Enhancement of the Wear Properties of Tool Steels Through Gas Nitriding and S-Phase Coatings

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

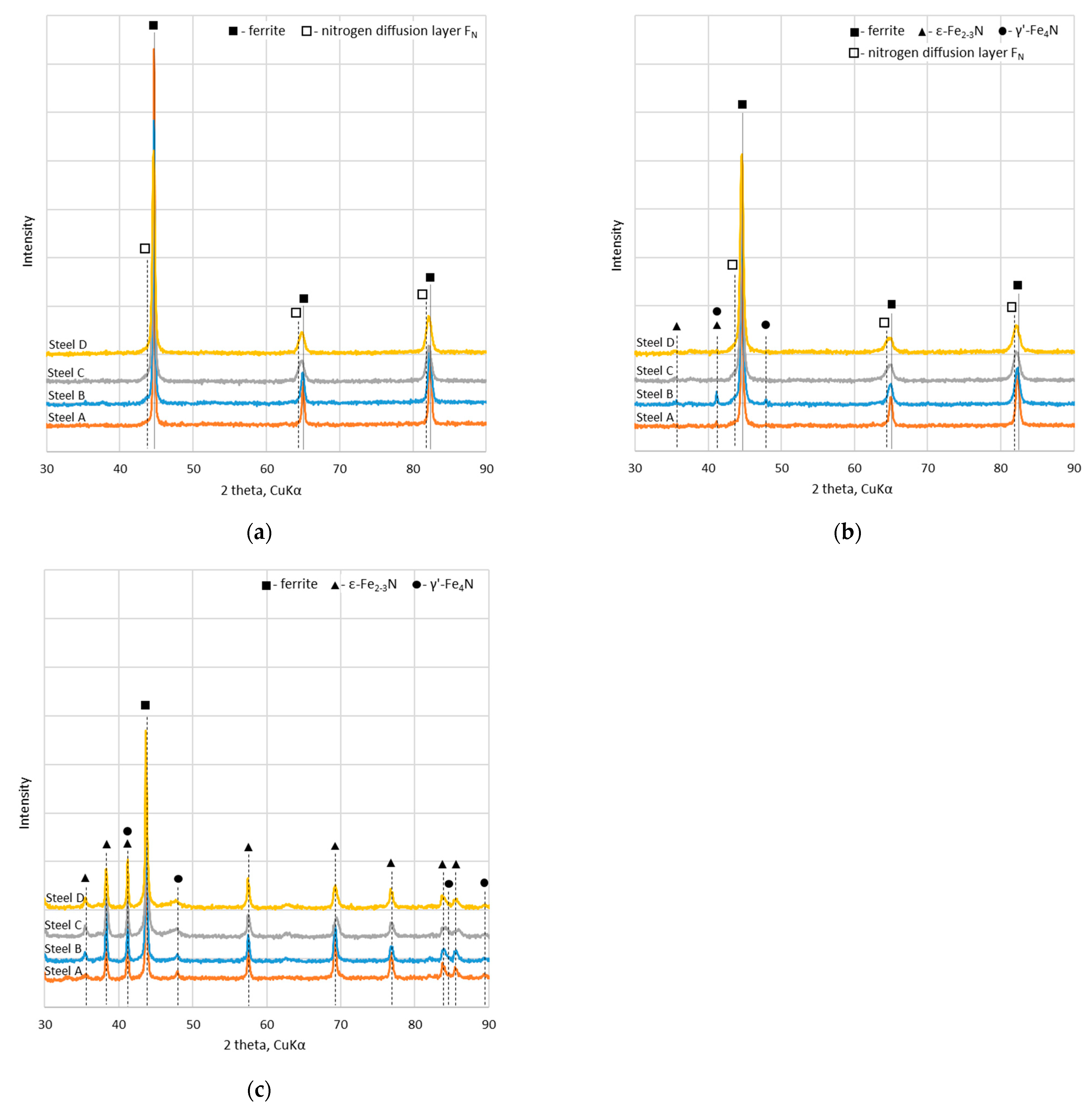

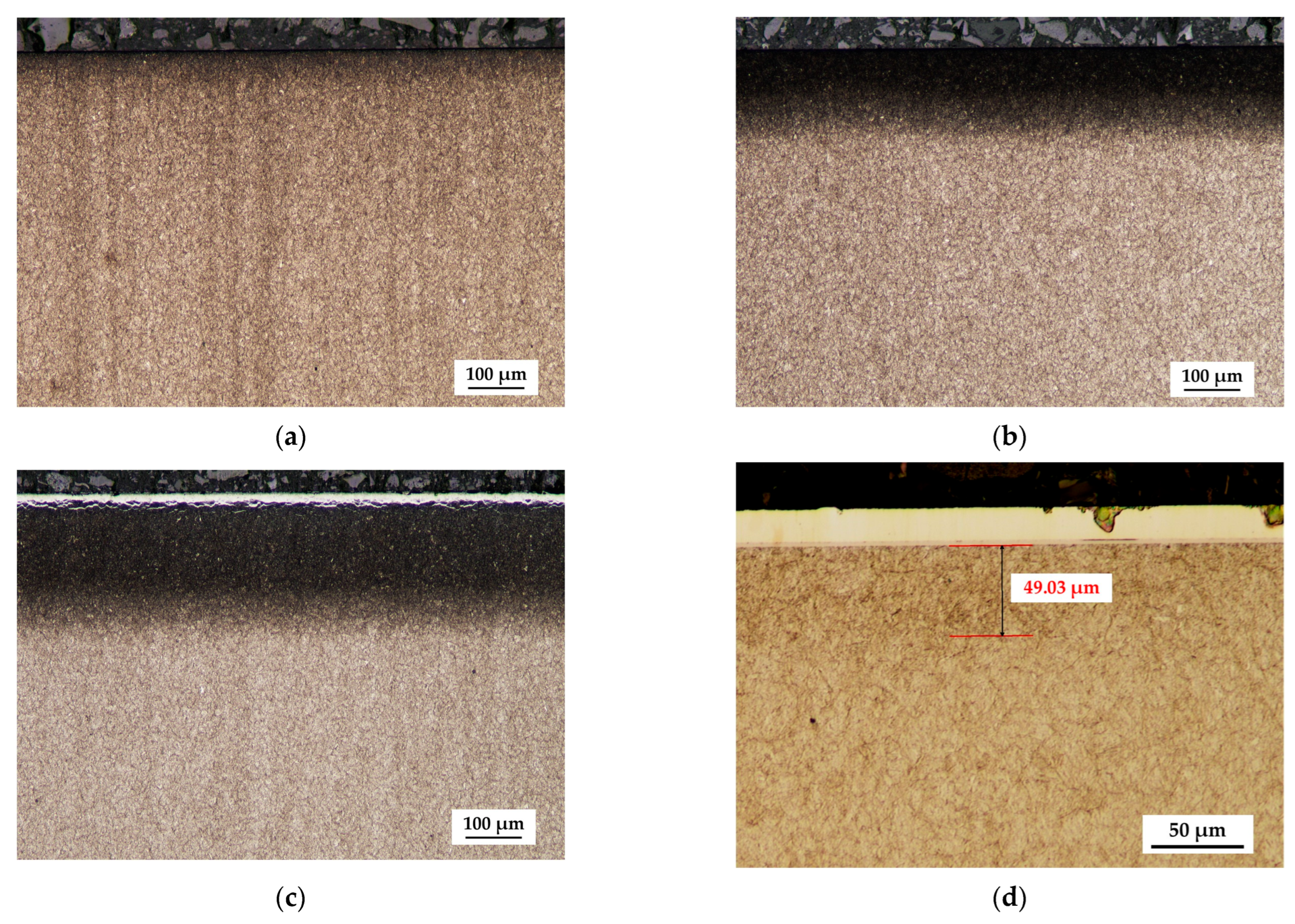

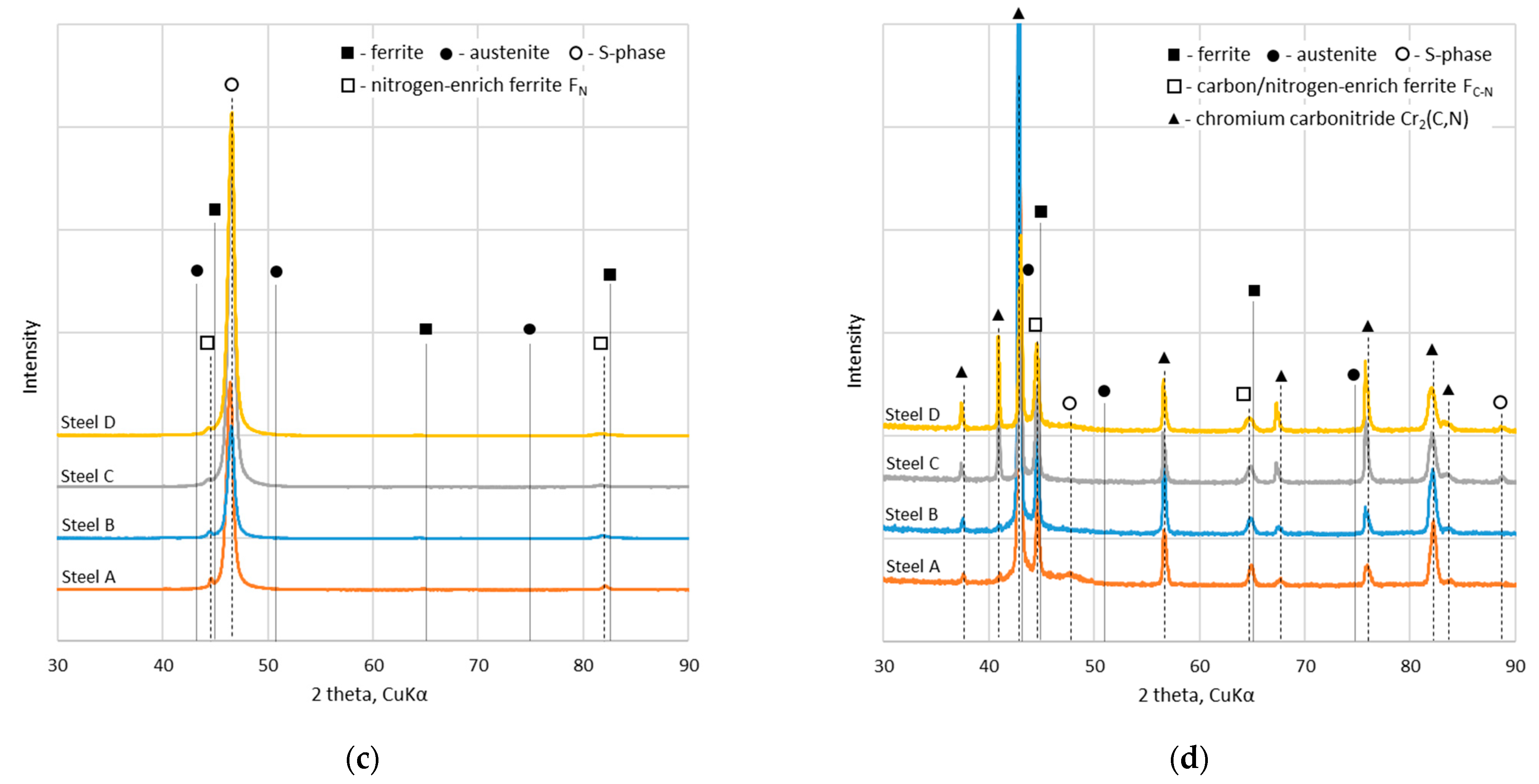

3.1. Phase Composition, Structure and Morphology

3.2. Hardness Measurements

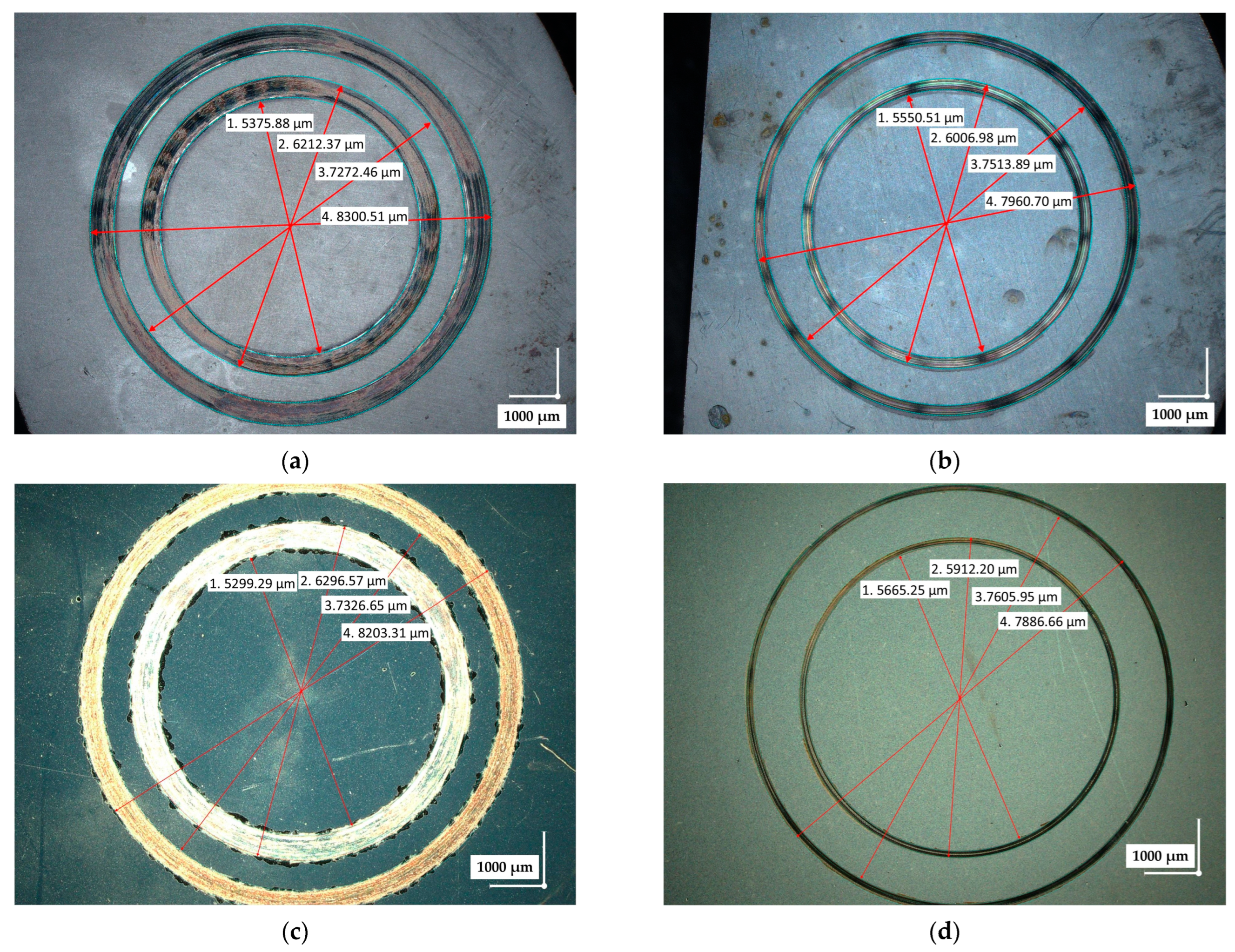

3.3. Tribological Measurements

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- The lowest wear rates of the nitrided layers, 1.2–5.0 × 10−5 mm3/N·m, were obtained for samples nitrided with a medium nitriding potential Kn = 0.79. This was attributed to the absence of a brittle nitride zone on the surface of the nitrided steel. These values were an order of magnitude lower than the wear rates of the hardened steels.

- S-phase coatings exhibited hardness comparable to nitrided layers at the highest nitriding potential Kn = 2.18 (740–1100 HV0.1), representing an 85–115% increase over the hardened steels, indicating that S-phase coatings may serve as an effective alternative when deposited in a high-nitrogen atmosphere.

- S-phase coatings exhibited wear rates one order of magnitude lower than those of nitrided steels, typically ranging from 1.0–3.0 × 10−6 mm3/N·m and, in some cases, reaching as low as 5.29 × 10−7 mm3/N·m.

- During the deposition of S-phase coatings at 400 °C, a nitrogen diffusion layer is simultaneously formed within the substrate, leading to a structure similar to that of duplex systems, i.e., a PVD coating on nitrided steel. The formation of the diffusion layer is facilitated by the increased nitrogen content in the deposition atmosphere during the S-phase coating process.

