Green Home Buying Intention of Malaysian Millennials: An Extension of Theory of Planned Behaviour

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1: What are the predictors of green home buying intention for Millennial consumers?

- RQ2: To what extent does the extended TPB validate green home buying in the Malaysian context?

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Green Homes

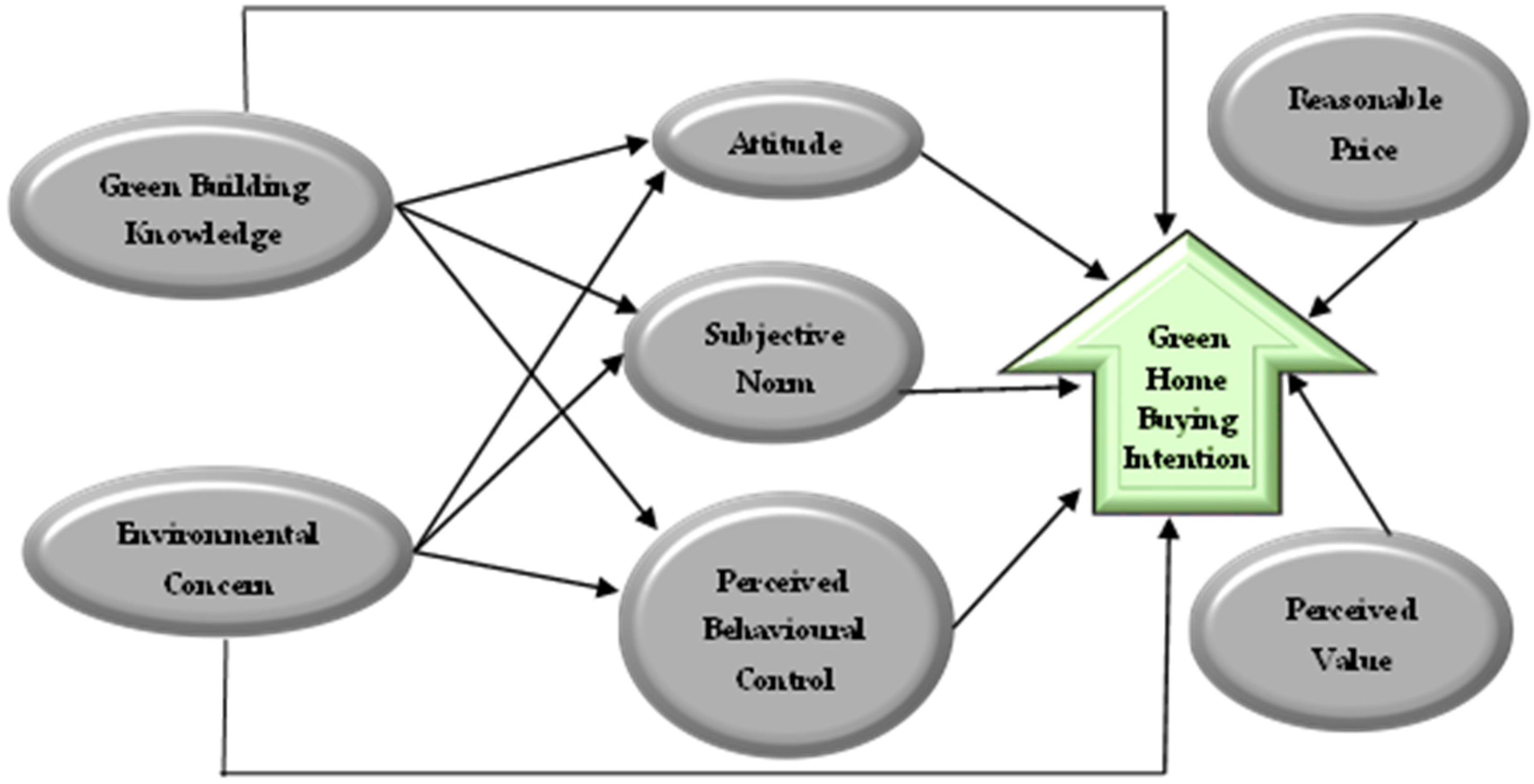

2.2. The Component of the Extended TPB Model

2.3. Attitude

2.4. Subjective Norm (SN)

2.5. Perceived Behavioural Control (PBC)

2.6. Environmental Concern (EC)

2.7. Green Building Knowledge (GBK)

2.8. Perceived Value (PV)

2.9. Reasonable Price (RP)

3. Research Design

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Measures and Common Method Bias

