Smart Retirement Villages as Sustainable Housing Solutions: A TAM-Based Study of Elderly Intention to Relocate

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Socio-Demographic Factors of the Elderly

2.2. Age-Related Demographic Factor

2.3. Gender-Related Demographic Factor

2.4. Ethnicity-Related Demographic Factor

2.5. Marital Status-Related Demographic Factor

2.6. Education-Related Demographic Factor

2.7. Occupation-Related Demographic Factor

2.8. Living Conditions Related to Demographic Factor

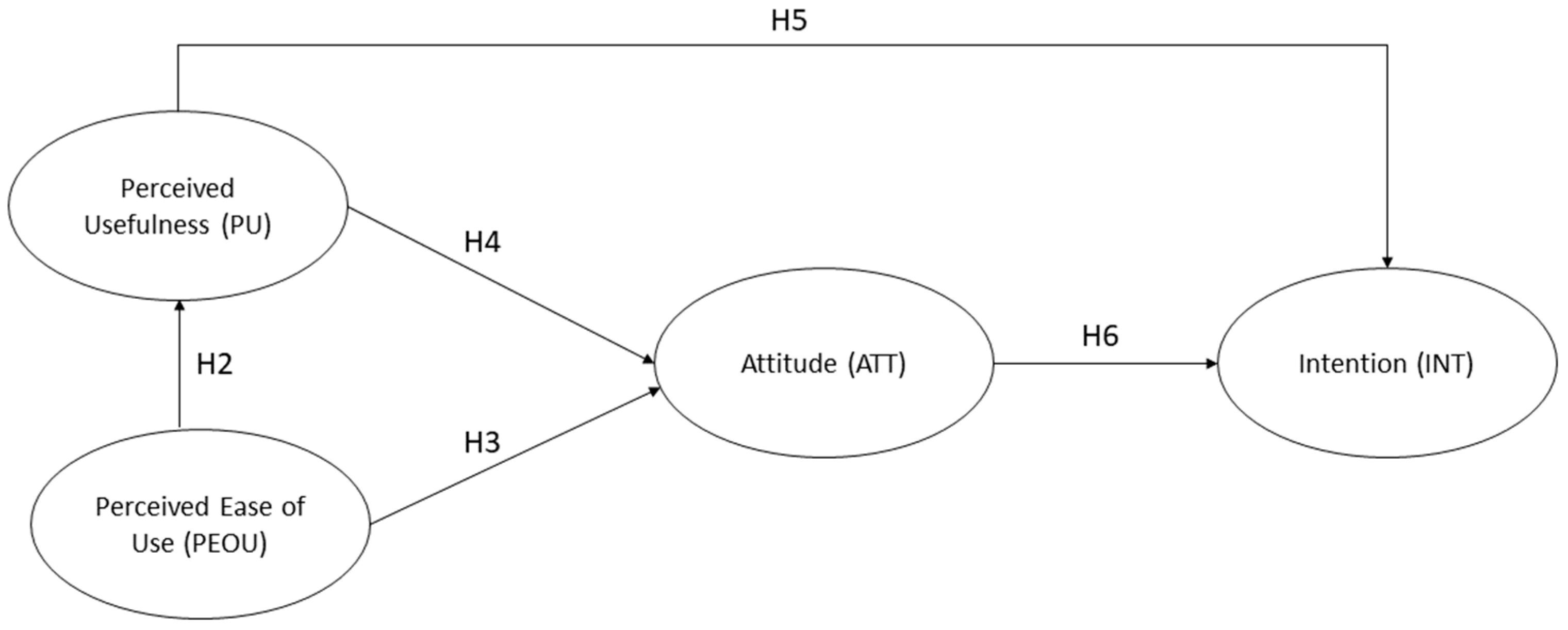

2.9. Technology Acceptance Model (TAM)

3. Methods

4. Results

4.1. Gender and Independent Sample T-Test

4.2. Other Socio-Demographic Characteristics and Analysis of Variance (ANOVA)

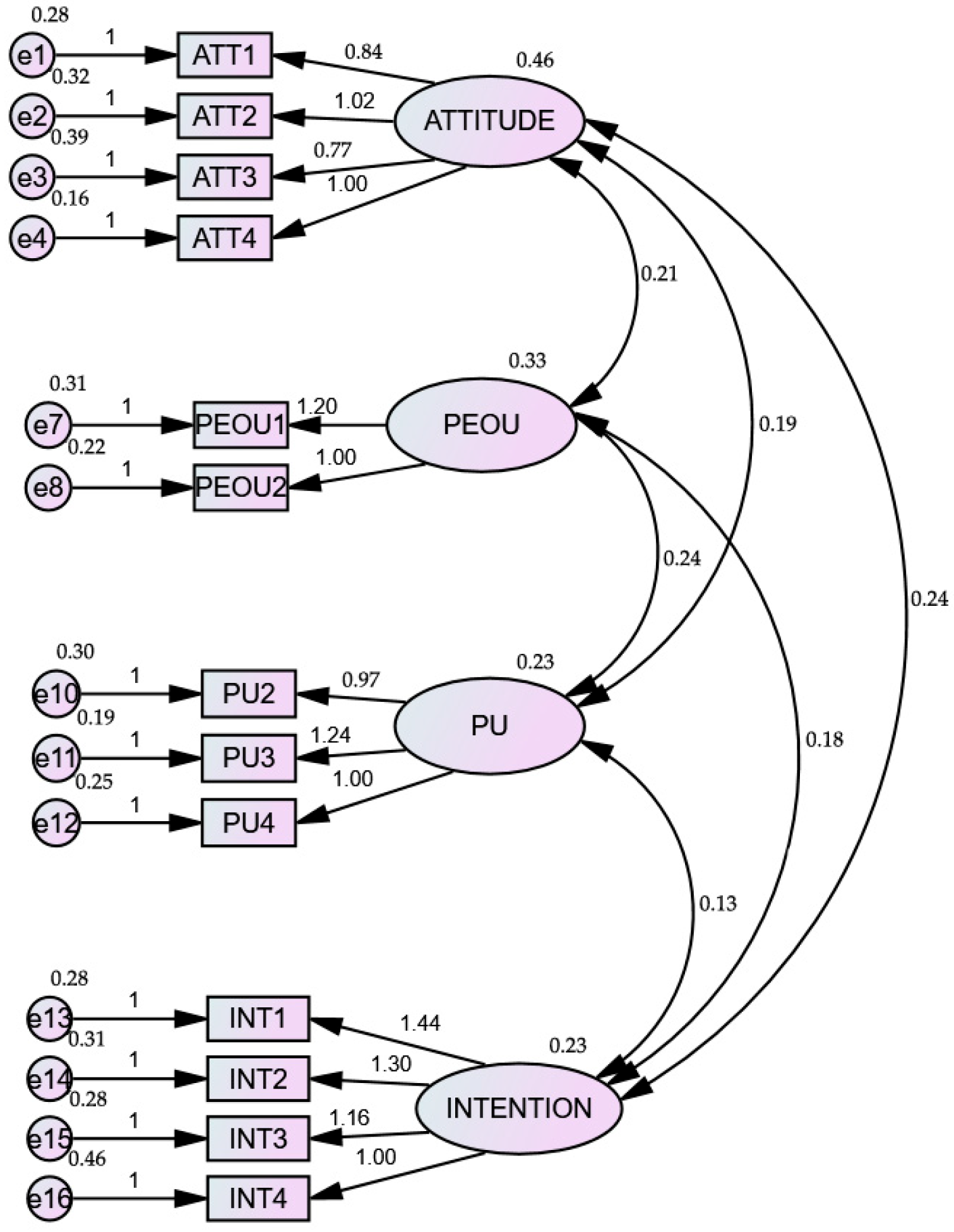

4.3. Assessment of Measurement Model

