Recognition and Evaluation of Architectural Heritage Value in Fujian Overseas Chinese New Villages

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

1.2. Literature Review

1.2.1. Research on Architectural Heritage of the 20th Century

1.2.2. Research on the Value of Architectural Heritage

| Related research | Time | Literature/Figures | Value System |

| 1902 | Alois Riegl [13] | The value of the era, historical value, commemorative value, practical value, and the new value created. | |

| 1933 | Charter of Athens [14] | With artistic, historical, and scientific interests | |

| 1964 | Venice Charter [15] | Cultural value, historical value, artistic value | |

| 1972 | World Heritage Convention [16] | It has outstanding universal value from the perspectives of history, art, science, conservation, and aesthetics | |

| 1975 | European Charter of the Architectural Heritage [17] | Spiritual value, social value, cultural value, economic value | |

| 1979 | Burra Charter [18] | Aesthetic value, historical value, scientific value, social value | |

| 1982 | Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Cultural Relics [19] | Historical value, artistic value, scientific value | |

| 1982 | Felton [20] | Architectural value, aesthetic value, historical value, documentary value, archaeological value, economic value, social value, political and spiritual, or symbolic value | |

| 1993 | Prukin [21] | Historical value, urban planning value, architectural aesthetic value, artistic sentiment value, scientific restoration value, functional value | |

| 1997 | Lü Zhou [22] | Historical value, artistic value, scientific value, cultural value, and emotional value | |

| 1998 | Zhu Guangya [23] | Historical value, scientific value, artistic value, spatial layout value, practical value | |

| 2000 | China’s Guidelines for the Conservation of Cultural Relics and Monuments [24] | Historical value, artistic value, scientific value, social value, cultural value | |

| 2004 | Wang Shiren [25] | Self-value (historical value), social value (use value) | |

| 2005 | Xi’an Declaration [26] | Formally propose the environmental value | |

| 2008 | Xu Songling [27] | Aesthetic value, spiritual value, historical value, sociological value, anthropological value, symbolic value, and economic value | |

| 2008 | Randall Mason [28] | Economic value and other cultural values | |

| 2018 | Xu Jinliang [29] | Intrinsic value (historical, scientific, artistic, environmental value), extrinsic value (social, cultural value), functional value | |

| 2022 | Edyta Łaszkiewicz [30] | Architectural value, functional value, aesthetic value, social value, and ecological value | |

| 2023 | Li Dengyue [31] | Basic value, core value, and ancillary value | |

| 2025 | Lu Jing [32] | Scientific value, artistic value, social value, and practical value | |

| 2025 | Qiao Xiaoyang [33] | Historical value, artistic value, scientific value, social value, cultural value |

1.2.3. Research Synthesis on Overseas Chinese New Village

1.3. Research Contributions

2. Materials and Methods

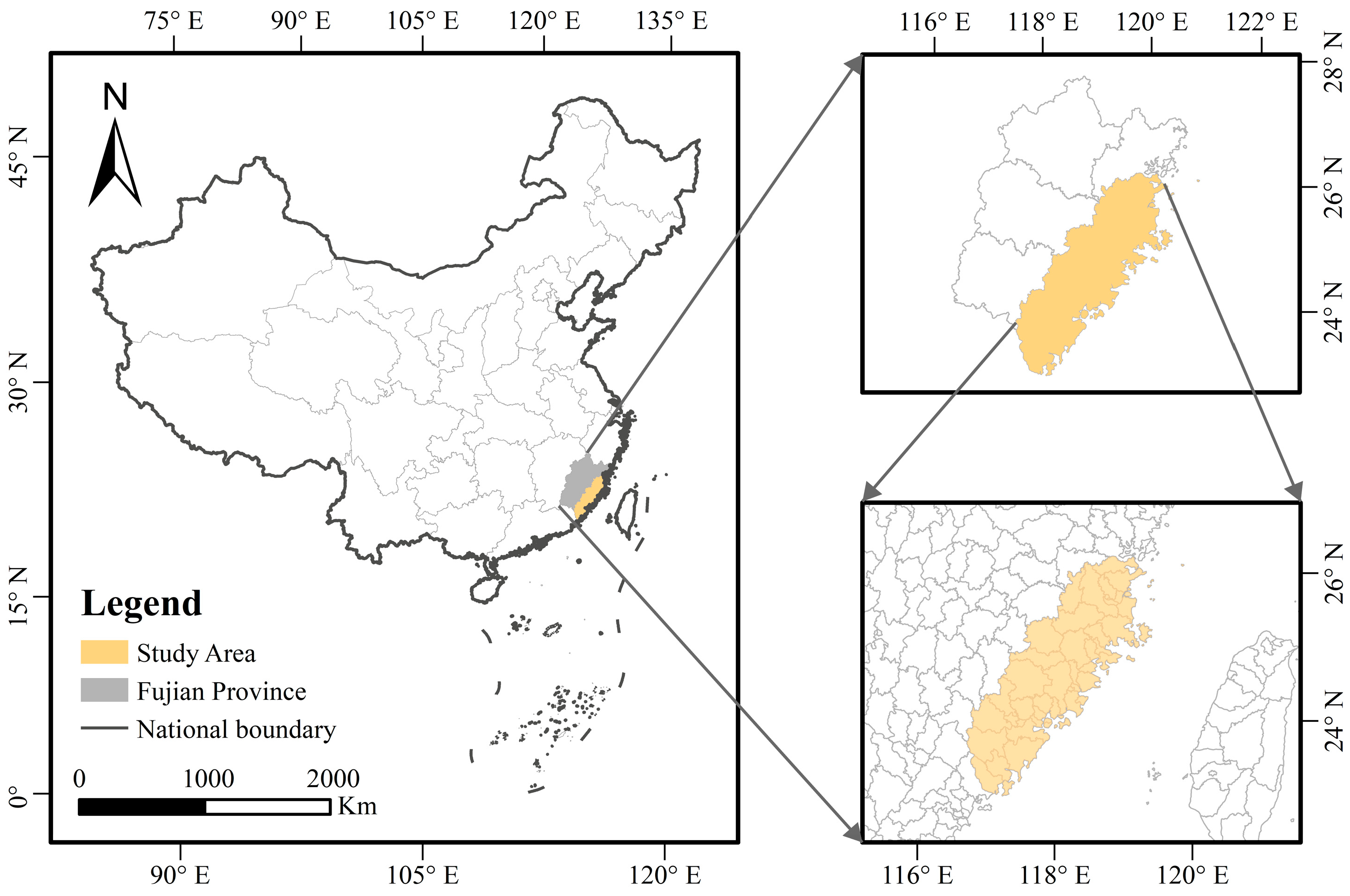

2.1. Research Subjects and Study Area

2.2. Research Design

2.2.1. Questionnaire Design

2.2.2. Data Processing

2.3. Research Methods

2.3.1. Literature Analysis Method

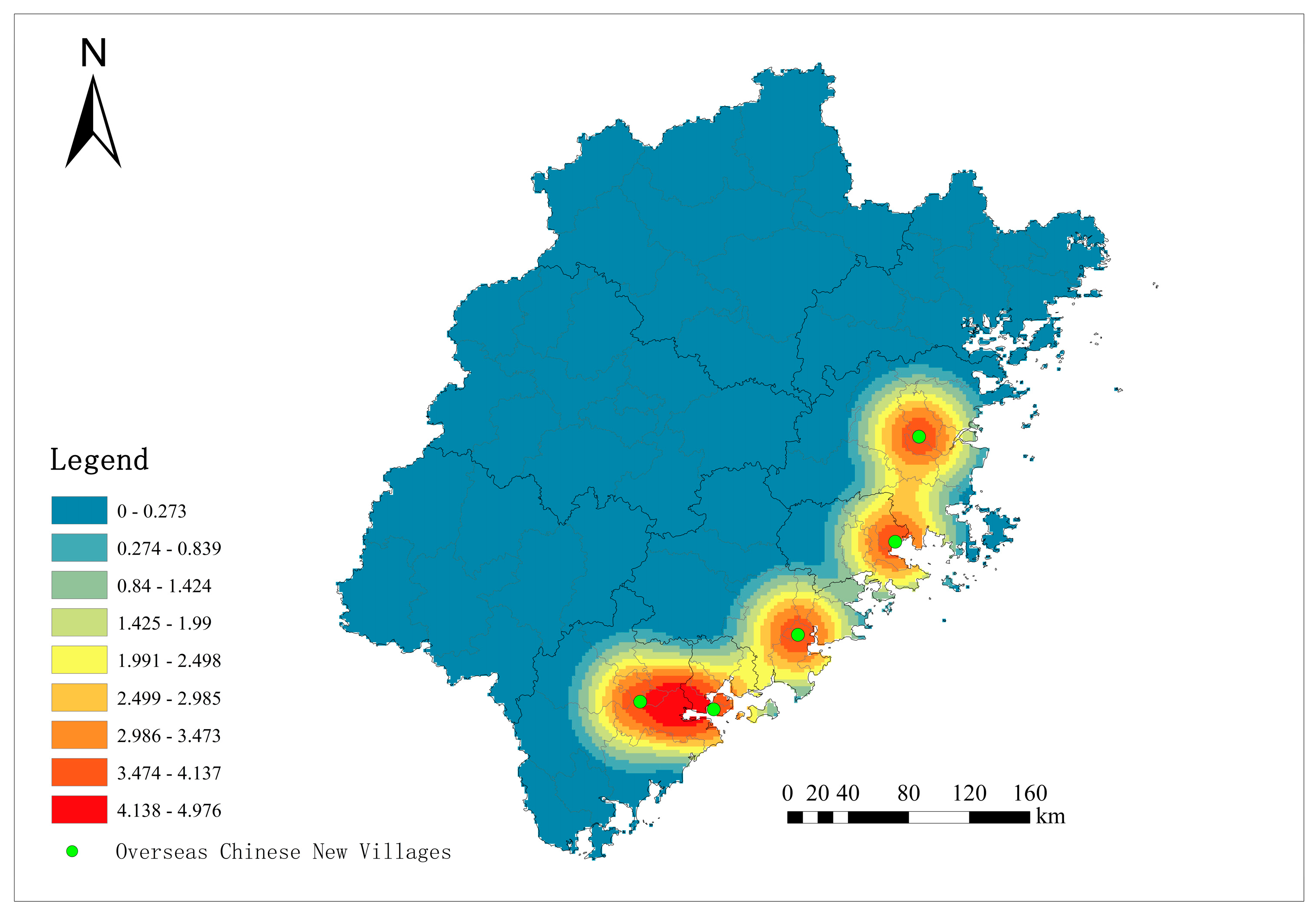

2.3.2. Kernel Density Estimation (KDE)

2.3.3. Delphi Method

2.3.4. Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP)

