Interactions Effect Among the Electrolytes on Micro-Arc Oxidation Coatings of AZ91D Mg Alloy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Preparation

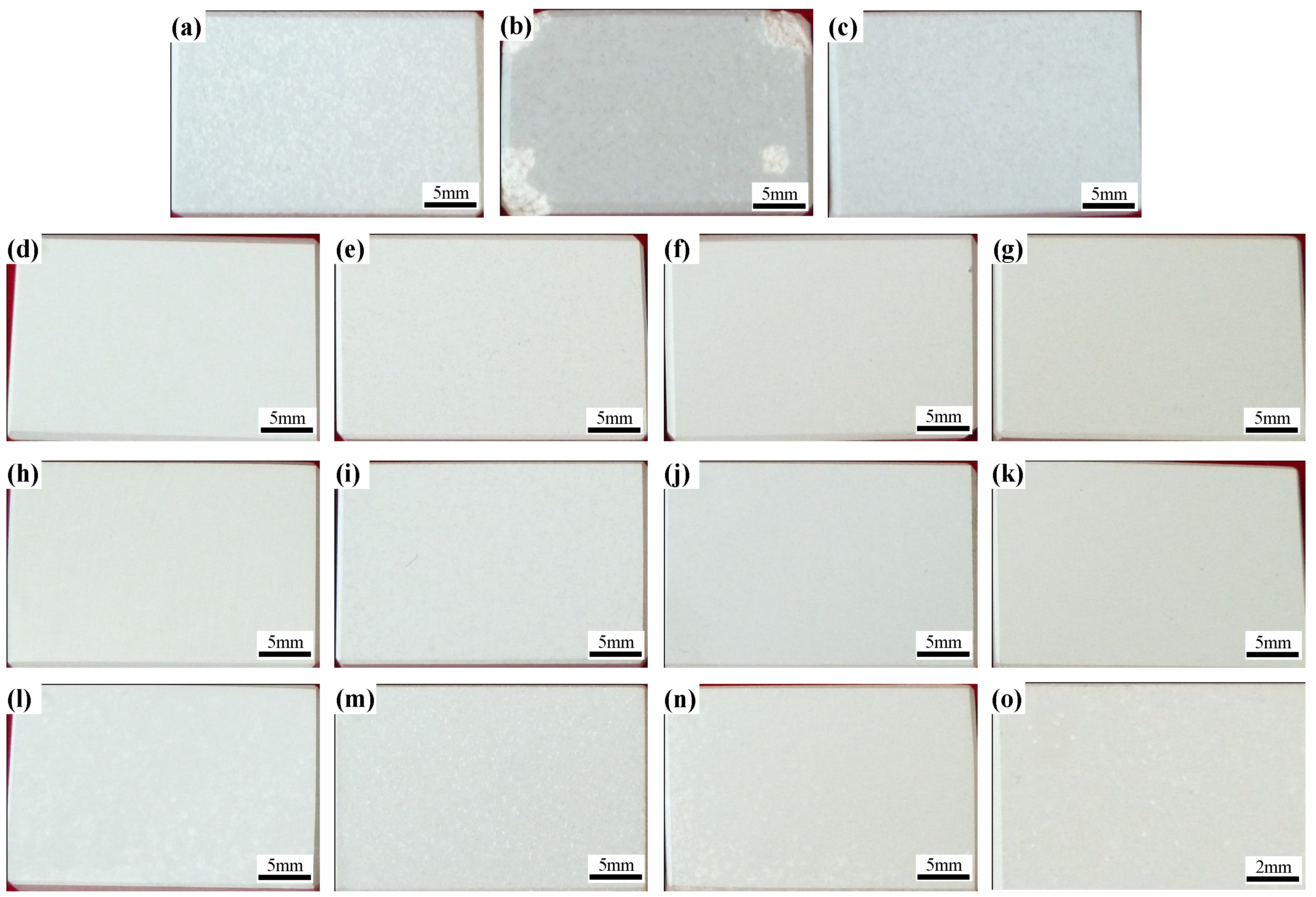

2.2. Formability of MAO Coating

2.3. Coating Characterization

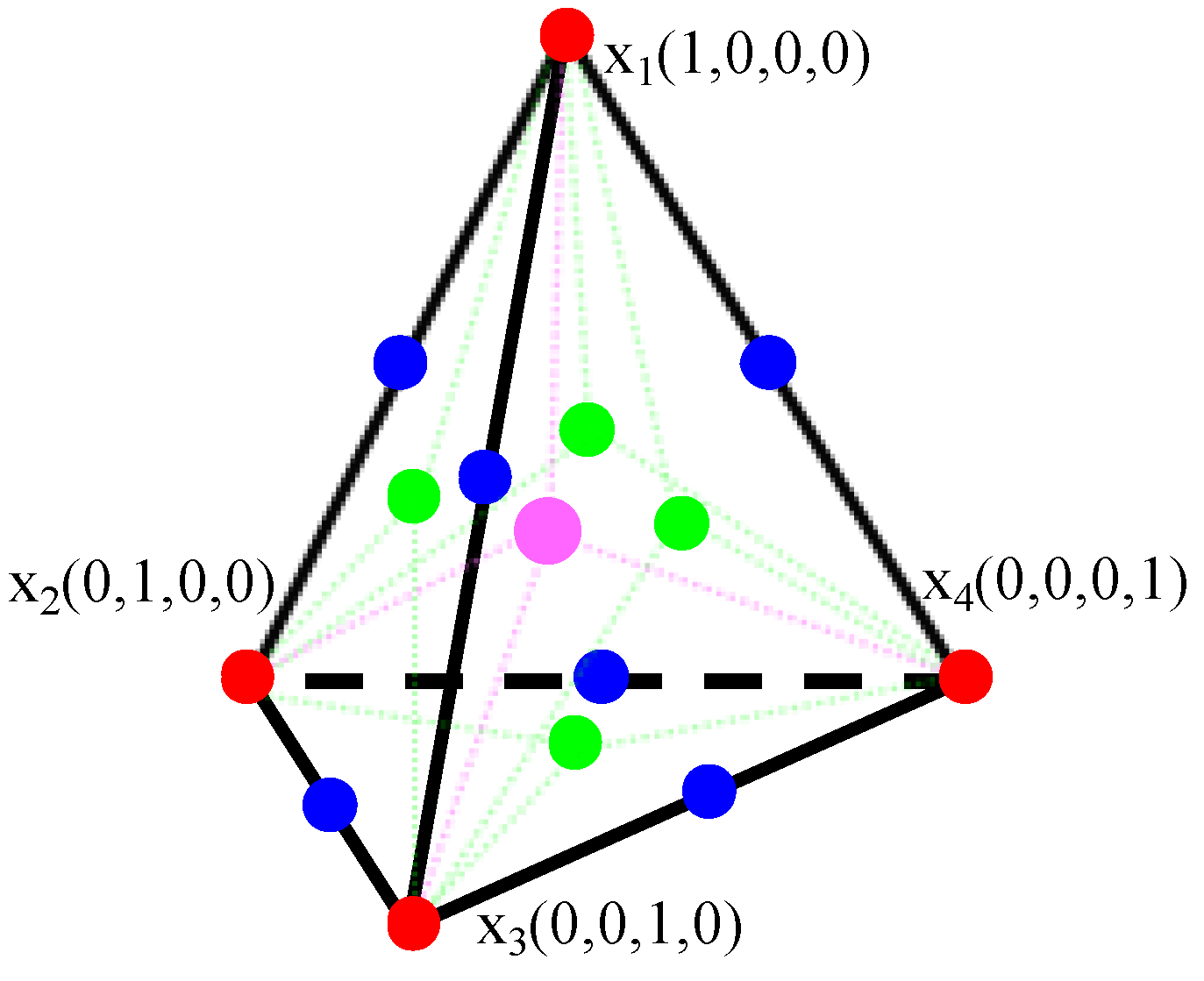

2.4. Experimental Design

2.5. Regression Analysis

3. Results

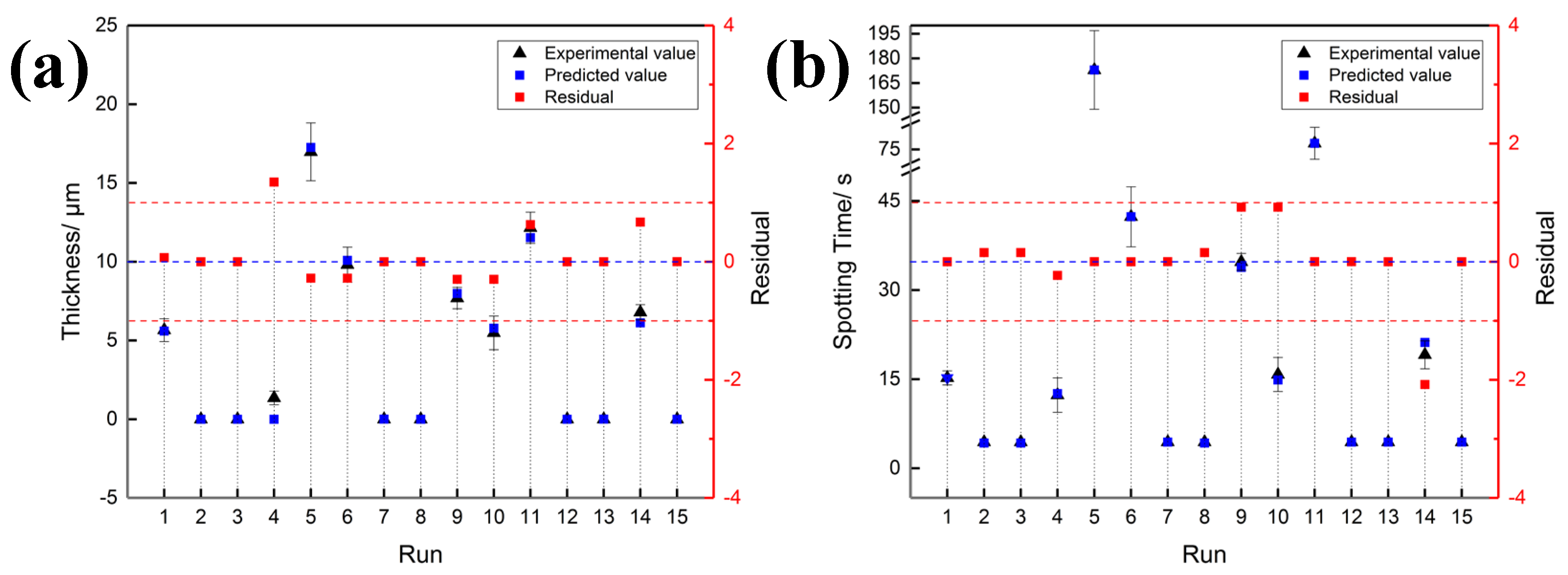

3.1. Establishment and Analysis of Regression Model

3.1.1. ANOVA

3.1.2. Adequacy of Equations

