1. Introduction

With the continuous development of urban construction, the number of engineering projects has shown a consistent growth trend. However, due to the inherent complexity of construction projects and variations in contract management capabilities among project construction units, frequent disputes over construction contracts have emerged, posing challenges to the development of the construction industry [

1]. Construction project contract management is a crucial component of overall project management. The project contract outlines the fundamental rights and obligations of the parties involved, serving as the legal foundation for fulfilling responsibilities and exercising rights [

2]. Contract management often features a long duration, frequent changes, and complex implementation processes. When disputes arise, the construction contract becomes a key textual resource for resolving conflicts, as well as an essential legal document for judicial proceedings. Strengthening contract management has a significant positive impact on regulating the behavior of construction entities. It encourages all parties to adhere strictly to their contractual obligations, effectively manage conflicts, and contribute substantially to the development of China’s construction market [

3].

According to data from the China Judgement and Documentation Network, the number of construction contract dispute cases has surpassed 1.3 million nationwide since 2011, indicating a concerning situation for construction contract management [

4]. This rise not only disrupts the normal order of the construction market but also places significant strain on judicial resources. The inherent complexity of construction projects, including the involvement of numerous parties and substantial capital investment, introduces a range of uncertainties during contract execution. These uncertainties increase the risk associated with contract performance and can lead to disputes and claims, thereby creating a latent danger of potential legal conflicts [

5]. In engineering practice, many construction engineering contract disputes are resolved through court judgments. Following these decisions, one party may appeal to a higher court, often concentrating on specific aspects of the claims. Consequently, first-instance judgments frequently reflect the complexities of construction engineering contract disputes, while second-instance cases provide further insights into these complexities [

6]. Compared to first-instance cases, second-instance judgments often involve more in-depth legal reasoning, stricter evidence review, and clearer interpretations of disputed issues. Therefore, analyzing second-instance cases can more accurately reveal the core risk characteristics and dispute patterns in construction engineering contracts.

With this in mind, this study utilizes civil second-instance judgment documents from 2017 to 2021 concerning construction engineering contract disputes in the Yangtze River Delta (YRD) Economic Zone (comprising Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Anhui provinces), sourced from China’s judicial online case database. Through descriptive statistics, and other analytical techniques, the research conducts an in-depth analysis of the complex characteristics of litigation dispute points and cited legal provisions. This approach aims to identify key risk factors in construction engineering contract management and pinpoint dispute-prone areas. Corresponding prevention and control measures are proposed from both governmental and enterprise perspectives, offering valuable references for contract risk management among construction project participants.

2. Literature Review

Research on risk management in construction engineering contracts spans multiple domains, encompassing fundamental contractual elements such as bidding, contract performance, change claims, and the intersection of contract management with project management and cost control. Željko and Ante examined construction contract elements from a project management perspective, emphasizing the legal dimensions of construction projects and highlighting the significance of initial project preparation and the role of competent project managers [

7]. Bruner’s detailed analysis of the International Federation of Consulting Engineers (FIDIC) Red Book contracts, with sentence-by-sentence international annotations, offers valuable insights into international construction contracts [

8]. Debra addressed the challenges in contract naming, terminology, and version control by providing comprehensive contract overviews and search methodologies [

9]. Rachelle and Naseem investigated the readability and comprehensibility of construction contracts in Malaysia’s rapidly growing construction industry, demonstrating that plain language enhances contract clarity [

10]. Theesen and Milner cautioned against fitness-for-purpose clauses in South African construction contracts, stressing the obligations of consultants and contractors to ensure design and construction suitability [

11]. Zhu et al. analyzed risk sources in construction contract management processes and proposed measures to mitigate contractual risks in projects [

12].

In terms of the quantitative risk analysis and evaluation of engineering ontracts, Yan and Ma employed fuzzy matrix methods to construct a knowledge base for construction project contracts, using fuzzy weighted closeness to identify similar case contracts and determine contractual terms [

13]. Keith et al. utilized logistic regression to model the relationship between potential indices and construction dispute likelihood, offering a risk warning mechanism and insights into root causes [

14]. Tien et al. addressed the gaps in risk factor chains, sources, and impacts in international construction joint ventures (ICJVs) by establishing the RSIAM profile, which systematically manages risk factors across project phases [

15]. Purva and Neeraj proposed an integrated blockchain-based framework to enhance contract efficiency, transparency, and security, addressing long-standing dispute resolution challenges [

16]. Bassan and Rabitti introduced “Contract on Chain,” a blockchain-enhanced negotiation process leveraging third-generation public chains [

17].

Previous studies have demonstrated critical aspects of contract disputes. Shi examined the relationship between interest and liquidated damages in construction contracts, revealing practical disagreements over claims [

18]. Agapiou explored the Technology and Construction Court’s (TCC) use of mediation and arbitration to expedite dispute resolution [

19]. Ndekugri emphasized the importance of lifecycle management in NEC3 contracts to mitigate delayed disputes [

20]. Liu et al. analyzed international construction disputes, using Ethiopia as a case study to advocate for case-based reasoning in dispute resolution [

21]. Zhang demonstrated the application of risk management plans in large-scale infrastructure projects, such as the Greater Paris Express, underscoring the need for tailored risk strategies [

22]. Zhai’s empirical study of 216 marine environmental public interest litigation cases in China (2015–2022) highlighted the effectiveness of first-instance judgments and alternative dispute resolution [

23].

While prior studies on engineering contract disputes have contributed valuable insights—ranging from contractual element analysis to qualitative and quantitative risk assessments—most rely on limited case samples and focus on individual legal or technical aspects. Consequently, they fail to provide a comprehensive and data-driven understanding of contract risks across broader judicial contexts. To address this gap, the present study adopts a large-scale empirical approach by analyzing second-instance judicial cases, thereby enabling multi-dimensional characterization of contractual risks. These dimensions include regional dispute distribution, terminology patterns, legal citation frequencies, and the dynamics of appellate adjudication. This approach offers a novel analytical framework and contributes new empirical evidence to the study of risk governance in construction contract management.

The YRD Economic Zone, encompassing Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Anhui, represents one of China’s most economically dynamic and innovative regions. With rapid growth in the construction industry and a surge in construction projects, the region’s judicial judgments on contract disputes exhibit distinct regional and industry characteristics [

24]. Analyzing engineering contract risks through adjudication data provides deep insights into legal applications, judicial practices, and contractual performance issues, enabling the formulation of targeted countermeasures. These findings offer valuable references for resolving construction engineering contract disputes nationwide [

25].

