1. Introduction

Increasing awareness of the impact of architecture on human emotions is leading to the development of new design ideas. Contemporary health care facilities differ from traditional solutions. In addition to formal and functional aspects, there are issues of aesthetics, comfort, convenience for all users, equality of access and innovation. Centres with a focus on mental health are all the more likely to have a non-standard design approach [

1].

An analysis of contemporary facilities with this function reveals aspects relevant to patient-centred design. Evidence-based design has become an important technique for creating user-friendly spaces, especially those with a health function. As a term, this methodology emerged as early as the 1960s in the United States, and the first publication to address it was ”Effectiveness and Efficiency: Random Reflections on Health Services” by Cochrane [

2]. Evidence-based design is a technique that uses scientific research to create a user-friendly and engaging environment. These are studies relating to branches of medicine that focus mainly on somatic complaints. The analysis of the data allows the creation of design algorithms that can be considered for new and modified facilities [

3].

This technique allows the creation of patient-, staff- and visitor-friendly spaces. Through specific design solutions, it is possible to influence not only the level of environmental stress and the length of the patient’s stay in the facility, but also the amount of medication that patients consume. Physical comfort mainly concerns patients staying in the hospital longer than for a consultation or therapeutic visit [

4].

The phenomenon of the influence of the hospital environment on health is constantly evolving. This is evidenced by the large number of studies that have been carried out in this area, more than 600 [

5]. This paper draws on the work of R. Ulrich, B.R. Lawson and M. Phiri, among others [

6,

7,

8]. The environment, on the other hand, is “a relatively permanent system of elements of the human environment that are important for human life and behaviour” [

9]. The growing interest of architects in environmental psychology has led to a desire to develop new solutions that take into account not only human anatomy but also human psychology. Evidence-based design uses developments in this field to produce design solutions that are dedicated to the user. Architecture has a direct impact on people’s emotions and feelings. This impact can be positive or negative. In the case of people with disorders, it is important because it directly influences the healing process (e.g., an inappropriate environment can lead to pathological reactions, fear, paranoia).

In the field of environmental psychology and its relation to architecture, the Polish pioneer is the psychologist Augustyn Banka, who wrote books such as

Psychologiczna struktura projektowa srodowiska and

Społeczna psychologia srodowiskowa (Psychological structure of the environmental design and sociopsychology of the environment) [

10]. Another important point in the development of wellness-oriented architecture is the work of E. Hall,

The Hidden Dimension, in which he describes aspects of human behaviour that derive from our biological nature [

11]. The Office of the Ombudsman for Children published a research report entitled “Study on the Quality of Life of Children and Young People in Poland”. 13 Its aim was to diagnose the psychological state of the participants, which would later be used to plan and implement supportive policies. The survey was conducted among more than 4600 students at different levels of education: early childhood, primary, secondary [

12].

The data presented on mental health and therapy are intended to show that the healing process requires the creation of an appropriate environment. This is a challenging task for today’s urban planners, architects and designers. While the psychological study of a person focuses mainly on factors from the individual level (social, biological), in the field of child and adolescent studies, researchers pay attention to the relevance of external factors, e.g., the environment of school, home and neighbourhood. In today’s era of civilisation-related illnesses, it is important to create friendly, open and accessible facilities that support psychological development and have the characteristics of therapeutic spaces. The data presented on mental health and therapy are intended to show that the healing process requires the creation of an appropriate environment (see

Table 1). This is a high-priority task for today’s urban planners, architects and designers.

4. Results

The therapist’s work in the centre under study consists of both individual and group work. Patients under the age of 18 are usually seen in the afternoon (after 14.00). The psychologist sees about five patients a day (depending on availability). The visit is based on joint discussion and, exercises and concludes with a consultation with the parent/guardian. Because of the nature of the work, the therapist is able to deduce at what point and for what reason the patient may feel uncomfortable. Through an interview with the staff of the mental health facility, it was possible to identify elements of the built environment that were conducive to the therapy process.

An important issue raised by the study is how patients respond to different elements of the environment, depending on the function of the space. When asked what they look for when entering a building, patients responded as follows:

“I often hear that we have a cosy feel here, that ‘it doesn’t look like a clinic’ or ‘it’s not hospital-like’.”

