Effects of Combined Cr, Mn, and Zr Additions on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Al–6Cu Alloys Under Various Heat Treatment Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Heat Treatment Conditions

2.3. Characterization of Microstructure

2.4. Mechanical Properties Test

3. Results

3.1. Microstructural Evolution

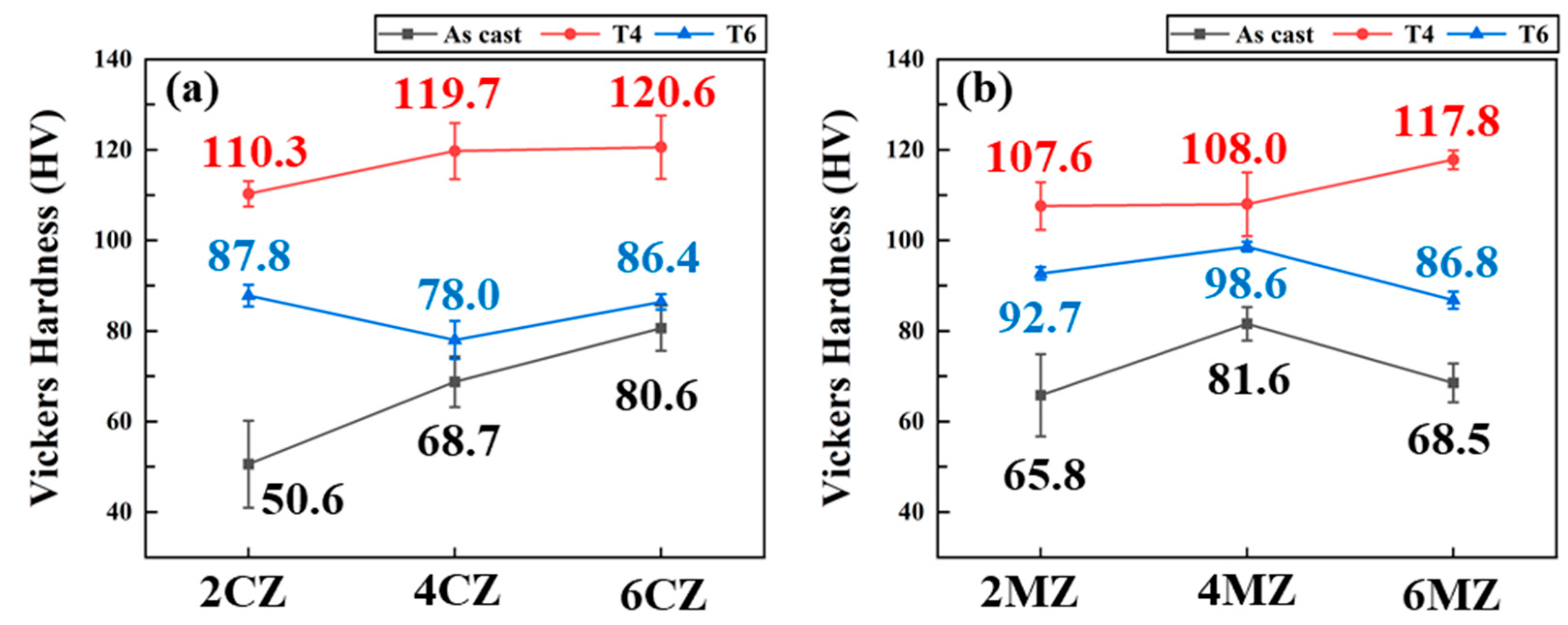

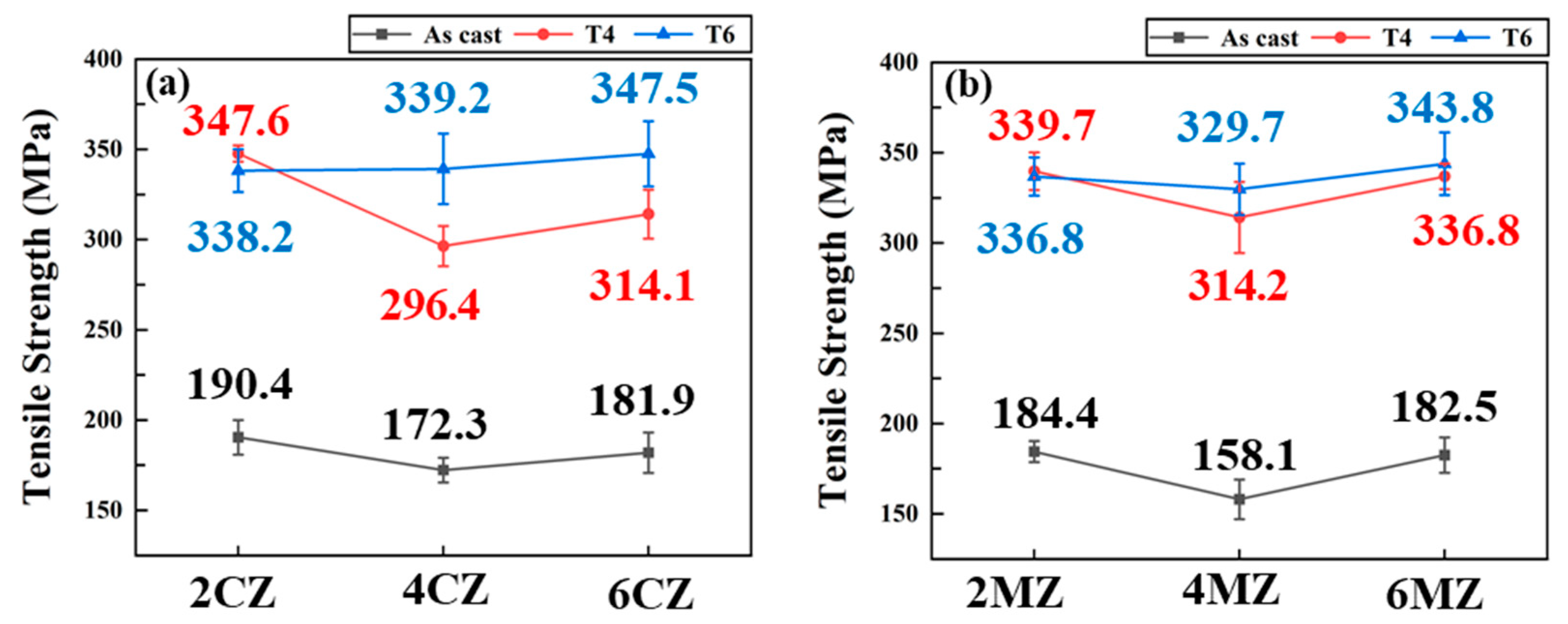