3. Results

3.1. Spatial Distribution of Fujian Overseas Chinese New Village

3.1.1. Distribution Analysis

3.1.2. Kernel Density Analysis

3.2. Value Recognition of Fujian Overseas Chinese New Village

3.3. Value Assessment of the Architectural Heritage in Fujian Overseas Chinese New Villages

3.3.1. Development of an Assessment Framework

3.3.2. Heritage Value Assessment of Fujian Overseas Chinese New Villages

4. Discussion

4.1. Practical Significance of Value Recognition

4.2. Discussion of Protection Recommendations

5. Conclusions

5.1. Research Conclusion

5.2. Limitations and Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| KDE | Kernel Density Estimation |

| AHP | Analytic Hierarchy Process |

Appendix A. Questionnaire on the Selection of Heritage Value Assessment Factors for Fujian Overseas Chinese New Village

| Personal Information | ||||

| Name | ||||

| Research direction | ||||

| Unit | ||||

| Contact information | ||||

| Heritage Value Assessment of Fujian Overseas Chinese New Village | ||||

| Objective Level | ||||

| The Heritage Value of Fujian Overseas Chinese New Village | Indicator Level | Element Stratum | Factor Stratum | Whether to Choose (√) |

| Ontological value | Historical value | Historical uses of buildings | ||

| Historical context | ||||

| Degree of historical correlation | ||||

| Age of antiquity | ||||

| The impact on the local historical development | ||||

| Historical figures and events | ||||

| The degree of reflecting the characteristics of The Times | ||||

| Remnants of historical environmental elements | ||||

| Artistic value | Architectural authenticity | |||

| Regional characteristics of architecture | ||||

| Architectural detailing and ornamentation | ||||

| Overall layout of architecture | ||||

| Appearance of architecture | ||||

| Architectural style and form | ||||

| Integrity of architecture | ||||

| Architectural creation | ||||

| Color and material of architecture | ||||

| Scientific value | Site selection for buildings | |||

| Scientific research value | ||||

| Building materials | ||||

| Rationality of building functions | ||||

| Building structure | ||||

| Reference and learning for contemporary times | ||||

| Building techniques | ||||

| Spatial layout of buildings | ||||

| Building scale | ||||

| Extrinsic value | Cultural value | Reflection of local cultural standards | ||

| Religious worship | ||||

| Cultural propaganda and education | ||||

| National belief | ||||

| Spiritual symbolism | ||||

| The value of intangible cultural heritage | ||||

| Cultural inheritance | ||||

| Social value | Social belonging | |||

| Functional applicability | ||||

| Social emotional attachment | ||||

| The rationality of current usage | ||||

| Social identity | ||||

| Connection to people’s livelihoods | ||||

| Social popularity | ||||

| Environmental value | Location and transport accessibility | |||

| The environment of the site itself | ||||

| Harmonization with the surrounding environment | ||||

| The degree of coordination with the surrounding environment | ||||

| The surrounding natural environment | ||||

| Functional Value | Functional Utility Value | Structural safety of the building | ||

| Completeness of supporting facilities | ||||

| Superiority of geographical location | ||||

| Rationality of functional layout | ||||

Appendix B. Score Sheet for Heritage Value Assessment of Fujian Overseas Chinese New Village

| Building Name | Total Assessment Score | Historical Value | Artistic Value | Scientific Value | Cultural Value | Social Value | Environmental Value | Functional Utility Value |

| No. 8 Huaxin Road, Xiamen | 81.08 | 22.88 | 12.09 | 6.00 | 16.69 | 4.55 | 3.21 | 15.66 |

| No. 9 Huaxin Road, Xiamen | 76.61 | 23.10 | 12.60 | 6.01 | 12.24 | 5.07 | 2.77 | 14.81 |

| No. 10 Huaxin Road, Xiamen | 88.28 | 26.92 | 14.53 | 5.78 | 16.74 | 5.67 | 3.02 | 15.61 |

| No. 11 Huaxin Road, Xiamen | 76.89 | 23.17 | 13.76 | 5.63 | 12.49 | 4.59 | 2.96 | 14.29 |

| No. 12 Huaxin Road, Xiamen | 74.75 | 21.59 | 11.86 | 6.01 | 11.56 | 5.21 | 3.08 | 15.45 |

| No. 13 Huaxin Road, Xiamen | 59.41 | 19.13 | 10.32 | 4.61 | 6.58 | 4.42 | 1.97 | 12.38 |

| No. 14 Huaxin Road, Xiamen | 55.18 | 18.36 | 5.57 | 7.18 | 11.70 | 2.21 | 2.44 | 7.70 |

| No. 15 Huaxin Road, Xiamen | 59.55 | 13.51 | 10.68 | 5.58 | 15.15 | 2.31 | 1.46 | 10.87 |

| No. 16 Huaxin Road, Xiamen | 84.34 | 25.88 | 12.56 | 5.44 | 16.75 | 5. 12 | 3.16 | 15.44 |

| No. 17 Huaxin Road, Xiamen | 83.65 | 26.78 | 13.60 | 5.75 | 15.80 | 4.38 | 2.99 | 14.35 |

| No. 18 Huaxin Road, Xiamen | 71.77 | 21.53 | 10.13 | 5.73 | 12.89 | 4.73 | 3.44 | 13.33 |

| No. 19 Huaxin Road, Xiamen | 81.78 | 23.59 | 11.55 | 6. 11 | 16.62 | 4.95 | 3.77 | 15.18 |

| No. 20 Huaxin Road, Xiamen | 80.62 | 22.67 | 14.30 | 5.63 | 15.28 | 5.49 | 3.56 | 13.68 |

| No. 21 Huaxin Road, Xiamen | 68.98 | 21.96 | 10.25 | 4.81 | 13.15 | 4.84 | 2.47 | 11.50 |

| No. 22 Huaxin Road, Xiamen | 54. 14 | 18.74 | 6.83 | 6.39 | 10.89 | 4.60 | 1.73 | 4.96 |

| No. 23 Huaxin Road, Xiamen | 65.68 | 19.80 | 10.31 | 5.74 | 9.70 | 4.52 | 3.06 | 12.54 |

| No. 24 Huaxin Road, Xiamen | 86.88 | 24.67 | 13.95 | 6.98 | 17.39 | 5.56 | 3.86 | 14.48 |

| No. 25 Huaxin Road, Xiamen | 58.88 | 18. 14 | 7.73 | 6.06 | 8.99 | 4.38 | 2.70 | 10.88 |

| No. 26 Huaxin Road, Xiamen | 66.76 | 24.00 | 11.64 | 6.09 | 12.47 | 2.68 | 1.88 | 8.00 |

| No. 27 Huaxin Road, Xiamen | 63. 12 | 17.99 | 11.41 | 5.63 | 8.58 | 4.46 | 2.69 | 12.35 |

| No. 28 Huaxin Road, Xiamen | 84.64 | 22. 11 | 14.52 | 7.98 | 16.85 | 5. 11 | 3.59 | 14.49 |

| No. 29 Huaxin Road, Xiamen | 80.27 | 22.80 | 12.43 | 6.37 | 15.52 | 5.54 | 3.44 | 14.17 |

| No. 30 Huaxin Road, Xiamen | 60.97 | 15.52 | 7.22 | 3.60 | 17.65 | 4.66 | 2.50 | 9.81 |

| No. 31 Huaxin Road, Xiamen | 56.74 | 19.84 | 5.73 | 6.44 | 11.05 | 2.48 | 2.47 | 8.74 |

| No. 32 Huaxin Road, Xiamen | 86.86 | 26.01 | 14.45 | 6.30 | 16.82 | 5.25 | 3.71 | 14.32 |

| No. 33 Huaxin Road, Xiamen | 81.23 | 23.09 | 12.79 | 7.55 | 13.38 | 6.64 | 3.72 | 14.06 |

| No. 34 Huaxin Road, Xiamen | 57.70 | 9.80 | 10.91 | 5.33 | 15.19 | 4.04 | 1.58 | 10.84 |

| No. 35 Huaxin Road, Xiamen | 82.82 | 22.48 | 13.24 | 6.05 | 17.09 | 5.20 | 3.60 | 15.17 |

| No. 36 Huaxin Road, Xiamen | 79.48 | 27.24 | 10.61 | 5.45 | 14.22 | 5.29 | 2.83 | 13.84 |

| No. 37 Huaxin Road, Xiamen | 54.19 | 19.95 | 7.19 | 7.03 | 7.70 | 4.30 | 2.04 | 5.98 |

| No. 38 Huaxin Road, Xiamen | 58.41 | 21.28 | 5.87 | 4.65 | 11.00 | 4.78 | 2.57 | 8.25 |

