Analysis of the Spatiotemporal Distribution Characteristics and Influencing Factors of High-Grade Cultural Heritage in the Region Surrounding Mount Song

Abstract

1. Introduction

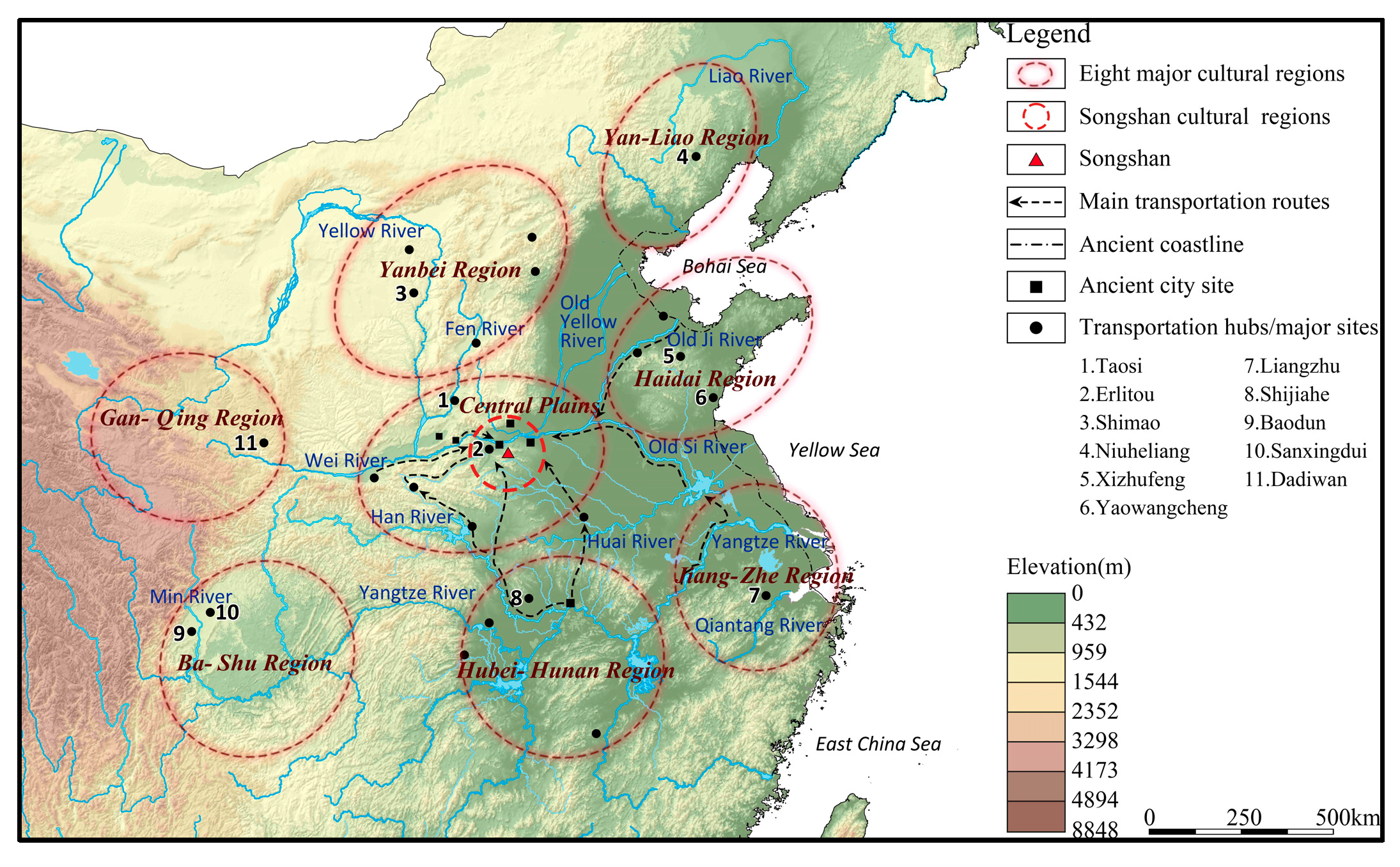

2. The Origin of Research on the Songshan Region

3. Research Area and Methods

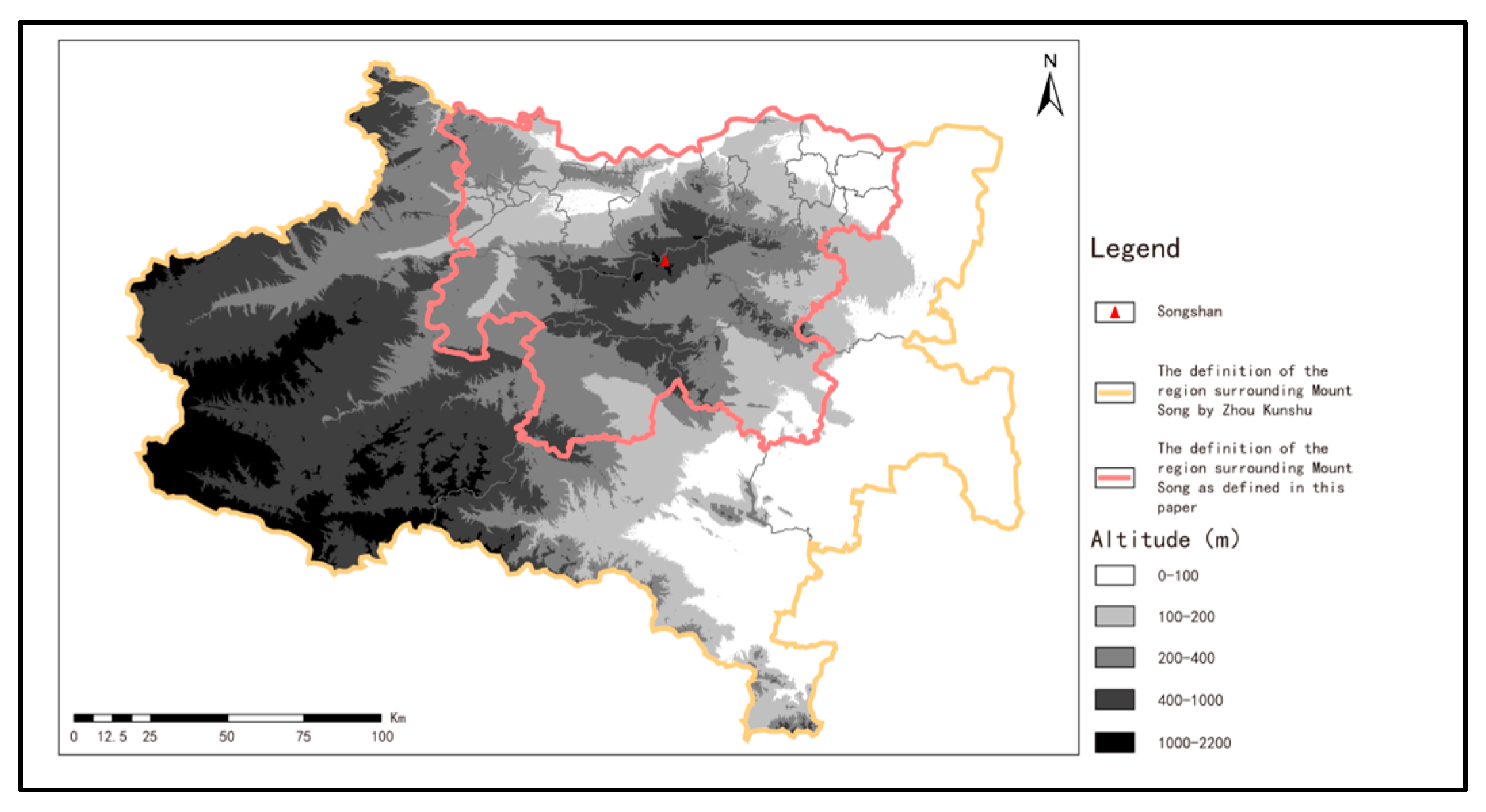

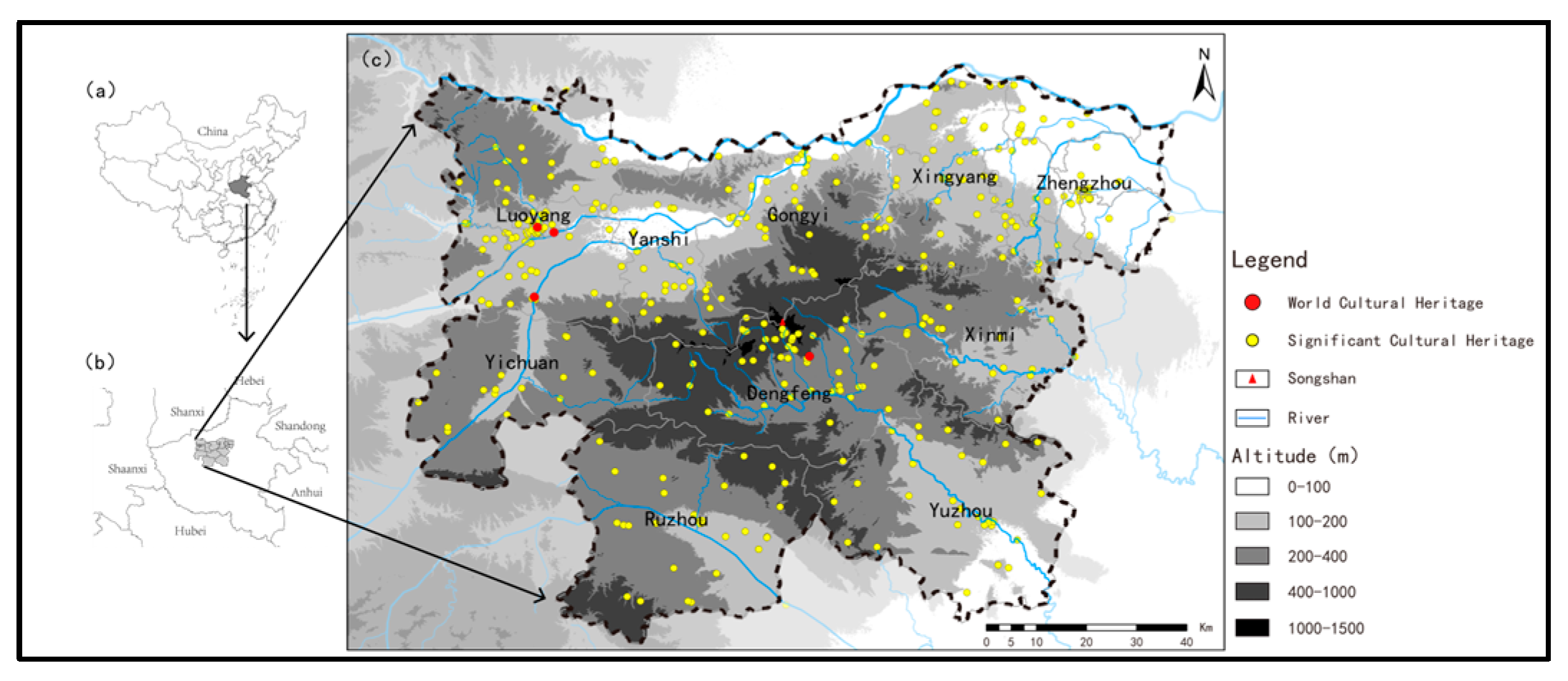

3.1. Research Area

3.2. Research Subject

3.3. Research Methods

3.3.1. Average Nearest Neighbor Ratio

3.3.2. Kernel Density Estimation

3.3.3. Buffer Analysis

3.3.4. Bivariate Correlation Analysis

3.3.5. Standard Deviational Ellipse

3.3.6. Centroid Model

4. Results

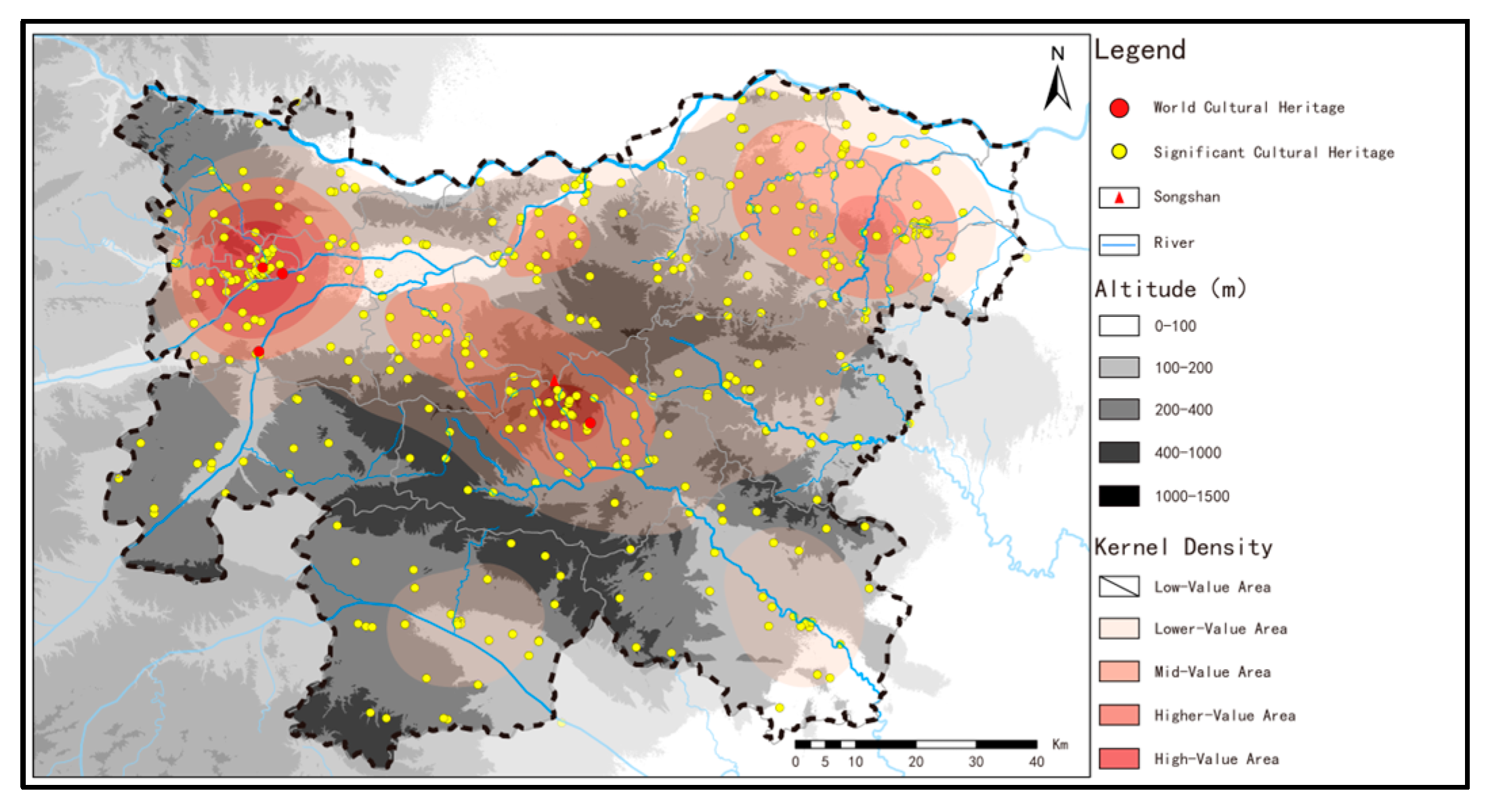

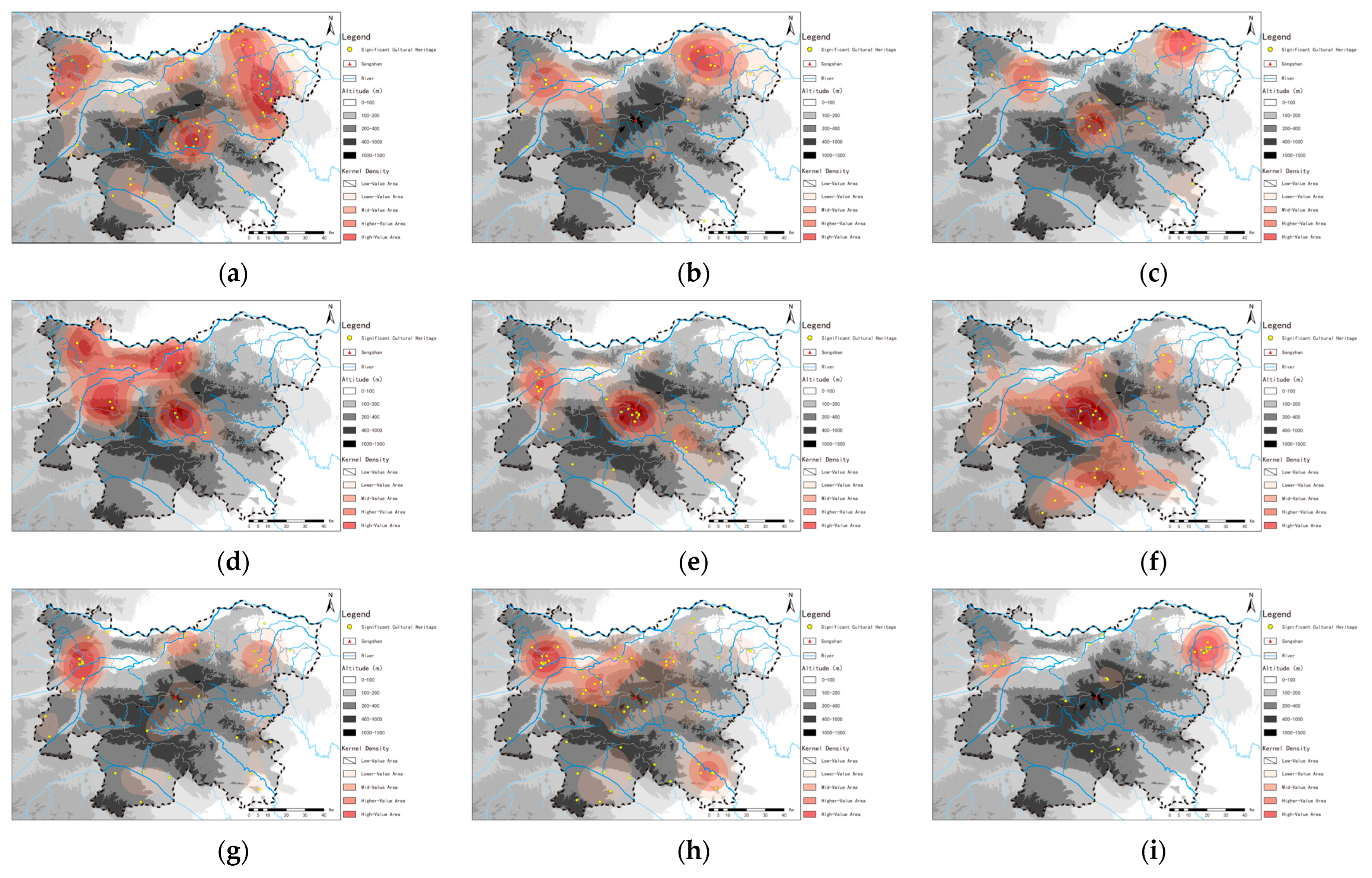

4.1. Spatiotemporal Distribution Characteristics

4.1.1. Prehistory Period

4.1.2. Pre-Qin Period

4.1.3. Qin and Han Period

4.1.4. Wei, Jin, Northern, and Southern Period

4.1.5. Sui and Tang Period

4.1.6. Song, Jin, and Yuan Period

4.1.7. Ming Dynasty

4.1.8. Qing Dynasty

4.1.9. Modern and Contemporary Times

4.2. Evolution Trends of the Centroid Model across Different Periods

5. Influence of Environmental and Cultural Factor

5.1. Innate Factors: Natural Environment

5.2. Dominant Factors

