Abstract

Effective asset management in the architecture, engineering, and construction/facilities management (AEC/FM) industry is crucial for improving asset performance and lifespan, as well as reducing downtimes and maintenance costs. Current asset management practices mostly rely on outdated paper-based approaches that are prone to data loss, security attacks, and missing information. Emerging technologies, such as digital twins, are being proposed to solve existing asset management problems in the AEC industry. However, the industry perspective is often missing in the evaluation of such technology-led approaches regarding actual applications and implementation challenges. This study seeks to understand the potential of digital twins in solving current asset management issues and challenges within the United Arab Emirates (UAE) context. To achieve this aim, structured interviews were conducted with 14 industry experts to capture their understanding of current digital technologies and existing issues in asset management. The findings of this study underscore the transformative potential of digital twins as a tool for optimizing asset performance and decision-making throughout the asset lifecycle.

1. Introduction

Technology is rapidly transforming every aspect of human life. In the past decade, technological advances and digitalization have revolutionized the delivery of healthcare, transportation, education, governance, and construction services [1,2]. Digitalization involves automating, streamlining, and enhancing business processes with advanced information technology [3]. It has leveraged the emergence of technologies like Artificial Intelligence (AI), machine learning, the Internet of Things (IoT), cloud computing, blockchain, and big data analytics. In the architectural, engineering, and construction (AEC) industry, digitalization enables better visualization, optimization, and management throughout all project phases, from design to construction and operation [4].

Asset management (AM) is a crucial phase of construction projects, and it is responsible for the operation and maintenance of built facilities. It accounts for the majority of costs and carbon emissions, necessitating accurate as-built information to optimize performance and sustainability. Traditionally, document-based AM practices are difficult to access, prone to inaccuracies [5], and time-consuming [6]. Improvements in AM practices can enhance asset management [7], reduce operation and management costs, and extend the lifespan of facilities [8]. Additionally, these improvements can lead to increased energy efficiency, improved compliance with regulatory standards, and enhanced occupant satisfaction through more reliable and responsive maintenance services. This has led to a global push for digitalizing AM to revolutionize the operation and management practices of built assets.

In the United Arab Emirates (UAE), rapid economic growth and ambitious infrastructure projects have increased the importance of effective AM. However, AM practices in the UAE remain largely document-oriented and face several shortcomings. These include reactive maintenance practices [9], limited access to real-time asset data [10], insufficient predictive maintenance capabilities [11], challenges in achieving sustainability goals [12], and difficulties in retrieving relevant information from locked documents when needed [13]. These challenges are not unique to the UAE but are shared globally, prompting researchers to use technology-driven solutions for improving asset and facility management (FM) practices in the AEC industry.

One such technology-led solution is building information modeling (BIM), which provides digital information in the AEC/FM industry throughout a project’s lifecycle. BIM evolves during different phases to meet the specific needs of project management, risk management, and facility management [14]. Furthermore, the concept of digital twins (DTs) has recently emerged, offering bi-directional information changes between physical assets and a virtual model providing numerous opportunities for informed decision-making [15]. However, the development and applications of DTs are still experimental and require further investigation, especially regarding their role in digitalizing AM practices in built environment projects from an industry perspective.

Much of the literature on DTs within the AEC/FM industry focuses on technical development, implementation, and theoretical potential. However, there is a notable gap in understanding how DTs can be practically applied to address the real-world challenges faced by the AEC/FM sector. This gap is particularly significant in regions like the UAE, where AM practices are still heavily document-based. Therefore, there is a critical need for research that focuses on the perspectives of industry experts. This will help better understand the practical opportunities and barriers to adopting DTs in AM and facility management (FM) practices. This study seeks to answer the following research question: “What do industry experts think about DTs in terms of their potential and challenges for the AM/FM industry, and how are they different from BIM?” By focusing on the perspectives of industry experts, this study aims to bridge the gap between the technical development of DTs and their practical implementation in real-world asset management practices. The main contributions of this work are as follows.

- This paper presents findings from structured interviews with fourteen industry experts to uncover key issues in traditional AM/FM approaches, examine the potential of BIM and DT technologies, and identify major challenges hindering their adoption in the facility management industry.

- We highlight critical shortcomings in current documentation practices, data security, and manual data handling, offering insights into the operational inefficiencies affecting the sector.

- We evaluate the level of awareness and readiness regarding BIM and DT technologies, emphasizing the need for greater training and adoption.

- We offer a comprehensive analysis of the challenges faced by FM professionals and demonstrate how DT technologies can be leveraged to address these issues, ultimately enhancing the efficiency and effectiveness of facility management systems.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows: Section 2 overviews the related work. The interview methodology and questionnaire are explained in Section 3. Section 4 analyzes the interview responses. Recommendations for efficient and effective AM are provided in Section 5. The paper concludes with research directions in Section 6.

2. Related Work

Several works in the literature have focused on the applicability of DTs within the AEC/FM industry [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. Camposano et al. [15] conducted a qualitative study to explore the familiarity and understanding of DTs among Finnish AEC/FM practitioners. The study involved semi-structured interviews with 28 participants, including project managers, C-level executives, and practitioners holding equivalent roles spanning 2018 and 2019. Contrary to possessing a precise understanding of the intricacies of DTs, the participants demonstrated a familiarity with the technology’s broader vision and implementation within organizations. In addition, there was a lack of consensus among AEC/FM practitioners regarding a standardized definition of DTs. In a comprehensive bibliometric review, Ozturk [16] scrutinized the applicability and challenges associated with DTs in the AEC/FM industry. Analyzing a total of 151 articles, the author identified five primary areas of focus in DT implementation within the AEC/FM sector: (1) building lifecycle management; (2) the utilization of virtual-based information; (3) the integration of virtual and physical building aspects; (4) predictive management based on information; and (5) production integrated with information.