“[…] very often and very many people have just said that it is so homely, it is not hospital-like and the com-pletely did not expect such an interior”

“For comfortable chairs, cosiness”

The cosy and homey atmosphere influences not only the perception of the patients themselves, but also that of their carers. It helps to break down barriers of anxiety and uncertainty and increases feelings of security, which has a direct impact on the therapeutic process. The interior design of the home is made up of many factors—materials, colors, furnishings, light—but above all, emotions and associations—fun, safety, protection. A patient who is not relaxed and calm will not feel positive about working with a therapist.

Patients with different conditions have different perceptions, but what is common to all users is the ability to relax before a visit. Patients forced to sit idly in a waiting room are at high risk of feeling uncomfortable due to environmental stimuli, thoughts and lack of mental comfort. In order to reduce negative emotions, a form of play and relaxation should be offered before the visit to the therapist. This will make the patient less stressed and more willing to undergo treatment. An appropriate interior design is therefore essential. The entrance area of the facility, as the first enclosed space, should invite patients and parents/guardians in, reassure them and provide psychological and physical comfort.

“The waiting room should be spacious, slightly away from the surgeries, with a corner to drink coffee, tea, with the opportunity to play with a younger child who sometimes comes in together, Seats should be comfortable and relaxing. They should feel looked after”

“Comfortable chairs, some pictures, slightly dimmed light. Possibility to go outside on a bench.”

The interior of a therapeutic facility should encourage positive thinking and create a patient-friendly atmosphere. Depending on the purpose of the room, it should be appropriately equipped and designed with emotions and reactions in mind. Their design must be different from the stereotypical doctor’s office. The following answers were given to the question about interior design elements that have a positive effect on children and adolescents:

“Low tables and colouring books in the waiting room, warm wooden elements, pictures with other children (psychological comics), play areas”

“drawings in offices, pictures on walls”

“Colouring books at small tables, comfortable armchairs/couches in the halls”

The interior can have a positive or negative effect. The user is satisfied and cooperative when his needs are met and his mind is relaxed. The interior design, the dominant colours and the shapes of the furniture are all elements of the built environment that can support or hinder the cooperation between client and therapist. The development of an appropriate attitude in the child/adolescent depends to a large extent on the architecture, which is responsible for creating an atmosphere. When asked about negatively perceived interior elements, staff will respond:

“The fact that they can’t go down to the basement makes them very curious:”

“Posters with prohibitions and orders”

“Some dark blue walls.”

“[…] We even changed the colour of the walls at my place because one patient told us that it was very dark here and it depressed her even more.”

The interior of a therapeutic support centre should invite children to explore it, to play in it, to associate it with development rather than with problems to be solved. Treatment should be an adventure that allows the patient to rediscover his or her identity, abilities and fears. The solutions for such a facility must take into account the diversity of responses due to the illness, the different needs and, above all, the well-being of its users.

“[…] I think patients suffering from depression, for example, may find it difficult to recover in low, dark rooms. People with schizophrenia or high anxiety may feel overwhelmed by long, bright corridors (hospital ones like that).”

“[…] When they cannot wait quite close to their parents—some children find this really difficult. They then go into the room or cry.”

“A quiet zone and a private green space would be a masterstroke. We also work with children on the spectrum or children with disabilities. Hitting each other on the head, the wall etc. are the order of the day. A quiet zone with no or limited stimuli would be a good solution for hypersensitive children.”

The spatial and functional layout of a children’s and adolescents’ mental health centre must be clear and at the same time fascinating. Patients must not have associations with hospital interiors, which stereotypically evoke images of long, white corridors and monotony. At the same time, twisting, unpredictable communication will also contribute to reducing patient safety. The user must be able to create a cognitive map of the facility in order to move around without mental or physical barriers. The identification system should also go beyond traditional thinking (i.e., simple information boards). The layout of the building should make it clear what part of the building has what function and for whom it is intended. When asked how they found their way around the facility, staff responded as follows:

“I think clear, concrete, visible signs (arrows or hints), colour division could be interesting: In our house there are several floors, it might be worth introducing this.”

