Exploring the Key Factors Influencing the Plays’ Continuous Intention of Ancient Architectural Cultural Heritage Serious Games: An SEM–ANN–NCA Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature

2.1. Stimuli–Organism–Response (S–O–R) Model

2.1.1. Characteristics of CH Serious Games (Stimulus)

2.1.2. User Experience (Organism)

2.1.3. Game Continuance Intention (Response)

2.2. Hypotheses Development and Conceptual Model Construction

2.2.1. Authenticity of Cultural Elements

2.2.2. Knowledge Acquisition

2.2.3. Perceived Playfulness

2.2.4. Design Aesthetics

2.2.5. Perceived Value

2.2.6. Cultural Identity

2.2.7. Perceived Enjoyment

2.2.8. Game Continuance Intention

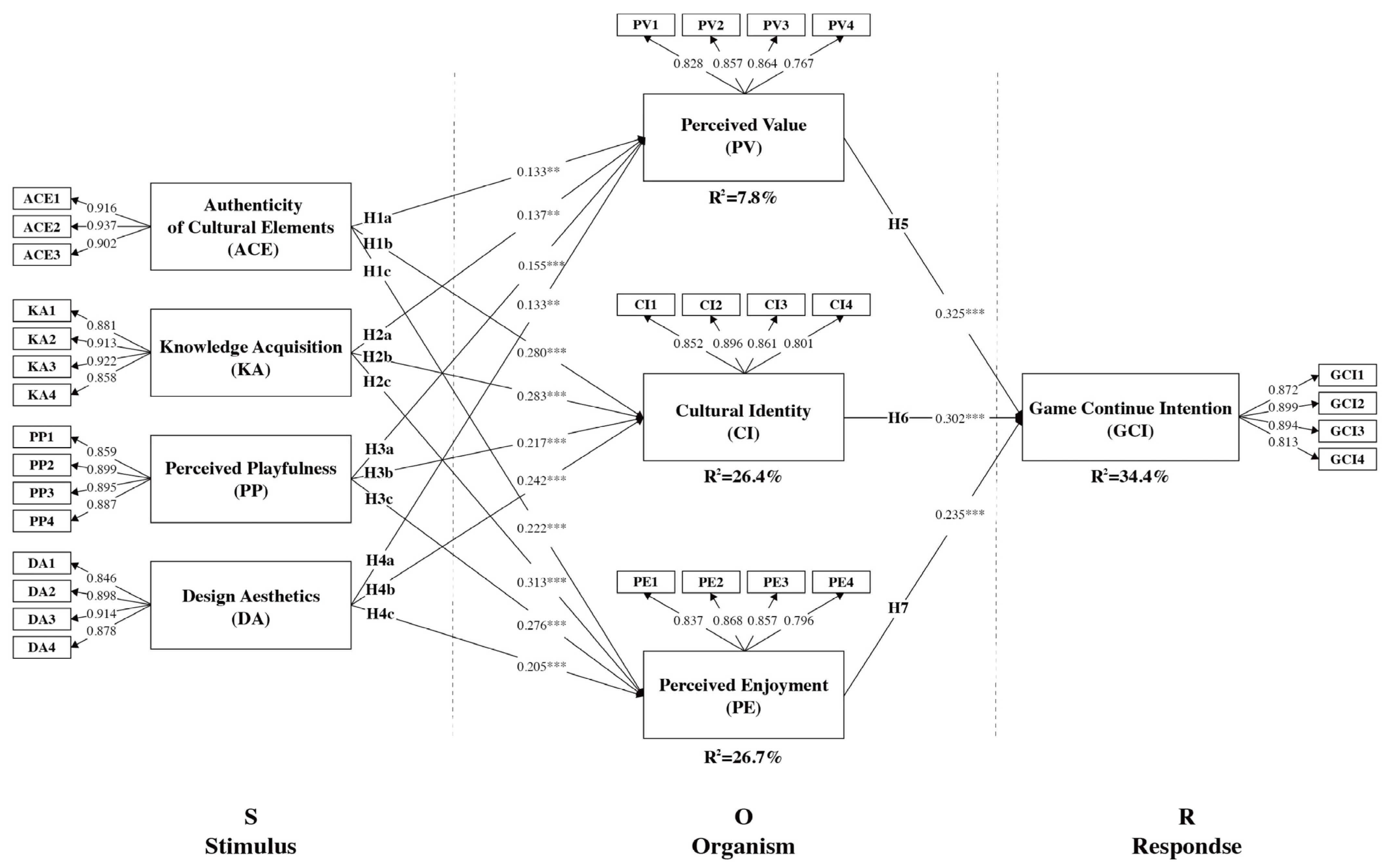

2.2.9. Conceptual Model

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Process

3.2. Data Collection

3.2.1. Pre-Research Analysis

3.2.2. Formal Data Collection

3.3. Respondent Profile

4. Results

4.1. PLS-SEM Results

4.1.1. Assessment of Measurement Model

4.1.2. Assessment of Structural Model

4.2. ANN Results

4.2.1. Model Building

4.2.2. Validation of ANN

4.2.3. Sensitivity Analysis

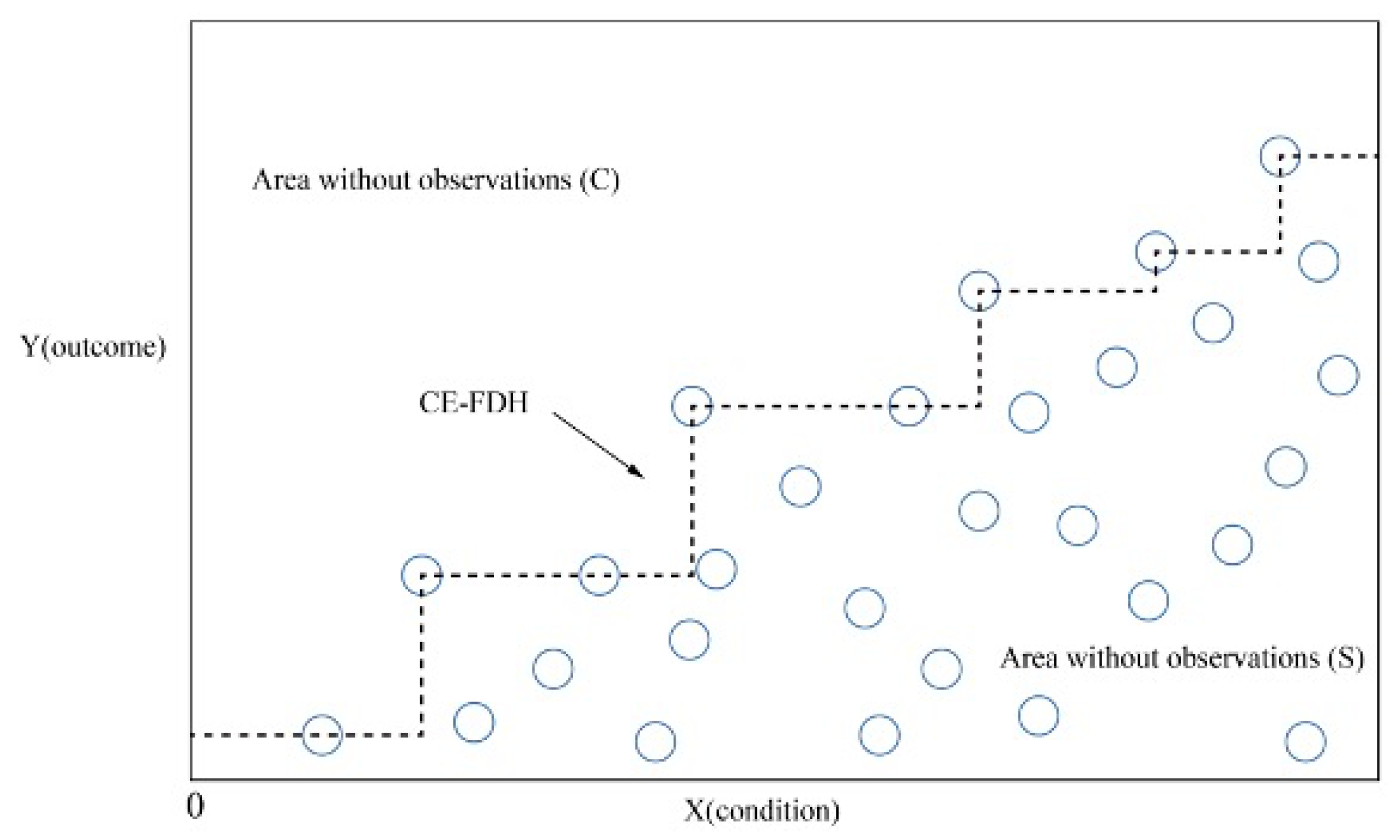

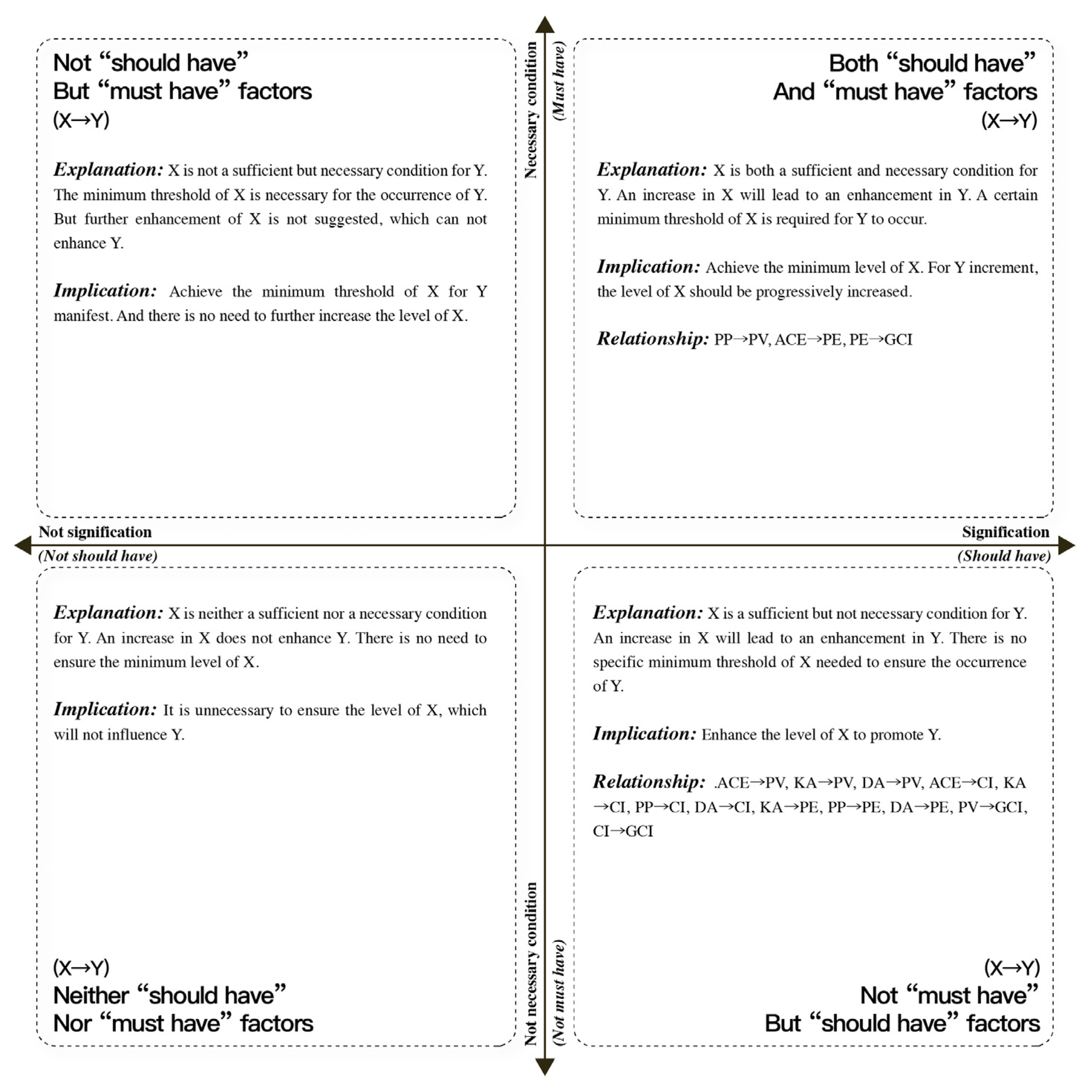

4.3. NCA Results

4.3.1. Effect Size and Significance Testing

4.3.2. Bottleneck Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Implications, Limitations and Conclusions

6.1. Implications

6.2. Limitation and Future Research

6.3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Vecco, M. A definition of cultural heritage: From the tangible to the intangible. J. Cult. Herit. 2010, 11, 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Y. The scope and definitions of heritage: From tangible to intangible. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2006, 12, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. UNESCO—Text of the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2003; Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/en/convention (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Yu, Y.; Raed, A.A.; Peng, Y.; Pottgiesser, U.; Verbree, E.; van Oosterom, P. How digital technologies have been applied for architectural heritage risk management: A systemic literature review from 2014 to 2024. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Du, Y.; Yang, M.; Liang, J.; Bai, H.; Li, R.; Law, A. A review of the tools and techniques used in the digital preservation of architectural heritage within disaster cycles. Herit. Sci. 2023, 11, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chen, S.; Nah, K. Exploring the mechanisms influencing users’ willingness to pay for green real estate projects in Asia based on technology acceptance modeling theory. Buildings 2024, 14, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Huang, Q.; Luo, J.; Xu, J.; Pan, Y. Enhancing User Participation in Cultural Heritage through Serious Games: Combining Perspectives from the Experience Economy and SOR Theory. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malegiannaki, I.A.; Daradoumis, T.; Retalis, S. Teaching cultural heritage through a narrative-based game. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. (JOCCH) 2020, 13, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, D.; Zhang, C.; Yao, J. Design of a virtual reality serious game for experiencing the colors of Dunhuang frescoes. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-C.K.; Lu, L.-W.; Lu, R.-S. Integrating immersive learning technologies and alternative reality games for sustainable education: Enhancing the effectiveness and participation on cultural heritage education of primary school students. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, H.; Pan, Y. What Influences Users’ Continuous Behavioral Intention in Cultural Heritage Virtual Tourism: Integrating Experience Economy Theory and Stimulus–Organism–Response (SOR) Model. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitong, W.; Bing, Z.; Yiming, Z.; Shiyi, D. A three-dimensional study on the international communication of Black Myth: Wukong. Int. Commun. Chin. Cult. 2025, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionisio, M.; Nisi, V. Leveraging Transmedia storytelling to engage tourists in the understanding of the destination’s local heritage. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2021, 80, 34813–34841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochocki, M. Heritage sites and video games: Questions of authenticity and immersion. Games Cult. 2021, 16, 951–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.Y. An analysis of the development of serious games in China. Talent. Wisdom 2019, 3, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, P.; Cho, D.M. Research on an evaluation rubric for promoting user’s continuous usage intention: A case study of serious games for Chinese cultural heritage. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1300686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.-F. A study on the application of serious games in material cultural heritage. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, Shenyang Aerospace University, Shenyang, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M. Fostering cultural heritage awareness through VR serious gaming: A study on promoting Saudi heritage among the younger generation. J. Infrastruct. Policy Dev. 2024, 8, 3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, W.Y.J.; Leung, B.W.; Cheng, L. The motivational effects and educational affordance of serious games on the learning of Cantonese opera movements. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2024, 40, 1455–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, R. Validation of an SOR model for situation, enduring, and response components of involvement. J. Mark. Res. 1982, 19, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkpojiogu, E.O.C.; Okeke-Uzodike, O.E.; Abdullahi, M.J. Explaining the applicability of the Stimuli-Organism-Response (SOR) framework in UX processes for static and dynamic contexts. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Interdisciplinary Approaches in Technology and Management for Social Innovation (IATMSI), Gwalior, India, Gwalior, India, 14–16 March 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby, J. Stimulus-organism-response reconsidered: An evolutionary step in modeling (consumer) behavior. J. Consum. Psychol. 2002, 12, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triantoro, T.; Gopal, R.; Benbunan-Fich, R.; Lang, G. Would you like to play? A comparison of a gamified survey with a traditional online survey method. