Can Historical Environments Rival Natural Environments? An Empirical Study on the Impact of Campus Environment Types on College Students’ Mental Health

Abstract

1. Introduction

- For urban campuses with limited natural spaces, can built environments provide sufficient psychological restoration? What environmental characteristics drive these effects?

- Can historically rich campuses serve as viable alternatives to natural landscapes? How do their restorative mechanisms differ?

- Does explicit communication of cultural information in historical environments yield restoration comparable to natural settings?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Subject

- (1)

- Ordinary built environment lacking natural and historical elements (standard chain coffee shop in conventional building, P1);

- (2)

- Natural landscape environment without historical features (campus wetland park with rich ecosystem, P2);

- (3)

- Historically built environment with intentional historical narratives (independent coffee shop in century-old heritage building, P3);

- (4)

- Historically built environment with unintentional historical narratives (campus cultural gift shop in 50-year-old historical building, P4).

2.2. Participant

2.3. Experimental Procedure

2.3.1. Group Assignment and Counterbalancing

2.3.2. Pre-Experiment Protocol

2.3.3. HRV Measurement Protocol

2.3.4. Environmental Exposure Procedure

2.3.5. Post-Exposure Measurements and Questionnaires

2.3.6. Behavioral Control

2.4. Measurement

2.4.1. Measurement of Heart Rate Variability (HRV)

2.4.2. Psychological Measurement

3. Results

3.1. Heart Rate Variability

3.1.1. Comparison of Ordinary Built Environment and Historical Built Environment with Intentional Historical Information

3.1.2. Comparison of Historical Environment with Intentional Historical Narratives and Natural Landscape Environment

3.1.3. Comparison of Historical Built Environment Without Intentional Historical Information and Other Environments

3.2. Overview of Emotional State

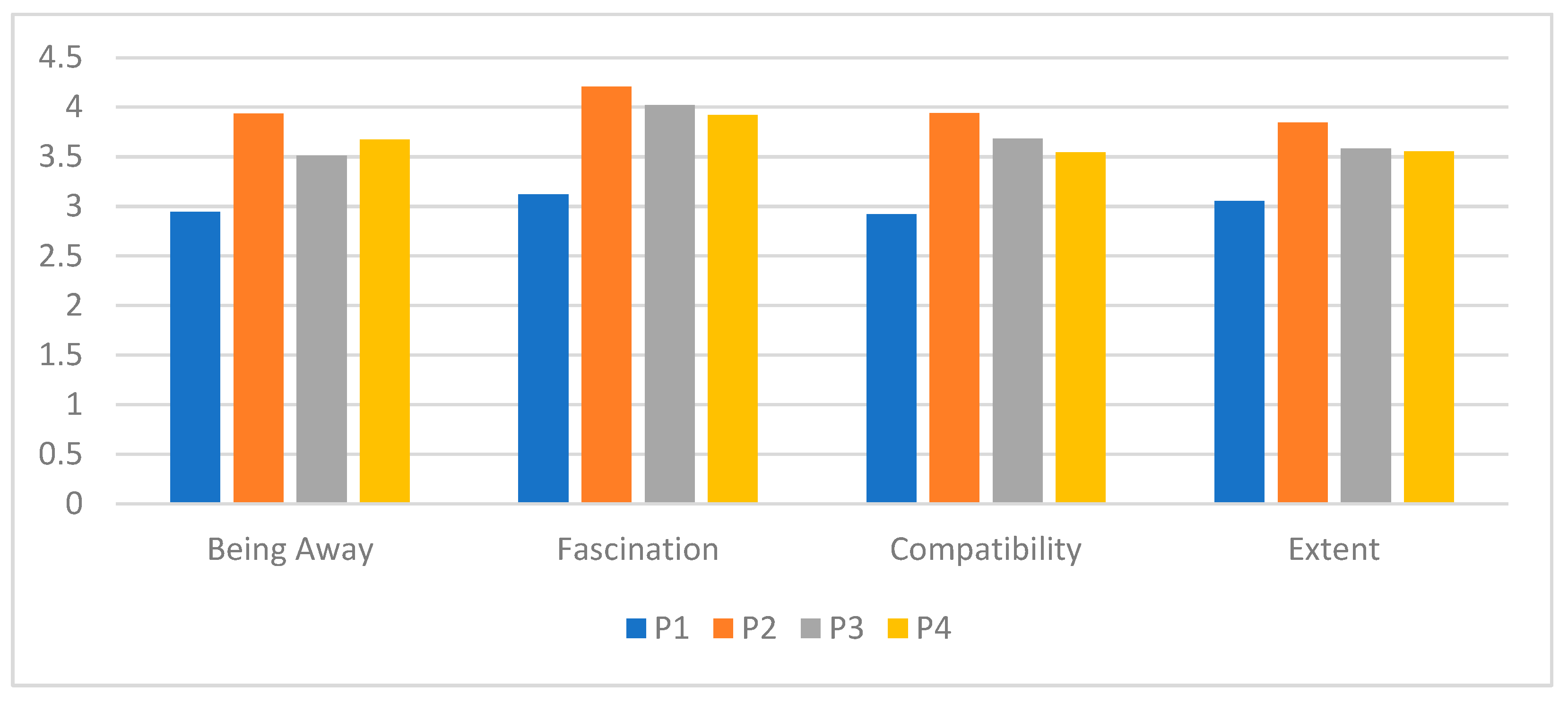

3.3. Perceptual Recovery Scale

4. Discussion

4.1. Physiological Findings and Implications

4.2. Psychological Restoration: Mood and Attention Dynamics

4.3. Integrated Effects of Physiological and Psychological Restoration

4.4. Limitations

- Increase sample size and conduct parallel studies across different universities to incorporate diverse campus cultures.

- Implement repeated measurements across the four seasons—spring, summer, autumn, and winter—to assess seasonal fluctuations.

- Perform stratified analyses by academic year, major, and geographic background to explore dynamic differences and interaction effects of environmental influences.

- Conduct cross-cultural field investigation or cross-border cooperative research to examine how variations in the interpretation of heritage symbols among different cultural groups affect the mechanisms and outcomes of restoration.

