1. Introduction

Globally, demographic patterns are changing unprecedentedly, and the number of older people is on the rise in some countries. The United Kingdom (UK) and South Korea also face drastic shifts in their population age structures. The statistics shown by the United Nations [

1], Statistics Korea, 2023 [

2], and the UK Office for National Statistics, 2023 [

3] are alarming, as demographic changes create multiple complex problems for healthcare delivery, along with issues related to housing arrangements and social welfare programs [

4].

As both South Korea and the UK experience population aging, the number of older adults is increasing, leading to higher healthcare expenses and specialized housing needs, and stronger social support frameworks are required. The low birth rates in both nations create mounting pressure on public funds because they endanger the viability of the retirement system and the sustainability of the healthcare structure. Thus, creative solutions are required to manage population aging [

5,

6]. Older people want to stay in their homes because they want to age in place and have emotional attachments [

7]. Therefore, there is an urgent need to find modern solutions for the care and housing provision of older people.

In response to growing demographic pressures, both South Korea and the UK have implemented aging-in-place initiatives that integrate digital health technologies with supportive residential environments. These strategies aim to enhance older adults’ safety, autonomy, and well-being through innovations such as telecare and remote health monitoring. While the underlying goals are similar, the pathways for implementation differ substantially, shaped by each country’s governance structure and policy environment.

Rather than detailing specific technologies or national features at this stage, this study positions smart aging-in-place as a policy and design response that combines technological potential with institutional coordination. Effective aging-in-place strategies depend not only on technological readiness but also on regulatory support, public investment, and equitable service delivery. Government-backed programs play a critical role in ensuring that older adults have access to safe, adaptable housing and integrated healthcare—regardless of income, region, or digital proficiency [

8,

9].

This study focuses on South Korea and the UK because, while both nations face similar demographic pressures and pursue digital innovation to support aging-in-place, they do so through markedly different institutional logics. South Korea emphasizes centralized policy coordination and top-down implementation, whereas the UK adopts a decentralized, community-oriented model shaped by locally driven service delivery and governance. These contrasting frameworks offer a valuable basis for comparison. While other countries such as Japan and China also face aging-related challenges, the deliberate focus on South Korea and the UK allows for a more in-depth examination of how national governance structures influence the design, deployment, and ethical dimensions of smart aging-in-place strategies. The scope and objectives of this study are therefore centered on exploring the intersection of digital health technologies, housing policy, and institutional coordination in two distinct but instructive policy environments.

The primary objectives guiding this review are as follows:

- ▪

To examine how public–private partnerships and national governance models shape the implementation of smart housing technologies for aging-in-place in South Korea and the UK.

- ▪

To analyze policy frameworks and regulatory conditions that enable or constrain the integration of digital technologies in residential eldercare systems.

- ▪

To evaluate the financial sustainability, scalability, and user accessibility of smart housing ecosystems designed for the aging population in both national contexts.

This study seeks to address the following critical research questions:

- ▪

How do governance structures and institutional models in South Korea and the UK influence the adoption and scalability of smart housing strategies for aging-in-place?

- ▪

What are the key policy, financial, and ethical considerations shaping the implementation of technology-assisted residential care for older adults in both countries?

2. Methods

This study employed a comparative qualitative case study design to examine how smart residential technologies and healthcare systems are integrated into aging-in-place strategies in South Korea and the UK. The methodological approach emphasized a policy-oriented, document-based comparison, aiming to uncover how different institutional, cultural, and technological systems shape aging policy implementation. The design was exploratory in nature, focusing on thematic interpretation and cross-national contrast rather than on quantitative measurement.

2.1. Case Selection

South Korea and the UK were purposively selected as case countries based on their structural and strategic divergence. South Korea represents a centralized, top-down governance model with high levels of investment in AI-driven smart infrastructure for aging populations. In contrast, the UK operates through a decentralized governance framework, emphasizing community-based care supported by telecare systems. This juxtaposition provides a meaningful lens through which to assess how state structure, political will, and public sector coordination affect the scale and direction of digital aging initiatives.