3. Framework for Risk Characterization of Engineering Contract Dispute Cases

3.1. Research Framework

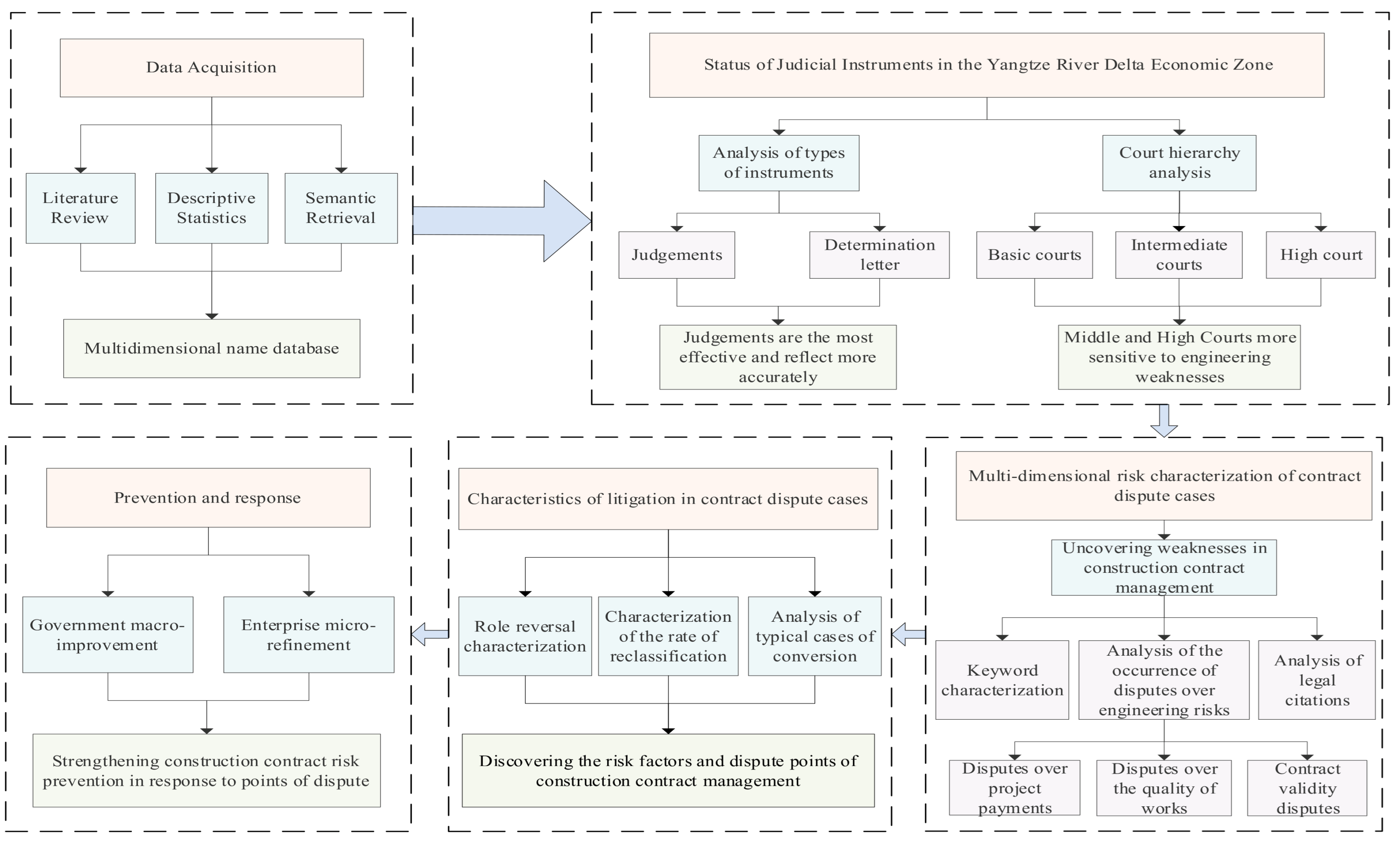

This study utilizes civil second-instance cases from the YRD Economic Zone (comprising Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Anhui provinces) between 2017 and 2021 as its primary data source. Through an in-depth analysis of cited legal provisions and litigation causes, the research identifies potential risks and dispute-prone aspects in construction engineering contract management. The study employs a combination of a literature review, descriptive statistics, and keyword search methods for data collection and analysis. The research framework is illustrated in

Figure 1.

3.2. Collection of Data on Second-Instance Cases of Engineering Contract Disputes

In this study, an advanced search was conducted on the China Judgments Online database, with the following parameters: the document type was set to “judgment,” the case type to “civil case,” the keyword to “construction engineering contract,” and the subject matter to “construction engineering contract dispute.” The geographical scope was limited to Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Anhui provinces, while the court levels included basic courts, intermediate courts, and high courts. The trial procedure was specified as “Civil Second Instance,” and the judgment dates ranged from 2017 to 2021. After excluding duplicate entries, a total of 349 judgments related to construction engineering contract disputes in the YRD Economic Zone were retrieved. The distribution of these cases is illustrated in

Figure 2. These 349 s-instance cases were systematically organized and analyzed, with the collected data cleaned, extracted, and calibrated. The analysis focused on key aspects such as basic case information, types of contract disputes, dispute focal points, and second-instance judgment revisions. A multi-dimensional database was then constructed based on these findings.

The case distribution shows notable regional differences. Jiangsu maintained a high volume of disputes across the years, while Anhui peaked in 2019. Zhejiang exhibited a clear downward trend, and Shanghai consistently had the lowest number of cases. These variations reflect regional disparities in dispute frequency and judicial practices, forming a solid foundation for subsequent multi-dimensional analysis of contract characteristics.