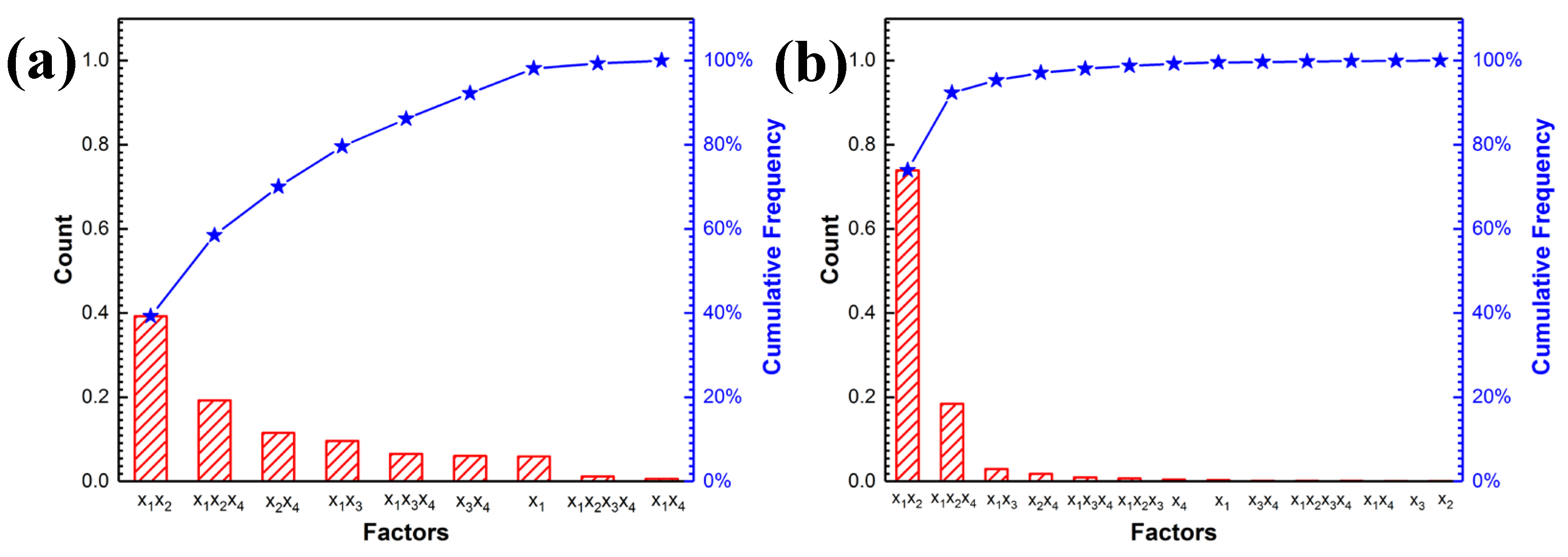

3.1.3. Pareto Analysis

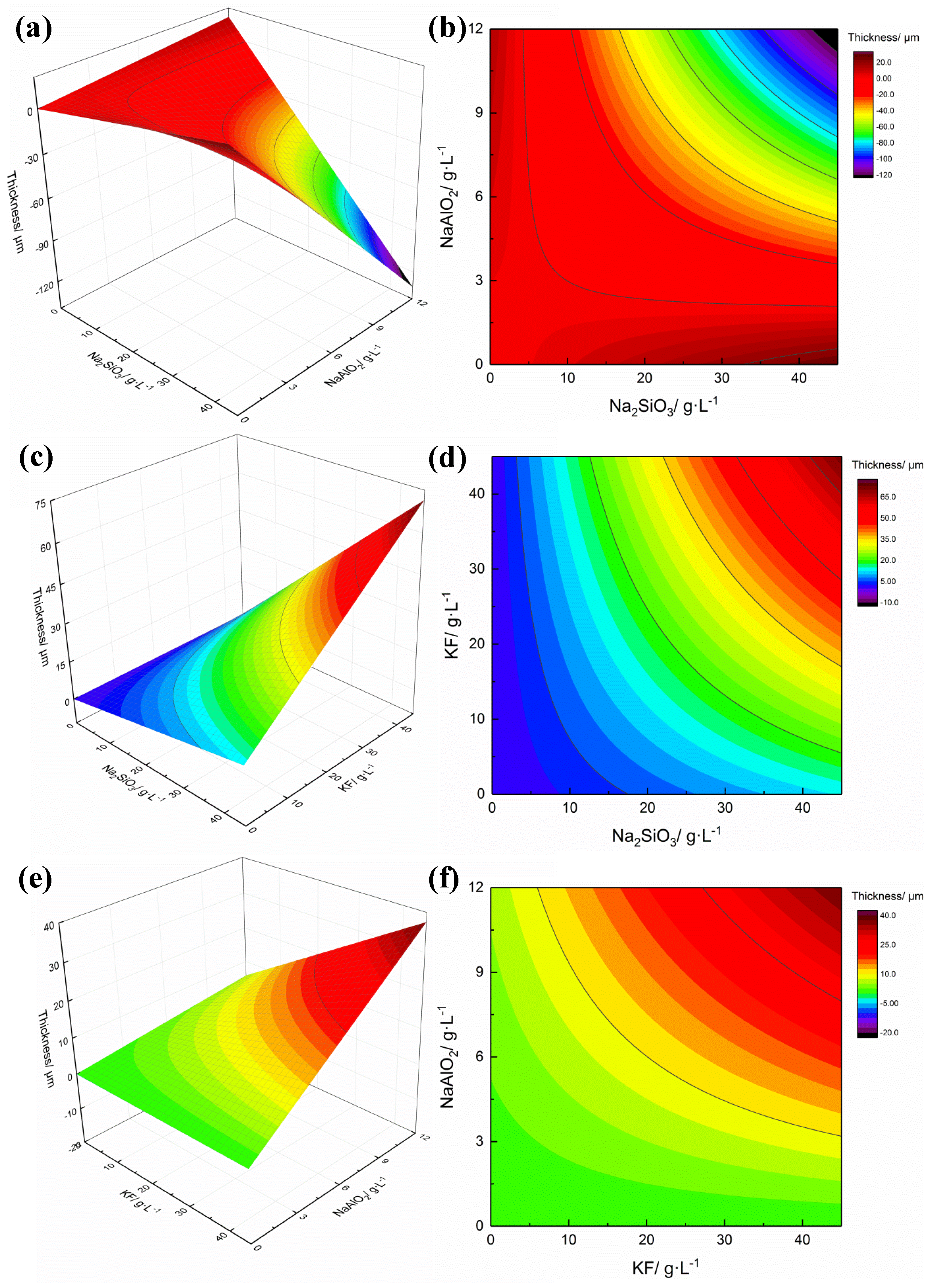

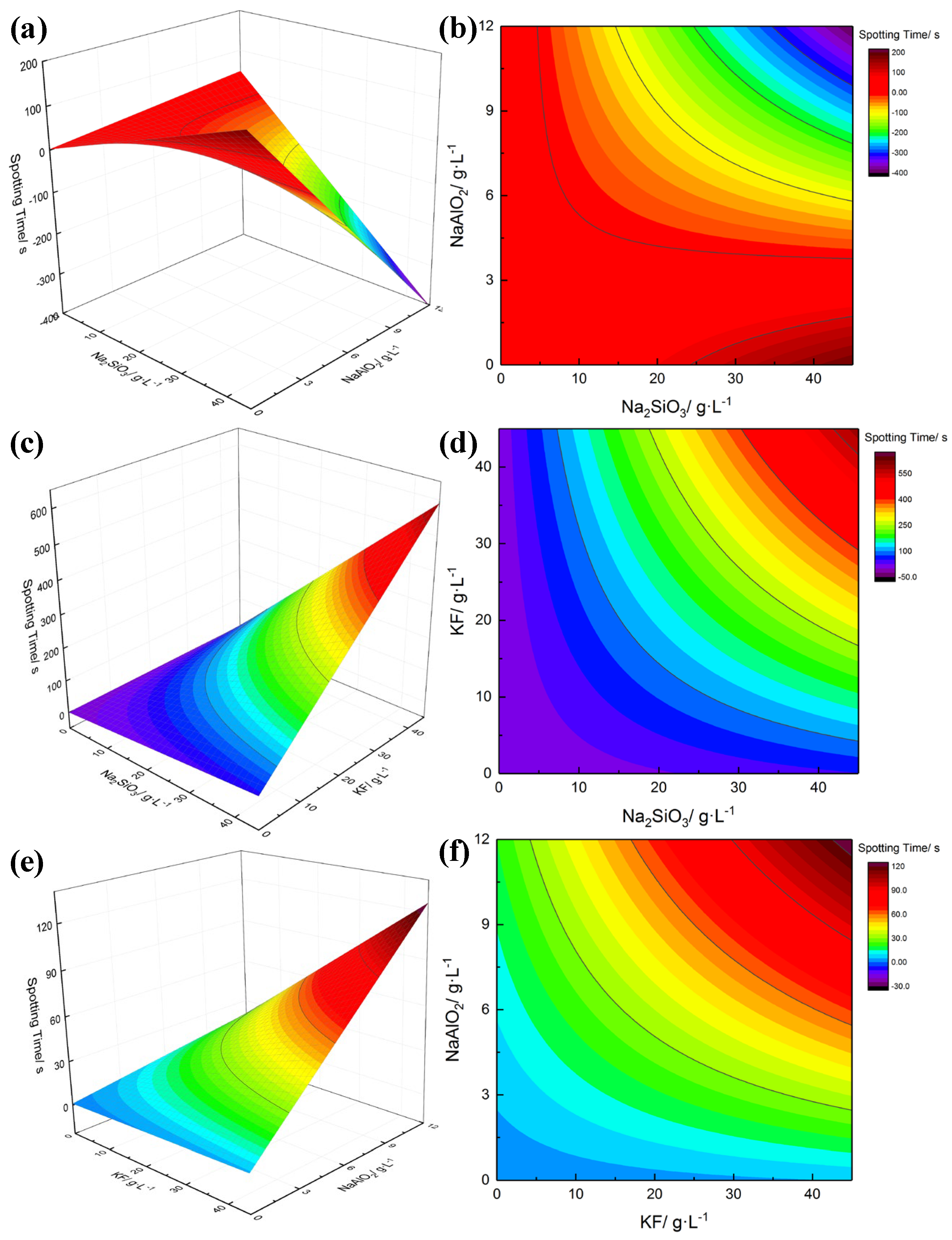

3.2. Response Surface Analysis

3.3. Effect of the Interactions Among Na2SiO3, KF and NaAlO2

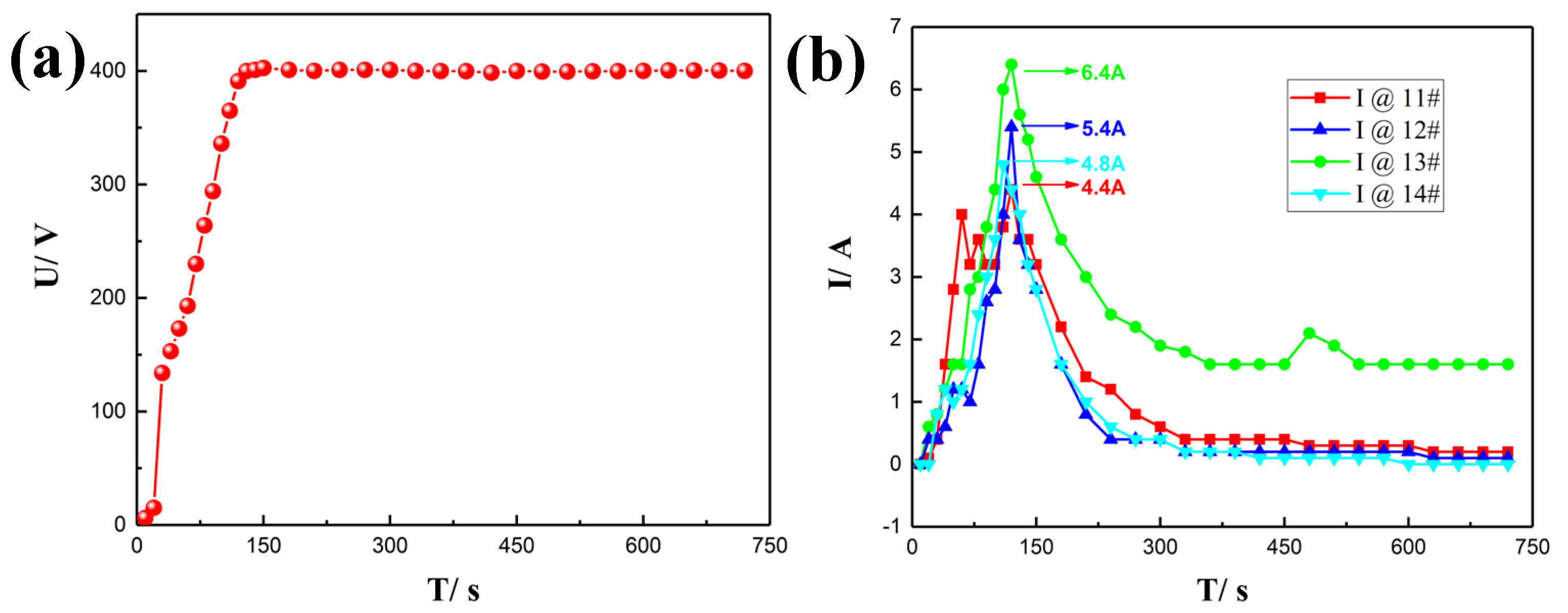

3.3.1. Voltage/Current–Time Curves

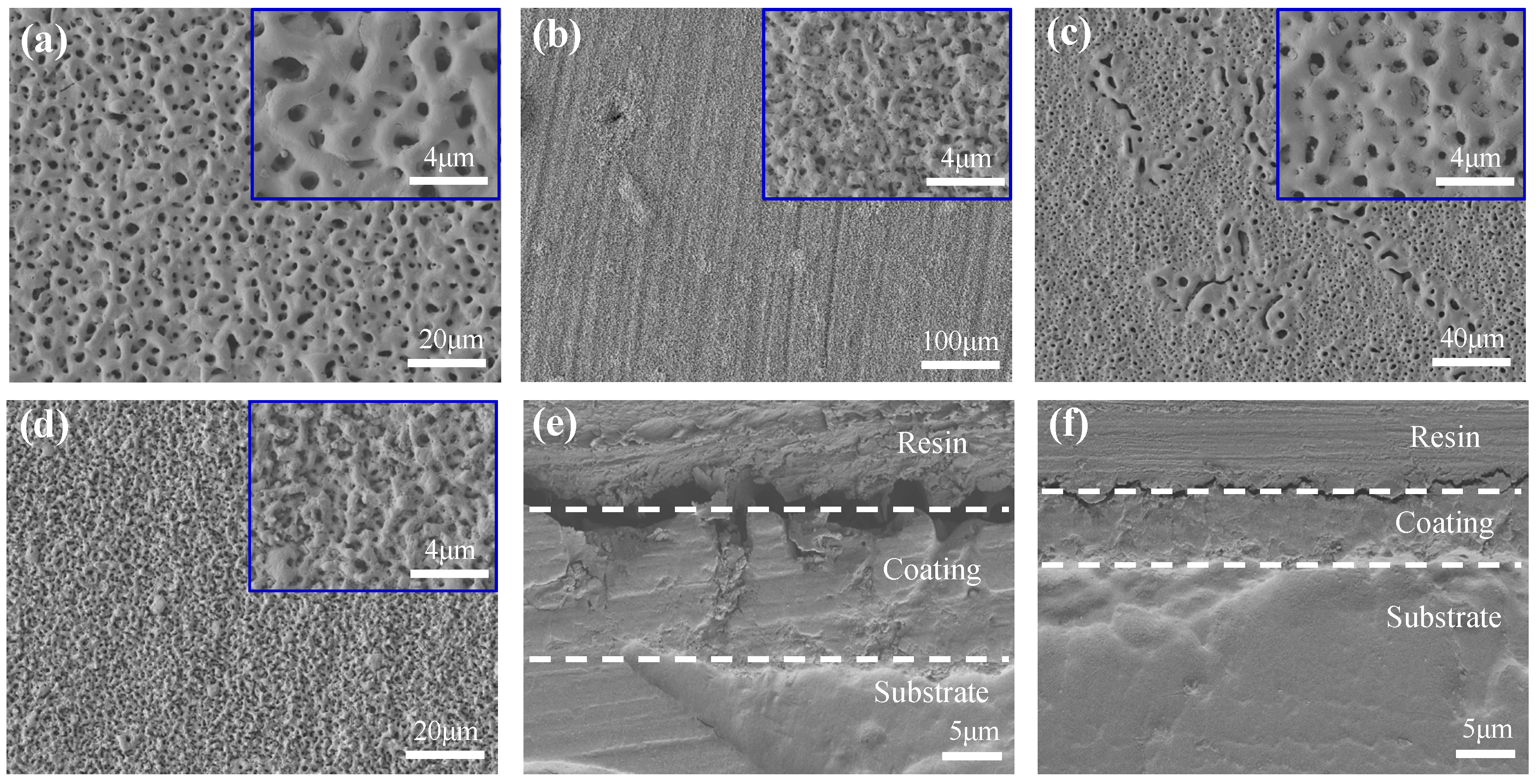

3.3.2. Surface Morphology

3.3.3. Chemical Composition

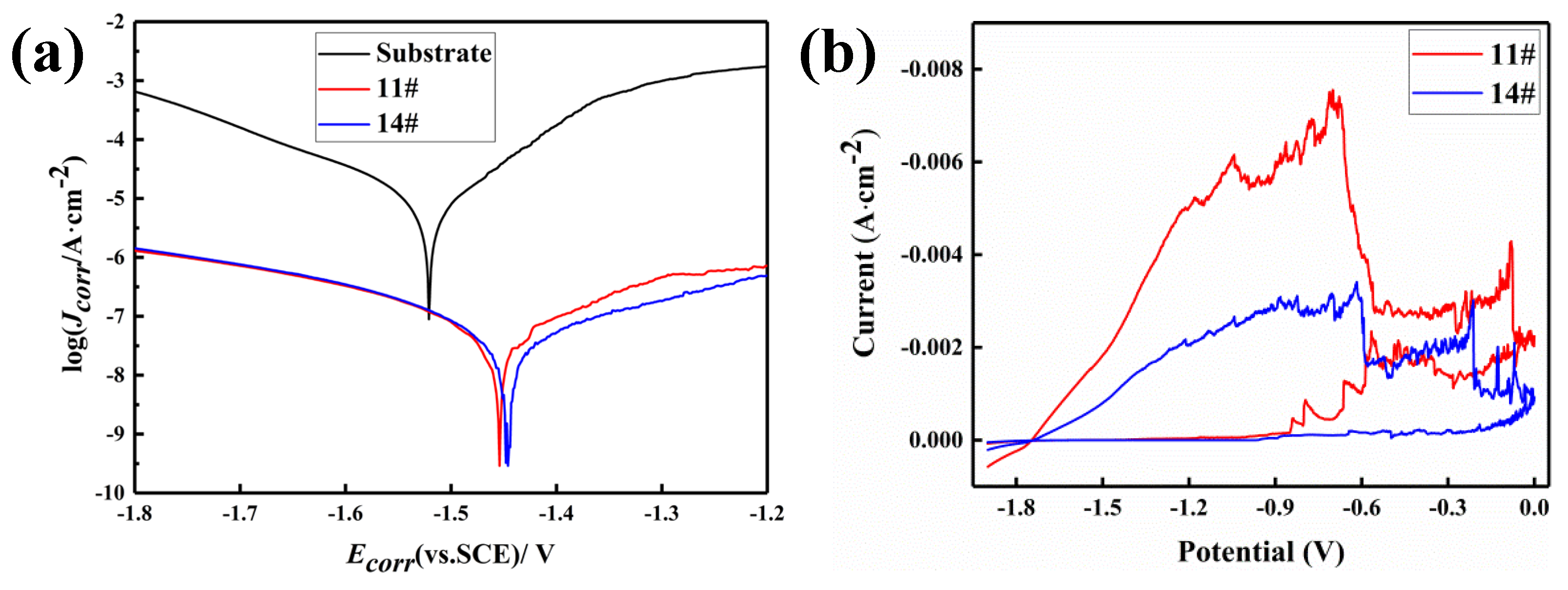

3.3.4. Corrosion Study

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Multi-factor experimental design is the key to studying the components of electrolytes and their interactions. By comparing the experimental schemes that only contain one, two, three and four electrolytes, the influence of each electrolyte component and the interactions on the coating is analyzed.

- Based on regression analysis, the electrolytes are linked to the final coating performances, and the regression models between the electrolyte components and the thickness and corrosion resistance are fitted. The equations are all very significant (p-value < 0.01), and have high prediction accuracy (R2 = 0.9893, 0.9989), which can be used for the optimization of the electrolyte formula and the prediction of the coating performance.

- Pareto analysis indicates that the interactions between Na2SiO3, KF and NaAlO2 produce a great influence on the thickness and spotting time of coatings, which is quantitatively confirmed that there are interactions among the electrolytes. The analysis of response surface methodology (RSM) showed that better thickness and spotting corrosion resistance could be achieved when the ideal combination is high concentration of Na2SiO3, high concentration of KF and low concentration of NaAlO2. When Na2SiO3 is compounded with NaAlO2, both of them will form polymers through complex polymerization reactions, resulting in increased viscosity of electrolyte, reduced migration rate of the particles and poor formability of the coating with uneven surface.