| No. 39 Huaxin Road, Xiamen | 81.97 | 21.42 | 14.38 | 7.95 | 13.96 | 5.65 | 3.73 | 14.88 |

| No. 40 Huaxin Road, Xiamen | 80.17 | 21.28 | 12.51 | 6.61 | 15.63 | 5.64 | 3.51 | 14.99 |

| No. 41 Huaxin Road, Xiamen | 57.95 | 20.25 | 6.85 | 6.90 | 10.90 | 3.17 | 2.55 | 7.33 |

| No. 42 Huaxin Road, Xiamen | 49.67 | 18.31 | 5.36 | 6.64 | 7.68 | 2.94 | 2.67 | 6.07 |

| No. 43 Park West Road, Xiamen | 78.28 | 22.09 | 12.43 | 6.06 | 14.76 | 4.47 | 2.94 | 15.53 |

| No. 47 Park West Road, Xiamen | 76.74 | 21.63 | 12.76 | 5.68 | 13.60 | 4.42 | 3.55 | 15. 11 |

| No. 57 Park West Road, Xiamen | 89.48 | 27.38 | 14.48 | 7.86 | 16.72 | 5.31 | 3.83 | 13.89 |

| No. 1 Douxi Road, Xiamen | 54.06 | 8.86 | 10.98 | 4.56 | 12.88 | 4.16 | 1.86 | 10.78 |

| No. 3 Douxi Road, Xiamen | 67.42 | 18.04 | 12.28 | 7.09 | 13.16 | 4.37 | 1.49 | 10.99 |

| No. 4 Nanhua Road, Xiamen | 64.20 | 18.51 | 11.76 | 3.79 | 11.83 | 4.58 | 3.49 | 10.23 |

| No. 7-1 Nanhua Road, Xiamen | 81.53 | 23.10 | 14.56 | 6.55 | 15.06 | 5.15 | 3.18 | 13.94 |

| No. 7-2 Nanhua Road, Xiamen | 80.03 | 23.02 | 13.78 | 7.76 | 13.95 | 5. 11 | 3. 11 | 13.29 |

| No. 12 Nanhua Road, Xiamen | 75.87 | 22.32 | 10.77 | 5.81 | 14.01 | 5.38 | 2.53 | 15.04 |

| No. 15-2 Nanhua Road, Xiamen | 81.58 | 24.13 | 12.41 | 6.73 | 16.67 | 5.55 | 2.70 | 13.40 |

| No. 15-3 Nanhua Road, Xiamen | 54.05 | 19.71 | 5.37 | 6.66 | 7.36 | 4.75 | 1.78 | 8.41 |

| No. 16 Nanhua Road, Xiamen | 73.68 | 20.88 | 9.81 | 6.06 | 13.20 | 5.40 | 2.65 | 15.68 |

| No. 17-1 Nanhua Road, Xiamen | 80.13 | 21.63 | 14.01 | 7.04 | 14.69 | 5.68 | 3.01 | 14.08 |

| No. 17-2 Nanhua Road, Xiamen | 81.77 | 25.53 | 12.81 | 5.61 | 16.21 | 4.73 | 2.60 | 14.27 |

| No. 23 Nanhua Road, Xiamen | 79.17 | 22.29 | 14.40 | 6.94 | 13.82 | 4.82 | 2.92 | 13.97 |

| No. 25 Nanhua Road, Xiamen | 81.21 | 23.15 | 14.01 | 6.31 | 14.66 | 5.20 | 3.19 | 14.69 |

| No. 29 Nanhua Road, Xiamen | 76.32 | 22.97 | 11.79 | 5.52 | 12.95 | 5.60 | 3.13 | 14.36 |

| No. 41 Nanhua Road, Xiamen | 75.67 | 23.06 | 12.36 | 5.59 | 12.92 | 5. 14 | 3.23 | 13.37 |

| No. 8-1 Baihe Road, Xiamen | 74.02 | 20.90 | 10.49 | 6.08 | 13.77 | 5.46 | 2.52 | 14.80 |

| No. 10 Baihe Road, Xiamen | 82.47 | 23.98 | 14. 14 | 5.50 | 16.19 | 4.93 | 3.19 | 14.53 |

| No. 10-1 Baihe Road, Xiamen | 77.98 | 22.18 | 12.36 | 5.81 | 14.61 | 4.73 | 3.68 | 14.61 |

| No. 10-2 Baihe Road, Xiamen | 73.41 | 21.10 | 11.89 | 5.94 | 12.27 | 5.24 | 3.06 | 13.91 |

| No. 10-3 Baihe Road, Xiamen | 80.26 | 21.89 | 11.62 | 7.03 | 16.79 | 5.55 | 3.00 | 14.38 |

| No. 10-4 Baihe Road, Xiamen | 73.61 | 21.39 | 11.38 | 5.85 | 11.35 | 5.28 | 2.67 | 15.70 |

| No. 10-6 Baihe Road, Xiamen | 66.54 | 21.05 | 12.64 | 6.06 | 12.23 | 2.41 | 1.94 | 10.21 |

| No. 1 Qiaocun Street, Zhangzhou | 74.67 | 21.72 | 9.89 | 5.58 | 13.84 | 5.24 | 2.79 | 15.60 |

| No. 2 Qiaocun Street, Zhangzhou | 56.25 | 18.82 | 6.63 | 6.89 | 10.06 | 2.61 | 2.53 | 8.71 |

| No. 3 Qiaocun Street, Zhangzhou | 53.58 | 10.77 | 10.13 | 3.34 | 12.83 | 4.13 | 1.54 | 10.84 |

| No. 4 Qiaocun Street, Zhangzhou | 65.16 | 19.85 | 11.93 | 6.51 | 12.97 | 3.38 | 2.54 | 7.98 |

| No. 5 Qiaocun Street, Zhangzhou | 78.48 | 22.22 | 12.50 | 5.92 | 14.71 | 4.87 | 3.08 | 15.17 |

| No. 6 Qiaocun Street, Zhangzhou | 75.50 | 20.97 | 12.09 | 5.92 | 14.78 | 4.83 | 3.06 | 13.85 |

| No. 7 Qiaocun Street, Zhangzhou | 77.56 | 22.93 | 11.58 | 5.86 | 14.64 | 4.37 | 2.94 | 15.23 |

| No. 8 Qiaocun Street, Zhangzhou | 77.46 | 21.99 | 12.28 | 5.55 | 14.52 | 4.59 | 2.93 | 15.59 |

| No. 9 Qiaocun Street, Zhangzhou | 74.58 | 21.00 | 11.94 | 6. 14 | 11.67 | 5.38 | 3.17 | 15.28 |

| No. 10 Qiaocun Street, Zhangzhou | 57.64 | 19.77 | 7.74 | 6.69 | 11.25 | 4.36 | 1.24 | 6.58 |

| No. 11 Qiaocun Street, Zhangzhou | 63.68 | 15.35 | 10.68 | 6.62 | 12.32 | 5.37 | 2.76 | 10.58 |

| No. 12 Qiaocun Street, Zhangzhou | 58.61 | 21.90 | 9.31 | 6.26 | 7.70 | 4.43 | 2.74 | 6.27 |

| No. 13 Qiaocun Street, Zhangzhou | 90.55 | 27.71 | 14.64 | 7.85 | 17.07 | 6.58 | 3.63 | 13.06 |

| No. 14 Qiaocun Street, Zhangzhou | 73.45 | 21.58 | 10.65 | 6.41 | 14.18 | 4.36 | 2.71 | 13.56 |

| No. 15 Qiaocun Street, Zhangzhou | 55.47 | 19.66 | 4.91 | 6.56 | 12.07 | 3.30 | 2.56 | 6.40 |

| No. 16 Qiaocun Street, Zhangzhou | 72.24 | 20.69 | 10.50 | 5.88 | 13.69 | 4.51 | 2.68 | 14.30 |

| No. 17 Qiaocun Street, Zhangzhou | 73.62 | 21.20 | 10.58 | 5.56 | 14.74 | 4.96 | 2.67 | 13.89 |

| No. 18 Qiaocun Street, Zhangzhou | 74.47 | 21.26 | 12.24 | 6.04 | 12.24 | 4.76 | 3.10 | 14.83 |

| No. 19 Qiaocun Street, Zhangzhou | 69.02 | 20.81 | 10.02 | 3.79 | 14.84 | 4.63 | 2.63 | 12.31 |

| No. 20 Qiaocun Street, Zhangzhou | 54.22 | 17.86 | 9.22 | 6.54 | 8.81 | 4.10 | 2.65 | 5.03 |

| No. 20-1 Qiaocun Street, Zhangzhou | 70.30 | 18.00 | 11.87 | 6.85 | 11.93 | 5.67 | 3.00 | 12.97 |

| No. 21 Qiaocun Street, Zhangzhou | 75.16 | 20.68 | 12.68 | 5.84 | 14.76 | 4.56 | 3.09 | 13.55 |

| No. 22 Qiaocun Street, Zhangzhou | 69.48 | 18.35 | 12.86 | 6. 14 | 13.24 | 5.25 | 2.79 | 10.85 |

| No. 23 Qiaocun Street, Zhangzhou | 73.83 | 22.97 | 10.70 | 6.15 | 11.66 | 5.64 | 2.90 | 13.80 |

| No. 25 Qiaocun Street, Zhangzhou | 81.75 | 25.07 | 11.46 | 7.97 | 13.32 | 5.78 | 3.05 | 15.10 |

| No. 26 Qiaocun Street, Zhangzhou | 60.59 | 19.27 | 10.34 | 3.35 | 9.61 | 4.70 | 2.68 | 10.65 |

