Abstract

Shared vision is deemed a crucial success factor in defining complex relationships among various stakeholders and their multidimensional objectives in megaprojects. However, the current research development and literature on shared vision in megaprojects remain unclear. In particular, the prerequisites of shared vision among stakeholders are infrequently investigated. This work demonstrates that the value co-creation process is an essential prerequisite for promoting shared vision between clients and contractors in megaprojects. Furthermore, it aims to explore the influences of the value co-creation process on shared vision in such megaprojects. Two hundred and eighty-two valid questionnaires were collected from respondents involved in megaprojects in China. The responses were analyzed using the partial least squares structural equation model. The results indicate that two of the four interaction aspects of the value co-creation process, namely dialogue and access, can positively improve shared vision in megaprojects, whereas risk assessment and transparency cannot. However, from the individual perspectives of clients and contractors, only dialogue has a positive effect on the shared vision of clients with contractors. In contrast, access is the only variable that exerts a positive influence on the shared vision of contractors with clients. These findings reveal a unique causal relationship between the value co-creation process and shared vision in megaprojects. This affords new insight on improving cooperation between clients and contractors in megaprojects by synchronizing their perceptions and interactions via the value co-creation process.

1. Introduction

Megaprojects have a profound effect on politics, economy, and public life [1]. Numerous megaproject tasks and procedures are exceedingly complex and dispersed [2,3]. Shenhar and Holzmann [4] revealed in the literature on project management that two of the three primary components of megaproject success are clear strategic vision and total alignment. In other words, the key factor of megaproject success is the clear and shared understanding of the vision among project stakeholders [5,6]. Although the foregoing may seem theoretically simple, attaining such understanding under practical situations in megaprojects is exigent. Considering the involvement of numerous stakeholders and their multi-dimensional ambitions [7], the implementation of megaprojects is full of conflicting expectations and requisites among project participants [3,8,9]. This situation typically leads to opportunism, delay, cost overrun, and even project failure [10]. Thus, the process of facilitating shared vision in megaprojects is important for both practical and theoretical reasons. Moreover, the available research papers and references on shared vision for project stakeholders pertaining to megaprojects are limited. The majority of studies relevant to stakeholders in megaprojects focus on resolving conflicts among involved entities [8,11]. However, conflict resolution does not imply that stakeholders can achieve a shared vision [12]. Accordingly, scholars have endeavored to promote common goals and collaborative actions among project stakeholders [4,5].

In this work, the authors demonstrate that the value co-creation process in megaprojects is an essential prerequisite for fostering shared vision. Value co-creation describes as an engagement method in which the key stakeholders collaborate and influence one another to create synergistic opportunities [13,14]. This can strengthen the exchange of strategic information [15], promote joint decision-making [16], and enhance explorative learning among project actors [17]. In this process, under the value co-creation paradigm (hereinafter referred to as “value co-creation process”), stakeholders in megaprojects can deploy a new approach to collaboration and teamwork, assuming a “one-unit” mindset, namely a shared vision. More specifically, the stakeholders are unified by a shared understanding of purpose, as opposed to the typical fragmented and adversarial practices in megaprojects [11]. Previous studies have also supported this finding. For example, Eigeles [18] suggested that by creating an atmosphere that fosters openness, collaboration, and effective communication, shared vision may be facilitated. Green and Sergeeva [19] explain that value creation in projects has changed to “soft” value management and focuses mostly on creating a shared understanding of the value criteria associated with unique projects. Rojas et al. [15] further noted that the value co-creation process might actively and reciprocally address complicated challenges, exchange important and essential information, and achieve agreed objectives. The above studies all imply that value co-creation process may potentially facilitate shared vision.

Hence, this study aims to explore the influence of the value co-creation process on shared vision in megaprojects. First, a well-established framework was adopted for quantifying the value co-creation process reported in the marketing literature, specifically, on the established DART model from Prahalad and Ramaswamy [20], which represents dialogue, access, risk assessment, and transparency. Second, using the framework, the research compared the impact of the value co-creation process on shared vision in megaprojects from the viewpoints of clients and contractors by separating their data into two subsamples. In order to facilitate shared vision in megaprojects, the findings rendered insightful references for selecting the main interaction aspects of the value co-creation process.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Firstly, the theoretical background and hypothesis development that guided the study is provided. Then the research design of the study is explained, followed by the presentation of results. Finally, the discussion and conclusion of the research are presented, including limitations of the research.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. What Is Megaproject Management?

Megaprojects are complex undertakings, they are large-scale projects that often cost a lot of money, have high-level innovations and significant social importance, and cover a long time span [21]. Although numerous authors have set USD 1 billion as the investment threshold for megaprojects [1,22], a few scholars maintain that such a limiting amount cannot be regarded as a criterion in defining megaprojects [21,23]. For example, according to Pollack et al. [24], the true characteristics are organizational complexity, uncertainty, ambition, politics, and risk rather than cost immensity. In view of this, a certain percentage of a country’s gross domestic product was suggested as a reasonable criterion to replace the USD 1 billion threshold [23]. Thus, in the current work, the adopted working definition for megaprojects is “complex undertaking, large-scale and strong symbolic significance projects, with a substantial budget or a specific share of a country’s GDP that involves multiple stakeholders in a long time span”.