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 49, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Xing, J. The impact of gamification motivation on green consumption behavior—An empirical study based on ant forest. Sustainability 2022, 15, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatautis, R.; Vitkauskaite, E.; Gadeikiene, A.; Piligrimiene, Z. Gamification as a mean of driving online consumer behaviour: SOR model perspective. Eng. Econ. 2016, 27, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.G.; Moon, Y.J. Customers’ cognitive, emotional, and actionable response to the servicescape: A test of the moderating effect of the restaurant type. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, R. Serious games. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, J. Designing Interactive Games based on Intangible Cultural Heritage: A Case Study on Chinese Nuo Culture. In Proceedings of the Eleventh International Symposium of Chinese CHI, Denpasar, Indonesia, 13–16 November 2023; pp. 622–625. [Google Scholar]

- Mokha, A.K.; Kumar, P. Examining the interconnections between E-CRM, customer experience, customer satisfaction and customer loyalty: A mediation approach. J. Electron. Commer. Organ. (JECO) 2022, 20, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajh, S.P. Comparison of perceived value structural models. Mark./Tržište 2012, 24, 117–133. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, C.M.; Wang, E.T.; Fang, Y.H.; Huang, H.Y. Understanding customers’ repeat purchase intentions in B2C e-commerce: The roles of utilitarian value, hedonic value and perceived risk. Inf. Syst. J. 2014, 24, 85–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, B.; Qin, J. From digital museuming to on-site visiting: The mediation of cultural identity and perceived value. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1111917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorderer, P.; Klimmt, C.; Ritterfeld, U. Enjoyment: At the heart of media entertainment. Commun. Theory 2004, 14, 388–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, R.L.; Krcmar, M. Conceptualizing media enjoyment as attitude: Implications for mass media effects research. Commun. Theory 2004, 14, 288–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Davis, F.D. A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: Four longitudinal field studies. Manag. Sci. 2000, 46, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halwani, L.; Cherry, A. A consumer perspective on brand authenticity: Insight into drivers and barriers. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2024, 19, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. Authenticity and commoditization in tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1988, 15, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southworth, S.S. US consumers’ perception of Asian brands’ cultural authenticity and its impact on perceived quality, trust, and patronage intention. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2019, 31, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, D.; Wang, Q.; Law, R.; Zhang, M. Influence of cultural identity on tourists’ authenticity perception, tourist satisfaction, and traveler loyalty. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trilling, L.; Howe, I.; Farber, L.H.; Hamilton, W.; Orrill, R.; Boyers, R. Sincerity and authenticity: A symposium. Salmagundi 1978, 41, 87–110. [Google Scholar]