| No. 27 Qiaocun Street, Zhangzhou | 61.57 | 18.15 | 11.49 | 5.86 | 13.85 | 4.71 | 1.69 | 5.82 |

| No. 28 Qiaocun Street, Zhangzhou | 65.97 | 19.45 | 11.89 | 5.94 | 12.64 | 3.46 | 2.64 | 9.96 |

| No. 29 Qiaocun Street, Zhangzhou | 58.66 | 13.33 | 10.45 | 4.31 | 14.91 | 4.00 | 1.50 | 10.15 |

| No. 30 Qiaocun Street, Zhangzhou | 74.89 | 21.38 | 10.51 | 5.96 | 14.79 | 4.38 | 2.54 | 15.34 |

| No. 31 Qiaocun Street, Zhangzhou | 55.68 | 17.84 | 8.80 | 6.79 | 8.66 | 4.60 | 1.64 | 7.35 |

| No. 32 Qiaocun Street, Zhangzhou | 65.69 | 19. 12 | 9.81 | 5.57 | 14.25 | 4.37 | 1.63 | 10.95 |

| No. 33 Qiaocun Street, Zhangzhou | 61.29 | 17.17 | 9.82 | 5.46 | 8.76 | 5.53 | 2.44 | 12.12 |

| No. 34 Qiaocun Street, Zhangzhou | 61. 12 | 20.29 | 10. 14 | 4.91 | 6.95 | 4.35 | 1.70 | 12.78 |

| No. 35 Qiaocun Street, Zhangzhou | 84.23 | 24.23 | 14.46 | 6. 14 | 17.56 | 5.34 | 3.01 | 13.48 |

| No. 36 Qiaocun Street, Zhangzhou | 83.92 | 25.43 | 13.28 | 5.86 | 16.08 | 5.51 | 3.26 | 14.51 |

| No. 37 Qiaocun Street, Zhangzhou | 87.37 | 26.43 | 13.57 | 7.17 | 16.05 | 6.18 | 3.80 | 14.18 |

| No. 39 Qiaocun Street, Zhangzhou | 72.15 | 21. 12 | 11.65 | 5.58 | 11.82 | 4.35 | 2.92 | 14.69 |

| No. 40 Qiaocun Street, Zhangzhou | 80.43 | 26.68 | 12.24 | 6.40 | 13.44 | 4.66 | 2.56 | 14.44 |

| No. 41 Qiaocun Street, Zhangzhou | 77.85 | 23.21 | 12.79 | 6. 12 | 12.84 | 4.42 | 3.21 | 15.26 |

| Quanzhou First Row, No. 5 | 72.65 | 22.01 | 10.10 | 6.09 | 11.75 | 4.43 | 2.70 | 15.58 |

| Quanzhou First Row, No. 7 | 59.64 | 18.47 | 8.68 | 4.08 | 12.91 | 3.85 | 2.16 | 9.50 |

| Quanzhou First Row, No. 9 | 88.34 | 27.56 | 13.19 | 7.62 | 17.26 | 6.21 | 3.62 | 12.88 |

| Quanzhou First Row, No. 11 | 70.15 | 21.64 | 11.10 | 5.65 | 12.26 | 4.52 | 3.24 | 11.73 |

| Quanzhou First Row, No. 13 | 56.52 | 11.78 | 11.03 | 3.78 | 14.83 | 2.91 | 2.19 | 9.99 |

| Quanzhou First Row, No. 15 | 86.67 | 26.13 | 15.18 | 7.79 | 16.27 | 5.09 | 3.22 | 12.99 |

| Quanzhou First Row, No. 17 | 64.43 | 17.74 | 11.51 | 5.98 | 12.34 | 3.64 | 2.45 | 10.76 |

| Quanzhou First Row, No. 19 | 55. 11 | 9.31 | 10.50 | 4.23 | 14.05 | 3.61 | 2.30 | 11. 12 |

| Quanzhou First Row, No. 21 | 65.77 | 19.27 | 9.90 | 5.61 | 13.84 | 4.40 | 2.07 | 10.67 |

| Quanzhou First Row, No. 23 | 54. 11 | 19.76 | 7.05 | 7.08 | 6.03 | 4.75 | 1.30 | 8. 14 |

| Quanzhou First Row, No. 25 | 59.05 | 21.90 | 5.88 | 5.78 | 12.21 | 4.81 | 2.62 | 5.84 |

| Quanzhou First Row, No. 27 | 58.00 | 17.86 | 8.63 | 6.64 | 11.28 | 3.56 | 2.79 | 7.24 |

| No. 2, 2nd row, Quanzhou | 74.28 | 22.98 | 12.18 | 6. 11 | 11.60 | 4.84 | 2.67 | 13.89 |

| No. 4, 2nd row, Quanzhou | 74.51 | 22.56 | 11.94 | 5.87 | 12.66 | 4.75 | 3.16 | 13.58 |

| No. 6, 2nd row, Quanzhou | 55.18 | 20.17 | 9.44 | 6.87 | 8.30 | 2.67 | 2.71 | 5.01 |

| No. 8, 2nd row, Quanzhou | 55.42 | 12.13 | 10.31 | 2.92 | 14.38 | 3.74 | 1.93 | 10.00 |

| No. 10, 2nd row, Quanzhou | 55.50 | 19.46 | 7.08 | 6.84 | 6.63 | 4.85 | 2.32 | 8.32 |

| No. 12, 2nd row, Quanzhou | 85.46 | 23.95 | 14.05 | 7.04 | 17.25 | 5.19 | 3.07 | 14.91 |

| No. 14, 2nd row, Quanzhou | 57.79 | 21.74 | 6.84 | 5.61 | 11.30 | 4.64 | 2.74 | 4.94 |

| No. 16, 2nd row, Quanzhou | 60.43 | 18.88 | 10.80 | 4.65 | 6. 12 | 5.42 | 2.51 | 12.05 |

| No. 18, 2nd row, Quanzhou | 74.56 | 23.22 | 10.55 | 6.08 | 12.71 | 4.42 | 2.65 | 14.93 |

| No. 20, 2nd row, Quanzhou | 58.75 | 19.74 | 8.43 | 6.96 | 12.39 | 3. 12 | 2.65 | 5.46 |

| No. 22, 2nd row, Quanzhou | 52.94 | 19.56 | 8.64 | 6.50 | 6.32 | 4.41 | 2.30 | 5.22 |

| No. 24, 2nd row, Quanzhou | 76.55 | 23.09 | 11.88 | 6. 14 | 13.69 | 4.78 | 2.50 | 14.46 |

| No. 26, 2nd row, Quanzhou | 60.39 | 19.04 | 9.81 | 5.32 | 7.81 | 4.55 | 1.33 | 12.54 |

| No. 1, 3rd row, Quanzhou | 52.67 | 18.93 | 5.64 | 7.06 | 6.29 | 2.62 | 2.58 | 9.55 |

| No. 3, 3rd row, Quanzhou | 71.94 | 21.66 | 12.18 | 5.93 | 11.37 | 4.55 | 3.00 | 13.27 |

| No. 5, 3rd row, Quanzhou | 72.27 | 20.87 | 12.04 | 5.39 | 11.58 | 4.94 | 2.76 | 14.69 |

| No. 7, 3rd rowQuanzhou | 57.94 | 11.21 | 10.95 | 5.13 | 14.52 | 3.83 | 1.73 | 10.58 |

| No. 9, 3rd row, Quanzhou | 51.91 | 9.23 | 10.42 | 3.00 | 14.03 | 2.91 | 1.53 | 10.78 |

| No. 12, 3rd row, Quanzhou | 63.80 | 20.57 | 10.84 | 6.02 | 6.76 | 4.98 | 2.62 | 12.02 |

| No. 13, 3rd row, Quanzhou | 57.65 | 17.78 | 6.16 | 6.96 | 10.75 | 4.67 | 2.36 | 8.96 |

| No. 2, 4th row, Quanzhou | 75.75 | 22.50 | 11.63 | 5.70 | 12.74 | 5.13 | 3. 11 | 14.93 |

| No. 4, 4th row, Quanzhou | 90.99 | 25.76 | 15.05 | 8.16 | 16.62 | 6.41 | 3.73 | 15.27 |

| No. 6, 4th row, Quanzhou | 70.49 | 20.64 | 11.95 | 5.53 | 11.75 | 4.69 | 2.94 | 12.99 |

| No. 8, 4th row, Quanzhou | 70.48 | 20.94 | 11.56 | 5.42 | 12.26 | 4.93 | 3. 11 | 12.27 |

| No. 10, 4th row, Quanzhou | 83.73 | 26.38 | 12.28 | 6.63 | 16.04 | 5.43 | 3.19 | 13.78 |

| No. 13, 4th row, Quanzhou | 70.95 | 20.92 | 10.98 | 5.58 | 11.46 | 4.56 | 3.25 | 14.20 |

| No. 14, 4th row, Quanzhou | 68.13 | 19.15 | 10.69 | 5.50 | 16.90 | 4.40 | 1.55 | 9.93 |

| No. 15, 4th row, Quanzhou | 58.20 | 18.68 | 6.75 | 6.15 | 11.34 | 4.54 | 2.45 | 8.30 |

| No. 5, 5th row, Quanzhou | 75.43 | 22.24 | 13.04 | 5.84 | 12.20 | 4.94 | 2.94 | 14.22 |

| No. 7, 5th row, Quanzhou | 80.19 | 21.73 | 13.95 | 6.68 | 14.68 | 4.80 | 3.07 | 15.27 |

| No. 9, 5th row, Quanzhou | 83.89 | 26.34 | 14.34 | 6.50 | 15.58 | 4.91 | 2.92 | 13.30 |

