1. Introduction

As universities continue to develop, increasing emphasis is being placed on the construction of campus culture. Campus culture is not only reflected in the academic atmosphere and educational philosophy but also includes the history, spirit, and traditions of the institution. Nowadays, universities often play an important role in the dissemination of university culture, particularly through the organization, presentation, and promotion of their history and heritage. In Chinese universities, the construction and operation of university history museums have gradually become a key function of university archives. In fact, university history museums have become a distinctive cultural space commonly found on Chinese campuses, serving as a reflection and microcosm of a university’s historical development, with fundamental characteristics of both historicity and exhibition [

1]. However, due to differences in the expression of university history and culture, universities in Europe and the United States typically do not have independent university history museums. Instead, Chinese universities have dedicated spaces on campus to showcase their history, often through unique formats such as museums. These spaces present university culture while conveying societal values [

2,

3,

4]. The question of how to truly maximize the value of university museums has become increasingly important [

5].

From a macro perspective, university museums can also be considered a type of landscape. The senses play a crucial role in shaping the relationship between people and their environment, creating a comprehensive system for gathering knowledge and understanding [

6,

7]. Beauty is perceived through visual receptors, and the experience of esthetic pleasure largely depends on the response of these receptors to external stimuli. It is through the capture of visual sensations that people are able to appreciate the diverse beauty found in nature, art, and other forms [

8]. Research on landscape perception and visual evaluation mainly focuses on two aspects: “cognition” and “sensation”. These can be explored through visualization assessment platforms [

9], three-dimensional (3D) models [

10], and 3S (remote sensing, geographic information systems, and global positioning systems) technologies [

11]. In addition, narrative landscape design is an effective means of showcasing unique characteristics. It involves using natural and cultural landscapes to narrate one or more stories, expressing the landscape in a storytelling format. Based on narrative text, this approach employs various narrative techniques in landscape design to tell a cohesive story [

12].

Landscapes encompass not only visually identifiable natural and artificial elements but also non-visual aspects such as ecological functions, historical and cultural values, and recreational benefits, as well as olfactory and gustatory experiences [

13]. Existing research has shown a close relationship between the perception of soundscapes in urban public spaces, landscape perception, and visitor experience [

14,

15,

16]. Over time, with the development of society, people are no longer satisfied with purely visually centered landscapes [

17,

18]. The concept of multisensory landscapes has emerged, integrating visual, tactile, olfactory, auditory, and gustatory experiences [

19,

20]. Compared to the studies on visual landscapes and auditory environments, research on olfaction is relatively scarce [

21]. The human olfactory system comprises hundreds of different olfactory receptors, allowing it to distinguish between a far greater number of physically different stimuli than any other sense [

22]. In the course of human evolution, the sense of smell has been crucial for survival, as it allows individuals to detect danger or safety. This sense emits signals that trigger instinctual and subconscious responses [

23]. Olfactory perception encompasses several key factors, including scent characteristics, environmental influences, and individual factors [

24]. When considering living spaces and daily environments, the quality of the olfactory environment is psychologically significant, as it can influence subjective evaluations and physiological assessments [

25,

26]. Therefore, research on smellscapes may help us understand the relationship between perceptual processes and overall well-being [

27].

Smellscapes have received widespread attention in recent years. The concept of smellscape is central to the study and exploration of the overall smell experience of a place. It was initially proposed by Porteous in 1985 [

28], based on Schafer’s concept of soundscapes from 1977 [

29]. It refers to the olfactory environment perceived and understood by individuals, influenced by their memories and past experiences, as it relates specifically to their surroundings [

30]. Henshaw expands on Porteous’s definition of smellscapes by describing it as the overall olfactory environment, while acknowledging that as humans, we can only partially detect this at any given moment, even though we may retain an image or memory of the smellscape as a whole in our minds [

24].

The smellscape can evoke the public’s olfactory enthusiasm and create a more harmonious olfactory environment, eliciting strong emotional responses [

31]. Pleasant scents have the potential to enhance feelings of happiness and comfort, typically contributing to improved overall health outcomes. This includes benefits for mental health, physical health, reducing agitation, enhancing cognitive function, and increasing overall well-being [

32,

33]. It is important to note that smell is a complex, holistic experience, making it difficult to convey. Describing the situations in which people encounter a particular scent is often easier than naming the scent itself. This implies that, to describe olfaction and scent, it is more effective to contextualize them within specific scenarios. To perceive scent narratives means engaging with and experiencing stories about a place and its relation to others. Smellscape has been recognized in the field of landscape architecture, and case studies provide valuable insights into the integration of smellscape in modern garden design [

34,

35]. University museums typically showcase items and records related to the institution’s history, significant figures, or events. By introducing scents associated with exhibits or historical events, visitors can experience a deeper connection to the historical context. Scent, as a medium for creating a multisensory experience in museums, enhances the overall scene. Scent-focused exhibition layouts promote physical interaction, touch, navigation, and engagement [

36]. In recent years, the application of olfaction in museums has been gradually gaining popularity and has received support from professionals [

37]. Verbeek et al. reported on the development of the scented tours at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam (2015–2020), exploring different olfactory storytelling approaches and scent distribution techniques [

38]. The Mauritshuis Royal Picture Gallery in the Netherlands, the Van Abbemuseum of Modern Art, and the Ulm Museum have all held olfactory exhibitions [

38,

39]. These exhibitions have all highlighted the impact of olfaction on visitors’ emotions and memory: “Scents has a direct impact on our emotions and penetrates the deepest layers of our (sub)consciousness”. However, the effectiveness of smellscapes in university history museums has not yet been established. In addition, the evaluation of the impact of smellscapes on landscape perception remains inconclusive.

In addition, with the rapid advancement of evaluations of cultural buildings such as museums, their emotional impact on individuals has become increasingly important [

40], even surpassing the artistic aspects of the architecture. Smellscapes play a crucial role in this development. Therefore, this study aims to explore the effectiveness of smellscapes in university history museums and assess their impact on visitors’ emotions, perception of historical narratives, and other related aspects. By exploring the suitability of scent narratives with campus historical settings, this study investigates the importance of emotions in the evaluation of smellscapes, providing a theoretical foundation and practical reference for the application of smellscapes in future museum exhibit designs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Framework

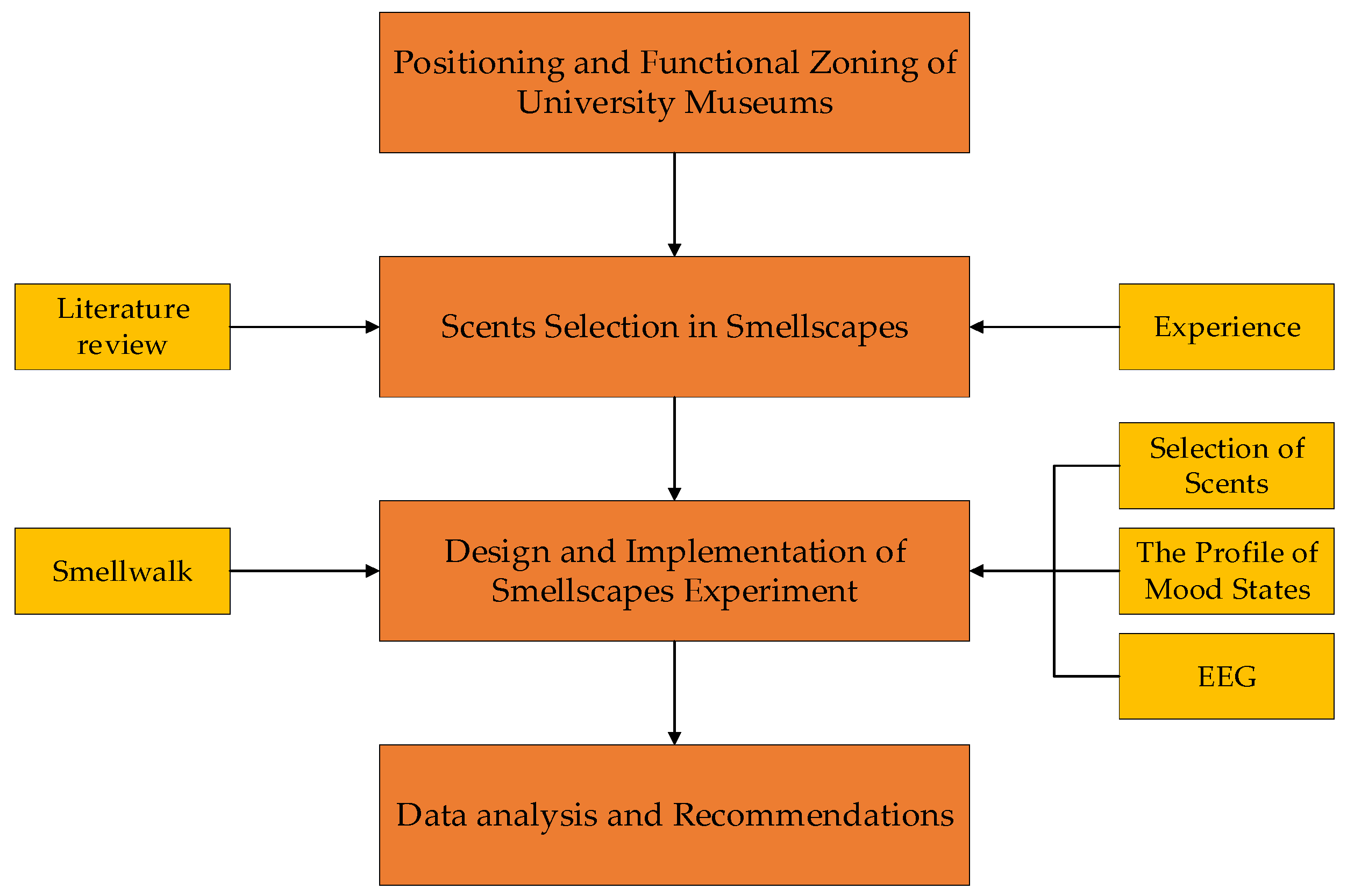

This study aims to investigate the effectiveness of olfactory landscapes in the context of university museums. The overall framework, as shown in

Figure 1, is divided into five stages. The first stage involves partitioning the university museum based on exhibition content. The second stage focuses on the selection of scents within the olfactory landscape. The third stage consists of olfactory experiments based on EEG and questionnaires. The fourth stage involves data analysis and the formulation of recommendations for setting up olfactory landscapes in university museums to enhance their cultural transmission role.

