1. Introduction

Industry 4.0, also known as the fourth industrial revolution, was first coined in 2011 at the Hannover Fair in Germany. It seeks to merge the digital, physical, and biological spheres into a single sphere [

1,

2,

3]. This industrial revolution is dominated by the application of digital technologies, such as cyber–physical systems, the Internet of Things, big data analysis, and artificial intelligence [

3]. Such technologies have been implemented in multiple industries, including the financial industry [

4], manufacturing [

5], education [

6], and agriculture [

7], which resulted in considerable performance improvements.

As one of the largest industries globally, the construction industry can also benefit from adopting digital technologies, e.g., Building Information Model (BIM), cloud-based project management, and drone systems, as they offer construction organisations great opportunities to increase their competitiveness in the current business environment [

8,

9,

10]. The term Construction 4.0 has been proposed to represent the branch of Industry 4.0 in the construction industry, which is related to all of the changes in work methods in all aspects of the construction industry caused by technological changes, both in software and hardware, and their application [

8,

10,

11].

Researchers and practitioners recognise the significance of technology advancement and have made efforts to usher the construction industry into the era of Construction 4.0. Nevertheless, progress has been slow due to multiple barriers to the adoption of digital technologies [

12,

13,

14,

15]. A significant barrier is the construction industry’s bureaucratic, conservative, and risk-averse characteristics [

15,

16,

17]. As a result, most practitioners have not shown enough motivation to apply new technologies in their daily work. Furthermore, the construction industry is highly fragmented. Different stakeholders have their own demands and expectations, which have become an obstacle for the industry’s collective strategic actions to embrace Construction 4.0 [

15].

Effective leadership is crucial to break these barriers and facilitate the construction industry to adopt Construction 4.0 practices [

18,

19]. Although the content of a leader’s work varies by position, the impact of leadership on organisational performance has been demonstrated in multiple ways, such as in creating a culture of innovation, attracting talents, and building trust [

20,

21,

22,

23]. Effective leadership exists at every level of an organisation, which is manifested in different roles, such as initiator, communicator, motivator, coordinator, advocate, and even commander (or controller), to promote organisational transformation [

19,

24,

25,

26,

27]. Nam and Tatum [

28] initially proposed the importance of leadership for promoting innovations in the construction industry. Since then, research has investigated the impact of different leadership competencies on innovations in the construction industry. Bossink [

29], for example, demonstrated the positive impact of leaders demonstrating knowledge management on adopting sustainable innovations in construction projects in the Netherlands. The role of leadership has been found to not only facilitate construction organisational transformation, but also promote the organisation to adopt new technologies. Ozorhon et al. [

30] stated that leaders’ behaviours can provide strong support for construction organisations to overcome barriers to progress and innovate. Waziri et al. [

31] showed the role of transformational leadership behaviours in promoting technology adoption in construction organisations. Effective leadership is also believed to be crucial to mitigate the aforementioned barriers. However, while current literature is helpful in enriching our understanding of leadership for Construction 4.0, the findings remain scattered. Therefore, a systematic literature review is needed to bring together existing knowledge and develop a complete picture of leadership competencies for promoting Construction 4.0 practices.

As the first focused review of leadership research in the context of Construction 4.0, the main purpose of this study is to identify and define important leadership competencies to all construction industry organisations to operate in Construction 4.0. The results are expected to help construction organisations develop human resource management strategies appropriate for Construction 4.0, and help individuals develop key leadership competencies to be effective leaders in this era. In addition, by reviewing the leadership literature in this specific context, this research can also identify research gaps and limitations, so that recommendations can be made to guide future research on leadership in Construction 4.0 for better supporting the construction industry to enter the digital age.

2. Research Design and Methods

In order to achieve the aforementioned research objectives, this research adopts a methodology that draws on the research process of the systematic literature review that constructs new knowledge based on analysing and interpreting the existing research [

32]. This study adopts this process for identifying the key leadership competencies in the context of Construction 4.0 and providing a guide for conducting effective leadership for construction organisations.

In terms of the literature retrieval method, Wohlin [

33] illustrates the value of the backward snowballing method, which involves searching reference lists to identify relevant papers to be included in the analysis. This method is presented as a way to capture highly relevant literature that may be missed in conventional database searches. Therefore, this study adopts the backward snowballing method after using the conventional keyword database search method to obtain relevant literature [

33,

34]. After selecting relevant literature, a thematic analysis was carried out for categorising and interpreting the leadership competencies in the context of Construction 4.0. In the above processes, one researcher (the first author) was responsible for the initial retrieval, collection, and analysis of the literature papers to ensure consistency, and the other two authors reviewed each step to refine the outcomes.