Megaprojects have different managerial approaches [1]. Traditionally, the majority of construction projects have been completed through the design–bid–build delivery method. However, the adoption of different techniques in megaprojects has increased to cope with the high level of project complexities and uncertainties [6], such as public–private partnership (PPP) arrangements. Modern techniques have collaborative advantages when the distance between the client and contractor is reduced [25] and joint problem-solving and co-development are enhanced [26]. Thus, such techniques could “co-create” the added value as compared with the conventional project delivery [15].

2.2. Value and Stakeholders in Megaproject Research

Value in megaprojects is created by participating actors [27] and may be described as a perceived and valued benefit of the megaproject by stakeholders [28]. As implied by the definition, value is a multifaceted concept that includes tangible (e.g., pecuniary value) [27] and intangible (e.g., long-term societal benefits, valuable relationships, knowledge, and public value) values [29]. In other words, the concept of value encompasses numerous elements beyond the typical economic viewpoint. It consists of social and environmental elements, intangible deliverables, and valuable relationships and knowledge. Moreover, value is a subjective concept [13,28]; it is not absolute [29]. That is, stakeholders see the resulting value differently due to their diverse (and often competing) interests and objectives [9,11,30]. However, this cannot be universally understood in the same way. Thus, a thorough understanding of value must take into account the viewpoints of different stakeholders.

Stakeholders in a project are typically individuals, groups, and organizations who are affected directly in the project. They may also perceive that the project’s outcomes will affect them. To date, several models and frameworks have been formulated to categorize project stakeholders with respect to their attributes. For example, classification was proposed according to the influence of stakeholders on projects [31], namely internal and external groups of stakeholders. By referring to a three-attribute model (power, legitimacy, and urgency), the typology of stakeholders can be identified by their attributes [32]. However, Kujala et al. [33] note that the three-attribute model has limitations because salient stakeholders change over time and vary across project types. Similar to the study of [31], in this work, the stakeholders are categorized according to their impact on megaprojects. Internal stakeholders, like financiers, clients, suppliers, and contractors are deemed as impacting the process and product. External stakeholders, including citizens, local authorities, public, and non-profit organizations, impact the social and ecological aspects of megaprojects. By considering the exploration of this preliminary research, focus is set on internal stakeholders who directly contribute to the planning and implementation of megaprojects and constitute the core of project management [34]. Internal stakeholders have two major categories: clients/owners on the demand side (e.g., financiers, sponsors, clients’ customers, and clients’ owners) and contractors on the supply side (e.g., principal contractors, first-tier contractors, second-tier consultants, and professional service providers) [35]. Thus, this scoping study encompasses the client and contractor groups in the context of megaprojects.

2.3. Value Co-Creation Process in Megaproject Research

Typically, the process involving value co-creation can be explained as a joint process in creating value generally [36], but in the context of project and construction management, no common definition has been agreed upon. Recently, projects have been re-conceptualized as value co-creation processes for numerous actors [13] and have been well-reported in the megaproject management literature. According to [13,14], value co-creation is a stakeholder engagement process, where stakeholders collaborate to create synergies. In view of this, co-creation occurs through interactions and involves joint action in the megaproject context [30]. Furthermore, the value co-creation process can be treated as a routine, where multiple stakeholders cooperate and work together for successful project completion. Thus, based on the concept of multifaceted value and the interactive nature of co-creation, the value co-creation process in megaprojects can be described as an approach in which the client and contractor produce and maximize amicable outcomes for all stakeholders through resource sharing and effective interactions.

In the construction industry, no widely acknowledged method for quantifying the value co-creation process has yet been found. Although Rojas et al. [15] identified three fundamental drivers (i.e., relational engagement, cooperation, and innovativeness) substantiating the value co-creation process from the knowledge domain of project management, such an approach seems inappropriate for the current study owing to its focus on drivers rather than the composition of the value co-creation process. Vargo and Lusch [36] offered service-dominant logic (SDL) as the most prevalent concept in marketing literature for the understanding of value co-creation [37]. Meanwhile, the emerging concept of SDL provided the foundation for another fundamental element in clarifying the processes involved with value co-creation [38], namely the DART model. The DART model provides the details to clarify co-creation processes in terms of customers’ behavioral and cognitive processes. The interactive nature of clients and contractors has been considered in the value co-creation process in this study. This model, established by [20,38], is one of the most popular frameworks for conceptualizing and guiding value co-creation implementation [39]. Encompassing a holistic perspective, this model affords the quantification of the process of value co-creation through dialogue, access, risk assessment, and transparency. Thus, the model can serve as a more appropriate and useful option for this research.

2.4. Shared Vision in Megaproject Research

Vision is a concise and alluring description of a project’s outcome. It can be defined in terms that are universally comprehensible and imaginable [4]. Scholars have proposed several constructs similar to vision, including goal, expectation, ambition, and identity [22,40]. However, vision differs from these constructs. For instance, vision can reflect in a big picture of where people aspire to be, but the path is unknown. This is where goals, expectations, ambitions, and identities come into play [41]. In other words, vision must benefit all stakeholders and should be regarded as one of the most critical factors for a project’s long-term success [4].