3.3. Data Analysis Methods

4. Analysis of Outcomes

4.1. Assessment of Construct Validity and Discriminant Validity

4.2. Reliability

4.3. Normality and Multicollinearity

4.4. Coefficient of Determination

4.5. Path Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Predictors of Green Home Buying Intention

5.2. Environmental Concern and Its Impact on TPB Constructs

5.3. Green Building Knowledge and Its Impact on TPB Constructs

6. Implication of the Study

7. Conclusions, Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Survey Questionnaire

| Strongly Disagree | Strongly Agree | |||||

| 1. Attitude |  | |||||

| Green homes will help to save the environment because it uses environmentally friendly materials and processes | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Buying a green home that has Green Building Index (GBI) ratings or similar international ratings is favourable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Living in a green home would be good for me because these homes improve our quality of living | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 2. Subjective Norm | ||||||

| My family think that I should purchase a green home rather than a normal home | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| My close friends think that I should buy a green home | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| People who influence my behaviour think that I should purchase a green home. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 3. Perceived behavioural control | ||||||

| I am confident that I would purchase a green home even if it is slightly more expensive | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| I am confident that I would purchase a green home even if the other person advises me the opposite | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| I am sure I would be able to make difference to use PV solar energy | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Buying a green home is entirely within my control | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| I have the resources, and ability to purchase green homes. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 4. Reasonable Price | ||||||

| I would buy a green home if the price is reasonable. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| The price of green homes is normally higher than that of conventional homes. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| It is easy to justify the price and benefits of green homes. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 5. Environmental Concerns | ||||||

| I prefer to check the Green Building Index (GBI) or other green ratings and certifications on the homes before purchase. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| I want to have a deeper insight into the inputs, processes and impacts of the green home on the environment before the purchase. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| I would prefer to gain substantial information on green homes before purchasing. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 6. Green Building Knowledge | ||||||

| I know factual information about eco-home design (e.g., building codes, wind turbines, recycled content materials, and dual-flush toilets etc.). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| I have the conceptual knowledge of green building design (e.g., how to maintain indoor air quality, size and window locations, ecological impacts etc.) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| I have procedural knowledge of green building operations (e.g., picking eco-friendly furniture, monitoring cooling systems or solar panels or using water-saving building fixtures). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 7. Perceived Value | ||||||

| Green home’s environmental functions provide very good value for me | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Green home’s environmental performance meets my expectations | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Buying a green home has more environmental benefits than other conventional homes | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 8. Purchase Intention | ||||||

| I am planning to buy a green home in future | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| I will try to purchase a green and sustainable home in future | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| I will make an effort to purchase a green and sustainable home in future | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| I intend to purchase green homes next time because of their positive environmental contribution | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| I will consider switching to a green home for ecological reasons | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

References

- Paul, J.; Modi, A.; Patel, J. Predicting Green Product Consumption Using Theory of Planned Behavior and Reasoned Action. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 29, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maichum, K.; Parichatnon, S.; Peng, K.-C. Application of the Extended Theory of Planned Behavior Model to Investigate Purchase Intention of Green Products among Thai Consumers. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Young Consumers’ Intention towards Buying Green Products in a Developing Nation: Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, L.; Wu, Z.; Xue, H.; Dong, W. Key Factors Affecting Informed Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Green Housing: A Case Study of Jinan, China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briefing, U.S. International Energy Outlook 2013. US Energy Inf. Adm. 2013, 506, 507. [Google Scholar]

- Darko, A.; Zhang, C.; Chan, A.P.C. Drivers for Green Building: A Review of Empirical Studies. Habitat Int. 2017, 60, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.H. Use of Structural Equation Modeling to Predict the Intention to Purchase Green and Sustainable Homes in Malaysia. Asian Soc. Sci. 2013, 9, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, P.-N.; Chawla, S.; Ho, C.K.; Bailey, J. Advances in Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Part II, Proceedings of the 16th Pacific-Asia Conference, PAKDD 2012, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 29 May–1 June 2012; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 7302, ISBN 3642302203. [Google Scholar]