| No. 11, 5th row, Quanzhou | 56.78 | 19.37 | 9.30 | 7.06 | 7.92 | 3.60 | 2.52 | 7.02 |

| No. 13, 5th row, Quanzhou | 80.98 | 23.55 | 13.75 | 6.40 | 14.64 | 5.59 | 3.26 | 13.79 |

| No. 15, 5th row, Quanzhou | 80.31 | 21.53 | 13.51 | 6.56 | 16.57 | 5.35 | 3.13 | 13.65 |

| No. 19, 5th row, Quanzhou | 84.07 | 26.25 | 14.31 | 6.35 | 13.38 | 5.52 | 3.23 | 15.04 |

| No. 21, 5th row, Quanzhou | 87.35 | 26.19 | 14.50 | 6.28 | 16.65 | 5.06 | 3.07 | 15.59 |

| Putian No. 1 | 49.57 | 18.53 | 4.96 | 7.09 | 7.52 | 3.62 | 2.49 | 5.36 |

| Putian No. 2 | 86.32 | 22.33 | 14.93 | 7.76 | 15.59 | 6.46 | 3.69 | 15.56 |

| Putian No. 3 | 85.33 | 23.09 | 15.19 | 7.31 | 16.64 | 6.56 | 3.20 | 13.35 |

| Putian No. 4 | 52.35 | 8.85 | 10.63 | 4.44 | 14.44 | 2.22 | 1.84 | 9.93 |

| Putian No. 5 | 86.90 | 26.32 | 14.46 | 6.98 | 16.79 | 5.29 | 2.98 | 14.08 |

| Putian No. 6 | 80.51 | 20.97 | 12.44 | 7.36 | 16.85 | 5.06 | 3.70 | 14.13 |

| Putian No. 7 | 56.17 | 21.81 | 6.13 | 6.26 | 5.77 | 4.44 | 2.71 | 9.05 |

| Putian No. 8 | 83.13 | 26.17 | 14.44 | 5.79 | 14.34 | 5.27 | 3.13 | 13.98 |

| Putian No. 12 | 74.98 | 23.01 | 11.54 | 5.67 | 11.41 | 4.52 | 3.26 | 15.58 |

| Putian No. 13 | 80.60 | 21.15 | 12.64 | 7.70 | 15.13 | 5.19 | 3.71 | 15.08 |

| Putian No. 15 | 57.27 | 18.53 | 5.88 | 6.55 | 10.51 | 3.88 | 2.68 | 9.23 |

| Putian No. 16 | 75.50 | 23.15 | 12.51 | 5.64 | 14.35 | 4.88 | 2.85 | 12.12 |

| Putian No. 17 | 75.78 | 22.60 | 12.68 | 5.56 | 13.86 | 4.38 | 3.18 | 13.52 |

| Putian No. 18 | 82.78 | 26.39 | 12.50 | 5.95 | 15.10 | 5.70 | 3.06 | 14.08 |

| Putian No. 19 | 73.65 | 22.17 | 12.73 | 5.79 | 12.26 | 4.42 | 2.90 | 13.38 |

| Putian No. 20 | 74.60 | 21.92 | 12.72 | 5.63 | 12.48 | 4.70 | 3.00 | 14.14 |

| Putian No. 21 | 72.67 | 22.53 | 9.93 | 5.72 | 12.19 | 4.73 | 3.06 | 14.52 |

| Putian No. 22 | 58.84 | 15.67 | 11. 11 | 2.71 | 13.23 | 3.44 | 1.85 | 10.83 |

| Putian No. 23 | 80.27 | 22.60 | 14.50 | 5.53 | 14.16 | 5. 12 | 2.96 | 15.40 |

| Putian No. 25 | 80.24 | 22.80 | 14.56 | 7.03 | 14.09 | 5.52 | 2.83 | 13.40 |

| Putian No. 26 | 85.43 | 24.00 | 14.51 | 6.65 | 16.68 | 5.50 | 2.53 | 15.56 |

| Putian No. 27 | 56.56 | 18.33 | 6.91 | 6.57 | 8.37 | 4.88 | 2.35 | 9.15 |

| Putian No. 28 | 56.00 | 21.42 | 5.25 | 6. 11 | 7.46 | 4.45 | 2.70 | 8.60 |

| Putian No. 29 | 83.50 | 23.72 | 15.15 | 6.91 | 16.44 | 6.08 | 3.31 | 11.87 |

| Putian No. 30 | 72.20 | 21.03 | 12. 14 | 6.09 | 12.59 | 4.44 | 2.62 | 13.29 |

| Putian No. 31 | 72.96 | 21.18 | 11.80 | 5.44 | 12.24 | 4.44 | 2.64 | 15.23 |

| Putian No. 32 | 59.52 | 19.04 | 7.13 | 4.88 | 10.57 | 4.34 | 2.37 | 11.19 |

| Putian No. 33 | 74.96 | 21.36 | 11.83 | 5.98 | 12.69 | 4.48 | 3. 12 | 15.50 |

| Putian No. 35 | 54.99 | 18.48 | 9.19 | 7.20 | 7.86 | 2.29 | 2.56 | 7.40 |

| Putian No. 41 | 75.32 | 22.64 | 11.86 | 5.89 | 12.25 | 4.93 | 2.93 | 14.82 |

| Putian No. 42 | 80.00 | 23.16 | 13.78 | 6.94 | 13.63 | 5.34 | 3.81 | 13.34 |

| Putian No. 46 | 72.44 | 21.19 | 10.70 | 5.54 | 12.48 | 4.77 | 2.62 | 15.14 |

| Putian No. 56 | 58.98 | 14.21 | 10.42 | 2.96 | 14.54 | 3.66 | 2.03 | 11.16 |

| Fuzhou No. 1 | 66.56 | 20.26 | 12.04 | 5.82 | 11.88 | 3.16 | 2.49 | 10.91 |

| Fuzhou No. 2 | 58.83 | 19.96 | 9.22 | 6.73 | 8.71 | 4.82 | 1.42 | 7.97 |

| Fuzhou No. 3 | 67.91 | 19.48 | 11.13 | 5.50 | 14.45 | 4.76 | 1.69 | 10.91 |

| Fuzhou No. 4 | 55.66 | 21.69 | 5.60 | 6.28 | 7.18 | 4.48 | 2.56 | 7.87 |

| Fuzhou No. 5 | 61. 14 | 18.75 | 9.90 | 3.13 | 9.73 | 5.47 | 2.65 | 11.50 |

| Fuzhou No. 6 | 61.93 | 17.85 | 10.34 | 4.32 | 9.44 | 4.86 | 2.37 | 12.75 |

| Fuzhou No. 7 | 65.88 | 17.83 | 13.31 | 6.30 | 11.79 | 3.40 | 2.58 | 10.68 |

| Fuzhou No. 8 | 61.61 | 17.84 | 9.92 | 3.98 | 10.26 | 5.32 | 2.50 | 11.79 |

| Fuzhou No. 9 | 67.05 | 22.59 | 10. 14 | 4. 11 | 8.94 | 4.43 | 1.53 | 15.30 |

| Fuzhou No. 10 | 61.82 | 17.93 | 10.58 | 3.52 | 9.21 | 5.03 | 2.75 | 12.80 |

| Fuzhou No. 11 | 64.77 | 18.59 | 10.60 | 5.81 | 14. 12 | 4.32 | 1.27 | 10.04 |

| Fuzhou No. 12 | 55.53 | 17.74 | 4.94 | 6.73 | 10.34 | 4.17 | 2.79 | 8.81 |

| Fuzhou No. 13 | 54.13 | 9.37 | 11.15 | 3.88 | 14.04 | 3.33 | 1.88 | 10.48 |

| Fuzhou No. 14 | 50.92 | 19.00 | 5. 11 | 7.17 | 6.29 | 4.35 | 2.27 | 6.73 |

| Fuzhou No. 15 | 66.80 | 20.26 | 11.93 | 5.57 | 12.43 | 3.43 | 2.55 | 10.62 |

| Fuzhou No. 16 | 52.94 | 20.80 | 4.94 | 5.89 | 6.47 | 4.56 | 2.77 | 7.52 |

| Fuzhou No. 17 | 58.18 | 19.77 | 8.63 | 4.91 | 8.62 | 4.00 | 2.04 | 10.21 |

| Fuzhou No. 18 | 58.69 | 19.90 | 6.33 | 6.27 | 11.64 | 4.35 | 2.09 | 8. 11 |

| Fuzhou No. 19 | 71.01 | 20.85 | 11.19 | 5.99 | 11.81 | 4.82 | 2.74 | 13.61 |

| Fuzhou No. 20 | 70.62 | 21.71 | 11.05 | 6.17 | 11.78 | 4.89 | 2.57 | 12.45 |

| Fuzhou No. 21 | 50.84 | 18.01 | 7.73 | 6.51 | 7.95 | 2.40 | 2.56 | 5.68 |

| Fuzhou No. 22 | 53.65 | 18.44 | 8.80 | 7. 14 | 6.06 | 3.62 | 2.76 | 6.83 |

| Fuzhou No. 23 | 66.36 | 17.96 | 10.85 | 5.50 | 15.06 | 4.44 | 1.99 | 10.55 |

| Fuzhou No. 24 | 60.55 | 15.39 | 10.32 | 5.21 | 10.93 | 4.74 | 1.61 | 12.36 |

| Fuzhou No. 25 | 70.95 | 21.87 | 11.19 | 6.09 | 12.13 | 4.96 | 2.74 | 11.98 |

| Fuzhou No. 26 | 85.93 | 26.19 | 14.47 | 8.28 | 13.17 | 5.54 | 2.95 | 15.33 |

| Fuzhou No. 27 | 61.87 | 15.65 | 10.41 | 4.01 | 12.18 | 5.41 | 2.80 | 11.41 |

| Fuzhou No. 28 | 69.72 | 19. 11 | 10.56 | 5.90 | 17.23 | 4.66 | 1.29 | 10.97 |

| Fuzhou No. 29 | 70.91 | 21.10 | 11.21 | 5.56 | 13.93 | 4.80 | 2.67 | 11.65 |

| Fuzhou No. 30 | 80.50 | 21.93 | 14.30 | 7.49 | 14.36 | 5.49 | 3.20 | 13.73 |

| Fuzhou No. 31 | 65.81 | 18.88 | 12.73 | 5.78 | 13.27 | 2.17 | 2.45 | 10.52 |

