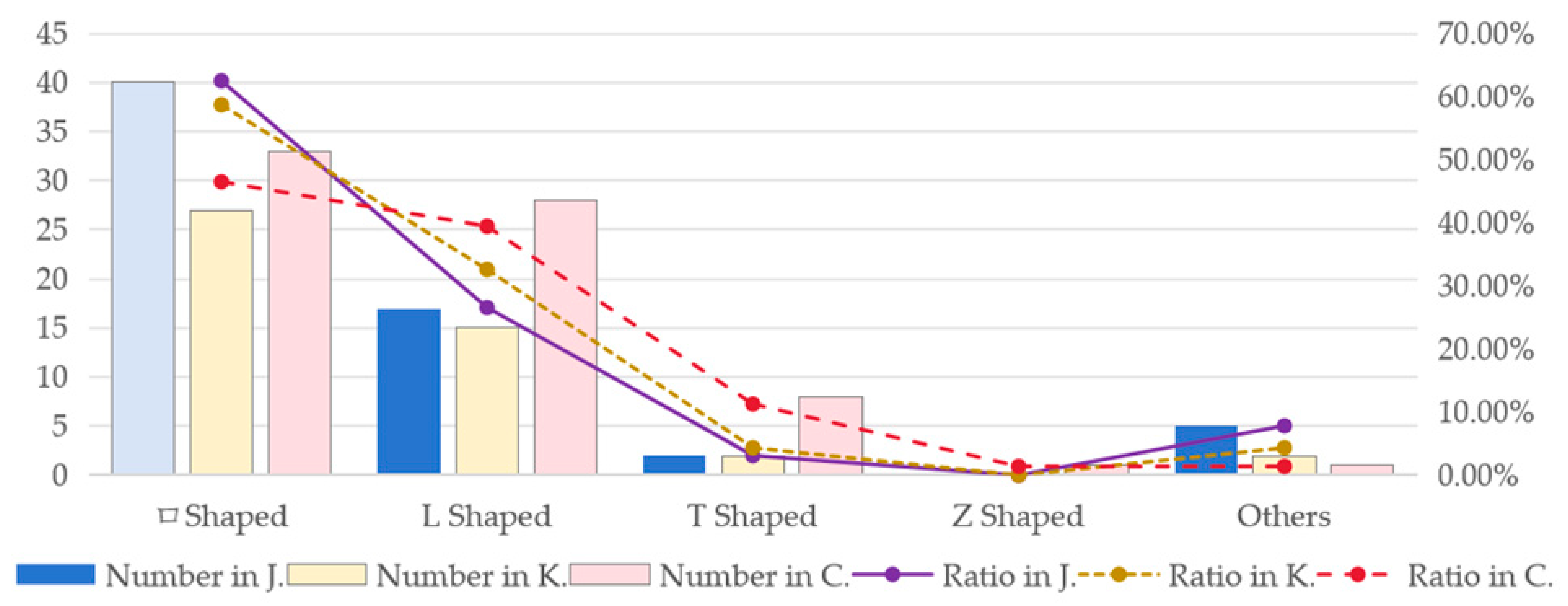

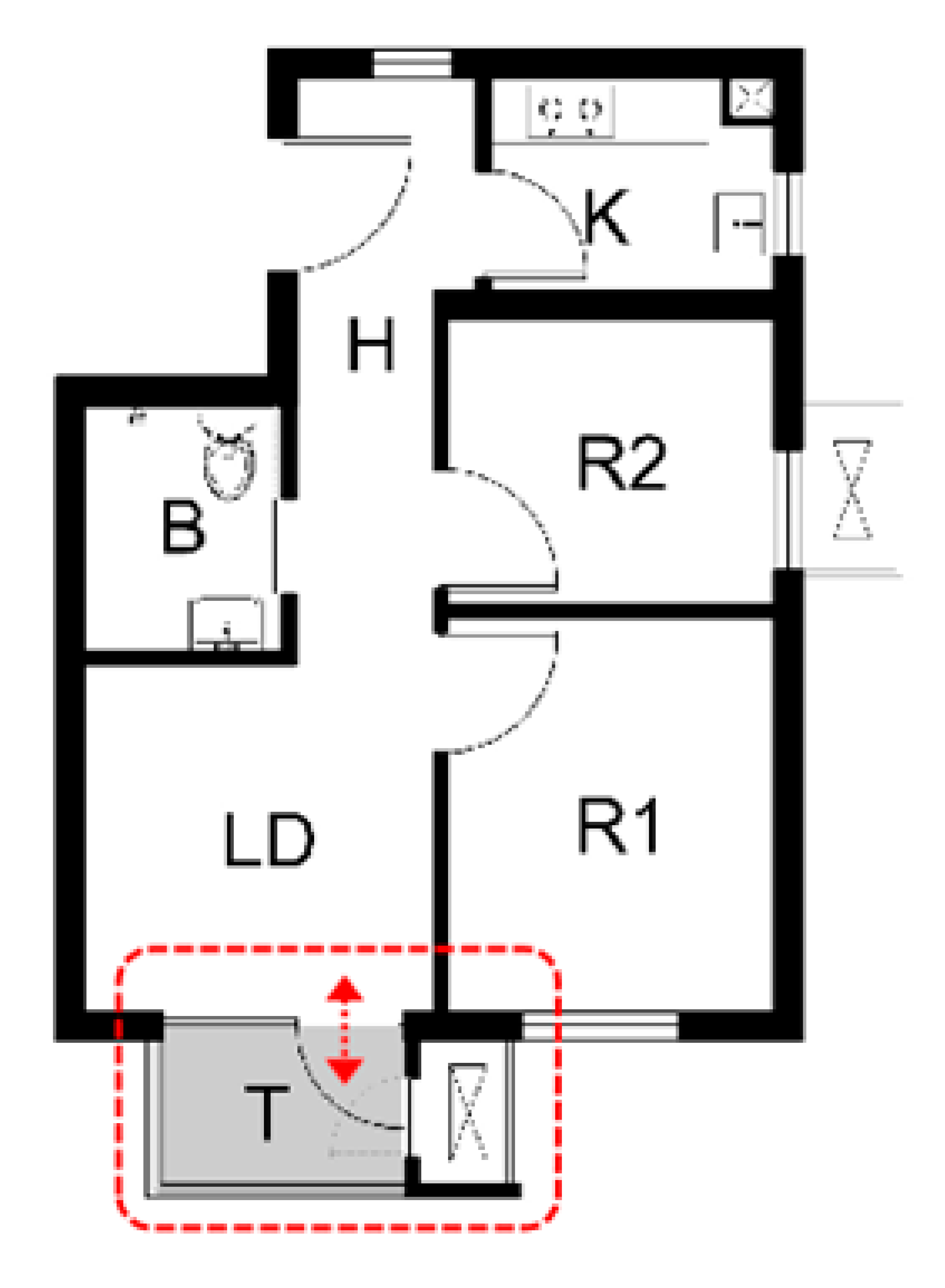

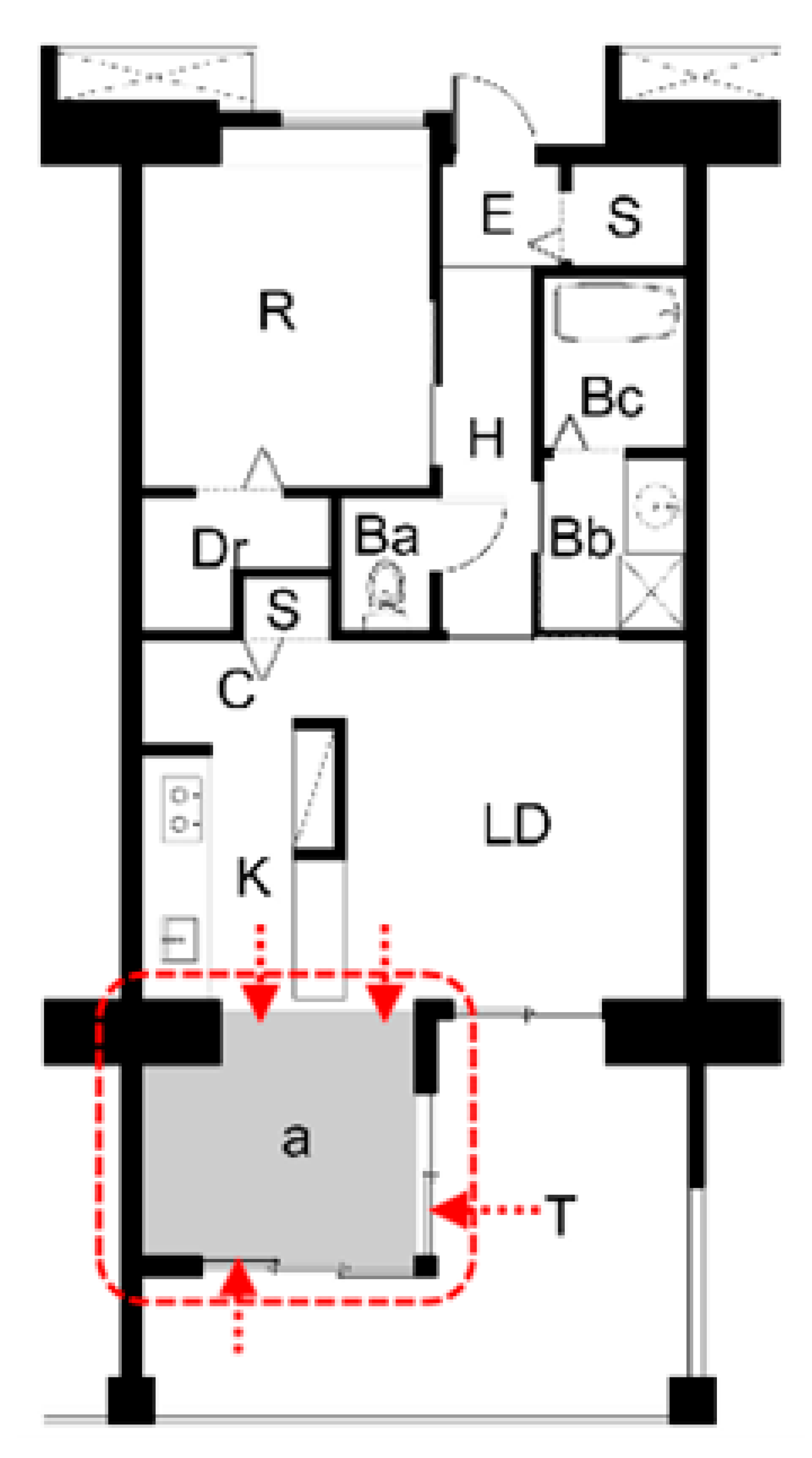

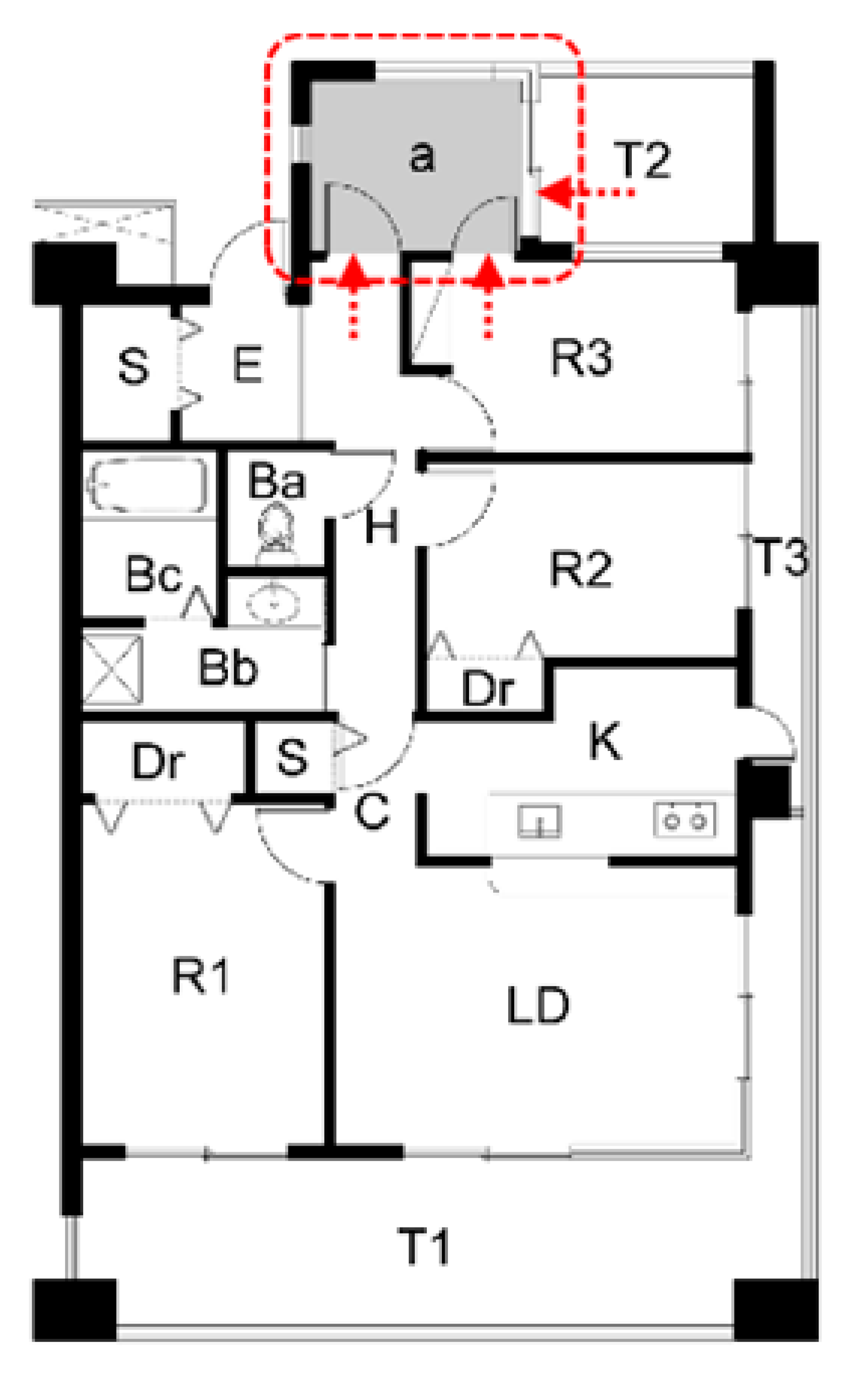

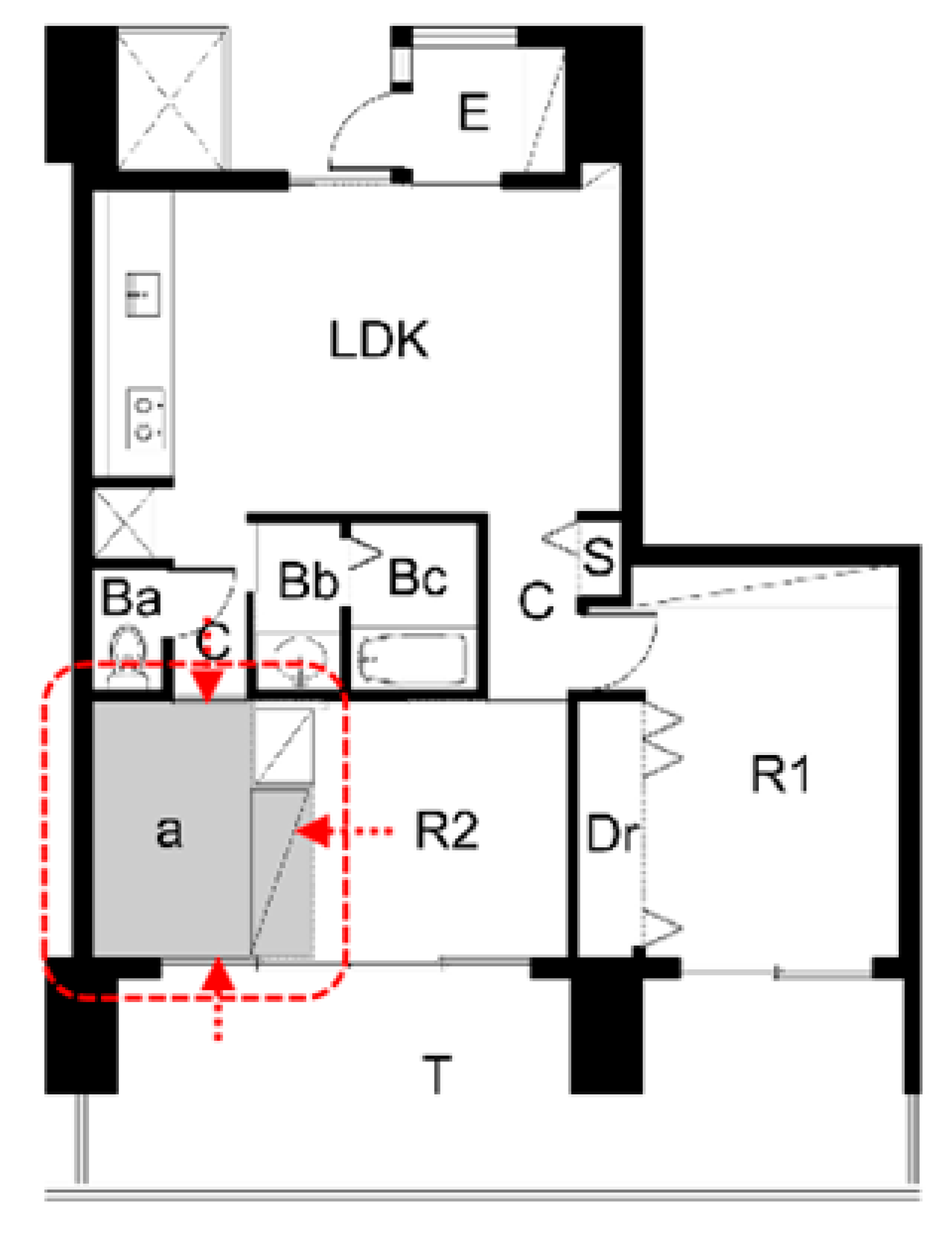

In the residential unit plan designs of China, Japan, and South Korea, the “口” shape and “L” shape layouts are mainly adopted, as presented in

Table 2. Although the specific forms of unit plans in each country may have slight differences, the “口” shape layout generally presents a feature close to a rectangle, while the “L” shape layout is typically characterized by the absence of one side of the rectangle. This phenomenon can be attributed to the layout characteristics of the public residential communities in these three countries, especially in the residential communities in the research cases, most of which adopt a corridor layout, resulting in the unit plans being arranged side by side along the corridor. Among them, the “L” shape floor plan can be regarded as a variation in the “口” shape floor plan, mainly presenting three types. Specifically, in order to achieve effective utilization of the space of the two unit plans within the limited modules, the two unit plans may appear in an overlapping L-shaped form, or be located at the end of the corridor, extending the part outside the convenient entry and exit area of the entrance door to the interior area of the unit plan, thereby forming an “L” shape, or due to the insertion of vertical transportation facilities such as stairwells or elevators, forming a specific deformation. In the unit plan forms of residences in Japan and South Korea, in addition to the common “口” shape and “L” shape layouts, sometimes T-shaped and other irregular unit plan forms may also appear. In China, in addition to the above forms, it is also common to have a Z-shaped form. Moreover, the irregular unit plans are mainly derived from the shape of the residential buildings, and the irregular unit plans of the three countries all present different morphological characteristics.