- Incorporate objective psychophysiological measures. Employ eye-tracking and neuroimaging techniques (e.g., EEG, fMRI) to objectively assess attentional restoration and underlying neural correlates elicited by natural versus historical environments.

- Adopt factorial experimental designs that systematically vary vegetation density and heritage-building features independently to disentangle the unique and interactive contributions of vegetation versus built heritage to restorative outcomes.

4.5. Practical Implications for Urban Planning and Research

- (1)

- In old urban areas with insufficient green spaces, priority should be given to “cultural-ecological composite restoration” (e.g., converting historical building courtyards into gardens or relic sites into parks) to compensate for natural space shortages [58];

- (2)

- Establishing “cultural restorative service zones” for historic districts, analogous to the “service radius” standards for natural environments, to ensure residents’ convenient access to culturally therapeutic scenes [59].

- (1)

- Introduce psychosocial benefit indicators (e.g., place attachment intensity, visitor mood enhancement) into heritage evaluation systems, shifting the focus from “preservation” to “active utilization”;

- (2)

- Incorporate historical environment restoration into Social Prescribing (SP) frameworks, collaborating with healthcare institutions to develop “cultural therapeutic pathways,” such as designing historic district walking therapies for anxiety patients.

- (1)

- Enhance “narrative-driven design” in historical building retrofits (e.g., using AR to reconstruct artisan construction processes), leveraging cultural resonance to amplify users’ sense of belonging and relaxation [61];

- (2)

- Integrate “biophilic design principles” (e.g., fractal patterns, organic geometries) with historic contexts by fusing traditional motifs with plant-inspired forms, achieving synergistic cultural-natural restoration [62].

5. Conclusions

- Historical built environments exhibit greater psychological restorative potential than ordinary built campus environments, as indicated by significantly higher HRV and PRS scores (p < 0.01). This finding suggests that environments containing historical information can contribute to attention restoration and psychological stress relief, to a certain extent.

- Environments with intentionally and explicitly conveyed historical information demonstrated stronger restorative effects than general historical environments, although the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.17). This result implies that information transmission should align with participants’ cultural cognition. This study indicates that when historical environments contain intentionally articulated historical information, they facilitate cognitive engagement and immersive experiences with historical narratives, thereby enhancing psychological stress alleviation and attention restoration.

