Abstract

Traditional Japanese architecture is known for its open, ambiguous spatial boundaries (“kyokai”), which integrate nature and dwelling through Zen/Shinto philosophies. Yet modern urban housing, driven by high-density minimalism, flattens spatial hierarchies and erodes these rich boundary concepts. This study aims to explore how Japanese architect Yoshiji Takehara reinterprets traditional spatial principles to reconstruct the interior–exterior relationships in modern housing through a mixed-methods approach—including a literature review, case studies, and semi-structured interviews—verifying the hypothesis that he achieves the modern translation of traditional “kyokai” through strategies of boundary expansion and ambiguity. Analyzing 78 independent residential projects by Takehara and incorporating his interview texts, the research employs spatial typology and statistical methods to quantify the characteristics of boundary configurations, such as building contour morphology, opening orientations, and transitional space types, to reveal the internal logic of his design strategies. This study identifies two core strategies through which Takehara redefines spatial boundaries: firstly, clustered building layouts, multi-directional openings, and visual connections between courtyards and private functional spaces extend interface areas, enhancing interactions between nature and daily life; secondly, in-between spaces like corridors and doma (earthen-floored transitional zones), double-layered fixtures, and floor-level variations blur physical and psychological boundaries, creating multilayered permeability. Case studies demonstrate that his designs not only inherit traditional elements such as indented plans and semi-outdoor buffers but also revitalize the essence of “dwelling” through contemporary expressions, achieving dynamic visual experiences and poetic inhabitation within limited sites via complex boundary configurations and fluid thresholds. This research provides reusable boundary design strategies for high-density urban housing, such as multi-directional openings and buffer space typologies, and fills a research gap in the systematic translation of traditional “kyokai” theory into modern architecture, offering new insights for reconstructing the natural connection in residential spaces.

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

The relationship between interior and exterior spaces has always been a central issue in both Eastern and Western philosophy and design practice. In Western architectural theory, the concept of “liminal space” reveals the profound significance of transitional zones—spaces that are neither entirely enclosed nor completely open, but rather stimulate users’ perception and experience through ambiguity. As anthropologist Victor Turner noted, the liminal state represents “a threshold between structure and anti-structure”, a concept manifested in architecture through intermediary spaces such as porches, courtyards, and corridors. These spaces serve not only as physical transitions but also as psychological sites of ritual transformation. In Building Dwelling Thinking, Heidegger reframed this discourse, arguing that the essence of “dwelling” lies in a symbiotic state of existence between humans and their environment. Architecture, as a mediator, should guide inhabitants toward achieving ‘poetic dwelling’ within space.

Japanese traditional architecture offers a distinctive response to this discourse, characterized by its openness to nature and the intentionally ambiguous boundaries between interior and exterior. For instance, the doma (earthen-floored transitional space, 土間) (doma (土間): an earthen-floored transitional zone in traditional houses, blending indoor and outdoor functions) in vernacular houses extends into the interior as a semi-outdoor space, functioning both as a workspace and a climatic/cultural buffer zone between inside and outside. Similarly, the shoji (sliding paper screens, 障子) of sukiya-style architecture and the engawa (verandas, 縁側) (engawa (縁側): a veranda-like edge space mediating interior and exterior) of shoin-zukuri employ adaptable interfaces to draw nature inward, while their deep eaves create transitional buffer zones in the depth direction. These elements collectively blur the division between interior and exterior, forming an interpenetrating spatial “kyokai” (boundary design, 境界) (kyokai (境界): a Japanese concept of spatial boundaries, encompassing both physical interfaces (e.g., walls) and perceptual thresholds). Architect Kengo Kuma described this characteristic as emblematic of Japanese traditional architecture’s approach to “kyokai”, noting that it serves as a treasure trove of such boundary-design techniques, with timeless influence [1]. This concept transcends mere physical thresholds—it embodies the philosophical essence of Zen’s “wabi-sabi” (austere tranquility, 侘寂) and Shinto’s “nature worship”, where spatial demarcations are not barriers but deliberate ambiguities that evoke contemplation and reverence for nature.

However, amid the trends of urban densification and minimalist design in contemporary housing, some architectural solutions have fallen into the trap of formalism. While minimalism rightly emphasizes functional purity and visual simplicity, its excessive focus on “subtraction” risks flattening spatial hierarchies. For instance, certain residences reduce the boundary between interior and exterior to vast glass curtain walls. Though this enhances visual connectivity, it often neglects the transitional value of intermediary zones, resulting in monotonous spatial experiences. This simplistic inside/outside binary division not only diminishes the richness inherent in traditional kyokai (spatial thresholds) but may also alienate the very essence of dwelling. When nature becomes a passive visual spectacle—observed but not engaged—Heidegger’s ‘poetic dwelling’ risks being subsumed by technological rationality.

1.2. Yoshiji Takehara and His Perspective on Residential Design

Against this backdrop, the architectural practice of Japanese architect Yoshiji Takehara demonstrates groundbreaking significance as his designs counter this trend by reinterpreting traditional spatial hierarchies through modern interventions. Born in 1948 in Tokushima Prefecture, Takehara began his career working at the esteemed Kenchiku Design Studio founded by architect Osamu Ishii, whose design philosophy profoundly influenced him [2,3]. In 1979, he established his own firm in Osaka. Specializing primarily in residential-focused structures such as independent houses, nurseries, and elderly care facilities, Takehara has earned the reputation of being a “master of residential architecture”. Since the 1980s, his works have been featured over 100 times in specialized residential design magazines. The style of his works has shown little change over the years, demonstrating a consistent and stable quality that has garnered significant attention [4].

An overview of Yoshiji Takehara’s discourse on residential design reveals his advocacy for inheriting the traditional Japanese architectural concept of “kyokai” (spatial threshold), through which he integrates living spaces with the natural environment [5,6,7]. This philosophy manifests in his meticulous treatment of the transitional realm between interior and exterior spaces. His works frequently feature complex floor plans or clustered building layouts [8].

A prime example is his 1997 masterpiece, the “House of Koryocho”, which employs a clustered layout with three discrete volumes dispersed across the site. These staggered masses envelop multiple courtyards, creating rich adjacencies between interior and exterior spaces. The resulting interstitial outdoor areas alternate between compressed and expansive scales, producing dynamic spatial experiences. Furthermore, Takehara often incorporates semi-outdoor transitional zones like corridors between indoor rooms and gardens. In his 2002 self-designed residence “House of 101st”, the second-floor living area connects to the courtyard via an open-air corridor. Paired with floor-to-ceiling sliding doors that enhance visual permeability, this arrangement allows the living space and garden to overlap and interpenetrate, blurring their boundaries into ambiguity.