4.4. Convergent Validity

4.5. Discriminant Validity

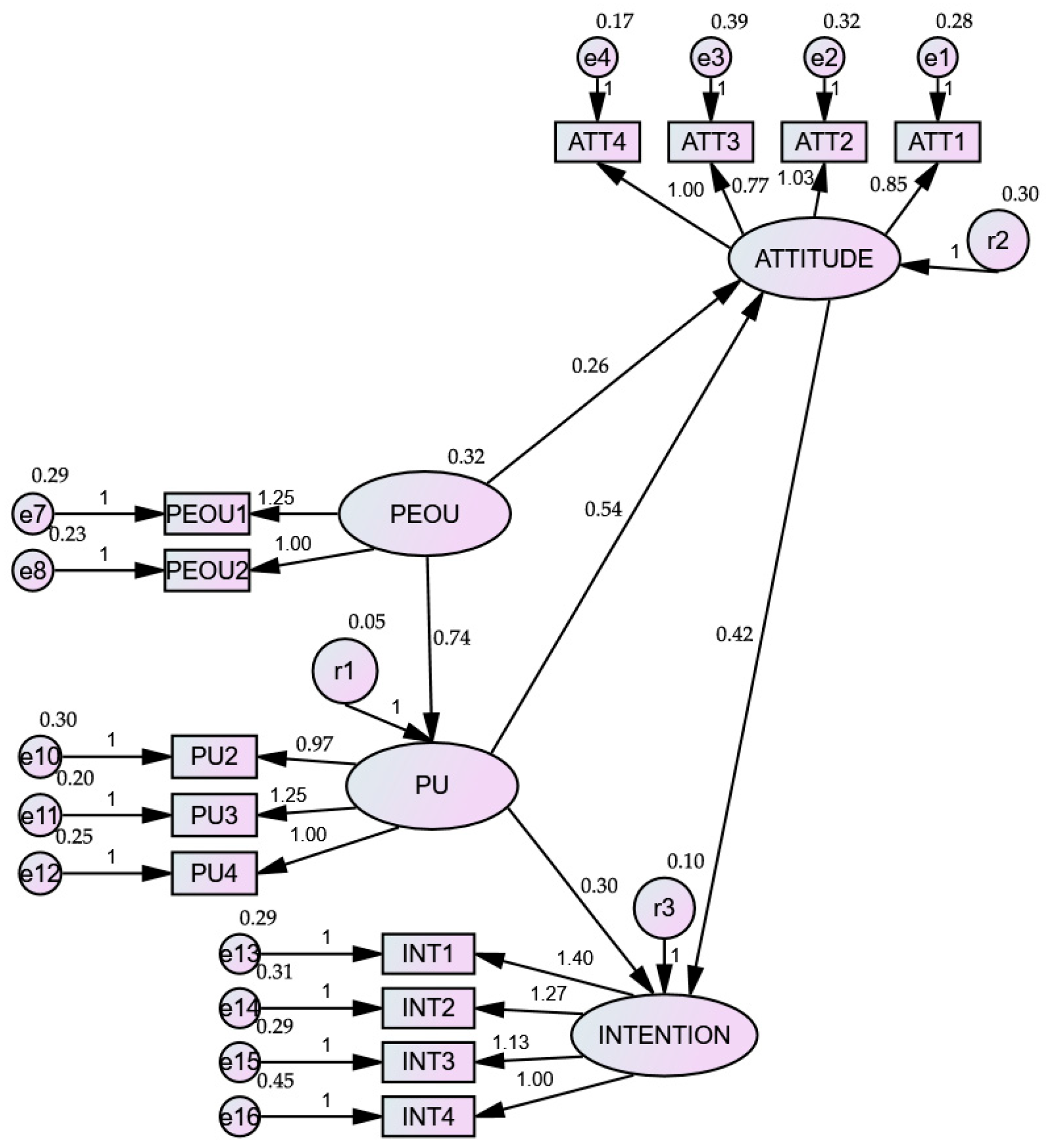

4.6. Assessment of Structural Model

4.7. Results of Hypothesis Testing (H2–H6)

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akhtar, R. The Elderly as Agents of Change. 2023. Available online: https://www.thesundaily.my/opinion/the-elderly-as-agents-of-change-EI10810444 (accessed on 10 September 2023).

