The Spatial Form of the Traditional Residences of Shanxi Merchants: A Case Study of Pingyao Ancient City, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Shanxi Merchants and Traditional Residences

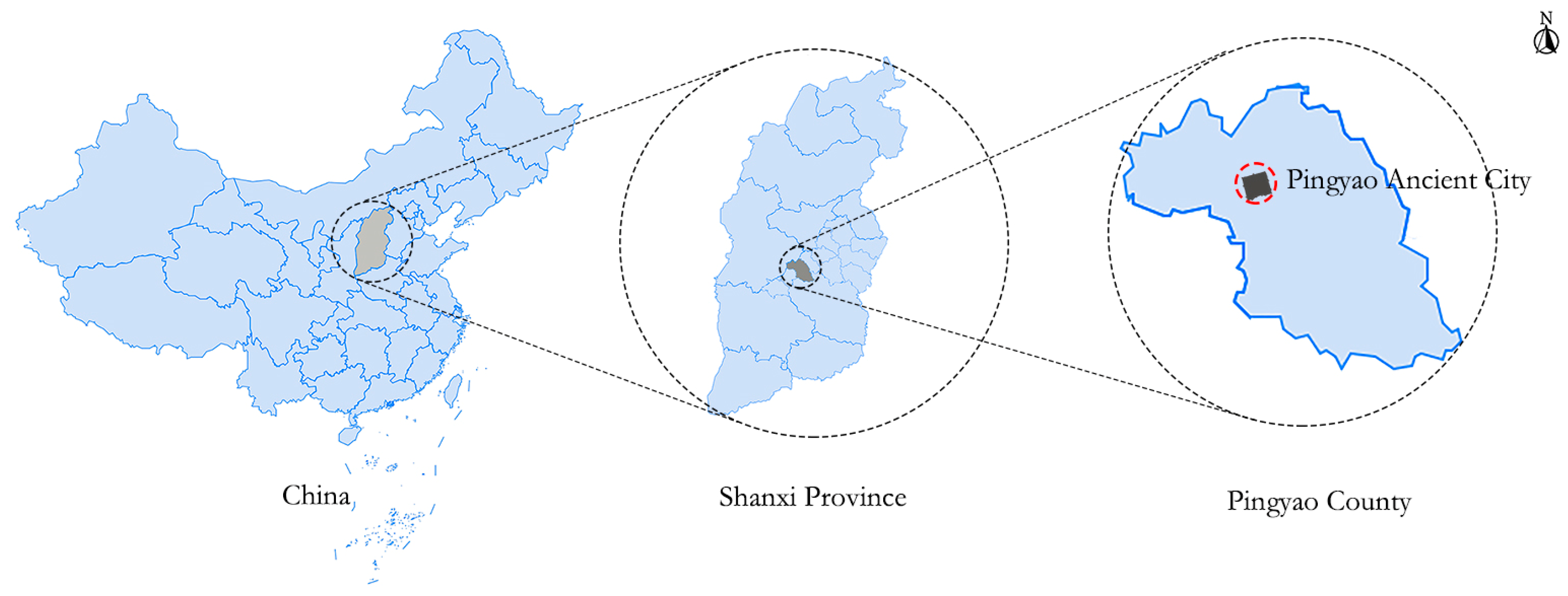