2.2. Study Area

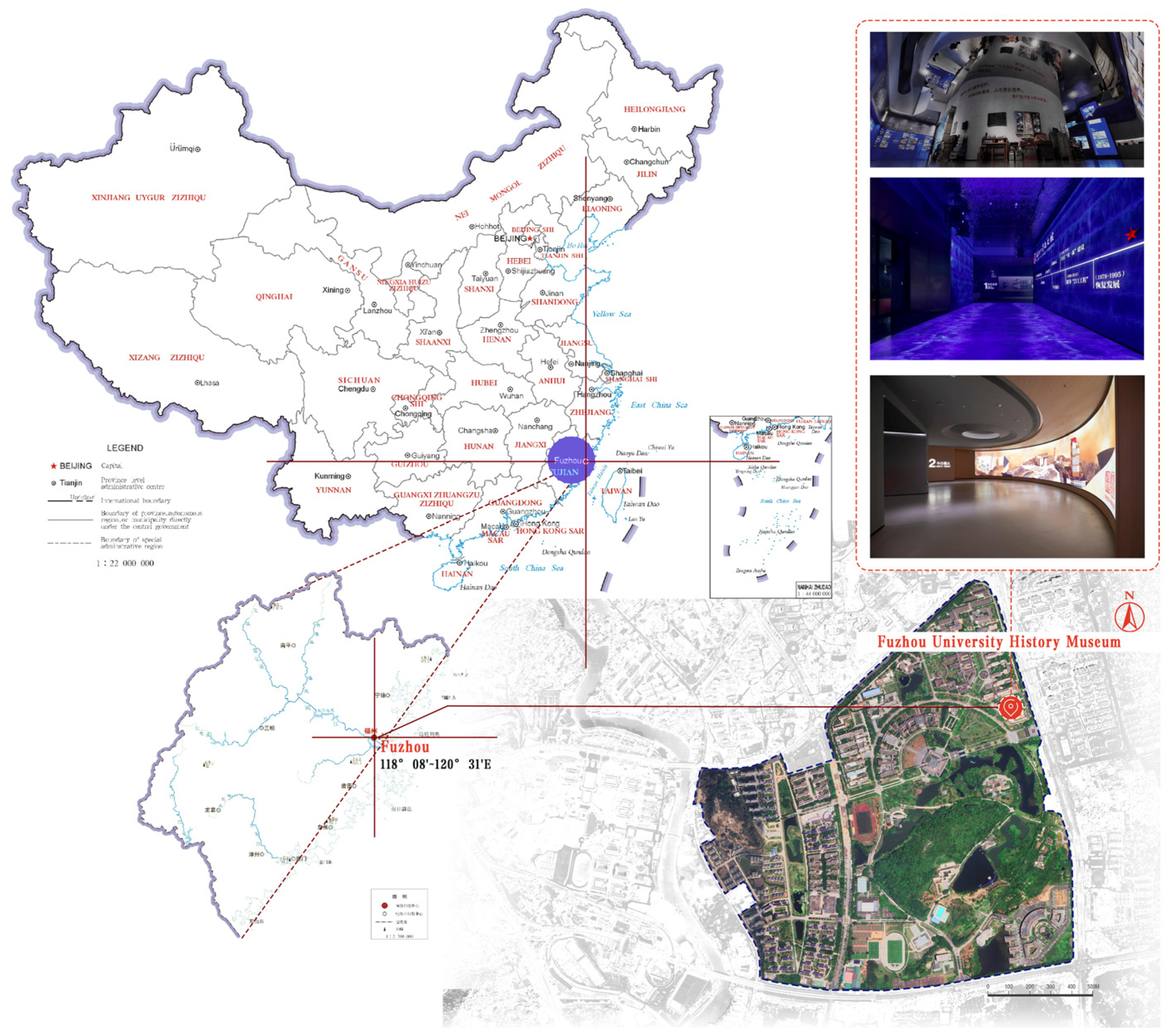

Fuzhou, the capital of Fujian Province in China, is located on the southeastern Chinese coast at the lower reaches of the Min River. It is a city with a long history and rich culture, serving as one of the political, economic, cultural, and transportation centers of Fujian Province (situated between latitudes 25°15′ and 26°39′ N, and longitudes 118°08′ and 120°31′ E) (

Figure 2). Fuzhou University is one of the key high-level universities in Fujian Province and a representative institution of higher education in Fuzhou. The university’s history museum, designed around the concept of “Pili Lanyu · Changhe Juan”, interprets the three spirits of Fuzhou University through the context of the river of time, showcasing the past, present, and future of the university.

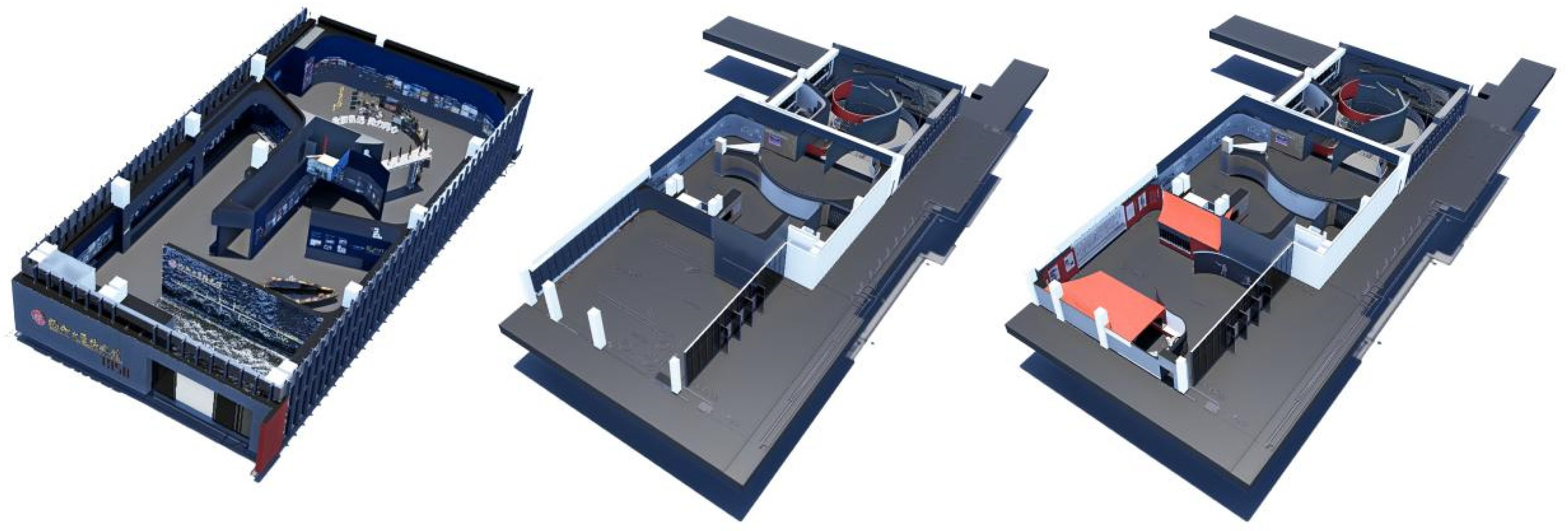

The Fuzhou University History Museum is divided into three main areas: the Historical Evolution Zone (HEZ), the Contemporary Development Zone (CDZ), and the Thematic Exhibition Zone (TEZ) (

Figure 3). The first floor of the museum features the HEZ, which narrates the entire journey from the university’s founding in 1958 to 2023. The overall space is composed of twisted straight lines and diagonal lines, creating a sense of difficulty reflected in the layered gaps of the walls. A series of physical exhibits are set up in the space, showcasing the old university gate juxtaposed with the seven current campuses, along with mirrored elements to evoke a sense of temporal and spatial intersection. Fuzhou University has faced many challenges throughout its historical evolution, and the overall spatial design adopts a deep blue tone, complemented by white and gray, representing the passionate struggle and romantic ideals during its challenging founding period. The CDZ showcases the prosperity of Fuzhou University today, utilizing a design that merges straight and curved forms, symbolizing the remarkable achievements the university has attained. This area specifically conveys a sense of stability and calm emotions. In the TEZ, a vibrant red serves as the main color, representing the spirit of perseverance and striving for excellence. The spatial design here reflects positive and uplifting emotional experiences.

2.3. Experimental Design

2.3.1. Smellscape Design

University history museums are important venues for showcasing the history, culture, and achievements of higher education institutions. They typically consist of multiple functional areas, including historical evolution, current development, thematic exhibitions, and future outlooks. The integration of scents within these exhibition areas can evoke emotional resonance and a sense of belonging among visitors. In different exhibition zones, the unique scents of various plants play a distinctive role, enhancing the overall experience and engagement of the audience. When the scents are aligned with the exhibition themes, visitors tend to spend more time exploring and appreciating the artworks [

41].

In the HEZ, scents should help visitors enter a state of contemplation, nostalgia, and reminiscence, evoking a sense of historical depth and cultural atmosphere. Compared to aromatic plants, woody and herbal scents are more suitable for this historical context, providing an experience that feels more historically rich and tranquil. Woody scents typically possess deep, natural, and serene characteristics that can evoke associations with the past, particularly related to exhibits on historical culture [

42]. These scents can create a sense of antiquity, stability, and solemnity for visitors, enhancing the cultural weight of the historical evolution area [

43]. Sandalwood, with its distant woody aroma, can facilitate a reflective and introspective emotional state, making it particularly fitting for showcasing the continuity of historical development and cultural heritage. Herbal scents, on the other hand, tend to be milder, with a natural freshness and stable presence that can evoke nostalgic and tranquil associations with historical scenes. This is especially true for historical content closely related to traditional lifestyles and natural environments, where herbal scents can enhance visitors’ historical experiences. Sage, with its herbal fragrance and subtle bitterness, is suitable for the historical evolution area, helping visitors sense the fusion of nature and history within the exhibition.