2.2. Data Sources

Data collection was conducted between January and March 2025 and drew from four principal categories of secondary sources. These included national policy documents and official statistics, such as South Korea’s Ministry of Health and Welfare reports and aging policy briefs, alongside strategic documents from the UK Department of Health and Social Care and NHS England. International standards and comparative benchmarks were obtained from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), particularly in relation to healthy aging and digital health governance. Peer-reviewed academic literature was retrieved from Google Scholar, PubMed, and Scopus, using keywords such as “aging-in-place”, “smart healthcare”, “IoT for older adults”, and “comparative housing models”. In addition, industry and market reports from smart home technology providers and healthcare innovation consultancies were included to capture real-world applications and adoption challenges.

2.3. Inclusion Criteria

Documents were included for analysis if they were published between 2010 and 2025, addressed either national strategies or implementation mechanisms related to aging populations, and provided empirical data, conceptual frameworks, or evaluative insights into smart residential technologies or elder care systems. Only sources available in English or Korean (with accessible translated summaries) were selected. This allowed for both comprehensiveness and consistency in the cross-national comparison.

2.4. Analytical Approach

The analytical process followed a qualitative content analysis framework, combining thematic coding with structured comparative synthesis. Each document was read in full to identify its institutional framing, policy positioning, and relevance to the research objectives. Key analytical themes were deductively developed and coded across the cases, including technology adoption, privacy and data governance, cost and affordability, social inclusion, and implementation capacity. These themes were then used to organize the evidence into comparative matrices that traced convergence and divergence across national contexts. A triangulation strategy was employed to cross-verify patterns across academic sources, government reports, and industry publications, thus enhancing the credibility and trustworthiness of the findings.

This methodological approach enabled a multi-dimensional understanding of how smart aging-in-place strategies unfold within different governance regimes. It also supported a deeper interpretation of how institutional structure—not just technological capacity—shapes the pace, direction, and equity of digital transformation in elder care policy.

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Literature Screening

A comprehensive literature review was performed using Google Scholar as the main database, due to its interdisciplinarity, with backward and forward snowballing of references of papers that were retrieved. Searches were conducted using keyword combinations such as “smart residential environment”, “ageing societies”, “healthcare technology”, “assistive technologies”, and “elderly care” and narrowed to English-language journals from 2010 to 2023. A starting pool of about 150 papers was reviewed for duplication and pertinence to residential, technology-based healthcare for the elderly, to finally arrive at the final number of 80 studies. The abstracts were scrutinized for consistency with the research emphasis on healthcare effectiveness and technological implementation in aging, resulting in 50 papers. Full-text analysis focused on empirical strength and innovation and rejected non-empirical or duplicate works. The last 32 references were chosen for their direct impact on the comprehension of user adaptability, technological feasibility, and healthcare outcomes in aging societies.

3.2. Demographic Trends and Healthcare Challenges

The accelerating growth of older adults within populations creates severe difficulties for health services and residential care along with social systems. In 2050, approximately 2.1 billion individuals globally will be part of the population aged 65 years or above [

1], and statistics show that this will bring higher rates of chronic diseases and potential functional restrictions [

1,

10]. The healthcare sector needs sustainable solutions because managing costs must align with senior well-being, including access to accommodative housing infrastructure.

3.3. Technological Strategies in South Korea and the UK

Socio-political factors in South Korea and the UK have resulted in separate programs for older people’s care. South Korean senior care policies focus on in-place living support through a hybrid healthcare system that connects AI technologies with remote medical tracking [

6]. Remote diagnostic systems with artificial intelligence help providers discover healthcare problems early, facilitating the need to hospitalize patients less frequently. Under the Care Act 2014 of the UK government, the person-centered approach takes priority, to keep people centered on their life choices and interactions with society [

11].

New technologies benefit older adults by providing daily monitoring, assistance in daily living activities, emotional companionship, and functional improvements, promoting independent living among the elderly. These solutions enhance communication, cognitive function, and social engagement [

12]. Research shows that smart home technology can significantly reduce hospitalization rates and encourage active aging [

13]. South Korea conducts AI-driven real-time health monitoring, whereas the UK prioritizes ethical considerations, focusing on privacy and user autonomy [

14].

Despite their benefits, smart home technologies face barriers, such as high costs, usability issues, and data security concerns [

15,

16]. Many older adults struggle with digital literacy, which limits their adoption [

17]. The UK addresses this by providing user training and simple interfaces, leading to higher system acceptance [

14].