“Simple way of signposting, accessible and child-friendly”

Receptionist: “We don’t have separate zones, each therapist goes down to get the patient, over time they get used to it so they know where to go, but more signs would be useful.”

The office is a place where the patient has to cross the boundary of psychological comfort. It is a place that can evoke extremely negative associations: the absence of a parent and talking to a therapist about acute problems. The design of such an interior should have an effect on the child/teenager, evoking only friendly and positive emotions. It is the workplace of the patient and the psychologist, and it is important to ensure the comfort of each user. There should be a division between the individual work of the staff and the child/teenager. In addition to the visual aspects, the design should also be functional and provide freedom for the users, e.g., a child who prefers to talk sitting on a carpet rather than on a sofa, or looking at nature outside the window rather than at a picture wall.

“Hm… I think the office should be first of all cosy, warm. There should be space for patient and therapist chairs or armchairs and ideally there should be a desk of some kind”

One function should not interfere with the other, e.g., a one-to-one meeting where peace and quiet is important should not be next to a workshop room where group activities take place. The same applies to administration and patient services. Visitors coming for conferences and lecturers should not gather in the waiting room where young patients are. This can have a negative effect on both groups: a child may feel frightened by the unexpected number of people and an adult may feel irritated by the noise.

“[…] Ideally, there should be some kind of larger room with chairs and a projector just for conferences or w lectures. It could be located downstairs, so that it would be easy to get to it without disrupting other offices and rooms and not overcrowding the It would also be a nice idea to have a place for parents waiting for their children—a corner with psychol ogical papers, for example. something like that I have always dreamed of at our place”

“[…] the possibility of privacy of meetings, i.e., well-planned offices and soundproofed”

Development of therapies: At COGITO, social skills training is carried out, which involves working on the social skills necessary for daily functioning, such as shopping, washing clothes, minor activities in the home, etc. The possibility of carrying out such training requires appropriate equipment in the rooms, which the staff pointed out as an additional facility in the building.

“Definitely rooms for social skills training, e.g., with a mini kitchen, mini grocery shop or other everyday situations that are difficult for some children to handle.”

“relaxation room, experience room—a place to train daily living skills (gasifier, washing machine, mixer, etc. equipment), reading room,”

“Social skills training and workshop rooms”

Studying the evaluation of the therapeutic space from the perspective of the staff, it was possible to see how important the proximity to nature is. Reasons for this phenomenon include associations with nature, the desire to conduct hortitherapy, and the health-promoting activities it has.

“[…] In spring and summer it would also be nice to have such a place outside—some kind of bench around flowers, greenery—a few seats or a bench will be enough.”

“[…] Sensory integration room, garden for learning to be with nature growing vegetables. parking lot, playground, mini outdoor waiting area with access to greenery”

“I think green space and relaxation area is important for comfort and recovery!”

“Playground sounds great, parking for customers and proximity to nature.”

The results of the study entitled “Evaluation of spaces supporting the therapy process. A personnel perspective”, confirm the assumption that architecture influences the well-being of patients, staff and visitors. The fact that patients and visitors pay attention to, among other things, the furnishings, the overall character of the interior, and the communication layout demonstrates the importance of conscious design for the health of users. An oft-repeated phrase, “homelike atmosphere”, proves that people feel calmer and more comfortable in non-institutional spaces, despite being aware that they are in a public place. This is true for both adults and children.

The responses received significantly indicate the need for an empathetic approach to the design of the space of a mental health care centre. The needs of the child or adolescent, whose sense of security should be ensured, should be taken into account. This is influenced by the design, simplicity and ease of movement in the facility, elements of play and opportunities for contact with greenery. Cabinets, due to the variety of therapies, should be adapted to the individual needs of patients through equipment, but also decor. The staff drew attention to the positively perceived elements, i.e., drawings on the walls and tables for playing and painting. This evokes associations with play, and intrigues, and at the same time, encourages, cooperation. The interiors should evoke pleasant associations and be clear, but at the same time depart from the stereotypical image of a doctor’s office.