- MacCannell, D. Staged authenticity: Arrangements of social space in tourist settings. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 79, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, K.K. Souvenirs of the American southwest: Objective or constructive authenticity? Tour. Souvenirs Glocal Perspect. Margins 2013, 33, 63. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Q.; Qian, J.; Zang, Y. Integrating intangible cultural heritage elements into mobile games: An exploration of player cultural identity. Inf. Technol. People 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, S.; Guèvremont, A. The dynamic nature of brand authenticity for a new brand: Creating and maintaining perceptions through iconic, indexical, and existential cues. J. Consum. Behav. 2024, 23, 1803–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeiler, X.; Mukherjee, S. Video game development in India: A cultural and creative industry embracing regional cultural heritage (s). Games Cult. 2022, 17, 509–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camuñas-García, D.; Cáceres-Reche, M.P.; de la Encarnación Cambil-Hernández, M.; Serrano-Arnáez, B. Impacto de los videojuegos narrativos en la percepción del patrimonio cultural: Un análisis cualitativo de Assassin’s Creed en estudiantes universitarios. REIDICS Rev. Investig. Didáctica Cienc. Soc. 2024, 15, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, M.; Li, R.; Richard, M.O.; Shao, M. Understanding Chinese consumers’ and Chinese immigrants’ purchase intentions toward global brands with Chinese elements. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2020, 30, 1077–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamel, M.N. Knowledge acquisition. In Encyclopedia of Computer Science and Technology, rev. ed.; Henderson, H., Ed.; Facts On File, Inc. (an imprint of Infobase Publishing): New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- García-Sánchez, E.; García-Morales, V.J.; Bolívar-Ramos, M.T. The influence of top management support for ICTs on organisational performance through knowledge acquisition, transfer, and utilisation. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2017, 11, 19–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Guo-Jie, H. The Impact of Knowledge Acquisition and Knowledge Integration of IT Outsourcing Supplier on Outsourcing Success—Knowledge Sticky’s Moderating Effect. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Service Science (ICSS), Weihai, China, 8–9 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Y.; Song, B.; Zhu, Y.; Yu, L.; Hu, Y. Acquiring musical knowledge increases music liking: Evidence from a neurophysiological study. PsyCh J. 2024, 13, 927–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, L.A. The playful child: Measurement of a disposition to play. Play. Cult. 1991, 4, 51–74. [Google Scholar]

- Byun, K.A.; Dass, M.; Kumar, P.; Kim, J. An examination of innovative consumers’ playfulness on their pre-ordering behavior. J. Consum. Mark. 2017, 34, 226–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller-Stewens, J.; Schlager, T.; Häubl, G.; Herrmann, A. Gamified information presentation and consumer adoption of product innovations. J. Mark. 2017, 81, 8–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merikivi, J.; Tuunainen, V.; Nguyen, D. What makes continued mobile gaming enjoyable? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 68, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.Y.; Lin, S.S.; Ye, S.; Zhou, L.Q.; Ren, Y.T. Residents’ intention to support tourism in ethnic villages from the perspective of Tiadic. Luyou Xuekan, 2022; advance online publication. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Deeprasert, J.; Jiang, S. Cultural Identity, Experience Quality and Revisit Intention to Mount Tai as A Heritage Tourism Destinations: Mediation Roles of Perceived Value, Perceived Destination Image and Satisfaction. J. Ecohumanism 2024, 3, 586–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrick, J.F. The roles of quality, value, and satisfaction in predicting cruise passengers’ behavioral intentions. J. Travel Res. 2004, 42, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrukhina, A.S.; Shangua, I.E. Traditions and modernity: Cultural self-awareness. Soc. Philos. Hist. Cult. 2024, 10, 292–298. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, W.; Luo, X. The influence of domestic brand advertising strategy on new product diffusion: Based on the role of cultural identity and self-expression. Mark. Manag. 2022, 6, 87–90. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, N. From popular culture to traditional culture: Learning through video games. In Proceedings of the European Conference of Games Based Learning, Scotland, UK, 25–26 October 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Swoboda, B.; Pennemann, K.; Taube, M. The effects of perceived brand globalness and perceived brand localness in China: Empirical evidence on Western, Asian, and domestic retailers. J. Int. Mark. 2012, 20, 72–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Wu, S.; Liu, R.; Zheng, F. Understanding users’ behavior intention of serious games for intangible cultural heritage based on the stimulus-organism-response model. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2025, 41, 5137–5149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.W.; Kim, Y.G. Extending the TAM for a World-Wide-Web context. Inf. Manag. 2001, 38, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Podlog, L.; Huang, C. Associations among children’s situational motivation, physical activity participation, and enjoyment in an active dance video game. J. Sport Health Sci. 2013, 2, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, I.; Yoon, Y.; Choi, M. Determinants of adoption of mobile games under mobile broadband wireless access environment. Inf. Manag. 2007, 44, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J. Why do people buy virtual goods? Attitude toward virtual good purchases versus game enjoyment. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2015, 35, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hew, J.J.; Leong, L.Y.; Tan, G.W.H.; Lee, V.H.; Ooi, K.B. Mobile social tourism shopping: A dual-stage analysis of a multi-mediation model. Tour. Manag. 2018, 66, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.C.; Tsai, T.R. What drives people to continue to play online games? An extension of technology model and theory of planned behavior. Intl. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2010, 26, 601–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Jeyaraj, A. Information technology adoption and continuance: A longitudinal study of individuals’ behavioral intentions. Inf. Manag. 2013, 50, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coanhas, A.; Silva, C.; Zagalo, N. Almeida Star Defense: A Combination of History and Game for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Digital and Interactive Arts, Faro, Portugal, 28–30 November 2023; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.; Dong, X. Digital Approaches to Inclusion and Participation in Cultural Heritage: Insights from Research and Practice in Europe; Giglitto, D., Ciolfi, L., Lockley, E., Kaldeli, E., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2023; p. 262. ISBN 9781032234380. [Google Scholar]

- Kerlinger, F.N. Foundations of Behavioral Research; Surgeet Publications: Delhi, India, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Leighton, K.; Kardong-Edgren, S.; Schneidereith, T.; Foisy-Doll, C. Using social media and snowball sampling as an alternative recruitment strategy for research. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2021, 55, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Emran, M.; Teo, T. Do knowledge acquisition and knowledge sharing really affect e-learning adoption? An empirical study. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2020, 25, 1983–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boo, S.; Busser, J.; Baloglu, S. A model of customer-based brand equity and its application to multiple destinations. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.X. The impact of tourist participation on service quality of travel agencies and tourist satisfaction: An empirical study in Beijing Tianjin and Hebei Province. Areal Res. Dev. 2012, 31, 117–123. [Google Scholar]