- Natural landscape environments exhibit the strongest psychological restorative effects; however, environments that explicitly convey historical information can partially replicate these effects. Consequently, such environments can promote attention restoration and psychological stress relief to a comparable extent, supporting the “culture-nature” synergistic design concept.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| P1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Figure Index | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | R5 | R6 | R7 | R8 | R9 | R10 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T5 | T6 | T7 | T8 | T9 | T10 |

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | |

| GVI | 0% | 11.11% | 44.44% | 11.11% | 0% | 11.11% | 11.11% | 0% | 0% | 22.22% | 22.22% | 22.22% | 11.11% | 0% | 33.33% | 0% | 0% | 44.44% | 0% | 0% |

| P2 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Figure Index | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | R5 | R6 | R7 | R8 | R9 | R10 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T5 | T6 | T7 | T8 | T9 | T10 |

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | |

| GVI | 66.67% | 88.89% | 75% | 100% | 66.67% | 77.78% | 83.33% | 88.89% | 75% | 100% | 66.67% | 94.44% | 100% | 97.13% | 77.78% | 88.89% | 66.67% | 100% | 66.67% | 100% |

| P3 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Figure Index | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | R5 | R6 | R7 | R8 | R9 | R10 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T5 | T6 | T7 | T8 | T9 | T10 |

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | |

| GVI | 0% | 0% | 7.40% | 11.11% | 55.56% | 0% | 11.11% | 0% | 8.33% | 19.44% | 50% | 47.22% | 72.22% | 66.67% | 33.33% | 33.33% | 0% | 33.33% | 66.67% | 22.22% |

| P4 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Figure Index | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | R5 | R6 | R7 | R8 | R9 | R10 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T5 | T6 | T7 | T8 | T9 | T10 |

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | |

| GVI | 33.33% | 5.56% | 22.22% | 16.67% | 33.33% | 0% | 11.11% | 0% | 44.44% | 33.33% | 0% | 22.22% | 33.33% | 11.11% | 0% | 66.67% | 44.44% | 33.33% | 0% | 0% |

References

- Decleene, K.E.; Fogo, J. Publication Manual of the American Psychological AssociationPublication Manual of the American Psychological Association. Occup. Ther. Health Care 2012, 26, 90–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, J.M. Human-computer interaction: Psychology as a science of design. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1997, 48, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, X.X.; Zhang, B.; Chen, S.F.; Lin, Y.; Haans, A. Exploring the Impact of Daytime and Nighttime Campus Lighting on Emotional Responses and Perceived Restorativeness. Buildings 2025, 15, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The experience of nature: A psychological perspective. In The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1989; p. 340. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, C.S. Widespread likings. Science 1994, 263, 1161–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.Y.; Dong, S.N.; Chen, X.; Zhou, Q.Q.; Li, F.Y.; Wang, G.Y. Does Social Distancing Affect the Stress Reduction and Attention Restoration of College Students in Different Natural Settings? Sustainability 2024, 16, 3274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratman, G.N.; Hamilton, J.P.; Daily, G.C. The impacts of nature experience on human cognitive function and mental health. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2012, 1249, 118–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korpela, K.M.; Ylen, M. Perceived health is associated with visiting natural favourite places in the vicinity. Health Place 2007, 13, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, E.; Fukuda, S.; Nagano, J.; Hamajima, N.; Yamamoto, H.; Iwai, Y.; Nakashima, T.; Ohira, H.; Shirakawa, T. Psychological effects of forest environments on healthy adults: Shinrin-yoku (forest-air bathing, walking) as a possible method of stress reduction. Public Health 2007, 121, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amicone, G.; Petruccelli, I.; De Dominicis, S.; Gherardini, A.; Costantino, V.; Perucchini, P.; Bonaiuto, M. Green Breaks: The Restorative Effect of the School Environment’s Green Areas on Children’s Cognitive Performance. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malekinezhad, F.; Courtney, P.; Bin Lamit, H.; Vigani, M. Investigating the Mental Health Impacts of University Campus Green Space Through Perceived Sensory Dimensions and the Mediation Effects of Perceived Restorativeness on Restoration Experience. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 578241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aeschbach, V.M.; Schipperges, H.; Braun, M.A.; Ehret, S.; Ruess, M.; Sahintuerk, Z.; Thomaschke, R. Less is More: The Effect of Visiting Duration on the Perceived Restorativeness of Museums. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2022, 18, 940–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenngart Ivarsson, C.; Hagerhall, C.M. The perceived restorativeness of gardens—Assessing the restorativeness of a mixed built and natural scene type. Urban Urban Gree 2008, 7, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.Y.; Liu, J.H.; Li, H.Y. Restorative Effects of Multi-Sensory Perception in Urban Green Space: A Case Study of Urban Park in Guangzhou, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stragà, M.; Miani, C.; Mäntylä, T.; Bruine De Bruin, W.; Mottica, M.; Del Missier, F. Into the wild or into the library? Perceived restorativeness of natural and built environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 2023, 91, 102131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.W.; Zhang, J.J.; Liu, C.L.; Yang, Y. A Review of Attention Restoration Theory: Implications for Designing Restorative Environments. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scopelliti, M.; Carrus, G.; Bonaiuto, M. Is it Really Nature That Restores People? A Comparison with Historical Sites with High Restorative Potential. Front. Psychol. 2019, 9, 2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. Defining place attachment: A tripartite organizing framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalkrishnan, N. Cultural Diversity and Mental Health: Considerations for Policy and Practice. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sue, S.; Zane, N.; Hall, G.; Berger, L.K. The Case for Cultural Competency in Psychotherapeutic Interventions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2009, 60, 525–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlong, Y.; Finnie, T. Culture counts: The diverse effects of culture and society on mental health amidst COVID-19 outbreak in Australia. Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 2020, 37, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shedayi, A.A.; Xu, M.; Gonalez-Redin, J.; Ali, A.; Shahzad, L.; Rahim, S. Spatiotemporal valuation of cultural and natural landscapes contributing to Pakistan’s cultural ecosystem services. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 41834–41848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, J.; Luo, S.X.; Furuya, K.; Wang, H.X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Q.; Li, H.Y.; Chen, J. The Restorative Potential of Green Cultural Heritage: Exploring Cultural Ecosystem Services’ Impact on Stress Reduction and Attention Restoration. Forests 2023, 14, 2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S. Aesthetic and Affective Response to Natural Environment; Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1983; Volume 6, pp. 85–125. [Google Scholar]

