Abstract

Despite substantial investments and efforts by governments, construction organisations, and researchers, the construction industry remains one of the most male-dominated industries in Australia, with women being underrepresented numerically and hierarchically. Efforts to attract and retain women in construction have been implemented inconsistently on an ad hoc basis. As part of a larger research project that focuses on retaining women in the Australian construction industry, this research conducts a systematic literature review (SLR) in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines. The objective is to explore the factors that influence women’s careers and their experiences in the Australian construction industry that have been identified in the literature over the past three decades. Additionally, the findings are anticipated to inform future efforts to evaluate the effectiveness of current initiatives to retain women and develop a framework for enhancing women’s experiences and retaining them in this profession. This SLR revealed that excessive and rigid work hours, gendered culture and informal rules, limited career development opportunities, and negative perceptions of women’s abilities are the main factors and issues that cause women to leave the industry. Among these, rigid and long work hours seem to be the foremost factor to be prioritised. Understanding the roles of key variables in driving this cultural change is important to ensure that concrete progress is made. The paper draws three major aspects from the literature in which solutions and policies can be researched, designed and implemented.

1. Introduction

Women certainly must be resilient and develop their technical, interpersonal, and coping skills to have a successful career in the construction industry. However, this view individualises the problem, focuses on short-term solutions to “fix women”, and dismisses the need to transform the industry’s culture and provide a safer working environment for women [1].

As a male-dominated workplace, the percentage of women in construction is low, between 9 and 13%, and has stayed relatively constant throughout the years despite efforts to diversify the workforce [2]. U.S. Labour Force Statistics show that female labour force participation was 9.9% in 2018 and 10.9% in 2021. In Germany, Belgium, Italy, Spain, and Portugal, approximately 9% of construction workers are female, whereas the corresponding statistics for Canada and the United Kingdom are below 14% [3].

Being the third-largest industry in Australia, construction is forecast to increase at a 2.4% annual rate through 2023, making it the second-largest sector with the greatest expected employment growth (10%) [4]. The participation rate of women in this key economic sector is extremely low, dropping from 17% in 2006 to 12.9% in 2020 [5]. The need for more female participation in the construction sector has been highlighted to address the labour shortage, promote equality, and increase productivity [2].

Australia’s federal and state governments have initiated and implemented numerous initiatives to attract and retain women in this profession. The Queensland Government, for instance, actively encourages women to enter the industry and sets a target to surpass the National Association of Women in Construction’s 11% target for women in construction-related occupations [6]. Similarly, the Victorian Government introduced a new policy mandating greater female participation in the construction industry and allocated $5 million to promote the policy’s implementation.

Despite government, industry, and educators’ efforts to attract women into these jobs, they show limited success [6,7]. Australia’s construction industry, one of the country’s leading sectors, faces an impending labour market shortage, causing the industry to overheat nationwide [8]. The sector is missing out on a large number of talented individuals who do not engage or pursue a career in this sector. Hence, women represent an underutilised resource for meeting the labour requirement in this industry [9]. This is not a new problem in this industry; in fact, there is strong evidence that tackling the gender disparity has been necessary since the latter half of the 20th century [10].

Even though several studies have explored the education, recruiting, and retention of women in the sector, the reasons for women being underrepresented in construction are still not entirely understood [11,12]. The underutilisation of women’s skills and abilities is a compelling reason for scholars worldwide to investigate women’s attraction, retention, and experiences in the construction industry [9]. Hegart [13], for instance, examined how women in New Zealand’s construction industry entered, progressed through, and eventually left the profession between 2010 and 2018. Perrenoud et al. [14] evaluated the most relevant elements in attracting and retaining women in managerial occupations in the U.S. construction industry. They surveyed 686 construction sector managers and found that women enter the field later than men. Additionally, women in executive positions had much less vocational training than their male counterparts.

In Turkey, Çınar [15] conducted qualitative field research consisting of in-depth interviews with 32 construction workers. The findings show that by defining construction labour in terms of physical capacity, a consequence of the labour conditions shaped by the practice of subcontracting, construction work has become naturalised as a male occupation. The findings also suggest how construction brings a wide range of masculinities that intersect with a working-class perspective based on men’s traditional roles as heads of households and protectors of their families. In Brazil, 17 employees and engineers who work/have worked at construction sites were interviewed [16]. Their research found that women are typically engaged near the end of the construction period, which raises the issue of the gendered division of labour. The effects of the glass ceiling and the leaky pipeline phenomena, together with harassment, discrimination, and sexism, were apparent. Hickey and Cui [17] examined engineering and construction executive leadership jobs in the U.S and found that women hold 3.9% of executive engineering positions. Their findings suggest that most of these organisations lack gender diversity in their leadership cultures and mission statements.

Australia’s struggle to solve this severe gender disparity has provided a good case study for researchers and organisations attempting to address this issue. Early research by Lingard and Lin [18] evaluated the effect of various family and work environment variables on women’s careers in construction. Loosemore and Galea [19] found fewer conflicts would occur if more women worked in construction in Australia.

Since then, additional studies have been undertaken to uncover the difficulties experienced by Australian women in this industry. Nevertheless, our research is based on a recommendation made by Zhang et al. [20], who conducted 19 interviews to investigate the transition experiences from university to work for early career female professionals. They suggested that “if retention, not simply attraction, is the key to increasing female participation in construction, workplace structure, gender fairness, and rigid work practises must be reconsidered” [20]. It is, however, unpresented in the literature what happens to women after their introduction to the profession to eradicate impediments to retention. This situation has been dubbed the “leaky pipeline”, implying that a large number of women in construction are filtered out throughout the career pipeline, leaving only a handful at the other end [1,20]. To bridge this gap, the following research questions are formulated:

- What are the key factors influencing women’s retention and engagement in Australia’s construction sector?

- What solutions in the literature have been proposed to retain women in the Australian construction sector?

This study is part of a broader, ongoing project that intends to assist governments and policymakers by improving the effectiveness of programmes and projects implemented in Australia and their influence on the retention of women in the construction industry. It intends to explore the areas of improvement in the environment of the Australian construction industry in order to retain women who have commenced or established a career in this field. We believe that these improvements will result in fewer women leaving the profession, a more positive image of the industry, and a more diverse and inclusive workplace. Additionally, this will encourage more women to join the sector.

To answer the research questions, this study conducted a systematic literature review (SLR) on prior studies and lays the groundwork for a more extensive and in-depth investigation of the factors and issues that affect women’s retention and career advancement in the construction industry in order to develop a framework for evaluating the initiatives and policies in place to retain women in this industry.

Following the introduction, Section 2 describes the study’s methodology in detail. Then, Section 3 presents the descriptive and content analysis of the reviewed studies. Following the identification of the key factors influencing women’s retention, Section 4 provides a detailed discussion of the results. In addition, the proposed solutions in the literature are explored. The information presented in this paper is based on a review of prior studies and lays the groundwork for a more extensive and in-depth investigation of the factors and issues that affect women’s retention and career advancement in the construction industry in order to develop a framework for evaluating the initiatives and policies in place to retain women in this industry.

2. Methodology

Using systematic literature reviews (SLRs), researchers may reliably and openly pinpoint the most pertinent material and follow consistent review processes [21]. SLRs provide readers with a comprehensive overview of the literature and help them discover research gaps in the field. Thus, an SLR can be considered a platform for advancing knowledge. An SLR was conducted to identify major issues that influence women’s careers and their experiences in the Australian Construction industry. To ensure reporting bias minimisation, it is essential that systematic reviews adhere to a defined methodology and protocols before beginning the review process. For instance, the protocol identifies the study question and outlines the method in sufficient detail to permit replication by others (research techniques made simple: assessing the risk of bias in systematic reviews). Similarly, this study established the research question(s) and outlined the key steps to answer those questions in advance.

