Abstract

There have been significant research studies on informal settlements within various disciplines including sociology, economy, politics, governance, and urbanism. However, little is known about the complexity and dynamism of informal settlements. The purpose of this study is to develop a framework for understanding the multiplicity of factors influencing the formation and transformation of informal settlements. It examines and validates various intricacies characterising informal settlements in three ways. First, informal settlement characteristics and their relationships are explored. Second, growth and transformation variables are examined. Third, qualities of the informal urban form and those that relate to sustainability are juxtaposed. Utilising two case studies from Greater Cairo, a qualitative approach is adopted including a critical analysis of the literature, interviews with experts and academics, and field observations. Through a comprehensive investigation of informal settlements, two deductions were made: First, the critical physical, social, and economic characteristics that influence their growth were identified. Second, the unique correlations between these characteristics were established and verified by the two case studies. The correlations assist in establishing the logic and dynamics of the informal settlements that can then be applied to develop intervention strategies. In addition, the inferred informal urban form can be considered as a sustainable urban form tailored for further analyses of informal settlements of cities of the global south.

1. Introduction

1.1. Contextual Background

Informal settlements can be seen as outcomes of industrialisation and globalisation processes. The rapid urbanisation, lack of affordable housing, rural-urban migration, and increase in population have led to the development of informal settlements. They emerged as an alternative to formal housing for those who migrated to the urban areas looking for job opportunities, better social and public facilities, and services [1]. Rapid urbanisation and lack of governmental support to create low-cost and affordable housing led to the rise in informal settlements. Rapid urbanisation created a dearth of affordable houses. In some contexts, where land was available for development, the building regulations and standards hampered the construction. In cities in Egypt, Kenya, and Iran, building regulations and standards were impractical to allow low- and middle-income populations to construct their own houses. For example, plot sizes were relatively big, rendering them too expensive to own and build on [2]. In addition, low income and poverty provoked people to create low-cost houses for shelter since the other options were only affordable to middle- or high-income groups. In addition to the shortage of social housing, the lack of governmental support to the low-income group to procure land for affordable housing, inadequate access to serviceable lands and housing units, and challenging requirements of the mortgage programmes discouraged the creation of low-cost affordable housing. Moreover, the real estate market assigns a high cost of housing as compared to the average per capita income, which makes the informal market more affordable [3]. Furthermore, the displacement due to natural disasters and conflict in some cases has led to the transformation of temporary housing for the affected into informal settlements [4].

In 2018, the United Nations estimated that around 55% of the world’s population lived in urban areas and that this proportion would reach 68% by 2030 [5]. This would be in conjunction with the rapid increase in urban populations and a lack of supply of affordable housing for low- and middle-income populations in countries in the Global South. As such, they predicted that people would continue to encroach on unclaimed or unused lands and build homes for themselves. This resulted in the creation and expansion of informal settlements and slums, which have now become a global urban phenomenon [4]. This phenomenon is accompanied by its own set of problems and challenges. Table 1 summarises the problems that these informal settlements and their residents must contend with [1,6,7,8,9,10,11].

Table 1.

Informal settlements: general challenges.

The increase in the number of informal settlements and slums, and consequently the informal residents, has raised concerns with regards to the quality of life and has become the focus of many studies across different disciplines. As a result, the notion of informality is currently being researched and has produced in-depth studies involving different discourses. Informality is often perceived as a marginal sector where not only the urban poor live to survive but also contribute to modern economies by engaging with the formal sector [12]. Legally, Hernando de Soto [13] interpreted the informal economy as a creative solution for allowing people to integrate with the formal economy.

1.2. Research Motivation and Purpose

Various studies on the built environment have investigated the history and causes of the emergence of informal settlements and slums in cities of the Global South [2,3,14,15,16]. Few studies focus on exploring the factors and processes that influence the growth of informal settlements and slums [17,18,19], while others are investigating the physical, social, economic, and environmental characteristics of informal settlements [7,20,21,22]. The study of different typologies of informal settlements with an intent to identify different frameworks to classify these settlements reflects a different approach. The frameworks could be context specific, which consider the current state of formal/informal conditions of housing [23], the physical characteristics of informal settlements [24], the process of informal growth [17], or a spectrum of characteristics on informality [1].

Contributing to the discourse on informality while uncovering key characteristics of selected informal settlements, the purpose of this study is to develop a characterisation of informal settlements framework (CISF) which recognises the multiplicity of factors influencing their formation and transformation. It examines and validates various intricacies characterising informal settlements in three ways. First, informal settlement characteristics and their relationships are explored. Second, growth and transformation variables are examined. Third, qualities of the informal urban form and those that relate to sustainability are juxtaposed.

Despite the wealth of literature available in different disciplines, there is a gap in knowledge in understanding the complexities of informality at micro spatial scales [25,26] and its associated urban form and architecture [27]. The armature of the informal settlements is contextual, i.e., the structure of every settlement around the globe differs from country to city to settlement. Therefore, creating, upgrading, and integrating settlements within formal urban planning schemes is a challenging task but a necessary one. The CISF proposed and validated in this study would enable effective planning for potential interventions to upgrade or improve existing informal settlements.

2. Theoretical Underpinnings—Building a Framework

2.1. Informality

The concept of informality emerged in the 1970s when the International Labour Organization developed theories on an informal economy and the process of formalization [28]. Later, Hernando de Soto described informality as a ‘survival strategy’ that emerged from excessive state regulations [13]. AlSayyad argued that informality represented an organic logic that appeared due to liberalization [12], while Roy described it as a form of expression that connected different types of housing production [29]. Simultaneously, different schools of thought studied informality, deriving two models of informal–formal relationships: the informal–formal dichotomous model (developed by the dualist and legalist schools) and the informal–formal dialogic model (developed by the structuralist and relational schools) [30]. Many schools explored the informal–formal relations from an economic point of view, except for the relational school, which acknowledged the complexity of informality and that a multidisciplinary approach was most suitable.

Moreover, Bayat identifies that the shift from socialist to liberal economies paved the way for the disappearance of social programmes and the fall of the formal economy. It thus prompted people to act in informal ways. As a result, the social science community developed five models of informality: passive poor, surviving poor, political poor, resisting poor, and, later, quiet encroachment [31].

This research follows the informal–formal dialogic model of the relational approach and the quiet encroachment model for conducting further investigations on informality in the Global South. The relational approach acknowledges that informality is built on different relations between social, economic, spatial, and cultural aspects. On the contrary, the quiet encroachment model adopts the view that people try to improve their quality of life because globalisation and economic liberalisation have made them ‘the urban poor’; hence they challenge modern urban governance that serves urban elites.

2.2. Informal Built Environment

Kellett and Napier developed a conceptual framework based on existing frameworks for vernacular environments. The testing of their framework identified relationships between the different elements (social, physical, economic, and cultural) and between the informal and formal processes [32]. Several other frameworks such as the Informal Settlements Urban Form and Architecture Framework are developed based on this framework [27].

Another study on informality measures the four elements of vulnerability using the following indicators: physical risk related to the site, personal risk, livelihood, ability to withstand shocks, recognition of intangible assets, the social value of tangible and communal assets, and the impact on informal spatial relationships [33]. These indicators have shaped this empirical investigation framework, allowing for a comprehensive understanding of the informal built environment and the different relationships that create these unique environs. This research subsequently developed a set of physical, social, and economic characteristics to systematically investigate the informal built environment (Table 2). Nevertheless, it is crucial to explore each aspect and the reciprocal effects on each other. Therefore, the study developed three sets of characteristics used to study the two case studies.

Table 2.

The list of characteristics contributing to the conceptualisation of the CISF Tier 1.

Two in-depth studies explored and developed an understanding of the main factors behind the emergence and continued growth of informal settlements. Two studies conducted by Roy et al. and McCartney and Krishnamurthy identified seven and five factors, respectively [18,19]. Based on these studies, this research deduced two sets of factors—non-spatial and spatial factors (Table 3).

Table 3.

Factors of transformation and the associated characteristics contributing to the establishment of CISF Tier 2.

2.3. Sustainable Urban Form

To develop the Characterisation of Informal Settlements Framework (CISF), it was necessary to understand several urban development concepts and compare their structure to the informal settlements. One concept that relates closely to informal settlements is that of sustainable urban form. The current discourse on sustainable urban development has many approaches, of which the four most common are New Urbanism, Neo-Traditional Developments, Smart Growth, and the Compact City.