3.3. Analysis of Decision Documents in Engineering Contract Dispute Cases

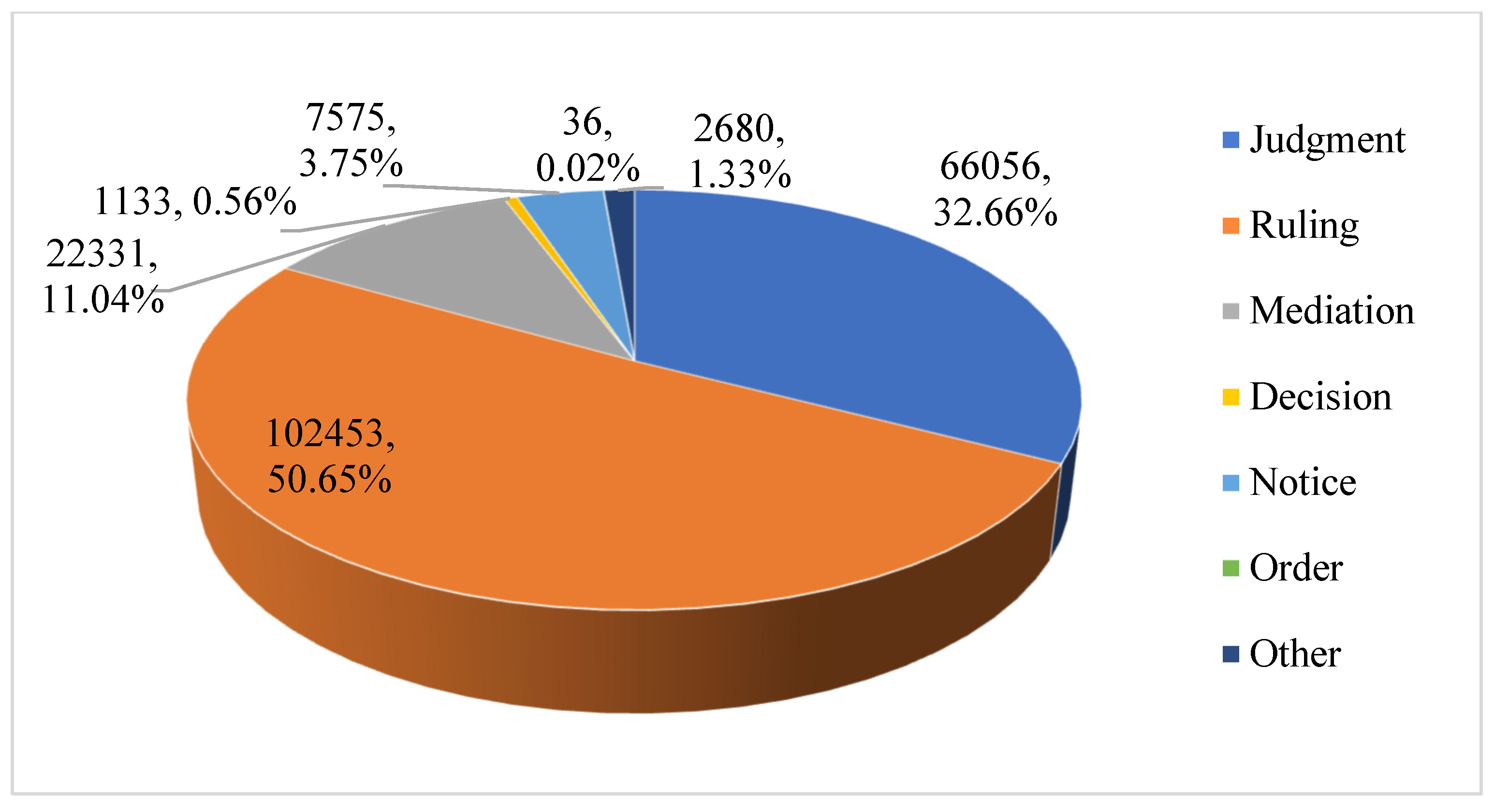

3.3.1. Typological Analysis of Adjudicatory Instruments

In China, judicial instruments encompass various types, primarily including judgments, rulings, notifications, conciliations, and decisions. Among them, a judgment is a legal instrument issued by the People’s Court to declare the final determination of a case. It establishes the rights and obligations of the parties based on ascertained facts, evidence, and relevant legal provisions in civil, criminal, administrative, or other legally stipulated cases [

26]. Judgments possess legal effect and represent the court’s definitive conclusion on a case. A ruling, on the other hand, is issued by the People’s Court during the trial of a civil case or the enforcement of civil judgments to address procedural matters, ensuring the smooth progression of judicial activities. Rulings are typically written decisions that deal with issues other than the substantive disputes between the parties [

27]. A notice is issued by the People’s Court to inform the parties or relevant entities of specific matters, requiring them to fulfill certain obligations. While notices do not constitute the court’s conclusions or produce substantive legal effects, they play a crucial role in facilitating the litigation process and ensuring the exercise of litigation rights and obligations. Conciliation is a judicial instrument issued by the People’s Court, formalizing an agreement reached by the parties through consultation. Once signed, conciliation agreements have legal effect and are formally recorded. A decision is issued by the People’s Court to address procedural or certain substantive issues arising during the trial or enforcement of a case. Decisions are applicable in first-instance, second-instance, and enforcement procedures.

As illustrated in

Figure 3, the number of judicial judgments and rulings in the YRD Economic Zone over the past five years has demonstrated that judgments and rulings constituted the primary types of judicial instruments issued in the region.