5.2.1. Political Factors and Capital Establishment

5.2.2. Cultural and Religious Factors

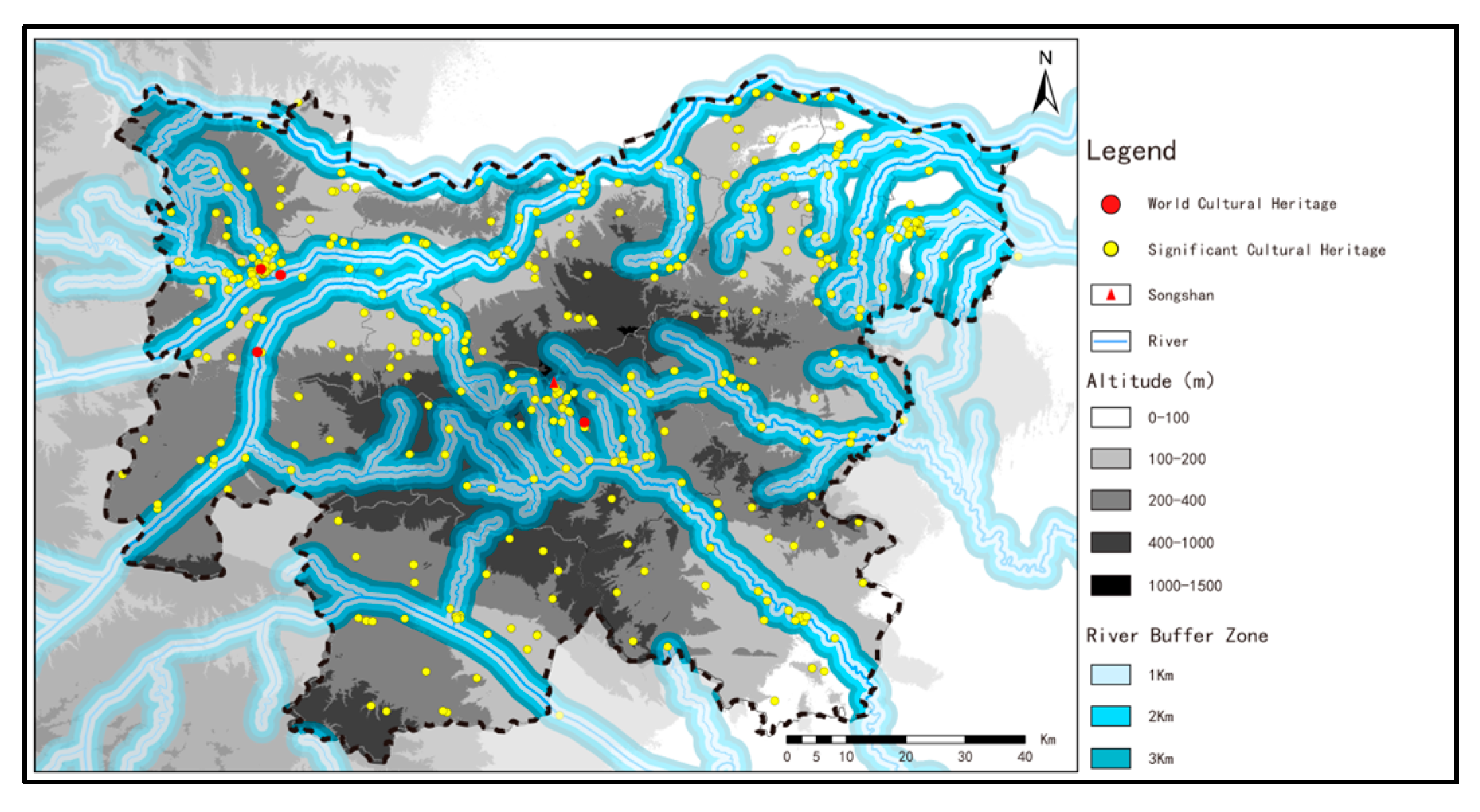

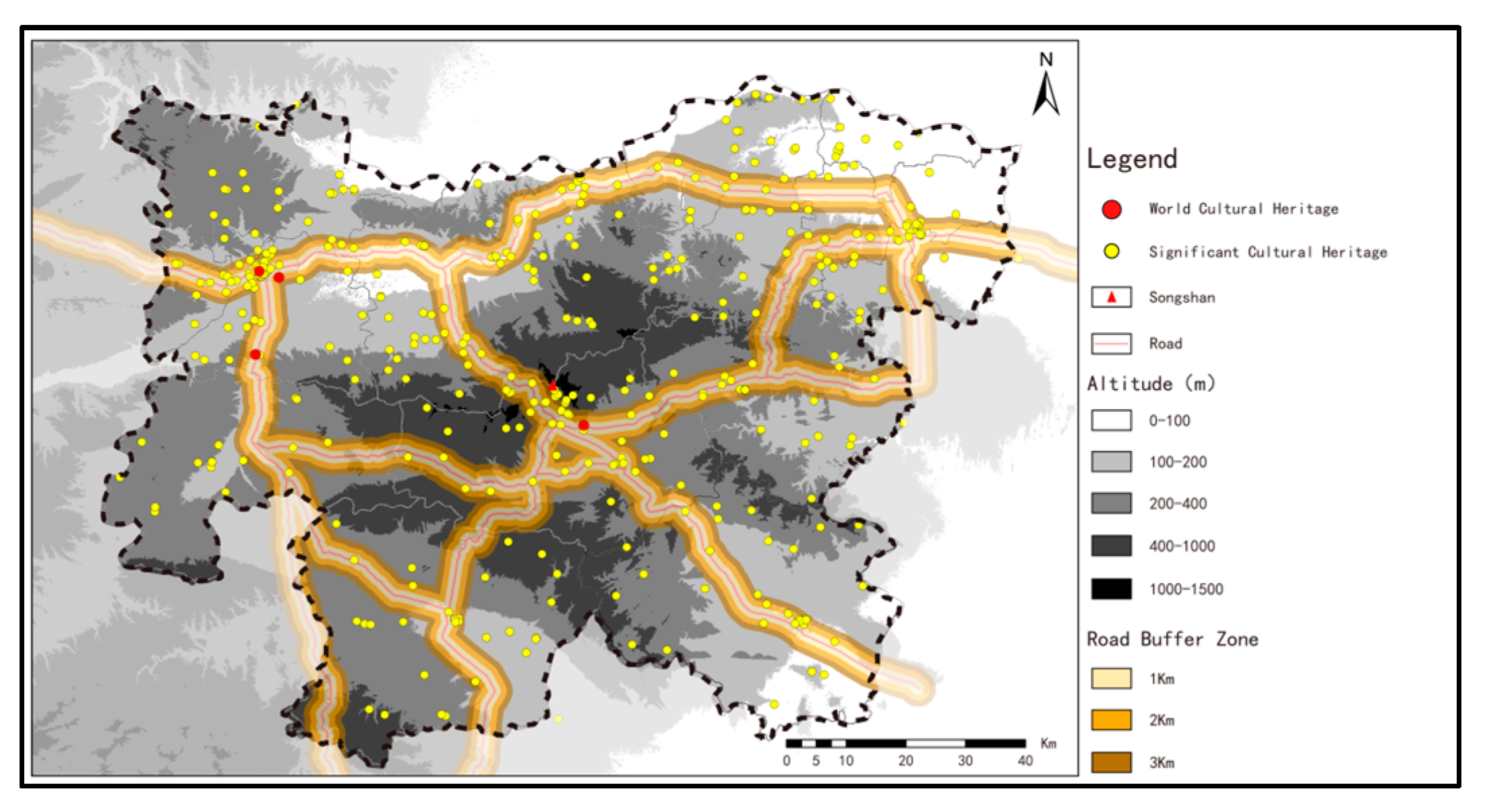

5.3. Secondary Factors

5.3.1. Land and Water Transportation

5.3.2. Fengshan Ceremony at Mount Song

5.3.3. Impact of Invasions and Upheavals on Population Density and Cultural Site Utilization

6. Conclusion and Discussion

6.1. Temporal and Spatial Patterns

6.2. Influencing Factor

6.3. Recommendations for Conservation

6.4. Methodological Reflections and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, L.; Yue, T. Towards the Contemporary Conservation of Cultural Heritages: An Overview of Their Conservation History. Heritage 2024, 7, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, L.H. Cultural Heritage and Preservation: Lessons from World War II and the Contemporary Conflict in the Middle East. Am. Arch. 2016, 79, 320–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, K.; Raff, M. The Emergence of the International Protection of Cultural Heritage. In International Law of Underwater Cultural Heritage; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, J. Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage (2003). In Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology; Smith, C., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maclaren, F.T. China: Cultural Heritage Preservation and World Heritage. In Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology; Smith, C., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Verburg, P.H.; Liu, L.; Eitelberg, D.A. Spatial Analysis of Cultural Heritage Landscapes in Rural China: Land Use Change and Its Risks for Conservation. Environ. Manag. 2016, 57, 1304–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, H.; Ma, X. Restoring ancient civilizations through cultural heritage conservation science. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2023, 66, 2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S. The development and institutional characteristics of China’s built heritage conservation legislation. Built Herit. 2022, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K. Traditional Rural Heritage Conservation in China: Policies and Theories. In A Morphological Interpretation of a Northern Chinese Traditional Village; Springer: Singapore, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Yang, S. Spatio-temporal evolution and distribution of cultural heritage sites along the Suzhou canal of China. Herit. Sci. 2023, 11, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Yang, R.; Liang, Y.; Li, W.; Chen, F. The Spatial Relationship and Evolution of World Cultural Heritage Sites and Neighbouring Towns. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, L.; Wei, Z.; Li, J.; Cheng, X. Large-scale cultural heritage conservation and utilization based on cultural ecology corridors: A case study of the Dongjiang-Hanjiang River Basin in Guangdong, China. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, J.E. Geoheritage, Geotourism and the Cultural Landscape: Enhancing the Visitor Experience and Promoting Geoconservation. Geosciences 2018, 8, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, B. Ancient Cultures, Cities, and States of Western Liaoning—Discussing the Current Priorities or Major Topics in Field Archaeology. Cult. Relics 1986, 8, 41–44. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C. Discussing the Reconstruction of Ancient History through the Progress in Archaeological Theory and Methods. Hist. Res. 2018, 6, 4–20. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Zhao, H. The ‘Chinese Civilization Exploration Project’ and Its Main Achievements. Chin. Hist. Res. 2022, 4, 5–32. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, K. Fifteen Years of Chinese Environmental Archaeology. In Environmental Archaeology Research; Zhou, K., Mo, D., Eds.; Peking University Press: Beijing, China, 2006; Volume 3, pp. 12–26. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, K.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, R.; Cai, Q.; Song, G.; Song, Y.; Mo, D.; Wang, H.; Lu, P.; et al. Discussion on the Songshan Cultural Circle. Cent. Plains Cult. Relics 2005, 1, 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, P.; Liu, W.; Yang, R.; Zhou, K.; Chen, P. Three-Dimensional Visualization Analysis of the Prehistoric Settlement Distribution and Environment in the Songshan Region. Reg. Res. Dev. 2011, 30, 157–160. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, P.; Tian, Y.; Chen, P.; Mo, D. Study on the Spatiotemporal Patterns of Prehistoric Settlement Distribution in the Songshan Region. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2016, 71, 1629–1639. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, L.; Shi, Y.; Yang, R. Study on the Division of Prehistoric Settlement Clusters in the Songshan Region. Reg. Res. Dev. 2015, 34, 172–176. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, L.; Shi, Y.; Lu, P.; Liu, C. Study on the Relationship between Settlement Site Selection and Water Systems in the Songshan Region During the Prehistoric Period. Reg. Res. Dev. 2017, 36, 169–174. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, L.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, P.; Chen, P.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X. Study of Early Settlement Size Hierarchy Based on K-means Clustering Method. Reg. Res. Dev. 2020, 39, 176–180. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, L.; Li, F.; Gu, W.; Wu, Q. Agricultural Evolution in the Songshan Region During the Longshan to Erlitou Period. Huaxia Archaeol. 2019, 3, 58–66. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, F.; Wu, Y. Rice and Power: Utilization of Rice from the Longshan to Erlitou Cultural Periods in the Songshan Region. South. Cult. Relics 2022, 2, 135–144. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, C.; Yuan, G. Research and Related Issues of Peiligang Culture from the Perspective of Scientific Archaeology. Jianghan Archaeol. 2022, 1, 97–105. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, P.; Tian, Y.; Yang, R. Settlement Size Hierarchy in the Songshan Region from 9000 aB.P.-3000 aB.P. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2012, 67, 1375–1382. [Google Scholar]