- The addition of carbon to the nitrogen-based S-phase does not have a beneficial effect on either the hardness or the wear rate of such coatings.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ebner, R.; Marsoner, S.; Siller, I.; Ecker, W. Thermal Fatigue Behaviour of Hot-Work Tool Steels: Heat Check Nucleation and Growth. Int. J. Microstruct. Mater. Prop. 2008, 3, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muro, M.; Artola, G.; Gorriño, A.; Angulo, C. Wear and Friction Evaluation of Different Tool Steels for Hot Stamping. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 2018, 3296398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwingenschlögl, P.; Niederhofer, P.; Merklein, M. Investigation on Basic Friction and Wear Mechanisms within Hot Stamping Considering the Influence of Tool Steel and Hardness. Wear 2019, 426–427, 378–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, M.; Klocke, F.; Lung, D. Tool Wear Simulation of Complex Shaped Coated Cutting Tools. Wear 2015, 330–331, 600–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawczyk, J.; Łukaszek-Sołek, A.; Śleboda, T.; Lisiecki, Ł.; Bembenek, M.; Cieślik, J.; Góral, T.; Pawlik, J. Tool Wear Issues in Hot Forging of Steel. Materials 2023, 16, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podgrajšek, M.; Glodež, S.; Ren, Z. Failure Analysis of Forging Die Insert Protected with Diffusion Layer and PVD Coating. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2015, 276, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panjan, P.; Urankar, I.; Navinšek, B.; Terčelj, M.; Turk, R.; Čekada, M.; Leskovšek, V. Improvement of Hot Forging Tools with Duplex Treatment. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2002, 151–152, 505–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktaş Çelik, G.; Atapek, Ş.H.; Polat, Ş.; Obrosov, A.; Weiß, S. Nitriding Effect on the Tribological Performance of CrN-, AlTiN-, and CrN/AlTiN-Coated DIN 1.2367 Hot Work Tool Steel. Materials 2023, 16, 2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lachowicz, M.M.; Ziemba, J.; Janik, M.; Trusz, A.; Hawryluk, M. Analysis of the Deterioration Mechanisms of Tools in the Process of Forging Elements for the Automotive Industry from Nickel–Chromium Steel in Order to Select a Wear-Limiting Coating. Materials 2025, 18, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gredić, T.; Zlatanović, M.; Popović, N.; Bogdanov, Ž. Properties of TiN Coatings Deposited onto Hot Work Steel Substrates Plasma Nitrided at Low Pressure. Surf. Coat. Technol. 1992, 54–55, 502–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitay, E.; Tóth, L.; Kovács, T.A.; Nyikes, Z.; Gergely, A.L. Experimental Study on the Influence of TiN/AlTiN PVD Layer on the Surface Characteristics of Hot Work Tool Steel. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillmann, W.; Grisales, D.; Stangier, D.; Butzke, T. Tribomechanical Behaviour of TiAlN and CrAlN Coatings Deposited onto AISI H11 with Different Pre-Treatments. Coatings 2019, 9, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panjan, P.; Cvahte, P.; Čekada, M.; Navinšek, B.; Urankar, I. PVD CrN Coating for Protection of Extrusion Dies. Vacuum 2001, 61, 241–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, G.; Fernández-Vicente, A.; Cid, J. Influence of the Nitriding Time in the Wear Behaviour of an AISI H13 Steel during a Crankshaft Forging Process. Wear 2007, 263, 1375–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roliński, E.; Sharp, G. When and Why Ion Nitriding/Nitrocarburizing Makes Good Sense. Industrial Heating. August 2005, pp. 67–74. Available online: https://www.ahtcorp.com/webres/File/Advanced%20HT%20Reprint%20v3.