- Young, W.; Hwang, K.; McDonald, S.; Oates, C.J. Sustainable Consumption: Green Consumer Behaviour When Purchasing Products. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiederhold, M.; Martinez, L.F. Ethical Consumer Behaviour in Germany: The Attitude-behaviour Gap in the Green Apparel Industry. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2018, 42, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Siddik, A.B.; Masukujjaman, M.; Wei, X. Bridging Green Gaps: The Buying Intention of Energy Efficient Home Appliances and Moderation of Green Self-Identity. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, M.; Warren-Myers, G.; Paladino, A. Using the Theory of Planned Behaviour to Predict Intentions to Purchase Sustainable Housing. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carfora, V.; Caso, D.; Sparks, P.; Conner, M. Moderating Effects of Pro-Environmental Self-Identity on pro-Environmental Intentions and Behaviour: A Multi-Behaviour Study. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 53, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, V.K.; Chandra, B. An Application of Theory of Planned Behavior to Predict Young Indian Consumers’ Green Hotel Visit Intention. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 1152–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdanpanah, M.; Forouzani, M. Application of the Theory of Planned Behaviour to Predict Iranian Students’ Intention to Purchase Organic Food. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 107, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshebami, A.S. Evaluating the Relevance of Green Banking Practices on Saudi Banks’ Green Image: The Mediating Effect of Employees’ Green Behaviour. J. Bank. Regul. 2021, 22, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novitasari, M.; Alshebami, A.S.; Sudrajat, M.A. The Role of Green Supply Chain Management in Predicting Indonesian Firms’ Performance: Competitive Advantage and Board Size Influence. Indones. J. Sustain. Account. Manag. 2021, 5, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.-W.; Siddik, A.B.; Masukujjaman, M.; Alam, S.S.; Akter, A. Perceived Environmental Responsibilities and Green Buying Behavior: The Mediating Effect of Attitude. Sustainability 2020, 13, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Siddik, A.B.; Zheng, G.-W.; Masukujjaman, M.; Bekhzod, S. The Effect of Green Banking Practices on Banks’ Environmental Performance and Green Financing: An Empirical Study. Energies 2022, 15, 1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.-W.; Siddik, A.B.; Masukujjaman, M.; Fatema, N. Factors Affecting the Sustainability Performance of Financial Institutions in Bangladesh: The Role of Green Finance. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kota, B.R.; Debs, L.; Davis, T. Exploring Generation Z’s Perceptions of Green Homes. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Liang, S.; Wu, W.; Hong, Y. Practicing Green Residence Business Model Based on TPB Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, L.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Song, H. Investigating Young Consumers’ Purchasing Intention of Green Housing in China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Chen, L. Exploring Residents’ Purchase Intention of Green Housings in China: An Extended Perspective of Perceived Value. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahan, I.; Chuanmin, S.; Fayyaz, M.; Hafeez, M. Green Purchase Behavior towards Green Housing: An Investigation of Bangladeshi Consumers. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 38745–38757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Zhao, T.; Xing, Z. How Do Government Policies Promote Green Housing Diffusion in China? A Complex Network Game Context. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosner, Y.; Amitay, Z.; Perlman, A. Consumer’s Attitude, Socio-Demographic Variables and Willingness to Purchase Green Housing in Israel. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 5295–5316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Yu, S.; Han, Q.; de Vries, B. How to Attract Customers to Buy Green Housing? Their Heterogeneous Willingness to Pay for Different Attributes. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 230, 709–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalejska-Jonsson, A. Stated WTP and Rational WTP: Willingness to Pay for Green Apartments in Sweden. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2014, 13, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.-L.; Goh, Y.-N. The Role of Psychological Factors in Influencing Consumer Purchase Intention towards Green Residential Building. Int. J. Hous. Mark. Anal. 2018, 11, 788–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yau, Y. Eco-labels and Willingness-to-pay: A Hong Kong Study. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2012, 1, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Geertman, S.; Hooimeijer, P. The Willingness to Pay for Green Apartments: The Case of Nanjing, China. Urban Stud. 2014, 51, 3459–3478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.L.; Rahim, S.A.; Pawanteh, L.; Ahmad, F. The Understanding of Environmental Citizenship among Malaysian Youths: A Study on Perception and Participation. Asian Soc. Sci. 2012, 8, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jia, J.; Wu, H.-Q.; Nie, H.