- Darvishmotevali, M.; Tajeddini, K.; Altinay, L. Experiential festival attributes, perceived value, cultural exploration, and behavioral intentions to visit a food festival. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2023, 24, 57–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Chen, Q.; Huang, X.; Xie, M.; Guo, Q. How do aesthetics and tourist involvement influence cultural identity in heritage tourism? The mediating role of mental experience. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 990030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaker, G.; Vinzi, V.E.; O’Connor, P. Examining the effect of novelty seeking, satisfaction, and destination image on tourists’ return pattern: A two factor, non-linear latent growth model. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 890–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, T.; Hong, M.; Pedersen, P.M. Effects of perceived interactivity and web organization on user attitudes. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2014, 14, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D. How visitors perceive heritage value—A quantitative study on visitors’ perceived value and satisfaction of architectural heritage through SEM. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Wang, Q.; Long, Y. Exploring the key drivers of user continuance intention to use digital museums: Evidence from China’s Sanxingdui museum. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 81511–81526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayyaz, M.S.; Abbasi, A.Z.; Ahmad, R.; Qummar, M.H.; Tsiotsou, R.H.; Mahmood, S. Gamers’ gratifications and continuous intention to play eSports: The mediating role of gamers’ satisfaction—A PLS-SEM and NCA study. Int. J. Sports Mark. Spons. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, J.S.; Overton, T.S. Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. J. Mark. Res. 1977, 14, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. Partial least squares structural equation modeling. Handb. Mark. Res. 2017, 26, 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill Companies: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Neter, J.; Wasserman, W.; Kutner, M.H. Applied Linear Statistical Models: Regression, Analysis of Variance, and Experimental Designs, 3rd ed.; Irwin: Homewood, IL, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, P.S.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Tan, G.W.H.; Ooi, K.B.; Aw, E.C.X.; Metri, B. Why do consumers buy impulsively during live streaming? A deep learning-based dual-stage SEM-ANN analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 147, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, A.Y.L. Predicting m-commerce adoption determinants: A neural network approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 2013, 40, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.; Wang, X. Exploring the impact of AI enhancement on the sports app community: Analyzing human-computer interaction and social factors using a hybrid SEM-ANN approach. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2024, 40, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.K.; Singh, G.; Sadeque, S.; Harrigan, P.; Coussement, K. Customer engagement with digitalized interactive platforms in retailing. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 164, 114001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, N.F.; Hauff, S. Necessary conditions in international business research–Advancing the field with a new perspective on causality and data analysis. J. World Bus. 2022, 57, 101310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dul, J.; Van der Laan, E.; Kuik, R. A statistical significance test for necessary condition analysis. Organ. Res. Methods 2020, 23, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Si, H.; Xia, X. Understanding the non-users’ acceptability of autonomous vehicle hailing services using SEM-ANN-NCA approach. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2025, 110, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, L.Y.; Hew, T.S.; Ooi, K.B.; Chau, P.Y. To share or not to share?–A hybrid SEM-ANN-NCA study of the enablers and enhancers for mobile sharing economy. Decis. Support Syst. 2024, 180, 114185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, T.G.; Hamari, J.; Kesharwani, A.; Tak, P. Understanding continuance intention to play online games: Roles of self-expressiveness, self-congruity, self-efficacy, and perceived risk. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2022, 41, 348–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Yang, X.; Fu, S.; Huan, T.C.T. Exploring the influence of tourists’ happiness on revisit intention in the context of Traditional Chinese Medicine cultural tourism. Tour. Manag. 2023, 94, 104647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhan, Q.; Pashkevych, K. Exploring the Key Factors Influencing the Continuance Use of Serious Games of Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH). Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, C.M.; Perrotta, A.; Pais-Vieira, C. Serious games for physical rehabilitation: Aesthetic discrepancies between custom-made serious games and commercial titles used for healthcare. J. Sci. Technol. Arts 2022, 14, 29–50. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y. Application and challenge of serious games in education. E-Educ. Res. 2011, 4, 88–90. [Google Scholar]

- He, T.L.; Qin, F. Exploring how the metaverse of cultural heritage (MCH) influences users’ intentions to experience offline: A two-stage SEM-ANN analysis. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titah, R.; Barki, H. Nonlinearities between attitude and subjective norms in information technology acceptance: A negative synergy? Mis Q. 2009, 33, 827–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, N.F.; Schubring, S.; Hauff, S.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. When predictors of outcomes are necessary: Guidelines for the combined use of PLS-SEM and NCA. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2020, 120, 2243–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergh, D.D.; Boyd, B.K.; Byron, K.; Gove, S.; Ketchen, D.J., Jr. What constitutes a methodological contribution? J. Manag. 2022, 48, 1835–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Option | Items | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Authenticity of Cultural Elements (ACE) | ACE1 | The digital representations of ancient architecture presented in CH-SGs were perceived as highly realistic. | [75] |

| ACE2 | The visual scenes in CH-SGs were characterized by a diverse array of traditional cultural elements, including architectural ruins, figures, color schemes, and motifs. | ||

| ACE3 | The historical context and traditional aesthetics of the ancient architectural sites were found to align with my cultural understanding. | ||

| Knowledge Acquisition (KA) | KA1 | New knowledge pertaining to architectural cultural heritage was acquired through CH-SGs. | [43,76] |

| KA2 | Specific cultural symbols and markers of ancient architectural sites were identified within the game. | ||

| KA3 | The level design of the serious game was optimized to facilitate the learning process of heritage knowledge. | ||

| KA4 | CH-SGs provide multidimensional pathways for the acquisition of cultural knowledge. | ||

| Perceived Playfulness (PP) | PP1 | Engagement interest was stimulated by the cultural content presented in CH-SGs. | [43,53] |

| PP2 | The game experience enhanced curiosity regarding the aesthetics of architectural heritage sites. | ||

| PP3 | Participation in CH-SGs elicited a sense of enjoyment. | ||

| PP4 | Completion of game tasks in CH-SGs was perceived as genuinely enjoyable. | ||

| Design Aesthetics (DA) | DA1 | Profound significance was conveyed by the architectural cultural symbols presented in the game. | [53] |

| DA2 | Aesthetic pleasure was provided by the visual design of the ancient architectural elements. | ||

| DA3 | The crafted scenes of ancient architectural sites, along with the game’s artwork and sound effects, enabled deeper immersion in the game world. | ||

| DA4 | Engagement with the game’s narrative was enhanced by the integration of ancient architectural cultural elements. | ||

| Perceived Value (PV) | PV1 | Significant cultural and educational value is afforded by CH-SGs. | [77,78,79] |

| PV2 | Positive psychological responses are elicited by the game experience. | ||

| PV3 | Participation in CH-SGs is perceived as a worthwhile investment of time. | ||

| PV4 | Deeper value is provided by CH-SGs in comparison with entertainment games. | ||

| Cultural Identity (CI) | CI1 | A sense of pride was experienced regarding the architectural cultural heritage presented in CH-SGs. | [80] |

| CI2 | A willingness was expressed to further explore the cultural connotations of ancient architectural sites within CH-SGs. | ||

| CI3 | It is believed that the CH-SG gaming experience can effectively enhance national cultural confidence. | ||