IoT-based housing is gaining traction, enabling fall detection, remote health tracking, and emergency response systems [

8,

18]. Wearable sensors and home automation assist caregivers by providing continuous health insight [

19,

20]. However, privacy concerns and interoperability issues remain major hurdles that require standardized frameworks for better integration [

21].

Both countries implement housing-related financial support tailored to their welfare and policy systems. Detailed policy distinctions are examined in

Section 4.2. Each government acknowledges that housing strategies influence the living conditions of seniors through isolation protection, combined with economic integrity and medical service availability. Numerous institutions in South Korea have dedicated funds to AI-based smart housing development, whereas the UK focuses on community programs for older people’s engagement [

13]. South Korea implements rapid technological development through its central planning system, but the UK supports sustainable growth by collaborating with public and private stakeholders [

14].

Smart housing adoption faces challenges because its technological implementation costs are high, and it produces privacy issues as well as digital accessibility barriers. Technology-based healthcare services in South Korea face inadequacies in data protection laws that create issues regarding who owns the medical information [

21]. According to Pirzada et al., a solution to British privacy concerns involves establishing visible data management systems for building user trust [

14].

Smart home technology depends on three critical aspects: financial efficiency, user convenience, and available system functionality. Research indicates that 80% of older adults prefer using simple voice-activated systems that function with simplicity instead of complicated AI automatic systems [

22]. Telecare services provided in the UK save approximately USD 5000 per patient annually, offering a more cost-effective option compared to institutional care, which can cost up to USD 20,000 per year [

13].

The analysis of relevant research documents shows that aging populations need new approaches to offer better support to senior citizens. Three innovative systems—smart residential care, IoT, and smart home systems—demonstrate potential improvements in older people’s lives. They promote friendship development, improved memory function, and enhanced movement capabilities. These technologies encounter restrictions regarding their implementation because of their high expense levels, difficulties navigating the systems, and concerns about security risks. Research needs to examine the actual impact of government housing welfare policies on older adults because these programs currently play a vital role in their support. Despite the growing body of research on smart homes for older adults, two significant gaps in the literature are evident:

- ▪

Human-Centered Design Metrics: While technical aspects of smart home technologies are well-researched, there is a lack of comprehensive studies focusing on human-centered design metrics. This includes understanding how older adults perceive and interact with smart home technologies and how these systems can be tailored to meet diverse user needs and preferences.

- ▪

Intergenerational Tech Transfer Models: There is limited research on intergenerational models for transferring technology skills and knowledge between younger and older generations. Such models could enhance digital literacy among older adults and facilitate more effective use of smart home technologies, thereby bridging the digital divide and improving access to healthcare services.

These gaps highlight the need for further research that addresses the social and behavioral aspects of technology adoption among older adults, as well as innovative strategies for intergenerational collaboration in technology use.