Aromatic plants typically possess fresh, natural, and soothing scents that can evoke emotional effects such as relaxation, pleasure, and increased attention [

44]. Research has shown that the olfactory properties of essential oils such as lavender, rosemary, and chamomile have a positive impact on emotions and objective cognitive performance [

45,

46]. These aromatic plants are particularly suitable for the CDZ, because their refreshing qualities can enhance visitors’ attention and mood, creating a positive and vibrant atmosphere. The displays of modern development often convey a sense of innovation, progress, and futurism, and the scents of aromatic plants, such as mint, lemongrass, and rosemary, can help visitors focus and experience the energy and modernity inherent in the exhibits.

In the TEZ (Future Outlook), the displayed themes typically involve innovation, technology, progress, and hope. To create a positive, refreshing, and inspiring atmosphere, the selection of plant scents should evoke vigor, clarity, and positive emotions. Suitable plant aromas should convey hope, upliftment, and a forward-looking perspective, instilling a sense of anticipation for the future among visitors [

47]. Citrus plant scents are fresh and lively, known for enhancing mood and increasing concentration, making them ideal for creating an energetic and optimistic atmosphere in the exhibition area. The bright citrus aroma of orange blossom can stimulate feelings of joy and excitement, conveying optimism and positive energy, which is perfect for showcasing future innovations and development prospects. Herbaceous scents possess warm and soothing characteristics, providing comfort and a sense of safety to the future exhibition area while conveying a stable sense of progress. Vetiver, with its fresh and grounded herbal scent, can cultivate a calm yet hopeful ambiance, suitable for illustrating future sustainable development and steady advancement. Mint plants offer refreshing and invigorating qualities, capable of awakening mental alertness and clarity, which is fitting for conveying the future vision of innovation and technological advancement. Patchouli has a gentle freshness that conveys a sense of nature, modernity, and technology, helping to shape a forward-looking atmosphere for future development.

Based on this, we set up 12 experimental scenarios for three typical exhibition areas of the Fuzhou University History Museum and conducted indoor experiments (

Table 1).

2.3.2. Smellwalk

Smellwalk is a term that refers to a sensory exploration technique that combines walking with the engagement of olfactory experiences. This method encourages participants to be aware of the smells in their environment while they walk, allowing them to connect their sensory perceptions with their spatial experiences [

7]. To validate the impact of the integration of scents with the various exhibition areas of the university history museum on visitors’ emotions and cognition, we designed a walking interview experiment to collect qualitative data. In this experiment, participants were selected to enter the university history museum and experience the authentic smellscape while engaging with each section of the exhibition (

Figure 4). Real-time interviews were conducted during their visit. The interview questions were primarily non-leading to ensure that the participants’ natural responses were not influenced. The key interview questions included the following: (1) Did you notice any changes in scent? (2) Did you believe this scent is consistent with the theme or atmosphere of the current exhibition area? (3) Did the scent have any effect on your emotions or memory?

2.4. Experimental Equipment and Materials

2.4.1. Experimental Equipment

- (1)

Olfactory Diffusion Equipment

The olfactory diffusion equipment utilizes a nebulizer to atomize naturally extracted essential oils or fragrances into fine particles, ensuring an even distribution in the air. By precisely adjusting the concentration, diffusion rate, and release time of the scents, we can ensure that different scents do not excessively mix during the experiment, thus maintaining their individual integrity and purity. Throughout the experiment, we controlled the concentration of the scents, the timing of their release, and the diffusion rate.

- (2)

32-Channel NE Wireless EEG System

The 32-channel NE wireless EEG system is a wearable wireless EEG system that offers high resolution and a sampling rate of 500 sample per second (SPS), providing excellent data accuracy. When used in conjunction with the NE wireless EEG system, it allows for real-time monitoring of the subjects’ brain waves. Software such as MATLAB R2020b can be utilized to perform wavelet analysis, event related potentials (ERP) analysis, and other data processing techniques, enabling the acquisition of EEG signal data and visualizations of brain waveforms.

2.4.2. Experimental Materials

- (1)

Landscape Video

To ensure that the video effectively conveys the core content and emotional atmosphere of the university history museum, we conducted on-site video recordings at the museum. First, we designed a shooting route based on the museum’s layout, covering key areas such as historical evolution, current developments, and future outlooks. During the shooting process, we used steady camera work to reflect the calmness of the HEZ, while incorporating dynamic shots in the TEZ to showcase innovation and progress. We paid careful attention to lighting to ensure that exhibits and texts were clearly visible, capturing details from multiple angles so that visitors could fully experience the content within the museum. In post-production editing, we integrated a clear narrative thread using historical timelines or significant events, adding background music or audio commentary to further enhance emotional resonance. Ultimately, this process provides high-quality visual material for the study of smellscape.

- (2)

Emotional Assessment Questionnaire

The Profile of Mood States (POMS) questionnaire [

48] is used to assess the emotional and mood states of participants, with higher factor scores indicating more intense emotions. This scale has been found to have good reliability and validity and is widely used in research. The questionnaire consists of 40 items, covering five negative emotion factors—tension, anger, fatigue, depression, and confusion—and two positive factors—vigor and self-esteem. A five-point Likert scale (0–4) is used for scoring. The Total Mood Disturbance (TMD) score is calculated from these seven emotional factors using the following formula: TMD = tension + anger + depression + fatigue − vigor + confusion − self-esteem + 100. A higher TMD score indicates more negative emotional states, suggesting a more negative and troubled mood. Conversely, a lower TMD score reflects a more stable emotional state. The TMD score was chosen as the measure for subjective emotional assessment in this study.

- (3)

The Olfactory Pleasure Rating Scale

The pleasure of smellscapes refers to the overall subjective experience and positive emotional response people have towards scents in specific environments or settings [

49]. It assesses how pleasant an individual finds a scent, often associated with their emotional state, comfort, relaxation, and other positive emotions. Scents with higher pleasure ratings tend to reduce negative emotions like stress and anxiety, promote positive feelings, and enhance the overall experience of the environment. The 9-point pleasure rating scale is used to evaluate a person’s psychological response to inhaled scents, ranging from “extremely unpleasant”, “very unpleasant”, “unpleasant”, “slightly unpleasant”, “neutral”, “slightly pleasant”, “pleasant”, “very pleasant”, to “extremely pleasant”, corresponding to scores from 1 to 9.

2.5. Participants

The study aims to explore the impact of different combinations of scents and landscape styles on visitors’ emotional states and memory performance. A within-subjects experimental design was employed, focusing on a single factor. A statistical power analysis was conducted using G*Power software [

50], considering a medium effect size between scents and landscape styles (f = 0.25), a significance level of α = 0.05, and a desired statistical power of 0.80. The results of the analysis indicated that a minimum of 28 participants would be required for the study.

Participants were recruited through university email lists, social media platforms, campus bulletin boards, and classroom announcements. Interested individuals signed up via an online registration form, and all participants who completed the study received compensation totaling USD 15. To ensure the validity of the study, specific inclusion and exclusion criteria were established. Inclusion criteria required participants to be between the ages of 18 and 30 and to have normal olfactory function, while exclusion criteria included individuals allergic to the study scents or those with neurological or psychological disorders. A total of 32 participants successfully completed the experiment, with a balanced gender distribution of 50% male and 50% female. Age distribution showed that 50% were aged 18–22, 31.25% were aged 23–26, and 18.75% were aged 27–35. In terms of educational background, 56.25% were undergraduate students, 28.125% were graduate students, and 15.625% were faculty members. The study was approved by the University Human Research Ethics Committee, and participants signed informed consent forms, understanding the purpose and potential risks of the study. All data were anonymized to protect participants’ privacy, and they were allowed to withdraw from the study at any time without penalty.

2.6. Experimental Indicators

2.6.1. EEG Indicators

- (1)

Valence: Valence refers to the participant’s positive or negative attitude toward an event [

51]. It is calculated based on frontal lobe activity, using the following formula: α(F4)/β(F4) − α(F3)/β(F3), where α(F4) represents the α power spectral density (PSD) of the F4 channel.

- (2)

Arousal: Arousal refers to whether participants are in an activated state [

52]. It is characterized by consistently high β wave activity and low α wave activity in the parietal region. The calculation formula is as follows: α(AF3 + AF4 + F3 + F4)/β(AF3 + AF4 + F3 + F4), where α(F4) represents the α PSD of the F4 channel.

2.6.2. Mood and Pleasure Indicators

- (1)

Smell pleasantness

In the design of smellscapes, pleasure is a key evaluation indicator, especially in environments such as exhibition spaces, museums, or public areas. The use of scent can subtly influence the psychological and emotional responses of visitors or users. By selecting scents that enhance pleasure, it is possible to optimize the user’s experience and improve their perception of the environment.

- (2)

TMD scores

A higher TMD value indicates a greater presence of negative emotional states, suggesting a more negative and distressed mood. Conversely, a lower TMD score reflects a more stable emotional state [

53]. Therefore, in this study, we chose TMD values as the measure of subjective emotions.

2.7. Procedure

This study aimed to investigate the effectiveness of smellscape in university history museums. First, the experimental environment was established by dividing the museum into three areas—the HEZ, the CDZ, and the TEZ—while controlling variables such as lighting, temperature, and noise. Next, olfactory diffusion devices were configured, and suitable scents (such as sage, sandalwood, agarwood, lemongrass, rosemary, mint, patchouli, orange blossom, and vetiver) were selected for preparation. Then, eligible participants were recruited to experience specific scents or a control group without scents in different areas. During the scent release, participants viewed the exhibition content. After the experiment, participants filled out emotional questionnaires and scent pleasantness scales to assess their emotional states, while EEG monitoring devices recorded brainwave data. Finally, questionnaire and EEG data were collected and analyzed using the statistical software SPSS to explore the impact of different scents on participants’ emotions. Based on the experimental results, on-site walking interviews were conducted in the history museum to verify the feasibility and implementability of the experimental findings.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 presents the valence, arousal, pleasantness of scent, and TMD scores of visitors under no odor conditions across different exhibition areas. From the data, the TEZ had the highest valence score (1.30) and pleasantness of odor score (4.78), indicating that visitors experience a more positive and enjoyable time in this area. In contrast, the HEZ had a negative valence (−0.42), the lowest pleasantness of odor score (4.41), and the highest TMD score (121.59), suggesting that visitors feel relatively more negative emotions in this region. These differences may stem from the relationship between the attractiveness of the content displayed in different areas and visitors’ subjective experiences. The content in the TEZ may be more engaging and interactive, significantly enhancing visitors’ sense of enjoyment while reducing negative emotions. Conversely, the content in the HEZ might be more serious or information-heavy, leading visitors to experience more negative emotions and fatigue, ultimately impacting their overall experience.