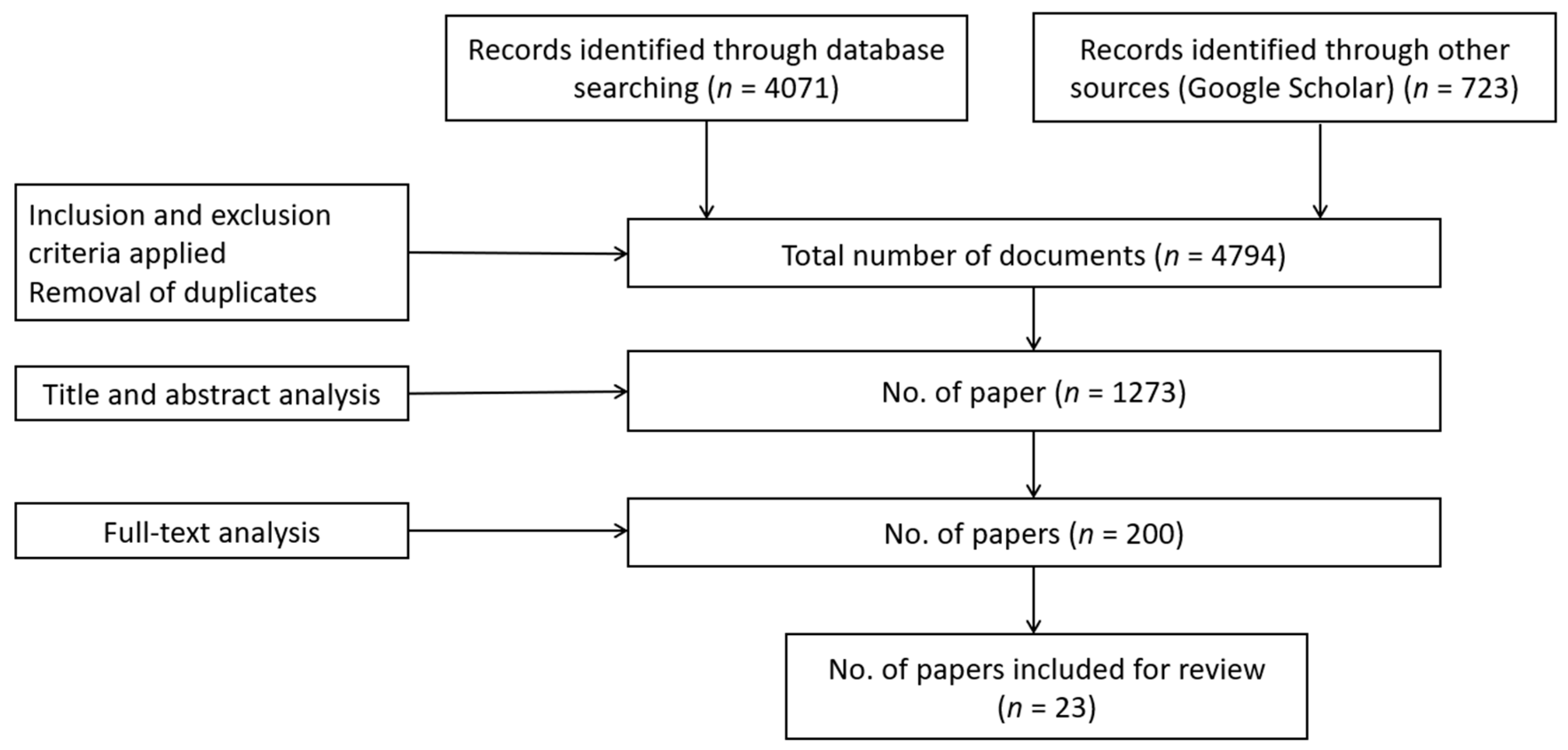

The SLR was conducted employing the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines consisting of four phases: identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion for review [22]. Similar studies [23] have recommend adopting the PRISMA technique to decrease bias and increase the review’s rigour and replicability. The process is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart of selected articles (prepared by the authors).

In the identification phase, Scopus and ProQuest were selected as the preferred databases for collecting existing articles. Keywords chosen in this study were related to “construction industry”, “women”, “retention” and “Australia”. Two search strings were developed, focusing on different synonyms:

- Female* OR women OR woman OR girl* OR feminist* OR “gender diversity” AND “construction industry” OR “building industry” OR “construction management” OR “construction companies” OR “construction company” OR “property industry” OR “built environment”.

- Female* OR women OR woman OR girl* OR feminist* OR “gender diversity” AND “construction industry” OR “building industry” OR “construction management” OR “construction companies” OR “construction company” OR “property industry” OR “built environment” AND Retention or Retain.

The search strings were applied to Scopus and ProQuest, by which 4071 documents were identified. While Google Scholar provides very low-precision search results and does not support many of the features required for systematic searches [5], it was used to find results that may not have been found elsewhere due to the limited research in this field in the Australian construction context. In total, 723 documents were identified by Google Scholar.

As seen in Figure 1, the search yielded 4794 articles. In the screening phase, inclusion and exclusion criteria were established to choose relevant articles, including articles published in peer-reviewed journals, available in full text, written in English, published in the last 30 years and researched in the Australian context.

Additionally, duplications were removed among Scopus, ProQuest and Google Scholar at this stage, thus resulting in 1273 articles. The titles and abstracts of these 1273 articles were screened to identify relevant articles. Only 200 articles were deemed eligible at this stage. These 200 articles were read thoroughly (full text) by six authors in the eligibility stage to determine if they met the inclusion criteria. A quality assessment strategy was also implemented to assure the quality assessment of the identified studies. It was carried out using an Excel spreadsheet that included the quality evaluation criteria and rating scale. It was based on studies such as this.

In addition to the inclusion criteria, the research team carefully determined the quality evaluation criteria to ensure that the papers could directly contribute to the research questions. The scoring method (see Table 1) was also developed on the basis of similar studies [24] and the study team’s observation of the published material. According to the study, each question might be answered with a yes/no scoring method. Following this stage, the study team decided to remove the articles with a ‘no’ answer to the quality assessment questions. For instance, the articles that only discussed gendered cultures without mentioning the construction industry in Australia were removed.

Table 1.

Quality Assessment Criteria.

The articles that discussed broad topics, such as social procurement, marginalised communities, or social disparities, were excluded to maintain the focus on women in construction. The construction profession as a whole was covered, including both skilled labour and management roles.

Only 23 articles met the inclusion criteria and were included for data analysis, forming the inclusion for the review phase. Although the literature acknowledges that there is no specific limit for the number of studies to be included in a systematic literature review [25,26], the reality that only 23 articles met the criteria for inclusion in the final dataset was rather unexpected. Although women’s participation is persistently low in the Australian construction sector [2,5,10], it seems that, so far, only a limited amount of empirical construction management literature has focused on this topic. This absence of extensive research on gender diversity in construction is also evident in other subjects relating to women and minorities in Australia, such as the well-being of LGBTQ+ individuals [27,28], the challenges of culturally diverse disabled people [29], and family and domestic violence [30]. The reason may be uncertain, however, it may be related to the reliance of Australian researchers and policymakers on international research conducted in nations with cultural similarities to Australia. While the number of identified articles is low, several studies in the construction management field have undertaken SLRs using a similar number of studies. For instance, Bridges et al. [31] investigated women’s recruitment and retention in skilled professions and identified only 26 relevant studies between 1998 and 2019. Wang et al. [5] conducted a systematic and thematic review of the literature on women in construction in Australia using a framework for women’s empowerment that included only 20 studies. Kokkonen and Alin [32] conducted a systematic literature review of 15 published papers (2003–2015) to address practice-related management issues in construction projects. This indicates that the systematic approach to the literature review is more critical than the quantity of included studies, which might vary depending on the paper’s topic and selection criteria [33,34].

The finalized set of articles were analysed thematically. A thematical analysis method is one of the generally accepted data analysis techniques that enhances the rigour of qualitative research [5].