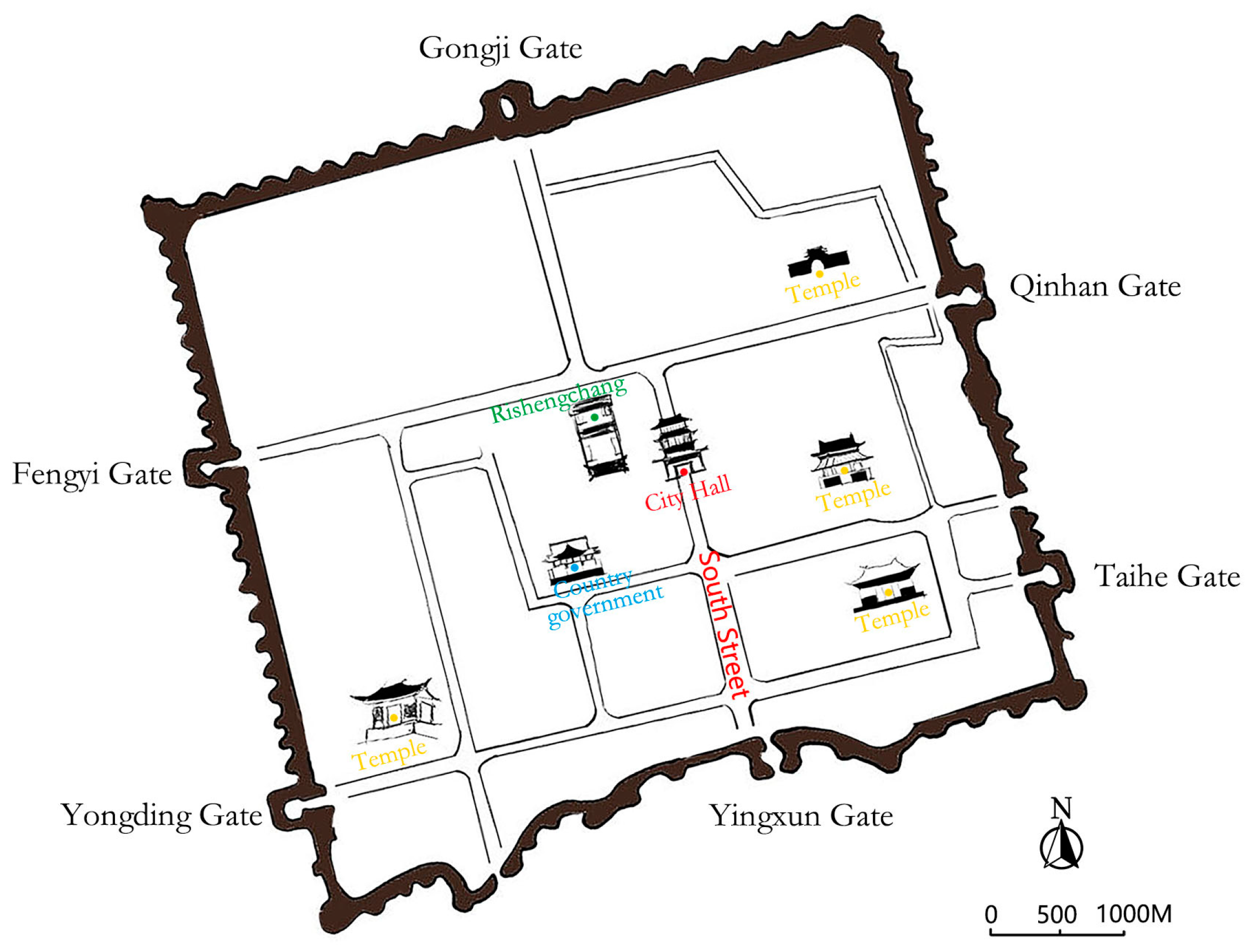

1.2. Ancient City of Pingyao

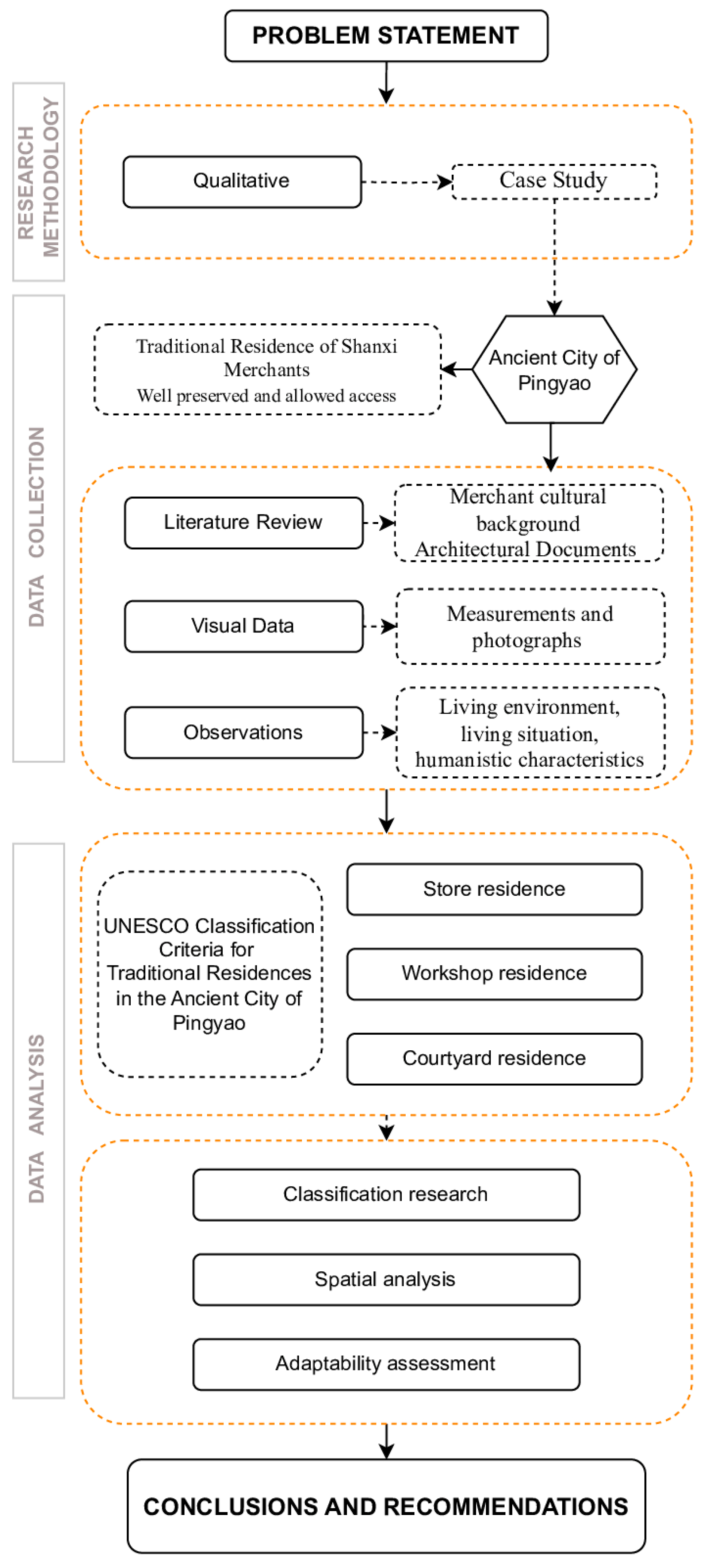

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Study

2.2. Methods

3. Results