New Urbanism emerged in the 1980s, aiming to revitalise deteriorated inner-city areas. The Charter of New Urbanism suggests ten principles to guide planning to create compact, diverse, mixed-use, and pedestrian- and transit-oriented designs and promote a sense of community. Neo-Traditional Developments (NTD) emerged from New Urbanism’s visions of the ideal neighbourhood. It offers a direct answer to mono-zone, low-density, and car-dependent suburbs. Smart Growth emerged to balance cities’ growth by meeting social, economic, and environmental needs and emphasises reviving and redeveloping existing built-up areas. It focuses on two aspects: land-use patterns and housing. It promotes the sustainable development of cities with principles similar to New Urbanism while limiting the physical expansion of cities.

These concepts steer towards the Compact City and mixed-use development concepts. These two design concepts are interrelated; to achieve one, it is necessary to implement the other. The compact urban form stipulates mixed-use developments within its principles because mixed-use reduces travel distances, increases the efficiency and optimum use of land, encourages social interaction, and increases economic viability.

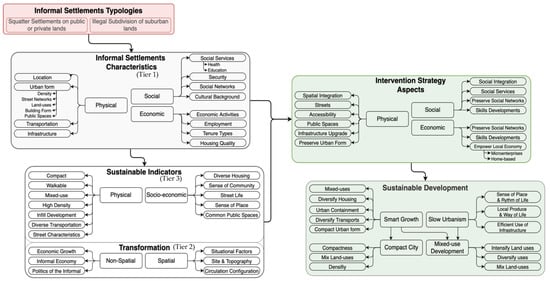

In line with the research purpose, a relational approach to informality was found most relevant, which enabled identifying various pathways to study the physical, social, cultural, and economic characteristics along with the factors of transformation. The review also assisted in cross-examining the characteristics of the informal settlements with sustainable urban forms. Thus, this approach helped in developing the proposed framework for investigation (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The three-tiered investigation framework.

3. Methodology

This investigation followed a qualitative research methodology for field studies and data collection. It involved collecting data by means of synchronous interviews with academicians and experts with knowledge of intervention strategies with regards to informality. The preliminary data gathered from the literature review developed an understanding of informal settlements and identified the theoretical premise. This study uses multiple sources to acquire data to understand different perspectives [34]. Therefore, two validation strategies are employed to ensure that the data acquired is accurate, consistent, and meaningful. First, a triangulation strategy synthesises multiple data sources to derive themes or categories in the study. Second, a thick and rich description is a procedure for establishing credibility wherein the researcher describes the study’s setting, participants, and themes in detail [34].

3.1. Interviews as a Prelude for Investigation

Ten online interviews with academics and experts in Egypt were conducted. This was followed by data transcribing, analysing, and storing on a personal online space allocated to researchers as part of a required data management plan. The interviews were semi-structured and included open-ended questions, which initiated a discussion on informality. The questions were framed to extract different characteristics of informal settlements and transformation factors that influence the growth of the settlements. The interviewees were expert academics and professionals with architecture, urban design, and urban planning backgrounds whose expertise included significant research and consultancy on informal settlements in the context of Egypt. The interviews focused on two informal settlements, Ezbet El Haggana and Ard El Lewa, as potential case studies to be verified by the experts interviewed. The open-ended questions involved engagement in a discussion on four key aspects that included categorised characteristics and qualities of the overall physical, social, and economic environment in informal settlements; experts’ views on how existing qualities relate to various sustainable urban development indicators; their opinions on the various determinants of transformation; and their perception, conjecture, and anticipation of possible future intervention strategies.

The information resulting from the interviews was interpreted to identify the following characteristics of informal settlements:

3.1.1. Physical Aspects

- Most of the settlements have poor infrastructure networks. Although, in some places, the utility networks exist by a lack of maintenance and quality.

- Many settlements have electricity and water supply; however, low water pressure hinders water supply to the upper floors.

- Utility networks are overloaded as they were not designed for high population density, unlike formal areas such as Nasr City.

- Informal areas lack services and amenities. To compensate for the lack of such services, the residents start small businesses. For instance, a few businesses for recycling iron were set up in Ezbet El Haggana.

3.1.2. Economic Aspects (Locational Advantages)

- Informal settlements emerged in strategic locations that would allow seamless connectivity to the jobs and services in the formal city.

- The proximity of formal and informal settlements creates job opportunities for the working class. The informal residents are offered jobs as domestic help, shop workers, salespeople, and so on. On the other hand, the informal residents use the educational and health facilities in the formal city. Such dependencies strengthen the bond between formal and informal areas.

- The proximity to the city also opens up several opportunities for women as caregivers, babysitters, nurses in hospitals and health facilities, and cleaning service providers.

3.1.3. Social Aspects

- Informal settlements are known for their close-knitted communities. Strengthening social ties and building new networks are considered to be an essential part of life.

- The acquaintances amongst one another assist in compensating for the lack of services.

- The compact structure of the informal settlements increases social interaction and strengthens social ties.

- Initially, a working member of the family moves to the informal settlements and gradually invites one’s family and the extended family and they live close to one another. This is the typical growth pattern. These residents belong to the same family; hence, they have the same traditions and beliefs. Gradually, the people belonging to the same community and sharing the same traditions and beliefs start living nearby and governing the place.

- The streets are the only open spaces, and they are the expressions of the culture, traditions, and beliefs.

- Using the streets for community gatherings and celebrations is typical in informal settlements. In workplaces, however, streets act as spaces for spill-over activities or are extended workshops and shops.

- Informal markets are being upgraded and are becoming more permanent. Old buildings are converted into shopping malls.

