Coupling Approach of Crystal Plasticity and Machine Learning in Predicting Forming Limit Diagram of AA7075-T6 at Various Temperatures and Strain Rates

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Uniaxial Tensile Test

2.3. Forming Limit Determination

3. Crystal Plasticity Finite Element Model

3.1. Dislocation Density-Based Crystal Plasticity Model

3.2. Hybrid M–K Model

3.3. Numerical Implementation

4. Results and Discussion

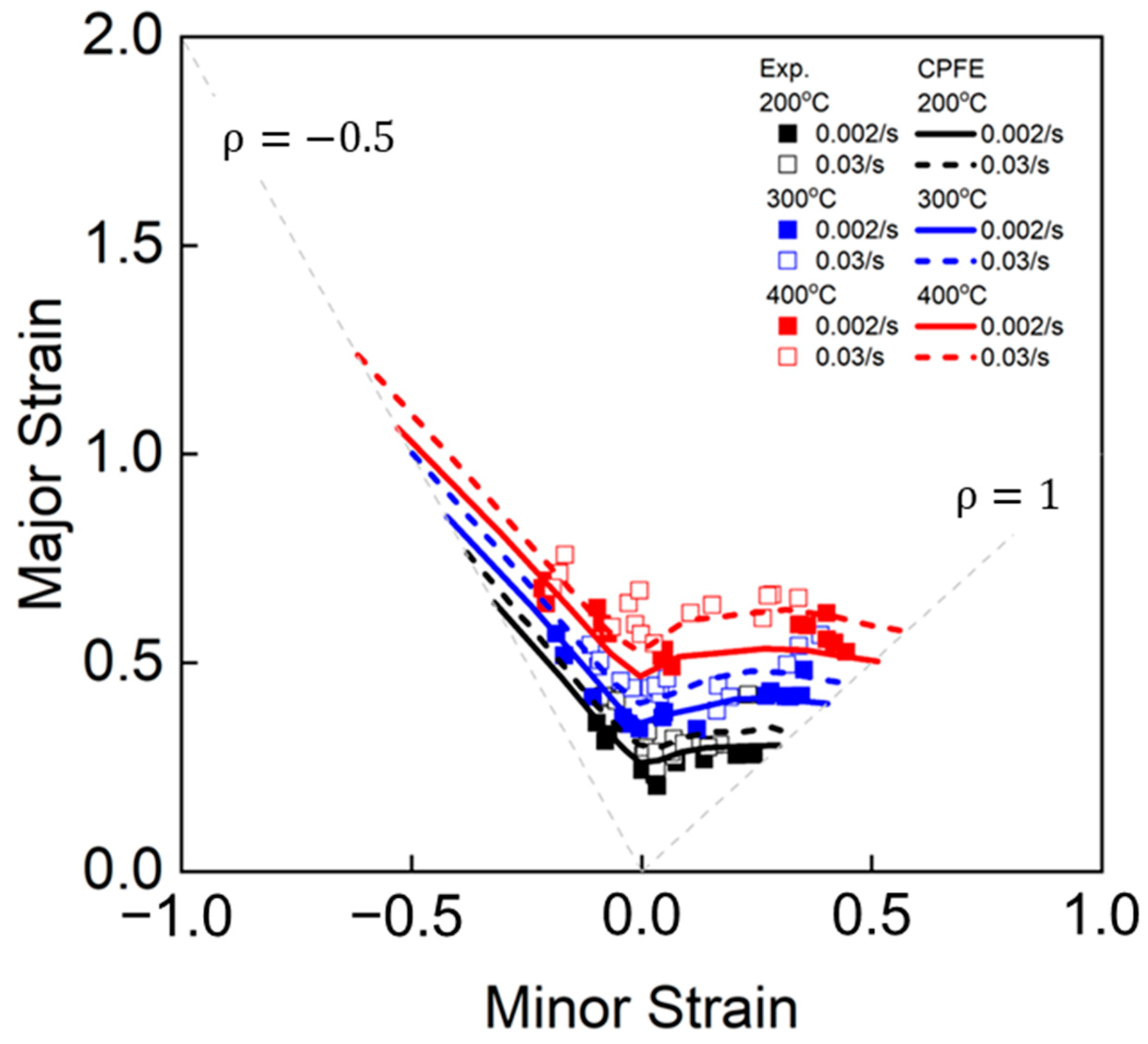

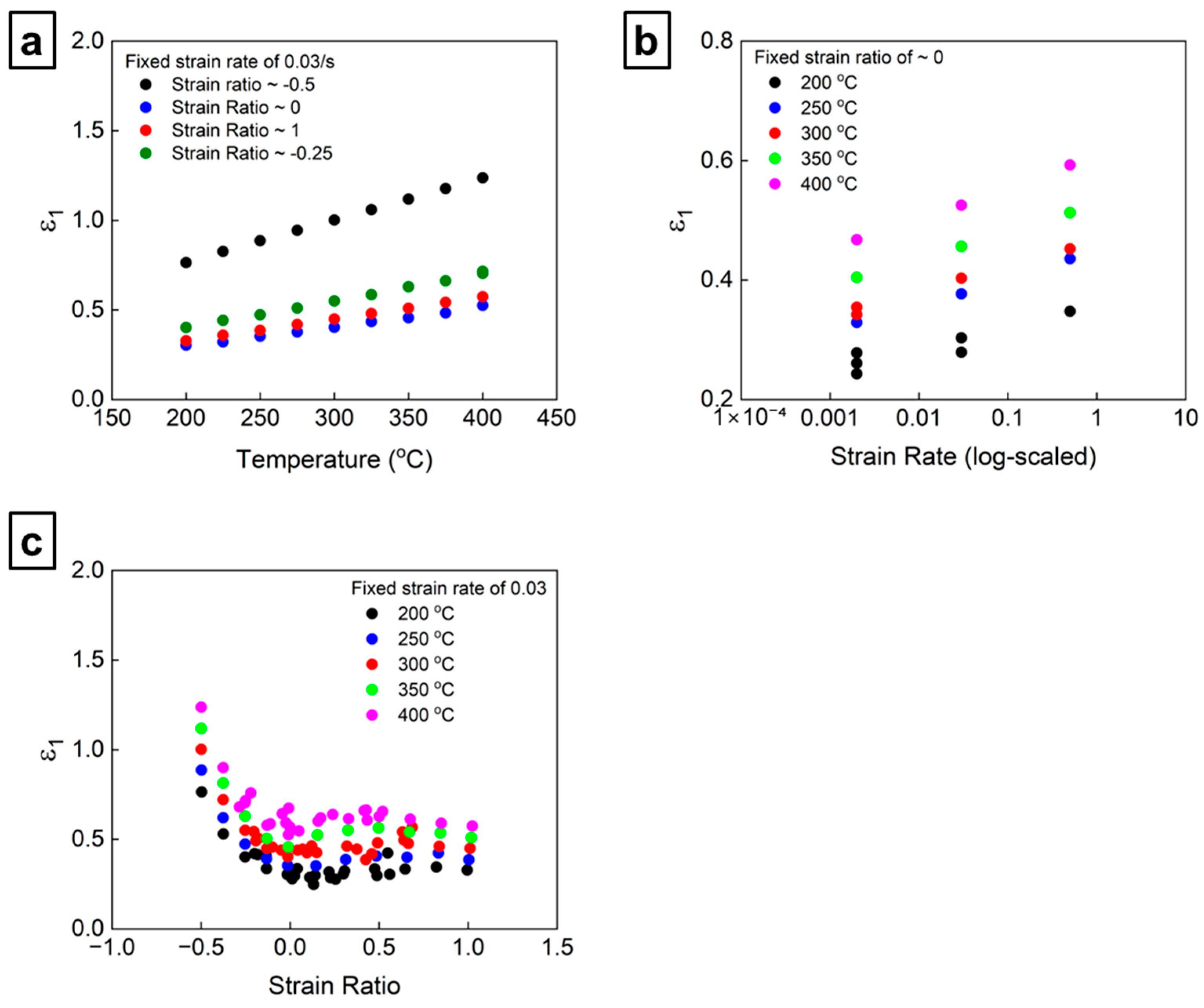

4.1. FLD: Experiment and Predictions

4.2. ML Modeling

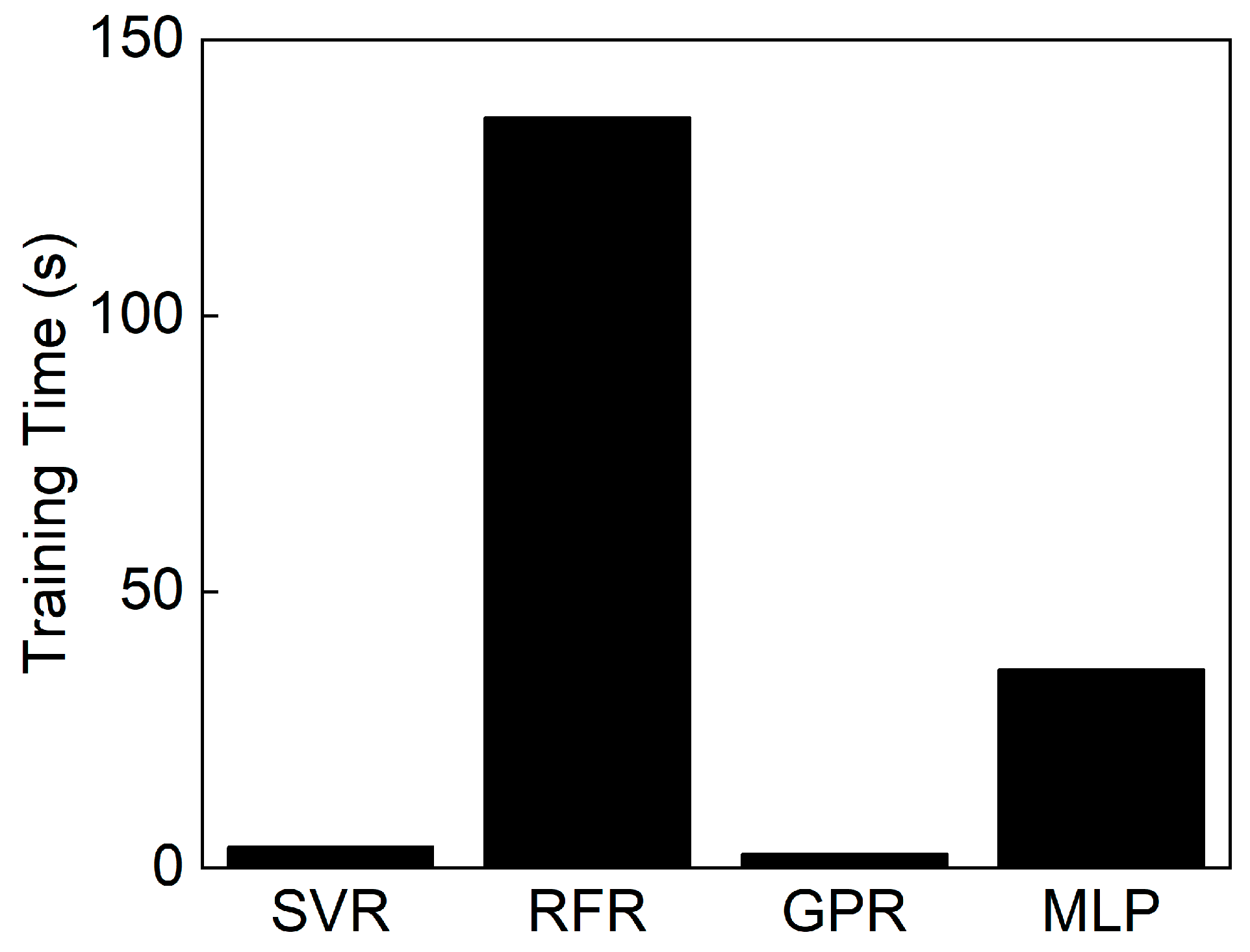