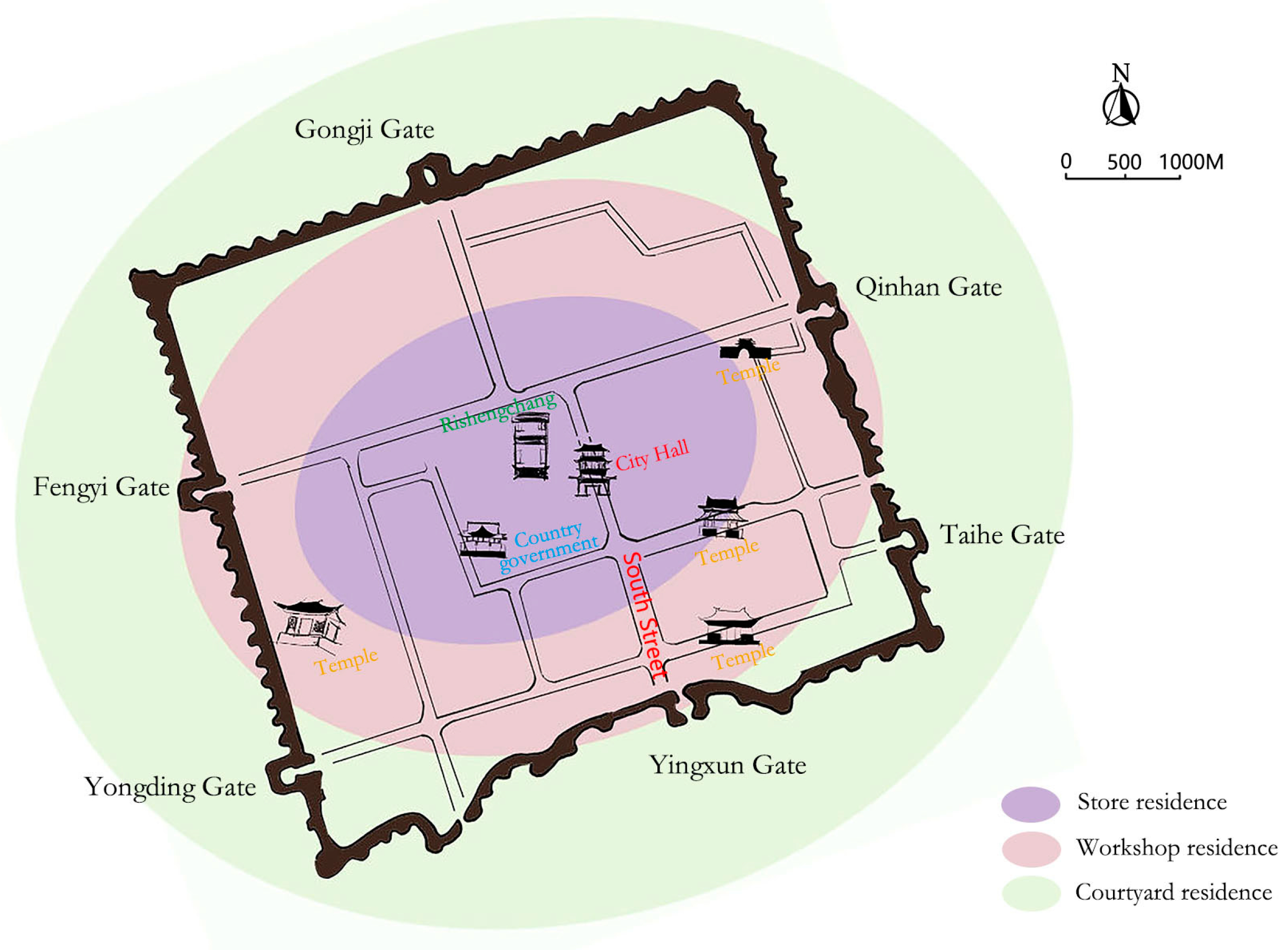

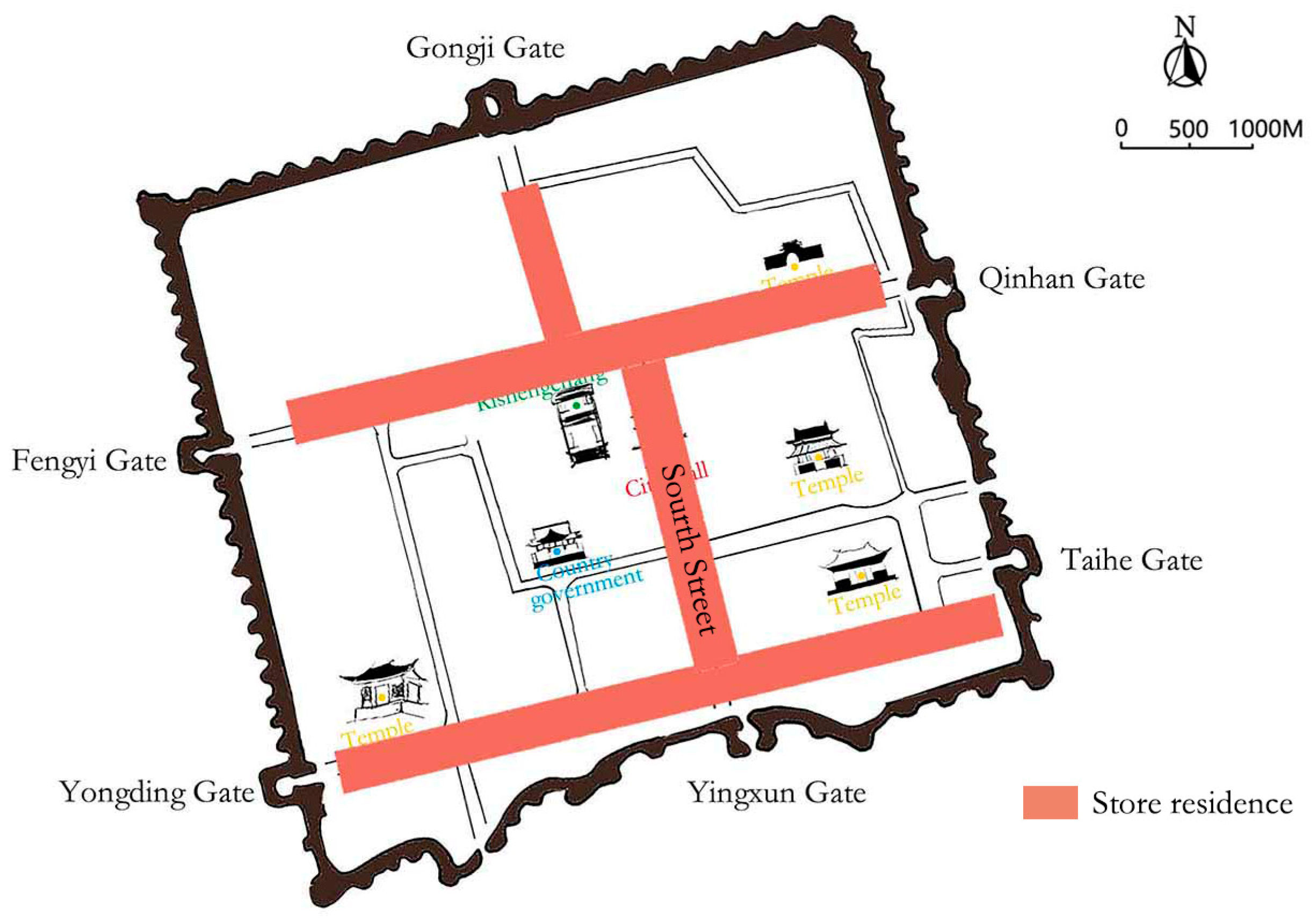

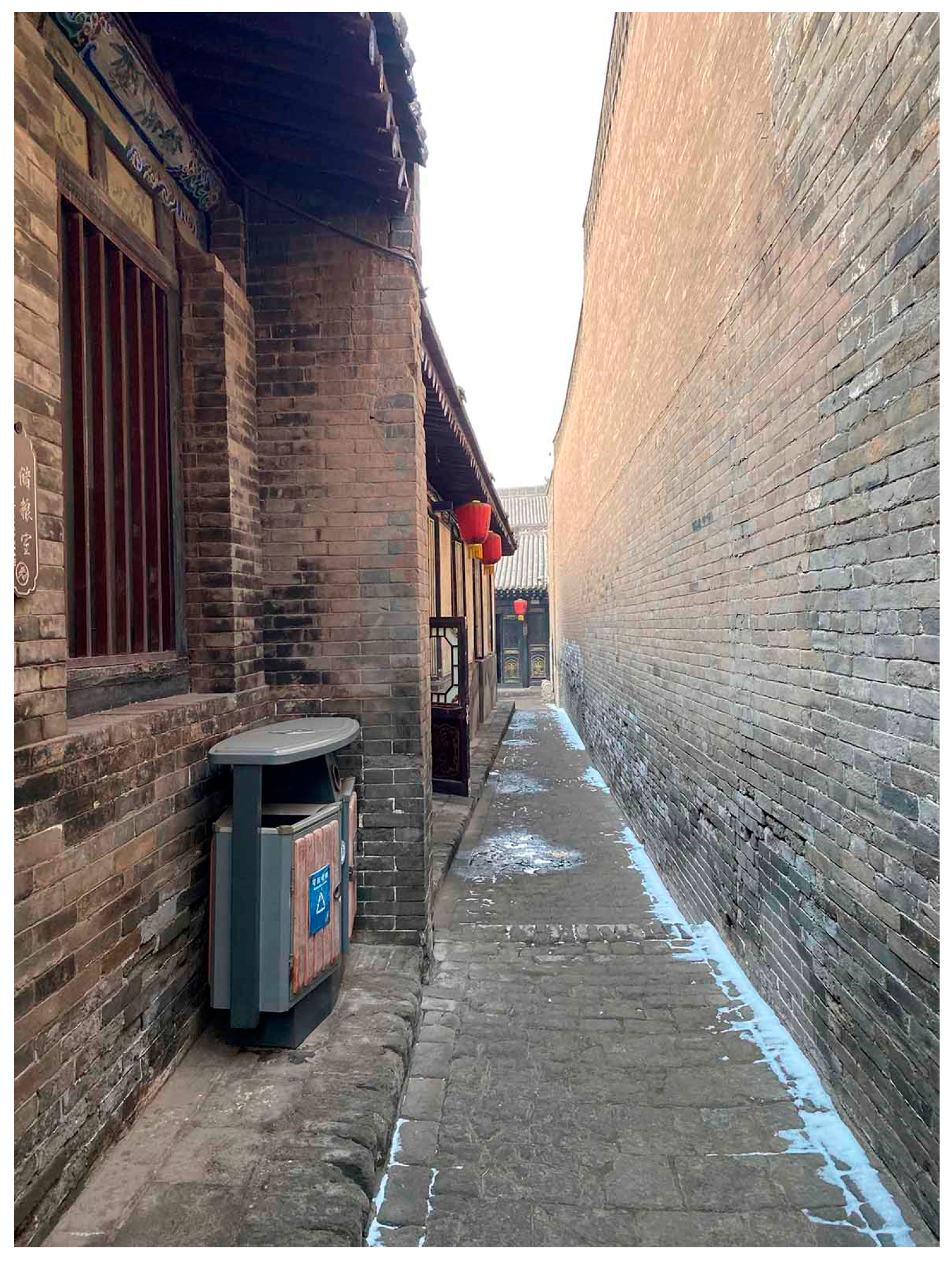

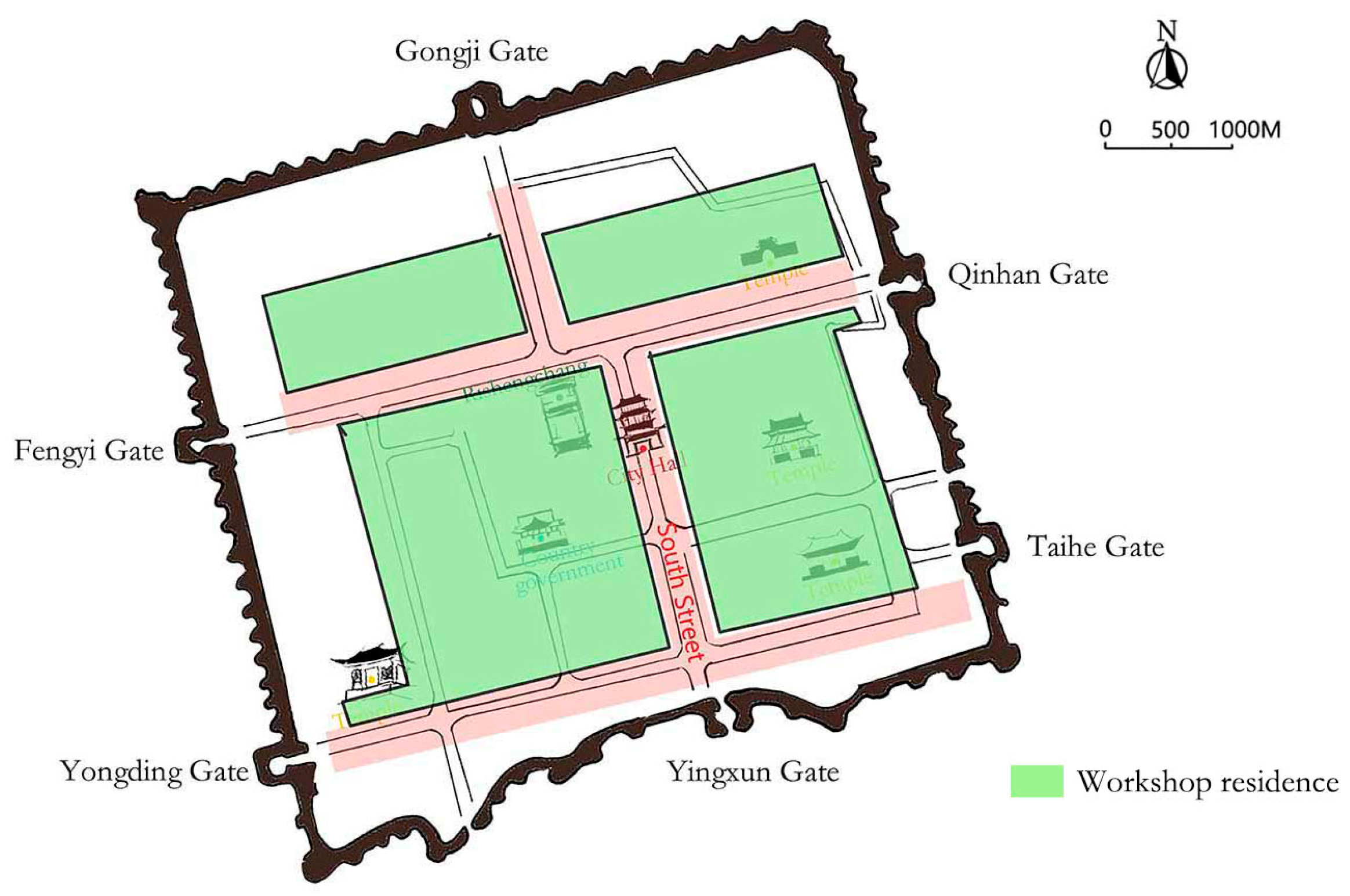

3.1. Distribution and Classification of Traditional Residences of