Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic brought challenges such as social distancing, health fears, reduced interaction, and increased stress for construction workers. Understanding their changing social and psychological states is crucial for effective management and performance. This study investigated the impact of the pandemic on the managers’ and laborers’ social and psychological well-being states and identified the changes in their social and psychological well-being states affecting project performance before and after the pandemic. Construction professionals, including construction managers, superintendents, and laborers, participated in a survey exploring thirteen social and psychological well-being variables and three performance variables. Data analysis involved paired t-tests and multiple regression. The findings revealed increased levels of anxiety and depression among both managers and laborers after the pandemic, with laborers more severely affected. Managers considered a broader range of variables, while laborers primarily focused on social factors influencing project performance. These disparities suggested that managers should prioritize health and safety measures, fair compensation, team cohesion, and stress management, while laborers’ motivation, work environment, knowledge acquisition, and sense of belonging should receive priority attention. This study contributes to providing managerial implications and guidance for improving the construction workforce, including managers’ and site laborers’ performance in the post-pandemic period.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly impacted the construction industry, much like other industries. One prominent effect has been the disruption of supply chains, which severely impacted construction projects [1,2]. According to a survey conducted by the Associated General Contractors of America (AGC), 28 percent of their members reported halting or delaying projects in the United States due to COVID-19 [3]. The closure of factories, transportation restrictions, and workforce limitations resulted in delays in acquiring crucial construction materials such as steel, lumber, and concrete, leading to substantial increases in material costs, sometimes reaching over 150%. Consequently, project budgets and financing faced immense strain. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic profoundly affected construction activities, causing project delays and disruptions. With new safety protocols in place, construction sites had to implement measures such as face mask mandates and social distancing guidelines to protect workers’ health. While these safety measures were crucial to prevent virus transmission, they resulted in reduced on-site workforce capacity and increased logistical challenges [1,2]. Moreover, localized lockdowns and quarantine requirements often forced construction sites to temporarily suspend their operations, further extending project timelines. Construction companies faced logistical complexities and struggled to maintain productivity while adhering to the necessary safety measures. As a result, numerous construction projects experienced delays, impacting completion timelines and, in some cases, leading to financial penalties and contractual disputes with clients.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic extends beyond construction projects themselves and has also affected the mental well-being of the construction workforce. The virus and its associated impacts, such as physical separation, fear of infection, and the loss of employment, have taken a toll on the mental well-being of workers [1,2]. Many construction workers experienced heightened levels of stress, anxiety, and depression, often leading to post-traumatic stress disorders. The pandemic has disrupted their everyday lifestyle and priorities, altering their perspective on work and raising concerns about their safety and livelihood [4]. Moreover, the social stigma and discrimination related to the virus have further exacerbated the psychological strain on construction workers. These psychological impacts had direct consequences on project performance, as workers’ mental health greatly influenced their motivation, focus, and ability to work efficiently. Thus, the construction industry needs to address these challenges by prioritizing not only logistical and operational aspects but also the mental health and social support of its workforce [5].

While researchers have recognized the importance of investigating the short and long-term effects of the pandemic on various workforce aspects, including project and workplace considerations, procurement, supply chain implications, and legal and insurance matters [2,4], there is a notable knowledge gap in providing comprehensive answers to two crucial research questions: (1) how has the COVID-19 pandemic impacted the changes in the social and psychological well-being, as perceived by managers and laborers in the construction industry?; (2) what changes have occurred in the influential social and psychological well-being variables affecting project performance, as perceived by managers and laborers, due to the COVID-19 pandemic? Addressing this gap is essential to gain a comprehensive understanding of the pandemic’s impact on the construction workforce and to develop informed strategies for effectively managing future crises.

To address these research questions, this study investigates the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the managers’ and laborers’ social and psychological well-being states and identifies the changes in their social and psychological well-being states affecting project performance before and after the pandemic. Data were collected through questionnaires administered to construction workers, including laborers, superintendents, and construction managers, focusing on selected social and psychological well-being variables. In this study, Paired t-test analysis was employed to examine the differences in the social and psychological well-being of construction workers before and after the pandemic, enabling a direct comparison of the effects caused by COVID-19. In addition, multiple regression analysis was used for the assessment of changes in influential social and psychological well-being variables affecting project performance before and after the COVID-19 pandemic. This statistical approach enables the identification of specific variables that have a significant impact on project performance during and after the crisis, helping to pinpoint crucial factors to be addressed in improving project outcomes in the post-pandemic period. By incorporating these robust statistical analyses into the research methodology, the study gains a deeper understanding of how the pandemic has influenced construction workers’ well-being and project performance. The insights obtained from these analyses will serve as the basis for developing informed managerial implications aimed at enhancing project performance and promoting a resilient and supportive work environment in the construction industry after the pandemic.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The next section reviews the literature on the changes in the construction industry and the social/psychological states caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Then, the research methodology, including the variable selection, data collection, and statistical techniques used in this study, is described. The analysis results are provided, followed by discussions and conclusions.

2. Literature Review

The construction industry serves as a significant economic force due to its extensive interconnections with various sectors, including manufacturing, finance, and real estate [6]. These interconnections contribute to the industry’s immense impact, accounting for approximately 13% of global GDP. Moreover, projections indicate that global construction spending will witness a substantial increase of over 70%, reaching a staggering $15 trillion by 2025 [7,8]. In the United States alone, the construction industry employs around 4.7% of the workforce, highlighting its crucial role in both global and national economies [9]. However, the construction sector is characterized by project-based, one-off approaches involving complex and uncertain endeavors. Construction projects are unique and involve the integration of diverse elements, making standardization challenging. Uncertainty arises from various factors, including weather conditions, regulatory changes, and unexpected site conditions, along with involvement from multiple stakeholders with diverse perspectives. Supply chain disruptions and economic fluctuations add to the unpredictability. To succeed in this dynamic industry, construction companies must rely on experience, adaptability, and effective project management to navigate these complexities. Mitigation strategies and contingency plans are crucial to ensure project delivery and client satisfaction. Additionally, the construction industry heavily relies on labor skills and talent, making effective labor supervision a critical factor in driving performance [6,10].

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly impacted every facet of the construction process, leading to a wide array of challenges and disruptions. One notable consequence is the increased occurrence of contract and project notices for default as companies grapple with financial uncertainties and disruptions caused by the pandemic [11]. To accommodate workforce limitations and adhere to social distancing measures, scheduling adjustments have become necessary, resulting in project delays and the need to resequence activities. Additionally, unforeseen circumstances have led to project suspensions and terminations, prompting companies to reassess their project portfolio and financial viability [11,12]. Reinstating suspended projects has proven complex, demanding careful planning and coordination to ensure a seamless resumption of work. Furthermore, global disruptions have worsened material and supply chain delays, making it challenging to procure essential construction materials and causing cost fluctuations [1,2]. The construction industry has faced an array of unprecedented challenges, requiring adaptability, resilience, and strategic planning to navigate through these disruptions successfully.