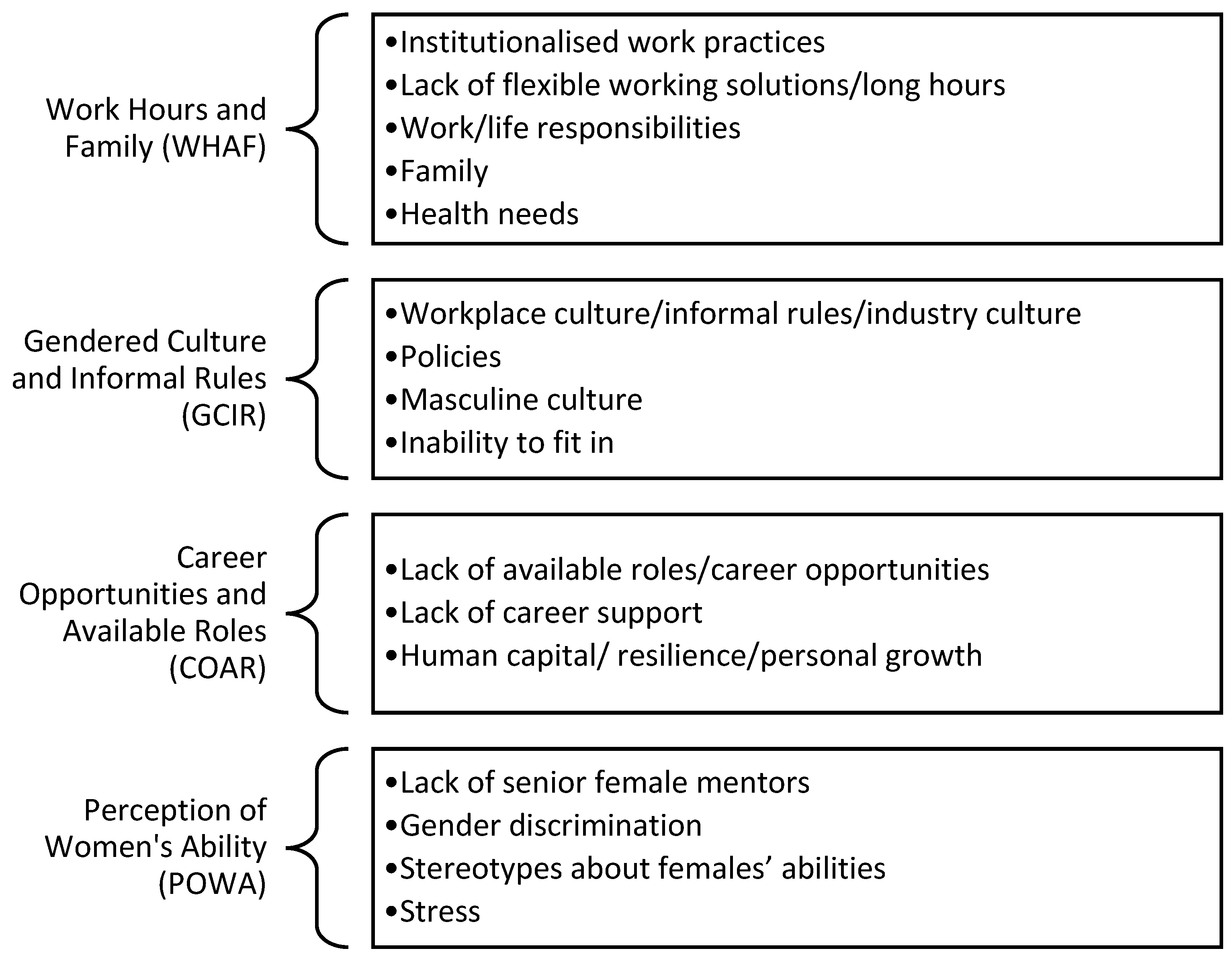

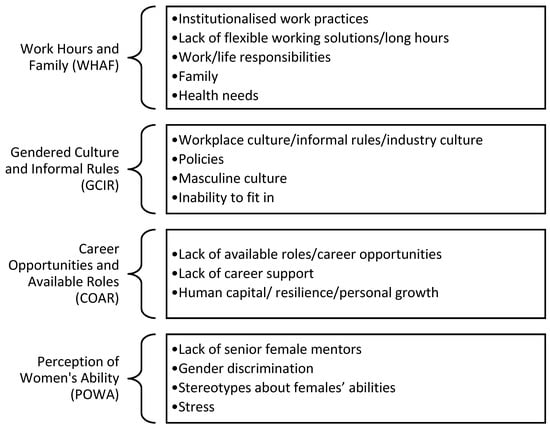

In order to conduct the thematic analysis, it is necessary to establish a content-based coding of the data [35,36]. Likewise, the articles’ contents were coded carefully in this study based on the theoretical basis, research methods, main results, and study focus of the articles in a shared spreadsheet among the research team. All authors iteratively modified, refined, and utilised code categories to conduct the content and thematic analyses of the paper. After the group assessment and thematic analysis of the contents, the results were discussed in a focus group (FG) with four academics and two professionals with more than five years of experience to finalize the major themes. This technique resulted in the identification of four key themes in the literature as follows:

- Work Hours and Family (WHAF);

- Gendered Culture and Informal Rules (GCIR);

- Career Opportunities and Available Roles (COAR);

- Perception of Women’s Ability (POWA).

The identified themes led the research team to discover and classify solutions in the paper’s Section 4.

3. Results

The results were categorised into two sections. A descriptive analysis was carried out to shed light on the sources of publications and annual trends of the reviewed articles. A Content analysis was undertaken to examine the 23 selected papers.

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

As shown in Table 2, the first bibliometric study examines the distribution of articles by publication source.

Table 2.

The number of articles published in journals and conference proceedings.