3.2. Valence

Valence in smellscapes holds significant value, as it can markedly enhance the emotional responses and overall experiences of the audience. By selecting scents with positive valence, a pleasant atmosphere can be created, fostering positive emotions among visitors and facilitating a deeper emotional resonance with the content of the exhibition areas. Scents not only help regulate emotional states but also promote behavioral engagement through their positive valence, leading to longer visit durations and higher interaction levels in specific spaces. Additionally, the close relationship between scent and memory means that positively valenced scents can help improve visitors’ retention and understanding of exhibition content, which is especially important in educational displays and museum settings. By cleverly integrating valence into landscape narratives, more engaging and interactive spaces can be created. An analysis of the smellscapes in the HEZ, CDZ, and TEZ revealed that different combinations of scents significantly affect human emotions (p < 0.001).

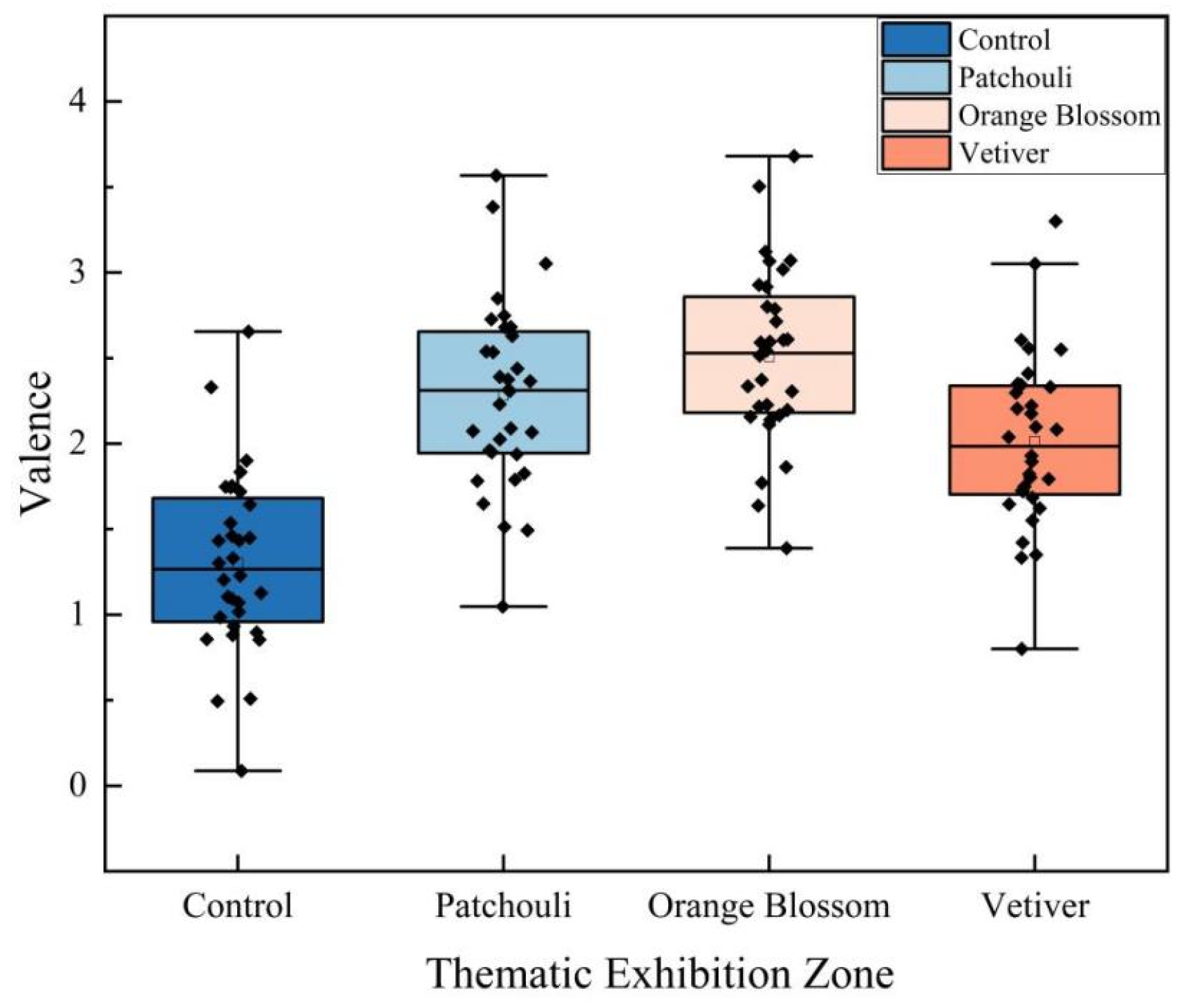

In the HEZ, scents should help visitors enter a state of reflection, nostalgia, and memory, infused with a sense of historical weight and cultural atmosphere. Compared to aromatic plants, woody and herbal scents are more suitable for this historical context, providing a more profound sense of history and a tranquil atmosphere. Our findings revealed significant differences in valence produced by different scents (F(3, 124) = 17.607,

p < 0.001, η

2 = 0.299). Overall, in the HEZ, visitors’ valence tended toward heaviness, accompanied by a touch of melancholy, resulting in lower valence scores (

Figure 5). Relative to the scentless landscape, sandalwood, and sage significantly enhanced positive valence by 70% and 190%, respectively, while agarwood decreased it by 47%. Among these, the combination of sandalwood and the HEZ leads to a more positive emotional state for visitors. The warm aroma of sandalwood tends to evoke feelings of pleasure, tranquility, and comfort, making visitors feel calm and content. Conversely, agarwood can evoke nostalgia, reverence, and a sense of gravity, helping visitors appreciate the weight of history and the profound impacts of historical processes. This results in a heavier emotional experience in the HEZ, yielding a lower valence compared to the scentless condition, yet it still effectively reflects the spirit conveyed by this area.

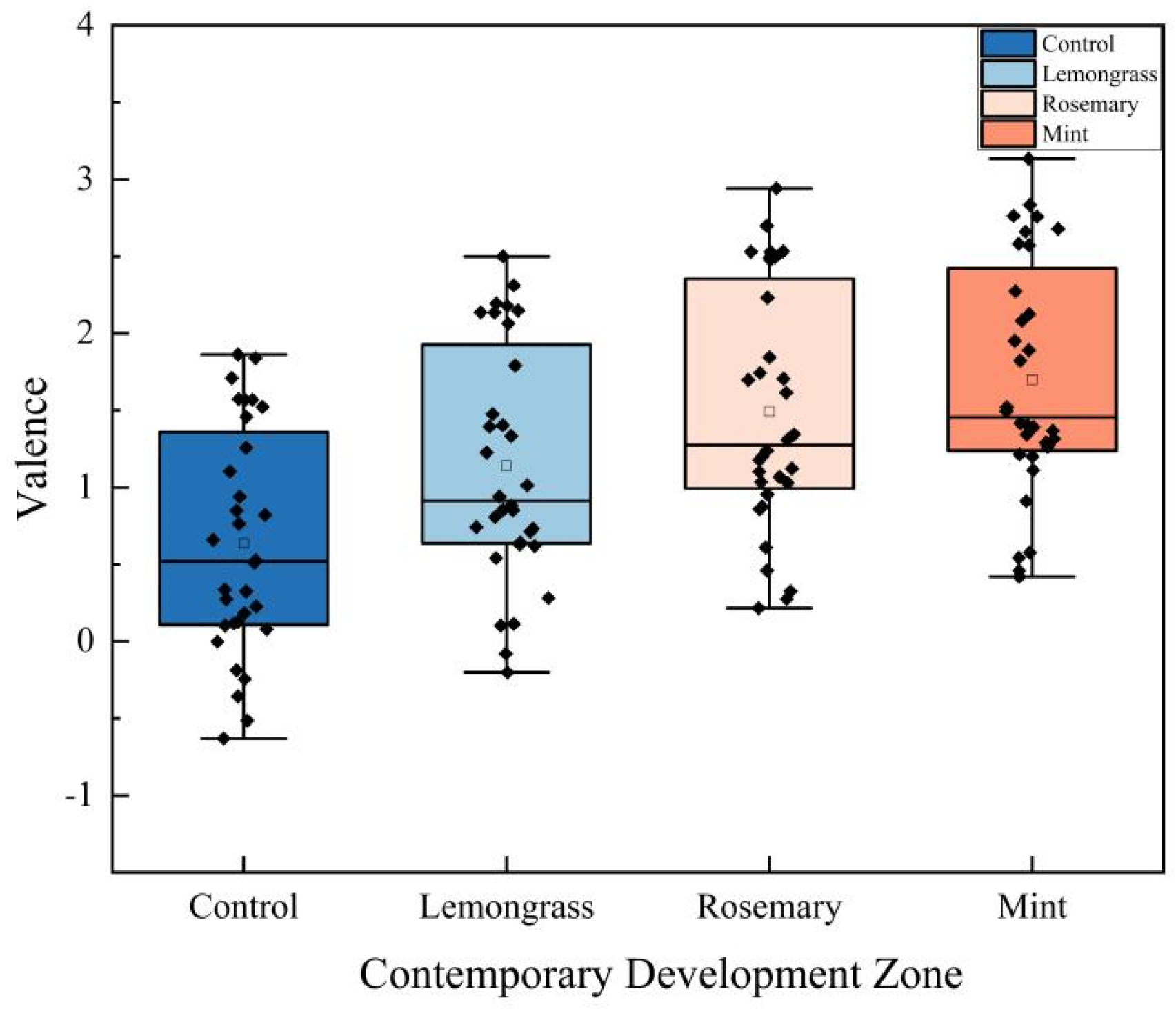

In the CDZ, there were significant differences in the valence produced by different scents (F(3, 124) = 11.896,

p < 0.001, η

2 = 0.223). As shown in the figure, aromatic plants enhance the valence for visitors in this area. Specifically, mint and rosemary had a notable enhancement effect, increasing valence by 167% and 134%, respectively, while lemongrass only showed a 79% increase (

Figure 6). This is because the CDZ typically emphasizes modernization, progress, innovation, and vigor, and aromatic plants can promote positive emotions, enhance focus, and stimulate energy. Mint is closely associated with freshness, vigor, and invigoration. Visitors in a mint-scented environment often feel pleasant and refreshed, which helps elevate positive emotions.

