Experimental Study on the Removal of Copper Cyanide from Simulated Cyanide Leaching Gold Wastewater by Flocculation Flotation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Apparatus and Reagents

2.2. Simulation Copper Cyanide Wastewater Flotation Experiment

2.3. Characterization of Flocculation-Floating Mechanisms

2.3.1. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR) Testing

2.3.2. Zeta Potential Measurement

2.3.3. X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS)

2.3.4. Scanning Electron Microscopy Analysis

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Flotation Test Results

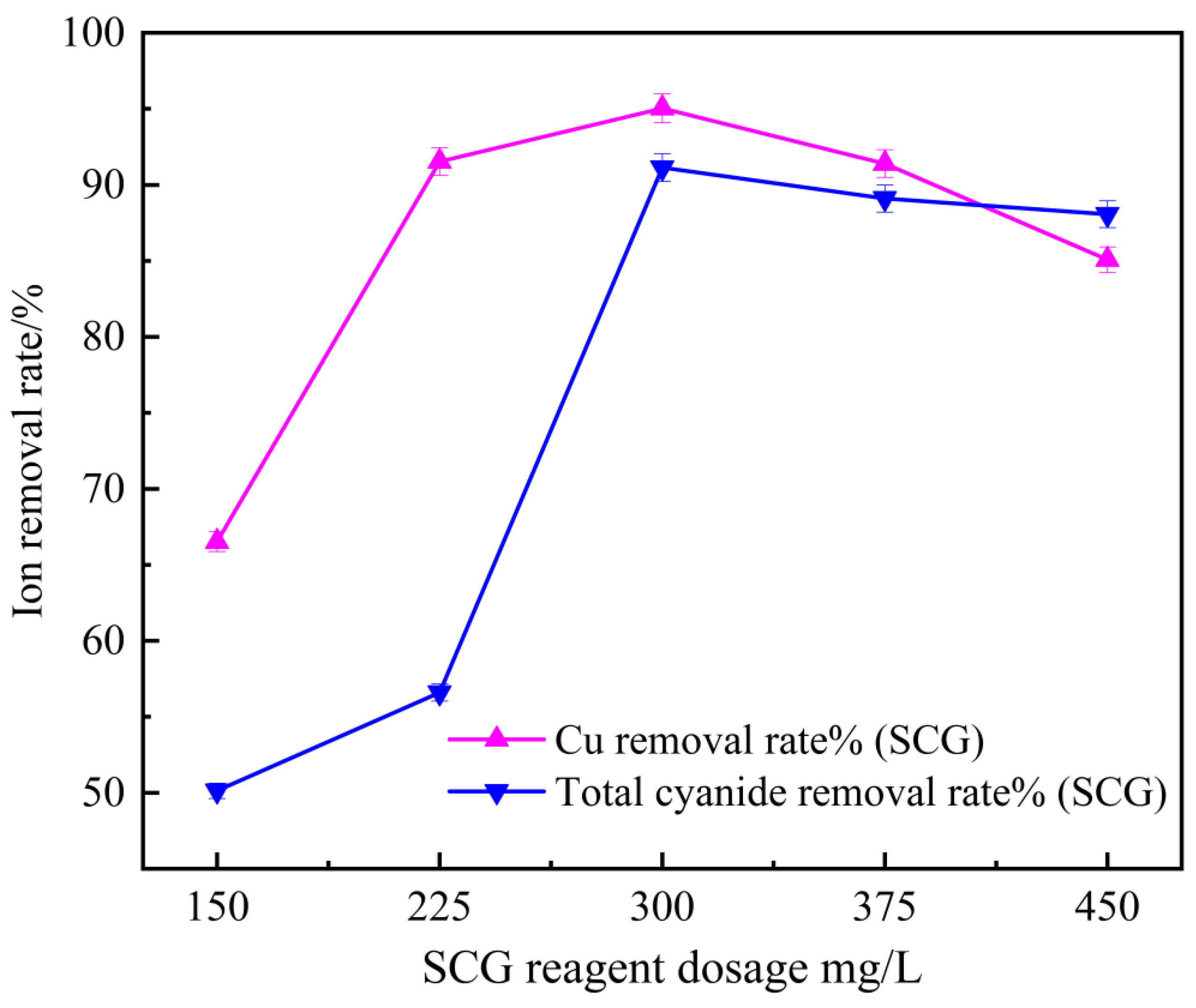

3.1.1. Reagent Dosage Tests

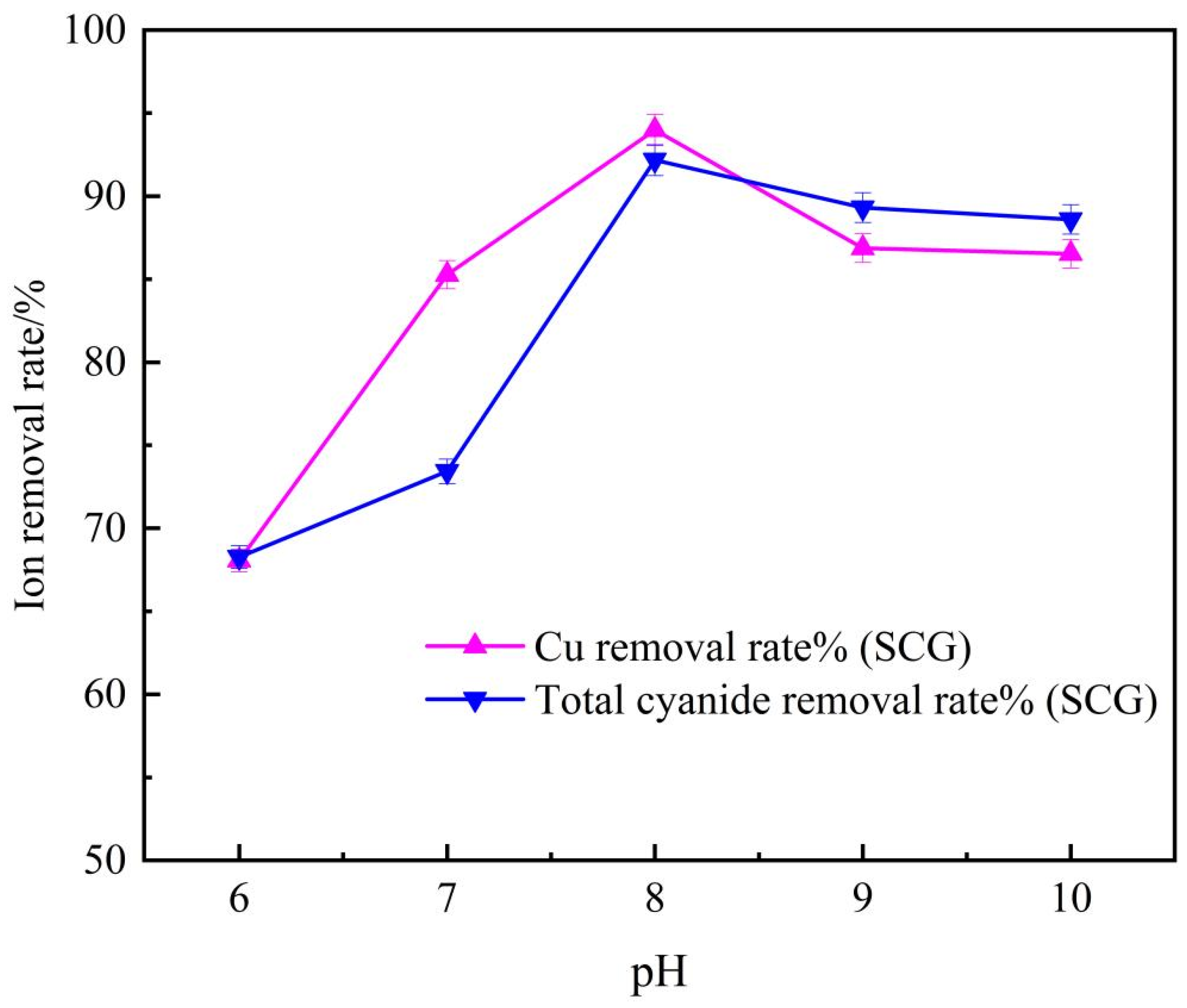

3.1.2. Flotation pH Tests

3.1.3. Flotation Time Tests

3.2. Chemical Calculation of Copper–Cyanide Complex Ion Solution

3.3. Zeta Potential Tests

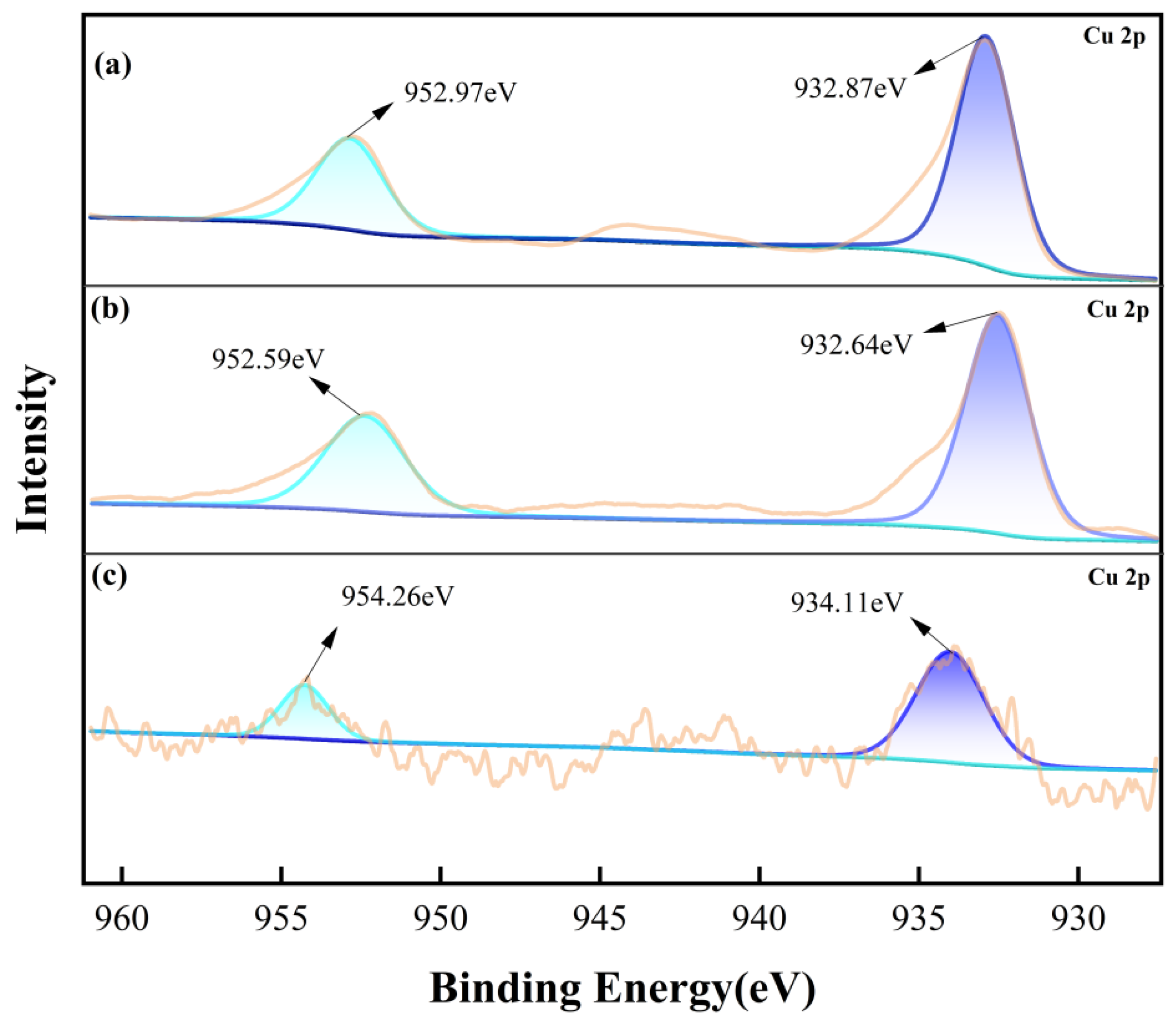

3.4. X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) Tests

3.5. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR) Tests

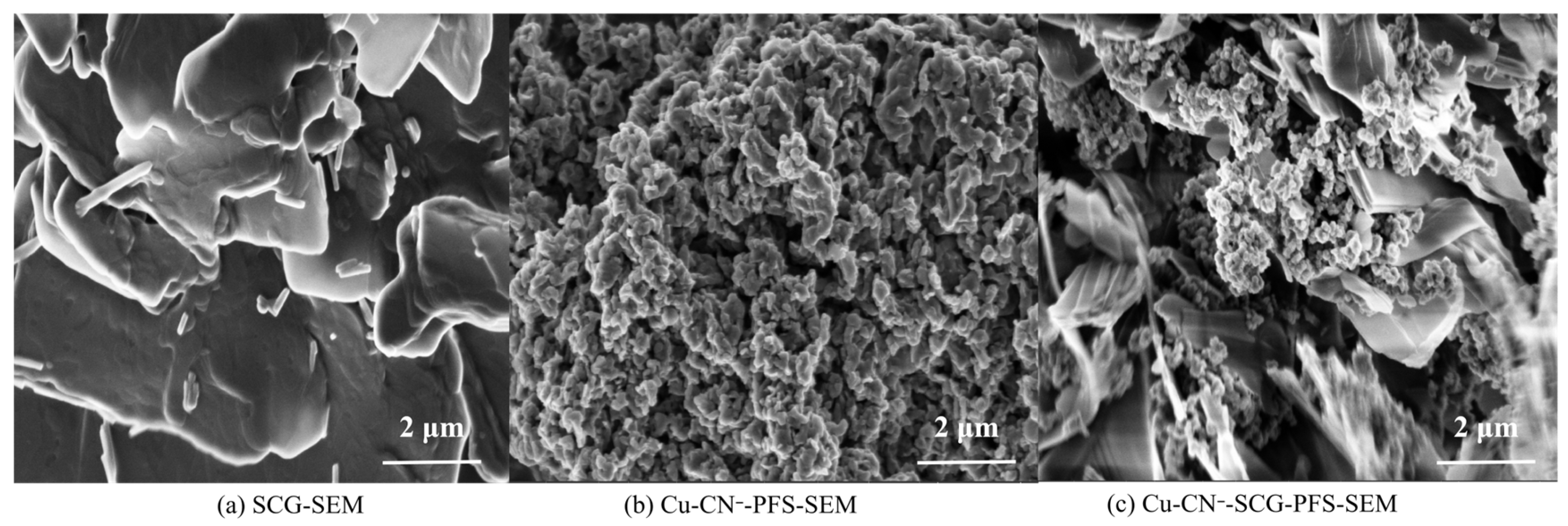

3.6. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Che, X. Research Progress on the Three Major Mechanisms and Strengthening Processes of Cyanide Leaching of Gold. China Resour. Compr. Util. 2024, 42, 174–180. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, T. The chemistry of gold extraction. Int. Mater. Rev. 2013, 37, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.T.; Cai, M.M.; Qin, X.W.; Xu, C.; Gao, Y.T.; Xu, Q. Experimental study on leaching factors of copper from copper bearing gold minerals. World Nonferrous Met. 2023, 13, 139–141. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, B.S.; Gao, H.J.; Zhang, Z.X. Treatment of cyanide-containing wastewater from a gold mine by alkaline chlorination process. China Nonferrous Metall. 2020, 49, 69–72. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso-González, O.; Nava-Alonso, F.; Uribe-Salas, A. Copper removal from cyanide solutions by acidification. Miner. Eng. A 2009, 22, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitis, M.; Karakaya, E.; Yigit, N.O.; Civelekoglu, G.; Akcil, A. Heterogeneous catalytic degradation of cyanide using copper-impregnated pumice and hydrogen peroxide. Water Res. 2005, 39, 1652–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, H.M. Treatment of cyanide-containing wastewater by acidification method. Xinjiang Nonferrous Met. 2010, 2, 108–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.J.; Shen, F.Z. High concentration cyanide-containing wastewater treatment by ferrous sulfate and chlorine dioxide. Gold 2009, 30, 46–49. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.F.; Meng, Q.J.; Meng, L. A Two-Stage Process for Treating Hospital Wastewater Containing High Content of Cyanide. Shanghai Environ. Sci. 2005, 3, 104–106+121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, C.; Martínez, S. Indirect electrochemical oxidation of cyanide by hydrogen peroxide generated at a carbon cathode. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2006, 32, 3163–3169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedyukevich, A.V.; Kubyshkin, A.S.; Blokhin, A.A.; Sukharzhevskii, S.M.; Vorob’ev-Desyatovskii, N.V. Use of ion-exchange resins to deal with the effect of preg-robbing of gold in the course of cyanide leaching. Russ. J. Appl. Chem. 2015, 88, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Breuer, P.L.; Jeffrey, M.I. Comparison of activated carbon and ion-exchange resins in recovering copper from cyanide leach solutions. Hydrometallurgy 2010, 101, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Huang, L.; Yan, J.; Liu, Y.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, Q.; Li, M.; Xing, X.; Li, L.; et al. Machine learning simulating and predicting the adsorption performance of activated carbons for removing methylene blue from wastewater. MetaResource 2025, 2, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, N.W.; Sebba, F. Concentration of the fluorozirconate ion by ion flotation. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 1965, 15, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoseinian, F.S.; Irannajad, M.; Nooshabadi, A.J. Ion flotation for removal of Ni(II) and Zn(II) ions from wastewaters. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2015, 143, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouboulis, A.I. Silver recovery from aqueous streams using ion flotation. Miner. Eng. 1995, 8, 1477–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobacheva, O.L.; Berlinskii, I.V.; Cheremisina, O.V. Solvent sublation and ion flotation in aqueous salt solutions containing Ce(III) and Y(III) in the presence of a surfactant. Russ. J. Appl. Chem. 2014, 87, 1863–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Xu, P.Y.; Wang, Y.L.; Su, D.S.; Yuan, Z.G.; Jiang, B.Z.; Yu, J.W. Effect of different grinding methods on floatability of quartz in dodecylamine system. Min. Metall. 