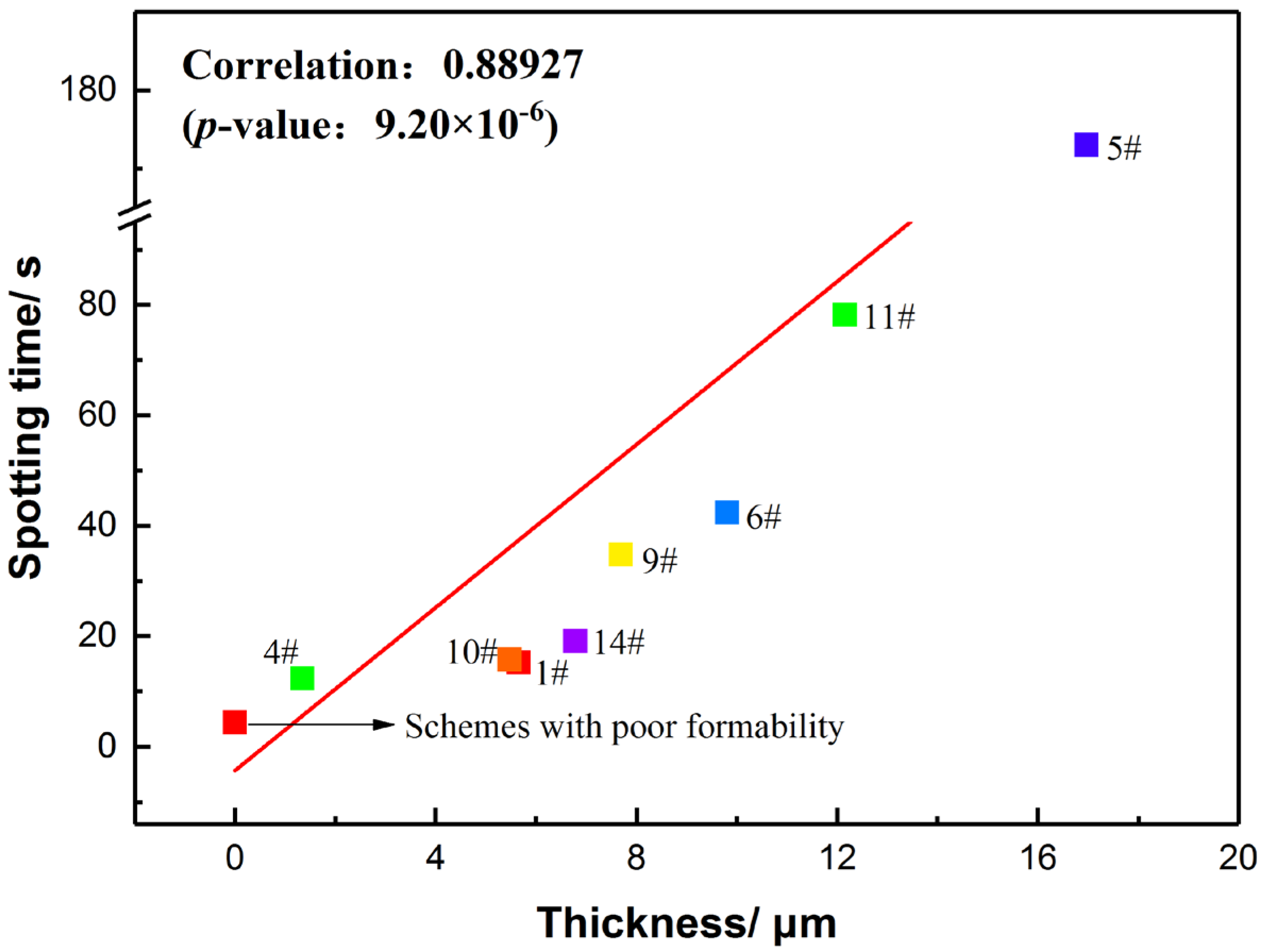

- Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC) was first applied to deal with the correlation between the thickness and corrosion resistance. The result of PCC revealed that the corrosion resistance in acidic media primarily depends on the thickness (r = 0.88927).