4.2. Layout Mode of L.D.K.

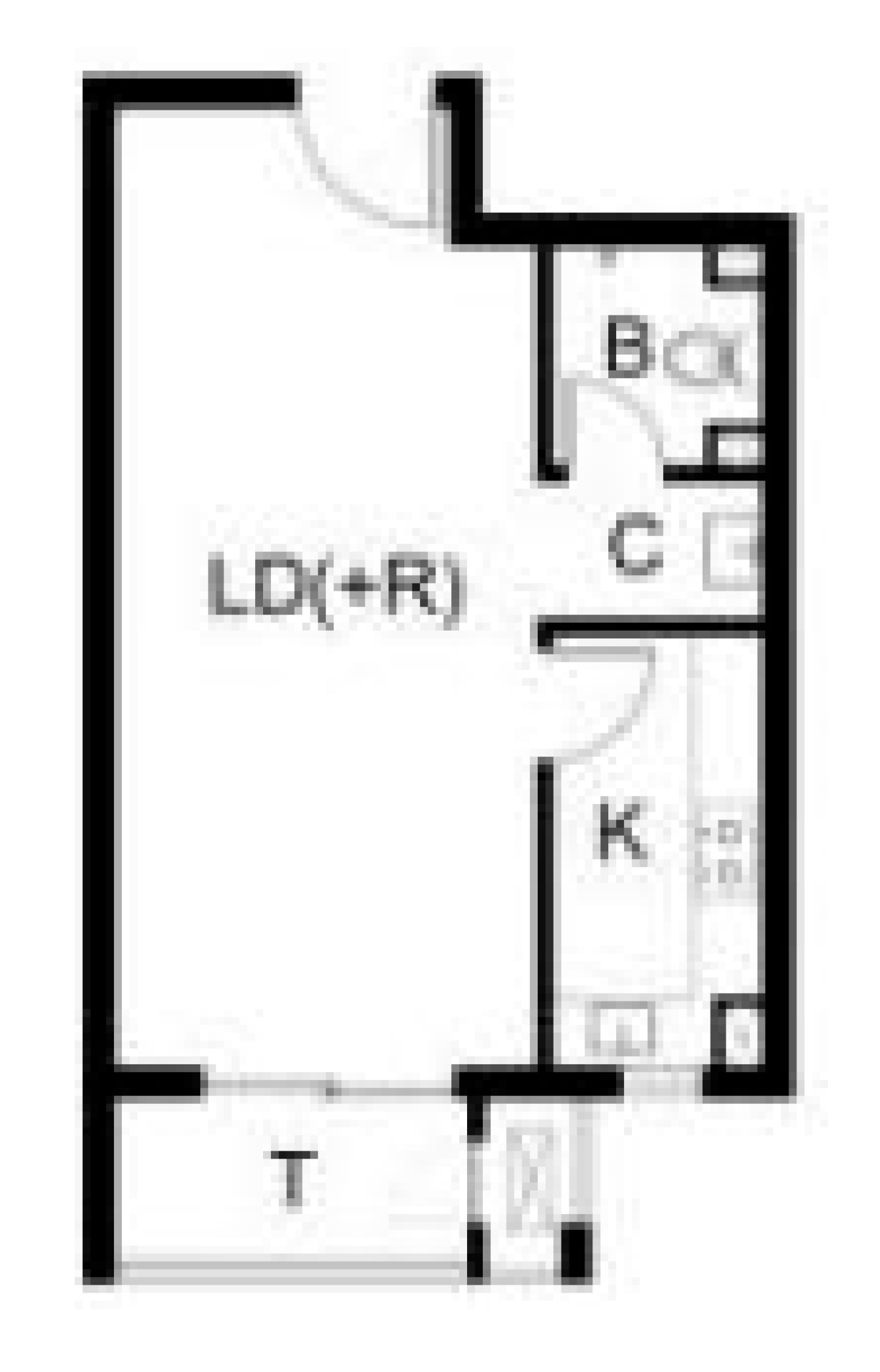

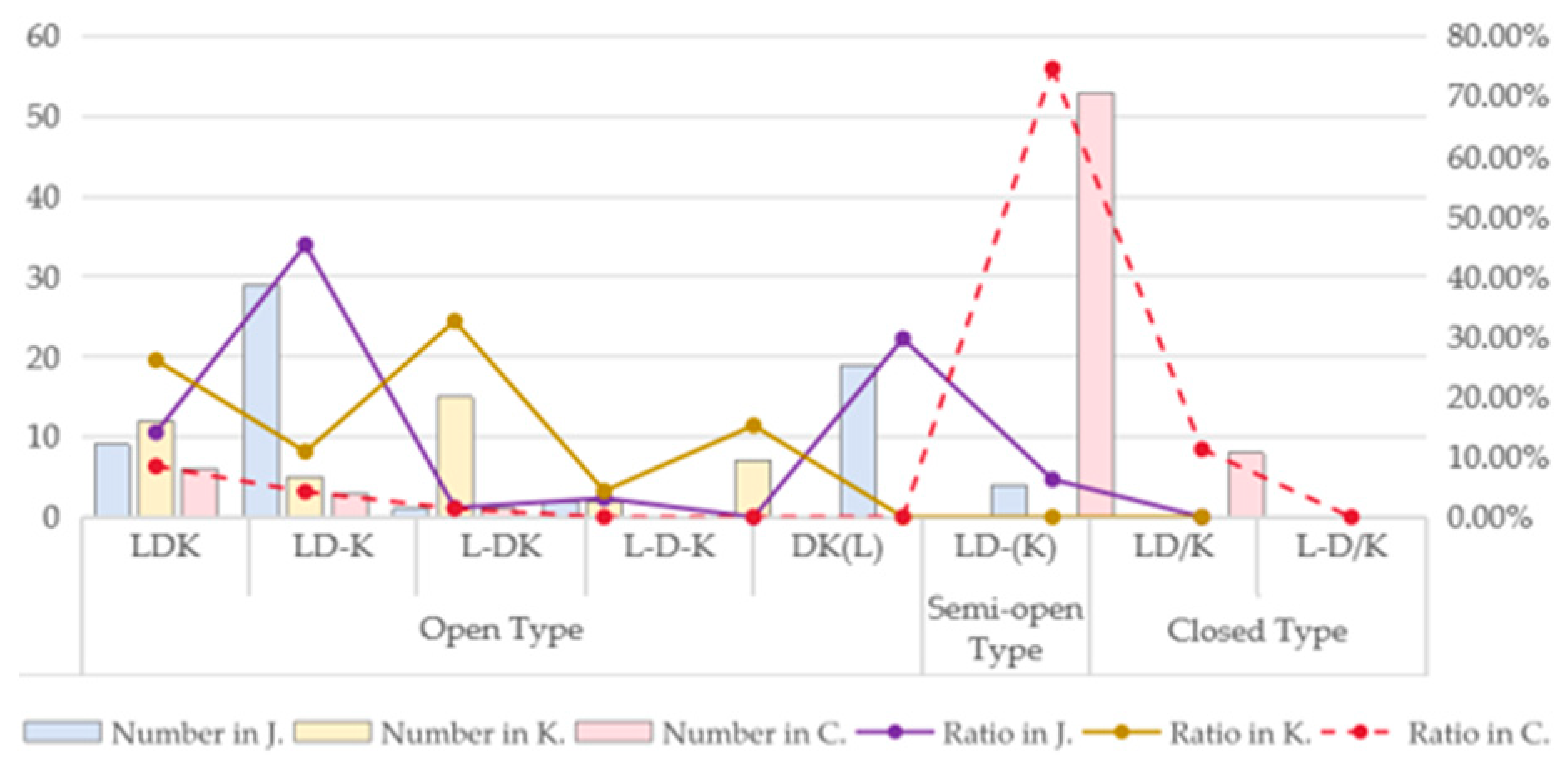

As shown in

Table 3, based on different kitchen configuration patterns such as open, semi-open, and closed, the types of L.D.K. can be further classified into eight categories. Japanese kitchens are mainly designed as open or semi-open, while Korean ones are mostly open, and in China, they tend to be closed. These differences mainly stem from the differences in the dietary cultures of the three countries, namely the Chinese dietary culture with rich oil aroma such as stir-frying or deep-frying, where Chinese kitchens are generally designed as closed, and this is also closely related to fire safety. Korean kitchens are mostly open, while Japanese kitchens are mainly open or semi-open, mainly because the layout pattern of Western open kitchens is suitable for the non-greasy and less oily dietary culture of Japan and Korea.

In Japan, the design of open kitchens mainly adopts the LD-K layout pattern, while in Korea, the L-DK and LDK layout patterns are more popular. In other words, the kitchen space in Japan is usually clearly separated, while the kitchen and dining space in Korea tend to be used together. Moreover, unlike the layout in Japan, the open kitchen design in Korea also commonly features DK(L) layout, that is, the bedroom is used as a living room function, and the kitchen and dining area share the same space. The planning of semi-open kitchens is unique in the residential floor plan design of Japan. As for closed kitchens, in Chinese L.D.K. layouts, LD/K is the main type, and in rare cases, L-D/K layout also appears. The closed kitchen layout in Japan is similar to that in China, mostly in the form of LD/K where the kitchen is independent, while in Korea, they prefer the L/DK form where the kitchen and dining space are combined.