Equally important is the non-collision of facility functions. Group therapy rooms should not interfere with the order of individual therapy rooms. Proper location of functional blocks is one of the overriding guidelines. A patient with anxiety-related problems may feel extremely uncomfortable in a space where he/she can hear a large group of children/teenagers. Fear and anxiety will cause insecurity and will only reinforce negative reactions. The space of the mental health centre should provide a gradual stepping out of the patient’s comfort zone. This also applies to the staff area. Those surveyed emphasised the need for separate interiors for relaxation, for calming down and for talking with others. This relaxation should not be disturbed by noise from offices or waiting rooms. The therapist’s mental comfort plays a key role in the patient’s treatment process.

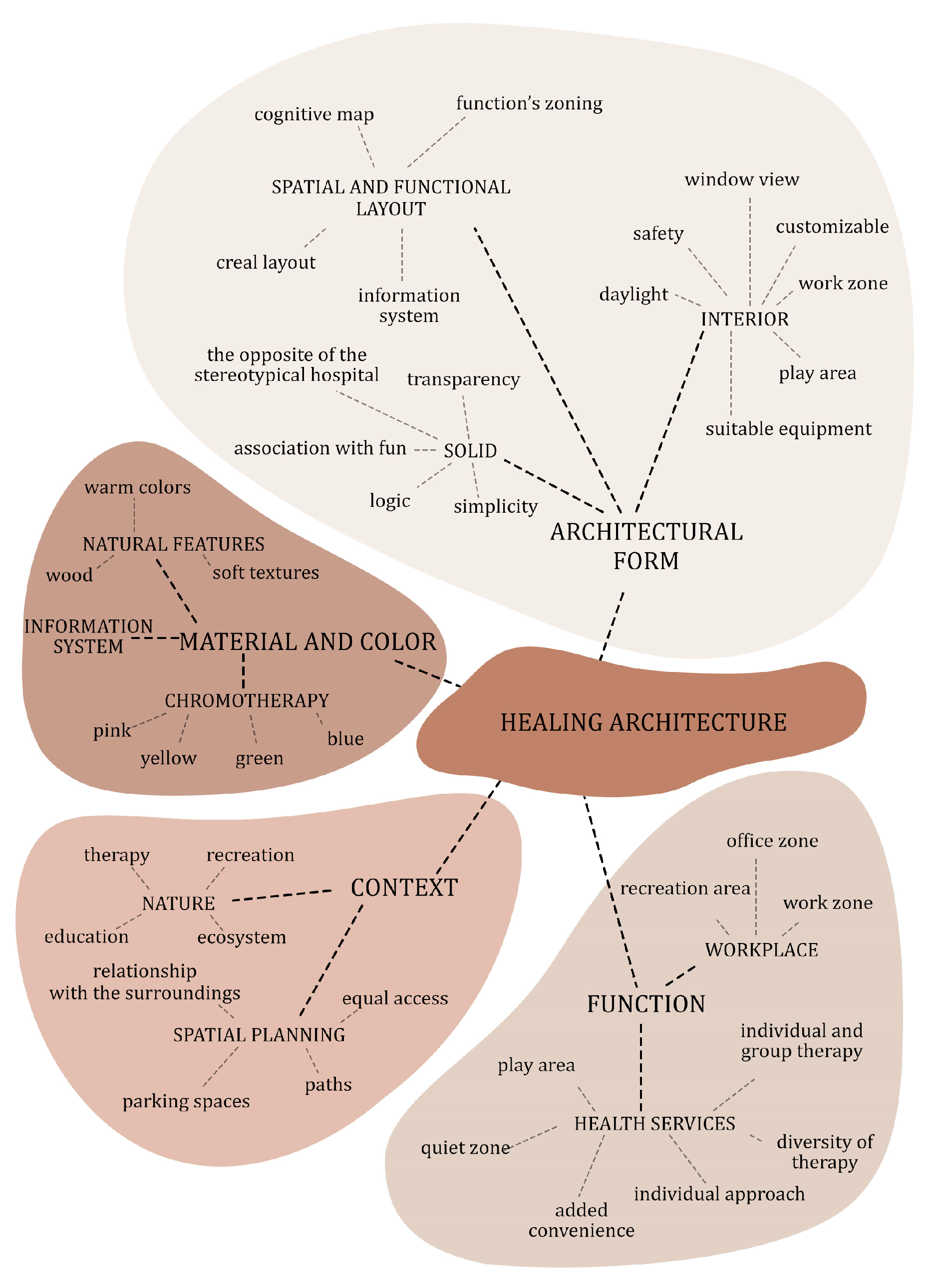

The results of the study showed that nature and contact with it is important for all users of the health care facility. For patients, it could provide an intriguing form of therapy as a job growing plants. A private green area could be an attraction for recreational reasons as a place to play. The staff also emphasised the desire for green space as a break from work. Architecture evokes various associations, thus influencing the behaviour, actions and well-being of the user. The study has noted how many design elements need to be considered in order to be able to support the patients’ healing process. Health-related architecture should be approached holistically, thought out from the choice of location to every detail of the building (see

Figure 2).