Shanxi Merchants in the Ancient City of Pingyao

3.2. Analysis of the Spatial Form of Three Types of Traditional Residences

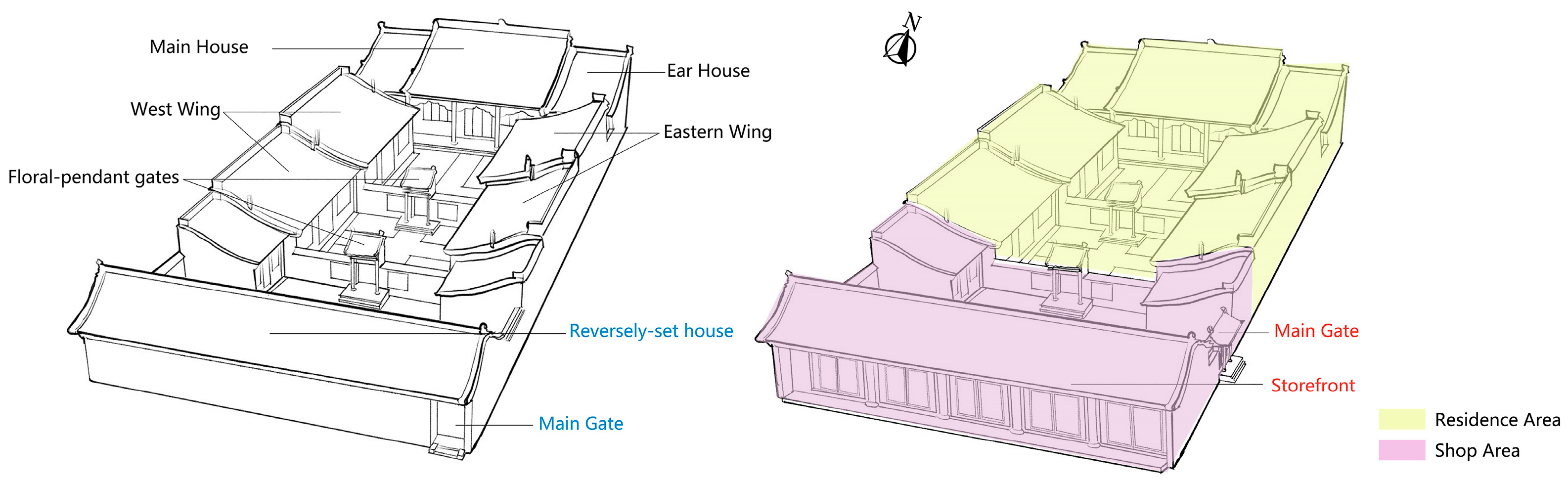

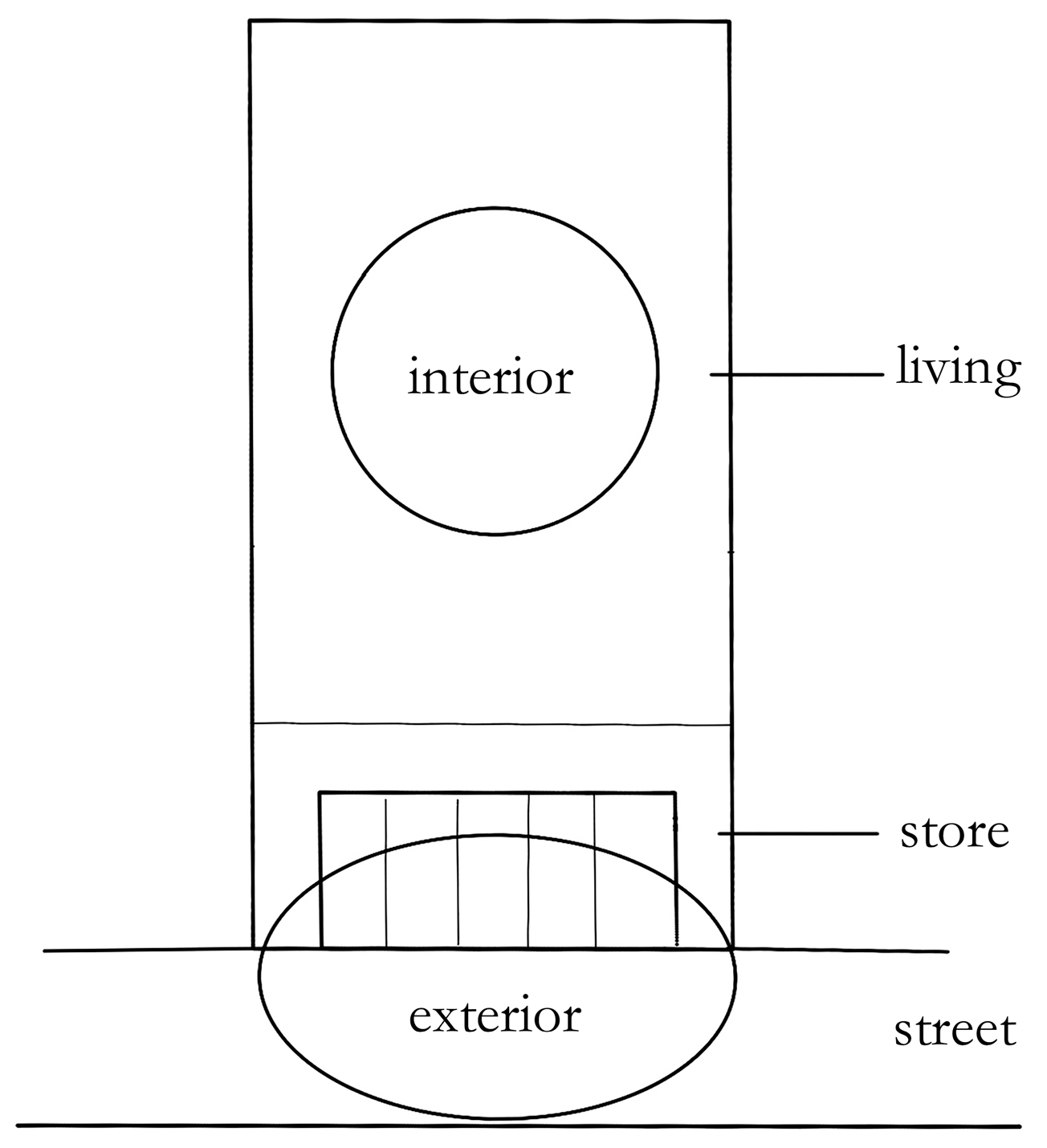

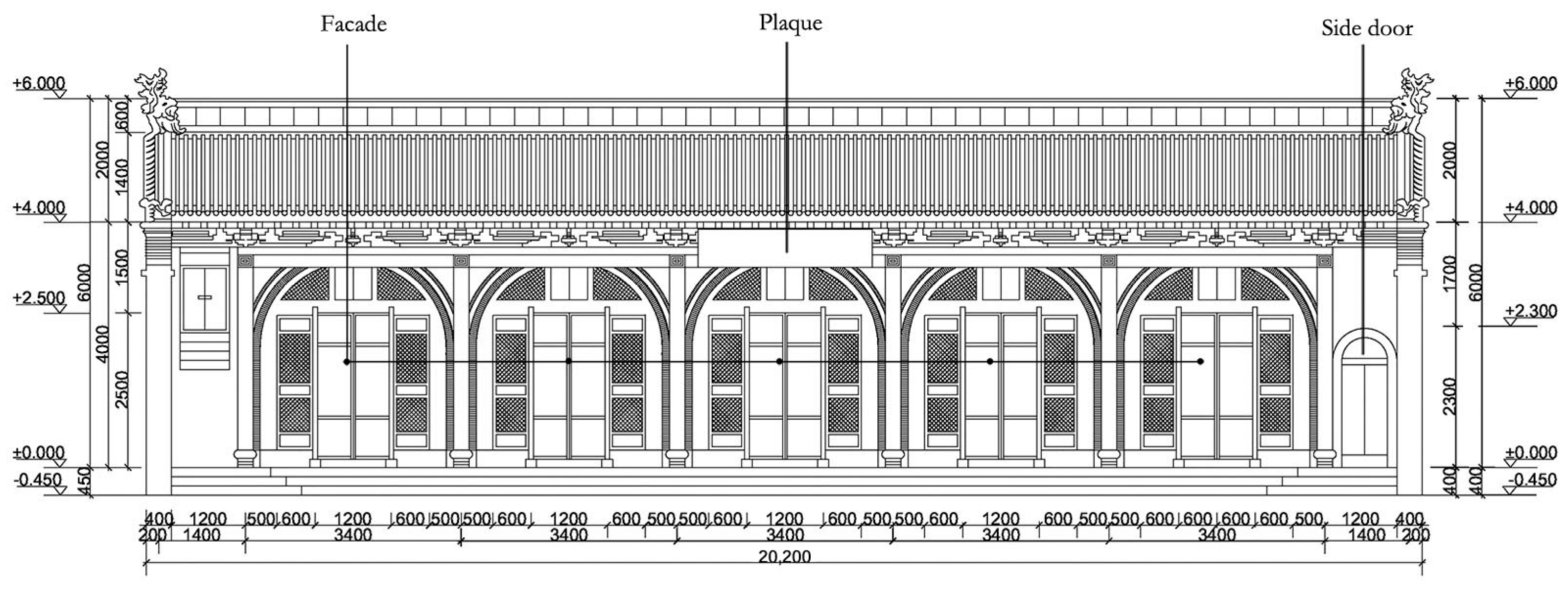