These designs not only revive the buffer function of traditional “in-between spaces” but also reinterpret the essence of dwelling through contemporary language—demonstrating how spatial layering and ambiguity can, even within constrained sites, facilitate an ongoing dialogue between inhabitants and nature. Takehara’s practice reminds that true minimalism lies not in formal reduction but in distilling essence through complexity, weaving the tangible and intangible aspects of “kyokai” to restore poetry and spirituality to residential spaces.

In this study, the term “kyokai” is defined as the boundary between spaces—whether between the interior and exterior of a building or between the interior spaces themselves. It encompasses both physically tangible divisions and perceptually experienced thresholds in psychological consciousness. This research focus on the “kyokai” within modern Japanese independent residences examines the works of Yoshiji Takehara, a representative contemporary residential architect, as a case study. Through analysis of spatial boundary configurations and their compositional characteristics, the study reveals the distinctive features and design methodologies of “kyokai” in his residential projects. The findings aim to provide design references for modern urban independent housing amid increasing density trends.

Based on this, the study proposes a core hypothesis: Yoshiji Takehara’s design strategy, by expanding boundary interfaces and blurring physical thresholds, can achieve a modern reinterpretation of traditional “boundary” in high-density urban environments, thereby enhancing the poetic quality of living experiences.

1.3. Review of Previous Research

Previous studies analyzing the relationship between interior and exterior spaces in modern independent residences and their design methodologies include research examining the spatial composition of houses from a positional relationship perspective [9], mathematical analyses of interior–exterior configurations [10], investigations into the design of openings connecting indoor and outdoor spaces [11], and studies on the connectivity between courtyards and main rooms in urban courtyard houses [12].

Regarding research specifically focused on the spatial relationships in Yoshiji Takehara’s residential works, notable examples include: analyses through photographs and textual records of Takehara’s works that explore interior–exterior spatial relationships through his use of light, shadow, and materiality to create atmospheric depth [13].

In Western architectural and landscape theory, there are also numerous classic works on the design of boundaries between interior and exterior residential spaces, including Norman K. Booth and James E. Hiss discussing the design of “entry spaces” and “walls and fences”, emphasizing the symbolic and functional significance of boundaries. They also advocate that entrances, as “ceremonial spaces” transitioning between inside and outside, should balance privacy and openness [14]. Brian Lawson identifies residential boundaries as key nodes in “spatial narratives”, suggesting that contrasts in materials (such as stone and wood) and variations in light and shadow can accentuate the distinction between indoor and outdoor spaces [15]. Bruno Zevi highlights the “dynamic transition” of residential entrances, arguing that elements like ramps and staircases provide a psychological adaptation process for users [16]. Colin Rowe and Robert Slutzky propose the use of materials like glass and lattices to achieve visual permeability, thereby blurring the boundaries between interior and exterior (as seen in Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion) [17]. These works provide multidimensional perspectives—from theory to practice—on the design of boundaries between interior and exterior residential spaces while also underscoring the importance of such design considerations.

The aforementioned related studies primarily focus on analyzing either the positional characteristics of interior–exterior arrangements within residential sites or the connectivity between these spaces. While the relationship between interior and exterior spaces in housing is generally determined by manipulating the planar configuration of transitional boundaries and the composition of openings along these interfaces, the existing literature lacks comprehensive research that systematically examines both the spatial organization and connectivity of interior–exterior relationships through an integrated analysis of boundary morphology and compositional features—precisely the methodological approach adopted in this study, offering a novel methodological framework for interpreting modern adaptations of traditional Japanese spatial principles.

The study constructs a cross-cultural analytical matrix by synthesizing Japanese architectural epistemology (“kyokai” philosophy and “Ma” theory) with Western phenomenological frameworks (Heideggerian dwelling concept and Turnerian liminality).

2. Research Methods

For the research type of design methodology, a combination of literature review (including interviews with the architect) and case analysis is typically adopted as the research method. This study primarily focuses on the investigation and analysis of Yoshiji Takehara’s works and writings, supplemented by interviews with the architect himself.

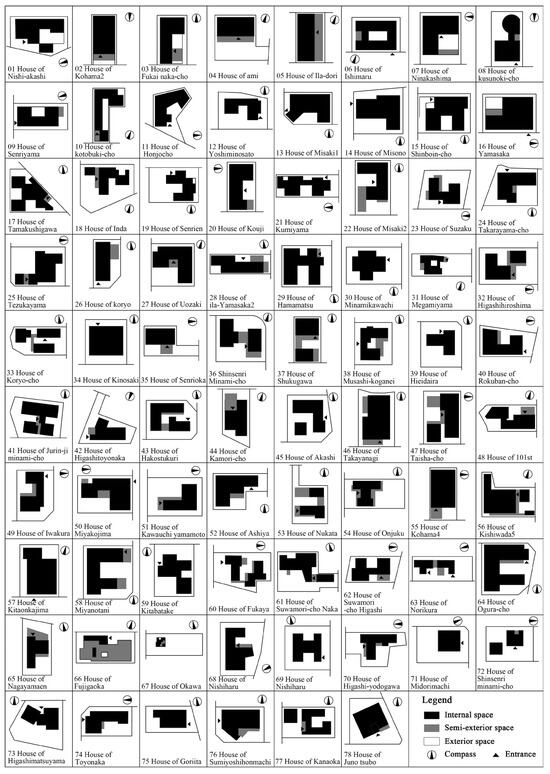

2.1. Review and Analysis

For the literature review, keywords and design intentions related to residential approaches were organized from Takehara ’s publications, as well as works and commentaries featured in magazines. Independent residential works by Takehara Yoshiji were selected as the subject of study from specialized housing magazines. The selected works consist of 78 projects by Takehara Yoshiji, built before he turned 70 (from 1983 to 2015, during his active career period), which were published in authoritative Japanese specialized magazines such as Jutaku Tokushu (Residential Special Features), Jutaku Kenchiku (Residential Architecture), and Kenchiku Bunka (Architectural Culture), and the availability of complete data (plans, sections, pictures) (Figure 1 and Table A1). Among them, two project cases consist of two independent and complete residential buildings each; therefore, each case is counted as two study subjects, resulting in a total of 80 study subjects.

Figure 1.

Summary of research cases (source: author).

For the analysis of architectural works, this study defines the “interior–exterior boundary domain” as the physical interfaces—including exterior walls, doors, and windows—that objectively demarcate indoor and outdoor spaces. The planar configuration of these boundaries fundamentally influences the spatial relationship and organizational logic between interior and exterior domains. Furthermore, based on established boundary configurations, the characteristics of openings—such as their dimensions, placement, and spatial layering—significantly impact both functional use of living spaces and visual experiences within residences. These two aspects are essential to residential spatial studies as they directly shape inhabitant experience.

Building upon comprehensive understanding of Takehara’s works and writings, this study analyzes selected projects through dual lenses:

Boundary Configuration: The spatial arrangement between building masses and external areas.