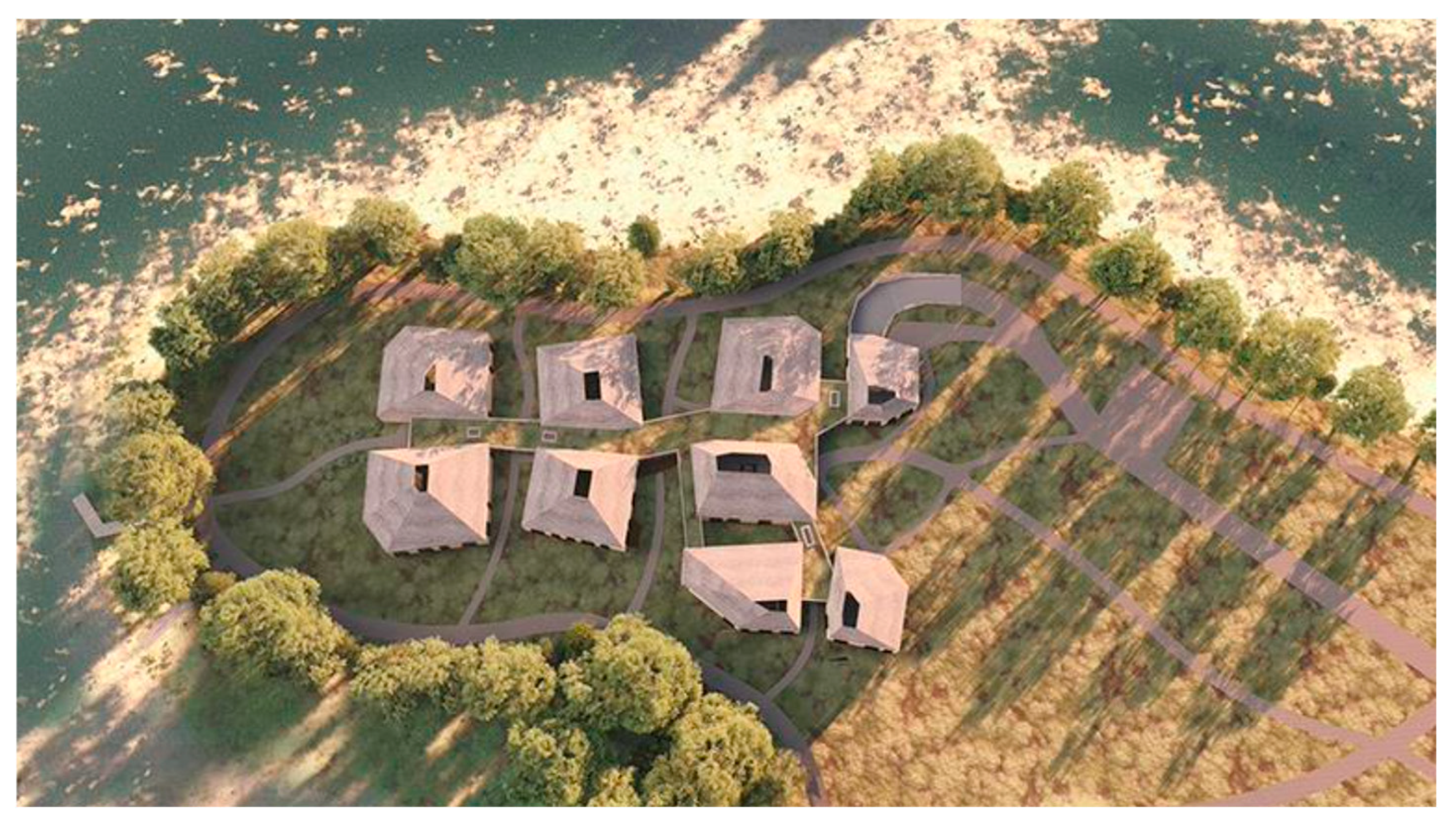

5. Health Care Architecture Model Implementation: Klodawa Clinic

As a conclusion of the research work, a design experiment was carried out to design a therapeutic centre for children and adolescents in Poland, in the town of Klodawa. The aim was to implement the research findings and design recommendations to create a qualitative therapy space. The facility consists of nine blocks with periodised functions: two group therapy blocks, two individual therapy blocks, a day ward, a dining area for the day ward, an entrance area/waiting area, a social facilities area and an administration/office block (see

Figure 3). The aim of this model is to design a mental health facility for children and young people, taking into account the influence of architecture on the therapeutic treatment process.

The main idea behind the design of the facility is to support the patient and improve his or her mental health and a sense of security. Through research into environmental architecture, color perception, shape, functional layout and the key role of greenery, it has been possible to achieve to obtain guidelines for a building which evokes friendly associations. In addition, an interview with staff at a similar facility allowed us to learn more about the needs of patients, carers and the staff themselves. The mutual comfort of those mentioned is essential to create a design geared to the well-being of each user.

The designed facility is a synthesis of the needs of young patients with neurodiversity and respect for the existing landscape. The building is symbolically reminiscent of a house drawn by a child’s hand, while at the same time providing a flow of vision, creating view openings to nature for users and visitors. The building’s form evokes associations of playfulness, joy and humour, with the aim of having a positive effect on the patient’s mind and to provide comfort and safety. The building departs from the institutional nature of the hospital, being more associated with recreational functions. The seemingly randomly scattered forms, linked by glass connectors, are in fact a compositionally planned whole, aimed at guiding the patient’s gaze, intriguing him and inviting him to explore the interior and nature around.

All cuts and shifts cause the façade to flow along the shore of Lake Klawskie, while maintaining the straight lines of the projection. All the exterior elevations invite visitors to enjoy (see