Beyond the direct implications on construction projects, the COVID-19 pandemic has had a far-reaching impact on construction workers. Construction workers have been exposed to mental health challenges as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic [2,4,13]. Their increased vulnerability to the virus due to their physical presence at construction sites has created a constant fear of infection, leading to heightened stress and anxiety. The pandemic-induced physical separation and isolation have further exacerbated their feelings of loneliness and disconnection from their social support networks, adding to their psychological burden. Moreover, the social stigma surrounding the virus has caused construction workers to face discrimination and marginalization, which can significantly impact their mental well-being. As a consequence of these stressors, various mental health issues have become increasingly prevalent among construction workers. Conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PSTD), anxiety, depression, and insomnia have surfaced, affecting their ability to cope with the challenges posed by the pandemic. The constant fear of contracting the virus, witnessing its effects on colleagues and loved ones, and the uncertainty surrounding their job security have contributed to the development of these mental health problems. These issues not only impact their overall well-being but can also impair their job performance and productivity. Moreover, the pandemic has caused a shift in construction workers’ perceptions of the world and their psychological outlook on the construction industry itself [9]. The disruption caused by the pandemic has forced workers to reevaluate their priorities and confront the uncertainties of their profession, potentially affecting their sense of job satisfaction and motivation. As the pandemic brought unprecedented challenges to the construction sector, understanding these changes in workers’ perspectives is crucial to developing targeted interventions and support mechanisms.

In the construction industry, effective communication and social interaction among workers is crucial for achieving project goals. Social interaction theory posits that people’s behaviors are shaped by the social environment around them and that social interaction occurs when one person’s behavior influences another’s [14]. Therefore, the ability of workers to interact and communicate with each other is essential for building relationships and making progress on construction projects. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted this crucial aspect of construction work due to the implementation of social distancing and safety measures [1,2]. Reduced site activities due to social distancing requirements have led to a decrease in the number of workers allowed on site at any given time. This reduction in the workforce can result in slower progress and increased project timelines, as there are fewer hands available to carry out tasks. Additionally, some tasks may require close collaboration between workers, which may not be possible under strict social distancing guidelines, leading to delays and coordination issues. The restrictions on social gatherings have also disrupted the usual communication and collaboration among construction teams. Construction sites are known for being places of constant communication, problem-solving, and decision-making. However, with limited social gatherings, it has become challenging to conduct meetings, discussions, and problem-solving sessions effectively. This can lead to miscommunication, difficulties in resolving issues, and a less cohesive workflow, affecting the overall efficiency of the project. Moreover, limited social interaction and restricted communication opportunities have detrimental consequences on the psychological well-being of construction workers. The lack of social interaction can lead to feelings of isolation and disconnection, which can impact their motivation and overall performance [1,3,9]. The strain of adapting to new communication methods, such as virtual platforms, can also lead to misunderstandings and delays in information sharing, hindering effective coordination among workers. These limitations and challenges have a cascading effect on teamwork, collaboration, and coordination among construction workers. Teamwork and effective communication are essential for successful project execution, and the disruption caused by social distancing and safety measures can hinder the seamless flow of information and decision-making processes.

In addition to the challenges related to social interaction, the cognitive and behavioral aspects of construction workers have also been significantly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Effective decision-making skills and cognitive thinking are critical components in the construction industry, as they guide individuals in planning, scheduling, controlling, and managing project activities. The cognitive theory highlights the influence of the social environment on motivation, learning, and self-regulation, underscoring the need for managerial implications and practices that can enhance worker performance in the face of pandemic-induced changes [15]. However, the pandemic’s introduction of new safety measures and guidelines has posed unique challenges for workers, ultimately impacting their performance [7]. Thus, it becomes essential to study the social and psychological impacts of the pandemic on the construction workforce to gain a comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing performance [15].

Researchers have emphasized the need to investigate the short-and long-term effects of the pandemic on various aspects of the workforce, including project and workplace considerations, procurement, supply chain implications, and legal and insurance aspects [2,9,11]. However, a notable knowledge gap exists in understanding the impact of the pandemic on the social and psychological well-being of the workforce, particularly on the distinct differences between managers and laborers in construction projects. Additionally, there is a lack of research exploring the specific changes in influential social and psychological variables affecting project performance from their perspectives. Understanding these impacts is of utmost importance as it can optimize project outcomes and guide management practices in the construction industry. By comprehensively examining the challenges faced by construction workers during this unprecedented crisis, informed strategies can be developed to foster a resilient and supportive work environment. This approach will not only promote worker well-being but also enhance overall productivity and the successful execution of construction projects in the face of uncertainty. Moreover, addressing the knowledge gap will enable construction companies to effectively manage future pandemics or similar disruptions, making the industry more adaptable and prepared for unforeseen challenges. Given the significance of these impacts on construction workforce well-being and project performance, it is required to delve into the social and psychological effects of the pandemic on managers and laborers and the changes in influential variables affecting project performance from their perspective.

3. Methodology

This section describes the research model, including the variable selection and analysis model, followed by an explanation of the data collection process and the statistical techniques employed for data analysis.

3.1. Research Model

The pandemic has introduced unprecedented challenges and disruptions, affecting the overall well-being of workers and potentially influencing their performance on construction projects. The social environment encompasses communication, collaboration, and relationships among workers, which are essential for achieving project goals. When workers are unable to interact effectively, or experience strained social interactions due to the pandemic’s restrictions, it can lead to decreased productivity, reduced teamwork, and ultimately impact the success of the project. Moreover, the psychological well-being of workers, including their mental health, motivation, and perception of the industry, can significantly affect their engagement, decision-making abilities, and overall job performance. The COVID-19 pandemic has brought about unique psychological challenges for construction workers, such as increased anxiety, stress, and uncertainty due to factors like exposure to the virus, physical separation, and job losses. These psychological factors can impact overall project performance.