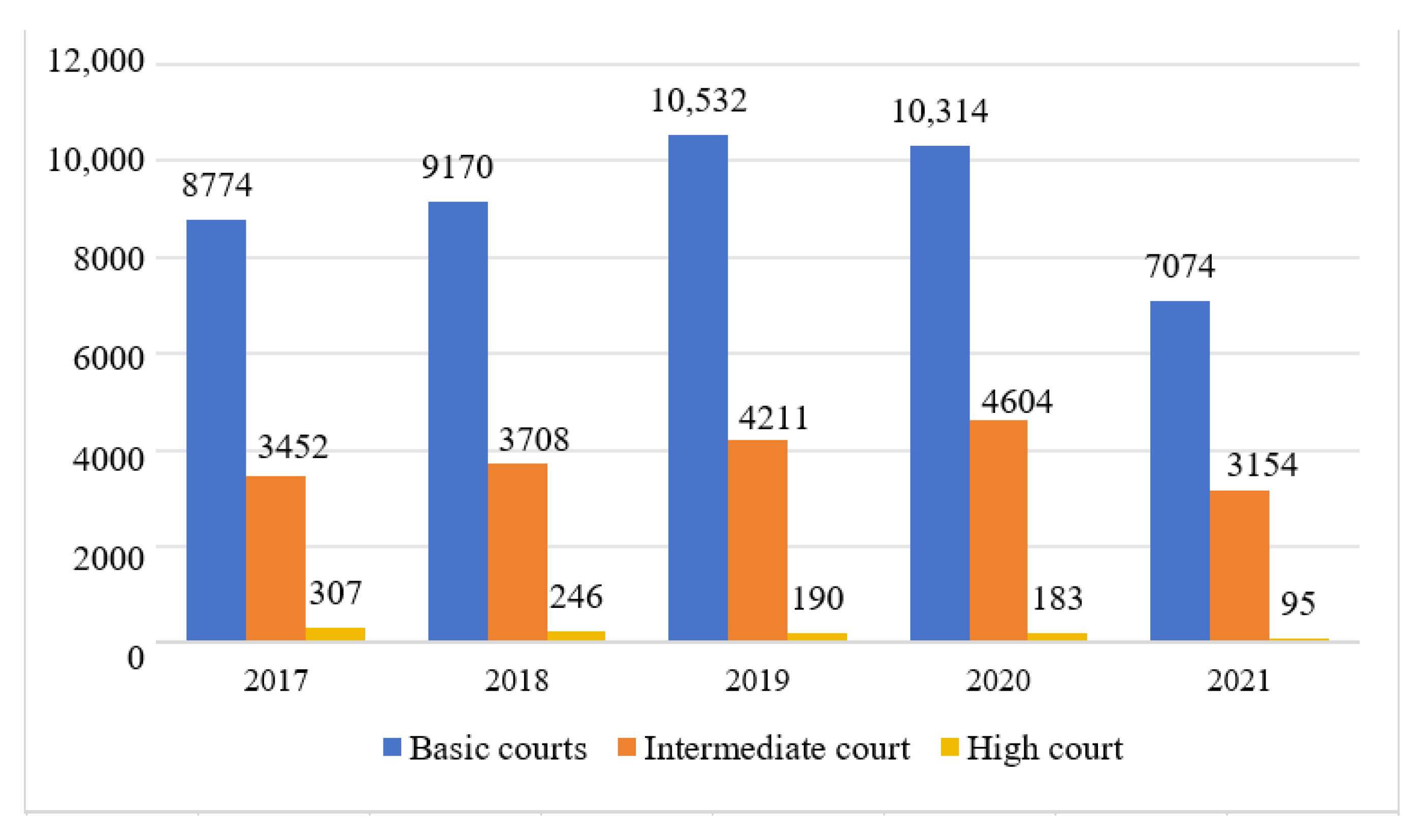

3.3.2. Hierarchical Analysis of the Magistrates’ Courts

Courts at various levels collectively form China’s comprehensive judicial system, ensuring the fairness and efficiency of legal proceedings. Basic-level courts, serving as the foundation of China’s judicial framework, bear the critical responsibility of adjudicating first-instance criminal, civil, and administrative cases, as well as handling cases remanded for retrial by higher People’s Courts. Intermediate courts, functioning as municipal judicial bodies, primarily review appeals and protests against judgments and rulings from basic-level courts, in addition to adjudicating certain first-instance cases. Higher courts, operating at the provincial, autonomous-region, and municipality levels, not only exercise judicial authority by the law but also oversee and supervise the judicial work of lower-level courts.

Figure 4 illustrates the distribution of judgment cases across all levels of courts in the YRD Economic Zone from 2017 to 2021.

It was evident that the number of civil cases handled by basic courts was the highest, followed by intermediate courts, while higher courts adjudicate the fewest civil cases. As the primary judicial institutions closest to the public, basic courts serve as the main venues for resolving civil disputes. However, among the second-instance appeals processed by intermediate and higher courts, contractual risk disputes tend to be more complex, challenging, and difficult to adjudicate, rendering them highly representative. The multi-dimensional risk characterization of second-instance contract dispute cases across all court levels aims to identify and analyze latent risks and dispute points in construction contract management. This analysis provides valuable references and insights for enhancing corporate engineering contract management practices.

4. Multi-Dimensional Risk Characterization of Engineering Contract Dispute Cases

4.1. Keywords of Judgment Instruments in Contractual Dispute Cases

In addition to essential keywords such as “construction works” and “contract,” which are inherently related to construction contract disputes, other significant keywords associated with engineering contract disputes include the following: interest, contract nullity, period of performance, contractual relationship, right of priority, appraisal, joint and several liability, illegal subcontracting, quality of work, and affiliation.

Contract Nullity: It refers to the absence of essential elements required for a contract to be legally effective, rendering the contract void from its inception. Such contracts fail to produce the intended legally binding effects. Common scenarios include the following: the incapacity of the contracting party to perform civil acts, false representation of intent, violation of mandatory legal or administrative provisions, contravention of public order and morals, malicious collusion harming others’ interests, fraud or coercion undermining national interests, legal forms concealing illegal purposes, and non-compliance with statutory requirements regarding content or form [

28].

Right of Priority: This can be classified as priority in rem and priority of claims based on its nature. Priority in rem includes, for example, the pre-emptive right of a co-owner to purchase shared property, while priority of claims is reflected in specific claims, such as those outlined in bankruptcy law. In construction project contract disputes, if a contractor has not been paid for completed work, they are entitled to priority compensation. This right holds a superior legal status, taking precedence over mortgages and other ordinary claims, thereby ensuring the contractor’s economic security during contract performance [

29].

Payment: This refers to the object of the creditor’s claim, typically considered the subject of the debt. It involves the debtor providing a benefit to the creditor as stipulated by the contract or law [

30].

Delivery: This denotes the legal act of formally and effectively transferring possession of the subject matter or its ownership documents to the transferee, in accordance with legal provisions or party agreements. Delivery is a critical aspect of contract performance, signifying the fulfillment of the contractual rights and obligations of both parties [

31].

The detailed definitions of keywords are provided in

Table 1; the summarized keywords for second-instance engineering contract dispute cases are shown in

Table 2.

The study identifies three primary risks in construction contract disputes: (1) risks of construction payment disputes: these primarily encompass disputes over the amount of construction payments, the timing of payments, deposits/interest rates, claims arising from construction changes, and issues regarding the priority of compensation; (2) risks of construction quality disputes: these mainly involve disputes related to construction quality standards, compliance with mandatory provisions, and quality appraisal outcomes; and (3) risks of contract validity disputes: these primarily include disputes over contractual relationships, illegal subcontracting practices, the qualifications of affiliated entities, etc. These findings highlight the critical areas of contention in construction contract disputes, providing valuable insights for risk management and dispute resolution strategies.

4.2. Characteristics of Legal Provisions Cited in Case Judgments on Contractual Disputes

Through an analysis of the legal provisions cited in the judgment documents of first- and second-instance judicial cases, it was found that the three most frequently cited legal provisions are the Contract Law of the People’s Republic of China, the Interpretation of the Supreme People’s Court on the Application of Law in Hearing Cases of Disputes over Construction Engineering Contracts, and the Civil Procedure Law of the People’s Republic of China. These findings are summarized in

Table 3.

The Contract Law of the People’s Republic of China is a legislative framework designed to comprehensively safeguard the lawful rights and interests of contracting parties, maintain the stability of social and economic order, and promote the advancement of socialist modernization. Its key provisions include a clear definition of contracts, the fundamental principles of contract formation, the legal effects of contracts, the requirements for contract performance, the definition of liability for breach of contract, and the conditions and procedures for contractual modifications. These provisions offer comprehensive, systematic, and standardized legal guidance for contractual activities.

The Interpretation of the Supreme People’s Court on the Application of Law to the Trial of Cases of Disputes over Construction Engineering Contracts specifies the circumstances under which a contract may be deemed invalid, the validity of a winning contract, and the handling of contracts after invalidation. The Civil Procedure Law of the People’s Republic of China, a fundamental law regulating civil litigation activities, aims to protect the litigation rights of parties and ensure the fair and timely adjudication of civil cases by the People’s Courts. It outlines the tasks, scope of application, and basic principles of civil litigation while clarifying the adjudicative powers of the People’s Courts.

Construction contracts primarily regulate the rights and obligations between the construction unit and the other party during the project, covering aspects such as project quality, duration, payment terms, and other contractual provisions. These are primarily governed by the Contract Law of the People’s Republic of China and relevant construction regulations and norms. The Civil Procedure Law of the People’s Republic of China, on the other hand, regulates civil litigation activities, establishing the basic principles, systems, and procedures for civil litigation to protect the litigation rights of parties and uphold judicial fairness. Given that the primary focus of this study is the risk analysis of construction engineering contracts, the relevance of the Civil Procedure Law of the People’s Republic of China is relatively limited. Therefore, this paper further analyzes only the Contract Law of the People’s Republic of China and the Interpretation of the Supreme People’s Court on the Application of Law to the Trial of Cases of Disputes over Construction Engineering Contracts, as detailed in

Table 4.