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). In addition to its visual aspect, the sloping roof also serves to illuminate the interior of the therapy rooms, creating a luminous experience.

The glass connectors, which provide bracing for the scattered solids, introduce light and frame the surrounding nature. The form of the building provides the possibility to observe the landscape from any point in the designed volume. The most accentuated frame is that of the church tower, located in the northern part of Klodawa village. This view is provided from the main corridor and visible in the entrance area of the building. Internal communication to the therapy rooms leads the patient’s gaze to this view, providing an intriguing accent.

To ensure better integration into the landscape, the functional blocks are offset from each other in such a way as to create a sense of flow and not dominate the existing landscape. The materials used for the facade are not only a reference to the historic buildings of the village of Klodawa, but also a way of blending in with the surrounding greenery. The windows, which are highly reflective, create mirrors for the trees, and the façade design in natural colours creates greater visual harmony.

The masses are single-storey, with irregular straight projections and pitched roofs. Each form has a skylight or green area. The blocks are connected by glass connecting sections with green flat roofs. Part of the building has an underground garage with 14 spaces for cars, 2 spaces for the disabled and spaces for bicycles. The main entrance is accentuated by an indentation in the body of the waiting area and covered by a green roof. In addition, a view of the historic church tower can be observed from here. The additional entrances lead to the main entrance. Additional entrances lead to, among other things, the recreation areas, the delivery area and the administrative area. The layout of the functional blocks is not random. The south-facing blocks form a foreground for the entire complex, inviting patients into the room. The waiting room is spacious and lighted with a ventilation system. In the centre, there is space for displaying the patients’ work, for playing and for relaxing and rest. In the entrance area there is, among other things, a room for diagnosis and interviews with parents/guardians.