The notion of shared vision has been well-established in the organizational field [42,43]. According to [12], this study defines shared vision as a shared collaboration effort and understanding from the key stakeholders in cooperating together to achieve project goals. In a nutshell, shared visions are generally created to inspire movement from the current condition to the intended end state. In other words, shared vision is a high-level term that incorporates both collaboration and cooperation in megaprojects [44] and implies a consistency of perspectives rather than single project goals.

At the simplest level, shared vision in megaprojects is the answer to the question “What do we want to create together?” More specifically, shared vision in the current study pertains to clients knowing what to expect, contractors knowing what they have to build, and both groups unambiguously working together on the project. Shared vision inspires clients and contractors to devote their best efforts. Although Shenhar and Holzmann [4] emphasize the importance of shared vision for megaprojects, the methods of promoting shared vision among project stakeholders have not been given sufficient attention. Accordingly, the current study attempts to address this gap by empirically establishing the hypothetical links between the value co-creation process and shared vision in megaprojects based on empirical evidence.

2.5. Hypothetical Relationships

First, the constructive interactivity and creation of shared meaning require dialogue instead of the traditional unidirectional flow of information [20,39]. Clients and contractors generally have different expectations of a megaproject, particularly when it is devoid of routine [28]. Hence, sustained dialogues between clients and contractors are necessary to allow both sides to actively engage in open and constructive communication and interaction. Andersen and Hovering [45] identified stakeholder dialogue as the optimal method for avoiding and resolving any allegations of dishonesty. Such a communication process aids in resolving common problems and eliminating confusion as well as possible conflicts, thus establishing accountability in the process [46]. As a result, the development of shared language and common understanding between clients and contractors is facilitated. Furthermore, with constructive interaction, the two sides are able to better clarify the vision in terms of what they can and must do in the megaproject. In other words, frequent dialogues increase the amount of information available, facilitating the advance of shared vision.

Second, access pertains to the accessibility of processes, resources, information, tools, and assets to clients or contractors that can be used across megaprojects [20,38,39]. Access and connectivity provide partners with internal resources, tools, and procedures that promote a more evocative interchange of information and ideas and enhance their ability to predict and make decisions. Moreover, in contrast to partners who are not active in the value creation process, providing information on the actual status of the project contributes significantly to building trust between clients and contractors [47], leading to a more qualified partnership [16]. Such partnership generates opportunities for common understanding. This means that access enhances the relationships between the two actors, considerably reducing differences and developing a shared understanding of specific goals.

Third, risk assessment pertains to either clients or contractors providing their partners with accurate information on potential threats [20,39], such as environmental [47], dependency, regulatory, and external risks [48]. As clients and contractors become value co-creators, both parties become increasingly sensitive to risk and desire greater information about the possible dangers associated with the project’s design, manufacture, and delivery. Megaprojects are generally understood to be fundamentally unpredictable [49]. They are unique and subject to uncertainty and complexity [9], which can lead to risk events [50]. When the information is incomplete and asymmetric, prolonged uncertainties can be detrimental to megaprojects [47]. Risk assessment can aid project stakeholders in improving preparations for megaprojects by conceiving alternatives and taking proactive action [50]. Risk assessment is plausibly a trust-creating maneuver that could facilitate value optimization in megaprojects. Compared with individually considering risks and benefits, risk assessment affords clients and contractors an opportunity to evaluate the advantages and disadvantages associated with their decisions supported by routines. Hence, instead of transferring or ignoring risks, these can be effectively managed and the potential benefits behind them may be explored [47]. Moreover, proactive risk communication and management establish a trustworthy relationship between clients and contractors. Solutions can be formulated, and accountability may be established, thus overcoming disagreement and offering incentives to inspire a shared vision.

Fourth, transparency represents the proactive willingness to share important particulars to mitigate information asymmetry between clients and contractors [20,38,39]. Lee et al. [51] state that conflicts in projects usually arise because of non-transparency, including a lack of information sharing. Interaction only becomes successful if a company’s details are transparent to its partners because information asymmetry between clients and contractors enables opportunistic behaviors. Transparency is the key to building trustworthy cooperation between clients and contractors. Transparent communication drives collaboration and cooperation rather than competition and rivalry, and both client and contractor can freely exchange information for the benefit of the overall project rather than focusing on their individual benefits or losses. All of this serves as a basis for secure and committed relationships; it consolidates bonds and connections, which are paramount to the shared understanding of a megaproject’s vision.

The following hypotheses are proposed on the basis of the foregoing postulations:

Hypothesis 1:

Dialogue is positively associated with shared vision between clients and contractors in megaprojects.

Hypothesis 2:

Access is positively associated with shared vision between clients and contractors in megaprojects.

Hypothesis 3:

Risk assessment is positively associated with shared vision between clients and contractors in megaprojects.

Hypothesis 4:

Transparency is positively associated with shared vision between clients and contractors in megaprojects.