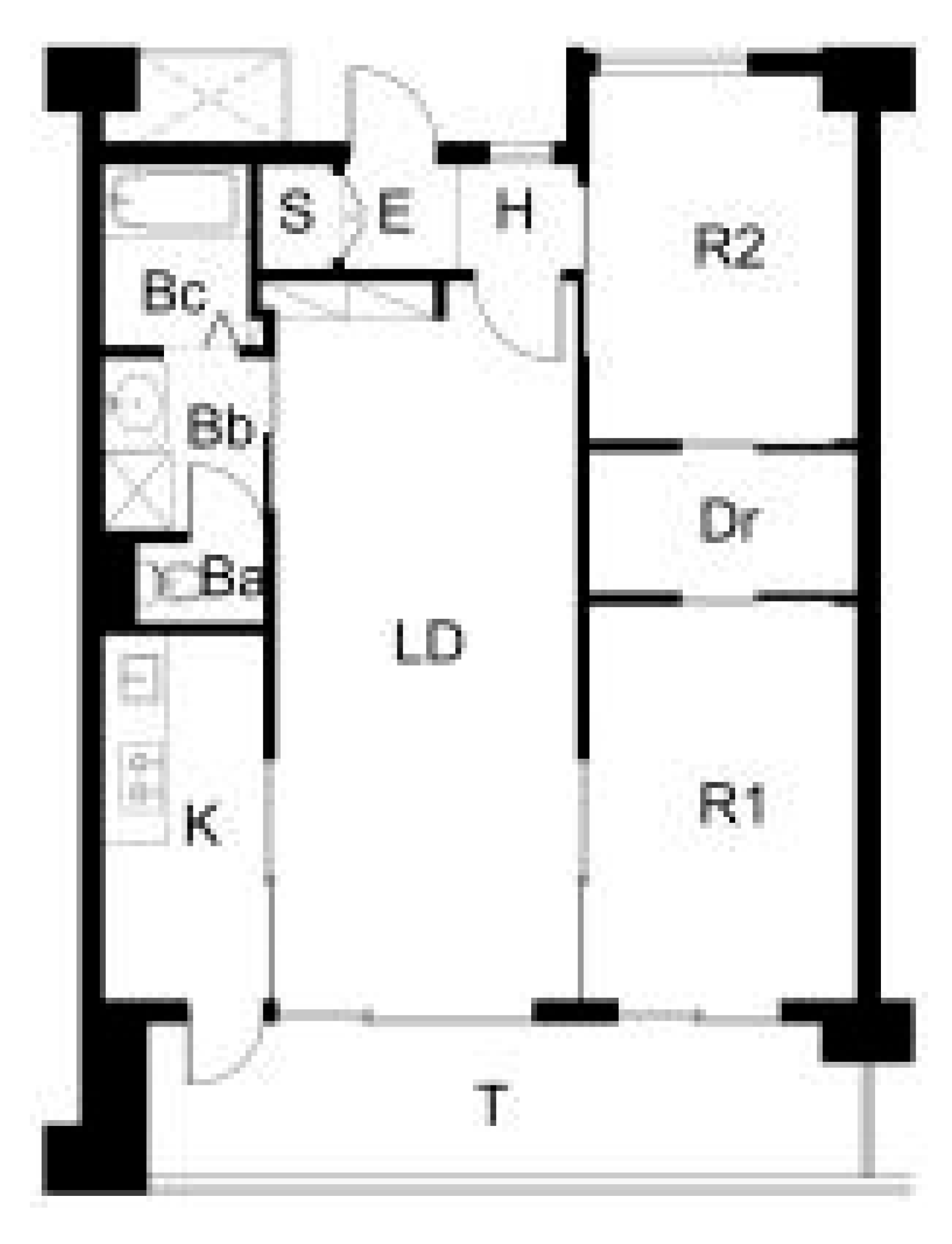

4.3. Configuration Strategy of Bedrooms

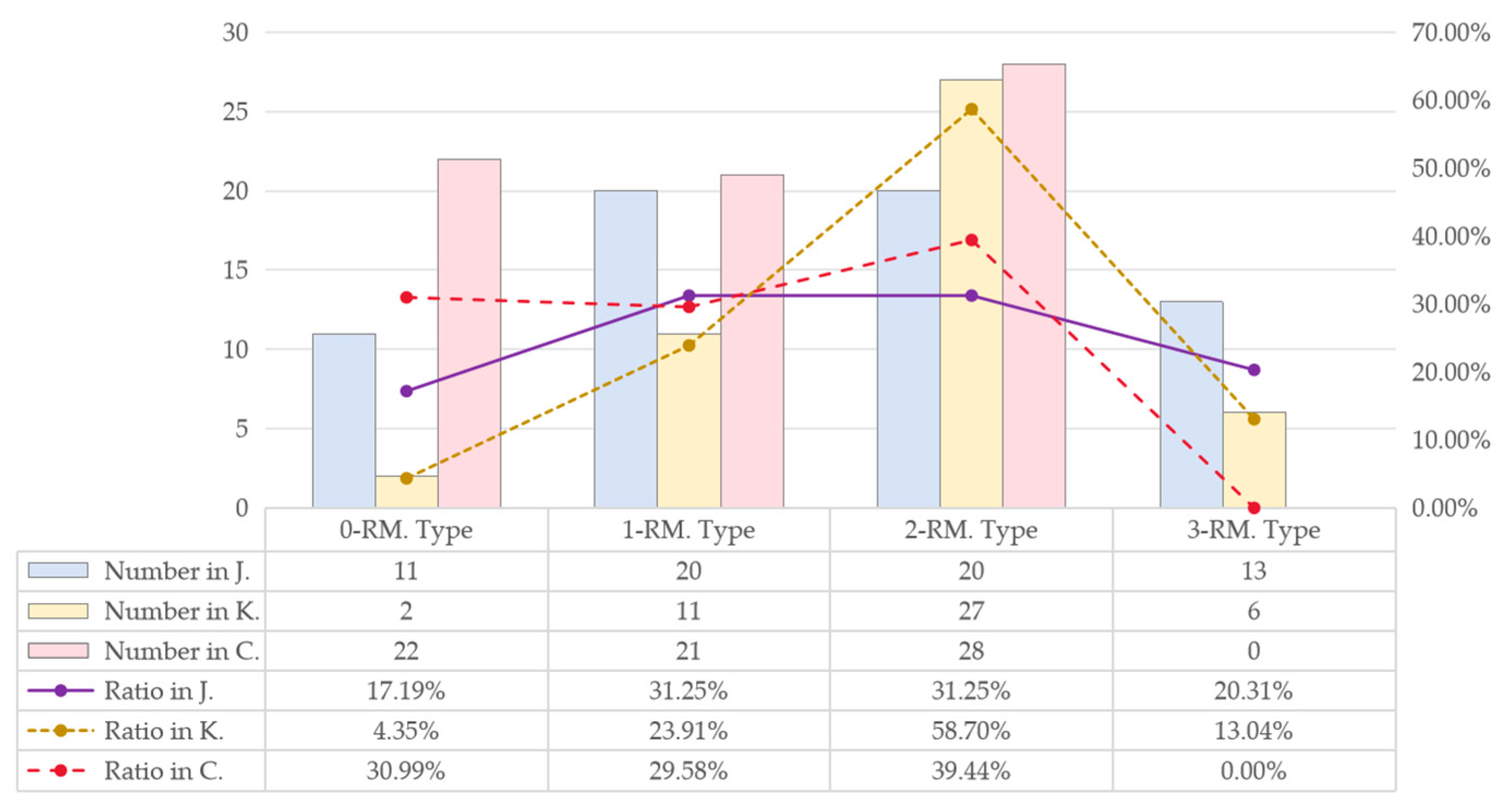

According to the analysis results of the unit plan types in China, Japan, and South Korea shown in

Figure 5, it is evident that in Japan, the two-bedroom and three-bedroom houses account for 51% of the total analyzed houses; in South Korea, the two-bedroom houses account for 58%, and the three-bedroom houses account for 13%; in China, the two-bedroom houses have the highest proportion, approximately 39%, and there are no three-bedroom houses. As presented in

Table 4, taking the two-bedroom houses as an example, both Japan and China have a dominant centralized layout with a proportion of about 60%, showing some similarities. However, the two-bedroom houses in South Korea are all centralized. In terms of layout patterns, the two-bedroom houses with centralized layouts in Japan and China share certain commonalities, that is, they generally adopt a layout form of two bedrooms side by side. In the dispersed two-bedroom layout, the two bedrooms in Japan are mostly arranged along the sides of the living room, separated by a bathroom and an entrance passage. In China, the two bedrooms prefer a symmetrical layout centered around the living room. In the three-bedroom houses, the layout methods in South Korea include dispersed and mixed types, each accounting for 50%. In Japanese three-bedroom houses, the mixed type dominates, with the centralized type and the mixed type each accounting for half. In conclusion, Japan and China are more inclined to prefer centralized bedroom layouts in the unit plan design, while South Korea prefers dispersed bedroom layouts. This difference is mainly related to the living habits and indoor activity flow lines of the people in the three countries. That is, Japan and China pay more attention to the separation of indoor activities between active and quiet areas, while South Korea tends to ensure the independence of individual privacy space.