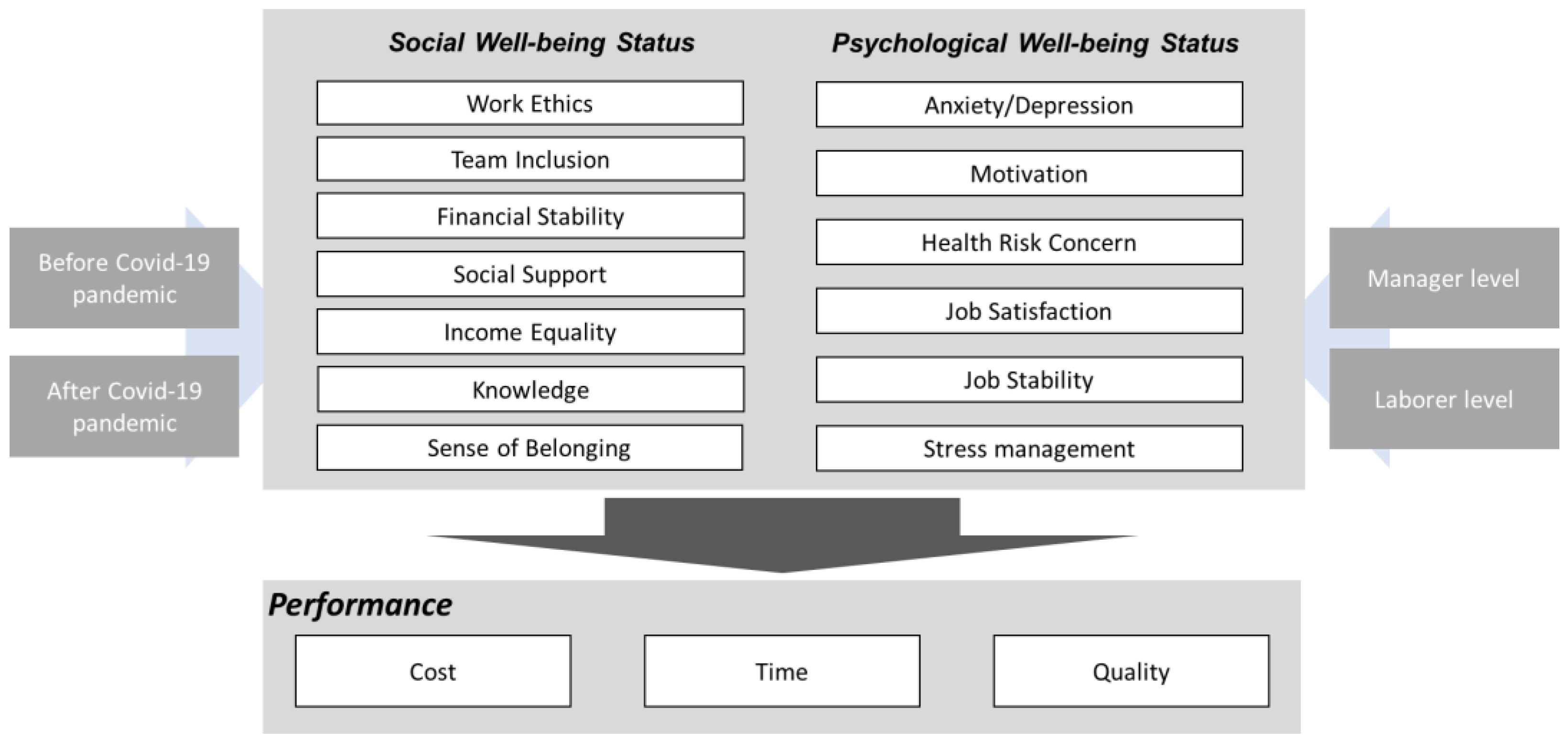

In this study, seven social well-being variables and six psychological well-being variables were chosen based on their relevance to the challenges and disruptions caused by the pandemic and their potential influence on the construction workforce and project outcomes. The social well-being variables encompass the state of an individual’s social connections, relationships, and interactions with others in their community and society. ‘Work ethics’ and ‘team inclusion’ are crucial in determining the level of cooperation and collaboration among workers, which may have been disrupted due to remote work arrangements or social distancing measures. ‘Financial stability’ reflects the impact of the pandemic on workers’ economic security, while ‘social support’ and ‘sense of belonging’ are essential in gauging the support system and sense of community that workers have during such challenging times. ‘Income equality’ is relevant to understand any disparities in pay and benefits that might have arisen due to the pandemic’s effects. Lastly, ‘knowledge’ represents workers’ access to information and resources needed to adapt to changes in work processes brought about by the pandemic. Psychological well-being, on the other hand, pertains to an individual’s mental and emotional state, encompassing their psychological functioning and overall emotional health. ‘Anxiety and depression’ may have increased due to uncertainties related to job security, financial stress, and changes in work dynamics. ‘Motivation’ may have been affected by the challenges posed by the pandemic and the need to adapt to new work practices. ‘Health risk concerns’ reflect workers’ awareness and apprehensions regarding potential exposure to the virus in their work environment. ‘Job satisfaction’ and ‘job stability’ are essential factors in understanding workers’ contentment with their work and the stability of their employment during the pandemic. ‘Stress management’ (as shown in Table 1) is relevant to assess how workers cope with the increased stressors and pressures during the pandemic. To comprehensively examine the impact of social and psychological states on distinct aspects of project performance, this study utilizes multiple performance variables, including ‘cost’, ‘time’, and ‘quality’.

Table 1.

Definition of selected variables.

Figure 1 shows the research model of this study. Construction projects involve a diverse group of individuals, including managers and laborers, who work together to achieve project objectives. Managers are responsible for overseeing project planning, resource allocation, and decision-making. Their ability to manage the uncertainties and complexities brought about by the pandemic influences cost management and timeframes for project completion. If managers face heightened stress and reduced decision-making capabilities due to the pandemic’s pressures, it may lead to delays, increased costs, and compromised project quality. Additionally, managers’ role in maintaining effective communication with teams is crucial for successful project execution. Clear communication channels are essential for conveying project objectives, coordinating tasks, and addressing any issues promptly. If communication is strained or compromised during the pandemic, it can lead to misunderstandings, reduced collaboration, and decreased productivity among workers, directly affecting project outcomes. On the other hand, laborers play a hands-on role in executing construction tasks on-site. Their responsibilities often require physical labor and adherence to safety protocols. Therefore, the psychological states of laborers significantly impact their productivity, performance, and adherence to safety protocols. The pandemic’s health risks and uncertainties may lead to heightened anxiety and fear among laborers, potentially affecting their focus and job performance. Reduced social interactions and feelings of isolation due to social distancing measures can lead to decreased morale and job satisfaction, affecting their motivation and overall work quality. Furthermore, the physical nature of laborers’ responsibilities puts them at a higher risk of exposure to health hazards, making it crucial to address their psychological well-being and provide appropriate support to ensure their safety and productivity. By considering both viewpoints, we can understand the diverse factors at play and tailor interventions and strategies accordingly. Addressing the distinct social and psychological needs of both groups allows for the implementation of targeted interventions, such as stress management support for managers and mental health resources for laborers, ultimately enhancing the overall effectiveness and resilience of the construction workforce.

Figure 1.

Research model.