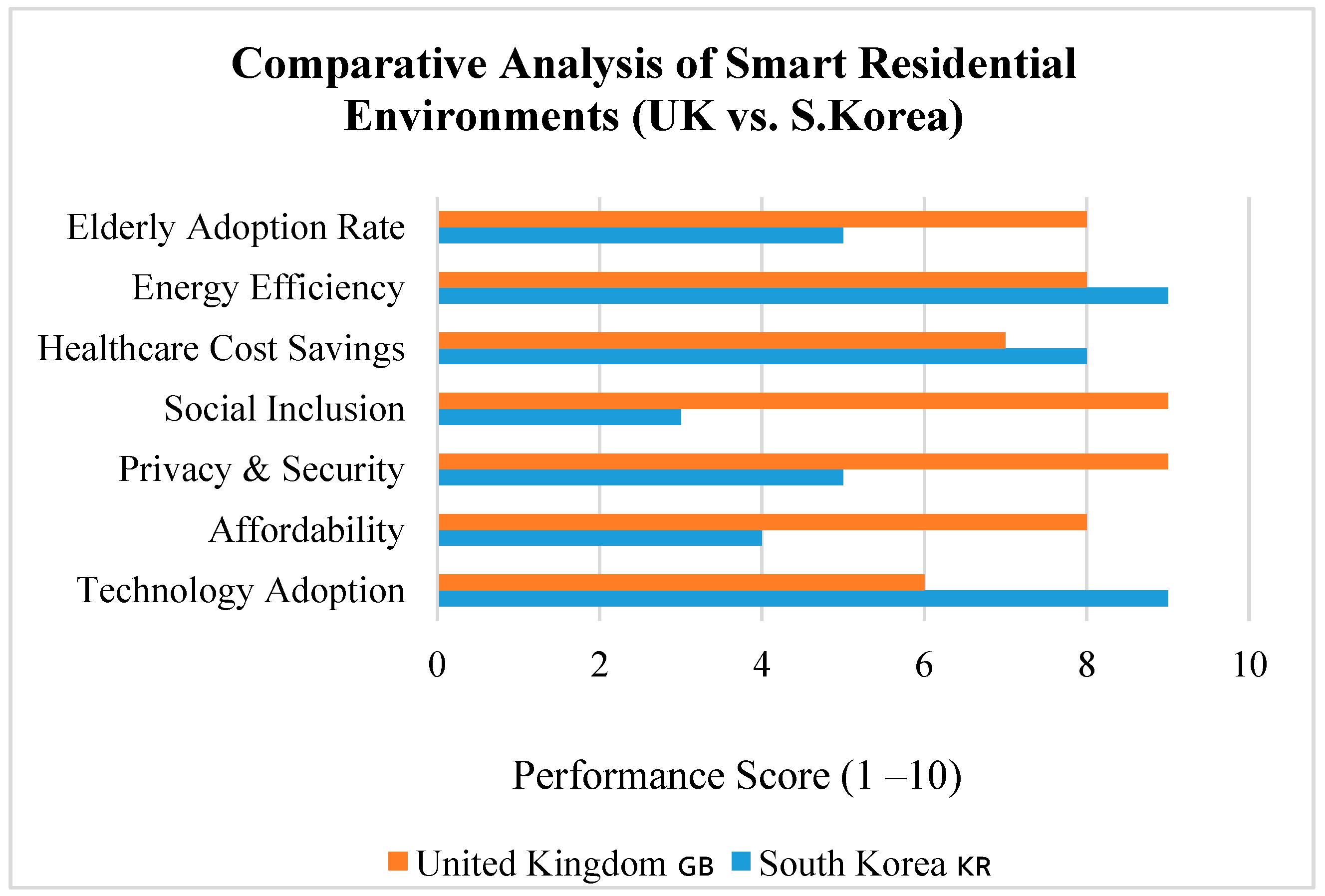

3.4. Comparative Evaluation of Strategies

The comparative examination of different smart healthcare and housing strategies for the aging population in South Korea and the UK discloses that, whereas South Korea is ahead with AI-based smart healthcare and technology-based housing solutions, the UK stresses patient privacy, moral standards, and local community-oriented housing models. Both countries struggle with data privacy, digital literacy, and upholding human interaction in the presence of technological push. To understand it quantitatively, based on the data, there is a simple breakdown of the scores for South Korea vs. the UK based on a performance scale of 1–10 (

Table 1).

10 = Excellent Performance

(robust evidence of wide implementation, and system-level integration);

8–9 = Very Good Performance

(strong evidence of adoption with some variation or limitation);

5–7 = Moderate Performance

(mixed evidence with partial or pilot-scale initiatives);

3–4 = Poor Performance

(fragmented efforts or significant barriers to implementation);

1–2 = Very Poor Performance

(little or no evidence of active strategy or progress).

These scores were used to visually compare key thematic categories, such as technology adoption, privacy protection, affordability, and user acceptance, between the two countries in

Table 1 and

Figure 1.

4. Discussion

The following section provides a comparative analysis of smart healthcare and housing for older people in the UK and South Korea.

4.1. Smart Healthcare in South Korea and the UK

The increasingly older populations in South Korea and the UK prompted innovative healthcare strategies aimed at improving care quality, accessibility, and system efficiency. Smart healthcare plays a vital role in older people’s care management by leveraging telehealth, telecare, and IoT-based health monitoring to enhance healthcare efficiency and reduce the burden on traditional medical facilities [

6,

19]. Both South Korea and the UK have introduced smart healthcare initiatives to support aging-in-place, but the institutional models and implementation outcomes differ significantly.