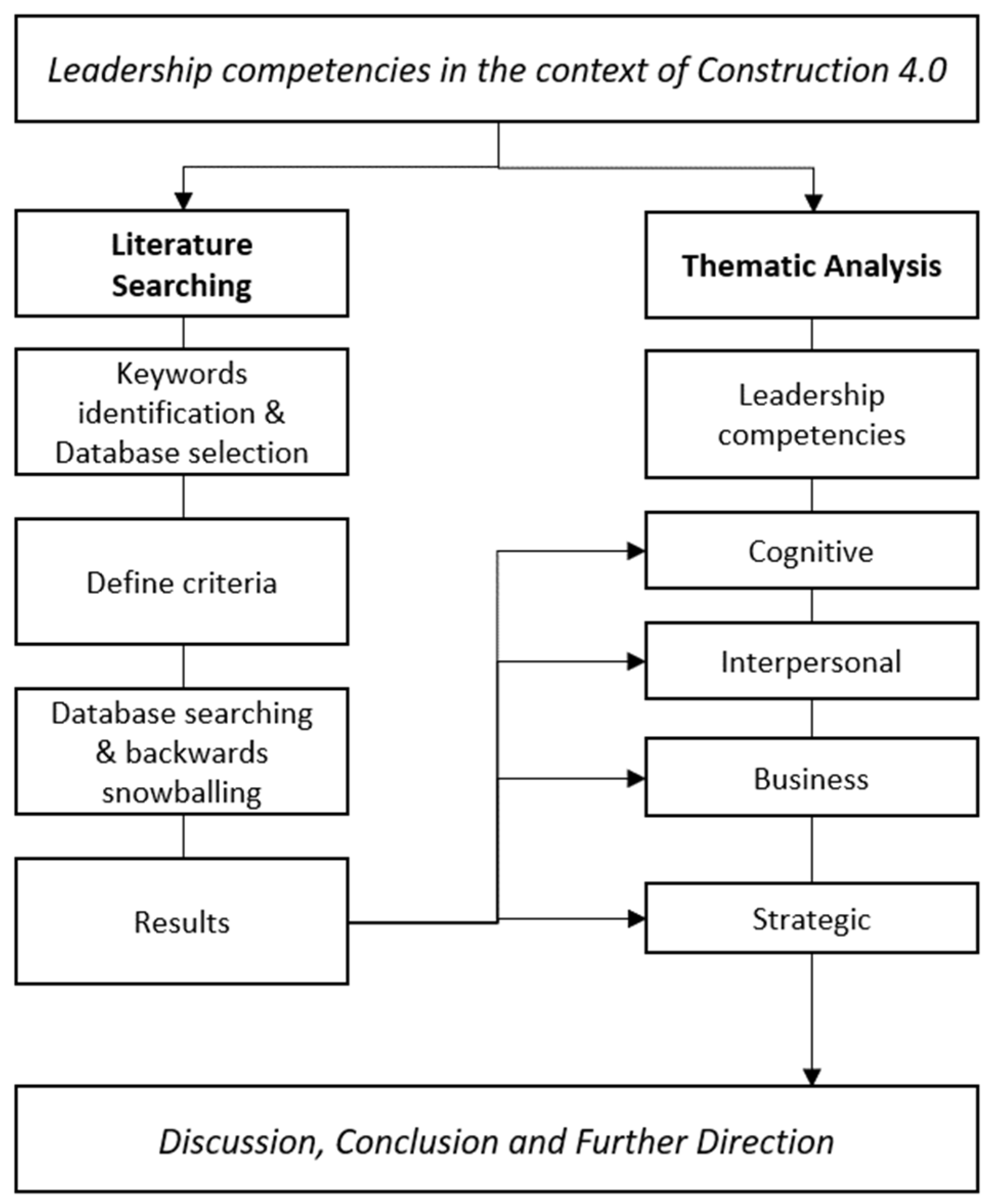

In conducting the thematic analysis, top-level themes are predefined using the four domains proposed by Mumford et al. [

35], which are widely accepted and cited by previous studies [

36,

37,

38]. These four domains are cognitive, interpersonal, business, and strategic. The methodological approach is illustrated in

Figure 1 [

39].

The first step of this study is to define the searching keywords and the searching database. Keywords and synonyms related to ‘construction industry’, ‘Construction 4.0’, and ‘leadership competencies’ are selected in this study for database searching. The database used in this study is Scopus, as it covers a wider range of the literature than Web of Science and has precise searching results [

39,

40].

The string of keywords was established for database searching as: (‘AEC industry’, ‘construction project*’, ‘construction organization*’, ‘construction’, and ‘built environment’) AND (‘Construction 4.0’, ‘Industry 4.0’, ‘fourth industrial revolution’, ’4IR’, ‘digital transition’, ‘digital transformation’, and ‘digital age’) AND (‘leadership’ and ‘leader’). While conducting the database search, two other filtering rules were applied: (1) the paper is published in English, and (2) the paper is published from 2011, as the concept of ‘Industry 4.0’ was proposed in 2011 [

41]. The database search was conducted on 17 March 2022, which means the publication year range is 2011 to March 2022.

A manual screening was conducted on the results of the database search to ensure the suitability of the retrieved literature. Several rules were applied when conducting the manual screening and backward snowballing (see