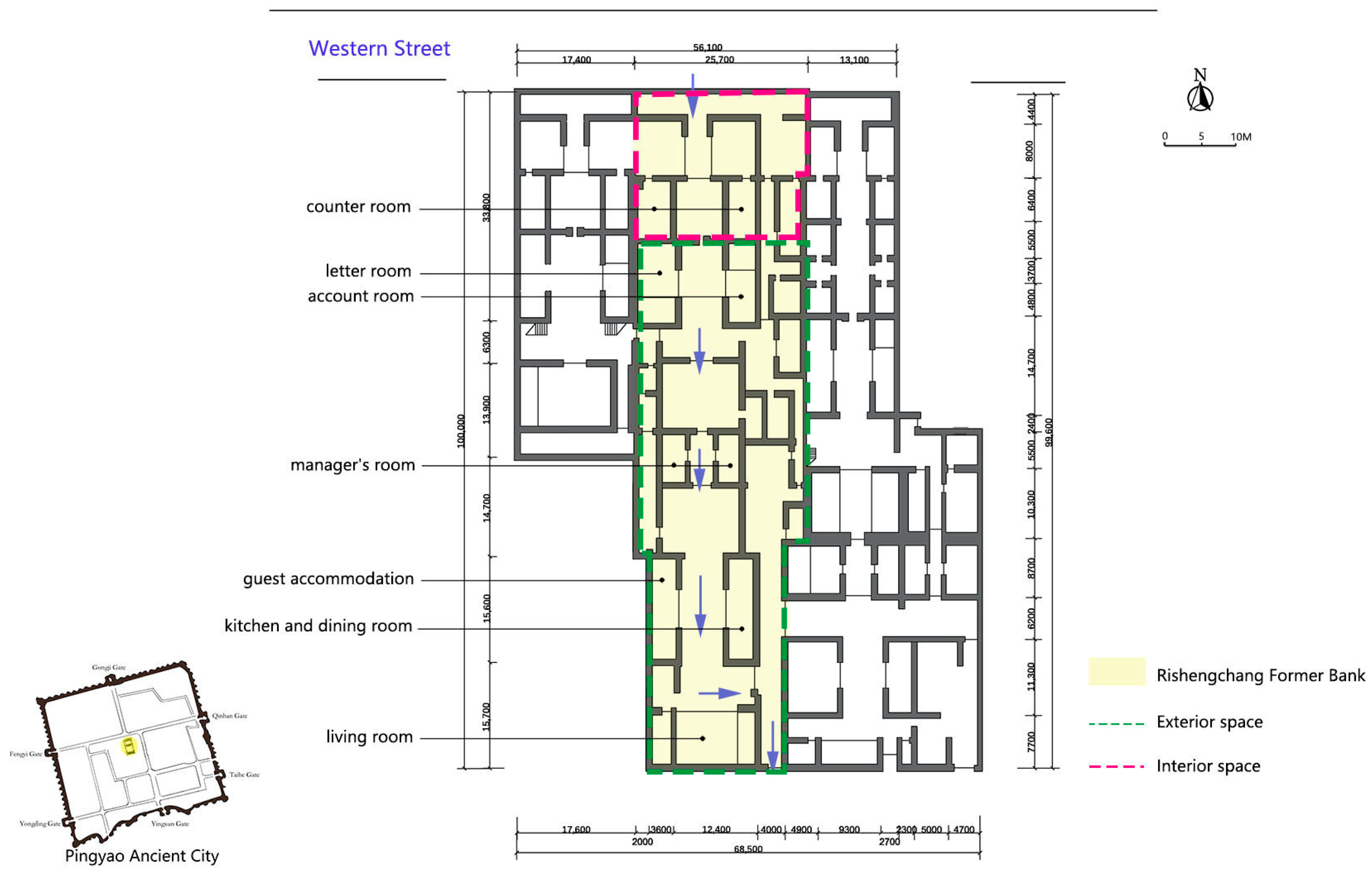

3.2.1. Store Residence with a Front Store and Rear Residence

- 1.

- Interior and Exterior.

- 2.

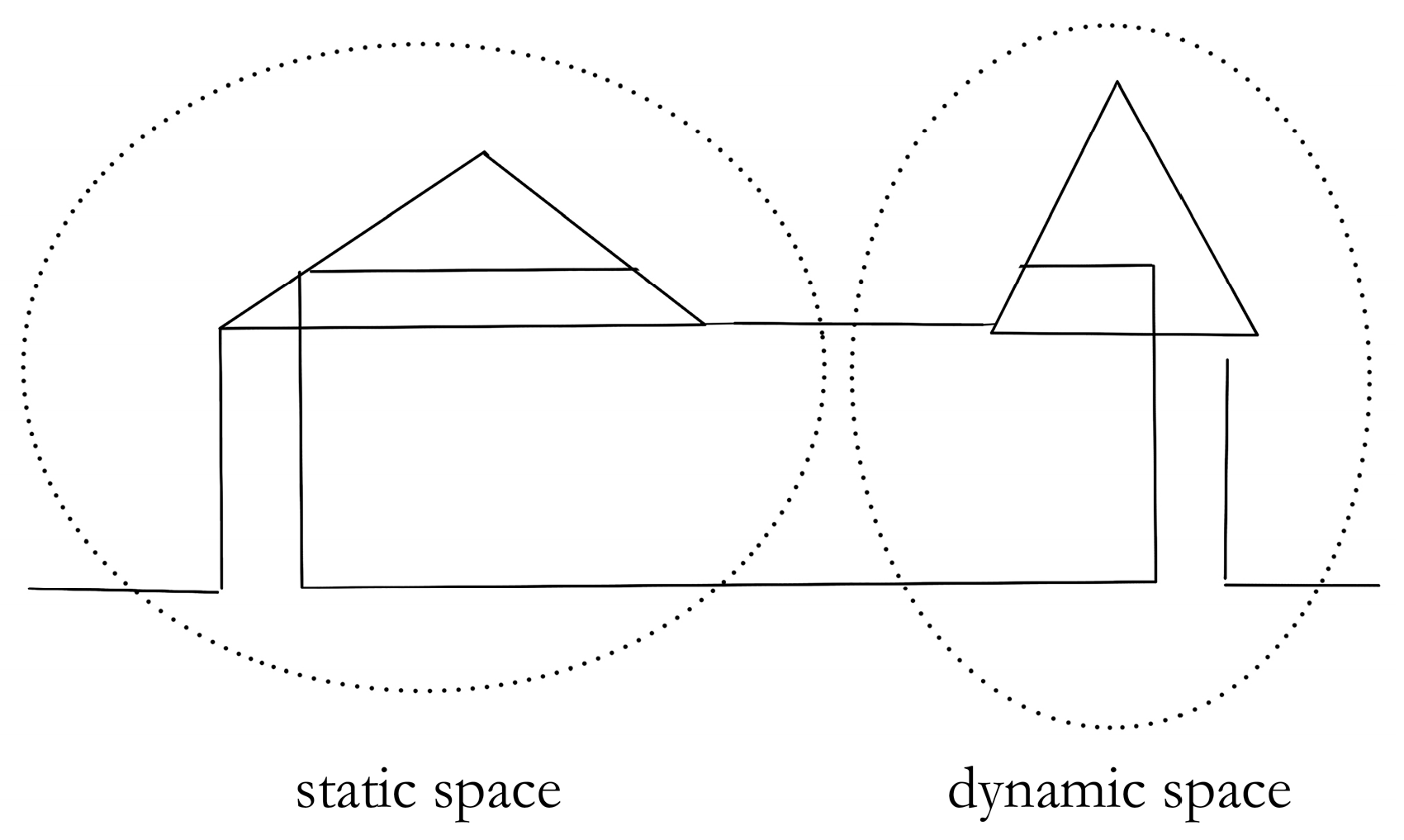

- Dynamic and Static.