4.2.1. Description of ML Models

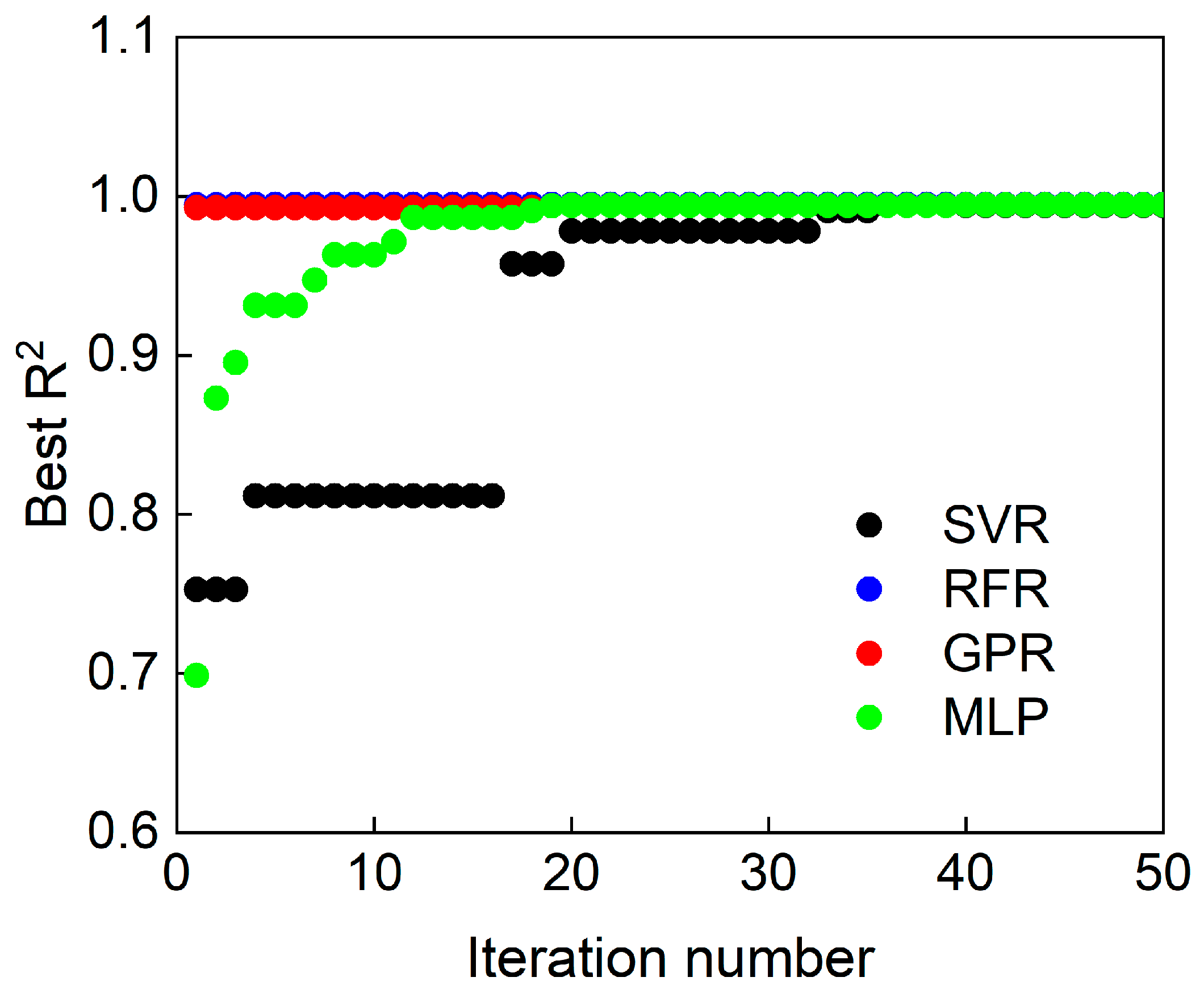

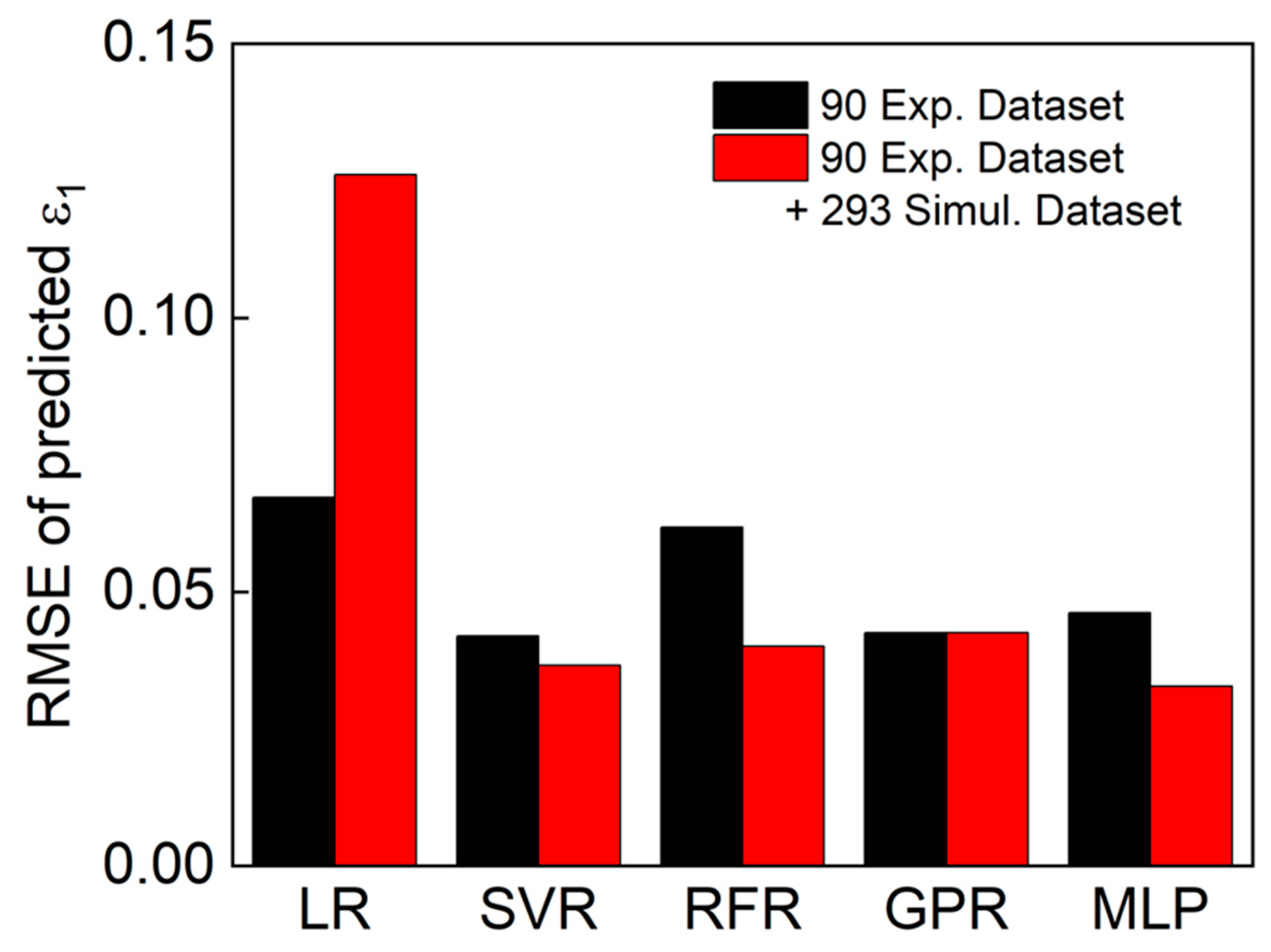

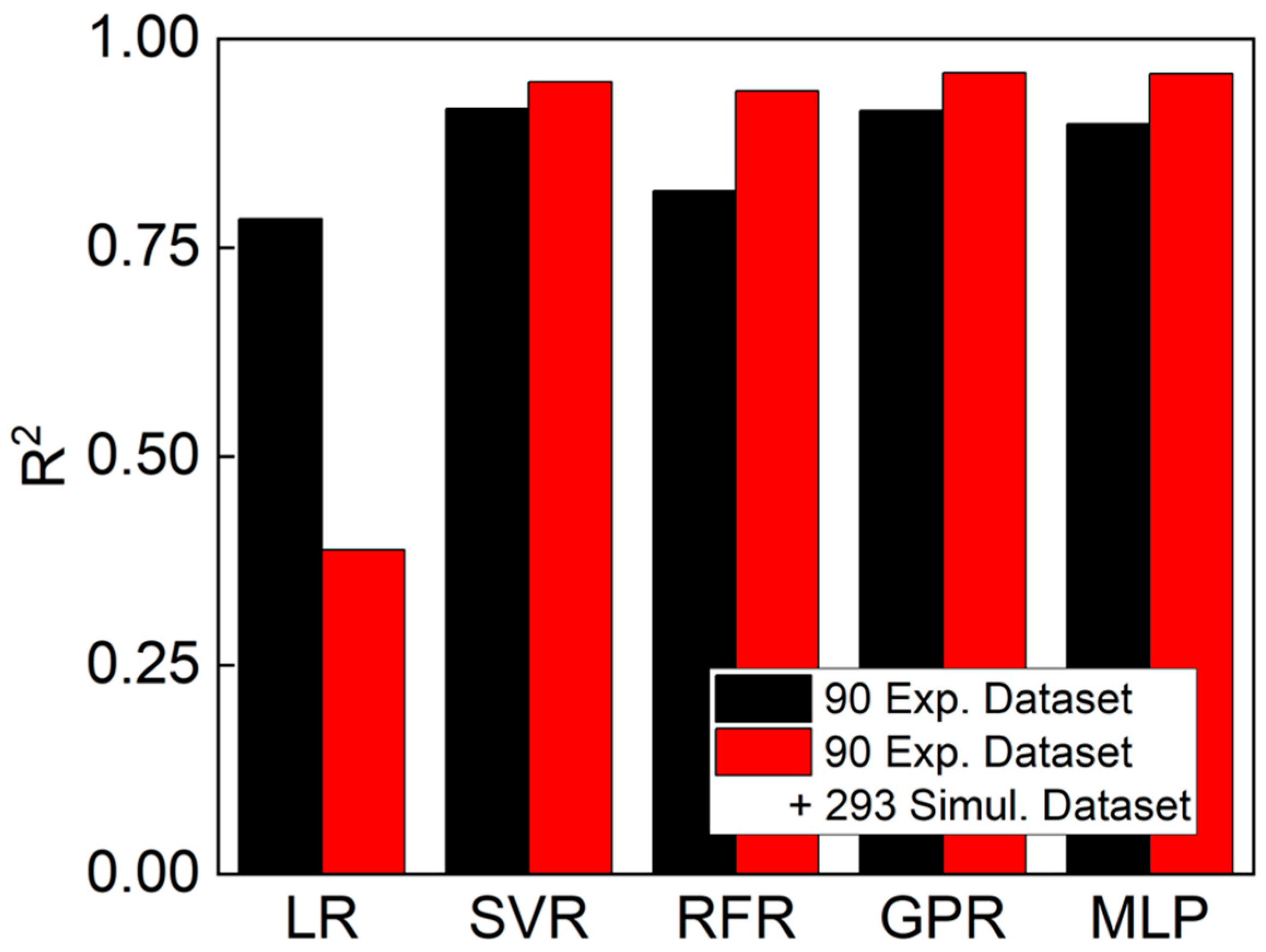

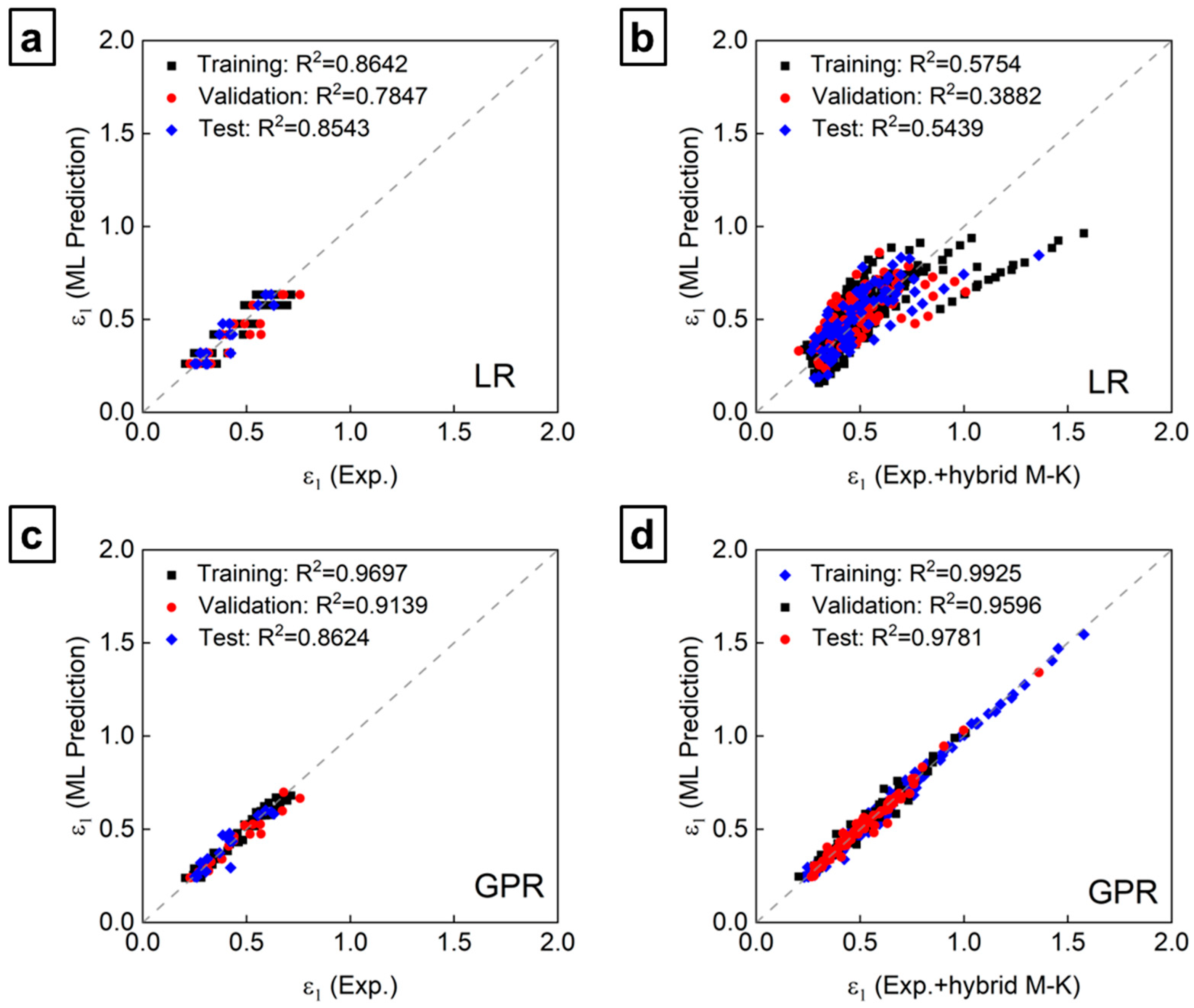

4.2.2. Predictions Using ML Models

5. Conclusions

- The hybrid M–K model incorporating the CPFE framework accurately reproduced the experimentally observed trends in FLD, including the enhanced formability with increasing temperature and strain rate.

- Virtual FLD data generated from the hybrid M–K simulations were combined with the experimental results to construct a comprehensive dataset, enabling robust ML model training.

- Among the evaluated ML algorithms, the Gaussian process regression (GPR) model demonstrated the best predictive performance (R2 > 0.95), effectively learning the nonlinear relationships between temperature, strain rate, and strain ratio.

- The integrated hybrid M–K–ML methodology provides a physically informed and computationally efficient framework for predicting the formability of AA7075-T6 across wide thermo-mechanical conditions and can be extended to other anisotropic and rate-sensitive alloys.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FLD | forming limit diagram |