3. Research Design

3.1. Measurements

The measurements employed in the study were adapted from previous research and modified to satisfy the research objectives and context. The DART model’s four interaction aspects have been used in the measurement of the value co-creation process. The three-item scale of Li and Lin [52] was modified to measure shared vision. In addition, several control variables were used in this study, including age, working experience, and job position.

The language of questionnaire was translated into Chinese to suit the research scope and the subject of megaprojects in China. Items in the questionnaire were designed using the five-scale of Likert agreements. Before initiating formal data collection, the scales were extensively pre-tested among practical executives in the construction industry to check their applicability and clarity. Then, the scales were modified and refined accordingly.

3.2. Sampling and Data Collection

China is undergoing its largest investment boom in infrastructure [53]; hence, the scope of sample data is derived from Chinese megaprojects, which could provide considerable first-hand data for empirical investigation [54]. Chinese megaprojects can also serve as important references for theoretical research, even in a global context [55]. Similar to megaprojects in developed countries, those in developing countries, such as China, also encounter comparable problems (e.g., cost overruns, safety incidents, and quality defects) [23]. Thus, megaproject management is a worldwide issue common to both developed and developing countries [22]. Megaprojects qualifying one of the following criteria were selected: (a) complex undertaking and large-scale projects that typically cost over USD 1 billion [22]; (b) cost over 0.01% of GDP [23].

To collect data, the snowball sampling method, which has been extensively applied to megaprojects as documented in the literature [27,47], was used due to the following reasons: First, due to limited cases of megaprojects, probability sampling is not possible. Second, many potential participants are hesitant to take the time to fill out surveys or divulge their opinions over the phone or by email to an unknown interviewer. Because our key informants are almost top leaders in megaprojects, the problem is more serious in our study [12]. Snowball sampling provides a greater response rate and a cheaper cost than probability sampling for selecting participants [56]. As a result, in this investigation, the snowball sampling strategy is more beneficial and acceptable.

Several metrics were used in this study to elicit high-quality replies. First and foremost, all respondents were anonymous and voluntary; they were asked to respond according to their real working experience without concern for whether their response was correct or incorrect. Second, to conceal the real hypothesis, each participant was provided with a cover narrative. Third, the item “Are you familiar with the management process of the megaproject?” was added to determine if the responder had any expertise with project management methods. Only those who said “Yes” were kept in the study.

From March 2020 to July 2020, two rounds of data collecting were conducted using a selection of initial informants that was as varied as feasible. Initial contact was made with the client and contractor groups as found in the database center for megaprojects, namely http://www.mpcsc.org/ (accessed on 1 March 2020); with reference no. 57815192 as approved by the university. Then, each organization was asked to provide contact information for key project personnel as well as the key senior and middle managers who had worked or were working in it. Moreover, the graduates and acquaintances’ contact information were used to send exploratory emails to organizations involved in Chinese megaprojects in general. To encourage additional volunteers, a promise was made that they would receive a thorough summary of the findings after the research was completed. To discover more eligible participants, all qualifying participants were asked to distribute the survey link to their colleagues. Overall, 400 invitations were sent, and 332 valid questionnaires were received (147 from clients and 185 from contractors). After removing outliers and mismatched data, a sample of 141 matched client–contractor dyadic data points was finally obtained (see Table 1). Moreover, the two sources of responses were compared using analysis of variance; no statistically significant differences were found.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics.

After generating descriptive statistics, the partial least squares (PLS) structural equation modeling method was employed for the subsequent analysis. This technique can be effective for studies with the aim of theory development and prediction [57], particularly when the sample size is limited and the distribution is nonnormal [58]. Moreover, PLS-SEM is more likely to identify relationships as significant when they are indeed present in the population [59].

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

According to Hair et al. [60], Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability (CR), factor loadings, and average variance extracted (AVE) were used to assess the reliability and validity [60]. Table 2 and Table 3 summarize the results, implying the measurement model in this study has a good reliability and validity. In terms of multicollinearity through the variation inflation factor, each construct was well below five [60]. It can be concluded that multicollinearity is not a concern in the study. Moreover, although the paired survey from client companies and their respective contractors can mitigate the effect of the single-source related common method, the procedure proposed by Liang et al. [61] was also used to assess the possible common method variance (CMV). The results showed that most factor loadings were not significant, and the ratio of substantive variance to method variance was infrequently small at 294 (0.660):1 (0.002). Harman’s single-factor test was also conducted, and the result also verified CMV is not a problem in this study.

Table 2.

Outer model results.

Table 3.

Correlation matrix.