In the TEZ, the valence produced by the odors showed significant differences (F(3, 124) = 32.009,

p < 0.001, η

2 = 0.436). As shown in

Figure 7, the combination of smellscapes can effectively enhance visitors’ valence. Among them, orange blossom had the greatest impact on participants’ valence, increasing it by 93%, while patchouli boosted it by 75%, and vetiver only enhanced it by 55%. This indicates that citrus scents are more effective for the TEZ. In contrast, the earthy and deep aroma of vetiver is closely associated with stability and profound emotions, making it more suitable for creating a grounded and contemplative atmosphere in the future outlook area. Therefore, its effect on enhancing valence is relatively lower.

3.3. Arousal

The application value of arousal in smellscapes is reflected in its multiple impacts on spatial atmosphere, emotional regulation, and information processing. By introducing scents with varying arousal levels, the immersive quality of a space can be enhanced, and the physiological and psychological states of visitors can be adjusted. This approach stimulates visitors’ creativity and vigor. Furthermore, arousal levels are closely related to memory formation and information processing; moderate arousal can enhance visitors’ memory of the exhibit content, thus improving the educational and communicative effects of the exhibition. Therefore, by modulating the arousal effects of scents, it is possible to effectively guide visitors’ emotional responses and memory experiences, achieving a profound resonance between space and emotion. An analysis of the smellscapes in the HEZ, CDZ, and TEZ demonstrated that scent combinations can significantly influence human emotions.

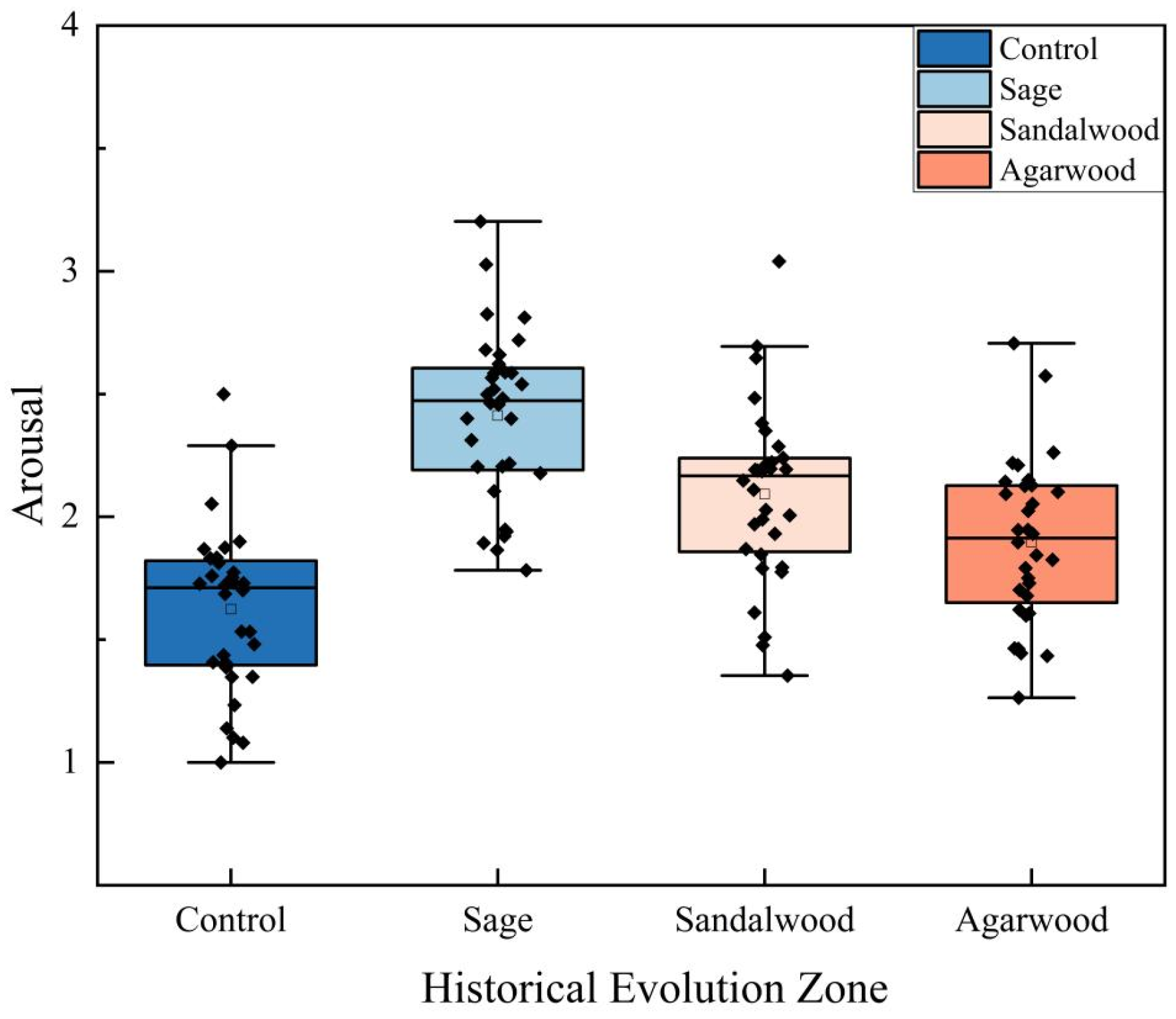

In the HEZ, the arousal effects of different scents exhibited significant differences during historical changes (F(3, 124) = 29.853,

p < 0.001, η

2 = 0.419). As illustrated in

Figure 8, sage had the highest arousal effect, increasing arousal by 49% compared to the no-scent condition, indicating that it can evoke positive emotions. In contrast, sandalwood and agarwood showed lower arousal effects, with increases of only 29% and 17%, respectively. The low-arousal scents of agarwood and sandalwood can create a calm and nostalgic atmosphere, making them more suitable for the HEZ. This environment helps visitors focus their attention and immerse themselves in the profound sense of history, suggesting that the highly arousing scent of sage may not be appropriate for this area.

In the CDZ, the awakening effects of different scents showed significant differences (F(3, 124) = 10.575,

p < 0.001, η

2 = 0.204). As illustrated in

Figure 9, aromatic plants effectively enhanced visitors’ levels of arousal, with rosemary providing the greatest awakening effect, increasing arousal by 29%. Conversely, lemongrass exhibited the weakest awakening effect, almost on par with the no-scent scenario, resulting in a minimal impact on visitors. Additionally, mint contributed to a 16% increase in arousal. In the CDZ, where the goal is to evoke positive emotions and enhance mental focus and excitement among visitors, high-arousal scents like rosemary are more suitable for this area.

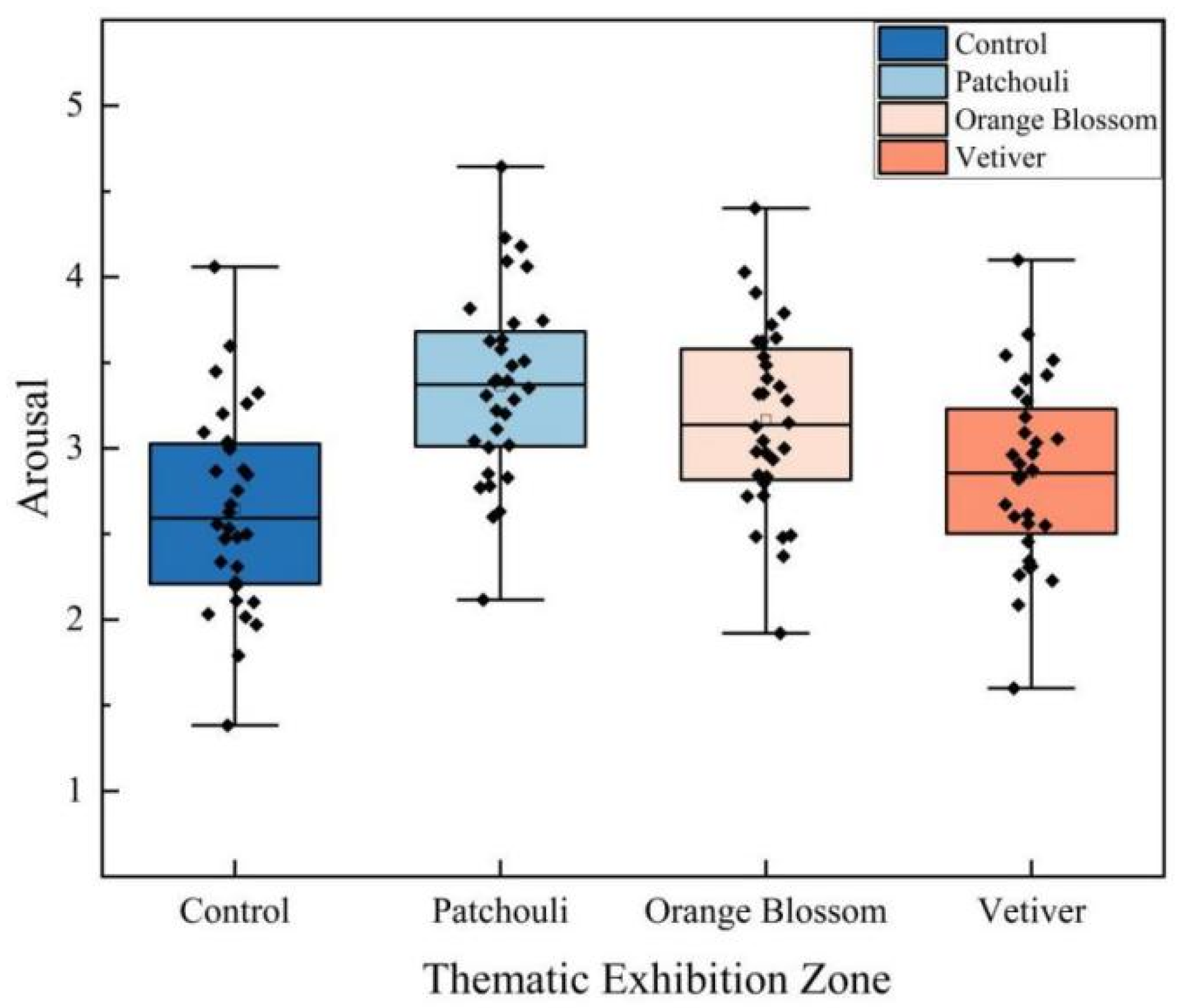

In the TEZ, different scents exhibited significant differences in their arousal effects (F(3, 124) = 10.856,

p < 0.001, η

2 = 0.208). As shown in

Figure 10, various scents positively enhanced arousal, with trends similar to those observed in the CDZ, although the enhancement effects were not as pronounced as in the HEZ. Among the scents, patchouli demonstrated the best arousal effect, enhancing arousal by 27%, while orange blossom increased arousal by 20%. In contrast, vetiver exhibited a limited effect, only enhancing arousal by 8%. This indicates that the arousal effect of vetiver is relatively low; it tends to help visitors calm down, alleviate anxiety, and provide a sense of tranquility and safety. Thus, it is more suitable for exhibition areas that require reflection and serenity.