-G.; Fan, Y. Modeling the Willingness to Pay for Energy Efficient Residence in Urban Residential Sector in China. Energy Policy 2019, 135, 111003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hong, Z.; Zhu, J.; Yan, J.; Qi, J.; Liu, P. Promoting Green Residential Buildings: Residents’ Environmental Attitude, Subjective Knowledge, and Social Trust Matter. Energy Policy 2018, 112, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauge, Å.L.; Thomsen, J.; Löfström, E. How to Get Residents/Owners in Housing Cooperatives to Agree on Sustainable Renovation. Energy Effic. 2013, 6, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Allen, A.; Kim, B. Interior Design Practitioner Motivations for Specifying Sustainable Materials: Applying the Theory of Planned Behavior to Residential Design. J. Inter. Des. 2013, 38, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Geng, G.; Sun, P. Determinants and Implications of Citizens’ Environmental Complaint in China: Integrating Theory of Planned Behavior and Norm Activation Model. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 166, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hyun, S.S. Drivers of Customer Decision to Visit an Environmentally Responsible Museum: Merging the Theory of Planned Behavior and Norm Activation Theory. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 34, 1155–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.S.; Nik Hashim, N.H.; Rashid, M.; Omar, N.A.; Ahsan, N.; Ismail, M.D. Small-Scale Households Renewable Energy Usage Intention: Theoretical Development and Empirical Settings. Renew. Energy 2014, 68, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eze, U.C.; Ndubisi, N.O. Green Buyer Behavior: Evidence from Asia Consumers. J. Asian Afr. Stud. 2013, 48, 413–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimy, M.; Zareban, I.; Araban, M.; Montazeri, A. An Extended Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) Used to Predict Smoking Behavior among a Sample of Iranian Medical Students. Int. J. High Risk Behav. Addict. 2015, 4, e24715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karatu, V.M.H.; Mat, N.K.N. The Mediating Effects of Green Trust and Perceived Behavioral Control on the Direct Determinants of Intention to Purchase Green Products in Nigeria. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, R.D.; Soebarto, V.; Zhao, Z.Y.; Zillante, G. Facilitating the Transition to Sustainable Construction: China’s Policies. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 131, 534–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofek, S.; Akron, S.; Portnov, B.A. Stimulating Green Construction by Influencing the Decision-Making of Main Players. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 40, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Long, R.; Chen, H. Differences and Influencing Factors for Chinese Urban Resident Willingness to Pay for Green Housings: Evidence from Five First-Tier Cities in China. Appl. Energy 2018, 229, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabay, H.; Meir, I.A.; Schwartz, M.; Werzberger, E. Cost-Benefit Analysis of Green Buildings: An Israeli Office Buildings Case Study. Energy Build. 2014, 76, 558–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.K. Green Supply-chain Management: A State-of-the-art Literature Review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2007, 9, 53–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. From Intentions to Actions: A Theory of Planned Behavior BT. In Action Control: From Cognition to Behavior; Kuhl, J., Beckmann, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 11–39. ISBN 978-3-642-69746-3. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behaviour; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Liere, K.D.V.; Dunlap, R.E. The Social Bases of Environmental Concern: A Review of Hypotheses, Explanations and Empirical Evidence. Public Opin. Q. 1980, 44, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taufique, K.M.R.; Vaithianathan, S. A Fresh Look at Understanding Green Consumer Behavior among Young Urban Indian Consumers through the Lens of Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 183, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hume, M. Compassion without Action: Examining the Young Consumers Consumption and Attitude to Sustainable Consumption. J. World Bus. 2010, 45, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, C.K.; Lauricella, A.R.; Wartella, E.; Robb, M.; Schomburg, R. Adoption and Use of Technology in Early Education: The Interplay of Extrinsic Barriers and Teacher Attitudes. Comput. Educ. 2013, 69, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Attitudes, Personality, and Behavior, 6th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: London, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Ramayah, T.; Rahbar, E. Greening the Environment through Recycling: An Empirical Study. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2013, 24, 782–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.F.; Tung, P.J. Developing an Extended Theory of Planned Behavior Model to Predict Consumers’ Intention to Visit Green Hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 36, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Yoon, H.J. Hotel Customers’ Environmentally Responsible Behavioral Intention: Impact of Key Constructs on Decision in Green Consumerism. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 45, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Driver, B.L. Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior to Leisure Choice. J. Leis. Res. 1992, 24, 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Wong, N.; Abe, S.; Bergami, M. Cultural and Situational Contingencies and the Theory of Reasoned Action: Application to Fast Food Restaurant Consumption. J. Consum. Psychol. 