Through analysis of the relevant legal provisions cited, potential risk points in construction engineering contracts can be identified and reflected. The study reveals that the primary risks of disputes in such contracts include disputes over construction payments, disputes over work schedules, and disputes over the validity of the contract.

Dispute Risks Related to Project Payments: These encompass issues such as the calculation of project quantity, determination of project price, interest calculations, and payment timing.

Dispute Risks Related to Work Schedules: These involve conflicts over performance periods, completion dates, and project acceptance.

Dispute Risks Regarding Contract Validity: These include concerns about the qualifications for contract enforcement, illegal subcontracting practices, and the allocation of responsibility, among other associated risks.

These findings highlight the critical areas of contention in construction contracts, providing valuable insights for risk management and dispute resolution strategies.

4.3. Characterization of the Occurrence of Engineering Risk Disputes in Contract Dispute Cases

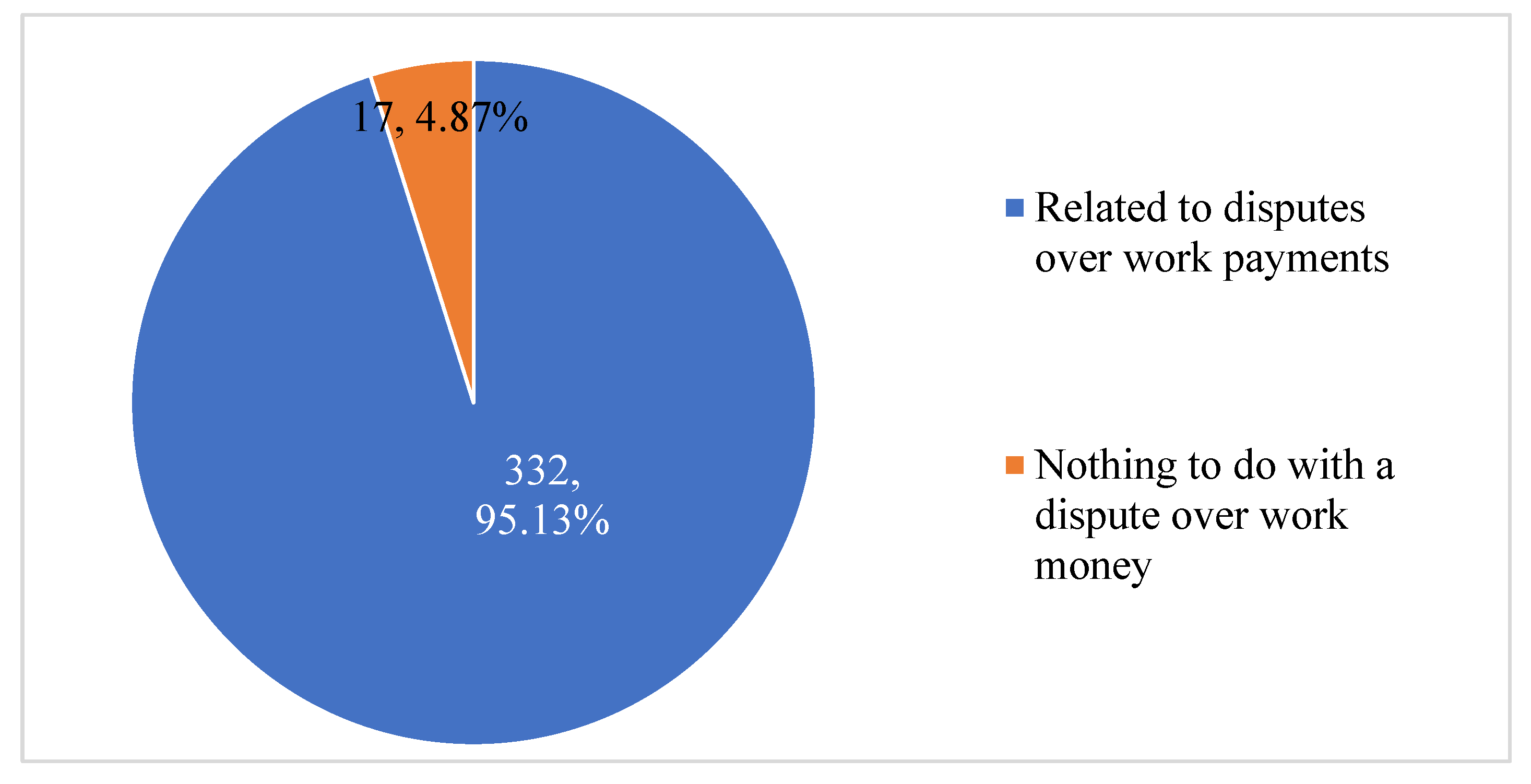

4.3.1. Characterization of the Risk Profile of Payment Disputes in Construction Contracts

Given that construction contracts typically involve substantial financial sums, complex engineering techniques, and extended timelines, the contractual content is often highly intricate. During contract performance, disputes frequently arise due to inconsistent interpretations or misunderstandings of the contract terms by the involved parties. The analysis of the data presented in the table above reveals that project payment disputes constitute the primary risk factor in construction contract disputes. Consequently, studying cases of project payment disputes is of paramount importance.