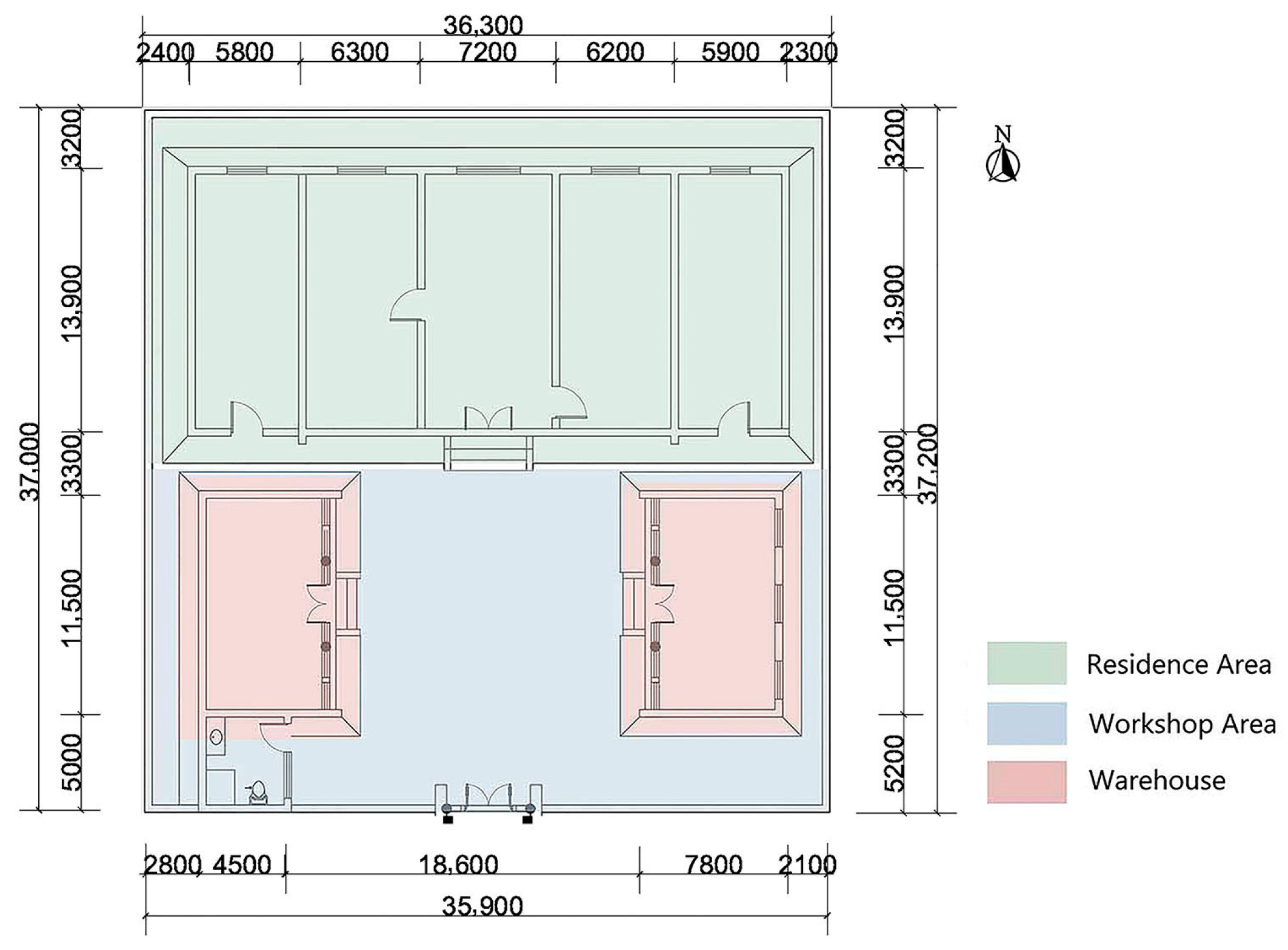

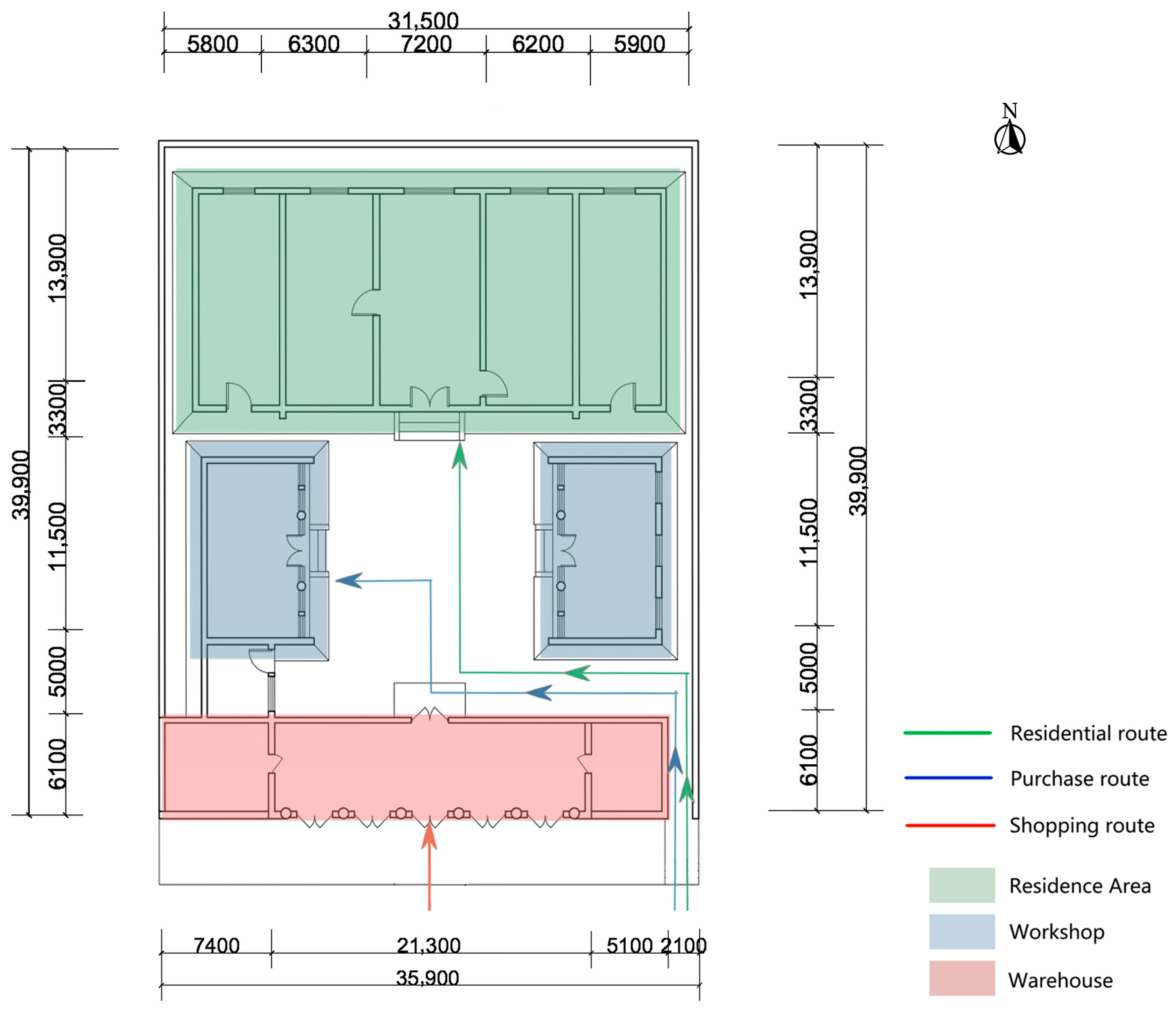

3.2.2. Workshop Residence with a Front Workshop and Rear Residence

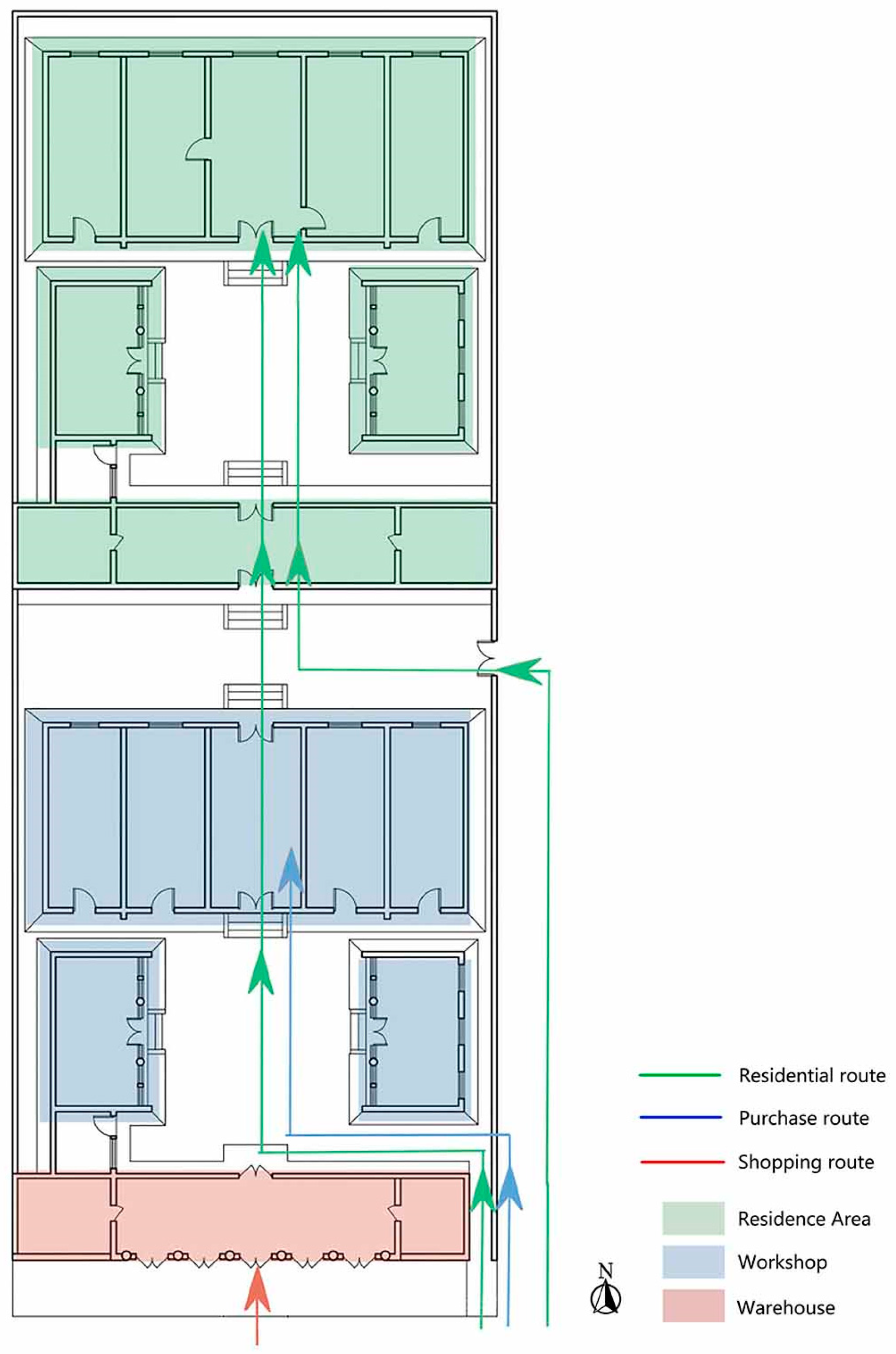