Boundary Composition:

- (1)

- Functional connectivity between indoor programs and outdoor spaces;

- (2)

- Interfacial relationships between adjacent interior–exterior zones;

Specific analytical criteria include:

- Extraction and analysis of interior–exterior boundary configurations;

- Examination of interior functions connected to exterior spaces;

- Study of opening method in main interior spaces facing outward;

- Cross-sectional analysis of boundaries between main interior and exterior spaces.

2.2. About the Interview

To extract Yoshiji Takehara’s design intentions for residential design and clarify the research direction, an interview was conducted with Yoshiji Takehara On 22 May 2018, regarding the design method for independent residences. The discussion primarily focused on key considerations in residential design, including approaches, zoning, the connection between indoor and outdoor spaces, circulation, building materials, and the style of his works. Regarding the two aspects relevant to this study’s analysis—residential zoning and the connectivity between interior and exterior spaces—their overview has been systematically organized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of the interview.

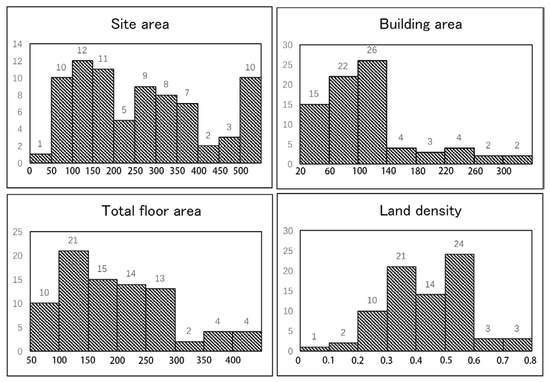

3. Basic Information of Cases

The research cases total 78, ranging from the work “House of Nishi-Akashi” which first appeared in the target magazine in 1985 to “House of Juno Tsubo” published in 2015. The indicative information of residential projects—including site area, building area, total floor area, and land density—was extracted from all case study data and compiled in Figure 2. According to Figure 2, the site area ranges from less than 100 m2 to over 500 m2, with an average value of 276 m2. In terms of the floor area of the building, 63 cases are concentrated within the range of 20 to 140 m2, and the average value is 100 m2. The total floor area has 73 cases within the range of 50 to 300 m2, with an average value of 150 m2. As for the building coverage ratio, 69 cases are found within the range of 0.2 to 0.6, and the average value is 0.39.

Figure 2.

Basic information of the target case (source: author).

4. The Boundary Morphology of Interior–Exterior Spaces

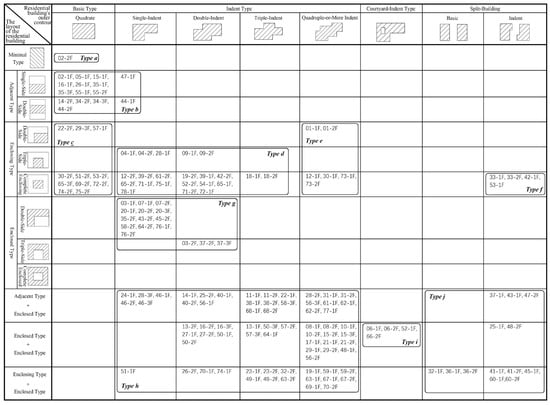

4.1. Extraction of the “Boundary Form”

First, by controlling the planar shape of a building’s outer contour, the total length of the boundary between the interior and exterior spaces will also change. Based on this, as shown on the horizontal axis of Figure 3, the outer contour shapes are categorized from simple to complex: a square is classified as the “basic type”, one with a single inward indentation as the “single-indent type”, one with two inward indentations as the “double-indent type”, one with three inward indentations as the “triple-indent type”, and one with four or more indentations as the “quadruple-or-more-indent type”. An outer contour with indentations and an internal courtyard enclosed by the building on all sides is classified as the “courtyard-indent type”. Additionally, the split-building cases are categorized according to their outer contour shapes as the “split-building basic type” and the “split-building indent type”. Each above-ground floor of all residential cases is classified and extracted according to the aforementioned types.

Figure 3.

Typology of boundary forms between interior and exterior spaces (source: author).

Next, the placement of the building on the site affects the positional relationship between the interior and exterior spaces, as well as the orientation of their boundaries. Based on this, as shown on the vertical axis of Figure 3, buildings that fully occupy the site are classified as the “minimal type”. Cases where interior and exterior spaces are adjacent in parallel are categorized as the “adjacent type”. Within this type, if the exterior space is located on one side of the building, it is classified as the “single-side adjacent type”, while if exterior spaces exist on two opposite sides, it is called the “double-side adjacent type”.

Cases where the exterior space surrounds the interior space are classified as the “enclosing type”. Among these, L-shaped enclosures are labeled the “double-side enclosing type”, U-shaped enclosures the “triple-side enclosing type”, and fully enclosed interior spaces the “complete enclosing type”. Conversely, cases where the exterior space is enclosed by the interior space are classified as the “enclosed type”, which similarly includes the “double-side enclosed type”, “triple-side enclosed type”, and “complete enclosed type”.

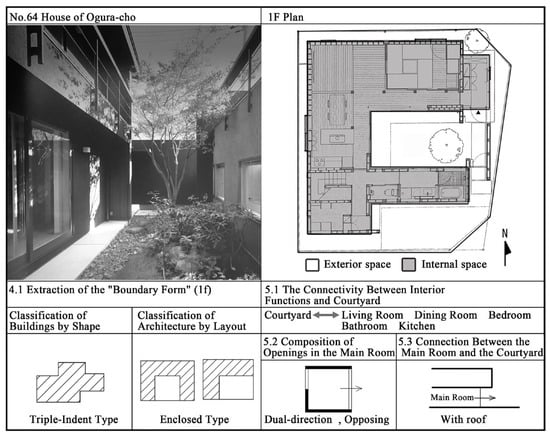

Additionally, a single case with a more complex spatial configuration may belong to multiple types simultaneously, such as “adjacent type + enclosed type”, “enclosing type + enclosed type”, or “multiple enclosed types”. Using this method, each above-ground floor of all cases is extracted and classified. Representative analysis examples are shown in Figure 4.

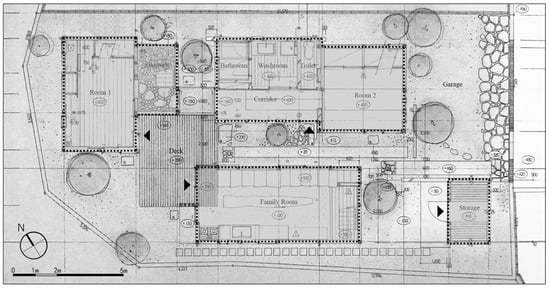

Figure 4.

Analysis example (source: author).