In this respect, this study hypothesizes the followings: (1) there is a significant impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the changes in the social and psychological well-being of managers and laborers in the construction industry; (2) there is a significant change in the influential social and psychological well-being variables affecting project performance, as perceived by managers and laborers in the construction industry, due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

3.2. Data Collection

The questionnaire survey was conducted on randomly selected construction companies in Minneapolis, Minnesota, which is the closest metropolitan city where a ton of construction companies have their firm situated. The questionnaire was devised to investigate the participant’s relative states of the selected social and psychological variables and their relative deemed project performance before and after the pandemic. The questionnaire used a 5-point Likert scale (ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”) to assess social and psychological variables. The questions included: (1) My work ethic is excellent; (2) I enjoy being a part of the team; (3) My financial status (income and revenue) is stable; (4) The support from friends and family for my well-being is encouraging; (5) There is an even distribution of income among work colleagues and individuals; (6) I am knowledgeable about the construction process; (7) I have support from my team member; (8) I often feel anxiety and depression on the job; (9) My motivation to work on the job is outstanding; (10) I am concerned about my health on the job; (11) I am satisfied with my job and its provisions for me; (12) I am confident of my job status and my ability to keep my job; and (13) Time off was provided to avoid burnout and improve stress management. The questionnaire for performance also used a 5-point Likert scale (unacceptable, poor, fair, good, and very good), and the questions are as follows: (1) the project is within the budget; (2) the project is on the schedule; and (3) the project meets the required quality. With the questionnaire, the data were collected in two ways to ensure proper representation for all parties involved, such as laborers, superintendents, and construction managers. For construction managers, who primarily operate in office settings, an online survey method through Qualtrics was employed. This online platform allowed them to respond to the questionnaire conveniently and flexibly, accommodating their busy schedules and providing accessibility from any location with internet connectivity. On the other hand, for superintendents and laborers actively engaged on construction sites, where internet access might be limited, a paper-based survey method was used. By distributing paper surveys directly to these on-site workers, we ensured their inclusion and participation in the study. By employing a combination of online surveys and paper-based surveys, this study ensured that each group’s representation was maximized. The period of collection of data spanned from 5 March 2022 to 10 April 2022. We distributed the survey questionnaire to 90 construction workers, and 63 participants, including seven superintendents, twenty-five construction managers, and thirty-one laborers, responded. The overall response rate was 70%. The detailed profile of survey participants is described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Profile of survey participants.

3.3. Statistical Techniques

In this study, a paired t-test was conducted to compare the mean differences in the social and psychological states of construction workers before and after the COVID-19 pandemic. To ensure that the sample size was adequate and the difference between each pair of values was normally distributed, a Shapiro-Wilk normality test was conducted. The results indicated that the differences between the pairs were normally distributed. Additionally, multiple regression analysis was employed to determine the most impactful social and psychological variables on project performance. Multiple regression analysis is a statistical method used to estimate the relationship between a dependent variable and independent variables. Thirteen social and psychological variables and three performance variables were used as independent and dependent variables, respectively, and gender and years of industry experience were used as constant variables to control other important factors that may affect performance. This study used the beta coefficient, which is the standardized coefficient of each independent variable.

4. Results and Discussions

This section examines the impact of COVID-19 on the social and psychological well-being states of construction workers and explores the changes in the social and psychological well-being states affecting project performance before and after the pandemic. Subsequently, managerial implications derived from the analysis results are discussed.

4.1. Differences in Social/Psychological Well-Being States before and after the COVID-19 Pandemic

This study conducted paired t-tests for all variables before and after the pandemic from the perspectives of both managers and laborers to investigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the social and psychological well-being of construction workers. As shown in Table 3, the analysis results demonstrate that managers experienced statistically significant increases in anxiety and depression levels at a 95% level of significance following the pandemic. Prior to the pandemic, the mean score for ‘anxiety and depression’ was 2.85 with a standard deviation of 1.282. However, after the pandemic, the mean score increased to 3.53 with a standard deviation of 1.376, representing a statistically significant difference with a p-value of 0.011. These findings are consistent with previous research indicating that the prevalence of depressive symptoms in the US increased threefold during the pandemic. The initial fear and anxiety of workers about the health and safety of their loved ones during the pandemic were compounded by the isolation resulting from stay-at-home orders. The news of a colleague testing positive for COVID-19 further contributed to depression and anxiety. Even though COVID-19 restrictions such as social distancing and mask mandates have been lifted, workers may still be experiencing anxiety and depression because of the trauma they have experienced during the pandemic.

Table 3.

Differences in social/psychological states of construction managers before and after the pandemic.

The analysis results related to laborers’ experiences before and after the COVID-19 pandemic provide valuable insights into the significant impact of the pandemic on their mental well-being and health risk concerns. Before the pandemic, the mean score for ‘anxiety and depression’ was 2.97 with a standard deviation of 1.149. However, after the pandemic, the mean score increased to 4.28 with a standard deviation of 0.88. The corresponding p-value of 0.000 indicates that this difference is statistically significant. This means that laborers responded that they experienced anxiety and depression after the pandemic. When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, and everyone was forced to stay at home, they were isolated from their friends and family, increasing fear and anxiety about whether their loved ones were infected with COVID-19 [46]. Laborers can also be depressed upon the news of a colleague that is tested COVID-19 positive. Moreover, laborers’ ‘health risk concerns’ also showed a significant change after the pandemic [47]. Before the pandemic, the mean score for ‘health risk concerns’ was 3.83, with a standard deviation of 1.23. After the pandemic, the mean score increased to 4.38 with a standard deviation of 0.73, signifying a statistically significant difference with a p-value of 0.018. This highlights a notable shift in laborers’ perceptions of health risks during the pandemic. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, laborers’ day-to-day activities involved going outside, doing hard labor and keeping busy with one or two other duties. However, all these activities were temporarily halted during the COVID-19 pandemic when everyone was asked to stay at home. Laborers that used to burn fat from their day-to-day activities gained fat from sitting idle during the lockdown. Sitting idle for more than two or more consecutive days is associated with an increased risk of heart disease, diabetes, and the cause of immature death. In this regard, laborers are increasingly concerned about their health risks.

4.2. Changes in Social/Psychological Well-Being States Affecting Performance before and after the COVID-19 Pandemic

The study analyzed and compared the influential social and psychological well-being variables affecting performance before and after the COVID-19 pandemic, as perceived by managers and laborers. Multiple regression analyses were conducted separately on cost, time, and quality for both managers and laborers, before and after the pandemic. Before performing the regression analysis, the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) was used to assess potential multicollinearity among the predictor variables. Multicollinearity is considered acceptable when VIF values range between 1 and 10. As shown in Table 4, Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7, the results of this study showed that all VIF values were within this acceptable range, indicating that multicollinearity does not exist among the predictor variables. Furthermore, to detect autocorrelation in the regression models’ output, Durbin-Watson’s residual tests were employed. A value of Durbin-Watson close to 2 is considered appropriate, whereas a value closer to 0 or 4 is considered inappropriate. In this study, the Durbin-Watson statistics were found to be close to 2, signifying no significant autocorrelation in the regression models’ residuals, as shown in Table 4, Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7. These tests provide confidence in the validity of the regression models used in the study. Therefore, the regression analysis results can be considered robust and trustworthy, providing insights into the relationship between predictor variables and cost, time, and quality outcomes.

Table 4.

Impact of managers’ social/psychological states on performance before the pandemic.

Table 5.

Impact of laborers’ social/psychological states on performance before the pandemic.

Table 6.

Impact of managers’ social/psychological states on performance after the pandemic.

Table 7.

Impact of Laborers’ social/psychological states on performance after the pandemic.