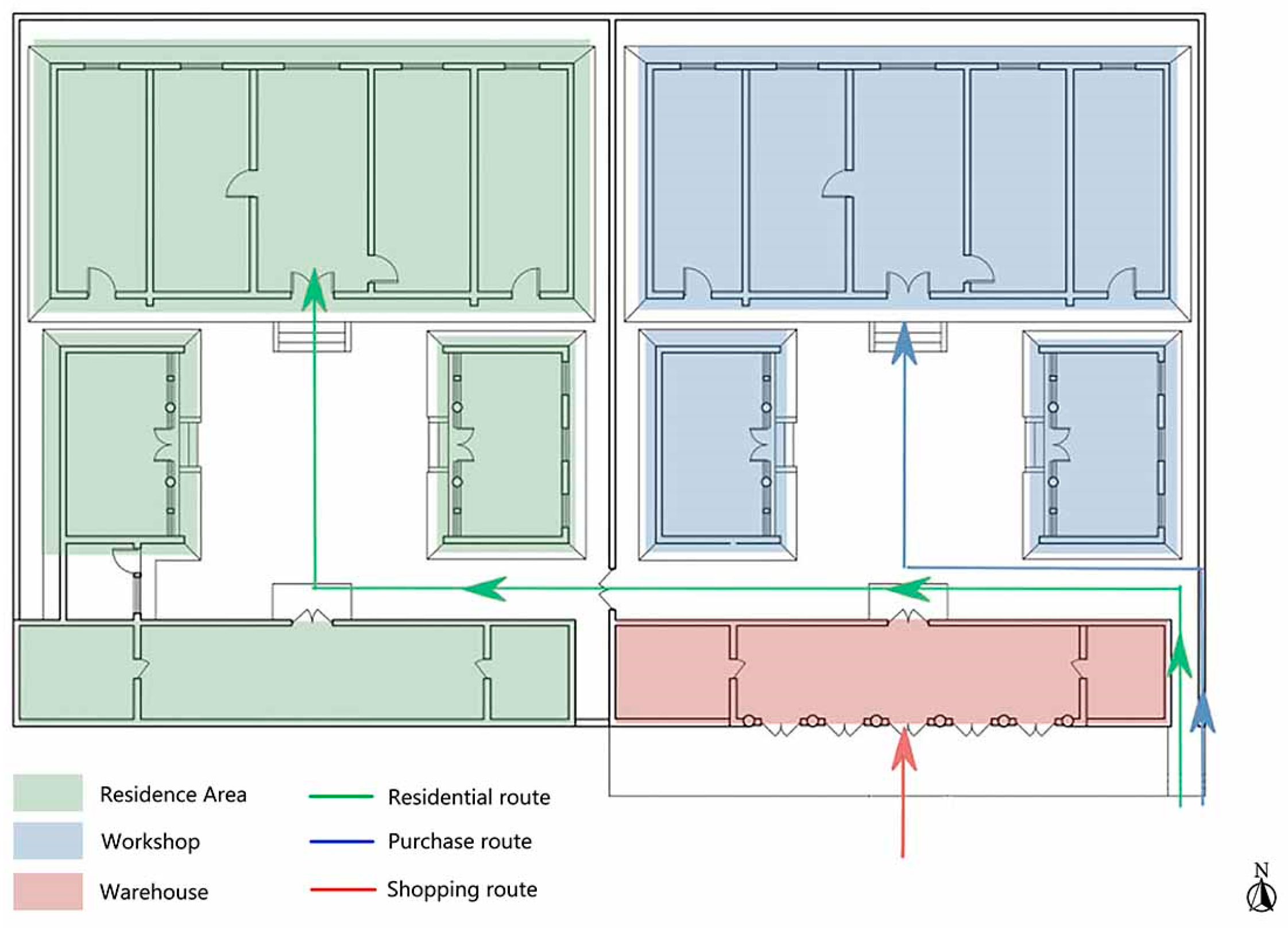

3.2.3. Complex Courtyard Residences

- 3.

- Rigorous layout.

- 4.

- Grand scale.

- 5.

- Luxurious appearance.

- 6.

- Lavish interior decoration.