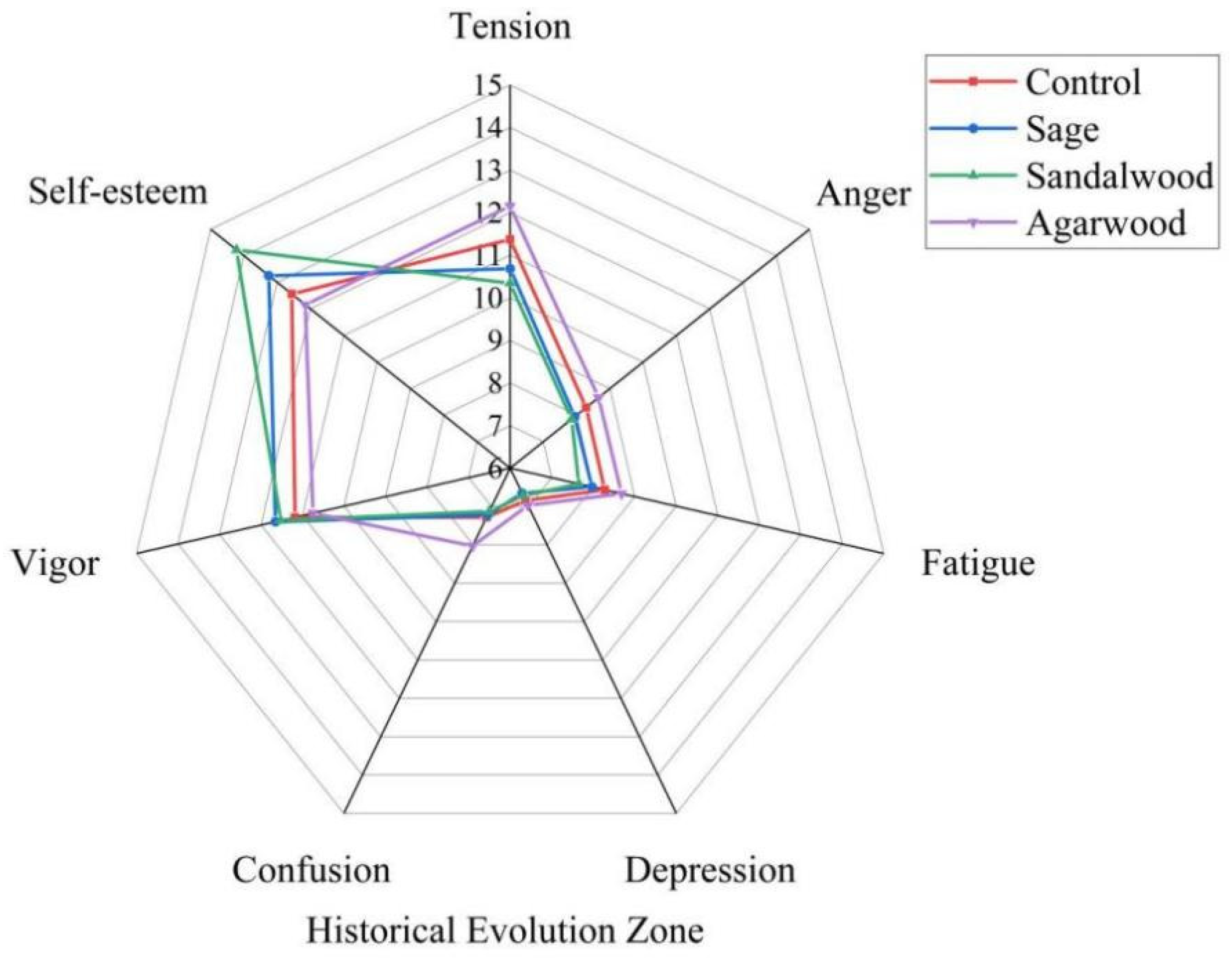

3.4. POMS

We conducted a statistical analysis of the changes in participants’ scores across various dimensions of the POMS scale before and after exposure to the scents. Significant differences were observed in the dimensions of tension, anger, fatigue, depression, confusion, vigor, self-esteem, as well as in the total mood disturbance (TMD) scores.

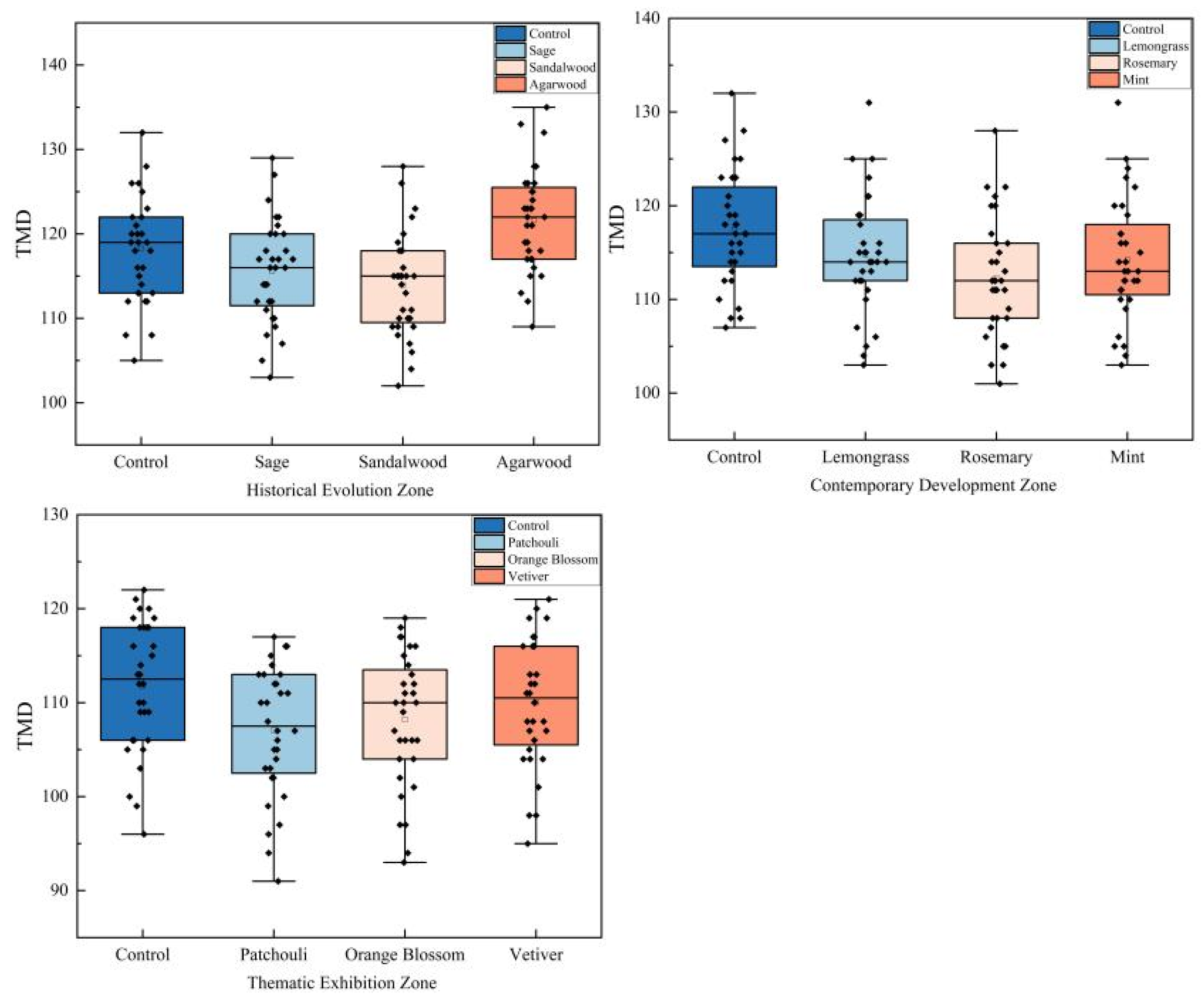

In the HEZ, the TMD showed significant differences across different smellscapes (F(3, 124) = 9.385,

p < 0.001, η

2 = 0.185). As shown in

Figure 11, sage exhibited a favorable effect in reducing negative emotions such as tension, anger, and fatigue, while also enhancing vigor and self-esteem. Sandalwood demonstrated the best overall performance, which was particularly evident in its ability to reduce tension and significantly improve self-esteem. Agarwood, on the other hand, had a negative impact on some negative emotions (such as tension, fatigue, and confusion) but was effective in alleviating depression. Based on these results, the study suggests that sandalwood may be the most suitable scent choice for the HEZ, as it not only reduces negative emotions but also significantly enhances visitors’ self-esteem and vigor.