| M–K | Marciniak–Kuczyński |

| CPFE | crystal plasticity finite element |

| ML | machine learning |

| LR | linear regression |

| RFR | random forest regression |

| SVR | support vector regression |

| GPR | Gaussian process regression |

| MLP | multilayer perceptron |

| RD | rolling direction |

| MSE | mean square error |

| RMSE | root mean square error |

| CV | cross-validation |

References

- Xu, T.; Li, F.; Wang, X.; Zhang, G. Characterization of Anisotropic Fracture Behavior of 7075-T6 Aluminum Alloy Sheet under Various Stress States. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2022, 32, 3230–3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajadifar, S.V.; Scharifi, E.; Weidig, U.; Steinhoff, K.; Niendorf, T. Performance of Thermo-Mechanically Processed AA7075 Alloy at Elevated Temperatures—From Microstructure to Mechanical Properties. Metals 2020, 10, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, C.; Thuillier, S.; Lee, J.; Lee, M.G. Mechanical Properties of Solution Heat Treated Al-Zn-Mg-Cu (7075) Alloy under Different Cooling Conditions: Analysis with Full Field Measurement and Finite Element Modeling. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 856, 158180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Luo, Y.B.; Friedman, P.; Chen, M.H.; Gao, L. Warm Forming Behavior of High Strength Aluminum Alloy AA7075. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2012, 22, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Lin, Y.C.; Deng, J.; Jiang, Y.Q. Hot Tensile Deformation Behaviors and Constitutive Model of an Al–Zn–Mg–Cu Alloy. Mater. Des. 2014, 59, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotirov, N.; Simon, P.; Chimani, C.; Uffelmann, D.; Melzer, C. Warm Deep Drawability of Peak-Aged 7075 Aluminium Sheet Alloy. Key Eng. Mater. 2012, 504–506, 955–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.S.; Baig, M. Anisotropic Responses, Constitutive Modeling and the Effects of Strain-Rate and Temperature on the Formability of an Aluminum Alloy. Int. J. Plast. 2011, 27, 522–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Ghosh, A. Tensile Deformation Behavior of Aluminum Alloys at Warm Forming Temperatures. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2003, 352, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rader, K.E.; Carter, J.T.; Hector, L.G.; Taleff, E.M. Plastic Deformation and Ductility of AA7075 and AA6013 at Warm Temperatures Suitable to Retrogression Forming. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2021, 52, 4003–4017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, H.; Hu, P.; Ying, L.; Hou, W.; Zhang, J. Thermal Forming Limit Diagram (TFLD) of AA7075 Aluminum Alloy Based on a Modified Continuum Damage Model: Experimental and Theoretical Investigations. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2019, 156, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, K.M.; Kim, C.; Choi, S.; Hong, J.H.; Lee, J.; Bong, H.J. Forming Limit Diagram of an Ultra-Thin Commercially Pure Titanium Sheet: Combined Experimental–Numerical Approach. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 39, 7110–7123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yatkın, M.A.; Kõrgesaar, M. Machine Learning Enabled Identification of Sheet Metal Localization. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2024, 288, 112592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Roth, C.C.; Mohr, D. Neural Network Based Rate- and Temperature-Dependent Hosford–Coulomb Fracture Initiation Model. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2023, 260, 108643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samad, A.; Thakur, A.K.; Basak, S.; Pal, K. Machine Learning Enabled Estimation of Formability for Anisotropic Sheet Metals. Met. Mater. Int. 2025, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.T.; Tran, M.T.; Nguyen, X.M.; Lee, H.W.; Kang, S.H.; Oh, Y.S.; Kim, H.; Kim, D.K. Physics-Guided Machine Learning for Forming-Limit Assessments of Advanced High-Strength Steels. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2025, 287, 109959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaremenko, C.; Ravikumar, N.; Affronti, E.; Merklein, M.; Maier, A. Determination of Forming Limits in Sheet Metal Forming Using Deep Learning. Materials 2019, 12, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chheda, A.M.; Nazro, L.; Sen, F.G.; Hegadekatte, V. Prediction of Forming Limit Diagrams Using Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2019; Volume 651, p. 12107. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, L.; Lee, W.W.; Lin, H.; Jin, T. Plastic Anisotropy of AA7075-T6 Alloy under Quasi-Static Compression: Experiments, Classical Plasticity and Artificial Neural Networks Modeling. Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process. 2023, 129, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steglich, D.; Jeong, Y. Texture-Based Forming Limit Prediction for Mg Sheet Alloys ZE10 and AZ31. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2016, 117, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, M.T.; Lee, H.J.; Phan, H.C.; Kang, S.H.; Kim, D.K.; Lee, H.W. Microstructure-Informed Forming Limits in Aluminum Alloys: Experiments and Crystal Plasticity Simulations. Mater. Charact. 2025, 230, 115831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Lee, M.G.; Kang, J.H.; Oh, C.S.; Barlat, F. Crystal Plasticity Finite Element Analysis of Ferritic Stainless Steel for Sheet Formability Prediction. Int. J. Plast. 2017, 93, 26–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajian, M.; Assempour, A. Experimental and Numerical Determination of Forming Limit Diagram for 1010 Steel Sheet: A Crystal Plasticity Approach. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2015, 76, 1757–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohoman, M.M.; Zhou, C. Crystal Plasticity Modeling of Dislocation Density Evolution in Cellular Dislocation Structures. Metals 2025, 15, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Duan, W.; Zhang, S.; Yang, X.; Li, W.; Shen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, J. Finite Element Simulation of Crystal Plasticity in the Tensile Fracture Behavior of PBF-LB/M CoCrFeNiMn High Entropy Alloy. Metals 2025, 15, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Dong, J.; Yao, S.; Liu, S.; Cao, L.; Huang, X. Effect of External Constraints on Deformation Behavior of Aluminum Single Crystals Cold-Rolled to High Reduction: Crystal Plasticity FEM Study and Experimental Verification. Metals 2025, 15, 885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, G.; Huang, Z.; Deng, B.; Ge, R. Crystal Plasticity Finite Element Simulation of Tensile Fracture of 316L Stainless Steel Produced by Selective Laser Melting. Metals 2025, 15, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitreiro, D.; Prates, P.A.; Andrade-Campos, A. Reducing Mesh Dependency in Dataset Generation for Machine Learning Prediction of Constitutive Parameters in Sheet Metal Forming. Metals 2025, 15, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 12004-2; Metallic Materials—Sheet and Strip—Determination of Forming-Limit Curves—Part 2: Determination of Forming-Limit Curves in the Laboratory. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008.