South Korea has adopted a centralized, top-down approach, deploying AI-based monitoring systems, IoT-enabled home devices, and data-integrated platforms. These tools are embedded in government-supported pilot projects and long-term strategies focused on proactive health management and real-time emergency response. However, large-scale adoption has been hindered by high installation costs (averaging USD 50,000 per unit), digital literacy barriers, and growing concerns around data privacy, particularly among vulnerable populations [

23].

In contrast, the UK pursues a more decentralized and socially embedded approach. Telecare and remote health technologies, such as in-home sensors, video consultations, and wearable devices, are implemented through the NHS and local care networks to promote independent living. Yet the system faces critical barriers, including a shortage of care workers, inconsistent digital maturity across regions, and fragmented delivery due to divided responsibilities among NHS, local authorities, and social care agencies [

24,

25,

26].

These differences are not only technical or financial but also reflect divergent governance logics. South Korea’s national-level regulatory model has enabled rapid policy rollout, standardization, and national coordination despite its top-down rigidity [

27]. Meanwhile, the UK’s locally managed system—while adaptive to community needs—often experiences gaps in integration and scale due to overlapping mandates and political complexity [

28,

29]. As a result, aging-in-place efforts in the UK remain unevenly developed and highly dependent on local leadership capacity. These differences in institutional logic are further discussed in

Section 4.2.

4.2. Comparative Policy Implications for Smart Aging-in-Place

The contrasting approaches of South Korea and the UK offer important insights into how national governance models shape smart aging-in-place strategies. South Korea’s centralized policy environment allows for clear mandates, unified funding mechanisms, and strong alignment between ministries and private partners. This structure has facilitated the national rollout of AI-integrated smart homes and healthcare technologies. However, this top-down coordination may limit flexibility at the local level and often lacks built-in responsiveness to diverse community needs [

27].

By contrast, the UK employs a more decentralized and community-oriented model, where responsibilities for implementation are distributed across the NHS, local authorities, and social care providers. While this framework fosters adaptability, it has also led to fragmentation in funding, service delivery, and accountability [

28], but also the integration of coherence and scalability of innovation [

29].

In contrast, South Korea’s model has enabled the swift deployment of smart infrastructure and AI applications. Yet this efficiency comes with trade-offs, including reduced user participation, limited personalization, and ethical concerns related to automation. The Korean system’s focus on operational performance has at times overlooked the importance of emotional well-being and user empowerment in elder care.

These differences in governance structure reflect broader strategic priorities. The UK’s socially embedded and care-oriented model favors gradual, community-led development, while South Korea emphasizes rapid national transformation through digital innovation. This divergence underscores the need for policy frameworks that can balance implementation speed with adaptability, and technological ambition with human-centered values. The strengths and limitations of each system demonstrate that innovation must be context-sensitive, not only technologically robust but also ethically and socially responsive.

4.3. IoT-Based Housing Design for the Older Population

IoT-enabled smart housing offers older adults enhanced safety, comfort, and independence by integrating technologies such as remote health monitoring, fall detection, and automated home controls [

15]. In South Korea, AI-driven smart home solutions are designed to optimize security, energy efficiency, and medical responsiveness for elderly residents [

26]. In contrast, the UK emphasizes housing models that prioritize accessibility, social connection, and assisted living features supported by digital infrastructure [

30,

31].

South Korea’s housing strategy reflects a technology-first and centrally coordinated approach, with a strong emphasis on new-build developments equipped with advanced systems. These smart homes often feature voice-activated controls, biometric recognition, and AI-linked sensors for continuous health and behavioral monitoring. Government subsidies and investment programs have accelerated the adoption of these technologies, particularly in urban pilot projects [

19]. Alongside safety and care functions, IoT-based energy management systems contribute to sustainability and cost reduction [

23]. However, this model tends to lack social design elements, raising concerns about isolation and limited opportunities for community interaction among older residents [

32].

The UK, by contrast, adopts a socially oriented and retrofit-focused model. Rather than prioritizing fully automated housing, it emphasizes the adaptation of existing homes through publicly funded modification grants. These upgrades typically include fall detection devices, automated lighting, and stair lifts [

11]. A defining feature of the UK’s model is the integration of telecare, enabling continuous digital communication between residents and care providers [

13]. These smart features are embedded within broader living arrangements—such as co-housing and retirement villages—that prioritize social engagement and communal support. In addition, national renovation programs aim to improve energy efficiency while keeping housing affordable for older populations [

22]. While South Korea’s approach centers on digital infrastructure, the UK model advances user autonomy, emotional well-being, and community participation through localized flexibility [

25].