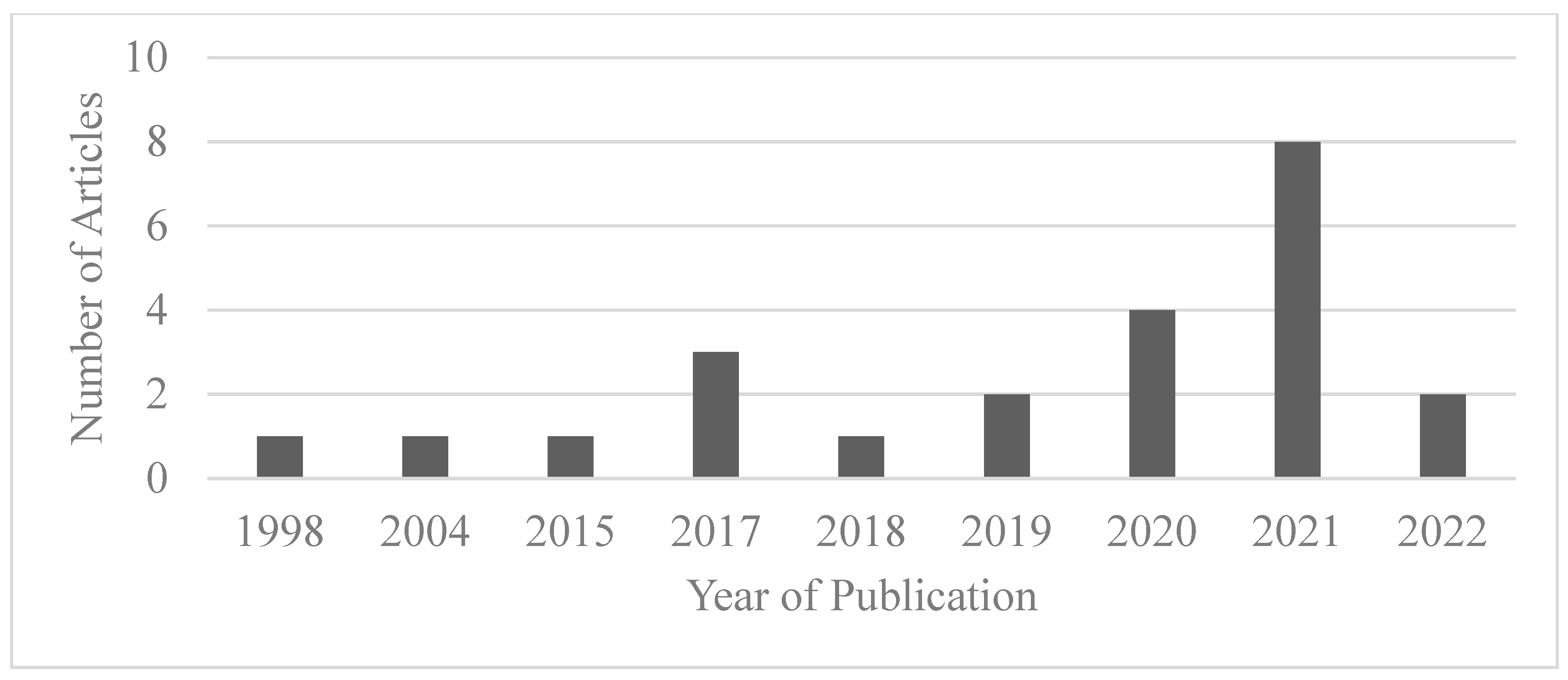

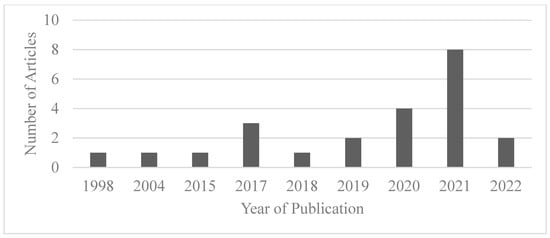

All articles except one were journal publications, with the Construction Management and Economics journal constituting the most prominent source with seven articles. This was followed by the Construction Economics and Building and Gender, Work, and Organization journals. Additionally, Figure 2 presents the distribution of these 23 articles from 1998 to 2022.

Figure 2.

Annual distribution of articles throughout 1998–2021.

Although annual publications remained below three from 1998 to 2019, the numbers indicate a modest rise to eight by 2021. It is noteworthy that more than half of the articles were published after the COVID-19 pandemic began in 2020. The upward trend of articles implies that scholars are becoming increasingly interested in the field, which is expected to continue.

Table 3 includes all the factors and issues identified in each of the 23 papers that were reviewed. This process helped us identify the main themes, which comprise almost all the issues and will be discussed in the next section.

Table 3.

Mapping the challenges affecting women in the Australian construction industry in the literature.

3.2. Content Analysis

The authors conducted a focus group meeting including four academics and two professionals with more than five years of experience to extract the major themes which can be seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The four themes identified in the focus group.

Several challenges and factors influencing women’s retention and engagement in Australia’s construction sector have been discovered through the SLR. While little research has been conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of government policies in retaining women in this sector, researchers have made significant progress in identifying the primary obstacles that would cause women to leave this industry or seek employment elsewhere, as discussed in the following sections. It should be noted that while the emphasis is solely on the Australian construction sector, international research will also be utilised to contextualise the results for the general readership and to inform the subsequent phases of the larger project, which involve investigating these concerns in other countries with comparable cultural environments to Australia.

3.2.1. Work Hours and Family (WHAF)

It is evident from the interviews conducted in Lingard and Lin’s [18] research that the construction industry is infamously known for its rigid and long work hours. This characteristic has been identified as the most significant barrier to gender equality in the Australian construction industry across almost all research efforts. The sector clings to restrictive work norms, such as long work hours and tight timetables. Historically, long working hours and rigid work practices have been identified as the top reason for women leaving the construc-tion industry [37,42,45,48,49]. Heavy workload, job pressure and insufficient personal time were identified as the cause of poor life management in the construction industry [45,48]. The representation of women in the industry is low which suggests that the construction industry does not promote flexibility in work and family balance [20,37]. Demanding working conditions and unrealistic expectations are one of the frequently mentioned deterrents for women entering and retaining in the construction industry [7,18,20]. It establishes expectations of “presenteeism” and absolute availability, which are seen as the way things have always been [51]. One interviewee in Zhang et al. [20] stated, “There was a time last Christmas I was doing 80 h a week, and I just can’t maintain that. I can’t maintain that with a family, which I’m hoping to have, but there’s expectations” [20].

According to Galea et al. [49], working on Saturdays regardless of level, responsi-bility, or set work hours has been an unwritten norm in the Australian construction sector. Due to long working hours, women quit or have considered leaving the con-struction profession [37]. A participant in their study stated that “the standard working day is ten hours plus travel and it is exhausting. I am working towards leaving the industry because the hours are simply too much” [37] The practice of long working hours makes the recon-ciliation harder between work and family for women [7,38,45] and domestic respon-sibilities together with family duties [48]. The unsatisfactory life management leads to women developing more health issues, adverse consequences and stress than their male colleagues [7,48]. Although many female construction professionals in the study of Zhang et al. [20] indicated to be in the construction sector for the next five years, the work-family conflict appeared to their significant concern. The work-life balance can be attributed to male-dominated culture [7]. In Baker and French’s [38] study, one female project manager said: “The industry is used to you answering your phone at 6 a.m. in the morning when [the] manager gets onsite, and they’re used to the manager calling you at 7 o’clock at night when they’re still in the office so you just sort of have to be available.” [38]. It is important to note that this phenomenon is not exclusive to women, but men have also struggled due to these work norms, as reflected by the high occurrence of poor mental health.

Women experience a lack of support after returning from maternity leave [38,49]. The need for full-time job availability and the absence of a part-time job poses a signif-icant challenge to women’s retention in the construction industry [38]. Women con-sidered that having a child would have a negative impact on their career progression in this industry [40]. In many cases, a career in the construction industry impacted either their personal relationship or parenthood [7,18,37]. Women expecting to balance both work and family lives encounter challenges and difficulties [7,18,20,45]. The concern is reflected through the following comment by one woman survey respondent in the study of Lingard and Lin [18], “I am extremely worried that should I choose to have a child that my job will be in severe jeopardy” [18]. Therefore, if women professionals are to be retained (not only limited to attraction) in the construction industry, organisations must reconsider gender fairness, workplace structure, and inflexible work practices [20] and launch personal development programmes [7]. In fact, both male and female construction professionals prefer short working hours [7,48]. Research suggests that the investments in work–life balance is positively associated with organisational performance, which would attract and retain women in this industry [38]. One of the promising findings suggests that technology can play an instrumental role in bringing about flexible work practices. With the use of technology, women can monitor the construction sites remotely and utilise more automated construction machines at sites [5].

3.2.2. Gendered Culture and Informal Rules (GCIR)

In the construction sector, aggressive and competitive behaviours are gendered since they are founded on hegemonic male norms and rules of conduct; Chappell [52] refers to this as a “gendered logic of appropriateness”. Both formal and informal rules, regulations and practices in the construction industry are gendered and applied by gendered actors [49]. The informal rule around “masculine-coded behaviours” has made the construction companies “greedy institutions” [49]. Informal rules in the sector have negatively impacted the well-being of employees [51]. Francis [40] surveyed 463 women in professional or management positions in the Australian construction sector and discovered that the less masculine the organisation, the more women progress in their careers. As a result of the cultural pressures of portraying masculinity in male-dominated professions, many employees feel they must hide or ignore their mental health problems in order to demonstrate their “toughness”, “self-reliance”, and “reliability” [53]. As a consequence of being rewarded, these restrictions become ingrained, whereas feminine behaviours (such as exhibiting emotions) are usually sanctioned [51]. Employees in the construction industry are discouraged from displaying help-seeking behaviours and endure unpleasant and harsh working conditions [51]. Women (trades and semi-skilled professionals) in the masculine environment need to be highly resilient to survive and remain in this industry [5]. Women require a higher level of resilience for gender-based hazards than task-related hazards [47]. Along with support from organisations, vocational curricula should incorporate resilience development practices for women to navigate the hostile construction industry [47]. However, this is only a temporary solution to the adverse construction workplace. Eradicating hostile environment is the long-term solution to women’s survival in this sector.