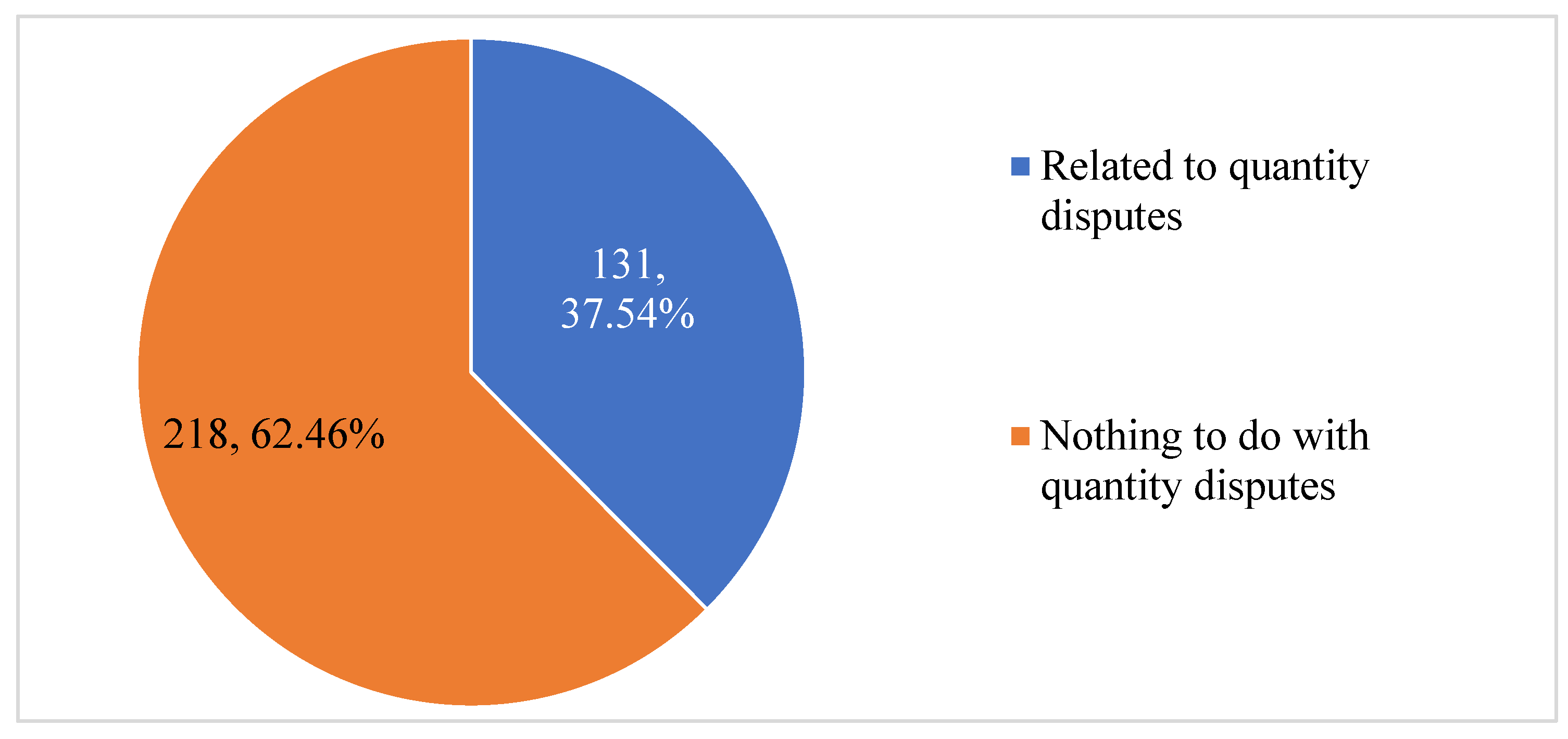

Based on the statistical analysis of 349 cases, the correlation between these cases and project payment disputes is examined, with the results illustrated in

Figure 5.

To further deepen our understanding of the case characteristics, cases closely related to the quantity of work were additionally filtered, and corresponding charts were generated as shown in

Figure 6 to facilitate visual comparison and analysis.

The findings indicated that disputes over project payments were a core risk factor triggering construction contract disputes. A detailed examination of the judgment documents from relevant cases reveals that the subject matter and contractual relationships were not inherently complex. However, the frequent progression of these cases to the second-instance stage can be attributed to two primary factors: (1) one party’s inability to fulfill payment obligations due to financial constraints and (2) dissatisfaction with the first-instance judgment, prompting parties to appeal for a more favorable ruling. These factors contribute to the large number of construction payment cases reaching the second-instance stage.

Cases involving project payment disputes were generally more straightforward to define and are often upheld by the court when supported by sufficient and truthful evidence. In contrast, disputes over the quantity of work are more challenging to resolve due to ambiguities in determining the actual work completed. The prevalence of project payment disputes over quantity disputes stems from the substantial financial sums involved and the multiple stages and conditions in the payment process. These complexities create numerous points of contention, making it difficult for parties to reach a compromise and increasing the likelihood of disputes escalating into litigation.

4.3.2. Characterization of the Risk Profile of Disputes Related to the Quality of Work

Engineering quality is intrinsically linked to building safety, as high-quality construction ensures that structures can withstand various external factors throughout their design and operational lifespan, thereby safeguarding lives and property. Furthermore, superior engineering quality extends the service life of buildings, reducing the economic and time costs associated with maintenance, renovations, and repairs. This not only minimizes long-term operational expenses but also generates greater societal economic benefits. Consequently, studying engineering quality dispute cases is essential for understanding quality and safety issues in the construction process and plays a critical role in preventing such disputes. Based on a statistical analysis of 349 cases in the database, the proportion of disputes related to engineering quality was calculated.

Quality-related disputes accounted for 17% of the cases, reflecting more than a numerical proportion—it serves as a compelling empirical indicator of systemic vulnerabilities within project governance frameworks. The prevalence of such disputes reveals recurring issues in foundational processes, including inadequate feasibility assessments, insufficient geological surveys, compromised contractor oversight, and deviations from licensed design practices. These findings highlight the urgent need for rigorous, integrated governance across the entire project lifecycle, shifting from reactive dispute resolution to proactive quality assurance to ensure structural integrity and engineering safety.

4.3.3. Characterization of the Risk Profile of Disputes Related to the Validity of Contracts

The nullity of a contract refers to its lack of legal effect from the outset due to the absence of essential elements required for its validity. This determination primarily depends on the state’s stance and legal evaluation of the contract, reflecting the state’s regulation and intervention in contractual relations. Actions such as qualification deficiencies, illegal subcontracting, and breaches of contractual obligations could render a contract invalid.

Based on the statistical analysis of 349 cases in the database, the number and proportion of cases involving invalid contracts were calculated. The proportion of invalid contract cases was substantial, accounting for 43 percent of the total cases. The reasons for contract disputes are diverse and include issues such as the contractor’s lack of qualifications or exceeding qualification levels, the use of borrowed qualifications for dependent operations, illegal subcontracting or sub-subcontracting, incomplete contract terms, unclear agreements, and improper contract formation. These findings underscore the importance of stringent compliance with legal and regulatory requirements to ensure the validity and enforceability of construction contracts.

Before signing a contract, it is crucial to thoroughly understand the relevant laws and regulations to ensure that the contract’s content is legal and compliant. Additionally, both parties must possess the necessary qualifications and capacity to enter into the contract. The content and terms of the contract should be clear, precise, and unambiguous. Both parties should engage in comprehensive consultations regarding the key terms of the contract and reach a mutual agreement before signing. During the performance of the contract, any necessary modifications or termination must be carried out in accordance with applicable laws and the provisions of the contract. Both parties should engage in detailed discussions regarding the terms of such changes or termination and reach a consensus before implementing any adjustments. This approach ensures the integrity and enforceability of the contract while minimizing potential disputes.

5. Litigation Characterization of Contract Dispute Cases

Construction projects are typically characterized by substantial investments, prolonged implementation periods, and complex contractual relationships. As a result, contract disputes are often escalated from first-instance judgments to second-instance judicial decisions. A multi-dimensional analysis of second-instance judgment documents—centered on changes in litigation roles, modifications to judgments, and other relevant factors—has been conducted to further elucidate the litigation characteristics and inherent complexities of engineering contract disputes. Through this analysis, deeper insights into the dynamics of such disputes are provided, offering valuable implications for the enhancement of contractual governance and the improvement of dispute resolution mechanisms.