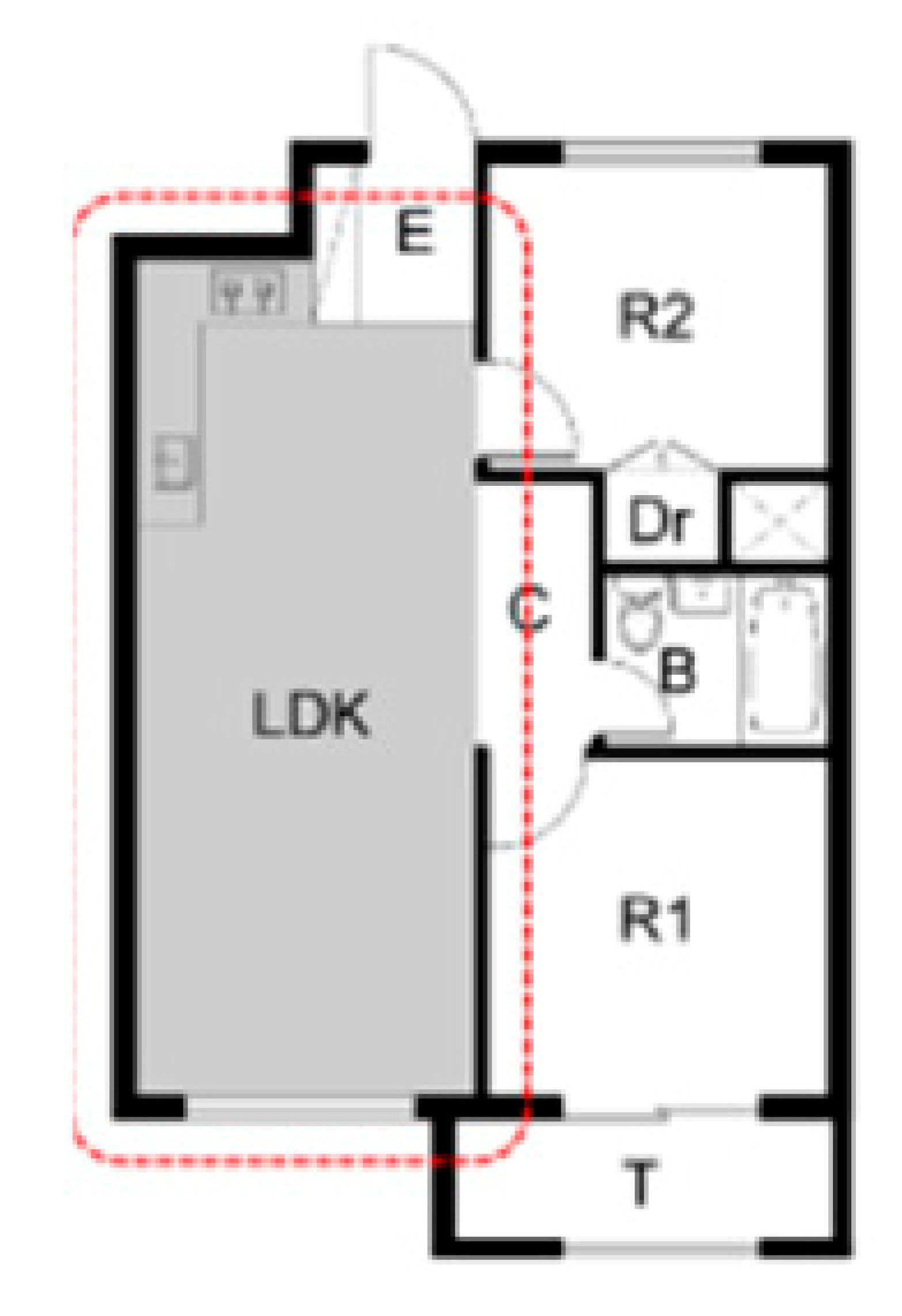

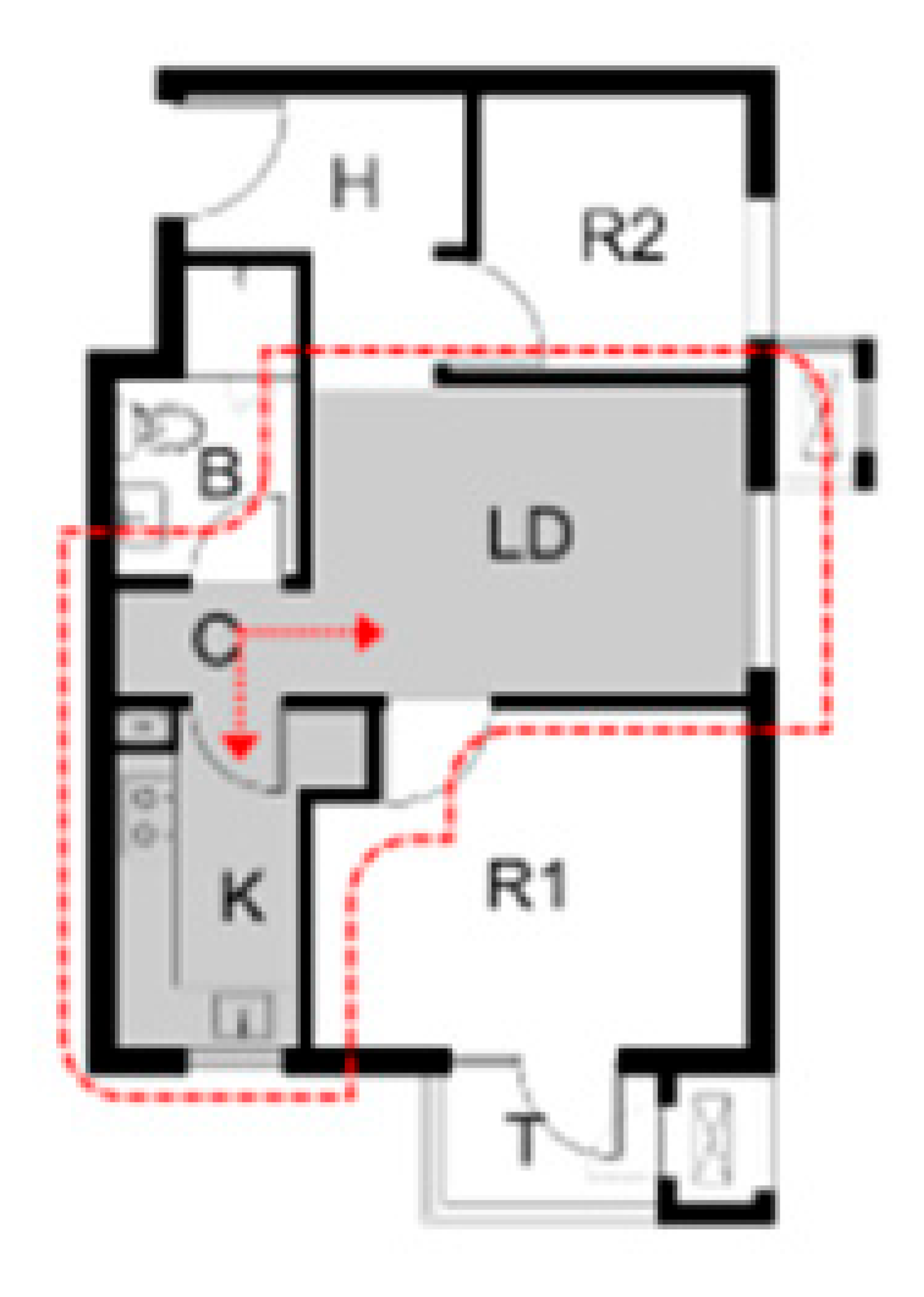

4.4. Role of Transitional Spaces in Spatial Integration

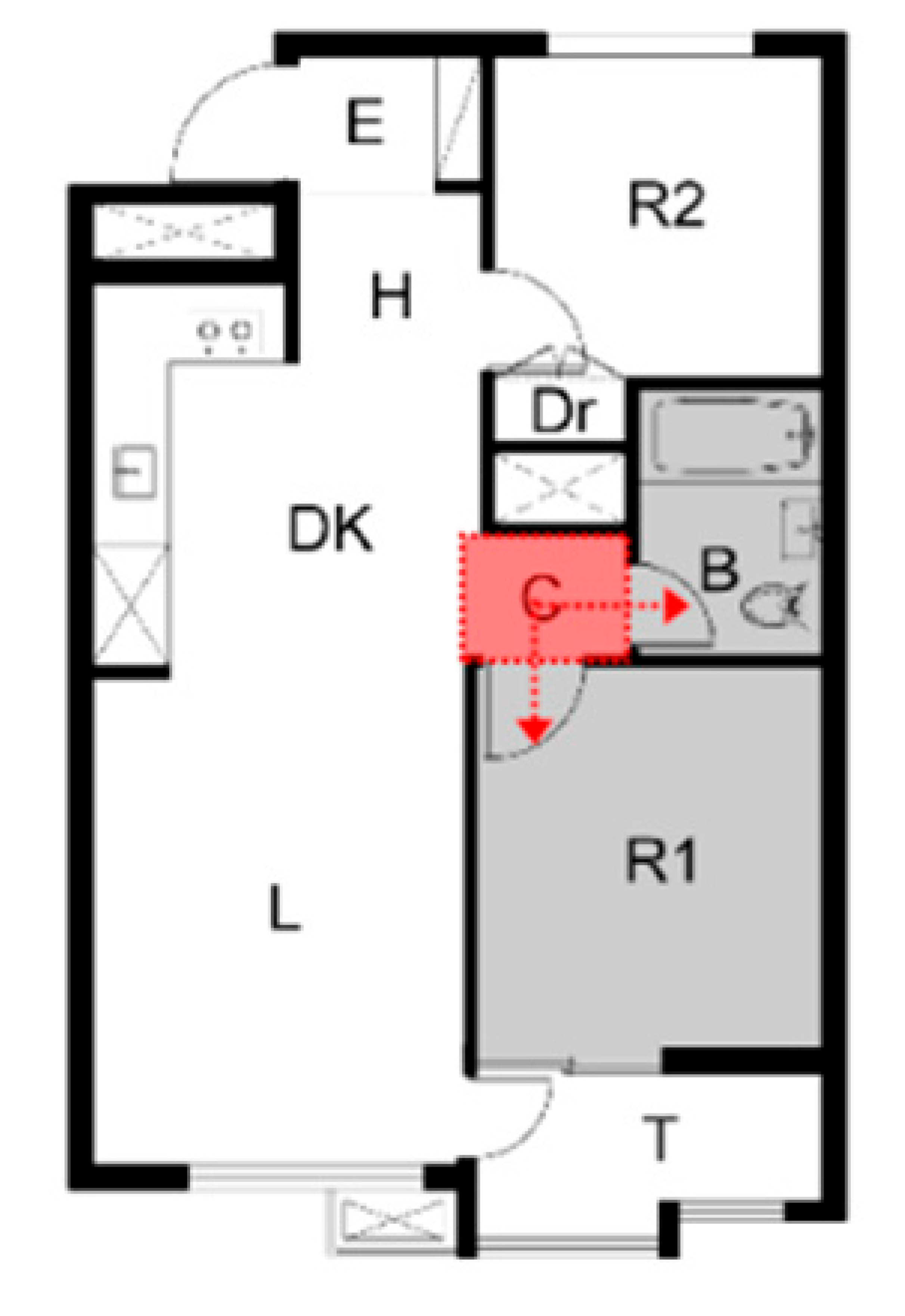

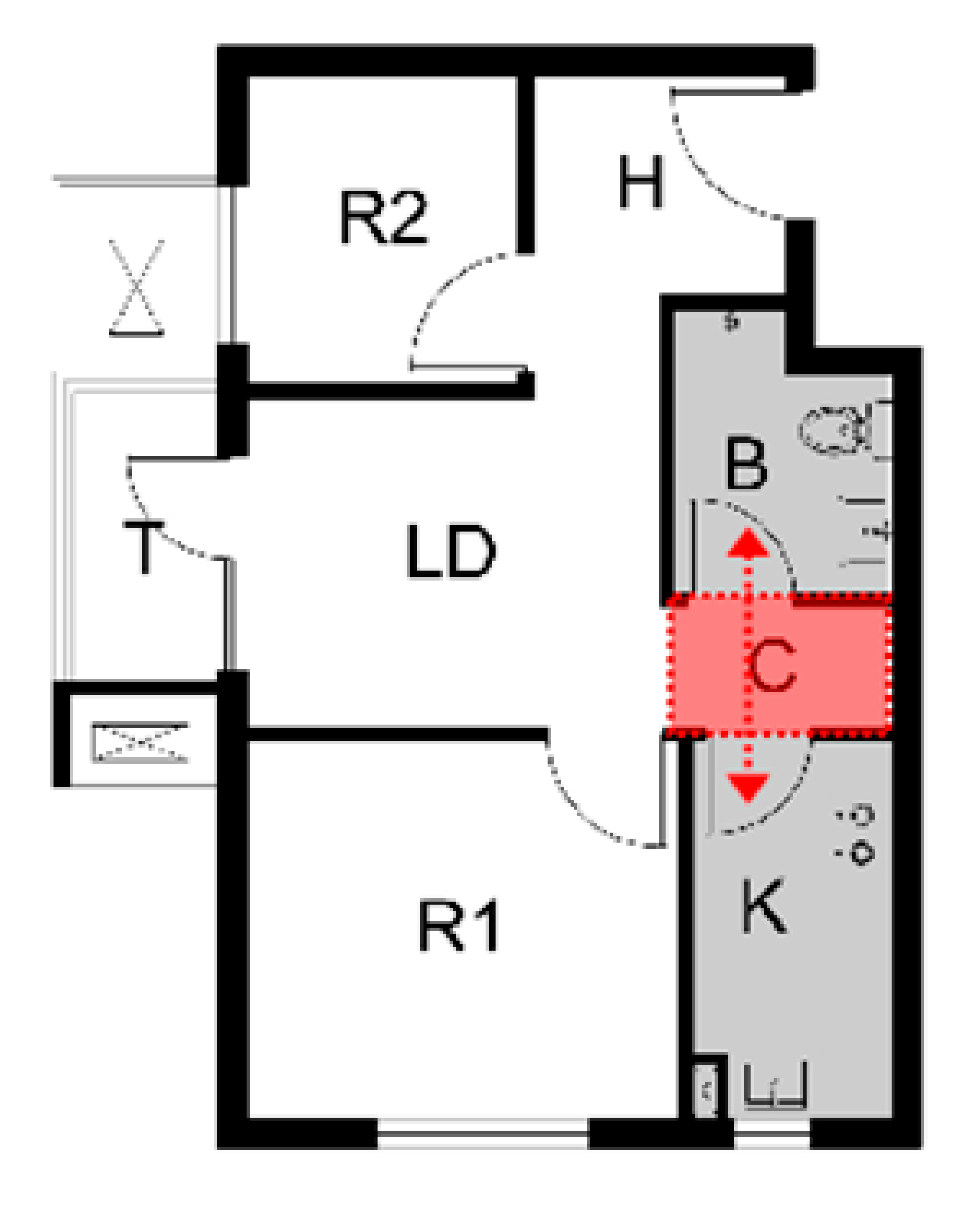

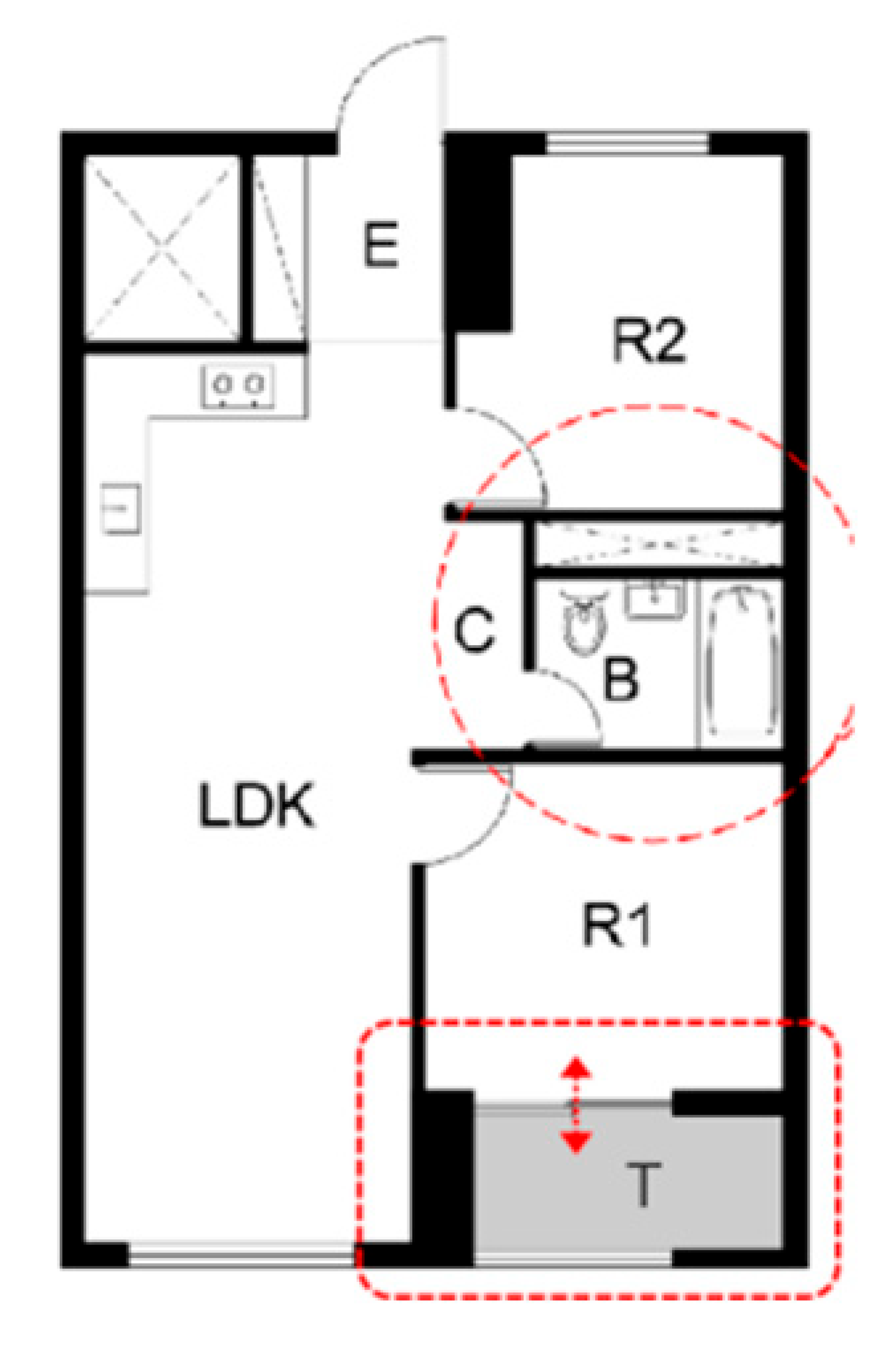

In the interior layout designs of China, Japan, and South Korea, the construction of transitional spaces such as entrance corridors (H) and internal corridors (C) shows certain commonalities (see

Table 5). Specifically, approximately 40% of the interior layouts in Korean and Chinese residential designs adopt the design of entrance corridors or internal corridors. In Japan, this proportion is as high as approximately 86% and 62%, respectively. In the design practices of Korea and China, the situation where the entrance faces the living room is relatively common. The entrance corridors usually serve as a buffer area in front of the living room and sometimes also function as a transitional space for bathrooms or bedrooms. Especially in Chinese residential designs, there is a lack of an independent foyer space, so the entrance corridor simultaneously fulfills the function of a foyer. In Japanese residential designs, in most cases, entering from the foyer requires passing through the entrance corridor to reach the living room. At this time, the entrance corridor not only connects the foyer and the living room but also serves as a transitional space between the bathroom and the bedroom. Compared to the designs of Korea and China, the entrance corridors in Japanese residential designs connect more functional spaces. As for internal corridors, in Japanese residential designs, they mainly serve as buffer areas for kitchens and other spaces. In Japanese residences, the situation where the bathroom and the kitchen are adjacent is relatively common, so the internal corridors play an important role in integrating these two spaces. In Korea, internal corridors are mostly located between the bathroom and the bedroom, serving the function of space integration. In China, internal corridors are usually located between the bathroom and the kitchen, not only integrating these two spaces but also possibly serving as a setting area for washbasins or refrigerators, and sometimes also as a buffer area between bedrooms, bedrooms and bathrooms, or independent spaces such as bedrooms, kitchens, and bathrooms. These differentiated integration relationships are deeply influenced by the living culture and habits of each country. For example, Chinese residential space design emphasizes the continuity of indoor and outdoor activities, so the design of entrance corridors is not prominent. However, in the planning of indoor activities, to save living room space and shorten the flow line, internal corridors are usually considered as transitional areas. Relatively, the living habits of Korea and Japan tend to separate indoor and outdoor activities, so their residential designs often have a sunken entrance space. Especially in Japan, a further channel section is added on top of the entrance space to ensure the complete separation of indoor and outdoor spaces.