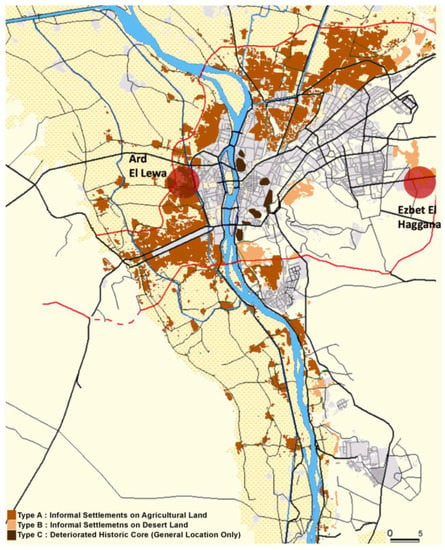

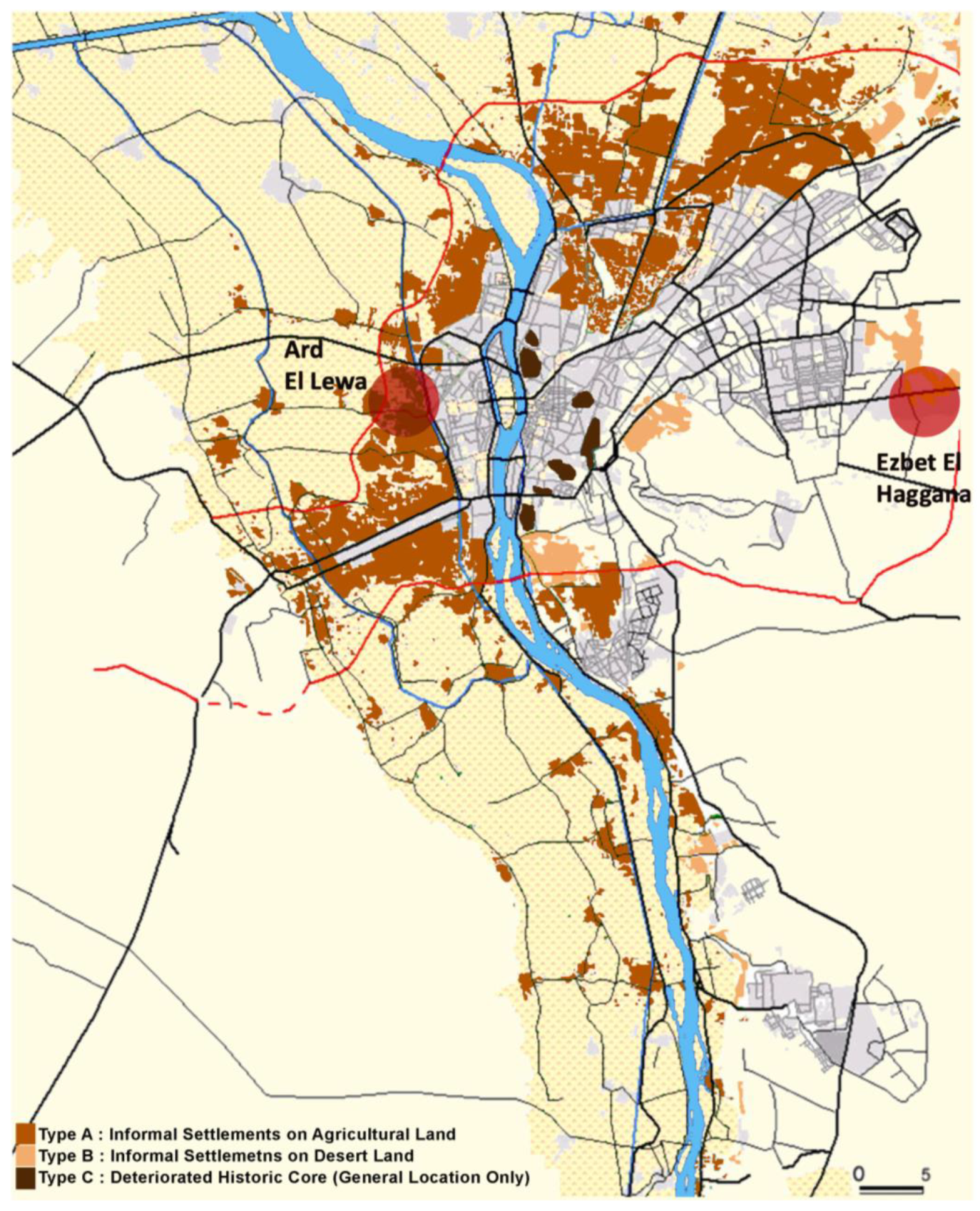

3.2. Research Context: Greater Cairo

In Greater Cairo, with a population of over 20 million (around 20% of the country’s total population) [5], 65% of its inhabitants live in informal settlements [33]. The development of informal settlements started in the 1950s. They are found in different locations in and around big cities such as Cairo (Figure 2), Giza, and Alexandria. Based on conditions and location, there are four manifestations of informal settlements in Egypt: Illegal Suburban Land Subdivision, Squatter Settlements, Deterioration or Change of Use of Formal Housing and Cemeteries, or City of the Dead.

The development of the underground metro network, ring road, and new towns guided Greater Cairo’s informal and formal urban expansion, which later fragmented the city’s urban fabric. While informal settlements currently house 65% of the population, more exclusive, wealthy gated communities started to develop in the 1990s among private developers [35,36], indicating the wide gap between living conditions. Informal settlers in Cairo cannot be generalised as poor, as evidenced by conditions in their living areas. Previous studies have shown that informal households’ average income is close to Greater Cairo’s average [37]. The formal expansion of the city is moving towards gated communities, which only serve the high-income group, while informal settlements serve low- and middle-income groups. They prefer informal settlements because they are self-sufficient, as most contain shops, workshops, and markets that fulfil their needs. Other appealing characteristics include their work-home proximity and walkability due to their compact form, where walking is the preferred mode of transportation. Inhabitants also value their social networks and participation, where streets act as an extension of homes, and cultivate a sense of safety [38]. Formal urban developments are far fewer and thus have not responded to people’s needs as the country needs over 300,000 low-income housing annually [39].

Figure 2.

Map of Greater Cairo showing the distribution of the three main typologies [40]. It illustrates squatter settlements developed near the city centre and the eastern periphery of Cairo, while illegal subdivision on agricultural land is concentrated on the western and northern periphery.

Figure 2.

Map of Greater Cairo showing the distribution of the three main typologies [40]. It illustrates squatter settlements developed near the city centre and the eastern periphery of Cairo, while illegal subdivision on agricultural land is concentrated on the western and northern periphery.

3.2.1. Case Study Selection

There are two main typologies of informal settlements in Greater Cairo, the illegal subdivision of agricultural lands and squatter settlements, which account for almost all informal settlements. A number of criteria were employed for the selection. The first key criterion is representation, i.e., a selection of cases that represent the main typologies. The first case selected for validation, Ezbet El Haggana, is an informal settlement on privately owned agricultural land, and the second case, Ard El Lewa, is a squatter settlement on public lands that have been legalised and integrated into the urban fabric of the city. Therefore, the two case studies represent the two different typologies that differ in location, profile, and structure as the settlements on agricultural lands are mainly based on the western and northern periphery of the city, while the squatter settlements are on the eastern periphery. The second key criterion is that the settlement should be considered well-established with no significant interventions to alter its urban form; this means studying the original built environment built by the community over time; the two cases go back to the mid to late 1970s with minimal intervention. Another reason for choosing a well-established area is that it will have undergone all early informal development phases and can account for the size of a district. Therefore, they can be cross-examined with a list of indicators developed from the sustainable urban development and informality perspectives. Moreover, exploring the factors of transformation reflects a more realistic situation that can help develop the growth management component of the intervention strategy than studying a newly found informal settlement that does not involve the relevant components.

3.2.2. Ezbet El Haggana

Ezbet El Haggana is one of many informal settlements in and around Greater Cairo (Figure 3). It was built on state-owned land in the eastern desert of Cairo near Nasr City (established by President Gamal Abdul Nasser in the 1960s) [41]. Its name, “Ezbet El Haggana”, means the village of camel corps; the name is related to the first settlers and their families who were allowed by the military to settle there [42,43]. There is a debate on when the settlements first started to appear. In Bremer and Bhuiyan’s study [43], some interviewees stated that the first dwellings appeared in the 1880s, while others estimated that the first settlers appeared in the 1930s when camel corps officers let their soldiers build houses for their families near the camp [44].

Figure 3.

There is a wide spectrum of building quality in Ezbet El Haggana. From poor houses such as Suessi (bottom) to high-rise apartment buildings (top) (Photos by A. Bakhaty).

3.2.3. Ard El Lewa

Ard El Lewa is an exemplary settlement of illegally subdivided agricultural land located on the western periphery of Greater Cairo [45] (Figure 4). The urbanisation of Ard El Lewa started in the 1970s, as most of its population are rural migrants [46]. The area has similar characteristics to other informal settlements of Greater Cairo, such as high density, inadequate infrastructure, and a lack of public services [47] (Table 4).

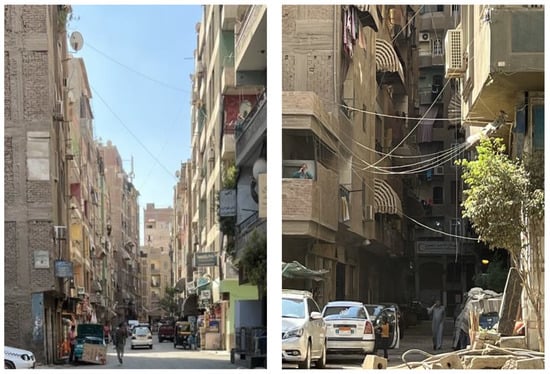

Figure 4.

The left image shows one of the secondary streets in Ard El Lewa, with the ground floor designated for commercial uses, while the right one shows one of the residential streets that are very narrow with limited economic activities (photos by A. Bakhaty).

Table 4.

Characteristics of the Ezbet El Haggana and Ard El Lewa informal settlements.

4. Discussion: Characterisation of Informal Settlements (CISF)—The Case of Ezbet El Haggana and Ard El Lewa

4.1. Significance of the Results

The three-tiered framework defines the physical, social, and economic characteristics (Table 2) and the different relationships between them. It identifies the factors that influence the transformation and growth of the settlement (Table 3) while cross-examining the urban form of the settlement with different concepts of sustainable urban forms (Table 5). These are demonstrated using a series of figures.

Table 5.

The indicators of the four models of sustainable urban development enabling the identification of relevant indicators for the CISF Tier 3.