2000, 9, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irianto, H. Consumers’ Attitude and Intention towards Organic Food Purchase: An Extension of Theory of Planned Behavior in Gender Perspective. Int. J. Manag. Econ. Soc. Sci. 2015, 4, 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, A.; Hsu, C.H.C.; Baum, T. The Impact of Tour Service Performance on Tourist Satisfaction and Behavioral Intentions: A Study of Chinese Tourists in Hong Kong. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2015, 32, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramayah, T.; Lee, J.W.C.; Lim, S. Sustaining the Environment through Recycling: An Empirical Study. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 102, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Huang, G.; Yin, X.; Gong, Q. Residents’ Waste Separation Behaviors at the Source: Using SEM with the Theory of Planned Behavior in Guangzhou, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 9475–9491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, A.; Vieira, L.M.; de Barcellos, M.D. Consumer Behaviour towards Organic Food in Porto Alegre: An Application of the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Rev. Econ. Sociol. Rural 2013, 51, 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosby, L.A.; Gill, J.D.; Taylor, J.R. Consumer/Voter Behavior in the Passage of the Michigan Container Law. J. Mark. 1981, 45, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, D.; Kant, R. Green Purchasing Behaviour: A Conceptual Framework and Empirical Investigation of Indian Consumers. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 41, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Determinants of Consumers’ Green Purchase Behavior in a Developing Nation: Applying and Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 134, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark, N.; Law, M. Encouraging Green Purchase Behaviours of Hong Kong Consumers. Asian J. Bus. Res. ISSN 2015, 5, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sang, Y.-N.; Bekhet, H.A. Modelling Electric Vehicle Usage Intentions: An Empirical Study in Malaysia. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 92, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basha, M.B.; Mason, C.; Shamsudin, M.F.; Hussain, H.I.; Salem, M.A. Consumers Attitude towards Organic Food. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 31, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatu, V.M.H.; Nik Mat, N.K. Determinants of Green Purchase Intention in Nigeria: The Mediating Role of Green Perceived Value. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Accounting Studies (ICAS) 2015, Johor, Malaysia, 17–20 August 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Suki, N.M. Consumer Environmental Concern and Green Product Purchase in Malaysia: Structural Effects of Consumption Values. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 132, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.J. The Effects of Message Framing on Response to Environmental Communications. J. Mass Commun. Q. 1995, 72, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, L.B. Green Building Literacy: A Framework for Advancing Green Building Education. Int. J. STEM Educ. 2019, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.W.; Akter, N.; Siddik, A.B.; Masukujjaman, M. Organic Foods Purchase Behavior among Generation y of Bangladesh: The Moderation Effect of Trust and Price Consciousness. Foods 2021, 10, 2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moorman, C.; Diehl, K.; Brinberg, D.; Kidwell, B. Subjective Knowledge, Search Locations, and Consumer Choice. J. Consum. Res. 2004, 31, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.J.; Kahlor, L. What, Me Worry? The Role of Affect in Information Seeking and Avoidance. Sci. Commun. 2013, 35, 189–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.-C. An Empirical Study of the Effects of Service Quality, Perceived Value, Corporate Image, and Customer Satisfaction on Behavioral Intentions in the Taiwan Quick Service Restaurant Industry. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2013, 14, 364–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-L.; Lin, J.C.-C. What Drives Purchase Intention for Paid Mobile Apps?—An Expectation Confirmation Model with Perceived Value. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2015, 14, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponte, E.B.; Carvajal-Trujillo, E.; Escobar-Rodríguez, T. Influence of Trust and Perceived Value on the Intention to Purchase Travel Online: Integrating the Effects of Assurance on Trust Antecedents. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 286–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H. Enhance Green Purchase Intentions: The Roles of Green Perceived Value, Green Perceived Risk, and Green Trust. Manag. Decis. 2012, 50, 502–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Lobo, A. Organic Food Products in China: Determinants of Consumers’ Purchase Intentions. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2012, 22, 293–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Jin, S.; Zhu, H.; Qi, X. Construction of Revised TPB Model of Customer Green Be-Havior: Environmental Protection Purpose and Ecological Values Perspectives. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Barcelona, Spain, 11–13 March 2018; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2018; Volume 167, p. 12021. [Google Scholar]