- Tan, B.C.; Pang, S.M.; Lau, T.C.; Lo, Y.T.; Tan, A.H.P. Enhancing Elderly Well-Being Through the Adoption of Medication Adherence System. In Advances in Intelligent Manufacturing and Robotics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Villar, F.R.; Castillo-Villar, R.G. Mobile banking affordances and constraints by the elderly. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2023, 41, 124–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Li, H.; Yang, S.X.L. Willingness to pay and its influencing factors for aging-appropriate retrofitting of rural dwellings: A case study of 20 villages in Wuhu, Anhui Province. Buildings 2024, 14, 3163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.C.; Lau, T.C.; Khan, N.; Tan, W.H.; Ooi, C.P. Elderly Customers’ Open Innovation on Smart Retirement Village: What They Want and What Drive Their Intention to Relocate? J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, D.; Papasratorn, B.; Chutimaskul, W.; Funilkul, S. Embracing the Smart-Home Revolution in Asia by the Elderly: An End-User Negative Perception Modeling. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 38535–38549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, N.A.A.C.A.; Yusuf, M.M. Socioeconomic Factors Affecting Healthcare Expenditures in Selected Asian Countries. Int. J. Manag. Financ. Account. 2024, 5, 203–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzeng, H.-M.; Okpalauwaekwe, U.; Li, C.-Y. Older Adults’ Socio-Demographic Determinants of Health Related to Promoting Health and Getting Preventive Health Care in Southern United States: A Secondary Analysis of a Survey Project Dataset. Nurs. Rep. 2021, 11, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meneguci, J.; Sasaki, J.E.; da Silva Santos, Á.; Scatena, L.M.; Damião, R. Socio-demographic, clinical and health behavior correlates of sitting time in older adults. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, R.; Brenner, G. Relocation of the Aged: A Review and Theoretical Analysis. J. Gerontol. 1977, 32, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, M.P.; Nahemow, L. Ecology and the aging process. In The Psychology of Adult Development and Aging; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1973; pp. 619–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kylén, M.; Slaug, B.; Iwarsson, S.; Dahlgren, D.; Bjork, J.; Zingmark, M. Housing attribute preferences when considering relocation in older age. Innov. Aging 2023, 7, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaulagain, S. Unveiling the Relocation Journey: A Qualitative Study of Key Factors Influencing Older Adults’ Decisions to Relocate to Senior Living Communities. J. Ageing Longev. 2025, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, F.; Sciotto, G. Gender Differences in the Relationship between Work–Life Balance, Career Opportunities and General Health Perception. Sustainability 2021, 14, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobieraj, S.; Krämer, N.C. Similarities and differences between genders in the usage of computer with different levels of technological complexity. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 104, 106145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, C.; Ye, B.; Mihailidis, A.; Cameron, J.I.; Astell, A.; Nalder, E.; Colantonio, A. Sex and gender differences in technology needs and preferences among informal caregivers of persons with dementia. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legge, V. The Retirement Accommodation Needs of Immigrants from Non-English Speaking Countries. Ph.D. Thesis, UNSW Sydney, Kensington, Australia, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, S.I.; Zhao, F.; Lim, X.-J.; Basha, N.K.; Sambasivan, M. Retirement village buying intention. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2020, 32, 1451–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, J. Community Participation in an Australian Retirement Village. Aust. J. Ageing 1996, 15, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkinson, M.A.; Rockemann, D.D. Older Women Living in a Continuing Care Retirement Community: Marital Status and Friendship Formation. J. Women Aging 1996, 8, 159–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. Older Adults and Technology Use; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, K.T. Older adults’ behavioral attitude and intention to move into retirement villages in Malaysia. J. Mark. Manag. Consum. Behav. 2019, 2, 55–75. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, I.L. Why People Move to Retirement Villages: Home owners and non-home owners. Aust. J. Ageing 1994, 13, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broad, J.B.; Wu, Z.; Bloomfield, K.; Hikaka, J.; Bramley, D.; Boyd, M.; Tatton, A.; Calvert, C.; Peri, K.; Higgins, A.-M.; et al. Health profile of residents of retirement villages in Auckland, New Zealand: Findings from a cross-sectional survey with health assessment. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e035876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harel, D.; Ayalon, L. A Bibliotherapeutic discourse on aging and masculinity in continuing care retirement communities. J. Aging Stud. 2022, 63, 101033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, M.; Calvert, C.; Tatton, A.; Wu, Z.; Bloomfield, K.; Broad, J.B.; Hikaka, J.; Higgins, A.-M.; Connolly, M.J. Lonely in a crowd: Loneliness in New Zealand retirement village residents. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2021, 33, 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willis, P.; Vickery, A.; Jessiman, T. Loneliness, social dislocation and invisibility experienced by older men who are single or living alone: Accounting for differences across sexual identity and social context. Ageing Soc. 2022, 42, 409–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julaihi, F.A.; Bohari, A.A.M.; Azman, M.A.; Kipli, K.; Amirul, S.R. The Preliminary Results on the Push Factors for the Elderly to Move to Retirement Villages in Malaysia. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2022, 30, 761–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. A Technology Acceptance Model for Empirically Testing New End-User Information Systems: Theory and Results. Ph.D. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, W.M.; Lee, J.W.C. 5G Connected Autonomous Vehicle Acceptance: The Mediating Effect of Trust in the Technology Acceptance Model. Asian J. Bus. Res. 2021, 11, 40–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: System characteristics, user perceptions and behavioral impacts. Int. J. Man-Mach. Stud. 1993, 38, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdhany, F.R.; Aldianto, L. Adoption and acceptance of smart home technology products for millennials in Indonesia. Asian J. Res. Bus. Manag. 2020, 2, 154–164. [Google Scholar]