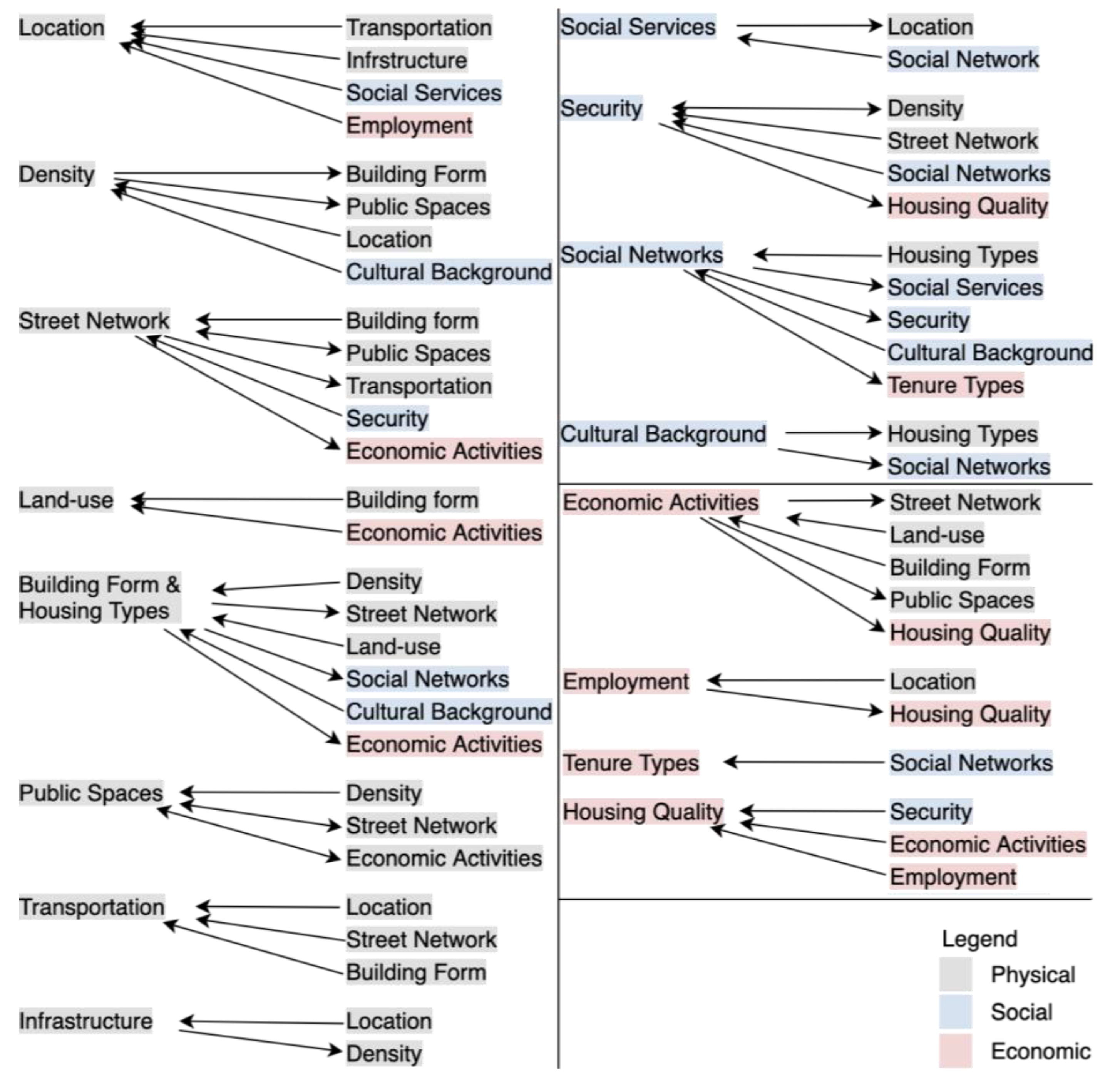

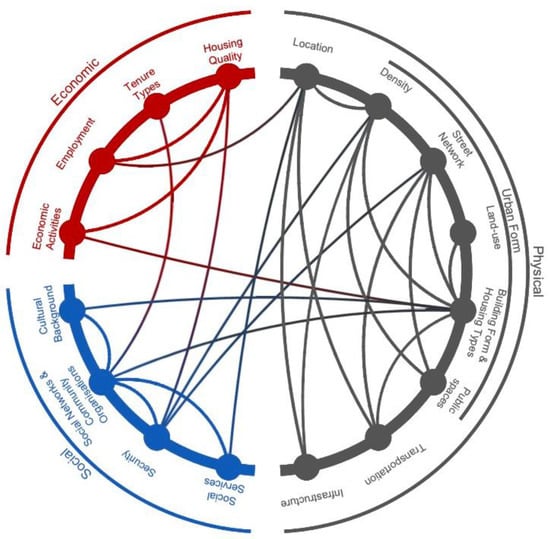

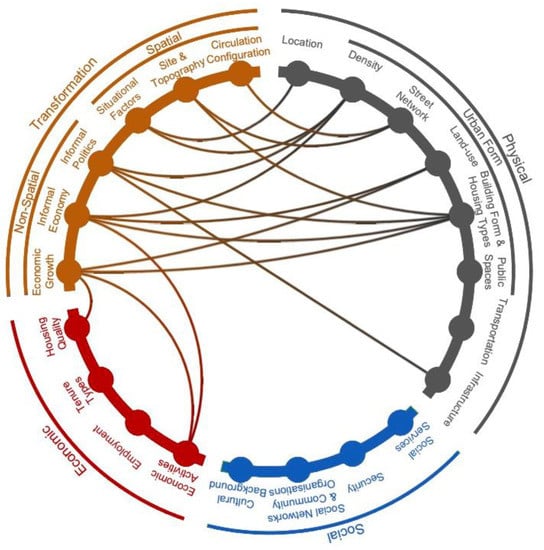

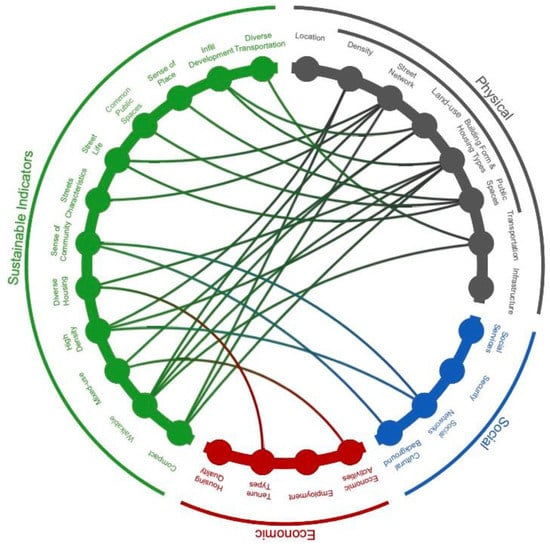

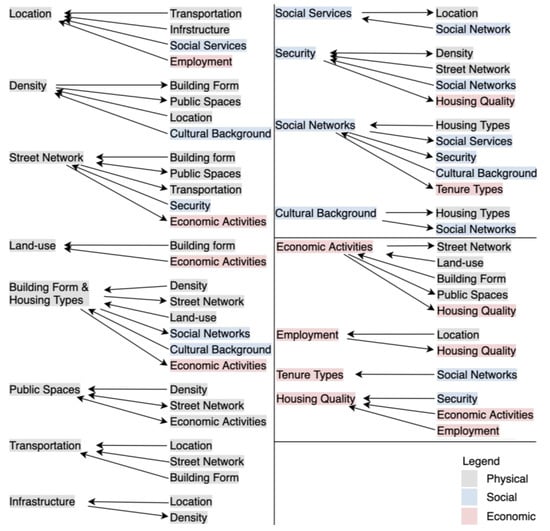

The first tier shows the relationships between the physical, social, and economic characteristics (Figure 5). It reveals the connections and effects of different characteristics on others to understand the settlements’ dynamics. The second tier inspects the spatial and non-spatial transformation factors and how they are investigated through the different characteristics of the settlement (Figure 6). Finally, the third tier cross-examines the current built environment with sustainable indicators to assess the sustainability of the urban form (Figure 7).

Figure 5.

Tier 1: physical, social, and economic characteristics.

Figure 6.

Tier 2: factors of transformation of informal settlements.

Figure 7.

Tier 3: sustainability indicators.

4.1.1. Tier 1: Investigating the Characteristics and Their Relations

The first tier investigates the physical, social, and economic characteristics and their correlations. These relationships are crucial to understanding how the informal built environment evolved to address the community’s needs and way of life. The physical characteristics include location, urban form, transportation, and infrastructure. The social characteristics consist of social services, security, social networks and community organisations, and cultural background. While the economic characteristics involve economic activities, employment, tenure types, and housing quality.

