A New Methodology for Determining the Friction Factor

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

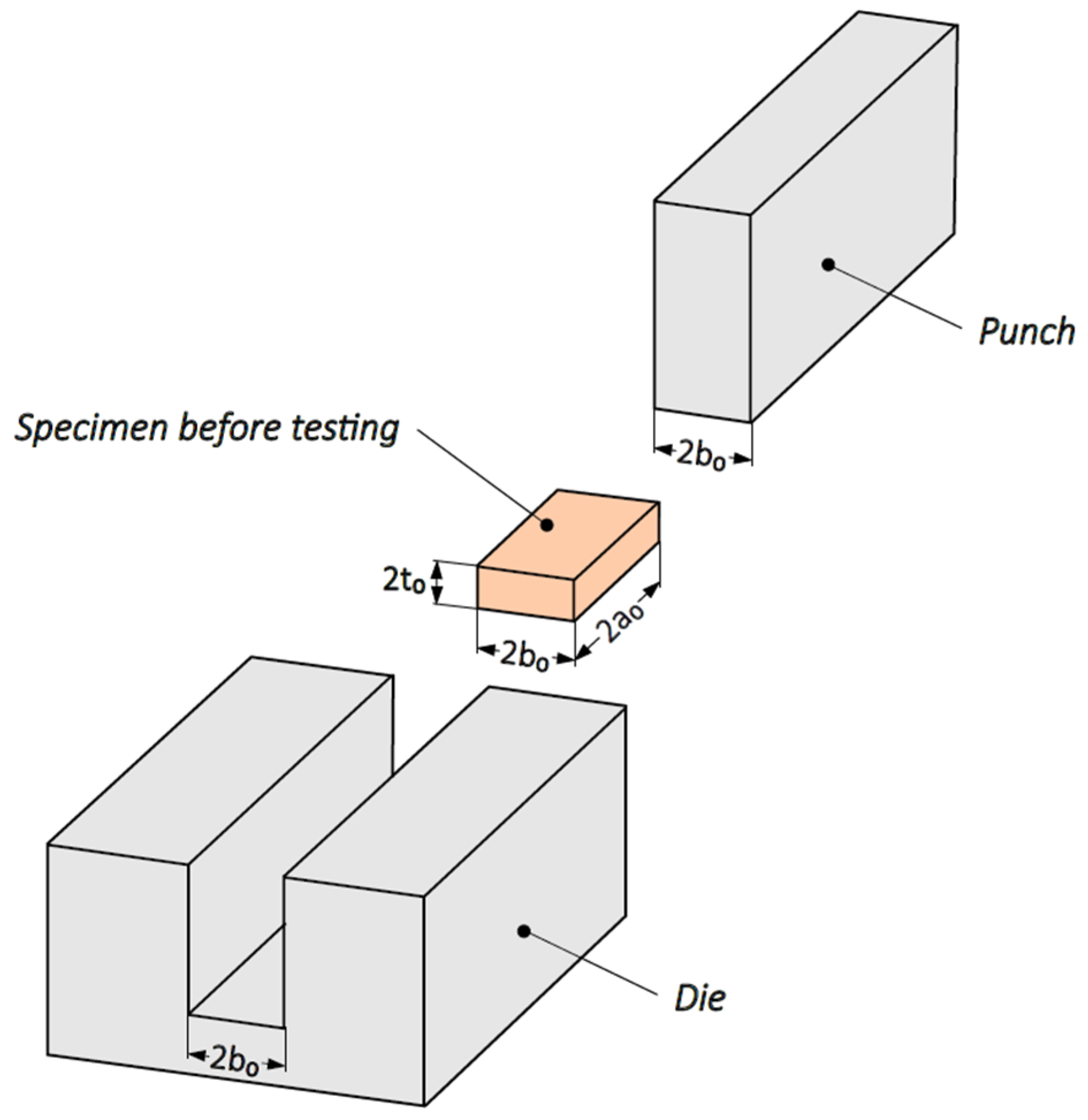

3. Plane Strain Compression for Determining the Friction Coefficient

3.1. Theory

3.2. Experiment

- Mixture of MoS2 grease and stearin—type GS,

- No lubricant—type D.