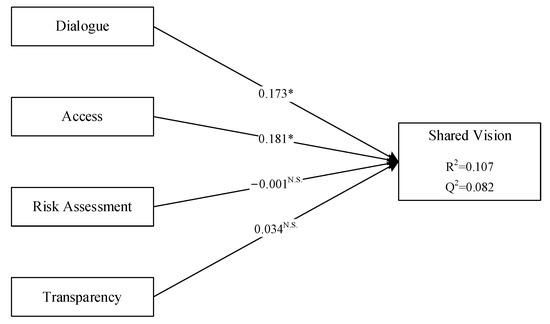

4.2. Structural Model

The structural model is mainly assessed by the coefficient of determination (R2), predictive relevance (Q2), and significance of path coefficients. The path coefficients and their significance were calculated by bootstrapping aided by SmartPLS v3.2.6 based on 282 cases and 5000 subsamples. The results of the structural model are converted to significance levels with p-values, as shown in Figure 1. The structural model accounted for 10.7% of shared vision variance. According to [62], a low R2 of at least 0.1 is acceptable on the condition that some or most of the predictors or explanatory variables are statistically significant, indicating that R2 in the current study achieved an acceptable level; in contrast, Stone–Geisser’s Q2 was above zero. Therefore, the structural model may also be assumed to have predictive accuracy and relevance. Based on the significance of path coefficients, the conclusion is that only H1 and H2 are supported; that is, dialogue (βDI = 0.173, ρ < 0.05) and access (βAC = 0.181, ρ < 0.05) have positive effects on shared vision in megaprojects. However, Figure 1 shows that risk assessment and transparency have no statistically significant effect on shared vision; thus, H3 and H4 are not supported. In addition, the path coefficients of control variables are all insignificant, implying that control variables do not exert significant effect on shared vision.

Figure 1.

Results of structural model. Note: * is significant at * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001; N.S. = non-significant.

4.3. Individual Analysis for Clients and Contractors*

Although both clients and contractors are involved in the value co-creation process, their perceptions may differ. To determine the explicit differences between the two, the data of the client and contractor groups were separated, and the path coefficients of both subsamples were estimated by the PLS. The results are summarized in Table 4. Surprisingly, the results differed. For the clients, dialogue had a positive effect on shared vision (βDI = 0.274, ρ < 0.05), whereas access had none (βAC = 0.126, ρ > 0.05). In contrast, for the contractors, dialogue had no significant impact on shared vision (βDI = 0.044, ρ > 0.05), whereas the influence of access was more significant (βAC = 0.243, ρ < 0.05).

Table 4.

Results of individual perspectives.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Findings

This study explored how the DART interaction aspects of the value co-creation process influenced shared vision in megaprojects. First, H1 and H2 are found to be supported, indicating that dialogue and access can lead to shared vision between clients and contractors. In contrast, H3 and H4 are not supported, implying that risk assessment and transparency exert no significant effects on shared vision. This may be due to the lengthy periods of engagement and extra costs. Long commitments may cause apprehension between clients and contractors; hence, they may desire to reduce risk in the value propositions from the complex and long-life cycle nature of megaprojects. Although participants in megaprojects presume that all risks from each process should be eliminated, such a viewpoint is unrealistic. Risk assessment can indefinitely continue because megaprojects are complicated and long term. This can incur extra cost that requires budget, making it problematic to establish shared vision among clients and contractors. Even worse, when changes are extremely difficult or considerably expensive to resolve, risk assessment loses significance. It becomes a waste of time because only a few of the measures considered in the risk assessment discussion are actually implemented. Furthermore, long-term relationships may be damaged as the intrinsic commitment between clients and contractors is reduced. The benefits of freely sharing information, i.e., transparency, has been emphasized as a way of promoting trust and collective responsibility in megaprojects [63]; however, transparency also has its “dark side”. Specifically, excessive information sharing can lead to information overload, making agreement among parties more difficult to achieve. Moreover, transparency may cause the parties, especially contractors, to become wary of endangering their market positions and business models.

Contrasting findings were found between the perspectives of clients and contractors with regard to hypotheses H1 and H2. For clients, the results did not support H2; in this group, the positive effect of access on shared vision was not significant. This may be because access could undermine the notions of openness and ownership. From the perspective of clients, the connectivity or access to internal resources may mean excessively empowering contractors. Specifically, clients could become aware of the uncertainty involved, including the risk that the contractors would not abide by professional ethics. As project stakeholders are likely to work together for the first time, their relationships may be terminated once the project has been completed, and the connectivity or access to internal resources may lead to value co-destruction [64]. More than that, there is a fact that may explain the findings that megaprojects have complex contractual arrangements and supply chains among project stakeholders [65], whereas clients may lack experience and appropriate human resources to handle such a large project [66]. Additionally, during the whole life-cycle, the negotiation and signing of the contract are commonly the most important for clients. Clients are amazed when they find the promises contractors have made can’t be delivered. Such pressure may lead to cost or time overrun for the contractors. Fake information may be used by contractors to mislead clients. All of these will hinder the shaping of clients’ shared vision with contractors.

In contrast, the contractors’ non-support of H1 suggests that dialogue is not perceived as useful in this research context. The reason may lie in the different perceptions of contractors of success. Contractors typically differentiate their value from the project value, seeing themselves as responsible for the former but absolved of responsibility for the latter. In other words, contractors frequently use their own objectives and business interests as primary drivers in megaprojects. More than that, the number of dependencies in megaprojects is substantially bigger than in regular structures [67]. Many entities participating in megaproject construction have a multilayered organizational structure. There is rarely an option to circumvent the levels, and because many contractors work to their own specific plans, there are a large number of dependencies, providing a complicated image to present. Thus, from the perspective of contractors, dialogue may not be that effective in facilitating shared vision in megaprojects. In a word, not all contractors can benefit from the constructive dialogues with clients in a complex setting of communication and relationships in megaprojects. Consequently, this viewpoint may retard dialogues and make it difficult for contractors to build a shared vision.