Physical Characteristics

Location: The location of the informal settlement is essential to maintain the quality of life and earn livelihoods. Ezbet El Haggana and Ard El Lewa are located in close proximity to formal areas and important transportation corridors. This connectivity offers access to services and amenities. Their strategic location increases access to social services and offers job opportunities that are unavailable in the settlement.

Density: High population density characterises Ezbet El Haggana and Ard El Lewa. The increased density was due to the proximity to a good location, affordability, and opportunities to build social ties. The process of in-migration has led to an increase in the population density in these settlements. As a result, building typologies that accommodate high density have evolved. Thus, most buildings are connected, and vertical expansion is a frequent process. Furthermore, the high-density compact settlements created a dearth of public spaces as the available land was consumed for housing. The intention was to accommodate more houses in a limited space. This resulted in reduced dwelling sizes and smaller habitable spaces.

Street Network: The mixed-use, compact building form compromised the street width and hence the network, as seen in both case studies. The compactness and high density of the built environment created narrow streets. The building height overshadowed the street width, affecting the enclosure ratio. The limited availability of public spaces resulted in the multipurpose use of the streets. The spill-over activities of the street vendors, workshops, and general shops are often seen. Streets also are turned into community spaces, often as playgrounds for children to play and for neighbours to socialise and enhance social ties. These different uses allow for constant visual surveillance, which cultivates a sense of safety and security. The narrow streets discourage vehicular access and promote walkability; however, smaller vehicles such as tuk-tuks are often allowed passage.

Land-use: The typology for commercial buildings is often the same as formal settlements with the ground floor being used for commercial purposes and the upper floors for residential use. The size of the commercial spaces varies and caters to all income groups, where one can rent it or own it for business purposes. The shops generally consist of all the items of daily needs and are within walkable distances.

Building Form and Housing Types: The advantage of high-density compact urban forms in informal settlements is the increased social interaction. It assists in creating social ties and developing a sense of belonging and safety. The building typologies often reflect the culture and the native architecture and strategically consider the future requirements of the space. Often extra spaces are rented to the extended family and become an additional source of income.

Public Spaces: The public spaces, as the two case studies suggest, include mainly streets and rooftops. Streets are used for movement and social and economic activities. The use of the streets as public spaces for community purposes is governed by local laws wherever possible to ensure control and discourage misuse.

Transportation: The proximity to the major transportation corridors is the unique benefit of the two informal settlements. The increased connectivity to the regional areas as well as nearby formal areas encourages residents to take on diverse job opportunities. However, within the informal settlements walking is the best mode of transport.

Infrastructure: Both informal settlements are close to the formal areas; hence, they benefit from the extended infrastructure and utility services. Moreover, access to basic infrastructure facilities such as water supply, sanitation, and electricity increases the liveability ratio and acts as a catalyst to attract diverse socio-economic groups.

Social Characteristics

Social Services: Both informal settlements lack social services, so residents depend on the formal areas for these services. The connectivity to the formal areas via the city’s transportation network facilitates the use of service and amenities in other parts of the city. Other important aspects of providing services in the areas are the Community-Based Organisations (CBOs), Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs), and social ties. Although residents depend on each other for help, attempts have been made to build social ties with the local NGOs and CBOs that also compensate for the lack of services. This is achieved by conducting conversations with the communities to understand their needs. Moreover, the residents of informal areas provide social services such as cleaning services and caregiving to the formal areas’ residents, thus maintaining the informal–formal social reciprocity.

Security: Narrow streets provide visual surveillance, and the close-knit housing structure encourages acquaintances and social bonding, thus instilling a sense of security. Additionally, the large scale of the settlements and the longer duration of their residency has availed land ownership rights and ensured tenure security. Furthermore, both settlements are too big to eradicate and their contribution to the local and state economy cannot be neglected. These factors result in permanent houses of good structural quality.

Social Networks and Community Organisation: The close-knit fabric and sense of belonging to the same culture and a certain community that shares the same values, traditions, and beliefs are the two assets that informal settlements build on. These assets not only create social cohesion but also cultivate a sense of unity. As they grow their social network increases and this gives rise to community organizations to provide social services, maintain law and order, and help the needful.

Cultural Background: The migrants belong to the same cultural background, locations, and communities. Therefore, the prior social networks are strengthened here as a result of relocation. The culture is reflected in their lifestyle, their homes, their community spaces, and their social behaviours.

Economic Characteristics

Economic Activities: The economic activities within the settlements flourish to cater to the diverse needs of the residents. A hierarchy in the scale of shops, businesses, and commercial spaces based on the socio-economic group is also evident. At the same time, local shops that are an extension of the houses are also seen. The income generated helps the residents in carrying out necessary maintenance work and upgrading their homes.

Employment: The employment opportunities are dependent on the skills of the residents as well as the proximity to the formal areas and connectivity via transportation networks. It was found that the dependency ratio of the informal to the formal city was high in Ezbet El Haggana and Nasr city and in Ard El Lewa and Mohandessin especially when compared to other areas.

Tenure Types: From the two case studies it was evident that the informal residents abide by the law and order that assist them in living peacefully with others without a conflict of ownership. The two case studies identify different tenure types, such as room rental agreements and building ownership rights. These are governed by the people and informal contracts that protect people’s rights. The sense of community and familiarity make these contracts binding and trustworthy.

Housing Quality: The quality of housing depends on the income generated from the businesses within or outside of the informal settlements, employments in the formal areas, and sense of security of non-eviction. People engaged in the informal economy earn enough to later upgrade their houses. Second, skilled worker jobs in formal areas generate income to acquire better housing. Third, the sense of security and assurance that the government will not evict them due to the huge scale of the settlements and being categorised as unplanned areas helps in settling and induces a need for permanent housing.

4.1.2. Tier 2: Factors of Transformation

Some factors derived from the first tier affect the transformation and expansion of informal settlements. These factors were further developed to form the second tier and are divided into spatial and non-spatial factors. The spatial factors involve economic growth, informal economy, and informal politics. While spatial factors include situational factors, site and topography, and circulation configuration, each can be deduced from the physical characteristics of informal settlements.

Non-Spatial Dimension

Economic Growth: The changing pattern of development results from economic growth. Both settlements have a strong informal real estate market. In Ezbet El Haggana, the public partnership commenced in 2004, wherein the informal contractors partnered with the house owners to replace their accommodation with apartment buildings. This resulted in better quality houses and proved to be a good mode of investment. On the contrary, in Ard El Lewa, the demolition of old buildings occurred either to change their use or to build better housing. The new building either provided bigger apartments or the commercial use was extended to several floors, or sometimes the entire building. Thus, the genesis of the economic growth of informal settlements can be traced back to the public partnerships with the real estate market. This transformed the urban fabric and the land use of the redeveloped areas.

Informal Economy: The case studies and the study of other informal settlements suggest that not all businesses within the informal settlements are legal. Few workshops that hire workers on per-day labour charges are informal. These involve domestic workers, construction workers, day labourers, and salespeople working in the shops of formal districts, etc. Workers living in informal settlements create and sustain the informal economy and as a result, the mixed-use areas increase gradually.

Informal Policies: The planning policies of the government that deal with informal settlements affect their growth pattern. The first positive move was the extension of the infrastructure network of different utilities to the areas. This action was a recognition of the area and the rights of the people to live there. Later, the Informal Settlements Development Fund (ISDF) categorised both settlements under unplanned areas. This was especially beneficial to Ard El Lewa, where the reconciliation law allows residents to legalise their houses. Thus, the policies for the informal settlements gave a sense of security to existing and future residents.

Spatial Dimension

Situational Factors: Both areas have almost reached their horizontal expansion limits. Ezbet El Haggana is surrounded by Nasr City, Cairo-Suez Road, and a gated community built by the military, covering all borders. Additionally, Ard El Lewa has reached its horizontal expansion limits because of the three transportation corridors and a surrounding informal settlement. This has limited their physical growth and has led to vertical expansion and the densification of both areas.

Site and Topography: The street network and built form of the two settlements responded to the site characteristics. Ezbet El Haggana is built on empty desert land, which explains its organic urban form, where the attached buildings take advantage of all available space. On the contrary, Ard El Lewa followed the agricultural plotting systems and irrigation canals. This resulted in a compact urban grid form with narrow streets.