- Herzog, T.R.; Colleen; Maguire, P.; Nebel, M.B. Assessing the restorative components of environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.Y.; Jiang, M.; Zhao, J.W. The Restorative Effects of Unique Green Space Design: Comparing the Restorative Quality of Classical Chinese Gardens and Modern Urban Parks. Forests 2024, 15, 1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Soto, J.; Suárez, L.; Ruiz-Correa, S. Exploring the Links Between Biophilic and Restorative Qualities of Exterior and Interior Spaces in Leon, Guanajuato, Mexico. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 717116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.K.; Zakaria, N.A.; Foo, K.Y. Psychological Restorative Potential of a Pilot on-Campus Ecological Wetland in Malaysia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, C.; Lyman, C.; Brown, G.; Hynson, B. Reclaiming public spaces: The case for the built environment as a restorative tool in neighborhoods with high levels of community violence. J. Community Psychol. 2022, 50, 2399–2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinemillioglu, M.O.; Akin, C.T.; Karacay, N. Relationship Between Green Areas and Urban Conservation in Historical Areas and Its Reflections: Case of Diyarbakir City, Turkey. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2010, 18, 775–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.X.; Xie, J.; Furuya, K. Assessing the Preference and Restorative Potential of Urban Park Blue Space. Land 2021, 10, 1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamali Tabrizi, S.; Abdelmonem, M.G. Contemporary construction in historical sites: The missing factors. Front. Arch. Res. 2024, 13, 487–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, Q.H.; Rong, S.; Jia, Y.H.; Dong, F.Q. Exploring the Impact of Campus Landscape Visual Elements Combination on Short-Term Stress Relief among College Students: A Case from China. Buildings 2024, 14, 1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, E.W.; Lombard, Q.K.; Best, N.; Smiley-Smith, S.; Quinn, J.E. Active and Passive Use of Green Space, Health, and Well-Being amongst University Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, T.T.; Wang, J.S.; Tian, H.T.; Zhang, R.X.; Chen, Y.X.; Chen, H. Campus landscape types and pro-social behavioral mediators in the psychological recovery of college students. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1341990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aikoh, T.; Homma, R.; Abe, Y. Comparing conventional manual measurement of the green view index with modern automatic methods using google street view and semantic segmentation. Urban Urban Gree 2023, 80, 127845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristiansen, J.; Korshoj, M.; Skotte, J.H.; Jespersen, T.; Sogaard, K.; Mortensen, O.S.; Holtermann, A. Comparison of two systems for long-term heart rate variability monitoring in free-living conditions—A pilot study. Biomed. Eng. Online 2011, 10, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skotte, J.H.; Kristiansen, J. Heart rate variability analysis using robust period detection. Biomed. Eng. Online 2014, 13, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleiger, R.E.; Stein, P.K.; Bigger, J.T., Jr. Heart Rate Variability: Measurement and Clinical Utility. Ann. Noninvas Electro. 2005, 10, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malliani, A.; Pagani, M.; Montano, N.; Mela, G.S. Sympathovagal balance: A reappraisal. Circulation 1998, 98, 2640–2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.H.; Yin, J.; An, Y.; Wang, J.H.; Qiu, J. The structural validity and latent profile characteristics of the Abbreviated Profile of Mood States among Chinese athletes. BMC Psychiatry 2024, 24, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.; Kaiser, F.G.; Bowler, P.A. Further Development of a Measure of Perceived Environmental Restorativeness; Institute of Housing Research; Uppsala University: Uppsala, Sweden, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K.; Snyder, M.; Krichbaum, K. Translation and equivalence: The Profile of Mood States Short Form in English and Chinese. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2002, 39, 619–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmalbach, I.; Schmalbach, B.; Aghababa, A.; Brand, R.; Chang, Y.; Ciftci, M.C.; Elsangedy, H.; Gavira, J.F.; Huang, Z.; Kristjansdottir, H.; et al. Cross-cultural validation of the profile of mood scale: Evaluation of the psychometric properties of short screening versions. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauru, K.; Lehvavirta, S.; Korpela, K.; Kotze, D.J. Closure of view to the urban matrix has positive effects on perceived restorativeness in urban forests in Helsinki, Finland. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2012, 107, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peschardt, K.K.; Stigsdotter, U.K. Associations between park characteristics and perceived restorativeness of small public urban green spaces. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 112, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Rodiek, S.; Wu, C.