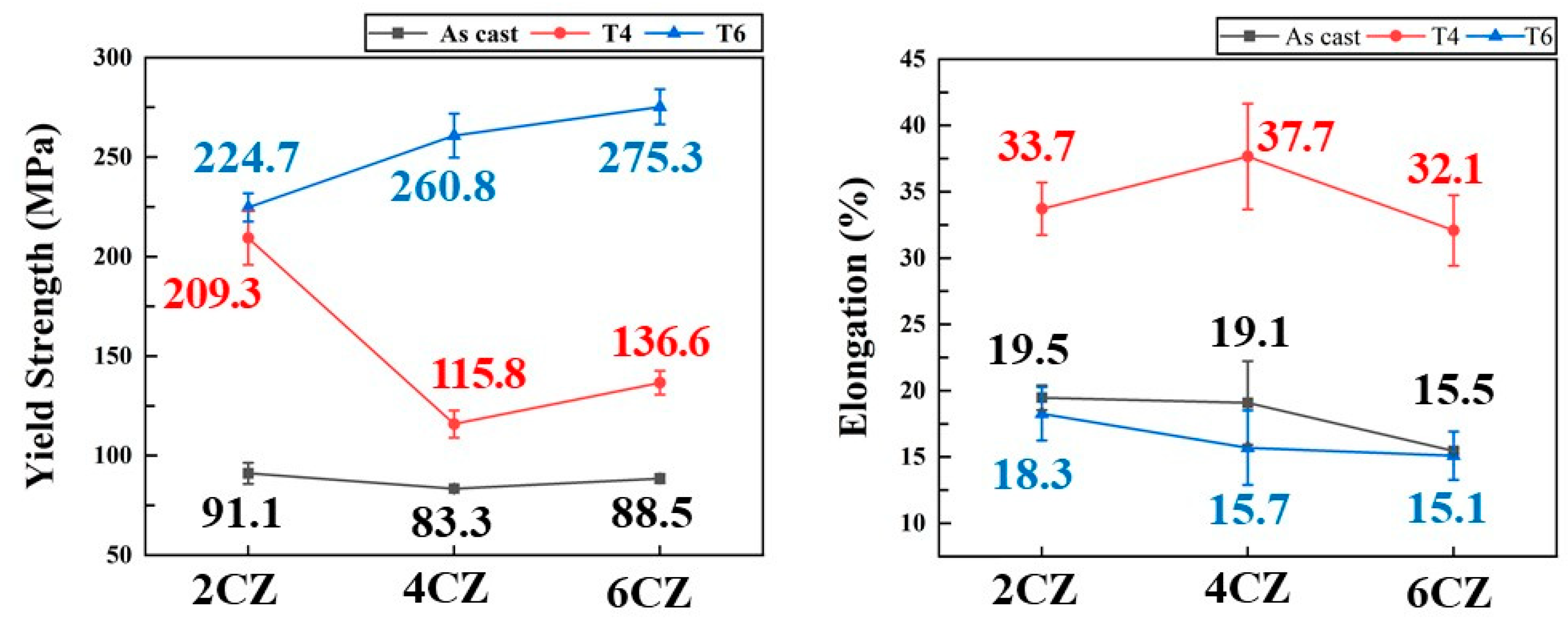

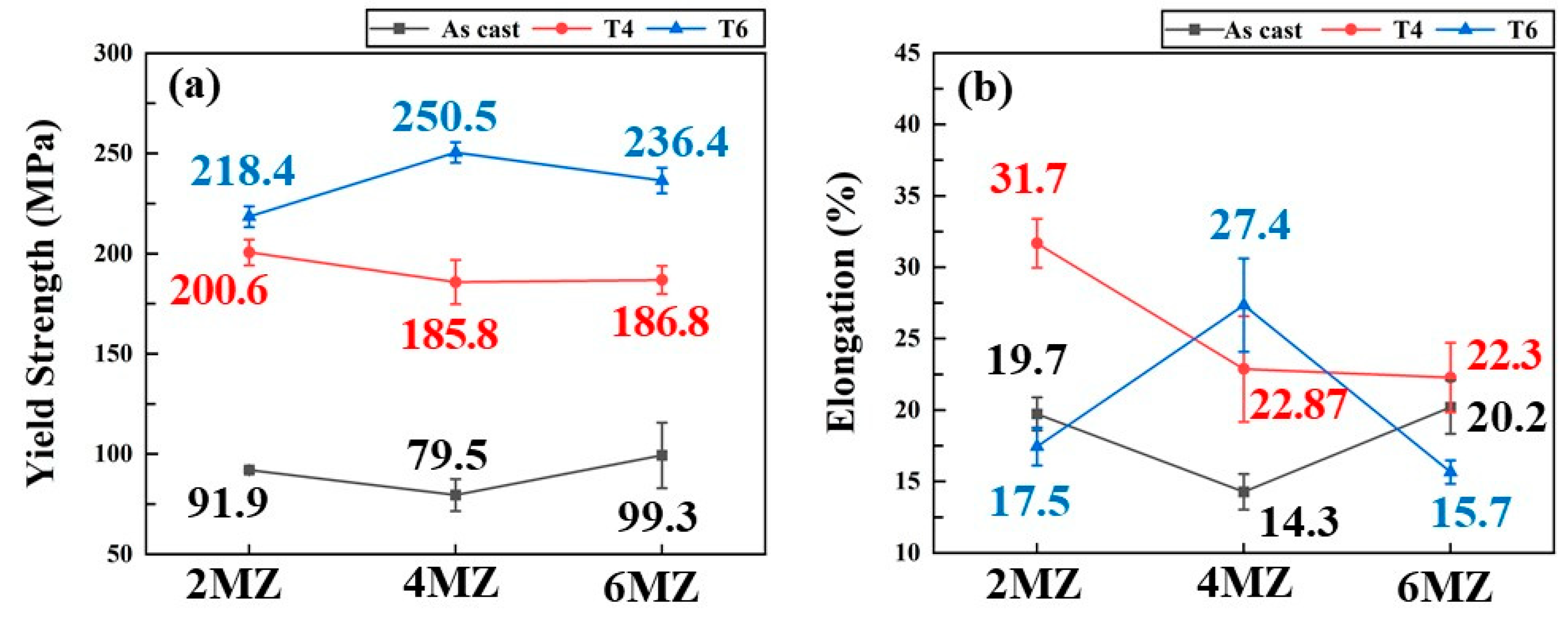

3.2. Mechanical Properties

4. Discussion

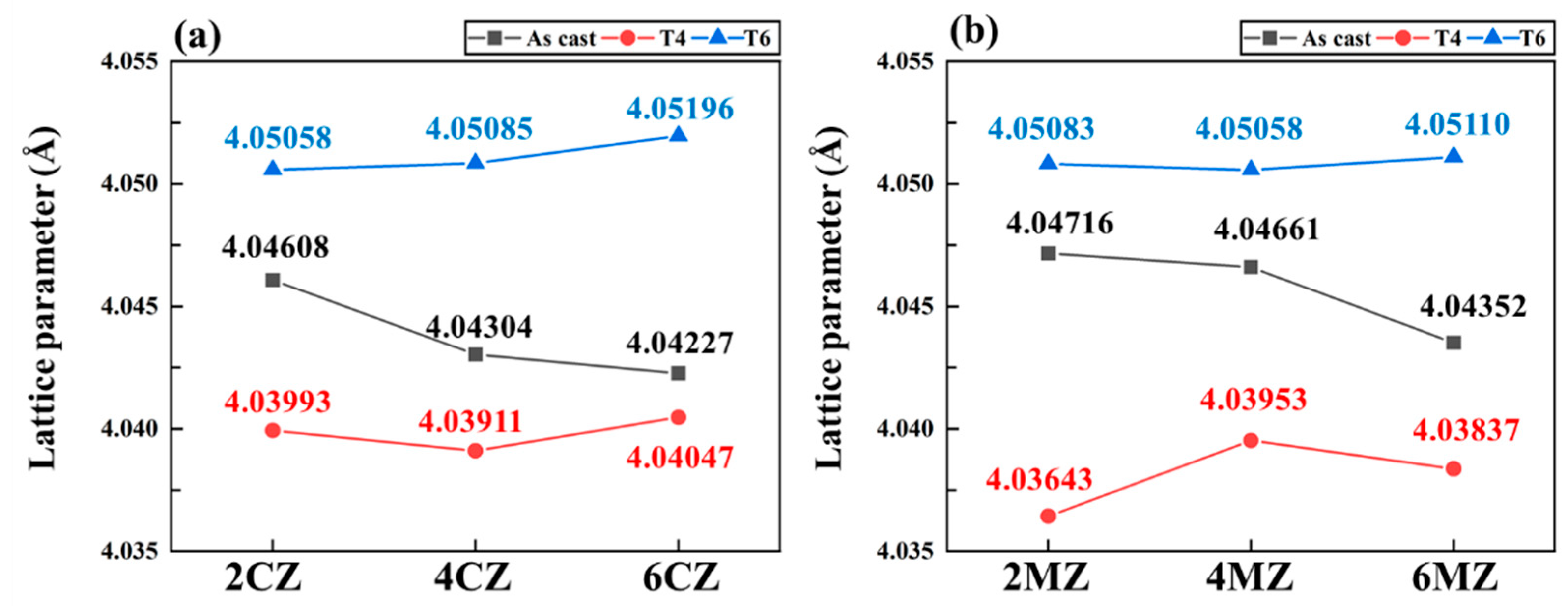

4.1. Correlation Between Lattice Parameter and Strengthening Mechanisms

4.2. Influence of Dislocation Density on Deformation Behavior

4.3. Effect of Precipitate Morphology on Ductility Degradation

4.4. Optimization of Mechanical Performance

5. Conclusions

- (1)