Marco et al. [17] explored the role of DTs in asset management decision-making. They identified that the decision-making process involves four principles: lifecycle orientation, system orientation, risk orientation, and asset-centric orientation. In addition, they highlighted two aspects: asset lifecycle and asset hierarchical control level. The authors concluded that proper data/information management is crucial in the decision-making process for asset management, and DTs can bridge the current gap by integrating data management with the asset lifecycle. Macchi et al. [18] emphasized the significance of DTs in asset-related decision-making through use cases categorized by asset control levels and lifecycle phases. The authors highlighted that DT data can be utilized for asset configuration, planning, commissioning, condition monitoring, and health assessment. James and Ajith [19] detailed the design and development of DTs using a BIM-based approach, creating an asset information model (AIM) for effective asset management. The AIM involves classifying assets within a BIM model, developing a relational database, and linking BIM models to the database in a federated model. Their approach was illustrated through a case study at the West Cambridge campus. Abdelmoti and Shafiq [20] performed a systematic review to explore the application of DTs for asset management in the AEC/FM industry. The authors revealed that DT creation procedures are in their early stages, emphasizing potential applications for asset management throughout the asset’s lifespan. Furthermore, they categorized the use of DTs into five sections: (1) DT technology, (2) DT creation, (3) maintenance and restoration of heritage assets, (4) asset management, and (5) sustainability retrofits.

Arisekola and Madson [21] employed social network analysis to examine research articles focusing on DT applications in civil engineering asset management, identifying key research trends and central topics. They found that real-time data and decision-making were the areas with the most emphasis, while DT architecture and data integration lacked standardization. The study highlights the need for unified frameworks, enhanced interoperability, and improved quality assurance of sensor data. Hakimi et al. [22] performed a bibliometric analysis of DT-enabled FM, identifying key focus areas. These areas include AI-based predictive maintenance, real-time cyber–physical integration, digital FM, as-built/as-is modeling, intelligent prognostics and health management, asset lifecycle management, and semantic interoperability. The study also highlighted existing gaps, particularly in the integration of augmented reality for FM, AI-driven prognostics during the operation and maintenance phase, and intelligent infrastructure monitoring. Tavakoli et al. [23] developed a data provenance model on a blockchain-based DT to enhance predictive asset management in building facilities. The authors use a qualitative approach, beginning with a scoping review to establish theoretical foundations, followed by semi-structured interviews with industry experts to gain practical insights. Based on these findings, a case study was conducted in an office building to assess the application of the proposed model. The model aims to enhance data reliability, traceability, and informed decision-making by leveraging blockchain’s transparency and immutability within the DT framework. Vieira et al. [24] introduced a value-based analysis method to evaluate DT opportunities in asset management. Validated through three case studies, the method provides a structured approach to articulate the value of DTs in infrastructure asset management.

In summary, the existing literature provides a solid foundation for understanding the theoretical potential and diverse applications of DTs within the AEC/FM industry. However, these works often emphasize conceptual frameworks, technological integration, or high-level use cases without deeply engaging with the day-to-day realities and challenges faced by FM practitioners. Key issues such as poor documentation practices, fragmented data management, limited awareness, and the lack of adequate training remain underexplored. To address this gap, our study complements prior research by presenting findings from structured interviews with FM professionals. These insights reveal operational inefficiencies, practical barriers to adoption, and the current level of readiness regarding BIM and DT technologies. In doing so, this work advances the ongoing discourse by contributing a practitioner-oriented perspective that bridges the gap between theoretical promise and real-world implementation in the FM sector.

3. Methodology

The research conducted in this study is based on the findings from structured interviews with 14 asset management professionals, aiming to understand the current state of asset management practices. It uncovers inherent challenges in traditional methods and assesses the willingness of FM personnel to adopt modern technological solutions. Additionally, we examine the potential of DTs to address deficiencies in existing asset management practices, particularly within the context of Abu Dhabi, UAE. This section explains the methodology adopted for conducting interviews. In particular, it discusses the employed research tools, interview guidelines, and the questionnaire.

3.1. Research Tools

Our methodology employs structured interviews to identify the current asset management approaches in the AEC/FM industry, extract prevailing issues, and assess the viability of incorporating DTs to mitigate those issues. Interviews are considered over surveys due to the intricate nature of asset management practices and the need for comprehensive insights. Interviews facilitate a profound exploration of participants’ experiences, perspectives, and insights regarding asset management practices, enabling in-depth exploration. This aligns with the research’s exploratory nature, enabling a thorough examination of weaknesses and challenges [25]. Furthermore, interviews provide direct access to industry experts, practitioners, and stakeholders with specialized knowledge and practical experience in asset management within the UAE. These experts offer valuable insights that might not be captured through other research methods, such as surveys [25]. In addition, interviews facilitate the collection of qualitative data, ensuring the research captures the topic’s quantitative and qualitative dimensions [25].

Our proposed methodology uses structured interviews. In contrast to unstructured or semi-structured interviews, where questions may vary and evolve during the conversation, structured interviews are characterized by a systematic and predefined set of questions. These questions are posed to participants in a consistent and standardized manner [26]. The selection of structured interviews is to have a standardized and reliable data collection approach and easy comparison of responses across participants for systematic data analysis [27]. This comparability is particularly valuable for identifying patterns and common themes related to weaknesses in asset management practices. The rationale for selecting structured interviews for this research is grounded in the following considerations.

- Reduced bias risk: The risk of bias in data collection is diminished by posing the same questions consistently to all participants.

- Diverse job titles: Conducting interviews with individuals holding various job titles, ranging from technicians to managers (site to office), aids in comprehending challenges at their foundational levels.

- First-hand insight: To identify primary challenges FM professionals face through direct interactions with experts.

- In-depth exploration: Offering experts the opportunity to elaborate extensively on issues raised by the researcher and introduce novel topics relevant to the subject.