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- Roliński, E.; Damirgi, T.; Sharp, G. Plasma, Gas Nitriding and Nitrocarburizing for Engineering Components and Metal-Forming Tools. Industrial Heating. May 2012, pp. 53–56. Available online: https://www.ahtcorp.com/webres/File/Plasma,Gas%20Nitriding%20&%20Nitrocarburizing%20for%20Engineering%20Components%20and%20Metal-Forming%20Tools.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- Kim, K.H.; Lee, W.B.; Kim, T.H.; Son, S.W. Microstructure and Fracture Toughness of Nitrided D2 Steels Using Potential-Controlled Nitriding. Metals 2022, 12, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ARI, A. Effect of Gas Nitriding Parameters on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of DIN 1.2367 Hot Work Tool Steel. Int. J. Adv. Nat. Sci. Eng. Res. 2023, 7, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundalkar, D.; Mavalankar, M.; Tewari, A. Effect of Gas Nitriding on the Thermal Fatigue Behavior of Martensitic Chromium Hot-Work Tool Steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2016, 651, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Zhao, L.; Chen, Z.; Hu, X.; Yan, Z. Investigation of the Surface Properties and Wear Properties of AISI H11 Steel Treated by Auxiliary Heating Plasma Nitriding. Coatings 2020, 10, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhagiar, J.; Jung, A.; Gouriou, D.; Mallia, B.; Dong, H. S-Phase against S-Phase Tribopairs for Biomedical Applications. Wear 2013, 301, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dearnley, P.A.; Matthews, A.; Leyland, A. Tribological Behaviour of Thermochemically Surface Engineered Steels. In Thermochemical Surface Engineering of Steels: Improving Materials Performance; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 241–266. ISBN 9780857095923. [Google Scholar]