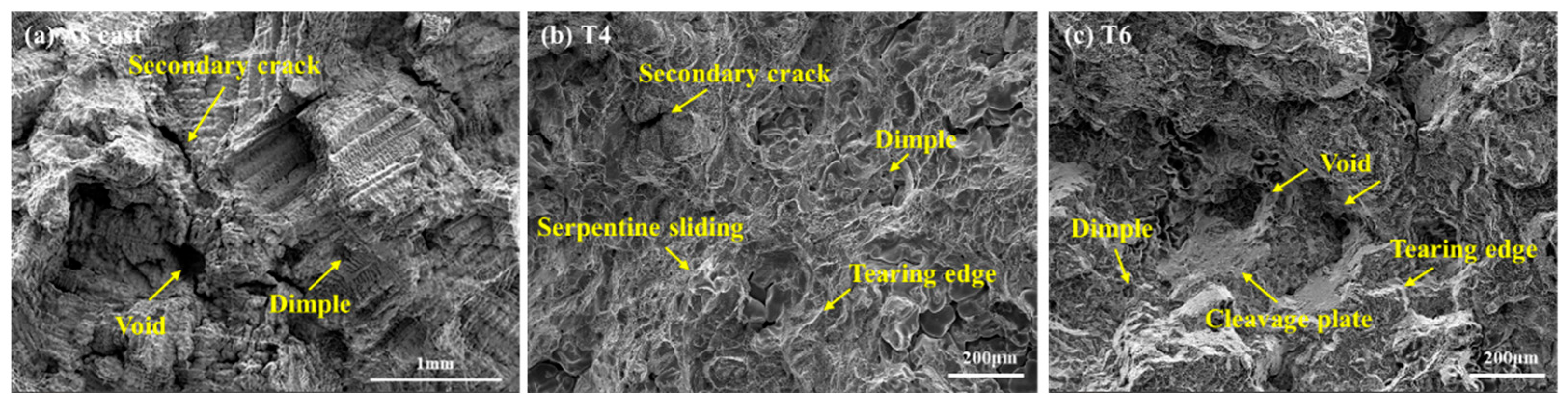

- In the as-cast state, the microstructure was characterized by a continuous network of coarse eutectic Al2Cu phases. The T4 heat treatment effectively fragmented and dissolved these coarse phases. During T6 artificial aging at 240 °C, the precipitation behavior varied by composition; notably, in the MZ combinations, EDS analysis confirmed the formation of Al–Cu–Fe–Mn intermetallic compounds, which were observed to grow into needle- and rod-like shapes morphologies during aging.

- (2)

- The micro-hardness in the T4 heat treatment condition was consistently higher than that in the T6 condition across all alloys. This trend is attributed to the relatively high aging temperature (240 °C), which likely induced an over-aging effect. This condition led to the coarsening of strengthening precipitates and a reduction in coherency strain, resulting in lower hardness compared to the T4 heat treatment state, where solid solution strengthening was maximized.

- (3)

- A distinct difference in tensile behavior was observed between the two alloy systems. The CZ series exhibited a typical trade-off where T6 aging increased strength but significantly reduced ductility. In contrast, the MZ series, particularly the 4MZ–T6 alloy, achieved a superior balance of mechanical properties (yield strength: 250.5 MPa; elongation: 27.4%). This indicates that the specific combination of Mn and Zr effectively enhances strength while maintaining high ductility.

- (4)

- XRD line-broadening analysis revealed that the T6 aging treatment induced lattice expansion, which necessitated a significant increase in dislocation density to accommodate the lattice misfit. This accumulation of defects contributed to the strengthening mechanism.

- (5)