The consultation room has been designed with the safety and psychological well-being of carers in mind. These are often difficult conversations that require adequate privacy and seclusion. From the consultation room, there is direct access to the day unit, and the close day ward consists of two functional rooms for children’s activities and a dining room with a catering kitchen. Due to different needs, two classrooms have been designed. The day care centre consists of two functional rooms for children’s activities and a dining area with kitchen and catering. Each room has a view of Lake Klawskie. The interior cutbacks are designed to increase the view of nature, but also to take the eye away from possible unwanted views (the ramp to the garage is obscured by greenery, the catering access area is not visible from the hall). Due to the nature of the work, a nursing station is located in the day ward, as well as an additional social area for staff. The large space in the central area is dedicated to play.

Four blocks on the north side of the site are dedicated to therapeutic functions. This arrangement is determined by the desire to ensure the full psychological freedom of the patients. The individual patients with their parents have the quickest access to the rooms so as to limit interaction with groups further away. Only when the child/teenager feels more confident can he/she decide to explore another part of the building, but he/she is not forced to do so. It is up to him/her to decide when he/she wants to be in a larger group. This is also comfort for the group of patients, as the family therapy parents and strangers do not move into their space and do not threaten their safety.

The group therapy blocks consist of several rooms. One of the predominant functions is the room for social skills training. The activities consist of the gradual adaptation of the patient to everyday activities that may be difficult for him or her. For this reason, the room is equipped with elements that allow such environments to be imitated. For such activities, a group of workers is needed; therefore, an additional social room is located in this part of the site. In order to provide children/teenagers with mental comfort, a quiet space is provided. Group work can be extremely tiring; therefore, a calming room is necessary.

The staff block is located to the west of the site and consists of two parts: social facilities and administration. In the first, there are locker rooms for women and men, with direct access to the toilets. The relaxation area is oriented towards the surrounding nature, which has a calming and restorative effect. In addition to the kitchen and the dining area, there is an additional room in which the staff can decide on the form of relaxation: talking, reading or sleeping. In the interests of well-being and mental health, the building has a private green area, accessible only to the staff. The administrative section consists of offices and a conference room for lectures and small meetings. The entrance to this block is from the stairwell and from the main forecourt. This way, employees have quick access to their workplaces, and potential customers/interested parties can enter the premises directly, without having to leave the building. This allows a greater sense of security to be maintained for children and teenagers who might otherwise react negatively to people who are not connected to the therapy. Each therapy block has a green courtyard that illuminates the rooms and the same information system. The greenery, which is visible both inside and outside the building, has a soothing effect on users.

The toilets, very important for young children, have been architecturally highlighted by a cut-out in the wall, making them easier to identify in each block. At the heart of the scheme is the internal circulation, whose proportions suggest its purpose. The wide corridor running along the therapeutic blocks is designed for the dynamic movement of patients. Its proportions allow it to run freely, offering a sense of comfort and easy access to the rooms. The communication routes for children and young people have been designed to ensure the quickest possible access to the halls and to provide space for recreation in case of adverse weather conditions. The material design brings dynamism to the interiors, with the aim of inviting patients to play and rejecting stagnation. The design is intended to evoke friendly associations.

Communication has been designed with patients and staff in mind. The proportions and location of the corridors suggest which areas are intended for use by staff or patients. The two smaller entrances, which are not exposed, are used for staff mobility. The access to the social facilities and the administrative area is located outside the main entrance and directly from the underground garage. In addition, therapists and psychologists have direct access to the main corridor, so that their path does not interfere with the waiting area. The aim of this is to ensure greater working comfort.

6. Discussion

The built environment has a huge impact on well-being. Appropriate design decisions can contribute to the effectiveness of therapy. Conscious design of the environment can alleviate negative feelings and enhance feelings of security and calm, which are prerequisites for therapy [

17]. A study conducted at a British hospital in Poole showed that patients located in a renovated, more adequately designed ward needed less pain medication and spent 21% less time in the facility compared to patients in an older, more conventional ward from the 1960s. In an era of developing public awareness of mental health issues, it is important to consider the facilities themselves that provide such services. A modern health care facility should be equipped with modern technology, which involves specific design procedures. At the same time, such a facility must be designed with the well-being of patients and staff in mind, creating comfortable interiors and well-thought-out spatial-functional connections [

18].