5.1. Characterization of Role Reversal in Litigation of Engineering Contract Disputes

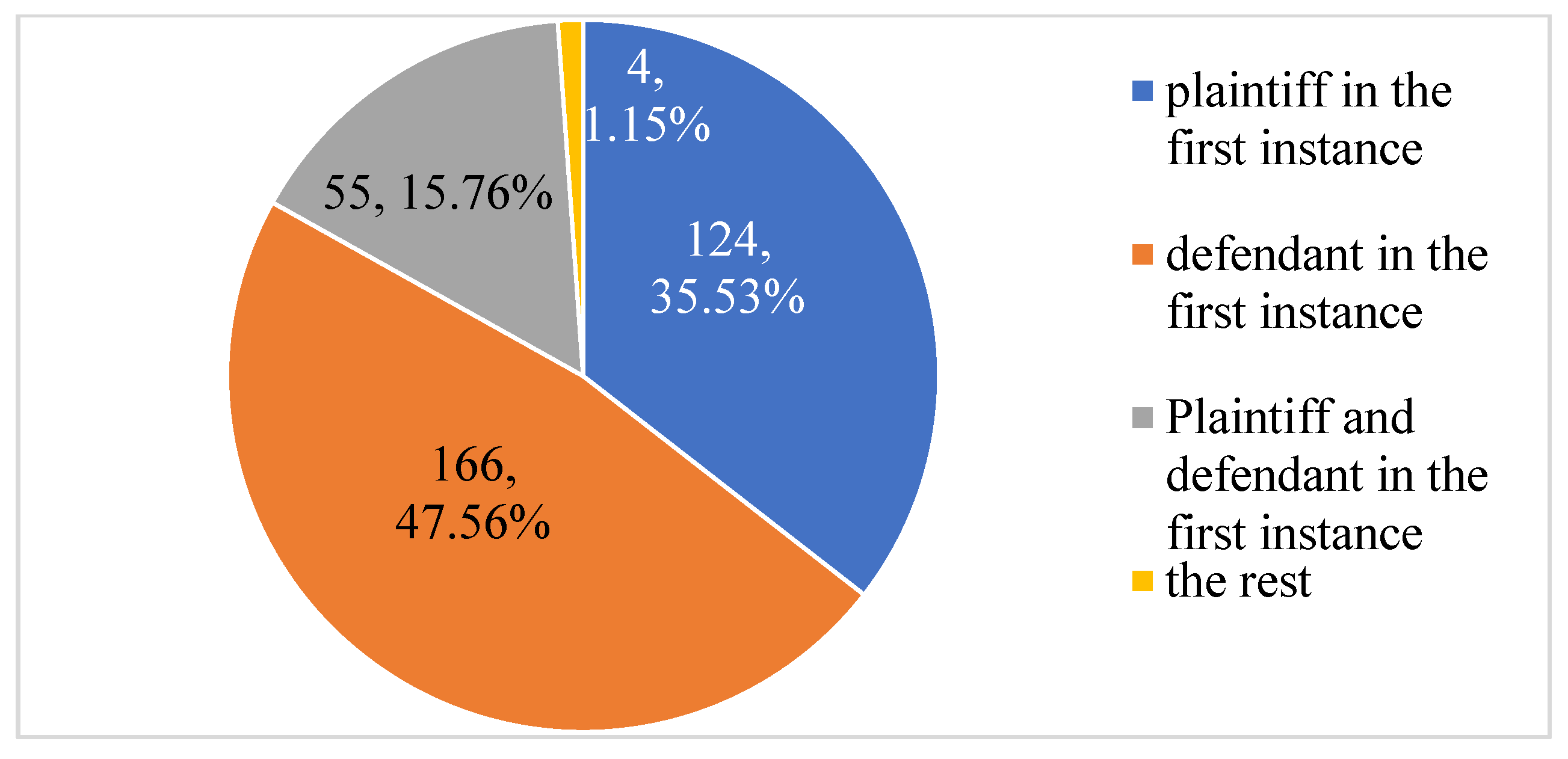

Litigation role switching in engineering contract dispute cases primarily occurs during the second-instance appeal, depending on whether the appellant was the plaintiff or the defendant in the first instance. In this study, the appellant refers to the party initiating the appeal, while the respondent refers to the opposing party. As illustrated in

Figure 7, there are four main types of appellants in the second instance: (1) the plaintiff from the first instance, (2) the defendant from the first instance, (3) both the plaintiff and the defendant as co-appellants (e.g., Case No. (2016) Su09minzhenzhen 4530), and (4) cases involving multiple parties, such as two plaintiffs and one defendant (e.g., Case No. (2018) Anhui16minzhen 2731), one plaintiff and two defendants (e.g., Case No. (2020) Su01 Civil Final No. 2310), and other scenarios involving third parties (e.g., Case No. (2017) Anhui 11 Civil Final No. 879, with one defendant and three third parties, or Case No. (2017) Anhui Civil Final No. 537). Among the analyzed cases, 166 cases (48%) involved the defendant from the first instance as the appellant, while 124 cases (35%) involved the plaintiff as the appellant. The higher number of appeals by defendants in the first instance can be attributed to their dissatisfaction with the initial judgment, prompting them to seek a more favorable legal interpretation and outcome. For example, in Case No. (2015) Taijingqiao Minchu 649, the defendant in the first instance, dissatisfied with the civil judgment from the People’s Court of Jingjiang City, Jiangsu Province, filed an appeal. Consequently, the second-instance court revoked the first-instance judgment after reassessing the facts. This trend highlights the complexity and contentious nature of engineering contract disputes, particularly the propensity for defendants to challenge unfavorable rulings in pursuit of a more advantageous legal resolution.

Among the analyzed cases, 151 cases (43%) involved the construction contractor as the appellant, while 198 cases (57%) involved other parties as the appellants. In 41.5% of these cases, the construction contractor was in the position of the defendant in the second instance. Construction contractors are involved in a significant number of contracts due to the high volume of projects they undertake, which increases the complexity of communication and coordination with other involved parties. Consequently, contractors face heightened risks and challenges during contract management and performance. Moreover, many construction contractors fail to thoroughly assess and understand the qualifications, credibility, and performance capabilities of their contracting partners. This lack of due diligence in reviewing contract terms and mitigating potential risks often results in contractors being forced into the position of the defendant in litigation. To address these challenges, contracting parties must carefully analyze the specific circumstances of each case and develop appropriate response strategies. Additionally, contractors should strengthen project management practices to ensure contract fulfillment and maintain control over the quality of work, thereby preventing potential contractual risks. These measures can help mitigate disputes and enhance the overall effectiveness of contract management in the construction industry.

5.2. Characterization of the Rate of Revision in Litigation of Engineering Contract Disputes

China’s legal system employs a second-instance trial mechanism, which not only ensures judicial fairness and the accurate application of the law but also robustly safeguards the legitimate rights and interests of the parties involved. When a second-instance judgment modifies the first-instance ruling, it represents an adjustment to the initial outcome, indirectly reflecting the complexity and variability of construction engineering contract disputes. This system is designed to maintain continuity and fairness in the application of the law, particularly in resolving intricate contractual disputes. Among the 349 cases analyzed in the database, the judgments were categorized into “revised” and “affirmed” outcomes. A total of 239 cases (68%) were upheld, while 110 cases (32%) were revised, indicating a relatively high rate of judgment modification in second-instance proceedings. This highlights the dynamic nature of construction contract disputes and the critical role of the second-instance system in ensuring judicial accuracy and fairness.