2023, 32, 58–64. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, W.Z.; Zhang, X.S.; Ma, Y.Q.; Wu, C.H.; Zhang, R. Study on the effect of sodium cocoyl glycinate on flotation separation of siderite and hematite. Met. Mine 2025, 7, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, K.; Yi, X.Y.; Ma, J.W.; Cao, Y.; Li, G.; Liu, S.; Wang, T.; An, N. Ion flotation of heavy metal ions by using biodegradable biosurfactant as collector: Application and removal mechanism. Miner. Eng. 2022, 176, 107338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W. Experimental Study on Treatment of Copper-Cyanide-Containing Wastewater from Gold Mines by Co-Flocculation Method; China University of Mining and Technology: Suzhou, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zawawi, D.; Halizah, A.; Latif, A.; Nasir, N.; Ridzuan, M.B.; Ahmad, Z. Suspended Solid, Color, COD and Oil and Grease Removal from Biodiesel Wastewater by Coagulation and Flocculation Processes. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 195, 2407–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elisabeth, T.; Belleville, P.; Jolivet, J.P.; Livage, J. Transformation of ferric hydroxide into spinel by iron(II) adsorption. Langmuir 1992, 8, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liu, W.; Liu, W.; Zhou, S.; Gao, S.; Shen, Y. Capture of copper cyanide complex ions based on self-assembly of ionic liquids actuation and application to cyanide wastewater. Hydrometallurgy 2023, 218, 