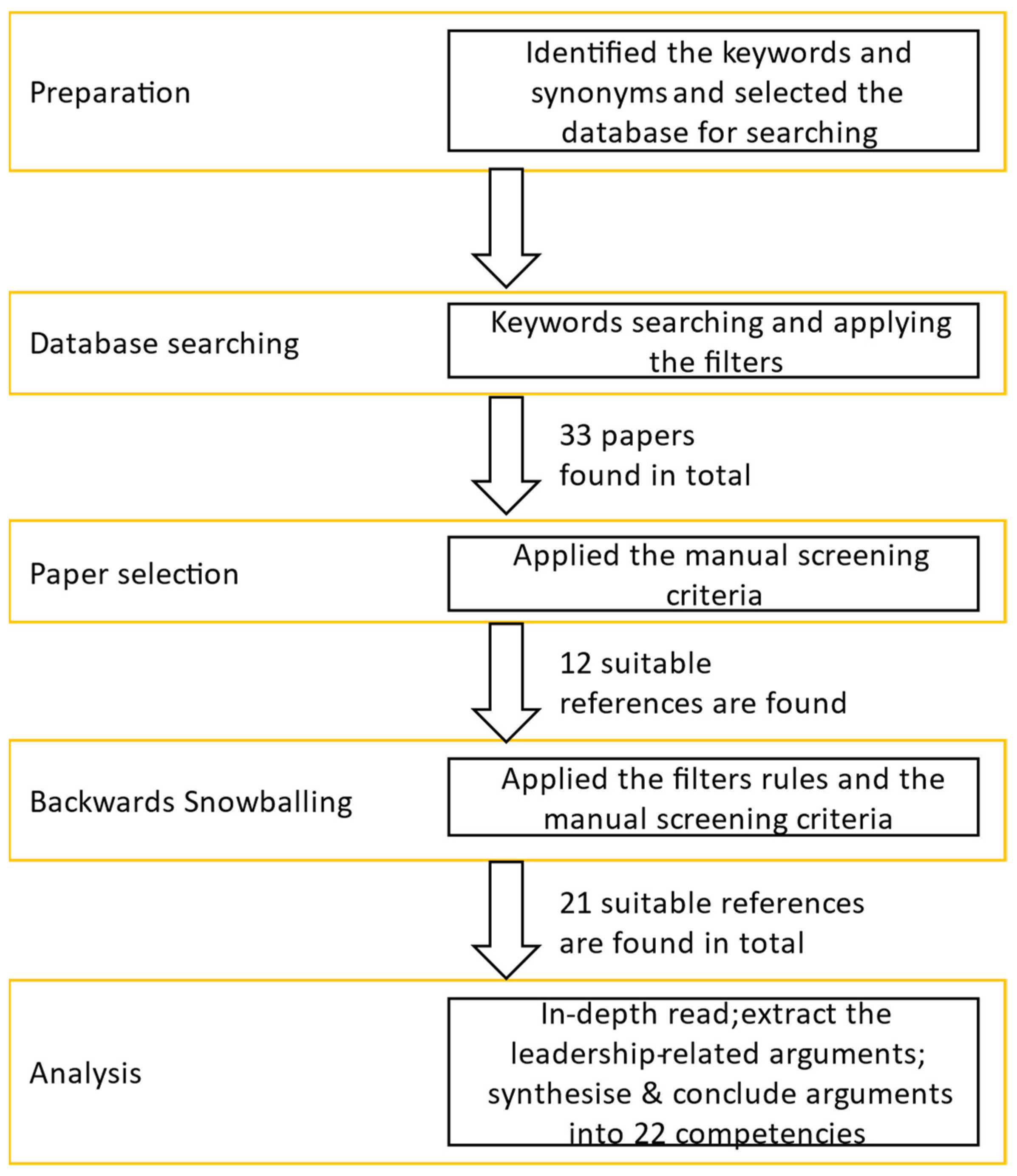

Figure 2). The selected paper should satisfy all of the following: (1) published in peer-reviewed journals, conference proceedings, or scholarly books, while website publication and magazine-style papers are excluded; (2) closely related to the construction and engineering management, construction education, or construction organisation management area; (3) relevant to ‘Construction 4.0’ or changes induced by technological advancement; and (4) discusses leadership-related issues or provides insights for guiding leadership behaviour.

Figure 2 illustrates the overall literature retrieval process. The searching process begins with the database search to identify the relevant papers. Overall, 33 papers were found from Scopus after a keyword search was conducted. After applying the manual screening criteria and careful reading, 12 papers were selected and used as the starting set of papers for the backward snowballing search. Using the backward snowballing method, nine additional papers were identified and included in this study.

Before conducting the thematic analysis, an initial scan was applied to understand the basic information of the papers (including the theory, research topic, and methodology) and to number them [

15,

19,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60] for easier referencing in later analysis. Following this, in-depth reading was conducted to extract the leadership competencies-related information from the selected papers and to note down the original statement into an Excel file. When completed, the file was read carefully to summarise similar competency statements (which form the second-level themes in this study) and initially define the name or description of each competency. Afterwards, each competency name was reviewed to ensure they were appropriate and then were categorised into one of four domains (the top-level themes of this study). Due to the space restraint, this paper provides two examples of the leadership competencies to show how each competency was drawn from literature.

Table 1 and

Table 2 present “Tolerance of failure” and “Persuasion”, which were identified based on the relevant literature.