4.2. Classification and Analysis of Boundary Form

As illustrated in Figure 3, the classification based on boundary length is set as the table’s horizontal axis, while the classification based on the spatial relationship between interior and exterior is arranged along the vertical axis. Each floor of every residential project is extracted as one boundary form and categorized in Figure 3 (the numbers in the diagram represent the case number and corresponding floor). By systematically mapping the distribution of all boundary forms, ten typological patterns (a–j) are identified.

Type a represents a minimal-site spatial configuration where the building occupies almost the entire plot, leaving no external space.

Type b is a spatial configuration with a basic outer contour and an adjacent placement type. The interior spaces adjacent to the exterior tend to be elongated, suggesting that the exterior functions as an extension of the interior, thereby expanding the living space.

Type c features a basic outer contour and an enclosing placement type, with most cases occurring on upper floors of residences.

Types d and e exhibit a curved outer contour and an enclosing placement type. These residences intentionally incorporate external spaces, such as approach paths and courtyards, through strategic indentation of building volumes, demonstrating an efficient use of exterior areas.

Type f is a composite configuration with split buildings and a fully enclosing placement type. These residences actively shape interior–exterior relationships by dividing structures on spacious plots.

Type g has a curved outer contour and an enclosed placement type, often seen in courtyard houses. By introducing protrusions on limited plots, these homes integrate external spaces and strengthen interior–exterior connections.

Type h combines a curved outer contour with hybrid placement types (e.g., “adjacent + enclosed”, “enclosed + enclosed” or “enclosing + enclosed”). While sharing traits with types d, e, and g, its composite layout intensifies interior–exterior interactions.

Type i employs a reversed-curve outer contour and a dual-enclosed placement type. With courtyards fully encircled by structures, it surpasses Type g in spatial interplay.

Type j adopts a split-building outer contour and a complex hybrid placement. The division increases boundary surfaces, enabling diverse spatial combinations and generating intricate interior–exterior dynamics—making this the most strongly interconnected type. The representative case is the “House of Koryocho” (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

House of Koryocho: layered courtyards and ambiguous thresholds (source: reference [4], with modifications by the author). Note: The dashed line box represents the planar outline of the building. The triangle symbol represents the building entrance.

This analysis confirms that manipulations of outer contours (e.g., protrusions, split forms) and varied spatial relationships enrich residential design. Such strategies complicate the boundary configuration, extend multi-directional boundaries, and enhance connectivity between interior and exterior spaces.

5. The Boundary Configuration of Interior–Exterior Spaces

5.1. The Connectivity Between Interior Functions and Exterior Spaces

The external spaces of residences, such as courtyards, serve not only as outdoor living areas for occupants to dwell in but also as visual extensions that enhance the interior experience through openings like windows and doors. This section analyzes the visual connectivity between various interior functions and courtyard spaces—specifically, which indoor functions courtyards visually serve through these openings and how this relationship has evolved over time.

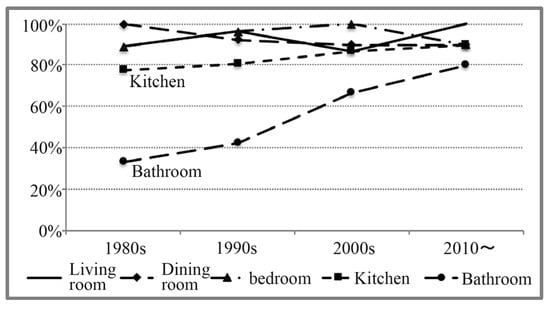

Case studies reveal that the interior functions most closely linked to courtyards through visual connections are the living room, bedroom, dining room, kitchen, and bathroom. Figure 6 illustrates the chronological changes in the proportion of cases where these five interior functions maintain visual continuity with the courtyard. Figure 6 presents data derived from line-of-sight analysis of case study floor plans, quantifying the percentage of direct visual linkages between functional spaces and courtyards. The results show that the living room, dining room, and bedroom consistently maintain a high connectivity rate of over 80% across all periods. In contrast, the visual connection between bathrooms and courtyards exhibits a significant upward trend over time, while kitchens also demonstrate a slight increase.

Figure 6.

Connectivity between interior functions and exterior spaces (source: author).

These findings indicate that, as time progresses, residential courtyards have expanded their role beyond serving primarily communal spaces like living and dining rooms—areas where family members gather most frequently. Instead, they have gradually permeated into more private and individualized aspects of domestic life, such as bathrooms (traditionally high-privacy spaces) and kitchens (traditionally associated with domestic labor). This shift allows occupants to engage with nature even during intimate activities like bathing or cooking, thereby enriching their visual experience while strengthening the courtyard’s connection to a broader range of daily rituals.

5.2. The Design of Openings Toward the Exterior in the Primary Living Space

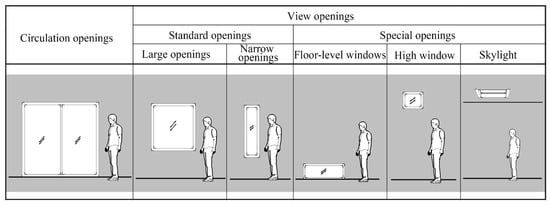

This section will analyze the characteristics of external openings in architecture that connect interior and exterior spaces. The living room, as the most important functional space internally, is selected, and the living room along with the spaces spatially integrated with it are defined as the “main room”. The external openings in all case study main rooms are categorized as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Classification of openings in the main room (source: author).

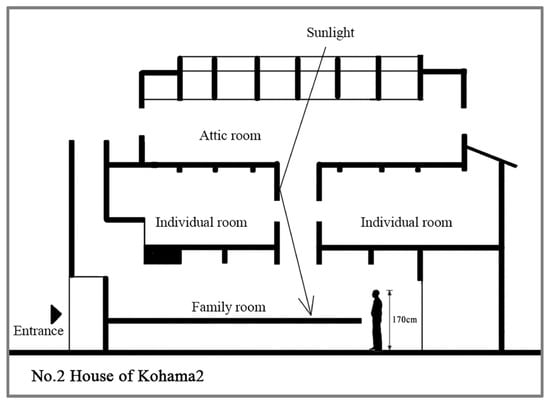

First, the openings are divided into two types based on whether a person can pass through them: “circulation openings” and “view openings”. Among the “view openings”, those through which a standing person (170 cm tall) can horizontally see the outdoors are classified as “standard openings”, while those located at special heights (such as floor-level windows, high windows, skylights, etc.) are classified as “special openings”. The “standard openings” are further subdivided into “large openings” and “narrow openings”.

Among these types, the “circulation openings” and “standard openings”, due to their larger areas, are defined as “primary openings”.