According to Oo et al. [50], the sector’s culture is seen as one of the most significant hurdles to women’s participation in the construction sector. In the masculine culture, women find it difficult to integrate [42]. Throughout their career paths, women confront obstacles and gender bias [20]. The same rules around recruitment, career progression, and retention have different implications for female and male construction professionals, which suggests that discrimination and unfairness are apparent at every stage [49]. During the recruitment process, male candidates are given preference over female applicants [49]. Organisations and their leaders frequently fail to consider organisational culture and structural inequalities in the industry when implementing diversity initiatives, even though doing so would go a long way towards addressing the core causes of inequality and bringing about permanent change [44]. To address these cultural issues, Bridges et al. [31] argue that businesses should conduct workplace education programmes that focus on cultural change to promote harassment and bullying-free workplaces for women. Senior management professionals who are held accountable for the implementation of gender diversity initiatives must be familiar with the policies around gender equality and diversity, as they often lack this knowledge [46]. Leaders (senior managers, directors and CEOs) need to play a critical role in alleviating discriminatory practices from the construction workplace and promoting equitable employment practices [31,40]. Leaders must come forward to promote gender equality and communicate with all employees [39]. Not only is it instrumental to have sound and robust policies around gender equality, but they also must be authentically practised [5,31]. The actual practice is critical as the growing literature indicates that although formal well-being and other policies exist, they do little to address the informal rules in use. At times, informal rules take over formal policies and procedures. Therefore, companies need to reconsider informal rules and how formal rules can compete with informal ones [51]. However, to institutionalise the change, a robust and undivided vision is required across the organisation [39].

3.2.3. Career Opportunities and Available Roles (COAR)

In the construction sector, the shortage of transparent professional prospects has been one of the primary obstacles to women’s career advancement [20,37,42]. Challenges related to career development are some of the pressing concerns for female construction workers regardless of age, work experience, occupation and career level [7]. According to research, women are less likely than men to actively plan their careers, focusing more on surviving in their current job [40]. Men are afforded better possibilities for career advancement, such as working on and managing high-profile projects, while women must contend with prejudices and assumptions that they will quit the sector or scale down their employment to pursue motherhood [12,39].

Half of the people surveyed in a study by Baker and French [38] on gender bias and other structural barriers to career development in Australia’s project-based construction industry expressed scepticism about the openness, credibility, and fairness of internal appointments and promotions that seemed to be based on informal selection and gender bias. One respondent explained: “If you are a female … the only way you really progress is [if] someone older or more senior than you takes you under their wing and that person is typically a male. If you are a male … they seem to just progress much easier” [38] (p. 806). This suggests that women are often not considered for promotions [37,38]. Career progression is determined by previous success rates, while women are not provided with the opportunity to demonstrate their skills and abilities. Instead, men receive more chances to present their capabilities to leaders [49].

Previous research suggests that human capital factors such as working experiences in the number of organisations, development opportunities and relocations for career are the significant contributors to women career advancement in the construction industry [40]. Not only is gender discrimination a usual practice when it comes to awarding promotions, but recruitment practices also are male dominated to expand on “boys’ club’ which is relied on informal hiring practices [31]. Women are always re-quired to prove their capabilities whilst men are considered capable anyway [37]. This is a significant obstacle for women to grow professionally in this sector and this potentially leads to frustration and unwilling to stay in this profession. There is a lack of evidence that women’s overall job satisfaction has increased in recent years [50]. Furthermore, if equal opportunities and fairness are absent, female construction professionals demonstrate a lack of organisational commitment [18]. Lingard and Lin [18] suggested that the removal of women’s perception of discrimination practices and un-fair exchanges can contribute to female workers’ organisational commitments. This situation is exacerbated by the lack of organisation support to female workers [20]. It is unfortunate that “construction evidently does not, at present, give “permission” for women to lead or succeed” [40]. In addition, there is a lack of female construction professionals as a role model to seek guidance from [7,37] and absence of network for career progression [42]. Providing women with mentoring support may help achieve their both personal and career goals [54] as mentoring is associated with reduction in turnover and improved career satisfaction [55]. However, Francis [40] recently advocated that mentoring does not advance women’s career progression and instead prevents them from leaving the industry. Nonetheless, seeking support from other women in the profession and expanding the network would promote women’s empowerment in construction [5]. Although significant efforts are made in raising awareness about women’s participation in the construction sector and implementing gender equality legislation and policies, a distinguishable shift in demographics has yet to become noticeable [56]. To advance in career development in the construction industry, female construction workers can focus on capacity-building based on skills and knowledge [5]. Women construction professionals can only achieve their career goals and excel in the construction sector if systematic and structural obstacles are eradicated [20].

Turner et al. [47] argue that women are often denied professional advancement possibilities in addition to their skill sets being underutilised. For example, one of their research participants commented: “I have been looked over for higher roles, leadership roles, because I’m a girl and I’ve been openly told you were the best candidate for this position, but boys won’t … listen to you” [47] (p. 845).

3.2.4. Perception of Women’s Ability (POWA)

Women’s ability to perform the same job as their male counterparts is always questionable [7,20,37]. The construction industry is named as “men’s work” or a “masculine space” [49] (p. 1226). In a series of interviews conducted 24 years ago, Pringle and Winning [41] discovered that around one-fourth of tradespeople and builders believed that lack of strength and inability to operate equipment made some fields inappropriate for women. They made statements such as, “Women lack the intrinsic capacity to handle tools”, “They lack the men’s natural understanding of construction”, and “Women are not built to lift heavy materials”. Despite several initiatives and measures, this problem persists. While men are assumed to be competent in the construction industry, women’s professional ability is scrutinised, questioned, or discounted [47]. When a woman makes a mistake, it is called a problem with “female capacity” rather than her own incompetence [49]. Zhang et al. [20] state that males in the construction industry instinctively assume that women lack the necessary skills and abilities to execute their jobs. Therefore, women are often excluded from work-related conversation, social activities, and work meetings [20]. This mindset is at odds with the efforts of the business world as a whole to expand the number of women in the workforce. One of their research interviewees explained that: “Well, even in a meeting, most of the subcontractors prefer to talk with the men in the room rather than the ladies” [20] (p. 678). The situation is worse in small-to-medium and young organisations, in which female workers are given lesser priority [43]. Despite negative perceptions of women’s abilities, a positive correlation exists between gender diversity in the construction industry and increased organisational financial benefits [44]. More than three decades ago, Foley [57] indicated that the construction sector must promote bright and talented individuals, including women, to stay competitive. Otherwise, the sector is susceptible to facing high turnover, reduced performance, and increased organisational ineffectiveness [57].

4. Discussion

This study aims to lay the groundwork for a large-scale investigation evaluating the effectiveness of initiatives and policies that resolve the gender imbalance that hinders women’s retention in the Australian construction sector. The most significant impediments have been identified through the SLR on the variables and challenges affecting women’s careers and experiences in this Australian construction sector. The results reveal that women in the construction industry have been marginalised and have challenged several stereotypes and informal rules intrinsic to the profession.

4.1. Retention Strategies

Throughout the years, Australian state and federal governments have developed and implemented several initiatives and policies to tackle gender disparity in the construction industry, yet studies indicate that only minimal improvements have been accomplished. This suggests a potential study path to further analyse and evaluate these initiatives’ outcomes and implementation. A systemic viewpoint is necessary to identify the various variables/stakeholders/factors and their interrelationships to detect the leverage points [58,59] and archetypes within the system in order to design the most effective policies and initiatives that can make a real difference. Indeed, these approaches will aid in making the sector more appealing to and inclusive of women [46]. Several strategies and solutions, including bottom-up (mentoring, networking, alternative management structures, and supporting policies) and top-down approaches (leadership development programmes), have been identified in the literature (government initiatives, legislation and funding) [31,60]. As a result of analysing the themes identified in this study and conducting a thorough review of such solutions in the literature, the following solutions were formulated. It is important to emphasize that these areas are broad and interdependent and integral parts of a system:

4.1.1. Improving Work–Life Balance for Everyone

Most articles reviewed in this study identified institutionalised work practices, such as rigid and lengthy work hours, as the most significant barrier to women’s professional advancement in the construction industry and an important cause of leaving it. Long working hours are hazardous for both men and women, although women are often affected more severely [5]. Most women with families find balancing their careers and responsibilities challenging, especially when they return from maternity leave and find themselves without assistance [40]. For these women, trying to return to their prior project responsibilities part-time, the demands of full-time employment, and the absence of part-time work opportunities pose substantial obstacles [46]. Additionally, research indicates that an imbalance between work and life has contributed to marital unhappiness among Australian construction employees [18].