3. Results and Discussion

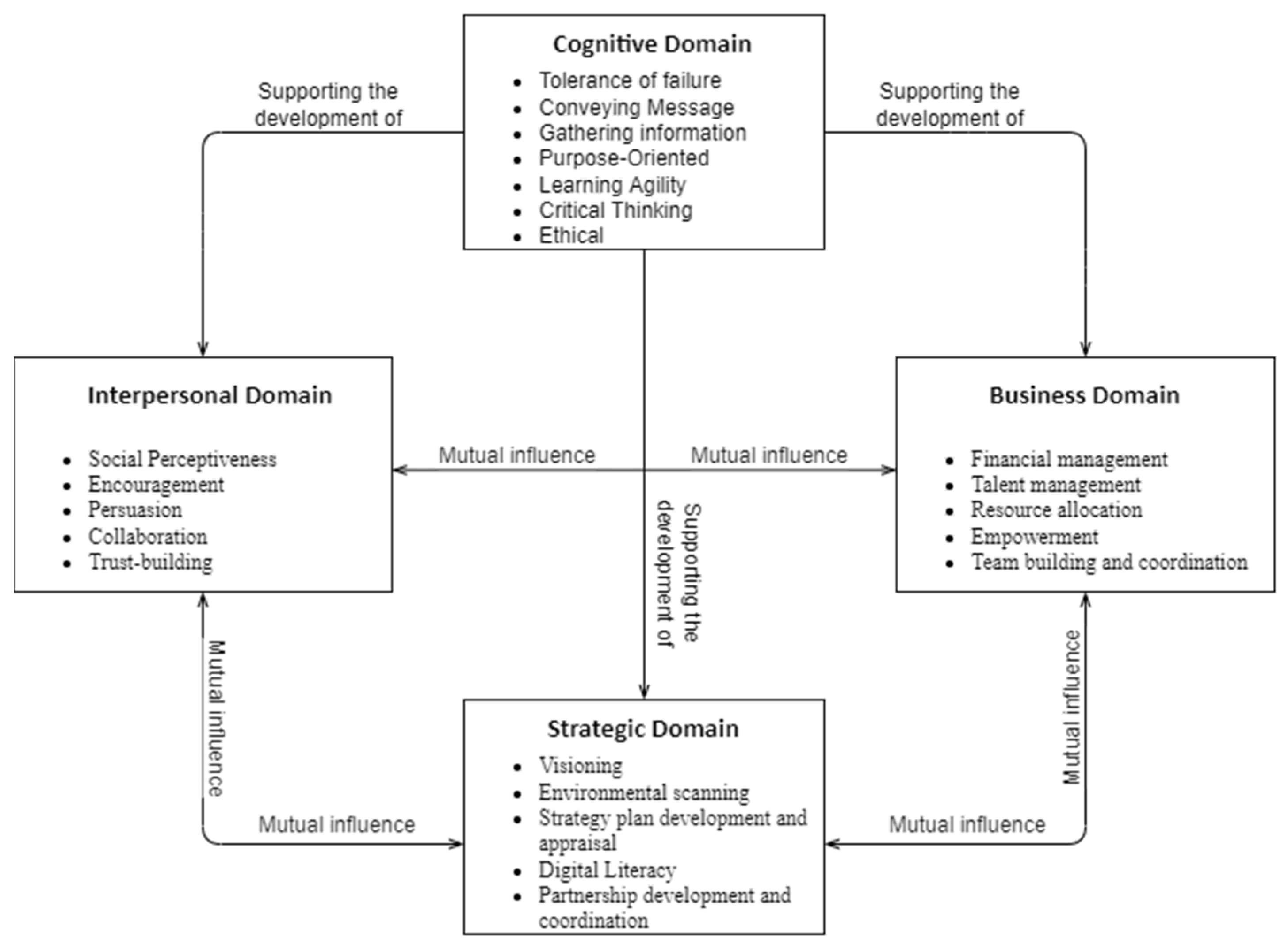

From the selected 21 publications, 22 leadership competencies were identified, and

Figure 3 shows how the 22 competencies are classified into the four domains following the thematic analysis. The potential relationships between each domain are also given based on Mumford et al. [

35]. Among the four domains, the cognitive domain can be considered as a fundamental domain that supports the development of competencies in other domains [

35,

38]. For example, Conveying Message, as one of the competencies in the cognitive domain, can provide leaders with the fundamental capability to the competencies in other domains (e.g., persuasion in the interpersonal domain; team building and coordination in the business domain; and visioning in the strategic domain). Furthermore, there may also have interrelationships among interpersonal, business, and strategic domains. The interpersonal domain gives leaders the ability to communicate, interact, and influence individuals, while the business domain gives leaders the ability to influence the day-to-day operations of the organisation, including the ability to manage and adjust the organisational structure. The interpersonal competencies can support the application of competencies in the business domain by engaging employees effectively, while the business domain provides the meaning and goals for the practice of interpersonal competencies [

51,

60,

61]. At the same time, the application of competencies in both the interpersonal and business domains can indirectly and directly support leaders in solving complex environmental problems and effectively preparing the organisation for the future, which is part of the strategic domain [

15,

59]. Furthermore, competencies in the strategic domain equip leaders with the ability to envision and affirm the future of the organisation, which provide directions for competencies in the interpersonal and business domains [

43,

53].

This section provides details for each domain and competency.

3.1. Cognitive Domain

‘Cognitive’ is a popular term used in previous leadership, decision-making, and management-related publications. Although definitions vary, the cognitive domain is usually defined as the intellectual activity or capability of a person to recognise an event, object, interrelationship, or environment [

62,

63,

64]. The cognitive domain is considered a set of competencies that underlie effective leadership. Competencies in this domain provide construction leaders with essential capabilities to behave and think in the dynamic environment of Construction 4.0, and to perceive the surrounding environments and the interrelationships among factors within them.

There are seven competencies (tolerance of failure, conveying message, gathering message, purpose orientation, learning agility, critical thinking, and acting ethically) in this domain. Tolerance of failure, purpose orientation, and critical thinking also serve as a basis for the other three competencies: conveying messages, gathering information, and learning agility, while acting ethically is an overarching principle to ensure leaders act morally.

3.1.1. Tolerance of Failure

The development of new technologies and their initial application tend to be exploratory, and mistakes are bound to occur. The inherently strict risk-management behaviour and risk-aversion mentality of construction leaders can hinder digital technology innovation and adoption in the construction industry. Leaders should be open to mistakes in the technological innovation process, as this will help create a conducive environment and motivate employees to innovate [

15,

43,

53,

58]. Leaders in the context of Construction 4.0 should pay more attention to how much employees learn from failures and develop themselves [

58,

65]. Tolerating failure is an important first step to becoming a qualified leader in Construction 4.0, because it facilitates the development of an innovative culture, which promotes the enthusiasm of employees for embracing digital technologies.