- Salehzadeh, R.; Pool, J.K. Brand Attitude and Perceived Value and Purchase Intention toward Global Luxury Brands. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2017, 29, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, W.; Zhang, Q. Green Purchase Intention: Effects of Electronic Service Quality and Customer Green Psychology. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 267, 122053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Zhao, X.; Liu, Y.; Yang, X. Measuring Purchase Intention towards Green Power Certificate in a Developing Nation: Applying and Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 168, 105363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Siddik, A.B.; Masukujjaman, M.; Hamayun, M.; Ibrahim, A.M. Bi-Dimensional Values and Attitudes Toward Online Fast Food-Buying Intention During the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Application of VAB Model. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonini, S.; Oppenheim, J. Cultivating the Green Consumer. Stanford Soc. Innov. Rev. 2008, 6, 56–61. [Google Scholar]

- Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection. Barrier/Motivation Inventory No. 3. 2003. Available online: http://www.state.ma.us (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- Ottman, J.A.; Stafford, E.R.; Hartman, C.L. Avoiding Green Marketing Myopia: Ways to Improve Consumer Appeal for Environmentally Preferable Products. Environ. Sci. Policy Sustain. Dev. 2006, 48, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, R.; Koenig, S. Probabilistic Robot Navigation in Partially Observable Environments. In Proceedings of the 14th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–25 August 1995; Volume 2, pp. 1080–1087. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y.; Siddik, A.B.; Masukujjaman, M.; Zheng, G.; Hamayun, M.; Ibrahim, A.M. The Antecedents of Willingness to Adopt and Pay for the IoT in the Agricultural Industry: An Application of the UTAUT 2 Theory. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Illia, A.; Lawson-Body, A. Perceived Price Fairness of Dynamic Pricing. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2011, 111, 531–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, V. Determining Students’ Language Needs in a Tertiary Setting. Engl. Teach. Forum 2001, 39, 16–27. Available online: https://americanenglish.state.gov/files/ae/resource_files/01-39-3-d_0.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- Hedlund, T. The Impact of Values, Environmental Concern, and Willingness to Accept Economic Sacrifices to Protect the Environment on Tourists’ Intentions to Buy Ecologically Sustainable Tourism Alternatives. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2011, 11, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah Alam, S.; Mohamed Sayuti, N. Applying the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) in Food Purchasing. Int. J. Commer. Manag. 2011, 21, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.S.; Janor, H.; Zanariah, C.; Ahsan, M.N. Is Religiosity an Important Factor in Influencing the Intention to Undertake Islamic Home Financing in Klang Valley. World Appl. Sci. J. 2012, 19, 1030–1041. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable Food Consumption among Young Adults in Belgium: Theory of Planned Behaviour and the Role of Confidence and Values. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 64, 542–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Siddik, A.B.; Masukujjaman, M. Factors Affecting the Repurchase Intention of Organic Tea among Millennial Consumers: An Empirical Study. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masukujjaman, M.; Alam, S.S.; Siwar, C.; Halim, S.A. Purchase Intention of Renewable Energy Technology in Rural Areas in Bangladesh: Empirical Evidence. Renew. Energy 2021, 170, 639–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, H.H. Modern Factor Analysis; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1976; ISBN 0226316521. [Google Scholar]

- Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Mooi, E.A. Response-Based Segmentation Using Finite Mixture Partial Least Squares. In Proceedings of the Data Mining; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 19–49. [Google Scholar]

- Compeau, D.; Higgins, C.A.; Huff, S. Social Cognitive Theory and Individual Reactions to Computing Technology: A Longitudinal Study. MIS Q. 1999, 23, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aibinu, A.A.; Al-Lawati, A.M. Using PLS-SEM Technique to Model Construction Organizations’ Willingness to Participate in e-Bidding. Autom. Constr. 2010, 19, 714–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, F.; Lim, B.; Prasad, D. An Investigation of Corporate Approaches to Sustainability in the Construction Industry. Procedia Eng. 2017, 180, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.J.; Raposo, M.L.; Rodrigues, R.G.; Dinis, A.; Paço, A.d. A Model of Entrepreneurial Intention: An Application of the Psychological and Behavioral Approaches. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2012, 19, 424–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triguero-Sánchez, R.; Peña-Vinces, J.C.; Sánchez-Apellániz, M. Hierarchical Distance as a Moderator of HRM Practices on Organizational Performance. Int. J. Manpow. 2013, 34, 794–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Will, S. SmartPLS 2.0 (M3) Beta; University of Hamburg: Hamburg, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, D.; Higgings, C.; Thompson, R. The Partial Least Squares (PLS) Approach to Casual Modeling: Personal Computer Adoption and Use as an Illustration. Technol. Stud. 1995, 2, 285–309. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Weaver, S.E.; Hamill, A.S. Risks and Reliability of Using Herbicides at Below-Labeled Rates. Weed Technol. 2000, 14, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, S.; D’ambra, J.; Ray, P. An Evaluation of PLS Based Complex Models: The Roles of Power Analysis, Predictive Relevance and GoF Index. 2011. Available online: https://ro.uow.edu.au/commpapers/3126 (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- Wong, P.S.P.; Cheung, S.O. Structural Equation Model of Trust and Partnering Success. J. Manag. Eng. 2005, 21, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinbaum, D.G.; Kupper, L.L.; Nizam, A.; Rosenberg, E.S. Applied Regression Analysis and Other Multivariable Methods; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2013; ISBN 128596375X. [Google Scholar]

- Santosa, P.I.; Wei, K.K.; Chan, H.C. User Involvement and User Satisfaction with Information-Seeking Activity. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2005, 14, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, R.F.; Miller, N.B. A Primer for Soft Modeling; University of Akron Press: Akron, OH, USA, 1992; ISBN 0962262846. [Google Scholar]

- Wetzel, H.A.; Hammerschmidt, M.; Zablah, A.R. Gratitude versus Entitlement: A Dual Process Model of the Profitability Implications of Customer Prioritization. J. Mark. 2014, 78, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, F.; Gopinath, C. Antecedents of Environmental Conscious Purchase Behaviors. Middle East J. Sci. Res. 2013, 14, 979–986. [Google Scholar]

- Teo, W.L.; Abd Manaf, A.; Choong, P.L.F. Information Technology Governance: Applying the Theory of Planned Behaviour. J. Organ. Manag. Stud. 2013, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adham, S.; Hussain, A.; Minier-Matar, J.; Janson, A.; Sharma, R. Membrane Applications and Opportunities for Water Management in the Oil & Gas Industry. Desalination 2018, 440, 2–17. [Google Scholar]

- Shah Alam, S.; Masukujjaman, M.; Sayeed, M.S.; Omar, N.A.; Ayob, A.H.; Wan Hussain, W.M.H. Modeling Consumers’ Usage Intention of Augmented Reality in Online Buying Context: Empirical Setting with Measurement Development. J. Glob. Mark. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansar, N. Impact of Green Marketing on Consumer Purchase Intention. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2013, 4, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, J.S.S.; Mansori, S. Young Female Motivations for Purchase of Organic Food in Malaysia. Int. J. Contemp. Bus. Stud. 2012, 3, 61–72. [Google Scholar]

| Sources | Research Method/Sample Size/Country | Analysis Tools | Research Model | Significant Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [4] | Empirical/ Questionnaire survey/Construction participants/180/China | Logistic regression Model-SPSS | TPB | Environmental awareness, green home comfort, neighbors’/friends’ assessment and government incentive |

| [12] | Empirical/Online survey/residents/330/Australia | SEM (AMOS) | TPB | Perceived behavioural control, green consumer identity, subjective norms, and attitudes |

| [21] | Empirical/Student Interview/304/ USA | Multinomial logistic regression | Dual-Inheritance Theory and Normative Motivation | Intrinsic, instrumental, non-normative motivation, barriers |

| [22] | Empirical/Questionnaire survey/208/ China | SEM (AMOS) | TPB | Attitude, perceived behavioural control and subjective norms |

| [23] | Empirical/ Online survey/Young consumers/241/China | SEM (AMOS) | Extended TPB | Subjective norms, attitude, subjective knowledge, environmental concern, governmental initiatives |

| [24] | Empirical/Online survey/Urban residents/728/China | PLS-SEM | No existing model used | Perceived value, perceived benefits, environmental concern, perceived risk |