- Solution proposals: Allowing participants the space to propose solutions from their unique perspectives.

We use IBM SPSS Statistics software version 29 to manage and analyze the interview responses as this software is capable of quantitative data analysis, descriptive statistics, and data visualization [28]. Structured interviews, coupled with IBM SPSS Statistics for data analysis, enable a rigorous examination of asset management practices in the UAE, focusing on Abu Dhabi. The study also explores the potential integration of DTs to address identified weaknesses.

3.2. Interview Guidelines

Before commencing the interviews, it was essential to have a comprehensive understanding of the characteristics of a robust qualitative interview. The fundamental concepts guiding the interviews, as outlined by [29], were as follows.

- Value: About the significance of the interview and the interviewees’ expressions.

- Trust: Ensuring ethical research through objectivity, accuracy, and honesty.

- Meaning: The intended meaning that the interviewer seeks to convey.

- Wording: The formulation of questions in the interview, with the recognition that concise interviewer questions and extensive subject responses contribute to the effectiveness of the interview.

The guidelines that should be followed to conduct structured interviews are stated below.

- The interview should have a natural flow of conversation and be rich in detail.

- The priority is establishing a comfortable and open environment for the participants, emphasizing active listening rather than mere talking.

- Participants should be allowed to choose between face-to-face or online meetings (via Zoom or Microsoft Teams) based on their preference.

- The interview sessions should commence by explaining the aim and purpose of the study.

- The number of questions should be minimized without compromising the acquisition of crucial information to maintain the interviewees’ engagement and prevent boredom.

- Sensitive questions should be avoided.

- Neutrality should be maintained while seeking specific details.

3.3. Candidate Selection

The selection of candidates for interview in our methodology is based on convenience with three inclusion criteria: (1) more than one year of experience in the FM industry in the emirate of Abu Dhabi, (2) proficiency in English, and (3) a diverse range of positions. Candidates are chosen to encompass diverse facets of the facility management industry, considering their backgrounds and years of experience.

The candidate selection process began by compiling a list of facility management companies overseeing malls, university campuses, offices, and housing projects. After sending numerous emails and, in some instances, making phone calls to these entities, participants were successfully recruited. This method proved effective even in engaging elusive managers. Individuals of both genders, spanning various ages and possessing diverse academic degrees, were invited to participate in the study to ensure a broad spectrum of backgrounds and viewpoints. This inclusive approach aimed to capture perspectives from newcomers to the market and seasoned professionals from the older generation.

Fourteen individuals were shortlisted and contacted, with interview dates arranged based on mutual convenience. Eight interviews were conducted face-to-face, while six others were via Zoom meetings, accommodating the participants’ comfort preferences. At the outset of each session, a transcript was presented, seeking consent for the anonymous use of participants’ feedback. Each interview lasted approximately 20 min and was meticulously recorded. Transcripts of the discussions were generated from the recorded sessions.

3.4. Interview Questions

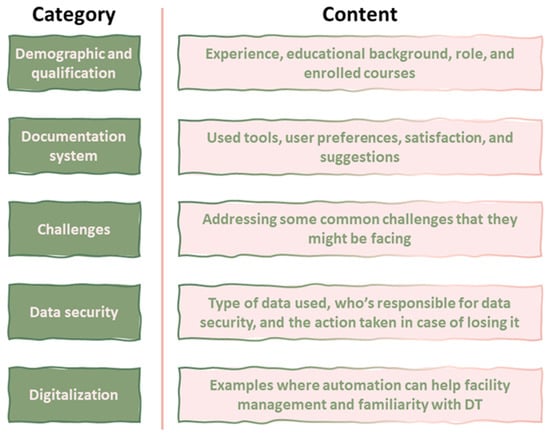

Various dimensions of AM/FM responsibilities were examined in these interviews to assess the influence of digitalization on crucial facets and context-specific factors. The interview questions encompassed five primary categories. Figure 1 illustrates these categories along with their contents.

Figure 1.

Interview questions categories and their contents.

The interview framework comprised 22 questions, as outlined in Table 1. The initial five questions (Q1–Q5) aimed to gather demographic information, including job title, education, and experience. Q6 was designed to pinpoint the prevailing tools and software in the AM/FM industry in the UAE. Q7–Q9 delved into perspectives on document types, actionability, and employee satisfaction, exploring the need for potential changes. Q10 sought employee input on speeding up locating specific documents. Questions Q11–Q16 explored challenges and hurdles workers face in facilities management, identifying diverse problem-solving approaches companies employ to uncover innovative methods. Q17 aimed to ascertain the type of information exchanged in the process, while Q18–Q20 focused on measures taken to ensure the safety of exchanged information. Q21 directly inquired about participants’ awareness of BIM or DT technologies. The final question, Q22, held particular significance, prompting participants to contemplate an example illustrating how automation could enhance facility management tasks.

Table 1.

Structured interview questions.

4. Analysis of Responses

This section unveils the recurring themes in the participants’ narratives, discerns consistent patterns, and comprehends challenges in the current asset management approaches.