| Fuzhou No. 32 | 65.59 | 19.24 | 10.08 | 5.56 | 13.99 | 4.31 | 2.01 | 10.40 |

| Fuzhou No. 33 | 62.52 | 17.56 | 10.64 | 5.33 | 9.27 | 5.02 | 2.65 | 12.04 |

| Fuzhou No. 34 | 63.36 | 19.50 | 10.58 | 5.51 | 10.04 | 4.52 | 1.78 | 11.43 |

| Fuzhou No. 35 | 59.41 | 16.79 | 10.15 | 3.78 | 13.67 | 3.03 | 1.40 | 10.59 |

| Fuzhou No. 36 | 55.08 | 18.70 | 9.32 | 6.66 | 8.62 | 4.63 | 2.29 | 4.86 |

| Fuzhou No. 37 | 64.30 | 18.99 | 11.58 | 6.13 | 12.26 | 2.15 | 2.71 | 10.47 |

| Fuzhou No. 38 | 54.79 | 20.13 | 6.47 | 7.13 | 6.35 | 4.55 | 1.21 | 8.95 |

| Fuzhou No. 39 | 68.81 | 21.19 | 14.66 | 5.66 | 11.65 | 3.35 | 1.54 | 10.77 |

| Fuzhou No. 40 | 71.07 | 21.32 | 11.61 | 5.51 | 13.30 | 4.81 | 2.49 | 12.02 |

| Fuzhou No. 41 | 74.98 | 21.81 | 12.48 | 5.75 | 12.64 | 4.53 | 3.18 | 14.59 |

| Fuzhou No. 42 | 75.92 | 23.18 | 12.81 | 6.09 | 12.79 | 4.77 | 2.59 | 13.68 |

| Fuzhou No. 43 | 81.08 | 22.88 | 12.09 | 6.00 | 16.69 | 4.55 | 3.21 | 15.66 |

| Fuzhou No. 45 | 72.40 | 22.20 | 10.17 | 5.46 | 14.76 | 4.48 | 3. 11 | 12.21 |

| Fuzhou No. 46 | 72.53 | 22.80 | 11.79 | 5.67 | 12.04 | 4.67 | 2.99 | 12.57 |

| Fuzhou No. 47 | 84.25 | 25.44 | 14.45 | 6.34 | 14.29 | 5.06 | 3.17 | 15.50 |

| Fuzhou No. 48 | 63.21 | 19.67 | 11.93 | 6.87 | 11.97 | 4.01 | 2.74 | 6.01 |

| Fuzhou No. 49 | 70.98 | 22.13 | 9.83 | 5.46 | 13.71 | 4.90 | 2.81 | 12.12 |

| Fuzhou No. 50 | 54.57 | 20.72 | 6.98 | 6.13 | 7.02 | 4.80 | 2.61 | 6.32 |

| Fuzhou No. 51 | 49.91 | 18.74 | 4.86 | 6.55 | 8.80 | 2.17 | 2.73 | 6.05 |

| Fuzhou No. 52 | 73.63 | 22.65 | 10.93 | 5.81 | 13.83 | 4.76 | 2.75 | 12.89 |

| Fuzhou No. 53 | 64.24 | 16.62 | 9.79 | 6.83 | 12.87 | 5.32 | 2.79 | 10.02 |

| Fuzhou No. 54 | 57.61 | 19.92 | 8.40 | 3.89 | 9.54 | 4.13 | 2.77 | 8.96 |

| Fuzhou No. 55 | 59.16 | 15.18 | 11.04 | 3.07 | 13.88 | 3.19 | 2.35 | 10.45 |

| Fuzhou No. 56 | 76.03 | 22. 11 | 12.36 | 5.93 | 14.07 | 4.74 | 2.57 | 14.25 |

| Fuzhou No. 57 | 71.57 | 20.81 | 10.81 | 5.88 | 12.10 | 4.82 | 2.83 | 14.31 |

| Fuzhou No. 58 | 65.54 | 15.58 | 10.79 | 5.16 | 14.88 | 4.55 | 2.78 | 11.80 |

| Fuzhou No. 59 | 71.05 | 21.84 | 9.81 | 6.06 | 12.78 | 4.81 | 2.91 | 12.84 |

| Fuzhou No. 60 | 55.90 | 22.48 | 7.77 | 5.84 | 7.10 | 4.31 | 2.56 | 5.83 |

| Fuzhou No. 62 | 75.95 | 22.32 | 11.09 | 5.66 | 14.33 | 4.52 | 2.73 | 15.31 |

| Fuzhou No. 64 | 82.60 | 24.68 | 13.83 | 6.80 | 16.01 | 6.19 | 3.18 | 11.91 |

| Fuzhou No. 66 | 80.21 | 20.78 | 13.07 | 6.34 | 16.75 | 4.91 | 3.04 | 15.33 |

| Fuzhou No. 67 | 70.47 | 21.32 | 10.50 | 5.82 | 12.16 | 4.75 | 2.52 | 13.40 |

| Fuzhou No. 70 | 54.06 | 20.09 | 6.70 | 5.83 | 9.29 | 5.04 | 1.61 | 5.48 |

| Fuzhou No. 71 | 74.36 | 21.55 | 10.87 | 6.76 | 12.58 | 4.85 | 2.66 | 15.09 |

| Fuzhou No. 72 | 72.25 | 21.31 | 9.89 | 6.91 | 11.93 | 4.78 | 2.66 | 14.76 |

References

- Zhang, S. The preservation of 20th-century architectural heritage in China: Evolution and prospects. Built Herit. 2018, 2, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Luo, Z.; Jiang, R.; Zhao, M. Heritage space, multiple temporalities, and the reproduction of Guangzhou Overseas Chinese Village. Emot. Space Soc. 2023, 48, 100958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, M.; Li, Y. The Spatial Patterns and Architectural Form Characteristics of Chinese Traditional Villages: A Case Study of Guanzhong, Shaanxi Province. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itma, M.; Salama, W. Building Regulations Assessment in Terms of Affordability Values. Towards Sustainable Housing Supplying in Palestine. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plann. 2023, 18, 793–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, K. Landscape Design Symbols of the 20th Century; Publishing House of Electronics Industry: Beijing, China, 2012. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Figueres, M.T.P. DOCOMOMO. Arquitectura moderna y patrimonio. Loggia Arquit. Restaur. 2018, 31, 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumann, C.; Gfeller, A.É. Cultural landscapes and the UNESCO World Heritage List: Perpetuating European dominance. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2022, 28, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mykhaylyshyn, O.; Shevchenko, L.; Mahey, A. Digital technologies as an innovative tool for the preservation of the palace complexes of Podillya in the late 19th–Early 20th century. In Proceedings of the AIP Conference Proceedings, Kharkiv, Ukraine, 20–21 May 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Announcement of the Seventh Batch of Recommended 20th-Century Architectural Heritage Projects in China. Available online: http://www.ncha.gov.cn/art/2023/2/21/art_723_179862.html (accessed on 25 June 2025). (In Chinese)

- Chen, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, P. Value Perception and Willingness to Pay for Architectural Heritage Conservation: Evidence from Kumbum Monastery in China. Buildings 2025, 15, 1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J. Construction of the Evaluation System for the Protection Value of 20th-century Architectural Heritage in China. Contemp. Archit. 2020, 20, 134–137. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Caravanos, E.M. Cultural Landscape Preservation in United States National Parks: Analysis and Recommendations for US Cultural Landscapes Eligible for Nomination to UNESCO. Master’s Thesis, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zerner, H. Aloïs Riegel: Art, value and historicism. Daedalus 1976, 105, 177–188. [Google Scholar]