3.1.2. Purpose Orientation

Leaders with a purpose-oriented mindset demonstrate patience and focus more on the results when making decisions or performing managerial actions [

66]. The leader mentality is highlighted as one of the competencies that leaders in the context of Construction 4.0 should have, and purpose orientation helps leaders focus on organisational goals when making decisions and taking managerial actions. This purpose-oriented mindset helps leaders to be more focused in their day-to-day management while increasing their effectiveness at work, which will help leaders lead the transformation of construction organisations in the context of Construction 4.0 [

44,

52,

56].

3.1.3. Critical Thinking

Critical thinking refers to a positive personal mode of thinking in which a leader makes judgements based on the analysis of facts, evidence, observations, and arguments [

67]. Construction leaders need this competency because it helps them objectively look at opportunities and challenges that organisations encounter in Construction 4.0 [

44]. In fact, each construction organisation, and even the various departments within the organisation, face different circumstances. Leaders should look critically at the problems or opportunities that their department or organisation encounters, and then come up with solutions [

47,

56,

59]. In addition, leaders should also have their own judgement on the adoption of digital technologies, particularly for selecting digital technologies that are suitable for the current situation of their organisations or department [

43,

59].

3.1.4. Conveying Messages

Having an effective process of conveying messages to others, including using various methods to convey messages effectively, is an essential ability of leaders [

68,

69,

70]. Construction leaders working in the Construction 4.0 era need to convey messages to employees to ensure that they understand the opportunities and risks that the organisation encounters in implementing new technologies. They should also relay information to the public (through social media and other platforms) to increase public awareness of their organisation’s operation with an intention to enhance the organisation’s reputation [

43,

47,

51,

53]. Leaders with the capability to convey the necessary information concisely are necessary for aligning employees’ goals and beliefs [

52,

56,

59]. In Construction 4.0, the leaders with good competency in conveying these messages can facilitate a digital transformation in the organisation.

3.1.5. Gathering Information

Gathering information through active listening or reading is an essential ability for the daily management and leading of an organisation [

71]. The goal of gathering information is to obtain all of the information that the leader needs to make informed decisions. Several selected papers highlight that gathering information is a key competency because it can help leaders reduce resistance during organisational transformation and provide additional references/insights when the leaders make managerial actions [

15,

43,

46,

51,

52]. For example, a construction organisation that decides to move into Construction 4.0 needs to change its culture and daily work patterns. If it is not done properly, implementing this change can lead to a variety of problems. The leaders should, therefore, actively listen to the concerns of different stakeholders, including considering suggestions from the grassroots of the organisation in their decision-making process to ensure a smoother transition into Construction 4.0.

3.1.6. Learning Agility

Active learning leaders are able to process new information and grasp its meaning. Active learning enables leaders to adjust their behaviours and strategies in a timely manner to deal with dynamic situations at work. In recent years, a new concept called ‘learning agility’ has been proposed to better encapsulate the meaning of active learning. Learning agility emphasises a leader’s willingness to learn new knowledge and be open-minded in applying new knowledge, concepts, or lessons in difficult conditions [

35,

72]. In the context of Construction 4.0, construction leaders need to recognise their own deficiencies in knowledge and understanding and make efforts to fill the gap in a variety of ways, such as back-to-school learning, attending academic seminars, and learning from experience [

42,

44,

47,

56]. Through learning, the leaders will improve their adaptability and flexibility, which not only improves leaders’ decision-making abilities in the digital age, but also helps organisations effectively adopt digital technologies [

43,

48].

3.1.7. Acting Ethically

Ethics is a set of ethical principles that guide leaders in their activities and decisions at work and in their personal lives [

73]. The topic of ethics in the construction industry has been widely discussed in previous research. Unethical behaviour may cause lasting consequences to construction organisations, such as increasing uncertainty in tendering, criminal prosecutions, increasing operational cost, and reputation issues [

74]. Unethical behaviour, manifested in poor building quality, also affects not only construction organisations, but also their clients and the community at large as building users. Leaders acting ethically is highlighted often in some previous Construction 4.0 research [

43,

47,

56]. The leaders, for example, should be able to demonstrate integrity and treat employees of different backgrounds equally. The aims are not only to reduce the risks from unethical practice, but also to create an essential foundation for building trusting relationships with others, as trusting relationships can facilitate organisational operation in the digital age.

3.2. Interpersonal Domain

Leaders often play the role of convening people towards a common goal in an organisation, which requires the leaders to have sufficient interpersonal and social skills to interact with others. Therefore, the leadership competencies covered in this area are primarily related to how leaders interact with others, create and maintain relationships with others, and motivate others. Through the selected papers, five leadership competencies were identified and considered to be in the interpersonal domain, and they are social perceptiveness/awareness, encouragement, persuasion, collaboration, and trust-building. Social perceptiveness/awareness can be seen as the basis competency for leaders when they interact with others, and the foundation for other competencies in this domain. Moreover, trust-building is a competency that is the basis for the other three competencies: encouragement, persuasion, and collaboration.

3.2.1. Social Perceptiveness/Awareness

Social perceptiveness/awareness can be seen as a basic ability that supports leaders in developing and maintaining interpersonal relationships with others [

75]. Although this competency is not explicitly addressed in the reviewed papers, many of the papers have implicit requirements for leaders to be socially perceptive to operate successfully in Construction 4.0 [

19,

47,

51,

52,

54,

55,

56,

57]. For example, leaders are advised to build an effective cross-functional team to more effectively respond to changes in the new business environment. Leaders are expected to play a role that promotes collaboration and trust in the team, which requires leaders to understand how different identities and roles respond to events and to respond accordingly in a timely manner to achieve goals.