- Hubert, M.; Blut, M.; Brock, C.; Zhang, R.W.; Koch, V.; Riedl, R. The influence of acceptance and adoption drivers on smart home usage. Eur. J. Mark. 2019, 53, 1073–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Kim, S.; Kim, Y.; Kwon, S.J. Smart home services as the next mainstream of the ICT industry: Determinants of the adoption of smart home services. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2018, 17, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, T.-H.; Lin, W.-Y.; Chang, Y.-S.; Chang, P.-C.; Lee, M.-Y. Technology anxiety and resistance to change behavioral study of a wearable cardiac warming system using an extended TAM for older adults. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0227270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosales, A.; Fernández-Ardèvol, M. Smartphones, apps and older people’s interests. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services, Florence, Italy, 6–9 September 2016; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. The influence of attitudes on behavior. In The Handbook of Attitudes; Albarracin, D., Johnson, B.T., Zanna, M.P., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 173–221. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F.D.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Warshaw, P.R. User Acceptance of Computer Technology: A Comparison of Two Theoretical Models. Manag. Sci. 1989, 35, 982–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, H.; Janda, S. Predicting consumer intentions to purchase energy-efficient products. J. Consum. Mark. 2012, 29, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, D.; Schindler, P. Business Research Methods; McGraw-Hill/Irwin: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Lockwood, C.M.; Hoffman, J.M.; West, S.G.; Sheets, V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, J. Why “Seniors” Are Not a Single Market. LinkedIn. 2018. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/why-seniors-single-market-jon-warner/ (accessed on 14 September 2023).

- Verderber, S.; Koyabashi, U.; Cruz, C.D.; Sadat, A.; Anderson, D.C. Residential Environments for Older Persons: A Comprehensive Literature Review (2005–2022). HERD Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2023, 16, 291–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Author | INT | PEOU | PU | ATT | Sample | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Ferdhany and Aldianto (2020) [32] | Intention to use smart home products | PEOU → PU * | PU → INT * | ATT → INT * | General (all ages) | Indonesia |

| 2. | Hubert et al. (2019) [33] | Intention to use smart home applications | PEOU → PU * | PU → INT * | N/A | General (all ages) | United Kingdom |

| 3. | Park et al. (2018) [34] | Intention to use smart home services | PEOU → PU * PEOU → ATT ** | PU → INT * | ATT → INT * | General (all ages) | Korea |

| 4. | Pal et al. (2017) [6] | Intention to adopt smart home services | PEOU → PU * PEOU → ATT * | PU → ATT * | ATT → INT * | Elderly | Thailand |

| 5. | Tsai (2020) [35] | Intention to use smart clothing (general and with cardiovascular disease, CD) | PEOU → PU * PEOU → ATT * (general) PEOU → PU ** (with CD) PEOU → ATT ** (with CD) | PU → ATT * (general and with CD) PU → INT ** (general and with CD) | ATT → INT * (general) | Elderly | Taiwan |