- Gold, J.R. Creating the Charter of Athens: CIAM and the functional city, 1933–1943. Town Plan. Rev. 1998, 69, 225–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokilehto, J. The context of the Venice Charter (1964). Conserv. Manag. Archaeol. Sites 1998, 2, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodwell, D. The UNESCO world heritage convention, 1972–2012: Reflections and directions. Hist. Environ. Policy Pract. 2012, 3, 64–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, M. A Future for Our Past: Reviewing 40 years of European Architectural Heritage Year. Hist. Environ. Policy Pract. 2017, 8, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterton, E.; Smith, L.; Campbell, G. The utility of discourse analysis to heritage studies: The Burra Charter and social inclusion. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2006, 12, 339–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, R.; Li, H. A study on legislation for protection of cultural relics in china: Origin, content and model. Chin. Stud. 2019, 8, 132–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D. Dialogue history with architecture 2021 European architectural heritage intervention award. Art Des. 2021, 17, 138–143. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, S.; Choi, B.; Kang, C. Establishing and applying a value evaluation model for traditional Pit Kiln villages. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2022, 21, 1262–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lü, Z. The value of cultural relic buildings and their protection. Sci. Decis. Mak. 1997, 38–41. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, G.; Fang, Q.; Lei, X. An exploration of architectural heritage assessment. New Archit. 1998, 26–28. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Maus, A.K. Safeguarding China’s Cultural History: Proposed Amendments to the 2002 Law on the Protection of Cultural Relics. Pac. Rim Law Policy J. 2009, 18, 405–432. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S. The value orientation principle for protecting historical and cultural blocks—Also discussing the pilot project for the protection of Nanchizi. Beijing Plann. Rev. 2004, 2, 105–108. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Andrade, I. Historic environment: Preservation principles. In Proceedings of the 5th International Seminar on Urban Conservation, Recife, Brazil, 19–21 November 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, S. Translation and interpretation of conceptual terms in cultural heritage science. China Terminol. 2008, 54–59. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Mason, R. Be interested and beware: Joining economic valuation and heritage conservation. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2008, 14, 303–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J. A re-understanding of the value system of architectural heritage. China Anc. City 2018, 71–76. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Nowakowska, A.; Adamus, J. How valuable is architectural heritage? Evaluating a monument’s perceived value with the use of spatial order concept. Sage Open 2022, 12, 2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wang, J.; Shi, K. Research on the investigation and value evaluation of historic building resources in Xi’an city. Buildings 2023, 13, 2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Tao, J.; Xu, J.; Zhang, Y. Research on an evaluation index system and evaluation method of green and low-carbon expressway construction. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0283559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, X.; Liu, X.; Ye, W.; Chen, M. Construction of a value evaluation system for fujian tubao architectural heritage based on grounded theory and the analytic hierarchy process. Buildings 2025, 15, 2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, K.; Zhang, Y.; Han, W. Architectural heritage preservation for rural revitalization: Typical case of traditional village Retrofitting in China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, J.Y. Cosmologies of Credit: Transnational Mobility and the Politics of Destination in China; Duke University Press: Kunshan, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, P. Guangzhou overseas Chinese new village. Archit. J. 1957, 17–37. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Yuan, Y. Management-oriented conservation planning for historical and cultural reserves: The case of overseas Chinese new village in Guangzhou. Planners 2007, 23, 39–41. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Tian, Y.; Yuan, Y. Historic quarters soft revitalization base on “Mixed uses”. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2010, 26, 57–60. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Gao, Y.; Pitts, A. Rethinking China’s rural revitalization: The development of a sense of community scale for Chinese traditional village. Land 2023, 12, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.C. The redevelopment of China’s construction land: Practising land property rights in cities through renewals. China Q. 2015, 224, 865–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. Research on the Evolution and Driving Forces of Urban Form in the Overseas Chinese New Village Area of Guangzhou city. Master’s Thesis, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China, 2012. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Tian, Y.; Yuan, Y. A study on localized British garden suburban residences from the perspective of house property rights change: A case study of overseas Chinese new village in Guangzhou. Architect 2012, 15–22. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. Research on the Construction Process of Urban and Rural Housing and the Housing Security System in Guangdong Province. Master’s Thesis, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sang, X.; Huang, C.-H.; Chen, Z.; Wei, S. The spatial integration method and sustainable development strategy of settlement landscapes for the hometown of overseas Chinese in southern Fujian. In Proceedings of the Education and Awareness of Sustainability: Proceedings of the 3rd Eurasian Conference on Educational Innovation 2020 (ECEI 2020), Hanoi, Vietnam, 5–7 February 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, L.; Puntien, P.; Inkuer, A.; Mayusoh, C. Research on the cultural value of traditional overseas Chinese villages in Lingnan. Procedia Multidiscip. Res. 2024, 2, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Yang, Y. Research on the architectural form of detached house in Fuzhou overseas Chinese new village, China. In Proceedings of the 2024 10th International Conference on Architectural, Civil and Hydraulic Engineering (ICACHE 2024), Shenyang, China, 25–27 October 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. Research on the Construction and Development of Overseas Chinese New Village in Guangzhou. Master’s Thesis, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China, 2012. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Z.; Feng, H. Research on the post-use evaluation of modern historical districts under the background of urban micro-renewal: A case study of Guangzhou overseas Chinese new village. Anhui Archit. 2022, 29, 18–20. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z. An analysis of social concept in Guangdong’s overseas Chinese hometowns during modern times—A case study of Toisan overseas Chinese hometowns. Relig. Philos. Art. 2025, 36, 236–262. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, P.A.; Maslesa, E. Value based building renovation–A tool for decision-making and evaluation. Build. Environ. 2015, 92, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, J.; Sujood; Mishra, S.; Yasmeen, N. Archaeotourism Unveiled: A Systematic Literature Review and Chronicles of Built Heritage Conservation. Conserv. Manag. Archaeol. Sites 2024, 26, 113–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plesovskaya, E.; Ivanov, S. An empirical analysis of KDE-based generative models on small datasets. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2021, 193, 442–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura, L.; Ortiz, R.; Becerra, J.; Ortiz, P. Integrating Fuzzy Cognitive Maps and the Delphi Method in the Conservation of Transhumance Heritage: The Case of Andorra. Heritage 2024, 7, 2730–2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamidehkordi, E.; Karimi, V.; Hallaj, Z.; Karimi, M.; Naderi, L. Adaptable leadership for arid/semi-arid wetlands conservation under climate change: Using analytical hierarchy process (AHP) approach. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 351, 119860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, L.; Cao, Y. GIS-based viewshed analysis on the conservation planning of historic towns: The case study of Xinchang, Shanghai. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 2021, 46, 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thunø, M.; Pieke, F.N. Institutionalizing recent rural emigration from China to Europe: New transnational villages in Fujian. Int. Migr. Rev. 2005, 39, 485–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, R.G. China’s vernacular architectural heritage and historic preservation. Built Herit. 2024, 8, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H. The content and theoretical significance of the ‘Principles for the Conservation of Heritage Sites in China’. In Proceedings of the Conservation of Ancient Sites on the Silk Road: Proceedings of the Second International Conference on the Conservation of Grotto Sites, Dunhuang, China, 28 June–3 July 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, M.; Chen, Y.-F.; Zhai, Z.; Du, J. Investigating the critical issues in the conservation of heritage building: The case of China. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 51, 104319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.; Jing, Y.; Huang, H.; Shi, G.; Zhang, X. Developing a fuzzy analytic hierarchical process model for building energy conservation assessment. Renew. Energy 2010, 35, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chee-Beng, T. Reterritorialization of a Balinese Chinese Community in Quanzhou, Fujian. Mod. Asian Stud. 2010, 44, 547–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poston, D.L.; Zhang, H. The overseas Chinese communities in southeast Asia and the pacific. In Mental Health in China and the Chinese Diaspora: Historical and Cultural Perspectives; Minas, H., Ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 141–159. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D. How visitors perceive heritage value—A quantitative study on visitors’ perceived value and satisfaction of architectural heritage through SEM. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Liu, G.; Zhou, J.; Wang, J. Identifying the critical stakeholders for the sustainable development of architectural heritage of tourism: From the perspective of China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopuz, A.D.; Bal, A. The conservation of modern architectural heritage buildings in Turkey: İstanbul Hilton and İstanbul Çınar Hotel as a case study. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2023, 14, 101918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoormans, L.; Pereira Roders, A. Methods in assessing the values of architecture in residential neighbourhoods. Int. J. Build. Pathol. Adapt. 2021, 39, 490–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borri, A.; Corradi, M. Architectural heritage: A discussion on conservation and safety. Heritage 2019, 2, 631–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clementi, F.; Formisano, A.; Milani, G.; Ubertini, F. Structural health monitoring of architectural heritage: From the past to the future advances. Int. J. Archit. Heritage 2021, 15, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Ahmad, Y.; Mohidin, H.H.B. The development of the concept of architectural heritage conservation and its inspiration. Built Herit. 2023, 7, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Li, J. Process-led value elicitation within built heritage management: A systematic literature review between 2010 and 2020. J. Archit. Conserv. 2021, 27, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Response to Proposal 20243092 from the 2nd Session of the 13th Provincial CPPCC. Available online: https://zjt.fj.gov.cn/xxgk/rdjyhzxtabl/zxtablqk/202407/t20240715_6483305.htm (accessed on 25 June 2025). (In Chinese)

- Licciardi, G.; Amirtahmasebi, R. The Economics of Uniqueness: Investing in Historic City Cores and Cultural Heritage Assets for Sustainable Development; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Quanzhou Regulations on the Protection of Overseas Chinese Historical Remains. Available online: https://www.quanzhou.gov.cn/zfb/xxgk/ztxxgk/ggwhty/zcfg/202410/t20241010_3089233.htm (accessed on 25 June 2025). (In Chinese)