4.5. Connection Methods of Balconies

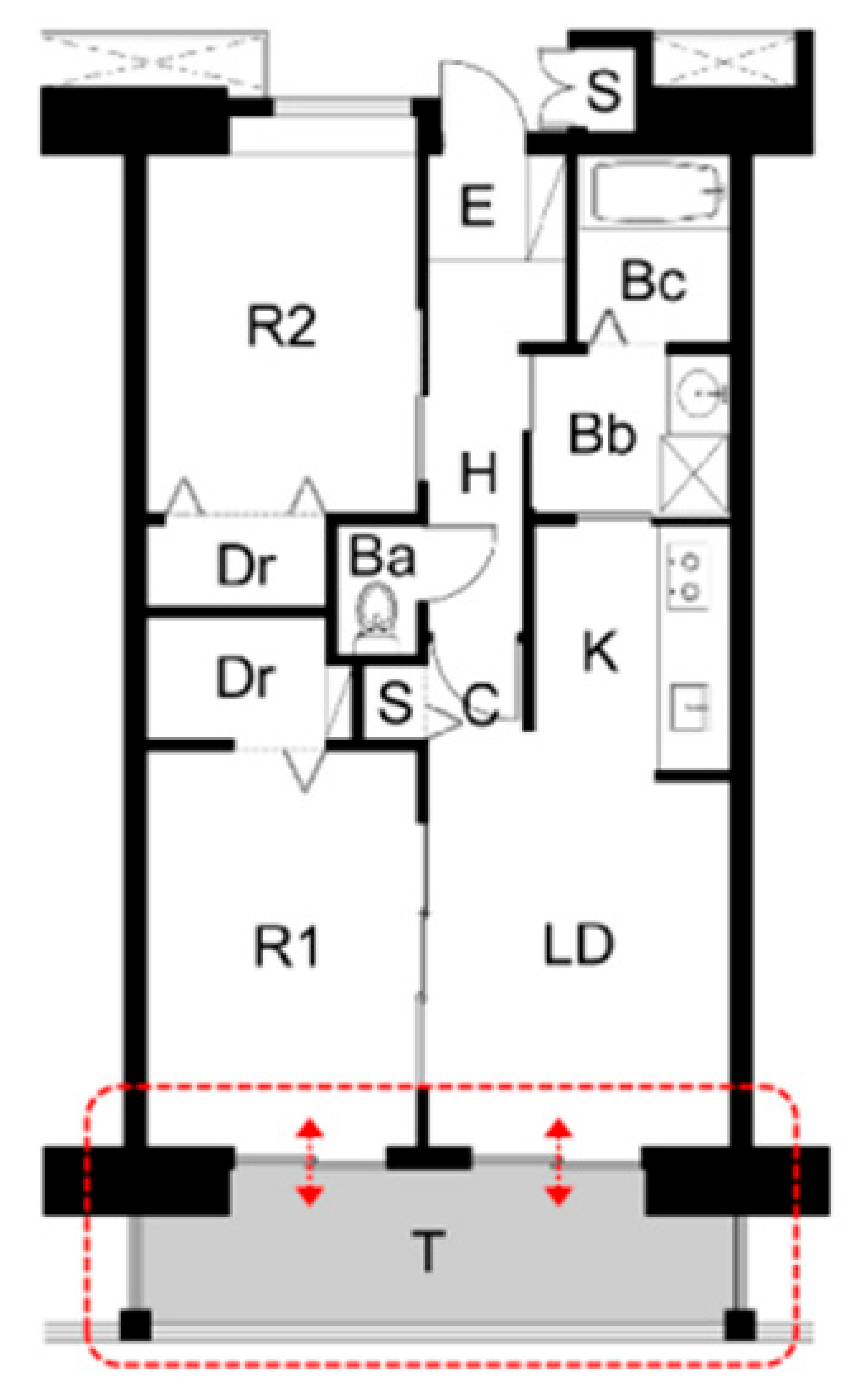

As presented in

Table 6, in the residential unit plan designs of China, Japan, and South Korea, the configuration, types, and adjacent relationships of balconies also show significant differences. In Japan and South Korea, balcony elements are commonly included in residential unit plan designs. In Japan, single balconies are the mainstream, and double or triple balconies are occasionally seen. Additionally, as a public space for emergency evacuation in the horizontal direction, the design of balconies emphasizes communication and connection among households. Therefore, in the unit plans of residential with double or triple balconies, usually only a part of the balconies exists in a prominent form and is combined with recessed balconies to form a mixed balcony layout. In South Korea, unit plan designs mainly feature single balconies, and double balcony designs are also relatively common, while triple balcony designs are extremely rare. Given that balconies are a given area that can significantly increase the effective usable area of the residential interior space, in the practice of residential unit designs in South Korea, balconies have become a key factor influencing all types of unit plans. In balcony design, recessed design predominates, aiming to maximize the efficiency of indoor space utilization. Prominent and mixed balcony designs are relatively less common. In contrast, in Chinese unit plan designs, only 80% of the units have balconies, and they are all single balcony designs. Chinese balcony designs include recessed and prominent types. Unlike Japan and South Korea, prominent balcony designs in China are more common. In terms of the connection relationship of balconies, balcony designs in Japan are usually connected to multiple spaces, presenting a mixed characteristic, and only in unit plans without a bedroom or with a single bedroom, the balcony may also be connected to a living room or bedroom space. In South Korea, balconies are mostly adjacent to bedrooms, but some also connect to the living room, forming a mixed balcony. In unit plans with double or triple balconies, except for one balcony connected to the bedroom, the rest are mostly connected to the living room or kitchen, also belonging to a mixed type. In China, more than half of the balconies are connected to the living room, and the rest are connected to bedrooms or kitchens and other spaces. These differences are closely related to the differences in residents’ cognitive functions of balcony spaces in different countries. For example, in China, balconies are mainly given a usage function, serving as an expansion area for living functions, and their main uses include drying clothes and leisure, and entertainment. In Japan, balcony design places more emphasis on the combination of safety and multi-functionality, and balconies not only serve as escape spaces but also have functions such as gardens and leisure. In South Korea, the functional positioning of balconies is between China and Japan. Depending on actual needs, balconies can be an independent expansion area for living, and in some designs, vertical evacuation functions are also considered.

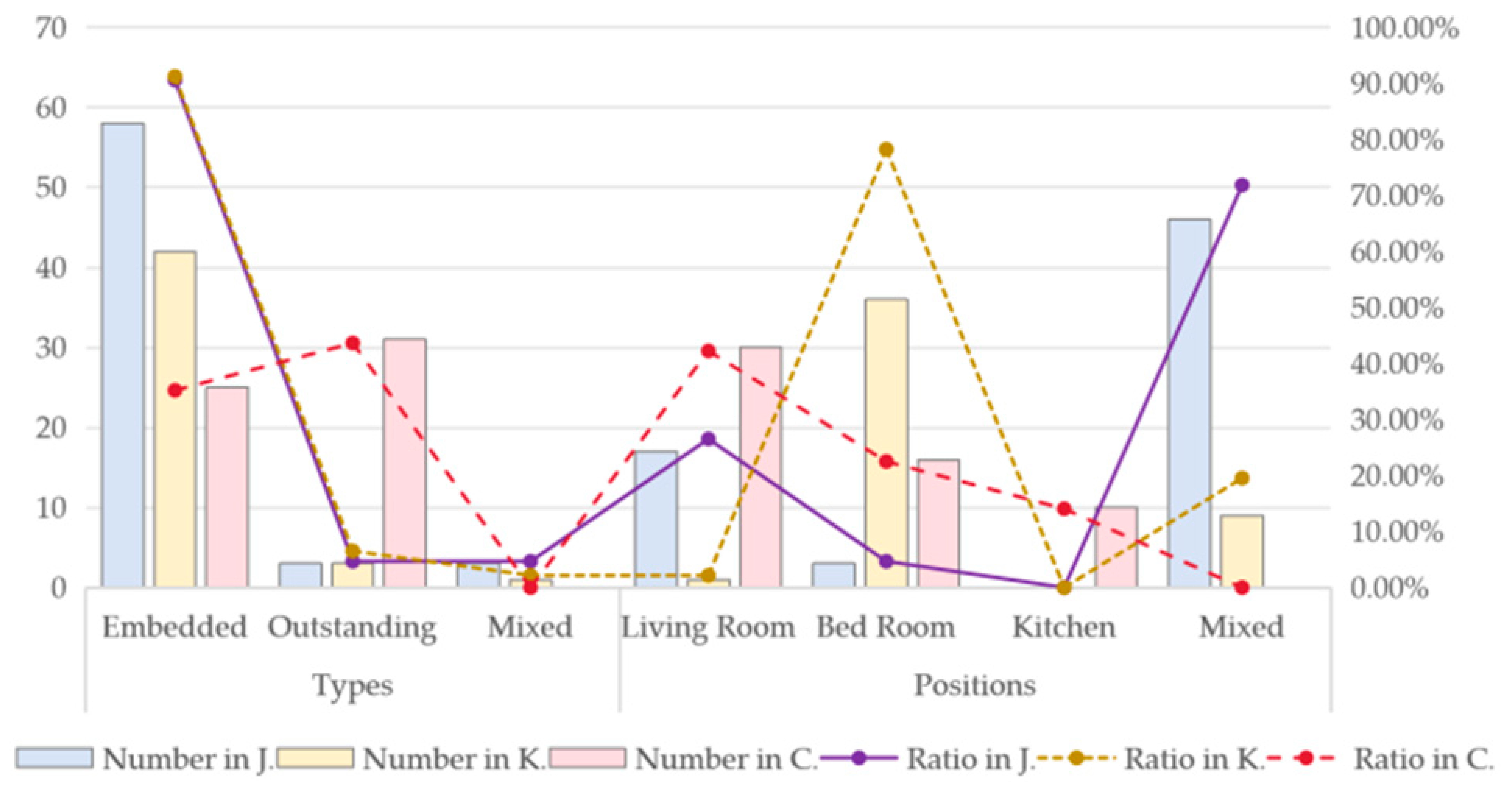

4.6. Spatial Composition of Bathrooms

In

Table 7, compared with the bathroom designs in China and South Korea, those in Japan show significant differences. Specifically, they separate the functions of bathing, toilet, and washing up into three independent spaces. Although in some residential unit plans in China, the washing-up area is placed in an external transfer space, most bathroom designs still prefer to concentrate the functions of bathing, toilet, and washing up in a single space. The advantage of such designs lies in being able to integrate multiple functions within a limited area. In Japan, the popularity of the three-separation bathroom design reflects its unique bathing culture. Specifically, the Japanese consider bathing as a sacred act of cleanliness, while defecation as an unclean matter. Therefore, they tend to separate these two behaviors in different spaces. However, from the perspective of space utilization, compared to the independent bathroom designs in two-bedroom layouts in South Korea and China, the three-separation bathroom design in Japan does not seem to have an advantage in terms of area, but its advantage lies in being able to allow simultaneous use of different functional spaces. Additionally, compared to the two independent bathroom designs in three-bedroom layouts in South Korea, the three-separation bathroom design in Japan has obvious advantages. That is, it does not increase the number of bathrooms with an increase in the number of bedrooms, and the three-separation bathroom design can fully meet the needs of a multi-person household. Besides the differences in the spatial composition of bathrooms, the bathing culture of Japan and South Korea leads to the consideration of at least one bathtub configuration in bathroom designs. Conversely, Chinese people prefer showers, so bathrooms in Chinese designs usually do not have bathtubs and only consider showers.

4.7. Other Spatial Configuration Characteristics

Apart from the aforementioned spatial composition characteristics, the spatial composition elements also exhibit certain differences. Taking Japan and South Korea as examples, their designs tend to meet the needs of a sitting lifestyle. The habit of residents taking off their shoes upon entering the house prompts designers to achieve a clear separation of indoor and outdoor activities through the design of sunken entrance halls or entry passages. In contrast, Chinese residents prefer a standing lifestyle and emphasize the continuity of indoor and outdoor activities. Therefore, in the unit plan designs, independent foyer spaces are often not set, especially lacking foyer spaces with height differences. Additionally, in Japanese floor plan designs, the door panels commonly set between the living room and the entrance corridor highlight the Japanese residents’ high regard for privacy protection. At the same time, the configuration of various functional storage spaces, wardrobes and storage areas not only ensures the safety of personal items but also significantly improves the tidiness and comfort of the indoor environment. To meet the needs of different residents, some floor plan designs in Japan have also introduced a room (with multiple functions) to achieve the diversification of living functions.

5. Insights for China’s Indemnificatory Housing

Under the continuous emphasis in China on “accelerating the establishment of a housing system that combines renting and purchasing, and enhancing the construction and supply of indemnificatory housing”, as well as the clear policy orientation in the “14th Five-Year Plan” to focus on the development of indemnificatory rental housing and further optimize the housing security system by expanding the supply of indemnificatory housing, various regions across the country have significantly increased the construction efforts of indemnificatory housing and actively promulgated a series of policies and regulations regarding the construction and supply of indemnificatory housing [

4,

5,

6]. However, during the actual implementation process, there are still problems such as tight land resources, insufficient capital investment, single models in the housing supply sector, limited coverage, imperfect allocation mechanisms, poor operation management, and insufficient collaboration between the state and society [

6]. Especially within the strategic context where the nation promotes the development of indemnificatory housing into safe, comfortable, green, and intelligent “Better Housing”, how to optimize the supply system of indemnificatory housing and construct units that meet the “Better Housing” standards has become an urgent issue requiring prompt resolution. Therefore, the decades-long public housing development experience of South Korea and Japan, as well as the characteristics of public rental housing layout and space composition formed under the policy orientation of high-quality housing in both countries, have certain practical reference value for the development of indemnificatory housing in China.