The primary reasons for second-instance judgment revisions include (1) partial mishandling in the first-instance judgment, (2) the submission of new evidence during the second instance, (3) errors in the application of the law or determination of facts in the first instance, and (4) combinations of these factors, as illustrated in

Figure 8. Among these, the majority of cases (61 cases, 56%) were revised due to partial mishandling in the first instance, followed by new evidence submissions. The fewest revisions stemmed from errors in factual determinations during the first instance.

The primary reasons for second-instance revisions were the mishandling of first-instance judgments and insufficient evidence, potentially stemming from judges’ lack of professionalism, trial experience, or diligence, leading to biased or incomplete hearings. Additionally, revisions often resulted from parties failing to collect and present adequate evidence initially, prompting new submissions during the second instance. To mitigate these issues, enhancing judge training and education is essential to improve professionalism and trial competence. Strengthening judicial oversight mechanisms and optimizing resource allocation are also crucial to ensure judicial fairness and efficiency.

5.3. Typical Cases of Litigation Reversal in Engineering Contract Disputes

Four main reasons drive second-instance revisions in contractual disputes: (1) partial mishandling of first-instance judgments, (2) the submission of new evidence, (3) errors in legal application, and (4) factual misdetermination in the first instance. These reasons may co-occur, as illustrated in the following cases:

Judicial Discretion and Mishandling: Judges must exercise discretion based on case specifics. However, improper use of discretion, such as failing to consider parties’ rights or abusing authority, can lead to flawed judgments. For example, in Case No. (2016) Shanghai 01 Civil Terminal 13443, the second-instance court corrected the first-instance judgment, which lacked a legal basis for requiring interest payments due to no breach of contract by the appellant.

New Evidence Submission: New evidence in the second instance can significantly alter case outcomes. In Case No. (2017) Zhe06 Minzhong339, the appellant submitted new evidence, leading the court to partially uphold the appeal and reverse the first-instance judgment.

Legal Application Errors: Correct legal application is crucial. In Case No. (2017) Su03 Minchu 4906, the first-instance court misapplied the law regarding the appellant’s right to priority compensation, which the second-instance court corrected.

Factual Misdetermination: Accurate fact finding is essential. In Case No. (2017) Su Minzhu 333, the first-instance court incorrectly concluded that the appellant’s claim for priority compensation had expired, a mistake rectified in the second instance.

Combined Factors: Multiple issues can lead to revisions. In Case No. (2019) Anhui 15 Civil Final No. 884, the first-instance court’s unclear factual findings and incorrect legal application were corrected in the second instance after new evidence emerged.

To minimize revisions, first-instance courts must ensure clear and complete factual determinations and accurate legal application. New evidence should ideally be submitted during the first instance, ensuring its authenticity, legality, and relevance. Strengthening judicial training and oversight can further enhance judgment accuracy and fairness.

6. Countermeasure Suggestions for Contracts Management

The construction engineering contract serves as the legal foundation defining the rights, obligations, and responsibilities of project stakeholders. The analysis of construction engineering contract disputes reveals that qualification affiliation cases constitute 37% (55 instances) of total cases, indicating a significant proportion. These issues often lead to disputes over contract validity, project payments, and construction quality.

From 2017 to 2021, China introduced a series of regulatory reforms to improve the legal environment for construction contracts, including revisions to the Construction Law, the introduction of the Civil Code (2021), and updates to qualification management regulations. These efforts aimed to address recurring issues such as false qualification affiliations and ambiguous contract terms. However, practical challenges remain, especially in the enforcement of legal provisions at the local level. Building upon the risk characteristics identified through second-instance litigation analysis, the suggestions are proposed and directed at government regulators and enterprise actors, with the aim of enhancing preventive capacity and achieving risk control across the engineering contract lifecycle.

Effective dispute prevention depends on strengthening institutional entry controls and early risk identification. Government agencies should enforce transparent qualification management and centralized registration systems to curb illegal affiliation and unauthorized subcontracting, issues frequently reflected in litigation. Enterprises should conduct thorough legal and financial due diligence, supported by structured internal review processes involving legal and technical advisors, to mitigate risks associated with contract invalidity, vague provisions, and non-compliance with mandatory legal norms.

During contract execution, risk control requires continuous supervision and responsive regulatory oversight. Government authorities are advised to implement digital supervision systems integrating progress tracking, payment verification, and quality inspection data to detect early signs of non-performance or payment default. Enterprises should adopt contract lifecycle management systems and internal audit mechanisms, maintaining real-time documentation and conducting regular compliance reviews to reduce risks related to delays, unilateral changes, and informal supplementary agreements.

In the dispute resolution phase, reducing litigation risk necessitates both institutional infrastructure and enterprise preparedness. Governments should expand access to alternative dispute resolution (ADR) mechanisms and ensure the consistent application of judicial interpretations to limit second-instance reversals. Enterprises should maintain comprehensive, trial-standard evidence archives covering contract execution, payments, and communications. The establishment of dedicated legal response teams can further enhance procedural efficiency and improve outcomes in mediation, arbitration, or litigation.

7. Conclusions and Future Research

Data mining and analysis of construction contract dispute cases offer valuable insights for risk management in construction projects. This study conducted a multi-dimensional risk characterization analysis of engineering contract dispute cases in the Yangtze River Delta Economic Zone (Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Anhui Provinces) from 2017 to 2021, utilizing data from the China Judgments Online.

Most disputes are resolved at the grassroots-court level, while more complex cases are escalated to intermediate and high courts. This stratification highlights the varying levels of legal complexity and suggests the need for tailored dispute resolution approaches across judicial tiers. Risk of contract disputes includes high-frequency keywords and legal citations indicate that core risks center on project payments, construction quality, contract validity, and construction timelines, reflecting persistent areas of contention in engineering practice. In second-instance appeals, 48% were filed by first-instance defendants (166 cases), while 35% were filed by first-instance plaintiffs (124 cases). Contracting parties were defendants in 41.5% of cases, highlighting the complexity of contractual relationships and the need for improved risk management. In total, 68% of cases were upheld in the second instance, while 32% were revised. The reasons for revisions included improper handling of first-instance judgments (55.45%), new evidence submission (20.91%), errors in legal application (7.27%), factual misdetermination (6.36%), and combinations of these factors (10.00%).

The study’s contribution lies in its multi-dimensional risk characterization of construction contract disputes, expanding the geographical and temporal scopes of judicial data analysis. Limitations include a relatively small sample size and reliance on manual data processing. Although the COVID-19 pandemic affected the construction sector, the second-instance cases included in this study, mainly judged between 2020 and 2021, may not fully reflect the pandemic’s long-term impact due to the typical delay between dispute occurrence and final judgment. Future research should employ text mining techniques to identify additional risk patterns, providing more targeted recommendations to enhance risk management in construction engineering contracts.