4.1. Demographic and Qualifications

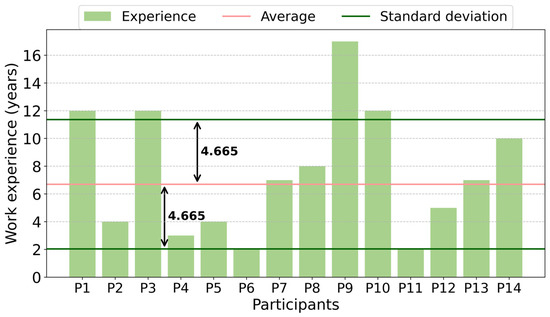

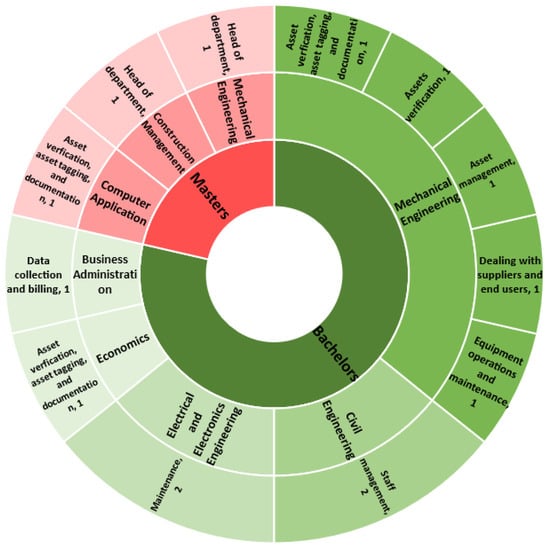

As depicted in Figure 2, the interviewees’ experience is diverse, with a mean experience of 6.7 years. These varying experience levels offer valuable insights into generational disparities and the impact of accumulated experiences on an employee’s adaptability to changes. To encompass this diversity, we intentionally selected participants with a spectrum of experience, ranging from a minimum of one year to a maximum of seventeen years. Furthermore, these interviewees had diverse educational backgrounds. Out of 14 candidates, 3 held a master’s degree and two held positions as heads of departments (Figure 3). The majority of participants had a background in mechanical engineering, with four individuals holding a diploma in mechanical engineering, with one having a master’s degree in the same field and one serving as a mechanical technician. This subgroup constitutes nearly 43% of the total participants. Following closely is the field of civil engineering, represented by two individuals with a diploma and one with a master’s degree, making up approximately 21.4% of the participants. The remaining participants have diverse educational backgrounds, including business administration, economics, and electrical engineering. Their roles encompassed various responsibilities, including equipment operations, supplier interactions, asset verification, asset tagging, documentation, staff management, and basic maintenance.

Figure 2.

Responses to Q1—participants’ experiences.

Figure 3.

Responses to Q2 and Q3—participants’ educational qualifications and their roles.

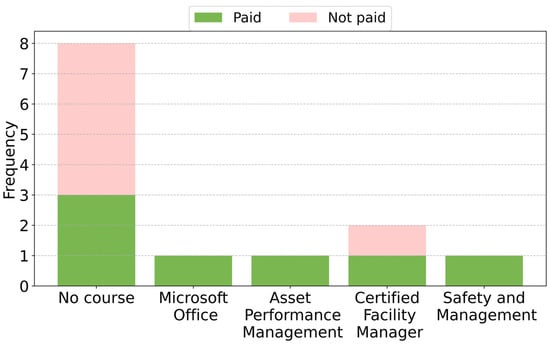

Given the increasing demand for ongoing learning in the professional sphere, our analysis aimed to assess the participants’ uptake of professional development opportunities, particularly in FM. According to LinkedIn’s 2019 Workplace Learning Report, 74% of employees expressed a keen interest in enhancing their skills during their free time [30]. Consequently, we investigated whether participants had pursued courses related to AM/FM, the nature of these courses, and the sponsorship details. The responses reveal that 57% of companies were inclined to cover course expenses for their employees. Notably, among companies that did not provide financial support, a substantial 85.7% of workers did not partake in any courses, in contrast to just 28.6% of employees in companies offering financial assistance. Most participants did enroll in various courses, covering topics such as Microsoft Office, asset performance management, safety, and certified facility manager (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Responses to Q4 and Q5—paid/non-paid courses related to facility management.

4.2. Documentation System

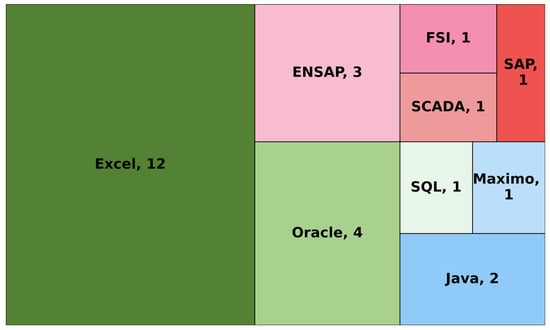

Documentation of asset information is a crucial aspect of how asset data are stored, retrieved, accessed, and maintained. Investigating the documentation system of asset management practices is essential to understand the related challenges, such as difficulties in accessing information, inaccuracies, and time-consuming processes. Additionally, the maintenance of comprehensive documentation serves to pinpoint areas in need of improvement, ultimately facilitating quality enhancement and process optimization. Based on the responses to Q6, which investigates the tools/software used for documentation, Microsoft Excel emerges as the most prevalent choice for documentation, constituting 46% of the mentioned software (Figure 5). Following closely is Oracle at 15.4%, ENSAP at 11.5%, and Java at 7.7%. Several other tools were mentioned once, including SQL, Maximo, SAP, FSI, and SCADA.

Figure 5.

Responses to Q6—software used for task management.