These contrasting strategies reflect different priorities: South Korea’s emphasis on technological sophistication contrasts with the UK’s commitment to socially embedded design. However, they also highlight opportunities for integration. South Korea’s infrastructure-led model could benefit from enhanced community-oriented planning, while the UK’s socially driven approach may be strengthened by the deeper incorporation of proactive health-monitoring technologies.

4.4. Design and Functionality: A Comparative Perspective

Differences in smart housing design between South Korea and the UK are driven by distinct national priorities in eldercare, technology-intensive systems in Korea versus socially integrated solutions in the UK.

4.4.1. Technology Focus (South Korea)

South Korea’s smart housing emphasizes real-time health monitoring, advanced safety features, and automation through AI. As outlined in

Section 4.3, these residences commonly employ biometric entry systems and virtual assistants for managing environmental conditions and personal care [

21]. While technologically sophisticated, the absence of integrated social inclusion features may increase the risk of emotional isolation among older adults.

4.4.2. Community-Oriented Model (UK)

The UK has focuses on adaptable and socially engaging environments rather than complete automation. Policies support home modifications, accessible design, and healthcare integration to help older adults remain active within their communities [

29]. This model facilitates both medical support and meaningful social interaction through proximity-based care and shared spaces.

4.4.3. Cost Efficiency

Smart housing in South Korea involves substantial financial investment due to its reliance on high-tech infrastructure and full automation [

23]. Meanwhile, the UK achieves greater cost efficiency by funding targeted home adaptations and promoting energy-efficient retrofits. These measures increase accessibility and reduce long-term expenses, particularly for older adults with limited income.

These economic and design contrasts reveal that both countries face trade-offs between cost, innovation, and social inclusion—underscoring the need for integrated policy responses to guide the future of aging-in-place.

4.5. Policy Recommendations for Enhancing Aging-in-Place Strategies

Drawing on comparative insights from South Korea and the UK, this section proposes five actionable policy directions that move beyond existing implementation challenges. These recommendations aim to address both technological and social dimensions of aging-in-place innovation.

4.5.1. Build Public Trust Through Transparent and User-Controlled AI Systems

While South Korea leads in AI-enabled healthcare systems for older adults, adoption is hindered by widespread privacy concerns and limited user understanding. Studies show that 42% of older adults express discomfort with home monitoring technologies due to unclear data ownership and a lack of control [

14]. To address this, AI governance should adopt transparent frameworks where users are empowered to manage consent, data access, and system functionality. The UK’s approach—grounded in regulatory frameworks for user autonomy and data minimization—offers valuable precedents. Policies must mandate clear communication, opt-in defaults, and feedback loops to improve adoption and public confidence.

4.5.2. Promote Hybrid Care Models Combining AI Monitoring with Responsive Human Support

Although South Korea has advanced AI infrastructures, it lacks integrated human support, particularly in rural and socially vulnerable areas. Conversely, the UK’s telecare services emphasize personal responsiveness but suffer from technological underutilization. A hybrid care model—merging South Korea’s proactive AI monitoring with the UK’s relational care systems—can optimize resource use and user experience. This dual-approach strategy could involve integrating community-based call centers with real-time AI health alerts to ensure older adults receive both immediate medical attention and human reassurance when needed.

4.5.3. Refocus Smart Housing from High-Cost Automation to Scalable, User-Friendly Retrofits

Current smart housing strategies in South Korea rely heavily on new construction and high-cost automation, with units often exceeding USD 50,000 per installation. However, studies show that older adults are more likely to adopt technologies that are simple, familiar, and customizable [

17]. Policymakers should shift investment toward scalable retrofitting schemes, offering modular add-ons such as smart alarms, voice-activated controls, and environmental sensors. The UK’s model—prioritizing energy-efficient, telecare-integrated retrofits at a cost of USD 7000–USD 10,000 per household—demonstrates a more equitable path forward, especially for existing housing stock and marginalized communities.