4. Cylinder Compression Test for Determining the Hardening Law

5. Determination of the Friction Factor

6. Conclusions

- The proposed method is efficient for evaluating the friction law (5), as the theoretical solution is relatively simple.

- The friction law (5) is not a good approximation of the friction stress, except for the steel specimens deformed with no lubricant.

- The lubricant denoted as type GS is more efficient than that denoted as type O.

- The overall structure of the theoretical solution suggests that it can be extended to a generalized friction law that accounts for the variation in the friction factor as deformation proceeds, providing a theoretical basis for further research.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Male, A.T.; Cockcroft, M.G. A method for the determination of the coefficient of friction of metals under conditions of bulk plastic deformation. J. Inst. Met. 1964, 93, 38–46. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.Q.; Ma, Q.X. Evaluation of Rheological Behavior and Interfacial Friction under the Adhesive Condition by Upsetting Method. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2015, 79, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrov, S.; Lyamina, E.; Jeng, Y.-R. A General Kinematically Admissible Velocity Field for Axisymmetric Forging and Its Application to Hollow Disk Forging. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2017, 88, 3113–3122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakkeri, S.; Patil, N.A.; Singh, S. Validation of Experimental Conditions with Standard Friction Models during Al 6061 Ring Compression Test under Various Interfacial Conditions. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2025, 39, 2609–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukugaichi, S.; Suga, Y.; Noura, S.; Takeyama, K.; Kitamura, K.; Aono, H. Frictional Property of Anionic-Surfactant-Loaded MgAl-Layered Double Hydroxide Films on Aluminum Alloy Using a Ring Compression Test. Tribol. Int. 2025, 210, 110810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Liu, B.; Li, J.; Cui, M.; Zhao, S. Variation of the Friction Conditions in Cold Ring Compression Tests of Medium Carbon Steel. Friction 2020, 8, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.-M.; Lu, C.-Y.; Lin, G.-D.; Wang, C.-C. Die Design and Finite-Element Analysis for the Hot Forging of Automotive Wheel Frames Made of Aluminium Alloy. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 137, 2681–2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, R.; Najafizadeh, A. A New Method for Evaluation of Friction in Bulk Metal Forming. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2004, 152, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buschhausen, A.; Weinmann, K.; Lee, J.Y.; Altan, T. Evaluation of Lubrication and Friction in Cold Forging Using a Double Backward-Extrusion Process. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 1992, 33, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avitzur, B.; Van Tyne, C.J. Ring Forming: An Upper Bound Approach. Part 1: Flow Pattern and Calculation of Power. J. Eng. Ind. 1982, 104, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avitzur, B.; Van Tyne, C.J. Ring Forming: An Upper Bound Approach. Part 2: Process Analysis and Characteristics. J. Eng. Ind. 1982, 104, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.H. Large Deformation of Structures by Sequential Limit Analysis. Int. J. Solids. Struct. 1993, 30, 1001–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R. The Mathematical Theory of Plasticity; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, R.; Lee, E.H.; Tupper, S.J. A Method of Numerical Analysis of Plastic Flow in Plane Strain and Its Application to the Compression of a Ductile Material Between Rough Plates. J. Appl. Mech. 1951, 18, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, E.A. The Compression of a Slab of Ideal Soil between Rough Plates. Acta Mech. 1967, 3, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, I.F.; Meguid, S.A. On the Influence of Hardening and Anisotropy on the Plane-Strain Compression of Thin Metal Strip. J. Appl. Mech. 1977, 44, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.J.; Briscoe, B.J.; Corfield, G.M.; Lawrence, C.J.; Papathanasiou, T.D. An Analysis of the Plane-Strain Compression of Viscoplastic Materials. J. Appl. Mech. 1997, 64, 420–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrov, S.; Jeng, Y.-R. Extension of Prandtl’s Solution to a General Isotropic Model of Plasticity Including Internal Variables. Meccanica 2024, 59, 909–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiss, W.; Pöhlandt, K. The Rastegaev Upset Test-A Method To Compress Large Material Volumes Homogeneously. Exp. Tech. 1986, 10, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 6743/7; Lubricants, Industrial Oils and Related Products (Class L)—Classification. Part 7: Family M (Metalworking). International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1986.