3.2.2. Encouragement

Encouragement is an approach that leaders use to motivate employees to accept new things. Encouragement emphasises supporting employees on a spiritual level, such as giving them courage, hope, and spirit. Innovating and adopting new technologies are undoubtedly challenging for practitioners in the construction industry. In the new environment of Construction 4.0, employees may face the risk of losing trust and personal image, having more conflicts with peers, innovation failure, and increased resignation intention, which will cause employees to worry and reject changes [

76]. In this case, construction leaders can facilitate organisational transformation and ensure success under Construction 4.0 by skilfully encouraging employees to innovate and adopt new technologies [

19,

43,

49,

53,

55].

3.2.3. Persuasion

Persuasion is a competency based on a leader’s communication ability to influence the attitude and behaviour of others [

77]. Unlike encouragement, leaders usually use persuasion at the beginning of the transformation, i.e., leaders use persuasion to make others resonate with them, thereby reducing potential opposition during the transformation process and making others understand the organisation’s vision. Construction leaders, who want to initiate the digital transformation, should make the employees see the value of the new technologies and gain supporters by persuasion [

52,

53,

55,

56]. Employees’ recognition and understanding of organisational change needs can make the implementation of change more effective, and employees will be more likely to take actions to promote organisational digital change on their own [

46,

59].

3.2.4. Collaboration

Collaboration in leadership generally refers to the interaction and cooperation of a variety of people who have multiple perspectives. Previous research states that leaders with a good collaboration competency are better at inspiring commitment and action, building broad participation and sustaining team passion [

78]. Leaders, particularly top executives in construction organisations, believe that there should be more collaboration than in the past in the digital transformation process and day-to-day operations in Construction 4.0 [

19,

39,

42,

45,

52,

54,

59]. The collaborative behaviours of leaders and managers at all levels, such as actively listening to opinions and gaining feedback from different perspectives, learning and practising digital technologies by example, and actively monitoring the digital transformation process, are believed to promote the success of an organisation in the digital age [

15,

43,

44,

79].

3.2.5. Trust-Building

Earning the trust of employees and stakeholders is considered one of the activities construction leaders should do in promoting Construction 4.0 [

43]. Building trust, considered a necessary leader’s ability in the leadership-related research, requires leaders to demonstrate a range of competencies, including empathy, reliability, and communication [

80,

81]. By building interpersonal trust with employees, the trust mechanism and culture within the organisation is developed. This trust relationship can promote intra-organisational cooperation, promote organisational dynamic capabilities, and reduce resistance to transformation [

43,

52]. Building trust with external stakeholders has also been emphasised in past research. This trust relationship can provide organisations with better environmental adaptability and the ability to adapt to using digital technology [

54,

59,

60].

3.3. Business Domain

In their daily work, leaders are considered to have business capabilities related to specific functional areas to support the operations of the organisation. In Construction 4.0, leadership competencies in the business domain help organisations run and grow smoothly. Competencies in this domain primarily relate to the leaders’ management capabilities, which enable the leaders to adjust organisational management, such as developing appropriate talent development plans or investment plans. Through the selected publications, five competencies are identified and grouped into this domain, and they are financial management, talent management, resource allocation, empowerment, and team building and coordination.

The competencies in this domain closely link to each other. Here, empowerment is the competency that refers to leaders empowering a team or individuals with autonomy. This empowerment competency of leaders may be supported by talent management (choosing the appropriate individual) and financial management (provide reasonable funding support). It is also related to providing support through resource allocation and team building and coordination (assign the individual or team to a suitable position, and empower with the appropriate autonomy).

3.3.1. Financial Management

Financial management is a functional ability of leaders that primarily refers to the planning, directing, and controlling of funding activities [

35]. The reviewed literature highlights the importance of funding for digital technology-related innovations and adoption, which requires leaders to have appropriate funding management plans and substantial financial support to develop technology innovation support structures for transforming the organisation. Leaders need to consider the significance, applicability, and risk of each digital technology to develop an appropriate investment structure and criteria to promote the organisational digital technologies development [

43,

45,

50,

51,

57,

60].

3.3.2. Talent Management

Talent management is a part of human resource management and is positioned in previous research as the systematic activity of attracting, identifying, developing, hiring, retaining, and deploying talent within an organisation [

82]. With the development of digital technology in the construction industry, the demand for employees with digital technology-related capabilities will slowly rise, which means that it becomes essential to re-consider talent development plans and selection criteria. As such, construction leaders are required to possess talent management competencies in the Construction 4.0 environment to develop the organisation’s talent pool, which covers (but is not necessarily limited to) recruiting suitable new employees, improving the skills of existing employees, and establishing appropriate training programmes to better meet the challenges brought by the new environment [

42,

45,

47,

50,

51,

56,

57,

58,

59].

3.3.3. Resource Allocation

Resource allocation refers to a leader’s ability to manage and allocate an organisation’s tangible and intangible assets in a manner that supports the organisation’s strategic goals [

83]. Construction 4.0 leaders should have strong resource allocation capabilities, because construction organisations will undergo a series of major changes in terms of their operating models, organisational structure, and personnel [

50,

51,

55,

57,

58,

59,

60]. Leaders should rationally allocate and reallocate organisational resources in a timely manner to effectively respond to the changes brought about by the digital age.