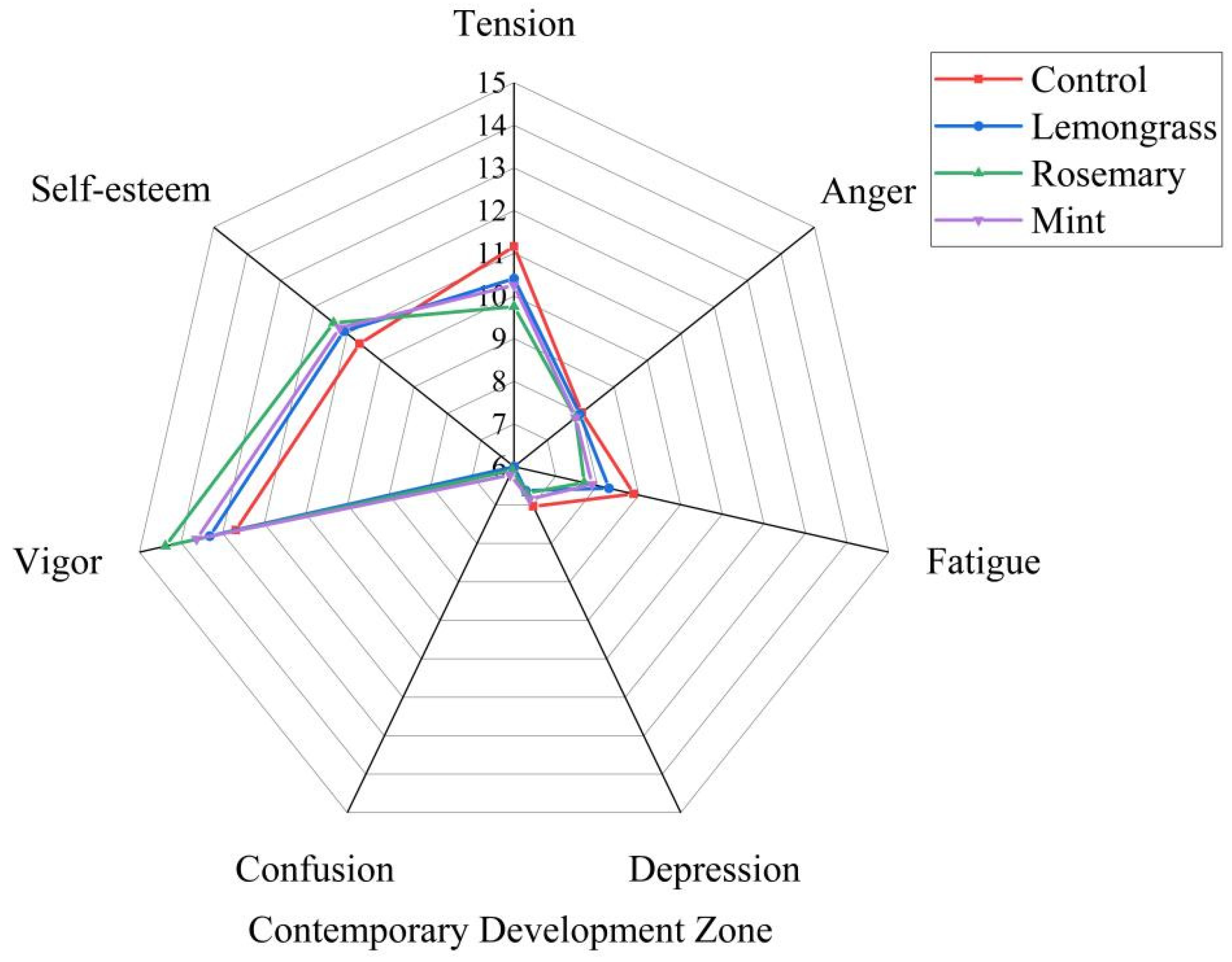

In the CDZ, the TMD exhibited significant differences across various smellscapes (F(3, 124) = 3.672,

p < 0.05, η

2 = 0.082). As illustrated in

Figure 12, rosemary demonstrated the best performance in alleviating tension, fatigue, and depression, while enhancing vigor and self-esteem, although it may have slightly increased visitors’ feelings of confusion. Mint effectively reduced tension and fatigue while improving vigor and self-esteem, but it also had a mild elevating effect on confusion. Lemongrass showed good results in reducing depression and fatigue, with a relatively smaller effect on alleviating tension and the least impact on confusion. This suggests that lemongrass may be the most balanced option for emotional regulation, while rosemary and mint are more suitable for scenarios aimed at enhancing vigor and self-esteem.

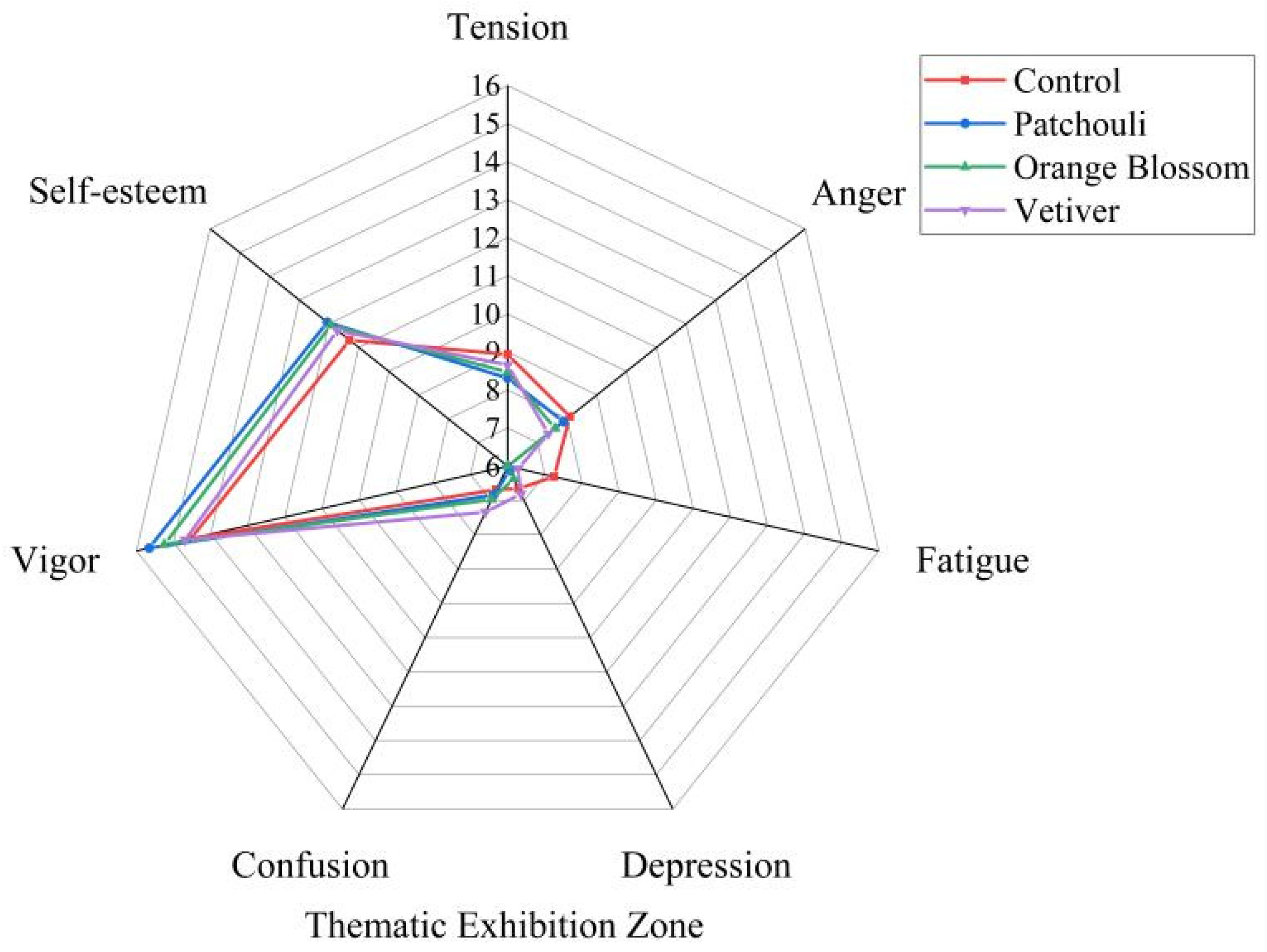

In the TEZ, the TMD showed significant differences across different smellscapes (F(3, 124) = 2.869,

p < 0.05, η

2 =0.065) (

Figure 13). Patchouli performed exceptionally well across almost all emotional dimensions, particularly in reducing fatigue and depression, as well as enhancing vigor and self-esteem, providing visitors with a more positive emotional experience. Orange blossom also showed good effects, especially in reducing tension and increasing vigor, making it suitable for enhancing positive emotions. Vetiver contributed to reducing feelings of anger and increasing vitality, but its effects were slightly weaker compared to orange blossom and patchouli. Based on these results, patchouli and orange blossom may be more suitable for areas that require an enhancement of positive emotions, while vetiver may be more appropriate for areas that need emotional stabilization.

As previously mentioned, the TMD scores generated by different smellscapes showed significant differences, with higher TMD scores indicating a tendency towards more negative and subdued emotions. As illustrated in

Figure 14, in the HEZ, sandalwood had the lowest TMD score (113.94), suggesting that it is the most effective in alleviating negative emotions and helping to reduce tension, anxiety, and depression. In contrast, agarwood had the highest TMD score (121.59), indicating that it may trigger more negative emotions and should be used cautiously in this area. In the CDZ, rosemary achieved the lowest TMD score (112.28), showing that it best supports visitors in maintaining a positive emotional state while reducing negative emotions. Conversely, the control group with no scent had a higher TMD score (117.47), suggesting that a scent-free environment may not effectively improve visitors’ emotions. Both mint and lemongrass had similar scores, indicating their effectiveness in reducing negative emotions as well. In the TEZ, patchouli had the lowest TMD score (107.06), indicating that it is most effective in reducing negative emotions and fostering a positive outlook. Orange blossom followed closely, with a TMD score of 108.22, also demonstrating good emotional enhancement effects. In contrast, the control group and vetiver had higher TMD scores, potentially leading to slightly more negative emotions.