Circulation Configuration: Although the Ezbet El Haggana’s organic form and Ard El Lewa’s grid form respond to the topography, they appear to be contained and focusing inwards. This means that all the important locations are covered and protected territories and the residents had more control over the open spaces and their streets.

4.1.3. Tier 3: Informal Urban Form vs. Sustainable Urban Indicators

Under the concept of “sustainable development”, governments, academics, and planners are exploring how to improve the design of cities in a quest for better, more sustainable cities. In response, different concepts emerged in the Global North, such as Neo-traditional Developments, New Urbanism, and the Compact City. However, in the Global South, the most common mode of urban space production is informal. Informality and informal settlements became the norm in and around every metropolitan region and big city in the Global South, hence the need to draw parallels between the characteristics of the informal settlements and the concepts of the Global North to address informality.

One of the research objectives is to cross-examine the characteristics of the informal settlement with different sustainable urban form indicators. As a part, the urban form of informal settlements is explored as one of the sustainable concepts and ways to improve the Informal Settlements Framework. To do so, the research framework proposes a set of indicators derived from different concepts of sustainable urban forms, implemented in the Global North. These indicators are used to examine the characteristics of the case studies.

Compactness: In both cases, the urban form is very compact and is evident from the population density, street network, and building forms. The population density of Ezbet El Haggana is 1330 person/feddan, and Ard El Lewa is 638 person/feddan. This high density is reflected in the built form of both settlements, which are represented by high-rise apartment buildings with 10 to 15 stories. The limited horizontal expansion and increase in population have resulted in high-density compact building forms with smaller dwelling sizes.

Walkable: The walkability in informal settlements depends mainly on the street width and the interconnectivity of the street networks. Although the street width of both areas is narrow, even so, the hierarchy of primary, secondary, and tertiary streets is clear and assists in wayfinding. The commercial activities on the ground floor and their extension onto the streets create narrow passageways where walking is easier and preferred. Moreover, the work-live-play connectivity within the settlements encourages walkability.

Mixed-use: Both informal settlements are self-sustainable and are characterised by mixed-use. The economic activities range from unskilled workers to home businesses and from commercial shops to highly skilled offices and workshops. For instance, Ezbet El Haggana and Ard El Lewa have car repair shops and commercial shops along the main streets, while Ard El Lewa’s inner streets are home to wood and metal workshops.

High Density: Both areas have a high population density, which is visible by the compact urban form with 100% plot coverage, built-to-edge, and the vertical expansion of buildings. The vertical expansion not only supports the family and the extended family but is also a source of income and a form of investment. However, most importantly, it is a response to the increasing population and the need for housing units.

Diverse Housing: Ezbet El Haggana has a diverse housing typology. Although the apartment blocks are a predominant building typology, detached family houses and close-knit semi-detached houses are also seen. The apartment buildings offer different unit areas which cater to diverse socio-economic groups. In addition, the rental scheme offers different tenure types and is flexible to suit the needs of the residents.

Sense of Community: The community in both areas originates from the native places from where a family member had migrated to Cairo for work. Once settled, the rest of the family migrates. Over time, extended family members and friends start to move near each other, resulting in strong social ties with common cultural backgrounds, which creates a strong sense of community.

Street Characteristics: The hierarchy of streets in informal settlements is evident. The primary streets are the widest, where cars, trucks, and pedestrians share the space and commercial activities intensify. The secondary streets are narrower, and the predominant users are pedestrians and residents. They host commercial activities that serve the everyday needs of the residents. Tertiary or residential streets are the narrowest, with workshops and shops that serve the residents; this is where the social activities intensify.

Street Life: In both cases, streets are vibrant and active throughout the day owing to their multiple uses. The streets are not only for movement but are also expressions of culture, social life, and diverse and unique social and economic activities. It is an extension of the home for family and neighbours and a playground for children. Additionally, the extension of shops and workshops onto the street, and the display of products by the vendors, generates constant movement.

Common Public Spaces: Public spaces are limited to streets and building rooftops in Ard El Lewa and Ezbet El Haggana. Residents, pedestrians, and shop owners use the streets, while rooftop usage is shared among all building owners. Social activities at a large scale can take place in the streets or rooftops in accordance with the community norms.

Sense of Place: The sense of place and sense of responsibility stems from the different uses of public spaces (i.e., streets). It is governed and organised by residents’ cultural traditions and norms. The appropriation of space hints at the sense of place. For instance, people could put street furniture in front of their houses to sit and socialise in their free time. The strong sense of place originates when the houses are constructed and owned and one has lived there for a longer duration.

Infill Development: The development of informal settlements always occurs next to each other, demonstrating an efficient use of space. In both cases, the current trend of demolishing old buildings and replacing them with new ones can be seen. They demolish one or more small buildings and replace them with bigger and better ones. This trend is evident from the strong informal real estate market in Ard El Lewa and Ezbet El Haggana.

Diverse Transportation: The primary method of transportation in both areas is walking because of their mixed-use and compact urban form. The second most used vehicle is a tuk-tuk, which is used when someone is in an emergency or needs to cover a long distance. In addition, pick-up trucks are arranged to help people during rush hour in Ezbet El Haggana and act as an extra source of income for the drivers. Public buses and minibusses are used while travelling to the other districts.

4.2. Validation of the Results against the Premise of the Study

Relating the results to background work in the form of a preliminary examination of different informal settlements across the Global South (Table 6) was undertaken with an emphasis on the physical, social, and economic characteristics. Evidently, different relations between the characteristics were established as a base for generating the framework. In adopting a relational approach, the characteristics of the built environment appear to all be interconnected. The urban form is shaped according to the socio-economic characteristics of residents. The presence of strong social networks helps to attract new families as well as meet their everyday needs. Additionally, the informal economy is vital for income-generating activities that ultimately transform the built environment. The informal–formal relations are present, and social and economic reciprocity takes place between both. Notably, the instigated framework (Figure 5) is underpinned by in-depth analyses of the various characteristics and represents the different relations between them; such characteristics enabled the development of the CISF which is tested and validated utilising the two cases of Greater Cairo that corroborate significant correlations.

Table 6.

Characteristics of informal settlements in various contexts across the Global South.

4.3. External Validation of Results

The globalisation and industrialisation of cities in the Global South attracted individuals and communities, from peripheral and rural areas, seeking better services and employment opportunities. The relational approach adopted in this study is appropriate for understanding the reasons for both non-spatial and spatial factors that influenced the development of informal settlements. The body of knowledge reviewed in this study suggests a complex web of reasons behind the development of informal settlements that was reflected in the development and testing of the CISF.

First, natural rapid urbanisation increases the attractiveness of cities to rural inhabitants who seek better employment, better social services, and better education, among other reasons. Rapid urbanisation created pressure on the housing sector with extra demand coupled with a lack of affordable housing for rural migrants. Concurrently, the private sector could not supply such housing because of the building regulations and standards, which would render any formal housing unaffordable to a large portion of the population. The unaffordability of formal housing combined with the shortage of social housing, low incomes, internal migration, and increased poverty made informal settlements the only option for shelter.

The spontaneous growth of informal settlements to fulfil the needs of inhabitants created unique, dynamic, and constant adaptations to the situation. They emerge on any vacant land, whether in the city centres or on the periphery of cities and are typically close to employment opportunities with reasonable access to transport. The urban fabric is organic or follows a grid of the old division of agricultural lands. Mixed-use, walkable, and high-density characterises such areas which do not follow the regulations or rules of the formal city. At a social level, inhabitants rely on established social and economic networks to compensate for the lack of urban services and infrastructure, which became crucial in dealing with their everyday needs. In essence, this validates the need for a validated framework that could be applied to various contexts where the proliferation of informal settlements has more or less similar reasons behind their emergence and evolution.

4.4. Importance of the Results

The results of this study contribute added dimensions and expansion to the existing body of knowledge on informality and informal settlements. The implementation of the CISF embeds various sustainable urban form concepts and demonstrates characteristics of informal settlements as a web of relations that enables a holistic understanding of their complexity. It also offers a wider perspective on informal–formal relations that influence their growth and development. By and large, this provides a responsive approach for the examination of informal settlements and represents a departure from other studies that deal with informal settlements by surveying the existing situation and planning according to what the settlement lacks or needs. However, due to its qualitative nature, this approach does not allow for generating data sets that allow subsequent intervention for upgrading and future renewal. The framework places emphasis on informal–formal relations, which are crucial for understanding different aspects of informal settlements that could significantly impact future planning. Embedding sustainable urban development concepts as a central element, the CISF clearly aligns with Sustainable Development Goals by interrogating the informal urban form that enables effective planning in the early stages of intervention projects.