106043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, R. Synthesis and Characterization of Amino Acid Surfactants; Changchun University of Technology: Changchun, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Yea, D.N.; Lee, S.M.; Jo, S.H.; Yu, H.P.; Lim, J.C.; Zhang, Y.M. Preparation of Environmentally Friendly Amino Acid Surfactants and Evaluation of Washing Related Interfacial Properties. China Clean. Ind. 2019, 5, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, C.; Feng, D.; Dong, M.; Zhang, H.; Wen, X.; Liu, Y.; Cai, W. Experimental Study on the Removal of Copper Cyanide from Simulated Cyanide Leaching Gold Wastewater by Flocculation Flotation. Metals 2026, 16, 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010075

Zhang C, Feng D, Dong M, Zhang H, Wen X, Liu Y, Cai W. Experimental Study on the Removal of Copper Cyanide from Simulated Cyanide Leaching Gold Wastewater by Flocculation Flotation. Metals. 2026; 16(1):75. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010075

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Chenhao, Dongxia Feng, Meng Dong, Heng Zhang, Xujie Wen, Yuanbin Liu, and Wang Cai. 2026. "Experimental Study on the Removal of Copper Cyanide from Simulated Cyanide Leaching Gold Wastewater by Flocculation Flotation" Metals 16, no. 1: 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010075

APA StyleZhang, C., Feng, D., Dong, M., Zhang, H., Wen, X., Liu, Y., & Cai, W. (2026). Experimental Study on the Removal of Copper Cyanide from Simulated Cyanide Leaching Gold Wastewater by Flocculation Flotation. Metals, 16(1), 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010075