Table 4 shows the impact of social and psychological well-being variables on project performance, as perceived by managers before the COVID-19 pandemic. The analysis results indicate that, according to managers, having ‘knowledge’ significantly impacted quality performance, with a p-value of 0.013. As project leaders, it is their responsibility to ensure that the project is headed in the right direction and produces high-quality results. Thus, possessing knowledge about the project is essential for enhancing performance. Before the pandemic, numerous literature sources emphasized the importance of motivation, knowledge, and financial stability in managers’ social and psychological well-being and job performance. Encouragement is directed toward managers, making motivation critical [23]. Motivation is the key to unlocking subordinates’ potential to achieve organizational goals and objectives, driving employees to perform their best and utilize their skills for success. This applies to managers on construction projects as they must stay motivated to carry out their duties effectively. Furthermore, financial stability is crucial for job performance, providing individuals with the confidence to meet their financial obligations, pursue their passions, and focus on their work without added stress. By achieving financial freedom, workers can concentrate on their tasks and perform better to accomplish their objectives.

Table 5 presents the impact of social and psychological well-being variables on project performance, as perceived by laborers before the COVID-19 pandemic. The analysis results from the laborers’ perspective indicated that none of the social and psychological variables had an impact on their performance before the pandemic. This means that, according to the laborers’ perceptions, variables related to social and psychological well-being did not play a significant role in influencing their project performance before the COVID-19 pandemic. It is plausible that laborers may have been primarily focused on other factors that they perceived as more influential in determining their project performance, such as physical aspects of their work environment, technical skills, or resource availability. It is essential to consider that the survey was conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic, which might have influenced the laborers’ perspectives. Over time, laborers may have developed coping mechanisms or adapted to their work conditions, which could lead them to perceive social and psychological variables as less influential on their performance.

Table 6 illustrates the impact of social and psychological well-being variables on project performance after the COVID-19 pandemic, as perceived by managers. Managers reported that ‘income equality’ had a significant impact on-time performance, with a p-value of 0.012. Typically, managers’ income is based on their skill, position, and relevant experience, and they are well-compensated, which may lead them to be less concerned with income distribution [4]. This, in turn, enables them to focus more on project tasks, reducing their worry about financial stability. Effective scheduling and change order approvals are critical for project time performance, and managers’ proficiency in handling them is essential to avoid project delays [39]. Therefore, being less worried about income equality and earnings allows managers to concentrate more on their duties, improving project performance [5]. The analysis revealed that knowledge’ significantly impacted the quality performance of construction projects with a p-value of 0.018. From the managers’ perspective, having adequate knowledge about the construction process is essential to improve quality performance. As managers are responsible for making critical decisions and strategic planning, having comprehensive knowledge about construction processes is vital. A manager with adequate knowledge is likely to achieve better performance, while a manager with less knowledge may lead to lower performance [26].

‘Sense of belonging’ was also found to have a significant effect on-time performance, with a p-value of 0.031. When managers feel supported by their team, they are more likely to take calculated risks that can lead to innovation. This innovation, in turn, can improve the proficiency of construction managers and help save time on tasks that would otherwise be time-consuming, both during and before the COVID-19 pandemic. Collaborative problem-solving also tends to produce better results [48] and working as part of a team promotes personal development, which ultimately strengthens performance [11]. Thus, the study suggests that support from team members plays a significant role in the time performance of construction projects.

Notably, ‘health risk concerns’ significantly affected both cost and time performances, with p-values of 0.014 and 0.018, respectively. The fear of contracting COVID-19 led managers to adopt more efficient management strategies, such as minimizing contact with others and managing resources more effectively, to ensure timely completion of projects and reduce costs [1,2,9]. Working alone and at their own pace also reduced idle time and allowed managers to focus on their tasks, leading to increased productivity [12]. These changes in work habits resulted in an effective cost-performance management system in the post-pandemic period [5]. Moreover, the heightened sense of personal responsibility for health and safety led managers to work more efficiently, focusing on the completion of tasks and meeting deadlines [32]. This increased productivity resulted in an improvement in time performance, as managers reduced idle time and completed tasks more effectively.

Furthermore, ‘job stability’ played a significant role in both the time and quality performance of construction projects, with a p-value of 0.011 and 0.012, respectively. Managers who have job stability and a future at the company tend to be more focused and committed to their work, which leads to improved time and quality performance [39]. Additionally, job stability is linked to financial well-being and social status, which can further motivate managers to perform better. After the pandemic, managers with job security were more inclined to ensure the timely completion of the project by allowing laborers to work more, leading to better time performance of the project [38]. Moreover, job stability has an impact on team and organizational performance. Insecure job environments can cause individuals to lose faith in the future and negatively affect performance. Conversely, managers who have job security are more likely to be motivated and committed to their duties, resulting in better quality performance overall [25].

‘Stress management’ significantly impacted the time performance of construction project managers, with a p-value of 0.005. Effective stress management strategies have been shown to positively influence job satisfaction and reduce stress levels, ultimately resulting in improved project performance [49]. Provisions for stress management, such as paid time off, rest areas in the office, and allowing workers to have more autonomy, have been found to boost productivity and time performance on projects [50].

Table 7 illustrates the impact of social and psychological well-being variables on project performance after the COVID-19 pandemic, as perceived by laborers. According to laborers’ perspectives, ‘financial stability’ affected the time and quality performances of construction projects, with a p-value of 0.02 and 0.035, respectively. The financial motivation of laborers has been suggested as one of the major factors that can stimulate performance in the construction industry as this helps to increase their time on the job, allowing for payment of overtime, thus improving their finances [51]. Most construction laborers motivate themselves by thinking about how they would spend the money they earn. This motivation brings a better performance rate in terms of time and quality.

Moreover, the study found a significant impact of ‘income equality’ on the quality performance of construction projects, with a p-value of 0.019. Ref. [52] suggests that an individual’s income and how it compares to others affect their happiness levels. The COVID-19 pandemic caused laborers in the Midwest region of the United States to struggle financially during the lockdown, making them realize their low earnings, which affected their work motivation [38]. Nonetheless, certain construction firms responded to the demand for skilled labor by increasing wages and salaries by approximately 6% compared to the previous year, particularly in the post-pandemic period [4]. Such an increase could help enhance laborers’ job focus, resulting in an improvement in on-site work quality.

The impact of ‘knowledge’ on cost and time performance was found to be significant, with p-values of 0.025 and 0.004, respectively. Adequate knowledge of the construction process can prevent laborers from repeating tasks and optimize material usage, reducing costs [12]. Moreover, laborers with sufficient knowledge perform better on-site, leading to fewer costly mistakes during construction [5]. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic’s effects, construction firms seek double productivity to compensate for lost time, necessitating laborers to acquire the necessary knowledge to improve time performance [53].

The findings of the study also indicate that a ‘sense of belonging’ significantly impacts the time performance of construction projects, with a p-value of 0.006. Being a part of a team or group where one’s opinions matter fosters a sense of belonging, which in turn improves social skills and the ability to perform tasks effectively [54]. It is essential to have the support of colleagues and to feel like a valued member of a group, which ultimately boosts confidence and self-perception while performing tasks. Therefore, a sense of belonging among laborers promotes teamwork, cooperation, and overall efficiency in their work, resulting in improved time performance of the construction project.