- ISO/TS 12927; Lubricants, Industrial Oils and Related Products (Class L)—Family M (Metalworking)—Guidelines for Establishing Specifications. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1999.

- Schey, J.A. Tribology in Metalworking: Friction, Lubrication, and Wear; American Society for Metals: Metals Park, OH, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Alexandrov, S.; Alexandrova, N. On The Maximum Friction Law for Rigid/Plastic, Hardening Materials. Meccanica 2000, 35, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Specimen No. | 2a [mm] | 2b [mm] | 2t [mm] | Stroke Smax [mm] | Fmax [kN] | Lubrication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O-1 | 40.50 | 14.42 | 3.66 | 2.40 | 827 | Oil |

| O-2 | 40.60 | 14.37 | 3.71 | 2.39 | 1025 | Oil |

| O-3 | 40.20 | 14.58 | 3.62 | 2.43 | 997 | Oil |

| GS-1 | 55.10 | 14.42 | 2.88 | 3.35 | 1095 | Grease + Stearin |

| GS-2 | 55.90 | 14.26 | 2.91 | 3.36 | 1098 | Grease + Stearin |

| GS-3 | 55.82 | 14.25 | 2.62 | 3.36 | 1097 | Grease + Stearin |

| D-1 | 36.90 | 14.41 | 3.79 | 2.05 | 1065 | Without lubrication |

| D-2 | 37.10 | 14.40 | 3.83 | 2.07 | 1068 | Without lubrication |

| D-3 | 36.90 | 14.41 | 3.78 | 2.05 | 1064 | Without lubrication |

| Specimen No. | 2a [mm] | 2b [mm] | 2t [mm] | Stroke Smax [mm] | Fmax [kN] | Lubrication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O-1 | 32.11 | 14.48 | 4.49 | 1.48 | 997 | Oil |

| O-2 | 31.82 | 14.86 | 4.41 | 1.56 | 998 | Oil |

| O-3 | 32.05 | 14.83 | 4.39 | 1.60 | 996 | Oil |

| GS-1 | 35.40 | 15.21 | 3.85 | 2.10 | 995 | Grease + Stearin |

| GS-2 | 35.87 | 14.88 | 3.87 | 2.05 | 997 | Grease + Stearin |

| GS-3 | 35.65 | 14.84 | 3.92 | 2.02 | 1046 | Grease + Stearin |

| D-1 | 30.80 | 15.15 | 4.39 | 1.50 | 1146 | Without lubrication |

| D-2 | 31.40 | 14.91 | 4.36 | 1.52 | 1157 | Without lubrication |

| D-3 | 31.81 | 14.87 | 4.36 | 1.55 | 1175 | Without lubrication |

| Type O, Al | Type GS, Al | Type D, Al | Type O, Steel | Type GS, Steel | Type D, Steel | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| f at η = 1 | 3.22 | 2.46 | 3.85 | 2.9 | 2.17 | 3.8 |

| Initial value of m | 0.67 | 0.22 | Very close to unity | 0.47 | 0.09 | Very close to unity |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Alexandrov, S.; Vilotic, D.; Rynkovskaya, M.; Li, Y.; Dacevic, N.; Vilotic, M. A New Methodology for Determining the Friction Factor. Metals 2026, 16, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010007

Alexandrov S, Vilotic D, Rynkovskaya M, Li Y, Dacevic N, Vilotic M. A New Methodology for Determining the Friction Factor. Metals. 2026; 16(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlexandrov, Sergei, Dragisa Vilotic, Marina Rynkovskaya, Yong Li, Nemanja Dacevic, and Marko Vilotic. 2026. "A New Methodology for Determining the Friction Factor" Metals 16, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010007

APA StyleAlexandrov, S., Vilotic, D., Rynkovskaya, M., Li, Y., Dacevic, N., & Vilotic, M. (2026). A New Methodology for Determining the Friction Factor. Metals, 16(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010007