Changing the work pattern (solution to WHAF): Large government initiatives and organisational well-being efforts have been launched to combat the ubiquitous challenge of work–life balance in the construction industry [61]. The solution is not for women to work like men but rather to value women and men who deviate from the norm of working patterns that clash with family demands while maintaining full workloads. Additionally, the notion that higher-level roles need extended working hours must be scrutinised, and more efficient strategies for completing tasks must be developed. Although it may appear inefficient initially, rewarding and promoting the most productive employees, regardless of when they complete their tasks, can reduce costs in the long run [62].

Alternative work schedules (solution to WHAF): Research shows that the work–life balance of construction employees can be improved through alternative work schedules, such as work flexibility and compressed work weeks [61,63,64]. Such measures have been demonstrated to be beneficial in Australian workplaces if they are introduced in phases, enabling managers to engage in dialogue with workers to create a balanced strategy that is tailored to their workplace [37].

Technology (solution to WHAF): Several studies have suggested technology and work-from-home arrangements as potential solutions to alleviate the long hours of work and the “presenteeism” problems in the construction industry. However, research indicates that not everyone benefits equally from the option of working from home, and it differs depending on personal characteristics and family situations [65,66]. It may have varying impacts on those responsible for childcare or on the unique needs of women in the workplace during pregnancy or maternity leave. For instance, in the research of Panojan et al. [67], female participants regarded “increased time available to spend with friends and family” as one of the most effective solutions for poor work–life balance. On the other hand, the negative effects of this may be exacerbated by the growing usage of online communication, with some research participants in Pirzadeh and Lingard’s [66] study stating that they felt compelled to be always online. In addition, online communication was considered less effective for problem-solving than face-to-face conversations, intensifying the time constraints associated with project-based work [66]. Holden and Sunindijo [68] argue that in Australia, the use of technology to perform work at home has significant negative effects on work–life balance because it blurs the line between work and personal life. They state that even though workers may spend more time with friends and family in this arrangement, technology can become an impediment for the employees to separate work from personal life, casting a shadow over the improved flexibility and the opportunity to complete the tasks at home. In addition, spending more time at home might lead to increased domestic violence against women since it would provide the ideal environment for domestic abusers [69].

4.1.2. Changing the Gendered Culture and the Informal Rules

Effective policies, regulations, research (solution to GCIR and COAR): The outcomes of this research suggest that the gendered culture and informal rules have been among the highest-ranked complexities for women to establish their careers in the construction industry in Australia. Therefore, policymakers must provide more appropriate interventions to this macho culture, favouring males and disadvantaging women, minority groups, and men who do not precisely match the masculine stereotype [70]. This industry’s distinct toxic masculinity remains mostly uncontested and underexplored in construction management studies Chan [71]. Although governments and policymakers have attempted to make improvements, a culture of subtle denial and hostility to gender equality impairs the appropriate implementation of rules and regulations [5]. Based on earlier findings, tackling this issue should be the first focus for the sector to retain women. Improving this culture may also enhance men’s and women’s work–life balance and mental health.

One major finding of this research that aligns with the overarching goal of our larger project is the need to reshape the gendered informal norms and culture of the construction industry in Australia. Gender inequalities are often incorporated into formal and informal norms, making it more challenging to tackle them since they are difficult to detect and confront [72]. Policies that are strongly concentrated on increasing the number of women in construction but not on transforming the gender practises or culture of construction may seem inadequate to the majority of male workers, who arguably have the authority and the key to altering the industry’s culture. In addition, the policies tend to be low on the organization’s priority list, often being sacrificed in pursuit of other, more restrictive formal standards, such as construction contracts and safety protocols [11].

According to Galea et al. [49], efforts and policies addressing gender imbalance in construction must be robust and adaptable. Otherwise, the above-mentioned informal norms would impede the successful implementation of such initiatives, making it difficult for these policies to “’stick”. The findings of the SLR are consistent with their research, which implies that gendered norms and behaviours, such as long work hours, must be prioritised when establishing a gender equality policy. The historical experience with comparable difficulties and the presence of such informal regulations imply that more obligatory and focused actions are likely to be more successful [43]. Since the informal rules and practices impair women’s retention and progression [51], more research is required to identify projects and policies that can target the primary determinants and causes that will result in the most impactful improvements.

4.1.3. Facilitating Career Progression

Apart from the gendered culture and informal rules, the other significant obstacle for women to leave this profession is limited career prospects compared to males and a negative view of women’s abilities in some areas. Francis [40] found a positive and significant correlation between career advancement and women overall, indicating the less masculine the company, the more women advance. Therefore, to increase worker well-being, these informal, commonly accepted, and gendered regulations must be broken [51]. If this is not done, informal norms will likely continue undermining official regulations, such as government policies and efforts regarding gender disparity using public funds.

Organisational support, open discussions, and training (solution to GCIR, COAR, and POWA): Findings indicate that the literature highlights a pervasive absence of organisational support for women’s training and career progression in this sector [50,73]. Women are strongly encouraged to pursue construction-related courses in Australia (attraction policies), but once they join the field, they are reportedly offered less support and fewer opportunities (low retention rate) [20]. There is obviously a lack of training and career advancement opportunities, and the feeling of being in the boys’ club causes women to have a considerably smaller and weaker professional network, both of which are often vital to career progression [5].

The research suggests that one effective solution is for employers to foster an atmosphere where workers (in our case, females) openly discuss their needs and concerns. For instance, if the female employees contemplating maternity leave need a return-to-work plan, the plan should be discussed before the maternity leave and again before the return [37]. Another example would be to identify workplace hazards that are specific to women and minorities but are not often included in standard training sessions [74].

Promote females to positions of authority (solution to GCIR, COAR, and POWA): The appointment of more women in mentoring and leadership positions has also been advocated in the literature as a much-needed solution for this masculine culture. In certain instances, the research identifies these as the most effective methods for enhancing inclusion and career progression [31,75,76]. The provision of mentorship (also linked to Section 4.1.2) by female role models as change agents [77] would support women’s career progression and encourage them to stay in the profession. According to Menches and Abraham [60], mentorship greatly improves women’s retention at all construction industry levels. Women in higher positions of power may act as role models for younger women and provide inspiration which eventually helps the sector achieve gender balance [31,39]. However, this mentoring and inspiration need not come only from female co-workers. According to studies, the assistance of male instructors and supervisors is also highly influential, and many women feel optimistic when they receive encouragement and support from fellow male employees [31,76,78]. In addition to mentoring, providing women with career development opportunities and organisational support may significantly contribute to their retention and professional advancement [40]. There are just a few robust research studies on how mentoring programs can be enabled and implemented via official regulations in the construction sector, where time and resources are crucial to the successful completion of projects.