- The study demonstrates that mechanical performance is dependent on the optimization of alloying elements and heat treatment conditions. The 4MZ–T6 condition emerged as the optimal processing route, demonstrating that controlling the precipitation of transition metal phases (such as Al–Cu–Fe–Mn) and managing dislocation density are critical strategies for the effective design of Al–Cu alloy systems.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moon, G.; Lee, E. Simultaneous refinement in θ’ precipitation and corrosion behavior of a 2xxx series Al–Cu alloys modified via the sole or joint addition of Cr, Mn and Zr. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 40, 109578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Xiao, Z.; Wen, J.; Wang, X.; Dai, Z.; Xiao, S. Investigation of the mechanical properties of TiC particle-reinforced Al–Cu alloys: Insights into interface precipitation mechanisms and strengthening effects. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 31, 1036–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Bellon, B.; Llorca, J. Multiscale modelling of the morphology and spatial distribution of θ’ precipitates in Al-Cu alloys. Acta Mater. 2017, 132, 611–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Ding, Q.; Liu, C.; Wang, J.; Tian, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z. Atomic-scale mechanism of the θ″ → θ′ phase transformation in Al-Cu alloys. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2017, 33, 1159–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Lei, Y.; Chen, Y.; Qu, H.; Qi, Z.; Zheng, G.; Liu, X.; Xiang, H.; Chen, G. Precipitating thermally reinforcement phase in aluminum alloys for enhanced strength at 400 °C. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2024, 172, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Ando, D.; Sutou, Y. Heat-resistant aluminum alloy design using explainable machine learning. Mater. Des. 2024, 243, 113057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oguocha, I.N.A.; Yannacopoulos, S. Precipitation and dissolution kinetics in Al–Cu–Mg–Fe–Ni alloy 2618 and Al–alumina particle metal matrix composite. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 1997, 231, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Z.; Dai, S.; Wu, L.; Chen, Z.; Wang, M.; Chen, D.; Wang, H. Thermal stability of Al–Fe–Ni alloy at high temperatures. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2019, 8, 2538–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Pan, Q.; Luo, Y.; Liu, S.; Wang, W.; Ye, J.; Shi, Y.; Huang, Z.; Xiang, S.; Liu, Y. The effects of scandium heterogeneous distribution on the precipitation behavior of Al3(Sc, Zr) in aluminum alloys. Mater. Charact. 2021, 174, 110971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuchariková, L.; Liptáková, T.; Tillová, E.; Kajánek, D.; Schmidová, E. Role of chemical composition in corrosion of aluminum alloys. Metals 2018, 8, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, J.; Wang, B.; Xue, C.; Liu, X. Quantifying the effects of Sc and Ag on the microstructure and mechanical properties of Al–Cu alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 831, 142355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Rouxel, B.; Langan, T.; Dorin, T. Coupled segregation mechanisms of Sc, Zr and Mn at θ′ interfaces enhances the strength and thermal stability of Al-Cu alloys. Acta Mater. 2021, 206, 116634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poplawsky, J.D.; Milligan, B.K.; Allard, L.F.; Shin, D.; Shower, P.; Chisholm, M.F.; Shyam, A. The synergistic role of Mn and Zr/Ti in producing θ′/L12 co-precipitates in AlCu alloys. Acta Mater. 2020, 194, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahl, S.; Xiong, L.; Allard, L.F.; Michi, R.A.; Poplawsky, J.D.; Chuang, A.C.; Singh, D.; Watkins, T.R.; Shin, D.; Haynes, J.A.; et al. Aging behavior and strengthening mechanisms of coarsening resistant metastable θ’precipitates in an Al–Cu alloy. Mater. Des. 2021, 198, 109378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahl, S.; Rakhmonov, J.U.; Kenel, C.; Dunand, D.C.; Shyam, A. Effect of grainboundary θ-Al2Cu precipitates on tensile and compressive creep properties of cast Al–Cu–Mn–Zr alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 840, 142946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shyam, A.; Roy, S.; Shin, D.; Poplawsky, J.D.; Allard, L.F.; Yamamoto, Y.; Morris, J.R.; Mazumder, B.; Idrobo, J.C.; Rodriguez, A.; et al. Elevated temperature microstructural stability in cast AlCuMnZr alloys through solute segregation. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 765, 138279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, G.; Lee, E. Enhancing thermal stability and strengthening mechanism of Al-Cu alloy via synergistic segregation of Cr, Mn, and Zr at Al/θ′ interface. Mater. Des. 2025, 257, 114454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM E8/E8M-22; Standard Test Methods for Tension Testing of Metallic Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2016.