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y. Stress recovery and restorative effects of viewing different urban park scenes in Shanghai, China. Urban Urban Gree 2016, 15, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.; Evans, G.W.; Jamner, L.D.; Davis, D.S.; Gärling, T. Tracking restoration in natural and urban field settings. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitagliano, L.A.; Wester, K.L.; Jones, C.T.; Wyrick, D.L.; Vermeesch, A.L. Group Nature-Based Mindfulness Interventions: Nature-Based Mindfulness Training for College Students with Anxiety. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Z.M.; Zhang, R.Y.; Dong, Y.; Liang, Z.H. A Study on the Relationship between Campus Environment and College Students’ Emotional Perception: A Case Study of Yuelu Mountain National University Science and Technology City. Buildings 2024, 14, 2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Zeng, C.C.; Bao, Z.Y.; Jin, H.X. The therapeutic look up: Stress reduction and attention restoration vary according to the sky-leaf-trunk (SLT) ratio in canopy landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 234, 104730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehaffy, M.W.; Salingaros, N.A.; Lavdas, A.A. The “Modern” Campus: Case Study in (Un)Sustainable Urbanism. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohly, H.; White, M.P.; Wheeler, B.W.; Bethel, A.; Ukoumunne, O.C.; Nikolaou, V.; Garside, R. Attention Restoration Theory: A systematic review of the attention restoration potential of exposure to natural environments. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part B 2016, 19, 305–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.S.; Xu, Y.Q.; Yang, X.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, P.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, K. Urban cultural heritage is mentally restorative: An experimental study based on multiple psychophysiological measures. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1132052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Y.; Luo, J.J.; Deng, T.M.; Tian, J.W.; Wang, H.C. Exploring perceived restoration, landscape perception, and place attachment in historical districts: Insights from diverse visitors. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1156207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Luo, S.X.; Furuya, K.; Kagawa, T.; Yang, M.A. A Preferred Road to Mental Restoration in the Chinese Classical Garden. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scrima, F.; Nonnis, M.; Mura, A.L.; Foddai, E.; Rioux, L.; Fornara, F. Changing the “Meaning of Place” Within a Hospital: The Impact of Establishing an Art Gallery on Esthetic Experience, Restorativeness, Affective Commitment, and Work Engagement of Healthcare Personnel. Environ. Behav. 2023, 55, 735–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraskevopoulou, A.; Klados, A.; Malesios, C. Historical Public Parks: Investigating Contemporary Visitor Needs. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevzati, F.; Veldi, M.; Kuelvik, M.; Bell, S. Analysis of Landscape Character Assessment and Cultural Ecosystem Services Evaluation Frameworks for Peri-Urban Landscape Planning: A Case Study of Harku Municipality, Estonia. Land 2023, 12, 1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southon, G.E.; Jorgensen, A.; Dunnett, N.; Hoyle, H.; Evans, K.L. Perceived species-richness in urban green spaces: Cues, accuracy and well-being impacts. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 172, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.Y.; Xiao, J.; Wan, Z. From Hongkew Ghetto to Shanghai Ark: Rethinking representation in the (re)making of affective atmosphere during cultural regeneration. Geoforum 2024, 152, 104012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabassum, R.R.; Park, J. Development of a Building Evaluation Framework for Biophilic Design in Architecture. Buildings 2024, 14, 3254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, M.G.; Soro, A.; Brown, R.A.; Harman, J.; Yigitcanlar, T. Augmenting Community Engagement in City 4.0: Considerations for Digital Agency in Urban Public Space. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.Y.; Geng, T. Healing Spaces Improve the Well-Being of Older Adults: A Systematic Analysis. Buildings 2024, 14, 2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.; Qiu, L.; Esposito, G.; Mai, K.P.; Tam, K.P.; Cui, J. Nature in virtual reality improves mood and reduces stress: Evidence from young adults and senior citizens. Virtual Real. 2023, 27, 3285–3300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browning, M.; Shin, S.; Drong, G.; McAnirlin, O.; Gagnon, R.J.; Ranganathan, S.; Sindelar, K.; Hoptman, D.; Bratman, G.N.; Yuan, S.; et al. Daily exposure to virtual nature reduces symptoms of anxiety in college students. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onecha, B.; Cornadó, C.; Morros, J.; Pons, O. New Approach to Design and Assess Metaverse Environments for Improving Learning Processes in Higher Education: The Case of Architectural Construction and Rehabilitation. Buildings 2023, 13, 1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Metric | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GVI (%) | 12.1 ± 3.28 a | 84.1 ± 2.95 b | 26.8 ± 5.65 a | 20.45 ± 4.29 a |