5. Conclusions

Using an SLR method, this research examined the “wicked problem” of gender diversity in the Australian construction sector and distilled the results into four major themes. Six solutions within their overarching objectives targeting the major issues were also found by undertaking a thorough review of the Australian and global literature. In the context of gender diversity in Australia’s construction sector, a few studies reviewed in this SLR have examined the same issue. However, there are significant differences in perspectives, how the problem has been evaluated, and the conclusions that have been formed. For instance, Wang et al.’s [5] research emphasises enhancing women’s interpersonal abilities via empowerment to advance their careers in the construction sector. Their primary findings focus on strengthening resilience, gaining knowledge, obtaining support, and expanding professional networks. While the environmental component of the problem has also been explored briefly, the authors suggest that new techniques to promote women’s empowerment in construction may be developed at the intersection of this aspect with the other relational and personal dimensions. In the current study, however, our major interest at this point of the project revolves around the gendered environment and informal norms that have substantially influenced women’s careers. Notably, the data will be utilised in future project stages to empirically study these characteristics in order to formulate effective policies and initiatives. The primary distinction between our study and the research of [7]. is, firstly, their mixed-method research design as opposed to our SLR. Secondly, their research was conducted six years ago, and the industry and Australian society have undergone significant transformations, particularly since the pandemic began in 2020. As mentioned before, a similar technique (quantitative and qualitative) may be used in the future to continue this research; however, a more comprehensive SLR (compared to [7]) has been conducted in this study to understand the system more thoroughly. Similarly, Carnemolla and Galea [10] have researched the gendered construction industry in Australia. Their study significantly differs from ours because (1) they use a mixed strategy and because (2) they concentrate on female students and why women do not establish a career in this area. Nevertheless, similar to [20], their findings served as a tremendous source of inspiration for us to undertake the present study. As mentioned previously, we believe that while initiatives on attracting female students to pursue a degree in construction must be implemented, improving the industry’s gender norms will eventually pave the way for more women to establish a career in this sector, thereby improving the industry’s image and leading to more women choosing this profession as a career.

Retaining women in the workforce through improving the environment and policies in the construction industry is a topic that has received minimal attention from researchers in Australia. Consequently, more comprehensive studies are required to provide governments and policymakers with the input they need to design more effective initiatives. Instead of concentrating primarily on attraction, we believe that women will remain in the sector if the work environment is improved by addressing the gendered informal norms to create a more favourable workplace for the current female employees. This will enhance the sector’s reputation and improves its image, resulting in more female graduates pursuing careers in construction. This requires academics and policymakers to employ systems thinking approach to identify the system’s characteristics, causal interconnections, and leverage points to establish a framework that would assist in developing more effective strategies and initiatives. Any such framework can help measure the effectiveness and success of such efforts and have a lasting impact. This will enhance the well-being of all employees [11] and benefit the whole industry.

Future Research

This SLR reveals that only 23 high-quality research studies have addressed the underrepresentation of women in the Australian construction sector during the past decades. In addition, a significant number of these publications have focused mainly on women and how they can/must cope with the existing situation by being “tough”. However, this research adds to the conversation about the factors impacting the retention rate of women in the construction industry and the need for more effective strategies to improve it by enhancing the industry’s workplace culture and informal norms. It acts as a stepping stone for the next section of our project, which seeks to offer a framework for policymakers to design and assess more effective initiatives.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.N.G.; methodology, A.N.G., R.J.T., R.Y.S., C.H., N.T., and T.L.; software, R.J.T.; formal analysis, R.J.T., W.Z., P.Y., R.N.C. and M.H.; investigation, all authors; resources, R.J.T., W.Z., P.Y. and R.N.C.; data curation, R.J.T., W.Z., P.Y. and R.N.C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.N.G. and R.J.T.; writing—review and editing, A.N.G., R.J.T., R.Y.S., C.H., N.T. and T.L.; visualization, R.J.T.; supervision, A.N.G.; project administration, A.N.G.; funding acquisition, A.N.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Some parts of this research was funded by the Faculty of Society and Design, Bond University, grant number ‘RR-BD12’ and “The APC was funded by The 45th Australasian Universities Building Education Association (AUBEA) conference”.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Turner, M.; Zhang, R.P.; Holdsworth, S.; Myla, M. Taking a broader approach to women’s retention in construction: Incorporating the university domain. In Proceedings of the 37th Annual Association of Researchers in Construction Management Conference (ARCOM 2021), Leeds, UK, 6–7 September 2021; pp. 188–197. [Google Scholar]

- Norberg, C.; Johansson, M. “Women and “Ideal” Women”: The Representation of Women in the Construction Industry. Gend Issues 2020, 38, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Women in Construction 2022; PlanRadar: Vienna, Austria, 2022; Available online: https://www.planradar.com/gb/women-in-construction/ (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Australian Industry and Skills Committee (AISC). National Industry Insights Report; Australian Industry and Skills Committee (AISC): Canberra, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.C.; Mussi, E.; Sunindijo, R.Y. Analysing Gender Issues in the Australian Construction Industry through the Lens of Empowerment. Buildings 2021, 11, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DEPW. Women in Construction; Department of Energy and Public Works: Canberra, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rosa, J.E.; Hon, C.K.; Xia, B.; Lamari, F. Challenges, success factors, and strategies for women’s career development in the Australian construction industry. Constr. Econ. Build. 2017, 17, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACA. Market Sentiment Report; Australian Constructors Association: Sydney, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Oo, B.L.; Liu, X.; Lim, B.T.H. The experiences of tradeswomen in the Australian construction industry. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2022, 22, 1408–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnemolla, P.; Galea, N. Why Australian female high school students do not choose construction as a career: A qualitative investigation into value beliefs about the construction industry. J. Eng. Educ. 2021, 110, 819–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galea, N.; Powell, A.; Loosemore, M.; Chappell, L. Designing robust and revisable policies for gender equality: Lessons from the Australian construction industry. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2015, 33, 375–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, K.; Powell, A. Equality, diversity, inclusion and work–life balance in construction. In Human Resource Management in Construction; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2013; pp. 187–220. [Google Scholar]