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shao, Y.; Han, X.; Ma, C.; Wei, Y.; Zhu, X.; Xu, J. The thermal dynamic simulation and microstructure characterization of micro-arc oxidation (MAO) films on magnesium AZ31 irradiated by high-intensity pulsed ion beam. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2025, 682, 161705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florczak, Ł.; Pojnar, K.; Ko’scielniak, B.; Pilch-Pitera, B. Preparation and Characterization of Duplex PEO/UV-Curable Powder Coating on AZ91 Magnesium Alloys. Metals 2024, 14, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parichehr, R.; Dehghanian, C.; Nikbakht, A. Preparation of PEO/silane composite coating on AZ31 magnesium alloy and investigation of its properties. J. Alloy. Compd. 2021, 876, 159995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udoh, I.I.; Shi, H.; Daniel, E.F.; Li, J.; Gu, S.; Liu, F.; Han, E.-H. Active anticorrosion and self-healing coatings: A review with focus on multi-action smart coating strategies. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2022, 116, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedźwiedź, M.; Korzekwa, J.; Bara, M.; Kaptacz, S.; Aniołek, K.; Sowa, M.; Simka, W. The Influence of PEO Process Parameters on the Mechanical and Sclerometric Properties of Coatings on the Ultralight Magnesium Alloy LA141. Coatings 2025, 15, 961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattah-Alhosseini, A.; Molaei, M.; Kaseem, M. A review on the plasma electrolytic oxidation (PEO) process applied to copper and brass. Surf. Interfaces 2024, 46, 104179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, C.; Wang, F.; Zha, Z.; Liu, L. Effect of cathodic current density on the structure and properties of MAO coatings on 2195 Al-Li alloy. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 46, 112776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Blawert, C.; Zheludkevich, M.L. Influence of secondary phases of AlSi9Cu3 alloy on the plasma electrolytic oxidation coating formation process. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2020, 50, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanaa, T.T.; Fattah-Alhosseini, A.; Alkaseem, M.; Kaseem, M. Improving the surface properties of Mg based-plasma electrolytic oxidation (PEO) coatings under the fluoride electrolytes: A review. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2024, 170, 113163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, L.; Ma, Y.; Sun, L.; Wang, Z.; Wang, S. Investigation of mutual effects among additives in electrolyte for plasma electrolytic oxidation on magnesium alloys. J. Magnes. Alloy. 2020, 8, 523–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Ying, G.; Fei, Q. Unveiling the role of SiC particle reinforcement on aluminum matrix composites surface: Insights into PEO coating growth, electrical insulation, and corrosion resistance. Ceram. Int. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satbayeva, Z.; Zhassulan, A.; Rakhadilov, B.; Shynarbek, A.; Ormanbekov, K.; Leonidova, A. Effect of Micro-Arc Oxidation Voltage on the Surface Morphology and Properties of Ceramic Coatings on 7075 Aluminum Alloy. Metals 2025, 15, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Ma, M.; Shi, G.; Yuan, J.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, K.; Jin, C.; Liu, W. Fabrication and long-term in vitro corrosion behavior of MAO coating on biodegradable Mg-3Zn-0.7Mn-0.5Sr alloy. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 47, 113220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaseem, M.; Aadil, M.; Thanaa, T.T.; Alkaseem, M. Improving the photocatalytic performance of TiO2 coating via the dual incorporation of MoO2 and V2O5 by plasma electrolytic oxidation. Surf. Interfaces 2024, 46, 104179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, W.; Yu, F.; Cao, W.; Hu, S. Effect of sodium fluoride additive on microstructure and corrosion performance of micro-arc oxidation coatings on EK30 magnesium alloy. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2025, 496, 131628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M. Effect of oxidation time on the microstructure, mechanical properties, and corrosion resistance of MAO ceramic film on 5B70 Al alloy. Mater. Des. 2025, 254, 114039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krit, B.L.; Mogilnaya, T.Y.; Morozova, N.V.; Ya, B.S.; Ruizhi, W.; Medvetskova, V.M.; Dolgushin, Y.V.; Petelin, N.A. Modelling of photoactivation process to plasma-electrolyte coating on magnesium alloy. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2024, 323, 129669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, H.; Liu, C.; Wang, W.; Chen, B. Influence of additives on the macroscopic color and corrosion resistance of 6061 aluminum alloy micro-arc oxidation coatings. Materials 2024, 17, 2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Meng, X.; Li, X.; Li, Z.; Yan, H.; Wu, L.; Cao, F. Effect of electrolyte composition on corrosion behavior and tribological performance of plasma electrolytic oxidized TC4 alloy. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2023, 33, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Q.; Li, X.; Yao, Z.; Jiang, Z. Investigations on the Thermal Control Properties and Corrosion Resistance of MAO Coatings Prepared on Mg-5Y-7Gd-1Nd-0.5Zr Alloy. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2021, 409, 126874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Wang, S.; Xie, D.; Li, Q.; Zhao, D.; Guo, H.; Wu, J.; Jiang, W.; Meng, X.; An, L. Enhancing understanding of cooperation mechanism of electrolyte composition on PEO coating growth for magnesium alloys via load characteristics. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2024, 494, 131307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Yuan, K.; Song, Y.; Cao, J.; Xu, L.; Xu, J. Plasma electrolytic oxidation of Zircaloy-2 alloy in potassium hydroxide/sodium silicate electrolytes: The effect of silicate concentration. Boletín Soc. Española Cerámica Vidr. 2021, 60, 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salami, B.; Afshar, A.; Mazaheri, A. The effect of sodium silicate concentration on microstructure and corrosion properties of MAO-coated magnesium alloy AZ31 in simulated body fluid. J. Magnes. Alloy. 2014, 2, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, Z.U.; Koo, B.H. Effect of Na2SiO3·5H2O concentration on the microstructure and corrosion properties of two-step PEO coatings formed on AZ91 alloy. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2017, 317, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghdadabad, D.M.; Baghdadabad, A.R.M.; Khoei, S.M.M. Characterization of bioactive ceramic coatings synthesized by plasma electrolyte oxidation on AZ31 magnesium alloy having different Na2SiO3·9H2O concentrations. Mater. Today Commun. 2020, 25, 101642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, G.; Wang, L.; Wu, J.; Zheng, J.; Sun, H.; DaCosta, H. Effects of electrolytes on the growth behavior, microstructure and tribological properties of plasma electrolytic oxidation coatings on a ZA27 alloy. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2015, 277, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Li, H.; Ma, Q.; Lu, J.; Li, Z. The mechanism for tuning the corrosion resistance and pore density of plasma electrolytic oxidation (PEO) coatings on Mg alloy with fluoride addition. J. Magnes. Alloy. 2023, 11, 2823–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Yu, J.; Song, Y.; Shan, D.; Han, E.-H. Effect of potassium fluoride on the in-situ sealing pores of plasma electrolytic oxidation film on AM50 Mg alloy. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2015, 162, 452–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blawert, C.; Heitmann, V.; Dietzel, W.; Nykyforchyn, H.M.; Klapkiv, M.D. Influence of electrolyte on corrosion properties of plasma electrolytic conversion coated magnesium alloys. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2007, 201, 8709–8714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Wu, G.; Atrens, A.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Ding, W. Correlation between KOH concentration and surface properties of AZ91 magnesium alloy coated by plasma electrolytic oxidation. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2021, 31, 913–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, W.; Wang, F.; Lu, X.; Blawert, C.; Zheludkevich, M.L. Interaction effect between different constituents in silicate-containing electrolyte on PEO coatings on Mg alloy. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2016, 307, 825–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xia, Y. Microarc oxidation coating fabricated on AZ91D Mg alloy in an optimized dual electrolyte. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2013, 23, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakili-Azghandi, M.; Fattah-Alhosseini, A.; Keshavarz, M.K. Optimizing the electrolyte chemistry parameters of PEO coating on 6061 Al alloy by corrosion rate measurement: Response surface methodology. Measurement 2018, 124, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HB5061-77; Quality Inspection of Chemical Oxide Coatings on Magnesium Alloys. China Aviation Industry Standardization Institute: Beijing, China, 1977.

- Wang, Z.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Y. Effect of V2O5 Additive on Micro-Arc Oxidation Coatings Fabricated on Magnesium Alloys with Different Loading Voltages. Metals 2020, 10, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornell, J.A. Experiments with Mixtures: A Review. Technometrics 1973, 15, 437–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Y.; Hu, C.R. Experiment Design and Data Processing, 3rd ed.; Chemical Industrial Press: Beijing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Khaskhoussi, A.; Calabrese, L.; Bouhamed, H.; Kamoun, A.; Proverbio, E.; Bouaziz, J. Mixture design approach to optimize the performance of TiO2 modified zirconia/alumina sintered ceramics. Mater. Des. 2018, 137, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talat, M.; Prakash, O.; Hasan, S.H. Enzymatic detection of As(III) in aqueous solution using alginate immobilized pumpkin urease: Optimization of process variables by response surface methodology. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 4462–4467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, R.J.S.; Sato, H.H. Synergistic effects of agroindustrial wastes on simultaneous production of protease and α-amylase under solid state fermentation using a simplex centroid mixture design. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2013, 49, 813–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, M.; Niaei, A.; Salari, D.; Khataee, A. Application of response surface methodology for optimization of peroxi-coagulation of textile dye solution using carbon nanotube–PTFE cathode. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 173, 544–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, I.; Choi, J.H.; Zhao, B.H.; Baik, H.K.; Lee, I.S. Micro-arc oxidation in various concentration of KOH and structural change by different cut off potential. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2007, 7, e23–e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, T.; Wu, K.; Wang, F. Role of β Phase during Microarc Oxidation of Mg Alloy AZ91D and Corrosion Resistance of the Oxidation Coating. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2013, 29, 1129–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, T.; Wang, F. Influence of second phase on corrosion performance and formation mechanism of PEO coating on AZ91 Mg alloy. J. Alloy. Compd. 2017, 718, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xu, T.; Shao, Q.; Huang, S.; Jiang, B.; Liang, J.; Li, H. Effects of beta phase on the growth behavior of plasma electrolytic oxidation coating formed on magnesium alloys. J. Alloy. Compd. 2019, 784, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaddle, T.W. Silicate complexes of aluminum (III) in aqueous systems. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2001, 219–221, 665–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Zhu, Q.; Zhuang, J.; Yu, S. An expert recommendation algorithm based on Pearson correlation coefficient and FP-growth. Cluster. Comput. 2019, 22, 7401–7412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Yang, D.; Guo, Y. Laser ultrasonic damage detection in coating-substrate structure via Pearson correlation coefficient. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2018, 353, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barchiche, C.E.; Veys-Renaux, D.; Rocca, E. A better understanding of PEO on Mg alloys by using a simple galvanostatic electrical regime in a KOH–KF–Na3PO4 electrolyte. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2011, 205, 4243–4248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, P.M.; Case, B.; Dearnaley, G.; Turner, J.F.; Woolsey, I.S. Ion beam analysis of corrosion films on a high magnesium alloy (Magnox Al 80). Corros. Sci. 1976, 16, 747–766. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L.; Ma, Y.; Wang, J.; An, L.; Wang, S.; Wang, Z. Preparation and corrosion resistance of hybrid coatings formed by PEN/C plus PEO on AZ91D magnesium alloys. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2020, 390, 125661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, F.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, T.; Wang, F. Effect of variations of Al content on microstructure and corrosion resistance of PEO coatings on Mg-Al alloys. J. Alloy. Compd. 2017, 690, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla, F.A.; Berkani, A.; Liu, Y.; Skeldon, P.; Thompson, G.E.; Habazaki, H.; Shimizu, K.; John, C.; Stevens, K. Formation of Anodic Films on Magnesium Alloys in an Alkaline Phosphate Electrolyte. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2002, 149, B4–B12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Run | Space Point Type | Code Values | Responses | |||||