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

This work has investigated the interaction aspects of the value co-creation process toward shared vision from the perspectives of client and contractor organizations involved in megaprojects. It has two theoretical contributions to the literature. First, it enriches the literature on the value co-creation process in megaprojects and reports new insights into the processes involved in value co-creation by applying the DART model in the complex context of megaprojects. Although previous research has endeavored to conceptualize the value co-creation process for various stakeholders [13], the efforts that have been devoted to explicating the components of the process are inconsequential. This study clarifies the interaction aspects of the value co-creation process and confirms that only dialogue and access can promote shared vision in megaprojects. Second, this paper reports the first empirically driven results derived through a quantitative research approach, revealing the causal relationship between the value co-creation process and shared vision in megaprojects. This generalizable finding affords new insights into the effective interaction and cooperation for the key project stakeholders, particularly into the causality of the value co-creation process between the two groups to achieve shared vision. That is, the uncovered differences require specific attention in stakeholder management and analysis.

5.3. Practical and Managerial Implications

This research presents managerial implications for managers from both clients or contractors’ perspectives, to launch the value co-creation process and build shared vision in megaprojects. First, dialogue is linked to a higher likelihood of shared vision. As a result, megaproject managers should be aware that excellent communication and engagement with contractors are critical to project success. The first stage is to develop stories, identify common goals, and involve stakeholders with the shared understanding for the improved engagement and communication [68]. However, the goal is to build a shared vision, which is accomplished by the project team communicating amongst themselves. Establishing constructive communication platforms and developing procedural requirements and their style of operation are examples of such approaches. Specifically, managers of clients should, in particular, simplify organizational structures to increase communication efficiency, minimizing challenges such as coordination between front and back offices and miscommunication owing to the large number of communication channels.

Second, our findings show that in megaprojects, access and connectivity to internal resources, tools, and mechanisms are critical, particularly for contractors’ management. The contractor has knowledge, abilities, and skills that the client does not have in-house, and can deliver those services to the client, proving the competence and trustworthiness that makes it a client-wanted organization. Contractors benefit most from having better access to clients and being able to customize their services to meet their needs. Contractors and clients can work together to solve complicated challenges and build plans, policies, or sustainability standards by providing clear and accessible information. Furthermore, numerous technologies, like as BIM and blockchain, should be utilized to offer faster and easier access to the most relevant and up-to-date information [69]. For example, combining BIM and blockchain will enable large volumes of data to be collected from various sources [70], which can be presented to stakeholders in a dashboard format, and securely shared between them to ensure the reliable and easily accessible information.