4.5. Study Limitations and Future Research

The CISF represents an important starting point to articulate the key qualities of informal settlements. However, it was tested only in two cases in the context of Greater Cairo for validation purposes rather than generalization. This instigates the call for testing it in other contexts in Egypt and the wider Global South. Expanding the testing of the CISF would allow for refining, adaptation, and generalisation. The holistic nature of the CISF invites further examination and focus on specific components. In particular, aspects that pertain to linking affordability and sustainability, climate change impacts, governance, and social innovation [48,49,50,51,52] would be seen as priorities for further studies, given the fact that informal settlements represent the key provision of affordable housing in many contexts within the Global South. There is a need to focus on climate change to keep up with current research in different contexts and disciplines. Informal settlements should be treated equally.

5. Conclusions

Ezbet El Haggana and Ard El Lewa are some of the oldest informal settlements in Greater Cairo. Both are typical examples of their respective typologies; Haggana is a squatter settlement on desert land, and Ard El Lewa is an illegally subdivided agricultural land. The Informal Settlements Development Fund (ISDF) has categorised both as unplanned areas.

Although these two cases are different typologically, the study reveals that they share many similarities. They are dense, compact, and walkable informal areas with mixed land uses. Additionally, typical of any informal settlements, they lack proper services, open spaces, and green areas. However, both are located on the edge of two well-established formally developed districts that offer access to services and transportation links to these areas and the rest of Greater Cairo. Ezbet El Haggana and Ard El Lewa are on the eastern and western periphery of Greater Cairo, respectively, near the Ring Road around Greater Cairo. Additionally, there is increased potential concerning their locations due to the development of the 6th of October City and New Cairo cities. Ezbet El Haggana is in the centre of Nasr City and New Cairo and Ard El Lewa is between the 6th of October City and Mohandessin, facilitating social and economic exchange between the informal settlement and the formal districts.

The topography shaped the street network of both settlements, thus creating three types of streets. The primary streets facilitate the presence of commercial activities and street vendors. The secondary and residential streets are more pedestrian-friendly and have more social activities. Moreover, the building forms in both settlements are different; in Ezbet El Haggana, there are three housing typologies [53], houses, apartments, and family houses, while in Ard El Lewa, only one typology is evident, namely, the apartment building [54]. In all housing typologies, the ground floor is usually reserved for commercial use, encouraging the mixed land use. Furthermore, the compact urban form leaves only the streets and rooftops to be used for any social activity.

With regards to social aspects, neither area has public services, except for two schools in Ezbet El Haggana, which are in poor condition. To compensate for the lack of services, the population of rural migrants enabled the development and maintenance of strong social ties with the NGOs and CBOs. These ties nurtured a sense of security within the residents in their respective areas and encouraged seeking help from community leaders to resolve conflicts. These settlements also express the village traditions and norms by building pigeon towers and animal breeding on rooftops and socialising on streets and rooftops. In Ezbet El Haggana, the diverse cultural background is due to the residents who are rural migrants from Suez Canal cities during the 1967 war, Christians from Minya, and a small number of Sudanese, Syrians, and Somali refugees [41].

Economically, residents engage in different employments and activities that range from day labourers to domestic workers, business owners, engineers, and government employees. In addition, Ezbet El Haggana is known in the surrounding areas for car repair shops and waste recycling, especially iron, whereas Ard El Lewa has wood and metal workshops on its inner streets.

The difference in tenure types for both areas is due to their legal status. Both settlements have diverse tenure types, including owned, rented, and invented informal contracts that suit particular situations, although they differ in land ownership. Ezbet El Haggana land is occupied illegally, while Ard El Lewa residents own their land, but the construction is illegal. The legality of the land influences the building quality (temporary/permanent) in both settlements. Ezbet El Haggana shows diverse building qualities, ranging from poor, unsafe Suessi houses to formal-city-quality apartment buildings. In contrast, Ard El Lewa has better-quality buildings because of its legal status.

Finally, the transformation factors are very similar. The non-spatial factors are significant as both areas experienced economic growth, which is evident in the flourishing informal real estate market and empty housing units, resulting in a change in the development pattern. Second, both classify under the unplanned category, where no eviction can occur. The extension of utility networks to the settlements by the government signifies an unofficial recognition of each area that increased the sense of security and investment within them. Likewise, spatial factors are very similar. First, both have limited horizontal expansion due to rigid boundaries that run along the perimeter, thereby increasing vertical expansion. Second, the circulation configuration is very similar, as the compact urban form with commercial uses intensifies in the main streets, and social uses proliferate in secondary and residential streets. On the other hand, the site factors differ as each is developed on different types of land (desert vs. agricultural).

The Characterisation of Informal Settlements Framework (CISF) presents various relations between the characteristics and how they influence one another. The establishment of relationships between these characteristics emerges into a network that shapes the informal built environment. The framework has three tiers (Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7). The first tier represents the physical, social, and economic characteristics and relationships between them. The second tier includes the factors of transformation, which identify the non-spatial and spatial factors influencing the change in development and future expansion. Finally, the third tier examines the sustainable urban indicators cross-examined with the different characteristics of the settlement.

The characteristics of Ezbet El Haggana and Ard El Lewa tested the framework and adapted to the two main typologies of informal settlements found in Egypt. Tier 1 (Figure 5 and Figure 8) presents the different relationships between the physical, social, and economic features and their correlations. The informal environment is very complex because no guidelines were used in its design. However, as it expands, it responds and adapts to residents’ needs and socio-economic changes.

Figure 8.

The different relations between the physical, social, and economic characteristics of informal settlements.

The second tier studies the different non-spatial and spatial factors and represents the factors that influence the change and expansion of informal settlements. Understanding the reasons behind the changes in informal areas requires transformation factors. The third and final tier examines the informal settlements against the sustainable indicators. The study shows that the features of sustainable urban forms are present in informal settlements, proving that they can be seen as a different concept of sustainable informality. Like in Greater Cairo, informal settlements cover more than half of the built-up area. Therefore, the expansion and revitalization of this urban form could offer the best solution for Egypt and other developing countries.

The research tested the three-tiered CISF and proved that it could be applied to different typologies in Egypt and adapted to different contexts. The framework operates on three levels: identifying different characteristics and relations between them, examining the transformation factors that influenced the changes and expansion, and examining the informal settlements from the lens of the sustainable urban form indicators. This represents an important step for planners and decision-makers towards controlling and integrating informal settlements into the urban structure of the city. One of the success factors for informal upgrades is thoroughly studying the informal settlement, an activity for which this framework offers a guide.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B.; methodology, A.B.; software, A.B.; validation, A.B.; formal analysis, A.B., A.M.S. and B.D.; investigation, A.B.; data curation, A.B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.B., A.M.S. and B.D.; writing—review and editing, A.B., A.M.S. and B.D.; visualization, A.B.; supervision, A.M.S. and B.D.; project administration, A.B., A.M.S. and B.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated from the fieldwork are included in the body of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Tsenkova, S. Self-Made Cities: In Search of Sustainable Solutions for Informal Settlements in the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe Region; United Nations: New York, NY, USA; Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nabutola, W. Affordable Housing: Upgrading Informal Settlements in Kenya. In Proceedings of the FIG Working Week 2005 and 8th International Conference on the Global Spatial Data Infrastructure (GSDI-8): From Pharaohs to Geoinformatics, Cairo, Egypt, 16–21 April 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, E. Regularization of Informal Settlements in Latin America. In Policy Focus Report; Lincoln Institute of Land Policy: Cambridge, UK, 2011; pp. 1–49. [Google Scholar]