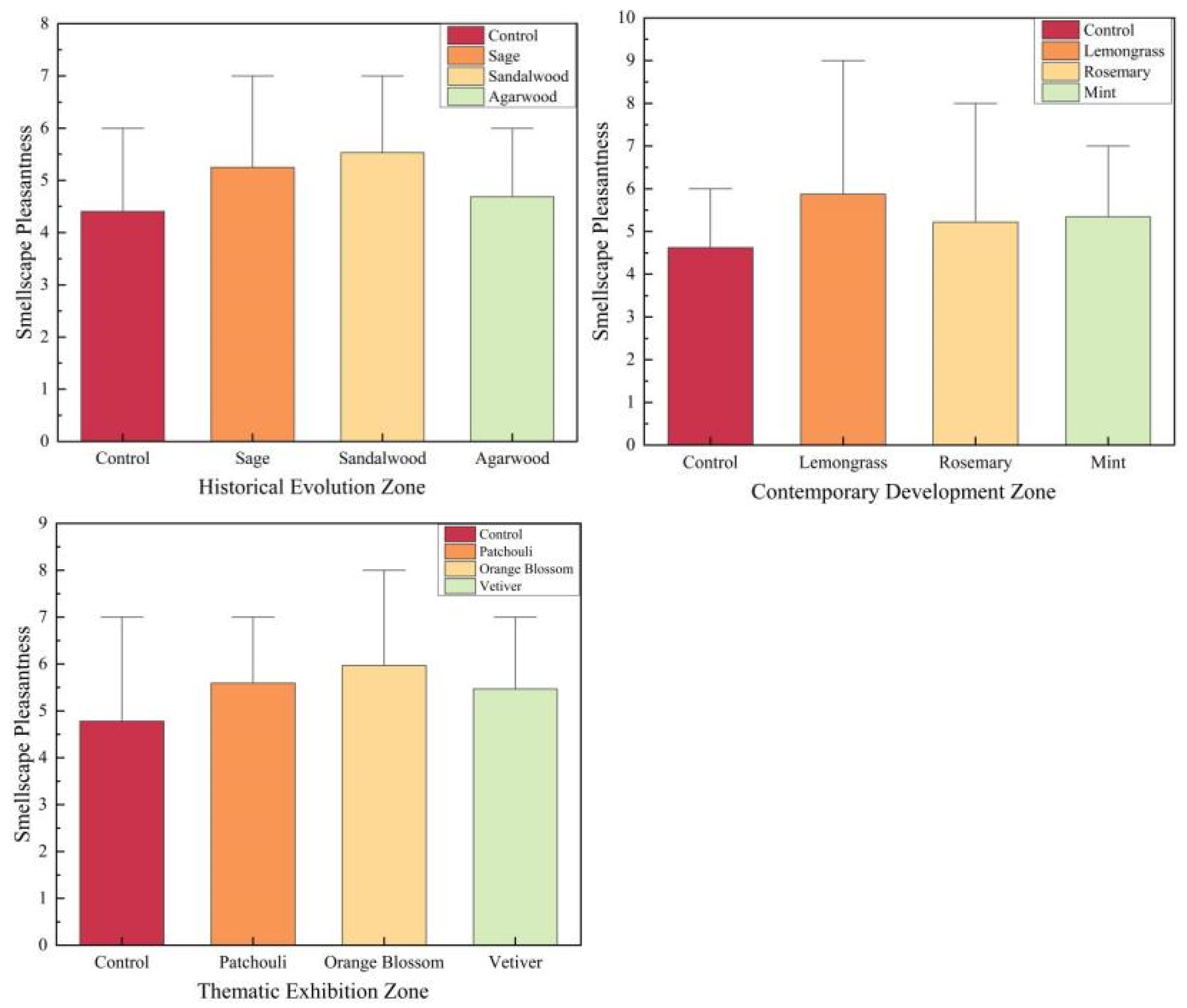

3.5. Smell Pleasantness

The pleasantness of smellscapes measures the effectiveness of scents in evoking feelings of pleasure, comfort, and relaxation. Pleasantness is closely related to visitors’ emotions, levels of arousal, and overall satisfaction with their experience. An enjoyable smellscape can help reduce anxiety and tension, enhancing overall emotional states and making visitors feel more comfortable and pleased. In the HEZ, there are significant differences in the pleasantness of different smellscapes (F(3, 124) = 8.976, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.178). In the CDZ, significant differences in pleasantness are also observed among various smellscapes (F(3, 124) = 5.181, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.111). Furthermore, in the TEZ, significant differences in pleasantness exist across different smellscapes (F(3, 124) = 4.597, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.100).

As illustrated in

Figure 15, in the HEZ, sandalwood had the highest pleasantness score of 5.53, indicating strong comfort and popularity, making it suitable for use in this region. Sage followed with a pleasantness score of 5.25, also at a high level, exhibiting soothing properties. Agarwood had a lower pleasantness score of 4.69, likely due to its strong scent, which may not appeal to a majority of people. In the CDZ, lemongrass had the highest pleasantness score of 5.86, suggesting that its refreshing aroma is very suitable for this area, helping to enhance visitors’ vitality and positive emotions. Mint closely followed with a pleasantness score of 5.34, providing a cooling and invigorating effect. Rosemary, while slightly lower at 5.22, still maintained a high pleasantness level, making it appropriate as an auxiliary scent in the contemporary development area. In the TEZ, orange blossom achieved the highest pleasantness score of 5.97, indicating that its fragrance is exceptionally delightful and well-suited for the hopeful environment of the future outlook area. Patchouli followed with a pleasantness score of 5.59, also demonstrating excellent pleasantness, making it suitable for use in the future outlook area. Vetiver, with a pleasantness score of 5.47, was slightly lower than the other scents but still fell within a high range, making it appropriate for enhancing a sense of stability in the region.

In summary, the scent with the highest pleasantness was orange blossom, with a score of 5.97, indicating its particular suitability for the TEZ, as it can evoke optimism and hope. Sandalwood was the most favored scent in the historical evolution area. In the CDZ, lemongrass is recommended due to its highest pleasantness score, which can stimulate vitality and freshness. Higher pleasantness scents are more suitable for areas focused on emotional experiences and positive emotion stimulation, such as the TEZ and CDZ. Scents with lower pleasantness, like agarwood, may be more appropriate for the HEZ, where there is a higher demand for cultural experience, as this scent can evoke strong cultural associations.

3.6. Smellwalk Interview

In the study of olfactory landscapes in the university history museum, a walking interview was conducted to gather data on the impact of different scents in various exhibition areas on participants’ emotions and cognition. To validate the effectiveness of these findings, we selected the most suitable scents for each area. Sandalwood was used in the HEZ, rosemary was placed in the CDZ, and patchouli was introduced in the TEZ.

According to the interview results, most respondents reported noticing variations in scent. In the HEZ, many individuals remarked on the pronounced aroma of sandalwood. In contrast, the fresh scents of lemongrass and mint were more prominent in the CDZ. Meanwhile, the scent of patchouli in the TEZ provided a softer, more hopeful scent experience. Overall, the arrangement of the smellscape enhanced the visitor experience. A small number of participants mentioned that, in certain exhibition areas, their focus on visual displays hindered their ability to perceive scent changes; however, they could detect the scents when specifically paying attention to them.

In the HEZ, participants generally reported that the scent of sandalwood possesses a strong sense of history and ritual, evoking feelings of respect and admiration for traditional culture. Some participants noted that this fragrance reminded them of the atmosphere of libraries or ancient buildings, enhancing their immersion in historical periods. One interviewee pointed out that the scent of sandalwood made him feel the passage of time and the profound historical background of the university, allowing for a deeper understanding of the institution’s past.

In the CDZ, the scent of rosemary tends to evoke feelings of freshness and vitality among participants. Many expressed that this fragrance instills a sense of modernity and innovation, prompting them to consider the university’s vigorous growth. Some participants noted that the scent helps to invigorate them, stimulating mental activity and drawing attention to the university’s current achievements. Additionally, some interviewees mentioned that the rosemary aroma brings them a sense of hope and motivation, making them feel that the university is vibrant and continuously advancing.

In the TEZ, participants generally responded positively to patchouli, perceiving this scent as fresh and filled with a sense of the future. Many provided feedback that patchouli evoked thoughts of new beginnings and limitless possibilities, inspiring their hopeful expectations for the future. Some participants noted that the scent of patchouli is light with a hint of sweetness, creating an optimistic and uplifting atmosphere that encouraged them to envision the university’s future development direction.

The results of the smellwalk indicate that the olfactory arrangements in different exhibition areas not only enhanced visitors’ sense of immersion but also had a positive impact on their emotions and cognition. The scent of sandalwood created a solemn historical atmosphere in the HEZ, while the aroma of rosemary brought a sense of modernity and innovation to the CDZ. In the TEZ, the fragrance of patchouli evoked a sense of anticipation and hope for the future. These thoughtfully designed smellscape contribute to enhancing the overall quality of the visitor experience.

5. Conclusions

This study designed a smellscape based on the Fuzhou University Museum, exploring the impact of integrating scents into different areas of the museum on visitors’ emotions. Through emotional responses, the study demonstrated the key role of olfactory elements in landscape design. The results confirm the correlation between olfactory and emotional factors in enhancing landscape perception. The overall emotional tone of the HET leans towards neutrality, with a slight tendency towards negative emotions, reflecting the seriousness of cultural transmission.

Through the smellscape experiment, we arrived at the following conclusions: in the HEZ, steady scents such as sandalwood and agarwood effectively convey a sense of history but may also trigger higher levels of negative emotions and nostalgia. The use of sage enhances visitors’ positive emotions, making the nostalgic experience more vibrant. In the CDZ, the combination of rosemary and mint effectively improves visitors’ emotional states and enhances their positive feelings. In contrast, although lemongrass has a refreshing effect, it performs poorly in terms of pleasantness, indicating that it does not fully meet the olfactory needs of this scenario. In the TEZ, patchouli and orange blossom demonstrate higher levels of pleasantness and emotional value, aligning well with the future outlook theme presented in this area. While vetiver can evoke some positive emotional responses, its adaptability to this context is relatively low.

Overall, smellscape can produce significant emotional differences across various exhibition areas. By carefully selecting and matching scents, not only can the cultural expression of the exhibits be enhanced, but visitors’ emotions can also be effectively regulated, improving their immersive experience. Moreover, this study enriches the theoretical application of olfactory landscapes in museums and provides empirical support, offering valuable insights for other universities, cultural venues, or exhibitions. In the future, smellscape should be considered an essential strategy when designing similar exhibition spaces.