- Davoudi, K. Temperature Dependence of the Yield Strength of Aluminum Thin Films: Multiscale Modeling Approach. Scr. Mater. 2017, 131, 63–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallon, J.L.; Wolfenden, A. Temperature Dependence of the Elastic Constants of Aluminum. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 1979, 40, 831–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Ben Bettaieb, M.; Abed-Meraim, F.; Kalidindi, S.R. Computationally Efficient Predictions of Crystal Plasticity Based Forming Limit Diagrams Using a Spectral Database. Int. J. Plast. 2018, 103, 168–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonen, M.N.; Steglich, D.; Bohlen, J.; Stutz, L.; Letzig, D.; Mosler, J. Experimental and Numerical Investigation of Mg Alloy Sheet Formability. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2013, 586, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element | wt% |

|---|---|

| Zn | 5.1–6.1 |

| Mg | 2.1–2.9 |

| Cu | 1.2–2.0 |

| Cr | 0.18–0.28 |

| Si | <0.40 |

| Fe | <0.50 |

| Mn | <0.30 |

| Ti | <0.20 |

| Al | Bal. |

| Temperature (°C) | (MPa) | (m−2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 175 | 2 × 1013 | 12 | 32 |

| 100 | 154 | 36.4 | ||

| 150 | 130 | 43.2 | ||

| 200 | 99.8 | 56.1 | ||

| 250 | 75.3 | 74 | ||

| 300 | 12.3 | 457 | ||

| 400 | 1.75 | 3200 | ||

| 470 | 0.175 | 32,000 |

| Let . Given: (1) , for each element (2) in each grain (3) —time independent quantities, for each grain 1. Calculate trial stress where 2. Update stress in each grain Solve Newton–Raphson method where 2.1. Update dislocation density where 2.2. Update plastic deformation gradient 3. Convergence check If then: Cauchy stress 4. Update crystal orientation , |

| 1. Initialization , , 1.2. Set initial stress, strain in RVE-A and RVE-B to zero. of grain k in RVE-A using CPFE model of RVE-B from: of RVE-B from CPFE model 3. Check for localized fracture then: Else: Return to Step 2 |

| Model | Hyperparameters | Search Range | Hyperparameters (90 Experimental Data Points) | Hyperparameters (90 Experimental + 297 Hybrid M–K Predicted Data Points) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RFR | n_estimators | [100, 200, 300] | 200 | 200 |

| Maximum depth | [None, 10, 20] | None | 10 | |

| Maximum features | [None, 1, 2, 3, “sqrt”, “log2”, 0.5, 1.0] | None | 1 | |

| Minimum samples leaf | [1, 2, 4] | 1 | 1 | |

| Minimum samples split | [2, 5, 10] | 2 | 2 | |

| SVR | C | [0.1, 1, 10, 100] | 10 | 100 |

| [0.01, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5] | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||

| [0.01, 0.1, 1] | 0.1 | 0.1 | ||

| GPR | Regularization noise() | [10−10, 10−5, 10−2] | 10−5 | 10−5 |

| Length scale (l) | [0.1, 1, 10] | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| ) | [10−3, 10−1] | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| MLP | Batch size | [32, 64, 128] | 16 | 32 |

| Epochs | [50, 100, 200] | 50 | 50 | |

| Learning rate | [10−3, 10−4] | 10−3 | 10−3 | |

| Model hidden unit | [32, 64, 128] | 128 | 128 | |

| Model hidden layers | [1, 2, 3] | 2 | 3 | |

| Model dropout | [0, 0.1] | 0.0 | 0.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bong, H.J.; Choi, S.; Min, K.M. Coupling Approach of Crystal Plasticity and Machine Learning in Predicting Forming Limit Diagram of AA7075-T6 at Various Temperatures and Strain Rates. Metals 2026, 16, 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010021

Bong HJ, Choi S, Min KM. Coupling Approach of Crystal Plasticity and Machine Learning in Predicting Forming Limit Diagram of AA7075-T6 at Various Temperatures and Strain Rates. Metals. 2026; 16(1):21. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010021

Chicago/Turabian StyleBong, Hyuk Jong, Seonghwan Choi, and Kyung Mun Min. 2026. "Coupling Approach of Crystal Plasticity and Machine Learning in Predicting Forming Limit Diagram of AA7075-T6 at Various Temperatures and Strain Rates" Metals 16, no. 1: 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010021

APA StyleBong, H. J., Choi, S., & Min, K. M. (2026). Coupling Approach of Crystal Plasticity and Machine Learning in Predicting Forming Limit Diagram of AA7075-T6 at Various Temperatures and Strain Rates. Metals, 16(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010021