4.3. Discussion

This study revealed that the COVID-19 pandemic had a significant impact on the social and psychological well-being states of construction workers, with distinct effects on managers and laborers. Although both groups had similar levels of anxiety and depression before the outbreak, they experienced increased symptoms after the pandemic. However, it was observed that laborers were more affected by these heightened symptoms compared to managers. One of the key reasons for the disproportionate impact on laborers compared to managers was the nature of their work and the restrictions imposed during the lockdown. Many managers were able to work remotely, allowing them to continue engaging in various construction-related activities, such as bid submissions, quality assurance practices, future project estimation, scheduling, online training, and seminars. These remote work opportunities provided a level of continuity in their professional lives, despite the pandemic’s challenges [32,39]. In contrast, laborers faced significant challenges during the lockdown. Their work primarily involves physical presence on construction sites, and with the implementation of total lockdown measures, many construction projects were halted, leading to idleness for laborers. Unlike managers, laborers could not engage in remote work activities, resulting in financial hardships due to a loss of income during the lockdown period. The pandemic also brought about increased health risk concerns for laborers as they directly interact with other workers on construction sites. This raised anxiety and fear about job security and personal safety. Laborers’ hourly wage structures meant they needed to be physically present on-site, both before and after the pandemic, and the fear of contracting the virus from colleagues created a sense of panic and concern about their health status and job stability. This fear of losing their source of income further exacerbates their stress and anxiety during these challenging times [4,47,55,56,57]. On the other hand, managers, being able to work remotely, were able to minimize their human contact, reducing their exposure to the virus and potential health risks.

Furthermore, this study discovered considerable disparities in social and psychological well-being variables, which led to a noticeable impact on project performance between managers and laborers after the pandemic. Both social and psychological variables influenced project performance in the managers’ decision-making processes. For example, ‘health risk concerns’ may influence their decisions regarding on-site safety measures and resource allocation to ensure the well-being of the workforce. ‘Income equality’ may play a role in determining fair compensation and benefits, which can impact worker motivation and satisfaction. ‘Sense of belonging’ and ‘job stability’ could affect teamwork and employee retention, influencing productivity and overall project success. Managers may also prioritize ‘stress management’ to ensure a positive work environment and minimize the negative impacts on decision-making and job performance. Additionally, ‘knowledge’ is essential for effective decision-making and problem-solving, enabling managers to adapt to changing circumstances and allocate resources efficiently. On the other hand, social variables primarily impacted project performance when laborers were involved in on-site tasks. For example, ‘financial stability’ can influence their motivation and job satisfaction, as it directly relates to their economic security and livelihood. ‘Income equality’ may be crucial for maintaining a sense of fairness and cohesion within the workforce, fostering a positive work environment. ‘Knowledge’ is vital for laborers to carry out their tasks efficiently and reduce material waste, which directly impacts project costs. ‘Sense of belonging’ is significant for fostering teamwork and cooperation among laborers, which can contribute to improved project outcomes. The analysis results highlight the disparity between managers’ and laborers’ perspectives on the factors influencing project performance. Managers take into account both social and psychological variables, while laborers focus primarily on social factors.

Based on these analysis results, management can prioritize addressing the factors that impact all parties involved and allocate resources for improvement. Firstly, management should provide regular training and workshops for the workforce to enhance their knowledge and keep them up to date with industry trends, standards, and quality requirements. Moreover, management should also address the anxieties and depression experienced by managers due to the non-physical nature of their work during the pandemic and the challenges associated with adjusting to construction activities post-COVID. Mental health professionals should be made available to managers to discuss their work-related and personal concerns, which can help alleviate their stress and promote their overall well-being. Additionally, management should offer time off work to facilitate stress management and prevent burnout, allowing workers to recharge and refocus on their job responsibilities. This approach can improve the well-being of workers and enable them to perform their jobs more effectively, with the assurance that time off is available when needed.

Secondly, management should prioritize improving social factors that impact managers’ performance, such as ‘income equality’, ‘sense of belonging’, and ‘knowledge’. To promote income equality, management should monitor it closely and reward individual performance and contributions to the company’s growth. Such incentives can motivate managers to work harder, creating healthy competition that ultimately benefits the company. Additionally, managers should be given opportunities to network and socialize with colleagues from other companies and sectors of the construction industry. This can foster a sense of belonging to a greater community, both professionally and personally, and ultimately boost morale, making managers feel valued and resulting in improved job satisfaction and performance. To keep managers up to date with industry standards, companies should provide opportunities for professional development, such as reduced-cost professional certifications and attendance at industry conferences. Collaboration with colleagues from other companies and the engineering industry can also help managers broaden their knowledge base and improve their skills.

Thirdly, management should focus on improving the psychological well-being of managers, which can significantly affect their performance on construction projects. This includes addressing their health risk concerns, job stability, stress management, and motivation. Companies can provide adequate health insurance schemes to help managers take care of their health and reduce the number of sick days taken, which can prolong project timelines. Paid time off should also be improved to allow managers to take time off without worrying about their pay or salary. Burnout is common among managers due to the intensity of projects and deadlines, so adequate provisions for managers to take time off work when necessary should be made available. Quarterly performance reviews should involve construction managers to show them areas of improvement and appreciation for a job well done, which can boost their confidence and job security. Management can also motivate managers by providing opportunities for professional development, such as training sessions and promotions, which can help them stay interested and committed to the project and the company. Additionally, company retreats and networking events can help managers feel appreciated and valued within the construction industry, further boosting their motivation and job satisfaction.

Finally, management should prioritize improving the financial stability, income equality, knowledge, and sense of belonging of their laborers. Financial stability is essential for laborers to save up during the off-season when work is scarce due to harsh weather conditions, and overtime should be encouraged for workers to ensure timely project delivery. Incentives such as overtime pay and bonuses should be provided to motivate laborers to work effectively and foster healthy competition among them. Income equality should be upheld across all levels, and regular wage reviews should be conducted to ensure workers’ finances are improving. Management should educate laborers on the construction process to improve the quality and timely completion of work on site. Networking and socializing among laborers should be encouraged to improve their general well-being and mental state, as they may be far from their families during peak season. This will improve their total work outlook, and they will feel a sense of belonging within the construction industry.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the impact of COVID-19 on the social and psychological well-being variables. The study findings indicate that both managers and laborers experienced significant increases in ‘anxiety and depression levels’ after the pandemic. Managers’ mean score for ‘anxiety and depression’ increased from 2.85 to 3.53, and laborers’ mean score increased from 2.97 to 4.28. Both groups experienced increased levels of anxiety and depression following the pandemic, but laborers were more severely affected. ‘Health risk concerns’ also significantly increased for laborers, with a mean score going from 3.83 to 4.38. This study also identified the changes in the impactful variables of the social and psychological well-being states between managers and laborers, which subsequently influenced project performance after the pandemic. The findings suggest that before the COVID-19 pandemic, managers perceived ‘knowledge’ as significantly impacting quality performance. On the other hand, laborers perceived that none of the social and psychological variables had an influence on their performance during that time. After the pandemic, managers identified variables such as ‘income equality’, ‘knowledge’, ‘sense of belonging’, ‘health risk concern’, ‘job stability’, and ‘stress management’ as crucial factors affecting project performance. Similarly, laborers emphasized ‘financial stability’, ‘income equality’, ‘knowledge’, and ‘sense of belonging’ as significant variables after experiencing the pandemic’s effects. Managers considered a broader range of variables in their decision-making processes, while laborers primarily focused on social variables affecting project performance. These disparities in perspectives highlight the need for construction companies to address the unique challenges faced by both managers and laborers. For managers, ensuring health and safety measures, fair compensation, team cohesion, and stress management are essential. On the other hand, laborers’ motivation, work environment, knowledge acquisition, and sense of belonging should be prioritized.