5.4. Limitations and Future Directions

Some limitations need to be taken into account in this study. First, because this work only considered megaprojects in China, the generalizability of the findings and conclusions should be interpreted with caution. Future studies can broaden the samples and explore cultures and the specific phases of megaprojects, particularly at the post completion stage and their impact to verify and reinforce the findings of this research. Second, although the R2 is acceptable in the current study but relatively small and the viewpoints of clients and contractors have been found to differ, the causes have not been fully explored. Future studies should examine potential influencing factors, such as unequal organizational power, distrust, and corruption as well as investigate the potential interactive effects of dialogue, access, risk assessment, and transparency. Third, this research has only focused on two key stakeholder groups: clients and contractors. Hence, the results may not be applicable to external stakeholders. Research must be extended to involve other stakeholder groups in megaprojects to examine the value co-creation process among multiple stakeholders. For example, the investigation may involve the implementation of a social network analysis approach to determine the attributes salient to other stakeholders. Fourth, note that the cluster of stakeholders in a project is not static; it can change over the project’s life cycle. For future studies, longitudinal research may afford abundant information, especially when considering other procurement systems. Last but not least, certain reservations regarding the sampling strategy may persist. Future studies might use a random sample method to reduce bias (e.g., observation, document analysis, interviewing).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.X. and M.C.; methodology, Y.X. and M.C.; software, M.C.; validation, M.C.; formal analysis, Y.X., M.C. and H.-y.C.; investigation, Y.X. and M.C.; resources, M.C. and H.-y.C.; data curation, Y.X. and M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.X. and M.C.; writing—review and editing, Y.X. and M.C.; visualization, M.C.; supervision, H.-y.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 72201081).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to restrictions, e.g., privacy or ethical. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and anonymity of respondents.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Yuan, H.; Du, W.; Wang, Z.; Song, X. Megaproject management research: The status quo and future directions. Buildings 2021, 11, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadorestani, A.; Karlsen, J.T.; Farimaniv, N.M. Novel approach to satisfy stakeholders in megaprojects: Balancing mutual values. J. Manag. Eng. 2020, 36, 4019047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorod, A.; Hallo, L.; Statsenko, L.; Nguyen, T.; Chileshe, N. Integrating hierarchical and network centric management approaches in construction megaprojects using a holonic methodology. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2021, 28, 627–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenhar, A.; Holzmann, V. The three secrets of megaproject success: Clear strategic vision, total alignment, and adapting to complexity. Proj. Manag. J. 2017, 48, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K. A method to measure success dimensions relating to individual stakeholder groups. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2016, 34, 480–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenoy, D.; Mahanty, B. Measuring the readiness of a megaproject. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2021, 14, 999–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Wang, Z.; Skibniewski, M.J.; Ding, J.; Wang, G.; He, Q. Investigating stewardship behavior in megaprojects: An exploratory analysis. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2021, 28, 2570–2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadorestani, A.; Naderpajouh, N.; Sadiq, R. Planning for sustainable stakeholder engagement based on the assessment of conflicting interests in projects. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 242, 118402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Shen, G.Q.; Yang, R.J.; Zafar, I.; Ekanayake, E.M.A.C. Dynamic network analysis of stakeholder conflicts in megaprojects: Sixteen-year case of Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macao bridge. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, 04020103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.J.; Jayasuriya, S.; Gunarathna, C.; Arashpour, M.; Xue, X.; Zhang, G. The evolution of stakeholder management practices in Australian mega construction projects. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2018, 25, 690–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Shen, G.Q.; Yang, R.J.; Zafar, I.; Ekanayake, E.M.A.C.; Lin, X.; Darko, A. Influence of formal and informal stakeholder relationship on megaproject performance: A case of China. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2020, 27, 1505–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, M.; Chong, H.Y.; Xu, Y. The effects of shared vision on value co-creation in megaprojects: A multigroup analysis between clients and main contractors. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2022, 40, 218–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.; Chih, Y.Y.; Chew, E.; Pisarski, A. Reconceptualising mega project success in Australian Defence: Recognising the importance of value co-creation. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2013, 31, 1139–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, P.D. Creating and appropriating value from project management resource assets using an integrated systems approach. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 119, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, B.H.; Liu, L.; Lu, D. Moderated effect of value co-creation on project performance. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2018, 11, 854–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; van Marrewijk, A.; Houwing, E.J.; Hertogh, M. The co-creation of values-in-use at the front end of infrastructure development programs. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2019, 37, 684–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, P.E.; Leiringer, R.; Szentes, H. The role of co-creation in enhancing explorative and exploitative learning in project-based settings. Proj. Manag. J. 2017, 48, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eigeles, D. Facilitating shared vision in the organization. J. Eur. Ind. Train. 2003, 27, 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, S.D.; Sergeeva, N. Value creation in projects: Towards a narrative perspective. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2019, 37, 636–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. Co-creation experiences: The next practice in value creation. J. Interact. Mark. 2004, 18, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitsis, A.; Clegg, S.; Freeder, D.; Sankaran, S.; Burdon, S. Megaprojects redefined–complexity vs cost and social imperatives. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2018, 11, 7–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flyvbjerg, B.; Bruzelius, N.; Rothengatter, W. Megaprojects and Risk: An Anatomy of Ambition; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Chan, A.P.; Le, Y.; Jin, R.Z. From construction megaproject management to complex project management: Bibliographic analysis. J. Manag. Eng. 2015, 31, 04014052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollack, J.; Biesenthal, C.; Sankaran, S.; Clegg, S. Classics in megaproject management: A structured analysis of three major works. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2018, 36, 372–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabani Ardakani, S.; Nik-Bakht, M. Functional evaluation of change order and invoice management processes under different procurement strategies: Social network analysis approach. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2021, 147, 04020155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, P.E. Partnering in engineering projects: Four dimensions of supply chain integration. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2015, 21, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtinen, J.; Peltokorpi, A.; Artto, K. Megaprojects as organizational platforms and technology platforms for value creation. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2019, 37, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskerod, P.; Ang, K. Stakeholder value constructs in megaprojects: A long-term assessment case study. Proj. Manag. J. 2017, 48, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuorinen, L.; Martinsuo, M. Value-oriented stakeholder influence on infrastructure projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2019, 37, 750–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, H.; Lecoeuvre, L.; Vaesken, P. Co-creation of value and the project context: Towards application on the case of Hinkley Point C Nuclear Power Station. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2018, 36, 170–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winch, G.M. Managing Project Stakeholders; Morris, P.W.G., Pinto, J.K., Eds.; The Wiley Guide to Managing Projects; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; pp. 321–339. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, R.K.; Agle, B.R.; Wood, D.J. Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: Defining the principle of who and what really counts. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1997, 22, 853–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujala, J.; Lehtimäki, H.; Freeman, R.E. A stakeholder approach to value creation and leadership. In Leading Change in a Complex World: Transdisciplinary Perspectives; Kangas, A., Kujala, J., Heikkinen, A., Lönnqvist, A., Laihonen, H., Bethwaite, J., Eds.; Tampere University Press: Tampere, Finland, 2019; pp. 123–143. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, H.; Wang, D.; Yin, Y.; Liu, H.; Deng, B. Response of contractor behavior to hierarchical governance: Effects on the performance of mega-projects. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2021, 29, 1661–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliomogbe, G.O.; Smith, N.J. Value in megaprojects. Organ. Technol. Manag. Constr. Int. J. 2012, 4, 617–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Institutions and axioms: An extension and update of service-dominant logic. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2016, 44, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. Co-creating unique value with customers. Strategy Leadersh. 2004, 32, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albinsson, P.A.; Perera, B.Y.; Sautter, P.T. DART scale development: Diagnosing a firm’s readiness for strategic value co-creation. J. Market. Theory Pract. 2016, 24, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matinheikki, J.; Artto, K.; Peltokorpi, A.; Rajala, R. Managing inter-organizational networks for value creation in the front-end of projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2016, 34, 1226–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matinheikki, J.; Pesonen, T.; Artto, K.; Peltokorpi, A. New value creation in business networks: The role of collective action in constructing system-level goals. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2017, 67, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahapiet, J.; Ghoshal, S. Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 242–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Expósito-Langa, M.; Molina-Morales, F.X.; Tomás-Miquel, J.V. How shared vision moderates the effects of absorptive capacity and networking on clustered firms’ innovation. Scand. J. Manag. 2015, 31, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Locatelli, G.; Wan, J.; Li, Y.; Le, Y. Governing behavioral integration of top management team in megaprojects: A social capital perspective. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2021, 39, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, S.E.; Høvring, C.M. CSR stakeholder dialogue in disguise: Hypocrisy in story performances. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 114, 421–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.H.; Thomas Ng, S.; Skitmore, M. Modeling multi-stakeholder multi-objective decisions during public participation in major infrastructure and construction projects: A decision rule approach. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2016, 142, 04015087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Y. Impact of regulatory focus on uncertainty in megaprojects: Mediating role of trust and control. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, 04020142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Mufti, N.A.; Qaiser Saleem, M.; Hussain, A.; Lodhi, R.N.; Asad, R. Identification of factors affecting risk appetite of organizations in selection of mega construction projects. Buildings 2021, 12, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachbagauer, A.G.M.; Schirl-Boeck, I. Managing the unexpected in megaprojects: Riding the waves of resilience. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2019, 12, 694–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erol, H.; Dikmen, I.; Atasoy, G.; Birgonul, M.T. Exploring the relationship between complexity and risk in megaconstruction projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, 04020138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Won, J.W.; Jang, W.; Jung, W.; Han, S.H.; Kwak, Y.H. Social conflict management framework for project viability: Case studies from Korean megaprojects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2017, 35, 1683–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Lin, B. Accessing information sharing and information quality in supply chain management. Decis. Support Syst. 2006, 42, 1641–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansar, A.; Flyvbjerg, B.; Budzier, A.; Lunn, D. Does infrastructure investment lead to economic growth or economic fragility? Evidence from China. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy. 2016, 32, 360–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Sheng, Z. Infrastructure mega-project management on the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macao Bridge project. Front. Eng. Manag. 2018, 5, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Chen, X.; Wang, G.; Zhu, J.; Yang, D.; Liu, X.; Li, Y. Managing social responsibility for sustainability in megaprojects: An innovation transitions perspective on success. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 241, 118395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teddlie, C.; Yu, F. Mixed methods sampling: A typology with examples. J. Mix Methods Res. 2007, 1, 77–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Howard, M.C.; Nitzl, C. Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 109, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F., Jr.; Cheah, J.H.; Becker, J.M.; Ringle, C.M. How to specify, estimate, and validate higher-order constructs in PLS-SEM. Australas. Mark. J. 2019, 27, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Saraf, N.; Hu, Q.; Xue, Y. Assimilation of enterprise systems: The effect of institutional pressures and the mediating role of top management. MIS Q. 2007, 31, 59–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozili, P.K. The Acceptable R-Square in Empirical Modelling for Social Science Research. 2022. SSRN 4128165. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4128165 (accessed on 29 October 2022).