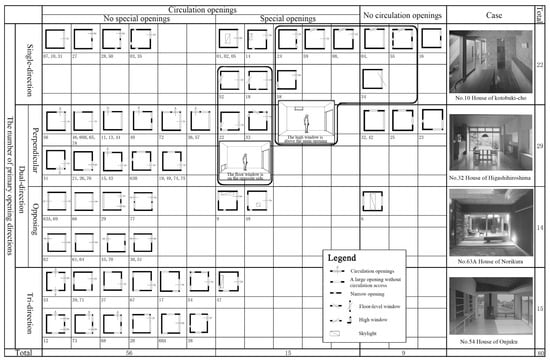

Next, all case studies were categorized into three groups based on the number of primary opening directions in the main room: “single direction”, “dual direction”, and “tri-direction”. The opening configurations of all main rooms are then illustrated in Figure 8 according to their opening types. The numbers in the diagram represent the case numbers and their corresponding quantities.

Figure 8.

Characteristics of openings to the exterior in the main room (source: author).

The results show that 71 cases (the majority) featured “circulation openings”, indicating that most main rooms had direct access to outdoor spaces. Among the “single-direction” cases, those with “special openings” were predominant (13 out of 22), suggesting that these designs adopted an opening strategy combining “primary openings + special openings” to meet lighting and ventilation needs.

The “dual-direction” cases were further divided into two types based on the spatial relationship between primary openings: “perpendicular” and “opposing”. These two opening configurations create distinct visual experiences:

- -

- In the “perpendicular” type, primary openings were placed on two adjacent, perpendicular walls, enabling panoramic views in two directions.

- -

- In the “opposing” type, primary openings were positioned on opposite walls, visually integrating the interior space with the external environments on both sides, forming a continuous “outside–inside–outside” spatial sequence.

Among the “tri-direction” cases, primary openings were present on three out of four possible sides. This configuration simultaneously incorporated the two visual experiences observed in the “dual-direction” cases.

Additionally, upon examining cases with special openings such as “floor-level windows” and “high windows”, we observe the following patterns:

- (1)

- Without exception, all floor-level windows were positioned on the wall opposite to the circulation opening (Cases No. 18, 22, 33, 52).

- (2)

- All high windows were located on walls perpendicular to the circulation opening (Cases No. 04, 08, 24, 34, 55, 58, 59).

- (3)

- Most of these cases belonged to the “single-direction” category.

Clearly, these two types of special openings were designed to address lighting issues (as most main rooms only had one primary light-receiving surface). Furthermore, the floor-level windows opposite to circulation openings provide a framed view for people entering the main room from outside.

Among the cases featuring skylights (eight in total), the majority (Nos. 04, 08, 24, 34, 55, 58, 59) had main rooms not located on the top floor. In these designs:

- (1)

- Portions of the main room’s ceiling were hollowed out.

- (2)

- Skylights were installed in the upper level.

- (3)

- Light entering through these skylights was then reflected by the upper-level walls down into the main room below (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Lighting methods using skylights and atriums (source: author).

Figure 9. Lighting methods using skylights and atriums (source: author).

This design method was frequently employed in cases with limited site area (approximately 100 m2), proving to be an effective solution for addressing lighting challenges in compact residential spaces.

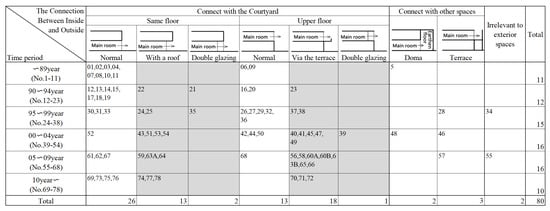

5.3. The Connection Method Between the Main Room and External Space

Regarding the main room space, the connecting areas with external spaces were organized using cross-sectional pattern diagrams, as shown on the horizontal axis of Figure 10. The external spaces connected to the main room were divided into “connect with the courtyard”, “connect with other spaces”, and cases where the main room was “irrelevant to exterior spaces”.

Figure 10.

The connection between the main room and the external space (source: author).

When the main room was connected with the courtyard, it was further categorized into “same floor” or “upper floor” depending on whether they were on the same level. For “same floor” connections, we classified cases as “normal” (direct courtyard access), “with a roof” (a roofed buffer space before the courtyard), or “double glazing” (transitional fittings). For “upper floor” connections, they were divided into “normal” (direct link), “via the terrace” (terrace as intermediary), or “double glazing” (with a buffer zone).

For “connect with other spaces”, the external areas were labeled as “doma” or “terrace”. An analysis of case numbers revealed that “connect with the courtyard” (73/80 cases) was predominant, with “normal” on the same floor (26/41) and “via the terrace” on the upper floor (18/32) being the most common subtypes. The numbers in the diagram represent the case numbers and their corresponding quantities.

Next, cases were arranged chronologically on the vertical axis. The gray areas in Figure 10 represent patterns where the main room and courtyard were linked via buffer spaces like doma, engawa, corridors, or terraces. While rare in early periods, these buffer space designs increased over time, demonstrating a growing preference for transitional zones adjacent to the main room.

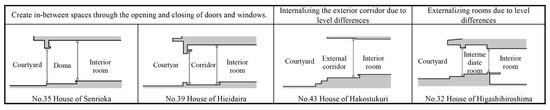

In his writings, Yoshiji Takehara repeatedly emphasizes the presence of semi-outdoor spaces in traditional architecture, referring to them as “in-between spaces” [18]. An examination of the connections between main rooms and external spaces in his works reveals that interiors and exteriors are seldom directly linked through openings. More commonly, an in-between space—such as interior corridors, exterior corridors, doma (earthen-floored entryways), or even semi-outdoor spaces without designated functions—separates the main room from the courtyard. This observation aligns with the earlier analysis. Examples like the “House of Senrioka” and “House of Hieidaira” (Figure 11) demonstrate how doma and interior corridors act as transitional “intermediate zones” between inside and outside, mediating spatial transitions while simultaneously amplifying the perceived depth when viewed from the interior.

Figure 11.

Ambiguous threshold between interior and exterior (source: author).

Another notable aspect is the deliberate use of double-layered building fixtures (doors, windows, etc.) and carefully designed floor level differences. For example, in the “House of Hakosaku” (Figure 11), the exterior corridor and interior room have a 180 mm floor level difference. When viewed from the inside, the lower edge of the door is concealed by this height variation, creating a visual continuity between the corridor and interior flooring. Meanwhile, due to the significant level difference between the exterior corridor and the courtyard, the corridor—which would typically belong to the exterior—appears visually as an extension of the interior space. Similarly, in the “House of Higashihiroshima”, the ma-room (intermediate room) has a depth of approximately 1.8 m, which would normally classify it as an interior space. However, with a 600 mm level difference from the inner room and the door frame to the courtyard subtly concealed by a slight elevation change, the ma-room is visually externalized.