- Tang, L.; Tang, J.; Ding, P. Establishment of architectural heritage evaluation indicator system based on cluster analysis in the era of big data. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2022, 2022, 9211435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.; Carneiro, M.J. The influence of interpretation on learning about architectural heritage and on the perception of cultural significance. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2021, 19, 230–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scholar | Year | Core Content | Research Method | Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhu Pu [36] | 1957 | This study elaborates on the construction philosophy and implementation specifics of Overseas Chinese New Village. | Literature analysis method | This study is limited by the integration of the spatial characteristics and theoretical research of the Overseas Chinese New Village. It lacks practice-oriented analysis, systematic synthesis, and fails to establish a comprehensive overall evaluation framework. |

| Wang Min [41] | 2012 | This study systematically analyzes the spatiotemporal evolution of urban morphology and its driving mechanisms by examining transformations in urban form, socioeconomic dynamics, and socio-spatial structures across distinct chronological phases, encompassing both the target area and its adjacent urban contexts. | Literature analysis method | |

| Wang Min [42] | 2012 | The discussion on the various renovation methods of Overseas Chinese Village by different owners due to multiple changes in property rights reflects the materialization trend of humanistic landscapes and presents unique regional characteristics. | Literature analysis method | |

| Chen Yufan [43] | 2018 | From a policy perspective, this paper explores the construction and development of Overseas Chinese Village and analyzes its planning characteristics as a high-quality residential area for returned overseas Chinese in combination with the specific historical background. | Literature research method Observation method Comparative analysis method | |

| Sang Xiaole [44] | 2020 | Axial analysis and proxy calculation were conducted on the current situation of overseas Chinese settlements and the external space after integration and improvement, verifying the research hypothesis that the demolition of abandoned buildings in hollow villages is an effective integration method for protecting the cultural characteristics of the region. Further, a sustainable development strategy was proposed. | space syntax | |

| L Lihong [45] | 2024 | A comprehensive analysis of the cultural value of traditional villages of overseas Chinese in Lingnan is conducted, and their cultural manifestations in terms of architecture, folk customs, beliefs, etc., are deeply explored, with the expectation of revealing the potential cultural resources of these villages in the context of the integration of culture and tourism. | Literature research method Field investigation | |

| Chen Wenchao, [46] | 2025 | The architectural form of the single-family residences of returned overseas Chinese in Fuzhou, China, was studied through planning layout and architectural combination, including the floor plan layout, appearance characteristics, and detailed decoration. | Literature research method Field investigation | |

| Chen Jianyi [47] | 2012 | The construction process and development history of Guangzhou’s Overseas Chinese Village should be reviewed and summarized. | Literature research method | The existing research is geographically confined to Guangzhou, with its content lacking comprehensiveness and diversity, coupled with an absence of follow-up development studies. Consequently, it fails to thoroughly and comprehensively unveil the holistic landscape and underlying value of Overseas Chinese Village. |

| Luo Zizhe [48] | 2019 | From the perspective of users, the research method of post-use evaluation was employed to study the residents’ evaluations after the micro-renovation of Huaqiao New Village was completed. Analyze and summarize the experiences and deficiencies of micro-updates, and put forward the next update strategies and suggestions. | Literature analysis method Post-use Evaluation (POE) | |

| Wang Min [2] | 2023 | The daily experiences of the long-term residents in the urban heritage revitalization process of Guangzhou Overseas Chinese Village (GOCV), as the first overseas Chinese village in China, were investigated. | Literature research method | |

| Zhu Qi [49] | 2025 | Taking Taishan Overseas Chinese Hometown as an example, this paper analyzes the ideological concepts of the modern overseas Chinese hometown society in Guangdong. | Literature research method |

| Scholar | Value Categories |

|---|---|

| Hao Zhigang | Ontological value, spatial value |

| Xu Jinliang | Intrinsic value, extrinsic value |

| Gong Liquan | Ontological value, derived value |

| Li Zhen | Use value, non-use value |

| Xu Lingyu | Intrinsic value, instrumental value, economic value |

| Wang Changsong | Core value, reuse value |

| Screening Process | Element Stratum | Factor Stratum |

|---|---|---|

| First-round Screening Factors | Historical value | Historical uses of buildings, historical context, degree of historical correlation, the impact on the local historical development, historical figures and events, remnants of historical environmental elements |

| Artistic value | Architectural authenticity, regional characteristics of architecture, overall layout of architecture, architectural detailing and ornamentation, architectural style and form, integrity of architecture, color and material of architecture | |

| Scientific value | Site selection for buildings, building materials, rationality of building functions, building structure, reference and learning for contemporary times, building techniques, spatial layout of buildings | |

| Cultural value | Reflection of local cultural standards, religious worship, cultural propaganda and education, national belief, spiritual symbolism, the value of intangible cultural heritage, cultural inheritance | |

| Social value | Social belonging, the rationality of current usage, social emotional attachment, connection to people’s livelihoods | |

| Environmental value | Location and transport accessibility, heritage’s immediate environment, harmonization with the surrounding environment, the surrounding natural environment | |

| Functional Utility Value | Structural safety of the building, completeness of supporting facilities, superiority of geographical location | |

| Second-round Screening | Historical value | Historical uses of buildings, historical context, degree of historical correlation, the impact on the local historical development, historical figures and events |

| Artistic value | Architectural authenticity, regional characteristics of architecture, overall layout of architecture, architectural detailing and ornamentation, architectural style and form | |

| Scientific value | Site selection for buildings, building materials, building structure, reference and learning for contemporary times, building techniques, spatial layout of buildings | |

| Cultural value | Reflection of local cultural standards, cultural propaganda and education, national belief, spiritual symbolism, the value of intangible cultural heritage, cultural inheritance | |

| Social value | The rationality of current usage, social emotional attachment, connection to people’s livelihoods | |

| Environmental value | Heritage’s immediate environment, location and transport accessibility, harmonization with the surrounding environment | |

| Functional Utility Value | Structural safety of the building, completeness of supporting facilities, superiority of geographical location | |

| Third-round Screening Factors (Finalized Core Factors) | Historical value | Historical context, historical figures and events, degree of period representation |

| Artistic value | Architectural style and form, architectural detailing and ornamentation, overall architectural layout, regional architectural characteristics, architectural authenticity | |

| Scientific value | Spatial layout of buildings, site selection for buildings, building materials | |

| Cultural value | Spiritual symbolism, cultural propaganda and education, reflection of local cultural standards | |

| Social value | The rationality of current usage, connection to people’s livelihoods, societal emotional attachment | |

| Environmental value | Heritage’s immediate environment, location and transport accessibility, harmonization with the surrounding environment | |

| Functional Utility Value | Structural safety of the building, completeness of supporting facilities, superiority of geographical location |

| Objective Level | Indicator Level | Element Stratum | Factor Stratum |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heritage Value of Fujian Overseas Chinese Village A | Ontological value B1 | Historical value C1 | Historical context D1 Historical figures and events D2 Degree of period representation D3 |

| Artistic value C2 | Architectural style and form D4 Architectural detailing and ornamentation D5 Overall architectural layout D6 Regional architectural characteristics D7 Architectural authenticity D8 | ||

| Scientific value C3 | Architectural spatial layout D9 Building materials D10 Building site selection D11 | ||

| Extrinsic value B2 | Cultural value C4 | Spiritual symbolism D12 Cultural propaganda and education D13 Reflection of local cultural standards D14 | |

| Social value C5 | Current usage rationality D15 Connection to people’s livelihoods D16 Societal emotional attachment D17 | ||

| Environmental value C6 | Heritage’s immediate environment D18 Location and transport accessibility D19 Harmonization with the surrounding environment D20 | ||

| Functional Value B3 | Functional Utility Value C7 | Structural safety of the building D21 Completeness of supporting facilities D22 Superiority of geographical location D23 |

| Objective Level | Indicator Level | Element Stratum | Factor Stratum |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heritage Value of Fujian Overseas Chinese Village A | Ontological value B1 (0.5389) | Historical value C1 (0.2904) | Historical context D1 (0.1843) Historical figures and events D2 (0.0834) Degree of period representation D3 (0.0227) |

| Artistic value C2 (0.1602) | Architectural style and form D4 (0.0449) Architectural detailing and ornamentation D5 (0.0087) Overall architectural layout D6 (0.0153) Regional architectural characteristics D7 (0.0681) Architectural authenticity D8 (0.0233) | ||

| Scientific value C3 (0.0883) | Architectural spatial layout D9 (0.0294) Building materials D10 (0.0123) Building site selection D11 (0.0466) | ||

| Extrinsic value B2 (0.2973) | Cultural value C4 (0.1852) | Spiritual symbolism D12 (0.1180) Cultural propaganda and education D13 (0.0194) Reflection of local cultural standards D14 (0.0478) | |

| Social value C5 (0.0713) | Current usage rationality D15 (0.0137) Connection to people’s livelihoods D16 (0.0076) Societal emotional attachment D17 (0.0499) | ||

| Environmental value C6 (0.0408) | Heritage’s immediate environment D18 (0.0255) Location and transport accessibility D19 (0.0097) Harmonization with the surrounding environment D20 (0.0056) | ||

| Functional Value B3 (0.1638) | Functional Utility Value C7 (0.1638) | Structural safety of the building D21 (0.0898) Completeness of supporting facilities D22 (0.0345) Superiority of geographical location D23 (0.0395) |

| Score Range | Xiamen | Zhangzhou | Quanzhou | Putian | Fuzhou | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score ≥ 80 | 23 buildings | 6 buildings | 11 buildings | 12 buildings | 6 buildings | 58 buildings |

| 70 ≤ Score < 80 | 16 buildings | 16 buildings | 13 buildings | 11 buildings | 18 buildings | 74 buildings |

| 60 ≤ Score < 70 | 8 buildings | 10 buildings | 6 buildings | 0 buildings | 23 buildings | 47 buildings |

| Score < 60 | 13 buildings | 8 buildings | 18 buildings | 10 buildings | 19 buildings | 68 buildings |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hu, J.; Wu, H.; Huo, F.; Chen, Z. Recognition and Evaluation of Architectural Heritage Value in Fujian Overseas Chinese New Villages. Buildings 2025, 15, 2336. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15132336

Hu J, Wu H, Huo F, Chen Z. Recognition and Evaluation of Architectural Heritage Value in Fujian Overseas Chinese New Villages. Buildings. 2025; 15(13):2336. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15132336

Chicago/Turabian StyleHu, Jing, Hanyi Wu, Fan Huo, and Zhihong Chen. 2025. "Recognition and Evaluation of Architectural Heritage Value in Fujian Overseas Chinese New Villages" Buildings 15, no. 13: 2336. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15132336

APA StyleHu, J., Wu, H., Huo, F., & Chen, Z. (2025). Recognition and Evaluation of Architectural Heritage Value in Fujian Overseas Chinese New Villages. Buildings, 15(13), 2336. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15132336