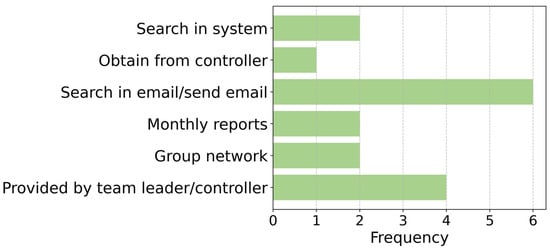

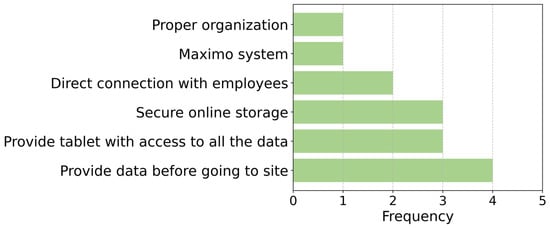

Furthermore, in responding to Q7, 85.7% of participants opted for digital documentation, while only two favored paperwork. Notably, these two individuals were the only technicians in the study. They justified their preference by their constant mobility between facilities, making paper documents more suitable for their work, as opposed to returning to the office for digital updates. All participants unanimously affirmed dealing with documents daily. A significant portion stated their reliance on email (35.3%) or team leaders (23.5%) for necessary documents, as illustrated in Figure 6. The least common method was obtaining documents from the controller, representing only 5.9%. Satisfaction with the current storage of FM documents varied, with 42.8% expressing contentment, 42.8% dissatisfaction, and only 14.4% partial satisfaction. Concerning proposals to expedite document access, the most common suggestion (28.6%) was to assign a specific party to provide necessary data for the site or facility, eliminating the need for extensive searching. The second proposal (21.4%), suggested by technicians and a civil engineer, involved providing a smart tablet with internet access for system accessibility anywhere or secure online storage. Noteworthy proposals included direct employee connections, implementing a Maximo system, and enhancing organizational structure, as presented in Figure 7. In response to Q9, regarding satisfaction with the current storage of AM/FM documents, 57.1% expressed dissatisfaction, 14.3% were partially content, and 28.6% were satisfied with the existing storage methods.

Figure 6.

Responses to Q8—methods used for document query.

Figure 7.

Responses to Q10—ways to speed up document query.

4.3. Challenges

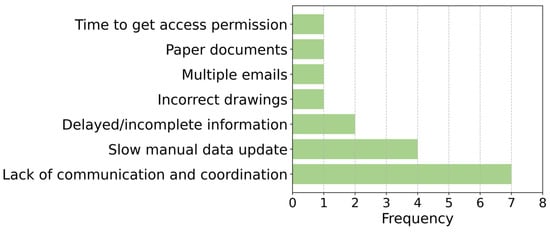

By directly probing the challenges within the facility management process, we gleaned insights into the prevalent obstacles impeding its efficiency. As depicted in Figure 8, various challenges were discerned, encompassing issues such as struggles with access permissions, handling paper documents, navigating through numerous emails, and encountering inaccuracies in drawings. Notably, 41.2% of the identified challenges were attributed to deficiencies in communication and coordination. This high proportion underscores a systemic issue in how information flows across departments and stakeholders. Ineffective communication can lead to redundant efforts, misinterpretation of tasks, and delays in operations, especially in large-scale or multi-site facilities. The next significant challenge (responded by 23.5% of participants) pertains to sluggish manual data updates. This manual approach is not only time-consuming but also error-prone, limiting the ability to maintain real-time, accurate operational data. In addition, 11.8% of challenges were linked to delays in obtaining or incomplete information. Furthermore, a substantial 85.8% of participants manually updated information and data, indicating minimal automation or digitization in current workflows. Only 7.1% utilized scanners for this purpose, and an equivalent percentage had their information entered by software engineers.

Figure 8.

Responses to Q11—challenges faced in managing facility management information.

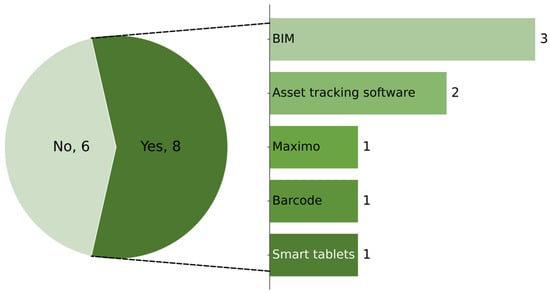

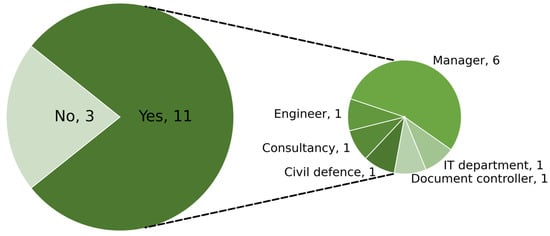

As shown in Figure 9, 57.1% of the participants affirmed awareness about digital solutions, with 37.5% specifically mentioning BIM and 25% referencing asset tracking software. Interestingly, 42.9% admitted being unaware of any methods used outside their organization. Despite the moderate awareness levels, the heavy reliance on manual updates and low use of automation (as shown in Figure 8) highlights a technology adoption gap, possibly driven by organizational resistance, lack of training, or budget constraints. Figure 10 provides further insights into data access and control protocols. 78.6% of participants affirmed the requirement for a permit to access or update data, which suggests a strong emphasis on data governance and information security. Interestingly, 27.3% of respondents specified the need for a permit only in certain exceptional cases, such as high-risk areas. In contrast, a smaller percentage, 21.4%, asserted that they do not require permission. The breakdown of entities responsible for granting permits adds another layer of complexity. A majority (54.5%) of permits are sought from department managers, making them central decision-makers in information control. In other instances, permissions are sought from various entities such as civil defense, the IT department, document controller, consultancy, or the engineer in the case of technicians. This fragmented authorization system can lead to delays, inconsistencies in decision-making, and confusion regarding roles and responsibilities. It also reflects a potential lack of a centralized access policy or digital role-based access control systems.

Figure 9.

Responses to Q13—awareness regarding innovative facility management solutions that are not being used in a participant’s organization.

Figure 10.

Responses to Q15—permission for data update.