Through the incorporation of in-between spaces, floor level variations, and the interplay of double-layered fixtures, residential spaces gain flexible functionality. The conventional binary distinction between “inside” and “outside” is dissolved, allowing the two domains to overlap and creating an ambiguous boundary. This ambiguity manifests both physically and psychologically.

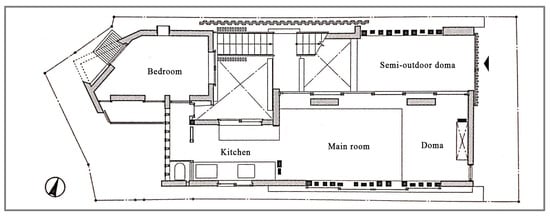

5.4. The Outdoor Ground Extending into the Interior

Japanese residential design carefully considers the shoe-removal ritual upon entry. In modern homes, this is typically manifested through genkan (entryways) with elevated floor levels, while traditional dwellings often feature a “doma”—an earthen-floored area maintaining the same height and material as the outdoor ground. These design elements are prominently reflected in both the theories and works of Yoshiji Takehara [19,20].

Several case studies in this research demonstrate creative adaptations of traditional doma spaces. For instance, in Takehara’s own residence “House of 101st” (Figure 12), the main room features a partially raised floor (approximately 100 mm) that psychologically demarcates spatial boundaries. The lower doma area shares identical flooring material with the semi-outdoor doma space. This configuration creates a sequential transition where occupants experience three distinct spatial thresholds while entering, effectively dividing the environment into four experiential zones (outdoor → semi-outdoor → indoor doma → main room), producing a graduated spatial perception.

Figure 12.

Sequential transition from doma to main room in House of 101st (source: reference [19], with modifications by the author).

6. Discussion

6.1. Divergent Approaches to Traditional Translation Praxis

The concept of “Kyokai” (境界) in Japanese architecture originates from the spatial organization of traditional settlements and buildings. Transcending the functional division of physical boundaries, it constitutes an “interface mechanism” that integrates cultural symbolism with spatial mediation [21]. This notion profoundly embodies the Japanese cultural understanding of “Ma” (間)—a dialectical unity of spatial interval, transition, and ambiguity [22]. In contemporary architectural practice, architects, including Yoshiji Takehara, Kengo Kuma [23], and Shigeru Ban [24], have, respectively, reinterpreted this traditional concept through three dimensions: tectonic logic, material medium, and structural system, thereby providing diversified design strategies for high-density urban housing.

6.2. Multi-Dimensional Explorations of In-Between Space

The three architects demonstrate distinct spatial intervention strategies regarding “in-between space”. Yoshiji Takehara’s “House of 101st” achieves gradual spatial transitions through dual-layer fixtures and precise elevation treatments (e.g., 180 mm platforms), extending the ritualistic spatial experience of engawa (veranda) in sukiya-style architecture (Figure 12). In “House of Koryocho”, he expands architectural interfaces via geometrically complex operations (split-volume composition and chamfered corners), creating multidirectional permeable boundaries (Figure 5).

Kengo Kuma’s “Bamboo House” reinterprets traditional shoji screens’ permeability (“透”) and dynamism (“动”) through bamboo-curtain walls as mutable interfaces, establishing non-linear boundary logic using contemporary tectonic vocabulary [25]. Conversely, Shigeru Ban’s “Paper Church” employs paper-tube structures to generate homogeneous, translucent spatial environments that dissolve conventional interior–exterior dichotomies, achieving maximal spatial expansion with minimal materiality [26].

This comparison reveals Yoshiji Takehara’s nuanced preservation of traditional spatial sequences while highlighting Kuma’s symbolic reinterpretation and Ban’s subversive approach to transcending architectural conventions.

7. Conclusions

7.1. Research Findings

This study set out to examine how Yoshiji Takehara reinterprets traditional Japanese spatial principles (e.g., kyokai) to reconstruct interior–exterior relationships in modern housing. Through a mixed-methods analysis of 78 residential projects, we identified two core strategies—boundary expansion and ambiguity—that align with Takehara’s philosophy of fostering dynamic interactions between dwellers and nature. Through analysis of transitional zones, opening configurations, and connection methods between interior and exterior spaces, the design strategies for spatial relationships in residential architecture are identified as follows:

- (1)

- Expansion of interior–exterior connectivity.

Specific techniques include:

- Enlarging boundary surfaces between interior and exterior spaces by incorporating projecting corners or dividing the building into multiple volumes.

- Creating openings toward the exterior in multiple directions within interior spaces.

- Connecting the main courtyard not only to communal family areas but also to private functional spaces like bathrooms.

These approaches enhance interior–exterior connections by expanding boundary interfaces and establishing visual relationships through multi-directional openings and connections between the garden and all interior functions. This not only enriches spatial experiences within the living environment but also allows exterior spaces to engage with all aspects of daily life.

- (2)

- Ambiguation of interior–exterior boundaries.

Specific methods include positioning in-between spaces where interior and exterior spaces intermingle between main living areas and gardens, combined with layered boundaries created through the operation of building fixtures and floor level variations. This intentional blurring of boundaries transforms simple divisions into multi-layered, profound thresholds with spatial depth, resulting in increasingly complex relationships between interior and exterior spaces.

Based on the above findings, the author argues that Yoshiji Takehara’s residential designs inherit formal characteristics of traditional Japanese architecture (such as spatial planning, in-between spaces, and floor level variations). By expanding boundary conditions between interior and exterior domains, coupled with meticulous design of openings, transitional spaces, level differences at thresholds, and operable building fixtures, his works create dynamic and richly layered spatial interfaces within living environments. This approach fosters dialogue between indoors and outdoors, enhances living flexibility and comfort, and intensifies the relationship between residents and nature through the deliberate complication and ambiguity of spatial boundaries.

The substantial number of commissions and realized projects throughout his decades-long career demonstrate the resonant quality of his design philosophy. The dual strategies of boundary expansion and ambiguity offer a framework for architects to introduce natural spaces into compact residential sites. Furthermore, the incorporation of special openings in main living areas presents an effective solution for improving daylighting and ventilation in spatially constrained dwellings. Against the backdrop of increasingly smaller plot sizes for detached houses in contemporary Japan, Takehara’s methodology offers viable solutions to counteract spatial monotony and strengthen interior–exterior connections in residential design.

7.2. Recommendations

The design strategies regarding the relationship and connectivity between interior and exterior spaces revealed in this study offer numerous valuable references for contemporary detached house design and represent applicable knowledge for practical implementation. Based on the findings, practical recommendations are proposed:

- (1)

- Multi-directional openings to enhance visual connectivity without sacrificing privacy. Multi-directional openings in primary living spaces (e.g., living rooms) enhance visual connectivity, while special openings (e.g., floor-level windows, skylights) balance privacy and daylight needs.