- 7.

- Full of merchants’ values.

4. Discussion

4.1. Influential Factors on the Spatial Form of Traditional Residences of Shanxi Merchants

4.1.1. Commercial Operation and Business Model

4.1.2. Commercial Consciousness

4.2. Insights from Shanxi Merchant Culture and the Conservation of Traditional Residence

4.3. Adaptive Reuse of Traditional Residences and Modern Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hillier, B.; Julienne, H. The Social Logic of Space; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. The Production of Space; Blackwell: Oxford, UK; Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Laurajane, S. Uses of Heritage; Routledge (Taylor & Francis Group): Abingdon, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1972; Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/conventiontext/ (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Cauchi-Santoro, R. Mapping Community Identity: Safeguarding the Memories of a City’s Downtown Core. City Cult. Soc. 2016, 7, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, R.G. China’s Vernacular Architecture: House Form and Culture; University of Hawaii Press: Honolulu, HI, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Lang, J. Huishang He Jinshang Dian Xing Min Ju Ji Gong Gong Kong Jian de Xing Cheng Tan Jiu [Exploring the Formation of Typical Residences and Public Spaces of Anhui Merchants and Shanxi Merchants]. Folk Houses Old Build. 2024, 17, 26–35. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Hu, Y. Corporate Governance in Ming & Qing China: Evidence from Shanxi (Jin) Merchants. J. Chin. Econ. Bus. Stud. 2024, 22, 87–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Hao, Y.; Jin, F.; Zhou, J. Shanxi Merchants’ Multilevel Financial System in Ming and Qing Dynasties, China. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2017, 53, 376–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.; Yang, F. Shanxi Piaohao and Shanghai Qianzhuang: A Comparison of the Two Main Banking Systems of Nineteenth-Century China. Bus. Hist. 2016, 58, 433–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M. How Did the Chinese Shanxi Merchants Determine the Remittance Fees? Micro Firm Analysis of Rishengchang Piaohao. Front. Econ. China 2018, 13, 484–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y. Qian Tan Jinshang Wen Hua [Introduction to Shanxi Merchant Culture]. Yellow River Yellow Earth Yellow People 2023, 6, 51–53. [Google Scholar]

- Moylan, E.; Brown, S.; Kelly, C. Toward a Cultural Landscape Atlas: Representing All the Landscape as Cultural. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2009, 15, 447–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aplin, G. World Heritage Cultural Landscapes. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2007, 13, 427–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Liu, J.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, X. Spatial Pattern and Micro-Location Rules of Tourism Businesses in Historic Towns: A Case Study of Pingyao, China. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2022, 25, 100721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Gu, K. Pingyao: The Historic Urban Landscape and Planning for Heritage-Led Urban Changes. Cities 2020, 97, 102489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D. Pingyao Historic City and Qiao Family Courtyard. J. Chin. Archit. Urban. 2022, 4, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Hou, W.; Liu, M.; Yu, Z. Traditional Thoughts and Modern Development of the Historical Urban Landscape in China: Lessons Learned from the Example of Pingyao Historical City. Land 2022, 11, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K. Cultural Heritage Management: A Possible Role for Charters and Principles in Asia. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2004, 10, 417–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.; Gu, K. Urban Morphology and Tourism Planning: Exploring the City Wall in Pingyao, China. J. China Tour. Res. 2011, 7, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L. Annals of Pingyao Ancient City; Zhonghuashuju: Shanghai, China, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, K.; Ito, H. A Study on the Spatial Structure and Its Cultural Factors in Pingyao, China. Asian Cult. Hist. 2022, 14, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Zhang, P. Pingyao gu cheng chuan tong min ju bao hu xiu shan ji huan jing zhi li shi yong dao ze [Practical Guidelines for the Conservation, Restoration, and Environmental Management of Traditional Residences in Pingyao Ancient City]. Chin. Cult. Herit. 2015, 6, 58–61. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Su, H. Xi Shuo Pingyao [Pingyao in Detail]; Shanxi Ancient Books Press: Taiyuan, China, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, J.A.; Chmiel, M.; Rogers, S.E. Designing Integration in Multimethod and Mixed Methods Research. In The Oxford Handbook of Multimethod and Mixed Methods Research Inquiry; Hesse-Biber, S.N., Johnson, R.B., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Yin, J.; Lei, Y. Facade Renovation and Utilizing Ways in the Historical Commercial Streets: Rigid Planning at the Compound Level Needed in Pingyao Ancient City in China. In Building Resilient Cities in China: The Nexus between Planning and Science: Selected Papers from the 7th International Association for China Planning Conference, Shanghai, China, 29 June–1 July 2013; Chen, X., Pan, Q., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lang, J. Xiang Zhen Ju Luo Jian Zhu Kong Jian Ji Huan Jing Zhuang Shi Yi Shu Yan Jiu:Yi Huishang, Jinnan Jian Zhu Wei Li [Research on the Spatial Morphology and Environmental Decorative Art of Township Settlement Architecture: An Example of the Anhui Merchants and the Southern Part of the Shanxi Province’s Architecture]; China Building Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, C. Hua Shuo Pingyao [Painting in Pingyao]; Shanxi Economic Press: Taiyuan, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Han, P.; Hu, S.; Xu, R. New Life in the Countryside: Conservation and Sustainability of Vernacular Architectural Facade Characteristics in the Jiangnan Region, China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, C. Jinshang Min Ju [Shanxi Merchant Houses]; China Building Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, L.; Pan, X.; Wang, X.; Zhou, H. Traditional Chinese Villages: Beautiful Nostalgia; Springer: Singapore, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X. On the Formal Connotation of Residential Door Decoration under the Influence of Shanxi Merchants’Culture. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Arts, Design and Contemporary Education, Moscow, Russia, 23–25 May 2016; Atlantis Press: Moscow, Russia, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Chai, X.; Jiang, R.; Chen, Y. Quantitative Comparison of Space Syntax in Regional Characteristics of Rural Architecture: A Study of Traditional Rural Houses in Jinhua and Quzhou, China. Buildings 2023, 13, 1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Wang, C. Ji Yu Kong Jian Ju Fa de Jinshang Min Ju Zhai Yuan Kong Jian Xing Tai Jie Du [Interpretation on the Spatial Form of Shanxi Merchants’ Residential Houses Based on Spatial Syntax]. Urban. Archit. 2023, 20, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Jin, M.; Zuo, Y.; Ding, P.; Shi, X. The Effect of Soundscape on Sense of Place for Residential Historical and Cultural Areas: A Case Study of Taiyuan, China. Buildings 2024, 14, 1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, K.; He, Y.; Zeng, W. Research on Regional Characteristics and Clustering Protection of Shanxi Historical Villages and Towns in China. In Creative Construction Conference 2018—Proceedings; Budapest University of Technology and Economics: Budapest, Hungary, 2018; pp. 939–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Yang, T. Landed and Rooted: A Comparative Study of Traditional Hakka Dwellings (Tulous and Weilong Houses) Based on the Methodology of Space Syntax. Buildings 2023, 13, 2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D. Courtyard Housing and Cultural Sustainability: Theory, Practice, and Product; Ashgate Publishing: Farnham, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, W. Investigation on the Commercial Architectural Characteristics and Formation of Wang Family Courtyard in Shanxi Province. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Social Science and Technology Education, Sanya, China, 11–12 April 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamovskaya, P.O. Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention; Inzhevatov, I.V., Filatova, N.V., Likhachev, D.S., Eds.; Russian Research Institute for Cultural and Natural Heritage: Moscow, Russia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Jokilehto, J. A History of Architectural Conservation, Repr.; Series in Conservation and Museology; Routledge: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Long, Y.; Zakaria, S.A. The Spatial Form of the Traditional Residences of Shanxi Merchants: A Case Study of Pingyao Ancient City, China. Buildings 2024, 14, 3266. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14103266

Long Y, Zakaria SA. The Spatial Form of the Traditional Residences of Shanxi Merchants: A Case Study of Pingyao Ancient City, China. Buildings. 2024; 14(10):3266. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14103266

Chicago/Turabian StyleLong, Yang, and Safial Aqbar Zakaria. 2024. "The Spatial Form of the Traditional Residences of Shanxi Merchants: A Case Study of Pingyao Ancient City, China" Buildings 14, no. 10: 3266. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14103266

APA StyleLong, Y., & Zakaria, S. A. (2024). The Spatial Form of the Traditional Residences of Shanxi Merchants: A Case Study of Pingyao Ancient City, China. Buildings, 14(10), 3266. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14103266