- Kochmański, P.; Baranowska, J. Structure and Properties of Gas Nitrided Layers on Nanoflex Stainless Steel. Defect Diffus. Forum 2012, 326–328, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapuściński, J.; Macyszyn, Ł.; Zielinski, M.; Meller, A.; Lehmann, M.; Bartkowiak, T. Effect of Surface Finishing and Nitriding on the Wetting Properties of Hot Forging Tools. Materials 2025, 18, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trzepieciński, T.; Szwajka, K.; Szewczyk, M.; Zielińska-Szwajka, J.; Barlak, M.; Nowakowska-Langier, K.; Okrasa, S.; Trzepieciński, T.; Szwajka, K.; Szewczyk, M.; et al. Analysis of Influence of Coating Type on Friction Behaviour and Surface Topography of DC04/1.0338 Steel Sheet in Bending Under Tension Friction Test. Materials 2024, 17, 5650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berladir, K.; Hovorun, T.; Botko, F.; Radchenko, S.; Oleshko, O.; Berladir, K.; Hovorun, T.; Botko, F.; Radchenko, S.; Oleshko, O. Thin Modified Nitrided Layers of High-Speed Steels. Materials 2025, 18, 2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H. S-Phase Surface Engineering of Fe-Cr, Co-Cr and Ni-Cr Alloys. Int. Mater. Rev. 2010, 55, 65–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saker, A.; Leroy, C.; Michel, H.; Frantz, C. Properties of Sputtered Stainless Steel-Nitrogen Coatings and Structural Analogy with Low Temperature Plasma Nitrided Layers of Austenitic Steels. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 1991, 140, 702–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fewell, M.P.; Mitchell, D.R.G.; Priest, J.M.; Short, K.T.; Collins, G.A. The Nature of Expanded Austenite. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2000, 131, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, T. Current Status of Supersaturated Surface Engineered S-Phase Materials. Key Eng. Mater. 2008, 373–374, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, T.; Somers, M.A.J. Low Temperature Gaseous Nitriding and Carburising of Stainless Steel. Surf. Eng. 2005, 21, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larisch, B.; Brusky, U.; Spies, H.J. Plasma Nitriding of Stainless Steels at Low Temperatures. Surf. Coat. Technol. 1999, 116–119, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochmański, P.; Bielawski, J.; Baranowska, J. Effect of Low Temperature Gas Nitriding on Corrosion Properties of Duplex Stainless Steel. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2025, 517, 132842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgioli, F. The “Expanded” Phases in the Low-Temperature Treated Stainless Steels: A Review. Metals 2022, 12, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.Y.; Thaiwatthana, S.; Dong, H.; Bell, T. Thermal Stability of Carbon S Phase in 316 Stainless Steel. Surf. Eng. 2002, 18, 448–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosokawa, A.; Shimamura, K.; Ueda, T. Cutting Characteristics of PVD-Coated Tools Deposited by Unbalanced Magnetron Sputtering Method. CIRP Ann. Manuf. Technol. 2012, 61, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalin, M.; Jerina, J. The Effect of Temperature and Sliding Distance on Coated (CrN, TiAlN) and Uncoated Nitrided Hot-Work Tool Steels against an Aluminium Alloy. Wear 2015, 330–331, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navinšek, B.; Panjan, P. Novel Applications of CrN (PVD) Coatings Deposited at 200 °C. Surf. Coat. Technol. 1995, 74–75, 919–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navinšek, B.; Panjan, P.; Milošev, I. Industrial Applications of CrN (PVD) Coatings, Deposited at High and Low Temperatures. Surf. Coat. Technol. 1997, 97, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korhonen, A.S.; Harju, E. Surface Engineering with Light Alloys—Hard Coatings, Thin Films, and Plasma Nitriding. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2000, 9, 302–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Deng, J.; Cui, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, J. Friction and Wear Properties of TiN, TiAlN, AlTiN and CrAlN PVD Nitride Coatings. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2012, 31, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warcholinski, B.; Gilewicz, A.; Kuklinski, Z.; Myslinski, P. Hard CrCN/CrN Multilayer Coatings for Tribological Applications. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2010, 204, 2289–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrogalli, C.; Montesano, L.; Gelfi, M.; La Vecchia, G.M.; Solazzi, L. Tribological and Corrosion Behavior of CrN Coatings: Roles of Substrate and Deposition Defects. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2014, 258, 878–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.H.; Chen, H.W.; Lin, C.Y.; Hu, S.H. Effect of N2/Ar Ratio on Wear Behavior of Multi-Element Nitride Coatings on AISI H13 Tool Steel. Materials 2024, 17, 4748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xiao, Y.; Gong, L.; Luo, X.; Lin, Y.; He, L.; Zhong, X.; Song, H.; Wang, J. Multiscale Multilayer (AlCrSiN/CrN)n/Cr/(AlCrSiN/CrN)n Coatings with Both Infrared Stealth and Tribological Properties. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 1008, 176787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkan, D.; Yilmaz, M.A.; Karakurt, D.; Szala, M.; Walczak, M.; Bakdemir, S.A.; Türküz, C.; Sulukan, E. Effect of AISI H13 Steel Substrate Nitriding on AlCrN, ZrN, TiSiN, and TiCrN Multilayer PVD Coatings Wear and Friction Behaviors at a Different Temperature Level. Materials 2023, 16, 1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryska, S.; Baranowska, J. Corrosion Properties of S-Phase/Cr2N Composite Coatings Deposited on Austenitic Stainless Steel. Materials 2021, 15, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilewicz, A.; Murzynski, D.; Dobruchowska, E.; Kwiatkowski, J.; Olik, R.; Ratajski, J.; Warcholinski, B. Wear and Corrosion Behavior of CrCN/CrN Coatings Deposited by Cathodic Arc Evaporation on Nitrided 42CrMo4 Steel Substrates. Prot. Met. Phys. Chem. Surf. 2017, 53, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappaganthu, S.R.; Sun, Y. Influence of Sputter Deposition Conditions on Phase Evolution in Nitrogen-Doped Stainless Steel Films. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2005, 198, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebholz, C.; Ziegele, H.; Leyland, A.; Matthews, A. Structure, Mechanical and Tribological Properties of Nitrogen-Containing Chromium Coatings Prepared by Reactive Magnetron Sputtering. Surf. Coat. Technol. 1999, 115, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, D.M.; Anders, A. Review of Cathodic Arc Deposition Technology at the Start of the New Millennium. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2000, 133–134, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Asadi, M.M.; Al-Tameemi, H.A. A Review of Tribological Properties and Deposition Methods for Selected Hard Protective Coatings. Tribol. Int. 2022, 176, 107919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryska, S.; Giza, P.; Jedrzejewski, R.; Baranowska, J. Carbon Doped Austenitic Stainless Steel Coatings Obtained by Reactive Magnetron Sputtering. Acta Phys. Pol. A 2015, 128, 879–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultman, L. Thermal Stability of Nitride Thin Films. Vacuum 2000, 57, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahm, K.L.; Dearnley, P.A. S phase coatings produced by unbalanced magnetron sputtering. Surf. Eng. 1996, 12, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryska, S.; Baranowska, J. The Pressure Influence on the Properties of S-Phase Coatings Deposited by Reactive Magnetron Sputtering. Acta Phys. Pol. A 2013, 123, 854–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Kappaganthu, S.R. Effect of Nitrogen Doping on Sliding Wear Behaviour of Stainless Steel Coatings. Tribol. Lett. 2004, 17, 845–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskar, S.V.; Kudal, H.N. Tribology of Nitrided-Coated Steel-a Review. Arch. Mech. Technol. Mater. 2017, 37, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abisset, S.; Maury, F.; Feurer, R.; Ducarroir, M.; Nadal, M.; Andrieux, M. Gas and Plasma Nitriding Pretreatments of Steel Substrates before CVD Growth of Hard Refractory Coatings. Thin Solid Film. 1998, 315, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Li, X. Design and Characterisation of a New Duplex Surface System Based on S-Phase Hardening and Carbon-Based Coating for ASTM F1537 Co-Cr-Mo Alloy. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 292, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokrzycka, M.; Przybyło, A.; Góral, M.; Kościelniak, B.; Drajewicz, M.; Kubaszek, T.; Gancarczyk, K.; Gradzik, A.; Dychtoń, K.; Poręba, M.; et al. The Influence of Plasma Nitriding Process Conditions on the Microstructure of Coatings Obtained on the Substrate of Selected Tool Steels. Adv. Mech. Mater. Eng. 2024, 41, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, M.; Staia, M.H.; Puchi-Cabrera, E.S. Evaluation of Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Nitrided Steels. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2008, 202, 1935–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoy, R.; Kamminga, J.D.; Janssen, G.C.A.M. Scratch Resistance of CrN Coatings on Nitrided Steel. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2006, 200, 3856–3860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gredić, T.; Zlatanović, M.; Popović, N.; Bogdanov, Ž. Effect of Plasma Nitriding on the Properties of (Ti, Al)N Coatings Deposited onto Hot Work Steel Substrates. Thin Solid Film. 1993, 228, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Tian, X.; Gong, C.; Liu, X.; Li, J.; Zhu, J.; Lin, H. Effect of Plasma Nitriding Ion Current Density on Tribological Properties of Composite CrAlN Coatings. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 3954–3962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navinšek, B.; Panjan, P.; Gorenjak, F. Improvement of Hot Forging Manufacturing with PVD and DUPLEX Coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2001, 137, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallin, E.; Helmersson, U. Method for Producing PVD Coatings. United States Patent and Trademark Office US8540786B2, 24 September 2013. Sandvik Intellectual Property AB. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/US8540786B2/en (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- Fontaine, F.; Kalss, W.; Lechthaler, M. Workpiece with Hard Coating. Australian Patent AU2007302162B2, 28 June 2012. Oerlikon Trading AG, Trübbach. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/AU2007302162B2/en (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- Müller, A.; Sobiech, M.L.; Maringer, C. Hot Metal Sheet Forming or Stamping Tools with Cr–Si–N Coatings. United States Patent Application Publication US20140144200A1, 29 May 2014. Oerlikon Surface Solutions AG Pfaeffikon (Original Assignee: Oerlikon Trading AG, Trübbach). Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/US20140144200A1/en (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- Schier, V. Coating for a Cutting Tool and Corresponding Production Method. United States Patent US7758975B2, 20 July 2010. Walter AG. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/US7758975B2/en (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- ISO 6507-1:2023; Metallic Materials—Vickers Hardness Test—Part 1: Test Method. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/83898.html (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- Miyamoto, J.; Abraha, P. The Effect of Plasma Nitriding Treatment Time on the Tribological Properties of the AISI H13 Tool Steel. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2019, 375, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Liu, B.; Zhang, X.; Gu, J. Enhancing Heavy Load Wear Resistance of AISI 4140 Steel through the Formation of a Severely Deformed Compound-Free Nitrided Surface Layer. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2018, 356, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronostajski, Z.; Widomski, P.; Kaszuba, M.; Zwierzchowski, M.; Polak, S.; Piechowicz, Ł.; Kowalska, J.; Długozima, M. Influence of the Phase Structure of Nitrides and Properties of Nitrided Layers on the Durability of Tools Applied in Hot Forging Processes. J. Manuf. Process 2020, 52, 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranowska, J.; Fryska, S.; Suszko, T. The Influence of Temperature and Nitrogen Pressure on S-Phase Coatings Deposition by Reactive Magnetron Sputtering. Vacuum 2013, 90, 160–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryska, S.; Baranowska, J. Microstructure of Reactive Magnetron Sputtered S-Phase Coatings with a Diffusion Sub-Layer. Vacuum 2017, 142, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryska, S.; Słowik, J.; Baranowska, J. Structure and Mechanical Properties of Chromium Nitride/S-Phase Composite Coatings Deposited on 304 Stainless Steel. Thin Solid Film. 2019, 676, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häglund, J.; Fernández Guillermet, A.; Grimvall, G.; Körling, M. Theory of Bonding in Transition-Metal Carbides and Nitrides. Phys. Rev. B 1993, 48, 11685–11691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P.; DelaCruz, S.; Tsai, D.S.; Wang, Z.; Carraro, C.; Maboudian, R. Enhanced Thermal Stability by Introducing TiN Diffusion Barrier Layer between W and SiC. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2019, 102, 5613–5619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Liu, D.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, T.Y.; Huang, L.F. Nitride Coatings for Environmental Barriers: The Key Microscopic Mechanisms and Momentous Applications of First-Principles Calculations. Surf. Sci. Technol. 2024, 2, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Nam, K.T.; Datta, A.; Kim, K.B. Failure Mechanism of a Multilayer (TiN/Al/TiN) Diffusion Barrier between Copper and Silicon. J. Appl. Phys. 2002, 92, 5512–5519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhao, X.; Li, W.; Qin, M.; Gu, J. Effect of Nitrided-Layer Microstructure Control on Wear Behavior of AISI H13 Hot Work Die Steel. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 431, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakhnina, V.D.; Turkovskaya, E.P. Effect of Carbon on the Structure of the Nitrided Case on Steels of the Kh13 Type. Met. Sci. Heat Treat. 1971, 13, 114–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somers, M.A.J. Nitriding and Nitrocarburizing; Current Status and Future Challenges. In Proceedings of the Heat Treat & Surface Engineering Conference & Expo 2013—Chennai Trade Center, Chennai, India, 16–18 May 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Diffraction Analysis of the Microstructure of Materials; Mittemeijer, E.J., Scardi, P., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; Volume 68, ISBN 978-3-642-07352-6. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, F.; Jia, Y. Research on Gas Nitriding Process and Performance of 25Cr2MoV Steel. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Mechanical Engineering, Materials, and Automation Technology (MMEAT 2024), Wuhan, China, 27 September 2024; 13261, pp. 422–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Qu, S.; Jia, S.; Li, X. Evolution of the Fretting Wear Damage of a Complex Phase Compound Layer for a Nitrided High-Carbon High-Chromium Steel. Metals 2020, 10, 1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, S.; Liang, Y.; Tian, X.; Gu, J. Effect of Carburizing and Nitriding Duplex Treatment on the Friction and Wear Properties of 20CrNi2Mo Steel. Mater. Res. Express 2023, 10, 036507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.-Z.; Zeng, X.T.; Liu, Y.C.; Wei, J.; Holiday, P. Influence of Substrate Hardness on the Properties of PVD Hard Coatings. Synth. React. Inorg. Met.-Org. Nano-Met. Chem. 2008, 38, 156–161. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/15533170801926028 (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- Bull, S.J.; Bhat, D.G.; Staia, M.H. Properties and Performance of Commercial TiCN Coatings. Part 2: Tribological Performance. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2003, 163–164, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Steel Designation | Steel Grade | Chemical Composition [wt%] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | Si | Mn | Cr | Mo | V | Ni | ||