- (2)

- Buffer typologies (e.g., elevated doma) to mediate climate and cultural transitions in high-density contexts. Buffer space typologies, inspired by transitional logic of doma and engawa, can mediate climatic and cultural transitions through stepped level differences or semi-outdoor zones. In high-density contexts, dynamic boundary configurations (e.g., split volumes, nested courtyards) maximize interface interactions to avoid spatial monotony.

Furthermore, Takehara’s modern translation of traditional elements highlights the need for architects to balance formal simplicity with spatial complexity, thereby reconstructing natural connections in residential environments.

7.3. Future Research

This study addresses a critical gap in the existing literature by systematically analyzing both the boundary morphology and compositional features of transitional zones, a comprehensive approach previously underexplored in studies of Takehara’s works.

The limitations of this study suggest future research directions: First, reliance on published archival data may introduce selection bias toward Takehara’s celebrated works; incorporating unpublished projects or comparative analyses with peer architects (e.g., Kengo Kuma, Shigeru Ban) could validate the universality of boundary design strategies. Second, field surveys or occupant interviews are needed to quantify the psychological impacts of boundary design (e.g., spatial depth perception, frequency of nature engagement), complementing plan-based analyses. Finally, digital tools (e.g., parametric modeling, environmental simulation) could optimize the performance of complex boundary configurations in high-density contexts, such as synergizing lighting and ventilation efficiency. These directions will advance systematic understanding of the modern translation of “Kyokai” theory.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.L.; methodology, L.L.; validation, L.L. and H.L.; formal analysis, Y.C.; data curation, L.L. and H.L.; writing—original draft preparation, L.L. and Y.C.; writing—review and editing, L.L. and Y.C.; visualization, L.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported by “The Cultivation project Funds for Beijing University of Civil Engineering and Architecture” (X25010).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Summary of cases.

Table A1.

Summary of cases.

| No. | Project Name | Date of Completion | Publication | No. | Project Name | Date of Completion | Publication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | House of Nishi-akashi | March 1983 | Jutaku Tokushu, Summer 1985 | 40 | House of Rokuban-cho | April 2000 | Jutaku Kenchiku, June 2006 |

| 2 | House of Kohama2 | February 1985 | Jutaku Tokushu, June 1986 | 41 | House of Jurin-ji Minami-cho | June 2000 | Jutaku Tokushu, September 2000 |

| 3 | House of Fukai naka-cho | December 1985 | Jutaku Tokushu, January 1987 | 42 | House of Higashitoyonaka | February 2001 | Jutaku Tokushu, September 2001 |

| 4 | House of ami | December 1986 | Jutaku Tokushu, August 1987 | 43 | House of Hakostukuri | April 2001 | Jutaku Tokushu, September 2001 |

| 5 | House of Ila-dori | September 1987 | Jutaku Kenchiku, May 1993 | 44 | House of Kamori-cho | August 2001 | Jutaku Kenchiku, March 2005 |

| 6 | House of Ishimaru | May 1988 | Jutaku Tokushu, July 1989 | 45 | House of Akashi | August 2001 | Jutaku Tokushu, May 2002 |

| 7 | House of Ninakashima | September 1988 | Jutaku Kenchiku, May 1993 | 46 | House of Takayanagi | September 2001 | Jutaku Kenchiku, March 2005 |

| 8 | House of kusunoki-cho | December 1988 | Jutaku Tokushu, April 1989 | 47 | House of Taisha-cho | December 2001 | Jutaku Kenchiku, March 2005 |

| 9 | House of Senriyama | March 1989 | Jutaku Tokushu, February 1990 | 48 | House of 101st | May 2002 | Jutaku Tokushu, December 2002 |

| 10 | House of kotobuki-cho | April 1989 | Jutaku Tokushu, February 1990 | 49 | House of Iwakura | July 2002 | Jutaku Kenchiku, March 2005 |

| 11 | House of Honjocho | July 1989 | Jutaku Tokushu, February 1990 | 50 | House of Miyakojima | December 2002 | Jutaku Kenchiku, June 2006 |

| 12 | House of Yoshiminosato | November 1990 | Jutaku Tokushu, November 1991 | 51 | House of Kawauchi yamamoto | January 2003 | Jutaku Kenchiku, June 2006 |

| 13 | House of Misaki1 | November 1991 | Jutaku Kenchiku, June 1993 | 52 | House of Ashiya | December 2003 | Jutaku Kenchiku, June 2006 |

| 14 | House of Misono | December 1991 | Jutaku Tokushu, September 1992 | 53 | House of Nukata | April 2004 | Jutaku Tokushu, August 2004 |

| 15 | House of Shinboin-cho | May 1992 | Jutaku Tokushu, November 1992 | 54 | House of Onjuku | November 2004 | Jutaku Tokushu, February 2005 |

| 16 | House of Yamasaka | June 1992 | Jutaku Tokushu, November 1992 | 55 | House of Kohama4 | March 2005 | Jutaku Tokushu, January 2006 |

| 17 | House of Tamakushigawa | October 1992 | Jutaku Tokushu, February 1993 | 56 | House of Kishiwada5 | May 2005 | Jutaku Tokushu, May 2006 |

| 18 | House of Inda | March 1993 | Jutaku Tokushu, November 1993 | 57 | House of Kitaonkajima | June 2005 | Jutaku Kenchiku, June 2006 |

| 19 | House of Senrien | May 1993 | Jutaku Tokushu, September 1993 | 58 | House of Miyanotani | December 2005 | Jutaku Tokushu, May 2007 |

| 20 | House of Kouji | August 1993 | Jutaku Tokushu, November 1994 | 59 | House of Kitabatake | September. 2006 | Jutaku Tokushu, September 2007 |

| 21 | House of Kumiyama | December 1993 | Jutaku Tokushu, May 1994 | 60 | House of Fukaya | January 2007 | Jutaku Tokushu, September 2007 |

| 22 | House of Misaki2 | April 1994 | Jutaku Tokushu, November 1994 | 61 | House of Suwamori-cho | April 2007 | Jutaku Kenchiku, August 2008 |

| 23 | House of Suzaku | November 1994 | Jutaku Tokushu, May 1995 | 62 | House of Suwamori-cho | June 2007 | Jutaku Kenchiku, February 2013 |

| 24 | House of Takarayama-cho | May 1995 | Jutaku Tokushu, February 1996 | 63 | House of Norikura | November 2007 | Jutaku Tokushu, September 2008 |

| 25 | House of Tezukayama | May 1995 | Jutaku Tokushu, February 1996 | 64 | House of Ogura-cho | March 2008 | Jutaku Tokushu, April 2009 |

| 26 | House of koryo naka-cho | January 1996 | Jutaku Tokushu, May 1996 | 65 | House of Nagayamaen | May 2008 | Jutaku Kenchiku, August 2008 |