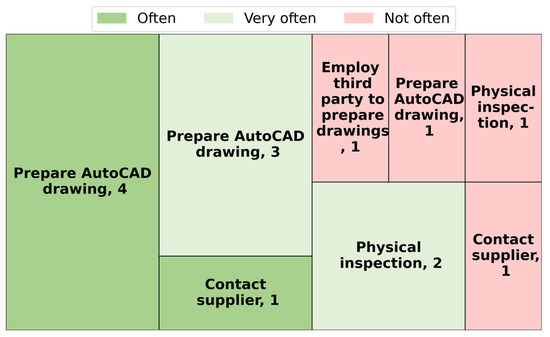

Drawing from the participants’ experiences, it appears that 71.4% have encountered the issue of drawings not aligning with reality. Among them, 50% believe this discrepancy occurs frequently, while 28.5% have not faced such a situation and consider it infrequent. Regarding the measures taken in such cases, participants mentioned contacting the supplier, creating an AutoCAD drawing, or conducting a physical inspection (Figure 11). A significant 64.3% of participants emphasize the necessity of preparing AutoCAD drawings, while 21.4% believe that physical inspection suffices in most instances.

Figure 11.

Responses to Q14 and Q16—frequency of incorrect drawings and how to manage and deal with missing data.

4.4. Data Security

Creating, acquiring, storing, and exchanging data constitute integral aspects of any company’s operations. Safeguarding these data from internal and external threats, including corruption and unauthorized access, is crucial to avoid financial losses, reputation damage, and consumer trust erosion. Recognizing the significance of data security in facility management, the author aimed to delve into the nature of the data used. The goal was to identify the parties responsible for its security and understand the methods employed for its protection [31].

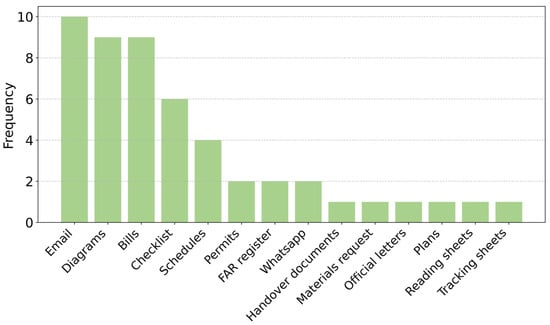

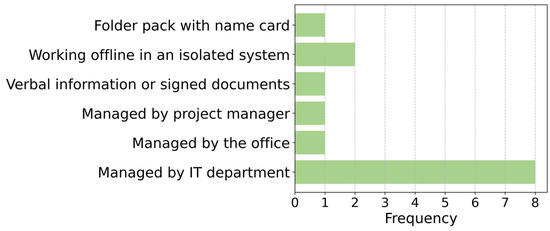

Participants were queried about the types of information utilized in facility management. The most prevalent response among participants was emails, with 71.4% mentioning it, representing 20% of the total (Figure 12). Following closely were diagrams and bills, cited by 64.3%, each accounting for 18% of the answers given. Information exchange tools such as checklists, schedules, permits, FAR registers, sheets, and WhatsApp group chats were also frequently mentioned. In contrast, handover documents, materials requests, official letters, and plans were mentioned only once, as illustrated in Figure 12. Regarding strategies for ensuring the security of collected data, most participants exhibited uncertainty or lack of confidence in their responses. Among those who highlighted email and WhatsApp as common data-sharing methods (representing 71.4% of participants), the responsibility for data protection was attributed to either the IT department or the project manager, as shown in Figure 13. A smaller percentage (14.3%) proposed that working offline in an isolated system might enhance data protection. Conversely, technicians suggested utilizing folders containing name cards, verbal information, or signed documents.

Figure 12.

Responses to Q17—types of information used for facility management.

Figure 13.

Responses to Q18—methods to ensure data security.

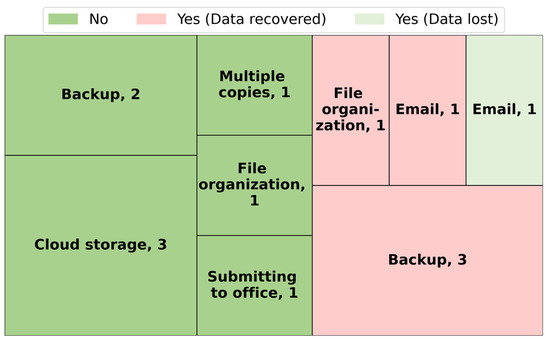

Regarding data loss, a majority, i.e., 57.1%, responded negatively, while 42.9% acknowledged experiencing data loss (Figure 14). Among those who encountered data loss, 83.3% successfully recovered the data with assistance from the IT department, while 16.7% could not. A total of 35.7% of participants suggested having a backup to reduce the risk of data loss. Additionally, 21.4% endorsed Cloud storage as a solution. A further 14.3% believed that using email to share information might mitigate the risk, reasoning that it would be stored there in the event of drive failure. Another 14.3% emphasized the efficacy of simply organizing files in safeguarding data. Some participants also proposed creating multiple copies of files or submitting collected data directly to the office during site work to minimize risks. The responses reveal that cloud storage users are less likely to experience data loss, and those who regularly create backups reduce the likelihood of data loss and find recovery a straightforward process. Email emerged as the sole case where participants faced challenges in data recovery.

Figure 14.

Responses to Q19 and Q20—data loss incidents and ways to mitigate the risk of data loss.

4.5. Building Model Information (BIM) and Digital Twins (DTs)

This section presents questions aimed at gauging participants’ awareness of BIM and DTs. It explores areas where FM professionals might seek development to harness the possibilities of digitization. The responses to Q9 revealed a pattern where individuals who expressed contentment or partial satisfaction with existing methods were unaware of BIM and DTs. Conversely, those familiar with these concepts were the ones who initially indicated dissatisfaction with current practices in their organizations. As depicted in Figure 15, 64.3% of participants lacked awareness of BIM or DTs. Among this group, 66.7% were satisfied or partially satisfied with current methods, while 33.3% were dissatisfied. Only a minor fraction, 7.1% of participants, demonstrated familiarity with BIM and DTs, while 28.6% were aware of the existence of BIM.

Figure 15.