- UN-Habitat. Issue Paper on Informal Settlements. In Habitat III Issue Papers; UN-Habitat: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations: Department of Economic and Social Affairs: Population Division. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Alder, G. Tackling poverty in Nairobi’s informal settlements: Developing an institutional strategy. Environ. Urban. 1995, 7, 85–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wekesa, B.W.; Steyn, G.S.; Otieno, F.A.O. A review of physical and socio-economic characteristics and intervention approaches of informal settlements. Habitat Int. 2011, 35, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, B. The environmental impacts and public costs of unguided informal settlement; the case of Montego Bay. Environ. Urban. 1996, 8, 171–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguluma, H.M. Housing Themselves. Ph.D. Thesis, Royal Institute of Technology (KTH), Stockholm, Sweden, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Opoko, A.P.; Ibem, E.O.; Adeyemi, E.A. Housing aspiration in an informal urban settlement: A case study. Urbani Izziv 2015, 26, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, R.; O’Leary, B.; Mutsonziwa, K. Measuring quality of life in informal settlements in South Africa. Soc. Indic. Res. 2007, 81, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlSayyad, N. Urban Informality as a New Way of Life. In Urban Informality: Transnational Perspectives from the Middle East, Latin America, and South Asia; Roy, A., ElSayyad, N., Eds.; Lexington Books: Lexington, MA, USA, 2004; pp. 7–30. [Google Scholar]

- De Soto, H. The Other Path: The Invisible Revolution in the Third World; IB Tauris and Co: London, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M.H.; Sulaiman, M.S. The Causes and Consequences of the Informal Settlements in Zanzibar. In Proceedings of the XXIII Congress of the International Federation of Surveyors, Munich, Germany, 8–13 October 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Potsiou, C. Policies for formalization of informal development: Recent experience from southeastern Europe. Land Use Policy 2014, 36, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, A.M. Typology of informal housing in Egyptian cities: Taking account of diversity. Int. Dev. Plan. Rev. 2002, 24, 177–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovey, K.; King, R. Forms of informality: Morphology and visibility of informal settlements. Built Environ. 2011, 37, 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCartney, S.; Krishnamurthy, S. Neglected? Strengthening the Morphological Study of Informal Settlements; SAGE Open: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Volume 8, pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, D.; Lees, M.H.; Palavalli, B.; Pfeffer, K.; Sloot, M.A. The emergence of slums: A contemporary view on simulation models. Environ. Model. Softw. 2014, 59, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, P.P.; Lowry, J.H.; Weber, E. Global environmental impact of informal settlements and perceptions of local environmental threats: An empirical case study in Suva, Fiji. Habitat Int. 2017, 69, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, M.; Posel, D. Here to work: The socioeconomic characteristics of informal dwellers in post-apartheid South Africa. Environ. Urban. 2012, 24, 285–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas Rivera, C.d.C. Place Attachment in Informal Settlements: The Influence of Community Leaders in Mexico. Ph.D. Thesis, Univeristy of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, M. Planet of Slums; Verso: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chenal, J.; Pedrazzini, Y.; Bolay, J.C. Tentative Classification of Various Slum Types. In Learning from the Slums for the Development of Emerging Cities; Chenal, J., Pedrazzini, Y., Bolay, J.C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Dovey, K. Informal urbanism and complex adaptive assemblage. Int. Dev. Plan. Rev. 2012, 34, 349–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, A.M. Rethinking urban informality and the planning process in Egypt. Int. Dev. Plan. Rev. 2010, 32, 119–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pojani, D. The self-built city: Theorizing urban design of informal settlements. Archnet IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 2019, 13, 294–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labor Organization. Employment, Incomes and Equality: A Strategy for Increasing Productive Employment in Kenya; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, A. Urban informality: Toward an epistemology of planning. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2005, 71, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutzoni, L. In-formalised urban space design. Rethinking the relationship between formal and informal. City Territ. Archit. 2016, 3, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayat, A. From ‘Dangerous Classes’ to ‘Quiet Rebels’: Politics of the Urban Subaltern in the Global South. Int. Sociol. 2000, 15, 533–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellett, P.; Napier, M. Squatter Architecture? A critical examination of vernacular theory and spontaneous settlement. Tradit. Dwell. Settl. Rev. 1995, 6, 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Abbott, J. An analysis of informal settlement upgrading and critique of existing methodological approaches. Habitat Int. 2002, 26, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Miller, D.L. Determining Validity in Qualitative Inquiry. Theory Into Pract. 2000, 39, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magdi, S.A. Towards Sustainable Slum Development: A Performance Evaluation Approach for Slum Upgrading Plans in Egypt. In Cities’ Identity through Architecture and Arts, 1st ed.; Catalani, A., Nour, Z., Versaci, A., Hawkes, D., Bougdah, H., Sotoca, A., Ghoneem, M., Trapani, F., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2017; pp. 317–331. [Google Scholar]

- Mekawy, H.S.; Yousry, A.M. Cairo: The predicament of a fragmented metropolis. J. Urban Res. J. Fac. Urba Reg. Plan. Cairo Univ. 2012, 9, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendawy, M.; Madi, B. Slum Tourism: A Catalyst for Urban Development? Reflections from Cairo’s Ashwa’iyat (Informal Areas). In Dynamics and Resilience of Informal Areas: International Perspectives; Attia, S., Shabka, S., Shafik, Z., Ibrahim, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 57–72. [Google Scholar]

- Kipper, R.; Fischer, M. Cairo’s Informal Areas between Urban Challenges and Hidden Potentials; GTZ: Cairo, Egypt, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nadim, W.; Bock, T.; Linner, T. Technological implants for sustainable autonomous upgrading of informal settlements in Cairo-Egypt. In Proceedings of the SB14 World Conference, Barcelona, Spain, 28–30 October 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sims, D.; Sejoume, M.; El Shorbagi, M. The Case of Cairo, Egypt. In Understanding Slums: Case Studies for the Global Report on Human Settlements; UN-Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Tadamun. Available online: http://www.tadamun.co/?post_type=city&p=5469&lang=en&lang=en#.YH17fi0RpB1 (accessed on 5 October 2020).

- Al-Shehab Institute. Social Study of the Social, Economic and Educational Causes of Dropping out School in Ezbet El-Haggana; Al-Shehab Institute: Kairo, Egypt, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bremer, J.; Bhuiyan, S.H. Community-led infrastructure development in informal areas in urban Egypt: A case study. Habitat Int. 2014, 44, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, A.M. Tilting at Sphinxes: Locating Urban Informality in Egyptian Cities. In Urban informality: Transnational Perspectives from the Middle East, Latin America, and South Asia; Roy, A., ElSayyad, N., Eds.; Lexington Books: Lexington, MA, USA, 2004; pp. 171–208. [Google Scholar]

- Shawky, K.A.; Abd Elghani, A.A.A. Urban analysis for informal housing areas Urban form indicators for replacement projects of deteriorated housing areas. J. Urban Res. 2018, 29, 51–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eissa, D.; Khalil, M.H.; Gabr, A.; Abdelghaffar, A. From appropriation to formal intervention: An analytical framework for understanding the appropriation process in residual spaces of Cairo. Front. Archit. Res. 2019, 8, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagati, O.; Elgendy, N. Ard Al-Liwa Park Project: Towards a New Urban Order and Mode of Professional Practice. In Proceedings of the Cities to be Tamed? Standards and Alternatives in the Transformation of the Urban South, Milan, Italy, 15–17 November 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Salama, A.M. Trans-disciplinary knowledge for affordable housing. Open House Int. 2011, 36, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milovanović, A.; Nikezić, A.; Ristić Trajković, J. Introducing Matrix for the Reprogramming of Mass Housing Neighbourhoods (MHN) Based on EU Design Taxonomy: The Observatory Case of Serbia. Buildings 2023, 13, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, A.M. Integrationist Triadic Agendas for City Research: Cases from Recent Urban Studies. J. Arch. Urban. 2019, 43, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Nachar, E.; Abouelmagd, D. The Inter/Transdisciplinary Framework for Urban Governance Intervention in the Egyptian Informal Settlements. Buildings 2023, 13, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolopoulou, K.; Salama, A.M.; Attia, S.; Samy, C.; Horgan, D.; Khalil, H.A.E.E.; Bakhaty, A. Re-enterprising the unplanned urban areas of Greater Cairo-a social innovation perspective. Open House Int. 2021, 46, 189–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boules, D.E.; Sherif, L.A.; Khalil, M.H. Residential typologies as a tool to trace the urban transformation of Ezbet El-Haggana. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2020, 67, 1285–1304. [Google Scholar]

- Elgendy, N.; Frigerio, A. Right to the City and Public Space in Post-Revolutionary Cairo. In The Routledge Handbook on Informal Urbanization, 1st ed.; Rocco, R., van Ballegooijen, J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).