| 27 | House of Uozaki kita-cho | October 1996 | Jutaku Tokushu, February 1997 | 66 | House of Fujigaoka | March 2009 | Jutaku Tokushu, August 2010 |

| 28 | House of ila-Yamasaka2 | November 1996 | Jutaku Tokushu, February 1997 | 67 | House of Okawa | August 2009 | Jutaku Tokushu, October 2011 |

| 29 | House of Hamamatsu | January 1997 | kenchiku Bunka, March 2000 | 68 | House of Yamamoto-cho | November 2009 | Jutaku Tokushu, February 2013 |

| 30 | House of Minamikawachi | January 1997 | Jutaku Tokushu, August 1997 | 69 | House of Nishiharu | February 2010 | Jutaku Kenchiku, February 2013 |

| 31 | House of Megamiyama | February 1997 | Kenchiku Bunka, March 2000 | 70 | House of Higashi-yodogawa | February 2011 | Jutaku Kenchiku, February 2013 |

| 32 | House of Higashihiroshima | March 1997 | Jutaku Tokushu, October 1997 | 71 | House of Midorimachi | March 2011 | Jutaku Tokushu, February 2013 |

| 33 | House of Koryo-cho | June 1997 | Jutaku Tokushu, August 1997 | 72 | House of Shinsenri minami-cho | October 2011 | Jutaku Kenchiku, February2015 |

| 34 | House of Kinosaki | December 1997 | kenchiku Bunka, March 2000 | 73 | House of Higashimatsuyama | January 2013 | Jutaku Tokushu, July 2013 |

| 35 | House of Senrioka | April 1998 | Jutaku Tokushu, April 1999 | 74 | House of Toyonaka | May 2013 | Jutaku Kenchiku, February 2015 |

| 36 | Shinsenri Minami-cho | December 1998 | Kenchiku Bunka, March 2000 | 75 | House of Goriita | May 2013 | Jutaku Kenchiku, February 2015 |

| 37 | House of Shukugawa | January 1999 | Jutaku Tokushu, October 1999 | 76 | House of Sumiyoshihonmachi | May 2013 | Jutaku Tokushu, April 2015 |

| 38 | House of Musashi-koganei | January 1999 | Jutaku Tokushu, April 1999 | 77 | House of Kanaoka | December 2013 | Jutaku Kenchiku, February 2015 |

| 39 | House of Hieidaira | January 2000 | Jutaku Tokushu, May 2000 | 78 | House of Juno tsubo | February 2015 | Jutaku Tokushu, April 2015 |

References

- Kuma, K. Kyokai; Tankosha: Tokyo, Japan, 2010; pp. 1–139. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, Y.; Takehara, Y.; Irei, S. Three Residential Architects, Three Different Approaches; X-Knowledge Co., Ltd.: Tokyo, Japan, 2016; pp. 1–175. [Google Scholar]

- Ishii, O.; Takehara, Y.; Taira, K. The Continuity of Conceptual Power in Two Self-Designed Residences. Jutaku Tokushu 2006, 6, 16–26. [Google Scholar]

- Takehara, Y. Yoshiji Takehara’s Residential Architecture; TOTO Publishing: Tokyo, Japan, 2010; pp. 1–318. [Google Scholar]

- Takehara, Y. The Charm of Small House Design. Jutaku Kenchiku 2005, 3, 74–77. [Google Scholar]

- Takehara, Y. Interpreting Spatial Context. Jutaku Kenchiku 2013, 2, 4–5. [Google Scholar]

- Takehara, Y. Nature, Materials, Architecture. Jutaku Tokushu 1990, 2, 84–85. [Google Scholar]

- Takehara, Y. How to Address Compact Housing. Jutaku Tokushu 2006, 8, 124–129. [Google Scholar]

- Kawakita, T. The Arrangement of the Exterior Space and the Interior Space in the Houses Published in 1990 Designed by Japanese Architects. J. Archit. Inst. Jpn. Plan. 1997, 497, 103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto, M.; Hattori, M.; Taniguchi, M. The Characteristic Analysis and Spatial Typology of Urban Court-Houses: A Study on Spatial Composition of Japanese Contemporary Houses. J. Archit. Inst. Jpn. Plan. 2001, 547, 135–142. [Google Scholar]

- Nosaku, F.; Tsukamoto, Y. Reference Between Windows of Contemporary Houses. J. Archit. Inst. Jpn. Plan. 2008, 629, 1643–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, R.; Negayama, A.; Yasuda, K. Furnishing of Courtyards and Connection with Living Rooms in Contemporary Japanese Courtyard Houses. J. Archit. Inst. Jpn. Plan. 2012, 676, 1365–1371. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, T.; Suzuki, T.; Matsubara, S.; Kitata, M. Design of Darkness in Architectural Space Case Study of Takehara Yoshiji’s Houses. In Proceedings of the Kinki Branch Research Presentation Meeting, Kinki, Japan, 31 May 2013; pp. 101–104. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, K.; James, E. Residential Landscape Architecture Design; Beijing Science and Technology Publishing: Beijing, China, 2020; pp. 1–788. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan, R. The Language of Space; China Architecture and Building Press: Beijing, China, 2003; pp. 1–264. [Google Scholar]

- Bruno, Z. Architecture as Space: How to Look at Architecture; China Architecture and Building Press: Beijing, China, 2006; pp. 1–236. [Google Scholar]

- Colin, R.; Robert, S. Transparence; China Architecture and Building Press: Beijing, China, 2008; pp. 1–118. [Google Scholar]

- Takehara, Y. Enjoying In-between Spaces. Nikkei Archit. 2002, 9, 106–107. [Google Scholar]

- Takehara, Y. Non-Being; Gakugei Publishing: Kyoto, Japan, 2007; pp. 1–239. [Google Scholar]

- Takehara, Y. How Living Spaces Transform When Embracing Japanese Harmony. Jutaku Tokushu 2004, 8, 78–79. [Google Scholar]

- Hara, H. Space: From Function to Phenomenon; Iwanami Shoten: Tokyo, Japan, 2007; pp. 1–334. [Google Scholar]

- Isozaki, A. Japan-Ness in Architecture; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006; pp. 1–372. [Google Scholar]

- Kuma, K. Defeated Architecture; Iwanami Shoten: Tokyo, Japan, 2019; pp. 1–278. [Google Scholar]

- Ban, S. Paper Architecture: Taking Action; Iwanami Shoten: Tokyo, Japan, 2016; pp. 1–220. [Google Scholar]

- Kengo Kuma & Associates Great (Bamboo) Wall. Available online: https://kkaa.co.jp/project/great-bamboo-wall/ (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- SHIGERU BAN ARCHITECTS Cardboard Cathedral. Available online: https://shigerubanarchitects.com/works/cultural/cardboard-cathedral/ (accessed on 25 April 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).