4.5.4. Expanding Energy-Efficient Smart Homes with Government Incentives

Energy-efficient smart home technology in South Korea enables families to save 15 to 25 percent on their energy bills per year, according to [

26]. These savings make smart homes financially viable for older people [

33], which demonstrates that the UK’s smart housing technology produces an average yearly saving of USD 3500 for older people’s living costs through energy-saving systems.

Low adoption rates exist for energy-saving smart homes because residents need to pay expensive initial installation expenses. Empirical evidence demonstrates that forty percent of senior citizens abstain from investing in smart energy systems because of the expensive start-up expenses [

29].

Government programs should provide financial incentives consisting of grants coupled with affordable financing options to help people acquire these installations. The UK energy incentive models with financial assistance for retrofits present a solution to boost accessibility to these measures.

4.5.5. The Programs That Integrate Housing with Social Inclusion Activities Must Receive Improved Financial Support

The community-based housing system in the UK shows a 35% decrease in senior isolation, and it decreases healthcare expenses while improving older people’s mental state, according to previous research [

30]. Research indicates that South Korea’s technological emphasis on smart homes creates up to 50% increased loneliness among older residents [

3].

Smart home automation systems deliver important advantages, but older people need human connections for their complete well-being. Research shows that British healthcare data demonstrate the superiority of smart technology combined with community residential settings versus single-house AI systems [

34].

The South Korean government should support the adoption of UK-style community housing, which combines shared smart spaces that allow older citizens to socialize and receive help via intelligent home systems.

4.6. Policy Recommendations for Scaling Aging-in-Place Innovation

This study highlights that technological readiness alone is insufficient to ensure the success of smart aging-in-place strategies. Effective implementation depends on supportive policy frameworks, multi-sector collaboration, and long-term institutional investment.

First, national governments must establish sustainable financing models to support the development and maintenance of smart housing infrastructure [

35]. This may include targeted subsidies, integration with health and long-term care insurance schemes, and public–private partnerships to reduce upfront costs and improve cost-effectiveness over time.

Second, cross-sector coordination between housing, health, and welfare ministries is essential to avoid fragmented implementation. Integrated policymaking bodies or interdepartmental task forces could improve alignment and reduce duplication of effort, especially in decentralized systems where service responsibilities are dispersed.

Third, workforce training and institutional capacity building must accompany technological deployment. Care workers, housing managers, and local authority staff require digital literacy and operational support training to effectively manage and explain smart systems to older residents.

Fourth, inclusive innovation ecosystems should be encouraged by funding pilot programs, supporting co-design methodologies, and creating feedback loops between users, service providers, and technology developers. These systems can help adapt solutions to local contexts and ensure that innovation remains responsive to changing user needs [

36].

Fifth, national governments should establish centralized data governance standards and digital health infrastructure to support interoperability, privacy protection, and system integration. Without these foundational elements, smart care systems are likely to remain isolated, underutilized, or untrusted.

In addition to these structural and institutional considerations, emerging technologies such as advanced AI, natural language processing, and generative algorithms are expanding the possibilities of smart aging-in-place strategies. These tools can enhance remote diagnostics, personalize care recommendations, and improve communication between older adults and healthcare providers through conversational interfaces. As AI capabilities evolve beyond sensor-based monitoring, they offer the potential to support cognitive engagement, emotional well-being, and early detection of mental health decline. However, these advancements also raise ethical and governance challenges, underscoring the need for transparent algorithms, informed consent, and equitable access to ensure these tools benefit all older populations.

Taken together, these recommendations emphasize the need for aging-in-place strategies that are not only technologically advanced but also structurally supported, ethically guided, and institutionally embedded.

4.7. Strategic Governance and Political Barriers

The scalability and sustainability of aging-in-place strategies are ultimately shaped by governance systems that determine how effectively digital innovations are translated into practice. While technological advancement sets the stage, it is political will, institutional coherence, and intersectoral coordination that dictate the pace and equity of implementation.

In the UK, political decentralization and longstanding structural separation between healthcare and social care have created fragmented delivery systems. Although this allows local tailoring, it often results in overlapping responsibilities, uneven service provision, and gaps in accountability, particularly for vulnerable populations [

25,

27,

28]. The UK’s ambitious digital care goals are frequently undermined by workforce shortages, budget instability, and regional disparities. These limitations have slowed the adoption of telecare systems and hindered the integration of housing, health, and social care services [

27,

28].