- Zhou, L.; Wu, C.L.; Xie, P.; Niu, F.J.; Ming, W.Q.; Du, K.; Chen, J.H. A hidden precipitation of the θ′-phase in Al-Cu alloys. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021, 75, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; He, W.; Medina, J.; Song, D.; Sun, Z.; Xue, Y.; Gonzalez-Doncel, G.; Fernandez, R. Contribution of the Fe-rich phase particles to the high temperature mechanical behavior of an Al-Cu-Fe alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 973, 172866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Qi, N.; Li, Y.; Gu, Y.; Zhan, X. Research on the cryogenic axial tensile fracture mechanism for 2219 aluminum alloy T-joint by dual laser-beam bilateral synchronous welding. Opt. Laser Technol. 2022, 148, 107706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Jiang, H.; Cui, Z.; Liu, X.; Rong, L. Mechanism of the dependence of precipitation behavior on stress level during stress-aging in an Al-Zn-Mg alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1010, 177072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.Y.; Shen, Z.L.; Ren, C.X.; Li, Q.; Tao, N.R. Enhanced high-temperature strength of austenitic steels by nanotwins and nanoprecipitates. Scr. Mater. 2024, 242, 115938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J.B.; Riley, D.P. An experimental investigation of extrapolation methods in the derivation of accurate unit-cell dimensions of crystals. Proc. Phys. Soc. 1945, 57, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lie, R.; Li, S.; Chen, L.; Li, J.; Kong, L. Investigation of edge dislocation mobility in Ni-Co solid solutions by molecular dynamics simulation. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 38, 107779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.S.; Staiger, M.; Kral, M. Some new characteristics of the strengthening phase in β-phase magnesium-lithium alloys containing aluminum and beryllium. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2004, 371, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Jang, D.; Lee, M.; Choe, J.; Kim, K.; Lee, B.; Lee, K. Ti-induced microstructural evolution and mechanical enhancement in Al7075 alloy fabricated by laser powder bed fusion. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1010, 183458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, A. A dimensionally consistent size–strain plot method for crystallite size and microstrain estimation. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1048, 185324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H.; Jeon, D.M.; Yoon, S.Y.; Lee, J.P.; Kim, B.G.; Suh, S.J. The distribution of Cu and resultant resistivity change in sputter deposited Al-Cu film as a conductive layer. Thin Solid Film. 2003, 435, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Yang, Y.; Xie, H.; Zhan, L. Effect of ageing temperature on the mechanical properties and microstructures of cryogenic-rolled 2195 Al-Cu-Li alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2025, 924, 147855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.A.; Bammann, D.J. Validation of a model for static and dynamic recrystallization in metals. Int. J. Plast. 2012, 32–33, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, M. Strengthening 316L stainless steel fabricated by laser powder bed fusion via deep cryogenic treatment. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2025, 239, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Shan, H.; Han, X.; Han, X.; Lin, S.; Ma, Y.U.; Lou, M.; Wang, X.; Li, Y. Single-sided friction riveting process of aluminum sheet to profile structure without prefabricated hole. J. Mater. Process. Tech. 2022, 307, 117663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer, S.M.; Glavatskikh, M.V.; Barkov, R.Y.; Loginova, I.S.; Pozdniakov, A.V. Effect of Cr on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of the Al-Cu-Y-Zr Alloy. Metals 2023, 13, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kairy, S.K.; Rouxel, B.; Dumbre, J.; Lamb, J.; Langan, T.J.; Dorin, T.; Birbilis, N. Simultaneous improvement in corrosion resistance and hardness of a model 2xxx series Al-Cu alloy with the microstructural variation caused by Sc and Zr additions. Corros. Sci. 2019, 158, 108095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Geng, S.; Jiang, P.; Ren, L.; Han, C. Microstructure-based finite element analysis of mesoscale strain localization and macroscopic mechanical properties of aluminum alloy 2024 laser weld joint. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 849, 143482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Wang, J.; Williams, S.; Zhu, L.; Ding, J.; Diao, C.; Jiang, Z. Additive manufacturing of a functionally graded high entropy alloy using a hybrid powder-bed wire-based direct energy deposition approach. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 63, 103424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kai, X.; Wang, Y.; Chen, R.; Peng, Y.; Shi, A.; Tao, R.; Liang, X.; Li, G.; Chen, G.; Xu, X.; et al. Effects of in-situ ZrB2 nanoparticles and scandium on microstructure and mechanical property of 7N01 aluminum alloy. J. Rare Earths 2024, 42, 612–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Guo, Y.; Wang, J.; Xia, F.; Ma, K.; Duan, H.; Yang, Z.; Wang, P.; Liang, M.; Li, J. Novel AlCu solute cluster precipitates in the Al-Cu alloy by elevated aging and the effect on the tensile properties. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2023, 862, 144454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.; Zhang, J.; Sun, Q.; Fan, Z.; Li, G.; Yin, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, M. Inoculation treatment of an additively manufactured 2024 aluminum alloy with titanium nanoparticles. Acta Mater. 2020, 196, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boese, S.; Sevinsky, A.; Nourian-Avval, A.; Ozdemir, O.; Muftu, S. Laser assisted cold spray of aluminum alloy 6061: Experimental results. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 95, 104548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Alloy | Cu | Cr | Mn | Zr | Fe | Si | Al |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2CZ | 6.06 | 0.13 | - | 0.08 | 0.15 | 0.06 | Bal. |