This study contributes to providing valuable insights for construction companies to optimize project performance and enhance the well-being of their workforce. By understanding and addressing the social and psychological variables identified in the study, construction companies can improve their management practices, leading to performance enhancement in the post-pandemic period. This study’s findings will enable companies to identify and address weaknesses in their workforce, ultimately fostering a positive work environment and maximizing the efforts of their employees.

However, this study has some limitations that should be acknowledged. Firstly, the dataset used for the analysis was limited in terms of its scope and size, which might affect the generalizability of the results. Further studies could aim to include a more diverse and extensive dataset, incorporating construction companies of different sizes, types, and locations to ensure a more comprehensive understanding of the social and psychological variables’ impact on project performance. Additionally, future research should consider the inclusion of data from individuals who tested positive for COVID-19. Understanding how the virus’s direct impact on workers’ health affects their social and psychological states and subsequently influences their performance is essential in comprehending the pandemic’s overall effects on the construction industry. Furthermore, exploring the reasons behind certain variables’ varying degrees of influence on project performance would provide valuable insights. By delving deeper into these variables, construction companies can develop targeted strategies to address specific challenges and optimize their workforce’s performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.E.O. and Y.J.; Methodology and Data curation, O.E.O. and Y.J.; Writing—original draft, O.E.O., J.A. and K.S.; Writing—review and editing, Y.J., J.A. and K.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (No. 2022R1F1A1076213).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of North Dakota State University (protocol code #IRB0004106 on 14 February 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Alsharef, A.; Banerjee, S.; Uddin, S.M.J.; Albert, A.; Jaselskis, E. Early impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the United States construction industry. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogunnusi, M.; Hamma-adama, M.; Salman, H.; Kouider, T. COVID-19 Pandemic: The Effects and Prospects in the Construction Industry. Int. J. Real Estate Stud. 2020, 2, 120–128. [Google Scholar]

- AGC Survey. Available online: https://www.enr.com/articles/48976-agc-survey-28-percent-of-members-report-halted-or-delayed-projects-due-to-covid-19 (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- Sood, S. Perspective Psychological Effects of the Coronavirus. RHiME 2020, 7, 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, J.; Ma, S.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Hu, J.; Wei, N.; Wu, J.; Du, H.; Chen, T.; Li, R. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e203976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johari, S.; Jha, K.N. Interrelationship among Belief, Intention, Attitude, Behavior, and Performance of Construction Workers. J. Manag. Eng. 2020, 36, 04020081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrosa, A.L.; Bitencourt, L.; Fróes, A.C.F.; Cazumbá, M.L.B.; Campos, R.G.B.; de Brito, S.B.C.S.; Simões e Silva, A.C. Emotional, Behavioral, and Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 566212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soekiman, A.; Pribadi, K.S.; Soemardi, B.W.; Wirahadikusumah, R.D. Factors relating to labor productivity affecting the project schedule performance in Indonesia. Procedia Eng. 2011, 14, 865–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirzadeh, P.; Lingard, H. Working from Home during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Health and Well-Being of Project-Based Construction Workers. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2021, 147, 04021048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Frutos, C.; Ortega-Moreno, M.; Dias, A.; Bernardes, J.M.; García-Iglesias, J.J.; Gómez-Salgado, J. Information on COVID-19 and psychological distress in a sample of non-health workers during the pandemic period. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataei, H.; Becker, D.; Hellenbrand, J.R.; Mehany, M.S.H.M.; Mitchell, T.E.; Ponte, D.M. COVID-19 Pandemic Impacts on Construction Projects; ASCE: Reston, VA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gamil, Y.; Alhagar, A. The Impact of Pandemic Crisis on the Survival of Construction Industry: A Case of COVID-19 Dr. Yaser Gamil Abdulsalam Alhagar. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2020, 2117, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Bennett, M. The mental health impact of COVID-19. Aust. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020, 37, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Memon, S.A.; Hadikusumo, B.H.W.; Sunindijo, R.Y. Using Social Interaction Theory to Promote Successful Relational Contracting between Clients and Contractors in Construction. J. Manag. Eng. 2015, 31, 04014095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunk, D.H.; Dibenedetto, M.K. Motivation and social cognitive theory. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 60, 101832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, S.; Pandey, A.K.; Mandal, S.N.; Bansal, S. A study of enabling factors affecting construction productivity: Indian scnerio. Int. J. Civ. Eng. Technol. 2017, 8, 741–758. [Google Scholar]

- Chih, Y.-Y.; Kiazad, K.; Zhou, L.; Capezio, A.; Li, M.; Restubog, S.L.D. Investigating Employee Turnover in the Construction Industry: A Psychological Contract Perspective. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2016, 142, 04016006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, M.; Kermanshachi, S.; Safapour, E. Engineering, Procurement, and Construction Cost and Schedule Performance Leading Indicators: State-of-the-Art Review. In Proceedings of the Construction Research Congress, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2–4 April 2018; pp. 378–388. [Google Scholar]

- Abas, M.; Khattak, S.B.; Hussain, I.; Maqsood, S.; Ahmad, I. Evaluation of Factors Affecting the Quality of Construction Projects. Tech. J. Univ. Eng. Technol. (UET) Taxila Pak. 2015, 20, 115–120. [Google Scholar]

- Benfante, A.; Di Tella, M.; Romeo, A.; Castelli, L. Traumatic Stress in Healthcare Workers during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Review of the Immediate Impact. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 569935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solís-Carcaño, R.G.; Corona-Suárez, G.A.; García-Ibarra, A.J. The Use of Project Time Management Processes and the Schedule Performance of Construction Projects in Mexico. J. Constr. Eng. 2015, 2015, 868479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, L.; Dent, S. Risk management for planning and decision making of pipeline projects. In Pipelines 2007: Advances and Experiences with Trenchless Pipeline Projects, Proceedings of the ASCE International Conference on Pipeline Engineering and Construction, Boston, MA, USA, 8–11 July 2007; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2007; Volume 60. [Google Scholar]