- Wu, G.; Li, H.; Wu, C.; Hu, Z. How different strengths of ties impact project performance in megaprojects: The mediating role of trust. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2020, 13, 889–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, M.; Smyth, H.; Davies, A. Co-creation of value outcomes: A client perspective on service provision in projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2019, 37, 696–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Ju, T.; Xia, B. Institutional pressures and megaproject social responsibility behavior: A conditional process model. Buildings 2021, 11, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iftikhar, R.; Müller, R.; Ahola, T. Crises and coping strategies in megaprojects: The case of the Islamabad–Rawalpindi Metro Bus Project in Pakistan. Proj. Manag. J. 2021, 52, 394–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodney Turner, J. Using Principal–Steward contracting and scenario planning to manage megaprojects. Proj. Manag. J. 2022, 53, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Wang, H.; Yu, D.; Ye, J. Sharp schedule compression in urgent emergency construction projects via activity crashing, substitution and overlapping: A case study of Huoshengshan and Leishenshan Hospital projects in Wuhan. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Chong, H.Y.; Chi, M. Blockchain in the AECO industry: Current status, key topics, and future research agenda. Autom. Constr. 2022, 134, 104101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, H.Y.; Diamantopoulos, A. Integrating advanced technologies to uphold security of payment: Data flow diagram. Autom. Constr. 2020, 114, 103158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).