| Condition | Mean (ms) | SD (ms) |

|---|---|---|

| Office | 55 | 23 |

| Pre-walk (Standard Chain Coffee Shop) | 52 | 32 |

| Post-walk (Standard Chain Coffee Shop) | 54 | 25 |

| Pre-walk (Independent Coffee Shop) | 58 | 30 |

| Post-walk (Independent Coffee Shop) | 64 | 28 |

| Condition | Mean (ms) | SD (ms) |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-walk (Independent Coffee Shop) | 58 | 39 |

| Post-walk (Independent Coffee Shop) | 64 | 28 |

| Pre-walk (Wetland Park) | 56 | 27 |

| Post-walk (Wetland Park) | 64 | 24 |

| Condition | Mean (ms) | SD (ms) |

|---|---|---|

| Post-walk (Campus Cultural Gift Shop) | 64 | 28 |

| Pre-walk (Standard Chain Coffee Shop) | 52 | 32 |

| Post-walk (Standard Chain Coffee Shop) | 54 | 25 |

| Pre-walk (Wetland Park) | 56 | 27 |

| Post-walk (Wetland Park) | 64 | 24 |

| Pre-walk (Independent Coffee Shop) | 58 | 39 |

| Post-walk (Independent Coffee Shop) | 64 | 28 |

| Variable POMS | Variable Environment | Mean | CL Low 95% | CL High 95% | Standard Deviation | P (t-Test Dependent Samples) | ES (Hg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tension-Anxiety | P1 | 7.97 | 7.14 | 8.80 | 2.35 | ||