Psychological help facilities often evoke negative associations as a place of isolation and exclusion. Such perceptions already affect the effectiveness of the patient’s therapy. If a person does not receive adequate support while not changing his or her thinking about such places, he or she will have a negative attitude toward cooperation with doctors. In the case of young patients, often unaware of the reasons and consequences of attending therapy, the willingness to work is particularly necessary in the treatment process.

The architecture of mental health centres should minimise the impact of stressors. When designing a health care facility, it is important to understand how the patient group functions and how they react to various stimuli in order to increase their well-being, but also their safety. At the same time, the facility, from the outside, should evoke pleasant associations, unrelated to the institutional appearance of health care facilities. The architectural form itself already plays a key role in creating positive patient attitudes. In his book, Augustyn Banka cited the observations of R.G. Allen, who, on the basis of his research, drew conclusions about the influence of form on the mental state of a person: “Mental tensions can be caused by:

- -

too dynamic or unbalanced composition,

- -

use of large scale and extreme contrasts,

- -

introduction of contrasting colors and strongly emphasised corner forms,

- -

accentuation of unfamiliar elements in unfamiliar surroundings.

A relaxing sensation, i.e., a slight stimulation combined with considerable pleasure, can be induced by:

- -

introducing familiar and well-liked elements (flowers, greenery, aquariums),

- -

maintaining order in the environment and freedom of movement in the spaces,

- -

using elements in a small or accessible scale,

- -

not using strong contrasts, but introducing soft, flowing forms of space, soft light and similar colors,

- -

use of music (pleasant and soft sounds),

- -

maintaining a comfortable microclimate for humans.

The feeling of satisfaction from being in a given space can be achieved by:

- -

the use of fluid forms,

- -

juxtaposition of large and small forms on a scale that is understandable to humans,

- -

Introducing dynamic elements into the interior of the space, giving the feeling of movement or completely moving,

- -

various use of rhythms,

- -

design of individual objects showing familiar, comprehensible ideas (e.g., expressionism, functionalism, symbolism).

Anxiety states (high arousal with low pleasure and high feelings of subjection and submission) can be induced by:

- -

spaces created from elements of incomprehensible dimensions, giving the impression of being unstable and sometimes dangerous,

- -

complex forms and labyrinth-type spaces,

- -

illegible use of large scales and extreme contrasts,

- -

design of spaces insufficiently illuminated or illuminated with cold light, contrasting poorly lit rooms with dazzlingly bright and emphasised spaces,

- -

introduction of rhythmically shifting shadow play,

- -

Architects, through design, can contribute to raising the standard of living of people with disorders. Appropriate techniques and solutions have an impact on alleviating stress, minimising negative stimuli and increasing comfort and safety. A relatively new area of research is neurodiversity. It is a field that assumes that each person has a different brain, and thus, different cognitive dispositions. A child or adolescent with different cognitive abilities will react differently to the same interiors, objects and elements of the built environment. In the case of design aimed at therapeutic assistance, this fact of dissimilarity is extremely important. The key issue is to know how the environment is perceived by specific groups of patients. The development of the space around the facility is also an important aspect in designing for patients. The environment should offer places for multi-patient encounters, but also places to catch your breath, calm down, and gather your thoughts.

An architectural object has many components: form, inter-relationships, interiors, functions and materials. Their influence on user perception is simultaneous as well as independent. A healthy person perceives the built environment differently than a patient with a disorder. For a healthy user, a provocative or aggressive form may intrigue, encourage a deeper understanding of the object’s function, while for a user with neurodiversity, illogical solutions or inadequately used forms evoke negative emotions.

There are limitations to the research that has been carried out that the authors have encountered.

Conducting in situ participatory research in health facilities is difficult due to limited access. Each time a patient or staff member is interviewed, knowledge of procedures and permissions are required. As a result, the research sample is usually smaller than in other studies.

In addition, Polish legislation on the design of health care facilities is not very detailed. As a result, there are large differences between hospital facilities. It is therefore important to conduct systematic research in as many health care facilities as possible and to develop the study with further findings. Further extension of the study to other centres is envisaged. Ultimately, it will be important to compare the staff evaluation with the staff evaluation on a larger scale of the study and on the basis of a larger data set [

18].