| CI4 | Continued time will be devoted to exploring the cultural depictions of ancient architectural sites in the game. | ||

| Perceived Enjoyment (PE) | PE1 | Participation in CH-SGs was perceived to confer mental relaxation. | [81,82,83] |

| PE2 | The gameplay process was perceived as highly enjoyable. | ||

| PE3 | The gaming experience was perceived to generate pleasurable memories. | ||

| PE4 | The overall engagement with CH-SGs was greatly enjoyed. | ||

| Game Continuance Intention (GCI) | GCI1 | The continued engagement with CH-SGs was perceived as highly valuable. | [84,85] |

| GCI2 | It was intended that serious games for ancient architectural heritage would be played in the future. | ||

| GCI3 | It was planned to experience as many ancient architectural site scenes in CH-SGs as possible. | ||

| GCI4 | A strong recommendation of CH-SGs to others was intended. |

| Item | Number | Proportion |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 286 | 53.76% |

| Female | 246 | 46.24% |

| Age | ||

| 18–25 | 227 | 42.67% |

| 26–35 | 165 | 31.03% |

| 35–45 | 97 | 18.23% |

| 46–55 | 35 | 6.57% |

| 55–60 | 8 | 1.51% |

| Education background | ||

| High school and below | 53 | 9.96% |

| University college | 148 | 27.82 |

| University undergraduate | 213 | 40.03% |

| Master and above | 118 | 22.19% |

| Degree of familiarity with CH-SGs | ||

| Completely unfamiliar: never played | 2 | 0.37% |

| Slightly unfamiliar: rarely played | 16 | 3.01% |

| Medium: some experience | 257 | 48.3% |

| Familiarity: often played | 162 | 30.5% |

| Very familiar: play regularly | 95 | 17.82% |

| The frequency of using CH-SG | ||

| Never experienced | 5 | 0.93% |

| 1–2 times | 49 | 9.21% |

| 3–5 times | 82 | 15.41% |

| 6–10 times | 169 | 31.77% |

| More than 10 times | 227 | 42.68% |

| Total | 532 | 100% |

| Variables | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | AVE | VIF | Items | Factor Loading |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authenticity of Cultural Elements | 0.908 | 0.908 | 0.844 | 3.177 | ACE1 | 0.916 |

| 3.790 | ACE2 | 0.937 | ||||

| 2.574 | ACE3 | 0.902 | ||||

| Knowledge Acquisition | 0.916 | 0.919 | 0.799 | 2.683 | KA1 | 0.881 |

| 3.537 | KA2 | 0.913 | ||||

| 3.965 | KA3 | 0.922 | ||||

| 2.661 | KA4 | 0.858 | ||||

| Perceived Playfulness | 0.908 | 0.910 | 0.784 | 2.627 | PP1 | 0.859 |

| 3.346 | PP2 | 0.899 | ||||

| 3.136 | PP3 | 0.895 | ||||

| 2.835 | PP4 | 0.887 | ||||

| Design Aesthetics | 0.907 | 0.914 | 0.782 | 2.302 | DA1 | 0.846 |

| 3.159 | DA2 | 0.898 | ||||

| 3.264 | DA3 | 0.914 | ||||

| 2.576 | DA4 | 0.878 | ||||

| Perceived Value | 0.850 | 0.863 | 0.688 | 1.789 | PV1 | 0.828 |

| 2.166 | PV2 | 0.857 | ||||

| 2.446 | PV3 | 0.864 | ||||

| 1.885 | PV4 | 0.767 | ||||

| Cultural Identity | 0.875 | 0.880 | 0.728 | 2.356 | CI1 | 0.852 |

| 2.956 | CI 2 | 0.896 | ||||

| 2.370 | CI 3 | 0.861 | ||||

| 1.909 | CI 4 | 0.801 | ||||

| Perceived Enjoyment | 0.861 | 0.871 | 0.706 | 1.928 | PE1 | 0.837 |

| 2.334 | PE2 | 0.868 | ||||

| 2.395 | PE3 | 0.857 | ||||

| 1.994 | PE4 | 0.796 | ||||

| Game Continuance Intention | 0.893 | 0.903 | 0.757 | 2.367 | GCI1 | 0.872 |

| 2.891 | GCI 2 | 0.899 | ||||

| 2.959 | GCI 3 | 0.894 | ||||

| 2.092 | GCI 4 | 0.813 |

| ACE | CI | DA | GCI | KA | PE | PP | PV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACE | 0.919 | |||||||

| CI | 0.289 | 0.853 | ||||||

| DA | 0.044 | 0.229 | 0.884 | |||||

| GCI | 0.177 | 0.407 | 0.228 | 0.870 | ||||

| KA | 0.000 | 0.283 | −0.054 | 0.185 | 0.894 | |||

| PE | 0.229 | 0.242 | 0.185 | 0.369 | 0.318 | 0.840 | ||

| PP | −0.006 | 0.221 | −0.045 | 0.204 | 0.059 | 0.284 | 0.885 | |

| PV | 0.138 | 0.147 | 0.125 | 0.414 | 0.139 | 0.188 | 0.156 | 0.830 |

| Hypothesis | Path Coefficient | p-Values | t-Values | Confidence Interval | Hypothesis | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5% | 97.5% | |||||

| ACE→PV | 0.133 *** | 0.001 | 3.310 | 0.052 | 0.209 | Supported |

| ACE→CI | 0.280 *** | 0.000 | 7.699 | 0.208 | 0.349 | Supported |

| ACE→PE | 0.222 *** | 0.000 | 5.957 | 0145 | 0.293 | Supported |

| KA→PV | 0.137 ** | 0.003 | 2.927 | 0.042 | 0.224 | Supported |

| KA→CI | 0.283 *** | 0.000 | 8.515 | 0.218 | 0.348 | Supported |

| KA→PE | 0.313 *** | 0.000 | 8.321 | 0.237 | 0.385 | Supported |

| PP→PV | 0.155 *** | 0.000 | 4.042 | 0.080 | 0.230 | Supported |

| PP→CI | 0.217 *** | 0.000 | 6.028 | 0.145 | 0.286 | Supported |

| PP→ PE | 0.276 *** | 0.000 | 7.349 | 0.197 | 0.345 | Supported |

| DA→PV | 0.133 ** | 0.001 | 3.328 | 0.052 | 0.210 | Supported |

| DA→CI | 0.242 *** | 0.000 | 6.481 | 0.169 | 0.312 | Supported |

| DA→PE | 0.205 *** | 0.000 | 5.726 | 0.134 | 0.275 | Supported |

| PV→GCI | 0.325 *** | 0.000 | 7.441 | 0.239 | 0.412 | Supported |

| CI→GCI | 0.302 *** | 0.000 | 7.833 | 0.227 | 0.376 | Supported |

| PE→GCI | 0.235 *** | 0.000 | 6.424 | 0.164 | 0.306 | Supported |

| Neural Network | Model A | Model B | Model C | Model D | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input: ACE, KA, PP, DA | Input: ACE, KA, PP, DA | Input: ACE, KA, PP, DA | Input: PV, CI, PE | |||||