| P2 | 7.00 | 6.40 | 7.59 | 1.70 | 0.0452 | 0.15 | |

| P3 | 6.81 | 6.26 | 7.33 | 1.63 | 0.0078 | 0.18 | |

| P4 | 6.84 | 6.33 | 7.35 | 1.55 | 0.0198 | 0.18 | |

| Depression-Dejection | P1 | 14.22 | 12.82 | 15.62 | 4.09 | ||

| P2 | 12.44 | 11.64 | 13.23 | 2.28 | 0.0351 | 0.24 | |

| P3 | 12.37 | 11.58 | 13.17 | 2.44 | 0.0134 | 0.25 | |

| P4 | 12.31 | 11.67 | 12.95 | 1.94 | 0.0135 | 0.26 | |

| Anger-Hostility | P1 | 20.77 | 19.03 | 22.5 | 4.99 | ||

| P2 | 18.73 | 17.77 | 19.69 | 2.75 | 0.0417 | 0.25 | |

| P3 | 18.78 | 17.51 | 20.04 | 3.90 | 0.0387 | 0.23 | |

| P4 | 18.42 | 17.73 | 19.10 | 2.08 | 0.0121 | 0.30 | |

| Fatigue-Inertia | P1 | 26.6 | 24.26 | 28.93 | 6.80 | ||

| P2 | 23.73 | 22.45 | 25.01 | 3.67 | 0.0437 | 0.30 | |

| P3 | 23.83 | 22.23 | 25.43 | 4.94 | 0.0347 | 0.27 | |

| P4 | 23.52 | 22.31 | 24.74 | 3.69 | 0.0225 | 0.32 | |

| Confusion-Bewilderment | P1 | 7.62 | 6.80 | 8.44 | 2.34 | ||

| P2 | 6.17 | 5.58 | 6.77 | 1.71 | 0.0068 | 0.23 | |

| P3 | 6.45 | 5.84 | 7.07 | 1.9 | 0.0277 | 0.18 | |

| P4 | 6.68 | 6.11 | 7.25 | 1.72 | 0.0335 | 0.15 | |

| Vigor-Activity | P1 | 16.34 | 14.58 | 18.10 | 5.01 | ||

| P2 | 19.67 | 17.75 | 21.6 | 5.53 | 0.0187 | 0.36 | |

| P3 | 19.00 | 16.16 | 19.99 | 5.91 | 0.2532 | 0.18 | |

| P4 | 18.08 | 17.18 | 20.81 | 5.53 | 0.1450 | 0.19 | |

| Total POMS | P1 | 60.84 | 53.25 | 68.45 | 21.94 | ||

| P2 | 48.41 | 43.27 | 53.54 | 14.76 | 0.0413 | 0.47 | |

| P3 | 50.08 | 44.58 | 55.59 | 13.36 | 0.1376 | 0.41 | |

| P4 | 49.55 | 44.91 | 54.2 | 15.84 | 0.1809 | 0.41 |

| POMS | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRS | Tension | Depression | Anger | Fatigue | Confusion | Vigor | POMS | |

| Fascination | Difference | −0.290 | −0.366 | −0.367 | −0.453 | −0.427 | 0.477 | −0.555 |

| p-value | 0.140 | 0.072 | 0.072 | 0.033 | 0.042 | 0.000 | 0.012 | |

| Being away | Difference | −0.062 | −0.232 | −0.236 | −0.284 | −0.371 | 0.426 | −0.437 |

| p-value | 0.724 | 0.225 | 0.218 | 0.147 | 0.069 | 0.002 | 0.038 | |

| Compatibility | Difference | −0.220 | −0.258 | −0.271 | −0.408 | −0.479 | 0.602 | −0.567 |

| p-value | 0.246 | 0.182 | 0.164 | 0.049 | 0.026 | 0.000 | 0.011 | |

| Extent | Difference | −0.240 | −0.307 | −0.320 | −0.316 | −0.417 | 0.606 | −0.555 |

| p-value | 0.211 | 0.121 | 0.108 | 0.113 | 0.046 | 0.000 | 0.013 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhong, C.; Zhang, R.; Lu, S.; Zeng, H.; Gao, W. Can Historical Environments Rival Natural Environments? An Empirical Study on the Impact of Campus Environment Types on College Students’ Mental Health. Buildings 2025, 15, 2163. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15132163

Zhong C, Zhang R, Lu S, Zeng H, Gao W. Can Historical Environments Rival Natural Environments? An Empirical Study on the Impact of Campus Environment Types on College Students’ Mental Health. Buildings. 2025; 15(13):2163. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15132163

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhong, Chuqi, Ruiqi Zhang, Shaoying Lu, Hao Zeng, and Wei Gao. 2025. "Can Historical Environments Rival Natural Environments? An Empirical Study on the Impact of Campus Environment Types on College Students’ Mental Health" Buildings 15, no. 13: 2163. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15132163

APA StyleZhong, C., Zhang, R., Lu, S., Zeng, H., & Gao, W. (2025). Can Historical Environments Rival Natural Environments? An Empirical Study on the Impact of Campus Environment Types on College Students’ Mental Health. Buildings, 15(13), 2163. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15132163