| [25] | Empirical/Face-to-face interview/Resident of Dhaka/319/Bangladesh | SEM (AMOS) | TPB | Environmental knowledge, environmental concern, subjective norms, perceived behavioural control, attitude |

| [30] | Empirical/Questionnaire survey/304/ Malaysia | PLS-SEM | No existing model used | Attitude, moral obligation, environmental concern, perceived value, perceived self-identity, financial risk |

| Variable | ATT | EC | GBK | BI | PBC | PV | RP | SN | CR | AVE | Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATT | 0.842 | 0.924 | 0.709 | 0.898 | |||||||

| EC | 0.686 | 0.908 | 0.934 | 0.825 | 0.894 | ||||||

| GBK | 0.658 | 0.590 | 0.845 | 0.881 | 0.715 | 0.796 | |||||

| BI | 0.745 | 0.621 | 0.775 | 0.853 | 0.914 | 0.729 | 0.875 | ||||

| PBC | 0.628 | 0.512 | 0.704 | 0.701 | 0.890 | 0.919 | 0.792 | 0.868 | |||

| PV | 0.745 | 0.658 | 0.756 | 0.842 | 0.654 | 0.836 | 0.921 | 0.700 | 0.892 | ||

| RP | 0.663 | 0.596 | 0.655 | 0.685 | 0.652 | 0.681 | 0.866 | 0.923 | 0.750 | 0.888 | |

| SN | 0.320 | 0.322 | 0.314 | 0.411 | 0.367 | 0.331 | 0.304 | 0.943 | 0.942 | 0.890 | 0.877 |

| Endogenous Variables | R2 |

|---|---|

| Behavioural Intention | 0.454 |

| Attitude | 0.294 |

| Perceived Behavioural Control | 0.302 |

| Subjective Norm | 0.281 |

| Hypotheses | Path Coefficients (β) | t-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude → Intention | 0.451 | 15.616 ** | 0.001 |

| Subjective Norm → Intention | 0.090 | 3.702 ** | 0.001 |

| Perceived Behavioural Control → Intention | 0.385 | 13.102 ** | 0.001 |

| Hypotheses | t-Value | p-Value | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1: ATT → BI | 5.870 ** | 0.001 | Significant |

| H2: SN → BI | 2.160 * | 0.031 | Significant |

| H3: PBC → BI | 4.061 ** | 0.001 | Significant |

| H4: EC → ATT | 12.092 ** | 0.001 | Significant |

| H5: EC → SN | 4.349 ** | 0.001 | Significant |

| H6: EC → PBC | 3.557 ** | 0.010 | Significant |

| H7: EC → BI | 0.697 | 0.485 | Not Significant |

| H8: GBK→ ATT | 12.134 ** | 0.001 | Significant |

| H9: GBK→ SN | 4.523 ** | 0.001 | Significant |

| H10: GBK → PBC | 18.368 ** | 0.001 | Significant |

| H11: GBK → BI | 6.949 ** | 0.001 | Significant |

| H12: PV →BI | 11.846 ** | 0.001 | Significant |

| H13: RP → BI | 5.094 ** | 0.001 | Significant |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Masukujjaman, M.; Wang, C.-K.; Alam, S.S.; Lin, C.-Y.; Ho, Y.-H.; Siddik, A.B. Green Home Buying Intention of Malaysian Millennials: An Extension of Theory of Planned Behaviour. Buildings 2023, 13, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13010009

Masukujjaman M, Wang C-K, Alam SS, Lin C-Y, Ho Y-H, Siddik AB. Green Home Buying Intention of Malaysian Millennials: An Extension of Theory of Planned Behaviour. Buildings. 2023; 13(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleMasukujjaman, Mohammad, Cheng-Kun Wang, Syed Shah Alam, Chieh-Yu Lin, Yi-Hui Ho, and Abu Bakkar Siddik. 2023. "Green Home Buying Intention of Malaysian Millennials: An Extension of Theory of Planned Behaviour" Buildings 13, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13010009

APA StyleMasukujjaman, M., Wang, C.-K., Alam, S. S., Lin, C.-Y., Ho, Y.-H., & Siddik, A. B. (2023). Green Home Buying Intention of Malaysian Millennials: An Extension of Theory of Planned Behaviour. Buildings, 13(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13010009