- Zhengzhou Songshan Ancient Architectural Group Declaration Office (Ed.) Songshan Historical Architectural Group; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2008; p. 241. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Chen, X. Formation of Early States in China: Discussing the Relationships between Centers and Peripheries during the Erlitou and Erligang Periods. Anc. Civiliz. 2002, 1, 71–134. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, X. Phasal Changes in China’s Prehistoric Society and the Formation of Early States. Acta Archaeol. Sin. 2020, 3, 309–336. [Google Scholar]

- State Council of the PRC. Available online: http://www.scopsr.gov.cn/ (accessed on 9 October 2024).

- Henan Provincial Administration of Cultural Heritage. Available online: http://www.wwj.henan.gov.cn (accessed on 9 October 2024).

- Yang, F.; Duan, Q.; Cheng, B.; Ren, G.; Jia, Y.; Jin, G. The Agriculture and Society in the Yiluo River Basin: Archaeobotanical Evidence from the Suyang Site. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 885837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, H. Agriculture, the Environment, and Social Complexity from the Early to Late Yangshao Periods (5000–3000 BC): Insights from Macro-Botanical Remains in North-Central China. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 9, 662391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S. (Ed.) Population Vertical Distribution Patterns and Research on the Rational Redistribution of Population in China’s Mountainous Areas; East China Normal University Press: Shanghai, China, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Henan Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology; Department of Anthropology at Missouri State University; Department of Anthropology at Washington University (Eds.) Ying River Civilization: Archaeological Survey and Research on the Upper Ying River; Elephant Press: Zhengzhou, China, 2008; p. 49. [Google Scholar]