Responses to Q9 and Q21—satisfaction with the current documentation approach and awareness regarding digital technologies.

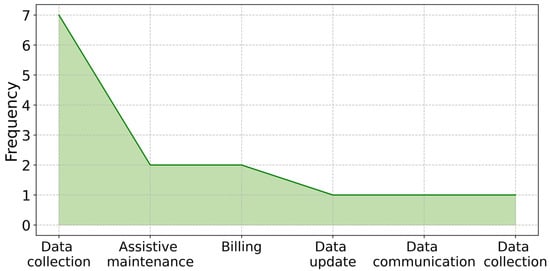

Participants were encouraged to take their time to contemplate the possibilities. A diverse array of intriguing responses emerged. Half of the participants expressed a desire to automate the data collection process from sites, highlighting the inefficiency of the current manual approach, which involves navigating, seeking approvals, and entering physically challenging locations. Meanwhile, 14.3% of respondents emphasized the challenges associated with manually collecting bills, storing them for extended periods, and comparing prices, citing the potential for human errors in this process. Another 14.3% identified the need for automation in preventive maintenance tasks. Some participants underscored that automating data updates and communication could free employees to channel their energy into other responsibilities, thereby saving time and effort, as depicted in Figure 16.

Figure 16.

Responses to Q22—application of automation in facility management.

5. Discussions and Recommendations

Examining current asset management practices within the UAE, particularly in the AEC/FM sector, exposes several significant weaknesses and challenges. An essential area requiring attention is the widespread use of outdated and basic tools/software for documentation. The imperative need is to replace these obsolete tools with more advanced solutions to save time and energy. Challenges in this domain encompass documentation management, data access difficulties, and information retrieval issues. Moreover, substantial obstacles exist in communication and coordination, manual data updates, and delays in obtaining crucial information. Discrepancies between project drawings and the actual physical reality emerge as a notable concern, potentially leading to operational inefficiencies. Beyond these challenges, evaluating data security measures for safeguarding sensitive information is crucial. Data protection from breaches and unauthorized access demands meticulous attention in asset management practices within the UAE. Addressing these weaknesses and challenges is pivotal for enhancing the overall effectiveness and efficiency of asset management in the AEC/FM sector in the UAE.

The interview findings revealed that most participants had limited awareness of digital technologies like BIM and DTs. However, a significant portion expressed a keen interest in incorporating automation to improve various aspects of facility management tasks, including data collection and maintenance. Additionally, challenges were identified in participants’ access to and efficient updating of facility management data due to manual processes, leading to delays caused by permissions and communication issues, inefficient data storage, and security concerns. It is worth noting that a diverse array of intriguing responses emerged during the interviews, reflecting the participants’ varying professional backgrounds, experiences, and levels of familiarity with digital technologies. This diversity enriched the findings by capturing a broad range of perspectives and challenges faced in the field. DTs emerged as a viable solution to address these challenges in asset management practices by offering real-time data updates, ensuring data privacy and security, and facilitating real-time decision-making. Based on the identified challenges and the potential benefits of DTs, recommendations and guidelines can be developed for organizations in the UAE. These recommendations include adopting real-time data monitoring through digital twins, enhancing data security through robust access controls, and centralizing data management to improve efficiency.

Table 2 presents a compilation of prevalent issues in the current AM/FM approaches and detailed descriptions of participants’ responses to interview questions. The table further delves into how DTs can offer solutions to these issues, facilitating the establishment of an efficient facility management system.

Table 2.

Challenges in traditional AM/FM approaches and how digital twins address them.

6. Conclusions

Asset management in construction projects is a critical phase responsible for the effective operation and maintenance of built assets. It accounts for substantial costs, carbon emissions, rework, and resource allocation. This paper presents a fresh perspective on existing challenges in current asset management practices, particularly within the context of the UAE. The research findings confirm that AM/FM practices in the UAE are heavily document-centric, facing inherent challenges such as delayed data updates, data privacy, data integrity, manual errors, missing information, delayed information retrieval, and inefficiency. The findings of this paper serve as a reminder of the urgent need for innovative solutions to address the challenges faced by asset-intensive organizations. This study recommends that DT technology has enormous potential to provide solutions to the existing challenges of AM/FM practices. By adopting the DT paradigm, organizations can overcome the limitations of traditional methods and unlock new possibilities for optimizing asset performance, reducing costs, enhancing sustainability, improving data accuracy, and facilitating real-time decision-making. While this study is based on a relatively small sample of respondents within the UAE, the structured methodology adopted offers a replicable framework that can be applied in broader geographic contexts and with larger participant groups. In the future, we aim to develop a DT-based asset management system to evaluate its impact and performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.A. and M.T.S.; data curation, A.M.A.; formal analysis, A.M.A.; funding acquisition, M.T.S. and M.M.A.K.; investigation, A.M.A.; methodology, A.M.A., M.T.S. and A.R.; project administration, M.T.S. and A.R.; validation, A.R.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.A.; writing—review and editing, M.T.S., A.R. and M.M.A.K.; supervision, M.T.S., A.R. and M.M.A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Afzal, M.; Shafiq, M.T. Evaluating 4D-BIM and VR for Effective Safety Communication and Training: A Case Study of Multilingual Construction Job-Site Crew. Buildings 2021, 11, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Jiang, Y.; Zhi, H.; Dong, Y.; Li, H.; Ma, S.; Wang, Y.; Dong, Q.; Shen, H.; Wang, Y. Artificial intelligence in healthcare: Past, present and future. Stroke Vasc. Neurol. 2017, 2, 230–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gobble, M.M. Digitalization, Digitization, and Innovation. Res.-Technol. Manag. 2018, 61, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaloul, W.S.; Liew, M.S.; Zawawi, N.A.W.A.; Mohammed, B.S. Industry Revolution IR 4.0: Future Opportunities and Challenges in Construction Industry. MATEC Web Conf. 2018, 203, 02010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarasoja, A.-L. Public Facilities Management Services in Local Government—International Experiences; Aalto University: Espoo, Finland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Chu, Z.; Song, H. Understanding the relation between BIM application behavior and sustainable construction: A case study in China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waheed, Z.; Fernie, S. Knowledge based facilities management. Facilities 2009, 27, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, I. Facility management as an emerging discipline. In Workplace Strategies and Facilities Management; Routledge: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Becerik-Gerber, B.; Jazizadeh, F.; Li, N.; Calis, G. Application Areas and Data Requirements for BIM-Enabled Facilities Management. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2012, 138, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawed, M.; Tilani, V.; Hamani, K. The role of facilities management in green retrofit of existing buildings in the United Arab Emirates. J. Facil. Manag. 2020, 18, 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosamo, H.H.; Imran, A.; Cardenas-Cartagena, J.; Svennevig, P.R.; Svidt, K.; Nielsen, H.K. A Review of the Digital Twin Technology in the AEC-FM Industry. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2022, 2022, 2185170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, B.N.; Khan, M.; Han, K. Towards sustainable smart cities: A review of trends, architectures, components, and open challenges in smart cities. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 38, 697–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmoti, A.M.; Shafiq, M.T.; Ur Rehman, M.S. Applications of Digital Twins for Asset Management in AEC/FM Industry—A Literature Review. In Proceedings of the ZEMCH 2021—8th Zero Energy Mass Custom Home International Conference, Proceedings 2021, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 26–28 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Chan, A.P.C.; Darko, A.; Chen, Z.; Li, D. Integrated applications of building information modeling and artificial intelligence techniques in the AEC/FM industry. Autom. Constr. 2022, 139, 104289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camposano, J.C.; Smolander, K.; Ruippo, T. Seven Metaphors to Understand Digital Twins of Built Assets. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 27167–27181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, G.B. Digital Twin Research in the AECO-FM Industry. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 40, 102730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouertani, M.Z.; Parlikad, A.K.; McFarlane, D. Asset information management: Research challenges. In Proceedings of the 2008 Second International Conference on Research Challenges in Information Science, Marrakech, Morocco, 3–6 June 2008; pp. 361–370. [Google Scholar]