- Cairó, I.; Cajner, T. Human Capital and Unemployment Dynamics: Why More Educated Workers Enjoy Greater Employment Stability. Econ. J. 2018, 128, 652–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Xuan, P.; Li, S.; Huang, P. Schedule Risk Analysis for TBM Tunneling Based on Adaptive CYCLONE Simulation in a Geologic Uncertainty–Aware Context. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2015, 29, 04014103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, D.; Jin, Y.; He, M.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, X.; Song, S.; Zhang, L.; Xiang, X.; et al. Risk factors for depression and anxiety in healthcare workers deployed during the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2021, 56, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assaad, R.; El-adaway, I.H. Impact of Dynamic Workforce and Workplace Variables on the Productivity of the Construction Industry: New Gross Construction Productivity Indicator. J. Manag. Eng. 2021, 37, 04020092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkas, K.J.; Romaniuk, J.R. Social Work, Ethics and Vulnerable Groups in the Time of Coronavirus and COVID-19. Soc. Regist. 2020, 4, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jana, D.; Sinha, A.; Gupta, A. Determinants of Financial Literacy and Use of Financial Services: An Empirical Study amongst the Unorganized Sector Workers in Indian Scenario. Iran. J. Manag. Stud. 2019, 12, 657–675. [Google Scholar]

- Elbarkouky, M.M.G.; Fayek, A.R.; Siraj, N.B.; Sadeghi, N. Fuzzy Arithmetic Risk Analysis Approach to Determine Construction Project Contingency. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2016, 142, 04016070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashiguchi, N.; Cao, J.; Lim, Y.; Kubota, Y.; Kitahara, S.; Ishida, S.; Kodama, K. The effects of psychological factors on perceptions of productivity in construction sites in Japan by worker age. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, M.; Hasan, A.; Jain, A.K.; Jha, K.N. Site Amenities and Workers’ Welfare Factors Affecting Workforce Productivity in Indian Construction Projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2018, 144, 04018101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salari, N.; Khazaie, H.; Hosseinian-Far, A.; Khaledi-Paveh, B.; Kazeminia, M.; Mohammadi, M.; Shohaimi, S.; Daneshkhah, A.; Eskandari, S. The prevalence of stress, anxiety and depression within front-line healthcare workers caring for COVID-19 patients: A systematic review and meta-regression. Hum. Resour. Health 2020, 18, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lund, E.M.; Forber-Pratt, A.J.; Wilson, C.; Mona, L.R. The COVID-19 pandemic, stress, and trauma in the disability community: A call to action. Rehabil. Psychol. 2020, 65, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, P.X.W.; Chen, Y.; Chan, T.-Y. Understanding and Improving Your Risk Management Capability: Assessment Model for Construction Organizations. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2010, 136, 854–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogl, B.; Abdel-Wahab, M. Measuring the Construction Industry’s Productivity Performance: Critique of International Productivity Comparisons at Industry Level. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2015, 141, 04014085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, N.; Zhong, R.; Wu, C.; Wang, X.; Wang, S. Assessment of Stakeholder-Related Risks in Construction Projects: Integrated Analyses of Risk Attributes and Stakeholder Influences. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2017, 143, 04017030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sritharan, J.; Jegathesan, T.; Vimaleswaran, D.; Sritharan, A. Mental Health Concerns of Frontline Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Scoping Review. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2020, 12, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipolotti, L.; Chan, E.; Murphy, P.; van Harskamp, N.; Foley, J.A. Factors contributing to the distress, concerns, and needs of UK Neuroscience health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 2021, 94, 536–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.T.L.; Le Nguyen, T.B.; Pham, A.G.; Duong, K.N.C.; Gloria, M.A.J.; Van Vo, T.; Vo, B.V.; Phung, T.L. Psychological Stress Risk Factors, Concerns and Mental Health Support Among Health Care Workers in Vietnam during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 628341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.-H.; Mahadevan, S. Construction Project Risk Assessment Using Existing Database and Project-Specific Information. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2008, 134, 894–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeynalian, M.; Trigunarsyah, B.; Ronagh, H.R. Modification of Advanced Programmatic Risk Analysis and Management Model for the Whole Project Life Cycle’s Risks. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2013, 139, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, I.A.; Memon, A.H.; Nagapan, S.; Latif, Q.B.A.I.; Azis, A.A.A. Time and cost performance of construction projects in southern and central regions of peninsular Malaysia. In Proceedings of the CHUSER 2012—2012 IEEE Colloquium on Humanities, Science and Engineering Research, Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia, 3–4 December 2012; pp. 52–57. [Google Scholar]

- Issn, B.P. Cost Performance for Building Construction Projects in Klang Valley. J. Build. Perform. 2010, 1, 110–118. [Google Scholar]

- Gurmu, A.T.; Aibinu, A.A. Construction Equipment Management Practices for Improving Labor Productivity in Multistory Building Construction Projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2017, 143, 04017081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.H.W.; Yiu, T.W.; González, V.A. Predicting safety behavior in the construction industry: Development and test of an integrative model. Saf. Sci. 2016, 84, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamidimukkala, A.; Kermanshachi, S. Impact of COVID-19 on field and office workforce in construction industry. Proj. Leadersh. Soc. 2021, 2, 100018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garabiles, M.R.; Lao, C.K.; Xiong, Y.; Hall, B.J. Exploring comorbidity between anxiety and depression among migrant Filipino domestic workers: A network approach. J. Affect Disord. 2019, 250, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bsisu, K.A.D. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on Jordanian civil engineers and construction industry. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. 2020, 13, 828–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.C.; Shih, T.P.; Ko, W.C.; Tang, H.J.; Hsueh, P.R. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19): The epidemic and the challenges. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 55, 105924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, L.Q.; Xu, M.L.; Sun, J.; Wang, Q.X.; Ge, D.D.; Jiang, M.M.; Du, W.; Li, Q. Anxiety and depression in frontline health care workers during the outbreak of COVID-19. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2021, 67, 656–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelalim, A.M.; Elbeltagi, E.; Mekky, A.A. Factors affecting productivity and improvement in building construction sites. Int. J. Product. Qual. Manag. 2019, 27, 464–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dynan, K.E.; Ravina, E. Increasing Income Inequality, External Habits, and Self-Reported Happiness. Am. Econ. Rev. 2007, 97, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluwananumi, D.; Abdullahi, A.; Cynthia, O.C. Impacts of sudden lifestyle changes due to COVID-19 on mental health: African perspectives. J. Public Health Dis. 2020, 3, 22–23. [Google Scholar]

- Saiz, J.; González-Sanguino, C.; Ausín, B.; Castellanos, M.Á.; Abad, A.; Salazar, M.; Muñoz, M. The Role of the Sense of Belonging during the Alarm Situation and Return to the New Normality of the 2020 Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19) in Spain. Psychol. Stud. 2021, 66, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayodele, O.A.; Chang-Richards, A.; González, V. Factors Affecting Workforce Turnover in the Construction Sector: A Systematic Review. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, 03119010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godinic, D.; Obrenovic, B.; Khudaykulov, A. Effects of Economic Uncertainty on Mental Health in the COVID-19 Pandemic Context: Social Identity Disturbance, Job Uncertainty and Psychological Well-Being Model. Int. J. Innov. Econ. Dev. 2020, 6, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oni, O.Z.; Olanrewaju, A.; Khor, S.C. A comparative analysis of construction workers’ mental health before and during COVID-19 pandemic in Nigeria. Front. Eng. Built Environ. 2023, 3, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).