| Output: PV | Output: CI | Output: PE | Output: GCI | |||||

| Training | Testing | Training | Testing | Training | Testing | Training | Testing | |

| ANN1 | 0.468 | 0.430 | 0.374 | 0.341 | 0.368 | 0.369 | 0.325 | 0.355 |

| ANN2 | 0.453 | 0.536 | 0.366 | 0.349 | 0.371 | 0.396 | 0.317 | 0.375 |

| ANN3 | 0.446 | 0.688 | 0.369 | 0.345 | 0.378 | 0.274 | 0.334 | 0.296 |

| ANN4 | 0.467 | 0.629 | 0.380 | 0.544 | 0.369 | 0.388 | 0.332 | 0.296 |

| ANN5 | 0.438 | 0.468 | 0.379 | 0.377 | 0.379 | 0.349 | 0.344 | 0.211 |

| ANN6 | 0.501 | 0.346 | 0.375 | 0.291 | 0.443 | 0.414 | 0.348 | 0.326 |

| ANN7 | 0.483 | 0.401 | 0.371 | 0.408 | 0.372 | 0.320 | 0.337 | 0.284 |

| ANN8 | 0.465 | 0.956 | 0.364 | 0.509 | 0.375 | 0.434 | 0.315 | 0.557 |

| ANN9 | 0.463 | 0.389 | 0.372 | 0.370 | 0.376 | 0.312 | 0.332 | 0.335 |

| ANN10 | 0.494 | 0.380 | 0.366 | 0.356 | 0.401 | 0.407 | 0.334 | 0.416 |

| Mean | 0.468 | 0.522 | 0.372 | 0.393 | 0.381 | 0.362 | 0.332 | 0.345 |

| SD | 0.020 | 0.189 | 0.005 | 0.083 | 0.023 | 0.052 | 0.011 | 0.093 |

| Neural Network | Model A (Output: PV) | Model B (Output: CI) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACE | KA | PP | DA | ACE | KA | PP | DA | |

| ANN1 | 0.234 | 0.240 | 0.239 | 0.287 | 0.224 | 0.291 | 0.253 | 0.231 |

| ANN2 | 0.227 | 0.183 | 0.302 | 0.289 | 0.270 | 0.252 | 0.208 | 0.271 |

| ANN3 | 0.230 | 0.196 | 0.337 | 0.237 | 0.257 | 0.270 | 0.210 | 0.264 |

| ANN4 | 0.362 | 0.200 | 0.164 | 0.274 | 0.285 | 0.303 | 0.210 | 0.202 |

| ANN5 | 0.300 | 0.149 | 0.266 | 0.285 | 0.267 | 0.265 | 0.245 | 0.224 |

| ANN6 | 0.242 | 0.097 | 0.546 | 0.115 | 0.254 | 0.309 | 0.212 | 0.225 |

| ANN7 | 0.218 | 0.226 | 0.101 | 0.455 | 0.260 | 0.294 | 0.221 | 0.225 |

| ANN8 | 0.313 | 0.159 | 0.311 | 0.217 | 0.314 | 0.277 | 0.166 | 0.243 |

| ANN9 | 0.325 | 0.194 | 0.232 | 0.249 | 0.248 | 0.253 | 0.224 | 0.275 |

| ANN10 | 0.182 | 0.349 | 0.232 | 0.236 | 0.287 | 0.284 | 0.224 | 0.205 |

| RI | 0.263 | 0.199 | 0.273 | 0.264 | 0.267 | 0.280 | 0.217 | 0.237 |

| NI (%) | 96.336 | 72.893 | 100.000 | 96.703 | 95.281 | 100.000 | 77.663 | 84.532 |

| Neural Network | Model C (Output: PE) | Model D (Output: GCI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACE | KA | PP | DA | PV | CI | PE | |

| ANN1 | 0.231 | 0.257 | 0.274 | 0.238 | 0.483 | 0.263 | 0.253 |

| ANN2 | 0.227 | 0.274 | 0.274 | 0.224 | 0.436 | 0.300 | 0.265 |

| ANN3 | 0.221 | 0.282 | 0.271 | 0.236 | 0.261 | 0.340 | 0.399 |

| ANN4 | 0.218 | 0.281 | 0.282 | 0.219 | 0.369 | 0.307 | 0.324 |

| ANN5 | 0.201 | 0.302 | 0.273 | 0.224 | 0.422 | 0.378 | 0.200 |

| ANN6 | 0.424 | 0.087 | 0.391 | 0.097 | 0.366 | 0.392 | 0.242 |

| ANN7 | 0.242 | 0.265 | 0.272 | 0.221 | 0.370 | 0.339 | 0.291 |

| ANN8 | 0.187 | 0.285 | 0.273 | 0.256 | 0.377 | 0.298 | 0.325 |

| ANN9 | 0.209 | 0.296 | 0.284 | 0.211 | 0.385 | 0.353 | 0.262 |

| ANN10 | 0.337 | 0350 | 0.292 | 0.020 | 0.451 | 0.316 | 0.233 |

| RI | 0.250 | 0.268 | 0.289 | 0.195 | 0.392 | 0.329 | 0.279 |

| NI (%) | 86.505 | 92.733 | 100.000 | 67.474 | 100.000 | 83.928 | 71.177 |

| PLS-SEM Path | PLS-SEM Path Coefficient | ANN Normalized Relative Importance (%) | Ranking (PLS-SEM) | Ranking (ANN) | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model A (Output: PV) | |||||

| ACE→PV | 0.133 | 96.336 | 3 | 3 | Match |

| KA→PV | 0.137 | 72.893 | 2 | 4 | |

| PP→PV | 0.155 | 100.000 | 1 | 1 | Match |

| DA→PV | 0.133 | 96.703 | 4 | 2 | |

| Model B (Output: CI) | |||||

| ACE→CI | 0.280 | 95.281 | 2 | 2 | Match |

| KA→CI | 0.283 | 100.000 | 1 | 1 | Match |

| PP→CI | 0.217 | 77.663 | 4 | 4 | Match |

| DA→CI | 0.242 | 84.532 | 3 | 3 | Match |

| Model C (Output: PE) | |||||

| ACE→PE | 0.222 | 86.505 | 3 | 3 | Match |

| KA→PE | 0.313 | 92.733 | 1 | 2 | |

| PP→PE | 0.276 | 100.000 | 2 | 1 | |

| DA→PE | 0.205 | 67.474 | 4 | 4 | Match |

| Model D (Output: GCI) | |||||

| PV→GCI | 0.325 | 100.000 | 1 | 1 | Match |

| CI→GCI | 0.302 | 83.928 | 2 | 2 | Match |

| PE→GCI | 0.235 | 71.177 | 3 | 3 | Match |

| Parameters | Ceiling Zone | Scope | Effect Size | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACE→PV | 2.080 | 25.0 | 0.083 | 0.481 |