By contrast, South Korea’s centralized institutional strategy led by Korean government enables national-level alignment between digital health policy, housing investment, and infrastructure development. Top-down coordination has supported the rapid deployment of smart technologies and large-scale pilot programs [

32]. However, this efficiency is not without trade-offs. Limited input from frontline providers or residents can lead to standardized solutions that lack adaptability and overlook local nuances or emotional well-being concerns.

These governance dynamics do not merely affect administrative efficiency; they directly impact the inclusiveness, trustworthiness, and ethical foundations of digital aging strategies. While the UK excels in community-based care ethics and social engagement, it struggles to scale innovation due to fragmented authority. South Korea, conversely, achieves technological rollout at scale but must work to embed responsiveness, user consent, and feedback mechanisms into its approach.

As both countries navigate these tensions, it becomes clear that strategic governance is not a peripheral concern. It is the infrastructure upon which all aging-in-place innovation depends. The ability to coordinate across sectors, maintain policy continuity, and prioritize equitable delivery will be decisive in determining whether smart systems truly enhance the lives of older people, or deepen existing gaps.

4.8. Ethical Framework for Smart Aging-in-Place

As digital technologies become embedded in elder care strategies, ethical considerations must be made explicit to ensure that aging-in-place systems are not only effective but also respectful of older adults’ rights and preferences. This study proposes a practical ethical framework comprising four core principles tailored to smart healthcare and housing implementation:

1. Transparency: Older adults and caregivers should clearly understand how systems operate, what data are collected, and how they are used. Information must be communicated in accessible, non-technical formats.

2. Autonomy: Users must retain meaningful control over their environments, including the ability to adjust settings, grant or revoke consent, and determine the level of monitoring that suits their comfort.

3. Informed Consent and Privacy: Ethical deployment requires ongoing, informed consent procedures and robust privacy safeguards. These should include secure data handling, anonymization protocols, and clear opt-out options.

4. Equity and Accessibility: Design and policy must account for diverse cognitive, physical, cultural, and economic circumstances. This ensures that smart systems do not inadvertently exclude vulnerable groups.

Embedding these ethical priorities into national strategies will help mitigate risks and promote public trust, thereby supporting the sustainable and inclusive scaling of smart aging-in-place innovations.

4.9. Limitations

This study focuses on South Korea and the UK because they represent contrasting approaches to smart aging-in-place strategies. While other countries, such as Japan and China, also face similar demographic pressures, the deliberate focus on South Korea and the UK enables a more in-depth and comparative analysis, aligning with the scope and objectives of this study.

5. Conclusions

The preceding sections offer a comprehensive evaluation of smart healthcare systems, housing design, and government policies supporting senior citizens in the UK and South Korea. Both nations are experiencing demographic shifts towards an aging population, presenting significant challenges for healthcare, social care, and housing authorities. The increasing number of older individuals also impacts the economic structure of society. To address these challenges, innovative techniques are being adopted.

The implementation of modern healthcare technologies, including IoT-based smart home systems and other assistive technologies, demonstrates significant potential to enhance the lives of older adults. These technologies not only reduce feelings of isolation but also improve cognitive function, safety, and mobility. Consequently, their implementation is likely to enhance the quality of life for seniors.

Policymakers must focus on three primary areas post-implementation to enhance the effectiveness of these initiatives: the utilization of smart technologies, digital collaboration among social care workers, and the technical fluency and design solutions of technology to align with user needs and preferences. Continuous development in elder care systems is essential in both South Korea and the UK. Integrated healthcare solutions, alongside IoT systems in residential spaces, present critical opportunities to enhance the quality of life for seniors and facilitate aging-in-place. Each country has adapted its care systems in response to unique social conditions, cultural backgrounds, and economic circumstances. South Korea has excelled in adopting rapid high-tech solutions, while the UK has gained valuable insights from person-centered care delivered through community-based services. Both countries should implement policy intervention strategies to advance their elder care systems. These strategies must be sustainable, user-friendly, accessible, and cost-effective to improve the quality of life and well-being of older adults.