- Haidvogl, G. Historic Milestones of Human River Uses and Ecological Impacts. In Riverine Ecosystem Management; Schmutz, S., Sendzimir, J., Eds.; Aquatic Ecology Series; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G. Leadership and Integration: The Process of Civilization in Ancient China from the Perspective of Songshan Civilization. In Research on the Origins of Chinese Civilization and Songshan Civilization; Zhengzhou China Origins and Songshan Civilization Research Association, Ed.; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2013; Volume 1, pp. 197–212. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, L.; Yang, R.; Lu, P.; Teng, F.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Chen, P.; Li, X.; Guo, L.; Zhao, D. The spatiotemporal evolution of ancient cities from the late Yangshao to Xia and Shang Dynasties in the Central Plains, China. Herit. Sci. 2021, 9, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L. The Xia-Shang-Zhou Civilization. In The History of Chinese Civilization. China Insights; Bu, X., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Cao, W. The Evolvement and Development of Luoyang. In Introduction to the Urban History of China; China Connections; Palgrave Macmillan: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luoyang Municipal Local Chronicles Compilation Committee (Ed.) Chronicles of Luoyang City, (Cultural Relics); Zhongzhou Ancient Books Publishing House: Zhengzhou, China, 1995; Volume 14, pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, C.; Cao, W. Cities During the Five Dynasties and the Ten Kingdoms Period, and the Turning Point of Chinese Urban History. In Introduction to the Urban History of China; China Connections; Palgrave Macmillan: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Z. Tang-Song or Song-Ming: The Significance of a Perspective Shift in Chinese Cultural and Intellectual History. Front. Hist. China 2006, 1, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. Discussion and Reflections on Several Issues of Heluo Culture. Zhongzhou Acad. J. 2004, 5, 146–150. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, R.J. Divination: Science, Technology, and the Mantic Arts in Traditional China. In Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures; Selin, H., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, K.N. Early Imperial Confucianism. In The Oxford Handbook of Confucianism; Oldstone-Moore, J., Ed.; Online, Edn; Oxford Academic: Oxford, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; He, Y. The Songyang Academy of Classical Learning: A Frontier of New Confucianism. In Historic Monuments of Mount Songshan; Springer: Singapore, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luoyang Municipal Local Chronicles Compilation Committee (Ed.) Chronicles of Luoyang City 1991–2000; Zhongzhou Ancient Books Publishing House: Zhengzhou, China, 2006; Volume 1, pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Zhengzhou Municipal Local Chronicles Compilation Committee (Ed.) Chronicles of Zhengzhou City, Part 1; Zhongzhou Ancient Books Publishing House: Zhengzhou, China, 1999; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Henan Provincial Transportation History Compilation Committee (Ed.) History of Road Transport in Henan; People’s Transportation Publishing House: Beijing, China, 1991; Volume 1, p. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Dengfeng Municipal Local Chronicles Compilation Committee (Ed.) Chronicles of Dengfeng City; Zhongzhou Ancient Books Publishing House: Zhengzhou, China, 2008; Volume 1, pp. 196–202. [Google Scholar]

- von Richard, G. Economic Transformation in the Tang-Song Transition (755 to 1127). In The Economic History of China: From Antiquity to the Nineteenth Century; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016; pp. 208–254. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Tian, G.; Wei, K.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, S.; Huang, Y.; Yao, X. The Influence of Environment on the Distribution Characteristics of Historical Buildings in the Songshan Region. Land 2022, 11, 2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyeon-Joo, L. The Influence of High-Speed Railroad Construction on Territorial Organization: A Case Study of the French TGV Transportation Network. J. Korean Assoc. Reg. Geogr. 2004, 10, 252–266. [Google Scholar]

| Period | Actual Nearest Neighbor Distance (km) | Theoretical Nearest Neighbor Distance (km) | Nearest Neighbor Index | Spatial Distribution Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prehistory period (1,700,000 BC to 2000 BC) | 5.70 | 6.85 | 0.831 | Relatively Clustered |

| Pre-Qin period (2000 BC to 221 BC) | 7.87 | 9.45 | 0.833 | Relatively Clustered |

| Qin and Han period (221 BC to 220 AD) | 8.80 | 12.25 | 0.718 | Clustered |

| Wei, Jin, Northern, and Southern period (220 AD to 589 AD) | 9.18 | 16.37 | 0.561 | Clustered |

| Sui and Tang period (589 AD to 960 AD) | 5.94 | 9.68 | 0.613 | Clustered |

| Song, Jin, and Yuan period (960 AD to 1368 AD) | 7.50 | 10.21 | 0.735 | Clustered |

| Ming dynasty (1368 AD to 1644 AD) | 8.38 | 9.81 | 0.855 | Relatively Clustered |

| Qing dynasty (1644 AD to 1911 AD) | 5.30 | 7.07 | 0.749 | Clustered |

| Modern and contemporary times (1911 AD to the present) | 5.46 | 9.93 | 0.550 | Clustered |

| Elevation Data | Number of High-Grade Cultural Heritage Sites |

|---|---|

| 1 (0–200 m) | 239 |

| 2 (200–400 m) | 112 |

| 3 (400–1000 m) | 32 |

| 4 (Above 1001 m) | 10 |

| River Buffer Zones | Number of High-Grade Cultural Heritage Sites |

|---|---|

| 1(0–1 km) | 139 |

| 2 (1 km–2 km) | 84 |

| 3 (2 km–3 km) | 42 |

| Road Buffer Zone | Number of High-Grade Cultural Heritage Sites |

|---|---|

| 1(0–1 km) | 88 |

| 2 (1 km–2 km) | 62 |

| 3 (2 km–3 km) | 41 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wei, F.; Sun, C.; Ma, J. Analysis of the Spatiotemporal Distribution Characteristics and Influencing Factors of High-Grade Cultural Heritage in the Region Surrounding Mount Song. Buildings 2024, 14, 3259. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14103259

Wei F, Sun C, Ma J. Analysis of the Spatiotemporal Distribution Characteristics and Influencing Factors of High-Grade Cultural Heritage in the Region Surrounding Mount Song. Buildings. 2024; 14(10):3259. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14103259

Chicago/Turabian StyleWei, Feng, Chang Sun, and Jiaming Ma. 2024. "Analysis of the Spatiotemporal Distribution Characteristics and Influencing Factors of High-Grade Cultural Heritage in the Region Surrounding Mount Song" Buildings 14, no. 10: 3259. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14103259

APA StyleWei, F., Sun, C., & Ma, J. (2024). Analysis of the Spatiotemporal Distribution Characteristics and Influencing Factors of High-Grade Cultural Heritage in the Region Surrounding Mount Song. Buildings, 14(10), 3259. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14103259