3.3.4. Empowerment

Empowerment refers to giving a team or an individual autonomy (e.g., decision making) in their daily work and encouraging them to conduct self-direction and reflection through a combination of actions [

84]. In previous literature, this particular act of empowerment was found to originate when organisations are challenged both internally and externally [

85]. Empowerment itself does not mean depriving managers of their own power. The purpose is to allow all organisational participants to use their time and energy more effectively to face and deal with challenges. In reviewing the Construction 4.0 literature, leaders are also highlighted as having the competencies, behaviours, and mindsets that foster organisational empowerment. Empowerment will help organisations foster synergy potential and stimulate bottom-up technological innovations to help organisations better face the challenges posed by the digital age [

19,

43,

44,

50,

53,

55,

60].

3.3.5. Team Building and Coordination

Effective teams help organisations improve performance, and leaders are required to have a team building and coordination competency to build such teams [

69,

86,

87]. As the construction industry moves into the digital age, construction leaders should not only have the ability to build appropriate project teams, but also to build cross-functional teams to help organisations respond effectively to dynamic environments [

43]. Leaders should be skilled enough to select the right professionals (which may include data analysts, strategists, and project managers) to join the team, reconcile cognitive differences, and address interpersonal and job-task conflicts among professionals from different backgrounds [

51,

54,

55]. In addition, some construction 4.0 researchers expressed their concern about the possible existence of organisational differences such as conflicts between old and new orders and cultural changes, which require leaders to have a sufficient ability to resolve conflicts between different departments or teams within the organisation [

19,

60].

3.4. Strategic Domain

Leadership competencies in the strategic domain empower leaders to solve complex problems and prepare for the future. Under the background of Construction 4.0, construction leaders need to pay more attention to the future planning of the organisation, which includes predicting future business environments and industry trends, applying various digital technologies, and planning for future directions and strategies. These competencies may be highly conceptual, but they help Construction 4.0 leaders disambiguate and effectively guide organisational development in the new business environment. The five competencies included in this domain are: visioning, environmental scanning, strategic plan development and appraisal, digital literacy, and partnership development and coordination. Those competencies are interlinked with each other. For example, the visioning competency is supported by the competencies of environmental scanning and digital literacy. In turn, it supports the competencies of strategic plan development and appraisal, and partnership development and coordination. Therefore, those competencies are all important to Construction 4.0 leaders, especially senior leaders, for being able to plan and give future instructions.

3.4.1. Visioning

Visioning is considered a process of forming a mental image. Setting a vision is the first step in leading an organisation into the future because it provides guidance for setting organisational goals and strategic plans. At the same time, by identifying future opportunities for the organisation, leaders can also develop, change, and motivate other organisational participants [

88]. In the context of Construction 4.0, mastering competencies in visioning is important for leaders to evaluate future scenarios (opportunities and threats that the organisations may meet in the future), create a clear and reasonable vision for the organisation’s future, and pass the vision on to the employees [

15,

43,

52,

57,

59]. This vision is crucial because it will not only provide the direction for the development of organisations, but will also provide the ongoing motivation to employees in their daily work [

45].

3.4.2. Environmental Scanning

The organisational environment comprises all of the external forces that directly or indirectly affect the organisation’s operations. Environmental scanning refers to leaders’ monitoring of emerging trends, changes, and challenges and assessing their likely impact and consequences on the organisation [

89]. With the intensified changes in the organisational environment when embracing Construction 4.0, environmental scanning, as one of the first steps in the organisational adaptation process, is crucial for leaders to keep abreast of changes in the environment, identify and analyse resistance or seize opportunities, and take appropriate actions to help the organisation succeed in the digital age [

15,

47,

52,

53,

57,

60].

3.4.3. Strategic Plan Development and Appraisal

Strategic plan development and appraisal involves re-examining the original strategic plan and reformulating an effective strategic plan by analysing internal and external environment differences and integrating the organisation’s vision and culture for the digital age [

51,

53,

56,

60,

90]. In addition, leaders should evaluate the effectiveness of the strategic plan by regularly assessing the ability of the strategic plan to respond to changing challenges in a timely manner [

19,

47,

59,

91]. This regular evaluation allows leaders to make some series of adjustments to the strategic plan during its implementation to ensure the long-term effectiveness of the strategic plan.

3.4.4. Digital Literacy

Digital literacy is sometimes also referred to as digital mindset or tech literacy, as a concept that is mentioned with increasing frequency in recent years [

92]. Through the literature review, embracing digital literacy has shown its growing importance to the leaders under Construction 4.0, which ensures a great digital understanding and knowledge for leaders when they make decisions or take management actions (for example, digital literacy will provide guidance for leaders when they decide to invest the digital technology in their organisation under Construction 4.0). Construction 4.0 leaders are required to have adequate digital literacy, so that they have the capability to provide more appropriate guidance and leadership for the organisation in the new business environment, which may include the capability to develop an appropriate vision and a change strategy, select the right digital partners, and improve the ability to sense opportunities and risks [

15,

43,

45,

51,

53,

55,

60].

3.4.5. Partnership Development and Coordination

Establishing partnerships is an important factor that has often been highlighted in previous research for delivering construction projects successfully. Through partnerships with different project stakeholders, construction projects are noted to be more likely to save time and cost, as well as achieve a higher standard of quality [

93]. In Construction 4.0 research, developing partnerships refers to developing relationships both at the project and organisational level. Construction organisations have been advised that they should consider partnering with the entire commercial system, which could include sub-contractors, academic units, government, various industry forums, and customers [

50,

51,

54,

55,

56,

59]. Partnerships are believed to provide organisations with better knowledge reserves, learning abilities, and dynamic capabilities in the new digital environment [

60]. However, developing and coordinating a successful strategic partnership is not simple and may require leaders to demonstrate a range of skills and attitudes, including developing effective communication and conflict resolution plans, expressing a commitment to reach win–win solutions, and sharing information.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

This paper integrates the concept of Construction 4.0 with the leadership competencies, and identifies the leadership competencies needed in the context of Construction 4.0 for all construction industry organisations through a focused review. Overall, 22 competencies have been identified through a focused review of 21 publications, which are grouped into four domains.