5.1. Construction of Policy System

The success of public housing policies in Japan and South Korea is largely attributed to their well-developed and continuously evolving policy systems. The evolution from the “Public Housing Act” to the “Basic Law on Housing Life” in Japan, and the development from the “Daehan Housing Corporation Act” to the “Housing Welfare Roadmap” in South Korea, demonstrate the continuity of policies, legal guarantees, and the strategic shift from “quantity guarantee” to “quality improvement”. Although China has proposed the concepts of “equal emphasis on renting and purchasing” and “Better Housing”, the current relevant laws and regulations still have room for improvement in terms of systematization and detail. Therefore, China urgently needs to further improve the relevant laws and regulations for indemnificatory housing, clarify the roles and responsibilities of the government, the market, and social organizations at different stages, and ensure the stability and predictability of the policies. At the same time, the transformation path from “ensuring basic housing” to “providing high-quality living environments” should be clearly defined, and the standards for “Better Housing” should be institutionalized and quantified, and incorporated into the policy evaluation system.

In addition, specialized housing supply and management entities such as UR Agencies in Japan and the LH Corporation in South Korea have played a crucial role in providing high-quality public housing. Through standardized management, diversified housing supply institutions and models have been established. China, while maintaining government leadership, should actively introduce market mechanisms to stimulate and regulate the participation of social forces in the construction, operation, and management of indemnificatory housing. At the same time, diverse forms of indemnificatory housing should be explored to expand the supply range and meet the housing needs of different groups [

41,

42]. Moreover, in the current era of housing stock, the UR rental housing model in Japan mainly achieves this through the renovation of old residential areas. As some cities in China gradually enter the era of housing stock, it is necessary to draw on the experience of the UR model in Japan, closely integrating the construction of indemnificatory housing with urban renewal and the renovation of old residential areas. By revitalizing existing resources and enhancing functions, the supply of indemnificatory housing can be effectively increased, reducing excessive reliance on new housing construction, and achieving the goals of land resource intensive utilization and organic urban renewal.

5.2. Spatial Composition of Unit Plans

In the unit plan design of public housing in Japan and South Korea, the residents’ living needs, living habits, and potential future changes were fully considered. Their refined and humanized design concepts have significant reference value for the “Better Housing” guarantee housing projects implemented in China. For instance, the public housing in South Korea demonstrated its ability to meet the needs of multi-person households with three-bedroom layouts, and showed remarkable flexibility in terms of area and space utilization. In Japan, the unit plan design of the housing took into account the actual needs of residents, their daily behavior patterns, and possible future changes in family structure. Based on this, the design of China’s indemnificatory housing should break away from the simple limitations of “average area” and “at most two bedrooms”, and conduct refined design based on family structure (such as two-child, three-child families, grandparents living together, etc.), and introduce the concepts of “flexible space” and “variable design” for guidance. For example, using non-load-bearing partitions, sliding doors, multi-functional combined spaces (such as rooms with both study and children’s room functions), and considering the possibility of future renovations, the housing type can adapt to changes in family size, generational structure, and lifestyle, and extend the “service life” and “applicable period” of the housing [

43,

44,

45,

46]. At the same time, the design of China’s indemnificatory housing should draw on the experience of Japan and South Korea, through ingenious space division (such as LDK integration, flexible partitions), scale optimization, integrated storage systems, etc.; to achieve functional integration and efficient space utilization within a limited area, thereby enhancing the “actual usage experience” of the space.

In addition, the “three-separation” bathroom design in Japan, independent entrance area zoning, and modern interpretation of tatami elements, as well as the L.D.K. integration, multi-functional rooms, expandable balcony space, and sunken entrance areas in South Korea, all reflect respect for life details and living culture. Therefore, in the design of China’s indemnificatory housing, more attention should be paid to the humanization of details. For example, promoting dry-wet separation, even three-separation bathroom designs, to improve efficiency and hygiene standards; optimizing the entrance design to have transitional, shoe-changing, and storage functions; drawing on the experience of Japan and South Korea, optimizing the kitchen layout, balcony functions (for drying, relaxation, and household chores), and storage systems (embedded, multi-functional) in these aspects. At the same time, it should strictly follow the “Better Housing” construction standards and implement the principles of “safety durability”, “age-friendly and barrier-free design”, and “intelligent security system”.

5.3. Cultural Adaptability

The living space, as a component of the physical environment, not only serves the function of cultural transmission but also plays a crucial role in shaping the cultural identity of residents. Therefore, when designing the living space, it is necessary to deeply integrate it with local living habits to create a sense of cultural belonging. While Japan and South Korea have drawn on the experience of Western living space design, they have also not forgotten the inheritance and innovation of local living culture. This is of great significance for the design of indemnificatory housing in China. For instance, in Japanese residential design, the transformation from the living room to the entrance space and the preservation of tatami elements were achieved; in South Korean residential design, the evolution from heated beds to underfloor heating culture and the integration of traditional elements such as the sunken entrance were realized. Both countries have successfully integrated traditional residential wisdom with modern lifestyles during their modernization process. Although China’s closed kitchens, continuous design of indoor and outdoor activities, and Feng Shui concepts also reflect the characteristics of its local culture, in the design of indemnificatory housing in China, it is necessary to further study the living habits, lifestyle, family concepts, and cultural psychological needs of Chinese residents (especially the target guarantee group). For example, considering the special nature of Chinese dietary culture, in kitchen design, a combination of open, semi-open, and closed kitchens should be explored while ensuring effective smoke exhaust; considering the needs of family gatherings and entertaining guests, the layout and scale of the living room space should be fully considered; and given the high demand of residents for storage space, a sufficient and convenient storage system should be designed to enhance the comfort of the living environment.

Furthermore, considering the open and semi-open community planning models adopted by Japan and South Korea, as well as the diverse and personalized practice of UR rental housing in Japan in terms of floor plan design, it is recommended that China, in the process of promoting the efficiency and meeting basic standards of indemnificatory housing construction, should avoid the homogenization caused by excessive standardization [

47,

48,

49]. For example, at the stage of community planning design, reference can be made to the advanced experiences of Japan and South Korea, moderately enhancing openness and transparency to enhance interaction and integration between the community and the outside world, and prevent the formation of isolated and closed community patterns. In terms of floor plan design, it is recommended to provide several selectable options with different styles or functional emphases to meet the individual needs of residents.

Moreover, in the process of building indemnificatory housing, attention should also be paid to the individual differences of the residents and the issue of social integration to promote the construction of inclusive communities. For instance, when Japan and South Korea addressed the challenge of population aging, their housing designs incorporated elements of age-friendly design, which are worthy of reference. In response to the current trend of population aging in China, the construction of indemnificatory housing should fully consider age-friendly design and the popularization of accessibility facilities to create a community environment friendly to all age groups. In addition, in community planning and management, efforts should be made to promote communication and mutual assistance among residents of different age groups and professional backgrounds, creating an inclusive and harmonious community atmosphere. To prevent the phenomenon of social isolation caused by excessive concentration of indemnificatory housing, it is recommended to draw on the experience of Japan and South Korea and build indemnificatory housing in a certain proportion in ordinary commercial housing projects.

6. Discussion

This study adopts a comparative research framework encompassing China, Japan, and South Korea, with the objective of examining the implications of public housing practices in China and South Korea for the development of China’s indemnificatory housing. It offers theoretical foundations and practical guidance for enhancing the supply system and spatial design of China’s indemnificatory housing. Grounded in theoretical perspectives such as housing policies and residential culture, and employing architectural typology analysis methods, this study conducts an in-depth analysis of the spatial composition characteristics of typical rental housing units in three countries, aiming to explore the influence of different policy systems and residential cultures on the spatial composition features of residential units. Finally, through a parallel comparative analysis of the policy backgrounds, residential histories, and spatial structures of the three countries, this study proposes a “policy–space–culture” tripartite integrated framework to guide the development of China’s indemnificatory housing.

Compared with the current research that mainly focuses on the foundational study of the policy system for indemnificatory housing, this study places more emphasis on adopting an architectural perspective, integrating policy theories with historical and cultural research, and striving to conduct interdisciplinary and cross-border comprehensive research on theories and cases. The research focuses are to conduct comparative analysis of the spatial structure characteristics of public rental housing unit plans in different countries, providing practical suggestions for the spatial design of unit plans in China’s indemnificatory housing; at the same time, from the perspective of policy orientation, it proposes optimization suggestions for the housing supply system for China’s indemnificatory housing development; ultimately, based on the influencing factors of the spatial composition, from the perspective of cultural adaptability, it proposes spatial optimization strategies that are in line with Chinese living culture and habits. Through the above research, this study aims to provide theoretical support for the formulation of the “safe, comfortable, green, and intelligent” standards for China’s indemnificatory housing.

The research reveals that the development of public housing in Japan, South Korea, and China follows a certain sequence. Specifically, Japan initiated its development in the public housing sector earlier, followed by South Korea, and China began its development relatively later. During the development of public housing in South Korea, it was influenced by the policies during the period of Japanese colonial rule, and it absorbed a significant amount of relevant Japanese experience. Moreover, given that both Japan and South Korea are economically developed countries, the continuous improvement of residents’ living standards and the increasingly severe problem of population aging in both countries have driven the transformation of public housing towards high-quality and age-friendly living spaces. This transformation has provided important references for the development of indemnificatory housing in China. In particular, the construction of high-quality living spaces has significant practical guidance value for the “Better Housing” construction of indemnificatory housing in China. At the same time, the development strategy of making public housing age-friendly will become the core topic of future research, in order to meet the challenges of future Chinese society’s demand for age-friendly housing.

7. Conclusions

In the current context where China is continuously emphasizing the construction and supply of indemnificatory housing, and actively promoting the construction of “Better Housing” for such housing, the development experiences of Japan and South Korea in the field of public housing reveal that a successful system of indemnificatory housing is the result of the interaction and coordinated development of the policy framework, spatial design planning, and cultural factors. In the process of promoting the construction of indemnificatory housing, China should deeply absorb the advanced experiences of Japan and South Korea in areas such as the legal policy framework, diversified supply management, detailed spatial planning, flexible adaptation to future demands, and respect for local culture. At the same time, in light of China’s national conditions, efforts should be made to make the construction of indemnificatory housing meet the people’s pursuit of a high-quality living environment, thereby achieving the policy goal of making indemnificatory housing “Better Housing”, and creating a livable space with a warm atmosphere, high-quality standards, and cultural identity.