| 4CZ * | 6.10 | 0.25 | - | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.06 | Bal. |

| 6CZ | 5.99 | 0.43 | - | 0.19 | 0.15 | 0.06 | Bal. |

| 2MZ | 6.07 | - | 0.13 | 0.07 | 0.14 | 0.06 | Bal. |

| 4MZ * | 6.02 | - | 0.25 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.06 | Bal. |

| 6MZ | 6.05 | - | 0.41 | 0.20 | 0.15 | 0.06 | Bal. |

| Alloy | As-Cast | T4 | T6 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2CZ | 3.45 (±0.74) | 1.46 (±0.33) | 1.47 (±0.45) |

| 4CZ | 3.56 (±0.56) | 0.82 (±0.27) | 0.94 (±0.30) |

| 6CZ | 4.08 (±0.64) | 0.91 (±0.22) | 2.25 (±0.15) |

| No. | Al | Cu | Fe | Phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1~11 | 39–82 | 7–52 | - | Al2Cu |

| 12~23 | 45–78 | 11–34 | 3–11 | Al7Cu2Fe |

| Alloy | As-Cast | T4 | T6 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2MZ | 4.69 (±0.92) | 1.23 (±0.11) | 1.45 (±0.14) |

| 4MZ | 4.28 (±0.48) | 0.44 (±0.10) | 1.01 (±0.26) |

| 6MZ | 4.62 (±0.44) | 1.26 (±0.23) | 1.59 (±0.32) |

| No. | Al | Cu | Fe | Mn | Phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1~12 | 40–87 | 5–51 | - | - | Al2Cu |

| 13~19 | 45–74 | 15–47 | 2–9 | - | Al7Cu2Fe |

| 20~31 | 46–63 | 21–34 | 4–9 | 1–4 | Al–Cu–Fe–Mn |

| Micro-Strain (σ) (×10−3) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Alloys | As-Cast | T4 | T6 |

| 2CZ | 3.73 | 1.18 | 3.27 |

| 4CZ | 2.48 | 2.28 | 4.68 |

| 6CZ | 4.19 | 2.27 | 3.78 |

| 2MZ | 4.36 | 2.64 | 3.82 |

| 4MZ | 3.88 | 1.69 | 3.88 |

| 6MZ | 4.10 | 1.97 | 4.22 |

| Dislocastion Density (×1012 m−2) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Alloys | As-Cast | T4 | T6 |

| 2CZ | 2.14 | 1.45 | 4.76 |

| 4CZ | 1.66 | 0.92 | 6.98 |

| 6CZ | 10.3 | 1.38 | 2.52 |

| 2MZ | 3.84 | 1.89 | 2.72 |

| 4MZ | 2.25 | 0.45 | 2.03 |

| 6MZ | 3.46 | 0.75 | 2.56 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lee, H.; Bang, J.; Yoon, P.; Lee, E. Effects of Combined Cr, Mn, and Zr Additions on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Al–6Cu Alloys Under Various Heat Treatment Conditions. Metals 2026, 16, 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16020143

Lee H, Bang J, Yoon P, Lee E. Effects of Combined Cr, Mn, and Zr Additions on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Al–6Cu Alloys Under Various Heat Treatment Conditions. Metals. 2026; 16(2):143. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16020143

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Hyuncheul, Jaehui Bang, Pilhwan Yoon, and Eunkyung Lee. 2026. "Effects of Combined Cr, Mn, and Zr Additions on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Al–6Cu Alloys Under Various Heat Treatment Conditions" Metals 16, no. 2: 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16020143

APA StyleLee, H., Bang, J., Yoon, P., & Lee, E. (2026). Effects of Combined Cr, Mn, and Zr Additions on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Al–6Cu Alloys Under Various Heat Treatment Conditions. Metals, 16(2), 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16020143