The cognitive domain, which includes seven competencies (tolerance of failure, purpose orientation, critical thinking, conveying messages, gathering information, learning agility, and acting ethically), refers to the basic competencies that provide guidance for leaders on the perception, thinking, and behaviour in the context of Construction 4.0. The competencies in this domain are closely related to, and form, the foundation for leaders to develop the competencies in other domains. ‘Tolerance of failure’ deserves more attention, as it may be a concept lacking in the construction industry. As mentioned earlier, the construction industry has a risk-aversion characteristic, which hinders digital transformation [

94,

95,

96]. Leaders should lead by example and have a failure-tolerant mindset, which can help organisations change directly and indirectly. In addition, the importance of ‘conveying messages’ and ‘gathering information’ should be emphasised. Although these two competencies have been extensively highlighted in previous research, traditional approaches may not be sufficient to support construction leaders in delivering and gathering information in the context of Construction 4.0. Leaders should be aware of the changes brought about by new technologies and concepts in society (such as the value of social platforms in transmitting and collecting information), and abandon old-fashioned thinking to better help organisations embrace the digital age [

51,

69,

70,

79].

The interpersonal domain, which has five competencies (social perceptiveness/awareness, encouragement, persuasion, collaboration, and trust-building), relates to how leaders interact with other individuals. Although none of these competencies are new in the leadership research, the digital age places new standards of these competencies. For example, leaders should have greater social awareness, encouragement, persuasion, and trust-building competencies than usual, as leaders have a high probability of interacting with a wider range of stakeholders in the digital age; they should also have rational and proficient use of digital collaboration technologies to facilitate cross-organisational collaboration [

45,

51].

The business domain includes five competencies (financial management, talent management, resource allocation, empowerment, and team building and coordination), which are considered to be the business competencies that construction leaders should have in the Construction 4.0 era, providing leaders with the capability to effectively plan, adjust, and guide the management actions of construction organisations. In this domain, the ‘talent management’ competency is what should be re-emphasised in this research. In the era of Construction 4.0, one of the main challenges facing the construction industry is the changing skill requirements of practitioners. This may be very different from the previous requirements for leaders in human resource management capabilities. Leaders should have a stronger competency to identify skills that apply to organisational needs and select or develop suitable talents to meet the transformation needs [

95].

The strategic domain includes five competencies: visioning, environmental scanning, strategic plan development and appraisal, digital literacy, and partnership development and coordination. These competencies are crucial for organisational leaders, especially senior leaders, because they provide the ability to plan an appropriate future and develop sound strategies for the organisation. Although these leadership competencies are highly conceptualised, leaders in the Construction 4.0 era are considered to need to develop, enhance, and master these competencies. Moreover, digital literacy is a new leadership competency requirement that is identified in the Construction 4.0 era, yet few studies have discussed this competency in the previous research. In the context of Construction 4.0, the increasing importance of leaders’ digital literacy is identified in this study. This competency provides leaders with a good understanding of digital technologies (including the technology trends), which potentially support leaders in many management actions (making decisions, developing strategies, and embedding the technology into the operational framework) in the digital age [

15]. Past management research indicates that digital literacy, as a technical skill, is not critical for senior leaders, but this may not be the case in Construction 4.0 where leaders should have adequate digital literacy to see the potential of technologies on transforming organisational practices [

43].

The result of this research has both theoretical contributions and practical implications. Theoretically, this research re-examines the existing Construction 4.0 leadership-related papers and clarifies the competencies mentioned by the previous research. Through redefining and explaining each competency, the research is believed to provide the theoretical guidance for subsequent leadership research in Construction 4.0. Moreover, during the literature review, it was found that the needs for leadership are clearly mentioned in many publications, even though it was sometimes described using different words, such as senior management support and management awareness, which is argued as an important factor for promoting digital transformation and technology adoption [

19]. This article provides a view that leadership has multiple dimensions and influences the digital transformation and development of construction organisations in various ways.

Practically, the research provides clear guidance for construction leaders to lead effectively in the era of Construction 4.0. From the most basic cognitive competencies, to interpersonal and business competencies, and to strategic competencies related to the organisation’s future planning, it provides a general leadership competency development reference for both human resources professionals and leaders in the construction industry. Construction leaders with these competencies are considered to have a better chance than other leaders to lead the digital transformation of construction organisations and succeed in Construction 4.0. They will be better equipped to identify and address the challenges that construction organisations may face when embracing Construction 4.0, such as identifying relevant digital technologies, reducing resistance to organisational change, and reorganising structure of the organisation.

There are three suggestions made for future research. Firstly, future research may include an empirical investigation in the industry to validate the competencies identified in this research, or determining the importance of each competency. Secondly, the investigation of the relationships between the four domains or between each competency can also be considered as a future research aim, which can provide a fuller understanding of leadership in Construction 4.0. Thirdly, future research can also discuss how leadership influences the success of construction organisations in Construction 4.0 and may identify the relative importance of the competencies.

The study has three limitations. First, the competencies identified by the research do not take into account the influence of regions and different regional cultures on the application of the competencies. Second, although Scopus is a comprehensive database, retrieving papers from only one database may lead to the exclusion of relevant literature. The use of the backward snowballing method helps to address this problem to a certain degree. Finally, as research into leadership competencies in Construction 4.0 deepens, the key competencies identified in this study may change.