- Macchi, M.; Roda, I.; Negri, E.; Fumagalli, L. Exploring the role of digital twin for asset lifecycle management. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2018, 51, 790–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaton, J.; Parlikad, A.K. Asset Information Model to support the adoption of a Digital Twin: West Cambridge case study. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2020, 53, 366–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.; Shafiq, M.T. Exploring Digital Twins Applications for Asset Management in the AEC/FM Industry. Preprints 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arisekola, K.; Madson, K. Digital twins for asset management: Social network analysis-based review. Autom. Constr. 2023, 150, 104833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakimi, O.; Liu, H.; Abudayyeh, O. Digital twin-enabled smart facility management: A bibliometric review. Front. Eng. Manag. 2024, 11, 32–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakoli, P.; Yitmen, I.; Sadri, H.; Taheri, A. Blockchain-based digital twin data provenance for predictive asset management in building facilities. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2024, 13, 4–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, J.; de Almeida, N.M.; Martins, J.P.; Patrício, H.; Morgado, J.G. Analysing the Value of Digital Twinning Opportunities in Infrastructure Asset Management. Infrastructures 2024, 9, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, P.M.; Lichtenfels, P.A.; Pursell, E.D. The structured interview: Additional studies and a meta-analysis. J. Occup. Psychol. 1989, 62, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, H.R.; Wutich, A.Y.; Ryan, G.W. Analyzing Qualitative Data: Systematic Approaches; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Campion, M.A.; Palmer, D.K.; Campion, J.E. A Review of Structure in the Selection Interview. Pers. Psychol. 1997, 50, 655–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallant, J. SPSS Survival Manual: A Step by Step Guide to Data Analysis Using IBM SPSS; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somekh, B.; Lewin, C. Research Methods in the Social Sciences, 1st ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Linkedin. 2019 Workplace Learning Report. Available online: https://learning.linkedin.com/content/dam/me/business/en-us/amp/learning-solutions/images/workplace-learning-report-2019/pdf/workplace-learning-report-2019.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- Denning, D.E.; Denning, P.J. Data Security. ACM Comput. Surv. 1979, 11, 227–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajavi, S.H.; Motlagh, N.H.; Jaribion, A.; Werner, L.C.; Holmstrom, J. Digital Twin: Vision, benefits, boundaries, and creation for buildings. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 147406–147419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamenko, D.; Kunnen, S.; Pluhnau, R.; Loibl, A.; Nagarajah, A. Review and comparison of the methods of designing the Digital Twin. Procedia CIRP 2020, 91, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliabue, L.C.; Cecconi, F.R.; Maltese, S.; Rinaldi, S.; Ciribini, A.L.C.; Flammini, A. Leveraging digital twin for sustainability assessment of an educational building. Sustainability 2021, 13, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Parlikad, A.K.; Woodall, P.; Don Ranasinghe, G.; Xie, X.; Liang, Z.; Konstantinou, E.; Heaton, J.; Schooling, J. Developing a Digital Twin at Building and City Levels: Case Study of West Cambridge Campus. J. Manag. Eng. 2020, 36, 05020004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewunruen, S.; Xu, N. Digital twin for sustainability evaluation of railway station buildings. Front. Built Environ. 2018, 4, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursel, I.; Sariyildiz, S.; Akin, Ö.; Stouffs, R. Modeling and visualization of lifecycle building performance assessment. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2009, 23, 396–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francisco, A.; Mohammadi, N.; Taylor, J.E. Smart City Digital Twin–Enabled Energy Management: Toward Real-Time Urban Building Energy Benchmarking. J. Manag. Eng. 2020, 36, 04019045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).