| x1 | x2 | x3 | x4 | Formability | Thickness/μm | Spotting Time/s | ||

| 1 | Vertex | 45 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5.66 | 15.22 |

| 2 | Vertex | 0 | 45 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4.40 |

| 3 | Vertex | 0 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4.40 |

| 4 | Vertex | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 1 | 1.35 | 12.33 |

| 5 | Cent Edge | 22.5 | 22.5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 16.98 | 172.96 |

| 6 | Cent Edge | 22.5 | 0 | 7.5 | 0 | 1 | 9.81 | 42.35 |

| 7 | Cent Edge | 22.5 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 4.40 |

| 8 | Cent Edge | 0 | 22.5 | 7.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4.40 |

| 9 | Cent Edge | 0 | 22.5 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 7.69 | 34.75 |

| 10 | Cent Edge | 0 | 0 | 7.5 | 6 | 1 | 5.48 | 15.79 |

| 11 | Trip Blend | 15 | 15 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 12.16 | 78.18 |

| 12 | Trip Blend | 15 | 15 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4.40 |

| 13 | Trip Blend | 15 | 0 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4.40 |

| 14 | Trip Blend | 0 | 15 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 6.79 | 19.11 |

| 15 | Center | 11.25 | 11.25 | 3.75 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 4.40 |

| Response | Equation |

| y1/μm | 0.124x1 + 0.029x1x2 + 0.043x1x3 − 0.021x1x4 + 0.059x2x4 + 0.128x3x4 − 0.012x1x2x4 − 0.021x1x3x4 − 0.002x1x2x3x4 |

| y2/s | 0.338x1 + 0.094x2 + 0.283x3 + 1.047x4 + 0.322x1x2 + 0.193x1x3 − 0.07x1x4 + 0.188x2x4 + 0.144x3x4 − 0.015x1x2x3 − 0.095x1x2x4 − 0.065x1x3x4 − 0.005x1x2x3x4 |

| Dependent Variables | F-Value | p-Value Prob > F | R2(Adj) |

| y1 | 155.00 | <0.001 (**) | 0.9893 |

| y2 | 1003.97 | 0.001 (**) | 0.9989 |

| Response | x1 | x2 | x3 | x4 | x1x2 | x1x3 | x1x4 | x2x4 | x3x4 | x1x2x3 | x1x2x4 | x1x3x4 | x1x2x3x4 |

| y1 | 0.302 | - | - | - | 0.777 | 0.384 | 0.101 | 0.421 | 0.305 | - | 0.544 | 0.317 | 0.136 |

| y2 | 0.069 | 0.028 | 0.028 | 0.082 | 1.040 | 0.208 | 0.041 | 0.162 | 0.041 | 0.102 | 0.519 | 0.118 | 0.041 |

| No. | Na2SiO3 (g·L−1) | KF (g·L−1) | NaOH (g·L−1) | NaAlO2 (g·L−1) | pH | Conductivity (mS·cm−1) | Breakdown Voltage (V) | ∆T (°C) | Surface Porosity |

| 11# | 15 | 15 | 5 | 0 | 13.08 | 38.1 | 154 | 4.3 | 10.399% |

| 12# | 15 | 15 | 0 | 4 | 12.92 | 28.2 | 285 | 5.2 | - |

| 13# | 15 | 0 | 5 | 4 | 12.98 | 35.2 | 192 | 10.4 | - |

| 14# | 0 | 15 | 5 | 4 | 13.13 | 34.7 | 186 | 4.7 | 8.103% |

| No. (wt%) | Mg | O | Al | Si | F |

| 11# | 42.15 | 31.60 | 6.08 | 14.25 | 5.92 |

| 12# | 50.13 | 26.84 | 8.07 | 2.40 | 12.57 |

| 13# | 38.22 | 34.14 | 16.60 | 11.05 | - |

| 14# | 45.23 | 31.79 | 17.23 | - | 5.75 |

| No. | Ecorr/V | Jcorr/(10−7 A·cm−2) | Rp/(104 Ohm·cm2) | Loop area/(V·A) |

| substrate | −1.521 | 85.17 | 0.2673 | 9.641× 102 |

| 11# | −1.454 | 0.591 | 52.33 | 7.8× 103 |

| 14# | −1.446 | 0.436 | 85.34 | 3.36× 103 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Ma, Y.; Meng, L.; An, L. Interactions Effect Among the Electrolytes on Micro-Arc Oxidation Coatings of AZ91D Mg Alloy. Metals 2025, 15, 1378. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121378

Wang Z, Zhao Q, Ma Y, Meng L, An L. Interactions Effect Among the Electrolytes on Micro-Arc Oxidation Coatings of AZ91D Mg Alloy. Metals. 2025; 15(12):1378. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121378

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Zhanying, Qinqin Zhao, Ying Ma, Leichao Meng, and Lingyun An. 2025. "Interactions Effect Among the Electrolytes on Micro-Arc Oxidation Coatings of AZ91D Mg Alloy" Metals 15, no. 12: 1378. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121378

APA StyleWang, Z., Zhao, Q., Ma, Y., Meng, L., & An, L. (2025). Interactions Effect Among the Electrolytes on Micro-Arc Oxidation Coatings of AZ91D Mg Alloy. Metals, 15(12), 1378. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121378