| A | 40CrMnNiMo8-6-4 | 0.38 | 0.30 | 1.50 | 2.00 | 0.20 | - | 1.10 |

| B | 60CrMoV18-5 | 0.60 | 0.35 | 0.80 | 4.50 | 0.50 | 0.20 | - |

| C | X50CrMoV5-2 | 0.50 | 0.20 | 0.50 | 5.00 | 2.30 | 0.50 | - |

| D | X38CrMoV5-3 | 0.38 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 5.00 | 3.00 | 0.50 | - |

| Steel | Quenching | Tempering | Hardness | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature [°C] | Time [h] | Atmosphere | Cooling | Vacuum | HV0.1 | |

| A | 860 | 1 | Endothermic gas | Oil | 1× 600 °C, 2 h | 396 ± 2 |

| B | 1060 | 1 | Vacuum | Nitrogen | 2× 600 °C, 2 h | 443 ± 3 |

| C | 1060 | 1 | Vacuum | Nitrogen | 2× 600 °C, 2 h | 520 ± 5 |

| D | 1060 | 1 | Vacuum | Nitrogen | 2× 600 °C, 2 h | 596 ± 3 |

| Process 1 | Process 2 | Process 3 | Process 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atmosphere [%vol.] | 80% Ar +20% N2 | 80% Ar +20% N2 | 60% Ar +40% N2 | 60% Ar +20% N2 +20% CH4 |

| Substrate temperature | 200 °C | 400 °C | 400 °C | 400 °C |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fryska, S.; Wypych, M.; Kochmański, P.; Baranowska, J. Enhancement of the Wear Properties of Tool Steels Through Gas Nitriding and S-Phase Coatings. Metals 2026, 16, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010009

Fryska S, Wypych M, Kochmański P, Baranowska J. Enhancement of the Wear Properties of Tool Steels Through Gas Nitriding and S-Phase Coatings. Metals. 2026; 16(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleFryska, Sebastian, Mateusz Wypych, Paweł Kochmański, and Jolanta Baranowska. 2026. "Enhancement of the Wear Properties of Tool Steels Through Gas Nitriding and S-Phase Coatings" Metals 16, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010009

APA StyleFryska, S., Wypych, M., Kochmański, P., & Baranowska, J. (2026). Enhancement of the Wear Properties of Tool Steels Through Gas Nitriding and S-Phase Coatings. Metals, 16(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010009