| KA→PV | 1.390 | 18.5 | 0.075 | 0.566 |

| PP→PV | 2.360 | 19.0 | 0.124 | 0.020 |

| DA→PV | 1.710 | 20.0 | 0.086 | 0.107 |

| ACE→CI | 1.690 | 22.5 | 0.075 | 0.031 |

| KA→CI | 1.190 | 16.7 | 0.071 | 0.037 |

| PP→CI | 1.450 | 17.1 | 0.085 | 0.009 |

| DA→CI | 1.040 | 18.0 | 0.058 | 0.044 |

| ACE→PE | 2.410 | 22.5 | 0.107 | 0.001 |

| KA→PE | 1.250 | 16.7 | 0.075 | 0.148 |

| PP→PE | 1.270 | 17.1 | 0.074 | 0.193 |

| DA→PE | 1.100 | 18.0 | 0.061 | 0.160 |

| PV→GCI | 4.560 | 25.0 | 0.182 | 0.250 |

| CI→GCI | 4.670 | 22.5 | 0.208 | 0.114 |

| PE→GCI | 6.450 | 22.5 | 0.287 | 0.026 |

| ACE | KA | PP | DA | CI | PE | PU | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Value | |||||||

| 0 | NN | NN | NN | NN | |||

| 10 | NN | NN | NN | NN | |||

| 20 | NN | NN | NN | NN | |||

| 30 | NN | NN | NN | NN | |||

| 40 | NN | NN | NN | NN | |||

| 50 | NN | NN | NN | NN | |||

| 60 | NN | NN | NN | NN | |||

| 70 | NN | NN | NN | NN | |||

| 80 | 14.0 | 6.8 | 24.4 | 8.1 | |||

| 90 | 30.4 | 34.7 | 51.2 | 36.0 | |||

| 100 | 46.8 | 62.7 | 78.8 | 63.9 | |||

| Cultural Identity | |||||||

| 0 | NN | NN | NN | NN | |||

| 10 | NN | NN | NN | NN | |||

| 20 | NN | NN | NN | NN | |||

| 30 | NN | NN | NN | NN | |||

| 40 | NN | NN | NN | NN | |||

| 50 | NN | NN | NN | NN | |||

| 60 | NN | NN | NN | NN | |||

| 70 | NN | NN | NN | NN | |||

| 80 | 13.8 | 8.3 | 3.3 | 7.6 | |||

| 90 | 28.3 | 26.7 | 30.3 | 23.9 | |||

| 100 | 42.7 | 45.1 | 57.3 | 40.2 | |||

| Perceived Enjoyment | |||||||

| 0 | NN | NN | NN | NN | |||

| 10 | NN | NN | NN | NN | |||

| 20 | NN | NN | NN | NN | |||

| 30 | NN | NN | NN | NN | |||

| 40 | NN | NN | NN | NN | |||

| 50 | NN | NN | NN | NN | |||

| 60 | NN | NN | NN | NN | |||

| 70 | NN | NN | NN | NN | |||

| 80 | 15.3 | NN | 2.3 | NN | |||

| 90 | 45.3 | 25.5 | 31.9 | 24.1 | |||

| 100 | 75.3 | 51.8 | 61.5 | 51.7 | |||

| Game Continuance Intention | |||||||

| 0 | NN | NN | NN | ||||

| 10 | NN | NN | NN | ||||

| 20 | NN | NN | NN | ||||

| 30 | NN | NN | NN | ||||

| 40 | NN | NN | NN | ||||

| 50 | NN | NN | 7.4 | ||||

| 60 | NN | NN | 22.4 | ||||

| 70 | 14.4 | 21.3 | 37.3 | ||||

| 80 | 37.8 | 43.4 | 52.3 | ||||

| 90 | 61.2 | 65.5 | 67.2 | ||||

| 100 | 84.6 | 87.6 | 82.1 | ||||

| Relationship | PLS-SEM | ANN | NCA |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACE→PV | Significant | Third important | Not Necessary |

| KA→PV | Significant | Fourth important | Not Necessary |

| PP→PV | Significant | First important | Necessary |

| DA→PV | Significant | Second important | Not Necessary |

| ACE→CI | Significant | Second important | Not Necessary |

| KA→CI | Significant | First important | Not Necessary |

| PP→CI | Significant | Fourth important | Not Necessary |

| DA→CI | Significant | Third important | Not Necessary |

| ACE→PE | Significant | Third important | Necessary |

| KA→PE | Significant | Second important | Not Necessary |

| PP→PE | Significant | First important | Not Necessary |

| DA→PE | Significant | Fourth important | Not Necessary |

| PV→GCI | Significant | First important | Not Necessary |

| CI→GCI | Significant | Second important | Not Necessary |

| PE→GCI | Significant | Third important | Necessary |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bao, Q.; Wang, S.; Nah, K.; Guo, W. Exploring the Key Factors Influencing the Plays’ Continuous Intention of Ancient Architectural Cultural Heritage Serious Games: An SEM–ANN–NCA Approach. Buildings 2025, 15, 2648. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15152648

Bao Q, Wang S, Nah K, Guo W. Exploring the Key Factors Influencing the Plays’ Continuous Intention of Ancient Architectural Cultural Heritage Serious Games: An SEM–ANN–NCA Approach. Buildings. 2025; 15(15):2648. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15152648

Chicago/Turabian StyleBao, Qian, Siqin Wang, Ken Nah, and Wei Guo. 2025. "Exploring the Key Factors Influencing the Plays’ Continuous Intention of Ancient Architectural Cultural Heritage Serious Games: An SEM–ANN–NCA Approach" Buildings 15, no. 15: 2648. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15152648

APA StyleBao, Q., Wang, S., Nah, K., & Guo, W. (2025). Exploring the Key Factors Influencing the Plays’ Continuous Intention of Ancient Architectural Cultural Heritage Serious Games: An SEM–ANN–NCA Approach. Buildings, 15(15), 2648. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15152648