| Construct | Socio-Demographic | Frequency (N) | Percentage (%) | Average Mean | p-Value | Finding | Hypothesis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intention to relocate to a smart retirement village | Gender | Female | 128 | 42.0 | 3.96 | 0.440 | Not significant | H1b not supported |

| Male | 177 | 58.0 | 4.01 | |||||

| Age | 55 to 60 | 137 | 44.9 | 3.88 | 0.045 * | Significant | H1a supported | |

| 61 to 65 | 80 | 26.2 | 4.08 | |||||

| 66 to 70 | 68 | 22.3 | 4.12 | |||||

| 71 & above | 20 | 6.6 | 3.93 | |||||

| Ethnicity | Malay | 123 | 40.3 | 3.95 | 0.001 ** | Significant | H1c supported | |

| Chinese | 121 | 39.7 | 4.07 | |||||

| Indian | 55 | 18 | 4.04 | |||||

| Others | 6 | 2 | 3.00 | |||||

| Marital status | Single | 92 | 30.2 | 3.89 | 0.040 * | Significant | H1d supported | |

| Married | 184 | 60.3 | 4.08 | |||||

| Others | 29 | 9.5 | 3.72 | |||||

| Education | Tertiary | 130 | 42.6 | 4.02 | 0.564 | Not significant | H1e not supported | |

| Secondary | 132 | 43.3 | 3.99 | |||||

| Primary | 38 | 12.5 | 3.93 | |||||

| Others | 5 | 1.6 | 3.65 | |||||

| Occupation | Retired | 111 | 36.4 | 3.95 | 0.326 | Not significant | H1f not supported | |

| Working Part-time | 137 | 44.9 | 3.98 | |||||

| Working full-time | 57 | 18.7 | 4.10 | |||||

| Living conditions | Living with children | 98 | 32.1 | 4.05 | 0.654 | Not significant | H1g not supported | |

| Living with spouse | 131 | 43.0 | 3.98 | |||||

| Living alone | 69 | 22.6 | 3.94 | |||||

| Other arrangements | 7 | 2.3 | 3.82 | |||||

| Goodness-of-Fit Indices | Desirable Range | Original Structural Model |

|---|---|---|

| CMIN/DF | <5 | 2.939 |

| CFI | >0.90 | 0.934 |

| GFI | >0.90 | 0.923 |

| NFI | >0.90 | 0.934 |

| TLI | >0.90 | 0.914 |

| RMSEA | <0.08 | 0.079 |

| Hypothesis | Path | Standardized Coefficient | p Value | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2 | PEOU → PU | 0.884 | *** | Supported |

| H3 | PEOU → ATT | 0.223 | 0.325 | Not supported |

| H4 | PU → ATT | 0.382 | 0.094 | Not supported |

| H5 | PU → INT | 0.287 | *** | Supported |

| H6 | ATT → INT | 0.573 | *** | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tan, B.C.; Lau, T.C.; D’Souza, C.; Khan, N.; Tan, W.H.; Ooi, C.P.; Pang, S.M. Smart Retirement Villages as Sustainable Housing Solutions: A TAM-Based Study of Elderly Intention to Relocate. Buildings 2025, 15, 2768. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15152768

Tan BC, Lau TC, D’Souza C, Khan N, Tan WH, Ooi CP, Pang SM. Smart Retirement Villages as Sustainable Housing Solutions: A TAM-Based Study of Elderly Intention to Relocate. Buildings. 2025; 15(15):2768. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15152768

Chicago/Turabian StyleTan, Booi Chen, Teck Chai Lau, Clare D’Souza, Nasreen Khan, Wooi Haw Tan, Chee Pun Ooi, and Suk Min Pang. 2025. "Smart Retirement Villages as Sustainable Housing Solutions: A TAM-Based Study of Elderly Intention to Relocate" Buildings 15, no. 15: 2768. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15152768

APA StyleTan, B. C., Lau, T. C., D’Souza, C., Khan, N., Tan, W. H., Ooi, C. P., & Pang, S. M. (2025). Smart Retirement Villages as Sustainable Housing Solutions: A TAM-Based Study of Elderly Intention to Relocate. Buildings, 15(15), 2768. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15152768