- Hegarty, T.A. The Glass Scaffold: Women in Construction Responding to Industry Conditions; University of Canterbury: Christchurch, New Zealand, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Perrenoud, A.J.; Bigelow, B.F.; Perkins, E.M. Advancing Women in Construction: Gender Differences in Attraction and Retention Factors with Managers in the Electrical Construction Industry. J. Manag. Eng. 2020, 36, 04020043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çınar, S. Construction labour, subcontracting and masculinity: “Construction is a man’s job”. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2020, 38, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regis, M.F.; Alberte, E.P.V.; Lima, D.d.S.; Freitas, R.L.S. Women in construction: Shortcomings, difficulties, and good practices. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2019, 26, 2535–2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickey, P.J.; Cui, Q. Gender Diversity in US Construction Industry Leaders. J. Manag. Eng. 2020, 36, 04020069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingard, H.; Lin, J. Career, family and work environment determinants of organizational commitment among women in the Australian construction industry. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2004, 22, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loosemore, M.; Galea, N. Genderlect and conflict in the Australian construction industry. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2008, 26, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.P.; Holdsworth, S.; Turner, M.; Andamon, M.M. Does gender really matter? A closer look at early career women in construction. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2021, 39, 669–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.; Harden, A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2008, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotimi, F.E.; Burfoot, M.; Naismith, N.; Mohaghegh, M.; Brauner, M. A systematic review of the mental health of women in construction: Future research directions. Build. Res. Inf. Int. J. Res. Dev. Demonstr. 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schön, E.; Thomaschewski, J.; Escalona, M.J. Agile Requirements Engineering: A systematic literature review. Comput. Stand. Interfaces 2017, 49, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisch, C.; Block, J. Six tips for your (systematic) literature review in business and management research. Manag. Rev. Q. 2018, 68, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charrois, T.L. Systematic Reviews: What Do You Need to Know to Get Started? Can. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2015, 68, 144–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNair, R.P.; Parkinson, S.; Dempsey, D.; Andrews, C. Lesbian, gay and bisexual homelessness in Australia: Risk and resilience factors to consider in policy and practice. Health Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, e687–e694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, A.; Bourne, A.; McNair, R.; Carman, M.; Lyons, A. Private Lives 3: The Health and Well-being of LGBTIQ People in Australia; La Trobe University: Bundoora, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, E.; Qian-Khoo, J.; Campain, R.; Brown, C.; Kelly, J.; Kamstra, P. Overview of Results: Informing Investment Design, ILC Research Activity; Centre for Social Impact, Swinburne University of Technology: Hawthorn, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Field, R.; Dam, M.; McCaskill, C.; Dimitrijevic, S. Submission to the Parliamentary Inquiry into Family, Domestic and Sexual Violence; Domestic Violence: Sydney, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bridges, D.; Wulff, E.; Bamberry, L.; Krivokapic-Skoko, B.; Jenkins, S. Negotiating gender in the male-dominated skilled trades: A systematic literature review. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2020, 38, 894–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkonen, A.; Alin, P. Practice-based learning in construction projects: A literature review. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2015, 33, 513–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, U.H.; Ahmad, M.N.; Zakaria, A.M.U. Ontologies application in the sharing economy domain: A systematic review. Online Inf. Rev. 2022, 46, 807–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchenham, B.; Pretorius, R.; Budgen, D.; Pearl Brereton, O.; Turner, M.; Niazi, M.; Linkman, S. Systematic literature reviews in software engineering—A tertiary study. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2010, 52, 792–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldana, J.; Leavy, P.; Beretvas, N. Fundamentals of Qualitative Research; Oxford University Press, Incorporated: Cary, NC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wijewickrama, M.K.C.S.; Rameezdeen, R.; Chileshe, N. Information brokerage for circular economy in the construction industry: A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 313, 127938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryce, T.; Far, H.; Gardner, A. Barriers to career advancement for female engineers in Australia’s civil construction industry and recommended solutions. Aust. J. Civ. Eng. 2019, 17, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.; French, E. Female underrepresentation in project-based organizations exposes organizational isomorphism. Equal. Divers. Incl. Int. J. 2018, 37, 799–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salignac, F.; Galea, N.; Powell, A. Institutional entrepreneurs driving change: The case of gender equality in the Australian construction industry. Aust. J. Manag. 2018, 43, 152–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, V. What influences professional women’s career advancement in construction? Constr. Manag. Econ. 2017, 35, 254–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pringle, R.; Winning, A. Building Strategies: Equal Opportunity in the Construction Industry. Gend. Work Organ. 1998, 5, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oo, B.L.; Feng, X.; Teck-Heng Lim, B. Early career women in construction: Career choice and barriers. IOP Conf. Series. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 601, 12021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loosemore, M.; Alkilani, S.; Mathenge, R. The risks of and barriers to social procurement in construction: A supply chain perspective. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2020, 38, 552–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.; Ali, M.; French, E. Leadership Diversity and Its Influence on Equality Initiatives and Performance: Insights for Construction Management. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2021, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oo, B.L.; Lim, B.T.H. Changes in Job Situations for Women Workforce in Construction during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Constr. Econ. Build. 2021, 21, 34–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.; French, E.; Ali, M. Insights into Ineffectiveness of Gender Equality and Diversity Initiatives in Project-Based Organizations. J. Manag. Eng. 2021, 37, 04021013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.; Holdsworth, S.; Scott-Young, C.M.; Sandri, K. Resilience in a hostile workplace: The experience of women onsite in construction. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2021, 39, 839–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, B.A.K.S.; Ridmika, K.I.; Wijewickrama, M.K.C.S. Life management of the quantity surveyors working for contractors at sites: Female vs male. Constr. Innov. 2022, 22, 962–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galea, N.; Powell, A.; Loosemore, M.; Chappell, L. The gendered dimensions of informal institutions in the Australian construction industry. Gend. Work Organ. 2020, 27, 1214–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oo, B.L.; Lim, B.; Feng, S. Early career women in construction: Are their career expectations being met? Constr. Econ. Build. 2020, 20, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galea, N.; Powell, A.; Salignac, F.; Chappell, L.; Loosemore, M. When Following the Rules Is Bad for Well-being: The Effects of Gendered Rules in the Australian Construction Industry. Work Employ. Soc. 2022, 36, 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappell, L. Comparing Political Institutions: Revealing the Gendered “Logic of Appropriateness”. Politics Gend. 2006, 2, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Y.J.; Ho, M.R.; Wang, S.; Miller, I.S.K. Meta-Analyses of the Relationship Between Conformity to Masculine Norms and Mental Health-Related Outcomes. J. Couns. Psychol. 2017, 64, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noe, R.A. Women and Mentoring: A Review and Research Agenda. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1988, 13, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake-Beard, S.D. Taking a Hard Look at Formal Mentoring Programs: A Consideration of the Potential Challenges Facing Women. J. Manag. Dev. 2001, 20, 331–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, E.; Strachan, G. Women at work! Evaluating equal employment policies and outcomes in construction. Equal. Divers. Incl. Int. J. 2015, 34, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, D.A. Human-Resource Management for Twenty-First Century: Managing Diversity. J. Prof. Issues Eng. Educ. Pract. 1994, 120, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadows, D.H. Places to Intervene in a System; The Sustainability Institute: Hartland, VT, USA, 1997; Available online: http://www.donellameadows.org/wp-content/userfiles/Leverage_Points.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2022).

- Zhang, Q.; Prouty, C.; Zimmerman, J.B.; Mihelcic, J.R. More than Target 6.3: A Systems Approach to Rethinking Sustainable Development Goals in a Resource-Scarce World. Engineering 2016, 2, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menches, C.L.; Abraham, D.M. Women in construction—Tapping the untapped resource to meet future demands. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2007, 133, 701–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tijani, B.; Osei-Kyei, R.; Feng, Y. A review of work-life balance in the construction industry. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2022, 22, 2671–2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, S.; Humbert, A.L. Discourse or reality? “Work-life balance”, flexible working policies and the gendered organization. Equal. Divers. Incl. Int. J. 2010, 29, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, V.; Lingard, H.; Prosser, A.; Turner, M. Work-Family and Construction: Public and Private Sector Differences. J. Manag. Eng. 2013, 29, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, S.J. Work-life balance in the Australian and New Zealand surveying profession. Struct. Surv. 2008, 26, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delanoeije, J.; Verbruggen, M. Between-person and within-person effects of telework: A quasi-field experiment. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2020, 29, 795–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirzadeh, P.; Lingard, H. Working from Home during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Health and Well-Being of Project-Based Construction Workers. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2021, 147, 04021048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panojan, P.; Perera, B.A.K.S.; Dilakshan, R. Work-life balance of professional quantity surveyors engaged in the construction industry. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2022, 22, 751–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, S.; Sunindijo, R.Y. Technology, Long Work Hours, and Stress Worsen Work-life Balance in the Construction Industry. Int. J. Integr. Eng. 2018, 10, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanrahan, C.; Cornish, R. Domestic Violence Escalated as COVID-19 Pandemic Created ‘Perfect Conditions’ for Abusers. 2022. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-01-21/covid-19-pandemic-was-perfect-conditions-for-domestic-violence/100770418 (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- George, M.; Loosemore, M. Site operatives’ attitudes towards traditional masculinity ideology in the Australian construction industry. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2019, 37, 419–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, P.W. Queer eye on a ‘straight’ life: Deconstructing masculinities in construction. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2013, 31, 816–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappell, L.; Waylen, G. Gender and the hidden life of institutions. Public Adm. 2013, 91, 599–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galea, N.; Rogan; Powell, A.; Loosemore, M.; Chappell, L. Demolishing Gender Structures. 2018. Available online: https://www.humanrights.unsw.edu.au/sites/default/files/documents/Construction_Report_Final.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2023).

- Pamidimukkala, A.; Kermanshachi, S. Assessment of Effectiveness of Occupational Hazards Training for Women in the Construction Industry. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Transportation and Development 2022, Seattle, WA, USA, 31 May–3 June 2022; pp. 270–279. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, A.; Hamm, Z.; Raykov, M. The experiences of female youth apprentices in Canada: Just passing through? J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2015, 67, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, T. Women’s Experience of Workplace Interactions in Male-Dominated Work: The Intersections of Gender, Sexuality and Occupational Group. Gend. Work Organ. 2016, 23, 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, L.; Clarke, K. Apprenticeships should work for women too. Educ. Train. 2016, 58, 578–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIsaac, K.M.; Domene, J.F. Learning the tricks of the trades: Women’s experiences. Can. J. Couns. Psychother. 2014, 48, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).